Abstract

Introduction

Harmane, a potent tremor-producing β-carboline alkaloid, may play a role in the etiology of essential tremor (ET). Blood harmane concentrations are elevated in ET cases compared with controls yet the basis for this elevation remains unknown. Decreased metabolic conversion (harmane to harmine) is one possible explanation. Using a sample of >500 individuals, we hypothesized that defective metabolic conversion of harmane to harmine might underlie the observed elevated harmane concentration in ET, and therefore expected to find a higher harmane to harmine ratio in familial ET than in sporadic ET or controls.

Methods

Blood harmane and harmine concentrations were quantified by high performance liquid chromatography.

Results

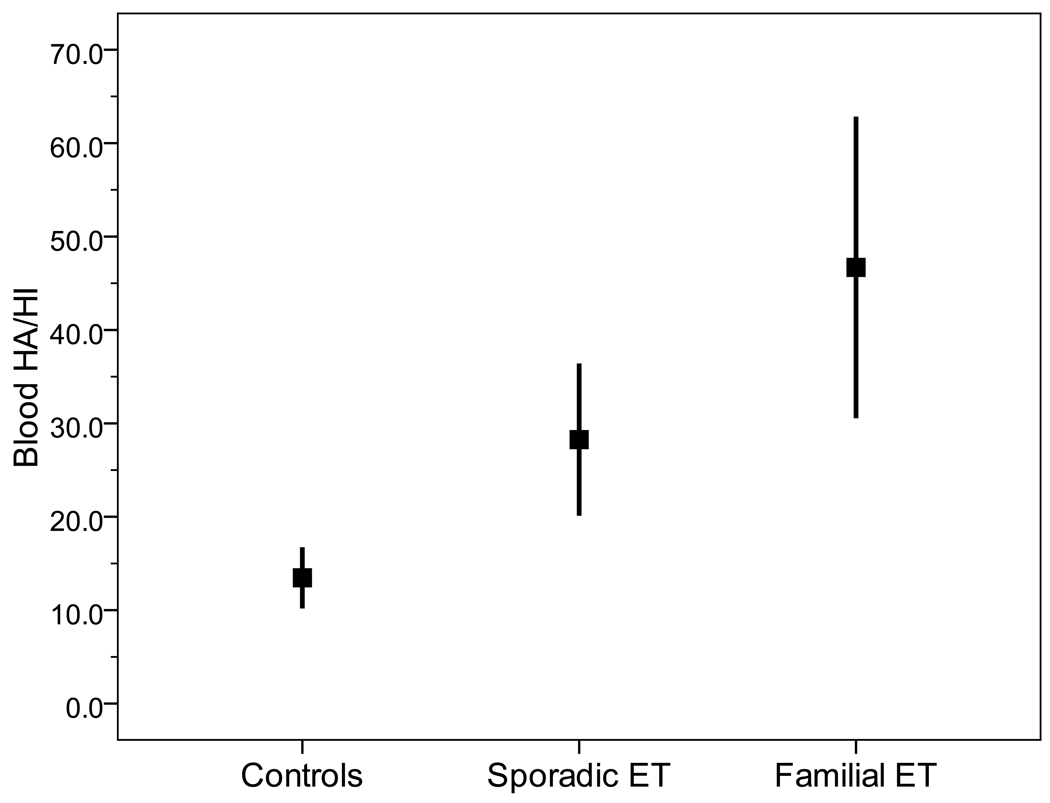

There were 78 familial ET cases, 187 sporadic ET cases, and 276 controls. Blood harmane and harmine concentrations were correlated with one another (Spearman’s r = 0.24, p < 0.001). The mean (±SD) harmane/harmine ratio = 23.4 ± 90.9 (range = 0.1 – 987.5). The harmane/harmine ratio was highest in familial ET (46.7 ± 140.4), intermediate in sporadic ET (28.3 ± 108.1), and lowest in controls (13.5 ± 50.3)(p = 0.03). In familial ET cases, there was no association between this ratio and tremor severity (Spearman’s r = 0.08, p=0.48) or tremor duration (Spearman’s r = 0.14, p = 0.24).

Conclusion

The basis for the elevated blood harmane concentration, particularly in familial ET, is not known, although the current findings (highest harmane/harmine ratio in familial ET cases) lends support to the possibility that it could be the result of a genetically-driven reduction in harmane metabolism.

Keywords: essential tremor, epidemiology, genetics, beta-carboline alkaloid, harmane, metabolism, biotransformation

1. Introduction

Essential tremor (ET), a neurological disease whose cardinal feature is action tremor of the arms, is widespread and it affects all age groups. With a prevalence of 4.0% in individuals aged ≥40 years and 8.7% in individuals in their ninth decade,1, 2 it is one of the most common neurological diseases.3, 4 In addition to action tremor, patients may exhibit a range of other neurological signs, including cognitive impairment,5 gait ataxia and incoordination.6 Both genetic 7–10 and non-genetic (i.e., environmental) factors11–13 are likely to play a role in disease etiology.

