Abstract

Atrial and ventricular tachyarrhythmias can be perpetuated by up-regulation of inward rectifier potassium channels. Thus, it may be beneficial to block inward rectifier channels under conditions in which their function becomes arrhythmogenic (e.g., inherited gain-of-function mutation channelopathies, ischemia, and chronic and vagally mediated atrial fibrillation). We hypothesize that the antimalarial quinoline chloroquine exerts potent antiarrhythmic effects by interacting with the cytoplasmic domains of Kir2.1 (IK1), Kir3.1 (IKACh), or Kir6.2 (IKATP) and reducing inward rectifier potassium currents. In isolated hearts of three different mammalian species, intracoronary chloroquine perfusion reduced fibrillatory frequency (atrial or ventricular), and effectively terminated the arrhythmia with resumption of sinus rhythm. In patch-clamp experiments chloroquine blocked IK1, IKACh, and IKATP. Comparative molecular modeling and ligand docking of chloroquine in the intracellular domains of Kir2.1, Kir3.1, and Kir6.2 suggested that chloroquine blocks or reduces potassium flow by interacting with negatively charged amino acids facing the ion permeation vestibule of the channel in question. These results open a novel path toward discovering antiarrhythmic pharmacophores that target specific residues of the cytoplasmic domain of inward rectifier potassium channels.—Noujaim, S. F., Stuckey, J. A., Ponce-Balbuena, D., Ferrer-Villada, T., López-Izquierdo, A., Pandit, S., Calvo, C. J., Grzeda, K. R., Berenfeld, O., Sánchez Chapula, J. A., Jalife, J. Specific residues of the cytoplasmic domains of cardiac inward rectifier potassium channels are effective antifibrillatory targets.

Keywords: chloroquine, fibrillation, IK1, IKATP, IKACh

Inward rectifier potassium channels have been implicated in the perpetuation of reentrant tachyarrhythmias in the normal or diseased heart, in humans and in experimental models. In the ventricles, Kir2.1 is the main pore-forming protein of the inward rectifier potassium current IK1 (1), and Kir6.2 is the pore-forming subunit of the ATP-sensitive potassium current IKATP (1). In the atria, Kir3.1 and 3.4 are the pore-forming subunits of the acetylcholine-sensitive potassium current IKACh (1). Gain-of-function mutations in Kir2.1 cause an increase in IK1 and may lead to short QT syndrome type 3 and inducible ventricular arrhythmias (2), or familial atrial fibrillation (AF) (3). In addition, IK1 is up-regulated in chronic AF (4). The acetylcholine-sensitive potassium current (IKACh) is constitutively active in chronic AF (4) and is thought to underlie vagally mediated AF (5). The ATP-sensitive potassium current (IKATP) is activated during ischemia or hypoxia, increasing the susceptibility of the heart to life-threatening ventricular tachyarrhythmias (6). Although still incompletely understood, there appears to be an association between the early repolarization syndrome, increased IKATP due to a channelopathy and idiopathic ventricular fibrillation (VF) (7). Altogether, the above studies suggest that blockade of inward rectifiers under certain conditions, could offer a potentially useful antiarrhythmic strategy against ventricular and atrial tachyarrhythmias (8–10).

Structurally, inward rectifiers are closely related to each other (1). Experiments (11–13) and numerical simulations (11, 12, 14) showed that increasing inward rectifier currents (i.e., IK1, IKATP, or IKACh) hyperpolarizes the resting membrane potential and shortens the action potential duration, resulting in the stabilization and acceleration of atrial and ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation.

Chloroquine is an antimalarial quinoline that has been used extensively in the clinic (15). It was noted in the 1950s that chloroquine also possessed potent antiarrhythmic properties against ventricular and atrial tachyarrhythmias (16). However, the precise mechanism of these properties remains unknown. More recently, chloroquine was shown to block IK1 (17), IKACh (18), and pancreatic IKATP (19). In view of such studies, we tested the hypothesis that chloroquine also blocks the cardiac IKATP and that chloroquine's antiarrhythmic effects in both atria and ventricles are the consequence of its interaction with the cytoplasmic domains of inward rectifier channels.

We investigated the antifibrillatory effects of 10 μM chloroquine (chloroquine blood concentration during antimalarial treatment in humans can reach 1 to 5 μM; ref. 20) in isolated Langendorff-perfused heart models of inward rectifier-mediated arrhythmias in three different mammalian species. We have used a mouse model of ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation (VT/VF) secondary to Kir2.1 up-regulation (17), a rabbit model of VF due to IKATP activation (12), and a sheep-heart model of pacing-induced, cholinergically mediated AF (13). In addition, we integrated information at the structural, cellular, and whole-organ levels to shed light on the changes in tachyarrhythmia dynamics caused by the possible interactions between chloroquine and specific amino acids, forming unique receptors in IK1, IKACh, and IKATP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mapping

Adult mice, rabbits, and sheep were heparinized and anesthetized. The heart was rapidly excised and cannulated, then placed in the well of a custom-made chamber maintained at 37°C. Optical mapping was carried out as described earlier (11, 13, 21), using Di-4-ANEPPS (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and a high-resolution CCD camera (600–1000 frames/s). Experiments in the rabbit hearts were performed in the presence of 40 μM pinacidil (Sigma), an IKATP opener (12), and standard cholinergic AF experiments in sheep hearts were performed as described earlier (13), in the presence of 500 nM acetylcholine (Sigma).

Electrograms

Volume-conducted ECGs approximating lead II were recorded in isolated mouse and rabbit hearts using a Biopac Systems amplifier (DA100C; Biopac Systems, Inc., Goleta, CA, USA). For multichannel recordings of extracellular potentials in sheep hearts, we used the NavX System (St. Jude Medical, Little Canada, MN, USA) and a Reflexion spiral catheter (St. Jude Medical) stitched to the epicardial surface of the left atrial free wall. Twenty unipolar signals were acquired (sampling rate, 1.2 kHz) continuously for the duration of the experiment.

