Abstract

Toll-like receptor (TLR) proteins play key roles in immune responses against infection. Using TLR proteins, host can recognize the conserved molecular structures found in pathogens called pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). At the same time, some TLRs are able to detect specific host molecules, such as high-mobility group box protein 1 (HMGB1) and heat shock proteins (hsp), and lead to inflammatory responses. Thus, it has been suggested that TLRs are involved in the development of many pathogenic conditions. Recent advances in TLR-related research not only provide us with scientific information, but also show the therapeutic potential against diseases, such as autoimmune disease and cancer. In this mini review, we demonstrate how TLRs pathways could be involved in cancer development and their therapeutic application, and discuss recent patentable subjects, in particular, that are targeting this unique pathway.

Keywords: TLR, vaccination, breast cancer, bladder cancer, colon cancer, skin tumor, carcinoma, HPV

Introduction

Toll-like receptors, a mammalian homologue of the drosophila toll protein, are the best-characterized family of pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs), which sense foreign material, so called pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), derived from bacteria or virus. After activation of TLRs with their ligands either directly or with help of accessory proteins such as CD14 and MD2 (in case of TLR2/4), cells evoke inflammatory response, coordinate the immune system in the whole organism, and finally protect the host from spreading massive pathogen after infection 1. So far, mammalian TLRs consist of at least 13 members. Each TLR contains extracellular domain with leucine-rich repeats (LLR) motif, and these LLR comprise a binding domain for recognition of their respective pathogens. It has been implicated that their cytoplasmic domains play a role in transducing signaling to downstream pathways 2.

Members of TLRs are well conserved in both human and mouse, consisting of at least 11 members. Physiological ligands and functions of TLR1-9 have been well characterized and implicated in several cancers (Table 1). Ligands of each TLR are different; for example, TLR3, TLR7, TLR8, and TLR9 recognize nucleic acids derived from virus or bacteria whereas TLR2 recognizes bacterial lipoproteins, lipotechoic acid and fungal zymosan. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Gram negative bacteria cell wall is recognized by TLR4 and bacterial flagellin activates TLR5.TLRl1is present in mice, but not in human, and it has been known to recognize uropathogenic Escherichia coli 3, however, recent studies have identified a profilin-like protein from Toxoplasma gondiias a ligand of TLR11 4. No ligand has been identified for TLR10, 12 and 13.

Table 1.

TLR ligands and expression in various tumor cells and tissues.

| TLRs | Natural Ligand-origin | Expressing cancer cells and tissues | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| TLR1 | Triacyl Lipopeptides-Bacteria | Colon cancer | 47 |

| Soluble factor-Neisseria meningitidis | |||

| TLR2 | Lipoprotein-various pathogens | Colon cancer | 48 |

| Peptidoglycan-Gram+bacteria | Gastric cancer | 49 | |

| Lipoteichoic acid-Gram+bacteria | Hepatocellular carcinoma | 50 | |

| Zymosan-Fungi | |||

| Heat-shock protein 70-host | |||

| TLR3 | Double stand RNA-Virus | Breast cancer | 33 |

| Colon cancer | 47 | ||

| Melanoma | 51 | ||

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 50 | ||

| TLR4 | Lipopolysaccharide-Gram negative bacteria | Breast cancer | 52 |

| Envelope protein-MMTV | Colon cancer | 47 | |

| Oligosaccharides of hyaluronic acid-Host | Melanoma | 53 | |

| Heat-shock protein 60/70-Host | Gastric cancer | 54 | |

| Lung cancer | 10 | ||

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 50 | ||

| Ovarian cancer | 55 | ||

| TLR5 | Flagellin-Bacteria | Gastric cancer | 54 |

| Cervical squamous cell carcinomas | 56 | ||

| TLR6 | Diacyl lipoproteins-mycoplasma | Hepatocellular carcinoma | 50 |

| TLR7 | Single-strand RNA-virus | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | 57 |

