Abstract

MyoD, a master regulator of myogenesis, exhibits a circadian rhythm in its mRNA and protein levels, suggesting a possible role in the daily maintenance of muscle phenotype and function. We report that MyoD is a direct target of the circadian transcriptional activators CLOCK and BMAL1, which bind in a rhythmic manner to the core enhancer of the MyoD promoter. Skeletal muscle of ClockΔ19 and Bmal1−/− mutant mice exhibited ∼30% reductions in normalized maximal force. A similar reduction in force was observed at the single-fiber level. Electron microscopy (EM) showed that the myofilament architecture was disrupted in skeletal muscle of ClockΔ19, Bmal1−/−, and MyoD−/− mice. The alteration in myofilament organization was associated with decreased expression of actin, myosins, titin, and several MyoD target genes. EM analysis also demonstrated that muscle from both ClockΔ19 and Bmal1−/− mice had a 40% reduction in mitochondrial volume. The remaining mitochondria in these mutant mice displayed aberrant morphology and increased uncoupling of respiration. This mitochondrial pathology was not seen in muscle of MyoD−/− mice. We suggest that altered expression of both Pgc-1α and Pgc-1β in ClockΔ19 and Bmal1−/− mice may underlie this pathology. Taken together, our results demonstrate that disruption of CLOCK or BMAL1 leads to structural and functional alterations at the cellular level in skeletal muscle. The identification of MyoD as a clock-controlled gene provides a mechanism by which the circadian clock may generate a muscle-specific circadian transcriptome in an adaptive role for the daily maintenance of adult skeletal muscle.

Keywords: circadian clock, myofilaments, mitochondria

A fundamental, evolutionarily conserved property of most organisms, from cyanobacteria to plants and animals, is the daily cycling of their internal physiology as well as certain behaviors in animals, such as sleep and feeding (1). The timing of these circadian rhythms is synchronized to the environment by external cues, with light and nutrient availability being two of the most salient entrainment cues (2). The synchronization of endogenous circadian rhythms with the daily cycles in the environment provides an adaptive mechanism for organisms to anticipate cyclic demands on cellular physiology and behavior (3, 4). At the molecular level, the circadian clock represents a well-defined gene regulatory network composed of transcriptional-translational feedback loops (5). The positive arm of the loop is composed of the transcription factors CLOCK and BMAL1, which heterodimerize and bind to E-box elements on target genes such as Per1 to drive the negative part of the feedback loop (5). More recently, the same molecular clock factors that have been identified in the central clock in the suprachiasmatic nucleus have been found to exist in most peripheral tissues (reviewed in ref. 6).

We recently characterized the circadian transcriptome of adult skeletal muscle. These mRNAs exhibit significant oscillation in gene expression with a repeating period length of 24 h. One of the intriguing observations from the array data was the finding that MyoD mRNA exhibited a circadian pattern (7, 8). MyoD is a well-established skeletal muscle-specific transcription factor that directly regulates expression of the myogenic program (9). In addition to MyoD, we found that the core components of the molecular clock, including Bmal1 and Per2 expression, were oscillating as is seen in liver and other peripheral tissues (7). Interestingly, MyoD expression, like Per2 mRNA, did not oscillate in muscle of the ClockΔ19 mutant mouse, suggesting the possibility that MyoD is a clock-controlled gene.

We show here that MyoD is regulated by the circadian transcriptional activators CLOCK and BMAL1. In addition, we find that skeletal muscles from either ClockΔ19 or Bmal1−/− mice exhibit significant functional deficits in contractile force, disrupted myofilament architecture, and altered expression of MyoD target genes. Morphological and functional analyses show that the muscle of MyoD−/− mice phenocopy that seen in the ClockΔ19 and Bmal1−/− mice, providing evidence that suggests that MyoD may act as a molecular link between the circadian clock and skeletal muscle maintenance. The skeletal muscles of ClockΔ19 and Bmal1−/−, but not MyoD−/−, mice also have profound mitochondrial pathologies that were associated with altered expression of both Pgc-1α and Pgc-1β in the circadian mutant mice. These results show that a lineage-specific transcription factor, MyoD, is a clock-controlled gene and define the circadian factors CLOCK and BMAL1 as critical modulators of molecular, cellular, and functional parameters of skeletal muscle.

Results

MyoD Is a Clock-Controlled Gene.

