SUMMARY

CLAVATA1 (CLV1), CLV2, CLV3, CORYNE (CRN), BAM1 and BAM2 are key regulators that function at the shoot apical meristem (SAM) of plants to promote differentiation by limiting the size of the organizing center that maintains stem cell identity in neighboring cells. Previous results have indicated that the extracellular domain of the receptor-kinase CLV1 binds to the CLV3-derived CLE ligand. The biochemical role of receptor-like protein CLV2 has remained largely unknown. While genetic analysis suggested that CLV2, together with the membrane kinase CRN, act in parallel with CLV1, recent studies using transient expression indicated that CLV2 and CRN from a complex with CLV1. Here we report evidence for distinct CLV2/CRN heteromultimeric and CLV1/BAM multimeric complexes in transient expression and in Arabidopsis. Weaker interactions between the two complexes were detectable in transient expression. We also find that CLV2 alone generates a membrane-localized CLE binding activity independent of CLV1. CLV2, CLV1 and the CLV1 homologs BAM1 and BAM2 all bind to the CLV3-derived CLE peptide with similar kinetics, but BAM receptors show a broader range of interactions with different CLE peptides. Finally, we show that BAM and CLV1 over-expression can compensate for the loss of CLV2 function in vivo. These results suggest two parallel ligand-binding receptor complexes controlling stem cell specification in Arabidopsis.

Keywords: CLAVATA2, CLE peptide, CORYNE, CLAVATA1, receptor complex, meristem

INTRODUCTION

In plants, aerial organs are developed from the shoot apical meristem (SAM) (Steeves and Sussex 1989). To continuously generate new organs throughout the life of a plant, a small number of pluripotent stem cells have to be maintained at the center of the SAM. As these stem cells divide, distal and basal progeny cells switch towards differentiation and become competent to form organ primordia. A functional meristem is maintained through a delicate balance between maintenance of stem cells identity and differentiation.

A key pathway regulating Arabidopsis stem cell specification is the CLAVATA (CLV) signaling pathway, which is essential to promote differentiation of lateral stem cell daughters (Clark et al. 1993, Clark et al. 1995, Kayes and Clark 1998). Loss-of-function mutations in any of the CLV genes result in plants with shoot and flower meristems that accumulate massive populations of stem cells. CLV1 and CLV2 encode plasma-membrane receptors, while CLV3 encodes a small secreted proprotein that appears to undergo proteolytic maturation to release a mature CLE peptide (Clark et al. 1997, Jeong et al. 1999, Rojo et al. 2002) (Figure 1b). The CLV1 leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase (LRR-RK) binds to the CLV3 CLE peptide through its extracellular domain, providing direct evidence that CLV3-CLV1 function as a ligand-receptor pair to regulate stem cell specification (Ogawa et al. 2008). The CLV2 gene encodes a receptor-like protein with 21 extracellular LRRs, a single transmembrane domain and a short cytoplasmic tail. Unlike CLV1 and CLV3, which are expressed in very restricted regions in the center of the SAM and function only in stem cell specification (Clarket al. 1997, Fletcher et al. 1999), CLV2 has a much wider expression pattern and is required for the proper development of many organ types (Jeong et al. 1999). The CLV1-related receptors BAM1 and BAM2 act redundantly with CLV1 in the meristem center, but also play a poorly characterized role on the meristem periphery and are broadly functional in many developing organs (DeYoung et al. 2006, DeYoung and Clark 2008). CLV1 and BAM receptors can cross-complement, suggesting a shared mechanism of signaling (DeYoung et al. 2006).

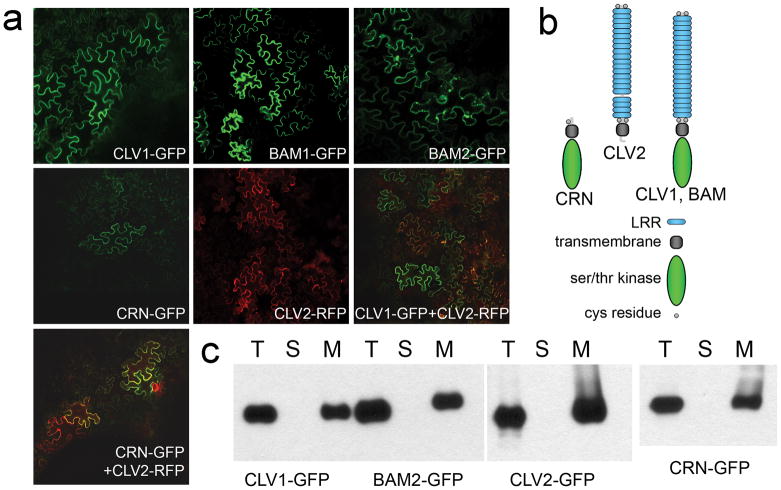

Figure 1. Localization of receptors expressed in N. benthamiana leaves.

(a) Confocal images of fluorescent-tagged receptors two days post-inoculation. Signal was primarily at the cell periphery, although some internal foci, perhaps corresponding to endocytosis, were observed. All infiltrations were done with the addition of the P19 co-suppression inhibitor (Voinnet et al. 2003).

(b) Shown are diagrams of the domain organization of proteins in this study.

(c) Total input (T) for each expressed protein was fractionated into soluble (S) and membrane (M) components and detected by protein gel blot analysis with anti-GFP antibodies.

A prevalent model for CLV signaling suggests that a membrane-bound CLV1/CLV2 co-receptor complex is activated upon CLE binding (Becraft 2002, Clark 2001, Fletcher 2002). While this model is consistent with existing genetic interaction studies, identification of the transmembrane kinase CORYNE (CRN)/SOL2 as a factor in CLV signaling raised questions about this model (Miwa et al. 2008, Muller et al. 2008) (Figure 1b). The epistasis of clv2 to crn led to the model that CLV2, which lacks a cytoplasmic signaling domain, acts with CRN, which lacks an extracellular receptor domain (Muller et al. 2008). Two recent studies reported that when transiently expressed in tobacco leaves (Bleckmann et al. 2010, Zhu et al. 2010) and in Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts (Zhu et al. 2010), CLV2 interacted with CRN, providing evidence for this model. Both of these studies also suggested that the CLV2-CRN heterodimer formed a complex with CLV1 (Bleckmann et al. 2010, Zhu et al. 2010), and one study reported CLV1-CRN interaction (Zhu et al. 2010), suggesting a possibility of CLV1, CLV2 and CRN function together in one large receptor complex.

To address the mechanism of receptor activation and the function of CLV2, we independently tested and quantified receptor associations in transient expression and in Arabidopsis. We also tested the ability of each receptor component to interact with the CLV3-derived CLE signal. Our findings lead us to propose a distinct model for CLV function in vivo.

RESULTS

Expression of the CLV receptors

To study the biochemical functions of the CLV pathway receptors, we generated a variety of transgenes driving expression of each receptor protein with a combination of GFP, FLAG and MYC epitope tags using their native promoter and/or the 35S cis elements. These transgenes were used both in transient expression of receptor proteins in Nicotiana benthamiana and in stable transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. We have shown either in previous studies (DeYoung et al. 2006, Diévart et al. 2003) or here (Supplemental Figure 1) that each of these chimeric proteins can replace the endogenous protein in vivo.

When GFP- or RFP-tagged proteins were expressed in N. benthamiana leaves, all of the receptor proteins, including CLV1-GFP, CLV2-RFP, BAM1-GFP, BAM2-GFP, and CRN-GFP, showed accumulation in the membrane fraction, and showed fluorescence primarily at the cell periphery in a significant portion of cells by two days post-inoculation (DPI) (Figure 1a, 1c). To avoid any artifacts caused by long-term receptor accumulation that might occur at later time points, all assays used membrane fractions at 2 DPI. Co-infiltration of GFP- and RFP-fluorescent proteins revealed incomplete overlap in expression (Figure 1a). When co-expressed with GFP tag-proteins, CLV2-RFP showed co-localization with CLV1 and CRN (Figure 1a).