Pacing

To induce VT/VF in mouse and rabbit hearts, we used short bursts of square pulses, 3 ms in duration, at cycle lengths between 10 and 30 ms. For AF induction in sheep hearts, we used tachypacing through a bipolar electrode on the epicardium of the right atrium (5-ms pulses, ×2 diastolic threshold).

Arrhythmia analysis

We constructed phase movies of reentry and traced the trajectory of the phase singularities, where all the phases converge, as described previously (22). We used fast Fourier transform (FFT) analysis on each pixel of the epicardial optical signals to generate dominant frequency (DF) maps (22). For electrograms recorded during AF, DFs in the range of 4–30 Hz of 5-s unipolar voltage time-series segments were determined with the NavX built-in module.

Patch clamping

Isolated myocytes were prepared from young guinea pigs. IK1 and IKATP (100 μM pinacidil) were recorded from ventricular cells. IKACh (1 μM carbachol; Sigma) was recorded from atrial myocytes as described previously (18). Currents were recorded in the whole-cell configuration. Ba2+-sensitive (2 mM) I/V relationships were constructed by plotting the currents at the end of 1-s voltage step commands (from −120 mV to −20 mV, holding potential of −40 mV). For the determination of the IC50 for IK1, IKATP, and IKACh block by chloroquine, the fractional block of current was plotted as a function of drug concentration ([D]), and the data were fit with the Hill equation.

Molecular modeling

Modeling studies were based on coordinates for chloroquine extracted from DrugBank (23), and the cytoplasmic domains of Kir2.1 (24) (PDB ID: 1U4F), Kir3.1 (24) (PDB ID: 1U4E) and Kir6.2 modeled onto the Kir2.1 structure. For the Kir6.2 model, the sequence of Kir6.2 was overlaid onto structure of Kir2.1 in Coot (25). The resulting structure was refined via simulated annealing in the crystallography and NMR system program (26) with a solvent dielectric constant of 80. Docking simulations of all structures were performed in Autodock 4.0.1 (27), employing the genetic algorithm for 10 runs with a population size of 150. Prior to these calculations, the ionization of the ligands was adjusted for physiological pH. During the calculations, the protein was held rigid, and the ligands were allowed to flex. The resulting complexes were ranked according to binding energy. The complex with the lowest binding energy was further refined by slow-cooled simulated annealing followed by minimization in crystallography and NMR system program (26). During the simulated annealing runs, both protein and ligand were flexible. The complex was heated to 1000 K, then cooled to 300 K in 25-K increments with a surrounding dielectric constant of 80. Solvent-accessible surface areas for the complexes were calculated in CCP4 Access (28). Solvent-accessible surface maps of the complexes were calculated and displayed in PyMOL with the APBS plug-in (PyMOL Molecular Graphics System 2008; DeLano Scientific, Palo Alto, CA, USA). The probe radius for the maps was 1.4 Å.

Statistics

Results are reported as means ± sd. ANOVA and t test were used as appropriate. Significance was taken at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

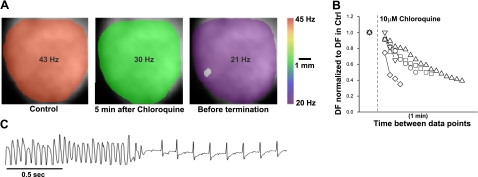

Chloroquine terminates stable high-frequency VT/VF in the mouse heart

IK1 up-regulation leads to stable and fast reentrant ventricular arrhythmias in a mouse model of cardiac specific Kir2.1 overexpression (11). Here, we examined the effects of chloroquine on VT/VF in this mouse model. Figure 1A presents DF maps during VT in a representative heart in which stable, high-frequency VT/VF was induced by a rapid pacing protocol. DF maps were obtained in control conditions (Fig. 1A, left panel; DF=43 Hz), at 5 min after administration of 10 μM chloroquine (DF=30 Hz), and just before termination of arrhythmia (DF=21 Hz). Figure 1B plots data from 5 experiments. DF was normalized to that measured at VT/VF onset and displayed every minute after the addition of chloroquine. VT/VF converted to sinus rhythm in 5 of 5 hearts after slowing by a factor of 0.5 ± 0.12 over a mean period of 8 ± 5 min of continuous intracoronary drug perfusion. The representative ECG trace in Fig. 1C shows the sudden VT/VF termination with conversion to sinus rhythm.

Figure 1.

Chloroquine terminates stable high-frequency VT/VF in the mouse heart. A) Dominant frequency maps at the onset of pacing-induced VT (DFmax=43 Hz), 5 min after 10 μM chloroquine (30 Hz), and before arrhythmia termination (21 Hz). B) Plot of normalized VT/VF DFmax in 5 mouse hearts. After the addition of 10 μM chloroquine, the normalized DFmax is displayed at 1-min intervals. VT/VF terminated in 5 of 5 mouse hearts. C) Volume conducted ECG: termination of polymorphic VT and resumption of normal sinus rhythm.

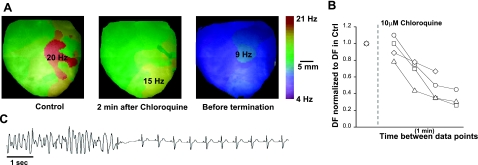

Antifibrillatory effects of chloroquine in the rabbit heart

We also examined the effects of chloroquine on VF in the rabbit heart in the presence of 40 μM pinacidil (IKATP opener). Figure 2A shows DF maps of a rabbit heart in VF. The domain with fastest frequency (DFmax) was 20 Hz before 10 μM chloroquine was added. At 2 min of continuous chloroquine perfusion, the maximal frequency was reduced to 15 Hz. At 4 min, just before termination of arrhythmia, the frequency of arrhythmia was 9 Hz. In 5 rabbit hearts, chloroquine reduced VF frequency by a factor of 0.41 ± 16. In 4 of those hearts, the drug converted VF to sinus rhythm at 4 ± 0.5 min of perfusion. Figure 2B plots the time course of normalized DFmax following drug perfusion onset in the 4 hearts that converted to sinus rhythm. Before termination, the frequency of tachyarrhythmias decelerated by a factor of 0.42 ± 0.18 compared to that at onset. Figure 2C is a representative ECG showing VF termination and resumption of normal sinus rhythm.

