Abstract

Background and objectives: Antibiotic locks in catheter-dependent chronic hemodialysis patients reduce the rate of catheter-related blood stream infections (CRIs), but there are no data regarding the long-term consequences of this practice.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: Over a 4-year period, from October 1, 2002, to September 30, 2006, we initiated a gentamicin and heparin lock (GHL) protocol in 1410 chronic hemodialysis patients receiving dialysis through a tunneled catheter in eight outpatient units.

Results: Within the first year of the GHL protocol, our CRI rate decreased from 17 to 0.83 events per 1000 catheter-days. Beginning 6 months after initiation of the GHL protocol, febrile episodes occurred in 13 patients with coagulase-negative Staphylococcus bacteremia resistant to gentamicin. Over the 4 years of GHL use, an additional 10 patients developed 11 episodes of gentamicin-resistant CRI (including 7 with Enterococcus faecalis), in which there were 4 deaths, 2 cases of septic shock requiring intensive care unit admission, and 4 cases of endocarditis. Because of these events, the GHL protocol was discontinued at the end of 2006.

Conclusions: Although the use of GHL effectively lowered the CRI rate in our dialysis population, gentamicin-resistant CRIs emerged within 6 months. Gentamicin-resistant infections are a serious complication of the long-term use of GHLs. Alternative nonantibiotic catheter locks may be preferable to decrease the incidence of CRIs without inducing resistant pathogens.

The use of tunneled central venous catheters (TCCs) for vascular access in chronic hemodialysis patients increased from 18% in 1998 to 27% in 2004 (1). Moreover, the current use of TCC can be as high as 30 to 40% in prevalent patients and 74% in incident patients (2). Although providing life-saving therapy to those awaiting maturation or placement of an arteriovenous (AV) fistula or graft, there is a 2- to 3-fold increased risk of death and a 10- to 20-fold higher risk of bacteremia in patients receiving hemodialysis through a TCC compared with a fistula (2–4).

The incidence of catheter-related blood stream infections (CRIs) in hemodialysis patients ranges from 2.5 to 5.5 cases per 1000 catheter-days. Ten to 20% of CRIs are associated with metastatic complications such as endocarditis, septic arthritis, and epidural abscess, and they cause considerable financial and physical burdens from catheter loss, repeated access procedures, and hospital admissions (3).

Numerous randomized, controlled trials (5–20), as well as meta-analyses of these studies (21–25), have been performed during the past decade to evaluate the benefit of anti-microbial lock solutions in chronic hemodialysis patients with TCCs. These studies have been heterogeneous in nature and used different antibiotics (gentamicin, minocycline, cefazolin, cefotaxime, vancomycin) and nonantibiotic (citrate, taurolidine, EDTA) anti-microbial lock solutions; however, they have all shown a significant decline of 50 to 100% in CRIs compared with standard heparin lock without antibiotics or other sterilizing solutions (3). None of the aforementioned studies have reported anti-microbial resistance or loss of anti-microbial lock solution efficacy, but the longest follow-up period has only been 547 days in one study (13). Therefore, the emergence of bacterial antibiotic resistance from anti-microbial lock solutions and its potential complications remain to be determined.

The main objectives of our study were to assess the long-term consequences of a gentamicin and heparin lock (GHL) protocol in maintenance hemodialysis patients using a TCC and to document the associated emergence of gentamicin-resistant bacteremia in these patients.

Materials and Methods

The institutional review board of Baystate Medical Center and Fresenius Medical Care-North America (Waltham, MA) approved this study. A retrospective chart review using deidentified data was performed in all adults treated with maintenance hemodialysis through a TCC for any time from October 1, 2002 to September 30, 2006 in eight Fresenius Medical Care-owned outpatient dialysis units. The start date of our data collection period coincided with the initiation of the GHL lock protocol in all eight dialysis units. The end study date was chosen as the time when the GHL protocol was discontinued because of the emergence of gentamicin-resistant bacteremias in our patients. A GHL protocol was used in all dialysis patients using a TCC during this period unless there was a known allergy or contraindication to one of the medications.

