Abstract

Purpose: This article systematically examines arterial spin labeling (ASL) as a flow quantification technique through theoretical simulation, in vitro, and in vivo experiment. The authors present a novel imaging pulse sequence design consisting of a single ASL magnetization preparation followed by Look-Locker-like image readouts. Bloch-equation-based modeling has been developed and validated using a hemodialyzer as a tissue-mimicking flow phantom.

Methods: After the single in-plane slice-selective double inversion magnetization preparation, multiple TFL readouts are acquired with linear k-space ordering, causing a signal variation that depends on through-slice flow velocity. Computer simulations were performed to assess the behavior of the flow-dependent ASL signal as a function of varying imaging parameters. The signal was optimized by choosing imaging parameters that maximize the simulated flow-sensitive signal. Furthermore, a hemodialyzer which mimics blood flow in human tissues was tested with a wide range of flow rates. An exponential curve fitting of the flow-sensitive dynamics to the model derived from Bloch equations provides a method to estimate through-slice velocity for varying flow rates on the hemodialyzer and in vivo human brain.

Results: The flow dependency of the ASL signal and the sensitivity of the ASL signal to imaging parameters were demonstrated. Experimental results from a hemodialyzer when fitted with a Bloch-equation-based model provide flow measurements that are consistent with ground truth velocities. Human brain velocity mapping was obtained as well.

Conclusions: The results provide evidence that the proposed pulse sequence design is an effective technique to measure total fluid flow through image voxels. The unique combination of the two main features, multiple-image readout after a single ASL preparation and linear acquisition ordering in the phase encoding direction in TFL imaging, make this technique an appealing flow imaging method to quantify through-plane flow in a time-efficient manner.

Keywords: arterial spin labeling, perfusion imaging, flow velocity, data acquisition

INTRODUCTION

Arterial spin labeling (ASL) is a perfusion magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technique that generates flow-sensitive signal by manipulating the endogenous water spins in the flowing arterial blood.1 The flow contrast in ASL flow-sensitive signal is usually created by a relative inversion between inflowing spins and stationary in-slice nonflowing spins. For example, by acquiring tag and control images preceded by inflow-magnetization-inversion and inflow-magnetization-noninversion preparation, respectively, the difference between the two reflects only the signal from inflowing magnetization with static magnetization being subtracted out.

Since the flow contrast comes from the freely diffusible water without any contrast agent administration, ASL techniques are safe and repeatable. This property allows multiple (repeated) flow assessments, which could be especially useful for procedures such as thermal therapy treatment, where tissue perfusion affects the procedure and may change due to the procedure. For MRI guided high intensity focused ultrasound (MRgHIFU) in particular, the widely used Pennes’ bioheat transfer equation (BHTE) is used as the fundamental governing equation to model the effects of heat deposition and dissipation in tissues. The formulation includes terms for thermal conductivity and an effective perfusion, which represents the rate at which blood flow removes heat from a local tissue region. However, tissue properties, particularly perfusion, are known to change over the course of a thermal therapy treatment.2, 3 Detecting perfusion changes during a thermal therapy treatment would enable adjustment of treatment parameters to achieve a more efficacious therapy.

After the initial introduction of ASL by Detre and William,1, 4 various techniques5, 6, 7, 8, 9 have been developed over the past decade to improve the performance, including pulsed ASL (pASL) that employs short pulses proximal to the imaging slice to label the blood magnetization in the feeding artery. Of the different pASL techniques, flow-sensitive alternating inversion recovery10 (FAIR) is one of the most frequently used tagging strategies. A FAIR flow-sensitive image is obtained by performing an inversion recovery sequence twice: Once with and once without a slice-selection gradient to label the arterial spins. As a derivative of FAIR, uninverted flow-sensitive alternating inversion recovery11 (UNFAIR) keeps the static signal noninverted in the volume of interest by applying an additional inversion pulse right after the first inversion pulse. A similar technique called in-plane slice-selective double inversion (IDOL)-prepared ASL was proposed recently by Jahng et al.12 to minimize the flow-sensitive signal contamination from residual static signal and compensate for potential magnetization transfer (MT) effects. Generally, multiple signal averages are needed to overcome the intrinsic low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), which has been the major limiting factor that hampers the extensive application of ASL. To overcome this issue, methods involving a Look-Locker-like acquisition following the labeling magnetization preparation to monitor the temporal dynamics of blood inflow have been proposed.13, 14, 26 In inflow turbo-sampling FAIR,13 FAIR preparation was combined with Look-Locker image readout by acquiring a series of images after each labeling pulse using echo planer imaging (EPI) readouts. Quantitatively, images at multiple inversion times (TIs) are required to improve the accuracy of the perfusion quantification, especially for patients with atherosclerosis where the distribution of transit times varies greatly in the brain.14 Blood volume could also be estimated using LL-EPI readout as reported by Brookes et al.26