Figure 2.

Antifibrillatory effects of chloroquine in the rabbit heart. A) Dominant frequency maps at the onset of pacing-induced VF (DFmax=20 Hz, red), 2 min after 10 μM chloroquine (15 Hz), and before arrhythmia termination (9 Hz). B) Plot of normalized VF DFmax in 4 mouse hearts. After the addition of 10 μM chloroquine, the normalized DFmax is displayed at 1-min time intervals. VT/VF terminated in 4 (plotted) of 5 rabbit hearts. C) Volume conducted ECG: termination of polymorphic VT and resumption of normal sinus rhythm.

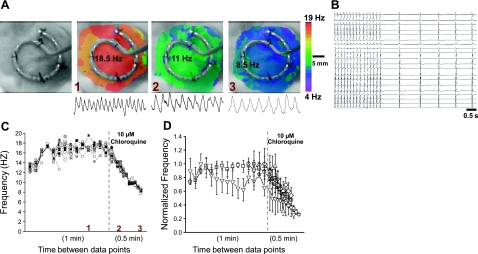

Chloroquine terminates cholinergic AF in the sheep heart

We investigated the effect of chloroquine in an isolated sheep-heart model of cholinergic AF induced by rapid atrial pacing, in the continuous presence of 0.5 μM acetylcholine (13). Figure 3A shows DF maps from a representative experiment. Optical and multiple-electrode mapping data were obtained simultaneously. The leftmost frame is a black-and-white snapshot of the left atrial appendage with a 20-pole catheter secured onto the epicardium by 5 suture points. The second frame on the left is an optical DF map constructed during AF, before the addition of chloroquine, at which time the DFmax was 18.5 Hz. The third frame is the DF map obtained ∼4 min after chloroquine was added to the perfusate, with a slower DFmax (11 Hz). The rightmost frame was obtained just before AF termination; the DFmax decreased to 8.5 Hz. Figure 3B shows tracings of the 20 electrogram recordings immediately before termination and on conversion to sinus rhythm. In Fig. 3C, we have plotted the normalized frequency of the 20 simultaneous unipolar atrial electrograms. Frequency was measured every minute during control (only the last minute is shown), and every 0.5 min during chloroquine perfusion. The numbers in red indicate the time in the experiment at which the optical DF maps in Fig. 3A were recorded. In Fig. 3C, AF frequency was relatively stable at all electrode locations, but decreased steeply on chloroquine perfusion, until termination occurred. In Fig. 3D, we display the time course of the normalized frequency measured in 5 sheep hearts. Each symbol represents mean ± sd data in one experiment. Chloroquine decreased the AF frequency by a factor of 0.44 ± 0.15, leading to resumption of sinus rhythm in the 5 hearts.

Figure 3.

Chloroquine terminates cholinergic AF in the sheep heart. A) First panel: image of the left atrial appendage with the 20-unipole catheter stitched on the epicardial surface. Second panel: DF map during AF, before chloroquine (DFmax=18.5 Hz). Third panel: DF map at 4 min after chloroquine (DFmax=11 Hz). Fourth panel: just before termination (DFmax=8.5 Hz). Numbers in red relate to panel C (see below). One-second, single-pixel recordings are shown under each DF map. B) Plots of the 20 electrograms in a representative example just before chloroquine terminated AF and restored sinus rhythm. C) Plot of frequency calculated from each of the 20 unipolar atrial electrograms in one experiment. Frequency was measured every minute before chloroquine, and every 0.5 min after chloroquine. Numbers in red indicate the time in the experiment at which the DF maps in panel A were taken. D) Time course of normalized frequency before and during chloroquine treatment for the 20 electrograms in the 5 sheep. Each symbol represents an experiment.

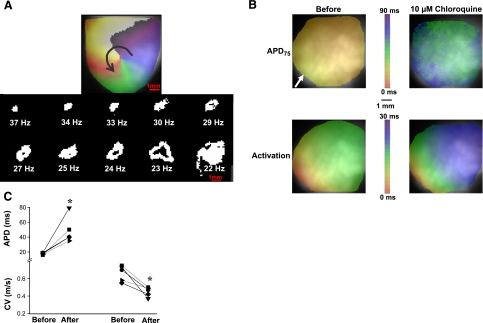

Chloroquine destabilizes rotors and terminates fibrillation by prolonging the wavelength (WL)

To investigate the possible mechanisms of chloroquine's antifibrillatory effects, we returned to the transgenic mouse heart in which we had previously demonstrated that up-regulation of IK1 results in exceedingly stable high-frequency rotors and VF (11). Figure 4A shows the evolution of the rotor dynamics in a representative heart. The upper panel is the phase map snapshot of a stable rotor that maintained VT/VF and lasted for the duration of the experiment, until it was terminated by cloroquine. At the center of the map, the site at which all of the colors converge is the phase singularity (PS), which corresponds to the tip of the wavefront (22). The arrow indicates the direction of rotation. The bottom panel is an illustration of PS trajectories for ∼15 rotations in each case, and respective DFs at 10 different times during chloroquine perfusion. In control, the rotor was relatively stable at 37 Hz. With time, the excursion of the PS trajectory became wider and more intricate, and correspondingly the DF slowed. As chloroquine perfusion continued, the PS excursions increased to such an extent that the DF decreased all the way down to 22 Hz. Immediately thereafter, the wavefront diverged from the center so much that it likely collided with its wavetail or with a tissue boundary and could no longer undergo a full rotation. VT/VF termination was immediately followed by resumption of sinus rhythm. A similar behavior was observed in 2 mouse hearts.

Figure 4.

