Abstract

Arterial occlusive disease (AOD) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality through the developed world, which creates a significant need for effective therapies to halt disease progression. Despite success of animal and small-scale human therapeutic arteriogenesis studies, this promising concept for treating AOD has yielded largely disappointing results in large-scale clinical trials. One reason for this lack of successful translation is that endogenous arteriogenesis is highly dependent on a poorly understood sequence of events and interactions between bone marrow derived cells (BMCs) and vascular cells, which makes designing effective therapies difficult. We contend that the process follows a complex, ordered sequence of events with multiple, specific BMC populations recruited at specific times and locations. Here we present the evidence suggesting roles for multiple BMC populations from neutrophils and mast cells to progenitor cells and propose how and where these cell populations fit within the sequence of events during arteriogenesis. Disruptions in these various BMC populations can impair the arteriogenesis process in patterns that characterize specific patient populations. We propose that an improved understanding of how arteriogenesis functions as a system can reveal individual BMC populations and functions that can be targeted for overcoming particular impairments in collateral vessel development.

Keywords: arteriogenesis, leukocytes, bone marrow-derived cells, collateral vessels, recruitment sequence

INTRODUCTION

Arterial occlusive disease is already the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the developed world with as much as 20% of the aged population having asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease [79]. Moreover, the spread of Western lifestyle will only increase the disease prevalence in the coming decades. Since the 18th century, it has been known that there is a pre-existing network of bridging collateral arteries capable of compensating for major arterial occlusion [133]. With growth, these collateral vessels can provide alternate routes for blood flow around occluded arteries, preventing ischemic injury in downstream tissues. This observation and numerous subsequent studies over the last 40 years have raised the promise of therapeutically driving the process of collateral vessel growth for the treatment of a variety of arterial occlusive diseases. However, many of the large-scale therapeutic arteriogenesis clinical trials have yielded disappointing results in humans. This is despite the promising initial animal studies and pilot human studies (see reviews [62,65,115,118]. One of the key lessons from these failures is that, to develop a more effective therapy, we need to improve our basic understanding of the coordinated process of arteriogenesis [65,115,118].

The arteriogenic process is a highly orchestrated process involving the recruitment and proliferation of numerous cells types and the reorganization of the extracellular matrix, all of which are coordinated through a temporal pattern of cytokine, chemokine, growth factor, and protease expression. It is not surprising, therefore, that the application of single growth factors or therapeutic agents, irrespective of the specific mechanism and sequence they contribute to the arteriogenesis pathway, have not been therapeutically successful. One promising avenue of targeted treatment that may help recapitulate the coordinated arteriogenic process is the use of bone marrow derived cells to aid the growth of collateral vessels.

Since 1976 [91], it has been known that developing collateral vessels are prominently invested with bone marrow derived cells in a perivascular position. Subsequent study has shown these cells to be essential in coordinating the complex sequence of events necessary in driving collateral vessel growth [62]. However, initial clinical trials targeting BMC activation and mobilization (e.g. GM-CSF [100,116] and G-CSF [54,87,134]) have faired little better than single growth factor trials. Part of the reason for the lack of success may arise from not having considered patients’ impairments in the arteriogenic pathway [65] and/or how the cell types and methods used fit into the arteriogenic process. Given the interconnected nature of the arteriogenic pathway, impairments in any number of steps in the process can result in the same downstream results of insufficient collateral growth. Further, understanding the time-course of interactions of BMCs and vascular cells can highlight the processes occurring during the different phases of arteriogenesis and provide insight into how a proposed therapy might function within the system of pathways that drive collateral vessel growth. Moreover, understanding the temporal pattern of various populations of BMC accumulation may provide a means of identifying specific cell populations that can be used to target specific phases of arteriogenesis. Therefore, in this article, we will discuss the studies that have begun to elucidate the roles of BMCs in coordinating collateral vessel growth, the questions left unanswered, and how understanding the timing of how cells that coordinate the arteriogenic process may benefit the development of future therapeutic arteriogenesis efforts. First, we will outline the process and phases of arteriogenesis. Second, we will discuss the BMC populations involved during the arteriogenic process and the spatial and temporal interactions of BMCs with each other and vascular cells. Lastly, we will discuss how impairments could arise in any number of these pathways and the potential implications of using a view that encompasses the system of responses in arteriogenesis when designing future therapeutic strategies.

SEQUENCE OF ARTERIOGENESIS

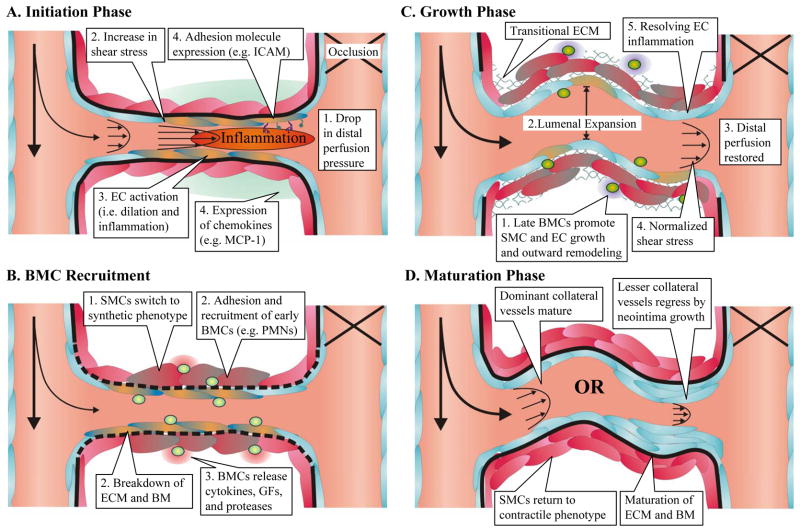

By first examining the overall process of arteriogenesis, we can begin to see the spatial and temporal complexity and the overlap of cellular and molecular systems that abound throughout the process. Overall, the sequence of arteriogenesis can be divided into three phases: initiation, growth, and maturation (Figure 1). Each phase involves the interplay of physical forces, leukocyte recruitment, extracellular matrix remodeling, and numerous growth and signaling cascades.

Figure 1.

The stages of arteriogenesis can be broken down into three phases (initiation, growth, and maturation). A) The drop in perfusion pressure distal to an occlusion causes increased flow through pre-existing collateral arteries. The increased shear stress triggers an inflammatory response in endothelial cells (ECs, blue, activation indicated by orange) initiating bone marrow derived cell (BMC) recruitment through expression of adhesion molecules and chemokines. B) During the initiation phase, the recruitment of early BMCs (light green) such as neutrophils (PMNs) aid the breakdown of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and basement membrane (BM). Paracrine and autocrine signaling through cytokines and growth factors (GFs) leads to smooth muscle cell (SMC) differentiation into a synthetic phenotype (indicated by grey) to allow for migration, proliferation, and the creation of a transitional matrix. C) Later arriving BMCs (dark green), such as monocytes, further stimulate SMC and EC proliferation and outward growth through paracrine support and matrix remodeling during the growth phase. This leads to lumenal expansion and vessel lengthening in a tortuous pattern, characteristic of growing collateral vessels. As lumenal diameter increases, resistance decreases, distal perfusion is restored, and shear stress begins to normalize. This leads to the resolution of endothelial cell inflammation. D) As inflammation decreases, BMCs disappear and proliferation wanes. Collateral vessels then undergo one of two paths. Vessels with the least resistance supply the most blood flow and mature into the dominant collaterals. Small collateral vessels that cannot maintain sufficient hemodynamic stimulus undergo neointimal hyperplasia and eventual regression.

Initiation by Physical Forces

Numerous studies have now identified changes in the physical forces experienced by endothelial cells to be a major initial stimulus in triggering collateral vessel growth (see review [40]). In response to the occlusion of a major artery, such as caused by an atherosclerotic plaque in a pathological state or an acute ligation in an experimental model, the vascular network downstream of the occlusion experiences a drop in pressure. This distal drop in pressure creates a steep pressure gradient that drives flow along any smaller, pre-existing bridging arteries that circumvent the occlusion. The resulting increase of flow along these collateral vessels is partially able to resupply the downstream tissue, but due to the increased length of the vascular path and reduced radius, the resistance to flow is much greater. This higher resistance network of pre-existing collateral vessels results in a sustained low perfusion pressure distal to the occlusion site and maintains the steep pressure gradient along the collateral pathways. This distal under-perfusion remains until the network has remodeled its structure to minimize resistance. The viscous force of the increased blood flow along these initial bridging arteries creates a shear stress at the wall that endothelial cells can sense, triggering a cascade of events initiating the arteriogenic process. The decreased perfusion pressure in the distal tissues, however, provides the additional vascular remodeling stimulus of ischemia, especially in the form of angiogenesis driven by HIF1α stabilization. Therefore, upon occlusion, the redistribution of resistance and pressure gradients throughout the network provides the stimulus for driving arteriogenesis in collateral vessels and angiogenesis in the downstream ischemic tissue.