| TLR8 | Single-strand RNA-virus | ||

| TLR9 | CpG-containing DNA-Bacteria and virus | Breast cancer | 58 |

| Gastric cancer | 54 | ||

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 50 | ||

| Cervical squamous cell carcinomas | 59 | ||

| Glioma | 60 | ||

| Prostate cancer | 61 |

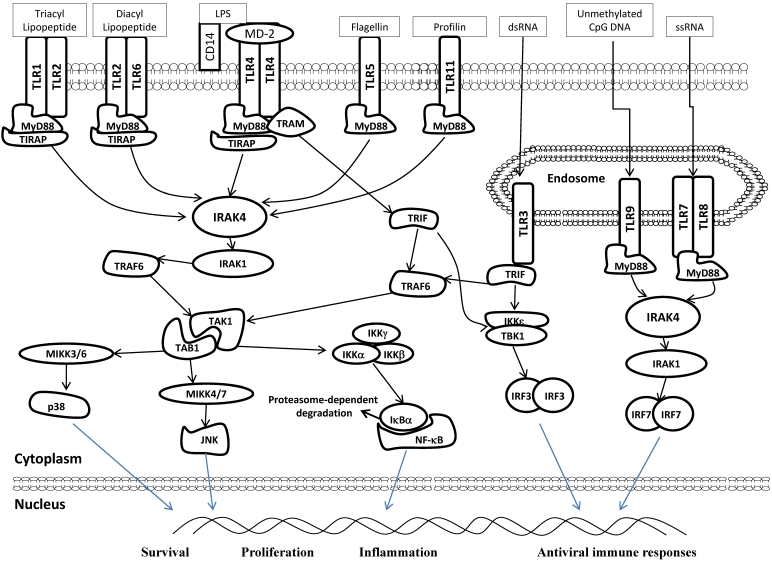

TLR signaling has been extensively investigated in the last several years 5-7.There are two major TLR pathways; one is mediated by MyD88 adaptor proteins, and the other is independent on MyD88. With exception of TLR3, all other TLRs commonly use MyD88 as the downstream adopter protein. Generally, upon activation with their individual ligands, activated TLRs recruit MyD88, leading to subsequent activation of the downstream targets, those including NF-κB (a nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells), mitogen-associated protein (MAP) kinase and interferon regulatory factors (IRFs). TLR3 and TLR4 induce NF-κB activation through the TIR domain-containing adaptor inducing IFN-β (TRIF) to activate downstream signaling. TLR-mediated activation of these molecules results in the production of antiviral type 1 interferon, proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (Fig 1). Recognition of PAMPs by TLR-expressing cells result in acute responses necessary to clear the pathogens in host. However, it has been also known that TLRs are involved in pathogenesis of autoimmune, chronic inflammatory and infectious diseases 8, 9. The accumulating evidences indicate that multiple chronic inflammatory diseases caused by infection are associated with TLRs, leading to cancer development 10-13, and that downstream molecules of TLR signaling pathway are often involved in the tumorigenic inflammatory response. Previously, one group of researchers found that MyD88 is required in a cell-autonomous fashion for RAS-MAPK signaling, leading to carcinogenesis 14. These results support an idea that MyD88 plays an important role not only in the pathway of TLR-mediated inflammation, but also in RAS-MAPK signaling, cell-cycle control, and cell transformation. NF-κB is also a well-known transcriptional factor for innate and adaptive immunity and plays a crucial role in inflammation against infectious molecules. Thus, NF-κB signaling pathway is likely a link between chronic inflammation and tumor development 15, which are supported by observation that constitutively active NF-κB is often found in a number of human malignancies 16, 17. Recent studies have directly demonstrated that NF-κB plays a pivotal role in TLRs-induced tumorigenesis when TLRs are activated by their ligand 15, 18.

Fig 1.

Diagram of TLR signaling pathways. TLRs localize to different subcellular compartments according to the molecular nature of the relevant ligands. TLR3, TLR7/8 and TLR9 are located at endolysosomal compartment and recognized dsRNA or ssRNA or unmethylated CpG DNA, respectively. In contrast, TLR2, TLR4, TLR5, and TLR11 are mainly displayed on plasma membrane and recognize indicated ligands. TLR2/1 heterodimers respond to triacyl lipopeptide, while TLR2/6 heterodimers recognize diacyl lipopeptide. CD14 and MD-2 are accessory proteins required for LPS/TLR4 ligation. Following ligation with their respective ligands, TLRs recruit downstream adaptor molecules, such as MyD88 (all TLRs except TLR3) and TRIF (TLR3 and TLR4), to activate IRAK4, TRAF6 and IKKε/TBK1. These sequentially activate signaling pathway of NF-κB, p38 MAPK and JNK, leading to a series of specific cellular responses related to cell survival, proliferation and inflammation. IRF3 and 7 are also activated downstream of TLR3, 7, 8 and 9. These signaling mediate the production of type 1 interferon and antiviral immune responses. MyD88:Myeloid differentiation primary-response protein 88, IRAK:IL-1R-associated kinase, TRAM:TRIF-related adaptor molecules, TIRAP:TIR domain containing adaptor protein, TRAF:TNF receptor-associated factor, TAB:TGF-β activated kinase 1/MAP3K7 binding protein, TAK:TGF--activated kinase,IKK:inhibitor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells kinase, MIKK:mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase.