EPI is the most widely used imaging pulse sequence to measure cerebral blood flow (CBF) in ASL due to its ability to perform single-shot fast image acquisition and its high SNR for a given imaging time.12, 26 However, artifacts, including susceptibility and Nyquist ghosting, limit its application in imaging other tissues. Other fast imaging sequences such as balanced steady-state free precession and partial-Fourier fast spin echo have also been implemented in conjunction with ASL.15 In addition, centric-ordered turbo-FLASH (TFL) imaging readout12, 16, 17 has been investigated because of its insensitivity to susceptibility effects and reasonably fast imaging time. Centric-ordered readout has been used16, 17, 18 to obtain the highest weighting in the reconstructed image on the data points at the beginning of the acquisition. In this work, instead of centric ordering, a linear phase encoding scheme (center of k-space being acquired in the midway) is employed to estimate flow velocity.

In addition to obtaining cerebral perfusion parameters for the study of vascular related diseases and functional MRI, the flow-sensitive signal from ASL can also be modeled to obtain quantities that indicate the flow velocity in the tissue of interest.15 The quantification results from various ASL magnetization preparation and modeling schemes should yield, in principle, the same perfusion values because perfusion is a biological parameter. However, as recently reported by Çavuşoğlu et al.,19 the different tagging strategies can result in perfusion measurement variations by as much as 18%. The correspondence between measured and actual perfusion can be limited by several confounding factors, such as transit delay, fluid spin-lattice relaxation time, and flow-sensitive difference signals.20 Moreover, the flow-sensitive difference signals acquired using different imaging parameters or imaging sequences can lead to greater errors if conventional, but inappropriate, flow models are used. Conversely, the quantification process should avoid dependence on imaging sequences or parameters by incorporating the characteristic of the sequences and parameters in the modeling.

ASL has been mostly demonstrated in the brain,8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 where localized changes in CBF are estimated to study the physiological status of brain tissue. Other in vivo applications include cardiac,21 lung,22 and kidney23 perfusion imaging. Although ASL techniques have been validated extensively in human studies and some animal studies,16 application to a tissue-mimicking flow phantom with varying flow rates has rarely been performed. To our knowledge, only one paper was published on analytical validation of perfusion imaging on a phantom composed of a syringe filled with plastic beads and small plastic tubes using the Q2TIPS sequence and a kinetic model.24

In this work, we present a new pulse sequence design that combines TFL imaging and Look-Locker-like13, 14 readout at multiple inversion times in a single scan and validate the measurements using a hemodialyzer as a tissue-mimicking flow phantom. Taking advantage of multiple images along the inversion recovery curve and using a linear phase encoding acquisition order for each image, the rate at which flow passes through a point can be determined. The general low SNR of the ASL images will be improved by the higher time-efficiency of the Look-Locker readout strategy. A matching result is found between simulation and flow distribution in the hemodialyzer at varying flowing conditions. A human brain flow velocity mapping was obtained as well.25

THEORY

Imaging sequence

ASL magnetization preparation is performed using IDOL.12 Specifically, two slice-selective inversion pulses centered on the imaged slice are utilized to invert the spins in the inflowing blood while leaving spins in the slice noninverted. These pulses consist of a global inversion followed by a slice-selective inversion over the imaging slice to achieve spin tagging [see Fig. 1a]. For the control scan, two equivalent slice-selective inversion pulses are applied to the imaging slice to compensate for potential MT effects and to leave the static spins noninverted for both tagging and control. The contamination of residual static signal in the resulting difference signal is therefore minimized. As the tagged spins flow into the imaging slice, a sequence of TFL images are acquired separated by a fixed time delay (TD). For each TFL image, the k-space phase encoding lines are acquired with excitation by a train of α excitation pulses. The TD is selected as the wait time between each image to allow the washout of the tagged spins that have experienced the excitation pulses from the previous image readout. However, for ultraslow flow, the TD required for complete washout is too long such that the ASL contrast is diminished by the T1-recovery process. In this ultraslow-flow case, the memory from prior pulses needs to be considered for later readouts.

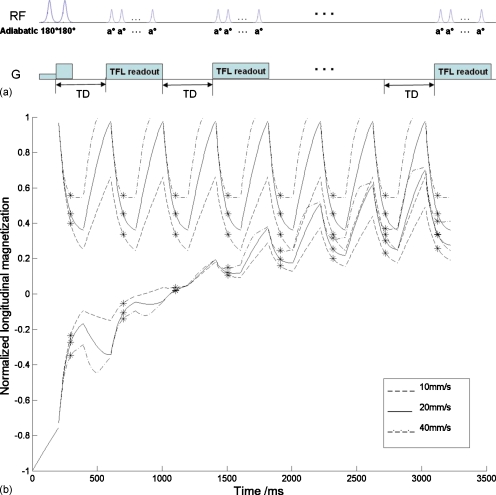

Figure 1.

