Abstract

Stargazer mice fail to express the γ2 isoform of transmembrane α-amino-3-hydroxyl-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionate (AMPA) receptor regulatory proteins that has been shown to be absolutely required for the trafficking and synaptic targeting of excitatory AMPA receptors in adult murine cerebellar granule cells. Here we show that 30 ± 6% fewer inhibitory γ-aminobutyric acid, type A (GABAA), receptors were expressed in adult stargazer cerebellum compared with controls because of a specific loss of GABAA receptor expression in the cerebellar granule cell layer. Radioligand binding assays allied to in situ immunogold-EM analysis and furosemide-sensitive tonic current estimates revealed that expression of the extrasynaptic (α6βxδ) α6-containing GABAA receptor were markedly and selectively reduced in stargazer. These observations were compatible with a marked reduction in expression of GABAA receptor α6, δ (mature cerebellar granule cell-specific proteins), and β3 subunit expression in stargazer. The subunit composition of the residual α6-containing GABAA receptors was unaffected by the stargazer mutation. However, we did find evidence of an ~4-fold up-regulation of α1βδ receptors that may compensate for the loss of α6-containing GABAA receptors. PCR analysis identified a dramatic reduction in the steady-state level of α6 mRNA, compatible with α6 being the primary target of the stargazer mutation-mediated GABAA receptor abnormalities. We propose that some aspects of assembly, trafficking, targeting, and/or expression of extrasynaptic α6-containing GABAA receptors in cerebellar granule cells are selectively regulated by AMPA receptor-mediated signaling.

The stargazer (stg) mutant mouse arose by virtue of a spontaneous viral transposon insertion into the stargazin gene (1). The mutation results in premature transcriptional arrest of the gene and complete ablation of its translation (2, 3). From postnatal day 14 onward stg mice display phenotypic consequences of the mutation that include head tossing (inner ear defect (1)), ataxia, impaired conditioned eyeblink reflex (cerebellar defects (4, 5)), and absence epilepsy (6). Stargazin is the γ2 isoform of the family of transmembrane AMPA6 receptor (AMPAR) regulatory proteins (TARPs) that are involved in AMPAR synaptic targeting and/or surface trafficking (7, 8). TARPγ2 is reported to be heavily expressed in the cerebellum (2, 9) where it is largely restricted to the cerebellar granule cells (CGCs), neurons that normally exclusively express the TARPγ2 isoform of TARPs. Consequently, mossy fiber-CGC synapses in stg are bereft of AMPARs and are subsequently electrically silent (7) leading to a CGC-specific deficit in brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression and signaling (4). Considerable research interest has recently focused on the ability of inhibitory GABAergic networks to adapt to changes on the strength of their excitatory inputs (10-13) and any accompanying changes in BDNF/TrkB signaling (14-16). Interestingly, GABAR expression in CGCs has been shown previously to be impaired in waggler mice, which also arbor a mutated stargazin gene (17). The GABAR channel kinetics recorded in adult waggler CGCs were comparable with those expressed in CGCs of juvenile control mice (18) implying that the waggler mutation resulted in developmental arrest of CGCs that included restriction of GABAR maturation to that expected in juvenile neurons. This appeared to correlate with our previous data that showed that expression of the GABAR α6 subunit and the BZ-IS subtype of GABARs, markers of mature CGCs (19-22), were down-regulated in stg cerebellum (23). Here we have extended these earlier studies by using a more appropriate background strain of mice and including a more extensive analysis of receptor expression thus revealing information about the full complement of GABARs predicted to be expressed in the cerebellum and to evaluate whether the abnormalities in GABAR expression are restricted to distinct cellular and subcellular domains. Here we also provide evidence that the effects of the stargazer mutation on GABAR expression are largely restricted to CGCs. Furthermore, we have revealed that it is the α6 subunit-containing GABAR subtypes that are selectively affected by the mutation, and these include not only the synaptic α6 subunit-containing GABAR subtypes (α6βxγ2 and α1α6βxγ2) but also the extrasynaptic, tonic inhibition-conferring α6βxδ receptors (10, 24, 25), the latter being responsible for eliciting >97% of GABAR-mediated inhibition in CGCs and thus pivotal to information transfer in the cerebellum (26). The abundance and distribution of the GABAR γ2 subunit and the number of receptors that it contributes to are largely unaffected, as is the developmental maturation profile of the BZ-S subtype of cerebellar GABARs. Thus, our data imply that AMPA receptor activity has selective effects on GABAR subtypes expressed in cerebellar granule cells that may underpin homeostatic GABAergic responses to neuronal excitability.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Hyperfilm, horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary anti-rabbit antibodies, and [3H]flunitrazepam were purchased from Amersham Biosciences. Vectastain Elite ABC immunohistochemistry kits were purchased from Vector Laboratories (Peterborough, UK). Horseradish peroxidase-linked anti-goat secondary antibody was obtained from Pierce. Mammalian cell protease inhibitor mixture was purchased from Sigma. [3H]Muscimol and [3H]Ro15-4513 were purchased from PerkinElmer Life Sciences. Flunitrazepam, Ro15-1788, and Ro15-4513 were gifts from Hoffmann-La Roche. RNAzol B was purchased from Biogenesis (Poole, Dorset, UK). Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase, recombinant RNasin ribonuclease inhibitor, dNTPs, and 100-bp DNA ladder were from Promega (Southampton, Hampshire, UK). Random primers and sequence-specific PCR primers were from Invitrogen. Taq polymerase and Taq polymerase buffer were from HT Biotechnology (Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, UK). All other materials were purchased from commercial sources.

Animals

Wild-type (C3B6Fe+; +/+), heterozygous (C3B6Fe+; +/stg), and homozygous stargazer mutant mice (C3B6Fe+; stg/stg) were obtained from heterozygous breeding pairs originally obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and maintained in the University of Durham vivarium on a 12-h light/dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum. Animal husbandry, breeding, and procedures performed during these experiments were conducted according to the Scientific Procedures Act 1986. We, in accordance with others (4, 27), have found no differences between wild-type and heterozygous mice in terms of their phenotype, behavior, or any of the molecular entities we have studied. We routinely use, therefore, a mixture of +/+ and +/stg mice brains in our control experiments. From this point forward we will refer to control derived tissue as +/+.

Radioligand Binding

Membranes prepared from control and stg cerebella were used for saturating binding assays using [3H]muscimol (1–77 nm) and [3H]Ro15-4513 (0.3125–40 nm) as described previously (23) and a single concentration of [3H]Ro15-4513 (20 nm) for zolpidem-mediated competitive displacement assays as described previously (11). Nonspecific [3H]muscimol binding was determined in the presence of GABA (100 μm). Nonspecific [3H]Ro15-4513 binding was determined in the presence of Ro15-1788 (10 μm). [3H]Ro15-4513 binding in the presence of flunitrazepam (10 μm) allowed an estimation of the proportion of total specific [3H]Ro15-4513-binding sites that were associated with either benzodiazepine full agonist-sensitive GABARs (BZ-SRs) or benzodiazepine full agonist-insensitive GABARs (BZ-ISRs). A minimum of eight radioligand concentrations was used for each saturation binding assay and performed at least in duplicate for each concentration of ligand used on 45–100 μg of protein/assay tube. Bound ligand was determined following rapid membrane filtration using a 24-sample Brandel Cell Harvester on polyethyleneimine (0.1% v/v)-treated GF/B filter paper. Statistical analysis of binding was performed using Graphpad Prism 3.0 software, and p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Ligand Autoradiography

Procedures were essentially as described previously (28) with minor modifications. Mice were anesthetized with a lethal dose of pentobarbitone prior to transcardiac pressure perfusion, first with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)/NaNO2 (0.1% w/v) for 3 min (10 ml/min) and then with ice-cold PBS/sucrose (10% w/v) for 10 min (10 ml/min). Brains were dissected and immediately frozen in isopentane (−40 °C) for 1 min. Brains were cryostat (Leica)-sectioned (−21 °C, 16 μm) in the horizontal plane and thawmounted onto polylysine-coated slides (BDH). Two control and two stg sections were thaw-mounted onto each slide thus enabling direct comparison of radiolabeling. Sections were airdried overnight, transferred to a desiccator, and stored at −20 °C until required.

Quantification of Receptor Autoradiographs

Autoradiographs and calibration standards were scanned at 1200 dpi using a flatbed scanner. Grayscale intensities were estimated using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda). Calibration curves were constructed for each ligand/exposure period using 3H standards, 0.1–109.4 nCi/mg (Amersham Biosciences) so grayscale intensity could be transformed into absolute radioactivity. Ten random subdomains of each cerebellar granule cell layer from a minimum of six comparable sections per mouse strain with a minimum of three mice per strain were used to yield an estimated mean intensity. Nonspecific binding values were subtracted from mean intensity values to resolve specific ligand binding. Statistical analysis was by Student’s t test, and p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR Amplification

The steady-state level of GABAR α6 and δ subunits mRNAs and β-actin mRNA in control and stg cerebella were determined by semi-quantitative RT-PCR, essentially as described previously (11) with the following modifications.

Total RNA was extracted from cerebella using RNAzol B and resuspended in diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water. The concentration and quality of the RNAs were determined by spectrophotometric analysis at 260 and 280 nm. Reverse transcription was performed in a total volume of 35 μl. Each reaction contained 1× Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase reaction buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 75 mm KCl, 3 mm MgCl2,10 mm dithiothreitol); 1.14 mm each of dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP; 40 units recombinant RNasin ribonuclease inhibitor and 3 μg of random hexamer. This was combined with total RNA of up to 1 μg and heated at 65 °C for 10 min. Reactions were rapidly chilled on ice before the addition of 400 units of Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase and incubation at 42 °C for 90 min.

Oligonucleotide primers for amplification of mouse β-actin mRNA were 5′-ATTGAACATGGCATTGTTAC-3′ and 5′-CGAAGTCTAGAGCAACATAG-3′. Primers for the amplification of mouse GABAR α6 and δ subunits mRNAs were as described previously (11, 29). Amplicons of 271 bp (α6), 334 bp (δ), and 460 bp (β-actin) were predicted and detected.