However, the locations of these driving stimuli do not always spatially coincide, and these stimuli evolve over time as the network remodels. Several groups have shown that in the most common experimental model for studying collateral growth (i.e. femoral arterial ligation), the angiogenic stimulus of hypoxia is not present in the primary tissues where collateral growth is occurring [28,69,124]. As the arteriogenic process progresses, multiple parallel collateral vessels undergo lumenal expansion, which decreases overall network resistance and restores the driving perfusion pressure to the distal tissues. The lumenal expansion returns collateral vessel shear stress to a stable value, which allows for vessel maturation. When shear stress does not return to “normal,” collateral vessels will continue to remodel and expand as is seen in a shunt model of collateral growth [29,84,112]. Conversely, as the collateral network remodels and network resistance decreases, distal perfusion pressure returns to normal. The stimulus for angiogenesis reverses, and capillary density returns to normal [46]. It is important to note that the remodeling of collaterals has the greatest impact on overall network resistance and not the remodeling of capillaries in the distal ischemic tissue [56,67,113]. Additionally, it is important to consider that changes in shear stress and ischemia are not mutually exclusive stimuli and are likely to both contribute to collateral growth [126]. Ischemia may play a particularly prominent role in coronary collateral growth, where ischemia is in close proximity to developing collateral vessels [126]. Moreover, even when ischemia and collateral growth are greatly separated, such as in the hindlimb ischemia model, distal ischemia appears able to affect upstream collateral growth through systemic mobilization of BMCs [37]. However, the development of a mature collateral network is the primary means of reestablishing perfusion and changing shear stress stimuli throughout the vascular network, which dictates both the initiation and maturation of collateral vessel growth.

Propagation of Growth Process by Inflammation

The activation of the collateral vessel endothelium by a change in shear stress induces an inflammatory response that initiates and sustains the collateral growth process. In vivo and in vitro studies have shown that such a transient increase in shear stress induces the expression of a wide array of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules [69,96]. Of particular importance is the shear stress-mediated upregulation and surface expression of adhesion molecules such as selectins, ICAM, and VCAM along the lumenal surface of collateral vessels [96]. These adhesions proteins are known to be critical to inducing collateral growth primarily through the recruitment of leukocytes, such that removal or neutralization of these adhesion molecules abrogates arteriogenesis [50]. Similarly, the upregulation of a variety of chemokines along collateral vessels (e.g. MCP-1), induces the recruitment of specific bone marrow-derived cell (BMC) populations that aid in the remodeling process (see review [101]). Additionally, the inflammatory signaling cascades induce the differentiation of collateral artery smooth muscle cells from a contractile phenotype to a synthetic phenotype, allowing for the subsequent growth phase and remodeling of the vessel wall extracellular matrix [96]. Overall, the process results in the activation of intrinsic vascular cells that initiate the remodeling process leading to the accumulation of BMCs, whether in a model of coronary collateral growth [122] or hindlimb ischemia [96].

Once activated, these cells begin the growth process, which requires the coordination of numerous events to arrive at lumenal expansion of collateral vessels. Initially, the existing basement membrane components, such as desmin and laminin, and the internal elastic lamina are broken down by matrix proteases, particularly matrix metalloproteases 2 and 9 [13,14,15]. These components are replaced by a new transitional extracellular matrix, including FN [15], which may help propogate the inflammatory response especially during changes in shear stress [32]. This matrix remodeling also allows for the outward migration and proliferation of vascular cells. Concurrently, numerous growth signals are released from the breakdown of extracellular matrix [33,48,70] and triggered by altered matrix components [13,15] along with the release of paracrine signaling molecules from bone marrow derived cells [64,132]. These various signaling cascades trigger the differentiation and proliferation of vascular cells. At each stage, inflammatory pathways are the driving forces for the signaling process with recruited BMCs appearing to play an enabling role at each step.

Resolution of Growth and Maturation

As collateral vessels grow and mural cells proliferate, there is a corresponding expansion of the media and a formation of a neointima in a disorganized pattern [96,122]. This corresponds in time with the expansion of lumenal diameter. However, as lumenal diameter increases and network conductance stabilizes, inflammatory markers start to decrease and angiostatic and anti-inflammatory markers increase [69]. Macrophages that have accumulated around collateral vessels also begin to decrease, which parallels a decrease in vascular cell proliferation [4,61,96]. Moreover, there is then a reestablishment of a normal balance between ECM breakdown and stabilization that eventually results in a mature basement membrane [13,14]. Similarly, as inflammatory and growth signals decline, the smooth muscle cells return to a contractile phenotype [96,122]. However, there appear to be two directions that maturating collateral vessels can take. The largest, most developed collateral vessels tend to mature and stabilize, but the smaller, less developed collaterals vessel undergo neointimal hyperplasia and eventual regression [94,96]. This is likely determined by network hemodynamics and collateral perfusion pressure, since the inflammatory process and monocytes simply allow for a bidirectional remodeling that is determined by vascular tone and pressure [7]. Therefore, temporal changes in physical forces, inflammation, growth signaling, and matrix remodeling interact with BMCs and intrinsic vascular cells to coordinate the development of mature collateral vessels. Given the coordinated time-course of the process, it suggests the importance of understanding the sequence of events and cell involvement that occurs during arteriogenesis to understand when, where, and how potential therapies influence each stage of the remodeling process.

LEUKOCYTE TYPES AND TEMPORAL RECRUITMENT IN ARTERIOGENESIS

As early as 1976 [91], it has been shown monocytes play a role in the remodeling process. Since then, a variety of other bone marrow derived cells (BMCs) have also been shown or suggested to mediate arterial remodeling. With the identification of these additional leukocyte populations and subpopulations, there appears to be a complex interrelation between leukocyte recruitment and coordination of the arteriogenesis process. Therefore, there is a need to explore how these various BMC populations influence each other to begin to understand whether certain cell types control important choke points to collateral growth.

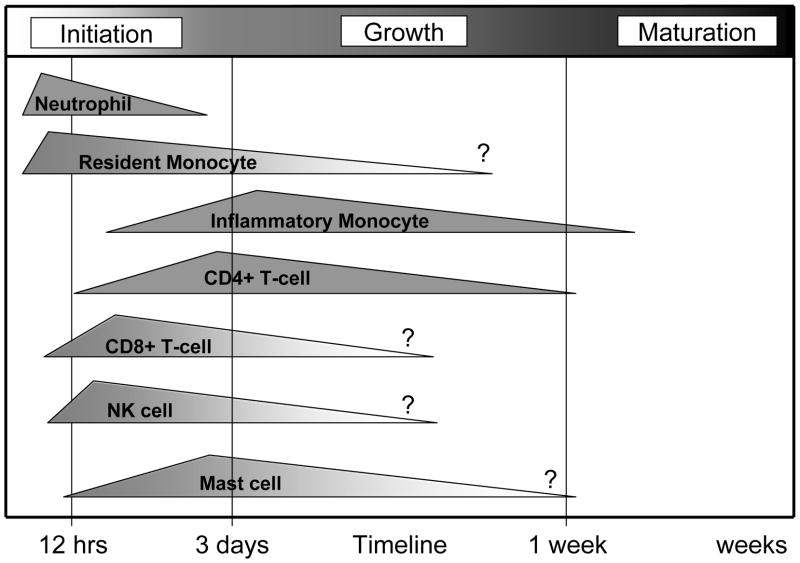

Moreover, as these new BMC populations are incorporated into our understanding, it is also important to incorporate the element of timing. Beyond the classic focus on monocyte and macrophages, the proposed roles for other BMC populations must be explored during the various phases of collateral growth. We contend that there is likely to be a coordinated temporal component to the roles for BMCs during collateral development that parallels the phases of the process: initiation, growth, and maturation (Figure 2). Thus, the exploration of the timing of recruitment and function in various BMC populations could be particularly important for mechanistic insight into the process and for developing therapeutic strategies that individually target the initiation, growth, or maturation phases of collateral development.

