Abstract

Stargazer (stg) mutant mice fail to express stargazin [transmembrane AMPA receptor regulatory protein γ2 (TARPγ2)] and consequently experience absence seizure-like thalamocortical spike-wave discharges that pervade the hippocampal formation via the dentate gyrus (DG). As in other seizure models, the dentate granule cells of stg develop elaborate reentrant axon collaterals and transiently overexpress brain-derived neurotrophic factor. We investigated whether GABAergic parameters were affected by the stg mutation in this brain region. GABAA receptor (GABAR) α4 and β3 subunits were consistently upregulated, GABAR δ expression appeared to be variably reduced, whereas GABAR α1, β2, and γ2 subunits and the GABAR synaptic anchoring protein gephyrin were essentially unaffected. We established that the α4βγ2 subunit-containing, flunitrazepam-insensitive subtype of GABARs, not normally a significant GABAR in DG neurons, was strongly upregulated in stg DG, apparently arising at the expense of extrasynaptic α4βδ-containing receptors. This change was associated with a reduction in neurosteroid-sensitive GABAR-mediated tonic current. This switch in GABAR subtypes was not reciprocated in the tottering mouse model of absence epilepsy implicating a unique, intrinsic adaptation of GABAergic networks in stg.

Contrary to previous reports that suggested that TARPγ2 is expressed in the dentate, we find that TARPγ2 was neither detected in stg nor control DG. We report that TARPγ8 is the principal TARP isoform found in the DG and that its expression is compromised by the stargazer mutation. These effects on GABAergic parameters and TARPγ8 expression are likely to arise as a consequence of failed expression of TARPγ2 elsewhere in the brain, resulting in hyperexcitable inputs to the dentate.

Keywords: hippocampus, stargazin, TARPs, AMPA receptors, GABAA receptors, absence epilepsy

Introduction

The stargazer (stg) mutant mouse arose by a spontaneous viral transposon insertion into and subsequent premature transcriptional arrest of the stargazin gene (Letts et al., 1998). Thus, stg mice fail to express stargazin protein (Ives et al., 2004). Stargazin is a member of the family of transmembrane AMPA receptor (AMPAR) regulatory proteins (TARPs) that are involved in AMPAR synaptic targeting and/or surface trafficking (Chen et al., 2000; Rouach et al., 2005). The TARPs (γ2, γ3, γ4, and γ8), of which stargazin is TARPγ2, are expressed in the brain in a temporal spatially regulated manner, with some brain areas and possibly single cells expressing multiple TARP isoforms (Tomita et al., 2003). TARPγ2 is reported to be heavily expressed in the cerebellum and moderately so in hippocampus (CA3 and dentate), cerebral cortex, thalamus, and olfactory bulb (Sharp et al., 2001; Tomita et al., 2003). In the cerebellum, the consequences of the stargazer mutation are primarily restricted to the cerebellar granule cells (CGCs), neurons that normally only express the TARPγ2 isoform. Consequently, mossy fiber–CGC synapses in stg are bereft of AMPARs and are subsequently electrically silent (Chen et al., 2000), leading to a CGC-specific deficit in brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression and signaling (Qiao et al., 1998). Paradoxically, neurons in the dentate of the hippocampal formation in stg experience spontaneous nonconvulsive bilaterally symmetrical 6–7 Hz spike-wave discharges (SWDs) (Chafetz et al., 1995), intense mossy fiber sprouting, and intermittent elevations of BDNF expression but without extensive cell injury (Qiao and Noebels, 1993b; Chafetz et al., 1995; Nahm and Noebels, 1998). This contrasts with convulsive seizure activity, which results in significant cell death in CA1/CA3 and hilar cells of the dentate gyrus (DG) (Leroy et al., 2004). Chronic depolarization of dentate granule cells after convulsive seizures mediates an apparent adaptive modification of their inhibitory potential, presumably to titrate the increased network excitability. Such adaptations include modified GABAA receptor (GABAR) subunit expression and subtype assembly, resulting in altered GABAR function, pharmacology, targeting, and clustering (Clark 1998; Nusser et al., 1998; Elmariah et al., 2004; Leroy et al., 2004). Whether GABAR plasticity is also induced in the stg DG by nonconvulsive SWDs has not been investigated. We have shown previously that neuronal GABAR expression in vitro is influenced by electrical activity (Ives et al., 2002), corroborated by our observations in electrically silent CGCs in stg in vivo (Thompson et al., 1998) in which GABAR α6 and β3 subunits and the flunitrazepam-insensitive (BZ-IS) subtype of GABAR were downregulated. Because electrical activity and BDNF expression is decreased in CGCs, although paradoxically increased in the DG of stg, we hypothesized that GABAR expression may be reciprocally compromised in the DG. Here we show that GABAR subtypes expressed in the DG of stg are rearranged by a mechanism that is not directly related to the stargazer mutation because we show that the dentate does not normally express TARPγ2. Furthermore, these specific GABAR rearrangements are not a common feature of absence epileptic phenotypes because they are not reciprocated in tottering (tg) mutant mice, indicating that a unique mechanism underpins this form of GABAR plasticity.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

Anti-GABAR α4(1–14), β3L(345–408), γ2(319–366), and δ(1–44) subunit-specific antibodies were as described previously (Sperk et al., 1997). Anti-GABAR α1(Cys1–15) antibody was a gift from Professor F. Anne Stephenson (School of Pharmacy, London, UK). Affinity-purified anti-NMDA NR1, extreme C-terminus-directed anti-TARPγ2 antibody (Ives et al., 2004), and N-terminus-directed anti-TARPγ8 antibodies (peptide sequence Cys1–14; MESLKRWNEERGLWC) were produced as described previously (Thompson et al., 2002; Ives et al., 2004). Anti-glutamate receptor subtype 2 (GluR2) antibody was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Calne, Wiltshire, UK). Anti-β-actin antibody was obtained from Sigma (Poole, UK). Anti-gephyrin antibody was obtained from Clontech (Cowley, Oxford, UK). Vectastain Elite ABC immunohistochemistry kits were purchased from Vector Laboratories (Peterborough, UK). Hyperfilm ECL, [3H]-sensitive autoradiography film, horseradish-peroxidase-linked anti-rabbit secondary antibodies, and [3H]flunitrazepam were purchased from Amersham Biosciences (Aylesbury, Bucks, UK). Horseradish-peroxidase-linked anti-goat secondary antibody was obtained from Pierce (Chester, Cheshire, UK). [3H]muscimol and [3H]Ro15-4513 (ethyl-8-azido-5,6-dihydro-5-methyl-6-oxo-4H-imidazo[1,5α][1,4]benzodiazepine-3-carboxylate) were purchased from PerkinElmer (Boston, MA). Flunitrazepam, 8-fluoro-5,6-dihydro-5-methyl-6-oxo-4H-imidazo[1,5α][1,4]benzodiazepine-3-carboxylate (flumazenil; and Ro15-1788), and Ro15-4513 were a gift from Hoffmann LaRoche (Basel, Switzerland).

Animals.

Wild-type strain for stargazer (C3B6Fe+; +/+), heterozygous (C3B6Fe+; +/stg) and homozygous stargazer mutant mice (C3B6Fe+; stg/stg), and wild-type strain for tottering (C57/B6+/+) and tottering (C57/B6 tg/tg) were maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum. All animal procedures were conducted according to the Scientific Procedures Act of 1986. No differences between +/+ and +/stg mice have been noted (Qiao et al., 1998; Hashimoto et al., 1999); therefore, we routinely combine +/+ and +/stg material for control experiments.

Ligand autoradiography.