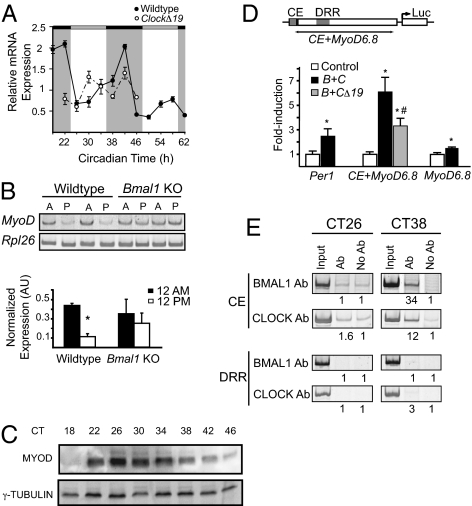

We recently reported that myogenic differentiation 1 (MyoD) mRNA is expressed in a circadian fashion in adult skeletal muscle (7). The identification of MyoD as a circadian gene was of interest because MyoD is well-established as a master regulator of the skeletal muscle transcriptional program (9). To validate the array results, we performed quantitative PCR analysis of MyoD mRNA from wild-type gastrocnemius muscles collected every 4 h for 48 h. The frequency (every 4 h) and duration (48 h) of sample collection was required to establish the 24-hr repeating oscillation pattern of circadian mRNA expression. The results are presented in Fig. 1A and confirm that MyoD mRNA exhibits a circadian oscillation with a greater than twofold change in amplitude over 24 h (Fig. 1A). Analysis of MyoD mRNA levels in muscle from ClockΔ19 and Bmal1−/− mice (Fig. 1 A and B) demonstrated that the circadian oscillation in MyoD mRNA was abolished, similar to other known cycling genes such as Per2 and Dbp. Western blot analysis of whole-muscle extracts from wild-type mice show that MYOD protein levels oscillate over 24 h with the peak levels in MYOD protein lagging the peak mRNA levels by about 4–8 h (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

MyoD is a clock-controlled gene in skeletal muscle. (A) Expression of MyoD in wild type (●) and ClockΔ19 (○) muscle was determined by quantitative PCR. Samples were collected every 4 h for 48 h starting at circadian time 18 (CT18) through CT62. Even though all collections were performed under total darkness, the dark and light stripes on the graph represent presumptive dark and light phases of the mice. (B) The diurnal expression (12:00 AM vs. 12:00 PM) of MyoD in wild-type (lanes 1–4) and Bmal1−/− (lanes 5–8) skeletal muscle was determined by semiquantitative PCR normalized to Rpl26 gene expression. Muscles (n = 4/group) were collected under DD at either 12:00 AM (lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7) or 12:00 PM (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8). Histogram of densitometric quantification showed a significant (P < 0.05) diurnal expression of MyoD in wild-type muscle that is lost in Bmal1−/− muscle. (C) Western blots demonstrating circadian oscillation of MyoD levels in muscle of wild-type mice collected every 4 h for 28 h (CT18–46). (D) Illustration of MyoD reporter gene (CE+MyoD6.8) showing the position of the CE and DRR. The histogram summarizes results from transfection experiments using either a Per1 reporter gene or the MyoD reporter gene in C2C12 cells (n = 3/conditions). Over-expression of CLOCK and BMAL1 (black bar) significantly transactivated Per1 and CE-MyoD reporter genes by ∼2.5-fold and 6-fold, respectively, relative to control transfections (open bar). MyoD reporter was not activated by BMAL1:CLOCK, and activation of CE-MyoD reporter was significantly decreased by 50% when ClockΔ19 was over-expressed with BMAL1 (gray bar). Values are mean ± SEM with significance (P < 0.05) denoted by an asterisk or a pound sign (B+C vs. B+CΔ19). (E) Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays from muscles collected at CT26 and CT38 demonstrating CLOCK and BMAL1 binding to the CE at CT38 and no binding at the DRR of the MyoD promoter. The numbers under each lane represent the ratio of the intensity of the Ab band/No Ab band.

To test whether MyoD was a transcriptional target of CLOCK and BMAL1, we performed transcriptional reporter gene and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments. MyoD luciferase reporter genes (CE+6.8MyoD, 6.8MyoD; Fig. 1D), which incorporated previously identified regulatory regions of the MyoD promoter; the 6.8 kb of the 5′ flanking region that contained the distal regulatory region (DRR) plus or minus the core enhancer (CE) were used (10, 11). As shown in Fig. 1D, expression of CLOCK and BMAL1 significantly induced expression of the Per1 reporter ∼2.5-fold and the CE+6.8MyoD reporter approximately sixfold (P < 0.05). However, activation of the MyoD reporter required the CE element, as expression of BMAL1 and CLOCK did not activate the 6.8MyoD reporter. Full activation of the CE+6.8MyoD reporter required a wild-type CLOCK activator because transfection with an expression vector encoding the ClockΔ19 mutant cDNA resulted in an about 50% reduction in MyoD promoter activity (Fig. 1D). The CE and the DRR enhancers of the MyoD promoter have previously been shown using enhancer-specific knockout mice to provide complementary regulation of MyoD expression during development and maturation (12, 13). ChIP assays were performed using muscle samples collected from mice at selected times when MyoD mRNA is lowest [circadian time 26 (CT26)] and when MyoD mRNA is rising (CT38) to determine whether CLOCK and BMAL1 bind the CE or DRR of the MyoD promoter in adult skeletal muscle. We found that CLOCK and BMAL1 bind to the CE and that this binding was enriched by 12- and 34-fold, respectively, at CT38 compared with CT26. In contrast, no CLOCK or BMAL1 binding was detected at the DRR, regardless of the time of day (Fig. 1E). Taken together, these results support the hypothesis that MyoD is a direct target of CLOCK:BMAL1 binding at the CE and thus is a primary clock-controlled gene.

Decreased Function and Altered Structure in Skeletal Muscle of Circadian Mutant and MyoD−/− Mice.

We next tested whether specific tension, a measure of muscle function, was compromised in ClockΔ19, Bmal1−/−, and MyoD−/− mice compared with that of wild-type mice. Specific tension is the maximal isometric tetanic force normalized for muscle size; an example of a force trace from wild-type muscle is shown in Fig. 2A. The average specific tension (Fig. 2B) was significantly depressed in the extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles of 12- to 14-wk-old ClockΔ19 (−29.7%), Bmal1−/− (−34.4%), and MyoD−/− (−33%) mice compared with EDL muscles from wild-type mice (P < 0.05). This decrease in specific tension was due to lower maximal force as we found that there was no difference in EDL wet mass or fiber length among the genotypes. In addition, light microscopy of toludine-blue–stained muscle sections indicated that there were no dramatic pathologies. As seen in Fig. S1, the fibers from the ClockΔ19 mutant and MyoD−/− mice did not exhibit any disease hallmarks such as central nuclei or significant areas of fat or connective tissue infiltration.