PCRs were performed in a total volume of 25 μl. Each reaction contained (final concentration) 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 9.0, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 50 mm KCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.4 mm dNTPs, 1 unit of Taq polymerase, and forward and reverse PCR primers. Five pmol of each primer was required for amplification of GABAR α6, and 25 pmol of each primer was required for amplification of β-actin and δ. Complementary DNA (2 μl), reversetranscribed from 1.0, 0.6, 0.4, or 0.2 μg of RNA, was amplified. Optimal PCR conditions were identified for each primer pair such that a single band of the expected size was produced, and the amount of product amplified was linear for at least three consecutive cDNA concentrations. The amplification protocol was as follows: 94 °C, 5 min followed by cycles of 94 °C for 45 s then 60 °C for 45 s (except 55 °C, 60 s for β-actin; 57 °C, 45 s for GABAR α6); 72 °C for 60 s (except 72 °C, 90 s for β-actin). The numbers of cycles were 24 for β-actin and 26 for GABAR α6 and δ subunits. Amplification products were resolved on 1.2% (w/v) agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide. Amplified products were sized according to their migration with respect to the bands on a 100-bp DNA ladder. Gels were then analyzed using the Quantity One (4.0.3) software for the GelDoc 2000 system (Bio-Rad). Control experiments included running the amplification procedure with each primer pair in the absence of cDNA, or running samples that had not been reverse-transcribed. Neither gave a final product. For each set of cDNAs, a β-actin value was determined. This value was used accordingly to regulate the values determined for the GABAR subunit amplifications to account for inaccuracy in the spectrophotometric measurements of RNA used in cDNA synthesis.

Antibodies

The generation and purification of anti-peptide GABAR subunit-specific antibodies directed against α1 (amino acid residues Cys1–14) (11), α6-(Cys1–15 (11)), β2-(351–405) (30), β3-(345–408) (31), γ2-(319–366) (32), and δ-(1–44) (28) have been described previously. Affinity-purified GABAR β2-(351–405), β3-(345–408), γ2-(319–366), and δ-(144) subunit-specific antibodies were supplied by Prof. Werner Sieghart, Medical University Vienna. Affinity-purified GABAR α1-(Cys1–14) subunit-specific antibodies used in immunohistochemical studies were provided by Professor F. A. Stephenson (School of Pharmacy, London, UK). Anti-NMDA receptor NR1 and NR2C/D subunit-specific antibodies were as described previously by us (33). Anti-β-actin antibody was purchased from Sigma.

SDS-PAGE and Western Blot Analysis

Control and stg mouse cerebella were homogenized individually using an Ultra-Turrax®, twice in a volume of 10 ml of homogenization buffer (10 mm Hepes, 1 mm EDTA, 300 mm sucrose) and once in 10 ml of washing buffer (10 mm Hepes, 1 mm EDTA), both containing one complete protease inhibitor mixture tablet per 50 ml of buffer (Roche Diagnostics), per cerebellum. Resulting pellets were finally resuspended in 6 ml of washing buffer.

SDS-PAGE was performed using the NuPAGE Western blotting system (Invitrogen), using 10% polyacrylamide gels in a discontinuous system. For estimation of the size of the proteins “MagicMarkTM XP Western Standards” (Invitrogen) were used in separate lanes. Equal amounts (containing 10 μg of protein) of the suspension were subjected to SDS-PAGE in different slots of the same gel. Proteins were blotted to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes and detected by antibodies to the following subunits: GABAR α1-(328–382); α6-(317–371), β2-(351–405), β3-(345–408), γ2-(319–366), or δ-(1–44) (30, 34). Secondary antibodies (F(ab’)2 fragments of goat anti-rabbit IgG, coupled to alkaline phosphatase (Axell, Westbury, NY), were visualized by the reaction of alkaline phosphatase with CDP-Star (Applied Biosystems, Bedford, MA). The chemiluminescent signal was quantified by densitometry after exposing the immunoblots to the Fluor-S multi-imager (Bio-Rad) and evaluated using the Quantity One quantitation software (Bio-Rad) and GraphPad Prism (Graph Pad Software Inc., San Diego). Quantification was performed by an independent investigator blind to the identity of the samples. The linear range of the detection system was established by measuring the antibody generated signal to a range of antigen concentrations. Under the experimental conditions used, the immunoreactivities were within the linear range, and this permitted a direct comparison of the amount of antigen per gel lane between samples (11, 35, 36). The amounts of individual GABAR subunits present in membranes from control and stargazer mice were compared in the same gel. Data were generated from several different gels per subunit and per mouse and expressed as means ± S.E. Student’s unpaired t test was used for comparing groups, and significance was set at p < 0.05.

To test for equal protein loading, in some experiments a monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody was included in the antibody solution, and the amounts of endogenous β-actin were quantitatively determined in a way analogous to GABAR subunits. Protein loading was comparable in different slots, and referring the data to the amounts of endogenous β-actin neither changed the results nor reduced variability.

Immunoprecipitation of GABARs

GABARs were solubilized from control and stg mouse cerebella using 6 ml of a deoxycholate buffer (0.5% deoxycholate, 0.05%, phosphatidylcholine, 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, 150 mm NaCl, 1 Complete Protease Inhibitor Mixture tablet (Roche Diagnostics) per 50 ml per cerebellum. The suspension was homogenized using an Ultra-Turrax® and subsequently by pressing the suspension through a set of needles with increasingly smaller diameters using a syringe, followed by incubation under intensive stirring for 60 min at 4 °C. After centrifugation at 150,000 × g for 45 min part of the clear supernatant (200–400 μg of protein) was used for subsequent immunoprecipitations either with 5 μg of anti-GABAR δ(1–44) or 20 μg of anti-GABAR α6-(317–371) antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Immunoprecipitin (20 μl) in IP-low buffer (50 μl) (containing 50 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, and Triton X-100 (0.2% v/v), supplemented with 5% (w/v) dry-milk powder) was subsequently added and incubated for 2 h at 4°C. Precipitate was pelleted by centrifugation at 2700 × g for 5 min, and the pellet was washed three times with 500 μl of IP-low buffer before being resuspended in 100 μl of SDS-PAGE sample buffer (NuPAGE Western blotting system; Invitrogen). Samples from control and stg were simultaneously subjected to SDS-PAGE, applying multiple samples of the same amount of protein from the same brain to one gel. Each Western blot was cut in strips, and two strips each from a gel containing control or stg material were probed simultaneously either with digoxigenized anti-α1-(1–9), anti-α6-(1–15), anti-γ2-(319–366), or anti-δ-(1–24) antibodies to reduce experimental variability. Primary antibodies were detected with anti-digoxigenin-alkaline phosphatase Fab fragments (Roche Diagnostics) and CDP-Star (Tropix, Bedford, MA). Immunoreactive proteins were visualized by chemiluminescence using the Fluor-S multi-imager (Bio-Rad) and were quantified using Quantity One (Bio-Rad) and GraphPad Prism (Graph Pad Software Inc., San Diego). The relative signal intensity of proteins stained with the different antibodies was compared within each gel and was referred to that of the precipitated subunit. The intensity ratios were then compared between receptors precipitated from control (+/+) and stg extracts.

Immunohistochemistry

Adult (2–6 months) control and stg mice were anesthetized with a lethal dose of pentobarbitone. The mice were transcardially perfused through the ascending aorta with ice-cold PBS, pH 7.4 containing NaNO2 (0.1% w/v) for 3 min at 10 ml/min. The perfusate was then exchanged for ice-cold 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer (0.1 m, pH 7.4), perfused for a further 20 min at 10 ml/min. Brains were dissected out and post-fixed in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer (0.1 m, pH 7.4, 4 °C) for 24 h. The brains were then transferred to PBS containing 10% (w/v) sucrose for 48 h, 4 °C, exchanging the PBS/sucrose every 12 h. Brains were frozen in isopentane (−70 °C) for 2 min and then cryostat-sectioned (30 μm) in the horizontal and sagittal planes. Sections were transferred to the wells of 24-well plates containing PBS/NaN3 (0.02% w/v). Free-floating sections were immunohistochemically stained by standard methods (33). Briefly, unreacted paraformaldehyde was quenched by incubation, 30 min, in PBS/glycine (0.2% w/v, pH 7.4). Nonspecific binding sites were blocked with 10% goat serum in PBS/Triton X-100 (0.2% v/v). Sections were then exposed to GABAR subunit-specific primary antibodies at optimized concentrations (0.5 μg/ml (α1, β2, β3, γ2), 0.06 μg/ml (α6); 0.25 μg/ml (δ)) overnight at 4 °C. Sections were then stained using the Vectastain ABC Elite kit with 3,3-diaminobenzidine (0.5 mg/ml), 0.02% (v/v) H2O2 in Tris-buffered saline, pH 7.2, as horseradish peroxidase substrate.

Quantitative Immunoelectron Microscopy

Brains were perfusion-fixed as described for immunohistochemistry with the following modifications. Brains were perfusion-fixed with either 8% paraformaldehyde in 0.2 m Hepes, pH 7.2 (Hepes buffer), or 4% paraformaldehyde, 0.1% glutaraldehyde in Hepes buffer or 0.5% glutaraldehyde in Hepes buffer. The data presented here were derived from 0.5% glutaraldehyde in Hepes buffer-fixed sections as these conditions offered the best compromise between immunogold signal and preservation of morphology. Brains were dissected out and stored in fixative. Cerebellar cortex from the vermis region was cut into 0.5-mm sized blocks. These were cryoprotected in 2.3 m sucrose, 20% (v/v) polyvinylpyrrolidone (40 kDa) in PBS, mounted on iron panel pins, and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Frozen tissue was sectioned with a diamond knife on a Leica ultracryomicrotome and mounted on pioloform/carbon-coated EM support grids. Immunogold labeling was as follows: grid-mounted sections were incubated for 5 min on drops of 0.5% (w/v) fish skin gelatin in PBS (PBS/gelatin; Sigma) and then for 5 min on 0.1 m ammonium chloride in PBS. Sections were then incubated in anti-GABAR α6-(Cys1–15) subunit-specific antibodies (2.13 μg/ml) in PBS/gelatin for 30 min, washed in PBS, and then incubated on protein A-Gold (8 nm particle size; prepared as described previously (37)). After final washes in PBS and distilled water, the sections were embedded and contrasted in methyl cellulose/uranyl acetate. Labeling was quantified using stereologic techniques to estimate the membrane profile length of each membrane compartment, including granular cell plasma membrane, dendrite membrane, and Golgi-granule cell synapses as described previously (38). Pictures were recorded at systematically placed locations with a random start at ×10,000 magnification on photographic film. Images were scanned at 1000 dpi, displayed in Adobe Photoshop 5.5, and overlaid with an electronically generated square lattice grid with spacing of 0.5 μm. Area of compartments was estimated from π/4 × I × d,in which I is the sum of intersections with relevant membrane profiles, and d is the grid spacing. Typical counts of intersection hits and gold in a control experiment were, respectively, 444 and 72 for granule cell plasma membrane, 165 and 44 for dendrite membrane, and 148 and 11 for Golgi-granule cell synapses.