Hemodialysis Protocol and Catheter Care

Tunneled catheters were primarily either Quinton Permcaths (Kendall, Mansfield, MA) or Tesio catheters (Medcomp, Harleysville, PA), whereas a few patients had the LifeSite (VASCA, Tewksbury, MA). All tunneled catheters were placed by one of four credentialed transplant surgeons under sterile conditions in an operating room setting. Usual TCC care in the outpatient dialysis setting was performed by a protocol described in the Fresenius Medical Care-North America (FMCNA) hemodialysis procedure manual (26–28). Using clean technique with handwashing, nonsterile gloves, masking of both nurse and patient, and a nonsterile towel draped under the catheter, the nursing staff disinfected the connection ports using two gauze sponges soaked with aqueous-based povidine-iodine solution for 5 minutes. The gauze was removed, and the solution was allowed to dry before the catheter was opened. TCCs were not used for any other purpose than for dialysis access. Exit site care was performed during the intradialytic period and consisted of inspection of the catheter exit site, cleansing with povidine-iodine, and placement of a sterile dry gauze dressing. Mupirocin ointment was applied to the TCC exit site before placement of the dry gauze dressing for all patients during each dialysis treatment throughout the study period.

GHL Protocol

A GHL was administered to all outpatient hemodialysis patients using a TCC beginning in October 2002. A standard protocol was implemented where gentamicin and heparin were mixed by a specified dialysis nurse to a final concentration consisting of gentamicin (4 mg/ml) and heparin (5000 units/ml). The choice of final gentamicin dose was based on in vitro evidence indicating that supraphysiologic drug concentrations (100- to 1000-fold higher than therapeutic plasma drug levels) are needed to eradicate biofilm organisms, whereas higher concentrations can be associated with systemic toxicity (5,29). The GHL was administered into the dialysis catheter by syringe at the end of each dialysis session. The total volume administered was equal to that of the tunneled catheter lumens. The GHL was fully aspirated by a nurse or technician at the beginning of the next dialysis treatment.

Definition of CRIs

A CRI was suspected in any dialysis patient with a TCC developing a fever (T > 38°C) or chills. One set of blood cultures was drawn by aseptic technique from the arterial port of the hemodialysis circuit and repeated 20 to 30 minutes later. The decision to initiate empiric antibiotics was at the discretion of the covering nephrologist. When empiric antibiotics were chosen, they would include intravenous vancomycin and either intravenous levofloxacin or gentamicin. Peripheral blood cultures were generally not drawn in our population because of difficulty with peripheral vein access and/or desire to preserve potential vascular access sites. Blood cultures were analyzed at an outside laboratory (Spectra Laboratories, Rockleigh, NJ) or at Baystate Medical Center if the patient developed signs or symptoms of infection requiring emergency department or inpatient evaluation. A CRI was defined as at least one positive blood culture in a patient with a TCC, clinical signs of infection, and compelling evidence of the catheter as the only source. This outpatient definition of CRI has been recommended by Allon (30) and has been used in numerous anti-microbial lock solution trials.

If a febrile patient started on empiric antibiotics was found to have positive blood cultures, antibiotics were adjusted based on the culture sensitivities and continued for a total of 14 days (unless systemic complications developed, wherein intravenous antibiotics were administered for 6 weeks). The GHL was continued throughout this time period. The decision to remove a TCC was not standardized by a set protocol but was based on the discretion of the treating nephrologist. In general, a TCC was removed if a patient remained febrile after 48 hours of empiric antibiotics, had evidence of clinical deterioration while on antibiotics, had evidence of a tunnel infection, or had a relapse of an infection with the same micro-organism.

Clearance of CRI was defined by two sets of negative blood cultures in an afebrile patient without signs or symptoms of active infection. Blood cultures were routinely drawn at the completion of systemic antibiotics.

Statistical Analyses

Mean and percentage values were used to summarize baseline characteristics and outcome data. χ2 tests were used to compare proportions. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The total number of maintenance hemodialysis patients in our eight outpatient units during the study period (October 1, 2002 to September 30, 2006) was 1863 patients. Of this group, 1410 patients received dialysis through a TCC with associated GHL for at least 1 day during the study period, for a total of 142,365 catheter-days.

