Abstract

Background

Most patients with ovarian cancer are diagnosed with advanced stage disease (i.e., stage III-IV), which is associated with a poor prognosis. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in stage III serous ovarian carcinoma compared to normal tissue were screened by a new differential display method, the annealing control primer (ACP) system. The potential targets for markers that could be used for diagnosis and prognosis, for stage III serous ovarian cancer, were found by cluster and survival analysis.

Methods

The ACP-based reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT PCR) technique was used to identify DEGs in patients with stage III serous ovarian carcinoma. The DEGs identified by the ACP system were confirmed by quantitative real-time PCR. Cluster analysis was performed on the basis of the expression profile produced by quantitative real-time PCR and survival analysis was carried out by the Kaplan-Meier method and Cox proportional hazards multivariate model; the results of gene expression were compared between chemo-resistant and chemo-sensitive groups.

Results

A total of 114 DEGs were identified by the ACP-based RT PCR technique among patients with stage III serous ovarian carcinoma. The DEGs associated with an apoptosis inhibitory process tended to be up-regulated clones while the DEGs associated with immune response tended to be down-regulated clones. Cluster analysis of the gene expression profile obtained by quantitative real-time PCR revealed two contrasting groups of DEGs. That is, a group of genes including: SSBP1, IFI6 DDT, IFI27, C11orf92, NFKBIA, TNXB, NEAT1 and TFG were up-regulated while another group of genes consisting of: LAMB2, XRCC6, MEF2C, RBM5, FOXP1, NUDCP2, LGALS3, TMEM185A, and C1S were down-regulated in most patients. Survival analysis revealed that the up-regulated genes such as DDAH2, RNase K and TCEAL2 might be associated with a poor prognosis. Furthermore, the prognosis of patients with chemo-resistance was predicted to be very poor when genes such as RNase K, FOXP1, LAMB2 and MRVI1 were up-regulated.

Conclusion

The DEGs in patients with stage III serous ovarian cancer were successfully and reliably identified by the ACP-based RT PCR technique. The DEGs identified in this study might help predict the prognosis of patients with stage III serous ovarian cancer as well as suggest targets for the development of new treatment regimens.

Background

Ovarian cancer is a complex disease, characterized by successive accumulation of multiple molecular alterations in both the cells undergoing neoplastic transformation and host cells [1]. These anomalies disturb the expression of genes that control critical cell processes, leading to the initiation of tumorigenesis and development. At the time of diagnosis most patients with ovarian cancer have advanced stage disease (i.e., stage III-IV) where surgery and chemotherapy results in an approximately 25% overall 5-year survival rate. Consequently, ovarian cancer is the leading cause of death from a gynecological malignancy. Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) accounts for 90% of all ovarian cancers; there is significant heterogeneity within the EOC group. For example, histologically defined subtypes such as serous, endometrioid, mucinous, and low- and high-grade malignancies all have variable clinical manifestations and underlying molecular signatures [2].

Gene expression has been extensively applied to screening for the prognostic factors associated with ovarian cancer; identification of such factors would help to determine patient prognosis. Studies have focused on differential gene expression between tumor and normal tissues [3], distinguishing between histological subtypes [4] and identifying differences between invasive tumors and those with low malignant potential [5]. However, to date, the use of differentially expressed genes (DEG) have not been implemented in ovarian cancer therapies; this is mainly because their reliability and validity have not yet been well established. Microarray technology permits large scale analysis of expression surveys to identify the genes that have altered expression as a result of disease. However, microarray data is notorious for its unreliable reproducibility of DEGs across platforms and laboratories, as well as validation problems associated with prognostic signatures [6]. In addition, identification of a gene responsible for a specialized function during a certain biological stage can be difficult to determine because the gene might be expressed at low levels, whereas the bulk of mRNA transcripts within a cell are abundant [7].

To screen DEGs in low concentrations, while minimizing false positive results, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) based technique has been used. One screening method, differential display, requires PCR using short arbitrary primers. This method is simple, rapid and only requires small amounts of total RNA. However, many investigators have reported significantly high false-positive rates [8] and poor reproducibility of the results [9] because of nonspecific annealing by the short arbitrary primers. Recently, the annealing control primer (ACP) system has been developed; this technique provides a primer with annealing specificity to the template and allows only genuine products to be amplified [10]. The structure of the ACP includes (i) a 3" end region with a target core nucleotide sequence that substantially complements the template nucleic acid of hybridization; (ii) a 5" end region with a non-target universal nucleotide sequence; and (iii) a polydeoxyinosine [poly(dI)] linker bridging the 3" and 5" end sequences. Because of the high annealing specificity during PCR using the ACP system, the application of the ACP to DEG identification generates reproducible, accurate, and long (100 bp to 2 kb) PCR products that are detectable on agarose gels.

In this study, the ACP-based PCR method was used to identify the DEGs of patients with stage III serous ovarian cancer, the findings were compared to normal ovarian tissue. A total of 60 arbitrary ACPs were used and 114 DEGs were identified by sequencing differentially expressed bands. For the confirmation of differential expression of the DEGs, quantitative real-time PCR was performed on 38 selected DEGs; the results showed good agreement with the ACP findings. These results could be used as preliminary data for further study of the molecular mechanism underlying stage III serous ovarian cancer.

Methods

Patient information

After obtaining written informed consent from all patients included in the study, samples of primary epithelial ovarian cancer were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C. Analysis of tissues from patients was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Catholic University of Korea (Seoul, Korea). The histopathological diagnoses were determined using the WHO criteria, and the tumor histotype was serous adenocarcinoma in all patients. Classification of cancer stage and grade was performed according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO). A total of 16 patients with serous ovarian carcinoma were enrolled in this study, all patients were diagnosed as stage IIIC with high-grade cancer (grade 3).

ACP-based GeneFishing™ reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

Total RNAs from the ovarian tissues of the serous carcinoma were isolated by gentle homogenization using Trizol®. The normal human ovary total RNA was purchased from Stratagene (Total RNA Human Ovary, #540071). The RNA was used for the synthesis of first-strand cDNAs by reverse transcriptase. Reverse transcription was performed 1.5 hours at 42°C in a final reaction volume of 20 μl containing 3 μg of the purified total RNA, 4 μl of 5" reaction buffer (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), 5 μl of dNTPs (2 mmol each), 2 μl of 10 μM dT-ACP1 (5"-CTGTGAATGCTGCGACTACGATIIIII(T)18)-3", where "I" represents deoxyinosine), 0.5 μL of RNasin® RNase Inhibitor (40 U/μl, Promega), and 1 μl of Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (200 U/μl, Promega). First-strand cDNAs were diluted by the addition of 80 μL of RNase-free water for the GeneFishing PCR and stored -20°C until use.