Protein Determinations

Protein concentrations were determined according to the method of Lowry et al. (39) employing bovine serum albumin as standard for calibration.

Electrophysiology

33–57-Day-old male mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital (120 mg/kg, intraperitoneal) and decapitated. Brains were rapidly dissected out into ice-cold modified artificial CSF (aCSF) of the following composition (in mm): 248 sucrose, 3 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, and 10 glucose (saturated with 95% O2, 5% CO2). Sagittal slices of the cerebellum, 200 μm thick, were cut using a vibratome (VT1000S; Leica, Ora, Italy) and placed in a holding chamber at 35 °C in aCSF of the following composition (in mm): 124 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, 1 sodium ascorbate, 3 sodium pyruvate (bubbled with 95% O2, 5% CO2) for 30 min and then allowed to return to room temperature. Slices were incubated under these conditions for a further 30 min before recording began. Slices were placed in a custom-made recording chamber on the stage of a differential interference contrast microscope (E600FM DIC; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and perfused with room temperature (20–24 °C) aCSF containing 20 μm Na-CNQX and 10 μm D-AP5 at ~2 ml/min. Visually identified granule cells were patched with thick wall borosilicate electrodes (3-5 megohms) filled with the following solution (in mm): 120 CsCl, 10 Hepes, 10 EGTA, 5 QX-314 (2(triethylamino)-N-(2,6-dimethylphenyl) acetamine), 4 sodium phosphocreatine, 1 Na2ATP, 0.3 LiGTP, pH 7.35, with CsOH (held at −70 mV). Input conductance was measured using a 200-ms, 15–25-mV hyperpolarizing step. Cells were held for at least 5 min to allow the pipette solution to dialyze the cell and the series resistance to equilibrate over which time an inward current slowly developed (presumably as a result of increase [Cl−]i). The control phase of recording did not begin until the inward current reached equilibrium. If the series resistance increased above 30 megohms or changed by 10% during the course of a recording, the data from that cell were excluded from additional analysis. Series resistance was compensated to 80%. Data were filtered at 3 kHz and logged at 10 kHz (micro 1401; Cambridge Electronics Design, Cambridge, UK) to Spike 4 software. We used two-tailed, Mann-Whitney and Wilcoxon matched pairs test, and p < 0.05 was regarded as significant. Data are shown as median (25th percentile, 75th percentile). Furosemide and zolpidem were dissolved in Me2SO. Me2SO concentrations were 0.01% (v/v) in both control and drug aCSF.

RESULTS

Comparative Pharmacological Profile of Cerebellar GABARs Expressed in Control and stg Mice

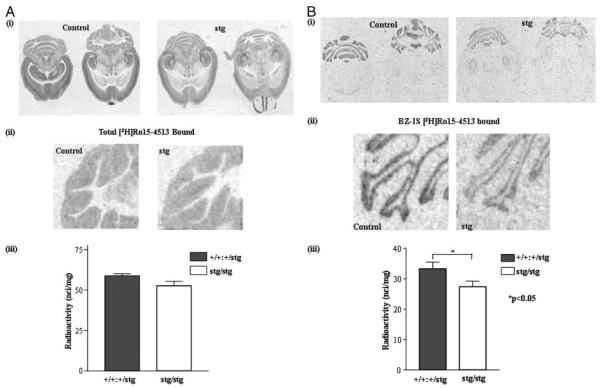

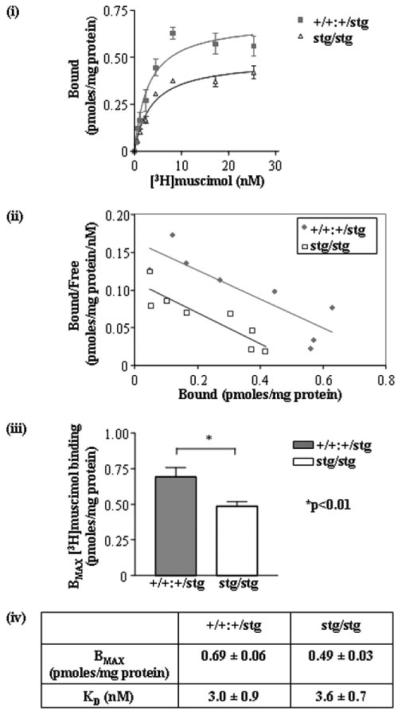

[3H]Muscimol Binding to Cerebellar Membrane Homogenates

The total number of GABARs expressed in the cerebella of adult control and stg mice was determined by [3H]muscimol binding to well washed, frozen-thawed cerebellar membrane homogenates. Muscimol binds to the principal and mutually exclusive γ2- and δ-containing subtypes of GABARs that constitute 98% of all GABARs expressed in the adult mouse cerebellum (34). Saturation binding studies revealed that the total number of specific [3H]muscimol binding sites (Bmax) was significantly lower, by 30 ± 6%, in stg compared with control indicating a change in the GABAR population (Fig. 1). The KD for muscimol binding was not significantly different between control and stg being 3.0 ± 0.9 and 3.6 ± 0.7 nm, respectively (Fig. 1), indicating no overall difference in receptor affinity for muscimol between the mouse strains.

FIGURE 1. [3H]Muscimol binding to control (+/+) and stargazer (stg) cerebellar membrane homogenates.

i, plot of [3H]muscimol (0.540 nm) saturation binding data to +/+ and stg cerebellar membranes (γ2 + δ-containing GABARs) from one of two assays conducted. ii, Rosenthal transformation of specific [3H]muscimol binding data to +/+ and stg cerebellar membrane homogenates shown in i. iii, bar graph demonstrates the difference in Bmax values calculated for [3H]muscimol binding to +/+ and stg cerebellar membranes. Results show a reduction to 70 ± 6% of +/+ levels in Bmax, i.e. total binding sites in stg cerebellar membranes. iv, table summarizing calculated and KD values for [3H]muscimol binding to +/+ and stg cerebellar membranes from two separate assays. Data are means ± S.E. for assays performed in triplicate for two separate preparations (n = 6). Membrane homogenates were prepared from n = 10 cerebella per mouse strain in each assay.

[3H]Muscimol Binding to Unfixed Cerebellar Membrane Sections (in Situ Autoradiography)

By in situ autoradiography, [3H]muscimol selectively highlights α6-containing GABARs in the cerebellum (α6βγ2, α1α6βγ2, α6βδ and α1α6βδ (28, 34, 40)). Unfixed brain sections were probed with a saturating dose (20 nm) of [3H]muscimol (Fig. 2). A dramatic reduction in specific muscimol binding in the CGC layer of stg relative to controls was observed (reduced by 46 ± 3%). The reduction in binding was uniform throughout all cerebellar lobules (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2. [3H]Muscimol binding to control (+/+) and stargazer (stg) adult mouse brain, in situ autoradiography.

i, in situ autoradiography of [3H]muscimol (α6βγ2, α1α6βγ2, α6βδ, and α1α6βδ GABARs) binding in +/+ and stg cerebella using a saturating concentration of [3H]muscimol (20 nm). Nonspecific binding was determined by competitive displacement of muscimol with GABA (100 μm). The signal obtained under these latter conditions was at the level of film background. Six sections from different horizontal planes are shown to demonstrate that the loss of receptor expression was consistent throughout the cerebellum. ii, magnified image of cerebellar lobules labeled with [3H]muscimol. iii, histogram illustrating the results of quantitative image analysis of grayscale intensities using image J software to determine the relative amounts of ligand bound in the cerebellar granule cell layers. A dramatic, significant reduction (by 46 ± 3%, p < 0.01) in [3H]muscimol binding in the cerebellar granule cell layer of stg was determined. Data shown are representative of at least three +/+ and three stg brains and a minimum of 10 sections per brain.

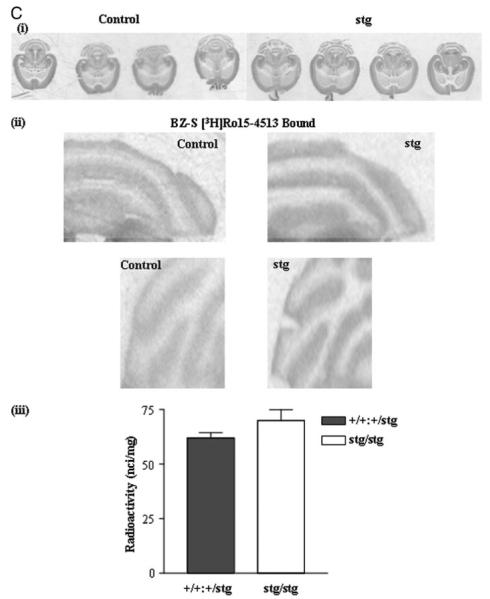

[3H]Ro15-4513-Binding Sites (γ2-Containing GABARs)

We had previously reported that expression of total specific [3H]Ro15-4513-binding sites in the cerebellum of stg was not significantly different from that found in control mice (23). However, these initial studies were conducted with C57Bl/J6 mice as background controls, whereas the stg mouse was bred onto a C3B6 line. Recent data have identified mouse strain-dependent differences in CGC properties. We repeated these earlier studies but using phenotypically normal, age-matched +/+ and +/stg littermates of stg/stg mutants as controls (C3B6Fe +/+ and +/stg). Furthermore, we extended these earlier studies to include an evaluation of the abundance and distribution of [3H]Ro15-4513-binding sites in stg mice using in situ autoradiography. The current results are largely compatible with those of our previous study (23).

