Abstract

Background

Atrial fibrillation (AF) has been linked to inflammatory factors and obesity. Epicardial fat is a source of several inflammatory mediators related to the development of coronary artery disease. We hypothesized that periatrial fat may have a similar role in the development of AF.

Methods and Results

Left atrium (LA) epicardial fat pad thickness was measured in consecutive cardiac CT angiograms performed for coronary artery disease or AF. Patients were grouped by AF burden: no (n=73), paroxysmal (n=60), or persistent (n=36) AF. In a short-axis view at the mid LA, periatrial epicardial fat thickness was measured at the esophagus (LA-ESO), main pulmonary artery, and thoracic aorta; retrosternal fat was measured in axial view (right coronary ostium level). LA area was determined in the 4-chamber view. LA-ESO fat was thicker in patients with persistent AF versus paroxysmal AF (P=0.011) or no AF (P=0.003). LA area was larger in patients with persistent AF than paroxysmal AF (P=0.004) or without AF (P<0.001). LA-ESO was a significant predictor of AF burden even after adjusting for age, body mass index, and LA area (odds ratio, 5.30; 95% confidence interval, 1.39 to 20.24; P=0.015). A propensity score–adjusted multivariable logistic regression that included age, body mass index, LA area, and comorbidities was also performed and the relationship remained statistically significant (P=0.008).

Conclusions

Increased posterior LA fat thickness appears to be associated with AF burden independent of age, body mass index, or LA area. Further studies are necessary to examine cause and effect, and if inflammatory, paracrine mediators explain this association.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, inflammation, obesity, pericardium, tomography

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained arrhythmia in clinical practice1 and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.2 Although AF pathophysiology is complex, increasing evidence supports mechanistic links between inflammation and AF. AF has been associated with inflammatory conditions that involve the heart such as pericarditis and myocarditis.3,4 The incidence of AF after coronary artery bypass grafting is increased, with a peak frequency coincident with peak postoperative C-reactive protein (CRP) levels.5 In addition, CRP appears to be higher in patients with nonpostoperative AF and is associated with AF duration and persistence.6–8 Higher levels of CRP predict the future development of AF in patients without prior history of AF.9 Furthermore, atrial biopsies from patients with AF have shown evidence of inflammatory cells, suggesting that inflammation plays a role in the pathogenesis of AF.10–11

A relationship has been described between obesity, epi/pericardial fat, inflammation, and coronary atherosclerosis. Perivascular adipocytes secrete inflammatory cytokines, and the extent of epicardial fat is associated with the severity of coronary artery disease (CAD).12–16 Obesity is a risk factor for AF17 and has been associated with pericardial fat,13 but the potential relationship of periatrial epicardial fat and AF has not been previously described. We sought to test the hypothesis that periatrial epicardial fat is associated with AF.

Methods

Patient Population

We analyzed data from 169 consecutive patients, who underwent consecutive cardiac computed tomography (CT) angiograms between January and May 2008, for evaluation of AF or CAD. Subjects were identified from a cardiovascular CT registry. CT studies obtained for AF were performed in evaluation for AF catheter ablation (pulmonary vein isolation, [PVI]). Typically candidates for PVI at our institution are patients who have symptomatic AF despite medical therapy. The study was approved by the institutional review board with waiver of consent for medical records review and performed according to institutional guidelines.

Data retrospectively collected from patient medical records included age, sex, body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2), comorbidities (hypertension [HTN], hyperlipidemia [HPL], diabetes mellitus [DM], chronic kidney disease [CKD], CAD, congestive heart failure [CHF], and thyroid disease), history of AF, AF burden, and treatment by PVI. CAD, CHF, and AF burden were defined as per published guidelines.18–20 Patients were categorized according to their highest AF burden (no history of AF, paroxysmal AF, and persistent AF). Paroxysmal AF was defined as recurring AF terminating in 7 days or less. Persistent AF indicated a history of AF sustaining beyond 7 days.

Imaging Protocol

Patients with known AF (n=95) were evaluated with cardiac CT angiography for PVI. Multidetector row CT technology was used (Definition, Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany, or Brilliance 64, Philips Medical Systems, Cleveland, Ohio). The specific imaging protocol for the clinically indicated scans was adapted to minimize radiation exposure for each patient while ensuring acceptable image quality. ECG-referenced scans were performed after intravenous administration of contrast material. Because pulmonary vein assessment was the primary clinical goal, 1.5-mm-thick images were reconstructed. Patients evaluated for CAD (n=74) were imaged using the same scanner models. Again, the specific imaging protocol was adapted for each patient and the ECG-referenced scan performed after the intravenous administration of contrast material. For evaluation of the coronary arteries, 0.75-mm-thick slices were reconstructed. For optimal visualization of coronary anatomy, patients were premedicated with sublingual nitroglycerin and intravenous β-adrenergic blocker for coronary dilatation and heart rate control, respectively.