Figure 2.

Time line of recruitment of leukocyte subsets during arteriogenesis. The earliest responding leukocytes appear to be neutrophils followed by inflammatory monocytes and mast cells. The temporal recruitment pattern suggests possible relationships between the recruitment of other leukocyte populations. The timing of progenitor cell recruitment, however, is largely unknown. It is important to note that the sequence of leukocyte recruitment and feedback appears to take place within the first few hours and days after the initiation of collateral vessel development. An approximate timeline is given based on BMC recruitment to collateral vessels after femoral arterial ligation.

Neutrophils

As discussed earlier, during the initiation phase, various chemokines and adhesion molecules are upregulated along the stimulated vessel. Neutrophils (PMNs) are one of the first leukocytes to respond to these types of signals in a variety of inflammatory situations. During these events, PMNs are often recruited from the vasculature within hours [2,111]. While there have been few studies on when and where neutrophils are recruited during arteriogenesis, the general pattern of inflammation that occurs in arteriogenesis suggests that neutrophils may play a significant role in the initiation phase. Of the studies that have examined PMN accumulation along collateral vessels, PMNs extensively infiltrate tissues surrounding growing vessels during the initiation phase and their rapid disappearance thereafter [8] suggests a prominent role in commencing collateral growth. This pattern of early neutrophil infiltration within 6 hours followed by monocyte, mast cell, and lymphocyte recruitment agrees with the temporal pattern of cell marker expression observed by Lee et al [69]. Moreover, given the short life span of neutrophils (1–2 days after leaving the circulation), these cells likely have a limited role once the large inflammatory stimulus needed for recruitment disappears.

The question remains, however, of what role do neutrophils play during arteriogenesis. While Hoefer et al. have shown that additional neutrophil recruitment does not aid arteriogenesis [49], it does not exclude the possibility that the initial presence of neutrophils significantly contributes to arteriogenesis. Conversely, Ohki et al [82] show that G-CSF administration promotes revascularization through neutrophil-mediated release of VEGF and subsequent progenitor cell mobilization. Moreover, Soehnlein et al [102] recently demonstrated that neutrophil recruitment and secretion products allow for proper recruitment of inflammatory monocytes but have no significant effect on resident monocytes. These results suggest neutrophils may play a similar role in arteriogenesis, helping to regulate the mobilization of monocyte and progenitor cell subpopulations and recruitment to growing collateral vessels.

Further, neutrophils can play a significant role in vascular remodeling states particularly through the release and production of matrix proteases that alter the microenvironment surrounding vessels [43,102]. Nozawa et al [80] recently demonstrated that neutrophils can act as the key mediators of the angiogenic switch in pancreatic tumors through VEGF and MMP secretion. Similarly, Gong et al [35] have shown PMNs play a critical role in corneal angiogenesis. The changes in extracellular matrix can further alter local growth factor gradients [70] and expose cryptic growth signaling sites [33] that promote vascular cell proliferation. Indeed, the loss of neutrophils can lead to reduced VEGF-induced vascular growth [38], stemming from decreased matrix breakdown. Overall, the role of neutrophils in arteriogenesis is still largely undetermined, but evidence suggests a likely role during the initiation phase of collateral growth. The primary impact of neutrophils and natural killer cells during the initiation phase may help explain why adoptive transfer of these cell types do not aid revascularization when administered 24 hours after hindlimb ligation while the administration of monocytes does enhance revascularization [17]. It may be that cell types involved primarily during one phase are unable to contribute to collateral growth after that phase has been completed. This type of response highlights the need for understanding the timing and sequence of events during arteriogenesis when devising therapeutic strategies.

Lymphocytes

Like neutrophils, several lymphocyte populations have been shown to be involved in coordinating arteriogenesis. T-cells were first suggested to influence arteriogenesis in work with athymic mice [25], which showed impaired collateral vessel growth. Stabile et al [105] followed up by demonstrating that CD4 deletion resulted in impaired revascularization after hindlimb ligation due to decreased recruitment of macrophages to growing collateral vessels. This result was corroborated by antibody-mediated depletion of CD4+ cells leading to impaired arteriogenesis [117]. Stabile et al [106] subsequently demonstrated a role for CD8+ cells in revascularization. The authors proposed a temporal recruitment pattern of lymphocytes, wherein CD8+ cells are first recruited to the collateral vessel and are then able to influence CD4+ cells and monocyte recruitment through the secretion of IL-16. Together, these studies suggest a recruitment of lymphocytes to collaterals vessels that then influences the recruitment of other BMC populations. However, the concept of lymphocyte-mediated recruitment of monocytes is still unresolved. Despite a decreased capacity to recover from ischemic ligation, athymic nude mice appear to recruit more macrophages than wild-type controls [25]. Similarly, the loss of mature T-cells in MHC-II−/− mice results in decreased collateral growth without a significant change in macrophage accumulation in the ischemic tissue [117]. This suggests that the role of lymphocytes may be more of a stimulatory role in terms of helping to activate monocytes and propagate monocytes recruitment to enhance the arteriogenic process [121]. Additionally, it remains to be seen how and if T-cells contribute to arteriogenesis outside of their effects on other BMC populations.

Also within the lymphoid lineage, natural killer lymphocytes have been implicated in playing a role in collateral vessel growth. However, their actions appear more limited to the initiation phase of the response [117]. Two potential roles have been suggested for these cells: tissue clearance to allow for outward remodeling, particularly in constrained tissues such as myocardium [92], and the recruitment of other inflammatory cells [117]. Both roles suggest an impact on collateral growth during the early phases of expansion and leukocyte recruitment, but given the uncertain lifespan and trafficking of natural killer cells [22] it is unknown if these cells contribute to any other phases of collateral remodeling.

Furthermore, it is interesting to note that T-cell and monocyte recruitment vary significantly by mouse strain in terms of quantity and timing of recruitment [117]. Examination of these differences suggests immune cell recruitment can, in part, explain the spectrum of arteriogenic capacities in mouse strains and humans populations [117] in addition to differences in the underlying vascular network [72,129]. Moreover, Taherzadeh et al [110] recently demonstrated a similar role for NK cells in the differential vascular remodeling responses to hypertension seen in BALB/c and C57Bl/6 strains (the strains most often used to exemplify inter-strain differences in collateral growth). The authors presented evidence that differences between natural killer cell function in BALB/C and C57Bl/6 mice contributed to the propensity of the two strains to undergo vascular remodeling, independent from the underlying vascular network structure. Together these findings show a number of roles for lymphocyte populations in coordinating inflammatory cell recruitment and influencing arteriogenesis. These studies suggest an apparent interplay between lymphocytes and other BMC populations in terms of activation and recruitment, which, again, highlight the coordinated nature of collateral growth and the interaction of BMCs with each other to potentiate arteriogenesis. Further, these findings indicate that targeting inflammatory cell function and activity outside of the traditional focus on monocytes may be an effective therapy.

Mast Cells

Despite an important role for mast cells in other vascular remodeling conditions (e.g. atherosclerosis [60,107]) and an initial suggestion of a role in arteriogenesis over a decade ago [122], the role of mast cells in arteriogenesis is largely unexplored. There exists, however, one study on mast cell deficient mice that suggests mast cells do play a significant role in revascularization after hindlimb ischemia [44] with the proposed mechanism centering around mast cell secretion of VEGF and MMP9. Studies on mast cells in other models of vascular remodeling suggest additional likely mechanisms of how these cells are involved in arteriogenesis. First, mast cells secrete a variety of chemokines, cytokine, proteases, and growth factors such as CCL2, GM-CSF, VEGF, PDGF, and bFGF [60,97] known to play a role in arteriogenesis. Second, through the release of these proinflammatory products, mast cells appear to play a critical role in coordinating the recruitment of other inflammatory cells from initiating neutrophil recruitment [97] to promoting macrophage and CD4+ T-cell accumulation [107]. The revascularization study by Heissig et al [44] additionally proposed a mast cell mediated mobilization of progenitor cells from the bone marrow during ischemia that could be enhanced by low-dose radiation. As such, mast cells appear to be involved in arteriogenesis through the recruitment and mobilization of multiple BMC populations and by enhancing vascular cell growth and differentiation through paracrine signalling.