The β-carboline alkaloids are a group of neurotoxic chemicals that produce action tremor. Laboratory animals injected with high doses develop an acute action tremor that clinically resembles that seen in patients with ET.14, 15 Human volunteers who have been exposed to high doses may display a coarse, reversible action tremor.16

Harmane (1-methyl-9H-pyrido[3,4-β]indole) is among the most potent tremor-producing β-carboline alkaloids; subcutaneously administered harmane (38 mg/kg) produces tremor in mice.17 With its high lipid solubility,15 harmane is readily distributed to and within the brain.18–20 Brain concentrations are several fold higher than those in the blood in both exposed (i.e., harmane-injected) laboratory animals as well as control animals.15, 19 Although harmane is produced endogenously, it is also present in the diet; exogenous exposure is thought to be the primary source of bodily harmane.21

Hypothesizing that this neurotoxin could play an etiological role in ET, a disease for which no environmental toxins had as yet been identified, in 2002 we demonstrated that blood harmane concentration was elevated in an initial sample of 100 ET cases compared with 100 controls.22 In a replicate sample several years later (150 new ET cases and 135 new controls), we demonstrated a similar elevation; furthermore, we reported that concentrations were particularly high among familial ET cases.23

The basis for the elevated blood harmane concentration in ET is not known, although possibilities include increased dietary consumption and decreased metabolic turnover. An initial study of diet reported only weak evidence for dietary differences (i.e., slightly increased meat consumption) between male but not female ET cases and controls.24 We previously demonstrated that blood harmane concentration was highest in familial ET cases, providing support for the notion that genetic/metabolic factors are of mechanistic importance.23 The metabolic pathway for harmane is not fully known, although it is probable that it is converted by the liver cytochrome P-450 system to harmine (7-methoxy-1-methyl-9H-pyrido[3,4- β]-indole) through a simple hydroxylation and then methylation step.25

To further explore the genetic/metabolic hypothesis, we examined data on blood concentrations of harmane and harmine in more than 500 individuals, comprised of three groups: familial ET, sporadic ET and controls. We hypothesized that defective metabolic conversion of harmane to harmine might underlie the observed elevated harmane concentration in ET, and therefore expected to find a higher harmane to harmine ratio in familial ET than in sporadic ET or controls.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

Recruitment began in 2000 and continued to 2009. ET cases were enrolled in a study of the environmental epidemiology of ET at Columbia-University Medical Center (CUMC). By design, ET cases were identified from several sources, with the major ones being a computerized billing database of ET patients at the Neurological Institute of New York (CUMC) and advertisements to members of the International Essential Tremor Foundation.22, 23 All cases had received a diagnosis of ET from their treating neurologist and lived within two hours driving distance of CUMC in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut.

Control subjects were recruited during the same time period.22, 23 Controls were identified using random digit telephone dialing within a defined set of telephone area codes that were represented by the ET cases (e.g., 212, 201, 203, 516, 718, 914) within the New York Metropolitan area. Controls were frequency-matched to cases based on gender, race, and current age. The CUMC Internal Review Board approved of all study procedures and signed, written informed consent was obtained at the time of enrollment.22, 23

We excluded 134 participants who did not have phlebotomy (refusals, unsuccessful attempts); these 134 were similar to the remaining 541 participants in terms of diagnosis (22 [16.4%] vs. 78 [14.4%] familial ET, p = 0.56), gender (72 [53.7%] vs. 292 [54.0%] women, p = 0.96), education (15.1 ± 3.3 vs. 15.4 ± 3.5 years, p = 0.37), and number of rooms in their home (a socioeconomic variable) (5.8 ± 3.1 vs. 5.7 ± 2.7, p = 0.71). The 134 participants who were excluded were, on average, 5.3 years older than the remaining 541 participants (71.5 ± 12.7 vs. 66.2 ± 14.3 years, p <0.001).

2.2 Clinical Evaluation

All cases and controls were evaluated in person by a trained tester who administered clinical questionnaires and performed a videotaped examination. Most evaluations were home visits and, therefore, were performed in the late morning or early afternoon, making fasting blood harmane concentrations impractical. Our prior data indicate that blood harmane concentration is not correlated with the time latency since last food consumption (r = −0.097, p = 0.49 [N = 52]).23 Other published data suggest that plasma concentrations of harmane do not change significantly during the day.26 In one study,26 human subjects ingested food or ethanol, and plasma harmane concentrations were measured hourly for eight hours. The concentration remained stable. The same investigators also demonstrated that variability in concentration was minimal over a longer (i.e., three week) period.26

The tester used a structured questionnaire to collect demographic information (age in years, gender, years of education, race [non-Hispanic white vs. others], number of rooms in home), tremor characteristics (e.g., duration and age of onset), medication use, and family history information. ET cases were classified as having a familial ET if they reported at least one first-degree relative with ET; otherwise they were classified as sporadic ET. Current smoking status was assessed in each participant. Medical co-morbidity was assessed with the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale, in which the severity of medical problems (0 [none] - 3 [severe]) was rated in 14 bodily systems (e.g., cardiac, hepatic) and a Cumulative Illness Rating Scale score was assigned (range = 0 – 42) to each participant.27 Data were also collected on ethanol intake and converted into number of grams of ethanol consumed per day. In the final months of 2006, data collection began on the time latency between last ingestion of food or beverages and time of phlebotomy.