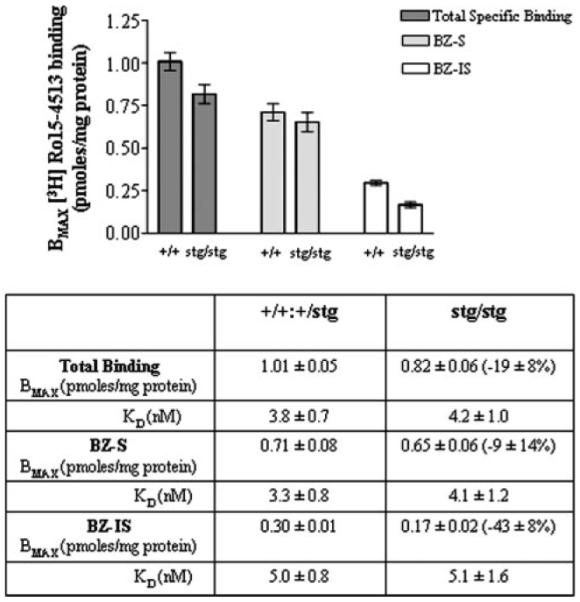

[3H]Ro15-4513 Binding to Cerebellar Membrane Homogenates

The total number of cerebellar [3H]Ro15-4513-binding sites (total number of γ2-containing GABARs) was only modestly affected by the mutation being reduced by 19 ± 9%, equivalent to a reduction of ~13 ± 6% of total GABARs (34), relative to control (Fig. 3). This reduction in [3H]Ro15-4513-binding sites was entirely accommodated by a selective reduction in expression of the BZ-IS subtype of γ2-containing GABARs, being reduced by 43 ± 12% (Fig. 3). The abundance of the BZ-S subtype of [3H]Ro15-4513-binding sites was not significantly affected by the stargazer mutation, Bmax being 0.71 ± 0.08 (control) and 0.65 ± 0.06 (stg) pmol/mg protein (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3. [3H]Ro15-4513 binding to control (+/+) and stargazer (stg) cerebellar membrane homogenates.

Full saturation [3H]Ro15-4513 binding curves were generated using +/+ and stg cerebellar membranes and a concentration range of 0.3–40 nm [3H]Ro15-4513. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of Ro15-1788 (10 μm). [3H]Ro15-4513 binding in the presence of flunitrazepam (10 μm), defined BZ-IS-binding sites, and hence benzodiazepine-sensitive (BZ-S) sites could be determined by subtraction of the BZ-IS-binding sites from total [3H]Ro15-4513 specific binding sites. The bar graph illustrates the difference in Bmax values calculated for [3H]Ro15-4513 binding to +/+ and stg membranes. Results show differences in Bmax for total specific binding (100 ± 5% and 81 ± 7%), BZ-S binding (100 ± 11% and 92 ± 9%), and BZ-IS binding (100 ± 3% and 57 ± 12%) in +/+ and stg membranes, respectively. The table summarizes the estimated Bmax and KD values for [3H]Ro15-4513 binding to +/+ and stg cerebellar membranes. Data are representative of the mean ± S.E. for assays conducted in triplicate on two separate membrane preparations per mouse strain (n = 6). Ten cerebella were used for each preparation per mouse strain.

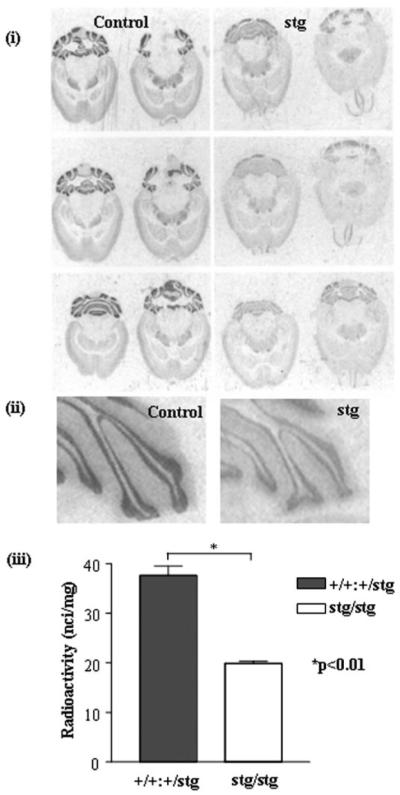

[3H]Ro15-4513 Binding to Unfixed Cerebellar Membrane Sections (in Situ Autoradiography)

When analyzed by in situ autoradiography, these deficits appeared restricted to the CGC layer. A comparable small reduction in total [3H]Ro15-4513-binding sites (by 10 ± 4%) was detected (Fig. 4A) as was a comparable significant reduction in BZ-IS [3H]Ro15-4513-binding sites (by 21 ± 7%) (Fig. 4B). These reductions were consistent across all cerebellar lobules and within individual lobules. Using [3H]flunitrazepam to highlight BZ-S receptors in situ, it was evident that BZ-S receptors were slightly more abundant in stg cerebellum than in controls (being 113 ± 6% of controls, Fig. 4C) (p > 0.05).

FIGURE 4. [3H] Ro15-4513 binding to control (+/+) and stargazer (stg) adult mouse brain; in situ autoradiography.

A, total [3H]Ro15-4513 binding. Panel i, in situ autoradiography of total [3H]Ro15-4513 binding (γ2-containing GABARs) to +/+ and stg cerebella using a near-saturating concentration of [3H]Ro15-4513 (20 nm). Nonspecific binding was determined by competitive displacement of Ro15-4513 with the benzodiazepine receptor antagonist, Ro15-1788 (10 μm). The signal obtained under these latter conditions was at the level of film background. Two representative comparable sections per mouse strain are shown. Panel ii, magnified image of cerebellar lobules labeled with [3H]Ro15-4513. Panel iii, histogram illustrating the results of quantitative image analysis of grayscale intensities using image J software to determine the relative amounts of ligand bound in the cerebellar granule cell layers. A small (10 ± 4%) but insignificant (p > 0.05) reduction in total [3H]Ro15-4513 binding in the cerebellar granule cell layer of stg was determined. Data shown are representative of at least three +/+ and three stg brains and a minimum of 10 sections per brain. B, BZ-IS [3H]Ro15-4513 binding. Panel i, in situ autoradiography of flunitrazepam (10 μm)-insensitive [3H]Ro15-4513 (BZ-ISR) binding (α6βγ2, α1α6βγ2 GABARs) in +/+ and stg cerebella using a saturating concentration of [3H]Ro15-4513 (20 nm). Nonspecific binding was determined by competitive displacement of Ro15-4513 with benzodiazepine receptor antagonist, Ro15-1788 (10 μm). The signal obtained under these conditions was at the level of film background. Panel ii, magnified image of cerebellar lobules following autoradiography to identify BZ-ISRs. Panel iii, histogram illustrating the results of quantitative image analysis of grayscale intensities using image J software to determine the relative amounts of radioligand bound in the cerebellar granule cell layer. A small but significant reduction (by 21 ± 7%; p < 0.05) in flunitrazepam-insensitive [3H]Ro15-4513 binding in the cerebellar granule cell layer of stg was determined. Data shown are representative of at least three +/+ and three stg brains and a minimum of 10 sections per brain. C, BZ-S [3H]flunitrazepam binding. Panel i, in situ autoradiography of [3H]flunitrazepam (BZ-SR) binding (e.g. α1βγ2 GABARs) in +/+ and stg cerebella using [3H]flunitrazepam (5 nm). Nonspecific binding was determined by competitive displacement of flunitrazepam with benzodiazepine receptor antagonist, Ro15-1788 (10 μm). The signal obtained under these conditions was at the level of film background. Panel ii, magnified image of cerebellar lobules following autoradiography to identify BZ-SRs. Panel iii, histogram illustrating the results of quantitative image analysis of grayscale intensities using image J software to determine the relative amounts of radioligand bound in the cerebellar granule cell layer. A small, nonsignificant increase (by 13 ± 6%; p > 0.05) in [3H]flunitrazepam binding in the cerebellum of stg was determined.

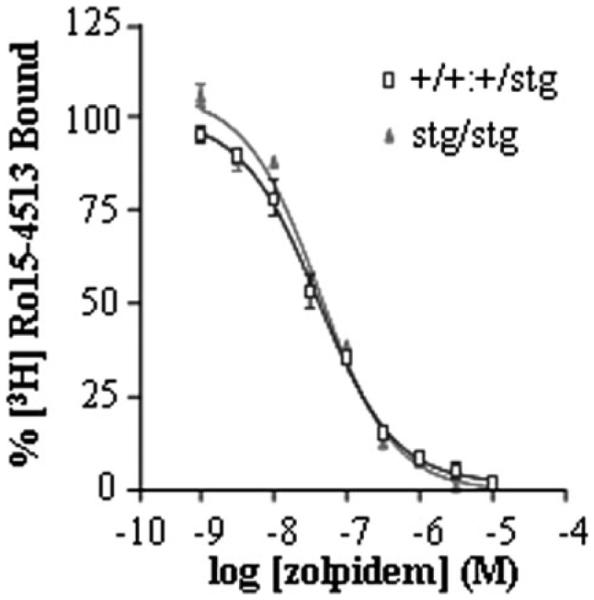

Is the Aberrant GABAR Expression Profile in stg Cerebellum Because of Arrested Development of This Brain Region?