Image Analysis

Using a standard clinical workstation (Leonardo, Siemens), advanced 3D off-line postprocessing was performed. The 3D CT dataset was reconstructed to obtain standard cardiac views as used in echocardiography. We first reconstructed standard 2- and 4-chamber views. LA size was determined by manually tracing the LA borders in the 4-chamber view (making sure to exclude the pulmonary veins) and using computer software that calculates the outlined area. The short-axis view was reconstructed as a plane perpendicular to the long axis of these 2 views at the level of the mid LA (Figure 1). In this short-axis view, the periatrial epicardial fat thickness was measured (in cm) as the shortest distance between the mid left atrium (LA) wall and 3 anatomic landmarks: esophagus (LA-ESO), main pulmonary artery (LA-PA), and descending thoracic aorta (LA-TA) (Figures 2 and 3). These measurements were prospectively determined, based on preliminary reviews of representative CT scans before starting the study, which showed the esophagus, pulmonary artery, and thoracic aorta were readily identifiable anatomic structures that could be used to measure LA epicardial fat. Retrosternal fat thickness (RS) was measured at the level of the right coronary artery (RCA) ostium (Figure 4) in the axial view. RS fat was measured based on similar measurements of epicardial fat thickness used in previous echocardiographic studies evaluating the association of epicardial fat and CAD.14 Measurements were made using digital calipers by a single investigator (O.B.) with an intraobserver reproducibility of 0.957 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.909 to 0.979; intraclass correlation, same below) on measurements of epicardial fat and 0.984 (95% CI, 0.937 to 0.996) on measurements of LA area. In a sample of 30 randomly selected patients, the interobserver reliability was 0.948 (95% CI, 0.912 to 0.969) on measurements of epicardial fat and 0.978 (95% CI, 0.954 to 0.990) on measurements of LA area (by O.B. and P.S.). AF status was blinded to the investigators at the time of epicardial fat measurements.

Figure 1.

Reconstruction of the short-axis view. Standard 2-chamber (right upper figure) and 4-chamber (left lower figure) views are constructed first. The short-axis view (left upper figure) was reconstructed as a plane perpendicular to the long axis of these 2 views at the level of the mid left atrium as indicated by the red line.

Figure 2.

The heart in the short-axis view at the level of the mid LA. In this view, the thickness of the epicardial fat can be demonstrated between the LA and 3 anatomic landmarks: esophagus, main pulmonary artery, and descending thoracic aorta. Actual measurements were taken after window optimization for each location. PA indicates main pulmonary artery; LA, left atrium; ASC AO, ascending aorta; DES AO, descending aorta; ESO, esophagus; LA-PA, peri-atrial epicardial fat located between mid left atrium and pulmonary artery; LAESO, periatrial epicardial fat located between mid left atrium and esophagus; and LA-TA, periatrial epicardial fat located between mid left atrium and thoracic aorta. Orientation cube: A indicates anterior; F, feet; and L, left.

Figure 3.

Magnified short-axis view of the periatrial fat pad between the esophagus and mid LA demonstrating measurement of the LA-ESO fat pad thickness. There are 5 different layers identifiable starting from the LA cavity to the esophageal lumen in order: The left atrial cavity with radiocontrast is most radiodense, a thin LA wall that is less radiodense than the LA cavity, a relatively radiolucent layer of epicardial fat, the esophageal muscle wall, and the esophageal lumen with the radiodensity of air. DES AO indicates descending aorta; ESO, esophagus; LA, left atrium; and LA-ESO, periatrial epicardial fat located between mid left atrium and esophagus. Orientation cube: A indicates anterior; L, left; and F, feet.

Figure 4.

The heart in the axial view at the level of the RCA ostium. Measurement of the RS fat was determined in this view as the shortest distance (indicated by the white double arrow) between the ventricular wall and the parietal pericardium at the level of the RCA ostium (indicated by the anteriorly directed RS white arrow). Orientation cube: F indicates feet.

Statistical Methods

AF burden was analyzed by grade (no AF=0, paroxysmal=1, persistent=2). Continuous variables were compared using 1-way analysis of variance and were reported as mean±standard deviation if normally distributed, or they were compared using Kruskal-Wallis test and were reported as median±interquartile range if not normally distributed. Pearson χ2 analysis was used to compare categorical variables. Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons was applied after the overall 3 group comparisons.

