Abstract

The upper gastrointestinal (GI) mucosa is exposed to endogenous and exogenous chemicals, including gastric acid, CO2 and nutrients. Mucosal chemical sensors are necessary to exert physiological responses such as secretion, digestion, absorption, and motility. We propose the mucosal chemosensing system by which luminal chemicals are sensed to trigger mucosal defense mechanisms via mucosal acid sensors and taste receptors. Luminal acid/CO2 is sensed via ecto- and cytosolic carbonic anhydrases and ion transporters in the epithelial cells and via acid sensors on the afferent nerves in the duodenum and esophagus. Gastric acid sensing is differentially mediated via endocrine cell acid sensors and afferent nerves. Furthermore, a luminal L-glutamate signal is mediated via epithelial L-glutamate receptors, including metabotropic glutamate receptors and taste receptor 1 family heterodimers, with activation of afferent nerves and cyclooxygenase, whereas luminal Ca2+ is differently sensed via calcium-sensing receptor in the duodenum. These luminal chemosensors help activate mucosal defense mechanisms in order to maintain the mucosal integrity and physiological responses of the upper GI tract. Stimulation of luminal chemosensing in the upper GI mucosa may prevent mucosal injury, affect nutrient metabolism, and modulate sensory nerve activity.

Keywords: acid sensor, vanilloid receptor, carbonic anhydrase, glutamate receptor, taste receptor, calcium-sensing receptor

Introduction

The upper gastrointestinal (GI) mucosa is regularly exposed to endogenous and exogenous chemicals. Typical endogenous substances are acid and CO2, the former is secreted from gastric parietal cells, and the latter generated by the mixture of gastric acid and secreted HCO3- from gastric and duodenal mucosa and pancreas. The exogenous substances are foodstuffs including nutrients such as glucose, amino acids, lipid and minerals. Physiological processes such as secretion, digestion, absorption, and motility occur in response to ingested substances, implying the presence of chemical sensors, in contrast to their volume effect via mechanical sensors.

How the upper GI mucosa is protected from the secreted acid has been studied for many years (Allen et al., 1993, Kaunitz and Akiba, 2002). Mucosal defense mechanisms protect the epithelium, since the cells cannot survive in such a low pH condition. Mucosal defense mechanisms consist of pre-epithelial, epithelial and subepithelial defense factors. In vivo microscopy and duodenal loop perfusion systems enable us to study these factors, including HCO3- and mucus secretion (pre-epithelial), intracellular pH (pHi) regulation with ion transporters and ecto- and cytosolic enzyme activities (epithelial), and blood flow regulated via afferent nerves and mediator releases (subepithelial). The esophageal, gastric and duodenal mucosae individually possess unique mucosal defense mechanisms (Kaunitz and Akiba, 2002). Since disruption of these defenses injures the mucosa, signals that enhance defense mechanisms may protect the mucosa from luminal substances in order to maintain epithelial integrity. Nevertheless, the mucosa needs to sense luminal acidity or substances in order to rapidly respond and enhance defense mechanisms.

Here, we will show how the upper GI mucosa, especially the duodenal mucosa senses luminal acidity under physiological conditions. Furthermore, we will discuss the presence of chemosensing receptors in the duodenum similar to those that populate the taste buds of the tongue, in particular such the receptors for an umami substance, monosodium L-glutamate (L-Glu) or amino acids, and for Ca2+. Amino acids or Ca2+ may be physiologically sensed by upper GI mucosa. Understanding how the GI mucosa ‘tastes’ luminal chemicals may help identify novel molecular targets in the treatment of mucosal injury, glucose metabolism and sensory sensitivity.

Duodenal acid sensing and H+/CO2 absorption

The duodenal mucosa, which is constantly and cyclically exposed to luminal acid and high PCO2 due to gastric acid and the secreted HCO3-, has multilayered, multistep defense mechanisms to counter acid-induced mucosal injury (Kaunitz and Akiba, 2003). These mechanisms coordinately regulate mucus and HCO3- secretion, pHi and cellular buffering, and submucosal neuronal activation and blood flow responses. Since duodenal luminal pH rapidly changes between 2 and 7 as a result of the constant mixture of secreted HCO3- with jets of antrally-propelled gastric acid, the duodenal mucosa must rapidly adjust its defense mechanisms according to luminal pH (Kaunitz and Akiba, 2006).

Since the 1980's, bicarbonate secretion has been the most extensively studied factor in the protection against luminal acid in the duodenum. Many studies were carried out in vivo, particularly by the Flemström and Takeuchi groups. These groups reported the importance of HCO3- secretion in mucosal protection and identified the secretory mechanisms involved in the regulation of HCO3- secretion (Allen and Flemström, 2005, Montrose et al., 2006). Using an in vivo microscopic system, we have studied, in addition to measuring the rate of HCO3- secretion, the integrated regulation of mucosal defense factors such as mucosal blood flow, mucus secretion, and enterocyte pHi in response to luminal acid in rat duodenum (Akiba et al., 2002). Luminal acid is sensed by the ‘capsaicin pathway’ which is comprised of epithelial cell acidification due to in-diffusing luminal acid, and H+ extrusion across the basolateral membrane via the Na+/H+ exchanger-1 (NHE1). The extruded H+ activates transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) on capsaicin-sensitive afferent nerves. Activated afferents release vasoactive mediators such as calcitonin-gene related peptide (CGRP) and nitric oxide (NO). Finally, mucosal blood flow and mucus secretion are increased, followed by cyclooxygenase (COX)-dependent mucus and HCO3- secretion (Kaunitz and Akiba, 2003, Akiba et al., 2002). These results demonstrate that the duodenal mucosa ‘tastes’ luminal acidity using epithelial ion transporters and neuronal acid sensors, and that intracellular acidification triggers the enhancement of mucosal defense mechanisms (Akiba and Kaunitz, 2009).

