Abstract

Given the growing appreciation of serious health sequelae from widespread Trichomonas vaginalis infection, new tools are needed to study the parasite's genetic diversity. To this end we have identified and characterized a panel of 21 microsatellites and six single-copy genes from the T. vaginalis genome, using seven laboratory strains of diverse origin. We have (1) adapted our microsatellite typing method to incorporate affordable fluorescent labeling, (2) determined that the microsatellite loci remain stable in parasites continuously cultured up to 17 months, and (3) evaluated microsatellite marker coverage of the six chromosomes that comprise the T. vaginalis genome using fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH). We have used the markers to show that T. vaginalis is a genetically diverse parasite in a population of commonly used laboratory strains. In addition, we have used phylogenetic methods to infer evolutionary relationships from our markers in order to validate their utility in future population analyses. Our panel is the first series of robust polymorphic genetic markers for T. vaginalis that can be used to classify and monitor lab strains, as well as provide a means to measure the genetic diversity and population structure of extant and future T. vaginalis isolates.

Keywords: Population genetics, Trichomonas vaginalis, sexually transmitted infection, microsatellite, FISH, genetic markers

1. Introduction

Trichomoniasis, caused by the parasitic protist Trichomonas vaginalis, is the most prevalent non-viral sexually transmitted infection (STI) worldwide, with an estimated 174 million new cases occurring each year. Approximately five million of these infections occur within the United States [1], and 154 million occur in resource-limited settings [2]. As many as one-third of female infections and the majority of male infections are asymptomatic, causing trichomoniasis to often be considered a self-clearing female ‘nuisance’ disease [3]. However, trichomoniasis has been associated with a number of significant reproductive health sequelae, including pelvic inflammatory disease [4] and adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as premature rupture of membranes, preterm delivery, and low birth-weight [5, 6]. Most importantly, it has been implicated in increasing sexual transmission of HIV up to two-fold [7, 8]. Yet, despite its high incidence and associations with serious disease, the significance of T. vaginalis continues to be underestimated.

In light of these findings, understanding the transmission dynamics, strain virulence, and pathology of T. vaginalis infection is critically important for protecting patients -- particularly female patients -- from serious disease and threats to reproductive health. However, very little is known about T. vaginalis genetic diversity or population structure. Antigenic characterization, isoenzyme analysis, repetitive sequence hybridization, restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP), random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD), pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, and sequence polymorphism in ribosomal RNA genes and intergenic regions have been used to type T. vaginalis isolates in an attempt to find correlations between genotypes and biologically relevant phenotypes or geographical distribution [9-16]. Instead of providing clarification, these studies have yielded discordant results for a number of different phenotypes including metronidazole resistance and geographical distribution [9, 10, 13, 14], the presence of a linear, double-stranded RNA virus known as TVV [10, 13], clinical manifestation of infection in patients [12, 13], and virulence [9, 10, 13].

Multilocus genotyping of bacterial and eukaryotic pathogens has been used successfully to describe population diversity, delimit species, identify genetic components of important clinical phenotypes, and track the spread of epidemics [17-19]. While RAPD and RFLP techniques from the pre-genomics era have produced significant amounts of low-cost multi-locus data with relative ease, microsatellite (MS) loci, also known as short tandem repeats, have been found to be superior tools for most applications [20, 21]. These genetic markers are tandemly repeated 2-6 bp DNA sequences that display length polymorphism due to changes in the number of repeat units, and are frequently multi-allelic at each locus. They are expressed co-dominantly and are abundant throughout eukaryotic genomes. Crucially, they are generally considered to be neutral alleles that have not evolved under selective pressure, making them an ideal tool for determining population history. Finally, because of their high diversity, sensitivity and multilocus nature, they also allow for improved accuracy in detection of mixed genotype infections [22]. MS markers have been an important means for studying population genetics of a number of eukaryotic parasites [17, 23-26], having been used to characterize population structure in Leishmania tropica [27], Trypanosoma cruzi [28], T. brucei gambiense [29], Plasmodium falciparum [23], P. vivax [30], and Toxoplasma gondii [26]; to construct a genetic map for Plasmodium falciparum locating regions involved in such phenotypes as drug resistance [31]; and to determine the origins and global dispersal of drug-resistant parasite strains [32].

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are another type of genetic marker useful in molecular population genetics. Like MS markers, they can be highly prevalent and widely distributed within genomes; in contrast to MS, these markers are usually bi-allelic due to low mutation rates, which reduce the risk of homoplasy and simplify mutation models. These characteristics make them especially suited for certain analyses, such as the inference of phylogenies [33], particularly when they are localized within single-copy genes (SCG), although careful selection of SCG SNP markers is important to prevent gene-specific evolutionary history being mistaken for population evolutionary history. This danger persists despite the development of sophisticated statistical methods that are robust to a number of confounding influences on phylogenetic analyses [34]. Therefore, MS and SCG markers must be validated before they can be adopted as molecular tools for understanding the diversity and population structure of the parasite under study.

A genome sequence is an ideal resource for anyone intending to mine genetic loci for use as markers in population genetic studies, especially of an organism refractory to classical genetics. The draft T. vaginalis genome, published in 2007 [35], is a ∼160 MB assembly with a core set of ∼60,000 protein-coding genes [35]. Even at 7.2× coverage, the assembly remains highly fragmented with ∼74,000 contigs representing the parasite's six chromosomes. The poor quality of the assembly is due to such complicating factors as an apparently rapid, massive expansion of gene families, and the highly repetitive nature (>65%) of the genome, which rendered in silico genome assembly challenging [35]. However, this super-abundance of repeats suggests a genomic plenitude of MSs that can be exploited, although a comparative lack of single copy genes.

Here we report the identification and characterization of 86 microsatellite markers and 21 single-copy genes from the genome of T. vaginalis, from which a panel of 27 polymorphic genetic markers (21 MS markers and 6 SCG markers) were developed using seven common laboratory strains of diverse geographical origin, and six sub-strains. We have adapted our MS typing method to incorporate a simple and affordable fluorescent labeling protocol, thereby drastically reducing the cost of genotyping and making the technique readily available to members of the research community. To validate the usefulness of the markers, we have measured the stability and distribution of the MS, and used various methods of phylogenetic and minimum-spanning network analysis to compare the evolutionary relationships inferred by our panel of markers. Ours study represents the first to develop a robust series of polymorphic genetic markers for the T. vaginalis parasite that can be used to classify and monitor lab strains, as well as provide a means to measure the genetic diversity and population structure of T. vaginalis field isolates.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Parasite strains and DNA extraction

A list of the seven geographically widespread T. vaginalis laboratory strains used in this study is shown in Table 1. Two strains, BRIS/92/HEPU/B7268 and BRIS/92/HEPU/F1623 (abbreviated as B7268 and F1623, respectively) were cultured under drug selection for a minimum of 255 days and 530 days, respectively, and parasites were sampled at various time points during their continuous culture. DNA extraction for all strains was performed using modification of a published protocol [36]. Approximately 1.5 × 108 cells from late log phase cultures were harvested at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes at room temperature. The cell pellet was resuspended in 0.1× UNSET lysis buffer (8 M urea, 2% sarkosyl, 0.15 M NaCl, 0.001 M EDTA, 0.1 M Tris HCl pH 7.5), and the lysate immediately extracted twice with an equal volume of phenol:chlorophorm:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and once with an equal volume of chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (24:1). Nucleic acids were precipitated with 0.6 volumes of ice-cold isopropanol for 30 min at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. Following centrifugation at 12000 rpm for 40 min, the pellet was rinsed three times with 1 ml ice-cold 70% ethanol, dried at room temperature and resuspended in 50 μl low TE buffer, pH 8 (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) containing 5 μg/ml RNase A.