Elevated expression of some TLRs has been reported in many tumor cells, tissues or tumor cell lines (Table 1). TLR4 is over-expressed in human and mouse inflammation-associated colorectal neoplasia, and TLR4-deficient mice are markedly protected from colon carcinogenesis, suggesting that expression of TLRs on tumor cells promotes tumor progression directly or indirectly 19. Therefore, determination of distribution or tumor-specific expression of TLR and response of those cells to TLR ligand in specific types of tumor should be informative in terms of strategy for cancer therapy.

As stated above, while expression of TLR often leads to tumor progression, TLR-mediated signaling also enhances the anti-cancer immunity and proteins in TLR signaling pathway are often considered as important targets for therapy against cancer 20. Because tumor antigens are sometimes tolerant in cancer patients, it is important for anti-cancer therapy to evoke effective immune response by antigen presenting cells (APCs), such as DCs, against antigens from tumor cells 10.

Recent development in TLR-related application for cancer therapy include detection of different levels of TLR protein and their activity in tumor tissues, potential strategy of treatment using TLR agonist to induce immune function of specific cells against tumor antigens, and development of new TLR agonist to bust anti-cancer effects. However, because some studies have described that tumorigenic conditions are promoted by TLR-associated signaling, TLR antagonists should be also considered as anti-cancer drug for specific cancer.

TLR2 & TLR4

It has been known that TLR expression in many tumors or cell lines was up-regulated 21. Also, in some tumor models, polymorphisms of TLR2 and 4 have been known to influence the risk of cancer, implicating that genetic variation in specific TLR may be associated with specific tumor progression 22.

TLR4 has been known as indicative molecule for detection of predisposition to a cancer 23, 24. It is now clear that anticancer effect by Bacillus Calmette-Guerin cell wall skeleton (BCG-CWS) is mediated by both TLR2 and TLR4 25. Recently, Lionel et al described in vitro method of assessing the sensitivity of a subject to a treatment of cancer, in particular to a chemotherapeutic treatment 26. This method involves detection of a mutated TLR4 nucleic acid as well as an abnormal TLR4 expression, being indicative of a resistance to treatment for cancer. They also claimed the method of determining a predisposition to a cancer or an increase probability of developing tumor in cancer patients. Their method comprised the detection of the presence of a mutated TLR4 sequence comprising a point mutation, preferably a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) leading to the substitution of asparagine by glycine at position 299 or of threonine by isoleucine at position 399. Finally, they describe a method for screening compounds useful for cancer therapy in a subject having a mutated TLR4 through determining the ability of a test compound to modulate the expression or activity of TLR4 or the relocalization to tumour cell plasma membrane of TLR4 ligands.

Recent patent by Baylin et al claimed very interesting diagnostic method for early detection of colon cancer 27. By comparing isogenic cells to cancer cells, they found a series of genes with hypermethlyated CpG island in cancer cells. Among these genes, CpG island in promoter of TLR2 was hypermethylated and we can predict TLR2 gene-silencing in primary cancer cells, suggesting TLR genes can be used to detect development of cancer, as well as pre-cancer.

Additionally, Hoon et al suggested some methods to detect the expression of TLR genes on melanoma cell 28. Based on information of expression, they claimed a method of modulating TLR gene expression using TLR agonists and a method of inhibiting melanoma cell migration using TLR antagonists. Therefore, we can diagnoses predisposing condition and predict development of cancer in patients by detection TLR2 & 4 expression and silencing in tissues through method as described above. These methods can provide parameters for exact diagnosis of tumor progress and information from above are important to develop new method for treatment against disease.

TLR3

As described above, double-stranded RNA is recognized by TLR3 in normal cells or cancer cells. Several chemically synthesized dsRNAs (polyA-U or polyI-C) have been used in preclinical study and previous data showed that these dsRNA could induce type 1 interferon production by blood mononuclear cells and that injection of these molecules enhances functions of the natural killer cells in vitro 29, 30. Also, type 1 interferon has a critical role in TLR3-mediated tumor suppression in mouse prostate tumors models 31. Furthermore, there are studies suggesting that TLR3 triggers apoptosis of human prostate cells and breast cancer cells 32, 33. Because apoptosis may be a potent mechanism of eliminating tumor cells, these previous results suggest that TLR3 or TLR3 ligands may be very useful tool for cancer therapy.