How does luminal acid acidify the epithelial cells in order to trigger mucosal defense mechanisms? The high level of PCO2, generated in the proximal duodenum, gradually declines in the jejunum (Rune and Henriksen, 1969), consistent with rapid CO2 absorption by the duodenal mucosa. Since the duodenal mucosa has the highest carbonic anhydrase (CA) activity in the GI tract (Sugai et al., 1994), which rapidly equilibrates H+ + HCO3- ↔ CO2 + H2O, we hypothesize that the duodenal mucosa absorbs luminal CO2 effectively by cytosolic and membrane-bound CA activities. Using duodenal loop perfusion with flow-through pH and CO2 electrodes, and simultaneous portal venous blood gas monitoring, we have found that luminal CO2 is CA-dependently absorbed by the duodenal epithelium with stimulated HCO3- secretion, accompanied by portal venous acidification (Mizumori et al., 2006). Furthermore, CO2-induced intracellular acidification of epithelial cells is also CA dependent and accompanied by a TRPV1-dependent hyperemic response (Akiba et al., 2006). These results suggest that luminal H+ is actively absorbed into the epithelium as CO2, which is converted into H+ and HCO3-, facilitated by membrane-bound and cytosolic CAs. Intracellular H+ is extruded via NHE-1, and sensed by the ‘capsaicin pathway’. This suggests that luminal H+ and CO2 provide equivalent acid loads, in terms of intracellular acidification, that trigger protective effector mechanisms. The duodenum absorbs luminal H+ secreted by the stomach in order to maintain the acid-base balance between the stomach and duodenum. Acid-base balance between the stomach and duodenum is clinically important, since loss of gastric content by vomiting in the patients with the pyloric obstruction induces acute metabolic alkalosis and hypochloremia (Gamble and Ross, 1925, Rune, 1965).

High PCO2-induced HCO3- secretion has also been confirmed by Takeuchi group (Sasaki et al., 2009), reporting that CO2-induced HCO3- secretion is differently regulated in the stomach and duodenum. Acid-induced intracellular acidification of the duodenal epithelial cells is also reported by Sjöblom et al, confirming the importance of CA activities in the acid-sensing pathway of the duodenum using knockout mice (Sjöblom et al., 2009).

Esophageal and Gastric acid sensing

Similar to the duodenal acid sensing, the esophageal mucosa also senses luminal acidity as the permeant gas CO2 with help of epithelial and neuronal CA activities and acid sensors, TRPV1 and acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs), in order to maintain the interstitial pH at a physiological level by hyperemic response to luminal H+/CO2 (Akiba et al., 2008, Akiba and Kaunitz, 2009). Although the exposure to luminal acid and high PCO2 is physiological in the duodenum, the presence of more than transient exposure of the esophageal mucosa to acid or high PCO2 solution may be pathological. Nevertheless, the beverages we often drink are low pH (pH 2 – 5) and the carbonated drinks have extremely high PCO2 (Kleinman, 2008, Sasaki et al., 2009). Furthermore, taste of carbonation on the tongue is mediated and sensed by CA activity and an acid sensor polycystic kidney disease 2-like 1 (PKD2L1) receptor (Chandrashekar et al., 2009), now named as TRPP3, further supporting our concept in esophageal and duodenal H+/CO2 sensing; CA activity and acid sensor are the essential components of H+/CO2 sensing similarly shared in the esophagus and duodenum. However, the major difference of role of CAs between esophagus and duodenum is that the duodenal mucosa actively absorbs H+/CO2 using CA activity (Mizumori et al., 2006), whereas the esophageal mucosa impedes or minimizes CO2 diffusion using CA activity (Akiba et al., 2008).

How luminal acidity is physiologically sensed by the gastric mucosa remains to be clarified. Gastric acid sensing, in terms of mucosal response to back-diffused acid has been often discussed under non-physiological condition. Hyperemic response to luminal acid requires mucosal barrier break by mild irritant such as ethanol, taurocholic acid or hypertonic NaCl solution (Tashima et al., 2002, Matsumoto et al., 1992, Holzer and Lippe, 1992). Once acid back-diffuses into subepithelium or submucosa, acid may stimulate acid sensors TRPV1 or ASICs on afferent nerves with COX activation, implicated in not only protective afferent responses, but also noxious sensation conducted to the central nervous system (Schicho et al., 2004, Holzer, 1998). Although CA activity is involved in the regulation of acid and HCO3- secretion in the stomach (Baron, 2000, Sasaki et al., 2009), the involvement of CAs in the gastric acid sensing remains to be studied.