Table 1.

Seven Trichomonas vaginalis laboratory strains and six sub-strains used in this study. Several of the commonly used strains are available through the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Six sub-strains isolated during the course of long periods of continuous culture are also shown, with the day of isolation indicated (Day X).

| Identifier | Origin | Year | Availability | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B7RC2 | North Carolina, USA | 1986 | ATCC #50167 | [57] |

| C1:NIH | Maryland, USA | 1956 | ATCC #30001 | [58, 59] |

| T1 | Taipei, Taiwan | 1993 | Available from J. Carlton | [60] |

| G3 | Kent, UK | 1973 | ATCC #PRA-98 | [61-63] |

| CI6 | Puerto Rico | 1980's | BioMed Diagnostics, Inc. | Unpublished |

| BRIS/92/HEPU/F1623 (Day 0) | Brisbane, Australia | 1992 | Available from J. Carlton | [64, 65] |

| BRIS/92/HEPU/F1623-Met (Day 350) | Brisbane, Australia | 1992 | Available from J. Carlton | [64, 65] |

| BRIS/92/HEPU/F1623-Met (Day 440) | Brisbane, Australia | 1992 | Available from J. Carlton | [64, 65] |

| BRIS/92/HEPU/F1623-Met (Day 530) | Brisbane, Australia | 1992 | Available from J. Carlton | [64, 65] |

| BRIS/92/HEPU/B7268 (Day 0) | Brisbane, Australia | 1992 | Available from J. Carlton | [65-67] |

| BRIS/92/HEPU/B7268-Met (Day >55) | Brisbane, Australia | 1992 | Available from J. Carlton | [65-67] |

| BRIS/92/HEPU/B7268-Met (Day >55) | Brisbane, Australia | 1992 | Available from J. Carlton | [65-67] |

| BRIS/92/HEPU/B7268-toy (Day >200) | Brisbane, Australia | 1992 | Available from J. Carlton | [65-67] |

2.2 Microsatellite marker identification, genotyping and stability

The T. vaginalis genome sequence was mined using version 1.1 of the genome database resource TrichDB (http://trichdb.org; see Ref. [37]). The genome was screened for microsatellites (MS) with di-, tri-, tetra-, penta-, and hexanucleotide repeats, using the default settings of SciRoKo [38] as follows: a fixed penalty of five; allowing no more than three simultaneous mismatches; requiring a minimum score of 15 and a minimum of three repeats. The MS were filtered to include only those smaller than 400 bp to ensure that products would fall within the size standard range during genotyping. Sequences from the regions 200 bp upstream and downstream of each MS were downloaded and used to design MS-flanking primers with Primer3Plus [39], using default parameters modified for 100-450 bp products. Primer sequences were searched against the complete T. vaginalis genome with Megablast [40] to ensure uniqueness. A 19 nt tag sequence 5′-GTCGTTTTACAACGTCGTG-3′ was added to the 5′ end of all forward primers, and the final primer set was commercially synthesized (Table S1).

All MS markers were amplified as follows: 25 μL PCR reactions contained 50 nM forward primer, 1 μM reverse primer, 1 μM of the primer 5′-GTCGTTTTACAACGTCGTG-3′ labeled with phoshoramidite conjugate HEX or 6-FAM at the 5′ end, 1× Mg-free PCR buffer (Promega, Madison, WI), 0.25 mM dNTPs (New England BioLabs Ipswich, MA), 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 0.02 U/μL GoTaqFlexi (Promega, Madison, WI). Thermocycler programs were optimized for each primer combination (Table S1). We tested two different cycling programs (Step and Standard) at temperatures ranging from 45°C to 60°C and for each locus selected the program that worked most consistently based on ABI 3130xl sequencer results described below. Controls included (1) amplification of all primer sets with commercially available human DNA, (2) DNA prepared from a T. vaginalis negative vaginal swab to verify primer specificity for the parasite, and (3) DNA-free PCR reactions. To determine the sensitivity of the genotyping to mixed infections, artificial mixtures of two strains with genotypes known to differ was evaluated at three loci (MS70, MS77, MS135) at 1:1, 2:1 and 3:1 concentrations. These concentrations allowed for the detection of multiple peaks in all cases (data not shown). PCR amplicons were run on an ABI 3130xl sequencer with GeneScan-500 LIZ size standard (ABI, Foster City, CA) for size determination.

2.3 Identification and sequencing of single-copy genes (SCG)

Single copy genes (SCGs) in the highly repetitive T. vaginalis genome were identified by an all-against-all BLASTP [41] comparison of protein sequences, excluding those annotated as hypothetical. Sequences with >60% sequence similarity were removed from further consideration. The remaining genes were filtered by size and those ≤ 3.5 kb retained. Genes were selected manually from this list by criteria indicating likely polymorphism, for example, if they were implicated in biologically relevant mechanisms such as virulence. In addition, genes coding for several proteins identified as being located on the parasite cell surface [35] were screened for suitability as polymorphic markers. Primers were designed using Primer3Plus [39] using default parameters and the final primer set commercially synthesized (Table S2). All genes were amplified as follows: 50 μL PCR reactions contained 1 μM forward primer, 1 μM reverse primer, 1× Mg-free PCR buffer (Promega, Madison, WI), 0.25 mM dNTPs (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA), 1.5-2 mM MgCl2, and 0.02 U/μL GoTaqFlexi (Promega, Madison, WI). Thermocycler programs (called 2 kb and 3.5kb) were optimized for each primer combination using gradient PCRs ranging from 45°C to 65°C (Table S2). Controls included DNA-free PCR reactions. PCR products were visualized on 1% agarose gels and those containing single amplicons were purified using Agencourt AMPure (Beckman Coulter Genomics, Danvers, MA). The band of interest in PCRs with multiple products were purified via gel isolation using Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-up System (Promega Madison, WI). Sequencing reactions were performed using BigDye Terminator v 3.1 (ABI, Foster City, CA) using forward primers, reverse primers, and internal sequencing primers when necessary. All genes were sequenced at ≥ 2× coverage. Sequencing reactions were cleaned using Agencourt CleanSEQ (Beckman Coulter Genomics, Danvers, MA) and analyzed on an ABI 3130xl sequencer. The new sequences from T. vaginalis lab strains were deposited in GenBank as indicated in Table S3.