Assays were performed according to Korpi et al. (2002) with minor modifications. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with a lethal dose of pentobarbitone before transcardial pressure perfusion with ice-cold PBS–NaNO2 (0.1% w/v) for 3 min at 10 ml/min, followed by ice-cold PBS–sucrose (10% w/v) for 10 min at 10 ml/min. Brains were dissected and immediately frozen in isopentane (−40°C), 1 min before sectioning (14 μm) at −21°C, and thaw mounting on polysine-coated glass slides (VWR International, Lutterworth, Leics, UK). Sections were air dried overnight and stored at −20°C until required. [3H]muscimol-labeled sections were preincubated in assay buffer, 0.31 m Tris-acetate, pH 7.1, for 15–20 min, before incubation in [3H]muscimol (20 nm) for 1 h at 4°C. GABA (1 mm) was used to define nonspecific binding. [3H]Ro15-4513 (20 nm) and [3H]flunitrazepam (5 nm) labeled sections were preincubated in assay buffer, 50 mm Tris-HCl, 120 mm NaCl, pH 7.4, for 15 min. Flunitrazepam (10 μm) was used to define the flunitrazepam-sensitive (BZ-SR) and the flunitrazepam-insensitive (BZ-ISR) subtypes. Ro15-1788 (10 μm) was used to define nonspecific binding.

Quantification of receptor autoradiographs.

Autoradiographs and calibration standards were scanned at 1200 dots per inch using a flatbed scanner. Grayscale intensities were estimated using NIH ImageJ software. Calibration curves were constructed for each ligand/exposure period using [3H] standards at 0.1–109.4 nCi/mg (Amersham Biosciences) so grayscale intensity could be transformed into absolute radioactivity. Five random subdomains of each dentate gyrus from a minimum of six comparable sections per mouse strain were used to yield an estimated mean intensity. Nonspecific binding values were subtracted from mean intensity values to resolve specific ligand binding. Statistical analysis was by Student’s t test, and p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Primary cerebellar granule cell cultures.

Cerebellar granule cell cultures were prepared from 5- to 6-d-old (postnatal day 5/6) mouse neonates as described previously (Ives et al., 2002). Granule cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum, glutamine (2 mm), and gentamycin (50 μg/ml), supplemented at 24 h, when appropriate, with 20 mm KCl (“25K” media). Fluorodeoxyuridine (80 μm) was added at 48 h to suppress the proliferation of non-neuronal cells. CGCs (7 d in vitro) were harvested in 0.5 ml/35 mm dish of solubilizing buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 6.8, 2% w/v SDS, and 2 mm EDTA) so that the expression levels of GABAR subunit proteins could be determined by immunoblotting.

Immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry was essentially as described previously (Thompson et al., 2002). Adult (2–6 months) mice were perfusion fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde. Free-floating sections (30 μm) were immunohistochemically stained using the Vectastain ABC Elite kit with 3,3-diaminobenzidine (0.5 mg/ml) and H2O2 (0.02%, v/v) in 50 mm Tris-buffered saline, pH 7.1, as horseradish peroxidase substrate.

Antigen retrieval.

When required, sections were incubated in 0.05 m sodium citrate, pH 8.6, for 30 min at room temperature and then heated to 90°C for 70 min as described previously (Peng et al., 2004). Sections were cooled to room temperature and washed in TBS before processing for immunohistochemistry.

Immunoblotting.

SDS-PAGE was performed in 10% polyacrylamide mini-slab gels (Thompson et al., 1998). Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane and probed with primary antibody overnight at 4°C at the following concentrations: anti-TARPγ2, 1–4 μg/ml; anti-TARPγ8, 0.5 μg/ml; anti-GluR2, 0.4–0.8 μg/ml; anti-NMDA NR1, 1 μg/ml; anti-GABAR α4, 0.5 μg/ml; anti-GABAR β3, 0.5 μg/ml; anti-GABAR γ2, 0.5 μg/ml; anti-GABAR δ, 1 μg/ml; and anti-gephyrin, 1:250. The enhanced chemiluminescence Western blotting system was used to detect immunoreactive species on Hyperfilm. Band intensities were quantified as described previously (Ives et al., 2002) using NIH ImageJ software.

Immunoprecipitations.

For immunoprecipitation (IP) of TARP complexes, Triton X-100 (1% v/v) soluble protein in incubation buffer [10 mm HEPES, pH 7.1, 100 mm KCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EGTA, and a protease mixture of pepstatin-A (1 μg/ml), leupeptin (1 μg/ml), aprotinin (1 μg/ml), PMSF (1 mm), and benzamidine (2 mm)] was mixed with antibody (10 μg), applied to washed protein-A beads, and incubated overnight at 4°C. After centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 1 min, the supernatant containing unbound proteins was removed (“unbound fraction”). The beads were washed three times with 1 ml of incubation buffer. To elute the precipitated proteins from the beads, 35 μl of 2× SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing DTT (20 mm) was applied, incubated at 95°C for 5 min, and then centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 1 min. The supernatant (“immunoprecipitated fraction”) was removed and used for immunoblotting. To analyze the unbound fraction, 100 μl samples were chloroform/methanol precipitated and resuspended in 50 μl of 2× SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing DTT (20 mm).

For immunoprecipitation of GABARs from dentate gyri, four control and four stargazer dentate gyri were homogenized by sonication in solubilization buffer comprising Na-deoxycholate (0.5% w/v), 10 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.5, 150 mm NaCl, and protease inhibitors. After incubation for 30 min at room temperature and then 1 h at 4°C, the soluble material was isolated by centrifugation at 150,000 × g for 45 min. Soluble extract (70 μg of protein) was incubated with 15 μg of anti-GABAR γ2(319–366) antibody overnight at 4°C. Immunoprecipitation (20 μl) in IP-low buffer (50 μl) [containing 50 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, and Triton X-100 (0.2% v/v), supplemented with 5% (w/v) dry-milk powder] was subsequently added and incubated for 2 h at 4°C. Precipitate was pelleted by centrifugation at 2700 × g for 5 min, and the pellet was washed three times with 500 μl of IP-low buffer before being resuspended in 70 μl of SDS-PAGE sample buffer (NuPage Western blotting system; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and Western blots were probed with digoxigenized anti-γ2(319–366), anti-β3(345–408), and anti-α4(1–14) antibodies. Primary antibodies were detected with anti-digoxigenin–alkaline phosphatase Fab fragments (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) and CDP-Star (Tropix, Bedford, MA). Immunoreactive species were visualized by chemiluminescence using the Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) Fluor-S Multiimager and were quantified using Quantity One (Bio-Rad).

Characterizing anti-TARP antibodies.

Full-length TARPγ2, TARPγ3, TARPγ4, and TARPγ8 cDNAs subcloned into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3 were a kind gift from Dr. Dane Chetkovich (Northwestern University, Chicago, IL). Plasmids were transiently transfected into HEK293 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Cells were collected in solubilizing buffer [2% (w/v) SDS, 50 mm Tris, pH 6.8, and 2 mm EDTA] 48 h after transfection. These recombinantly expressed TARP isoforms were used to test the specificity of our anti-TARP antibodies in immunoblots.

Electrophysiology.