CRI Incidence

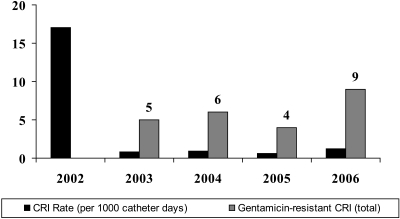

GHL lowered the total rate of CRI during the study period by 95% from an initial very high level of 17 CRI per 1000 catheter-days to 0.83 CRI per 1000 catheter-days at the end of year 1 and 1.2 CRI per 1000 catheter-days during the fourth year of the study.

Outpatient Unit Bacteremia Data

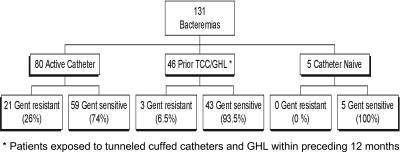

For all patients receiving hemodialysis during the 4-year study period (TCC and AV access), there were 131 episodes of bacteremia in 113 patients (63 men and 50 women). Eighty of the 131 bacteremias developed in patients with active TCCs, as summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Total bacteremias from October 2002 to September 2006. *Patients exposed to TCCs and GHL within the preceding 6 months.

A total of 121 Gram-positive bacteria (including 48 Staphylococcus aureus, 37 coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, and 17 Enterococcus faecalis) and 17 Gram-negative organisms were identified by blood culture and are listed in Table 1. Seven patients had polymicrobial bacteremias during the study period (none of which occurred in TCC patients).

Table 1.

Microbiological data of all dialysis bacteremias: 2002–2006

| Bacteria | Total | Gentamicin Resistant |

|---|---|---|

| Gram positive | ||

| Brevibacterium | 1 | 1 |

| CoNS | 37 | 13 |

| Corynebacterium | 1 | 0 |

| E. faecalis | 19 | 7 |

| Micrococcus | 2 | 0 |

| Staph aureus | 48 | 1 |

| Strep spp. | 13 | 2 |

| Total | 121 | 24 |

| Gram negative | ||

| Alcaligenes faecalis | 1 | 0 |

| Citrobacter spp. | 2 | 0 |

| Enterobacter | 2 | 0 |

| E. coli | 5 | 0 |

| Klebsiella | 3 | 0 |

| Proteus | 2 | 0 |

| Serratia | 2 | 0 |

| Total | 17 | 0 |

| Total bacteria | 138 | 24 |

Gentamicin-Resistant Bacteremias

The emergence of gentamicin-resistant CRI was first noted in March 2003, 6 months after the initiation of the GHL protocol. A total of 23 patients ultimately developed 24 gentamicin-resistant CRIs. The total number of gentamicin-resistant infections per year compared with the overall decline in CRI rate is shown in Figure 2. Gentamicin resistance was observed in 26% (21 episodes) of the 80 catheter-associated bacteremias and in 6.5% (3 episodes) of the 46 AV access patients that had been exposed to a TCC and GHL (Figure 1) in the preceding 12 months (P = 0.021). Five catheter-naïve patients developed bacteremias during the study period, but none were gentamicin resistant. The demographics of the 23 patients with gentamicin-resistant bacteremia are listed in Table 2.

Figure 2.

CRI rates and cases of gentamicin resistance.

Table 2.

Demographics of patients with gentamicin-resistant bacteremias

| Characteristics | n = 23 (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years; mean) | 55.2 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 14 (61) |

| Female | 9 (39) |

| Race or ethnic group | |

| White | 15 (65) |

| Hispanic | 5 (22) |

| Black | 3 (13) |

| Etiology of ESRD | |

| Diabetic nephropathy | 10 (43) |

| Focal segmental sclerosisa | 4 (17) |

| HIV nephropathy | 3 (13) |

| Hypertensive nephrosclerosis | 3 (13) |

| Chronic interstitial nephritis | 3 (13) |

| Otherb | 5 (2) |

| Comordid conditions | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 12 (52) |

| Chronic skin wounds | 9 (39) |

| Coronary artery disease | 8 (35) |

| Endocarditis history | 4 (17) |

| HIV | 3 (13) |

| Intravenous drug use history | 3 (13) |

| Chronic immunosuppression | 2 (9) |

| Time on hemodialysis (days; mean) | 781.5 |

Primary (1), reflux (1), and congenital (1).