Weight and height were assessed using a balance scale designed for field surveys (Scale-Tronix 5600, White Plains, NY) and a movable anthropometer (GPM Martin Type, Pfister Inc, Carlstadt, NJ). Body mass index was calculated as weight in kg divided by the square of height in meters.

The tester videotaped a tremor examination in all participants.22, 28 Each of 12 videotaped action tremor items was rated by Dr. Louis on a scale from 0 to 3, a total tremor score was assigned (range = 0 – 36), and the diagnosis of ET was confirmed by Dr. Louis using published diagnostic criteria (moderate or greater amplitude tremor during ≥3 activities or a head tremor in the absence of Parkinson’s disease [PD], dystonia or another neurological disease).22, 28, 29 None of the cases or control subjects had PD or dystonia.

2.3 Blood Harmane Concentrations

At the time of the clinical evaluation, phlebotomy was performed. When the evaluation was performed in the participant’s home, blood tubes were temporarily stored on ice packs and then several hours later transferred to a −20° C freezer; if performed at CUMC, they were placed immediately into a −20° C freezer. Blood harmane and harmine concentrations were measured blinded to any clinical information with a well-established high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method used in our previous studies.22, 23, 30, 31 In short, one volume (9 –12 mL) of whole blood was mixed with half-a-volume (5 – 6 mL) of 1 M NaOH. Following vortex for 30 sec., the samples were placed on a horizontal rotator and shaken at room temperature for 30 min. An aliquot (15 mL) of the extraction solution consisting of ethyl acetate and methyl-t-butyl ether (2:98, V:V) was added to the tube. The tube was then vigorously shaken by hand for 1–2 min, followed by shaking on a horizontal rotor at room temperature for 45 mins. After centrifugation at 3000 × g for 10 min, the upper organic phase was separated. The extraction procedure was repeated two additional times. The organic phase was combined and evaporated under nitrogen to dryness. The samples were reconstructed in 0.25 mL of methanol. After centrifugation at 3000 × g for 10 min, the supernatant was transferred to autosampler vials with sealed caps for HPLC analysis.

A Waters Model 2695XE complete HPLC system including autosampler, temperature control module, seal wash and degasser, and a Waters Model 2475 Multi-channel fluorescent detector was used for separation and quantification. Separation was accomplished using an ion-interaction, reversed-phase Econosphere C18 column (ODS2, 5 µm, 250 × 4.6 mm) attached to a Spherisorb guard column (ODS2, 5 µm, 10 × 4.6 mm). Both analytical and guard columns were purchased from Alltech (Deerfield, IL). An isocratic mobile phase consisted of 17.5 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.5 (equal molar concentration of both monobasic and dibasic potassium salts) and methanol (30:70, V:V). A 50-µL aliquot of sample extracts was injected and the separation performed at room temperature at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The detector was set at an excitation wavelength of 300 nm and an emission wavelength of 435 nm. A Dell Window based computer equipped with Waters data analysis package was used to collect and analyze the data. The identity of harmane and harmine on HPLC chromatographs previously has been clarified.25, 30 The intraday precision, measured as a coefficient of variation at 25 ng/mL, was 6.7% for harmane and 3.4% for harmine. The interday precision was 7.3% for harmane and 5.4% for harmine.30

2.4 Statistical Analyses

Chi-square tests were used to analyze proportions, and Student’s t tests were used to examine group differences in continuous variables.

The empirical distribution of blood harmane and harmine concentration were positively skewed (one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, z = 9.47 and 9.88, both p <0.001). Hence, non-parametric tests (Mann Whitney U, Kruskal-Wallis, Spearman’s rho) were used when assessing these variables.

HA/HI ratio was the blood harmane concentration divided by the blood harmine concentration. To assess the null hypothesis that HA/HI ratio did not differ by diagnostic group (familial ET vs. sporadic ET vs. controls), a Kruskal-Wallis test was performed. We considered a number of potential confounders (age in years, gender, race, years of education, number of rooms in home, body mass index, Cumulative Illness Rating scale score, current cigarette smoker). If any of these were associated with ET or blood harmane concentration in either univariate analyses or in prior publications, 22, 23 we performed stratified analyses, assessing whether the observed difference in HA/HI ratio remained stable within different strata. Due to the loss of power in these stratified analyses, p values were not reported; rather, the aim of these analyses was to determine whether the magnitude of the diagnostic group difference persisted after stratification. Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS (Version 17.0).