In contrast to sensing of back-diffused acid, gastric physiological responses to luminal pH changes are well known in the regulation of acid secretion. Luminal pH changes and proteins affect gastric acid secretion via reciprocal regulation of gastrin and somatostatin secreted from antral endocrine cells (Richardson et al., 1976, Feldman and Grossman, 1980). Physiological gastric H+/CO2 sensing may be different from that of esophagus and duodenum (Akiba and Kaunitz, 2009, Sasaki et al., 2009), since the stomach does not absorb CO2 or H+ (Stevens et al., 1987) unless the mucosal barrier is disrupted. Although antral luminal pH changes stimulate gastric endocrine cells via activation of capsaicin-sensitive afferent nerves and CGRP release (Manela et al., 1995), the mechanism by which the endocrine cells or afferents sense pH changes is still unclear. Acid-induced CGRP release from the stomach is pH- and extracellular Ca2+-dependent, but independent on acid sensor TRPV1 or ASIC3 (Auer et al., 2010), implicating extracellular Ca2+ as a possible sensor ligand.

Gastric luminal pH sensing may be mediated by calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) expressed on gastric endocrine cells, in contrast to its expression in parietal cells (Busque et al., 2005). Gastrin release from antral G cells is stimulated by extracellular Ca2+ (Buchan et al., 2001). CaSR is pH-sensitive and stimulated by L-type amino acids (Quinn et al., 2004, Busque et al., 2005). The CaSR allosteric agonist cinacalcet increases serum gastrin level and basal acid output in healthy human subjects (Ceglia et al., 2009). Furthermore, CaSR knockout stomach lacks gastrin release response to luminal pH increase, Ca2+ or peptone (Wank, SA, NIDDK, NIH; unpublished communication). CaSR is also expressed in gastric D cells; furthermore cinacalcet stimulates somatostatin release from isolated D cells (Nakamura et al., 2010). These observations are consistent with the involvement of CaSR in gastric luminal pH sensing in physiology.

Nutrient sensing in the GI mucosa

The upper GI mucosa also senses various exogenous substances such as the salts, fatty acids, glucose, and amino acids present in food. While one mechanism for this detection is linked to nutrient absorption and processing by enterocytes (Raybould et al., 2006), another relates to the occurrence of nutrient-specific receptors on enterocyte apical membranes. Recent molecular studies have identified the structure of specific receptors on the tongue for the basic tastes (sweet, sour, salty, bitter, umami) (Lindemann, 2001). These receptors have been found in the GI tract. In addition to “salty” sensed by epithelial Na+ channels and “sourness” by H+-gated ion channels such as ASIC, the “sweet” receptor heterodimer (T1R2/T1R3) is expressed in small intestinal mucosa (Dyer et al., 2005, Margolskee et al., 2007, Mace et al., 2007). Bitter taste receptors of the type 2 taste receptor (T2R) family are also expressed in the GI tract (Wu et al., 2002). The expression of these taste receptors in the GI mucosa suggests the need to sense the luminal contents, presumably to detect the presence of nutrients and unfavorable substances, in order to optimize digestion, absorption, secretion, and motility. Luminal chemosensing has been reported for glucose, bitter substances and fatty acids in the GI tract (Margolskee et al., 2007, Raybould, 1999, Rozengurt, 2006). Furthermore, since upper GI acid/CO2 chemosensing is closely related to mucosal defense mechanisms, we suspect that mucosal defense factors may be modulated by luminal nutrients, acting via taste receptors in the upper GI mucosa.

Brush border ecto-enzyme-related luminal chemosensing also includes ATP-P2Y receptor signals with intestinal alkaline phosphatase activity in the duodenum (Akiba et al., 2007, Mizumori et al., 2009). The mechanisms of ATP sensing will be reviewed in elsewhere (Kaunitz and Akiba, 2010).

Effect of luminal L-glutamate on mucosal defenses

The receptor on the tongue for L-Glu, which is the primary nutrient conferring umami taste, is a heterodimer of T1R1 and T1R3 (Nelson et al., 2002, Zhao et al., 2003) and/or a metabotropic L-Glu receptor (mGluR) (Chaudhari et al., 2000, Toyono et al., 2003). These receptors, which belong to the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) superfamily, are localized, along with the specific G protein, α-gustducin in the epithelial cells of the GI tract (Dyer et al., 2005, Margolskee et al., 2007, Rozengurt, 2006, San Gabriel et al., 2007). Another candidate for L-Glu receptor is CaSR, whose activity is modified by certain amino acids (Busque et al., 2005). CaSR is also localized in the duodenal epithelial cells (Chattopadhyay et al., 1998). This observation suggests that the mucosa directly ‘tastes’ the luminal L-Glu or other amino acid, and may directly or indirectly conduct luminal information to the internal signaling systems. Indeed, luminal L-Glu stimulates gastric vagal afferents through the release of NO and 5-hyroxytryptamine (5-HT) (Uneyama et al., 2006). We thus hypothesized the presence of a sensing pathway for L-Glu and/or amino acids in the upper GI tract.