Evidence for two separate receptor complexes

Based on genetic data, it has been hypothesized that CLV2 and CRN act in parallel with CLV1 to perceive the CLV3 signal (Muller et al. 2008). Using firefly luciferase complementation imaging (LCI) assays (Zhu et al. 2010), and efficiency of fluorescence resonance energy transfer (EFRET) assays (Bleckmann et al. 2010), two recent studies reported CLV2-CRN interaction (Bleckmann et al. 2010, Zhu et al. 2010) and CLV1 homomultimerization (Bleckmann et al. 2010) in transient expression systems, supporting the genetic model. Both of these studies indicated the presence of a CLV1-CRN-CLV2 complex (Bleckmann et al. 2010, Zhu et al. 2010), raising the question of whether CLV1 and CLV2/CRN act as separate interacting complexes or as a single larger complex. One complication of both luciferase complementation and EFRET is that the results can be strongly affected by the particular orientation of the fluorescent tags and expression level of proteins, making quantification of interactions difficult. We have addressed this issue through co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) analysis of various receptor proteins co-expressed in tobacco leaves and in vivo.

We first tested interactions among the related receptor-kinases CLV1, BAM1 and BAM2. We observed robust co-IP between CLV1-CLV1, CLV1-BAM1, CLV1-BAM2, BAM1-BAM1, and BAM1-BAM2 (Figure 2a, 2b, 3a, Supplemental Figure 2). Interestingly, none of the clv1 dominant-negative missense mutant isoforms tested had any detectable effect on clv1-CLV1 or clv1-BAM1 co-IP (Figure 2a, 2b). To quantify the extent and stability of these receptor-kinase interactions, we analyzed the efficiency of co-IP between CLV1-GFP and BAM2-FLAG (Figure 3a). We compared bound and unbound fractions from CLV1-GFP and BAM2-FLAG co-expression precipitated with anti-GFP antibodies. We estimate an efficiency of interaction of 20% (based on 10% co-IP of BAM2-FLAG in an experiment with 50% IP of CLV1-GFP (Figure 3a); see Experimental Procedures). The CLV1-BAM2 complex appears to involve nearly all of the available CLV1 (given the possibility of CLV1 homodimerization and incomplete overlap in expression) and is quite stable.

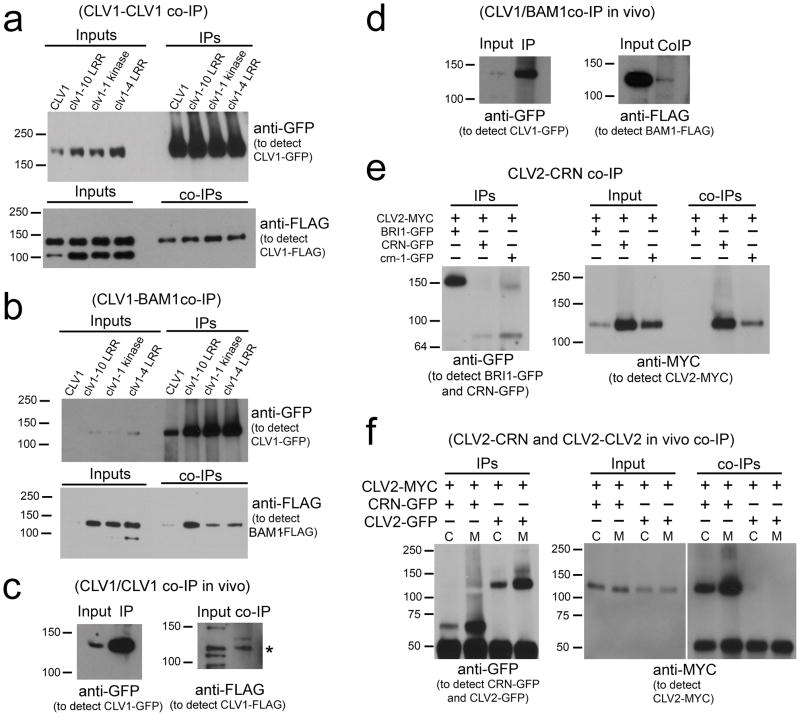

Figure 2. Detection of receptor interactions.

(a) Solubilized membrane extracts from CLV1-FLAG co-expressed with wild-type and mutant versions of CLV1-GFP in transient expression were immunoprecipitated (IPd) with anti-GFP antibodies and co-IPs were detected with anti-FLAG antibodies. Note, the anti-FLAG antibody can detect a non-specific band of ~100 kD in input samples.

(b) Wild-type and mutant versions of CLV1-GFP co-expressed with BAM1-FLAG in transient expression were IPd with anti-GFP antibodies and co-IPs were detected with anti-FLAG antibodies.

(c) Solubilized membrane extracts from Arabidopsis plants co-expressing CLV1-GFP and CLV1-FLAG were IPd with anti-GFP antibodies and co-IPs were detected with anti-FLAG antibodies.

(d) Solubilized membrane extracts from Arabidopsis plants co-expressing CLV1-GFP and BAM1-FLAG were IPd with anti-GFP antibodies and co-IPs were detected with anti-FLAG antibodies.

(e) CLV2-MYC co-expressed with BRI1-GFP, CRN-GFP or crn-1-GFP in transient expression were IPd with anti-GFP antibodies and co-IPs were detected with anti-MYC antibodies.

(f) Both crude extracts (C) and solubilized membrane extracts (M) were used to perform IPs using anti-GFP antibodies from Arabidopsis plants co-expressing CRN-GFP and CLV2-MYC or CLV2-MYC and CLV2-GFP. co-IPs were detected with anti-MYC antibodies. The cross-reacting signal below the 50 kD marker was from IgG proteins.

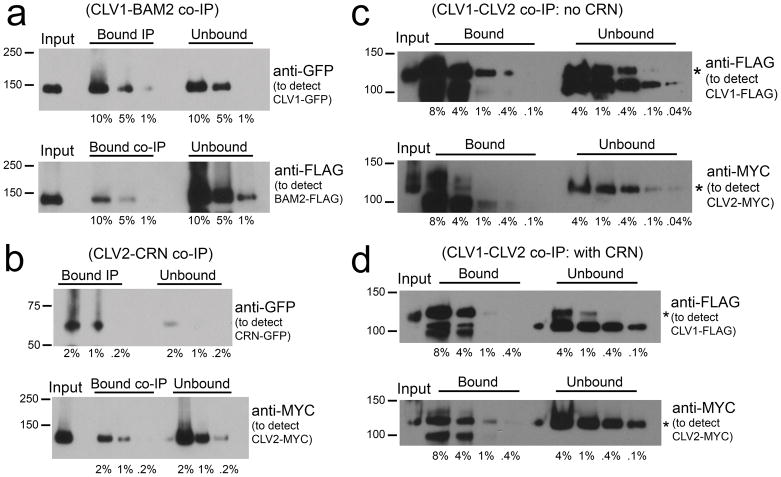

Figure 3. Quantification of receptor interactions.

(a) Solubilized membrane extracts from CLV1-GFP co-expressed with BAM2-FLAG in transient expression were IPd with anti-GFP antibodies and co-IPs were detected with anti-FLAG antibodies. A dilution series of 10%, 5% and 1% of total bound and unbound fractions were assayed on protein gel blots to estimate the efficiency of IP and co-IP (see Experimental Procedures).

(b) CRN-GFP co-expressed with CLV2-MYC in transient expression was IPd with anti-GFP antibodies and co-IPs were detected with anti-MYC antibodies. A dilution series of 2%, 1% and 0.2% of total bound and unbound fractions were assayed on protein gel blots to estimate the efficiency of IP and co-IP.