Chloroquine destabilizes rotors and terminates VF by prolonging the wavelength. A) Top panel: phase snapshot of a rotor in a mouse heart during VT. Arrow denotes direction of rotation. At the center of the rotor is the PS. Bottom panel: plots of PS trajectory and corresponding DFs at 10 different time intervals before and after the addition of 10 μM chloroquine. In control conditions, DF was 37 Hz and rotor was stationary. In the presence of chloroquine, rotor became increasingly unstable with amplified meandering of its PS as it slowed down. DF was 22 Hz just before VT termination as a result of hypermeandering of the PS trajectory. B) Top panels: APD75 maps. Bottom panels: activation maps. Arrow denotes stimulation site. C) APD and CV plots in 5 hearts before and after 10 μM chloroquine. APD increased from 18 ± 1.4 to 52.3 ± 18.4 ms; CV decreased from 0.68 ± 0.09 to 0.44 ± 0.06 m/s. *P < 0.05.

Possible wavefront-wavetail collisions leading to arrhythmia deceleration and termination suggested that chloroquine might have affected the WL, which is the product of the action potential duration (APD) and conduction velocity(CV): WL ∼ APD × CV. We determined the effects of 10 μM chloroquine in mice on APD and CV during pacing from the apex (white arrow), at cycle length = 140 ms. In 5 experiments, APD75 increased from 18 ± 1.4 to 52.3 ± 18.4 ms (P<0.05), and CV decreased from 0.68 ± 0.09 to 0.44 ± 0.06 m/s (P<0.05; n=5) (Fig. 4B, C). This decrease could be due to direct blockade of sodium channels, and their inactivation due to the slight membrane depolarization caused by IK1 blockade. Consequently, the mean WL increased from 11.8 ± 1.9 mm to 21.4 ± 5.5 mm; P < 0.05, supporting the idea that wavefront-wavetail collisions contributed to arrhythmia deceleration.

Blocking efficacy of chloroquine in Kir2.1, Kir3.1, and Kir6.2

We conducted patch-clamp experiments to examine effects of chloroquine on IK1, IKATP, and IKACh in ventricular and atrial myocytes. Figure 5A–C shows data for IK1 in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Figure 5A shows representative current traces, in control conditions and following the addition of 3 μM chloroquine. Figure 5B shows an I/V relationship for 5 cells, illustrating most importantly the chloroquine-induced reduction in the outward component of the current. Figure 5C shows that the IC50 of IK1 block by chloroquine at −60 mV is 0.69 ± 0.09 μM. Figure 5D–F presents data for guinea pig atrial myocytes. In Fig. 5D, the current traces at left were obtained under control conditions; traces in the middle are IKACh currents activated by 1 μM carbachol, and traces at right are currents after the addition of chloroquine in the continuous presence of carbachol. Figure 5E shows the I/V relationship obtained from 5 cells. In Fig. 5F, the IC50 for IKACh block was 0.38 ± 0.04 μM. Finally, Fig. 5G–I illustrates the data for IKATP in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Pancreatic IKATP has been shown to be blocked by chloroquine (19). Here, we show that the cardiac IKATP is blocked by the drug as well. In Fig. 5G, the current traces at left reflect control conditions; middle traces were obtained after addition of 100 μM pinacidil to activate IKATP, and the traces at right were obtained after the addition of 3 μM chloroquine, in the presence of pinacidil. Figure 5H shows the I/V relationship obtained from 5 cells. In Fig. 5I, the IC50 for IKATP block was 0.51 ± 0.08 μM.

Figure 5.

Blocking efficacy of chloroquine in different inward rectifier channels .Voltage protocol: steps from −120 mV to −20 mV. A) IK1 current traces in ventricular myocytes. B) I/V relationship from 5 cells. C) Dose-response curve of blocked IK1 at −60 mV. D) Current traces in atrial myocytes in the presence of 1 μM carbachol to activate IKACh. E) I/V relationship from 5 cells. F) Dose-response curve of blocked IKACh at −60 mV. G) Current traces in ventricular myocytes in the presence of 100 μM pinacidil to activate IKATP. E) I/V relationship from 5 cells. F) Dose-response curve of blocked IKATP at −60 mV.

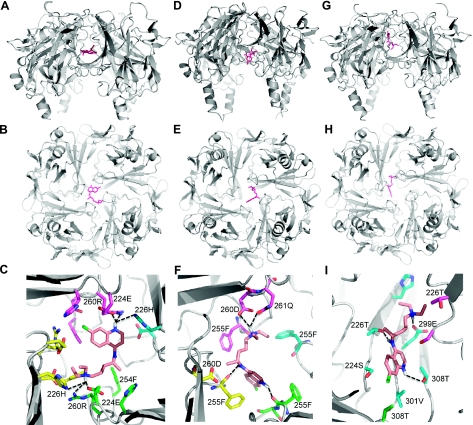

Chloroquine interacts with residues of the cytoplasmic domains of cardiac Inward rectifier channels

Data suggest that chloroquine's effect on APD is mediated, in part, by its preferential ability to block IK1 (29). Recently, it was shown that chloroquine reduces IK1 in the outward more than the inward direction, via its interaction with amino acids E224, F254, D255, D259, and E299 at the cytoplasmic tail of Kir2.1 (17). As an extension of that study, we conducted molecular modeling studies on the docking of chloroquine within the cytoplasmic domains of Kir2.1, Kir3.1, and Kir6.2. The results revealed that chloroquine binds more effectively to the cytoplasmic domains of Kir2.1 and Kir3.1 than to that of Kir6.2. In Fig. 6A–C, chloroquine, depicted in pink, appears at the center of the modeled Kir2.1 channel. The drug is suspended in an intense band of negative charge created by the presence of the negatively charged amino acids E224, D259, and E299. Of these residues, only E224 is in a position to form charge-charge interactions with the molecule. D259 is very close to choloroquine, (within 4 Å), and is involved in van der Waals interactions. E299 is located >5 Å from the chloroquine molecule (Fig. 6C). In addition to E224 and the negative charge potential stabilizing the binding of chloroquine, H226 and R260 form hydrogen bonds with the charged nitrogens of chloroquine, and F254 from 3 subunits provides a hydrophobic base for the molecule (Fig. 6C). This mode of binding blocks the channel, inhibiting the passage of ions. In Kir3.1 (Fig. 6D–F), the negative electrostatic potential in the channel is lower than in Kir2.1 because there are only two acidic residues contributing to the negative charged ring, D260 and E300. Because of the shift in negative charge, chloroquine binds closer to the cytoplasmic orifice of the channel (Fig. 6D), interacting with F255, D260, and Q261 and only partially blocking the channel. As illustrated in Fig. 6G–I, Kir6.2 lacks the ring of negative charge due to the absence of a corresponding E224 or D259. The respective equivalent residues for E224 and D259 in Kir6.2 are S225 and N247, which are neutral polar residues. Only an equivalent for E299 exists, E288, which forms a hydrogen bond with quaternary amine. The other hydrogen bonding interactions are with T287 and T214, equivalent to H226 in Kir2.1 (Fig. 6G–I). This causes chloroquine to bind the side of the channel.