Using in vivo microscopic techniques, we have recently demonstrated that luminal L-Glu (0.1 -10 mM) dose-dependently increases pHi and mucus gel thickness, but not blood flow, in rat duodenum (Akiba et al., 2009). The gastric mucosa also similarly responds to luminal L-Glu (Akiba and Kaunitz, 2009). These effects of L-Glu are mediated by capsaicin- and indomethacin-sensitive pathways in the duodenum, suggesting the involvement of capsaicin-sensitive afferent nerves and COX activity, respectively. Real time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detects the expression of possible L-Glu receptor candidates including T1R1 and T1R3, mGluR1 and mGluR4, and CaSR in the gastric and duodenal mucosa, supporting the presence of L-Glu receptors in the epithelium (Akiba et al., 2009). Pretreatment with a phospholipase-C inhibitor U73122 inhibits L-Glu-induced cellular alkalinization and mucus secretion, supporting that the effects of L-Glu are mediated via GPCR activation (Akiba and Kaunitz, 2009). Co-perfusion of L-Glu and inosine monophosphate (IMP) increases duodenal HCO3- secretion. Furthermore, pre-perfusion with L-Glu inhibits supraphysiological acid-induced epithelial injury in the duodenum (Akiba et al., 2009), assessed by in vivo in situ propidium iodide staining (Akiba et al., 2001). These results suggest that luminal L-Glu enhances duodenal mucosal defenses possibly via L-Glu or amino acid receptor.

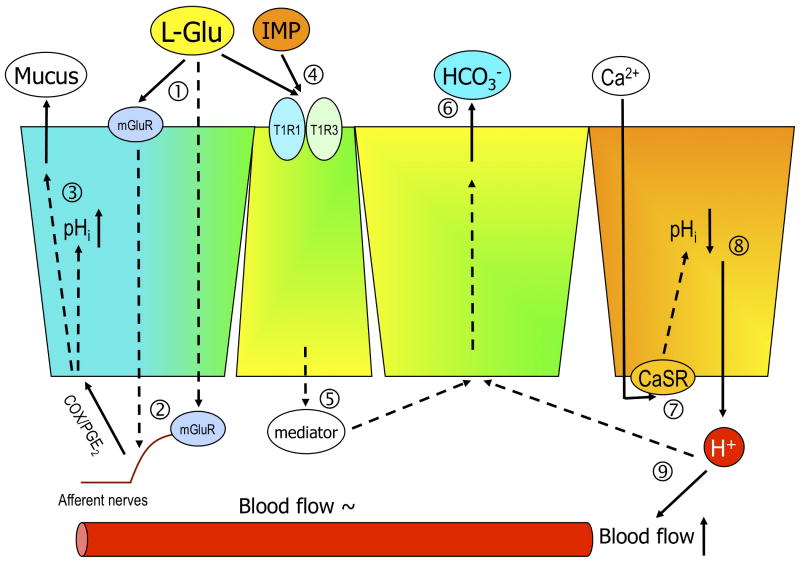

To further investigate the mechanisms underlying L-Glu-induced enhancement of duodenal mucosal defenses, we have studied the role of each candidate receptor for L-Glu in the duodenum. Our results show that luminal L-Glu enhances duodenal mucosal defenses via multiple pathways (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Luminal L-glutamate sensing pathways in the duodenum.

The scheme summarizes how luminal L-glutamate (L-Glu) affects the duodenal mucosal defenses. Luminal L-Glu activates epithelial (➀) or neuronal (➁) metabotropic Glu receptor (mGluR), stimulating afferent nerves and cyclooxygenase (COX), then ➂ alkalinizes the cells and increases mucus secretion. In contrast, L-Glu and inosine monophosphate (IMP) synergistically stimulate taste receptor 1 heterodimer T1R1/R3 (➃), whose activation may release mediators (➄), those increase HCO3- secretion (➅). Stimulation of calcium-sensing receptor (➆) on the epithelial cells induces intracellular acidification (➇), which triggers acid-sensing pathway (➈), increasing blood flow, and mucus and HCO3- secretion. pHi: intracellular pH, PGE2: prostaglandin E2.

Amino acid sensing via taste receptor type 1 heterodimer T1R1/T1R3

The taste receptor type 1 heterodimer T1R1/T1R3 has been identified as an amino acid receptor on the tongue (Nelson et al., 2002). T1R1/R3 is activated by certain L-amino acids in the mM range with synergistic enhancement by the presence of inosine monophosphate (IMP) (Nelson et al., 2002, Zhao et al., 2003), representing the specific characteristic of umami taste (Sato et al., 1970). The T1R1/R3 umami receptor and the T1R2/R3 sweet receptor are expressed in the intestinal mucosa (Jang et al., 2007, Bezencon et al., 2007, Mace et al., 2009). Since the luminal concentration of free amino acids reaches mM levels, which is the optimal concentration for T1R1/R3, after a protein-rich meal in human jejunum and ileum (Adibi and Mercer, 1973), the presence of amino acid sensing is predicted in the intestinal epithelium.

We have demonstrated that luminal co-perfusion of L-Glu and IMP synergistically stimulates duodenal HCO3- secretion in rat duodenum (Akiba et al., 2009), although L-Glu or IMP alone has a little effect, consistent with the activation of T1R1/R3. Furthermore, other amino acid, such as L-aspartate, L-leucine or L-alanine increases HCO3- secretion, enhanced by the addition of IMP (Akiba et al., 2009), also supporting the presence of T1R1/R3 in the duodenum. However, these amino acids do not mimic L-Glu effects on pHi and mucus gel thickness, suggesting that L-Glu-induced cellular alkalinization and mucus secretion are mediated via different pathways from T1Rs signaling. Although real-time PCR detects the expression of T1R1 and T1R3 in the duodenal mucosa (Akiba et al., 2009), lack of specific antibodies for T1Rs and of selective agonists or antagonists rather than amino acids limits to clearly localize T1Rs in the GI tract and directly prove the role of T1R1/R3 activation in duodenal HCO3- secretion. The localization of T1Rs in the GI tract is controversial. T1R1 and T1R3 are located on the apical membrane of rat jejunal enterocytes (Mace et al., 2007, Mace et al., 2009), whereas T1R3 is only expressed in the endocrine cells in human and mouse duodenum (Margolskee et al., 2007).