(c) CLV1-FLAG co-expressed with CLV2-MYC in transient expression was IPd with anti-FLAG antibodies and co-IPs were detected with anti-MYC antibodies. A dilution series of 8%, 4%, 1%, 0.4% and 0.1% of total bound, and a dilution series of 4%, 1%, 0.4%, 0.1%, and 0.04% of unbound fractions were assayed on protein gel blots to estimate the efficiency of IP and co-IP.

(d) CLV1-FLAG co-expressed with CLV2-MYC and CRN-GFP in transient expression was IPd with anti-FLAG antibodies and co-IPs were detected with anti-MYC. A dilution series of 8%, 4%, 1% and 0.4% of total bound, and a dilution series of 4%, 1%, 0.4% and 0.1% of unbound fractions were assayed on protein gel blots to estimate the efficiency of IP and co-IP.

Controls to test for non-specific antibody interaction, non-specific tag/receptor interactions, and interactions that might occur post-isolation during the immunoprecipitation procedure all showed that the interactions are specific and require receptor co-expression (Supplemental Figure 2, 3, Figure 2e).

To examine if the CLV1/CLV1 interactions observed in transient expression represented endogenous interactions, we tested co-IP between CLV1-GFP and CLV1-FLAG in Arabidopsis meristem tissue. Despite the poor accumulation of CLV1 in transgenic Arabidopsis (DeYoung et al. 2006), we could readily detect interaction (Figure 2c). We also detected the interaction between CLV1-GFP and BAM1-FLAG in stably transformed Arabidopsis (Figure 2d).

In transient expression we observed robust co-IP between CLV2-MYC and CRN-GFP (Figure 2e), with approximately 20% of the CLV2-MYC co-IPd by anti-GFP antibodies (Figure 3b). Thus, the CLV2-CRN complex must also be relatively abundant and stable. Control experiments demonstrated that the interactions were specific and dependent on co-expression ((Figure 2e, Supplemental Figure 3).

Transgenic Arabidopsis plants stably expressing CLV2-MYC and CRN-GFP were used to assess interactions in vivo. Here we also observed robust co-IP between the two proteins (Figure 2f), indicating this is a physiologically relevant complex. No homomultimerization of CLV2 was observed in vivo (Figure 2f). When crn-1 was co-expressed with CLV2 in transient expression and tested for co-immunoprecipitation, we found the mutation did not eliminate the CLV2/CRN interaction (Figure 2e). Nor did the crn-1 mutation affect CRN-FLAG/CRN-GFP interactions when transiently expressed (Supplemental Figure 4a) Given that crn-1 is a dominant-negative allele, it may act by sequestering CLV2 in a non-functional manner.

We also tested interactions between receptor protein pairs CLV1/CLV2, BAM1/CLV2, BAM2/CLV2 and CLV1/CRN and were able to detect co-IP between each combination (Supplemental Figure 4b, 4c). However, based on the co-IP signal, all of these interactions were much weaker than the ones observed between CLV2 and CRN and between CLV1 and CLV1/BAM. In quantifying the interactions between CLV1/CLV2 using the same approach that was used to quantify CLV1-BAM and CLV2-CRN, the interactions were nearly an order of magnitude lower around 3% (2.5% co-IP of 75% IPd protein) (Figure 3c). When all three proteins, CLV1, CLV2 and CRN were co-expressed, the level of CLV1-CLV2 interaction was a similarly low around 5% (2.5% co-IP of 50% IPd protein) (Figure 3d). Perhaps related to the weak interaction between BAM1 and CLV2 in transient expression, repeated attempts to detect co-IP between BAM1 and CLV2 in Arabidopsis have been unsuccessful (B. DeYoung, L. Han and S.E. Clark, unpublished).

A CLV2 CLE-binding activity similar to that of CLV1

If CLV1 and CLV2/CRN form distinct receptor complexes, what is the role of the CLV2-CRN complex? BRI1 signaling is relayed through BSKs, which are membrane-associated cytoplasmic kinases (Tang et al. 2008). Thus, one hypothesis would be that CLV2/CRN function analogously to BSKs by relaying the signal from the ligand-binding receptor (in this case CLV1). However, CLV2/CRN together differ from BSKs in that CLV2 contains an extensive extracellular domain. What then is the role of the CLV2 extracellular LRR domain? Genetic evidence has suggested that the CLE domain processed from CLV3 is the ligand for the receptor-kinase CLV1 (Fiers et al. 2005, Fiers et al. 2004, Fletcher et al. 1999, Lenhard and Laux 2003, Ni and Clark 2006, Trotochaud et al. 1999). Recent reports showed that CLV3 CLE peptides bind to the truncated CLV1 LRR domain expressed in tobacco BY-2 cells, confirming an interaction between this ligand-receptor pair (Ogawa et al. 2008). To address the function of the LRR domains of the various receptors, we have tested ligand binding activities of the CLV pathway receptors via radioiodination of the CLV3 CLE peptide (Mayers and Klostergaard 1983). In this process, the two histidine resdiues in the CLE domain are targeted for 125I labeling, followed by HPLC purification of labeled, active peptides.

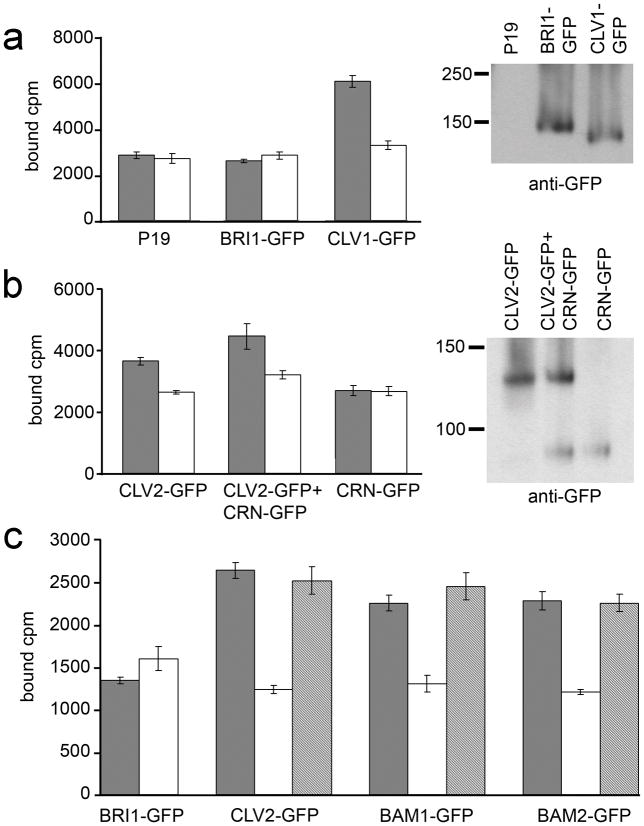

We found that expression of full-length CLV1 in N. benthamiana generated specific binding for 125I-radiolabeled CLV3 CLE peptides to membrane fractions (Figure 4a). CLV3 CLE-binding activity was also generated by expressing the CLV1-related BAM1 and BAM2 receptors (Figure 4c). Critically, CLV3 CLE-binding sites within membrane fractions were generated by expression of full-length CLV2 (Figure 4b). This suggests that CLV1 and CLV2 perceive the same CLV3 CLE ligand signal in controlling stem cell homeostasis. Although CRN acts with CLV2 as a separate receptor complex, as indicated by co-IP analyses, the observed CLV2 ligand-binding activity was not dependent on the co-expression of CRN, nor did CRN expression alone lead to CLV3 CLE binding (Figure 4b). Membrane fractions from N. benthamiana leaves in which no receptor protein was expressed or samples in which the brassinosteroid receptor BRI1 was expressed served as negative controls and showed no specific binding to radiolabeled CLV3 CLE (Figure 4a).

Figure 4. CLV3 CLE binding activity.

(a) Detergent-washed membrane fractions from P19, BRI1-GFP and CLV1-GFP inoculations were tested for 125I-labelled CLV3 CLE peptide binding without (black bars) and with (white bars) excess unlabelled CLV3 CLE competitor. Mean ± standard error over four replicates are shown. The fractions tested for CLE binding were assayed in a protein gel blot with anti-GFP antibodies to detect BRI1-GFP and CLV1-GFP accumulation.