Figure 6.

Chloroquine interacts with residues of the cytoplasmic domains of cardiac inward rectifier channels. Ribbon structure of each protein is shown in gray, with chloroquine as pink sticks. Images show models of the lowest energy binding of chloroquine to Kir2.1 (A–C), Kir3.1 (D–F), and Kir6.2 (G–I). A, D, G) Longitudinal view. B, E, F) Bird's eye view from the cytoplasm. C, F, I) Zoomed-in view on the bound chloroquine, showing amino acids residues within 4 Å of chloroquine depicted as sticks. Dashed lines represent hydrogen bonds.

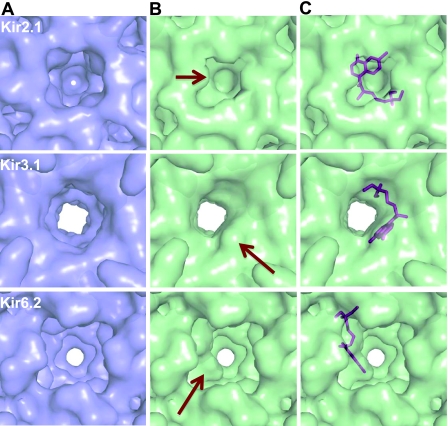

Chloroquine blocks the ion permeation pathways of Kir2.1 and Kir3.1 more effectively than that of Kir6.2

Molecular modeling studies (Fig. 6) revealed that chloroquine has different modes of binding to the Kir2.1, Kir3.1, and Kir6.2 intracellular domains, depending on the presence or absence of electronegative residues facing the vestibule of the channel. To unveil the consequential effects of the different interactions of chloroquine and the respective intracellular domains of the three different Kir channels, solvent-accessible areas and maps were calculated (Fig. 7). The surface maps defining the channels show that Kir2.1, Kir3.1, and Kir6.2 each have a cavity >26 Å in length that runs through the center of the tetramer and a cytoplasmic pore opening ≥10 Å in diameter (Fig. 7A). On chloroquine binding to Kir2.1, the vestibule becomes blocked, with its depth decreasing from 28 to 10 Å, and the opening narrows in diameter by ∼2.5 Å to an opening of 7.2 × 7.7 Å (Fig. 7B, C). When chloroquine binds to Kir3.1, there is no change in the depth of the vestibule, but the opening becomes oblong (∼8×10.3 Å) (Fig. 7B, C). In Kir6.2 bound to chloroquine, there is no change in either the opening or the length of the vestibule. In Kir6.2, chloroquine binds to the side of a large cavity near the membrane side of the protein, creating a pathway >10 Å in diameter, which most likely will not impede the passage of potassium ions (Fig. 7B, C). Therefore, it is doubtful that chloroquine inhibition of Kir6.2 is taking place in the cytoplasmic domain; it could be in the transmembrane region. In contrast, the site of chloroquine inhibition of Kir2.1 and Kir3.1 may indeed be located in the cytoplasmic domain. Although the opening in these proteins when bound to chloroquine is still large enough to accommodate a single potassium ion with a diameter of 2.66 Å or a potassium ion with half of its first hydration shell intact (30), the fact that chloroquine can partially block the permeation pathway in Kir3.1 and completely occlude it in Kir2.1 provides evidence that these models show the possible sites of inhibition.

Figure 7.

Chloroquine blockade of the ion permeation pathway is more effective for Kir2.1 and Kir3.1 than for Kir6.2. Images show solvent-accessible surface maps of the intracellular pores of Kir2.1, Kir3.1, and Kir6.2 in the presence (green) and absence (blue) of chloroquine. Views are oriented as in Fig. 6B, E H. A) Surface-accessible maps of Kir 2.1, Kir3.1, and Kir6.2 in the absence of chloroquine. Pore openings are 10.1 × 10.1 Å for Kir 2.1, ∼11 × 11Å for Kir3.1, and 10.4 × 10.3 Å for Kir6.2. B) Maps calculated in the presence of bound chloroquine. Arrows indicate significant changes in the surface due to chloroquine. Pore openings are 7.2 × 7.7 Å for Kir2.1, ∼8 × 10.3 Å for Kir3.1, and 10.4 × 10.3 Å for Kir6.2. C) Placement of chloroquine (magenta sticks) within the calculated solvent accessibility surface maps. Depth of the permeation pathway on chloroquine binding is unchanged for Kir3.1 (∼26 Å) and Kir6.2 (∼27 Å), but is shortened from ∼28 to ∼10.5 Å for Kir2.1.

DISCUSSION

Summary

We used integrative and multidisciplinary approaches to establish how a drug's interaction with specific amino acids in an ion channel modify the behavior of arrhythmias. We show for the first time that the specific interaction of chloroquine with each of 3 types of Kir channel at the structural level is linked to the effects of the drug in the whole heart. We demonstrate that the chloroquine-induced alterations of the geometries of the IK1, IKACh, and IKATP ion permeation pathways can translate into an increase in inward rectification, and necessarily affect the dynamics of tachyarrhythmias. Inward rectifier blockade by chloroquine is antifibrillatory in both the atria and the ventricles, where blockade of Kir2.1, Kir3.1, and Kir6.2 is achieved by chloroquine's ability to interact to variable degrees with negatively charged residues within the ion permeation pathway of the intracellular domain of the respective channel.