Six- to 8-week-old male mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital (120 mg/kg, i.p.), and decapitated. Brains were rapidly dissected out into ice-cold modified artificial CSF (CSF) of the following composition (in mm): 248 sucrose, 3 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, and 10 glucose (saturated with 95% O2, 5% CO2). Coronal slices, 300 μm thick, were cut using a vibratome (VT1000S; Leica, Ora, Italy) and placed in a holding chamber at room temperature (20–24°C) in aCSF of the following composition (in mm): 124 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, and 10 glucose (bubbled with 95% O2, 5% CO2). Slices were incubated under these conditions for at least 1 h before recording began. Slices were placed in a custom-made recording chamber on the stage of a differential interference contrast microscope (E600FM DIC; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and perfused with room temperature (20–24°C) aCSF containing 2 mm kynurenic acid (Sigma, Castle Hill, New South Wales, Australia) at ∼2 ml/min. Visually identified dentate granule cells were patched with thin-walled borosilicate electrodes (4–6 ΜΩ) filled with the following solution (in mm): 125 CsCl, 10 HEPES, 10 EGTA, 5 QX-314 [2(triethylamino)-N-(2,6-dimethylphenyl) acetamine], 1 Na2ATP, 0.3 LiGTP, pH 7.35 with CsOH (held at −70 mV). Input conductance was measured using a 200 ms, 10 mV depolarizing step. Cells were held for at least 10 min to allow the pipette solution to dialyze the cell and the series resistance to equilibrate. If the series resistance increased above 30 MΩ or changed by >10% during the course of a recording, the data from that cell were excluded from additional analysis. Miniature IPSCs (mIPSCs) were filtered at 3 kHz and logged at 10 kHz (micro 1401; Cambridge Electronics Design, Cambridge, UK) to Spike 4 software. Events were detected off-line with MiniAnalysis (Synaptosoft, Decatur, GA) with threshold criteria of 10 pA and 50 pA/ms. For kinetic analysis, only fast-rising (10–90% rise time <4 ms) events (>100 per cell) with an approximately exponential decay profile were included. We used two-tailed, paired, and unpaired t tests for hypothesis testing, and p < 0.05 was regarded as significant.

Results

GABAR subtype expression in the dentate of stargazer

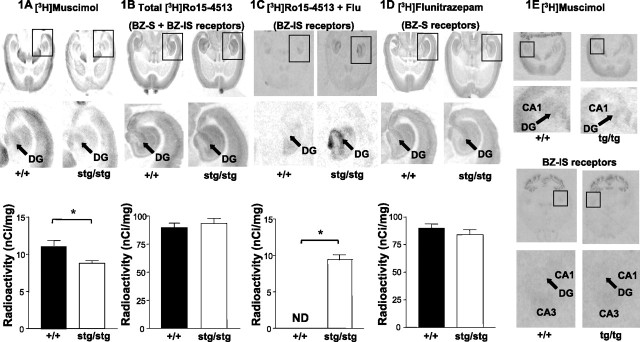

We initially investigated whether the stargazer mutation affected the distribution and abundance of the major GABAR subtypes expressed in the dentate gyrus. The distribution of [3H]muscimol binding in the DG of stg was mostly comparable with that in +/+ mice (Fig. 1A). The level of expression in the DG, however, was significantly reduced by 21 ± 8% (p < 0.05; n = 30) relative to controls (Fig. 1A). Sections were probed with [3H]Ro15-4513 to analyze the spatial expression pattern and relative propensity of the total repertoire of γ-subunit containing GABARs in the DG. No significant difference was observed in either terms of distribution or comparative abundance (Fig. 1B) (p = 0.57; n = 30). Intriguingly, the subtype of [3H]Ro15-4513 binding sites that are insensitive to flunitrazepam displacement (BZ-ISRs) were strongly upregulated in stg DG (Fig. 1C) (p < 0.01; n = 25). This subtype of GABAR was undetectable in this brain region of adult control mouse (Fig. 1C, +/+). The spatial expression pattern and relative abundance of the flunitrazepam-sensitive subtype of GABARs (BZ-SRs) was qualitatively demonstrated in autoradiograms of +/+ and stg sections probed with [3H]flunitrazepam (5 nm). No overt differences in distribution of [3H]flunitrazepam labeling (Fig. 1D) or in the grayscale intensity of labeling (data not shown) were found. Because the grayscale intensities obtained with [3H]flunitrazepam were beyond the highest calibration standard available to us and thus not suitable for quantification, we quantified the relative abundance of BZ-SRs by subtracting values obtained for BZ-ISRs (Fig. 1C) from total [3H]Ro15-4513 binding (BZ-SRs plus BZ-ISRs) (Fig. 1B). The level of expression of BZ-SRs calculated by this route was not significantly different (Fig. 1D bottom) (p = 0.39; n = 30).

Figure 1.

Distribution and abundance of GABAR subtypes expressed in the hippocampal formation of stargazer and tottering mice: in situ autoradiography. +/+, stg, and tg sections were incubated with [3H]muscimol (20 nm) to highlight α4βδ GABARs (A, E), [3H]Ro15-4513 (20 nm) to define BZ-S plus BZ-ISRs (B), [3H]Ro15-4513 (20 nm) plus flunitrazepam (Flu; 10 μm) to define BZ-ISRs (α4βγ2) alone (C, E), and [3H]flunitrazepam (5 nm) to highlight BZ-SRs alone (D). Autoradiographs were quantified by grayscale densitometry using NIH ImageJ software. Five random subdomains of each dentate gyrus from a minimum of six comparable sections per mouse strain were used to yield an estimated mean intensity. In C, ND indicates that a signal above film background was not detected in the DG. In all cases, nonspecific binding was at the level of film background. * indicates that values are statistically significantly different at the p < 0.05 level.

Is GABAR subtype plasticity in the DG common to all absence epilepsy models?

To establish whether this switch in GABAR expression profile was unique to stg or possibly a common feature of absence epilepsy models, we performed GABAR ligand in situ autoradiography in another well studied mouse model of absence epilepsy, tottering (tg). We found no evidence of a decrease of high-affinity [3H]muscimol binding sites or upregulation of BZ-ISRs in tg DG (Fig. 1E).