2.4 Chromosome spreads and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH)

FISH was used to map T. vaginalis MS markers to their chromosomal positions. T. vaginalis cells were prepared using modifications to a published protocol [42]. Briefly, G3 parasites were grown to mid-log phase in Diamonds media with 10% horse serum, 1 mM Colchicine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) added to 30-50 ml of culture (∼1.5 × 106 cells/ml), incubated at 37°C for 6 h, and the cells harvested by centrifugation (all centrifugations were performed at 1000 × g for 5 minutes at 4°C). Cells were resuspended in 10 mL of 75 mM potassium chloride, allowed to swell for 5 minutes at 37°C, centrifuged, gently resuspended in 5 mL of fresh Carnoy fixative (ethanol:chloroform:glacial acetic acid, 6:3:1) at 4°C for 20 minutes, centrifuged again and finally left resuspended in ∼1-2 mL fresh Carnoy fixative 4°C over night. Approximately 20 μl of the cell suspension were dropped from a height of ∼100 cm onto grease-free microscopic slides and left to air-dry.

Primers to amplify 1.5-2.5 kb regions spanning each of the MS loci were designed with Primer3Plus [39] using default parameters and the final primer set commercially synthesized (Table S3). All genes were amplified as described for SCGs using either the Step or 2 kb thermocycler program. Amplicons were gel purified using the Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-up System (Promega Madison, WI), labeled with DIG-11-dUTP using the DIG DNA Labeling Kit (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) and cleaned by ethanol precipitation.

Freshly prepared T. vaginalis chromosome spreads were briefly placed in 50% acetic acid solution, dried at 37°C, incubated in 50 ug/ml pepsin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in 3mM acetate buffer with 0.01 M HCl, and washed with PBS pH 7.4 at room temperature for 5 min. The chromosomes were post-fixed with fresh 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min, and incubated in 1% H2O2 in PBS for 30 min (all at at room temperature). Following dehydration in 3 min washes of increasing concentrations of methanol (70%, 90%, and 100%) and subsequent drying, the chromosomes were denatured in 70% formamide in 2× SSC for 5 min at 75°C under a cover slip and then immediately dehydrated in a methanol series as described above. A total of 2 μl of each probe (∼20 ng) was denatured in 50 μl of 50% deionized formamide (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in 2× SSC at 90°C for 5 min and submerged in ice for 3 min. The probe mixture was applied to the chromosome slides, a coverslip overlaid and sealed with rubber cement, and hybridization was left to proceed overnight in a humid chamber at 37°C.

High stringency washes were performed at 42°C in 3 changes of 50% formamide (Fluka Buchs, SUI) in 2× SSC for 5 min each, 3×5 min washes in 2× SSC, and a 5 min wash in TNT wash buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween20, pH 7.5), both at room temperature. At room temperature, samples were blocked for 30 min with TNB blocking buffer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA), and then incubated for 60 min in a humid chamber with anti-digoxigenin antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) diluted 1:1000 in TNB. Slides were washed 3 times for 5 minutes in TNT wash buffer at room temperature. The TSA-Plus TMR System (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) was used for tyramide signal amplification according to the manufacturers instructions. Slides were counterstained with DAPI in Vectashield mounting medium (VectorLabs, Burlingame, CA).

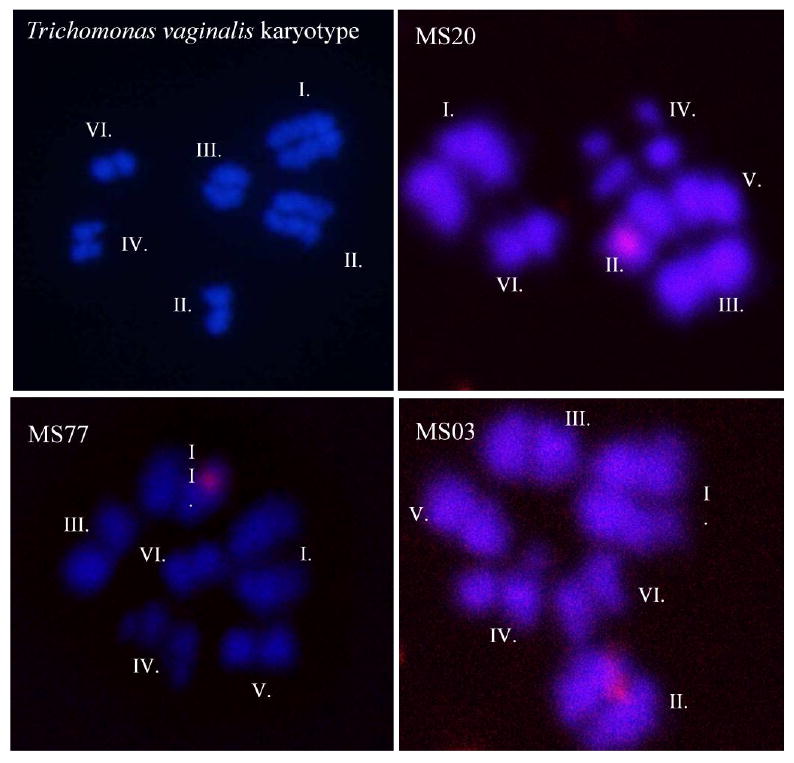

Slides were visualized using a Leica TCS SP2 AOBS confocal microscope at 63×, and images were merged using LCS Lite v. 2.5 (Leica Microsystems Heidelberg GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Chromosomes were identified by their morphological characteristics [42] (see Figure 1 legend), and chromosome assignment was performed twice, first with a locus-identifying label, and then a second time in randomized order with labels removed (i.e blinded).

Figure 1.

Representative images of metaphase-arrested chromosome spreads hybridized with probes specific to microsatellite loci. Top left panel: Representative image showing the T. vaginalis karyotype and chromosome numbering according to a distinct set of karyometrical data [35]; top right panel: MS20 localized to chromosome II; bottom left panel: MS77 localized to chromosome II; and bottom right panel MS03 localized to chromosome II. The six T. vaginalis chromosomes are morphologically distinct as follows: Chromosome I is the longest and is a subtelocentric/submetacentric type; Chromsome II is acrocentric; Chromosome III is metacentric; and Chromosome IV is metacentric/submetacentric; Chromosome V is subtelocentric/acrocentric, although the short arm is not always visible; and Chromosome VI is the shortest and acrocentric.