Fig. 2.

Decreased whole-muscle function, single-cell function, and myofilament structure in ClockΔ19, Bmal−/−, and MyoD−/− mice. (A) Representative force trace from the measurement of specific tension of whole-muscle (EDL) from wild-type mice. (B) Histogram of the average specific tensions of muscles for ClockΔ19, Bmal1−/−, and MyoD−/− mice (n = 3–6/strain). Significant difference (P < 0.05) from wild type is denoted by an asterisk. (C) Results from single-fiber mechanical analyses of wild-type (△) and Bmal1−/− (○) muscle fibers. Each point on the curve represents the average ± SEM for measures of 7–20 cells at each calcium concentration. (D) Data from C reported as tension relative to maximal tension for each calcium concentration. (E) Representative myofilament images obtained by electron microscopy (43,000×) from wild-type, ClockΔ19, Bmal1−/−, and MyoD−/− gastrocnemius muscles. The normal organization of thin and thick filaments is disrupted in muscle from the three different mutant animals.

To test whether the mechanical deficits could be detected at the single-cell level, we performed mechanics on isolated skinned fiber segments from EDL muscles of wild-type and Bmal1−/− mice (14). Similar to that seen with whole-muscle tissue, maximally activated specific tension (in kNm−2: force normalized for Per1 cross-section) was significantly lower in the fiber segments from the Bmal1−/− mice compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 2C). To evaluate potential influences of calcium sensitivity, the tension measures at each of the calcium concentrations were normalized to the maximal tension for each fiber (Fig. 2D). We found no difference in the relative force:pCa (pCa = −log10 [Ca2+]) curves, indicating that the difference in maximal specific tension was not due to altered calcium ion sensitivity of the myofilaments from Bmal1−/− mice.

The results of single-fiber experiments suggest that the decrement in force capacity of muscle could occur at the level of myofilament organization. We used electron microscopy (EM) to evaluate the myofilament and sarcomeric architecture of skeletal muscle from wild-type, ClockΔ19, Bmal1−/−, and MyoD−/− mice (n = 3/genotype). Analyses of EM images (43,000×) from muscle cross-sections revealed that the highly conserved hexagonal arrangement of the thin and thick filaments was significantly disrupted in muscle from the ClockΔ19, Bmal1−/−, and MyoD−/− mice (Fig. 2E). The abnormal geometry observed in the myofilament structure of ClockΔ19, Bmal1−/−, and MyoD−/− mice was defined by variation in the number of thin filaments associated with each thick filament, irregular thin-to-thin filament spacing, and irregular thick-to-thick filament spacing. We also found that when we analyzed EM images from longitudinal sections of muscle from ClockΔ19, Bmal1−/−, and MyoD−/− mice that the registry of the sarcomeres was compromised (Fig. S2).

Decreased Mitochondrial Volume and Depressed Respiratory Function of Muscles from Circadian Mutant Mice.

The electron micrographs from the gastrocnemius muscles of the ClockΔ19, Bmal1−/−, and MyoD−/− mice were also used to analyze mitochondria. From these micrographs we found that there was a dramatic loss in the number of mitochondria, especially beneath the muscle membrane in muscle of the ClockΔ19 and Bmal1−/− mice (Fig. 3A and Fig. S3). The mitochondrial volume was quantified using the point-counting morphometric technique as described by Eisenberg (15). Consistent with the images, there was a 40% reduction in mitochondrial volume of skeletal muscle from ClockΔ19 and Bmal1−/− mice (Fig. 3B). In addition to the dramatic loss of mitochondria, higher magnification revealed that the remaining mitochondria exhibited a pathological morphology characterized by swelling and disruption of cristae (Fig. 3C). By contrast, skeletal muscle of MyoD−/− showed no mitochondrial phenotype (Fig. S4).

Fig. 3.

Decreased mitochondrial volume and respiratory function in muscle of ClockΔ19 and Bmal1−/− mice. (A) Low-magnification EM images (4,000×) of skeletal muscle from wild-type, ClockΔ19, and Bmal1−/− mice. The white arrow in each image points to the region of the muscle under the sarcolemma where there are abundant mitochondria (wild type) or where mitochondria are lacking (ClockΔ19 and Bmal1−/−). (B) Histogram of mitochondrial volume measured using point-counting morphometry. The values are presented as a percentage of muscle-fiber volume from wild-type (black bar), ClockΔ19 (gray bar), and Bmal1−/− (open bar) mice. Values represent mean ± SEM (n = 5 muscles/strain) with significance (P < 0.05) denoted by an asterisk. (C) Representative high-magnification EM images (21,000×) of mitochondria within skeletal muscle of wild-type, ClockΔ19, and Bmal1−/− mice. Note swollen size and disrupted cristae of the mitochondria from muscle of ClockΔ19 and Bmal1−/− mice. (D) Histograms of biochemical measurements of respiratory control ratio (RCR) in gastrocnemius (GTN) and diaphragm (DIA) muscles of wild-type and Bmal1−/− mice (n = 6/strain). Values are means ± SEM with significance (P < 0.05) denoted by an asterisk. (E) Histograms showing significant reduction in state III respiration (ADP-stimulated, mmol O2/min/mg protein) in mitochondria isolated from GTN muscle of Bmal1−/− mice compared with wild type. Values are means ± SEM with significance (P < 0.05) indicated by an asterisk.