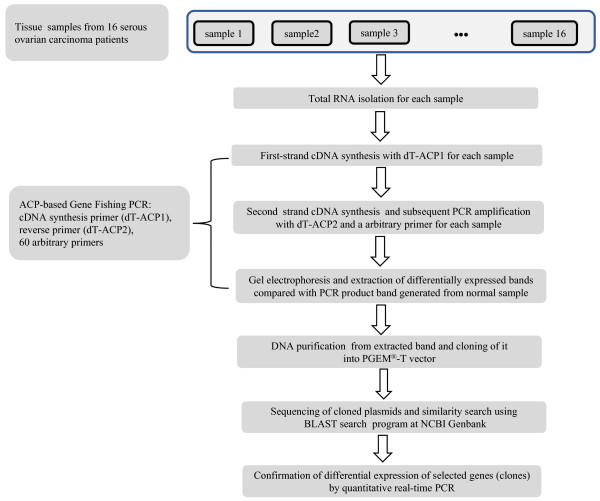

DEGs were screened by ACP-based PCR method using the GeneFishing™ DEG kits (Seegene, Seoul, South Korea). Briefly, second-strand cDNA synthesis was conducted at 50°C (low stringency) during one cycle of first-stage PCR in a final reaction volume of 49.5 μl containing 3-5 μl (about 50 ng) of diluted first-strand DNA cDNA, 5 μl of 10x PCR buffer plus Mg (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany), 5 μl of dNTP (each 2 mM), 1 μl of 10 μM dT-ACP2 (5'-CTGTGAATGCTGCGACTACGATIIIII(T)15-3"), and 1 μl of 10 μM arbitrary ACP. The tube containing the reaction mixture was kept at 94°C while 0.5 μl of Taq DNA polymerase was added to the reaction mixture (5 U/μl, Roche Applied Science). Sixty PCR reactions for each sample were carried out with 60 arbitrary ACPs, respectively. The PCR protocol for second-strand synthesis was one cycle at 94°C for 1 min, followed by 50°C for 3 min, and 72°C for 1 min. After completion of second-strand DNA synthesis, 40 cycles were performed. Each cycle involved denaturation at 94°C for 40 sec, annealing at 65°C for 40 sec, extension at 72°C for 40 sec, and a final extension at 72°C to complete the reaction. The amplified PCR products were separated in 2% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. The overall scheme of the experiment is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A schematic diagram of the experimental procedure.

Cloning and sequencing

The differentially expressed bands were extracted from the gel using the GENCLEAN® II Kit (Q-BIO gene, Carlsbad, CA.,USA), and directly cloned into a TOPO TA® cloning vector (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cloned plasmids were sequenced with an ABI PRISM® 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA., USA). Complete sequences were analyzed by searching for similarities using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) search program at the Genbank database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction and statistical analysis

For the confirmation of the differential expression of DEGs, quantitative real-time PCR was carried out for 38 DEGs selected from 114 DEGs. The concentrations of the reagents were adjusted to reach a final volume of 20 μL containing 5 ng of cDNA template, 10 μl of SYBR® Premis Ex Taq™ II (Takara Bio,Otsu, Japan), 0.4 μl of ROX™ reference Dye II, 0.4 μl of 10 μM forward and reverse primers of DEGs with β-actin as an internal control (Table 1). The cDNA templates were constructed with the total RNA extracted from 16 ovarian cancer tissues and normal human ovary total RNA. The PCR amplification protocol was 50°C for 2 min and 95°C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 60°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 30 sec. The real-time PCR analysis was performed on an Applied Biosystems Prism 7900 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). Relative quantification with the data obtained was performed according to the user's manual. The fold change for gene expression, between the cancer and normal samples, was calculated by using the threshold cycle (CT): fold change = 2-ΔΔCT, ΔΔCT = [(CT of gene of interest - CT of β-actin)cancer sample- (CT gene of interest - CT of β-actin)normal sample)]. The fold change was log2 transformed for the cluster and survival analysis. The R packages mclust and survival http://www.r-project.org were used for the cluster and survival analysis, respectively.

Table 1.

Primer sequences of 38 DEGs and β-actin used for the quantitative real-time PCR.

| DEG | Forward | Reverse | Amplicon size |

|---|---|---|---|

| NM_003143.1 | AAAGATCCCTGAATCGTGTGC | TCGCCACATCTCATTAGTTGC | 119 |

| AY871274 | GTCCACTGCACAGTTCGAGG | GGCCTCCTCTTTGCTGATTC | 279 |

| NM_022873.2 | CAGAAGGCGGTATCGCTTTTC | CCTGCATCCTTACCCGCATT | 89 |

| NM_001355.3 | AGCGCCCACTTCTTTGAGTTT | TCCCTATCTTGCCAATCTGCC | 106 |

| BC000523 | GTGCCTAAGACAGAAATTCGGG | TGCAAGTCTATGTTTGGGTTCAT | 174 |

| NM_005532 | GCAGCCTTGTGGCTACTCTG | TAGAACCTCGCAATGACAGCC | 112 |

| NM_207429.2 | GGAGCTCCTTGGAAGTCAGG | GCCAGCAACAGCACTGAGAT | 129 |

| BC012823 | CGCTCTCTTTTCTCCCGTTT | TCGCAGCATGCTCAACATTA | 236 |

| NM_020529 | CTCCGAGACTTTCGAGGAAATAC | GCCATTGTAGTTGGTAGCCTTCA | 135 |

| NM_001101654 | GTGCAATCGCCATTACTGCT | GAATGCAGGGTGTAAGGGGT | 248 |

| NM_001867 | AAAGGTCTTGGTGAGGTGCC | ACGGACCACAGAGGTTGTGA | 119 |

| BC013003 | TCAGCACCTTGGAACCTTTGA | AAGACACTCTCTCGGTAGTCATT | 100 |

| NM_000978 | TCCTCTGGTGCGAAATTCCG | CGTCCCTTGATCCCCTTCAC | 119 |

| NM_032470 | TTGTCCAGATAGCGGCAAAC | AGCGAGCTCTGGAAGAGGAG | 149 |

| NM_013974.1 | GGTCGATGGAGTCCGCAAAG | GGTGAAGAGAACGTCAGTGC | 100 |

| XM_002345433 | CGAGTTCGTGGACCTGTACG | GCCATTAAACCTGCCTGTGA | 127 |

| NM_001034996 | CATGCCGGAAAATTGGTCGC | CACTGTGCGGAAACTTGAGGA | 145 |

| NM_001037637 | CATCTCTGGCAGCGAACACTT | AGTCAGACTATCCGCACCAAG | 107 |

| BC107854 | AGGGGTAAGCTCATCGCAGT | CCGGAAAGTGTCTTCGATCTCA | 150 |

| NM_001020 | TCGGACGCAAGAAGACAGC | AGCAGCTTGTACTGTAGCGTG | 118 |

| NR_003225 | GAAACCCAAACCCTCAAGGA | GCACTTGGCTGTCCAGAAGA | 247 |

| NM_001004333.3 | ATTCCTTGCGCTTATTGAGCC | GCCCCCAGAACATATACAACCT | 123 |

| NM_080390 | TGCAGGGAGGATCAAAGACA | GGCTCTCCCTCACTCTCTGG | 103 |

| NM_013318 | AAGCCCTCTGGATCAGCAGT | TCAGTAGGGAGAGGCGAGGT | 227 |

| EF177379 | GTTTCCAGGCCTTGCTCA | ATTCATGGGCTCTGGAACAA | 158 |

| AK026649 | GGTTCTCGCTCTTGTCGTGTC | ATATCCTTCGCGTACTGACGG | 101 |

| AK302766 | TGGCTTTGTAACAAGTGCTGC | CGGAGCTATGTTCCGAAGAATG | 168 |

| NM_032682 | TCCCGTGTCAGTGGCTATGAT | CTCTTTAGGCTGTTTTCCAGCAT | 226 |

| NG_001229 | TCATGAGGCCCAGATCAAGA | ACCACGTCCTTCCCTTTCAG | 219 |

| AK025219 | AGGACCAGAACTGCAAGCTG | GCGCTCTTCCAAGTCAGTGA | 155 |

| BC001120 | GCAGACAATTTTTCGCTCCA | GCACTTGGCTGTCCAGAAGA | 287 |

| NM_032508.1 | ATGAACCTGAGGGGCCTCTT | TGATGCCATCCAAACGAAGGG | 106 |

| NM_002292.3 | ATGCTGGTGGAACGCTCAG | CTCGCCTTCAGTGGATGGC | 171 |

| AK293439 | GGTCCAGAAGGCTCTCAAGC | GGGCCTCAGGTAATGGTGTT | 265 |

| NM_001131005 | AGACATCGTGGAGGCATTGA | GTGGCAATAGGTTGGGGTTT | 263 |

| NM_201442 | CAAGTCCCATACAACAAACTCCA | CAGGAGCAGAAGTAACCACCA | 176 |

| BC023599 | TCCCTTGTCCGGAGGATATT | TAATGGATTCAATCATCTTTATTAACC | 164 |

| NM_001100167 | TCTGAAGAGTCCCCCAAATG | AATCCAGCACTTCCTCTCCA | 209 |

| β-actin | GGCTGTATTCCCCTCCATCG | CCAGTTGGTAACAATGCCATGT | 154 |

Results

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in stage III serous ovarian cancers