Recently, one group developed a method to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of dsRNA 34. They claimed methods of treating cancers using TLR3 agonist (polyA-U and polyI-C), by assessing the expression of a TLR3 receptor by cancer cells. Their invention is composed of two parts; one is the detection of TLR3 expression in cancer cells by specific TLR3 antibody (or fragment of antibody) and TLR3-specific primer (or probe). Secondary, they invented specific method to treat cancer patient who have TLR3 positive cancer cell or tissue. They showed that overexpression of TLR3 in tumor cells are observed in 10% of samples and these TLR3 positive breast cancer were found to well respond to polyA-U or polyI-C compared to TLR3 negative cells. Thus, these patients could benefit from the TLR3 agonist administration.

TLR5

TLR5 recognizes flagellin and is mainly expressed on antigen presenting cells (APCs), such as monocytes and DCs. Upon ligand-TLR5 interaction, flagellin evokes a series of immunomodulatory response in these cells 35, 36. Therefore, flagellin has been used as adjuvant that is effective in inducing innate immune response by APCs against tumor antigens 37. In this patent, they found that flagellin can inhibit tolerance on tumor antigens after administration in combination with tolerogenic tumor antigens. This effect of flagellin may be due to induction of IL-12 from APCs, while keeping IL-10 levels low. They used flagellin-expressing cell and tumor cell as an adjuvant, wherein all cells have been lethally irradiated. Recently, one group designed and tested a series of engineered flagellin derivates for NF-κB activation in vitro 38. They showed that most potent NF-κB activator, designated CBLB502, have the radioprotective effect in mouse model. The injection of CBLB502 before lethal dose of total-body γ-irradiation (IR) protected mice from both gastrointestinal and hematopoietic acute radiation syndromes, and led to improved survival. In contrast to normal tissues, this TLR5 ligand didn't change the radiosensitivity of mouse tumor, implying that TLR5 ligand may be valuable adjuvants for cancer radiotherapy and relatively safe protector for normal cells against high dose-radiation during IR. Although flagellin-elicited radioprotection required the TLR signaling adaptor MyD88, as well as TLR5 39, the underlying mechanism remains unclear.

TLR7 & TLR8

Imidazoquinoline compounds are well-known TLR7/8 agonists with strong local activity for innate immunity in viral infection and cancer. Synthetic imidazoquinoline compounds have been used as a potent adjuvant for eliciting T-cell responses to intracellular pathogens and model protein antigens 40. For example, AldaraTM (3M; imiquimod) is formulated as a cream for the treatment of superficial basal cell carcinoma, HPV infection 41. Attenuated mycobacterial antigen has been known as good candidate to set up therapy against HPV-related disease including cancer, but treatment for patients remains unsatisfactory in its efficacy and side effects.

Romagne et al have invented new TLR7 agonists and they have set up the method useful for treating a carcinoma (e.g. Bladder cancer) or viral infection 42. They synthesized new imidazoquinoline compounds and screened to find strong gamma delta T cell activator. Because gamma delta T cell is an important T cell subtype for innate immunity against cancers, they described immunization with mycobacterium antigen when used in combination therapy with TLR7 could be more effective than when used only antigen. Therefore, they claimed this method is effective some diseases, such as a bladder cancer, a skin tumor or an HPV infection.

TLR9

As described above, unmethylated CpG oligonucleotides are generally detected by TLR9, leading to DC activation for innate and adaptive immunity. Because tumor can escape from immune surveillance system by interfering DC function or by failing to provide the necessary activation signals 43, Vicari et al have invented method for the modulation of the immune response through the manipulation of DCs using combined treatment with CpG oligodeoxynucleotides (CpG ODNs) and IL-10 antagonists 44. IL-10 secreted from tumor cells has been well known as strong regulator of DC function 45. Indeed, IL-10 induces T cell unresponsiveness and down-regulates innate immunity against tumor through the inhibition of IL-12 production 46. Furthermore, combined administration of an IL-10 antagonist and a TLR9 agonist is one of candidates for cancer treatment. Therefore, their invention provides a method of treatment against cancer comprising administering to a patient with a series of a tumor-derived DC inhibitory factor antagonist (e.g. IL-10 signaling blocker) in combination with CpG ODNs as TLR9 agonist.