Schematic diagrams of the tagging imaging pulse sequence along with the evolution of the longitudinal magnetization of tag and control inflowing fluid. (a) IDOL tagging inversion is followed by a series of TFL image readouts. Depending on the fluid (blood) T1, TD and the number of images acquired along the curve can be adjusted. (b) Longitudinal magnetization of tag (bottom lines) and control (top lines) inflowing fluid. With the simulation parameters imaging slice thickness=5 mm, TD=200 ms, T1=1450 ms, and flip angle=15°, fast flow 40 mm∕s (dashed-dotted line) guarantees the initial magnetization originates from the inversion recovery curve, whereas the initial magnetization of slow flow 10 mm/s (dashed line) must incorporate the signal evolution from previous readouts. For these parameters, 20 mm/s (solid line) seems to be the critical velocity below which the impact of preceding readout pulses needs to be taken into account. Eight images were simulated after single ASL preparation. A marker is indicated at the point where the signal from the center of k-space is acquired with linear phase encoding ordering.

The schematic diagram of (a), the imaging pulse sequence, along with (b), the corresponding signal evolution of longitudinal magnetization from both tag and control inflow fluid, is presented in Fig. 1. In Fig. 1b, the signal plotted is the normalized longitudinal magnetization at velocities of 10, 20, and 40 mm∕s obtained using the simulation parameters: Imaging slice thickness=5 mm, TD=200 ms,T1=1450 ms, and flip angle (α)=15°. After tagging, images are acquired while the inverted flowing magnetization recovers toward the fully relaxed state. Similarly, the control signal evolution due to the excitation RF pulses is demonstrated in Fig. 1b as well, with the initial magnetization being fully relaxed. Flow signal differs as a function of velocity because signal saturation depends on the number of excitation pulses experienced as the magnetization passes through the slice, which in turn depends on the flow velocity. Fast flow [40 mm∕s in Fig. 1b] guarantees that the initial magnetization originates from the inversion recovery curve, whereas the initial magnetization of ultraslow flow [10 mm∕s in Fig. 1b] is determined by signal evolution from previous readouts. Under this particular condition, 20 mm∕s appears to be the critical velocity, above which the memory from the RF pulses from the previous readout need not be considered. The flow information encoded in the train of readout excitation pulses is captured by linear k-space ordering. In Fig. 1b, a marker is placed in the center of each image readout, at the point where the signal from the center of k-space is acquired with linear phase encoding ordering.

Modeling

With TFL imaging readout, the theoretical expression of the magnetization evolution of the inflowing ASL control and tagging signals are derived based on the Bloch equations. The fluid signal behavior can be modeled by considering the impact of a varying number of α excitation pulses on the freshly inflowing magnetization as a function of flow velocity. Since the number of α excitation pulses experienced by the fluid changes with different flow velocities, the derivation of an expression for the inflow signal provides a model to estimate velocity quantitatively. Mathematically, the effects of excitation pulses on the flow signal in each repetition time (TR) are modeled by three processes: Excitation, longitudinal magnetization recovery, and flow shifting. In the modeling, each slice is subdivided into K partitions, where K=D∕(v⋅TR), D is the slice thickness, v is the estimated flow velocity, and TR is the time interval between the excitation pulses. K is therefore the number of RF pulses seen by the spins passing through the slice. For each TR, starting with the initial magnetization Mzj(t0), j=1,2,…,K, the fluid magnetization goes through the following processes:

- At jth excitation

(1) - Magnetization recovery and flow shifting after jth excitation

where E1=exp(−TR∕T1blood), M0 is the fully relaxed longitudinal magnetization, Mẕblood(t) is the flow (blood) magnetization outside imaging slice but within the global inversion region, and j is the spatial index of the number of subslices. The routine is then iterated Ny times until all the phase encoding k-space lines are acquired, with image readout time of Ny⋅TR for each image. The difference between tagging and control signals lies in the expression for the initial magnetization Mzj(t0), i.e.,2 (3)

Flow-sensitive signal is obtained by taking the difference of control and tag images, where each signal is formed by averaging from all K subslices.(4)

Because of the existence of fluid exchange between intrafiber and extrafiber compartments in a hemodialyzer, which is demonstrated in the simulation, a two-compartment model that provides estimation of the two velocities in the hemodialyzer is developed. Mathematically,

| (5) |

where Sintra and Sextra represent the signal of intrafiber and extrafiber, respectively, vintra and vintra are the flow velocities in the intrafiber and extrafiber, respectively, η is the relative proportion of the extrafiber compartment, and α is the flip angle.