Univariable and multivariable ordinal logistic regression models were constructed to test the association between periatrial LA-ESO fat thickness and AF burden. In the multivariable model, the covariates were age, BMI, and LA area. The proportional odds assumption was tested. Propensity scores were estimated by running logistic regression using the 75 percentile of LA-ESO as the response variable and age, BMI, LA area, and patient characteristics (sex, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, CAD, congestive heart failure, and hypothyroidism) as the covariates. A propensity score–adjusted multivariable logistic regression was then performed to adjust for imbalances of the registry data.

Missing data of LA-ESO and BMI were imputed using overall mean imputation, and the imputed data were used to run logistic regressions as a supplement to the analyses of the original data. Statistical testing was 2-sided and results were considered statistically significant at the level of P<0.05, or at P<0.015 after Bonferroni correction. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Patient Characteristics

Patient characteristics of the entire study are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of the 169 patients included in this study was 54.6±13.2 years (range, 15 to 82 years); 34.9% of patients were female. The mean BMI was 29.2±6.1 kg/m2. In this study population, 73 (43.2%) patients did not have AF, 60 (35.5%) had paroxysmal AF, and 36(21.3%) had persistent AF. Comorbid conditions included CAD (15.4%), HTN (42.9%), HPL (41.6%), DM (7.1%), CHF (5.8%), CKD (1.9%), and thyroid disease (12.3%).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics and Biomarkers by AF Burden

| Total Population | No AF | Paroxysmal AF | Persistent AF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 169 | 73 (43.2) | 60 (35.5) | 36 (21.3) |

| Age, y, mean±SD* | 54.6±13.2 | 50.1±12.8 | 58.1±12.4 | 58.0±12.9 |

| Female, n (%) | 59 (34.9) | 30 (41.1) | 18 (30.0) | 11 (30.6) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean±SD (n) | 29.2±6.1 (140) | 29.2±5.9 (47) | 27.8±6.1 (59) | 31.4±6.0 (34) |

| Comorbidities, n (%)† | ||||

| CAD* | 26 (15.4) | 19 (26.0) | 6 (10.0) | 1 (2.8) |

| HTN | 66 (42.9) | 23 (39.7) | 25 (41.7) | 18 (50.0) |

| HPL | 64 (41.6) | 20 (34.5) | 26 (43.3) | 18 (50.0) |

| DM | 11 (7.1) | 5 (8.6) | 6 (10.0) | 0 |

| CHF | 9 (5.8) | 2 (3.4) | 4 (6.7) | 3 (8.3) |

| CKD | 3 (1.9) | 1 (1.7) | 2 (3.3) | 0 |

| Hypothyroidism | 16 (10.4) | 5 (8.6) | 7 (11.7) | 4 (11.1) |

| Hyperthyroidism | 3 (1.9) | 0 | 2 (3.3) | 1 (2.8) |

P<0.015 when comparing age of no AF versus paroxysmal AF (P=0.001) and no AF versus persistent AF (P=0.007) and prevalence of CAD in no AF versus persistent AF (P=0.003). All other comparisons, P>0.015. Bonferroni adjustment was applied in the multiple comparisons.

Fifteen patients had incomplete documentation of their medical history in their medical records (excluding AF or CAD, which were available in the CT report) and were treated as missing in terms of comorbidities.

Characteristics by AF Burden

As shown in Table 1, patients without AF were younger than patients with paroxysmal AF (P=0.001) and persistent AF (P=0.007), respectively. The BMI of patients without AF (P=0.311) or with paroxysmal AF (P=0.018) and patients with persistent AF was not significantly different at the 0.015 significance level. The trend of a greater prevalence of CAD in patients without AF (versus paroxysmal AF P=0.019; versus persistent AF P=0.003) probably reflected the initial indications for CT angiography. Patients specifically evaluated for CAD had a higher pretest probability of having CAD than patients who had the cardiac CT before PVI. Differences in other comorbid factors were not statistically significant.