L-glutamate sensing via metabotropic glutamate receptors

A possible mGluR, serving umami perception, is mGluR1 or mGluR4, so far. We have demonstrated that luminal perfusion of mGluR1/5 agonist or mGluR4 agonist increases pHi and mucus gel thickness, and an mGluR4 antagonist inhibits L-Glu-induced increases of pHi and mucus gel thickness (Akiba et al., 2009). In contrast, mGluR agonists fail to affect duodenal HCO3- secretion, differently from L-Glu effects. These results suggest that L-Glu enhances duodenal mucosal defenses via mGluR4 activation, separately from T1Rs-mediated HCO3- secretion.

Calcium sensing via calcium-sensing receptors

CaSR is another candidate for L-Glu or amino acid receptor. CaSR is directly activated by extracellular Ca2+ and positively modulated by L-amino acids (Busque et al.). Although calcium absorption is believed to occur mostly in the ileum (Marcus and Lengemann, 1962), the duodenal mucosa also absorbs luminal Ca2+ via apical transporter TRPV6 (previously known as CaT1) and intracellular carrier calbindin-D9k (Bronner, 2009, Balesaria et al., 2009, Barley et al., 2001). Calcium absorption and luminal sensing may thus also occur in duodenum.

We have examined the effect of high luminal Ca2+ or a CaSR agonist spermine on pHi, mucus gel thickness, blood flow and HCO3- secretion in rat duodenum. The CaSR agonists acidify epithelial cells, and increase blood flow, mucus gel thickness and HCO3- secretion (Akiba et al., 2009). Activation of CaSR on the basolateral membrane acidifies epithelial cell monolayer (Aslanova et al., 2006), consistent with our result. These effects of CaSR activation on duodenal mucosal defenses are similar to the effects of luminal acid (Akiba and Kaunitz, 2009), but unlike the effects of luminal L-Glu. Selective CaSR agonist and antagonist will clarify the role of CaSR in L-Glu-induced mucosal protection.

Clinical perspective of nutrient receptors

Recent studies implicate T1R3 localization in the enteroendocrine cells to release incretin peptides, including gastric inhibitory peptide/glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). Gavage-administered D-glucose increase GLP-1 and GIP release in mice, and perfusion of D-glucose through intact duodenum in vivo or incubation of isolated duodenal mucosa in vitro with D-glucose increases GLP-1 release, whereas only GLP-1 release is reduced in α-gustducin knockout mice or knockout duodenum (Jang et al., 2007). Furthermore, an artificial sweetener sucralose as well as glucose and sucrose stimulates GLP-1 release from human enteroendocrine L cell line (Jang et al., 2007), the effect inhibited by human T1R3 receptor antagonist lactisole. Although the effect of artificial sweeteners on incretin release is still debated (Fujita et al., 2009), these findings suggest that the activation of T1Rs in the duodenum may release GLP-1 or GIP, the latter well studied by Flemström et al to stimulate duodenal HCO3- secretion (Flemström et al., 1982a, Flemström et al., 1982b). Enteroendocrine L cells also release GLP-2, another derivative from proglucagon, which mediates intestinal ion secretion (Baldassano et al., 2009) and intestinal cell growth (Tsai et al., 1997), further suggesting that the activation of duodenal T1Rs may increase HCO3- secretion. Our preliminary study have demonstrated that L-Glu/IMP-induced HCO3- secretion was reduced by a GLP-2 receptor antagonist, accompanied by GLP-1 and GLP-2 release, not by GIP release (Wang et al., 2010), supporting this hypothesis. A recent clinical study shows that oral administration of glutamine stimulates GLP-1 release in human (Greenfield et al., 2009). The multiple efficacies of GLP-2 (Dubé and Brubaker, 2007) and insulinotropic effect of GLP-1 (Kreymann et al., 1987) may lead us to consider the oral nutritional therapies for short bowel syndrome, intestinal mucosal injury and metabolic syndrome, especially diabetes mellitus.

Recently, duodenal chemosensing is implicated to the pathophysiology of functional dyspepsia (van Boxel et al., 2010). Many clinical studies attempt to implicate the abnormal chemosensing to dyspeptic symptoms. The strategy includes the increased stimulus intensity (increased acid secretion or decreased HCO3- secretion), increased expression of chemosensors (epithelial or afferent nerve endings), hypersensitivity of chemosensors (sensitization), and functional modulation of chemosensors (mucosal mediator release). Studying the physiological roles of luminal chemosensing may help to understand the pathophysiology of dyspeptic symptoms.