METHODS

Simulation

All the simulations were made and displayed using algorithms developed in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA). Simulations were performed to assess the behavior of the flow-dependent ASL signal as a function of varying imaging parameters. First of all, the impact of varying flow rates, i.e., K in Eqs. 1, 2, on inflowing tag and control signals was studied. Signal evolution of longitudinal magnetization of flowing spins were simulated at three flow rates ranging from 20 to 60 mm∕s. The simulation imaging parameters were TR=3 ms, α=15°, TD=200 ms, Ny=64, T1blood|3T=1.45 s, slice thickness=5 mm, and number of images along the curve=8. The ASL signal was then obtained as the difference between control and tag signals. The impacts of different parameters, such as α in Eq. 1 and T1 in Eq. 2 on resulting flow-sensitive signals were explored. To determine the effects of α, signals corresponding to four α’s varying from 5° to 20° were simulated at the flow velocity of 40 and 120 mm∕s. The remaining parameters were kept the same as the previous simulation. Similarly, the flow-sensitive signal evolutions were simulated at four T1 ranging from 500 to 2000 ms. Furthermore, the sensitivity of the flow-sensitive ASL signal to varying flow velocity was further visualized as a function of TI and a comparison to the actual hemodialyzer experimental results was presented. Based on the simulations, optimal parameters can be selected to maximize the flow signals of the hemodialyzer and in vivo experiments.

Hemodialyzer imaging

A hemodialyzer, which has thousands of fibers, each with a diameter on the order of hundreds of microns, has properties that may be useful in mimicking human tissue flow and can be tested with a wide range of flow rates. In this study, all images were acquired on a Siemens MAGNETOM TIM Trio 3 T MRI scanner with 40 mT∕m gradients and a slew rate of 200 mT∕m∕ms. A commercially available hemodialyzer (Baxter Xenium-190) with Gd-BOPTA water pumped through the fibers unidirectionally was imaged using a 12-channel head coil (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). To validate the complete cancellation of static signal between tag and control, a static water phantom was set next to the dialyzer and imaged in the same field of view. A nonpulsatile pump circulated doped water (T1=1.45 s) at pumping rates of 45, 90, 135, and 180 cc∕min through the semipermeable fibers in the hemodialyzer. Using the proposed imaging sequence, single-slice two-dimensional transversal images of the hemodialyzer were acquired at a series of TI=[200, 600, 1000, 1400, 1800, 2200, 2600, 3000] ms in one scan with the following parameters: TR=3 ms, α=15°, TD=200 ms, and voxel size=3.1×3.1×5 mm3. Tagging and control scans were interleaved. Furthermore, a leading edge method was used to estimate the flow rates within the hemodialyzer by measuring the leading edge of the fluid as a function of TI. A single coronal slice was acquired using the same pulse sequence to validate the quantification result. Two 180° hyperbolic-scent adiabatic inversion pulses with duration of 20 ms were used for tagging and control preparation. To avoid any contamination from imperfection in the inversion pulse slice profile, 4.5 mm extra inversion thickness on each side was applied on the imaging slice in the IDOL preparation. A region of interest (ROI) was drawn over the hemodialyzer cross-sectional flow-sensitive image at each TI to obtain an averaged ASL signal.

The resulting flow-sensitive ASL time series data were input into a nonlinear least-squares fitting routine written in MATLAB. The model could provide simultaneous estimation of both flow velocities for the intrafiber and extrafiber compartments in a single measurement. A comparison of simulation and experiment was made to indicate that the flow velocities in the two compartments are different. It was shown that the hemodialyzer cross-section is composed of 30% intrafiber area and 70% extrafiber area. Therefore, an averaged velocity can be determined based on the estimated intrafiber and extrafiber velocities.

In vivo imaging

This study was approved by the institutional review board. One healthy subject was imaged using the same pulse sequence at a series of TI=[700, 1000, 1300, 1600, 1900, 2200] ms in a single scan. Single-slice two-dimensional transversal images of the brain were scanned with the following imaging parameters: TR=3 ms, α=15°, matrix size=128×128, pixel size=2×2×3.5 mm3, BW=490 Hz∕Px, and tagging thickness=10 mm. The imaging slice was located at the corpus callosum while the tagging of the inflow was centered on the neck so that the heart was included in the inversion region. An 8 s time interval was introduced between the interleaved tag∕control scans to avoid any impact from previous pulses. Altogether four measurements of tag∕control pairs were acquired in 1 min. Pairwise subtraction between tagging and control images was performed to obtain the averaged flow-sensitive images. In addition, a nonlinear least-squares fitting routine was applied to the measured data series of difference signals to estimate flow velocities. An estimate of fully relaxed magnetization of arterial blood M0 is obtained by acquiring a proton density-weighted gradient echo sequence with TR=3000 ms and TE=8 ms and a correction for proton density and relaxation rate of gray matter was applied.19 A literature T1 value of blood 1684 ms (Ref. 19) is used in the modeling.