(b) Assays identical to those in (a) performed for CLV2-GFP and CRN-GFP in independent and co-inoculations.

(c) GFP-fused CLV2, BRI1, BAM1 and BAM2 were immunoprecipitated with anti-GFP antibodies and then tested for CLV3 CLE binding activity without (black bars) and with excess unlabelled CLV3 CLE (white bars) or the non-functional CLV3S peptide (grey bars) as competitors. Mean ± standard error over three replicates are shown.

We next tested immunopurified CLV2, BRI1, BAM1 and BAM2 for CLV3 CLE binding activity (Figure 4c). Specific binding was observed from immunoprecipitated CLV2, BAM1 and BAM2, but not from BRI1. As a further control, the non-functional CLV3S peptide was also used as a cold competitor to radiolabeled CLV3 CLE, and, as previously reported for CLV1, was unable to compete (Kondo et al. 2008, Ogawa et al. 2008) (Figure 4c).

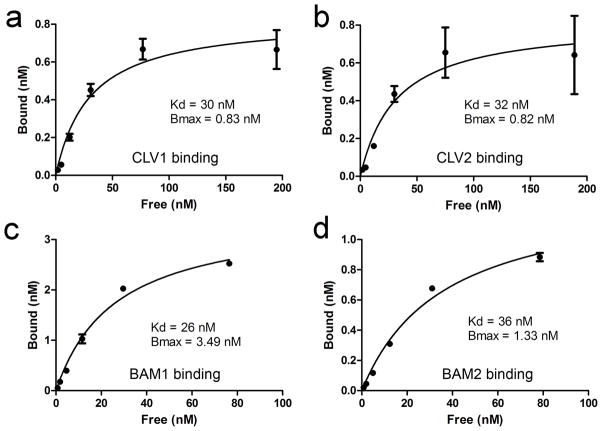

To compare the CLV3 CLE binding affinities of CLV1 and CLV2, we assayed the binding kinetics (Figure 5). Binding was saturable for all receptors with a very similar Kd for each receptor: 30 nM for CLV1, 32 nM for CLV2, 26 nM for BAM1, and 36 nM for BAM2 (Figure 5, Supplemental Figure 5). Thus, CLV1 and CLV2 binding activities have very similar affinities for the same CLV3 CLE peptide, suggesting that they each perceive the CLV3 signal in vivo in a similar manner. Interestingly, clv2 mutants are resistant to CLE peptide treatment in seedlings, both at the root and shoot meristem (Fiers et al. 2005). This had been hypothesized to be the result of the requirement for CLV2 for the function of unknown receptor-kinases, but our results suggest that this resistance is a result of the loss of the CLV2 CLE-binding activity in the clv2 mutant.

Figure 5. Kinetics of CLV3 CLE binding.

Saturation curves for CLV3 CLE binding from detergent-washed membrane fractions expressing CLV1-GFP (a), CLV2-MYC (b), BAM1-GFP (c), and BAM2-GFP (d) are shown. The mean ± standard error over three replicates are shown, as are the equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) and total binding (Bmax).

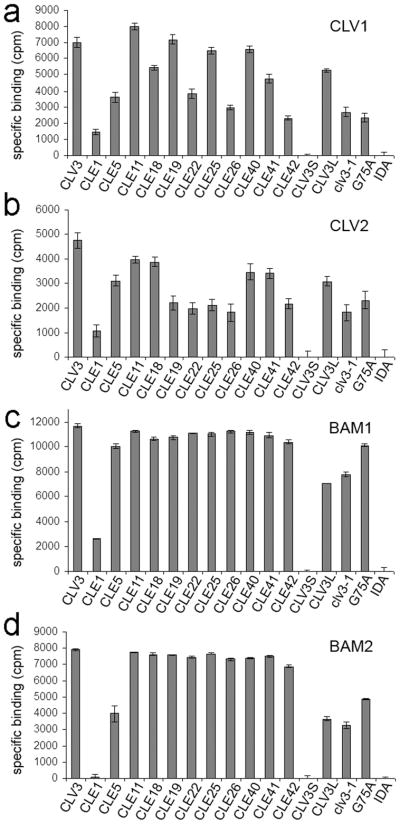

There are a large number of CLE-containing proteins that can differ significantly in their CLE domain sequences (Cock and McCormick 2001, DeYoung and Clark 2001, Oelkers et al. 2008). We have shown previously that the different CLE-containing proteins can differ dramatically in their ability to replace CLV3 function in vivo (Ni and Clark 2006). In addition, the different CLE-containing proteins can drive divergent over-expression phenotypes (Strabala et al. 2006). These studies suggest that the different CLE peptides differ in receptor specificity. Indeed, other CLE peptides have been shown to bind to different receptors (Hirakawa et al. 2008). To determine if CLV1 and CLV2 exhibited differential specificity to individual CLEs, we tested a variety of CLE peptides. These included CLE1, CLE5, CLE11, CLE18, CLE19, CLE22, CLE25, CLE26, CLE40, CLE41 and CLE42. Other peptides included for comparison included: CLV3S (Thr71-His81) which only contains a portion of the CLE domain and is nonfunctional; CLV3L (Arg70-Pro96) which includes the full CLV3 CLE domain plus the extended C-terminal tail and is partially functional; the clv3-1 mutant CLE isoform (Gly75Arg); the clv3-G75A (Gly75Ala) mutant isoform; and another proline-rich putative peptide ligand IDA (Pro278-Asn289) as a negative control (Stenvik et al. 2006, Stenvik et al. 2008). It should be noted that the original annotation for the clv3-1 mutation and the subsequent interpretation of clv3-1 as a glycine to alanine substitution at residue 75 was inaccurate. We sequenced clv3-1 and determined the GGA codon for glycine75 is mutated to AGA, leading to a glycine to arginine substitution.

When the various CLE peptides were used as cold competitors for radiolabeled CLV3 CLE binding to CLV1, CLV2, BAM1 and BAM2 (Figure 6). CLE peptides that bind effectively to the receptors should compete off the radiolabeled CLV3 CLE peptide, while those with no or reduced binding should be unable to fully displace the bound radiolabeled CLV3 CLE peptide. Figure 6 presents the amount of bound radiolabeled CLV3 displaced by the various cold CLE competitors.

Figure 6. Receptor specificity for different CLEs.

Specific binding in counts per minute (cpm) (total binding minus binding activity with competitor peptides) of different CLE peptides by detergent-washed membrane fractions expressing CLV1-GFP (a), CLV2-MYC (b), BAM1-GFP (c), and BAM2-GFP (d) are shown. See text for description of peptides. The mean ± standard error over three replicates are shown.

For CLV1 and CLV2, we observed a wide variation in the extent of competition (Figure 6). Several CLE peptides were unable to effectively compete with CLV3 CLE, suggesting that they bind poorly to CLV1 and CLV2. Interestingly, CLV1 and CLV2 displayed similar binding affinities for a number of CLEs, including CLE1, CLE5, CLE18, CLE22, CLE26, CLE41 and CLE42 (Figure 6a, 6b). clv3-1 exhibited poor binding to both CLV1 and CLV2, consistent with the partial-loss-of-function for the clv3-1 allele (Clark et al. 1995). Differences were observed, however, and these generally were CLEs that retained good competition for CLV1, but reduced competition for CLV2, including CLE11, CLE19 and CLE25.

A very different result was obtained with binding to BAM1 and BAM2 (Figure 6c, 6d). When 10 μM of cold peptide was used, nearly every CLE provided full competition to CLV3 CLE binding, with the exception of CLE1 and CLE5. Even the mutant clv3-1 peptide was largely functional in replacing CLV3 CLE binding to BAM1. This suggests that BAM receptors have a wider range of specificity for CLE binding than either CLV1 or CLV2, perhaps related to their broad developmental roles.