Current and Future Developments

TLRs have been implicated as a family of proteins which are involved in induction of innate immune response against microbial insult from surrounding, such as bacteria and virus. Today, a research between innate immunity and cancer is drawing a lot of attention from investigators, and this study actually provides critical information for development of therapeutic strategies against cancer. Recent studies and patents showed TLR expression profile could be one of guidelines for diagnosis of specific cancer. Using TLR agonist or antagonist in combination with antigen isolated from tumor, we can anticipate increasing effect of vaccination and evoking specific innate immunity against cancer. Although TLR can mediate host innate immune system, over-expression of TLRs has been paradoxically found in many tumor cases. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that TLR-mediated signaling promotes tumor growth, and escape of tumor cells from host immune system has been observed in some cancer models. These studies and observation strongly suggest that biological outcomes induced by high levels of the protein are determined by both inter- and intra-cellular environment. Although recent issues have continuously claimed that specific TLR or signaling molecules in TLR pathway are involved in pathogenesis of cancers, choices of use of either agonist or antagonist for TLR in the context of therapy could not be decided immediately. The study of TLRs is still in early stage, so we need to explore more detailed function of each TLR in different types of cancer. Without that information, one would not be able to develop therapeutic strategies using TLR pathway.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the members of the Ouchi Lab for discussion. Supported by NIH/NCI CA79892, NIH/NCI CA90631 and Susan G. Komen Foundation (T.O.).

Abbreviations

- TLRs

Toll-like receptors

- PRRs

pattern-recognition receptors

- PAMPs

pathogen-associated molecular patterns

- LLR

extracelluar leucine-rich repeats

- NF-κB

nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells

- MAP

mitogen-associated protein

- IRFs

interferon regulatory factors

- TRIF

TIR domain-containing adaptor inducing IFN-β

- DCs

dendritic cells

- BCG-CWS

Bacillus Calmette-Guerin cell wall skeleton

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- dsRNA

double-strand RNA

- APCs

antigen presenting cells

- CpG-ODN

CpG oligodeoxynucleotide.