Although the abundance of the BZ-S subtype of GABARs was not significantly affected by the stargazer mutation, we did not know whether the subunit composition of this subtype was different in stg compared with controls. It has been reported previously that the mutation of the stargazin gene in waggler mice resulted in arrested maturation of CGCs. The functional characteristics of GABARs expressed by CGCs of adult waggler mice were similar to those expressed in juvenile normal mice (7). One characteristic of the development of the cerebellum is the switch of the BZ-S subtype of GABARs from pharmacologically definable type II benzodiazepine-binding site (low affinity for the hypnotic agent zolpidem) to a type I benzodiazepine-binding site (high affinity for zolpidem). This is achieved by a developmental switch in the GABAR subunit expression profile preferring assembly of α2/α3βxγ2 receptors (type II BZ-SRs) in the juvenile cerebellum that transforms to assembly of receptors comprising largely α1βxγ2 subunits (type I BZ-SRs) in the adult cerebellum. Thus, we investigated whether BZ-S GABARs were immature in stg cerebellum. Zolpidem competitively displaced >98% of [3H]Ro15-4513 binding to BZ-S receptors expressed in both control and stg cerebellar membrane homogenates with IC50 values of 45 and 50 nm for control and stg, respectively, both compatible with high affinity type I BZ-SRs (Fig. 5). The displacement curve was predicative of binding to a single site. The IC50 for zolpidem displacement of [3H]Ro15-4513 binding to BZ-S receptors expressed in cerebellar membranes from juvenile (postnatal day 9) control mice was ~282 nm, which is compatible with the predominant expression of type II receptors in the cerebellum at this age (data not shown). Thus, our observations relating to GABAR expression cannot be attributed to a global effect of the mutation on cerebellar maturation. Furthermore, we tested whether the reported developmental switch in NMDA receptor subunit expression from NR2B, a characteristic of juvenile CGCs to NR2C, a marker of mature CGCs occurred. We found NR2B to be undetectable in adult stg cerebellar tissue but did detect NR2C,7 confirming a developmental switch in the maturity of stg CGCs.

FIGURE 5. Zolpidem displacement of [3H]Ro15-4513 binding to adult control (+/+) and stargazer (stg) cerebellar membrane homogenates.

Zolpidem (1 nm to 10 μm) was used to competitively displace BZ-S [3H]Ro15-4513 (5 nm) equilibrium binding from cerebellar membrane homogenates derived from adult +/+ and stg mice. [3H]Ro15-4513 binding displaced by flunitrazepam (10 μm) defined benzodiazepine-sensitive (BZ-S) sites. 100% binding was that obtained in the absence of competitive ligand.

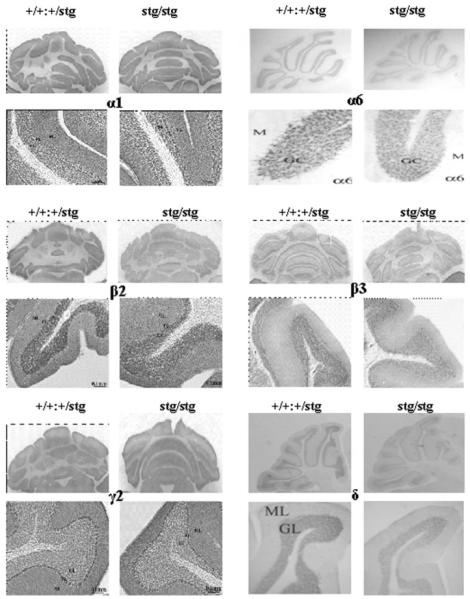

Immunohistochemical Mapping of Cerebellar GABAR Subunits in Control and stg Mice

We next investigated whether the changes in GABAR subtype expression were paralleled by changes in the distribution (immunohistochemistry, cerebellar sections) and/or abundance (quantitative immunoblotting, cerebellar membranes) of the principal GABAR subunits (α1, α6, β2, β3, γ2, δ) expected to be expressed in the mature cerebellum (41) of adult +/+ and stg mice. No overt changes in the cellular distribution were observed, although the intensity of staining (abundance) for GABAR α6, β2, β3, and δ subunits was clearly reduced in the CGC layer in stg mice relative to +/+ (Fig. 6). No consistent changes in the intensity of staining with GABAR α1 or γ2-specific antibodies were observed (Fig. 6). GABAR α6 and δ immunostaining was detected in all lobules of the stg cerebellum but was less intense compared with controls in both cases (Fig. 6) in accordance with the reduced expression of high affinity muscimol-binding sites by in situ autoradiography (Fig. 2) and BZ-IS receptors (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4B). Interestingly, the pattern of immunostaining of GABAR α6 in stg granule cells was different from that seen in the control mouse. The less intense punctate staining observed in stg cerebellar granule cells (Fig. 6) was similar to that found for synapse-targeted proteins such as the NMDA receptor NR2C subunit (33). Implying that the distribution of staining in control mouse cerebellum might reflect synaptic and extrasynaptic α6-containing receptors, whereas in stg only synaptic appeared to be highlighted, suggesting severely compromised expression of extrasynaptic α6-containing receptors, which include the α6βxδ subtype.

FIGURE 6. Immunohistochemical mapping of GABAR α1, α6, β2, β3, γ2, and δ subunits in the cerebellum of control (+/+) and stargazer (stg) mice.

Adult +/+ and stg mice were perfusion-fixed with paraformaldehyde, cryostat-sectioned, and immunostained as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Anti-GABAR subunit-specific antibodies were optimized for signal:noise ratio. Final concentrations used were α1 (0.5 μg/ml), α6 (0.06 μg/ml), β2 (0.5 μg/ml), β3 (0.5 μg/ml), γ2 (0.5 μg/ml), and δ (0.25 μg/ml). Each panel shows a low power image of an immunostained whole cerebellar section and a high power image cross-section of a typical cerebellar lobule from each mouse strain. These are representative results derived from a minimum of three +/+ and three stg brains. ML, molecular layer; GL, granular layer.

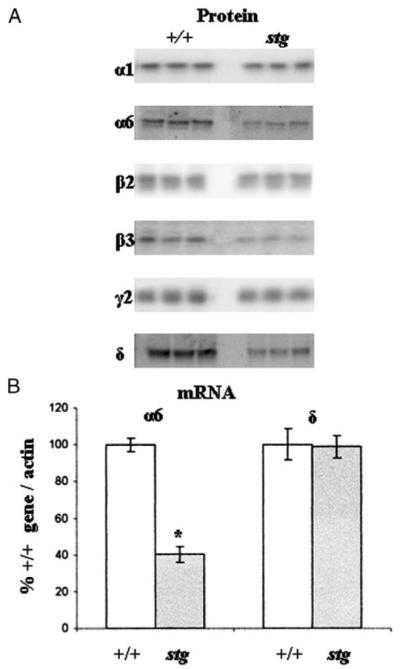

Changes in GABAR Composition in stg Cerebellum

Quantitative immunoblotting (Fig. 7 and Table 1) of cerebellar membranes from adult +/+ and stg using subunit-specific antibodies identified two pools of subunits, those whose expression level was dramatically affected by the mutation, e.g. α6 (49 ± 2% relative to control) and δ (52 ± 3% relative to control), whereas others, e.g. α1, were either modestly (85 ± 1% relative to control) or not significantly affected, e.g. γ2 (95 ± 4% relative to control). Furthermore, expression of NMDA receptor NR1 (129 ± 28%) and NR2D (101 ± 10%) subunits were refractory to the stargazer mutation. The quantitative estimations of the difference in GABAR subunit abundance in whole stg cerebella was paralleled by our qualitative estimations of their abundance in the CGC layer by immunohistochemistry where α6 and δ were clearly less prevalent in stg CGCs compared with controls, whereas α1 and γ2 appeared unaffected by the stg mutation (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 7.

A, Western blot analysis indicating changes in the abundance of GABAR subunits expressed in control (+/+) and stargazer (stg) cerebella. Immunoblots show the analysis of the six predominant GABAR subunits known to be present in cerebellar membranes of three +/+ and three stg mice. There was a large decrease in the intensity of the immunoreactive bands for the α6 (49 ± 2%) and δ (52 ± 3%) subunits and a weaker decrease in α1 (85 ± 1%), β2 (85 ± 2%), and β3 (64 ± 5%) subunits in stg cerebella p < 0.01. No significant changes in the intensity of the bands for γ2 (95 ± 4%) subunit were observed in stg cerebella p > 0.05. B, semi-quantitative RT-PCR amplification of cerebellar α6 and δ GABAR subunits mRNAs transcribed by control (+/+) and stargazer (stg) mice. Primer pairs specific for GABAR subunits α6 and δ cDNAs were designed as described previously (11, 29). In each case 1.0, 0.6, 0.4, 0.2, 0.1, and 0.05 μg of total RNA isolated from +/+ and stg cerebellum was reverse transcribed (RT) in a total volume of 35 μl of RT mix. 2 μl of each cDNA sample was removed for PCR amplification. Optimized amplification strategies were designed for each subunit cDNA. Following separation on a 1.2% (w/v) agarose gel and ethidium bromide staining, PCR products were visualized under UV light, and band image intensity was measured. The levels of the GABAR subunit mRNAs transcribed were normalized for β-actin mRNA transcription. Relative GABAR subunit mRNA levels found in +/+ and stg cerebellum are shown. Messenger RNA was isolated from a minimum of two +/+ and two stg mice. RT-PCR experiments were performed a minimum of three times each. Asterisk indicates significant difference (p < 0.05).

TABLE 1. Quantification of GABAR subunit proteins by Western blot analysis of cerebellar membranes derived from adult stargazer (stg) mouse cerebella relative to age-matched controls (+/+).

