Abstract

Background and objectives: Influenza infection in transplant recipients is often associated with significant morbidity. Surveys were conducted in 1999 and 2009 to find out if the influenza vaccination practices in the U.S. transplant programs had changed over the past 10 years.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: In 1999, a survey of the 217 United Network for Organ Sharing-certified kidney and kidney-pancreas transplant centers in the U.S. was conducted regarding their influenza vaccination practice patterns. A decade later, a second similar survey of 239 transplant programs was carried out.

Results: The 2009 respondents, compared with 1999, were more likely to recommend vaccination for kidney (94.5% versus 84.4%, P = 0.02) and kidney-pancreas recipients (76.8% versus 48.5%, P < 0.001), family members of transplant recipients (52.5% versus 21.0%, P < 0.001), and medical staff caring for transplant patients (79.6% versus 40.7%, P < 0.001). Physicians and other members of the transplant team were more likely to have been vaccinated in 2009 compared with 1999 (84.2% versus 62.3% of physicians, P < 0.001 and 91.2% versus 50.3% of nonphysicians, P < 0.001).

Conclusions: Our study suggests a greater adoption of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention influenza vaccination guidelines by U.S. transplant programs in vaccinating solid-organ transplant recipients, close family contacts, and healthcare workers.

Influenza virus is a pathogen that causes significant morbidity and mortality and imposes a substantial economic burden on society. It is estimated that each year 5% of adults and 20% of children worldwide suffer symptomatic influenza infection (1). In the U.S., the annual death incidence from influenza ranges from 36,000 to 41,000 per year, and the incidence of influenza-associated hospitalization exceeds 200,000 (2–4). The average annual cost of direct medical care associated with influenza infection is estimated at $10 billion, and the total economic burden of annual influenza epidemic at $87 billion (5).

The outcome of influenza infection is determined by the virulence of the viral strain and the competence of the host’s immune system (1). Fending off an influenza virus requires functional cellular and humoral immune systems working together to mount innate and adaptive immune responses (6). Yearly influenza vaccination is the most effective way of preventing influenza infection and its complications (7). The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends influenza vaccination for all persons 50 years of age or older, all children between 6 months and 18 years of age, and persons 19 to 49 years of age who have underlying medical problems, pregnant women, all healthcare workers (HCWs) involved in direct patient care, and household contacts of high risk persons (7). These categories comprise at least 85% of the U.S. population (8). The vaccine is contraindicated only in people who have severe egg allergy or who have had a severe reaction to a prior flu vaccination such as Guillan-Barre Syndrome. In nonimmunocompromised population, influenza vaccination is effective in 70% to 90% of people when there is a good match between the vaccine antigen and the epidemic virus (7).

With medical advances in the field of transplantation, a growing population of transplant recipients are living among us. In 2008, nearly 28,000 solid organ transplants were performed in the U.S., and more than half of them were kidney transplants (9). As of 2007, there were more than 150,000 renal transplant recipients living in the U.S. (10). As their cellular and humoral arms of the immune system are affected by immunosuppressive medications, influenza infection poses a serious health threat to transplant recipients; transplant recipients who contract influenza virus, have an increased risk of complications such as viral pneumonia, secondary bacterial pneumonia, and extrapulmonary complications including myocarditis and myositis (11,12). Moreover, influenza infections in transplant recipients have been associated with allograft rejection (13) and prolonged viral shedding (14).

The guidelines for vaccination of solid organ transplant recipients published by the American Society of Transplantation (15) as well as the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO), both published in 2009, recommend annual vaccination of renal transplant recipients with inactivated influenza vaccine (16).

To understand whether transplant programs were adhering to the vaccination recommendations, our program performed two surveys. In 1999, our group conducted a survey of transplant physicians inquiring about their influenza vaccination practices (17). Ten years later, we conducted a second, similar survey of all kidney and kidney-pancreas transplant centers in the U.S., inquiring about their post-transplant management including their vaccination practices.

Materials and Methods

1999 Survey

A 15-question survey was designed to assess influenza vaccination practices (see Supplemental Appendix I). In January 1999, the questionnaire was mailed out to 301 caregivers in 217 United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS)-certified kidney and kidney/pancreas transplant centers listed in the mailing list purchased from UNOS. A reminder letter was sent to those who did not respond to the initial survey within 4 weeks.