3. Results

There were 541 participants, including 265 ET cases (78 familial ET and 187 sporadic ET) and 276 controls. Familial ET cases were similar to controls with respect to all variables except body mass index and race (Table 1); sporadic ET cases differed from controls with respect to gender and race (Table 1). Mean disease duration (ET cases) was 24.9 +/− 20.2 years, age of tremor onset (ET cases) was 42.4 +/− 23.6 years, and 140 (52.8%) were taking a medication to treat ET.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 265 ET cases vs. 276 controls

| Characteristic | ET Cases (N = 265) |

Controls (N = 276) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Familial ET (N = 78) |

Sporadic ET (N = 187) |

||

| Age in years | 65.9 ± 18.0 | 66.1 ± 14.5 | 66.3 ± 12.9 |

| Female gender | 42 (53.8) | 87 (46.5)** | 163 (59.1) |

| Non-Hispanic white race | 74 (94.9)* | 174 (93.0)* | 237 (85.9) |

| Years of education | 15.9 ± 3.2 | 15.1 ± 3.8 | 15.4 ± 3.4 |

| Number of rooms in home | 6.1 ± 2.6 | 5.8 ± 2.5 | 5.5 ± 2.9 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.9 ± 4.2** | 26.8 ± 4.6 | 27.6 ± 5.9 |

| Current cigarette smoker | 3 (3.8) | 14 (7.5) | 24 (8.7) |

| Cumulative Illness Rating Scale score |

5.4 ± 4.3 | 5.7 ± 3.5 | 5.3 ± 3.8 |

Values are mean ± SD or numbers (percentages).

Chi-square tests and t-tests were used.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01 compared with controls.

Using our control sample, we examined the correlates of the HA/HI ratio. HA/HI ratio was associated with body mass index (Spearman’s r = 0.21, p <0.001) and modestly with number of rooms in home (Spearman’s r = 0.14, p = 0.02). HA/HI ratio was not associated with age in years (Spearman’s r = 0.05, p = 0.40), years of education (Spearman’s r = −0.05, p = 0.45) or Cumulative Illness Rating Scale score (Spearman’s r = 0.08, p = 0.20). HA/HI ratio did not differ by gender (19.3 ± 72.5 for men and 9.4 ± 25.0 for women, Mann Whitney z = 0.39, p = 0.70) or by race (14.1± 53.8 for non-Hispanic whites and 9.4 ± 18.4 for others, Mann Whitney z = 1.02, p = 0.31). There was no difference between current cigarette smokers and nonsmokers (19.7 ± 77.4 and 12.9 ± 47.1, Mann Whitney z = 0.46, p = 0.64). There were 61 controls whose data were available on the time latency between last ingestion of food or beverages and time of phlebotomy. There was no association between this latency and blood harmane concentration (Spearman’s r = 0.12, p = 0.34) or HA/HI ratio (Spearman’s r = 0.11, p = 0.41).

The blood harmane and harmine concentrations were significantly correlated with one another (Spearman’s r = 0.24, p < 0.001); the correlation was present for all three diagnostic groups (r = 0.27, p <0.001 [controls]; r = 0.19, p = 0.01 [sporadic ET]; r = 0.27, p = 0.02 [familial ET]).

The mean ± SD HA/HI ratio = 23.4 ± 90.9 (range = 0.1 – 987.5). The HA/HI ratio was highest in familial ET (46.7 ± 140.4), intermediate in sporadic ET (28.3 ± 108.1), and lowest in controls (13.5 ± 50.3)(Kruskal-Wallis p = 0.03)(Figure). We assessed the possible confounding effects of age, gender, race, body mass index and number of rooms in home on the association between diagnosis and HA/HI ratio (Table 2). Within nearly all strata, the HA/HI ratio was highest in familial ET, intermediate in sporadic ET and lowest in controls (Table 2), indicating that these covariates did not account for the observed association between HA/HI ratio and diagnosis. There were 125 participants with data on the time latency between last ingestion of food or beverages and time of phlebotomy; in both the shorter time latency and longer latency strata, the HA/HI ratio remained the highest in familial ET cases (Table 2). In a sensitivity analysis, we removed potential outlying HA/HI values, excluding the top 3% of values; the results were similar. The HA/HI ratio was highest in familial ET (13.3 ± 32.2), intermediate in sporadic ET (10.1 ± 20.8), and lowest in controls (8.9 ± 23.5)(Kruskal-Wallis p = 0.027).

Figure 1.

Blood HA/HI ratio by diagnosis. Means (boxes) and one standard error.

Table 2.