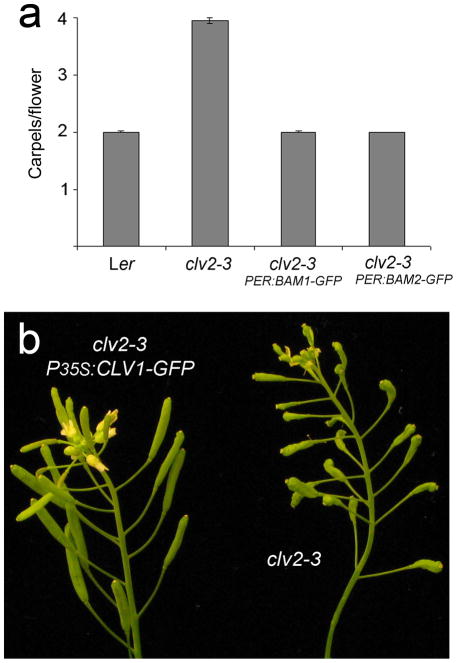

BAM and CLV1 can replace CLV2 function in vivo

If CLV1/BAM and CLV2/CRN form distinct complexes in vivo (as opposed to a single larger complex), it might be possible to bypass the requirement for one of the complexes through over-expression of the other. To this end, we crossed the receptor over-expression constructs P35S:CLV1-GFP, PER:BAM1-GFP and PER:BAM2-GFP to clv2 mutants. We observed that both the BAM1 and BAM2 receptors could provide a complete rescue of the clv2 mutant phenotype (Figure 7a). The effect of CLV1 over-expression on clv2 was weaker, with only a barely significant change in carpel number, but a clear reduction in valvelessness and gynoecia defects (Figure 7b). 65% of clv2–3 flowers exhibited valvelessness (n=60) (Kayes and Clark, 1998), while none of the flowers of the P35S:CLV1-GFP clv2–3 plants displayed valvelessness (n=60). Thus, exogenous BAM1 and BAM2 can completely, and CLV1 can partially bypass the function of CLV2 in meristem development.

Figure 7. Ectopic BAM1, BAM2 and CLV1 can replace CLV2 function in vivo.

(a) The mean number of carpels per flower from wild-type Ler (n=70), clv2–3 (n=90), PER:BAM1-GFP clv2–3 (n=90) and PER:BAM2-GFP clv2–3 (n=90) plants.

(b) Inflorescences from clv2–3 and P35S:CLV1-GFP clv2–3 plants. Note the distortion in clv2–3 gynoecia shape due to fifth whorl growth and valvelessness (Kayes and Clark, 1998) are reduced by the P35S:CLV1-GFP transgene.

DISCUSSION

In this study we find evidence for two distinct receptor complexes involved in stem cell regulation in Arabidopsis, CLV2/CRN and CLV1/BAM. Both CLV1 and CLV2 bind the CLV3-derived CLE ligand. The presence of two ligand-binding complexes suggests a unique mode of receptor activation of the CLV pathway.

The biochemical function of CLV2 has remained unknown. While originally viewed as a co-receptor for CLV1, two recent studies relying on fluorescent-based association assays have suggested that CLV2 forms a complex with CRN (Bleckmann et al. 2010, Zhu et al. 2010). Our results here have not only extended on these findings, but also noted significant differences. First, we have tested aspects of recent studies, which were based on co-fluorescence, with direct co-immunoprecipitation of proteins with entirely different epitope tags. In doing so, we have directly quantified the amount of associated receptor proteins in each complex. Furthermore, we have tested the formation of each complex in vivo in Arabidopsis. Finally, we have assayed the ability of each receptor protein to bind to the peptide ligand derived from CLV3.

Consistent with previous reports, we observed the formation of the CLV2/CRN complex, and our quantification and in vivo analyses indicate that this complex is both robust and of in vivo significance. The presence of a robust CLV1/CLV1 complex in transient expression and in vivo in this study confirms data from fluorescent assays in transient N. bethamiana expression (Bleckmann et al. 2010), but is inconsistent with earlier results from fluorescent assays in protoplasts (Zhu et al. 2010). .

Furthermore, we have found BAM receptors have similar complex affinity for CLV1 as CLV1 itself does. CLV1/CLV1 and CLV1/BAM multimers and the insensitivity of the CLV1/CLV1 interaction to clv1 missense mutations in both the LRR and kinase domains are consistent with genetic analyses: clv1 strong alleles are all dominant-negative and act in part by interfering with BAM function in the meristem center (DeYoung et al. 2006, DeYoung and Clark 2008).

Similarly, the dominant-negative crn-1 isoform also retained the ability to interact with CLV2. In both of these cases, the dominant-negative isoforms interact with their partner proteins, which presumably poisons the function of the receptor complex in vivo.

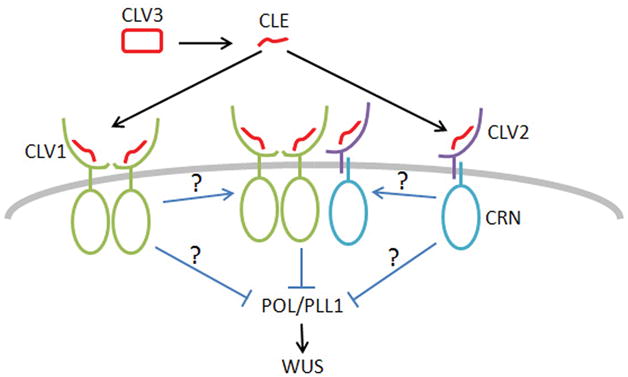

What then is the relationship between the CLV1/CLV1 and CLV2/CRN complexes? The ability of CLV2 to independently bind CLE indicates that CLV2/CRN does not function analogously to the BSK proteins that relay BRI1 signaling (Tang et al. 2008). One might speculate that each complex is activated by CLE binding and the two complexes then come together to form a larger signaling assembly. The formation of a CLV1-CRN-CLV2 complex in transient expression, as indicated by two recent studies (Bleckmann et al. 2010, Zhu et al. 2010), as well as the weaker interaction between CLV1/BAM and CLV2/CRN that we show in this study, might reflect such a higher ordered complex (Figure 8). Alternatively, each complex may control the activity of a common, or even different, effector protein(s). The ability of BAM over-expression to bypass the clv2 mutation supports a model in which the two complex act on common intermediates. Genetic analysis indicates that CLV1 and CLV2 signaling converge to repress the activity of the phosphatases POL and PLL1 (Song et al. 2006) (Figure 8). Whether POL/PLL1 repression is the function of the two complexes independently, or whether it is the function of a larger CLV1/CLV2/CRN complex is unclear. Identification of the factors directly interacting with the CLV1 and CRN kinase domains is a critical next step in further understanding the mechanism of receptor activation.

Figure 8. A model for CLV signaling.

CLV3 is proteolytically processed to a CLE signaling peptide. The CLV3 CLE peptide binds to both a CLV1 homodimer as well as a CLV2-CRN complex. The two activated receptor complexes either interact with each other or signaling independently to repress POL/PLL1 activity.

Several other receptor systems also involve multiple receptor complexes. TGFβ signaling, for example, features two receptor complexes, each a homodimer (Gilboa et al. 1998, Heldin et al. 1997). The type II dimer binds the ligand TGFβ and then interacts with a type I dimer to facilitate transphosphorylation and signaling. Wnt signaling involves two different receptors, LRP and Frizzled, that appear to bind to a single ligand simultaneously (Cadigan and Liu 2006, Cong et al. 2004). Our results indicating separate CLV3 CLE binding activity for CLV1 and CLV2 suggest that CLV signaling is distinct from both of these models. That is, two separable receptors complexes bind independently to the same ligand.