While the timing of mast cell accumulation is poorly understood, the data reported by Wolf et al [122] suggest a larger presence during the initiation and growth phases, with a disappearance as the collateral vessel matures. Since, mast cells are rarely found along collateral vessels in a quiescent state [122], these cells are likely recruited from circulation as basophils. One potential mechanism for this process could be CX3CL1 (fractalkine), which is rapidly (<24 hrs) upregulated upon hindlimb ligation [90] and is known to be a critical mediator of basophil recruitment in vitro [83] and in vivo [30]. Given the proposed role in the recruitment of early response cells, such as neutrophils, this fits an early recruitment time course with a sustained presence during the growth phase as paracrine support cells and coordinators of BMC recruitment.

Monocytes

In contrast, as the most widely studied inflammatory cell involved in arteriogenesis, monocytes have been shown to be critical to the process through multiple methods [10,41,85]. However, even though a role for monocytes has been clearly established, there is now a further need to explore when and where monocytes are recruited and how different subpopulations of monocytes function in collateral development.

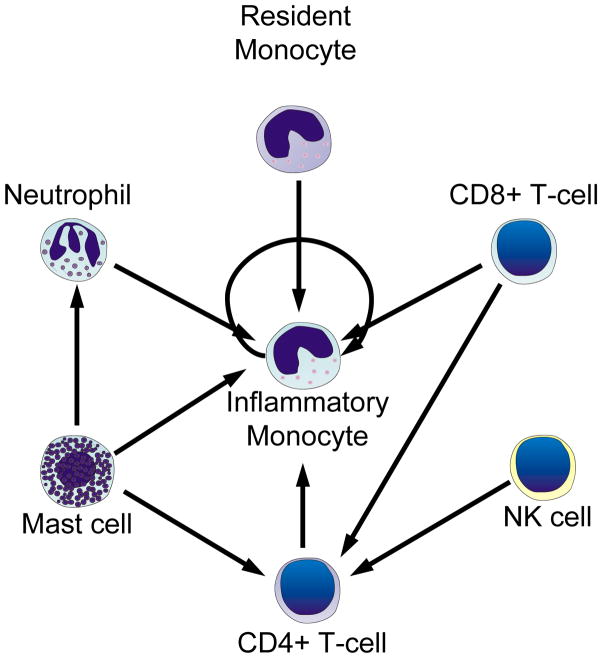

The importance of the temporal aspect of monocyte recruitment is emphasized by the mounting evidence that other inflammatory cells help coordinate their recruitment (Figure 3). In terms of the timing of monocyte recruitment to collateral vessels, it is known that monocytes are particularly prominent in the growing phase of collateral development [4,61]. However, the role of monocytes during the initiation of collateral growth is largely unknown. As previously discussed, PMNs are often the first responders to inflammation [111], and in comparison to PMNs, monocytes have a much slower accumulation within collateral tissues after acute occlusion [16,25,69]. In other instances of inflammation-induced recruitment of immune cells, such as ischemic injury [23,111], there is a similar process of initial neutrophil predominance that is replaced by macrophages over the course of a few days. As such, macrophages accumulate along collateral vessels within 12 hours after ligation [96] and reach a maximum at around three days but disappear over time [4,8,61,96]. This accumulation correlates with vascular cell proliferation. Subsequently, as the collateral vessel begins to mature and proliferative index decreases, the presence of macrophages decreases [4,61,96]. The fact that the temporal nature of this recruitment and sustained presence helps elucidate the primary role of monocytes in arteriogenesis belies the importance of understanding the time course of monocyte recruitment. Moreover, increases in circulating macrophage levels after collateral vessels have begun the growth phase do not appear to impact further collateral growth [41]. This suggests that macrophages help to potentiate vascular cell growth and structural remodeling during the growth phase but have a decreasing role as these vessels mature. Such a role correlates with a recent study by Bakker et al [7] showing that monocytes act as permissive cells for collateral vessel remodeling with tone dictating the direction of growth (inward vs. outward). However, these data also raise the question of whether an increase in monocyte activity and/or circulating concentration can improve collateral growth if collateral growth is not in the phase where monocyte activity has the greatest impact. Thus, understanding the interplay of timing and recruitment of monocytes by other BMC populations will be critical to determining the exact role of monocytes during arteriogenesis and their optimal therapeutic use.

Figure 3.

Proposed interconnected relationships of recruitment between BMC populations. Many BMC populations may aid arteriogenesis through the activation and subsequent recruitment of inflammatory monocytes. However, the disruption in earlier BMC recruitment may amplify collateral growth impairments through the reduced recruitment and synergistic activation of other, later-arising BMC populations. How and if bone marrow-derived progenitor cells influence the recruitment of other BMC populations is still largely unknown.

Furthermore, many of these studies on the role of macrophages and monocytes use a definition that encompasses a broad spectrum of cell subpopulations. The recent discovery of functional differences between these monocyte subpopulations [34,36] and their varying roles in other types of vascular remodeling (e.g. atherosclerosis [109,123]) underscores the need to further understand the role of monocyte subpopulations in arteriogenesis. The two most studied of these subpopulations have been termed “resident” (Gr1−/LyC6hi) and “inflammatory (Gr1+/LyC6lo) [123]. These subpopulations may be identified by a variety of markers, such as relative CCR2 and CX3CR1 expression. These markers have been best characterized in mice but have other mammalian and human analogs [36]. A study by Capoccia et al [16] using the adoptive transfer of bone marrow mononuclear cells suggests a functional difference in the capacity of these two monocyte subpopulations to help stimulate collateral growth.

Studies of these characteristic chemokine receptors additionally suggest both monocyte populations have a role in vascular remodeling and arteriogenesis. The most studied chemokine pathway, the CCL2 (MCP-1) and CCR2 axis [101], along with several other studies [16,37] provide ample evidence that inflammatory monocytes (CCR2hiCX3CR1lo) are critical for coordinating arteriogenesis. The more recent discovery of the resident monocyte subset has prompted one study that also suggests a role for resident monocytes [90]. While few if any studies have compared the roles of the two monocyte subsets in arteriogenesis, there is clear evidence showing distinct functional roles in guiding pathologic remodeling in atherosclerosis [109,123]. Therefore, based on the observation that atherosclerosis and arteriogenesis share many similar mechanisms [31], it is likely these two monocyte subsets differentially regulation arteriogenesis.

Additionally, the inflammatory and resident subsets exhibit functionally different patterns of recruitment, which can play an important role in vascular remodeling. The inflammatory monocytes (CCR2hiCX3CR1lo) reside primarily in the bone marrow and are mobilized from the bone marrow and spleen [108] to be recruited to sites of active inflammation through endothelial surface expression of CCL2 ligand [34]. In contrast resident monocytes (CCR2loCX3CR1hi) exhibit a patrolling behavior with a large intravascular population that crawls along the venous endothelium, rapidly extravasating to sites of inflammation in a first response like fashion [6]. This different pattern of spatial and temporal recruitment results in a differential sensitivity to neutrophil-mediated recruitment of monocytes during acute inflammation [102], where inflammatory monocyte recruitment is decreased with neutrophil depletion. Moreover, in a recent preliminary study in our laboratory, we compared how differentially knocking out the key chemokine receptors for the two subsets (CCR2 and CX3CR1) from bone marrow derived cells effects microvascular remodeling [74]. In a model of inflammation-associated arteriogenesis, BMC specific deletion of CCR2 completely abrogated arteriolar remodeling [78] but did not significantly alter venular remodeling [74]. In contrast, the loss of CX3CR1 significantly attenuated venular and arteriolar remodeling, though not to the same extent as the loss of CCR2 [74]. The different patterns of recruitment between the two subsets results may help explain our results. Taken together, these data provide an example of how functional differences in spatial and temporal recruitment can affect vascular remodeling. As such, it is important to consider the various roles and recruitment patterns of monocyte subsets in arteriogenesis to understand the array of functions monocytes are involved in during collateral development.

Bone Marrow Derived Progenitor Cells

Since the discovery of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) by Asahara et al [5], these cells have stimulated a wealth of studies and have taken a prominent role as a means for treating ischemic disease. Numerous studies have shown EPCs, other bone marrow derived progenitor cells (BMPCs), and induced pluripotent stem cells have the ability to enhance revascularization and take part in vascular repair [5,66,71,127]. Two key problems, however, have limited the ability to translate these laboratory successes to the clinic. First, there is not a definitive set of cell markers for BMPCs or universal isolation techniques, which complicates the interpretation of how these cells influence vascular remodeling and their potential for clinical use [66,125,127]. Second, there is a debate, particularly in the arteriogenesis field, of how these cells influence remodeling. Particularly, controversy exists regarding whether BMPCs incorporate into the vasculature and/or act as paracrine signaling sources to support vascular cell growth. This lack of a clear mechanism and difficulty in distinguishing specific cell populations prevents our ability to known where BMPC involvement could have the greatest clinical impact.