Equal amounts of cerebellar membrane protein from age-matched adult +/+ and stg mice were separated by SDS-PAGE and subjected to Western blot analysis, and immunoreactive band intensities were determined by ImageJ analysis as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Results were obtained from three to six +/+ and three to six stg mice that were investigated a total of three to five times and are expressed as percentages of the weighted average subunit level found in +/+ mice ± S.E. For statistical comparison unpaired Student’s t test was used. n indicates number of individual animals tested; NS indicates not significant.

| Protein | +/+ = 100% (mean ± S.E.) |

n |

stg % of +/+ (mean ± S.E.) |

n | Significance (p value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α1 | 100 ± 2 | 3 | 85 ± 1 | 3 | <0.001 |

| α6 | 100 ± 3 | 6 | 49 ± 2 | 6 | <0.0001 |

| β2 | 100 ± 3 | 3 | 85 ± 2 | 3 | <0.01 |

| β3 | 100 ± 3 | 3 | 64 ± 5 | 3 | <0.001 |

| γ2 | 100 ± 2 | 3 | 95 ± 4 | 3 | NS |

| δ | 100 ± 2 | 6 | 52 ± 3 | 6 | <0.0001 |

The dramatic loss of α6 and δ subunits in the cerebellum of stg as indicated by Western blot analysis could have been caused by a linear reduction of all α6- and δ-containing receptors without a change in the subunit composition of the remaining receptors. Alternatively, the subunit composition of the remaining receptors additionally could have become changed. To investigate these alternatives, δ or α6 subunit-specific GABAR subpopulations were selectively immunoprecipitated from the cerebellum of +/+ and stg mice using the appropriate subunit-specific antibodies. Changes in co-association of α6, α1, and γ2 with δ subunits or of α1, γ2, and δ with α6 subunits were then quantified by comparing the protein staining of the respective subunits in δ- or α6-containing receptors of +/+ and stg cerebellum.

δ-Purified Cerebellar GABARs

As indicated in Table 2, when we screened δ-purified cerebellar GABARs, γ2 subunit was not detected, in accordance with previous results (30, 34). The degree of association of α6 subunits with δ receptors was similar in +/+ (45 ± 16%) and stg (40 ± 13%) cerebellum, whereas that of α1 subunits was dramatically increased in stg cerebellum (117 ± 11%), suggesting a change in the subunit composition of δ receptors.

TABLE 2. Estimation of the relative α1, α6, γ2, and δ subunit composition of α6- and δ-containing GABARs in control (+/+) and stargazer (stg) cerebellum.

Cerebella from adult control (+/+) and stg mice were extracted with deoxycholate buffer. Equivalent amounts of extracted protein from each mouse were either incubated with δ or α6 antibodies, and the precipitated proteins were subjected to immunoblotting using digoxigenized α1, α6, γ2, or δ antibodies as probes. Immunoreactive proteins were identified by chemiluminescence, and intensity of protein staining was quantified using Fluor-S multi-imager (Bio-Rad). Since staining efficiency of individual subunit depends on the number of epitopes recognized by the antibodies as well as their avidity, intensity of protein staining cannot be used for direct quantification of subunits. A possible change in the subunit composition of the precipitated receptors can, however, be determined when the signal intensity of the co-precipitated subunit is referred to that of the precipitated subunit in +/+ and stargazer cerebellum. Data are from two experiments performed with two +/+ and two stg mice in duplicate. For statistical comparison unpaired Student’t t test was used (NS indicates not significant, not detected).

| δ IP | +/+, % of δ | stg, % of δ | Significance (p value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| δ | 100 ± 4 | 100 ± 2 | |

| α6 | 45 ± 16 | 40 ± 13 | NS |

| α1 | 43 ± 8 | 117 ± 11 | <0.05 |

| γ2 | NS |

| α6 IP | % of α6 | % of α6 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| α6 | 100 ± 3 | 100 ± 8 | |

| α1 | 151 ± 19 | 175 ± 12 | NS |

| γ2 | 114 ± 11 | 138 ± 16 | NS |

| δ | 141 ± 14 | 133 ± 13 | NS |

α6-Purified Cerebellar GABARs

The degree of association of α1 (175 ± 12%), γ2 (138 ± 16%), and δ (133 ± 13%) subunits with α6 subunits was not significantly changed in stg cerebellum, suggesting no change in the composition of the remaining α6 receptors.

Steady-state Levels of α6 but Not δ mRNA Are Affected by the Stargazer Mutation

Our data thus far indicated that the stargazer mutation selectively compromised α6- and δ-containing GABAR expression. This suggested that the α6 subunit is the primary cause of the receptor reduction in stg, because ~50% of the α6 subunits are associated with γ2 and ~50% with δ subunits and because both of these receptor types seem to be equally affected. If δ were the primary cause, we would have not expect a reduction in receptors composed of α6 and γ2 (BZ-IS subtype, Fig. 3 and 4B). We therefore used semi-quantitative RT-PCR to investigate whether the mRNAs for GABAR α6 and δ were affected by the mutation. Fig. 7B shows that the steadystate level of α6 mRNA found in stg CGCs was significantly reduced (lower by 60 ± 6%) relative to +/+ (Fig. 7B). The steady-state level of δ mRNA was not significantly different between +/+ and stg (Fig. 7B).

Are Synaptic α6-Containing GABARs (e.g. α6βxγ2) and/or Extrasynaptic α6-Containing GABARs (e.g. α6βxδ) Compromised in stg?

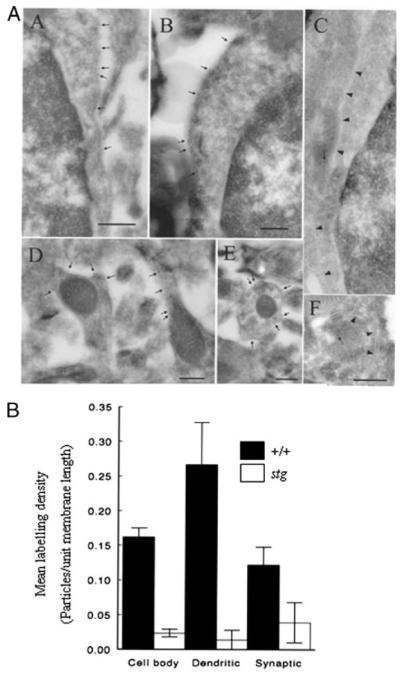

Based on our radioligand binding data, there are 30% fewer GABARs expressed in the stg cerebellum than in controls. Because 98% of GABARs expressed in the mouse cerebellum can be subdivided into two mutually exclusive subpopulations comprising those that are γ2-containing (~70% of total GABARs (34)) and those that are δ-containing (~28% of total GABARs (34)) and that we detected only ~13 ± 6% reduction of the γ2-containing subpopulation ([3H]Ro15-4513 binding, Fig. 3) of total GABARs, which was entirely attributable to down-regulation of the BZ-IS subtype (α6βxγ2-containing), implied that a sizeable pool of the α6βxδ-containing receptors was not expressed in stg. This extrapolation was supported by our in situ muscimol binding study (Fig. 2) and results of immunohistochemistry (Fig. 6) and immunoblotting (Table 1) using δ-specific antibodies. Because α6βxδ receptors are expressed exclusively at extrasynaptic sites of CGCs, we used our α6-specific antibody, which proved to be an effective probe for postembedding immunogold-cytochemistry on electron microscopic sections, to evaluate whether α6-containing receptors were compromised at CGC extrasynaptic and/or Golgi-CGC synaptic sites (Fig. 8). Clearly, extrasynaptic plasma membrane-targeted α6 subunit expression on granule cell bodies and dendrites was significantly down-regulated, being only 15 ± 3 and 5 ± 5% of control levels, respectively. Likewise, expression in Golgi-granule cell synapses was also significantly reduced to 32 ± 24% of control levels (Fig. 8).

FIGURE 8. Postembedding immunocytochemistry on electron microscopic sections.

A, immunolabeling of GABAR α6 subunit in the cerebellar granule cell layer of +/+ (panels A, B, D, and E) or stg (panels C and F) mouse cerebellum. The plasma membrane of granule cell bodies from +/+ mice (panels A and B) are labeled by gold particles (arrows), but the plasma membrane of stg mice (panel C; arrowheads) are not labeled, and the arrow in panel C marks a gold particle representing nonspecific-labeling of a mitochondrial profile. Plasma membrane of a dendrite (containing mitochondrial profiles) from +/+ mice is strongly labeled but those from stg mice are not labeled (arrow in panel F represents background labeling over a mitochondrial profile). Bars represent 500 nm in A and 250 nm in panels B–F. Two +/+ and two stg brains were fixed by each perfusion method. B, quantitative analysis of mean labeling density (number of gold particles/unit membrane length) of GABAR α6 immunoreactivity in various extrasynaptic (soma and dendrites) and synaptic subdomains of cerebellar granule cells from +/+ (closed boxes) and stg mice (open boxes) in situ. Data are representative of the mean ± S.E.

The Tonic GABAR-mediated Conductance Is Mediated by Smaller Fraction of α6 Containing GABARs in stg Mice

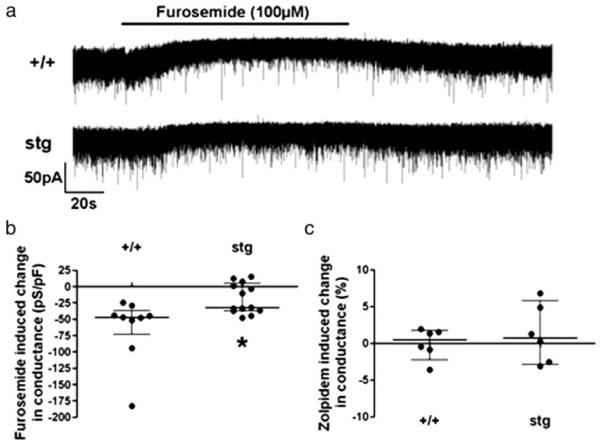

Given that α6βxδ GABARs likely mediated the tonic GABAR-mediated current in CGCs (10), we expected the loss of α6-containing GABARs in stg mice would result in a decrease in resting whole-cell conductance. Using whole-cell patch clamping in cerebellar brain slices, there was no difference in the membrane conductance of CGCs in stg and +/+ mice (+/+ 446 (interquartile range, 329, 560) pS/pF; stg 406 (330, 540) pS/pF; n = 29–33, p = 0.7, Mann Whitney test, data not shown). However, saturating concentrations of the α4/6 containing GABAR-selective antagonist furosemide (100 μm) (42, 43) produced a significantly smaller decrease in whole-cell conductance in stg mice (4% (−0.7, 8)) than their nonepileptic littermates (10% (8, 16); n = 9–11, p = 0.011, Mann Whitney test, Fig. 9, a and b), indicating that a smaller proportion of the tonic GABAR-mediated current is conducted by α6-containing GABARs. Zolpidem (3 μm) increased the decay time of spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents recorded in CGC (data not shown) but did not produce a significant change in whole-cell conductance in either stg (0.7% (−3, 6), n = 6, p = 0.6, Wilcoxon matched pairs test) or +/+ mice (0.4% (−2, 2), n = 6, p = 0.8, Wilcoxon matched pairs test Fig. 9c) indicating that the tonic GABAR-mediated current is not mediated by α1/2/3βxγ2-containing GABARs. The fact that there was no difference in resting whole-cell conductance makes it likely that stg mice develop a compensatory conductance to account for their lost tonic α6-containing GABAR-mediated current, in a similar fashion as has been shown in the CGCs of δ subunit knock-out mice (44).