2.5 Population genetic and evolutionary analyses

GeneMapper 4.0 (ABI, Foster City, CA) was used to score MS allele sizes. All calls were manually edited to discard data from poorly amplified reactions and to ensure that proper allele calls were assigned. Strains were classified as mixtures of two or more genotypes if multiple peaks appeared at two or more loci in duplicate reactions. HE (expected heterozygosity) was calculated using the formula HE = [n/(n-1)][1 - Σni=1 p2] where p is the frequency of the ith allele and n is the number of alleles sampled and confirmed with Arlequin3.11 [43]. A phylogeny using MS markers was inferred using POPTREE2 [44], a program that constructs phylogenetic trees from allele frequency data. A neighbor-joining (NJ) tree was constructed using DA[45] distance as a measure of genetic difference between individuals. Support values for the tree were obtained by bootstrapping 1000 replicates. A minimum spanning network was inferred using Network 4.516 (Fluxus Technology Ltd. 2009) [46], software developed to reconstruct all possible least complex phylogenetic trees using a range of data types.

For SNPs, SCG sequence data was aligned to the reference sequence published in TrichDB and the alignments manually edited using Sequencher 4.8 (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI). Called SNPs were manually verified and included any single nucleotide change that occurred in any single strain. We used ModelGenerator v. 0.85 [47] to identify appropriate nucleotide substitution models for inference of trees for the six most polymorphic gene sequences: a set of three surface protein coding genes TVAG 400860 (GP63a), TVAG 216430 (GP63b), and TVAG 303420 (LLF4), and a set of three housekeeping genes TVAG 005070 (PMS1), TVAG 302400 (Mlh1a), TVAG 021420 (coronin, CRN), with the number of gamma categories set at ten. PhyML [48] as part of SeaView v. 4.2.4 [49] was used to infer maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenies reconstructed by applying simultaneous NNI (Nearest Neighbour Interchange) and SPR (Subtree Pruning and Regrafting) moves on five independent random starting trees. Substitution rate categories were set at ten and transition/transversion (Ts/Tv) ratios, invariable sites and across-site rate variation were selected as indicated by ModelGenerator. Support values for the tree were obtained by bootstrapping 1000 replicates. Each gene was initially run independently and two manually concatenated DNA sequence data sets were generated based on their topology. The surface protein sequences were analyzed using Tamura and Nei's 1993 nucleotide substitution model [50] with a Ts/Tv ratio of 2.4, twelve rate categories, gamma distribution parameter alpha = 0.04, and the proportion of invariable sites being set at 0.83, while the housekeeping gene sequences were analyzed with Hasegawa, Kishino and Yano's 1985 nucleotide substitution model [51] with a Ts/Tv ratio of 1.91, four rate categories, and the proportion of invariable sites set at 0.97.

3. Results

3.1 Microsatellite identification and development of a simple genotyping method

We screened the Trichomonas vaginalis genome sequence for microsatellites (MS) as an initial step towards developing a panel of markers for genetic diversity studies of the parasite. In total, 4,630 MSs were identified with an average length of 30.50 nt ± 1.07 SE, with trinucleotide and pentanucleotide repeats being the most abundant (37.7% and 25.6%, respectively), followed by tetranuclotide (14.9%), hexanuclotide (12.3%) and dinucleotide (9.5%) repeats. After further filtering to exclude MSs present on the same scaffold, we designed unique primer pairs to 86 MSs for testing (Table S1). Of these 86 MS loci, a total of 21 were found to amplify reliably under our optimizing conditions and are described below in detail.

We also adapted previously published methods to develop a simple, reliable and affordable high-throughput MS genotyping protocol for T. vaginalis population genetic studies. First, we adapted a ‘tagged primer’ technique [52, 53] by adding a 19 nt tag to the 5′ end of each forward primer, designed to be recognized by a fluorescently tagged universal primer. Primers were added in a 1:40:40 ratio (locus specific forward primer: locus specific reverse primer: tagged universal primer) to perform semi-nested PCRs in which priming was done first with locus-specific reactions, which were then used as a template for reactions with the labeled primer. Using one fluorescently-tagged universal primer to label all 21 loci greatly reduces genotyping costs. We tested two amplification programs [54] (Table S2) at a range of annealing temperatures, and validated the amplicons by sequencing to determine the most reliable program for each locus. For the latter step HEX-labeled and 6-FAM labeled reactions were multiplexed on the ABI 3130xl, further reducing genotyping costs and increasing the efficiency of the semi-automated, high-throughput methods described here.

3.2 T. vaginalis microsatellites are stable over many generations

To determine if the microsatellite loci characterized in this study are stable over long periods (e.g., during continuous culture of the parasite), we genotyped two T. vaginalis strains that had been maintained in culture for many months. T. vaginalis strain F1623 was maintained under metronidazole selection for a minimum of 530 days, and strain B7268 was maintained under metronidazole selection for a minimum of 55 days and toyocamycin selection for a minimum of 200 days (Table 1). We genotyped each strain in duplicate with all 21 MS markers at four separate time points: Day 0, two Day 55 time points from independent cultures, and Day 255 for strain B7268; and at Day 0, Day 350, Day 440, and Day 530 for strain F1623. No changes were observed at any of the four time points evaluated (data not shown), indicating that the MS loci are stable for at least 16 months under highly selective conditions. For all further analyses the data for these different time points were collapsed and considered as a single isolate.

3.3 Assignment of MS markers to T. vaginalis chromosomes

In order to ensure that our polymorphic MS loci were distributed throughout the T. vaginalis genome and not localized to one or two or regions of chromosomes, we used fluorescent in situ chromosome hybridization (FISH) to map MS loci to the six chromosomes that comprise the T. vaginalis genome. T. vaginalis chromosome spreads were hybridized with DIG-labeled locus-specific probes designed to be 1.5-2.5 kb in length and to span the entire MS locus, and hybridized probes were visualized using a tyramide signal amplification system. The chromosomes were identified by their morphological characteristics after two independent analyses of confocal images (Figure 1). Although successful signal detection from hybridizations of the probes were infrequent, most likely due to the single-copy nature of the loci, 13 of the 21 MS were successfully mapped to single chromosomes, and the location of a 14th marker (MS06) could be narrowed down to one of two chromosomes (Table 2). The 14 mapped MS markers are distributed among four of the six chromosomes, with an average of approximately three markers per chromosome, ranging from two markers on chromosomes I and IV, to five markers on chromosome II (Table 2). Chromosomes V and VI, the smallest of the six chromosomes, were not represented by the mapped markers, although any of the remaining eight MS markers may be located on them.

Table 2.