RESULTS

Simulation

Figure 2 illustrates the normalized longitudinal magnetization evolution of inflowing tag and control signals at three flow velocities, with the assumption of the lowest velocity being fast enough that each time the imaging starts with freshly inflowing spins. It is clear that the inversion recovery of tagging magnetization and the noninverted control magnetization are the source of the contrast. As the flow rate changes, the impact of the series of α excitation pulses on the inflowing spins is visualized as different trajectories corresponding to different velocities. The tag signal of the lower velocity tends to deviate further from the inversion recovery curve, while the tag signal of the faster velocity tends to eventually stay closer to the inversion recovery curve. In other words, spins with higher flow rate are less affected by the excitation pulse train than those with a slower flow rate since fast moving spins experience fewer excitation pulses. A similar situation is found for the control signals. This flow-dependency property of the signal is the principal foundation of the proposed technique.

Figure 2.

Evolution of longitudinal magnetization for tagging (bottom lines) and control (top lines) scans, respectively. The simulation parameters were TR=3 ms, α=15°, TD=200 ms, Ny=64, T1=1.45 s, slice thickness=5 mm, matrix size=64×64, and number of images along the curve=8. At each TI, three velocities [20, 40, 60] mm∕s were simulated. The case with highest velocity stays closest to the main magnetization curve, while the flow with the lowest velocity deviates further away from the main magnetization curve. It is assumed that the lowest velocity being fast enough that each time the imaging starts with freshly inflowing spins.

The effect of α on flow-sensitive signal is demonstrated in Fig. 3. At extrafiber velocities of 40 and 120 mm∕s, the maximum ASL signal is achieved at α of 10° and 15°, respectively. It is evident that the optimal α varies as a function of velocity.

Figure 3.

Simulation of normalized flow-sensitive signals at an extrafiber velocity of (a) 40 and (b) 120 mm∕s. The maximum flow signal is achieved at α of 10° and 15°, respectively. The rest of the parameters were kept the same as in Fig. 2. At different flow velocities, α can be adjusted to obtain the maximum flow-sensitive signal.

In Fig. 4, normalized flow-sensitive signal with different T1 are shown. The normalized flow-sensitive signal increases as T1 increases accordingly, which demonstrates that the ASL signal gains as T1 lengthens. This indicates that the ASL signal could benefit from a higher magnetic field.

Figure 4.

Simulated flow-sensitive signals as a function of fluid spin-lattice relaxation time T1=[1000, 1500, 2000, 2500] ms. Using the same parameters, maximum flow-sensitive signal for an extrafiber flow velocity of 40, α=10° is achieved at T1 of 1450 ms.

Hemodialyzer imaging

Images from a transverse slice of the hemodialyzer and static water phantom acquired at TI=[200, 600, 1000, 1400, 1800, 2200, 2600, 3000] ms are shown in Fig. 5. Tag, control, and difference images are represented in the top, middle, and bottom rows, respectively. Within each image, the largest area corresponds to the cross-section of the static water phantom; the cross-section of the hemodialyzer with flow into the magnet bore is located at the upper left corner, while the cross-section of the thin tubing with fluid flowing out of the magnet bore appears in the upper right of each image. The complete cancellation of static signal shown in the bottom row indicates that the ASL signal shown is purely flow-dependent. The general signal drop off within the hemodialyzer indicates that the flow direction in the hemodialyzer is from left to right in the figure. The flow is in the opposite direction in the thin tubing.

Figure 5.

Representative eight single-slice images acquired at [200, 600, 1000, 1400, 1800, 2200, 2600, 3000] ms after the ASL magnetization inversion with a pumping rate of 200 cc∕min. Three rows correspond to tag (upper row), control (middle row), and difference (lower row) images. Within each image, cross-sections of a Siemens water phantom (biggest cross-section), the hemodialyzer (arrow head), and the thin tube (arrow) are depicted. Static water signals cancel out completely in the flow-sensitive difference images. The dialyzer signal cancels in the first image because it took longer than 200 ms for the tagged flow to enter the imaged slice.

To estimate flow velocity, the ROI-based averaged signal intensities from the cross-section of the hemodialyzer were evaluated and shown in Fig. 6, presented in solid lines. The signals show an approximately proportional relationship to the corresponding pumping rates. Compared to the simulated ASL signal (dashed lines), the simulations agree reasonably well with the experimental results except for the initial signal increment. Since a distance was introduced between the tagging and imaging regions to minimize the effect of imperfect inversion near the edges, the signal drop in the initial period is believed to be caused by the incomplete inflow of tagged spins.

Figure 6.

Comparison of simulated ASL signal (dashed lines) and experimental results (solid lines). Experimental flow-sensitive signals were averaged over the cross-sections of hemodialyzer at four pumping rates [45, 90, 135, 180] cc∕min at a TD of 200 ms and α of 15°. Simulated flow-sensitive signal is calculated as the difference of control and tagging signal (see Fig. 2) using the same parameters as in the experiment. Overall, there is a reasonably good agreement between the two and the only discrepancy lies in the initial signal increment which is due to the incomplete inflow of tagged spins.