In conclusion, the upper GI mucosa ‘tastes’ luminal chemicals such as H+, CO2, amino acids, especially L-Glu, and Ca2+, those enhances mucosal defense mechanisms through specific signaling cascades, including epithelial ion transporters, enzymes and receptors, and capsaicin-sensitive afferent nerves and the COX pathway. The result is the protection of the duodenal mucosa from acid injury. Understanding luminal chemosensory mechanisms may help to identify novel molecular targets for treating and preventing mucosal injury, glucose metabolism and abnormal visceral sensation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Misa Mizumori, Maggie Ham, Chikako Watanabe, Takanari Nakano and Joonho Wang for their research contributions. Supported by a research grant from Ajinomoto Inc., Japan (Y. Akiba), Investigator-Sponsored Study Program of AstraZeneca IRUSESOM0424 (Y. Akiba), Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Review Award (J. Kaunitz), and NIH-NIDDK R01 DK54221 (J. Kaunitz).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None.

References

- Adibi SA, Mercer DW. Protein digestion in human intestine as reflected in luminal, mucosal, and plasma amino acid concentrations after meals. J Clin Invest. 1973;52:1586–1594. doi: 10.1172/JCI107335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiba Y, Furukawa O, Guth PH, Engel E, Nastaskin I, Sassani P, Dukkipatis R, Pushkin A, Kurtz I, Kaunitz JD. Cellular bicarbonate protects rat duodenal mucosa from acid-induced injury. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1807–1816. doi: 10.1172/JCI12218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiba Y, Ghayouri S, Takeuchi T, Mizumori M, Guth PH, Engel E, Swenson ER, Kaunitz JD. Carbonic anhydrases and mucosal vanilloid receptors help mediate the hyperemic response to luminal CO2 in rat duodenum. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:142–152. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiba Y, Kaunitz JD. Luminal chemosensing and upper gastrointestinal mucosal defenses. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:826S–831S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27462U. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiba Y, Mizumori M, Guth PH, Engel E, Kaunitz JD. Duodenal brush border intestinal alkaline phosphatase activity affects bicarbonate secretion in rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G1223–G1233. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00313.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiba Y, Mizumori M, Kuo M, Ham M, Guth PH, Engel E, Kaunitz JD. CO2 chemosensing in rat oesophagus. Gut. 2008;57:1654–1664. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.144378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiba Y, Nakamura M, Nagata H, Kaunitz JD, Ishii H. Acid-sensing pathways in rat gastrointestinal mucosa. J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:133–138. doi: 10.1007/BF03326432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiba Y, Watanabe C, Mizumori M, Kaunitz JD. Luminal L-glutamate enhances duodenal mucosal defense mechanisms via multiple glutamate receptors in rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;297:G781–G791. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90605.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen A, Flemström G. Gastroduodenal mucus bicarbonate barrier: protection against acid and pepsin. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C1–C19. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00102.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen A, Flemström G, Garner A, Kivilaakso E. Gastroduodenal mucosal protection. Physiol Rev. 1993;73:823–857. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1993.73.4.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslanova UF, Morimoto T, Farajov EI, Kumagai N, Nishino M, Sugawara N, Ohsaga A, Maruyama Y, Tsuchiya S, Takahashi S, Kondo Y. Chloride-dependent intracellular pH regulation via extracellular calcium-sensing receptor in the medullary thick ascending limb of the mouse kidney. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2006;210:291–300. doi: 10.1620/tjem.210.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auer J, Reeh PW, Fischer MJ. Acid-induced CGRP release from the stomach does not depend on TRPV1 or ASIC3. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:680–687. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldassano S, Liu S, Qu MH, Mule F, Wood JD. Glucagon-like peptide-2 modulates neurally-evoked mucosal chloride secretion in guinea pig small intestine in vitro. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;297:G800–G805. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00170.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balesaria S, Sangha S, Walters JR. Human duodenum responses to vitamin D metabolites of TRPV6 and other genes involved in calcium absorption. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;297:G1193–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00237.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barley NF, Howard A, O'Callaghan D, Legon S, Walters JR. Epithelial calcium transporter expression in human duodenum. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;280:G285–90. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.280.2.G285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron JH. Treatments of peptic ulcer. Mt Sinai J Med. 2000;67:63–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezencon C, le Coutre J, Damak S. Taste-signaling proteins are coexpressed in solitary intestinal epithelial cells. Chem Senses. 2007;32:41–49. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjl034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronner F. Recent developments in intestinal calcium absorption. Nutr Rev. 2009;67:109–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchan AM, Squires PE, Ring M, Meloche RM. Mechanism of action of the calcium-sensing receptor in human antral gastrin cells. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1128–1139. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.23246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busque SM, Kerstetter JE, Geibel JP, Insogna K. L-type amino acids stimulate gastric acid secretion by activation of the calcium-sensing receptor in parietal cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G664–G669. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00096.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceglia L, Harris SS, Rasmussen HM, Dawson-Hughes B. Activation of the calcium sensing receptor stimulates gastrin and gastric acid secretion in healthy participants. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:71–8. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0637-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrashekar J, Yarmolinsky D, von BL, Oka Y, Sly W, Ryba NJ, Zuker CS. The taste of carbonation. Science. 