Blood HA/HI ratio in controls, sporadic ET and familial ET in different demographic and clinical strata

| Blood HA/HI ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | Sporadic ET | Familial ET | |

| Age (years) | |||

| Youngest tertile (≤64) | 15.5 ± 63.9 | 54.1 ± 172.7 | 20.4 ± 77.7 |

| Middle tertile (>64 – 73) | 16.3 ± 53.4 | 18.8 ± 59.2 | 30.9 ± 65.9 |

| Oldest tertile (>73) | 6.6 ± 11.8 | 11.6 ± 23.7 | 77.3 ± 199.7 |

| Gender | |||

| Men | 19.3 ± 72.5 | 20.5 ± 59.2 | 38.2 ± 90.2 |

| Women | 9.4 ± 25.0 | 37.2 ± 145.2 | 54.0 ± 173.1 |

| Race | |||

| White | 14.1 ± 53.8 | 28.2 ± 111.3 | 49.1 ± 143.8 |

| Non-white | 9.4 ± 18.4 | 28.9 ± 48.3 | 1.9 ± 0.5* |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | |||

| Lowest tertile (≤24.5) | 6.1 ± 15.8 | 17.5 ± 55.9 | 40.7 ± 123.5 |

| Middle tertile (24.6 – 28.1) | 18.4 ± 73.6 | 43.0 ± 128.7 | 59.6 ± 185.7 |

| Highest tertile (>28.1) | 15.9 ± 45.5 | 25.9 ± 129.4 | 38.1 ± 74.9 |

| Number of rooms in home | |||

| Lowest tertile (≤4) | 9.8 ± 37.0 | 21.0 ± 125.0 | 54.5 ± 100.6 |

| Middle tertile (5 – 6) | 13.1 ± 46.8 | 21.1 ± 53.0 | 33.8 ± 124.0 |

| Highest tertile (≥7) | 19.0 ± 67.4 | 42.6 ± 129.0 | 50.6 ± 171.6 |

| Latency since oral intake (hours) | |||

| Less than median (≤1.8) | 4.2 ± 5.2 | 8.7 ± 8.3 | 29.5 ± 36.3 |

| Greater than median (>1.8) | 24.4 ± 80.2 | 16.2 ± 44.2 | 213.5 ± 415.8** |

The number of subjects in this cell was very small; there were only 4 non-white participants with familial ET.

The number of subjects in this cell was very small; there were only 5 participants.

We assessed in ET cases whether use of ET medications or ethanol could have influenced their HA/HI ratio. There was no association with medication use (categorized as none, occasional, and daily, Kruskal-Wallis p = 0.16) or grams of ethanol consumed per day (Spearman’s r = 0.02, p = 0.80). In familial ET cases, there was no association between HA/HI ratio and tremor severity (Spearman’s r = 0.08, p = 0.48), age of tremor onset (Spearman’s r = −0.04, p = 0.73), or tremor duration (Spearman’s r = 0.14, p = 0.24).

4. Discussion

Aside from genetic factors7–10 non-genetic11–13 factors are likely to play a role in the etiology of ET.23 Indeed, environmental factors are thought to play a significant role in several late life neurological diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease and PD.32–35 The contribution of environmental risk factors to disease etiology has been examined in detail in epidemiological studies of these other diseases32, 33, 35, 36 and the identification of toxins such as 1-methyl 4-phenyl 1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) and pesticides as precipitants of PD, has greatly advanced our understanding of putative disease mechanisms; for example, the MPTP model has become one of the most commonly used experimental model for PD.37 By comparison, studies of such environmental toxins in ET lag far behind. It is often stated that approximately 50% of ET cases are nonfamilial. 38, 39 With a population prevalence for ET of 4.0% among persons aged 40 and older,1 this suggests that approximately 2.0% of the population aged ≥40 years has a nonfamilial form of ET, yet the environmental correlates for this tremor are only now beginning to be explored.

β-carboline alkaloids such as harmane are of interest in ET.22, 23 These toxins are structurally similar to MPTP.37, 40 Like MPTP, β-carboline alkaloids are highly neurotoxic, and the administration of β-carboline alkaloids to a wide variety of laboratory animals produces an action tremor that resembles ET.41 Indeed, β-carboline alkaloid administration is used as an animal model for ET and new pharmacotherapies are tested using exposed animals.42–46 β-carboline alkaloid-induced tremor shares clinical features and drug-response characteristics with ET.14, 46–50 Also, several of the underlying brain changes are similar, including Purkinje cell loss. 41, 46, 47, 51–55 β-carboline alkaloids are produced endogenously in the human body,56, 57 but dietary sources are estimated to be far greater than endogenous sources.21 β-carboline alkaloids are primarily found in meat at ng/g concentrations, and cooking leads to increased concentrations.58–60 In addition to the high concentrations in meat, β-carboline alkaloids are also present in lower concentrations in many plants, including tobacco and coffee.61 The effects of chronic, low-level β-carboline alkaloid exposure are not known.

Using a sample of more than 500 individuals, we demonstrated that the blood harmane/harmine ratio was highest in familial ET cases, intermediate in cases of sporadic ET, and lowest in controls without ET. These findings lend support to the notion that the elevated blood harmane concentration observed in ET could be the result of a genetically-driven reduction in harmane metabolism. The higher concentration of blood harmane in familial than sporadic ET cases, which is something we noted in our previous study, further supports this notion.23

Although the mean harmane/harmine ratio was 23.4, the range was considerable, with values as low as 0.1 and as high as 987.5. The explanation for the high variance is not known, although could include inter-individual differences in ability to metabolize harmane, inter-individual differences in dietary intake of harmane vs. harmine, and other factors.