Periatrial and RS Fat and LA Area Versus AF Burden

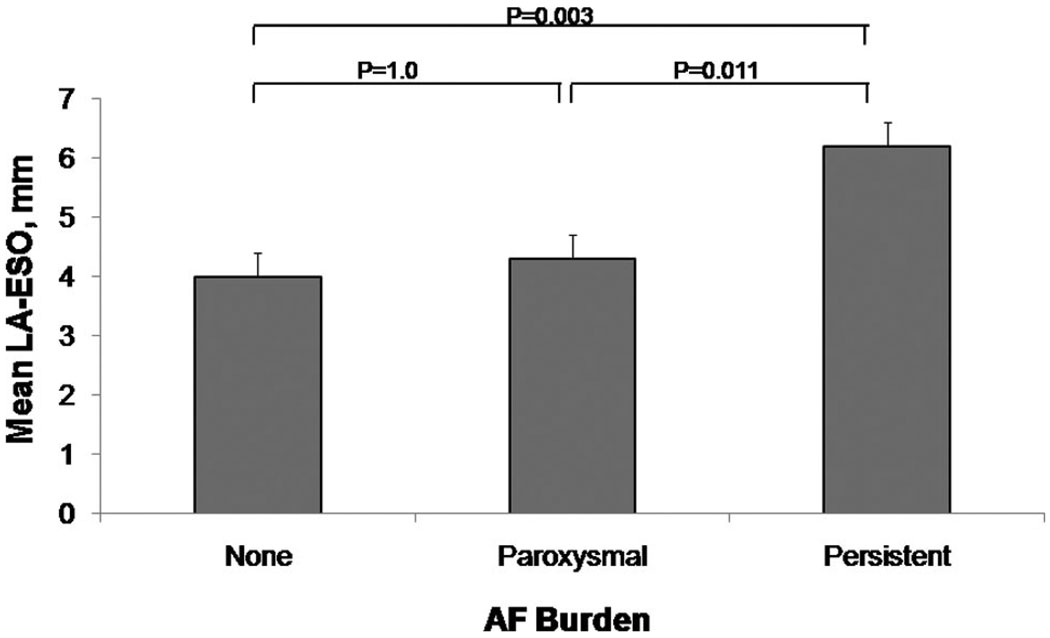

Periatrial and RS fat measurements by AF burden are summarized in Table 2. Patients with persistent AF had a significantly thicker LA-ESO fat pad as compared with patients with no AF (P=0.003) or with paroxysmal AF (P=0.011). A stepwise trend toward increasing LA-ESO thickness was observed in patients with increasing AF burden and is depicted in Figure 5.

Table 2.

Left Atrial Size and Periatrial and Retrosternal Fat Thickness

| Periatrial Fat Thickness (cm) | Total Population | No AF | Paroxysmal AF | Persistent AF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LA-PA, cm, median (IQR) | 0.65 (0.44, 0.94) (n=157) | 0.68 (0.44, 0.94) (n=68) | 0.66 (0.45, 0.96) (n=56) | 0.55 (0.41, 0.72) (n=33) |

| LA-ESO, cm, median (IQR)* | 0.40 (0.25, 0.59) (n=139) | 0.34 (0.21, 0.52) (n=56) | 0.39 (0.27, 0.54) (n=55) | 0.56 (0.40, 0.69) (n=28) |

| LA-TA, cm, median (IQR) | 0.58 (0.39, 0.90) (n=148) | 0.53 (0.39, 0.95) (n=62) | 0.59 (0.41, 0.89) (n=55) | 0.61 (0.39, 0.74) (n=31) |

| RS fat, cm, mean±SD | 0.70±0.42 (n=164) | 0.78±0.49 (n=72) | 0.64±0.32 (n=57) | 0.64±0.36 (n=35) |

| LA area, cm2, mean±SD* | 21.2±6.76 (n=169) | 18.6±4.45 (n=73) | 21.6±6.97 (n=60) | 25.8±7.77 (n=36) |

P<0.015 when comparing LA-ESO in no AF versus persistent AF (P=0.003) and paroxysmal AF versus persistent AF (P=0.011) and LA area in no AF versus persistent AF (P<0.001) and paroxysmal AF versus persistent AF (P=0.004). All other comparisons, P>0.015. Bonferroni adjustment was applied in the multiple comparisons.

Figure 5.

Relationship of mean epicardial fat thickness between the esophagus and the mid left atrium and atrial fibrillation burden. There is a trend toward increasing epicardial fat thickness between the esophagus and the mid left atrium (LA-ESO) in patients with higher burden of AF. Patients with persistent AF have a significantly thicker mean LA-ESO fat pad than patients with no AF or with paroxysmal AF.

The thickness of the RS fat pad at the level of the RCA takeoff was compared according to AF burden (Table 2). RS fat pad thickness was not associated with AF burden.

LA area was found to be larger in patients with persistent AF than in paroxysmal AF (P=0.004) or in patients without AF (P<0.001). This is shown in Table 2.

Regression Analysis

The association between AF burden by grade (no AF=0, paroxysmal=1, persistent=2) and periatrial LA-ESO fat thickness was assessed by ordinal logistic regression. Univariately, LA-ESO was a significant predictor of AF burden (odds ratio, 6.06 [associated with a 1-cm increase in LA-ESO]; 95% CI, 1.90 to 19.25; P=0.002). After adjusting for age, BMI, and LA area, the association remained significant (odds ratio, 5.30; 95% CI, 1.39 to 20.24; P=0.015). The assumption of proportional odds was satisfied. Given that it was a registry study of imbalanced data, propensity scores were estimated in a logistic regression model by setting 75% percentile of LA-ESO as the outcome variable and age, BMI, LA area, and patient characteristics (sex, HTN, HPL, DM, CAD, CHF, and hypothyroidism) as the covariates. A propensity score–adjusted multivariable logistic regression was then performed. The obtained odds ratio was 6.17 (95% CI, 1.60 to 23.85; P=0.008).