2009 Survey

We designed a 26-question web-based survey to gather information about post-transplant medical management including vaccination practices. Of the 26 questions, the first 15 questions were identical to the 1999 survey (see Supplemental Appendix II). The survey was sent out in February, 2009, 2 months before the first reported case of H1N1 influenza outbreak. We invited 239 active transplant programs (139 kidney and kidney/pancreas, and 100 kidney only) to participate in the survey. A list of medical and surgical directors of the kidney and kidney-pancreas transplant programs was purchased again from UNOS. Because UNOS did not provide email addresses, we searched the internet to obtain the current email addresses of each medical and surgical director. We then emailed an invitation with a secured hyperlink to complete the online survey. For those who did not have an email address, an introduction letter was sent to them via facsimile. Reminders were sent to those who did not respond in 4 weeks. For those participants with email addresses who had technical difficulties completing the online survey, a survey form was faxed or emailed to them and they were asked to return the completed form back to us.

Participation in both surveys was voluntary, and financial compensation was not offered for completing the survey. In both studies, the survey participants were informed that confidentiality of data would be protected. The results from 1999 and 2009 surveys were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test.

Results

Survey Responses

In 1999, of the 301 invitees in 217 transplant programs, 167 physicians or their staff from 142 centers responded to our survey (physician response rate: 55.5%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 49.7% to 61.2%; center response rate: 65.4%; 95% CI, 58.7% to 71.7%). In 2009, of the 426 medical or surgical directors of 239 kidney and kidney/pancreas programs who were asked to participate in the study, 183 physicians or their representatives from 143 transplant centers responded to our survey (physician response rate: 43.0%; 95% CI, 38.2% to 47.8%; center response rate: 59.8%; 95% CI, 53.3% to 66.1%). Although the individual physician response rate was lower in 2009 (P ≤ 0.001), the center response rate was not significantly different (P = NS). Of the programs that participated in either survey, 84.6% (121 of 143) programs responded to both surveys, showing that the majority of the participants responded to both surveys.

Regarding the composition of the respondents, in 1999, 47.0% (95% CI, 39.1% to 54.8%) of the respondents were surgeons, 31.1% (95% CI, 24.1% to 38.8%) were transplant nephrologists, and 21.9% (95% CI, 15.9% to 29.0%) were nurse coordinators, nurse practitioners, or other healthcare professionals. Three respondents were excluded from our calculation, as they did not answer the question regarding their role in the transplant program. In 2009, 41.0% (95% CI, 33.8% to 48.5%) of the respondents were surgeons, 56.3% (95% CI, 48.7% to 63.6%) were transplant nephrologists, and 2.7% (95% CI, 0.9% to 6.2%) were non-MD healthcare professionals. Although a higher percentage of respondents was comprised of surgeons in 1999 (47.0% versus 41.0% in 2009), the ratio of surgeon versus nonsurgeons for both surveys were not statistically different (P = NS).

Influenza Vaccination Policy

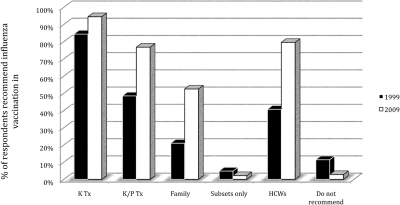

Over the last decade, more transplant programs have adopted influenza vaccination for their kidney and kidney/pancreas transplant recipients. The survey results from 2009 showed that 171 out of 181 respondents recommended influenza vaccination for kidney transplant recipients (94.5%; 95% CI, 90.0% to 97.3% versus 84.4%; 95% CI, 78.0% to 89.5% in 1999, P = 0.002). Statistically significant differences were also seen in the percentage of respondents who recommended influenza vaccination in kidney-pancreas transplant recipients (76.8%; 95% CI, 69.9% to 82.7% versus 48.5%; 95% CI, 40.7% to 56.3% in 1999, P < 0.001), in family members of transplant recipients (52.5%; 95% CI, 44.9% to 59.9% versus 21.0%; 95% CI, 15.0% to 27.9% in 1999, P < 0.001), and in medical staff caring for transplant patients (79.6%; 95% CI, 72.9% to 85.2% versus 40.7%; 95% CI, 33.2% to 48.6% in 1999, P < 0.001). Only five out of 181 respondents did not recommend influenza vaccination to anyone (2.8%; 95% CI, 1.2% to 7.0% versus 11.4%; 95% CI, 6.9% to 17.2% in 1999, P = 0.004) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Influenza vaccination recommended for the above groups (1999 versus 2009). HCW, healthcare workers; Subsets, subset of patients who have specific underlying conditions.