We next isolated mitochondria from gastrocnemius and diaphragm muscles of wild-type and Bmal1−/− mice and determined the biochemical function and the respiratory control ratio (RCR). The RCR represents the ratio of state 3 to state 4 respiration and indicates how well coupled the biochemical processes are within the mitochondria. Compared with wild-type mitochondria, the RCR of mitochondria isolated from gastrocnemius (GTN) and diaphragm (DIA) muscles of Bmal1−/− mice was depressed 43% and 72%, respectively (Fig. 3D). The decrease in the RCR of mitochondria isolated from skeletal muscle of Bmal1−/− was primarily due to a reduction in state 3 respiration as state 4 respiration was not significantly different from wild type (Fig. 3E and Fig. S5). These results are consistent with the EM analysis and indicate that the function of the surviving mitochondria in the muscles of the 12- to 14-wk-old Bmal1−/− mice are impaired.

Altered Expression of Pgc-1α and Pgc-1β in Circadian Mutant Skeletal Muscle.

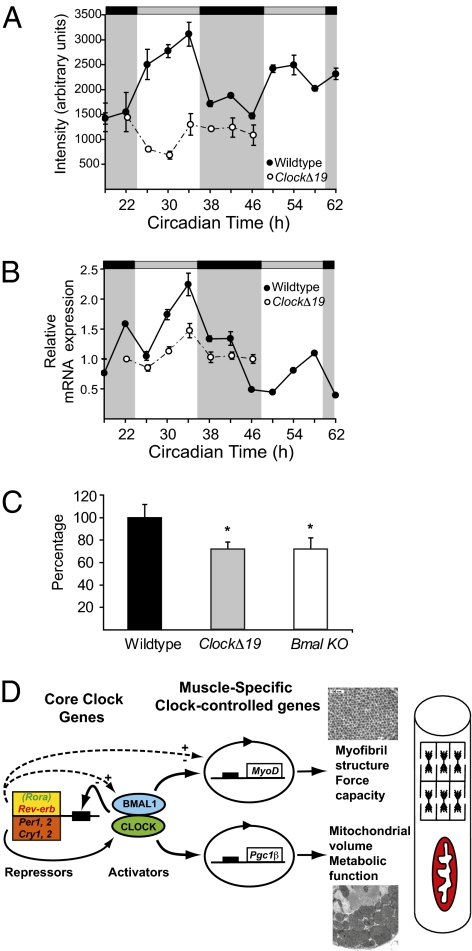

Because the mitochondrial pathology was not found in the muscle of MyoD−/− mice, we looked for potential genes that could link the circadian factors CLOCK and BMAL1 with mitochondrial biogenesis/function. Data from the expression profiling of the skeletal-muscle circadian transcriptome identified Pgc-1β as a circadian mRNA (Fig. 4A). We performed quantitative PCR measurements of Pgc-1β in wild-type skeletal muscle and found circadian mRNA expression that was damped in the muscle of ClockΔ19 mice (Fig. 4B). We also confirmed that Pgc-1α expression, although not circadian, was significantly down-regulated in skeletal muscle of ClockΔ19 and Bmal1−/− mice compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 4C) (7). These results show that both members of the Pgc-1 coactivator family are mis-regulated in muscle of both ClockΔ19 and Bmal1−/− mice.

Fig. 4.

Altered expression of Pgc-1 coactivators in ClockΔ19 and Bmal1−/− mice. (A) Array data of Pgc-1β mRNA expression in skeletal muscle of wild-type mice (●) and ClockΔ19 mice (○); the light and dark stripes refer to the presumptive light and dark phases for the mice (7). (B) Quantitative PCR results for expression of Pgc-1β in wild-type muscle (●) and ClockΔ19 muscle (○). (C) Histogram of the mean expression level of PGC1α mRNA in muscle of wild-type, ClockΔ19, and Bmal1−/− mice as determined by quantitative PCR. A significant difference (P < 0.05) is denoted by an asterisk. (D) Proposed model of CLOCK:BMAL1 regulation of muscle phenotype and function via targeting of MyoD and Pgc-1 expression. Solid lines indicate known molecular links among components of the molecular clock, and dashed lines suggest potential links.

Discussion

The results presented here demonstrate that the circadian factors CLOCK and BMAL1 are critical for skeletal-muscle function, structure, and mitochondrial content. Muscles from both ClockΔ19 and Bmal1−/− mice showed profound decrements in force-generating capacity, significant myofilament and sarcomeric disarray, and mitochondrial pathologies. Molecular studies identified MyoD, the muscle-specific transcription factor, as a clock-controlled gene under direct transcriptional control of CLOCK and BMAL1. Additionally, muscle from adult MyoD−/− mice exhibits similar functional and structural abnormalities as those seen in ClockΔ19 and Bmal1−/− mice, providing evidence that suggests that circadian regulation of MyoD may be one mechanism for maintaining adult skeletal muscle. However, the mitochondrial pathologies observed in the ClockΔ19 and Bmal1−/− mice were not found in the muscle of the MyoD−/− mouse. We found that both Pgc-1α and Pgc-1β were mis-expressed in the muscles of ClockΔ19 and Bmal1−/− mice. From these results we suggest a working model, illustrated in Fig. 4D, in which the transcriptional activators CLOCK and BMAL1 regulate daily expression of MyoD as a component of a maintenance program for structure and mechanical function. In addition, we suggest that CLOCK and BMAL1 may regulate Pgc-1 in a parallel pathway to maintain mitochondrial levels. These results provide molecular, cellular, and physiological evidence to support the critical role of CLOCK and BMAL1 in adult skeletal-muscle function and metabolism.