We measured the specificity of the CLV1, BAM1, BAM2 and CLV2 binding activity for different CLE peptides by measuring their ability to compete with radiolabeled CLV3 CLE binding. Interestingly, the CLV1 and CLV2 binding specificities behaved in a similar manner, with different CLEs showing a range of competition from complete to negligible. Furthermore, effective competitors for the CLV1 binding activity were generally effective competitors for the CLV2 binding activity, while poor competitors for CLV1 were generally poor competitors for CLV2. This similarity suggests that the two binding activities have similar binding pockets, with a related CLE specificity. The BAM1 and BAM2 receptors, on the other hand, exhibited a very different result in that nearly all of the CLE peptides tested were full competitors for the radiolabeled CLV3 CLE. This suggests that BAM1 and BAM2 have a broader range of CLE binding specificity. This may be explained by the broad expression and function of BAM receptors throughout plant development where they regulate leaf, stem, vascular, floral organ and gamete developmental patterning (DeYoung et al. 2006, Hord et al. 2006). On the other hand, the more limited role of CLV1 and CLV2 in the meristem explains their more restrictive pattern of CLE binding.

For many of the CLE peptides, their CLV1 and CLV2 binding activity correlated well with their function in vivo. For example, the non-functional CLV3S peptide showed no binding, the partial-loss-of-function clv3-1 peptide showed reduced binding, and the root meristem regulator CLE40 (Stahl et al. 2009) showed strong competition. The binding activity of several peptides, including CLE1 and CLE25, however, is not consistent with earlier genetic data showing that CLE1 can rescue clv3 mutant (Ni and Clark 2006) and can cause wus-like phenotype when overexpressed (Strabala et al. 2006), while CLE25 can not (Ni and Clark 2006, Strabala et al. 2006). The CLV1-binding activity of CLE1 and CLE 25 peptides, however, is consistent with earlier results when synthetic peptides were used in treating Arabidopsis plants, in which the CLE25 peptide, among others, caused reduced size of the SAM while CLE1 did not (Kinoshita et al. 2007). By using nano LC-MS/MS analysis of the apoplastic peptides of transgenic Arabidopsis, a recent study showed that the mature form of several CLE peptides, including CLV3, were glycosylated and the glysosylation affected receptor binding (Ohyama et al. 2009). Posttranslational modifications have been observed in several other peptide ligands in plants (Matsubayashi et al. 2006). The inconsistency between our binding results and genetic data suggests that several of the CLE peptide ligands require posttranslational modification for their function in vivo.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Co-immunoprecipitation assays and protein gel blot analysis

Transient co-expressions of proteins in Nicotiana benthamiana (Kim et al. 2007) and Arabidopsis transformation (Clough and Bent 1998) were performed as described. For all membrane protein extractions, leaf discs were harvested two days post-infiltration by grinding in cold extraction buffer without triton (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 10 mM NaF, 10 mM NaVO3, 2% plant specific protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma), 10 ug/ml chymostatin and 2 ug/ml aprotinin). The homogenates were centrifuged at 3,300 g at 4°C for 10 minutes. Supernatants were harvested and subjected to ultracentrifugation at 100,000 g for 1 hour at 4°C. The microsome membrane pellets were resuspended in extraction buffer supplemented with 1% triton X-100 and solubilization was conducted at 4°C with gentle agitation for 30 minutes. The crude membrane homogenates were centrifuged at 100,000 g for 1 hour at 4°C and the supernatants (solubilized membrane extracts) were recovered.

For all co-immunoprecipitation assays using GFP antibodies, solubilized membrane extracts were incubated with antibodies (see below) at 4°C for 2 hours and subsequently equilibrated protein A agarose (Invitrogen) was added to protein-antibody mixture for an additional 2 hours. For co-IP with FLAG antibodies, solubilized membrane extracts were incubated overnight with Anti-FLAG M2-Agarose (Sigma). The beads were washed three times with wash buffer and protein complexes were eluted from beads with 1x SDS loading buffer.

Eluted proteins were resolved on 4–15% gradient SDS-PAGE gel and blotted onto PVDF membrane by tank immunoblotting. For all western blot analyses the blotted membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk prepared in 1x TBST buffer at room temperature for 1 hour. Primary antibody incubations were conducted at 4°C overnight while secondary antibody incubation occurred at room temperature for 1 hour. Following primary and secondary antibody incubation, membranes were washed 10 minutes with 1x TBST (0.05% Tween) for three times. Supplemental Table 1 lists all antibodies used to detect the fusion proteins. The membranes were developed using enhanced chemiluminescence SuperSignal West Pico Substrates (Pierce Biotechnology) or Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrates (Millipore).

Arabidopsis protein extracts were collected from inflorescence meristem tissue, focusing on the shoot and flower meristems and young developing flowers. Tissue samples were processed in a manner identical to that for samples from N. benthamiana leaves as described above.

Quantifying co-immunoprecipitation efficiency

To quantify the efficiency of co-immunoprecipitation, both the bound and unbound fractions in the first immunoprecipitation pull-down were collected. Dilutions series of each of the bound and unbound samples were then run simultaneously on duplicate protein gel blots. Blots were probed separately with antibodies to detect the immunoprecipitated protein (to test the efficiency of IP) and the co- immunoprecipitated protein (to test the efficiency of co-IP). The co-IP efficiency was then estimated by determining the portion of protein in the co-IP bound fraction versus unbound fraction. In the case of CLV1-BAM2 interactions, for example, this estimate was adjusted to account for the fact that only 50% of the CLV1 protein was originally immunoprecipitated.

Expression constructs

For CLV1-FLAG protein expression, a CLV1-FLAG fragment was obtained from the previously described PER:CLV1-FLAG (DeYoung et al. 2006) by digestion with Bam HI and Sal I and was cloned into the binary vector pCHF1 at the same restriction sites, resulting in an P35S:CLV1-FLAG expression cassette with the pea RBCS-E9 terminator. CLV1 coding sequences were replaced with those from BAM1 and BAM2 using Spe I to generate the P35S:BAM-FLAG constructs.

For CLV1-GFP, BAM1-GFP and BAM2-GFP, an mGFP5 fragment was PCR amplified with engineered Spe I and Sal 1 sites and cloned into the P35S:CLV1-FLAG cassette, replacing the FLAG sequences. BAM1-GFP and BAM2-GFP were generated by replacing the CLV coding sequences in P35S:CLV1-GFP using Spe I. P35S:BRI1-GFP plasmid was a gift from Jianming Li (Hong et al. 2008). To generate PER:BAM1-GFP and PER:BAM2-GFP, BAM1-GFP and BAM2-GFP were put downstream of the ERECTA promoter (Diévart et al. 2003) in the binary vector pGreen0029.

For CLV2-GFP and CRN-GFP, we used the Gateway (Invitrogen) system. The CLV2 and CRN coding sequences were PCR amplified and cloned into pENTR/D-TOPO to generate pCLV2 and pCRN entry vectors. These entry vectors were used in the LR-Gateway reaction with pMDC83 destination vector (Curtis and Grossniklaus 2003) to generate P35S:CLV2-GFP and P35S:CRN-GFP. The GFP-fused crn-1 mutant isoform was generated via site-directed mutagenesis of the P35S:CRN-GFP cassette. P35S:CRN-FLAG was generated by cloning the CRN coding sequence into P35S:BAM2- FLAG to replace the BAM2 sequence at Spe I and Sma I.

clv1 mutant isoforms were generated by PCR-amplification of the coding sequences of different clv mutants. An engineered Spe I and the BrsG I site within the CLV1 sequence were used to clone the LRR mutant isoforms into the CLV1-overexpression vectors in which the 3′ end Spe I was destroyed. For the kinase domain mutations, the Aat II and Sac II sites from the CLV1 sequence were used to clone the mutant kinase domain into the P35S:CLV1-FLAG and P35S:CLV1-GFP cassettes. Note that the clv1–10 allele consists of the original clv1-1 kinase domain allele, plus an LRR domain intragenic enhancer. (Diévart and Clark 2004) For this study, only the LRR domain lesion was introduced for the clv1–10 LRR isoform.