The survey also revealed that a significantly greater percentage of respondents would recommend other HCWs to vaccinate their patients (94.3%; 95% CI, 89.7% to 97.2% versus 77.6%; 95% CI, 70.1% to 83.9%, P < 0.001).

Similar results were found when the participants were asked about vaccinations for physicians and other members of the transplant team. A significantly greater proportion of respondents were vaccinated against influenza in 2009 (84.7%; 95% CI, 78.0% to 89.1% versus 62.3%; 95% CI, 54.4% to 69.6% in 1999, P < 0.001). Moreover, the increase in influenza vaccination was also observed in non-MD HCWs (e.g., social workers, nurse coordinators, etc.) in 2009 (91.2%; 95% CI, 86.1% to 94.9% versus 50.3%; 95% CI, 42.5% to 58.1% in 1999, P < 0.001).

The changes in the influenza vaccination practices seen in the survey were still present when the analysis was restricted to the centers that participated in both surveys (88 out of 143 programs). Seventy-three of the programs (83.0%) recommended influenza vaccination of the transplant recipients in 1999, whereas 85 of them (96.6%) did in 2009. Vaccination of medical staff was recommended in 30 programs in 1999 (34.1%) and in 72 programs in 2009 (81.8%). Eleven programs (12.5%) recommended vaccinating close family contacts in 1999, whereas 48 programs (54.5%) did in 2009. The P values for Fisher exact test for kidney transplant recipients, medical staff, and close family contacts were 0.005, <0.001, and <0.001, respectively.

A subgroup analysis looking at the influenza vaccination rates for the surgeons and nonsurgeons showed a higher percentage of surgeons were getting vaccinated in 2009 compared with 1999 (78.7%; 95% CI, 67.7% to 87.3% versus 50.6%; 95% CI, 39.0% to 62.2%, P < 0.001). Similarly, the vaccination rate for nonsurgeons in 2009 was higher than that documented in 1999, but this difference did not reach a statistical significance (88.9%; 95% CI, 81.4% to 94.1% versus 77.0%; 95% CI, 69.9% to 86.9%, P = 0.082).

Morbidity and Mortality from Influenza Infection

Significant morbidity (hospitalization, pneumonia, acute kidney injury) or mortality was reported by 22 out of 167 physicians in 1999 and by 36 out of 179 respondents in 2009 (13.2%; 95% CI, 8.4% to 19.3% versus 20.1%; 95% CI, 14.5% to 26.7%, P = 0.113) showing no significant difference between the two time periods.

Adverse Reactions

We asked the question whether any adverse reactions attributable to the vaccines were observed. Twenty-three out of 167 respondents answered yes in 1999, whereas 41 out of 180 physicians did so in 2009 (13.8%; 95% CI, 8.9% to 19.9% versus 22.8%; 95% CI, 16.8% to 29.6%, P = 0.04). Although one in four respondents reported adverse reactions in 2009, the majority (94.4%) of adverse reactions were flu-like symptoms. However, acute rejection was reported as an adverse reaction from influenza vaccine in nine out 22 in 1999 versus five out of 36 in 2009 (40.9%; 95% CI, 20.7% to 63.6% versus 13.9%; 95% CI, 4.6% to 29.5%, P = 0.03).

Reasons for Not Giving the Vaccine

When asked about reasons for not giving the influenza vaccine, lack of efficacy of the vaccine was most frequently mentioned in both surveys (65%; 95% CI, 40.8% to 84.6% in 1999 and 63.6%; 95% CI, 30.8% to 89.0% in 2009). Nine out of 20 responses noted rejection in 1999; only two out of 11 responses indicated acute rejection in 2009 (Table 1). Multiple responses were allowed for this question accounting for the discrepancy in the size of the denominator when compared with the number of centers not recommending the vaccination.

Table 1.