Circadian Rhythms, Skeletal Muscle, and MyoD.

Circadian rhythms and the core clock factors CLOCK and BMAL1 have been implicated in a growing number of systemic pathologies, including metabolic disease, aging, and cardiovascular disease (16–18). To date, however, no genetic studies have examined what role circadian rhythms play in adult skeletal muscle. Our earlier results from an expression profiling study identified circadian expression of the components of the molecular clock (e.g., Bmal1, Per2) and showed that expression of MyoD, a master regulator of skeletal muscle differentiation, followed a circadian pattern (7, 8).

MyoD is the founding member of the myogenic regulatory factor family of transcription factors, which includes Myf5, myogenin, and MRF4 (19). Although the function of MyoD in myogenesis is known in considerable detail, our understanding of its role in adult skeletal muscle remains incomplete (20). The deficit in specific tension of MyoD−/− mice, in addition to their impaired regenerative ability, suggests that MyoD serves an important function in adult skeletal muscle (21, 22). The importance of MyoD function in adult skeletal muscle is further underscored by the observation that MyoD expression is altered in a number of muscular dystrophies as well as in sarcopenia, the age-associated loss of muscle mass (23–25). The identification of MyoD as a clock-controlled gene expands the function of MyoD beyond its well-known role in myogenesis to include a role in the daily maintenance of adult skeletal muscle.

The loss of circadian expression of MyoD in skeletal muscle from both ClockΔ19 and Bmal1−/− mice is very similar to what has been previously observed with other genes known to be regulated by BMAL1 and CLOCK, such as Per2 and Dbp (referred to as clock-controlled genes) (7, 8). Results from reporter gene assays and ChIP experiments confirmed that MyoD is a direct target of CLOCK and BMAL1. In particular, ChIP assays show that CLOCK and BMAL1 bind to the MyoD CE and not to the DRR of the promoter. The CE is located ≈20 kb upstream of the transcriptional start site, and analysis of MyoD expression in the CE knockout mouse revealed that the CE is required to ensure the correct temporal activation of MyoD transcription during development (12, 26). The fact that the CE has been shown to be critical for proper temporal expression of MyoD during development and now for the circadian expression of MyoD raises intriguing questions about the possibility that (i) CLOCK and/or BMAL1 have a noncircadian function during myogenesis and (ii) the CE serves as a “timing” module to provide a temporal component to MyoD expression during embryonic development and adulthood. At this time, CLOCK and/or BMAL1 have not been shown to regulate developmental gene expression in mammals, but there are some studies linking their homologs to development in Arabidopsis (27).

As a global assessment of muscle-tissue function, we found that the specific tension of skeletal muscle was significantly depressed in the circadian mutant mice. Surprisingly, skeletal muscle from both ClockΔ19 and Bmal1−/− mice displayed a similar reduction in specific tension, and these deficits are very comparable to those observed in Duchenne muscular dystrophy as well as those seen with aging (28, 29). An important consideration for interpretations of our findings is that even though the muscle pathologies reported in the Bmal1−/− and ClockΔ19 mice are similar, the health and phenotype of the mice are profoundly different. The ClockΔ19 mouse has a normal life span, but it exhibits signs of metabolic disease by 8 mo of age (16). The Bmal1−/− mice die around 12 mo of age but, when they are 10 wk of age, Bmal1−/− mice have similar body weight, normal skeletal-muscle fiber area, and normal distribution of circulating white blood cells compared with control mice (17). Our experiments were performed on mice 12–14 wk of age at a time when neither Bmal1−/− nor ClockΔ19 mice show significant disease status (16, 17, 30). Thus, we suggest that the reduction in skeletal-muscle function is not likely a result of a specific behavior but instead due to alterations in molecular clock function. We also found that the deficits recorded for whole-muscle tissue were present at the single-cell level. These findings are consistent with the concept that proper function of the molecular clock in skeletal-muscle fiber/cell is critical for maintenance of muscle function.

Molecular Clock and Mitochondria in Skeletal Muscle.

We also detected significant mitochondrial pathologies in skeletal muscles of the ClockΔ19 and Bmal1−/− mice. We found a 40% reduction in mitochondrial volume, and the remaining mitochondria displayed morphological defects characterized by swelling and disrupted cristae. These initial observations from EM analyses were strengthened by our results that mitochondria from both gastrocnemius and diaphragm muscles of Bmal1−/− mice were functionally impaired as indicated by a reduced RCR. In contrast, we can conclude that the mitochondrial phenotype was independent of MyoD because it was not observed in the muscles of MyoD−/− mice.