Evaluating GABAR subunit changes in the DG of stargazer

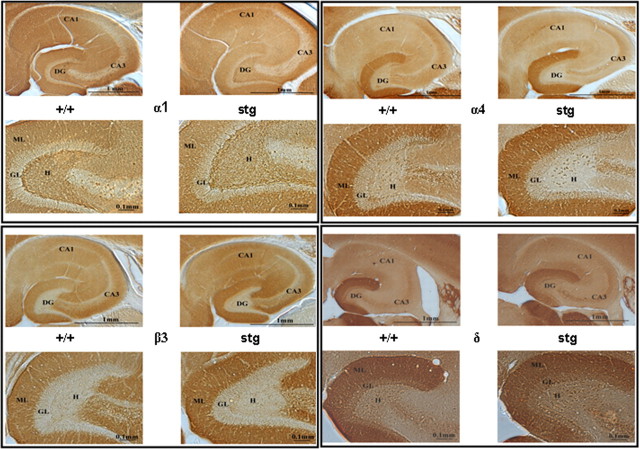

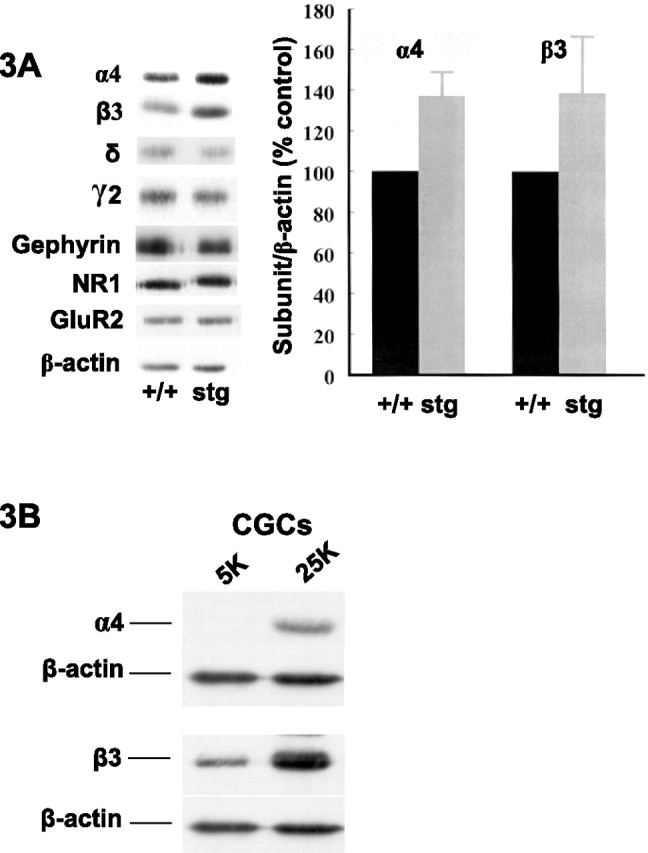

We next investigated whether the changes in GABAR subtype expression were paralleled by changes in the distribution (immunohistochemistry, hippocampal sections) and/or abundance (quantitative immunoblotting, DG membranes) of the principal GABAR subunits (α1, α2, α4, β1, β2, β3, γ2, and δ) expected to be expressed in the DG (Sperk et al., 1997) of age- and gender-matched +/+ and stg mice. No overt changes in the cellular distribution were observed (α1, α4, β3, and δ are shown in Fig. 2), although the intensity of staining (expression) for GABAR α4 and β3 subunits was higher in the entire molecular layer of the DG of stg mice relative to +/+ (Fig. 2). GABAR δ subunit expression, in contrast, was downregulated in the entire molecular layer of the DG of stg mice relative to +/+ (Fig. 2), although this observation was variable and not seen in all sections from all mice studied. No consistent changes in the intensity of staining with GABAR α1, α2, β1, β2, and γ2 specific antibodies were observed (Fig. 2). Quantitative immunoblotting identified GABAR α4 and β3 subunits as the only proteins studied that were significantly changed, being upregulated after normalization to β-actin expression by 37 ± 12% (n = 7; p = 0.0003) and 39 ± 28% (n = 6; p = 0.026), respectively, relative to controls (Fig. 3A). Expression levels of GABAR δ and γ2, NMDA receptor NR1, AMPA receptor GluR2, and GABAR anchoring protein gephyrin were not significantly different.

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical mapping of GABAR α1, α4, β3, and δ subunits in +/+ and stg. Paraformaldehyde-fixed adult +/+ and stg sections were immunostained with anti-GABAR α1 (0.25 μg/ml), α4 (0.5 μg/ml), β3 (0.5 μg/ml), and δ (0.25 μg/ml) subunit-specific antibodies. Although the relative distribution of GABAR α1, α4, β3, and δ subunits were essentially unaffected by the stargazer mutation, the relative intensity of GABAR α4 and β3 subunit immunostaining was increased in the molecular layers of the dentate gyrus of stg compared with +/+.

Figure 3.

GABAR α4 and β3 subunit levels are selectively upregulated in the DG of stg mice in vivo and in chronically depolarized cerebellar granule cells in vitro. A, Dentate gyri membranes from adult +/+ and stg mice were analyzed by quantitative immunoblotting (minimum of 4 mice of each strain and 2 immunoblots per mouse). Representative lanes of equal protein loading for each strain are shown for comparison. Only GABAR α4 and β3 subunit levels were significantly (p < 0.05) affected by the mutation, being increased relative to controls by 37 ± 12% (n = 7; p = 0.0003) and 39 ± 28% (n = 6; p = 0.026), respectively. B, Cerebellar granule cells were cultured under basal, “polarized” conditions (5 mm KCl) and “depolarized” conditions (25 mm KCl), the latter to mimic chronically depolarizing seizure activity. Cells were collected at 7 d in vitro and analyzed by immunoblotting. As in stg dentate granule cells, GABAR α4 and β3 subunits were upregulated.

We asked whether the changes in GABAR subunit expression in DG granule cells might be an adaptive response to SWDs pervading the hippocampal formation of stg. We subjected cultured CGCs from +/+ mice to KCl-mediated depolarization to mimic a chronically depolarizing, seizure-like scenario in vitro. The GABAR α4 subunit is not normally detected in CGCs, but, after KCl-mediated depolarization, α4 expression was clearly switched on (Fig. 3B). A concomitant upregulation of the β3 subunit was also detected (Fig. 3B), whereas expression of GABAR γ2 was unaffected, supporting our in vivo data that upregulation of α4 and β3 subunits in DG granules cells of stg occur in response to inputs from hyperexcitable afferents.

To verify that the upregulation of BZ-ISRs in the stg DG was a consequence of increased expression of α4βγ2 receptors, we dissected out dentate gyri from +/+ and stg. Na-deoxycholate-solubilized extracts were subsequently immunoprecipitated using anti-GABAR γ2 antibodies to isolate GABAR γ2-containing receptors. As expected, α4 was barely detectable in the γ2-containing subpopulation of receptors from +/+ DG, although it was clearly detectable in stg DG (experiments not shown). Changes in coassociation of γ2 with α4 and β3 subunits were then quantified by comparing the protein staining of the respective subunits in γ2-containing receptors of +/+ and stg DG. As indicated in Table 1, protein staining for γ2 subunits was comparable in γ2 precipitates of +/+ and stg, reflecting a similar amount of γ2-containing receptors in DG of these mice (Fig. 3). The amounts of α4 subunits, however, were dramatically higher (by 95%) in γ2 precipitates from stg than from +/+, confirming upregulation of assembled α4γ2-containing receptors in stg. Likewise, coassociation of β3 with γ2 was also upregulated (by ∼24%) in stg DG compared with +/+ (Table 1).

Table 1.

Western blot analysis of the relative abundance of α4 and β3 subunits coassociated with γ2 subunits in the dentate gyrus of control (+/+) and stargazer (stg) mice

| Subunits detected | Control |

Stargazer |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of mean | Mean % | % of mean (controls) | Mean % | |

| γ2 | 102 | 100 | 110 | 103 |

| 98 | 96 | |||

| α4 | 88 | 100 | 189 | 195 |

| 112 | 200 | |||

| β3 | 104 | 100 | 117 | 124 |

| 96 | 130 | |||

Dentate gyri from four +/+ and four stg mice were extracted with deoxycholate buffer. Equivalent amounts of extracted protein from each mouse strain was incubated with γ2(319–366) antibodies. Precipitated proteins were subjected to immunoblotting using digoxigenized γ2(319–366), α 4(1–14), and β3(345–408) antibodies as probes. Immunoreactive proteins were identified by chemiluminescence, and intensity of protein staining was quantified using the Bio-Rad Fluor-S Multi-Imager. Data are from a single experiment performed in duplicate. Results are expressed as a percentage of the mean value of staining of the respective subunit determined for γ2-precipitated +/+ extracts. The data indicated that comparable amounts of γ2-containing receptors were precipitated from +/+ and stg tissue extracts. In receptors precipitated from stg, however, significantly greater amounts of α 4 and β3 subunits were associated with γ2-containing receptors than from +/+.

Do the GABAR subunit changes result in modifications to synaptic GABA function?