Increasing evidence suggests a widely heterogeneous BMPC population [51,125,127] with at least two functionally distinct sets of EPCs (early and late EPCs [53]), angiogenic T-cells [52], and a variety of other monocyte subpopulations [51]. As such, the variety of isolation techniques and surface markers used by various groups have likely pulled unique subpopulations from this complex mix of BMPCs that cannot be directly compared between groups, which has resulted in the large variations of reported therapeutic potential [66,127]. Furthermore, each of these various cell populations may play different functional roles during vascular repair, with new functionally different subpopulations arising during ex vivo culture. For example, the neovascularization benefits from the administration of EPCs that arise earlier from colony-forming units during ex vivo expansion (early EPCs) appear to stem from their paracrine support cell role [53], whereby these cells contribute via secretion of angiogenic cytokines and growth factors. Conversely, EPCs arising late in ex vivo culture (late EPCs) appear to function in revascularization by incorporating into activated endothelium and expanding the endothelial cell population [53]. These two EPC populations can work together synergistically to promote neovascularization after hindlimb ischemia [125]. Similarly, a subpopulation of T cells first identified during EPC colony expansion have the capacity to enhance neovascularization after hindlimb ischemia independent from, and synergistically with, EPCs [52]. Additionally, initial studies on the adoptive transfer of BM monocytic cells show a marked influence on endogenous leukocyte recruitment, which suggests another mechanism of action [16]. All of these studies point to a complex, coordinated interaction of a wide array of bone marrow derived mononuclear cells, especially during ex vivo expansion and reinjection. However, their individual roles and interactions will only be well understood by defining a set of common markers for the various subpopulations and an approach that examines how these cells interact with multiple other cell types.

Multiple groups have demonstrated the potential role for injected BMPCs, after ex vivo culture and/or concentration, to transdifferentiate and directly incorporate into the vascular wall. However, without ex vivo manipulation, the potential for endogenous BMPCs to enhance collateral growth significantly by directly expanding endothelial and/or smooth muscle cell populations appears much less likely. When examined by high resolution confocal microscopy, endogenous bone marrow-derived cells were not seen by Ziegelhoeffer et al [132] to significantly transdifferentiate into endothelial and or smooth muscle cells, attributing the difference from initial reports of extensive incorporation to lower resolution traditional immunohistochemistry techniques. Similar examinations by our group [77,81] and others [17,64] for a variety of vascular remodeling preparations show no evidence that endogenous bone marrow-derived cells can significantly contribute to vascular growth by transdifferentiating and directly expanding endothelial and/or smooth cell populations. Instead, it appears that bone marrow-derived cells contribute to the collateral growth process by localizing to collateral vessels and secreting a variety of paracrine signals to enhance native vascular cell growth and proliferation [63,64]. As discussed earlier, BMPCs likely also contribute to the process by coordinating the recruitment of other leukocyte populations.

At this point, we contend there is a need to understand how various BMPC populations influence other leukocytes and to determine how these cells can best be used to enhance collateral vessel growth synergistically. Moreover, the discussion of how ex vivo expanded BMPCs versus native BMPCs differ in driving collateral growth through paracrine signaling and/or directly incorporating and expanding vascular cell populations may provide unique strategies for therapeutic stimulation. On one hand, the use of BMPCs to support collateral growth through paracrine signaling can pull on the much larger native vascular cell populations to promote collateral growth during a transient arteriogenic stimulus. However, it has been suggested that endothelial dysfunction can significantly diminish the capacity of an individual to develop collateral vessels [65]. In such a case, the use of ex vivo expanded BMPCs for incorporation into the native vasculature may provide a means of providing healthy, non-dysfunctional endothelial cells. In either case, there is a substantial need to identify the specific cell populations involved in both processes and the natural time-course for both mechanisms in order to arrive at an optimal therapeutic strategy.

Resident Expansion versus Recruitment of Leukocytes

The debate over whether macrophages arise primarily from resident sources or from recruitment provides a key example of the need to further understand the temporal and spatial recruitment patterns of leukocyte types. It has been argued that resident macrophages and vascular precursor cells are the primary sources for BMCs that support arteriogenesis [55,57,61]. In 2004, Khmelewski et al [61] used cyclophosphamide to deplete circulating monocytes to show that the number of macrophages around collateral vessels increases, despite a 99% reduction in circulating monocyte counts. While there were limitations to the study that leave room for debating the extent of their role, the results still suggest some role for resident macrophages [12,55]. Similarly, fluorescently labeled BMC reconstitutions by our group [81] and Ziegelhoeffer et al [132], show a significant population of BMCs that reside in normal tissue and could serve as ample sources for resident BMCs. Recent studies have suggested these perivascular cells act as a source of mesenchymal progenitor cells (recently reviewed by Corselli [24]). However, the primary focus on monocytes neglects the known role of other inflammatory cells that are recruited to collateral vessels such as PMNs and lymphocytes. Given that neutrophils have no resident cell populations and lymphocytes have little capacity to proliferate in extra-lymphoid tissue, there is clear evidence that some populations of circulating inflammatory cells are recruited to collateral vessels. Therefore, it is likely that some populations of monocytes are recruited as well. However, the extent to which resident macrophages contribute to, and how these cells function within, the arteriogenic process is largely unknown. One potential solution to exploring this question may be to differentially ablate resident macrophages or circulating monocytes using CD11b-DTR mice in a method similar to Arnold et al [3].

While there likely is a role for resident macrophage and other support cells that arise from a perivascular pool of previously recruited BMCs, the debate itself centers on a lack of understanding of temporal and spatial recruitment of leukocytes due to the “shear-recruitment paradox”. This paradox argues that the physical forces that stimulate collateral growth (i.e. high shear stresses) are less hospitable for leukocyte adhesion. The argument is used as a primary reason for resident cell predominance [55,57,61], because recruitment of leukocytes through the arterial wall would not be able to sufficiently explain leukocyte accumulation around collateral vessels. This logic neglects, however, a key element that collateral arteries are often paired with neighboring veins. Venules may be a significant additional source of leukocyte recruitment that could help explain rapid perivascular accumulation during high arterial shear. Venules are the primary site of leukocyte rolling and adhesion for a wide variety of inflammatory signals, and venules may respond to several of the recruitment signals arising from nearby stimulated arteries (e.g. diffusing chemokines or gaseous products produced in stimulated arterial cells). Communication of diffusible gases and cytokines from venules to arterioles is well established for the regulation of microvascular blood flow (see review by Hester and Hammer [47]). Multiple investigators have found that signals released from venular endothelium during elevated shear stress, such as NO, are transferred to paired arterioles and can modulate their behavior [11,76]. Similar communication from artery to vein for leukocyte recruitment also appears to exist. For example, activation of arterial endothelium appears to be able to create a signaling gradient for leukocyte recruitment in the neighboring vein through reactive oxygen species [59], which are known to be involved in arteriogenesis [73]. Moreover, our lab has recently explored this question of whether ROS can mediate arterio-venous crosstalk in a rat mesentery model of arteriogenesis. We found that ROS induced by high wall shear stresses enhances leukocyte adhesion in both the artery and its paired vein (Song J, unpublished observations). Between the precedence of venulo-arteriolar cross-talk and our recent observations, it would not be surprising to find that the inflammatory and adhesion signals from arteries upon arteriogenic stimulation could be transmitted to paired or neighboring venules and that venules may be a major site of BMC recruitment during arteriogenesis. However, the question of spatial patterning of leukocyte recruitment during arteriogenesis has been widely avoided, despite the capacity to help provide a solution to the shear-recruitment paradox.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Given the numerous interactions between leukocyte subtypes and the increased understanding that each subtype may play a particular role within the phases of collateral growth, there is a need to explore, in depth, the recruitment pattern of various leukocyte populations over the time course of arteriogenesis. As such, there is still a place for descriptive studies to examine when various leukocyte populations are recruited to collateral vessels (e.g. flow cytometry studies of isolated collateral vessels, whereby it is possible to screen for numerous leukocyte populations). Such a detailed understanding is particularly important at the early time points where collateral vessels are undergoing rapid changes from quiescent state through an initiation phase to the growth phase of arteriogenesis. Understanding the temporal roles of these various leukocyte populations could explain the dynamics of leukocyte interaction and may reveal particular target populations that enhance specific phases of the collateral growth cycle. Moreover, coupled with studies of gene expression at multiple time points through microarray or RNA sequencing of isolated vessels, these techniques have the power to begin teasing apart the molecular signaling pathways of the various collateral growth phases and how bone marrow-derived cells influence the process. Even without such explorations, the emerging evidence on the interactions between the numerous cell populations and signaling events involved in arteriogenesis calls for the reinterpretation of past and future results. It will be important to view these findings through the lens of how alterations in specific pathways during a reductionist approach could affect various other elements in the interconnected arteriogenesis pathway.