Ischemic nephropathy (2), multiple myeloma (1), vasculitis (1), and scleroderma (1).

Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus was the most common cause of gentamicin-resistant CRIs (13 patients) in patients with or without a TCC during the 4-year study period (Table 3). Of these, 12 patients had a TCC and only one had an AV access. This latter individual had been exposed to a TCC and GHL within the preceding 12 months.

Table 3.

2003–2006 Coagulase-Negative Staphylococcus Bacteremias (37)

| With Catheter | Without Catheter | |

|---|---|---|

| Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus infections | 30 | 7 |

| Gentamicin-resistant infections | 12 | 1 |

Characteristics of and complications of gentamicin-resistant CRIs are shown in Table 4. Gentamicin-resistant Enterococcus bacteremia was first noted 18 months after initiation of our GHL protocol and was eventually diagnosed in seven patients. Six of the seven patients required hospitalization with two cases of sepsis, three cases of endovascular vegetation (two cases of subacute bacteria endocarditis and one case of vegetation noted on an ulcerated plaque of the aortic arch), and two deaths.

Table 4.

Characteristics of gentamicin-resistant bacteremias

| Patient Characteristics | n = 24 (%) |

|---|---|

| Duration of GHL (days; mean) | 297.5 |

| Prior parenteral aminoglycoside exposure | 4 (17) |

| Gentamicin-resistant pathogen | |

| Coagulase-negative staph | 13 (54) |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 7 (29) |

| Streptococcus species | 2 (8) |

| Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | 1 (4) |

| Brevibacterium species | 1 (4) |

| Complications | |

| Catheter removed | 12 (50) |

| Endovascular infectiona | 5 (21) |

| Sepsis | 4 (17) |

| Hospital admission | 10 (42) |

| Intensive care unit admission | 2 (8) |

| Death within 60 days | 4 (17) |

| Length of hospital stay (days; mean) | 9.7 |

Four cases of subacute bacterial endocarditis and one case of aortic arch thrombus.

Gentamicin-resistant bacteremias resulted in the removal of 12 TCCs. Ten of our patients required hospitalization for a mean of 9.7 days, with two patients requiring intensive care unit admission for septic shock. Ultimately, five patients developed either subacute bacterial endocarditis or endovascular infection involving the aortic arch, and four patients died within 60 days of documented gentamicin-resistant bacteremias (three from sepsis and one from myocardial infarction). Gentamicin-resistant bacterial isolates and the outcome results of these 25 patients are summarized in Table 4.

Discussion

During the 4-year period that we used a GHL, we noted a significant 95% decrease in the rate of catheter-related bloodstream infections in our chronic hemodialysis patients, which supports earlier studies of the anti-bacterial efficacy of GHL solutions (5,6,11,12,14–17). Moreover, the 4-year duration of our GHL treatment is the longest yet reported and shows that a decrease in CRIs with GHL solution can be sustained for years.

The most troubling finding from our study was the emergence of gentamicin-resistant gram-positive infections during the period of GHL exposure. Thirteen of our patients developed bacteremia with gentamicin-resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococcus. We did not find gentamicin-resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococcus bacteremia in our dialysis patients without TCCs (except for one patient with an arteriovenous graft that had been exposed to GHL within the last 12 months who developed gentamicin-resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococcus). The first report of antibiotic resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococcus in dialysis patients was described in a French dialysis study in 2004, but the study was only published as an abstract, and it had a much shorter duration of GHL use than our study (31). In this study, 100% of surveillance cultures positive for Staphylococcus epidermidis were resistant to gentamicin, methicillin, and quinolones after 2 years of GHL exposure, but there were no reports of clinical bacteremias. Resistance levels dropped dramatically 18 months after discontinuation of the GHL protocol.

A single-center observational study from New Zealand found a trend toward increasing gentamicin resistance among coagulase-negative Staphylococci isolated from hemodialysis patients with a TCC receiving a GHL (20). However, a similar pattern of gentamicin-resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococcus bacteremia was simultaneously found in their general hemodialysis population without TCC-associated infection. In addition, the gentamicin concentration used in their lock solution (1 mg/dl) was lower than doses previously deemed to be effective in preventing CRI and may have actually induced antibiotic resistance while not resulting in a significant decrease in the prevalent CRI rate (20).