In Fig. 7, curve fitting on the experimental signals plotted in Fig. 8 are presented. The initial three data points were excluded from the fitting to avoid the influence from incomplete inflow. Corresponding to the four pumping rates [45, 90, 135, 180] cc∕min, the estimated flow velocities for the intracompartment and extracompartment are [5.00, 11.36, 17.90, 22.68] mm∕s and [0.13, 0.23, 0.47, 0.80] mm∕s, respectively. Therefore, the averaged flow velocities are [1.59, 3.57, 5.69, 7.36] mm∕s.

Figure 7.

Curve fittings at four pumping rates [45, 90, 135, 180] cc∕min from two-compartment fitting. The resulting averaged velocities are [1.59, 3.57, 5.69, 7.36] mm∕s, respectively. The calculated correlation coefficient between the data and the fitting does decrease as the flow rates decrease.

Figure 8.

Representative coronal single-slice images acquired at [500, 1000, 1500, 2000, 2500, 3000, 5000] ms after the ASL magnetization inversion at a pumping rate of 180 cc∕min. Three rows correspond to tag (upper row), control (middle row), and difference (lower row) images. Within each image, coronal views of a Siemens water phantom (largest area), the hemodialyzer (arrow head), and the thin tube (arrow) are depicted. The progression of the front edge of fluid in hemodialyzer as TI increases (dashed line) provides a way to estimate the flow velocity, as presented by the dotted line.

To validate the results, images from a coronal slice of the hemodialyzer and static water phantom acquired at TI=[500, 1000, 1500, 2000, 2500, 3000, 5000] ms are shown in Fig. 8. Tag, control, and difference images are represented in the top, middle, and bottom rows, respectively. Within each image, the largest area corresponds to the coronal view of the static water phantom; the coronal views of the hemodialyzer and thin tube are located to the left and right of the static water phantom, respectively. A linear curve fitting of the progression of the front edge of fluid in the hemodialyzer as a function of TI provides a way to estimate the flow velocity.

The calculated values using the two methods: Transverse slice with Bloch-equation-based modeling and coronal slice with leading edge velocity modeling are listed in Table 1. A matched estimation on averaged velocities at four flow rates is found between the two methods. The greater deviation in matches at comparatively lower flow rates could be caused by the invalid assumption of plug flow in the hemodialyzer and the saturation of LL readouts.

Table 1.

Estimated flow velocity at four pumping rates [45, 90, 135, 180] cc∕min from two-compartment fitting using Bloch equation and leading edge velocity modeling. (Unit: mm∕s).

| Flow rate (cc∕min) | Intrafiber velocity | Extrafiber velocity | Fitting correlation coefficient | Average velocity | Leading edge velocity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45 | 5.00 | 0.13 | 0.863 | 1.59 | 1.3 |

| 90 | 11.36 | 0.23 | 0.834 | 3.57 | 1.7 |

| 135 | 17.90 | 0.47 | 0.990 | 5.69 | 5.0 |

| 180 | 22.68 | 0.80 | 0.998 | 7.36 | 7.5 |

In vivo imaging

Flow-sensitive images at one slice location acquired at TI of [700, 1000, 1300, 1600, 1900, 2200] ms are shown in Fig. 9. The wash-out of bolus is visible as TI increases. The large vein located at the bottom (circle) appears bright because the venous blood is labeled in IDOL tagging schemes.

Figure 9.

Flow-sensitive images acquired at TI of [700, 1000, 1300, 1600, 1900, 2200] ms. Bolus wash-out is visible as TI increases. The superior sagittal sinus located at the bottom (circle) appears bright because the venous blood is labeled in IDOL tagging schemes.

The fitted velocity mapping is shown in Fig. 10. A higher velocity is found in the superior sagittal sinus (SS) and slower velocities can be seen in gray matters. The flow mapping in Fig. 10 is scaled to the range of 0–5 to emphasize the signal at lower flow rates. The ROI-based flow rates estimation of gray matter, white matter, and sagittal sinus are 2.04, 0.89, and 22.09 mm∕s, respectively. The flow velocity in the SS is lower than the velocity reported by others.27 This is because IDOL preparation was used where both artery and venous blood were tagged. The accuracy of flow quantification in the veins drops due to the fact that the tagged blood passing through the imaging slice has time to enter the SS and pass again through the imaging slice during the ASL measurements. The signal from this twice-imaged blood is saturated and results in an error in the flow measurement.

Figure 10.

Brain velocity mapping (unit: mm∕s). A high velocity is found in the superior sagittal sinus and slower velocities can be seen in gray matter.

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we have presented the theory, as well as simulation and experimental verification, of a quantitative method to measure through-slice flow velocity using multiple TFL image readouts after IDOL preparation of a single slice. By using linear k-space ordering in the TFL images, the image intensities are a function of the local flow dynamics coupled with the IDOL tagging or control magnetization preparation. Through-plane flow assessment is achieved through Bloch equation modeling. Fitting the signal intensities in these multiple images provides an intrinsic decrease in measurement noise.