References

- 1.Takeda K, Akira S. Toll-like receptors in innate immunity. International immunology. 2005;17:1–14. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nature reviews. 2004;4:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang D, Zhang G, Hayden MS. et al. A toll-like receptor that prevents infection by uropathogenic bacteria. Science. 2004;303:1522–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1094351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plattner F, Yarovinsky F, Romero S. et al. Toxoplasma profilin is essential for host cell invasion and TLR11-dependent induction of an interleukin-12 response. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takeda K, Akira S. TLR signaling pathways. Semin Immunol. 2004;16:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moynagh PN. TLR signalling and activation of IRFs: revisiting old friends from the NF-kappaB pathway. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:469–76. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamamoto M, Akira S. TIR domain-containing adaptors regulate TLR signaling pathways. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2005;560:1–9. doi: 10.1007/0-387-24180-9_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liew FY, Xu D, Brint EK, O'Neill LA. Negative regulation of toll-like receptor-mediated immune responses. Nature reviews. 2005;5:446–58. doi: 10.1038/nri1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cook DN, Pisetsky DS, Schwartz DA. Toll-like receptors in the pathogenesis of human disease. Nature immunology. 2004;5:975–9. doi: 10.1038/ni1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He W, Liu Q, Wang L, Chen W, Li N, Cao X. TLR4 signaling promotes immune escape of human lung cancer cells by inducing immunosuppressive cytokines and apoptosis resistance. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:2850–9. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balkwill F, Coussens LM. Cancer: an inflammatory link. Nature. 2004;431:405–6. doi: 10.1038/431405a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ernst PB, Takaishi H, Crowe SE. Helicobacter pylori infection as a model for gastrointestinal immunity and chronic inflammatory diseases. Digestive diseases (Basel, Switzerland) 2001;19:104–11. doi: 10.1159/000050663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Q, Withoff S, Verma IM. Inflammation-associated cancer: NF-kappaB is the lynchpin. Trends in immunology. 2005;26:318–25. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coste I, Le Corf K, Kfoury A. et al. Dual function of MyD88 in RAS signaling and inflammation, leading to mouse and human cell transformation. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3663–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI42771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pikarsky E, Porat RM, Stein I. et al. NF-kappaB functions as a tumour promoter in inflammation-associated cancer. Nature. 2004;431:461–6. doi: 10.1038/nature02924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palayoor ST, Youmell MY, Calderwood SK, Coleman CN, Price BD. Constitutive activation of IkappaB kinase alpha and NF-kappaB in prostate cancer cells is inhibited by ibuprofen. Oncogene. 1999;18:7389–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffin JD. Leukemia stem cells and constitutive activation of NF-kappaB. Blood. 2001;98:2291. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.8.2291a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ditsworth D, Zong WX. NF-kappaB: key mediator of inflammation-associated cancer. Cancer biology & therapy. 2004;3:1214–6. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.12.1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukata M, Chen A, Vamadevan AS. et al. Toll-like receptor-4 promotes the development of colitis-associated colorectal tumors. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1869–81. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolska A, Lech-Maranda E, Robak T. Toll-like receptors and their role in carcinogenesis and anti-tumor treatment. Cellular & molecular biology letters. 2009;14:248–72. doi: 10.2478/s11658-008-0048-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu L, Chen S. Toll-like receptors expressed in tumor cells: targets for therapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57:1271–8. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0459-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Omar EM, Ng MT, Hold GL. Polymorphisms in Toll-like receptor genes and risk of cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:244–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nihon-yanagi Y, Park Y, Ooshiro M. et al. [Expression of toll-like receptor 4 in colorectal cancer] Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2008;35:2247–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gatti G, Quintar AA, Andreani V. et al. Expression of Toll-like receptor 4 in the prostate gland and its association with the severity of prostate cancer. Prostate. 2009;69:1387–97. doi: 10.1002/pros.20984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsuji S, Matsumoto M, Takeuchi O. et al. Maturation of human dendritic cells by cell wall skeleton of Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin: involvement of toll-like receptors. Infection and immunity. 2000;68:6883–90. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.12.6883-6890.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lionel A, Guido K, Laurence Z. Toll like receptor 4 dysfunctions and the biological applications thereof. WO Patent. 2008:WO2008009693. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baylin SB, Criekinge W, Schuebel K.E, Cope L, Suzuki H, Herman J.G. Early detection and prognosis of colon cancers. US Patent application. 2008:20080085867. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoon DSB, Goto Y. Functional toll-like receptors (TLR) on melanocytes and melanoma cells and uses thereof. US Patent application. 2009:20090011418. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng YS, Xu F. Anti-cancer function of polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010 doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.12.13450. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheadle EJ, Jackson AM. Bugs as drugs for cancer. Immunology. 2002;107:10–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01498.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chin AI, Miyahira AK, Covarrubias A. et al. Toll-like receptor 3-mediated suppression of TRAMP prostate cancer shows the critical role of type I interferons in tumor immune surveillance. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2595–603. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paone A, Starace D, Galli R. et al. Toll-like receptor 3 triggers apoptosis of human prostate cancer cells through a PKC-alpha-dependent mechanism. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1334–42. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salaun B, Coste I, Rissoan MC, Lebecque SJ, Renno T. TLR3 can directly trigger apoptosis in human cancer cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:4894–901. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.4894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andre F, Zitvogel L, Sabourin J. Treatment of cancer using TLR3 agonists. US Patent. 2008:7378249. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayashi F, Smith KD, Ozinsky A. et al. The innate immune response to bacterial flagellin is mediated by Toll-like receptor 5. Nature. 2001;410:1099–103. doi: 10.1038/35074106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Means TK, Hayashi F, Smith KD, Aderem A, Luster AD. The Toll-like receptor 5 stimulus bacterial flagellin induces maturation and chemokine production in human dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:5165–75. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sotomayor EM, Suarez I. Flagellin-based adjuvants and vaccines. US Patent. 2008:7404963. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burdelya LG, Krivokrysenko VI, Tallant TC. et al. An agonist of toll-like receptor 5 has radioprotective activity in mouse and primate models. Science. 2008;320:226–30. doi: 10.1126/science.1154986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vijay-Kumar M, Aitken JD, Sanders CJ. et al. Flagellin treatment protects against chemicals, bacteria, viruses, and radiation. J Immunol. 2008;180:8280–5. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.12.8280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Othoro C, Johnston D, Lee R, Soverow J, Bystryn JC, Nardin E. Enhanced immunogenicity of Plasmodium falciparum peptide vaccines using a topical adjuvant containing a potent synthetic Toll-like receptor 7 agonist, imiquimod. Infection and immunity. 2009;77:739–48. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00974-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bong AB, Bonnekoh B, Franke I, Schon MP, Ulrich J, Gollnick H. Imiquimod, a topical immune response modifier, in the treatment of cutaneous metastases of malignant melanoma. Dermatology. 2002;205:135–8. doi: 10.1159/000063904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Romagne F, Tiollier J. Composition and method for the treatment of carcinoma. US Patent application. 2007:20070134273. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caux C, Ait-Yahia S, Chemin K. et al. Dendritic cell biology and regulation of dendritic cell trafficking by chemokines. Springer seminars in immunopathology. 2000;22:345–69. doi: 10.1007/s002810000053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vicari A, Caux C. Methods for treating cancer. US Patent application. 2009:20090087440. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fortsch D, Rollinghoff M, Stenger S. IL-10 converts human dendritic cells into macrophage-like cells with increased antibacterial activity against virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 2000;165:978–87. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hishii M, Nitta T, Ishida H. et al. Human glioma-derived interleukin-10 inhibits antitumor immune responses in vitro. Neurosurgery. 1995;37:1160–6. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199512000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Furrie E, Macfarlane S, Thomson G, Macfarlane GT. Toll-like receptors-2, -3 and -4 expression patterns on human colon and their regulation by mucosal-associated bacteria. Immunology. 2005;115:565–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02200.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoshioka T, Morimoto Y, Iwagaki H. et al. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide induces transforming growth factor beta and hepatocyte growth factor through toll-like receptor 2 in cultured human colon cancer cells. The Journal of international medical research. 2001;29:409–20. doi: 10.1177/147323000102900505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chang YJ, Wu MS, Lin JT. et al. Induction of cyclooxygenase-2 overexpression in human gastric epithelial cells by Helicobacter pylori involves TLR2/TLR9 and c-Src-dependent nuclear factor-kappaB activation. Molecular pharmacology. 2004;66:1465–77. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.005199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nishimura M, Naito S. Tissue-specific mRNA expression profiles of human toll-like receptors and related genes. Biological & pharmaceutical bulletin. 2005;28:886–92. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salaun B, Lebecque S, Matikainen S, Rimoldi D, Romero P. Toll-like receptor 3 expressed by melanoma cells as a target for therapy? Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4565–74. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harmey JH, Bucana CD, Lu W. et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced metastatic growth is associated with increased angiogenesis, vascular permeability and tumor cell invasion. International journal of cancer. 2002;101:415–22. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Molteni M, Marabella D, Orlandi C, Rossetti C. Melanoma cell lines are responsive in vitro to lipopolysaccharide and express TLR-4. Cancer letters. 2006;235:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schmausser B, Andrulis M, Endrich S, Muller-Hermelink HK, Eck M. Toll-like receptors TLR4, TLR5 and TLR9 on gastric carcinoma cells: an implication for interaction with Helicobacter pylori. Int J Med Microbiol. 2005;295:179–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kelly MG, Alvero AB, Chen R. et al. TLR-4 signaling promotes tumor growth and paclitaxel chemoresistance in ovarian cancer. Cancer research. 2006;66:3859–68. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim WY, Lee JW, Choi JJ. et al. Increased expression of Toll-like receptor 5 during progression of cervical neoplasia. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18:300–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Koski GK, Czerniecki BJ. Combining innate immunity with radiation therapy for cancer treatment. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Merrell MA, Ilvesaro JM, Lehtonen N. et al. Toll-like receptor 9 agonists promote cellular invasion by increasing matrix metalloproteinase activity. Mol Cancer Res. 2006;4:437–47. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee JW, Choi JJ, Seo ES. et al. Increased toll-like receptor 9 expression in cervical neoplasia. Molecular carcinogenesis. 2007;46:941–7. doi: 10.1002/mc.20325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.El Andaloussi A, Sonabend AM, Han Y, Lesniak MS. Stimulation of TLR9 with CpG ODN enhances apoptosis of glioma and prolongs the survival of mice with experimental brain tumors. Glia. 2006;54:526–35. doi: 10.1002/glia.20401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ilvesaro JM, Merrell MA, Swain TM. et al. Toll like receptor-9 agonists stimulate prostate cancer invasion in vitro. The Prostate. 2007;67:774–81. doi: 10.1002/pros.20562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]