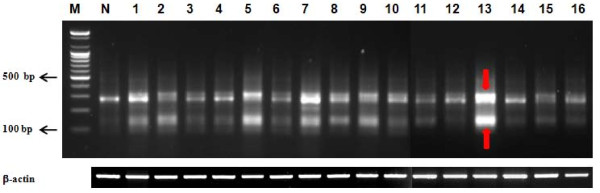

The patients included in this study ranged in age between 38 and 69 (mean age 53.3 ± 7.5 years). All 16 patients had a diagnosis of FIGO stage III papillary serous ovarian carcinoma. To identify genes that showed a predominant change of expression in patients with stage III serous ovarian cancer, the total RNAs from 16 serous ovarian tissues of stage III and the normal human ovary total RNA (Stratagene, #540071) were individually subjected to ACP-based RT PCR analysis using a combination of 60 arbitrary primers and two anchored oligo (dT) primers (dT-ACP1 and dT-ACP2). All PCR amplicons were compared on agarose gels (Figure 2). When the bands generated by the normal sample showed a clear difference compared to the bands generated on the cancer sample, the band was defined as a differentially expressed band. After all poor appearing bands were excluded, the differentially expressed bands were extracted, amplified using the TOPO TA Cloning Kit (Invitrogen, Cat. #K4500-1) and sequenced. The sequences of 114 DEGs were obtained. The DNA sequence of each DEG was analyzed by searching for similarities using the BLASTX program at the Genbank database (NIH, MD, USA). Table 2 shows the 114 DEGs assessed by Genbank and the best homologues.

Figure 2.

An example of GeneFishing™ using an arbitrary ACP in combination with an oligo (dT) ACP as indicated in the Methods section. M and N represents a 100-bp size marker generated by Forever 100-bp Ladder Personalizer (Seegene, Seoul, South Korea) and a normal sample, respectively. The lanes 1-16 include each of the cancer samples from the 16 patients. The bands showing a clear difference between the normal and cancer samples, here marked with a red arrow, were excised from the gel for further cloning and sequencing.

Table 2.

Annotation of the 114 DEGs by the BLAST search.

| Clone name | Annotation | GenBank accession no. | E-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| U1 | Homo sapiens acidic (leucine-rich) nuclear phosphoprotein 32 family, member B | BC013003 | 4.00E-112 |

| U2 | Homo sapiens adaptor-related protein complex 3, delta 1 subunit (AP3D1), transcript variant 2 | NM_003938 | 6.00E-10 |

| U3 | Homo sapiens adenine phosphoribosyltransferase (APRT), transcript variant 2 | NM_001030018 | 7.00E-08 |

| U4 | Homo sapiens genomic DNA, chromosome 11q, clone:CMB9-1B14, complete sequences | AP000659 | 4.00E-73 |

| U5 | Homo sapiens chromosome 19 open reading frame 53 (C19orf53) | NM_014047 | 1.00E-19 |

| U6 | Homo sapiens chromosome 1 open reading frame 115 (C1orf115) | NM_024709 | 5.00E-24 |

| U7 | Homo sapiens coatomer protein complex, subunit alpha (COPA), transcript variant 1 | NM_001098398 | 4.00E-22 |

| U8 | Homo sapiens dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 2 (DDAH2) | NM_013974.1 | 2.00E-123 |

| U9 | Homo sapiens dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 2 | BC001435 | 9.00E-168 |

| U10 | Homo sapiens dynein, light chain, LC8-type 1 (DYNLL1), transcript variant 3 | NM_003746 | 0.00E+00 |

| U11 | Homo sapiens ferritin, light polypeptide | BC004245 | 0.00E+00 |

| U12 | Homo sapiens glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase 2, mitochondrial (aspartate aminotransferase 2) (GOT2), nuclear gene encoding mitochondrial protein | NM_002080 | 7.00E-21 |

| U13 | Homo sapiens sarcoma antigen NY-SAR-48 | BC040564 | 3.00E-95 |

| U14 | Homo sapiens heat shock protein 90 kDa alpha (cytosolic), class B member 1 (HSP90AB1) | NM_007355.2 | 0.00E+00 |

| U15 | Homo sapiens interferon, alpha-inducible protein 27 (IFI27), transcript variant 2 | NM_005532 | 6.00E-99 |

| U16 | Homo sapiens interferon, alpha-inducible protein 6 (IFI6), transcript variant 3 | NM_022873.2 | 2.00E-35 |

| U17 | Homo sapiens iron-responsive element binding protein 2 (IREB2) | NM_004136 | 5.00E-66 |

| U18 | Homo sapiens keratinocyte associated protein 2 | BC029806 | 5.00E-71 |

| U19 | PREDICTED: Homo sapiens similar to ribosomal protein S21, transcript variant 2 (LOC100291837) | XM_002345433 | 1.00E-100 |

| U20 | Homo sapiens mesothelin (MSLN), transcript variant 1 | NM_005823 | 0.00E+00 |

| U21 | Homo sapiens nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, alpha (NFKBIA) | NM_020529 | 1.00E-95 |

| U22 | Homo sapiens nuclear distribution gene C homolog (A. nidulans) pseudogene 2 (NUDCP2) on chromosome 2 | NG_001229 | 1.00E-101 |

| U23 | Homo sapiens PRP8 pre-mRNA processing factor 8 homolog (S. cerevisiae) (PRPF8) | NM_006445.3 | 4.00E-110 |

| U24 | Homo sapiens RAB5B, member RAS oncogene family (RAB5B) | NM_002868 | 2.00E-123 |

| U25 | Homo sapiens cDNA FLJ76524 complete cds | AK289930 | 2.00E-79 |

| U26 | Homo sapiens cell growth-inhibiting protein 34 mRNA, complete cds | AY871274 | 0.00E+00 |

| U27 | Homo sapiens ribosomal protein L23 (RPL23) | NM_000978 | 1.00E-87 |

| U28 | Homo sapiens ribosomal protein L6 pseudogene 27 (RPL6P27) on chromosome 18 | NG_009652 | 2.00E-111 |

| U29 | Homo sapiens ribosomal protein S8 (RPS8) | NM_001012 | 2.00E-67 |

| U30 | Homo sapiens TRK-fused gene | BC023599 | 4.00E-79 |

| U31 | Homo sapiens ribosomal protein S8 | BC070875 | 1.00E-60 |

| U32 | Homo sapiens mRNA similar to eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3, subunit 7 (zeta, 66/67 kD) | BC011740 | 8.00E-142 |

| U33 | Homo sapiens ribosomal protein S24 | BC000523 | 4.00E-45 |

| U34 | Homo sapiens cDNA, FLJ18539 | AK311497 | 4.00E-26 |

| U35 | Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:2822193 | BC005845 | 8.00E-155 |

| U36 | Homo sapiens ATPase, H+ transporting, lysosomal 14 kDa, V1 subunit F | BC107854 | 3.00E-147 |

| U37 | Homo sapiens cytochrome c oxidase subunit VIIc (COX7C), nuclear gene encoding mitochondrial protein | NM_001867 | 5.00E-145 |

| U38 | Homo sapiens tenascin XB (TNXB), transcript variant XB-S | NM_032470 | 0.00E+00 |

| U39 | Homo sapiens septin 9 (SEPT9) on chromosome 17 | NG_011683 | 5.00E-45 |

| U40 | Homo sapiens chromosome 11 open reading frame 92 (C11orf92) | NM_207429.2 | 3.00E-45 |