On the basis of the well-established role of PGC-1 in the regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle, we propose that dysregulation of the PGC-1 family is a potential molecular link to the mitochondrial pathology observed in skeletal muscle of ClockΔ19 and Bmal1−/− mice (31). Recent studies have demonstrated that SIRT1 contributes to the control of the molecular clock (32–34), and PGC-1 and SIRT1 have been shown to interact to regulate mitochondrial biogenesis and fatty acid oxidation in skeletal muscle (35). The results from this study found that Pgc-1β expression was no longer circadian in the muscle of ClockΔ19 mice and that Pgc-1α expression, although not circadian, was significantly decreased in muscle of both ClockΔ19 and Bmal1−/− mice. These results are in agreement with recent finding of Liu et al. that Pgc-1α expression cycles in skeletal muscle (36). Taken together, our results confirm that Pgc-1 expression is circadian in skeletal muscle and becomes down-regulated and/or nonrhythmic in muscle of ClockΔ19 and Bmal1−/− mice. These findings suggest that interactions between the PGC-1 coactivators and SIRT1 might link the molecular clock with daily maintenance of fundamental metabolic/mitochondrial pathways in skeletal muscle.

In summary, the results presented here demonstrate that cell structure and function of skeletal muscle is impaired in ClockΔ19 and Bmal1−/− mice. Evidence is growing that links inflammation, cancer, cardiovascular disease, sleep disorders, and metabolic disease with altered expression of the molecular clock in peripheral tissues (37–39). Thus, the significant force and metabolic deficits in the muscle of ClockΔ19 and Bmal1−/− mice open the possibility that the profound peripheral weakness and fatigue seen in chronic diseases may result from disruption of proper circadian factor expression in muscle.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals as approved by the University of Illinois and University of Kentucky Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees. In addition to C57BL/6J or BALB/c mice (Jackson Laboratory), designated as wild type for each genotype, three mutant strains of mice were used in the current study: homozygous ClockΔ19 (isogenic C57BL/6J) (40), homozygous MOP3/Bmal1−/− null mutant (congenic on C57BL/6J) (41), and homozygous MyoD−/− null mutant (isogenic BALB/c) (42). Mice were housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled room maintained on a 12-h light–dark cycle with food and water ad libitum.

Muscle Function.

Maximum isometric tetanic force was determined in EDL muscles from mice [wild type (n = 4), ClockΔ19 (n = 7), Bmal1−/− (n = 3), and MyoD−/− (n = 4)] following procedures described previously (43).

Single-Fiber Force Measurements.

Single chemically permeabilized fibers (n = 20 fibers of wild type; n = 7 fibers of Bmal1−/−) were prepared from EDL muscles using a technique similar to that described by Campbell and Moss (44). Experimental records were acquired and analyzed using SLControl software (14).

Electron Microscopy.

Mice were anesthetized with an i.p. injection of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). Skeletal muscle was fixed by transcardial perfusion with ice-cold 2% paraformaldehyde/4% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) and 130 mM NaCl. Perfusion-fixed samples were taken to the microscopy center for further processing. Thin sections were cut and stained, and images were obtained for quantification of mitochondrial volume, assessment of mitochondrial ultrastructure, and myofilament organization.

Mitochondrial Volume.

The volume of the muscle fiber occupied by mitochondria in skeletal muscle from wild-type, ClockΔ19, Bmal1−/−, and MyoD−/− mice (n = 5/genotype) was determined using the electron microscopy point-counting method as described by Eisenberg and Salmons (45). To prevent analytical bias, all images were coded and put in random order before counting.

Mitochondrial Respiration.

Mitochondrial isolation and respiration from skeletal muscle was performed as described by Singh et al. (46). For each experiment, fresh mitochondria were isolated and used within 3 h.

Gene Expression Analysis.

Wild-type (C57BL/6J) mice were entrained to a light:dark (LD) 12:12 cycle for 2 wk, placed in light-tight boxes on a LD 12:12 cycle for 4 wk, and then released into constant darkness (DD). Starting 30 h after entry into DD (CT18), skeletal muscles from five mice were collected every 4 h for 48 h. At time points CT34 through CT58 in DD, muscles from age-matched ClockΔ19 mice that had been treated with the same light protocol as the wild-type mice were collected. The muscles were removed from each hind leg and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Real-time quantitative PCR using TaqMan (Applied Biosystems) assays was used to validate the gene expression data generated from microarray analysis as previously reported for MyoD, Pgc-1α, and Pgc-1β (7).

Western Blots.

Skeletal muscle was homogenized in lysis buffer, and samples were electrophoresed on 10% SDS/PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane (Millipore) as described previously (43). Membranes were incubated with a polyclonal antibody against MyoD (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or γ-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich) followed by incubation with alkaline phosphatase-linked anti-rabbit antibody or anti-mouse antibody (Sigma-Aldrich). The membrane was exposed to ECF substrate (Amersham Bioscience), and signals were analyzed using a PhosphorImager (Storm 860; Amersham Bioscience).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay.

Skeletal muscles were collected at the appropriate circadian time under constant dark conditions as described above (Gene Expression Analysis). Muscle tissues were homogenized in 1% formaldehyde buffer, and nuclei were isolated on the basis of protocols adapted from a method described by Ripperger and Schibler (47). Samples were incubated overnight at 4 °C with BMAL1 or CLOCK antibody (Abcam) or nonspecific IgG or no antibody as controls. After clearing, samples were treated with Proteinase K (10 mg/mL) and DNA recovered for PCR. Primers were designed to amplify an ∼100-bp region within either the MyoD CE or DRR using AccuPrime Pfx Taq polymerase (Invitrogen).