We first noted coagulase-negative Staphylococcus and Streptococcus veridans resistant to gentamicin 6 months into the GHL protocol. Resistant Enterococcus infections began 18 months after our GHL protocol was initiated and increased from two cases in 2004 to four cases in 2006. The lengthy duration of antibiotic lock exposure (average of 297.5 days) and the 4-year follow-up in our study has allowed us to observe these novel findings.

Gentamicin-resistant bacteremia was associated with significant morbidity in our patients, particularly in the seven patients with Enterococcus faecalis CRIs. Overall, 24 episodes of gentamicin-resistant bacteremia led to 10 inpatient admissions, loss of TCCs in 12 patients, subacute bacterial endocarditis and/or sepsis in 7 patients, and 4 deaths (3 from sepsis and 1 from myocardial infarction).

Our study has weaknesses associated with any uncontrolled, retrospective study. Although our data showed evidence for the development of gentamicin resistance from the use of GHL, it is difficult to establish causality. The CRI rate at the onset of our study was also very high compared with reported rates in the literature. This raises the question of whether similar rates of antibiotic resistance would be found in units with lower baseline CRI rates. We did not collect data regarding catheter vintage or specifically provide catheter management (e.g., catheter removal in CRI) by a set protocol during the study period. Another limitation was our inability to obtain baseline gentamicin resistance data in our dialysis population because gentamicin sensitivities were not routinely tested by our outpatient laboratory until October 2002. Some strengths of our study are that it was multicentered, included more patients and catheter days than most of the meta-analyses, and provided observation of the GHL process over a longer period (4 year) than previously reported (20–24).

The use of an alternative, nonantibiotic, catheter lock is a possible solution to prevent CRI in chronic hemodialysis patients with a TCC. Unfortunately, currently available alternative locks all have ongoing questions and concerns beyond their rather limited study data. Taurolidine with 4% sodium citrate has been shown to be effective in several studies but may be associated with an increase in catheter thrombosis and is not currently available in the United States (7,32,33). High-dose citrate (30 to 47%) has been well studied but is complicated by the rare but fatal risk of hypocalcemia that led to the FDA's recall of 47% citrate in 2000 (3,9). Weijmer et al. (9) have shown a reduction in CRI and CRI-related mortality using 30% trisodium citrate; however, recent studies by Power et al. (34) and Venditto et al. (35) did not show a benefit in lowering the catheter-related bacteremia rate when using 47% sodium citrate compared with 5% heparin. Ethanol locks (with or without sodium citrate) seem to show benefit in the prevention of infection in certain types of central catheters, but their long-term compatibility with polyurethane-based catheters is still in question (36,37). Low-dose citrate with methylene blue and parabens (Zuragen; Ash Access Technology) has also been studied in the laboratory and in a clinical trial (Assessing Zuragen Efficacy and Safety in the Prevention and Treatment of Infections in Catheters trial) with promising results (38,39).

Conclusions

Our study suggests that the long-term use of a GHL protocol decreases the rate of CRIs in hemodialysis patients with a TCC but is also associated with the undesirable consequences of the emergence of gentamicin-resistant gram-positive bacteremias that developed as early as 6 months after GHL use. The need to safely reduce the incidence of CRIs without inducing the emergence of resistant bacteria must await further studies of alternative nonantibiotic catheter lock solutions. In the interim, the crucial issue is whether the benefit of a significant decrease in the incidence of catheter-associated bacteremias with gentamicin lock in hemodialysis patients outweighs the risk of the emergence of antibiotic resistant bacteremia in these patients.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