| U41 | Homo sapiens D-dopachrome tautomerase (DDT), transcript variant 1 | NM_001355.3 | 5.00E-94 |

| U42 | Homo sapiens single-stranded DNA binding protein 1 (SSBP1) | NM_003143.1 | 0.00E+00 |

| D1 | Homo sapiens actin, beta (ACTB), | NM_001101.2 | 0.00E+00 |

| D2 | Homo sapiens acidic (leucine-rich) nuclear phosphoprotein 32 family, member B (ANP32B) | NM_006401.2 | 4.00E-115 |

| D3 | Homo sapiens Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) 17 (ARHGEF17) | NM_014786 | 7.00E-37 |

| D4 | Homo sapiens ATPase, H+ transporting, lysosomal 13kDa, V1 subunit G1 | BC003564 | 0.00E+00 |

| D5 | Homo sapiens UDP-Gal:betaGal beta 1,3-galactosyltransferase polypeptide 6 (B3GALT6) | NM_080605 | 8.00E-29 |

| D6 | Homo sapiens HLA-B associated transcript 2-like 1 (BAT2L1) | NM_013318 | 4.00E-121 |

| D7 | Homo sapiens cDNA FLJ77629 complete cds, highly similar to Homo sapiens bone marrow stromal cell antigen 2 (BST2) | AK291099 | 0.00E+00 |

| D8 | Homo sapiens basic transcription factor 3 (BTF3), transcript variant 1 | NM_001037637 | 0.00E+00 |

| D9 | Homo sapiens complement component 1, s subcomponent (C1S), transcript variant 1 | NM_201442 | 0.00E+00 |

| D10 | Homo sapiens CD74 molecule, major histocompatibility complex, class II invariant chain (CD74), transcript variant 1 | NM_001025159.1 | 8.00E-179 |

| D11 | Homo sapiens chloride intracellular channel 1 | BC064527 | 2.00E-143 |

| D12 | Homo sapiens CXXC finger 1 (PHD domain) (CXXC1), transcript variant 1 | NM_001101654 | 1.00E-180 |

| D13 | Homo sapiens early growth response 1 (EGR1) | NM_001964.2 | 0.00E+00 |

| D14 | Homo sapiens Finkel-Biskis-Reilly murine sarcoma virus (FBR-MuSV) ubiquitously expressed (FAU) | NM_001997 | 5.00E-99 |

| D15 | Homo sapiens F-box protein Fbx7 (FBX7) mRNA, complete cds | AF129537 | 2.00E-105 |

| D16 | Homo sapiens Fc fragment of IgG, receptor, transporter, alpha | BC008734 | 1.00E-79 |

| D17 | Homo sapiens forkhead box P1 (FOXP1), transcript variant 1 | NM_032682 | 2.00E-130 |

| D18 | Homo sapiens guanine nucleotide binding protein (G protein), beta polypeptide 1 | BC004186 | 1.00E-55 |

| D19 | Homo sapiens H19, imprinted maternally expressed transcript (non-protein coding) (H19), non-coding RNA | NR_002196 | 2.00E-34 |

| D20 | Homo sapiens high density lipoprotein binding protein (HDLBP), transcript variant 2 | NM_203346.2 | 0.00E+00 |

| D21 | Homo sapiens cDNA FLJ52975 complete cds, highly similar to Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins C | AK299923 | 0.00E+00 |

| D22 | Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:3898245 | BC010864 | 1.00E-138 |

| D23 | Homo sapiens cDNA fis, A-KAT03057, highly similar to Homo sapiens mitochondrion, ATP synthase 6 | AK026530 | 0.00E+00 |

| D24 | Homo sapiens cDNA: FLJ21566 fis, clone COL06467 | AK025219 | 0.00E+00 |

| D25 | Homo sapiens cDNA: FLJ22996 fis, clone KAT11938 | AK026649 | 4.00E-132 |

| D26 | Homo sapiens coiled-coil-helix-coiled-coil-helix domain containing 1 (CHCHD1) | NM_203298.1 | 0.00E+00 |

| D27 | Homo sapiens mRNA similar to guanine nucleotide binding protein-like 1 | BC048213 | 6.00E-29 |

| D28 | Homo sapiens mRNA similar to ribosomal protein L30 | BC012823 | 2.00E-131 |

| D29 | Homo sapiens ribosomal protein, large, P1 | BC053844 | 5.00E-152 |

| D30 | Homo sapiens sarcoma antigen NY-SAR-71 mRNA, partial cds | AY211920 | 1.00E-138 |

| D31 | Homo sapiens tumor necrosis factor, alpha-induced protein 1 (endothelial) | BC006208 | 8.00E-116 |

| D32 | Homo sapiens zinc finger, FYVE domain containing 20 | BC021246 | 1.00E-138 |

| D33 | Homo sapiens heat shock factor binding protein 1 (HSBP1) | NM_001537 | 1.00E-121 |

| D34 | Homo sapiens HtrA serine peptidase 1 (HTRA1) on chromosome 10 | NG_011554 | 0.00E+00 |

| D35 | Human mitochondrial specific single stranded DNA binding protein mRNA, complete cds | M94556 | 1.00E-146 |

| D36 | Homo sapiens immunoglobulin kappa constant | BC095490 | 0.00E+00 |

| D37 | Homo sapiens immunoglobulin lambda locus, mRNA (cDNA clone MGC:88803 IMAGE:4765294), complete cds | BC073786 | 3.00E-101 |

| D38 | Homo sapiens jun B proto-oncogene (JUNB) gene, complete cds | AY751746 | 2.00E-20 |

| D39 | Homo sapiens L antigen family, member 3, mRNA (cDNA clone MGC:23038 IMAGE:4899044), complete cds | BC015744 | 6.00E-29 |

| D40 | Homo sapiens laminin, beta 2 (laminin S) (LAMB2) | NM_002292.3 | 0.00E+00 |

| D41 | Homo sapiens lectin, galactoside-binding, soluble, 1, mRNA (cDNA clone MGC:1818 IMAGE:2967299), complete cds | BC001693 | 5.00E-52 |

| D42 | Homo sapiens lectin, galactoside-binding, soluble, 3, mRNA (cDNA clone MGC:2058 IMAGE:3050135), complete cds | BC001120 | 0.00E+00 |

| D43 | Homo sapiens lectin, galactoside-binding, soluble, 3 (LGALS3), transcript variant 2, non-coding RNA | NR_003225 | 0.00E+00 |

| D44 | Homo sapiens mRNA for LGALS3 protein variant protein | AB209391 | 0.00E+00 |

| D45 | PREDICTED: Homo sapiens similar to ribosomal protein L13a (LOC100293761) | XM_002344734 | 8.00E-51 |

| D46 | Homo sapiens mediator complex subunit 1 (MED1) | NM_004774 | 1.00E-62 |

| D47 | Homo sapiens mediator complex subunit 14 (MED14) | NM_004229 | 3.00E-49 |

| D48 | Homo sapiens myocyte enhancer factor 2C (MEF2C), transcript variant 2 | NM_001131005 | 1.00E-99 |

| D49 | Homo sapiens murine retrovirus integration site 1 homolog (MRVI1), transcript variant 4 | NM_001100167 | 0.00E+00 |

| D50 | Homo sapiens myosin light chain kinase (MYLK), transcript variant 3A | NM_053027 | 2.00E-97 |

| D51 | Homo sapiens cDNA FLJ53659 complete cds, highly similar to Myosin light chain kinase, smooth muscle | AK300610 | 0.00E+00 |

| D52 | Homo sapiens nuclear receptor co-repressor 2 (NCOR2), transcript variant 1 | NM_006312.3 | 0.00E+00 |

| D53 | Homo sapiens nuclear enriched abundant transcript 1 (NEAT1) mRNA, complete sequence | EF177379 | 1.00E-80 |