Construction of the 6.8MyoD and CE-6.8MyoD Reporter Vectors.

We used the MD6.8-lacZ clone (gift from S. Tapscott, The Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA) as a template to clone 6.8 kb of upstream 5′ flanking sequence into the pGL3basic vector (Promega). Mouse genomic DNA was then used as a template to clone the CE, which was subsequently inserted upstream of the 6.8-kb flanking sequence to produce the CE-6.8MyoD reporter vector. The sequence of the CE-6.8MyoD clone was verified by sequencing before being used in transient transfection experiments. The Per1 reporter vector, as previously described by Wilsbacher et al. (48), was used as a positive control in the transfection experiments.

Transfection Experiments.

C2C12 cells (n = 6–8/condition) were transiently transfected with expression vectors for Clock, Bmal1, or ClockΔ19 cDNAs with either the Per1 reporter vector or the 6.8MyoD or CE-6.8MyoD reporter vector using the Fugene6 reagent (Roche). The pRL vector (Promega) was used to control for transfection efficiency. Cells were collected 24–48 h after transfection and lysed with the passive lysis buffer, and luciferase activities were measured using the Dual Luciferase Assay System according to the manufacturer's directions (Promega).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. S. Tapscott (The Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA) and Dr. D. Goldhamer (University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT) for MyoD reagents, Dr. C. Bradfield (The McArdle Laboratory for Cancer Research, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI) for the Bmal1−/− (Mop3−/−) mice, Dr. M. Rudnicki (Ottawa Health Research Institute, Ottawa, ON, Canada) for the MyoD−/− mice, Dr. F. Andrade for helpful discussions, and M. G. Engle and L. Juarez for help with electron microscopy. Research was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants AR050717 (to K.A.E.), AR053641 (to J.J.M.), and HL45721 (to M.B.R.); the Novartis Research Foundation (J.B.H. and J.R.W.); the NIH National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (B.R.); NIH Grant U01 MH61915 (to J.S.T.); and Silvio O. Conte Center NIH Grant P50 MH074924 (to J.S.T.). J.S.T. is an investigator and E.L.M. was an associate at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1014523107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Bell-Pedersen D, et al. Circadian rhythms from multiple oscillators: Lessons from diverse organisms. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:544–556. doi: 10.1038/nrg1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green CB, Takahashi JS, Bass J. The meter of metabolism. Cell. 2008;134:728–742. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emerson KJ, Bradshaw WE, Holzapfel CM. Concordance of the circadian clock with the environment is necessary to maximize fitness in natural populations. Evolution. 2008;62:979–983. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00324.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woelfle MA, Ouyang Y, Phanvijhitsiri K, Johnson CH. The adaptive value of circadian clocks: An experimental assessment in cyanobacteria. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1481–1486. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lowrey PL, Takahashi JS. Mammalian circadian biology: Elucidating genome-wide levels of temporal organization. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2004;5:407–441. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.5.061903.175925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stratmann M, Schibler U. Properties, entrainment, and physiological functions of mammalian peripheral oscillators. J Biol Rhythms. 2006;21:494–506. doi: 10.1177/0748730406293889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCarthy JJ, et al. Identification of the circadian transcriptome in adult mouse skeletal muscle. Physiol Genomics. 2007;31:86–95. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00066.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller BH, et al. Circadian and CLOCK-controlled regulation of the mouse transcriptome and cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:3342–3347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611724104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tapscott SJ. The circuitry of a master switch: Myod and the regulation of skeletal muscle gene transcription. Development. 2005;132:2685–2695. doi: 10.1242/dev.01874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asakura A, Lyons GE, Tapscott SJ. The regulation of MyoD gene expression: Conserved elements mediate expression in embryonic axial muscle. Dev Biol. 1995;171:386–398. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldhamer DJ, et al. Embryonic activation of the myoD gene is regulated by a highly conserved distal control element. Development. 1995;121:637–649. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.3.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen JC, Goldhamer DJ. The core enhancer is essential for proper timing of MyoD activation in limb buds and branchial arches. Dev Biol. 2004;265:502–512. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen JC, Ramachandran R, Goldhamer DJ. Essential and redundant functions of the MyoD distal regulatory region revealed by targeted mutagenesis. Dev Biol. 2002;245:213–223. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell KS, Moss RL. SLControl: PC-based data acquisition and analysis for muscle mechanics. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H2857–H2864. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00295.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eisenberg BR, Kuda AM, Peter JB. Stereological analysis of mammalian skeletal muscle. I. Soleus muscle of the adult guinea pig. J Cell Biol. 1974;60:732–754. doi: 10.1083/jcb.60.3.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turek FW, et al. Obesity and metabolic syndrome in circadian Clock mutant mice. Science. 2005;308:1043–1045. doi: 10.1126/science.1108750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kondratov RV, Kondratova AA, Gorbacheva VY, Vykhovanets OV, Antoch MP. Early aging and age-related pathologies in mice deficient in BMAL1, the core component of the circadian clock. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1868–1873. doi: 10.1101/gad.1432206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martino TA, et al. Circadian rhythm disorganization produces profound cardiovascular and renal disease in hamsters. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294:R1675–R1683. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00829.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tapscott SJ, et al. MyoD1: A nuclear phosphoprotein requiring a Myc homology region to convert fibroblasts to myoblasts. Science. 