This study was presented in part at both the National Kidney Foundation Spring clinical meeting (March 25–29, 2009; Nashville, TN) and the American Society of Nephrology Fall clinical meeting (October 29-September 1, 2009; San Diego, CA). We thank Jean Dowd, RN, and Tamara Bissaillon, RN, for invaluable research support.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: 2004 Annual report: End-stage renal disease clinical performance measures project. Am J Kidney Dis 46: 1–100, 2005. 15983951 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vascular Access Working Group: Clinical practice guidelines for vascular access. Am J Kidney Dis 48[Suppl 1]: S248–S273, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allon M: Dialysis catheter-related bacteremia: Treatment and prophylaxis. Am J Kidney Dis 44: 779–791, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allon M, Depner TA, Radeva M, Bailey J, Beddhu S, Butterly D, Coyne DW, Gassman JJ, Kaufman AM, Kaysen GA, Lewis JA, Schwab SJ: Impact of dialysis dose and membrane on infection-related hospitalization and death: Results of the HEMO study. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 1863–1870, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dogra GK, Herson H, Hutchison B, Irish AB, Heath CH, Golledge C, Luxton G, Moody H: Prevention of tunneled haemodialysis catheter-related infections using catheter-restricted gentamicin and citrate: A randomized controlled study. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 2133–2139, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McIntyre CW, Hulme LJ, Taal M, Fluck RJ: Locking of tunneled haemodialysis catheters with gentamicin and heparin. Kidney Int 66: 801–805, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Betjes MG, van Agteren M: Prevention of dialysis catheter-related sepsis with a citrate-taurolidine-containing lock solution. Nephrol Dial Transplant 19: 1546–1551, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bleyer AJ, Mason L, Russell G, Raad II, Sherertz RJ: A randomized, controlled trial of a new vascular catheter flush solution (minocycline-EDTA) in temporary haemodialysis access. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 26: 520–524, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weijmer MC, van den Dorpel MA, Van de Ven PJ, ter Wee PM, van Geelen JA, Groeneveld JO, van Jaarsveld BC, Koopmans MG, le Poole CY, Schrander-Van der Meer AM, Siegert CE: Randomised, clinical trial comparison of trisodium citrate 30% and heparin as catheter-locking solution in haemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 2769–2777, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saxena AK, Panhotra BR: The impact of catheter-restricted filling with cefotaxime and heparin on the lifespan of temporary haemodialysis catheters: A case controlled study. J Nephrol 18: 755–763, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nori US, Manoharan A, Yee J, Besarab A: Comparison of low-dose gentamicin with minocycline as catéter lock solutions in the prevention of catre-related bacteraemia. Am J Kidney Dis 48: 596–605, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim SH, Song KI, Chang JW, Kim SB, Sung SA, Jo SK, Cho WY, Kim HK: Prevention of uncuffed haemodialysis catheter-related bacteraemia using an antibiotic lock technique: A prospective, randomized clinical trial. Kidney Int 69: 161–164, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saxena AK, Panhotra BR, Sundaram DS, Al-Hafiz A, Naguib M, Venkateshappa CK, Abu-Oun BA, Hussain SM, Al-Ghamdi AA: Tunneled catheters' outcome optimization among diabetics on dialysis through antibiotic-lock placement. Kidney Int 70: 1629–1635, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Hwiesh AK, Abdul-Rahman ISA: Successful prevention of tunneled, central catheter infection by antibiotic lock therapy using vancomycin and gentamicin. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transplant 18: 239–247, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang P, Yuan J, Tan H, Lv R, Chen J: Successful prevention of cuffed hemodialysis catheter-related infection using an antibiotic lock solution method. Blood Purif 27: 206–211, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooper RI, Saad TF: Prevention of bacteremia in patients with tunneled cuffed ‘permanent’ hemodialysis catheters using gentamicin catheter packing. J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 203A, 1999. 10215318 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pervez A, Ahmed M, Ram S, Torres C, Work J, Zaman F, Abreo K: Antibiotic lock technique for prevention of cuffed tunnel catheter associated bacteremia. J Vasc Access 3: 108–113, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duncan N, Singh S, Amao M: A single centre randomized control trial of sodium citrate versus heparin line locks for cuffed central venous cathets. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 451A, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hendricks L, Kuypers D, Evenepoel P, Maes B, Messiaen T, Vanrenterghem Y: A comparative prospective study on the use of low concentrate citrate lock versus heparin lock in permanent dialysis catheters. Int J Artif Organs 24: 208–211, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abbas SA, Haloob IA, Taylor SL, Curry EM, King BB, Van der Merwe WM, Marshall MR: Effect of anti-microbial locks for tunneled hemodialysis catheters on bloodstream infection and bacterial resistance: A quality improvement report. Am J Kidney Dis 53: 492–502, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Labriola L, Crott R, Jadoul M: Preventing haemodialysis catheter-related bacteraemia with an anti-microbial lock solution: A meta-analysis of prospective randomized trials. Nephrol Dial Tranplant 23: 1666–1672, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaffer Y, Selby N, Taal M, Fluck R, McIntyre CW: A meta-analysis of haemodialysis catheter locking solutions in the prevention of catheter related infection. Am J Kidney Dis 51: 233–241, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yahav D, Rozen-Zvi B, Gafter-Gvili A, Leibovici L, Gafter U, Paul M: Anti-microbial lock solutions for the prevention of infections associated with intravascular catheters in patients undergoing hemodialysis: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis 47: 83–93, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.James MT, Conley J, Tonelli M, Manns BJ, MacRae J, Hemmelgarn BR: Meta-analysis: Antibiotics for prophylaxis against hemodialysis catheter-related infections. Ann Intern Med 148: 596–605, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rabindranath KS, Bansal T, Adams J, Das R, Shail R, Macleod AM, Moore C, Besarab A: Systematic review of anti-microbials for the prevention of haemodialysis catheter-related infections. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 3763–3774, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fresenius Medical Care North America: Hemodialysis Procedure Manual. Central Venous Catheter Training Manual: Initiating Treatment Using a Catheter (#132-020-265), Waltham, MA, Fresenius, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fresenius Medical Care North America: Hemodialysis Procedure Manual. Central Venous Catheter Training Manual Part I: Disinfection of Connection Ports of Catheter (#136-020-130), Waltham, MA, Fresenius, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fresenius Medical Care North America: Hemodialysis Procedure Manual. Central Venous Catheter Training Manual Part II: Catheter Care (#136-020-245), Waltham, MA, Fresenius, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ceri H, Olson ME, Stremick C, Read RR, Morck D, Buret A: The Calgary biofilm device: New technology for rapid determination of antibiotic susceptibilities of bacterial biofilms. J Clin Microbiol 37: 1771–1776, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allon M: Treatment guidelines for dialysis catheter-related bacteremia: An update. Am J Kidney Dis 54: 13–17, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guerraoiu AA, Dacosta EE, Roche BB, Plaidy AA, Laroussinie GG, Didier DA, Deteix PP: Emergence of multiresistant Staphylococcus epidermidis (MRSE) after lock antibiotic regimen by gentamicin in permanent hemodialysis catheters. Prospective study, 1999–2003. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 368A, 2004(Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geron R, Tanchilevsky O, Kristal B: Catheter lock solution: Taurolock for the prevention of catheter-related bacteremia in hemodialysis patients. Harefuah 145: 881–884, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor C, Cahill J, Gerrish M, Little J: A new haemodialysis catheter-locking agent reduces infections in haemodialysis patients. J Renal Care 34: 116–120, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Power A, Duncan N, Singh SK, Brown W, Dalby E, Edwards C, Lynch K, Prout V, Cairns T, Griffith M, McLean A, Palmer A, Taube D: Sodium citrate versus heparin catheter locks for cuffed central venous catheters: A single-center randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis 53: 1034–1041, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vendito M, Tezenas du Montcel S, Robert J, Trystam D, Dighiero J, Hue D, Bessette C, Deray G, Mercadal L: Effect of catheter-lock solutions on catheter-related infection and inflammatory syndrome in hemodialysis patients: Heparin versus citrate 46% versus heparin/gentamicin. Blood Purif 29: 268–273, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ash SR: The evolution and function of central venous catheters for dialysis. Semin Dial 14: 416–424, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crnich CJ, Halfmann JA, Crone WC, Maki DG: The effects of prolonged ethanol exposure on the mechanical properties on polyurethane and silicone catheters used for intravascular access. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 26: 708–714, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steczko J, Ash SR, Nivens DE, Brewer L, Winger RK: Microbial inactivation properties of a new anti-microbial/antithrombotic lock solution (citrate/methylene blue/parabens). Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 1937–1945, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ash SR, Maki DG, Lavin PT, Winger RK: A multicenter randomized trial of an anti-microbial and antithrombotic lock solution for hemodialysis catheters. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 69–70A, 2009 [Google Scholar]