To offset missing data of LA-ESO and BMI in the small sample size, overall mean imputation was applied to get a complete set of data. For adjusted ordinal logistic regression, with the overall mean imputation the odds ratio was 5.09 (95% CI, 1.51 to 17.19; P=0.009).

Discussion

In an imaging analysis of 169 patients with cardiac CT, we found a significant, direct, relationship between AF burden and the thickness of the posterior periatrial fat pad between the esophagus and the left atrium. Furthermore, this relationship remained statistically significant after adjusting for BMI, age, LA area, and propensity score.

AF has been associated with obesity,17 as well as elevated CRP levels,5–9 a measure of systemic inflammation. Left atrial biopsies from patients with lone AF have shown inflammatory cells.10 Obesity has been related to pericardial fat deposits.13 A similar relationship between obesity, epicardial fat, and inflammation has been described for CAD. It is increasingly recognized that distinct fat depots (such as subcutaneous and visceral fat depots) differ in metabolic activity and in the proinflammatory mediators secreted.21 Epicardial adipose tissue is a form of visceral adipose tissue located between the myocardium and the parietal pericardium that shares a common embryonic origin with intraabdominal adiposity, a fat depot believed to play a role in metabolic syndrome.15,21–23 Epicardial fat is a source of several inflammatory mediators, including interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1. Paracrine interactions of these cytokines and mediators contribute to perivascular inflammation and the development of CAD.12–16,21–23 Because LA biopsies from patients with AF have shown evidence of inflammatory cells in the atrial tissue and a local inflammatory response may have a role in the development of AF,11 we hypothesized that periatrial fat may be associated with AF, perhaps as a promoter of AF persistence or reflective of the inflammatory changes associated with AF.

It is interesting that only the LA-ESO (esophageal) periatrial fat was found to be associated with AF burden in our study. Triggers that contribute to the initiation of AF are located in the pulmonary vein ostia.24 The esophagus follows a course along the posterior wall of the left atria and is in close anatomic proximity to the pulmonary vein ostia.25,26 Local inflammatory mediators produced by the periatrial epicardial fat in the LA posterior wall may promote the activation of ectopic foci in the pulmonary vein ostia. Moreover, posterior pericardiectomy during cardiac surgery has been associated with reduction in postoperative AF.27–30 This may in part be due to removal of the posterior esophageal pericardial fat pad.

Although epicardial adipose tissue is considered to be proinflammatory and is associated with metabolic syndrome and CAD, not all epicardial fat pads are similar. The heart is reported to have mainly 3 epicardial fat pads with parasympathetic ganglia: a fat pad on the anterior surface of the atria located between the aorta and the right pulmonary artery, a fat pad between the inferior vena-cava and left atrium, and one between the superior vena-cava and right atrium.31 Reports about the impact of surgical preservation of the anterior fat pad between the aorta and right pulmonary artery on postoperative AF have had conflicting results.31 Epicardial fat pad ablation in canine models did not suppress AF inducibility in the long term.32 Nevertheless, in this study, only LA-ESO, which has not been characterized as having abundant parasympathetic ganglia, was significantly associated with AF. Of interest, the LA-TA, LA-PA, and RS fat pads were not associated with AF in our study population and rather appear to decrease in size with AF burden, but this did not achieve statistical significance. It is possible that in a larger study, the trend toward thicker nonposterior fat pads in the no AF group might reach statistical significance or correlate with the higher prevalence of CAD in the no AF group. CAD has been associated with epicardial fat, and the nonposterior fat pads probably are in closer proximity to the coronary arteries rather than the pulmonary veins.

Histological analysis and molecular identification of inflammatory markers may be necessary in future studies to better explain this association and to determine whether targeting left atrial adiposity is rational as a therapeutic goal. Preliminary data suggest a role for statins in the primary and secondary prevention of AF, possibly due to their antiinflammatory effects.33–34 Although speculative, it is possible that patients with more posterior periatrial fat, such as patients with persistent AF, might derive more benefit from antiinflammatory therapy to help reduce AF burden.