Characteristics of 21 T. vaginalis MS loci characterized in this study.

| Locus | Motif | Chromosome | Scaffold | Scaffold Size | G3 lengthb | Alleles | HE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS01 | GAATAA | I** | DS113177 | 584,929 bp | 170 | 3 | 0.52 |

| MS03 | AAAATA | II* | DS113181 | 437,572 bp | 253 | 1 | 0 |

| MS04 | CAA | ND | DS113183 | 431,961 bp | 250 | 3 | 0.67 |

| MS06 | TTC | III or IV* | DS113274 | 170,984 bp | 406 | 6 | 0.95 |

| MS07 | ATTAAT | II* | DS113206 | 244,377 bp | 401 | 3 | 0.76 |

| MS08a | TTC | III* | DS113227 | 207,319 bp | 270 | 3 | 0.67 |

| MS09a | AGAA | IV** | DS113295 | 155,794 bp | 423 | 2 | 0.29 |

| MS10 | AAAT | IV* | DS113349 | 128,477 bp | 421 | 4 | 0.87 |

| MS17 | TTTTA | III*** | DS113178 | 503,923 bp | 206 | 4 | 0.9 |

| MS20a | TGT | III** | DS113200 | 279,084 bp | 432 | 2 | 0.29 |

| MS38a | CTT | III* | DS113502 | 91,738 bp | 266 | 2 | 0.29 |

| MS44 | AT | II** | DS113642 | 69,902 bp | 247 | 4 | 0.81 |

| MS70 | TA | ND | DS114241 | 24,950 bp | 252 | 4 | 0.86 |

| MS77 | GA | II*** | DS114317 | 22,118 bp | 227 | 3 | 0.67 |

| MS94 | AT | ND | DS113199 | 279,741 bp | 209 | 2 | 0.57 |

| MS100 | TG | I* | DS113212 | 227,203 bp | 194 | 2 | 0.57 |

| MS129 | ATT | ND | DS113270 | 172,859 bp | 193 | 5 | 0.86 |

| MS135 | TA | ND | DS113807 | 53,461 bp | 248 | 4 | 0.81 |

| MS153 | AT | ND | DS113342 | 132,270 bp | 242 | 4 | 0.81 |

| MS168 | TG | ND | DS113392 | 115,942 bp | 183 | 4 | 0.81 |

| MS184a | TTG | II** | DS113453 | 99,852 bp | 254 | 5 | 0.86 |

| Average | 211,165 bp | 268.7 | 3.33 | 0.66 |

Indicates microsatellite is located within an annotated gene;

The actual size of MS amplified from reference strain G3 are all within 1- 4 bp of the expected size as predicted by in silico analysis of the G3 genome assembly, with the exception of with the 19 bp tag sequence added to all loci and two markers, MS04 and MS09, which have a 6 bp and 13 bp difference, respectively;

localization inferred from one replicate;

localization inferred from two replicates;

localization inferred from ≥ 3 replicates; ND not determined.

3.4 T. vaginalis MS markers from common laboratory strains are highly polymorphic

We used the 21 MS markers identified above to genotype seven lab strains of T. vaginalis. Several of the strains are maintained at the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and are commonly used by T. vaginalis labs around the world. MS loci ranged from two to six nucleotides in length, and each locus had from 1 to 6 alleles (Table 1), the average being 3.33 alleles per locus. We used the formula HE = [n/(n-1)][1 - Σni=1 p2] where p is the frequency of the ith allele and n is the number of alleles sampled, to determine heterozygosity of each locus, and we verified this value with Arlequin 3.11 [43]. This value varied by locus, ranging from 0 to 0.95, with the average HE determined to be 0.66 ± 0.06. One locus was found to be monomorphic in the lab isolates, but genotyping of additional clinical isolates (data not shown) revealed it to be polymorphic. None of the lab strains appeared to be mixtures of genotypes by our criteria, or in comparison to a simulated mixture of two lab strains that we used as a control (see Materials & Methods; data not shown). These results show that MSs in T. vaginalis are highly polymorphic and can be used as robust markers for genetic studies.

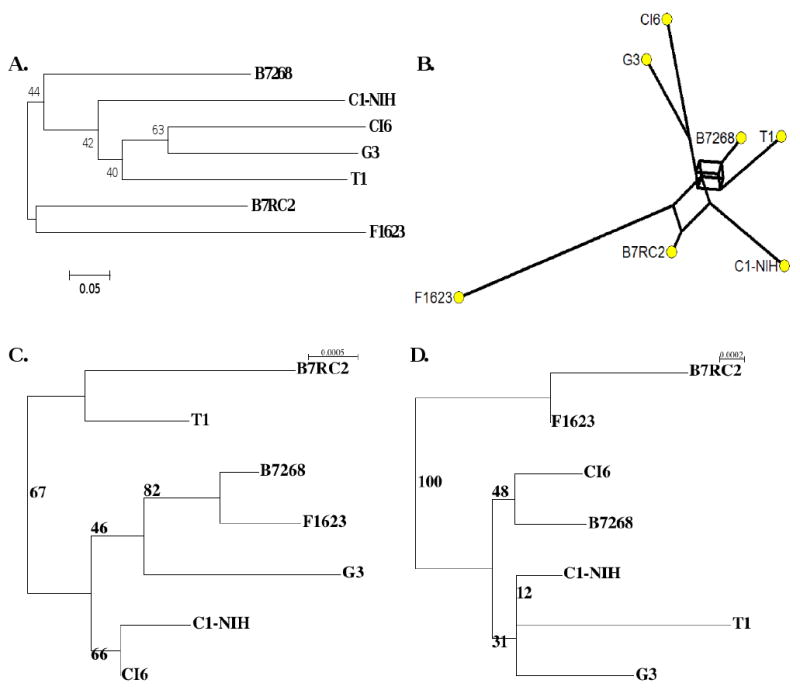

Phylogenetic analyses of the lab isolates using MS data inferred trees with low to moderate support (Figure 2a). The basic topology of the phylogeny correlates well with the topology of the minimum-spanning network inferred by Network (Figure 2b), supporting the ability of these markers to represent the evolutionary history of the strains. Topologies from both methods suggest a branch composed of B7RC2 and F1623 that is consistently delineated from the remaining five isolates. This separation also occurs in the phylogeny inferred from concatenated sequences of housekeeping genes (see below).

Figure 2.

(A) Neighbour Joining tree inferred from microsatellite data using DA distance. Numbers in the tree correspond to non-parametric bootstrap supports (1000 replicates). (B) Minimum-spanning network inferred from microsatellite data using reduced median setting. (C) Maximum Likelihood phylogeny inferred using concatenated surface protein gene sequences. The log-likelihood of the corresponding phylogenetic model is -5946.1 (D) Maximum Likelihood phylogeny inferred using concatenated housekeeping gene sequences. The log-likelihood of the corresponding phylogenetic model is -7963.0. For both ML phylogenies, the numbers in the trees correspond to non-parametric bootstrap supports (1000 replicates).

3.5 Single copy gene identification and polymorphism

Although MS markers are useful in characterizing genetic diversity due to their highly polymorphic nature, the high mutation rate associated with them can also be disadvantageous, leading to homoplasies that may confound true evolutionary histories. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), on the other hand, arise less frequently, are less subject to homoplasy, and with the advent of high-thoughput sequencing methods, are easier to genotype. Since SNPs located within single copy genes (SCGs) are most useful for inferring phylogenies, we mined the T. vaginalis genome for SCGs using a basic all-versus-all BLASTP of all non-hypothetical proteins, and identified 4,582 genes as suitable candidates. The list was then further reduced to 845 genes by removing all those with a shared annotated name, and then reduced further on the basis of size and function. A final experimental set of 21 loci included 18 genes identified through this screening process and three genes (GP63a, GP63b and LLF) included because their putative function as surface proteins suggested that they might be polymorphic. Amplification and sequencing of all 21 genes from seven of the laboratory strains identified a wealth of SNPs (Table 3). Polymorphism varied by locus, with some genes highly conserved and exhibiting no variation (TVAG_094560 and TVAG_309150) and others having up to 19 SNPs in ∼1.4 kb of sequence (TVAG_400860).