| D54 | Homo sapiens trophoblast MHC class II suppressor mRNA, complete sequence | AF508303 | 1.00E-67 |

| D55 | Homo sapiens cDNA FLJ53682 complete cds, highly similar to RNA-binding protein 5 | AK302766 | 2.00E-153 |

| D56 | Homo sapiens RNA binding motif protein 5 | BC002957 | 2.00E-153 |

| D57 | Homo sapiens RNA binding motif protein 8A (RBM8A) | NM_005105.2 | 1.00E-135 |

| D58 | Homo sapiens ribonuclease, RNase K (RNASEK) | NM_001004333.3 | 6.00E-99 |

| D59 | Homo sapiens ribosomal protein L14 (RPL14), transcript variant 1 | NM_001034996 | 0.00E+00 |

| D60 | Homo sapiens ribosomal protein L27a (RPL27A) | NM_000990 | 4.00E-171 |

| D61 | Homo sapiens ribosomal protein L29 (RPL29) | NM_000992.2 | 6.00E-154 |

| D62 | Homo sapiens ribosomal protein S16 (RPS16) | NM_001020 | 7.00E-136 |

| D63 | Homo sapiens ribosomal protein S20 (RPS20), transcript variant 2 | NM_001023 | 0.00E+00 |

| D64 | Homo sapiens ribosomal protein S21 (RPS21) | NM_001024 | 8.00E-122 |

| D65 | Homo sapiens single-stranded DNA binding protein 1 | BC000895 | 1.00E-146 |

| D66 | Homo sapiens transcription elongation factor A (SII)-like 2 (TCEAL2) | NM_080390 | 0.00E+00 |

| D67 | Homo sapiens tubulointerstitial nephritis antigen-like 1 (TINAGL1) | NM_022164 | 2.00E-153 |

| D68 | Homo sapiens transmembrane protein 185A (TMEM185A) | NM_032508.1 | 0.00E+00 |

| D69 | Homo sapiens cDNA FLJ57738 complete cds, highly similar to Translationally-controlled tumor protein | AK296587 | 2.00E-104 |

| D70 | Homo sapiens X-ray repair complementing defective repair in Chinese hamster cells 6 (XRCC6) | NM_001469.3 | 0.00E+00 |

| D71 | Homo sapiens cDNA FLJ53970 complete cds, highly similar to ATP-dependent DNA helicase 2 subunit 1 | AK293439 | 0.00E+00 |

| D72 | Homo sapiens phosphodiesterase 7B (PDE7B) on chromosome 6 | NG_011994 | 3.00E-41 |

The prefix U and D in the clone name represent the clone from the up- and down-regulated bands in the agarose gel. The expression of DEGs marked in bold was further confirmed by quantitative real-time PCR.

The DEGs identified from the clones that were up-regulated included: AP000659 (U4, ARHGEF12), NM_013974.1 (U8, DDAH2), NM_022873.2 (U16, IFI6), NM_020529 (U21, NFKBIA), BC023599 (U30, TFG), and NG_011683 (U39, SEPT9). The up-regulation of SEPT9 mRNA was reported in a bank of ovarian tumors, which included benign, borderline and malignant tumors [11]. The genes including DDAH2, IFI6 and NFKBIA are known to be involved in the apoptosis inhibitory process while ARHGEF12 and TGF have been implicated in signaling pathways. The DEGs identified from down-regulated clones included: AK291099 (D7, BST2), NM_001025159.1 (D10, CD74), BC004186 (D18, GNB1), NG_011554 (D34, HTRA1), BC095490 (D36, IGKC), and BC001693 (D41, LGALS1). The down-regulation of HTRA1 was associated with ovarian cancer metastasis [12]. The genes including BST2, CD74 and IGKC were associated with the immune system; while GNB1 and LGALS1 were related to the modulation of cell-cell interaction and the G protein coupled receptor protein signaling pathway, respectively.

Confirmation of ACP observation by quantitative real-time PCR and cluster analysis

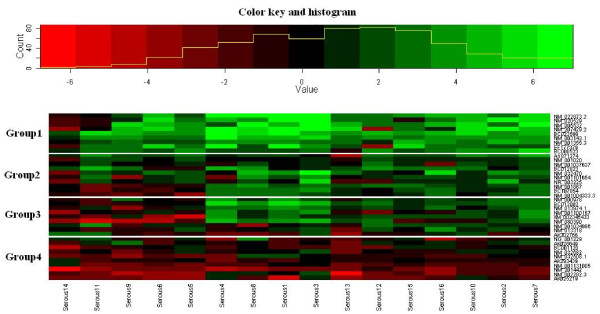

To confirm the efficacy of the ACP system, confirmation of the differential expression of DEGs was performed with quantitative real-time PCR for 38 DEGs selected from the total 114 DEGs using a specific primer pair for each gene (Table 1 and Additional file 1). The expression ratio of the cancer to normal sample was calculated by using CT and then was log2 transformed (see Methods section for detail). The DEGs were considered differentially expressed if the log2 ratio was > 1.0 or < -1.0. Differential expression was clearly observed in all 38 DEGs, which indicates a high reliability of the ACP system (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Clustering of the log2 expression ratios of the cancer to normal samples measured by the quantitative real-time PCR for the 38 DEGs from the 16 patients and its representation as a heat map. Patients are ordered along the X-axis and genes along the Y-axis.

For the detection of more conserved expression patterns in patients with stage III serous ovarian cancer, cluster analysis was performed using the R package mclust http://www.r-project.org. Thirty eight DEGs were divided into four groups according to their expression profiles with assignment of each gene to a group (Figure 3). A clear contrast in expression patterns was noted between groups 1 and 4. That is, the overall up- and down-regulation in group 1 was 86.8% and 5.6%, respectively; the overall up- and down-regulation in group 4 was 9.3% and 60.3%, respectively, when up-regulation corresponds to log2 ratio > 1 and down-regulation to log2 ratio < -1 (Table 3). This regulation pattern in each group was well maintained at various thresholds used for definition of differential expression. These findings suggest that the genes in groups 1 and 4 might be used as potential markers for prognosis in patients with stage III serous ovarian cancer. The group 1 consisted of: NM_003143.1 (SSBP1), NM_022873.2 (IFI6), NM_001355.3 (DDT), NM_005532 (IFI27), NM_207429.2 (C11orf92), NM_020529 (NFKBIA), NM_032470 (TNXB), EF177379 (NEAT1) and BC02359 (TFG); group 4 was composed of: NM_002292.3 (LAMB2), AK025219, AK293439 (XRCC6), NM_001131005 (MEF2C), AK302766 (RBM5), NM_032682 (FOXP1), NG_001229 (NUDCP2), BC001120 (LGALS3), NM_032508.1 (TMEM185A), and NM_201442 (C1S) (Table 3). All genes except for NEAT1 in group 1 were identified from up-regulated clones while all genes except for NUDCP2 in group 4 were identified from down-regulated clones (Tables 2 and 3). These results were in good agreement with the ACP findings.

Table 3.