Limitations

The AF and no AF groups may not represent all patients with and without AF. AF patients in this study were younger than the typical AF population, which may lead to a lower prevalence of certain age-associated medical conditions such as HTN. This may limit the applicability of our results to all AF patients. Similarly, patients in the no AF group were generally referred for evaluation for CAD and thus had a larger prevalence of CAD and associated medical conditions. This may have contributed to the trend toward thicker nonposterior LA fat thicknesses observed in the no AF group, as previous literature suggests a relationship between coronary atherosclerotic disease and pericardial fat. Optimally, a matched control without AF and without CAD should be used; however, this would require a prospective enrollment of such patients in a controlled trial. Nonetheless, propensity score–adjusted logistic regression was performed to adjust for imbalances of the registry data.

Although blinding was potentially limited by differences in slice thickness and labeling for studies that assessed CAD, the CT reading was blinded to AF status. Although thickness of periatrial fat along the atrial wall is variable,25,26 the mid LA was used as a landmark to measure periatrial fat using the shortest distance to the esophagus, pulmonary artery, and thoracic aorta. A similar method was also applied to RS fat measurements, using the ostium of the RCA as the landmark.

Our method of quantifying fat has limitations as it is unclear if the epicardial fat thicknesses based on a short-axis view at the mid left atrium is representative of overall LA epicardial fat. A better assessment of periatrial and RS fat may have been possible if an automated method to measure the periatrial fat volume were available. Although such analytic approaches have been described to analyze epicardial fat surrounding the entire heart,12,13 we are currently unaware of software allowing limited assessment of periatrial fat burden. Future software development may allow future studies to include volumetric assessments of periatrial fat. Nevertheless, given the possible specific significance found in this study of LA-ESO fat, the posteriorly located fat pad located near the pulmonary veins where AF triggers are located, focal fat quantification may continue to be of interest, in addition to global periatrial fat volumes. Volumetric assessments may also overcome variability in posterior LA fat measurements that may be related to dynamic changes in esophageal movement relative to the posterior LA wall.

Implications

In our study, we investigated whether or not LA epicardial fat is associated with atrial fibrillation. Our study suggests that the thickness of the posterior epicardial fat pad between the LA and the esophagus (LA-ESO), which can easily be measured using cardiac CT, is associated with an increased AF burden independent of the known AF risk factors of age, BMI, and LA size. This may be explained in part by its proximity to the pulmonary vein ostia, which have known contributions to AF pathogenesis. These findings have potential implications for better understanding of AF pathogenesis. Inflammation and inflammatory states have been not only associated with AF duration and persistence but also with the future development of AF in patients without prior history of AF. Although further studies are needed to determine the inflammatory role of the posterior LA epicardial fat pad and its cause-effect relationship with AF, measurement of LA-ESO thickness during cardiac CT may prove to have a similar role as other routinely measured inflammatory markers in relation to AF.

Conclusion

Increased posterior LA-ESO fat pad thickness appears to be associated with increased AF persistence, independent of age, BMI, and LA area. This first study to describe an association between LA pericardial fat and AF is hypothesis-generating but does not define causal connections. Future investigations are needed to further clarify the role of LA pericardial fat in AF and to study the potential inflammatory role of posterior periatrial adiposity at a microscopic and molecular level.

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE

Inflammation plays a prominent role in cardiovascular disease and has been the focus of intense cardiovascular research. Recently, epicardial fat has been shown to be associated with increased production of several markers of inflammation. Furthermore, it is postulated to exert a locally toxic effect on coronary arteries via perivascular inflammation, therefore contributing to coronary atherosclerosis. In our study, we investigated whether or not left atrial epicardial fat may be associated with atrial fibrillation, given its proximity to the pulmonary veins ostia, which have known implications in atrial fibrillation (AF) pathogenesis. Our study suggests that the thickness of the posterior epicardial fat pad between the left atrium (LA) and the esophagus (LA-ESO), which can easily be measured using cardiac computed tomography (CT), is associated with an increased AF burden independent of the known AF risk factors of age, body mass index, and LA size. These findings have potential implications for better understanding of AF pathogenesis. Inflammation and inflammatory states have not only been associated with AF duration and persistence, but also with future development of AF in patients without prior history of AF. Further studies are needed to determine whether the epicardial fat in the posterior LA causes inflammation and subsequent AF or is merely associated with inflammation and AF. Measurement of LA-ESO thickness during cardiac CT may prove to have a role similar to other routinely measured inflammatory markers in relation to AF.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by NIH/NHLBI grant R01 HL090620 (Drs Chung and Van Wagoner); Leducq Foundation 07-CVD 03 (Dr Van Wagoner); Atrial Fibrillation Innovation Center, State of Ohio (Drs Chung and Van Wagoner). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not reflect the views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

Reprints: Information about reprints can be found online at http://www.lww.com/reprints

Disclosures

Drs Tchou and Chung are subinvestigators on a pending research study with Siemens Medical Solutions. Dr Halliburton participates in research funded by Siemens Medical Solutions and received modest honoraria (<$10 000) from Phillips Medical Systems as an advisory board member.