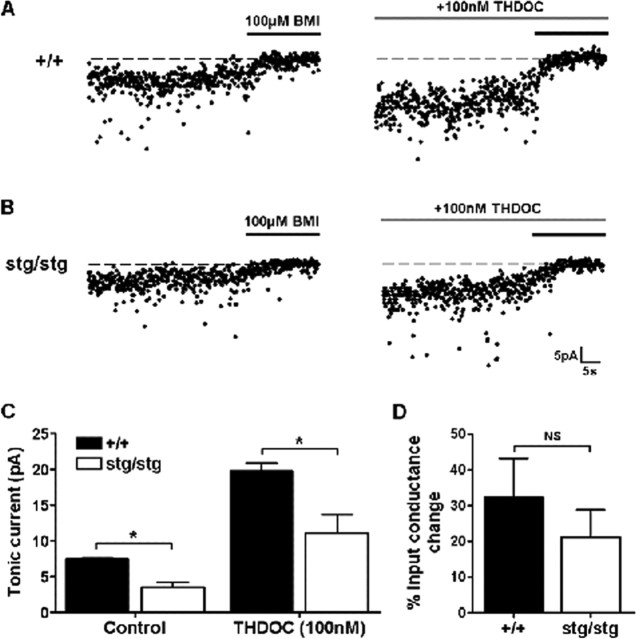

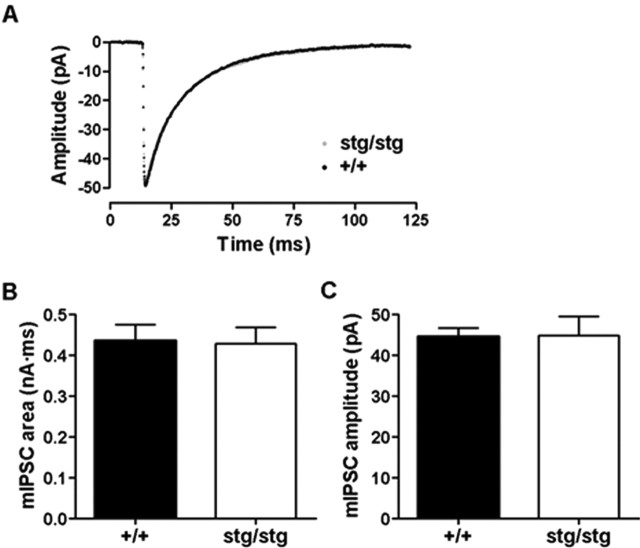

There was no significant difference in the input conductance of DG granule cells from stargazer and their nonepileptic littermates (0.99 ± 0.13 vs 1.29 ± 0.23 nS; n = 4; p > 0.05, unpaired t test). Bicuculline methiodide (BMI) (100 μm) sensitive GABAR-mediated tonic currents were significantly lower in the dentate granule cells of epileptic stg mice compared with asymptomatic littermates (7.5 ± 0.2 vs 3.5 ± 0.7 pA; n = 4–5; p < 0.05, unpaired t test) (Fig. 4). BMI significantly reduced the total input conductance in both phenotypes (+/+, 0.99 ± 0.13 vs 0.71 ± 0.19 nS, n = 4, p < 0.05, paired t test; Stg, 1.29 ± 0.23 vs 0.98 ± 0.21 nS, n = 4, p < 0.05, paired t test). However, the mean decrease in input conductance as a percentage of the initial conductance was larger in +/+ than in stg mice, although this difference did not reach statistical significance (32.4 ± 10.8 vs 21.1 ± 7.7%; n = 4; p > 0.05, unpaired t test) (Fig. 4D). The amount of tonic current was enhanced by the δ selective neurosteroid tetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone (THDOC) (100 nm) (Stell et al., 2003), but the amount of tonic current was still significantly lower in stg mice in the presence of the positive allosteric modulator (19.8 ± 1.0 vs 11.1 ± 2.6 pA; n = 4–5; p < 0.05, unpaired t test) (Fig. 4). Because spillover from synaptic activity is the likely source of the GABA that activates extrasynaptic GABARs, the difference in GABAR-mediated tonic current could reflect a difference in phasic GABA release, but there was no significant difference in the rate (0.92 ± 0.17 Hz for +/+ vs 0.93 ± 0.14 Hz for stg; n = 6; p > 0.05, unpaired t test) or amplitude (50.1 ± 4.6 pA for +/+ vs 48.3 ± 2.2 pA for stg; n = 6; p > 0.05, unpaired t test) of spontaneous IPSCs (data not shown). We postulated that the alteration in GABAR subunit composition reported here may result in alterations in the kinetics of phasic inhibitory currents. mIPSCs were isolated with tetrodotoxin (500 nm), and the kinetics of these events were compared between +/+ and stg mice. Averaged mIPSCs were essentially identical in epileptic and nonepileptic animals, and there was no significant difference in area (0.435 ± 0.04 nA/ms for +/+ vs 0.43 ± 0.04 nA/ms for stg; n = 4; p > 0.05, unpaired t test) (Fig. 5) or amplitude (44.5 ± 2.2 pA for +/+ vs 44.8 ± 4.8 pA for stg; n = 4; p > 0.05, unpaired t test) (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Tonic GABAR-mediated current in dentate gyrus granule cells. A, Representative traces of tonic GABAR-mediated currents in granule cells from +/+ mice and the effect of the δ subunit-selective neurosteroid THDOC (100 nm). Tonic currents were defined by the shift to current baseline after application of GABA antagonist BMI (100 μm). B, Representative traces of tonic GABAR-mediated currents in granule cells from stg mice and the effect of the δ subunit-selective neurosteroid THDOC (100 nm). C, Cells from +/+ mice showed significantly more tonic current than those from stg mice (7.5 ± 0.2 vs 3.5 ± 0.7 pA; n = 4–5; p < 0.0017, unpaired t test). In the presence of THDOC (100 nm), the tonic current was enhanced, and cells from +/+ mice showed significantly more tonic current than those from stg mice (19.8 ± 1.0 vs 11.1 ± 2.6 pA; n = 4–5; p < 0.0245, unpaired t test). The solid black line indicates application of BMI (100 μm) to define tonic current. D, The decrease in input conductance caused by BMI was not significantly (NS) different between +/+ and stg mice (32.4 ± 10.8 vs 21.1 ± 7.7%; n = 4; p > 0.05, unpaired t test). * indicates that values are statistcally significantly different at the p < 0.05 level.

Figure 5.

Kinetic features of mIPSCs in dentate granule cells. A, Averaged mIPSCs recorded in granule cells from stg and +/+ were essentially superimposable (n = 4). B, The mean area of mIPSCs from granule cells from +/+ mice and stg was not significantly different (0.435 ± 0.039 nA/ms for +/+ vs 0.429 ± 0.039 nA/ms for stg; n = 4; p > 0.05). C, The mean amplitude of mIPSCs in granule cells from +/+ mice and stg was not significantly different (44.5 ± 2.2 pA for +/+ vs 44.8 ± 4.8 pA for stg; n = 4; p > 0.05).

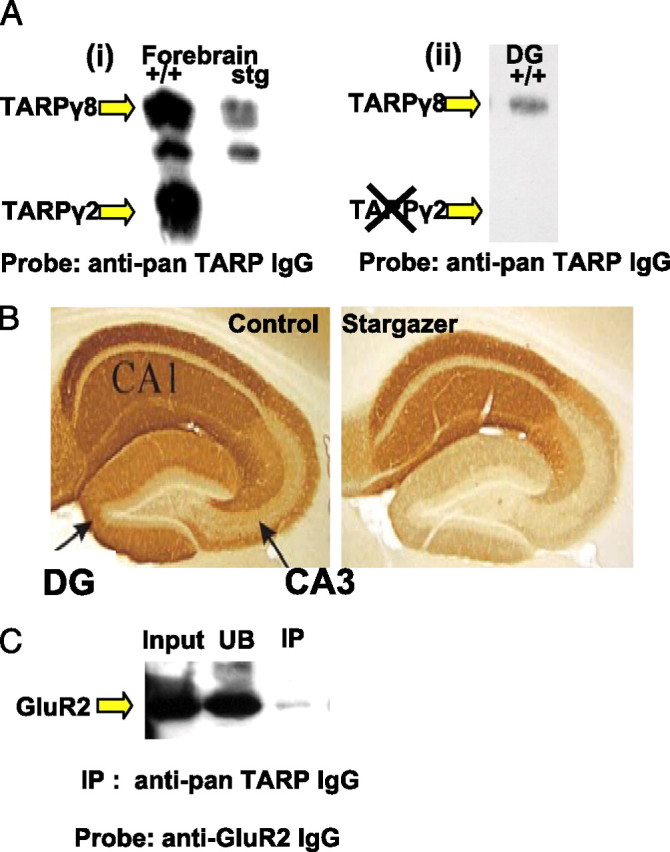

Are the GABAR rearrangements in the DG caused by the loss of TARPγ2 in this brain region?