Computer simulations based on the Bloch equations, designed to model the situation of unidirectional flow in a hemodialyzer, demonstrated that the ASL signals are sequence parameter-dependent. The characteristic of the sequences and parameters were incorporated in the quantification modeling. Flow experiments were performed with the hemodialyzer and consistently matched values were found between the simulation and the hemodialyzer experiments.

The hemodialyzer and human brain MR images acquired using the proposed novel TFL-based imaging pulse sequence suggest that our technique could yield fairly accurate through-plane fluid flow estimation. Due to the two-compartment flow distribution in the hemodialyzer, phase contrast (PC) flow velocity measurement was not considered to be a feasible flow quantification technique in our study scenario. It is therefore not likely that PC flow measurements would be accurate, but would instead be biased by partial volume artifacts.

Certain assumptions and limitations apply to the quantification process involved in this study. Only the flow passing into and out of the imaged slice could provide measurable signal. Thus, for the case where flowing magnetization remains in the imaging slice, the method could possibly introduce errors by underestimating the flow. In addition, the net fluid passing through the thin slice in the hemodialyzer is assumed to be plug flow instead of laminar flow. This could explain the imperfect match between the two methods at slower flow rates of 45 and 90 cc∕min as listed in Table 1. Other potential error sources include deviations between the desired and actual flip angle, imperfections at the edges of the inversion pulses, and the general variation in the tag and control signals during image acquisition.

Although only single-slice imaging was used in this study, the fact that multiple acquisitions of the single slice are acquired during a single tagging (or control) makes the technique relatively efficient. This could easily be extended to multiple slices by serial acquisitions. At the same time, SNR can be improved by increasing the number of pairs of tag-control image sequences acquired. For example, the brain images shown were based on averages over four repetitions and more repetitions will lead to a higher SNR.

As implemented, this technique was designed to assess all flow passing through the slice, including vessels of all sizes down to capillary beds, unlike other techniques that use a preacquisition spoiler gradient pulse to suppress the flow signal from large vessels. By including all types of flow through the slice, the perfusion value obtained with this technique should match the perfusion term used in the Pennes’ BHTE. It is possible that thermal therapy techniques, such as MRgHIFU, could use measurements from this newly developed imaging technique in thermal modeling based on the Pennes’ equation. Since the goal is to estimate the Pennes’ perfusion term which depends on what carries heat outside the heated volume, the flow assessment on the feeding arteries and veins are desirable in this scenario. This method is independent of MR thermometry, decoupling the blood flow measurement from the MR temperature maps, allowing the perfusion changes to be monitored throughout the thermal therapy session. Currently, we are only showing blood flow in brain. The existence of the blood brain barrier makes the blood transfer time between the vasculature and the tissue longer. In other words, the flow could be captured before the tagged spins in the tissue become saturated by the excitation pulse trains. This application might become limited when extending to flow assessment in other tissues, e.g., kidney, liver, etc.

Further investigation including more subjects is necessary. The tradeoff between the image acquisition time and the accuracy of flow rate quantification needs to be optimized such that the scan could be interleaved in an actual MRgHIFU study. When dealing with flow quantification and modeling, the distribution of static and flowing spins within each voxel and how flow-sensitive signal changes as velocity varies are two important aspects that need to be addressed. In this work, velocity dependence of flow signal is obtained with linear phase encoding ordering. In the future, by modifying the timing of the acquisition of k-space center to be centric ordering, the blood flow distribution of perfusion signal can be obtained.

CONCLUSIONS

Multiple-image readout after a single ASL preparation, along with the linear acquisition ordering in the phase encoding direction in TFL imaging, enables the estimation of through-plane flow. The experiments provide evidence that the proposed pulse sequence design is able to measure the average velocity of fluid flowing through the image plane. Accuracy is decreased for venous blood that passes through and returns to the imaging slice during the time between tagging and signal readout. This measurement provides an estimate of total fluid flow when the voxel fraction of static magnetization is known.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by NIH Grant No. CA134599, The Ben B. and Iris M. Margolis Foundation, Siemens Medical Solutions, and The Focused Ultrasound Surgery Foundation. In addition, the authors would like to acknowledge Allison Payne, Glen Morrell, Bob Roemer, Douglas Christensen, Henry Buswell, Melody Johnson, Sathya Vijayakumar, and the HIFU group for the helpful discussions.