1988;242:405–411. doi: 10.1126/science.3175662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blais A, et al. An initial blueprint for myogenic differentiation. Genes Dev. 2005;19:553–569. doi: 10.1101/gad.1281105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Megeney LA, Kablar B, Garrett K, Anderson JE, Rudnicki MA. MyoD is required for myogenic stem cell function in adult skeletal muscle. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1173–1183. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.10.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Staib JL, Swoap SJ, Powers SK. Diaphragm contractile dysfunction in MyoD gene-inactivated mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;283:R583–R590. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00080.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amack JD, Reagan SR, Mahadevan MS. Mutant DMPK 3′-UTR transcripts disrupt C2C12 myogenic differentiation by compromising MyoD. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:419–429. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200206020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dedkov EI, Kostrominova TY, Borisov AB, Carlson BM. MyoD and myogenin protein expression in skeletal muscles of senile rats. Cell Tissue Res. 2003;311:401–416. doi: 10.1007/s00441-002-0686-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marsh DR, Criswell DS, Carson JA, Booth FW. Myogenic regulatory factors during regeneration of skeletal muscle in young, adult, and old rats. J Appl Physiol. 1997;83:1270–1275. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.4.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen JC, Love CM, Goldhamer DJ. Two upstream enhancers collaborate to regulate the spatial patterning and timing of MyoD transcription during mouse development. Dev Dyn. 2001;221:274–288. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Montaigu A, Tóth R, Coupland G. Plant development goes like clockwork. Trends Genet. 2010;26:296–306. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.González E, Messi ML, Delbono O. The specific force of single intact extensor digitorum longus and soleus mouse muscle fibers declines with aging. J Membr Biol. 2000;178:175–183. doi: 10.1007/s002320010025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lynch GS, Hinkle RT, Chamberlain JS, Brooks SV, Faulkner JA. Force and power output of fast and slow skeletal muscles from mdx mice 6-28 months old. J Physiol. 2001;535:591–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00591.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bunger MK, et al. Progressive arthropathy in mice with a targeted disruption of the Mop3/Bmal-1 locus. Genesis. 2005;41:122–132. doi: 10.1002/gene.20102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scarpulla RC. Transcriptional paradigms in mammalian mitochondrial biogenesis and function. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:611–638. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Asher G, et al. SIRT1 regulates circadian clock gene expression through PER2 deacetylation. Cell. 2008;134:317–328. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakahata Y, et al. The NAD+-dependent deacetylase SIRT1 modulates CLOCK-mediated chromatin remodeling and circadian control. Cell. 2008;134:329–340. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramsey KM, et al. Circadian clock feedback cycle through NAMPT-mediated NAD+ biosynthesis. Science. 2009;324:651–654. doi: 10.1126/science.1171641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fulco M, Sartorelli V. Comparing and contrasting the roles of AMPK and SIRT1 in metabolic tissues. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:3669–3679. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.23.7164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu C, Li S, Liu T, Borjigin J, Lin JD. Transcriptional coactivator PGC-1alpha integrates the mammalian clock and energy metabolism. Nature. 2007;447:477–481. doi: 10.1038/nature05767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duez H, Staels B. The nuclear receptors Rev-erbs and RORs integrate circadian rhythms and metabolism. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2008;5:82–88. doi: 10.3132/dvdr.2008.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maywood ES, O'Neill J, Wong GK, Reddy AB, Hastings MH. Circadian timing in health and disease. Prog Brain Res. 2006;153:253–269. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)53015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takahashi JS, Hong HK, Ko CH, McDearmon EL. The genetics of mammalian circadian order and disorder: Implications for physiology and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:764–775. doi: 10.1038/nrg2430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vitaterna MH, et al. Mutagenesis and mapping of a mouse gene, Clock, essential for circadian behavior. Science. 1994;264:719–725. doi: 10.1126/science.8171325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bunger MK, et al. Mop3 is an essential component of the master circadian pacemaker in mammals. Cell. 2000;103:1009–1017. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00205-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rudnicki MA, Braun T, Hinuma S, Jaenisch R. Inactivation of MyoD in mice leads to up-regulation of the myogenic HLH gene Myf-5 and results in apparently normal muscle development. Cell. 1992;71:383–390. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90508-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hornberger TA, Mateja RD, Chin ER, Andrews JL, Esser KA. Aging does not alter the mechanosensitivity of the p38, p70S6k, and JNK2 signaling pathways in skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:1562–1566. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00870.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Campbell KS, Moss RL. History-dependent mechanical properties of permeabilized rat soleus muscle fibers. Biophys J. 2002;82:929–943. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75454-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eisenberg BR, Salmons S. The reorganization of subcellular structure in muscle undergoing fast-to-slow type transformation. A stereological study. Cell Tissue Res. 1981;220:449–471. doi: 10.1007/BF00216750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singh IN, Sullivan PG, Deng Y, Mbye LH, Hall ED. Time course of post-traumatic mitochondrial oxidative damage and dysfunction in a mouse model of focal traumatic brain injury: Implications for neuroprotective therapy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:1407–1418. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ripperger JA, Schibler U. Rhythmic CLOCK-BMAL1 binding to multiple E-box motifs drives circadian Dbp transcription and chromatin transitions. Nat Genet. 2006;38:369–374. doi: 10.1038/ng1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilsbacher LD, et al. Photic and circadian expression of luciferase in mPeriod1-luc transgenic mice invivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:489–494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012248599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.