Table 3.

SNPs identified in 21 single copy genes sequenced in seven T. vaginalis strains. Genes underlined (GP63a, PMS1, Mlh1a, CRN, GP63b, LLF4) were used to generate phylogenetic trees shown in Figure 2.

| Gene ID | Gene name | No. SNPs | Sequence Length (bp) | Accession Nos. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TVAG_400860 | Clan MA, family M8, leishmanolysin-like metallopeptidase (GP63a) | 19 | 1425 | HM365121-26 XM_001324948 |

| TVAG_005070 | Mismatch repair MutL homolog (PMS1) | 13 | 1617 | HM365174-78 XM_001301638 DQ321767 |

| TVAG_302400 | Mismatch repair MutL homolog (MLH1A) | 13 | 2337 | HM365169-73 XM_00132034 1DQ321764 |

| TVAG_021420 | Coronin (CRN) | 7 | 1659 bp | HM365115-20 XM_001581132 |

| TVAG_364940 | Antigenic protein P1, putative (VSA) | 7a | 1055 bp | HM365203-08 XM_001304496 |

| TVAG_216430 | Clan MA, family M8, leishmanolysin-like metallopeptidase (GP63b) | 6 | 1638 bp | HM365127-32 XM_001317855 |

| TVAG_303420 | Vesicular mannose-binding lectin, putative (LLF4) | 5 | 1119 bp | HM365157-62 XM_001329311 |

| TVAG_291830 | Vesicular mannose-binding lectin, putative, PS (LLF1) | 4 | 1032 bp | HM365139-44 XM_001329418 |

| TVAG_086190 | Vesicular mannose-binding lectin, putative | 4 | 1095 bp | HM365151-56 XM_001310009 |

| TVAG_171780 | HIV-1 rev binding protein, putative | 4 | 750 bp | HM365133-38 XM_001315268 |

| TVAG_485880 | Clan CA, family C1, cathepsin L-like cysteine peptidase | 4 | 1233 bp | HM365109-14 XM_001321129 |

| TVAG_228710 | Clan CA, family C1, cathepsin L-like cysteine peptidase | 3 | 729 bp | HM365103-08 XM_001580544 |

| TVAG_291970 | Multidrug resistance pump, putative | 3 | 885 bp | HM365163-68 XM_001329432 |

| TVAG_184510 | Tubulin alpha chain, putative | 2 | 834 bp | HM365197-202 XM_001322737 |

| TVAG_459080 | Aspartic peptidase | 2 | 565 bp | HM365179-84 XM_001324024 |

| TVAG_414100 | Tropomyosin isoforms 1/2, putative | 2 | 879 bp | HM365191-96 XM_001321947 |

| TVAG_087140 | Arp2/3, putative | 2 | 801 bp | HM365091-96 XM_001318124 |

| TVAG_192620 | Actin depolymerizing factor, putative | 1 | 378 bp | HM365085-90 XM_001581222 |

| TVAG_166900 | Histone deacetylase complex subunit SAP18, putative | 1 | 294 bp | HM365185-90 XM_001582251 |

| TVAG_094560 | Clan CE, family C48, cysteine peptidase | 0 | 640 bp | HM365097-102 XM_001583217 |

| TVAG_309150 | Conserved hypothetical protein (with PF03388 Domain) | 0 | 1119 bp | HM365145-50 XM_001321414 |

All seven SNPs were found within a single isolate that also has a frame-shifting deletion.

We selected six of the most variable genes (GP63a, PMS1, Mlh1a, CRN, GP63b, and LLF4) representing housekeeping genes, potential virulence factors and drug targets, for phylogenetic analysis. (Although TVAG_364940 [VSA] was found to be more polymorphic than TVAG_216430 [GP63b] and TVAG_303420 [LLF4], the polymorphisms were restricted to a single isolate with a frame-shifting deletion, and so we excluded this gene.) After determining appropriate nucleotide model parameters, we used PhyML [48] to infer the phylogeny of each gene separately. The three surface protein genes (GP63a, GP63b, and LLF4) had similar topologies, as did the three housekeeping genes (PMS1, Mlh1a, and CRN), although these topologies differed between the two groups. Using the similarity between the topologies, we arranged the sequence data into two concatenated data sets, one composed of the three putative surface protein coding genes (GP63a, GP63b, and LLF4), and one composed of the three housekeeping genes (PMS1, Mlh1a, and CRN). The surface protein data set was composed of 4182 unambiguously aligned positions with 30 polymorphic sites, translating to 24 variable sites in the protein sequence, one of which has three amino acid variants, while the housekeeping data set was composed of 5619 unambiguously aligned positions, including 34 polymorphic positions, translating to 23 variable sites in the protein sequence. The two data sets were analyzed using Tamura and Nei's [50] and Hasegawa, Kishino and Yano's [51] nucleotide substitution models respectively. The two trees share little topology (Figure 2c, 2d), probably as a result of the different selective pressures and evolutionary forces the two sets of genes experience. The phylogeny inferred from the concatenated housekeeping sequence has better bootstrap support than that of the concatenated surface protein sequence; in addition, it more closely resembles the phylogenetic and minimum-spanning network topologies inferred from microsatellite data (Figure 2a,b,d), suggesting that the separation of B7RC2 and F1623 from the remaining strains is the best representation of their ancestral history under assumed neutral selection pressure. Including additional lab strains or isolates would likely clarify relationships between individual strains that are currently ambiguous.

Discussion

A draft of the first T. vaginalis genome sequence was published in 2007 [35], opening the way for development of new genetic tools to understand the biology of this neglected pathogen. Although Sanger sequencing coverage of the genome is high at ∼7.2×, the presence of hundreds of gene families and thousands of repetitive elements that show extreme similarity to each other (average pairwise difference ∼2.5%) hinder the generation of a more complete assembly of the genome [35]. As a result, identifying the single-copy genes and unique MS markers reported in this study has been a challenging and non-trivial exercise.

Here we have described a novel suite of 27 robust, reproducible, and inexpensive genetic markers for investigating the population genetics of T. vaginalis, including the first reported MS markers and a panel of diverse single copy genes. In addition, we have mapped the MS loci to individual chromosomes, verified their stability, and performed minimum-spanning network and phylogenetic analysis to validate their usefulness for inferring the evolutionary relationship of strains. We have similarly identified polymorphic single-copy genes and also demonstrated their use in phylogenetic studies.