References

- Williams D. S. et al. , “Magnetic resonance imaging of perfusion using spin inversion of arterial water,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89(1), 212–216 (1992). 10.1073/pnas.89.1.212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song C. W., Rhee J. G., and Levitt S. H., “Blood flow in normal tissues and tumors during hyperthermia,” J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 64(1), 119–124 (1980). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F. et al. , “Tumor vessel destruction resulting from high-intensity focused ultrasound in patients with solid malignancies,” Ultrasound Med. Biol. 28(4), 535–542 (2002). 10.1016/S0301-5629(01)00515-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detre J. A. et al. , “Perfusion imaging,” Magn. Reson. Med. 23(1), 37–45 (1992). 10.1002/mrm.1910230106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton R. B. et al. , “A general kinetic model for quantitative perfusion imaging with arterial spin labeling,” Magn. Reson. Med. 40(3), 383–396 (1998). 10.1002/mrm.1910400308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelman R. R. and Chen Q., “EPISTAR MRI: Multislice mapping of cerebral blood flow,” Magn. Reson. Med. 40(6), 800–805 (1998). 10.1002/mrm.1910400603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelman R. R. et al. , “Qualitative mapping of cerebral blood flow and functional localization with echo-planar MR imaging and signal targeting with alternating radio frequency,” Radiology 192(2), 513–520 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golay X. et al. , “Transfer insensitive labeling technique (TILT): Application to multislice functional perfusion imaging,” J. Magn. Reson Imaging 9(3), 454–461 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong E. C., Buxton R. B., and Frank L. R., “Quantitative imaging of perfusion using a single subtraction (QUIPSS and QUIPSS II),” Magn. Reson. Med. 39(5), 702–708 (1998). 10.1002/mrm.1910390506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. G., “Quantification of relative cerebral blood flow change by flow-sensitive alternating inversion recovery (FAIR) technique: Application to functional mapping,” Magn. Reson. Med. 34(3), 293–301 (1995). 10.1002/mrm.1910340303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helpern J. A. et al. , “Perfusion imaging by un-inverted flow-sensitive alternating inversion recovery (UNFAIR),” Magn. Reson. Imaging 15(2), 135–139 (1997). 10.1016/S0730-725X(96)00353-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahng G. H., Weiner M. W., and Schuff N., “Improved arterial spin labeling method: Applications for measurements of cerebral blood flow in human brain at high magnetic field MRI,” Med. Phys. 34(11), 4519–4525 (2007). 10.1118/1.2795675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günther M., Bock M., and Schad L. R., “Arterial spin labeling in combination with a look-locker sampling strategy: Inflow turbo-sampling EPI-FAIR (ITS-FAIR),” Magn. Reson. Med. 46(5), 974–984 (2001). 10.1002/mrm.1284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen E. T., Lim T., and Golay X., “Model-free arterial spin labeling quantification approach for perfusion MRI,” Magn. Reson. Med. 55(2), 219–232 (2006). 10.1002/mrm.20784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki M. and Lee V. S., “Nonenhanced MR angiography,” Radiology 248(1), 20–43 (2008). 10.1148/radiol.2481071497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pell G. S. et al. , “TurboFLASH FAIR imaging with optimized inversion and imaging profiles,” Magn. Reson. Med. 51(1), 46–54 (2004). 10.1002/mrm.10674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad P. V. et al. , “Noninvasive comprehensive characterization of renal artery stenosis by combination of STAR angiography and EPISTAR perfusion imaging,” Magn. Reson. Med. 38(5), 776–787 (1997). 10.1002/mrm.1910380514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu D. C. and Buonocore M. H., “Breast tissue differentiation using arterial spin tagging,” Magn. Reson. Med. 50(5), 966–975 (2003). 10.1002/mrm.10616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çavuşoğlu M. et al. , “Comparison of pulsed arterial spin labeling encoding schemes and absolute perfusion quantification,” Magn. Reson. Imaging 27(8), 1039–1045 (2009). 10.1016/j.mri.2009.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbier E. L. et al. , “Perfusion imaging using dynamic arterial spin labeling (DASL),” Magn. Reson. Med. 45(6), 1021–1029 (2001). 10.1002/mrm.1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeder S. B. et al. , “Quantitative cardiac perfusion: A noninvasive spin-labeling method that exploits coronary vessel geometry,” Radiology 200(1), 177–184 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai V. M. et al. , “Detection of regional pulmonary perfusion deficit of the occluded lung using arterial spin labeling in magnetic resonance imaging,” J. Magn. Reson Imaging 11(2), 97–102 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts D. A. et al. , “Renal perfusion in humans: MR imaging with spin tagging of arterial water,” Radiology 196(1), 281–286 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi T. et al. , “Quantitative perfusion imaging with pulsed arterial spin labeling: A phantom study,” Magn. Reson. Med. Sci. 6(2), 91–97 (2007). 10.2463/mrms.6.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki M.et al. , “Non-enhanced 3D Breast MRA using FBI and time-SLIP,” presented at the Proceedings of the 17th ISMRM, Honolulu, HI, 18–24 April 2009.

- Brookes M. J. et al. , “Noninvasive measurement of arterial cerebral blood volume using look-locker EPI and arterial spin labeling,” Magn. Reson. Med. 58, 41–54 (2007). 10.1002/mrm.21199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattle H. et al. , “Flow quantification in the superior sagittal sinus using magnetic resonance,” Neurology 40(5), 813–815 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]