To test whether the GABAR rearrangements we observed were a direct consequence of the stargazer mutation, we used peptide affinity-purified rabbit anti-TARP antibodies to elucidate the distribution and abundance of TARP isoforms expressed in the DG. A panel of our affinity-purified rabbit anti-peptide polyclonal antibodies to the C-terminus sequence of TARPγ2 was found to cross-react with TARPγ3 and TARPγ8 when screened against recombinantly expressed TARP isoforms (data not shown). We initially used this pan-TARP antibody as a probe in immunoblots against whole forebrain membranes from +/+ and stg mice. Three prominent immunoreactive species were recognized in this tissue from +/+, with Mr values of ∼55, ∼48, and 36–41 kDa (Fig. 6A). The 36–41 kDa species exhibits the same apparent molecular mass as recombinant TARPγ2 and was absent in stg (essentially TARPγ2−/− tissue), suggesting that the 36–41 kDa species corresponds to TARPγ2. The ∼55 and ∼48 kDa bands likely represent other TARP isoforms that this antibody recognizes, e.g., TARPγ8, that has a comparable mass when expressed in heterologous cells (data not shown). Interestingly, these bands appear less intense in whole forebrain from stg than from +/+. When we used this antibody as a probe for immunohistochemical mapping of TARP isoform distribution, we observed less intense immunostaining in the DG of stg relative to +/+ (Fig. 6B). The reduction in the immunostaining was consistent with the ablated expression of TARPγ2 in stg DG, because the stg mice are essentially TARPγ2−/− mutants. However, when we used dentate gyri from +/+ and stg for immunoblotting, we surprisingly found that the 36–41 kDa TARPγ2 protein, present in whole forebrain membranes derived from +/+ and absent from stg mice (Fig. 6A), was undetectable in the DG from +/+ mice. Only the Mr ∼55 kDa immunoreactive species was detected in the DG (Fig. 6A). This corresponded in mass to TARPγ8, a TARP-isoform known to be almost exclusively expressed in the hippocampal formation (Bredt and Nicoll, 2003). We subsequently raised a TARPγ8-specific antibody and verified that the Mr ∼55 kDa species identified by the pan-TARP antibody was TARPγ8 and that its expression was reduced in stg DG. By quantitative immunoblotting, we estimated that the expression of this protein was reduced by 33 ± 1% in stg DG membranes relative to +/+, in accordance with the reduced intensity of staining observed in the stg DG in situ (Fig. 6B). To verify that TARPγ8 was indeed an AMPAR-associated protein, we subjected Triton X-100-soluble DG from +/+ mice to an immunoprecipitation assay using the pan-TARP antibody. Because in the DG this antibody only labels TARPγ8 (Fig. 6A), it could be used to see whether this protein is associated with AMPAR. AMPAR GluR2 was coprecipitated, verifying that the protein recognized by this antibody was an AMPAR-associated protein (Fig. 6C). This was further verified by performing the same immunoprecipitation assay but using our anti-TARPγ8-specific antibody. GluR2 was likewise coprecipitated (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Characterizing TARP expression in the dentate gyrus. Ai, +/+ and stg forebrain membranes were probed with our anti-pan-TARP antibody. Three prominent immunoreactive species were identified, with Mr values of ∼55, ∼48, and 36–41 kDa; only the 36–41 kDa TARPγ2 protein is totally absent from stg. The ∼55 and ∼48 kDa species possibly represent TARP isoforms and are clearly less prominent in stg versus +/+, despite equal protein loading per lane. Aii, TARPγ2 is undetectable in the DG of +/+, and only the Mr ∼55 kDa protein is detected. This immunopositive species was also recognized by the TARPγ8-specific antibody in +/+ and stg DG, identifying it as TARPγ8. B, Paraformaldehyde-fixed sections from +/+ and stg mice were immunohistochemically probed with our anti-pan-TARP antibody. The DG in +/+ was clearly more heavily stained than the corresponding area in stg. C, TARPγ8 and its associated interacting proteins were immunoprecipitated from Triton X-100 (1% v/v) soluble extracts of DG from +/+ mice using the anti-pan-TARP antibody. Input (+/+ DG) is Triton X-100-soluble extract of DG from +/+ mice. UB is material that remained in the soluble supernatant after the immunoprecipitation. IP is immunoprecipitated material. These samples were probed with anti-GluR2 antibody to screen for the presence of interacting AMPAR. The GluR2 signal in the input lane represents 35% of material used in the IP.

Discussion

The stg mutation selectively and completely ablates expression of TARPγ2 (Ives et al., 2004), a member of the TARP family of AMPAR synaptic targeting and/or trafficking proteins (Chen et al., 2000; Tomita et al., 2003; Rouach et al., 2005). The effects of this mutation, however, on the hippocampal formation and cerebellum appear to be diametrically opposed. In the latter case, mossy fiber–CGC synapses are predictably silent, and the CGCs are functionally deafferentated and fail to express BDNF (Qiao et al., 1998; Hashimoto et al., 1999). Paradoxically, the hippocampus experiences spontaneous bursting activity and intermittent elevations of BDNF (Qiao and Noebels, 1993b; Chafetz et al., 1995; Nahm and Noebels, 1998).

GABAR plasticity

Inhibitory GABAergic networks adapt to changes in the strength of their excitatory inputs (Nusser et al., 1998; Ives et al., 2002; Leroy et al., 2004; Peng et al., 2004; Suzuki et al., 2005) and any accompanying changes in BDNF/TrkB signaling (Yamada et al., 2002; Elmariah et al., 2004; Jovanovic et al., 2004; Sato et al., 2005). In electrically silent, BDNF-deficient CGCs of stg, GABAR receptor α6 (the cerebellar counterpart of the α4 subunit in the DG) and β3 subunits and BZ-IS receptors were downregulated, whereas flunitrazepam-sensitive (BZ-S) receptors were unaffected (Thompson et al., 1998). In electrically hyperexcitable, BDNF overexpressing dentate granule cells of stg, we predicted opposite effects, which indeed we found. Steady-state levels of GABAR α4 and β3 and BZ-IS [3H]Ro15-4513 binding sites, a pharmacological fingerprint of α4βγ2 subunit-containing GABARs in the forebrain (Mihalek et al., 1999; Sun et al., 2004), were upregulated in the DG of stg (Figs. 1C, 3). Expression of the BZ-S subtype of GABARs was not significantly affected, emphasizing the specificity of the receptor switch we observed.