Reasons for not giving the vaccine (multiple responses allowed)

| 1999 | 2009 | Fisher Exact TestPValue | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of efficacy | 13/20 (65%) | 7/11 (63.6%) | P > 0.20 |

| Safety concerns | 6/20 (30%) | 3/11 (27.3%) | P > 0.20 |

| Adverse reactions | 4/20 (20%) | 2/11 (18.2%) | P > 0.20 |

| Concern for acute rejection | 9/20 (45%) | 2/11 (18.2%) | P > 0.20 |

| Vaccine availability | 0/20 (0%) | 0/11 (0%) | P > 0.20 |

| Cost/reimbursement | 1/20 (5%) | 1/11 (9.1%) | P > 0.20 |

| Do not believe in vaccines | 1/20 (5%) | 2/11 (18.2%) | P > 0.20 |

| Other | 3/20 (15%) | 0/11 (0%) | P > 0.20 |

Timing of Influenza Vaccination in Post-transplant Patients

Although the 1999 survey did not ask about the timing of influenza vaccination, our 2009 survey included a question about it. The majority of the respondents began post-transplant vaccination within the first 6 months (41.8%; 95% CI, 33.8% to 50.7% in <3 months and 42.6%; 95% CI, 34.5% to 51.5% in 3 to 6 months) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Initiation of influenza vaccination post-transplant in 2009 (n = 140)

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| <3 months | 59/140 | 41.8% |

| 3 to 6 months | 60/140 | 42.6% |

| >6 to 12 months | 18/140 | 12.8% |

| >12 months | 4/140 | 2.8% |

Number of Patients Getting Vaccinated Annually

The majority of transplant programs vaccinated less than 100 patients per year in 1999 and 2009 (62.3%; 95% CI, 48.6% to 64.0% versus 56.5%; 95% CI, 48.6% to 64.0%, P = 0.278).

Discussion

Influenza virus infection is associated with significant morbidity in transplant recipients (18). It can also trigger acute rejection in these patients; upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-2 is thought to play a role (19). Although influenza vaccination is recommended for all immunocompromised patients, including solid organ transplant recipients, our 1999 survey revealed that the transplant community had not fully embraced the influenza vaccination guidelines recommended by the CDC. Despite the fact that there is no convincing evidence that influenza vaccine causes allograft rejection (20), the theoretical concern of the vaccine creating a proinflammatory environment has kept many transplant physicians from recommending the vaccine. However, over the past decade, several prospective studies involving influenza vaccination of liver (21), heart (22), and renal (23) transplant recipients have shown neither increased incidence of acute rejection nor increased anti-HLA antibody levels after vaccination.

In 2009, we conducted another survey to detect any change in the practice patterns of U.S. transplant programs on influenza vaccination. The study was conducted in February 2009—well before the H1N1 influenza endemic—and the results were likely unaffected by the heightened alertness for influenza.

Our study is the first to report a significant change in the attitudes of U.S. transplant programs regarding influenza vaccination. A greater percentage of transplant programs in 2009 recommended influenza vaccination for transplant recipients, HCWs, and the family members compared with 1999. It is also reassuring that most survey respondents in 2009 did not report concerns of rejection or other major safety issues with influenza vaccination.

Although many more transplant programs recommended influenza vaccination in all at-risk groups, the household members of transplant recipients were the group for which it was least vigorously recommended. Even in 2009, approximately 50% of the programs recommended influenza vaccination in this group. Our finding is consistent with Lu’s analysis of the National Health Interview Survey showing a meager 21% vaccination rate in the household contacts of at-risk patients (24). As it has been shown that vaccinating family members—especially school-aged children—effectively reduces the incidence of influenza in the general population (25); family members in close contact with transplant recipients should get vaccinated to protect the latter. With only 50% of the programs currently recommending family members, there is a lot of room for improvement.

Although both of our surveys had good response rates, and the mix of transplant surgeons versus nonsurgeons who took part in them was similar, our study has several limitations. Our study suffers from all of the weaknesses that are inherent in survey-based studies, including recall bias and selection bias. In addition, the two surveys were not entirely identical in their contents and in the mode of survey delivery (postal versus electronic mail); this might have introduced additional bias. Moreover, some of the kidney-only transplant programs chose to answer the question regarding vaccination of kidney-pancreas transplant recipients negatively rather than leaving it unanswered, thereby resulting in lower recommendation rates. Our study also did not take into account the possibility of transplant recipients receiving their vaccination from their general nephrologists, primary care physicians (PCPs), or other sources.

In summary, our study suggests that the U.S. transplant programs have increasingly recognized the importance of influenza vaccination in transplant recipients. The role of nontransplant physicians—PCPs and general nephrologists—in influenza vaccination of the transplant recipients has not been studied. Studying the attitudes of nontransplant physicians on vaccinating transplant recipients and the family members and emphasizing the need to provide the transplant recipients with a ring of protection will likely help reduce influenza infection.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Supplemental information for this article is available online at http://www.cjasn.org/.