Clustering of 38 DEGs according to the expression profiles of 16 patients with serous ovarian cancer; Up-regulation corresponds to log2 ratio > threshold while down-regulation to log2 ratio < minus value of threshold.

| Threshold | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| up-regulated | down-regulated | up-regulated | down-regulated | up-regulated | down-regulated | up-regulated | down-regulated | |

| 0.5 | 88.9% | 6.9% | 68.8% | 15.6% | 63.9% | 22.2% | 19.4% | 68.8% |

| 1.0 | 86.8% | 5.6% | 58.8% | 12.5% | 55.6% | 18.1% | 9.3% | 60.3% |

| 1.5 | 84.0% | 4.2% | 45.6% | 7.5% | 48.6% | 13.2% | 6.3% | 46.3% |

| 2.0 | 77.1% | 3.5% | 31.9% | 6.9% | 41.0% | 11.8% | 3.1% | 33.1% |

| Accession no. (gene symbol) | NM_003143.1 (SSBP1) | AY871274 (RPL11) | NM_001867 (COX7C) BC013003 (ANP32B) | AK302766 (RBM5) NM_032682 (FOXP1) | ||||

| NM_022873.2 (IFI6) | BC000523 (RPS24) | BC013003 (ANP32B) | NM_032682 (FOXP1) | |||||

| NM_001355.3 (DDT) | BC012823 | NM_000978 (RPL23) | NG_001229 (NUDCP2) | |||||

| NM_005532(IFI27) | NM_001101654(CXXC1) | NM_013974.1 (DDAH2) | AK025219 | |||||

| NM_207429.2 (C11orf92) | NM_001034996(RPL14) | XM_002345433 | BC001120 (LGALS3) NM_032508.1 (TMEM185A) | |||||

| NM_020529(NFKBIA) | NM_001037637(BTF3) | BC107854 (ATP6V1F) | ||||||

| NM_032470(TNXB) | NM_001020(RPS16) | NM_001004333.3 (RNASEK) | NM_002292.3 (LAMB2) | |||||

| EF177379 (NEAT1) | NR_003225(LGALS3) | NM_080390(TCEAL2) | AK293439 (XRCC6) | |||||

| BC02359 (TFG) | NM_013318(BAT2L1) AK026649 | NM_001100167(MRVI1) | NM_001131005(MEF2C) NM_201442 (C1S) | |||||

The percentage of up- and down-regulation was calculated for each group.

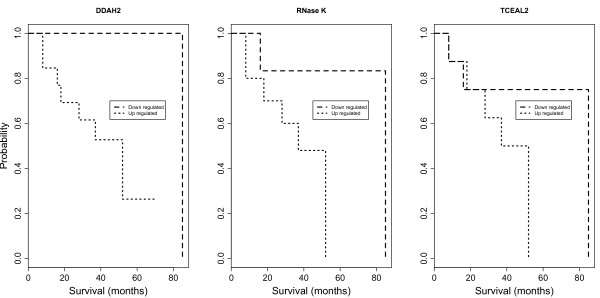

Survival analysis

The Kaplan-Meier method was performed using the 38 DEGs that were up- and down-regulated. The up and down regulated genes were considered according to the log2 expression ratio > 0 and < 0, respectively. A significant difference, in the overall survival (p values < 0.05) between the up- and down-regulated group, was observed for three DEGs including NM_013974.1 (dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 2, DDAH2), NM_001004333.3 (ribonuclease K, RNase K) and NM_080390 (transcription elongation factor A (SII)-like 2, TCEAL2) (Figure 4). The overall survival decreased with up-regulation of these genes. DDAH2 predominates in the vascular endothelium, which is the site of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) expression [13,14]. TCEAL2 is a nuclear phosphoprotein that modulates transcription in a promoter context-dependent manner and has been recognized as an important nuclear target for intracellular signal transduction. The function of RNase K is unknown but might be related to an enhanced degradation of the tumor suppressor gene mRNAs, which leads to the development of cancer. The up-regulation of these three genes was observed in more than 60% of the total number of patients.

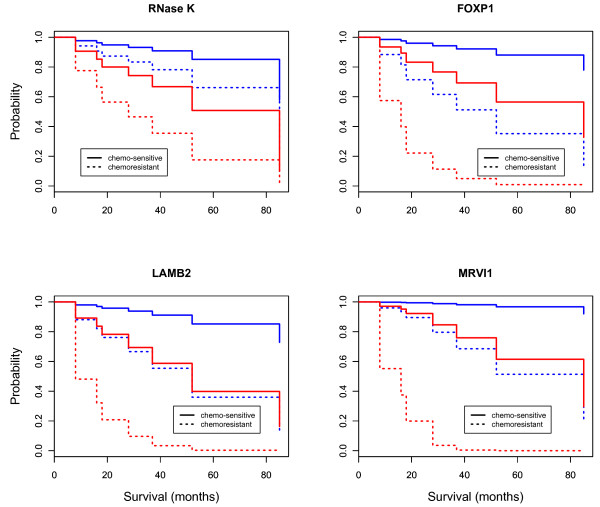

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival stratified by up- and down-regulation for three genes including DDAH2, RNase K and TCEAL2.

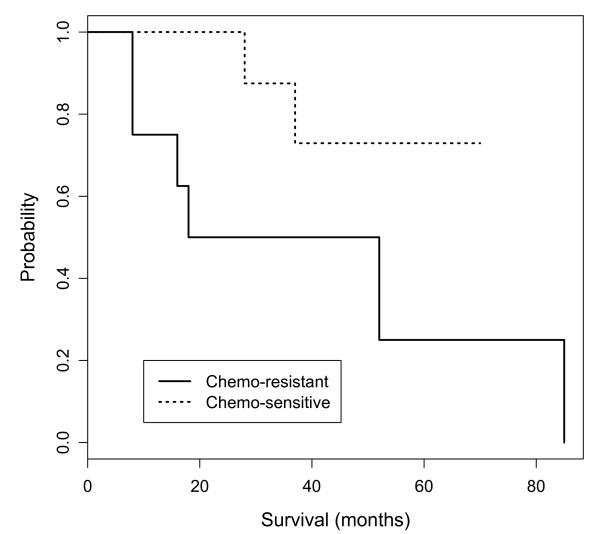

The survival analysis also was performed for chemo-resistance. Following debulking surgery, all patients received platinum-based chemotherapy, considered the standard of care for patients with advanced ovarian cancer. The patients that had either progression during chemotherapy or relapse within six months of treatment were considered chemo-resistant. Among 16 patients, eight were classified as chemo-resistant and the others were categorized as chemo-sensitive. The difference in overall survival between these two groups was significant (p value < 0.05, Figure 5). The shorter survival time of patients with chemo-resistance is consistent with a prior report [15]. To consider chemo-resistance and gene expression simultaneously, in the prediction of overall survival, the Cox multivariate analysis was carried out with the expression information of 38 DEGs and chemo-resistance information from 16 patients. Multivariate analysis demonstrated a significant difference in overall survival between the chemo-resistant and sensitive groups for four DEGs including: NM_001004333.3 (RNase K), NM_032682 (forkhead box transcription factor family, FOXP1), NM_002292.3 (a family of extracellular matrix glycoproteins, LAMB2), and NM_001100167 (murine retrovirus integration site 1 homolog, MRVI1) (p values < 0.05, Figure 6). The RNase K showed significance in both univariate (gene expression) and multivariate (gene expression and chemo-resistance) analysis while DDAH2 and TCEAL2 showed significance only in univariate analysis. This was mainly due to the similar proportion of up- and down-regulation of DDAH2 and TCEAL2 between the chemo-resistant and chemo-sensitive groups. The overall survival of patients with chemo-resistance was significantly decreased with up-regulation of these four genes; while the chemo-sensitive patients had down-regulation of these genes and a good prognosis. FOXP1 has a diverse repertoire of functions ranging from the regulation of B-cell development and monocyte differentiation to the facilitation of cardiac valve and lung development [16,17]. LAMB2 might be involved in the cell adhesion or motility of prostate cancer cells [18]. The down-regulation of FOXP1 and LAMB2 was observed in more than 60% of all patients while MRVI was up-regulated among 63%.

Figure 5.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival stratified by chemo-resistance.

Figure 6.

The overall survival estimated by the Cox proportional hazards multivariate model including gene expression and chemo-resistance. The up- and down-regulation is represented by red and blue, respectively.

