Abstract

Macrophages that express representative endoplasmic reticulum (ER) molecules tagged with GFP were generated to assess the recruitment of ER molecules to Leishmania parasitophorous vacuoles (PVs). More than 90% of PVs harboring L. pifanoi or L. donovani parasites recruited calnexin, to their PV membrane (PVM). An equivalent proportion of PVs also recruited the membrane associated soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptors (SNARE), Sec22b. Both ER molecules appeared to be recruited very early in the formation of nascent PVs. Electron microscopy analysis of infected Sec22b/YFP expressing cells confirmed that Sec22b was recruited to Leishmania PVs. In contrast to PVs, it was found that no more than 20% of phagosomes that harbored Zymosan particles recruited calnexin or Sec22b to their limiting phagosomal membrane. The retrograde pathway that ricin employs to access the cell cytosol was exploited to gain further insight into ER-PV interactions. Ricin was delivered to PVs in infected cells incubated with ricin. Incubation of cells with Brefeldin A blocked the transfer of ricin to PVs. This implied that molecules that traffic to the ER are transferred to PVs. Moreover the results show that PVs are hybrid compartments that are composed of both host ER and endocytic pathway components.

Introduction

Upon phagocytosis of particles, nascent phagosomes are formed that are delimited by a membrane initially believed to originate solely from the plasmalemma membrane (PM) (Silverstein, 1977, Ulsamer et al., 1971). The nascent phagosomes then mature into phagolysosomes by sequentially interacting with recycling endosomes (Cox et al., 2000), early and late endosomes, and lysosomes (de Chastellier et al., 1995, Desjardins et al., 1994). Within the past decade an increasing number of studies have proposed that the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is also a key participant in phagocytosis of large particles and in the uptake of microorganisms by phagocytes. In 2001, (Muller-Taubenberger et al., 2001) showed that the knockout of genes that encode two ER proteins (calnexin and calreticulin) severely inhibits inert particles phagocytosis in Dictyostelium sp. During the same year, proteomic analyses revealed that purified latex bead phagosomes contained ER resident molecules such as calnexin, calreticulin and GRp78 (Garin et al., 2001). Proteomic analysis of phagosomes combined with confocal microscopy and electron microscopy studies later showed a direct association between ER and PM during early phagocytosis (Gagnon et al., 2002). These authors then proposed that ER-mediated phagocytosis is an alternative mechanism employed by phagocytes to internalize large particles and microorganisms without significant depletion of their surface area (Gagnon et al., 2002). Further confirmation of the participation of ER in phagocytosis has been obtained in gene silencing and over-expression studies involving the soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptors (SNAREs) syntaxin18 (Hatsuzawa et al., 2006) and Sec22b (Becker et al., 2005). Both of these ER associated SNAREs were shown to regulate fusion between ER and PM during phagocytosis. However, a study on quantitative and dynamic assessment of ER contributions to latex bead phagosome biogenesis (Touret et al., 2005) confirmed the presence of PM molecules at the phagosomal membrane, but could not confirm ER-mediated phagocytosis of inert particles as well as live organisms such as Leishmania in macrophages. This notwithstanding, there have been several observations that have suggested that Leishmania PVs, which are formed after phagocytosis of Leishmania parasites, have interactions with the host ER. This evidence includes the fact that PVs that harbor Leishmania parasites display ER molecules (Gueirard et al., 2008, Kima et al., 2005, Garin et al., 2001); in addition, it has been shown that Leishmania derived molecules can access the MHC class I pathway of presentation through a transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) independent mechanism (Bertholet et al., 2006), which implies that parasite-derived peptides in PVs have direct access to MHC class I molecules

Leishmania parasites reside in PVs with different morphologies: parasites of the L. mexicana complex (L. mexicana, L. pifanoi and L. amazonensis) reside in communal PVs that continuously enlarge as the parasites replicate. In contrast, parasites of the L. donovani complex (L. donovani, L. infantum) reside for the most part in individual compartments from which daughter parasites segregate into new compartments or secondary PVs after parasite replication. Although the involvement of endocytic compartments including lysosomes in the biogenesis of Leishmania PVs is well established (Courret et al., 2002, Antoine et al., 1998) the extent of the interactions of the host cell’s ER with nascent and secondary PV has not been assessed. In this study the interactions between the ER and nascent and maturing PVs in macrophages was assessed. Macrophages either transiently or stably transfected with representative GFP or YFP-tagged ER markers (calnexin and Sec22b) were infected; the resultant PVs were monitored for their recruitment of these molecules over the infection course. We also exploited the trafficking of ricin, a toxin which accesses the cytosol through a retrograde pathway that traverses the ER (Audi et al., 2005), to further characterize host ER and PVs association. The results show that host ER components are continuously recruited to Leishmania PVs.