MYC-tagged CLV2 was generated by cloning the CLV2 genomic sequence, including the CLV2 promoter and coding sequence, into a binary vector pPZP221 to fuse with a 5X MYC tag at the C-terminus. RFP-tagged CLV2 was constructed by cloning the CLV2 coding sequence into the vector pSAT6-RFP-N (Tzfira et al. 2005) at Sal I and Bam HI (filled-in) and the 35S cis element-driven CLV2-RFP expression cassette was subsequently cloned into the binary vector pPZP211.

Confocal microscopy

Two days after infiltration, the subcellular localizations of the GFP/RFP fused proteins were examined with a Leica TCS-SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). The abaxial side of tobacco leaves was viewed at 20x magnification. 488 nm and 543 nm laser lines were used for excitation of GFP and RFP, respectively.

Radioiodination of CLV3 and binding assays

The CLV3 peptide contains two histidine residues so it can be radioiodinated using the Iodogen method (Pierce Biochemicals, Inc.) (Mayers and Klostergaard 1983). The tracer was purified by reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). We used a 25 cm × 4.6 mm, 5 m Supelcosil LC-318 HPLC column (Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA) with a 10 to 90% gradient of acetonitrile + 0.1% TFA over 30 minutes (flow rate 1.5 ml/minute) and collected fractions every 0.5 minute. Specific activity of the radiolabeled peptide was determined by measuring the peptide concentration of the tracer with a Micro BCATM Protein Assay Kit (Pierce).

The receptor proteins were transiently expressed in tobacco leaves and as described above and proteins were extracted 2 days after infiltration. The microsomal membrane pellets were washed in protein extraction buffer containing 1% Triton X-100 for 3 hours at 4°C with rotation. A significant proportion of protein of each of the CLV pathway receptors remained in the resulting detergent-washed membrane pellet (Figure 4a, 4b) and this fraction was used in binding assays. The binding assays were carried out as described by Ogawa (Ogawa et al. 2008): 500 μg membrane protein preps or receptor proteins immunoprecipitated with 50 μl protein A agarose beads were resuspended in 200 ul binding buffer (50 mM MES-KOH, 100 mM sucrose, pH 5.5) that contained 100,000 cpm of [125I]-CLV3, with or without 20 μM cold CLV3 peptide for competition. After being incubated on ice for 30 min, the reactions were loaded on top of 1 ml washing buffer (50 mM MES-KOH, 500 mM sucrose, pH 5.5) and were subjected to a 10 min 28,000 g centrifugation to remove unbound [125I]-CLV3. If necessary, after removing most of the supernatant, another 10 min 28,000 g spin was carried out to ensure a tight pellet. For binding kinetics, 500 μg CLV1-GFP, 1mg CLV2-MYC, 100 μg BAM1-GFP or 100 μg BAM2-GFP membrane protein preps were used in binding assays with a series of tracer concentrations from 0.82 nM to 200 nM. Specific binding was calculated by subtracting from total binding the background binding when 20 μM cold peptide is present. For receptor specificity studies, 1mg CLV1-GFP, 1mg CLV2-MYC, 500 μg BAM1-GFP or 500 μg BAM2-GFP membrane protein preps were used in binding assays with or without cold competition from different CLE peptides at the concentration of 10 μM. All the peptides used in this assay are listed in Supplemental Table 2. Radioactivity in the pellets were determined with an automatic gamma counter (Micromedic 4/600 Plus, ICN Biomedicals Inc., Costa Mesa, CA,). Saturation curves and Scatchard plots were generated using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA ). All the binding assays were done with at least three replicates.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Tagged receptor constructs complement meristem mutants.

Supplemental Figure 2. Control co-immunoprecipitations with GFP.

Supplemental Figure 3. Receptor interactions require co-expression.

Supplemental Figure 4. Additional receptor interactions.

Supplemental Figure 5. Scatchard plots for CLV3 CLE receptor binding.

Supplemental Table 1. Antibodies used in this study.

Supplemental Table 2. CLE peptides used in this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jianming Li at the University of Michigan for reading the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health (R01GM62962) and USDA Cooperative Research Extension Service (USDA-2006-35304-17403) to S.E.C.

Contributor Information

Yongfeng Guo, Email: yguo@umich.edu.

Linqu Han, Email: hanl@umich.edu.

Matthew Hymes, Email: matthew_hymes@pall.com.

Robert Denver, Email: rdenver@umich.edu.

References

- Becraft PW. Receptor kinase signaling in plant development. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2002;18:163–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.012502.083431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleckmann A, Weidtkamp-Peters S, Seidel CA, Simon R. Stem cell signaling in Arabidopsis requires CRN to localize CLV2 to the plasma membrane. Plant Physiol. 2010;152:166–176. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.149930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadigan KM, Liu YI. Wnt signaling: complexity at the surface. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:395–402. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark SE. Cell signalling at the shoot meristem. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:276–284. doi: 10.1038/35067079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark SE, Running MP, Meyerowitz EM. CLAVATA1, a regulator of meristem and flower development in Arabidopsis. Development. 1993;119:397–418. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.2.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark SE, Running MP, Meyerowitz EM. CLAVATA3 is a specific regulator of shoot and floral meristem development affecting the same processes as CLAVATA1. Development. 1995;121:2057–2067. [Google Scholar]