In the DG of wild-type mice, α4 preferentially assembles with δ to form α4βδ receptors. There is little evidence for its assembly into α4βγ2 receptors unless the ability to assemble with δ is compromised, e.g., in GABAR δ−/− (Mihalek et al., 1999; Korpi et al., 2002; Sun et al., 2004). In stg, we propose that the assembly of α4-containing receptors is compromised. By in situ autoradiography, high-affinity [3H]muscimol binding selectively highlights α4βδ GABARs in the forebrain (Mihalek et al., 1999; Korpi et al., 2002), which constituted a smaller proportion of total α4-containing receptors in stg compared with +/+. The α4βγ2 subtype (BZ-ISRs) however, was a prominent GABAR subtype in the DG of stg, constituting ∼10% of total [3H]Ro15-4513 binding sites, although it was undetectable in +/+ (Fig. 1C). Thus, our data imply that α4βγ2 receptors arose in stg DG at the expense of α4βδ receptors. This transformation in GABAR subtypes is entirely compatible with previous observations in both temporal lobe epilepsy (Nusser et al., 1998) and electroshock seizure models (Clark, 1998) and would predict a switch from tonic GABA responsive, neurosteroid-sensitive extrasynaptic α4-containing GABARs (α4βδ) to potentially synaptic α4-containing GABARs that are relatively neurosteroid insensitive and respond in phasic mode to synaptically released GABA (α4βγ2) (Nusser and Mody, 2002), a mechanism consistent with the recent observations of Elmariah et al. (2004). Our electrophysiological data support this prediction, because DG granule cells in stg show a reduced amount of neurosteroid-sensitive tonic current compared with their nonepileptic littermates (Stell et al., 2003). Because of the low abundance of α4βγ2 receptors in DG (<10% of total receptors) and the lack of drugs selectively modulating these receptors (Sieghart and Ernst, 2005), their presence at the synapse and function could not be investigated.

Our immunohistochemical studies indicated that δ expression was downregulated in stg DG (Fig. 2). A reduction in expression of the δ subunit would have been entirely compatible with the reduction in in situ muscimol binding and with the emergence of BZ-ISRs in the stg DG. However, this difference in δ immunostaining was variable between sections, a phenomenon that could not be explained by variability in the gender or age of animals used (our unpublished observation). Furthermore, the level of expression of δ and γ2 subunits were not significantly different in stg compared with controls when isolated dentate gyri were analyzed by immunoblotting (Fig. 3), nor did we see variability in our autoradiographic studies, in which all stg sections investigated showed evidence of the switch in GABAR subtypes. Studies in an appropriate dynamic cell system will be required to elucidate the mechanism that underpins the switch from α4βδ to α4βγ2 GABARs. Interestingly, we found that chronically depolarizing cerebellar granule cells in vitro upregulates α4 and β3 subunits in an L-type voltage-gated calcium channel-sensitive manner (H. L. Payne, J. H. Ives, W. Sieghart, and C. L. Thompson, unpublished observations). Calcineurin phosphatase activity downregulates GABAR δ expression (Sato et al., 2005); thus, activity-dependent calcium signaling-mediated upregulation of GABAR α4 and β3 and downregulation of δ offers a tentative mechanistic framework for future studies to evaluate what dictates the balance between expression and assembly of extrasynaptic (α4βδ receptors) and synaptic (α4βγ2 receptors) GABARs in the dentate granule cells.

One potential avenue for additional study is the influence of BDNF on GABAR plasticity in stg because the contrasting effects on GABAR expression in the DG and CGCs are mirrored by reciprocal effects on BDNF expression. BDNF/TrkB signaling has been implicated in the induction of both hyperexcitable mossy-fiber reentrant circuits in the DG (Koyama et al., 2004) and GABAergic plasticity. The latter included increased expression, surface trafficking and presumably stabilization of GABAR β3 subunit-containing receptors (Yamada et al., 2002; Jovanovic et al., 2004), increased GABAR cluster number, and synaptic localization (Elmariah et al., 2004). These features are all consistent with those reported here in stg.

The GABAR rearrangements we report in stg DG are, however, not a landmark feature of absence epilepsy. The absence epileptic mouse model tottering experiences a frequency of burst activity in the hippocampal formation that is similar to that reported in stg (∼6 Hz), but the abnormal DG GABAR profile is not reciprocated (Fig. 1E). However, the rate and duration of burst activity in tottering is approximately half that recorded in stg, and mossy-fiber axon collateralization is less extensive, as is the severity of their epileptic phenotype (Qiao and Noebels, 1993a; Zhang et al., 2002), leading us to propose that a threshold of hyperexcitability needs to be surpassed to activate the mechanisms responsible for the GABAergic plasticity evident in stg mice. It has been proposed recently that GABAergic plasticity is a homeostatic neuronal response that aims to balance network excitability (Elmariah et al., 2004). This may explain why high-frequency SWDs entering the hippocampal formation illicit rewiring similar to convulsant seizures but fail to induce the cell death that is a prominent feature of the latter.

TARP expression in the dentate

To rationalize the contrasting effects of the stargazer mutation in the cerebellum and hippocampus, we proposed two possibilities. (1) If TARPγ2 is expressed in the DG, then it must selectively regulate the activity of inhibitory networks, thus, burst activity in the stg hippocampus. (2) Alternatively, the failure to express TARPγ2 in other brain regions in stg (Qiao and Noebels, 1993a) was responsible for increased excitatory drive entering the stg DG. Using our pan-TARP and TARPγ8-specific antibodies, we showed that TARPγ2 is not present in the DG of +/+ mice. Our data provide compelling evidence that the dentate expresses the TARPγ8 isoform exclusively. Furthermore, TARPγ8 was downregulated in stg DG (Fig. 6C), consistent with the reduced immunostaining seen in situ (Fig. 6A), thus providing evidence that TARPγ8 expression is regulated by electrical activity. Because TARPγ2 is not expressed in DG, downregulation of TARPγ8, mossy-fiber axon collateralization, and receptor plasticity in the stg hippocampus (Chafetz et al., 1995; Nahm et al., 1998) has to arise through failed expression of TARPγ2 elsewhere in the stargazer brain. Despite the reduction of TARPγ8 expression in stg DG, we found no evidence of significant changes in the expression levels of AMPAR subunits (Fig. 3). This is in contrast to the TARPγ8−/− mouse, in which hippocampal GluR expression was found to be severely compromised (Rouach et al., 2005). We assume that the minor reduction of TARPγ8 expression in the stg DG is too small for us to detect any associated changes in the levels of AMPAR subunits.

In conclusion, we have shown that TARPγ2 is not expressed in the granule cells or interneurons of the dentate gyrus. The function of TARPs in the DG would appear to be the exclusive responsibility of the TARPγ8 isoform, which we show operates as an AMPAR-interacting protein (Fig. 6D). The inability of stg to express TARPγ2 results in expression of the GABAR α4β3γ2 subtype in the DG that would be predicted to confer unique GABAergic properties to the DG and impart the potential for relocalization of α4β3 subunits to inhibitory synapses at the apparent expense of δ-associated α4β3 subunits in extrasynaptic domains. Whether these GABAR rearrangements are adaptive responses to high-frequency excitatory oscillations from DG afferents has yet to be fully resolved. Nonetheless, this provides an intriguing system with which to study mechanisms that dictate GABAR expression, assembly, and targeting.

Footnotes

This work was funded by Wellcome Trust Grants 0543478 and 066204, Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council Grant BBS/B/09899, and Austrian Science Fund Grant P17203. H.L.P. was supported in part by Merck Sharp and Dohme, and P.S.D. was supported by the Institut de Recherches Servier. We thank Dr. Dane Chetkovich (Northwestern University, Chicago, IL) for TARPγ3, TARPγ4, and TARPγ8 cDNAs, and Andrew Crawford for Figure 1E and Simon Kaja (Departments of Neurology and Neurophysiology, Leiden University Medical Centre, Leiden, The Netherlands) for critical reading of this manuscript.