2009;326:443–445. doi: 10.1126/science.1174601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay N, Cheng I, Rogers K, Riccardi D, Hall A, Diaz R, Hebert SC, Soybel DI, Brown EM. Identification and localization of extracellular Ca2+-sensing receptor in rat intestine. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:G122–G130. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.274.1.G122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhari N, Landin AM, Roper SD. A metabotropic glutamate receptor variant functions as a taste receptor. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:113–119. doi: 10.1038/72053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubé PE, Brubaker PL. Frontiers in glucagon-like peptide-2: multiple actions, multiple mediators. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E460–E465. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00149.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer J, Salmon KS, Zibrik L, Shirazi-Beechey SP. Expression of sweet taste receptors of the T1R family in the intestinal tract and enteroendocrine cells. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:302–305. doi: 10.1042/BST0330302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman EJ, Grossman MI. Liver extract and its free amino acids equally stimulate gastric acid secretion. Am J Physiol. 1980;239:G493–G496. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1980.239.6.G493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flemström G, Garner A, Nylander O, Hurst BC, Heylings JR. Surface epithelial HCO3- transport by mammalian duodenum in vivo. Am J Physiol. 1982a;243:G348–G358. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1982.243.5.G348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flemström G, Heylings JR, Garner A. Gastric and duodenal HCO3- transport in vitro: effects of hormones and local transmitters. Am J Physiol. 1982b;242:G100–G110. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1982.242.2.G100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y, Wideman RD, Speck M, Asadi A, King DS, Webber TD, Haneda M, Kieffer TJ. Incretin release from gut is acutely enhanced by sugar but not by sweeteners in vivo. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296:E473–E479. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90636.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble JL, Ross SG. The factors in the dehydration following pyloric obstruction. J Clin Invest. 1925;1:403–423. doi: 10.1172/JCI100021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield JR, Farooqi IS, Keogh JM, Henning E, Habib AM, Blackwood A, Reimann F, Holst JJ, Gribble FM. Oral glutamine increases circulating glucagon-like peptide 1, glucagon, and insulin concentrations in lean, obese, and type 2 diabetic subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:106–113. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzer P. Neural emergency system in the stomach. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:823–839. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70597-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzer P, Lippe IT. Gastric mucosal hyperemia due to acid backdiffusion depends on splanchnic nerve activity. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:G505–G509. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1992.262.3.G505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang HJ, Kokrashvili Z, Theodorakis MJ, Carlson OD, Kim BJ, Zhou J, Kim HH, Xu X, Chan SL, Juhaszova M, Bernier M, Mosinger B, Margolskee RF, Egan JM. Gut-expressed gustducin and taste receptors regulate secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15069–15074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706890104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaunitz JD, Akiba Y. Luminal acid elicits a protective duodenal mucosal response. Keio J Med. 2002;51:29–35. doi: 10.2302/kjm.51.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaunitz JD, Akiba Y. Acid-sensing protective mechanisms of duodenum. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2003;54:19–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaunitz JD, Akiba Y. Duodenal carbonic anhydrase: mucosal protection, luminal chemosensing, and gastric acid disposal. Keio J Med. 2006;55:96–106. doi: 10.2302/kjm.55.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaunitz JD, Akiba Y. Purinergic regulation of duodenal surface pH and ATP concentration: implications for mucosal defense, lipid uptake, and cystic fibrosis. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2010.02156.x. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman RE. Protection of the gastrointestinal tract epithelium against damage from low pH beverages. J Food Sci. 2008;73:R99–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2008.00863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreymann B, Williams G, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR. Glucagon-like peptide-1 7-36: a physiological incretin in man. Lancet. 1987;2:1300–1304. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann B. Receptors and transduction in taste. Nature. 2001;413:219–225. doi: 10.1038/35093032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace OJ, Affleck J, Patel N, Kellett GL. Sweet taste receptors in rat small intestine stimulate glucose absorption through apical GLUT2. J Physiol. 2007;582:379–392. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.130906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace OJ, Lister N, Morgan E, Shepherd E, Affleck J, Helliwell P, Bronk JR, Kellett GL, Meredith D, Boyd R, Pieri M, Bailey PD, Pettcrew R, Foley D. An energy supply network of nutrient absorption coordinated by calcium and T1R taste receptors in rat small intestine. J Physiol. 2009;587:195–210. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.159616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manela FD, Ren J, Gao J, McGuigan JE, Harty RF. Calcitonin gene-related peptide modulates acid-mediated regulation of somatostatin and gastrin release from rat antrum. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:701–6. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90376-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus CS, Lengemann FW. Absorption of Ca45 and Sr85 from solid and liquid food at various levels of the alimentary tract of the rat. J Nutr. 1962;77:155–60. doi: 10.1093/jn/77.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolskee RF, Dyer J, Kokrashvili Z, Salmon KS, Ilegems E, Daly K, Maillet EL, Ninomiya Y, Mosinger B, Shirazi-Beechey SP. T1R3 and gustducin in gut sense sugars to regulate expression of Na+-glucose cotransporter 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15075–15080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706678104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto J, Takeuchi K, Ueshima K, Okabe S. Role of capsaicin-sensitive afferent neurons in mucosal blood flow response of rat stomach induced by mild irritants. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:1336–1344. doi: 10.1007/BF01296001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizumori M, Ham M, Guth PH, Engel E, Kaunitz JD, Akiba Y. Intestinal alkaline phosphatase regulates protective surface microclimate pH in rat duodenum. J Physiol. 