FIGURE 9. The tonic GABAA receptor-mediated current in epileptic stargazer (stg) CGC is mediated by a smaller percentage of α6-containing GABARs.

a, representative traces showing the reduction in holding current induced by the application of the α6/α4 antagonist furosemide, and the different sensitivity in +/+ and stg mice. b, scatter plot showing that furosemide reduces whole-cell conductance significantly more in +/+ mice than stg mice (+/+, −47 (interquartile range, −73, −36) pS/pF; stg, −19 (−37, 4) pS/pF; n = 9–13, p = 0.011, Mann Whitney test). c, zolpidem produces no significant change in whole-cell conductance in either stg or +/+ mice (+/+, 0.4 (−2, 2) %, n = 6, p = 0.8; stg, 0.7, (−3, 6) %, n = 6, p = 0.6, Wilcoxon matched pairs test).

DISCUSSION

The stg mutation selectively and completely ablates expression of TARPγ2 (3), a member of the TARP family of AMPAR synaptic targeting and/or trafficking proteins (7-9). Consequently, mossy fiber-cerebellar granule cell (CGC) synapses are silent to mossy fiber glutamate release because AMPARs are no longer trafficked to the CGC surface nor targeted to this synapse. The CGCs are therefore functionally deafferentiated and have consequently been shown to fail to express BDNF, which is an activity-dependent process (4, 27).

GABAR Plasticity

Inhibitory GABAergic networks have been shown to adapt to changes in the strength of their excitatory inputs (10-13) and any accompanying changes in BDNF/TrkB signaling (14-16). In electrically silent, BDNF-deficient CGCs of stg, we previously reported that GABAR receptor α6 and β3 subunits and BZ-IS (α6βxγ2) receptors were down-regulated, whereas BZ-S receptors were unaffected (23). However, these previous studies failed to address whether the stargazer mutation affected the extrasynaptic α6βxδ GABARs that are exclusively expressed by CGCs and that provide tonic inhibitory current to these neurons. These receptors are extremely important as they have been estimated to mediate >97% of GABAR-mediated inhibition of CGCs and thus play a major role in regulating information flow-through the cerebellar cortex (26). Here we have extended these previous studies on stg mice, utilizing a more appropriate background control mouse strain, to investigate what effects the stargazer mutation has on all cerebellar GABAR subtypes and subunits expressed and further to elucidate the cellular context of these abnormalities, e.g. are they restricted to CGCs? If so, are these abnormalities evident in all CGCs in each cerebella lobule? Finally, we aimed to establish at what subcellular level these abnormalities are translated and to address whether the effects we report were because of specific effects on expression of unique GABAR subtype(s)/subunit(s) or an overall consequence of aberrant CGC maturation.

Cerebellar GABARs can be broadly subclassified as being either γ2-containing or δ-containing. These mutually exclusive GABAR subtypes constitute 98% of the total number of GABARs expressed in the adult mouse cerebellum (34). Taking account of the quantitative data of Poltl et al. (34), it is evident that 57.3% of all GABARs in the cerebellum of mice contain α6 subunits. Approximately half of these (29.2% of total GABARs) contain γ2 and half (28.1% of total GABARs) δ subunits. Because 28.9% of all GABARs in the cerebellum contain δ subunits, nearly all of the δ subunit-containing GABARs must also contain α6 subunits. Based on our Western blotting data (Fig. 7) stg CGCs express only ~50% of the number of α6 receptors expressed by +/+, and this would theoretically equate to a reduction of 28.7% of total GABARs expressed by +/+ (34), which is completely compatible with the 30 ± 6% reduction in muscimol binding we report here (Fig. 1). Two pieces of evidence indicate that stg CGCs express only ~50% as many δ-containing GABARs as +/+. First, our Western blotting data showed that δ-immunoreactivity in stg cerebellum was only 51.6 ± 2.9% of +/+ (Fig. 7). Second, muscimol autoradiography which highlights α6βxγ2 + α6βxδ GABARs in the cerebellum (28, 40) identified that stg CGCs express 46 ± 6% fewer α6βxγ2 + α6βxδ GABARs compared with +/+. Allied to the fact that stg CGCs express 43 ± 8% fewer BZ-IS-binding sites (specifically α6βγ2 receptors, Fig. 3), we can surmise that there are only ~50% of the α6βγ2 and ~50% of the α6βδ receptors expressed in stg CGCs compared with +/+. This fits with the 60% decrease in furosemide sensitivity in stg CGCs. Furthermore, we found that the relative proportion of α1, γ2, and δ subunits co-assembled with α6 isolated from +/+ and stg cerebella were identical (Table 2) indicating that although the number of α6-containing receptors expressed by stg CGCs is lower than in +/+ their subunit composition is identical. This is not the case however for the δ-containing receptors. The relative signal intensity of α6 subunits in δ-containing GABARs is similar in +/+ and stg, indicating that there is no significant change in the α6 subunit content of δ receptors. Control δ receptors comprise α6βδ, α1α6βδ, and α1βδ subtypes, which constitute 17.7, 10.4, and 0.8% of total GABAR numbers, respectively (34). Because we have established that the number of α6-containing receptors is lower by ~50% in stg but that the ratio of α6 subunit:δ subunit is unaltered indicates that the abundance of α6βδ and α1α6βδ subtypes is ~50% of that found in +/+ (equivalent to α6βδ and α1α6βδ subtypes comprising 8.9 and 5.2%, respectively, of total GABAR numbers expressed in +/+ cerebellum). However, the relative signal intensity of α1 subunits present in δ receptors is approximately double that found in stg (Table 2), indicating that the remaining δ receptors in stg contain twice as many α1 subunits. We can only assume that the abundance of (α1)2βδ GABARs is increased in stg CGCs. Because α1βδ receptors contain two α1 subunits, α1βδ receptors would need to constitute 3% of total GABARs expressed by +/+ CGCs to accommodate this observation, i.e. CGCs in stg would be expected to express ~4-fold as many α1βδ receptors as +/+ CGCs.

We have found that the stargazer mutation selectively influences expression of the α6 subunit-containing subtypes. The abundance of the BZ-S subtype of GABARs is essentially unaffected. This subtype was found to have type I-like pharmacology based on zolpidem displacement of [3H]Ro15-4513 binding to both +/+ and stg cerebellar membranes (Fig. 5), and thus is most likely representative of α1βxγ2 GABARs in both stg and +/+ cerebella. This latter observation also implies that stg CGCs undergo a normal developmental program of GABAR maturation that is partially characterized by the transformation from type II BZ-S receptors (juvenile cerebellar GABARs, α2/α3βγ2 receptors) to type I BZ-S receptors (adult cerebellar GABARs). This argues against the notion that CGCs are restrained in an immature state in stg (17). Hence, our data suggest that the stargazer mutation selectively affects expression of the CGC-specific GABAR subtypes, α6βxγ2, which has the potential to be targeted to and anchored at GABAergic synapses to respond in a neurosteroid-sensitive, zinc-insensitive manner to phasically released GABA (10, 18, 25, 26), and the extrasynaptically segregated α6βxδ subtype that responds to tonic and synaptic over-spill levels of GABA in a neurosteroid-insensitive, zinc-sensitive manner (10, 18, 25, 26). This was confirmed by in situ EM immunogold-labeling studies where CGC-specific α6-containing GABARs (α6βxδ + α6βxγ2) were found to be dramatically reduced at both extrasynaptic (largely α6βxδ) and synaptic (α6βxγ2) loci (Fig. 8). The reduction in α6 labeling of stg membranes by this route, however, was much more dramatic than expected from our other results and may be due to difficulties in extracting quantitative data from cell surface-clustered proteins whose accessibility, with relatively large reporter molecules such as gold particles, may be compromised if the fewer receptors expressed form smaller clusters or occupy more central aspects of the synapse. Clearly, the downstream consequences of the stargazer mutation modulate α6-containing receptor expression, selectively. Finally, we propose that aberrant expression of the α6 subunit is the primary cause of compromised GABAR expression in stg. Our rationale is based on the fact that ~50% fewer α6 subunits are expressed by stg CGCs, which translates into ~50% fewer α6βγ2 receptors and ~50% fewer α6βδ receptors, i.e. both of these receptor types seem to be equally affected. If compromised expression of the δ subunit were the primary cause, we would anticipate that there would be no effect on the number of α6βγ2 receptors. This posit is verified by our RT-PCR analysis that showed that the steady-state level of GABAR α6 subunit mRNA was ~50% of that determined in +/+, whereas the steady-state level of GABAR δ subunit mRNA was not significantly different from +/+ (Fig. 7B). This suggests that the impaired expression of both synaptic and extrasynaptic α6 subunit-containing GABARs is because of stargazer mutation-evoked reduction in the steady-state level expression of α6 subunit mRNA.