Inward rectifier potassium channels are important in the control of the rate and frequency of functional reentry (11–13, 22). Our data suggest that agents capable of sufficiently reducing inward rectifier potassium currents (IK1, IKATP, IKACh) in scenarios where they exert arrhythmic effects will slow the tachyarrhythmias and may effectively cause their termination. The above inference is based on studies and technologies that span three different levels of integration, including molecular modeling of the channel's structure/function relationships, voltage-clamp analysis of the ion channel currents and optical mapping of wave propagation.

Structural considerations

Our patch-clamp and modeling data strongly suggest that chloroquine exerts its antiarrythmic actions in part by interacting with residues of the cytoplasmic domains of cardiac inward rectifier channels. The lowest-energy model is depicted in Figs. 6 and 7. For Kir6.2, the absence of strong negative charges in the Kir6.2 channel resulted in wide variations in the binding models for chloroquine, unlike Kir2.1 and Kir3.1, where there was a consensus between the top 4 to 6 models, and showed similar binding rotated by 90° due to the 4-fold symmetry within the channel. The common theme the Kir6.2 models tested was that they showed chloroquine binding close to the membrane side of the Ki6.2 channel interacting with S212 and E288 in multiple ways. This may suggest that chloroquine's binding to Kir6.2 requires the presence of negatively charged amino acids, but those amino acids might not only be in the actual cytoplasmic domain; additional binding sites deep within the internal cavity of the transmembrane region may be present. As such, in contrast to Kir2.1 and Kir3.1, we remain somewhat uncertain as to how chloroquine actually binds within the Kir6.2 channel.

It is known that Kir3.1 does not form homomeric channels on the cell surface (31). Therefore, the channel responsible for IKACh is heteromeric and formed by Kir3.1/Kir3.4. However, a crystal structure of Kir3.1/Kir3.4 is not available. Compared to Kir3.1, which has a ring formed by 2 electronegative residues (D260 and E300) where chloroquine binds, Kir3.4 has an electronegative ring formed by E231, D266, and E306, which are the equivalent of E224, D259, and E299 in Kir2.1. Consequently, the mode of interaction of chloroquine with the heteromeric Kir3.1/Kir3.4 channel may be similar to the interaction of the drug with Kir2.1. Further, the numerical predictions did not take into account factors that could change the 3-dimensional conformation and properties of the channels and/or alter the drug-channel interactions, due to the lack of such structural information. In this regard, it is known that phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) has important effects on Kir channels (32, 33) and could play a role in modulating drug-channel interactions.

Specificity considerations

Chloroquine prolongs the APD (6) by preferentially blocking inward rectifier channels, but it also can block IKr, INa, and ICaL in the following order of selectivity: IK1 > IKr > INa > ICaL (6). Nevertheless, at the dose used in this study, chloroquine can reduce IKr, INa, and ICaL, which may contribute somewhat to the antifibrillatory effects of chloroquine we have observed. In two additional experiments we performed in the sheep heart, 1 μM chloroquine terminated cholinergic AF. It should be noted at this point that other antimalarials, such as halofantrine, block IKr (34). We would expect this drug to prolong APD and therefore slow the frequency of tachyarrhythmias. However, because of the important role played by inward rectifier channels in controlling frequency and stability of reentry (11), we speculate that chloroquine will be more a more effective antifibrillatory agent due to its ability to block such channels. Nobably, halofantrine treatment results in a major and well-documented prolongation of the QT interval (35). In contrast, chloroquine's QT-prolonging effect is comparatively smaller with respect to halofantrine (35, 36). Finally, we cannot determine the specific contribution of the expected chloroquine inhibition of each of the inward rectifier current types (IK1, IKATP, and IKACh) to arrhythmia termination in the models. For instance, it is possible that IK1 blockade alone could terminate arrhythmias in the IKATP and IKACh-mediated arrhythmias. Addressing this issue in detail will require further investigation.

Clinical perspective

It has been suggested that by blocking Kir2.1 channels, chloroquine produces lethal arrhythmias (17). For the first time, our data demonstrate otherwise. One of the well-known variants of the long QT syndrome, the so-called LQT7 or Andersen-Tawil syndrome, is associated with mutations in KCNJ2, which cause dominant-negative suppression of Kir2.1 channel function and ventricular arrhythmias, including torsades de pointes (37–40). However, unlike other forms of inherited LQTS, sudden death is rarely reported in Andersen syndrome (41).

If increasing inward rectifier currents stabilizes reentrant arrhythmias (11, 12, 42), then their blockade should lead to destabilization. Our study provides definite proof for that hypothesis using a clinically prescribed agent. In addition, most importantly, our results provide structural biological insight at the ion channel level into why destabilization is occurring. We show that the chloroquine-induced alterations of the geometries of the IK1, IKACh, and IKATP ion permeation pathways translate into an increase in inward rectification, and necessarily affect the tachyarrhythmia dynamics.

Future directions

We submit that taking advantage of comparable knowledge may be useful in the development of novel and potentially useful antifibrillatory pharmacophores. The chloroquine-binding models for Kir channels provide a starting point for feasible approaches in the generation of new therapies. Our data suggest that the binding of chloroquine to specific sites in Kir channels affects arrhythmia dynamics. Therefore, crystallizing and solving the high-resolution structures of the Kir2.1, Kir3.1, and Kir6.2 complexed with chloroquine to confirm the binding modes of the drug to the channels will be the next step in this process. The uniqueness of the binding sites that chloroquine occupies in the different Kir channels may offer the chance to develop new, more potent, and specific compounds using structure based drug design.