References

- 1.Nicholson KG, Wood JM, Zambon M: Influenza. Lancet 362: 1733–1745, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, Brammer L, Cox N, Anderson LJ, Fukuda K: Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. JAMA 289: 179–186, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, Brammer L, Bridges CB, Cox NJ, Fukuda K: Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States. JAMA 292: 1333–1340, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dushoff J, Plotkin JB, Viboud C, Earn DJ, Simonsen L: Mortality due to influenza in the United States—an annualized regression approach using multiple-cause mortality data. Am J Epidemiol 163: 181–187, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Molinari NA, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Messonnier ML, Thompson WW, Wortley PM, Weintraub E, Bridges CB: The annual impact of seasonal influenza in the U.S.: Measuring disease burden and costs. Vaccine 25: 5086–5096, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Couch RB, Kasel JA: Immunity to influenza in man. Annu Rev Microbiol 37: 529, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiore AE, Shay DK, Broder K, Iskander JK, Uyeki TM, Mootrey G, Bresee JS, Cox NJ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2009. MMWR Recomm Rep 58 (RR-8): 1–52, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glezen WP: Prevention and treatment of seasonal influenza. N Engl J Med 359: 2579–2585, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.2008 UNOS data. Available at: http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov Accessed October 30, 2009

- 10.U.S. Renal Data System: 2009 USRDS Annual Data Report. Atlas of End-Stage Renal Disease. Available at: http://m.usrds.org/2009/no_links/v2_04_modalities.asp Accessed June 8, 2010

- 11.Ison MG, Hayden FG: Viral infections in immunocompromised patients: What’s new with respiratory viruses? Curr Opin Infect Dis 15: 355–367, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.López-Medrano F, Aguado JM, Lizasoain M, Folgueira D, Juan RS, Díaz-Pedroche C, Lumbreras C, Morales JM, Delgado JF, Moreno-González E: Clinical implications of respiratory virus infections in solid organ transplant recipients: A prospective study. Transplantation 84: 851–856, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Briggs JD, Timbury MC, Paton AM, Bell PR: Viral infection and renal transplant rejection. BMJ 4: 520–522, 1972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weinstock DM, Gubareva LV, Zuccotti G: Prolonged viral shedding of multi-drug resistant influenza A virus in an immunocompromised patient. N Engl J Med 348: 867–868, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Danzinger-Isakov L, Kumar D, and the AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice: Guidelines for vaccination of solid organ transplant candidates and recipients. Am J Transplant 9 (Suppl 4): S258–S262, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Transplant Work Group: KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 9 (Suppl 3): S1–S155, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poduval RD, Josephson MA: Influenza vaccination practices in the transplant community. Am J Transplant 3 (Suppl 5): 300, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vilchez RA, McCurry K, Dauber J, Iacono A, Griffith B, Fung J, Kusne S: Influenza virus infection in adult solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2: 287–291, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skoner DG, Gentile DA, Patel A, Doyle WJ: Evidence of cytokine mediation of disease expression in adults experimentally infected with influenza A virus. J Inf Disease 180: 10–14, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Connolly J, Douglas J, Kumar R, Middleton D, McEvoy J, Nelson S, McGeown MG: Influenza virus vaccination and renal transplant rejection. BMJ 1: 638, 1974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawal A, Basler C, Branch A, Gutierrez J, Schwartz M, Schiano TD: Influenza vaccination in orthotopic liver transplant recipients: Absence of post administration ALT elevation. Am J Transplant 4: 1801–1809, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Magnani G, Falchetti E, Pollini G, Reggiani LB, Grigioni F, Coccolo F, Potena L, Magelli C, Sambri V, Branzi A: Safety and efficacy of two types of influenza vaccination in heart transplant recipients: A prospective randomized controlled study. J Heart Lung Transplant 24: 588–592, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Candon S, Thervet E, Lebon P, Suberbielle C, Zuber J, Lima C, Charron D, Legendre C, Chatenoud L: Humoral and cellular immune responses after influenza vaccination in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 9: 2346–2354, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu P, Bridges CB, Euler GL, Singleton JA: Influenza vaccination of recommended adult populations US, 1989–2005. Vaccine 26: 1786–1793, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.King JC, Stoddard JJ, Gaglani MJ, Moore KA, Magder L, McClure E, Rubin JD, Englund JA, Neuzil K: Effectiveness of school-based influenza vaccination. N Engl J Med 355: 2523–2532, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.