References

- 1.Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, Chang Y, Henault LE, Selby JV, Singer DE. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the Anticoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA. 2001;285:2370–2375. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.18.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kannel WB, Abbott RD, Savage DD, McNamara PM. Epidemiologic features of chronic atrial fibrillation: the Framingham study. N Engl J Med. 1982;306:1018–1022. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198204293061703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spodick DH. Arrhythmias during acute pericarditis: a prospective study of 100 consecutive cases. JAMA. 1976;235:39–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morgera T, Di Lenarda A, Dreas L, Pinamonti B, Humar F, Bussani R, Silvestri F, Chersevani D, Camerini F. Electrocardiography of myocarditis revisited: clinical and prognostic significance of electrocardiographic changes. Am Heart J. 1992;124:455–467. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(92)90613-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruins P, te Velthuis H, Yazdanbakhsh AP, Jansen PG, van Hardevelt FW, de Beaumont EM, Wildevuur CR, Eijsman L, Trouwborst A, Hack CE. Activation of the complement system during and after cardiopulmonary bypass surgery: postsurgery activation involves C-reactive protein and is associated with postoperative arrhythmia. Circulation. 1997;96:3542–3548. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.10.3542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watanabe T, Takeishi Y, Hirono O, Itoh M, Matsui M, Nakamura K, Tamada Y, Kubota I. C-reactive protein elevation predicts the occurrence of atrial structural remodeling in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Heart Vessels. 2005;20:45–49. doi: 10.1007/s00380-004-0800-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Psychari SN, Apostolou TS, Sinos L, Hamodraka E, Liakos G, Kremastinos DT. Relation of elevated C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 levels to left atrial size and duration of episodes in patients with atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:764–767. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung MK, Martin DO, Sprecher D, Wazni O, Kanderian A, Carnes CA, Bauer JA, Tchou PJ, Niebauer MJ, Natale A, Van Wagoner DR. C-reactive protein elevation in patients with atrial arrhythmias: inflammatory mechanisms and persistence of atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2001;104:2886–2891. doi: 10.1161/hc4901.101760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aviles RJ, Martin DO, Apperson-Hansen C, Houghtaling PL, Rautaharju P, Kronmal RA, Tracy RP, Van Wagoner DR, Psaty BM, Lauer MS, Chung MK. Inflammation as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2003;108:3006–3010. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000103131.70301.4F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frustaci A, Chimenti C, Bellocci F, Morgante E, Russo MA, Maseri A. Histological substrate of atrial biopsies in patients with lone atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 1997;96:1180–1184. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.4.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakamura Y, Nakamura K, Fukushima-Kusano K, Ohta K, Matsubara H, Hamuro T, Yutani C, Ohe T. Tissue factor expression in atrial endothelium associated with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: possible involvement in intracardiac thrombogenesis. Thromb Res. 2003;111:137–142. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(03)00405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taguchi R, Takasu J, Itani Y, Yamamoto R, Yamamoto R, Yokoyama K, Watanabe S, Masuda Y. Pericardial fat accumulation in men as a risk factor for coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2001;157:203–209. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(00)00709-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosito GA, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U, Ruberg FL, Mahabadi AA, Vasan RS, O’Donnell CJ, Fox CS. Pericardial fat, visceral abdominal fat, cardiovascular disease risk factors, and vascular calcification in a community-based sample: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:605–613. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.743062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeong J, Jeong M, Yun K, Oh SK, Park EM, Kim YK, Rhee SJ, Lee EM, Lee J, Yoo NJ, Kim NH, Park JC. Echocardiographic epicardial fat thickness and coronary artery disease. Circ J. 2007;71:536–539. doi: 10.1253/circj.71.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Vos AM, Prokop M, Roos CJ, Meijs MF, van der Schouw YT, Rutten A, Gorter PM, Cramer MJ, Doevendans PA, Rensing BJ, Bartelink ML, Velthuis BK, Mosterd A, Bots ML. Peri-coronary epicardial adipose tissue is related to cardiovascular risk factors and coronary artery calcification in post-menopausal women. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:777–783. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahabadi AA, Massaro JM, Rosito GA, Levy D, Murabito JM, Wolf PA, O’Donnell CJ, Fox CS, Hoffmann U. Association of pericardial fat, intrathoracic fat, and visceral abdominal fat with cardiovascular disease burden: the Framingham Heart Study. Eur Heart J. 2009 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn573. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang TJ, Parise H, Levy D, D’Agostino RB, Sr, Wolf PA, Vasan RS, Benjamin EJ. Obesity and the risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation. JAMA. 2004;292:2471–2477. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.20.2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel MR, Dehmer GJ, Hirshfeld JW, Smith PK, Spertus JA. Appropriateness Criteria for Coronary Revascularization: A Report by the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriateness Criteria Task Force, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Heart Association, and the Echocardiography, the Heart Failure Society of America, and the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:530–553. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, Jessup M, Konstam MA, Mancini DM, Michl K, Oates JA, Rahko PS, Silver MA, Stevenson LW, Yancy CW, Antman EM, Smith SC, Jr, Adams CD, Anderson JL, Faxon DP, Fuster V, Halperin JL, Hiratzka LF, Jacobs AK, Nishimura R, Ornato JP, Page RL, Riegel B. ACC/AHA 2005 Guideline Update for the Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Heart Failure in the Adult. A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure): Developed in Collaboration With the American College of Chest Physicians and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2005;112:e154–e235. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.167586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fuster V, Rydén LE, Cannom DS, Crijns HJ, Curtis AB, Ellenbogen KA, Halperin JL, Le Heuzey JY, Kay GN, Lowe JE, Olsson SB, Prystowsky EN, Tamargo JL, Wann S. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation) Developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2006;114:700–752. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chatterjee TL, Stol LL, Denning GM, Harrelson A, Blomkalns AL, Idelman G, Rothenberg FG, Neltner B, Romig-Martin SA, Dickson EW, Rudich S, Weintraub NL, Weintraub Proinflammatory phenotype of perivascular adipocytes influence of high-fat feeding. Circ Res. 2009;104:416–418. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Després J, Lemieux I, Bergeron J. Abdominal obesity and the metabolic syndrome: contribution to global cardiometabolic risk. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1039–1049. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.159228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mazurek T, Zhang L, Zalewski A, Mannion JD, Diehl JT, Arafat H, Sarov-Blat L, O’Brien S, Keiper EA, Johnson AG, Martin J, Goldstein BJ, Shi Y. Human epicardial adipose tissue is a source of inflammatory mediators. Circulation. 2003;108:2460–2466. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000099542.57313.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haissaguerre M, Jais P, Shah DC, Takahashi A, Hocini M, Quiniou G, Garrigue S, Le Mouroux A, Le Métayer P, Clémenty J. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:659–666. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809033391003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lemola K, Sneider M, Desjardins B, Case I, Han J, Good E, Tamirisa K, Tsemo A, Chugh A, Bogun F, Pelosi F, Jr, Kazerooni E, Morady F, Oral H. Computed tomographic analysis of the anatomy of the left atrium and the esophagus: implications for left atrial catheter ablation. Circulation. 2004;110:3655–3660. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000149714.31471.FD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sánchez-Quintana D, Cabrera J, Climent V, Farré J, Mendonça M, Ho S. Anatomic relations between the esophagus and left atrium and relevance for ablation of atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2005;112:1400–1405. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.551291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuralay E, Ozal E, Demirkili U, Tatar H. Effect of posterior pericardiotomy on postoperative supraventricular arrhythmias and late pericardial effusion (posterior pericardiotomy) J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;118:492–495. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(99)70187-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Asimakopoulos G, Della Santa R, Taggart DP. Effects of posterior pericardiotomy on the incidence of atrial fibrillation and chest drainage after coronary revascularization: a prospective randomized trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;113:797–799. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(97)70242-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farsak B, Gunaydin S, Tokmakoglu H, Kandemir O, Yorgancioglu C, Zorlutuna Y. Posterior pericardiotomy reduces the incidence of supra-ventricular arrhythmias and pericardial effusion after coronary artery bypass grafting. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;22:278–281. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00259-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Biancari F, Asim Mahar MA. Meta-analysis of randomized trials on the efficacy of posterior pericardiotomy in preventing atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.07.012. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.White CM, Sander S, Coleman CI, Gallagher R, Takata H, Humphrey C, Henyan N, Gillespie EL, Kluger J. Impact of epicardial anterior fat pad retention on postcardiothoracic surgery atrial fibrillation incidence: the AFIST-III Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:298–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oh S, Zhang Y, Bibevski S, Marrouche NF, Natale A, Mazgalev TN. Vagal denervation and atrial fibrillation inducibility: epicardial fat pad ablation does not have long-term effects. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:701–708. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Young-Xu Y, Jabbour S, Goldberg R, Blatt CM, Graboys T, Bilchik B, Ravid S. Usefulness of statin drugs in protecting against atrial fibrillation in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:1379–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siu CW, Lau CP, Tse HF. Prevention of atrial fibrillation recurrence by statin therapy in patients with lone atrial fibrillation after successful cardioversion. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:1343–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]