Discussion

Ovarian cancer is the most common cause of death among all gynecological malignancies. The five-year survival rates in patients with ovarian cancer are about 80-90% for stage Ia-Ic, 70-80% for stage IIa-IIc, 30-50% for stages IIIa-IIIc and 13% for stage IV [19]. The high rate of death is due to the fact that most of patients (>60%) present with advanced stage disease (FIGO stages III/IV). Despite an initial response rate of 65%-80% to first-line chemotherapy, most ovarian carcinomas relapse. Acquired resistance to further chemotherapy is generally responsible for treatment failure. Several studies have sought to identify gene expression signatures that correlate with clinical outcome to identify those genes that are associated with survival and relapse and to use as predictive biomarkers for response to chemotherapy [20-22].

There are many types of ovarian cancer. EOC accounts for 85%-90%; half of such cases are serous EOC. As with many cancers thought to be of epithelial origin, it is important to establish an appropriate control for evaluating differential gene expression between "normal" and cancer. Expression profiling studies of ovarian cancer have relied on a variety of sources of normal cells or comparison with tumors, including whole ovary samples (WO), ovarian surface epithelium (OSE), exposed to short-term culture, and immortalized OSE cell lines (IOSE) [23]. Direct comparison of the gene expression profiles generated from OSE brushings, WO samples, short-term cultures of normal OSE (NOSE), and telomerase-immortalized OSE (TIOSE) cell lines revealed that these "normal" samples formed robust, but very distinct groups in hierarchical clustering [24]. These indicate that the selection of normal control to compare epithelial ovarian samples in microarray studies can strongly influence the genes that are identified as differentially expressed. In this study, the total RNA from WO (Stratagene, http://www.stratagene.com) was used as control. WO samples have potential to obscure epithelial pattern due to large amounts of stroma, but they offer the advantages of avoidance of exposure to culture conditions and identification of differential gene expression pattern between tumor and normal tissue [25].

A total of 114 DEGs from patients with serous ovarian cancer stage III were identified using the ACP-based GeneFishing™ PCR system, which uses primers that anneal specifically to the template and allows only genuine products to be amplified. As the GeneFishing™ system is based on PCR, it can overcome the difficulty in identifying the genes responsible for a specialized function during a certain biological stage; this is because the gene is expressed at low levels, whereas most mRNA transcripts within a cell are abundantly expressed. Among the 114 DEGs, 42 were identified as up-regulated clones while 72 were down-regulated clones. These DEGs were involved in a variety of biological processes including apoptosis, signal transduction and the immune response. Apoptosis inhibitory processes were associated with genes such as NFKBIA, DDAH2 and IFI6 identified from up-regulated clones; while the immune system associated genes such as IGKC, CD74 and BST2 were found in down-regulated clones. The differential expression of DEGs identified by the Genefishing™ system showed good agreement with the results of the quantitative real-time PCR.

Cluster analysis based on gene expression profiles identified two groups showing a contrast in the expression pattern. That is, one group including: SSBP1, IFI6 DDT, IFI27, C11orf92, NFKBIA, TNXB, NEAT1 and TFG, was up-regulated in most patients with stage III serous ovarian cancer (Figure 3 and Table 3). These genes might be utilized as potential targets in patients with stage III serous ovarian cancer. IFI6 is involved in apoptosis inhibitory activity while TGF is implicated in up regulation of the I-κ B kinase/NF-κ B cascade. TNXB encodes TNX, a protein of unknown function that is mainly expressed in the peripheral nervous system and muscles. The promotion of tumor invasion and metastasis has been reported in mice deficient in TNX through the activation of the matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP2) and MMP9 genes [26]. This indicates that the up-regulation of TNXB, in patients with advanced stage of ovarian cancer, might induce low expression of MMP2 and MMP9. The decrease of MMP2 has been reported in liver metastases in advanced colorectal cancers [27]. Another group consists of LAMB2, XRCC6, MEF2C, RBM5, FOXP1, NUDCP2, LGALS3, TMEM185A, and C1S, which was down-regulated in most patients with stage III serous ovarian cancer (Figure 4 and Table 3). The down-regulation of LAMB2 and MEF2C might be involved with cell adhesion or motility in invasive prostate cancer cells [18] and apoptosis via BCL2 transformation [28], respectively. FOXP1 is a potential therapeutic target in cancer and can be considered either an oncogene and/or a tumor suppressor gene [29]. That is, its over-expression confers a poor prognosis in a number of types of lymphomas while the loss of its expression in breast cancer is associated with a poor outcome. The function of FOXP1 in serous ovarian cancer remains unclear. LGALS3 encoding galectin-3 has been implicated in advanced stage disease [30]. The distribution of galectin has been associated with stage III-V with cellular changes such as dysplasia, cancer cells' nest formation, breakage of the basement membrane, and infiltration of cells into non-native tissue. However, 13 out of the total 16 patients with stage III serous ovarian cancer had down-regulation of LGALS3. This is consistent with the report by van den Brule et al. [31] that showed that galectin-3 expression was decreased in 67% of cases compared to the normal epithelial cells. However, it conflicts with the observations of Lurisci et al. [32] that galectin-3 serum levels in patients with ovarian cancer were significantly elevated. The expression of LGALS3 might be affected by the stage of ovarian cancer.

The overall survival estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method was significantly different between the up- and down-regulated patient cohort with regard to three genes including DDAH2, RNase K and TCEAL2. The up-regulation of these genes was associated with a shorter overall survival (Figure 4). In rapidly growing cells like tumor cells, the activity of RNases is decreased [33], as dictated by the requirement of significant amounts of RNA for protein synthesis. However, high RNase activity has been reported in chronic myeloid leukemia [34] and pancreatic carcinoma [35]. In this study, 70% of the patients with stage III serous ovarian cancer showed up-regulation of RNase K. The function of RNase K in advanced ovarian cancer remains to be clarified. In addition, the overall survival of patients with chemo-resistance was significantly decreased with up-regulation of the genes including: RNase K, FOXP1, LAMB2 and MRVI1 (Figure 6). This might implicate these genes in chemoresistance.

Conclusion

One hundred and fourteen DEGs were identified from 16 patients with stage III serous ovarian carcinoma using the ACP-based RT-PCR technique. Fifteen percent of the total DEGs were associated with apoptosis, the immune response, cell adhesion, and signal pathways. The genes related to apoptosis inhibitory processes tended to be up-regulated while the genes associated with the immune response tended to be down-regulated. The up- and down-regulated genes were identified in most of the patients and might be used as predictive markers in stage III serous ovarian cancer.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

YSK, DHB and WSA designed the study and provided the clinical background. DHB and WSA performed sample annotation and gathered follow-up of the patients. SB performed the experiments. JHD and SB carried out data analysis and JHD wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript and approved it.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Supplementary Material

The log2 expression ratios, of cancer to normal samples measured by the quantitative real-time PCR, for the 38 DEGs from 16 patients.

Contributor Information

Yun-Sook Kim, Email: drsook@schch.co.kr.

Jin Hwan Do, Email: jinhwan.do@gmail.com.

Sumi Bae, Email: ahnlab4@catholic.ac.kr.

Dong-Han Bae, Email: dhbae@schch.co.kr.

Woong Shick Ahn , Email: ahnlab1@catholic.ac.kr.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the National R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry for Health, Welfare and Family affairs, Republic of Korea (0820330).