Systems and Computational Biology as a New Frontier

Systems biology, therefore, presents a powerful tool for looking at how the various leukocyte populations and signaling cascades work together to drive arteriogenesis at multiple levels. As highlighted by the recent study by Zbinden et al, gene expression pathway analysis from growing collateral vessels can reveal previously unexplored signaling pathways for stimulating collateral growth [69,128]. Similarly, computational network analysis provided an improved understanding of how nitric oxide synthase signaling helps mediate arteriogenesis and collateral vessel network maintenance [26]. At a higher tissue scale, earlier modeling of vascular network resistance helped demonstrate the adaptation of the collateral network as the primary means for reperfusion after arterial occlusion [67,113]. Moreover, the recent computational modeling in the study by Mac Gabhann et al suggests that only a minimum of collateral pathways need exist for adequate ischemia protection [72], which is corroborated by previous theoretical modeling from de Lussanet [27] and in vivo patient data [89]. This computational insight raises the prospect of using targeted delivery of therapeutics for treatment without the need of systemic and extensive collateral network restructuring. At a cellular and tissue level, computational modeling could begin to help illuminate how the numerous types of bone marrow-derived cells (including leukocytes and progenitor cells) influence one another and interact with the native vascular cells. The spatial and temporal patterning of leukocyte recruitment, discussed in the previous section, suggest the existence of numerous interactions that could generate rate-limiting choke points in cell recruitment and collateral growth. The identification of such rate-limiting and critical steps in the arteriogenic process could prove invaluable for identifying key therapeutic targets both for the enhancement of collateral growth or for the inhibition of the growth of feeding arteries to tumors. Considering the numerous pathways and feedback interactions that are already known to occur in the remodeling process, the screening of the dynamics of these interactions is best suited to computational modeling approaches followed by targeted in vivo experiments (see review by Sefcik et al [99]). Such insights can further enhance our understanding of the temporal aspects of collateral growth and could identify specific targets for the different phases of arteriogenesis.

Identifying the Common Impairments to Collateral Growth in Patients

The limited success of large therapeutic arteriogenesis trials despite success in smaller scale trials and subsets of patients may additionally suggest that there are multiple origins of collateral growth impairment and that treatments need to be tailored to specific patient populations [65,115]. In particular, there are two questions to answer about the clinical population before moving forward. 1) Are symptomatic patients unable to develop collateral pathways because of an underlying deficit in their endogenous vascular structure and a lack of adequate pre-existing collateral pathways or is there an impairment in their ability to coordinate and undergo arteriogenesis in the collateral vessels that do exist? 2) In patients that do not develop adequate growth from their pre-existing collaterals, is this impairment occurring during the initiation, growth, and/or maturation phases of arteriogenesis? In each patient, there are likely to be elements of both answers from both questions. However, understanding the relative importance of these factors through non- or minimally invasive measures of vessel morphology and biomarkers for key elements of arteriogenic phases could provide an invaluable guide for directing patient appropriate therapeutic strategies.

There are also implications for arteriogenesis approaches in terms of the balance between the existence of a pre-existing collateral network versus the ability to develop those pre-existing bridging arteries. Recent studies in mice have demonstrated a wide variation in vascular network structure that lead to collateral-extensive or collateral-sparse networks according to genetic background [45,72,129]. These variations have a functional impact on revascularization and recovery after ischemic insult. Such variations likely exist in patient populations. In patients with poor existing collateral networks, it may be necessary to involve a two-fold approach of stimulating the targeted growth of capillary arcades and then stimulating arterialization and collateral growth (e.g. the recent study by Benest et al [9]). One interesting observation from the work by MacGabhann et al was that only a relative few number of collaterals need exist to protect against ischemia, which suggests that targeted therapy to establish a limited number of collateral vessels may be all that is needed clinically [72]. Conversely, patients with a deficiency in developing collateral vessels may be more responsive to bone marrow derived cell therapy (including leukocytes and progenitor cells), as cell based therapies provide a route for delivering a complex mixture of growth factors and cytokines to coordinate remodeling as compared to individual growth factor treatments [65]. Moreover, vascular progenitor cell populations that trend toward incorporating into the endothelial lining may be useful in helping to reestablish normal endothelial function.

However, in order to utilize the full benefits of cell-based therapy, there is a need to consider what elements of the arteriogenesis process are impaired in the patient population of interest. Impairments in each phase of arteriogenic growth may imply a need for different approaches for stimulating arteriogenesis in terms of cell types, targeting, and timing of administration. Because the initiation phase is primarily mediated by the endothelial response to increase shear stress along collateral pathways, conditions that lead to endothelial dysfunction (e.g. diabetes [58] and aging [88]) exhibit an impaired arteriogenesis, likely through impaired initiation and network maintenance. This is exemplified by dysfunctional nitric oxide signaling and reactive oxygen species generation resulting in impaired collateral growth that can be restored by normalizing endothelial function and the initiation phase of arteriogenesis [130,131,133]. Conversely, aiding growth in later steps through the administration of a growth factor like VEGF may not restore collateral growth [75]. Additionally, it is important to consider how decreased endothelial activation could serve to reduce the recruitment of leukocytes that are involved in the initiation and subsequent phases of arteriogenesis. Such disruptions in leukocyte recruitment may explain part of the decreased collateral growth seen in aged mice [88] and nitric oxide synthase knockout mice [112].

Impairments in leukocyte recruitment during the initiation phase may also arise from altered leukocyte migration and function and lead to reduced arteriogenesis. Blocking slow rolling or firm adhesion will substantially reduce collateral growth [50]. Similarly, bone marrow-specific knockout of chemokine receptors such as CCR2 can prevent leukocyte recruitment during the initiation phase [78] and impair collateral growth [42,78]. Moreover, the decreased collateral growth seen in diabetes mellitus patients can be partially explained by impaired monocyte migration through VEGF chemotaxis [120]. Therefore, patients with abnormal initiation of collateral growth may stem from individual or a combination of impairments in endothelial function and BMC function, which may require different therapeutic strategies.

Similarly, patients’ coexistent pathologies and inherent capacity for collateral growth can manifest from diminished paracrine signaling function of BMCs, which can affect the growth phase of arteriogenesis. For example, BMCs isolated from patients with coronary artery disease have reduced capacity for coordinating revascularization [39] in part from decreased VEGF production in response to hypoxia [98]. Likewise, transcriptional profiling of monocyte function by Chittenden et al [20] demonstrated impaired monocyte activation in patients with coronary arterial disease. Genetic lesions in a variety key pathways within BMC populations (e.g. MMP9 in neutrophils [43]) could dramatically alter arteriogenic capacity. These results describe a scenario wherein, even with adequate recruitment, altered BMC function in symptomatic patients may yield reduced collateral growth due to an impaired growth phase of the arteriogenesis process. Further, given the complexity of the recruitment pattern of BMCs to collateral vessels, altered BMC function likely compromises further BMC recruitment and vascular cell activation.

Additionally, while largely unexplored, there are likely elements of impaired maturation and collateral vessel maintenance in certain patient populations. This can be inferred from several recent studies. Recent work from Faber’s group suggests that certain genetic factors, such as Clic4 and VEGF-A are required to maintain the collateral connections during embryonic and perinatal development [18,19,21]. Moreover, Dai et al [26] recently demonstrated that nitric oxide signaling is critical to maintaining collateral vessel networks during adulthood. Given the age related declines of nitric oxide production and availability, this may help explain collateral vessel dropout seen with aging [103] and the age-related decreases in collateral growth seen during hindlimb ligation [26,86,88]. Collateral growth is also complicated by the fact that there is often preferential pruning of collateral vessels over time as some initially developed collateral vessels undergo stabilization during the maturation phase, while others undergo regression [93,133]. Therefore, any arteriogenesis therapies will additionally need to factor in whether the stimuli will be present to maintain or stabilize any newly developed collateral vessels. As such, these findings suggest that there is a need to understand the various factors involved that are necessary to promote collateral vessel stabilization and preservation of bridging arteries in the network and how BMCs can influence this process.