In univariate analyses, the harmane/harmine ratio correlated weakly with the number of rooms in the participant’s home. This variable, used in prior publications,31, 62 is a socioeconomic indicator, although not as strong as household income or occupation. As a socioeconomic indicator, it could be a marker of weight and other health-related differences, underlying nutritional and dietary differences, or differences in other lifestyle factors.

This study had limitations. First, we did not assess fasting blood harmane concentrations because it was impractical to do so. Therefore, it is difficult to fully assess the extent, if any, to which our findings reflect a difference in dietary intake of harmane. However, data in a subsample of 61 of our controls indicated that there was no association between time elapsed from last food or beverage ingestion and blood harmane concentration (Spearman’s r = 0.12, p = 0.34) or HA/HI ratio (Spearman’s r = 0.11, p = 0.41), indicating that neither blood harmane nor the HA/HI ratio seemed to be a function of time since last food consumption. Also, in stratified analyses, the association between higher HA/HI ratio and familial ET remained robust in both shorter and longer time latency strata, further lessening the likelihood that dietary intake of harmane explained our results. Furthermore, there is no conceivable reason why familial ET cases should have diets higher in harmane or diets with a higher ratio of harmane to harmine than do their counterparts with sporadic ET. Second, we recognize that ET cases may not accurately report their family history information; nevertheless, we expect misclassification of cases to be non-differential and to bias our findings towards the null hypothesis. The study had several strengths. The first is the uniqueness of the question; there are no other studies that have examined this issue in ET or in other diseases. Second, we used a large sample size of more than 500 individuals that included both ET cases and controls. Finally, we were able to subdivide ET cases further by using family history information.

The basis for the elevated blood harmane concentration, particularly in familial ET, is not known, although these findings (highest harmane/harmine ratio in familial ET cases) lends support to the possibility that it could be the result of a genetically-driven reduction in harmane metabolism.

Acknowledgments

Elan D. Louis was funded by R01 NS39422, P30 ES09089, RR00645 (General Clinical Research Center) from the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD). Wei Zheng was funded by R01 NS39422 and R01 ES008146 from the National Institutes of Health (Research Triangle, NC).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial disclosure: The National Institutes of Health played no role in the study design, the collection of data, the analysis and interpretation of data, the writing of the report or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Statistical Analyses: The statistical analyses were conducted by Dr. Louis.

5. Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Dogu O, Sevim S, Camdeviren H, et al. Prevalence of essential tremor: door-to-door neurologic exams in Mersin Province, Turkey. Neurology. 2003;61(12):1804–1806. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000099075.19951.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benito-Leon J, Bermejo-Pareja F, Morales JM, Vega S, Molina JA. Prevalence of essential tremor in three elderly populations of central Spain. Mov Disord. 2003;18(4):389–394. doi: 10.1002/mds.10376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Louis ED, Thawani SP, Andrews HF. Prevalence of essential tremor in a multiethnic, community-based study in northern Manhattan, New York, N.Y. Neuroepidemiology. 2009;32(3):208–214. doi: 10.1159/000195691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Louis ED, Ferreira JJ. How common is the most common adult movement disorder? Update on the worldwide prevalence of essential tremor. Mov Disord. 2010;25:534–541. doi: 10.1002/mds.22838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benito-Leon J, Louis ED, Bermejo-Pareja F. Population-based case-control study of cognitive function in essential tremor. Neurology. 2006;66(1):69–74. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000192393.05850.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singer C, Sanchez-Ramos J, Weiner WJ. Gait abnormality in essential tremor. Mov Disord. 1994;9(2):193–196. doi: 10.1002/mds.870090212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Higgins JJ, Pho LT, Nee LE. A gene (ETM) for essential tremor maps to chromosome 2p22–p25. Mov Disord. 1997;12(6):859–864. doi: 10.1002/mds.870120605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gulcher JR, Jonsson P, Kong A, et al. Mapping of a familial essential tremor gene, FET1, to chromosome 3q13. Nat Genet. 1997;17(1):84–87. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark LN, Park N, Kisselev S, Rios E, Lee JH, Louis ED. Replication of the LINGO1 gene association with essential tremor in a North American population. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010 doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.27. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shatunov A, Sambuughin N, Jankovic J, et al. Genomewide scans in North American families reveal genetic linkage of essential tremor to a region on chromosome 6p23. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 9):2318–2331. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiménez-Jiménez FJ dT-HM, Alonso-Navarro H, Ayuso-Peralta L, Arévalo-Serrano J, Ballesteros-Barranco A, Puertas I, Jabbour-Wadih T, Barcenilla B. Environmental risk factors for essential tremor. Eur Neurol. 2007;58(2):106–113. doi: 10.1159/000103646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salemi G, Aridon P, Calagna G, Monte M, Savettieri G. Population-based case-control study of essential tremor. Ital J Neurol Sci. 1998;19(5):301–305. doi: 10.1007/BF00713856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Louis ED. Etiology of essential tremor: should we be searching for environmental causes? Mov Disord. 2001;16(5):822–829. doi: 10.1002/mds.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuentes JA, Longo VG. An investigation on the central effects of harmine, harmaline and related beta-carbolines. Neuropharmacology. 1971;10(1):15–23. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(71)90004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zetler G, Singbartl G, Schlosser L. Cerebral pharmacokinetics of tremor-producing harmala and iboga alkaloids. Pharmacology. 1972;7(4):237–248. doi: 10.1159/000136294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewin L. Untersuchungen Uber Banisteria caapi Sp. Arch Exp Pathol Pharmacol. 1928;129:133–149. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKenna DJ. Plant hallucinogens: springboards for psychotherapeutic drug discovery. Behav Brain Res. 1996;73(1–2):109–116. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(96)00079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moncrieff J. Determination of pharmacological levels of harmane, harmine and harmaline in mammalian brain tissue, cerebrospinal fluid and plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorimetric detection. J Chromatogr. 1989;496(2):269–278. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)82576-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson NJ, Tyacke RJ, Husbands SM, Nutt DJ, Hudson AL, Robinson ES. In vitro and ex vivo distribution of [3H]harmane, an endogenous beta-carboline, in rat brain. Neuropharmacology. 2006;50(3):269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsubara K, Collins MA, Akane A, et al. Potential bioactivated neurotoxicants, N-methylated beta-carbolinium ions, are present in human brain. Brain Res. 1993;610(1):90–96. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91221-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfau W, Skog K. Exposure to beta-carbolines norharman and harman. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2004;802(1):115–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2003.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Louis ED, Zheng W, Jurewicz EC, et al. Elevation of blood beta-carboline alkaloids in essential tremor. Neurology. 2002;59(12):1940–1944. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000038385.60538.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Louis ED, Jiang W, Pellegrino KM, et al. Elevated blood harmane (1-methyl-9H-pyrido[ 3,4-b]indole) concentrations in essential tremor. Neurotoxicology. 2008;29(2):294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Louis ED, Keating GA, Bogen KT, Rios E, Pellegrino KM, Factor-Litvak P. Dietary epidemiology of essential tremor: meat consumption and meat cooking practices. Neuroepidemiology. 2008;30(3):161–166. doi: 10.1159/000122333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guan Y, Louis ED, Zheng W. Toxicokinetics of tremorogenic natural products, harmane and harmine, in male Sprague-Dawley rats. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2001;64(8):645–660. doi: 10.1080/152873901753246241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rommelspacher H, Schmidt LG, May T. Plasma norharman (beta-carboline) levels are elevated in chronic alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1991;15(3):553–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1991.tb00559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Linn BS, Linn MW, Gurel L. Cumulative illness rating scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1968;16(5):622–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1968.tb02103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Louis ED, Ottman R, Ford B, et al. The Washington Heights-Inwood Genetic Study of Essential Tremor: methodologic issues in essential-tremor research. Neuroepidemiology. 1997;16(3):124–133. doi: 10.1159/000109681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Louis ED, Ford B, Lee H, Andrews H. Does a screening questionnaire for essential tremor agree with the physician's examination? Neurology. 1998;50(5):1351–1357. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.5.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheng W, Wang S, Barnes LF, Guan Y, Louis ED. Determination of harmane and harmine in human blood using reversed-phased high-performance liquid chromatography and fluorescence detection. Anal Biochem. 2000;279(2):125–129. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Louis ED, Zheng W, Applegate L, Shi L, Factor-Litvak P. Blood harmane concentrations and dietary protein consumption in essential tremor. Neurology. 2005;65(3):391–396. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000172352.88359.2d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gorell JM, Johnson CC, Rybicki BA, et al. Occupational exposure to manganese, copper, lead, iron, mercury and zinc and the risk of Parkinson's disease. Neurotoxicology. 1999;20(2–3):239–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Racette BA, McGee-Minnich L, Moerlein SM, Mink JW, Videen TO, Perlmutter JS. Welding-related parkinsonism: clinical features, treatment, and pathophysiology. Neurology. 2001;56(1):8–13. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baldereschi M, Inzitari M, Vanni P, Di Carlo A, Inzitari D. Pesticide exposure might be a strong risk factor for Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:128. doi: 10.1002/ana.21049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shcherbatykh I, Carpenter DO. The role of metals in the etiology of Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2007;11(2):191–205. doi: 10.3233/jad-2007-11207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morahan JM, Yu B, Trent RJ, Pamphlett R. Genetic susceptibility to environmental toxicants in ALS. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144(7):885–890. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Langston JW, Langston EB, Irwin I. MPTP-induced parkinsonism in human and non-human primates--clinical and experimental aspects. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 1984;100:49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lambert D, Waters CH. Essential Tremor. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 1999;1(1):6–13. doi: 10.1007/s11940-999-0027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Louis ED, Ottman R. How familial is familial tremor? The genetic epidemiology of essential tremor. Neurology. 1996;46(5):1200–1205. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.5.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smeyne RJ, Jackson-Lewis V. The MPTP model of Parkinson's disease. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;134(1):57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Du W, Aloyo VJ, Harvey JA. Harmaline competitively inhibits [3H]MK-801 binding to the NMDA receptor in rabbit brain. Brain Res. 1997;770(1–2):26–29. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00606-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martin FC, Handforth A. Carbenoxolone and mefloquine suppress tremor in the harmaline mouse model of essential tremor. Mov Disord. 2006;21(10):1641–1649. doi: 10.1002/mds.20940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martin FC, Thu Le A, Handforth A. Harmaline-induced tremor as a potential preclinical screening method for essential tremor medications. Mov Disord. 2005;20(3):298–305. doi: 10.1002/mds.20331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krahl SE, Martin FC, Handforth A. Vagus nerve stimulation inhibits harmaline-induced tremor. Brain Res. 2004;1011(1):135–138. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Handforth A, Krahl SE. Suppression of harmaline-induced tremor in rats by vagus nerve stimulation. Mov Disord. 2001;16(1):84–88. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(200101)16:1<84::aid-mds1010>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sinton CM, Krosser BI, Walton KD, Llinas RR. The effectiveness of different isomers of octanol as blockers of harmaline-induced tremor. Pflugers Arch. 1989;414(1):31–36. doi: 10.1007/BF00585623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Milner TE, Cadoret G, Lessard L, Smith AM. EMG analysis of harmaline-induced tremor in normal and three strains of mutant mice with Purkinje cell degeneration and the role of the inferior olive. J Neurophysiol. 1995;73(6):2568–2577. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.6.2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trouvin JH, Jacqmin P, Rouch C, Lesne M, Jacquot C. Benzodiazepine receptors are involved in tabernanthine-induced tremor: in vitro and in vivo evidence. Eur J Pharmacol. 1987;140(3):303–309. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(87)90287-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cross AJ, Misra A, Sandilands A, Taylor MJ, Green AR. Effect of chlormethiazole, dizocilpine and pentobarbital on harmaline-induced increase of cerebellar cyclic GMP and tremor. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993;111(1):96–98. doi: 10.1007/BF02257413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rappaport MS, Gentry RT, Schneider DR, Dole VP. Ethanol effects on harmaline-induced tremor and increase of cerebellar cyclic GMP. Life Sci. 1984;34(1):49–56. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(84)90329-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Louis ED, Faust PL, Vonsattel J-PG, et al. Neuropathological changes in essential tremor: 33 cases compared with 21 controls. Brain. 2007;130(12):3297–3307. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O'Hearn E, Long DB, Molliver ME. Ibogaine induces glial activation in parasagittal zones of the cerebellum. Neuroreport. 1993;4(3):299–302. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199303000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.O'Hearn E, Molliver ME. Degeneration of Purkinje cells in parasagittal zones of the cerebellar vermis after treatment with ibogaine or harmaline. Neuroscience. 1993;55(2):303–310. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90500-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O'Hearn E, Molliver ME. The olivocerebellar projection mediates ibogaine-induced degeneration of Purkinje cells: a model of indirect, trans-synaptic excitotoxicity. J Neurosci. 1997;17(22):8828–8841. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-22-08828.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Robertson HA. Harmaline-induced tremor: the benzodiazepine receptor as a site of action. Eur J Pharmacol. 1980;67(1):129–132. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(80)90020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gearhart DA, Collins MA, Lee JM, Neafsey EJ. Increased beta-carboline 9N-methyltransferase activity in the frontal cortex in Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2000;7(3):201–211. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wakabayashi K, Totsuka Y, Fukutome K, Oguri A, Ushiyama H, Sugimura T. Human exposure to mutagenic/carcinogenic heterocyclic amines and comutagenic beta-carbolines. Mutat Res. 1997;376(1–2):253–259. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(97)00050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gross GA, Turesky RJ, Fay LB, Stillwell WG, Skipper PL, Tannenbaum SR. Heterocyclic aromatic amine formation in grilled bacon, beef and fish and in grill scrapings. Carcinogenesis. 1993;14(11):2313–2318. doi: 10.1093/carcin/14.11.2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Skog K. Cooking procedures and food mutagens: a literature review. Food Chem Toxicol. 1993;31(9):655–675. doi: 10.1016/0278-6915(93)90049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Layton DW, Bogen KT, Knize MG, Hatch FT, Johnson VM, Felton JS. Cancer risk of heterocyclic amines in cooked foods: an analysis and implications for research. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16(1):39–52. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Herraiz T. Relative exposure to beta-carbolines norharman and harman from foods and tobacco smoke. Food Addit Contam. 2004;21(11):1041–1050. doi: 10.1080/02652030400019844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Louis ED, Applegate L, Graziano JH, Parides M, Slavkovich V, Bhat HK. Interaction between blood lead concentration and delta-amino-levulinic acid dehydratase gene polymorphisms increases the odds of essential tremor. Mov Disord. 2005;20(9):1170–1177. doi: 10.1002/mds.20565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]