- Clark SE, Williams RW, Meyerowitz EM. The CLAVATA1 gene encodes a putative receptor kinase that controls shoot and floral meristem size in Arabidopsis. Cell. 1997;89:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80239-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Journal. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cock JM, McCormick S. A large family of genes that share homology with CLAVATA3. Plant Physiol. 2001;126:939–942. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.3.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong F, Schweizer L, Varmus H. Wnt signals across the plasma membrane to activate the beta-catenin pathway by forming oligomers containing its receptors, Frizzled and LRP. Development. 2004;131:5103–5115. doi: 10.1242/dev.01318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MD, Grossniklaus U. A gateway cloning vector set for high-throughput functional analysis of genes in planta. Plant Physiol. 2003;133:462–469. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.027979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung BJ, Bickle KL, Schrage KJ, Muskett P, Patel K, Clark SE. The CLAVATA1-related BAM1, BAM2 and BAM3 receptor kinase-like proteins are required for meristem function in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2006;45:1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung BJ, Clark SE. Signaling through the CLAVATA1 receptor complex. Plant Mol Biol. 2001;46:505–513. doi: 10.1023/a:1010672910703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung BJ, Clark SE. BAM receptors regulate stem cell specification and organ development through complex interactions with CLAVATA signaling. Genetics. 2008;180:895–904. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.091108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diévart A, Clark SE. LRR-containing receptors regulating plant development and defense. Development. 2004;131:251–261. doi: 10.1242/dev.00998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diévart A, Dalal M, Tax FE, Lacey AD, Huttly A, Li J, Clark SE. CLAVATA1 dominant-negative alleles reveal functional overlap between multiple receptor kinases that regulate meristem and organ development. Plant Cell. 2003;15:1198–1211. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiers M, Golemiec E, Xu J, van der Geest L, Heidstra R, Stiekema W, Liu CM. The 14-Amino Acid CLV3, CLE19, and CLE40 Peptides Trigger Consumption of the Root Meristem in Arabidopsis through a CLAVATA2-Dependent Pathway. Plant Cell. 2005;17:2542–2553. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.034009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiers M, Hause G, Boutilier K, Casamitjana-Martinez E, Weijers D, Offringa R, van der Geest L, van Lookeren Campagne M, Liu CM. Mis-expression of the CLV3/ESR-like gene CLE19 in Arabidopsis leads to a consumption of root meristem. Gene. 2004;327:37–49. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher JC. Shoot and Floral Meristem Maintenance in Arabidopsis. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 2002;53:45–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.092701.143332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher JC, Brand U, Running MP, Simon R, Meyerowitz EM. Signaling of cell fate decisions by CLAVATA3 in Arabidopsis shoot meristems. Science. 1999;283:1911–1914. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5409.1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilboa L, Wells RG, Lodish HF, Henis YI. Oligomeric structure of type I and type II transforming growth factor beta receptors: homodimers form in the ER and persist at the plasma membrane. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:767–777. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.4.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldin CH, Miyazono K, ten Dijke P. TGF-beta signalling from cell membrane to nucleus through SMAD proteins. Nature. 1997;390:465–471. doi: 10.1038/37284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa Y, Shinohara H, Kondo Y, Inoue A, Nakanomyo I, Ogawa M, Sawa S, Ohashi-Ito K, Matsubayashi Y, Fukuda H. Non-cell-autonomous control of vascular stem cell fate by a CLE peptide/receptor system. PNAS. 2008;105:15208–15213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808444105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Z, Jin H, Tzfira T, Li J. Multiple mechanism-mediated retention of a defective brassinosteroid receptor in the endoplasmic reticulum of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2008;20:3418–3429. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.061879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hord CL, Chen C, Deyoung BJ, Clark SE, Ma H. The BAM1/BAM2 receptor-like kinases are important regulators of Arabidopsis early anther development. Plant Cell. 2006;18:1667–1680. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.036871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong S, Trotochaud AE, Clark SE. The Arabidopsis CLAVATA2 gene encodes a receptor-like protein required for the stability of the CLAVATA1 receptor-like kinase. Plant Cell. 1999;11:1925–1934. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.10.1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayes JM, Clark SE. CLAVATA2, a regulator of meristem and organ development in Arabidopsis. Development. 1998;125:3843–3851. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.19.3843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WY, Fujiwara S, Suh SS, Kim J, Kim Y, Han L, David K, Putterill J, Nam HG, Somers DE. ZEITLUPE is a circadian photoreceptor stabilized by GIGANTEA in blue light. Nature. 2007;449:356–360. doi: 10.1038/nature06132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita A, Nakamura Y, Sasaki E, Kyozuka J, Fukuda H, Sawa S. Gain-of-Function Phenotypes of Chemically Synthetic CLAVATA3/ESR-Related (CLE) Peptides in Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007;48:1821–1825. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo T, Nakamura T, Yokomine K, Sakagami Y. Dual assay for MCLV3 activity reveals structure-activity relationship of CLE peptides. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;377:312–316. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.09.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhard M, Laux T. Stem cell homeostasis in the Arabidopsis shoot meristem is regulated by intercellular movement of CLAVATA3 and its sequestration by CLAVATA1. Development. 2003;130:3163–3173. doi: 10.1242/dev.00525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Chory J. A putative leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase involved in brassinosteroid signal transduction. Cell. 1997;90:929–938. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80357-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubayashi Y, Sakagami Y. Phytosulfokine, sulfated peptides that induce the proliferation of single mesophyll cells of Asparagus officinalis L. PNAS. 1996;93:7623–7627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubayashi Y, Sakagami Y. Peptide hormones in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:649–674. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayers GL, Klostergaard J. The use of protein A in solid-phase binding assays: a comparison of four radioiodination techniques. J Immunol Methods. 1983;57:235–246. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa H, Betsuyaku S, Iwamoto K, Kinoshita A, Fukuda H, Sawa S. The receptor-like kinase SOL2 mediates CLE signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008;49:1752–1757. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller R, Bleckmann A, Simon R. The receptor kinase CORYNE of Arabidopsis transmits the stem cell-limiting signal CLAVATA3 independently of CLAVATA1. Plant Cell. 2008;20:934–946. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.057547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni J, Clark SE. Evidence for functional conservation, sufficency, and proteolytic processing of the CLAVATA3 CLE domain. Plant Physiol. 2006;140:1–8. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.072678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oelkers K, Goffard N, Weiller GF, Gresshoff PM, Mathesius U, Frickey T. Bioinformatic analysis of the CLE signaling peptide family. BMC Plant Biol. 2008;8:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-8-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa M, Shinohara H, Sakagami Y, Matsubayashi Y. Arabidopsis CLV3 peptide directly binds CLV1 ectodomain. Science. 2008;319:294. doi: 10.1126/science.1150083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohyama K, Shinohara H, Ogawa-Ohnishi M, Matsubayashi Y. A glycopeptide regulating stem cell fate in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:578–580. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojo E, Sharma VK, Kovaleva V, Raikhel NV, Fletcher JC. CLV3 is localized to the extracellular space, where it activates the Arabidopsis CLAVATA stem cell signaling pathway. Plant Cell. 2002;14:969–977. doi: 10.1105/tpc.002196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song SK, Lee MM, Clark SE. POL and PLL1 phosphatases are CLAVATA1 signaling intermediates required for Arabidopsis shoot and floral stem cells. Development. 2006;133:4691–4698. doi: 10.1242/dev.02652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl Y, Wink RH, Ingram GC, Simon R. A signaling module controlling the stem cell niche in Arabidopsis root meristems. Curr Biol. 2009;19:909–914. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steeves TA, Sussex IM. Patterns in Plant Development. 2. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Stenvik GE, Butenko MA, Urbanowicz BR, Rose JK, Aalen RB. Overexpression of INFLORESCENCE DEFICIENT IN ABSCISSION activates cell separation in vestigial abscission zones in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2006;18:1467–1476. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.042036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenvik GE, Tandstad NM, Guo Y, Shi CL, Kristiansen W, Holmgren A, Clark SE, Aalen RB, Butenko MA. The EPIP peptide of INFLORESCENCE DEFICIENT IN ABSCISSION is sufficient to induce abscission in arabidopsis through the receptor-like kinases HAESA and HAESA-LIKE2. Plant Cell. 2008;20:1805–1817. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.059139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strabala TJ, O’Donnell PJ, Smit AM, Ampomah-Dwamena C, Martin EJ, Netzler N, Nieuwenhuizen NJ, Quinn BD, Foote HC, Hudson KR. Gain-of-function phenotypes of many CLAVATA3/ESR genes, including four new family members, correlate with tandem variations in the conserved CLAVATA3/ESR domain. Plant Physiol. 2006;140:1331–1344. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.075515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W, Kim TW, Oses-Prieto JA, Sun Y, Deng Z, Zhu S, Wang R, Burlingame AL, Wang ZY. BSKs Mediate Signal Transduction from the Receptor Kinase BRI1 in Arabidopsis. Science. 2008;321:557–560. doi: 10.1126/science.1156973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotochaud AE, Hao T, Guang W, Yang Z, Clark SE. The CLAVATA1 receptor-like kinase requires CLAVATA3 for its assembly into a signaling complex that includes KAPP and a Rho-related protein. Plant Cell. 1999;11:393–405. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.3.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzfira T, Tian GW, Lacroix B, Vyas S, Li J, Leitner-Dagan Y, Krichevsky A, Taylor T, Vainstein A, Citovsky V. pSAT vectors: a modular series of plasmids for autofluorescent protein tagging and expression of multiple genes in plants. Plant Mol Biol. 2005;57:503–516. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-0340-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voinnet O, Rivas S, Mestre P, Baulcombe D. An enhanced transient expression system in plants based on suppression of gene silencing by the p19 protein of tomato bushy stunt virus. Plant J. 2003;33:949–956. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Wang Y, Li R, Song X, Wang Q, Huang S, Jin JB, Liu CM, Lin J. Analysis of interactions among the CLAVATA3 receptors reveals a direct interaction between CLAVATA2 and CORYNE in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2010;61:223–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Tagged receptor constructs complement meristem mutants.

Supplemental Figure 2. Control co-immunoprecipitations with GFP.

Supplemental Figure 3. Receptor interactions require co-expression.

Supplemental Figure 4. Additional receptor interactions.

Supplemental Figure 5. Scatchard plots for CLV3 CLE receptor binding.

Supplemental Table 1. Antibodies used in this study.

Supplemental Table 2. CLE peptides used in this study.