Our results show that the 21 MS loci that we identified and successfully optimized for genotyping in seven laboratory strains and six sub-strains exhibit a high degree of diversity, and are distributed among at least four of the six chromosomes comprising the T. vaginalis genome. We have shown these markers to be stable in continuous culture over extended periods of time while under drug selection, suggesting that the mutation rate at these loci is slow enough to prevent extensive homoplasy, and supporting their usefulness as markers.

By identifying single copy genes coding for protein sequences lacking strong similarity to other protein sequences encoded by the genome, we have been able to eliminate complications arising from the use of paralogs (genes related by duplication within a genome), ensuring that phylogenies represent locus-specific evolutionary history and therefore better reflect the ancestral relationship of T. vaginalis isolates. We have also selected genes with diverse functions, including housekeeping genes and putative surface proteins, thereby representing the history of loci evolving under a range of selective pressures. Combining sequence data from these genes allows us to accurately represent the evolutionary history of the genome as whole, rather than of select loci. In addition, we have identified genes with sufficient polymorphism to distinguish between closely related strains, making these markers useful for intra-specific, population-level analyses.

The six genes that we have selected for phylogenetic analysis demonstrate different evolutionary relationships among the strains. The housekeeping gene phylogenies strongly support strains B7RC2 and F1623 (collected from Brisbane, Australia in 1992) being more closely related to each other than to the other isolates, a relationship that is maintained in phylogenies of the individual genes that make up the concatenated data set. This association is also found in ancestral relationships inferred from microsatellite data using two different methods of analysis. In contrast, the surface genes indicate a closer relationship between B7268 and F1623. This relationship is only apparent in the GP63a gene, as the other individual genes have low support values at all nodes (data not shown). This may indicate that the relationship of these genes is more influenced by selective pressure than common ancestry. Pressure for diversification of surface proteins to adapt to host immune responses and/or to be able to colonize a host may overshadow other aspects of their evolutionary history, making their ancestral relationship ambiguous in this small data set. Evaluating additional clinical samples may better explain the lack of overlap in tree topologies and provide a clearer picture of the forces driving the relationships between the genes of different isolates.

During our MS marker development, we employed a cost-saving method that utilized one universal tagged primer to label PCR amplicons of the MS loci [52, 53, 55], making the technique accessible to more researchers, particularly those in resource-limited settings. The availability of these reproducible markers will allow comparison and merging of data sets from different research projects, enabling a more comprehensive investigation of the population diversity of T. vaginalis through better representation of widespread geographical locations, population demographics, and overall parasite diversity.

As a result of this study and future parallel population-level diversity studies, those investigating T. vaginalis will be able to examine the extant population structure and diversity of the parasite to better select strains when studying specific biological functions. Similarly, this genotyping method will be invaluable for resolving conflicting experimental results by helping to standardize the influence of genetic background on variation in quantitative traits. Another powerful use of these markers will be to elucidate the role of meiosis in the T. vaginalis lifecycle [54] by providing a means to detect recombinants [56] and to utilize population genetic models to detect other evidence for or against recombination, such as linkage disequilibrium [23] or the detection of haplotypes in significantly excessive frequency [57].

T. vaginalis remains a ‘neglected’ pathogen in part due to an incomplete understanding of the role it has played in pathology and in facilitating co-infection and transmission of diseases that are of great public health concern (e.g., HIV/AIDS). As a result, there is a paucity of tools for elucidating its mechanisms of colonization, pathogenesis, and drug resistance. The development of this panel of genetic markers is a step towards rectifying this neglect and raising awareness of the complexity of the parasite's genetics, leading to better explanation of the wide range of severity of symptoms and manifestations of pathology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Shehre-Banoo Malik for assistance in phylogenetic analyses, Patrick Sutton for valuable input in the writing of the manuscript, and Ute Frevert for assistance with the microscopy. We would also like to recognize the Confocal Microscopy Facility of the Department of Medical Parasitology for the use of the Leica TCS SP2 AAOBS confocal microscope. M.C. was partially funded under a National Institutes of Health training grant T32AI007180-27. This study was funded by a National Institutes of Health award to J.M.C. under the Advancing Novel Science in Women's Health Research program announcement, grant number R21 AI083954-01.

Abbreviations

- He

expected heterozygosity

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- FISH

fluorescent in situ hybridization

- MS

microsatellite

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- SCG

single copy gene

Footnotes

Note: Nucleotide sequence data reported in this paper are available in the EMBL, GenBank and DDBJ databases under the accession numbers: HM365085 - HM365208, DQ321767, DQ321764, XM_001301638, XM_001304496, XM_001310009, XM_001315268, XM_001317855, XM_001318124, XM_001320341, XM_001321129, XM_001321414, XM_001321947, XM_001322737, XM_001324024, XM_001324948, XM_001329311, XM_001329418, XM_001329432, XM_001580544, XM_001581132, XM_001581222, XM_001582251, XM_001583217