When taken as a whole, the evidence suggests that there are combinations of factors that impair collateral growth in symptomatic patient populations. These impairments can occur in each of the different phases of arteriogenesis and can influence BMC function and recruitment at all levels, which, in turn, can influence collateral vessel growth at multiple levels from initiation to growth to maturation and preservation. Each of these factors likely influences the efficacy of various therapeutic strategies in the various patient populations. Therefore, there is a need to define risk factors and biomarkers that correlate with specific impairments in collateral growth in order to select the most efficacious therapies.

Such considerations will be particularly important when evaluating the results of upcoming large-scale arteriogenesis trials using BMCs as the therapeutic agent (e.g BONMOT-CLI [1] and JUVENTAS [104] trials). Though initial pilot trials have shown success in treating peripheral arterial disease and coronary arterial disease [68,114], the lack of understanding of individual patient deficits and the coordination of BMCs in arteriogenesis may lessen the potential benefits seen during large scale trials. A similar incomplete understanding of the coordination of growth factor signaling led to discouraging results in multiple large-scale trials using single growth factors, despite promising results in pilot studies [95,114,115,119].

CONCLUSIONS

Arteriogenesis is a complex process that is highly dependent on proper bone marrow derived cell (i.e. leukocytes and progenitor cells) recruitment and function. The process follows an ordered sequence of events with specific BMC populations recruited at specific times and locations. Many of the actions of these BMC populations are interrelated, influencing endothelial and smooth muscle cell function, as well as the function of other BMCs during subsequent phases. Given the complex interactions involved throughout the process, moving forward, it will be important to understand how collateral growth is working as a multi-stage process in relation to BMC activation, recruitment, and function. This further exploration would, ideally, use a two-fold investigation into how arteriogenesis is coordinated across multiple elements in normal conditions (i.e. during femoral arterial ligation, where the process is very controlled and has a standard time course) and an examination of pathological conditions to determine where the process is going wrong in the patient population of interest. As such, there is a need to use more “systems-like” approaches where cell population and function interactions throughout the sequence of events in arteriogenesis are considered in parallel during experiment design and interpretation. Such approaches would likely uncover novel bottlenecks for therapeutic targeting and help guide treatment strategies according to the pathological condition of specific patient populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions and many stimulating conversations with the colleagues in the Price and Skalak laboratories. The unpublished work by the authors referred to in this review was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (5R01HL074082 to RJP) and the American Heart Association (09PRE2060385 to JKM/RJP). Additional support came from University of Virginia Center for Undergraduate Education and the American Medical Association Foundation.

Support provided by: NIH-R01HL074082 (RJP)

AHA-09PRE2060385 (JKM/RJP)

University of Virginia CUE (JKM/RJP)

AMA Foundation (JKM/RJP)