Limitations

Numerical simulations do not recapitulate all aspects of drug-channel interactions or the possible effects of modulatory agents, such as PIP2, on Kir channels. Crystallization and determination of the three-dimensional structure of chloroquine in complex with the Kir channels is essential in understanding all aspects of drug-channel interactions. Since coronary artery disease is the underlying substrate for >80% of patients who experience sudden cardiac death, experiments with chloroquine in large animal models of tachyarrhythmias related to ischemia and/or infarction, will be necessary to test the hypothesis that in such settings, chloroquine is antiarrhythmic. On the other hand, although our experiments show that chloroquine is very effective in terminating acute cholinergic AF, before any of these data can be translated into the clinic, it would be crucial to test the ability of chloroquine to restore sinus rhythm in animal models of chronic/persistent AF.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants P01-HL039707, P01-HL087226, R01-HL080159, and R01 HL60843; the Leducq Foundation, (J.J.), an American Heart Association (AHA) Scientist Development Grant (S.P.); an AHA Postdoctoral Fellowship (S.F.N.); the University of Michigan Center for Structural Biology; and Secretaria de Educacion Publica-Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnologia, Mexico, grant CB-2008-01-105941 (J.A.S.C.).

The authors thank Elliot Wang and Drs. Steven R. Ennis and Jérôme Kalifa for technical assistance and useful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hibino H., Inanobe A., Furutani K., Murakami S., Findlay I., Kurachi Y. (2010) Inwardly rectifying potassium channels: their structure, function, and physiological roles. Physiol. Rev. 90, 291– 366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Priori S. G., Pandit S. V., Rivolta I., Berenfeld O., Ronchetti E., Dhamoon A., Napolitano C., Anumonwo J., Raffaele di Barletta M., Gudapakkam S., Bosi G., Stramba-Badiale M., Jalife J. (2005) A novel form of short QT syndrome (SQT3) is caused by a mutation in the KCNJ2 gene. Circ. Res. 96, 800– 807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xia M., Jin Q., Bendahhou S., He Y., Larroque M. M., Chen Y., Zhou Q., Yang Y., Liu Y., Liu B., Zhu Q., Zhou Y., Lin J., Liang B., Li L., Dong X., Pan Z., Wang R., Wan H., Qiu W., Xu W., Eurlings P., Barhanin J. (2005) A Kir2.1 gain-of-function mutation underlies familial atrial fibrillation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 332, 1012– 1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dobrev D., Wettwer E., Kortner A., Knaut M., Schuler S., Ravens U. (2002) Human inward rectifier potassium channels in chronic and postoperative atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc. Res. 54, 397– 404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saksena S., Domanski M. J., Benjamin E. J., Camm A. J., Ezekowitz M. D., Gersh B. J., Jalife J., Naccarelli G. V., Vlietstra R. E., Wyse D. G. (2001) Report of the NASPE/NHLBI round table on future research directions in atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 24, 1435– 1451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujita A., Kurachi Y. (2000) Molecular aspects of ATP-sensitive K+ channels in the cardiovascular system and K+ channel openers. Pharmacol. Ther. 85, 39– 53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haissaguerre M., Chatel S., Sacher F., Weerasooriya R., Probst V., Loussouarn G., Horlitz M., Liersch R., Schulze-Bahr E., Wilde A., Kaab S., Koster J., Rudy Y., Le Marec H., Schott J. J. (2009) Ventricular fibrillation with prominent early repolarization associated with a rare variant of KCNJ8/KATP channel. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 20, 93– 98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehrlich J. R. (2008) Inward rectifier potassium currents as a target for atrial fibrillation therapy. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 52, 129– 135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Varro A., Biliczki P., Iost N., Virag L., Hala O., Kovacs P., Matyus P., Papp J. G. (2004) Theoretical possibilities for the development of novel antiarrhythmic drugs. Curr. Med. Chem. 11, 1– 11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dhamoon A. S., Jalife J. (2005) The inward rectifier current (IK1) controls cardiac excitability and is involved in arrhythmogenesis. Heart Rhythm 2, 316– 324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noujaim S. F., Pandit S. V., Berenfeld O., Vikstrom K., Cerrone M., Mironov S., Zugermayr M., Lopatin A. N., Jalife J. (2007) Up-regulation of the inward rectifier K+ current (IK1) in the mouse heart accelerates and stabilizes rotors. J. Physiol. 578, 315– 326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uchida T., Yashima M., Gotoh M., Qu Z. L., Garfinkel A., Weiss J. N., Fishbein M. C., Mandel W. J., Chen P. S., Karagueuzian H. S. (1999) Mechanism of acceleration of functional reentry in the ventricle effects of ATP-sensitive potassium channel opener. Circulation 99, 704– 712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarmast F., Kolli A., Zaitsev A., Parisian K., Dhamoon A. S., Guha P. K., Warren M., Anumonwo J. M., Taffet S. M., Berenfeld O., Jalife J. (2003) Cholinergic atrial fibrillation: I(K,ACh) gradients determine unequal left/right atrial frequencies and rotor dynamics. Cardiovasc. Res. 59, 863– 873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pandit S. V., Berenfeld O., Anumonwo J. M., Zaritski R. M., Kneller J., Nattel S., Jalife J. (2005) Ionic determinants of functional reentry in a 2-D model of human atrial cells during simulated chronic atrial fibrillation. Biophys. J. 88, 3806– 3821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Avina-Zubieta J. A., Galindo-Rodriguez G., Newman S., Suarez-Almazor M. E., Russell A. S. (1998) Long term effectiveness of antimalarial drugs in rheumatic diseases. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 57, 582– 587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burrell Z. L., Jr, Martinez A. C. (1958) Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of cardiac arrhythmias. N. Engl. J. Med. 258, 798– 800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez-Menchaca A. A., Navarro-Polanco R. A., Ferrer-Villada T., Rupp J., Sachse F. B., Tristani-Firouzi M., Sanchez-Chapula J. A. (2008) The molecular basis of chloroquine block of the inward rectifier Kir2.1 channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 1364– 1368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benavides-Haro D. E., Sanchez-Chapula J. A. (2000) Chloroquine blocks the background potassium current in guinea pig atrial myocytes. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 361, 311– 318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gribble F. M., Davis T. M., Higham C. E., Clark A., Ashcroft F. M. (2000) The antimalarial agent mefloquine inhibits ATP-sensitive K-channels. Br. J. Pharmacol. 131, 756– 760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mzayek F., Deng H. Y., Mather F. J., Wasilevich E. C., Liu H. Y., Hadi C. M., Chansolme D. H., Murphy H. A., Melek B. H., Tenaglia A. N., Mushatt D. M., Dreisbach A. W., Lertora J. J. L., Krogstad D. J. (2007) Randomized dose-ranging controlled trial of AQ-13, a candidate antimalarial, and chloroquine in healthy volunteers. PLoS Clin. Trials 2, e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gray R. A., Jalife J., Panfilov A., Baxter W. T., Cabo C., Davidenko J. M., Pertsov A. M. (1995) Nonstationary vortexlike reentrant activity as a mechanism of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in the isolated rabbit heart. Circulation 91, 2454– 2469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samie F. H., Berenfeld O., Anumonwo J., Mironov S. F., Udassi S., Beaumont J., Taffet S., Pertsov A. M., Jalife J. (2001) Rectification of the background potassium current: a determinant of rotor dynamics in ventricular fibrillation. Circ. Res. 89, 1216– 1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wishart D. S., Knox C., Guo A. C., Cheng D., Shrivastava S., Tzur D., Gautam B., Hassanali M. (2008) DrugBank: a knowledgebase for drugs, drug actions and drug targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, D901– D906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pegan S., Arrabit C., Zhou W., Kwiatkowski W., Collins A., Slesinger P. A., Choe S. (2005) Cytoplasmic domain structures of Kir2.1 and Kir3.1 show sites for modulating gating and rectification. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 279– 287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126– 2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brunger A. T., Admas P. D., Clore G. M., Delano W. L., Gros P., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Jiang J.-S., Kuszewsji J., Nigles N., Pannu N. S., Read R. J., Rice L. M., Simonson T., Warren G. L. (1998) Crystallography and NMR system (CNS): a new software system for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54, 905– 921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morris G. M., Goodsell D. S., Halliday R. S., Huey R., Hart W. E., Belew R. K., Olson A. J. (1998) Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical binding free energy function. J. Comp. Chem. 19, 1639– 1662 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Collaborative Computational Project Number 4 (1994) The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50, 760– 763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanchez-Chapula J. A., Salinas-Stefanon E., Torres-Jacome J., Benavides-Haro D. E., Navarro-Polanco R. A. (2001) Blockade of currents by the antimalarial drug chloroquine in feline ventricular myocytes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 297, 437– 445 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beckstein O., Sansom M. (2004) The influence of geometry, surface character, and flexibility on the permeation of ions and water through biological pores. Phys. Biol. 1, 42– 52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma D., Zerangue N., Raab-Graham K., Fried S. R., Jan Y. N., Jan L. Y. (2002) Diverse trafficking patterns due to multiple traffic motifs in G protein-activated inwardly rectifying potassium channels from brain and heart. Neuron 33, 715– 729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Logothetis D. E., Jin T., Lupyan D., Rosenhouse-Dantsker A. (2007) Phosphoinositide-mediated gating of inwardly rectifying K+ channels. Pflügers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 455, 83– 95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ponce-Balbuena D., Lopez-Izquierdo A., Ferrer T., Rodriguez-Menchaca A. A., Arechiga-Figueroa I. A., Sanchez-Chapula J. A. (2009) Tamoxifen inhibits Kir2. x family of inward rectifier channels by interfering with PIP2-channel interactions. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 331, 563– 573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tie H., Walker B. D., Singleton C. B., Valenzuela S. M., Bursill J. A., Wyse K. R., Breit S. N., Campbell T. J. (2000) Inhibition of HERG potassium channels by the antimalarial agent halofantrine. Brit. J. Pharmacol. 130, 1967– 1975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kujanik Š. (2007) Ventricular arrhythmias and genetics. Acta Med. Martiniana 7, 3– 9 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sowunmi A., Fehintola F. A., Ogundahunsi O. A. T., Ofi A. B., Happi T. C., Oduola A. M. J. (1999) Comparative cardiac effects of halofantrine and chloroquine plus chlorpheniramine in children with acute uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hygiene 93, 78– 83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu C. W., Lin J. H., Rajawat Y. S., Jerng H., Rami T. G., Sanchez X., DeFreitas G., Carabello B., DeMayo F., Kearney D. L., Miller G., Li H., Pfaffinger P. J., Bowles N. E., Khoury D. S., Towbin J. A. (2006) Functional and clinical characterization of a mutation in KCNJ2 associated with Andersen-Tawil syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 43, 653– 659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Priori S. G., Napolitano C. (2004) Genetics of cardiac arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1015, 96– 110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tristani-Firouzi M., Jensen J. L., Donaldson M. R., Sansone V., Meola G., Hahn A., Bendahhou S., Kwiecinski H., Fidzianska A., Plaster N., Fu Y. H., Ptacek L. J., Tawil R. (2002) Functional and clinical characterization of KCNJ2 mutations associated with LQT7 (Andersen syndrome). J. Clin. Invest. 110, 381– 388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang L., Benson D. W., Tristani-Firouzi M., Ptacek L. J., Tawil R., Schwartz P. J., George A. L., Horie M., Andelfinger G., Snow G. L., Fu Y. H., Ackerman M. J., Vincent G. M. (2005) Electrocardiographic features in Andersen-Tawil syndrome patients with KCNJ2 mutations: characteristic T-U-wave patterns predict the KCNJ2 genotype. Circulation 111, 2720– 2726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peters S., Schulze-Bahr E., Etheridge S. P., Tristani-Firouzi M. (2007) Sudden cardiac death in Andersen-Tawil syndrome. Europace 9, 162– 166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Atienza F., Almendral J., Moreno J., Vaidyanathan R., Talkachou A., Kalifa J., Arenal A., Villacastin J. P., Torrecilla E. G., Sanchez A., Ploutz-Snyder R., Jalife J., Berenfeld O. (2006) Activation of inward rectifier potassium channels accelerates atrial fibrillation in humans: evidence for a reentrant mechanism. Circulation 114, 2434– 2442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]