References

- Bredt DS, Nicoll RA (2003). AMPA receptor trafficking at excitatory synapses. Neuron 40:361–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chafetz RS, Nahm WK, Noebels JL (1995). Aberrant expression of neuropeptide Y in hippocampal mossy fibers in the absence of local cell injury following the onset of spike-wave synchronization. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 31:111–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Chetkovich DM, Petralia RS, Sweeney NT, Kawasaki Y, Wenthold RJ, Bredt DS, Nicoll RA (2000). Stargazin regulates synaptic targeting of AMPA receptors by two distinct mechanisms. Nature 408:936–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark M (1998). Sensitivity of the rat hippocampal GABAA receptor α4 subunit to electroshock seizures. Neurosci Lett 250:17–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmariah SB, Crumling MA, Parsons TD, Balice-Gordon RJ (2004). Postsynaptic TrkB-mediated signaling modulates excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitter receptor clustering at hippocampal synapses. J Neurosci 24:2380–2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K, Fukaya M, Qiao X, Sakimura K, Watanabe M, Kano M (1999). Impairment of AMPA receptor function in cerebellar granule cells of ataxic mutant mouse stargazer. J Neurosci 19:6027–6036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ives JH, Drewery DL, Thompson CL (2002). Differential cell surface expression of GABAA receptor α1, α6, β2 and β3 subunits in cultured mouse cerebellar granule cells–influence of cAMP-activated signalling. J Neurochem 80:317–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ives JH, Fung S, Tiwari P, Payne HL, Thompson CL (2004). Microtubule associated protein light chain 2 is a stargazin-AMPA receptor complex interacting protein, in vivo. J Biol Chem 279:31002–31009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic JN, Thomas P, Kittler JT, Smart TG, Moss SJ (2004). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor modulates fast synaptic inhibition by regulating GABAA receptor phosphorylation, activity, and cell-surface stability. J Neurosci 24:522–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korpi ER, Mihalek RM, Sinkkonen ST, Hauer B, Hevers W, Homanics GE, Sieghart W, Luddens H (2002). Altered receptor subtypes in the forebrain of GABAA receptor δ subunit-deficient mice: recruitment of γ2 subunits. Neuroscience 109:733–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama R, Yamada MK, Fujisawa S, Katoh-Semba R, Matsuki N, Ikegaya Y (2004). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor induces hyperexcitable reentrant circuits in the dentate gyrus. J Neurosci 24:7215–7224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leroy C, Poisbeau P, Keller AF, Nehlig A (2004). Pharmacological plasticity of GABAA receptors at dentate gyrus synapses in a rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J Physiol (Lond) 557:473–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letts VA, Felix R, Biddlecome GH, Arikkath J, Mahaffey CL, Valenzuela A, Bartlett FS II, Mori Y, Campbell KP, Frankel WN (1998). The mouse stargazer gene encodes a neuronal Ca2+-channel γ subunit. Nat Genet 19:340–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihalek RM, Banerjee PK, Korpi ER, Quinlan JJ, Firestone LL, Mi ZP, Lagenauer C, Tretter V, Sieghart W, Anagnostaras SG, Sage JR, Fanselow MS, Guidotti A, Spigelman I, Li Z, DeLorey TM, Olsen RW, Homanics GE (1999). Attenuated sensitivity to neuroactive steroids in γ-aminobutyrate type A receptor delta subunit knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:12905–12910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahm WK, Noebels JL (1998). Nonobligate role of early or sustained expression of immediate early gene proteins c-Fos, c-Jun and Zif/268 in hippocampal mossy fiber sprouting. J Neurosci 18:9245–9255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusser Z, Mody I (2002). Selective modulation of tonic and phasic inhibitions in dentate gyrus granule cells. J Neurophysiol 87:2624–2628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusser Z, Hajos N, Somogyi P, Mody I (1998). Increased number of synaptic GABAA receptors underlies potentiation at hippocampal inhibitory synapses. Nature 395:172–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Z, Huang CS, Stell BM, Mody I, Houser CR (2004). Altered expression of the δ subunit of the GABAA receptor in the mouse model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci 24:8629–8639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao X, Noebels JL (1993a). Developmental analysis of hippocampal mossy fiber outgrowth in a mutant mouse with inherited spike wave seizures. J Neurosci 13:4622–4635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao X, Noebels JL (1993b). Elevated BDNF mRNA expression in the hippocampus of an epileptic mutant mouse, stargazer. Soc Neurosci Abstr 19:1030. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao X, Hefti F, Knusel B, Noebels JL (1998). Selective failure of brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA expression in the cerebellum of stargazer, a mutant mouse with ataxia. J Neurosci 16:640–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouach N, Byrd K, Petralia RS, Elias GM, Adesnik H, Tomita S, Karimzadegan S, Kealey C, Bredt DS, Nicoll RA (2005). TARPγ8 controls hippocampal AMPA receptor number, distribution and synaptic plasticity. Nat Neurosci 8:1525–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Suzuki K, Yamazaki H, Nakanishi S (2005). A pivotal role of calcineurin signaling in development and maturation of postnatal cerebellar granule cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:5874–5879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieghart W, Ernst M (2005). Heterogeneity of GABAA receptors: revived interest in the development of subtype-selective drugs. Curr Med Chem 5:217–242. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp AH, Black JL III, Dubel SJ, Sundarraj S, Shen J-P, Yunker AMR, Copeland TD, McEnery MW (2001). Biochemical and anatomical evidence for specialized voltage-dependent calcium channel γ isoform expression in the epileptic and ataxic mouse, stargazer. Neuroscience 105:599–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperk G, Schwarzer C, Tsunashima K, Fuchs K, Sieghart W (1997). GABAA receptor subunits in the rat hippocampus. I. Immunocytochemical distribution of 13 subunits. Neuroscience 80:987–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stell BM, Brickley SG, Tang CY, Farrant M, Mody I (2003). Neuroactive steroids reduce neuronal excitability by selectively enhancing tonic inhibition mediated by δ subunit-containing GABAA receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:14439–14444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C, Sieghart W, Kapur J (2004). Distribution of α1, α4, γ2, and δ subunits of GABAA receptors in hippocampal granule cells. Brain Res 1029:207–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Sato M, Morishima Y, Nakanishi S (2005). Neuronal depolarization controls brain-derived neurotrophic factor-induced upregulation of NR2C NMDA receptor via calcineurin signaling. J Neurosci 25:9535–9543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CL, Jalilian Tehrani MH, Barnes EM Jr, Stephenson FA (1998). Decreased expression of GABAA receptor α6 and β3 subunits in stargazer mutant mice: a possible role for brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the regulation of cerebellar GABAA receptor expression? Mol Brain Res 60:282–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CL, Drewery DL, Atkins HD, Stephenson FA, Chazot PL (2002). Immunohistochemical localization of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor subunits in the adult murine hippocampal formation: evidence for a unique role of the NR2D subunit. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 102:55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita S, Chen L, Kawasaki Y, Petralia RS, Wenthold RJ, Nicoll RA, Bredt DS (2003). Functional studies and distribution define a family of transmembrane AMPA receptor regulatory proteins. J Cell Biol 161:805–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada MK, Nakanishi K, Ohba S, Nakamura T, Ikegaya Y, Nishiyama N, Matsuki N (2002). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor promotes the maturation of GABAergic mechanisms in cultured hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci 22:7580–7585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Mori M, Burgess DL, Noebels JL (2002). Mutations in high-voltage-activated calcium channel genes simulate low-voltage-activated currents in mouse thalamic relay neurons. J Neurosci 22:6362–6371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]