References

- Chang XH, Zhang L, Yang R, Feng J, Cheng YX, Cheng HY, YE X, Fu TY, Cui H. Screening for genes associated with ovarian cancer prognosis. Chin Med J. 2009;122(10):1167–1172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonome T, Lee JY, Park DC, Radonovich M, Pise-Masison C, Brady J, Gardner GJ, Hao K, Wong WH, Barrett JC, Lu KH, Sood AK, Gershenson DM, Mok SC, Birrer MJ. Expression profiling of serous low malignant potential, low-grade, and high-grade tumors of the ovary. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10602–10612. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh JB, Zarrinkar PP, Sapinoso LM, Kern SG, Behling CA, Monk BJ, Lockhart DJ, Burger RA, Hampton GM. Analysis of gene expression profiles in normal and neoplastic ovarian tissue samples identifies candidate molecular markers of epithelial ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1176–1181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.3.1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz DR, Kardia SL, Shedden KA, Kuick R, Michailidis G, Taylor JM, Misek DE, Wu R, Zhai Y, Darrah DM, Reed H, Ellenson LH, Giordano TJ, Fearon ER, Hanash SM, Cho KR. Gene expression in ovarian cancer reflects both morphology and biological behavior, distinguishing clear cell from other poor-prognosis ovarian carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4722–4729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilks CB, Vanderhyden BC, Zhu S, van de Rijn M, Longacre TA. Distinction between serous tumors of low malignant potential and serous carcinomas based on global mRNA expression profiling. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;96:684–694. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebanov L, Yakovlev A. How high is the level of technical noise in microarray data? Biol Direct. 2007;2:9. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-2-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan JS, Sharp SJ, Poirier GM, Wagaman PC, Chambers J, Pyati J, Hom YL, Galindo JE, Huvar A, Peterson PA, Jackson MR, Erlander MG. Cloning differentially expressed mRNAs. Nat Biotechnol. 1996;14:1685–1691. doi: 10.1038/nbt1296-1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debouck C. Differential display or differential dismay? Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;6:597–599. [Google Scholar]

- Liang P, Pardee AB. Recent advances in differential display. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:274–280. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YJ, Kwak CI, Gu YY, Hwang IT, Chun JY. Annealing control primer system for identification of differentially expressed genes on agarose gels. Biotechniques. 2004;36(3):424–434. doi: 10.2144/04363ST02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott M, McCluggage WG, Hillan KJ, Hall PA, Russell SE. Altered patterns of transcription of the septin gene, SEPT9, in ovarian tumorigenesis. Int J Cancer. 2006;118(5):1325–1329. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Ota T, Liu P, Su C, Chien J, Shridhar V. Downregulation of HtrA1 promotes resistance to anoikis and peritoneal dissemination of ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70(8):3109–3118. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achan V, Tran CT, Arrigoni F, Whitley GS, Leiper JM, Vallance P. All trans retinoic acid increases nitric oxide synthesis by endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2002;90:764–769. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000014450.40853.2B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onozato ML, Tojo A, Leiper J, Fujita T, Palm F, Wilcox CS. Expression of DDAH and PRMT isoforms in the diabetic rat kidney; effects of angiotensin II receptor blocker. Dibetes. 2008;57(1):172–180. doi: 10.2337/db06-1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng WF, Huang CY, Chang MC, Hu YH, Chiang YC, Chen YL, Hsieh CY, Chen CA. High mesothelin correlates with chemoresistance and poor survival in epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(7):1144–1153. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Wang B, Borde M, Nardone J, Maika S, Allred L, Tucker PW, Rao A. Foxp1 is an essential transcriptional regulator of B cell development. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(8):819–826. doi: 10.1038/ni1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi C, Zhang X, Chen Z, Sulaiman K, Feinberg MW, Ballantyne CM, Jain MK, Simon DI. Integrin engagement regulates monocyte differentiation through the forkhead transcription factor Foxp1. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(3):408–418. doi: 10.1172/JCI21100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashida S, Nakagawa H, Katagiri T, Furihata M, Iiizumi M, Anazawa Y, Tsunoda T, Takata R, Kasahara K, Miki T, Fujioka T, Shuin T, Nakamura Y. Molecular features of the transition from prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) to prostate cancer: genome-wide gene-expression profiles of prostate cancers and PINs. Cancer Res. 2004;64(17):5963–5972. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver RI, van Burden M, van't Veer LJ. The role of gene expression profiling in the clinical management of ovarian cancer. Eur J of Cancer. 2006;42:2930–2938. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berchuck A, Iversen ES, Lancaster JM, Pittman J, Luo J, Lee P, Murphy S, Dressman HK, Febbo PG, West M, Nevins JR, Marks JR. Patterns of gene expression that characterize long-term survival in advanced stage serous ovarian cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3686–3696. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helleman J, Jansen MP, Span PN, van Staveren IL, Massuger LF, Meijer-van Gelder ME, Sweep FC, Ewing PC, van der Burg ME, Stoter G, Nooter K, Berns EM. Molecular profiling of platinum resistant ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1963–1971. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dressman HK, Berchuck A, Chan G, Zhai J, Bild A, Sayer R, Cragun J, Clarke J, Whitaker RS, Li L, Gray J, Marks J, Ginsburg GS, Potti A, West M, Nevins JR, Lancaster JM. An integrated genomic-based approach to individualized treatment of patients with advanced-stage ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:517–525. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.3743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley J, Ozbun L, Birrer M. Genomic analysis of epithelial ovarian cancer. Cell Res. 2008;18:538–548. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorn KK, Jazaeri AA, Awtrey CS, Gardner GJ, Mok SC, Boyd J, Birrer MJ. Choice of normal ovarian control influences determination of differentially expressed genes in ovarian cancer expression profiling studies. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:4811–4818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh JB, Zarrinkar PP, Sapinoso LM, Kern SG, Behling CA, Monk BJ, Lockhart DJ, Burger RA, Hampton GM. Analysis of gene expression profiles in normal and neoplastic ovarian tissue samples identifies candidate molecular markers of epithelial ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1176–1181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.3.1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lévy P, Ripoche H, Laurendeau I, Lazar V, Ortonne N, Parfait B, Leroy K, Wechsler J, Salmon I, Wolkenstein P, Dessen P, Vidaud M, Vidaud D, Bièche I. Microarray-based identification of Tenascin C and Tenascin XB, genes possibly involved in tumorigenesis associated with neurofibromatosis type 1. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(2):398–407. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CC, Menges M, Orzechowski HD, Orendain N, Pistorius G, Feifel G, Zeitz M, Stallmach A. Increased matrix metalloproteinase 2 concentration and transcript expression in advanced colorectal carcinomas. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2001;16:133–140. doi: 10.1007/s003840100287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel S, Meyer C, Quentmeier H, Kaufmann M, Drexler HG, MacLeod RA. MEF2C is activated by multiple mechanisms in a subset of T-acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell lines. Leukemia. 2008;22(3):600–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koon HB, Ippolito GC, Banham AH, Tucker PW. FOXP1: a potential therapeutic target in cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2007;11(7):955–965. doi: 10.1517/14728222.11.7.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian K, Vasudevamurthy R, Venkateshaiah SU, Thomas A, Vishweshwara A, Dharmesh SM. Galectin-3 in urine of cancer patients: stage and tissue specificity. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2009;135:355–363. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0481-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Brule FA, Berchuck A, Bast RC, Liu FT, Gillet C, Sobel ME, Castronovo V. Differential expression of the 67-kD laminin receptor and 31-kD human laminin-binding protein in human ovarian carcinomas. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30:1096–1099. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90464-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iurisci I, Tinari N, Natoli C, Angelucci D, Cianchetti E, Iacobelli S. Concentrations of galectin-3 in the sera of normal controls and cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1389–1393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peclet C, de Lamirande G, Daoust R. Sensitivity to RNase treatment of ribosomes and rRNA from normal rat liver and Novikoff hepatoma. Br J cancer. 1982;45:140–143. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1982.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doran G, Allen-Mersh TG, Reynolds KW. Ribonuclease as a tumor marker for pancreatic cancer carcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 1980;33:1212–1213. doi: 10.1136/jcp.33.12.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naskalski JW, Celinski A. Determination of actual activities of acid and alkaline ribonuclease in human serum and urine. Mater med Pol. 1991;23:107–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The log2 expression ratios, of cancer to normal samples measured by the quantitative real-time PCR, for the 38 DEGs from 16 patients.