References

- 1.Amann B, Ludemann C, Ruckert R, Lawall H, Liesenfeld B, Schneider M, Schmidt-Lucke J. Design and rationale of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study for autologous bone marrow cell transplantation in critical limb ischemia: the BONe Marrow Outcomes Trial in Critical Limb Ischemia (BONMOT-CLI) Vasa. 2008;37:319–325. doi: 10.1024/0301-1526.37.4.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrade-Silva AR, Ramalho FS, Ramalho LN, Saavedra-Lopes M, Jordao AA, Jr, Vanucchi H, Piccinato CE, Zucoloto S. Effect of NFkappaB inhibition by CAPE on skeletal muscle ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Surg Res. 2009;153:254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnold L, Henry A, Poron F, Baba-Amer Y, van Rooijen N, Plonquet A, Gherardi RK, Chazaud B. Inflammatory monocytes recruited after skeletal muscle injury switch into antiinflammatory macrophages to support myogenesis. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1057–1069. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arras M, Ito WD, Scholz D, Winkler B, Schaper J, Schaper W. Monocyte activation in angiogenesis and collateral growth in the rabbit hindlimb. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:40–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI119877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asahara T, Murohara T, Sullivan A, Silver M, van der ZR, Li T, Witzenbichler B, Schatteman G, Isner JM. Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis. Science. 1997;275:964–967. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Auffray C, Fogg D, Garfa M, Elain G, Join-Lambert O, Kayal S, Sarnacki S, Cumano A, Lauvau G, Geissmann F. Monitoring of blood vessels and tissues by a population of monocytes with patrolling behavior. Science. 2007;317:666–670. doi: 10.1126/science.1142883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bakker EN, Matlung HL, Bonta P, de Vries CJ, van Rooijen N, Vanbavel E. Blood flow-dependent arterial remodelling is facilitated by inflammation but directed by vascular tone. Cardiovasc Res. 2008:78. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Behm CZ, Kaufmann BA, Carr C, Lankford M, Sanders JM, Rose CE, Kaul S, Lindner JR. Molecular imaging of endothelial vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 expression and inflammatory cell recruitment during vasculogenesis and ischemia-mediated arteriogenesis. Circulation. 2008:117. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.744037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benest AV, Stone OA, Miller WH, Glover CP, Uney JB, Baker AH, Harper SJ, Bates DO. Arteriolar genesis and angiogenesis induced by endothelial nitric oxide synthase overexpression results in a mature vasculature. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1462–1468. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.169375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergmann CE, Hoefer IE, Meder B, Roth H, van Royen N, Breit SM, Jost MM, Aharinejad S, Hartmann S, Buschmann IR. Arteriogenesis depends on circulating monocytes and macrophage accumulation and is severely depressed in op/op mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:59–65. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0206087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boegehold MA. Shear-dependent release of venular nitric oxide: effect on arteriolar tone in rat striated muscle. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H387–H395. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.2.H387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buschmann IR, Hoefer IE. All arteriogenesis is local? Home boys versus the newcomers. Circ Res. 2004;95:e72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai W, Vosschulte R, fsah-Hedjri A, Koltai S, Kocsis E, Scholz D, Kostin S, Schaper W, Schaper J. Altered balance between extracellular proteolysis and antiproteolysis is associated with adaptive coronary arteriogenesis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:997–1011. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cai WJ, Kocsis E, Wu X, Rodriguez M, Luo X, Schaper W, Schaper J. Remodeling of the vascular tunica media is essential for development of collateral vessels in the canine heart. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;264:201–210. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000044389.65590.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai WJ, Koltai S, Kocsis E, Scholz D, Kostin S, Luo X, Schaper W, Schaper J. Remodeling of the adventitia during coronary arteriogenesis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H31–H40. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00478.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Capoccia BJ, Gregory AD, Link DC. Recruitment of the inflammatory subset of monocytes to sites of ischemia induces angiogenesis in a monocyte chemoattractant protein-1-dependent fashion. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:760–768. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1107756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Capoccia BJ, Shepherd RM, Link DC. G-CSF and AMD3100 mobilize monocytes into the blood that stimulate angiogenesis in vivo through a paracrine mechanism. Blood. 2006;108:2438–2445. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-013755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chalothorn D, Faber JE. Formation and maturation of the native cerebral collateral circulation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.03.014. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chalothorn D, Zhang H, Smith JE, Edwards JC, Faber JE. Chloride intracellular channel-4 is a determinant of native collateral formation in skeletal muscle and brain. Circ Res. 2009;105:89–98. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.197145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chittenden TW, Sherman JA, Xiong F, Hall AE, Lanahan AA, Taylor JM, Duan H, Pearlman JD, Moore JH, Schwartz SM, Simons M. Transcriptional profiling in coronary artery disease: indications for novel markers of coronary collateralization. Circulation. 2006;114:1811–1820. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.628396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clayton JA, Chalothorn D, Faber JE. Vascular endothelial growth factor-A specifies formation of native collaterals and regulates collateral growth in ischemia. Circ Res. 2008;103:1027–1036. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.181115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colucci F, Caligiuri MA, Di Santo JP. What does it take to make a natural killer? Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:413–425. doi: 10.1038/nri1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Contreras-Shannon V, Ochoa O, Reyes-Reyna SM, Sun D, Michalek JE, Kuziel WA, McManus LM, Shireman PK. Fat accumulation with altered inflammation and regeneration in skeletal muscle of CCR2−/− mice following ischemic injury. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007:292. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00154.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corselli M, Chen CW, Crisan M, Lazzari L, Peault B. Perivascular Ancestors of Adult Multipotent Stem Cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1104–1109. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.191643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Couffinhal T, Silver M, Kearney M, Sullivan A, Witzenbichler B, Magner M, Annex B, Peters K, Isner JM. Impaired collateral vessel development associated with reduced expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in ApoE−/− mice. Circulation. 1999;99:3188–3198. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.24.3188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dai X, Faber JE. Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase Deficiency Causes Collateral Vessel Rarefaction and Impairs Activation of a Cell Cycle Gene Network During Arteriogenesis. Circ Res. 2010 doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.212746. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Lussanet QG, van Golde JC, Beets-Tan RG, de Haan MW, Zaar DV, Post MJ, Huijberts MS, Schaper NC, van Engelshoven JM, Backes WH. Magnetic resonance angiography of collateral vessel growth in a rabbit femoral artery ligation model. NMR Biomed. 2006;19:77–83. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deindl E, Buschmann I, Hoefer IE, Podzuweit T, Boengler K, Vogel S, van Royen N, Fernandez B, Schaper W. Role of ischemia and of hypoxia-inducible genes in arteriogenesis after femoral artery occlusion in the rabbit. Circ Res. 2001;89:779–786. doi: 10.1161/hh2101.098613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eitenmuller I, Volger O, Kluge A, Troidl K, Barancik M, Cai WJ, Heil M, Pipp F, Fischer S, Horrevoets AJ, Schmitz-Rixen T, Schaper W. The range of adaptation by collateral vessels after femoral artery occlusion. Circ Res. 2006;99:656–662. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000242560.77512.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El-Shazly A, Berger P, Girodet PO, Ousova O, Fayon M, Vernejoux JM, Marthan R, Tunon-de-Lara JM. Fraktalkine produced by airway smooth muscle cells contributes to mast cell recruitment in asthma. J Immunol. 2006;176:1860–1868. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Epstein SE, Stabile E, Kinnaird T, Lee CW, Clavijo L, Burnett MS. Janus phenomenon: the interrelated tradeoffs inherent in therapies designed to enhance collateral formation and those designed to inhibit atherogenesis. Circulation. 2004;109:2826–2831. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000132468.82942.F5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feaver RE, Gelfand BD, Wang C, Schwartz MA, Blackman BR. Atheroprone hemodynamics regulate fibronectin deposition to create positive feedback that sustains endothelial inflammation. Circ Res. 2010;106:1703–1711. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.216283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gagne PJ, Tihonov N, Li X, Glaser J, Qiao J, Silberstein M, Yee H, Gagne E, Brooks P. Temporal exposure of cryptic collagen epitopes within ischemic muscle during hindlimb reperfusion. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:1349–1359. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61222-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman DR. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity. 2003;19:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gong Y, Koh DR. Neutrophils promote inflammatory angiogenesis via release of preformed VEGF in an in vivo corneal model. Cell Tissue Res. 2010;339:437–448. doi: 10.1007/s00441-009-0908-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gordon S, Taylor PR. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:953–964. doi: 10.1038/nri1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gregory AD, Capoccia BJ, Woloszynek JR, Link DC. Systemic levels of G-CSF and interleukin-6 determine the angiogenic potential of bone marrow resident monocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;99 doi: 10.1189/jlb.0709499. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hao Q, Chen Y, Zhu Y, Fan Y, Palmer D, Su H, Young WL, Yang GY. Neutrophil depletion decreases VEGF-induced focal angiogenesis in the mature mouse brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1853–1860. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heeschen C, Lehmann R, Honold J, Assmus B, Aicher A, Walter DH, Martin H, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Profoundly reduced neovascularization capacity of bone marrow mononuclear cells derived from patients with chronic ischemic heart disease. Circulation. 2004;109:1615–1622. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124476.32871.E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heil M, Schaper W. Influence of mechanical, cellular, and molecular factors on collateral artery growth (arteriogenesis) Circ Res. 2004;95:449–458. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000141145.78900.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heil M, Ziegelhoeffer T, Pipp F, Kostin S, Martin S, Clauss M, Schaper W. Blood monocyte concentration is critical for enhancement of collateral artery growth. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H2411–H2419. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01098.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heil M, Ziegelhoeffer T, Wagner S, Fernandez B, Helisch A, Martin S, Tribulova S, Kuziel WA, Bachmann G, Schaper W. Collateral artery growth (arteriogenesis) after experimental arterial occlusion is impaired in mice lacking CC-chemokine receptor-2. Circ Res. 2004;94:671–677. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000122041.73808.B5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heissig B, Nishida C, Tashiro Y, Sato Y, Ishihara M, Ohki M, Gritli I, Rosenkvist J, Hattori K. Role of neutrophil-derived matrix metalloproteinase-9 in tissue regeneration. Histol and Histopathol. 2010;25:765–770. doi: 10.14670/HH-25.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heissig B, Rafii S, Akiyama H, Ohki Y, Sato Y, Rafael T, Zhu Z, Hicklin DJ, Okumura K, Ogawa H, Werb Z, Hattori K. Low-dose irradiation promotes tissue revascularization through VEGF release from mast cells and MMP-9-mediated progenitor cell mobilization. J Exp Med. 2005;202:739–750. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Helisch A, Wagner S, Khan N, Drinane M, Wolfram S, Heil M, Ziegelhoeffer T, Brandt U, Pearlman JD, Swartz HM, Schaper W. Impact of mouse strain differences in innate hindlimb collateral vasculature. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:520–526. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000202677.55012.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hershey JC, Baskin EP, Glass JD, Hartman HA, Gilberto DB, Rogers IT, Cook JJ. Revascularization in the rabbit hindlimb: dissociation between capillary sprouting and arteriogenesis. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;49:618–625. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00232-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hester RL, Hammer LW. Venular-arteriolar communication in the regulation of blood flow. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;282:R1280–R1285. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00744.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hobeika MJ, Edlin RS, Muhs BE, Sadek M, Gagne PJ. Matrix metalloproteinases in critical limb ischemia. J Surg Res. 2008;149:148–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoefer IE, Grundmann S, van Royen N, Voskuil M, Schirmer SH, Ulusans S, Bode C, Buschmann IR, Piek JJ. Leukocyte subpopulations and arteriogenesis: specific role of monocytes, lymphocytes and granulocytes. Atherosclerosis. 2005;181:285–293. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hoefer IE, van Royen N, Rectenwald JE, Deindl E, Hua J, Jost M, Grundmann S, Voskuil M, Ozaki CK, Piek JJ, Buschmann IR. Arteriogenesis proceeds via ICAM-1/Mac-1- mediated mechanisms. Circ Res. 2004;94:1179–1185. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000126922.18222.F0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hoenig MR, Bianchi C, Sellke FW. Hypoxia inducible factor-1 alpha, endothelial progenitor cells, monocytes, cardiovascular risk, wound healing, cobalt and hydralazine: a unifying hypothesis. Curr Drug Targets. 2008;9:422–435. doi: 10.2174/138945008784221215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hur J, Yang HM, Yoon CH, Lee CS, Park KW, Kim JH, Kim TY, Kim JY, Kang HJ, Chae IH, Oh BH, Park YB, Kim HS. Identification of a novel role of T cells in postnatal vasculogenesis: characterization of endothelial progenitor cell colonies. Circulation. 2007;116:1671–1682. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.694778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hur J, Yoon CH, Kim HS, Choi JH, Kang HJ, Hwang KK, Oh BH, Lee MM, Park YB. Characterization of two types of endothelial progenitor cells and their different contributions to neovasculogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:288–293. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000114236.77009.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ince H, Petzsch M, Kleine HD, Eckard H, Rehders T, Burska D, Kische S, Freund M, Nienaber CA. Prevention of left ventricular remodeling with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor after acute myocardial infarction: final 1-year results of the Front-Integrated Revascularization and Stem Cell Liberation in Evolving Acute Myocardial Infarction by Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor (FIRSTLINE-AMI) Trial. Circulation. 2005;112:I73–I80. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.524827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ito WD. The Role of Monocytes/Macrophages and Vascular Resident Precursor Cells in Collateral Growth. In: Deindl E, Kupatt C, editors. Therapeutic Neovascularization–Quo Vadis? Springer; Netherlands: 2007. pp. 227–55. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ito WD, Arras M, Scholz D, Winkler B, Htun P, Schaper W. Angiogenesis but not collateral growth is associated with ischemia after femoral artery occlusion. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H1255–H1265. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.3.H1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]