Thus, we have shown that the inability to express functional AMPARs at the mossy fiber-CGC synapse of stargazer mice (7) has severe deleterious effects on the GABAR-inhibitory potential of these neurons in vivo. Heynen et al. (36) showed that selectively blocking α6-containing GABARs with furosemide in rat cerebellar slices evoked a >2-fold increase in the gain of transmission of information from mossy fibers to granule cells. This would be perceived as a disadvantage because this would potentially increase the number of cerebellar granule cells that are simultaneously activated by specific mossy fiber afferent pathway inputs thus reducing the potential for motor program storage in the cerebellum. It would appear then that the GABAR-mediated inhibitory potential of CGCs is titrated according to the excitatory input these neurons experience, a phenomenon proposed by others in other neuronal networks (10, 12). We propose that expression and assembly of α6-containing GABARs is regulated either directly by AMPAR-mediated excitability of CGCs, e.g. depolarization-mediated regulation of α6 expression through a Ca2+-mediated signal transduction pathway has already been proposed (45) and verified by us,8 or indirectly as a downstream consequence of the loss of AMPAR activity, e.g. an inability to express BDNF (4, 5), and BDNF has been shown to regulate α6 gene transcription (46). We have found that TARPγ2 and AMPAR subunits e.g. GluR2, are expressed in maturing CGCs in vitro from +/+ mice prior to expression of both α6 and δ subunits and that expression of these subunits are regulated by AMPAR activity.8 Furthermore, we have shown previously that GABAR profiles expressed by CGCs in vitro were dramatically modified by culturing under polarized (5 mm KCl) or depolarized, electrically silent conditions (25 mm KCl) (11); in the latter α6 subunit mRNA steady-state level and protein expression were severely compromised implying that failure to express functional AMPARs and subsequent loss of electrical activity of CGCs in stg may play a part in the GABAR deficits observed in stg CGCs. Gault and Siegel (47, 48) identified that GABAR δ subunit mRNA was up-regulated in rat CGCs by a depolarization-dependent mechanism that involved Ca2+ influx through L-type voltage-gated calcium channels and/or NMDA receptors and subsequent calmodulin kinase activation. Down-regulation of GABAR δ subunit protein in the absence of AMPA receptor activity in stg CGCs, however, occurs in the absence of any change in its steady-state mRNA level. The GABAR α6 knock-out mouse also fails to express δ subunit protein in the cerebellum despite transcribing δ subunit mRNA to control level (28). This is thought to occur because the α6 subunit is the preferred receptor assembly partner in CGCs, in the absence of α6 subunit (α6 subunit knock-out mouse), or when its expression is compromised (stargazer mouse) the amount of available receptor partner is reduced, and the δ protein that fails to assemble into a receptor is then rapidly turned over. The apparent up-regulation of α1βδ receptors by stg CGCs appears to be insufficient to compensate for the loss of α6βδ receptors because δ expression (Western blots, see Fig. 7) is reduced. Where α1βδ receptors are trafficked/targeted and what role they play in inhibitory neurotransmission are currently unknown.

It is intriguing also to note that expression of α1 and γ2 subunits and the BZ-S subtype of GABARs in CGCs is largely unaffected by the inability of stg CGCs to express functional AMPARs. What functional role these receptors play in the CGCs and how their expression is regulated remains to be resolved. We are currently investigating how AMPAR activity regulates expression, assembly, and trafficking of α6-containing GABARs in CGCs.8

Acknowledgments

Technical help was provided by John James and Calum Thomson of the Centre for High Resolution Imaging and Processing at Dundee University.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by Grants 0543478 and 066204 (to C. L. T.) from the Wellcome Trust and Merck Sharp and Dohme Ltd. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

- AMPA

- α-amino-3-hydroxyl-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionate

- BZ-SR

- benzodiazepine agonist-sensitive Ro15-4513 receptor

- BZ-IS

- benzodiazepine-insensitive

- CGCs

- cerebellar granule cells

- GABAR

- γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor

- sIPSC

- spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic current

- TARP

- transmembrane AMPA receptor

- GABAA

- aminobutyric acid, type A

- AMPAR

- AMPA receptor

- RT

- reverse transcriptase

- BDNF

- brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- NMDA

- N-methyl-d-aspartic acid

- aCSF

- artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- pS

- picosiemen

- pF

- picofarad

REFERENCES

- 1.Letts VA, Felix R, Biddlecome GH, Arikkath J, Mahaffey CL, Valenzuela A, Bartlett FS, II, Mori Y, Campbell KP, Frankel WN. Nat. Genet. 1998;19:340–347. doi: 10.1038/1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharp AH, Black JL, III, Dubel SJ, Sundarraj S, Shen J-P, Yunker AMR, Copeland TD, McEnery MW. Neuroscience. 2001;105:599–617. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00220-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ives JH, Fung S, Tiwari P, Payne HL, Thompson CL. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:31002–31009. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402214200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qiao X, Hefti F, Knusel B, Noebels JL. J. Neurosci. 1998;16:640–648. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-00640.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qiao X, Chen L, Gao H, Bao S, Hefti F, Thompson RF, Knussel B. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:6990–6999. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-17-06990.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Pasquale E, Keegan KD, Noebels JL. J. Neurophysiol. 1997;77:621–631. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.2.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen L, Chetkovich DM, Petralia RS, Sweeney NT, Kawasaki Y, Wenthold RJ, Bredt DS, Nicoll RA. Nature. 2000;408:936–943. doi: 10.1038/35050030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rouach N, Byrd K, Petralia RS, Elias GM, Adesnik H, Tomita S, Karimzadegan S, Kealey C, Bredt DS, Nicoll RA. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:1525–1533. doi: 10.1038/nn1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomita S, Chen L, Kawasaki Y, Petralia RS, Wenthold RJ, Nicoll RA, Bredt DS. J. Cell Biol. 2003;161:805–816. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nusser Z, Sieghart W, Somogyi P. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:1693–1703. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-05-01693.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ives JH, Drewery DL, Thompson CL. Neuropharmacol. 2002;43:715–725. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leroy C, Poisbeau P, Keller AF, Nehlig A. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 2004;557:473–487. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.059246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peng Z, Huang CS, Stell BM, Mody I, Houser CR. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:8629–8639. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2877-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamada MK, Nakanishi K, Ohba S, Nakamura T, Ikegaya Y, Nishiyama N, Matsuki N. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:7580–7585. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-17-07580.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jovanovic JN, Thomas P, Kittler JT, Smart TG, Moss SJ. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:522–530. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3606-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elmariah SB, Crumling MA, Parsons TD, Balice-Gordon RJ. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:2380–2393. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4112-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen L, Bao S, Qiao X, Thompson RF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:12132–12137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tia S, Wang JF, Kotchabhakdi N, Vicini S. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:3630–3640. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-11-03630.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korpi ER, Uusi-Oukari M, Kaivola J. Neuroscience. 1993;53:483–488. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90212-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng T, Santi M-R, Bovolin P, Marlier LN, Grayson DR. Dev. Brain Res. 1993;75:91–103. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(93)90068-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson CL, Stephenson FA. J. Neurochem. 1994;62:2037–2044. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62052037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson CL, Pollard S, Stephenson FA. Neuropharmacol. 1996;35:1337–1346. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(96)00114-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson CL, Jalilian Tehrani M, Barnes EM, Jr., Stephenson FA. Mol. Brain Res. 1998;60:282–290. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00205-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brickley SG, Cull-Candy SG, Farrant M. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 1996;497:753–759. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brickley SG, Cull-Candy SG, Farrant M. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:2960–2973. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-08-02960.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamann M, Rossi DJ, Attwell D. Neuron. 2002;33:625–633. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00593-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hashimoto K, Fukaya M, Qiao X, Sakimura K, Watanabe M, Kano M. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:6027–6036. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-06027.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones A, Korpi ER, McKernan RM, Pelz R, Nusser Z, Makela R, Mellor JR, Pollard S, Bahn S, Stephenson FA, Randall AD, Sieghart W, Somogyi P, Smith AJH, Wisden W. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:1350–1362. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-04-01350.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Drescher DG, Green GE, Khan KM, Hajela K, Beisel KW, Morley BJ, Gupta AK. J. Neurochem. 1993;61:1167–1170. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jechlinger M, Pelz R, Tretter V, Klausberger T, Sieghart W. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:2449–2457. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-07-02449.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slany A, Zezula J, Tretter V, Sieghart W. Mol. Pharmacol. 1995;48:385–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tretter V, Ehya N, Fuchs K, Sieghart W. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:2728–2737. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-08-02728.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson CL, Drewery DL, Atkins HD, Stephenson FA, Chazot PL. Neurosci. Lett. 2000;283:85–88. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)00930-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poltl A, Hauer B, Fuchs K, Tretter V, Sieghart W. J. Neurochem. 2003;87:1444–1455. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pollenz RS. ECL Highlights. 1996;9:2–3. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heynen AJ, Quinlan EM, Bae DC, Bear MF. Neuron. 2000;28:527–536. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lucocq JM. Fine Structure Immunocytochemistry. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 1993. pp. 279–302. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lucocq JM. J. Anat. 1994;184:1–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. J. Biol. Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mihalek RM, Banerjee PK, Korpi ER, Quinlan JJ, Firestone LL, Mi Z-P, Lagenauer C, Tretter V, Sieghart W, Anagnostaras SG, Sage JR, Fanselow MS, Guidotti A, Spigelman I, Li Z, DeLorey TM, Olsen RW, Homanics GE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:12905–12910. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laurie DJ, Wisden W, Seeburg PH. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:4151–4172. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-11-04151.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Korpi ER, Kuner T, Seeburg PH, Luddens H. Mol. Pharmacol. 1995;47:283–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wafford KA, Thompson SA, Thomas D, Sikela J, Wilcox AS, Whiting PJ. Mol. Pharmacol. 1996;50:670–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brickley SG, Revilla V, Cull-Candy SG, Wisden W, Farrant M. Nature. 2001;409:88–92. doi: 10.1038/35051086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suzuki K, Sato M, Morishima Y, Nakanishi S. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:9535–9543. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2191-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bulleit RF, Hsieh T. Dev. Brain Res. 2000;119:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(99)00119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gault LM, Siegel RE. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:2391–2399. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-07-02391.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gault LM, Siegel RE. J. Neurochem. 1998;70:1907–1915. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70051907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]