2009;587:3651–63. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.172270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizumori M, Meyerowitz J, Takeuchi T, Lim S, Lee P, Supuran CT, Guth PH, Engel E, Kaunitz JD, Akiba Y. Epithelial carbonic anhydrases facilitate PCO2 and pH regulation in rat duodenal mucosa. J Physiol. 2006;573:827–842. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.107581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montrose MH, Akiba Y, Takeuchi K, Kaunitz JD. Gastroduodenal mucosal defense. In: Johnson LR, editor. Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract. 4th. New York: Academic Press; 2006. pp. 1259–1291. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura E, Hasumura M, Gabriel AS, Uneyama H, Torii K. Functional role of calcium-sensing receptor on somatostatin release from rat gastric mucosa. Gastroenetrology. 2010;138(Suppl 1):S-404. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson G, Chandrashekar J, Hoon MA, Feng L, Zhao G, Ryba NJ, Zuker CS. An amino-acid taste receptor. Nature. 2002;416:199–202. doi: 10.1038/nature726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn SJ, Bai M, Brown EM. pH sensing by the calcium-sensing receptor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:37241–37249. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404520200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raybould HE. Nutrient tasting and signaling mechanisms in the gut. I. Sensing of lipid by the intestinal mucosa. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:G751–G755. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.4.G751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raybould HE, Glatzle J, Freeman SL, Whited K, Darcel N, Liou A, Bohan D. Detection of macronutrients in the intestinal wall. Auton Neurosci. 2006;125:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson CT, Walsh JH, Hicks MI, Fordtran JS. Studies on the mechanisms of food-stimulated gastric acid secretion in normal human subjects. J Clin Invest. 1976;58:623–31. doi: 10.1172/JCI108509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozengurt E. Taste receptors in the gastrointestinal tract. I. Bitter taste receptors and alpha-gustducin in the mammalian gut. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G171–G177. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00073.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rune SJ. The metabolic alkalosis following aspiration of gastric acid secretion. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1965;17:305–310. doi: 10.3109/00365516509077055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rune SJ, Henriksen FW. Carbon dioxide tensions in the proximal part of the canine gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterology. 1969;56:758–762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Gabriel AM, Maekawa T, Uneyama H, Yoshie S, Torii K. mGluR1 in the fundic glands of rat stomach. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:1119–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki Y, Aihara E, Ohashi Y, Okuda S, Takasuka H, Takahashi K, Takeuchi K. Stimulation by sparkling water of gastroduodenal HCO3- secretion in rats. Med Sci Monit. 2009;15:BR349–BR356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Yamashita S, Ogawa H. Potentiation of gustatory response to monosodium glutamate in rat chorda tympani fibers by addition of 5′-ribonucleotides. Jpn J Physiol. 1970;20:444–464. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.20.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schicho R, Florian W, Liebmann I, Holzer P, Lippe IT. Increased expression of TRPV1 receptor in dorsal root ganglia by acid insult of the rat gastric mucosa. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:1811–1818. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjöblom M, Singh AK, Zheng W, Wang J, Tuo BG, Krabbenhoft A, Riederer B, Gros G, Seidler U. Duodenal acidity “sensing” but not epithelial HCO3- supply is critically dependent on carbonic anhydrase II expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13094–13099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901488106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens MH, Thirlby RC, Feldman M. Mechanism for high PCO2 in gastric juice: roles of bicarbonate secretion and CO2 diffusion. Am J Physiol. 1987;253:G527–G530. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1987.253.4.G527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugai N, Okamura H, Tsunoda R. Histochemical localization of carbonic anhydrase in the rat duodenal epithelium. Fukushima J Med Sci. 1994;40:103–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashima K, Nakashima M, Kagawa S, Kato S, Takeuchi K. Gastric hyperemic response induced by acid back-diffusion in rat stomachs following barrier disruption -- relation to vanilloid type-1 receptors. Med Sci Monit. 2002;8:BR157–BR163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyono T, Seta Y, Kataoka S, Kawano S, Shigemoto R, Toyoshima K. Expression of metabotropic glutamate receptor group I in rat gustatory papillae. Cell Tissue Res. 2003;313:29–35. doi: 10.1007/s00441-003-0740-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai CH, Hill M, Asa SL, Brubaker PL, Drucker DJ. Intestinal growth-promoting properties of glucagon-like peptide-2 in mice. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:E77–E84. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.273.1.E77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uneyama H, Niijima A, San GA, Torii K. Luminal amino acid sensing in the rat gastric mucosa. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G1163–G1170. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00587.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Boxel OS, ter Linde JJ, Siersema PD, Smout AJ. Role of chemical stimulation of the duodenum in dyspeptic symptom generation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:803–811. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Akiba Y, Engel E, Guth PH, Kaunitz JD. Umami receptor activation increases duodenal bicarbonate secretion via GLP-2 release in rats. Gastroenterolgy. 2010;138(Suppl 1):S-405. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.184788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SV, Rozengurt N, Yang M, Young SH, Sinnett-Smith J, Rozengurt E. Expression of bitter taste receptors of the T2R family in the gastrointestinal tract and enteroendocrine STC-1 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2392–2397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042617699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao GQ, Zhang Y, Hoon MA, Chandrashekar J, Erlenbach I, Ryba NJ, Zuker CS. The receptors for mammalian sweet and umami taste. Cell. 2003;115:255–266. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00844-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]