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO/HIV_AIDS/2001.02. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. Global prevalence and incidence of selected curable sexually transmitted infections: overviews and estimates. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnston VJ, Mabey DC. Global epidemiology and control of Trichomonas vaginalis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2008;21(1):56–64. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3282f3d999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Der Pol B. Editorial Commentary: Trichomonas vaginalis Infection: The Most Prevalent Nonviral Sexually Transmitted Infection Receives the Least Public Health Attention. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(1):23–25. doi: 10.1086/509934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cherpes TL, et al. The associations between pelvic inflammatory disease, Trichomonas vaginalis infection, and positive herpes simplex virus type 2 serology. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(12):747–752. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000218869.52753.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moodley P, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis Is Associated with Pelvic Inflammatory Disease in Women Infected with Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(4):519–522. doi: 10.1086/338399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cotch MF, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis associated with low birth weight and preterm delivery. The Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. Sex Transm Dis. 1997;24(6):353–60. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199707000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McClelland RS, et al. Infection with Trichomonas vaginalis increases the risk of HIV-1 acquisition. J Infect Dis. 2007;195(5):698–702. doi: 10.1086/511278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guenthner PC, Secor WE, Dezzutti CS. Trichomonas vaginalis-Induced Epithelial Monolayer Disruption and Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 (HIV-1) Replication: Implications for the Sexual Transmission of HIV-1. Infect Immun. 2005;73(7):4155–4160. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.7.4155-4160.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vanacova S, et al. Characterization of Trichomonad Species and Strains by PCR Fingerprinting. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1997;44(6):545–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1997.tb05960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hampl V, et al. Concordance between genetic relatedness and phenotypic similarities of Trichomonas vaginalis strains. BMC Evol Biol. 2001;1:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mead JR, et al. Use of Trichomonas vaginalis Clinical Isolates to Evaluate Correlation of Gene Expression and Metronidazole Resistance. J Parasitol. 2006;92(1):196–199. doi: 10.1645/GE-616R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rojas L, Fraga J, Sariego I. Genetic variability between Trichomonas vaginalis isolates and correlation with clinical presentation. Infect Genet Evol. 2004;4(1):53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snipes LJ, et al. Molecular Epidemiology of Metronidazole Resistance in a Population of Trichomonas vaginalis Clinical Isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38(8):3004–3009. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.8.3004-3009.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stiles JK, et al. Molecular typing of Trichomonas vaginalis isolates by HSP70 restriction fragment length polymorphism. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;62(4):441–5. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.62.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Upcroft JA, et al. Genotyping Trichomonas vaginalis. Int J Parasitol. 2006;36(7):821–828. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crucitti T, et al. Molecular typing of the actin gene of Trichomonas vaginalis isolates by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14(9):844–852. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barker GC. Microsatellite DNA: a tool for population genetic analysis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2002;96(Supplement 1):S21–S24. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(02)90047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tibayrenc M. Multilocus enzyme electrophoresis for parasites and other pathogens. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;551:13–25. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-999-4_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maiden MC. Multilocus Sequence Typing of Bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2006;60(1):561–588. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.030804.121325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Powell W, et al. The comparison of RFLP, RAPD, AFLP and SSR (microsatellite) markers for germplasm analysis. Mol Breed. 1996;2:225–238. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Su X, Wellems TE. Toward a high-resolution Plasmodium falciparum linkage map: polymorphic markers from hundreds of simple sequence repeats. Genomics. 1996;33(3):430–44. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Havryliuk T, Ferreira MU. A closer look at multiple-clone Plasmodium vivax infections: detection methods, prevalence and consequences. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104(1):67–73. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762009000100011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson TJC, et al. Microsatellite Markers Reveal a Spectrum of Population Structures in the Malaria Parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17(10):1467–1482. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Imwong M, et al. Microsatellite Variation, Repeat Array Length, and Population History of Plasmodium vivax. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23(5):1016–1018. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooper A, et al. Genetic analysis of the human infective trypanosome Trypanosoma brucei gambiense: chromosomal segregation, crossing over, and the construction of a genetic map. Genome Biol. 2008;9(6):R103. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-6-r103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ajzenberg D, et al. Microsatellite analysis of Toxoplasma gondii shows considerable polymorphism structured into two main clonal groups. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32(1):27–38. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00301-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwenkenbecher JM, et al. Microsatellite analysis reveals genetic structure of Leishmania tropica. Int J Parasitol. 2006;36(2):237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oliveira RP, et al. Probing the genetic population structure of Trypanosoma cruzi with polymorphic microsatellites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(7):3776–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simo G, et al. Population genetic structure of Central African Trypanosoma brucei gambiense isolates using microsatellite DNA markers. Infect Genet Evol. 10(1):68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2009.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imwong M, et al. Contrasting genetic structure in Plasmodium vivax populations from Asia and South America. Int J Parasitol. 2007;37(8-9):1013–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferdig MT, Su XZ. Microsatellite markers and genetic mapping in Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitol Today. 2000;16(7):307–312. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(00)01676-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pearce RJ, et al. Multiple Origins and Regional Dispersal of Resistant dhps in African Plasmodium falciparum Malaria. PLoS Med. 2009;6(4):e1000055. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morin PA, et al. SNPs in ecology, evolution and conservation. Trends Ecol Evol. 2004;19(4):208–216. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edwards SV. Natural selection and phylogenetic analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(22):8799–800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904103106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carlton JM, et al. Draft genome sequence of the sexually transmitted pathogen Trichomonas vaginalis. Science. 2007;315(5809):207–12. doi: 10.1126/science.1132894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horner DS, et al. Molecular Data Suggest an Early Acquisition of the Mitochondrion Endosymbiont. Proc Biol Sci. 1996;263(1373):1053–1059. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1996.0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aurrecoechea C, et al. GiardiaDB and TrichDB: integrated genomic resources for the eukaryotic protist pathogens Giardia lamblia and Trichomonas vaginalis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Suppl 1):D526–530. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kofler R, S C, Lelley T. SciRoKo: a new tool for whole genome microsatellite search and investigation. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(13):1683–5. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Untergasser A, et al. Primer3Plus, an enhanced web interface to Primer3. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Web Server Issue) doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Z, et al. A greedy algorithm for aligning DNA sequences. J Comput Biol. 2000;7(1-2):203–14. doi: 10.1089/10665270050081478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Altschul SF, et al. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215(3):403–10. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Drmota T, Kral J. Karyotype of Trichomonas vaginalis. Europ J Protistol. 1997;33:131–135. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Excoffier L, Laval G, Schneider S. Arlequin (version 3.0): an integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evol Bioinform Online. 2005;1:47–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takezaki N, Nei M, Tamura K. POPTREE2: Software for constructing population trees from allele frequency data and computing other population statistics with Windows interface. Mol Biol Evol. 27(4):747–52. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nei M, Tajima F, Tateno Y. Accuracy of estimated phylogenetic trees from molecular data. II. Gene frequency data. J Mol Evol. 1983;19(2):153–70. doi: 10.1007/BF02300753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bandelt HJ, et al. Mitochondrial portraits of human populations using median networks. Genetics. 1995;141(2):743–53. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.2.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Keane T, et al. Assessment of methods for amino acid matrix selection and their use on empirical data shows that ad hoc assumptions for choice of matrix are not justified. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2006;6(1):29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-6-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guindon S, Gascuel O. A Simple, Fast, and Accurate Algorithm to Estimate Large Phylogenies by Maximum Likelihood. Syst Biol. 2003;52(5):696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gouy M, Guindon S, Gascuel O. SeaView version 4: A multiplatform graphical user interface for sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree building. Mol Biol Evol. 27(2):221–4. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tamura K, Nei M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol Biol Evol. 1993;10(3):512–26. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hasegawa M, Kishino H, Yano T. Dating of the human-ape splitting by a molecular clock of mitochondrial DNA. J Mol Evol. 1985;22(2):160–74. doi: 10.1007/BF02101694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Protas ME, et al. Genetic analysis of cavefish reveals molecular convergence in the evolution of albinism. Nat Genet. 2006;38(1):107–11. doi: 10.1038/ng1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oetting W, et al. Multiplexed short tandem repeat polymorphisms of the Weber 8A set of markers using tailed primers and infrared fluorescence detection. Electrophoresis. 1998;19(18):3079–83. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150191806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Malik SB, et al. An Expanded Inventory of Conserved Meiotic Genes Provides Evidence for Sex in Trichomonas vaginalis. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(8):e2879. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li J, et al. Typing Plasmodium yoelii microsatellites using a simple and affordable fluorescent labeling method. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2007;155(2):94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Feng X, et al. Experimental evidence for genetic recombination in the opportunistic pathogen Cryptosporidium parvum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2002;119(1):55–62. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(01)00393-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Asmundsson IM, Dubey JP, Rosenthal BM. A genetically diverse but distinct North American population of Sarcocystis neurona includes an overrepresented clone described by 12 microsatellite alleles. Infect Genet Evol. 2006;6(5):352–60. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.