Results

1.1. Recruitment of calnexin to the Leishmania PV membrane

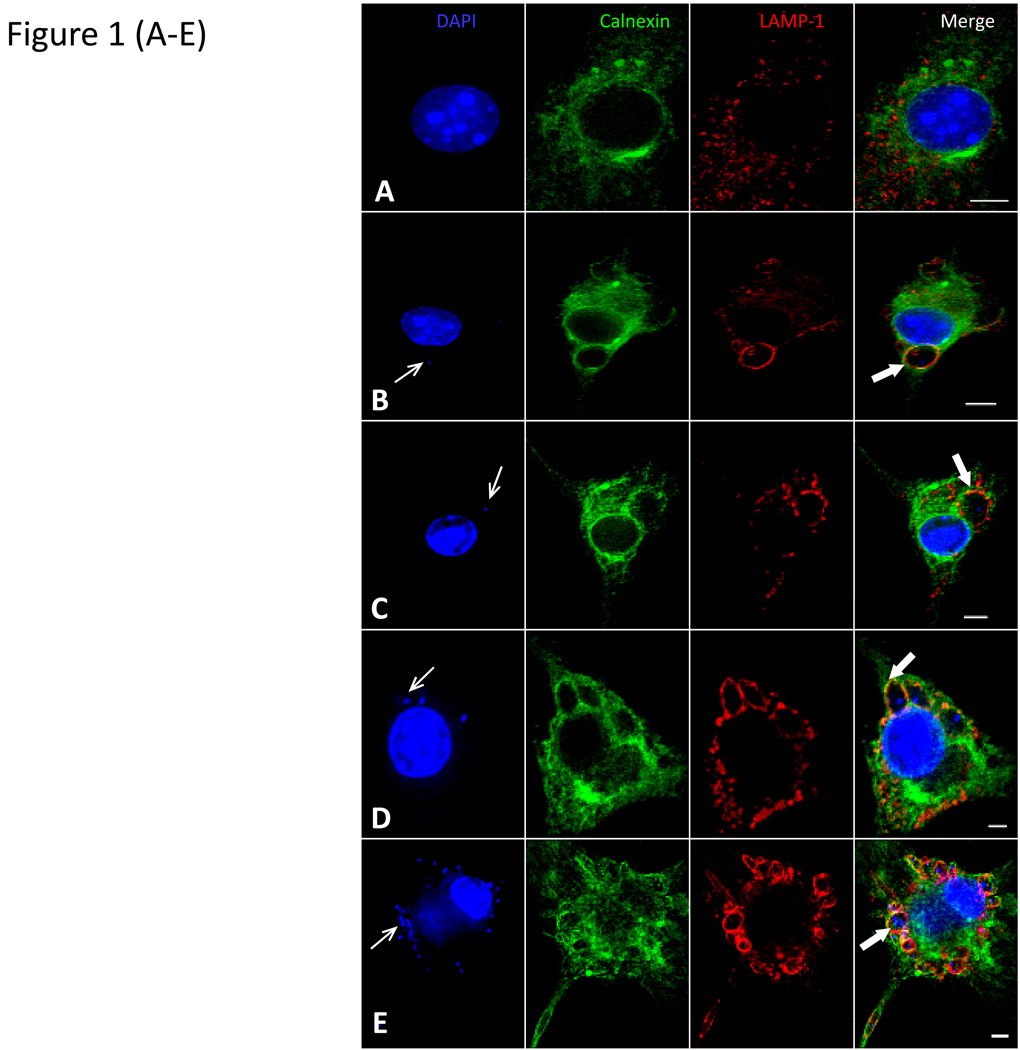

Calnexin is a type I trans-membrane and ER prime resident protein (Leach et al., 2002, Schrag et al., 2001). To investigate the recruitment of host ER integral membrane molecules to the membrane of PVs that harbor Leishmania parasites, we engineered a DNA construct in which the calnexin gene sequence was fused to the c- terminus of a green fluorescence protein (GFP) gene. The ER signal sequence was supplied in the vector but the ER retention signals of calnexin were included in the construct. This construct as well as the empty plasmid, pCMV/myc/ER/GFP, was used to transiently transfect Raw 264.7 macrophages. The distribution pattern of GFP expressed from the plasmid in the absence (Supplemental figure 1) or presence of the calnexin molecule was evaluated (Figure 1). Raw 264.7 macrophages expressing the calnexin/GFP chimeric protein displayed a fluorescence signal pattern that is characteristic of the distribution of the ER; the GFP signal is distributed between a cytosolic mesh-like network and peri-nuclearly (Figure 1A). Moreover, the calnexin/GFP labeling in Raw 264.7 macrophages was in vesicles that were not labeled with anti-LAMP-1 antibodies. Cells labeled with antibodies to calnexin and BiP, another ER resident molecule, had a similar pattern of distribution as did the chimeric calnexin. (Supplemental figure 2).

Figure 1. Distribution of calnexin/GFP in transfected macrophages and recruitment to Leishmania PVs.

The calnexin gene was cloned into the pShooter (pCMV/ER/GFP) plasmid to obtain the pCMV/calnexin/GFP plasmid. This plasmid was purified and transfected into Raw 264.7 macrophages. Transfected cells were then processed in immuno-fluorescence assays with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to reveal nuclei (blue) and anti-LAMP 1 antibody to label late endosomes and lysosomes (red). A) A representative cell that shows the calnexin/GFP distribution pattern in cells transfected with the pCMV/calnexin/GFP plasmid. Transfected cell cultures were infected with Leishmania amastigotes. Infections were stopped at varying times and processed in immunofluorescence assays. Representative images of transfected Raw 264.7 cells infected with L. pifanoi amastigotes for 2 h (B) or 12 h (C) and L. donovani amastigotes for 2 h (D) or 24 h (E) are shown. Thin white arrows point to representative parasites while thick white arrows show the PV membrane. Images were captured with a Zeiss Axiovert 200M fluorescence microscope controlled with Axiovision software. Optical sections from a Z-series were combined to create the images shown. Scale bar = 5 micrometers (5µm)

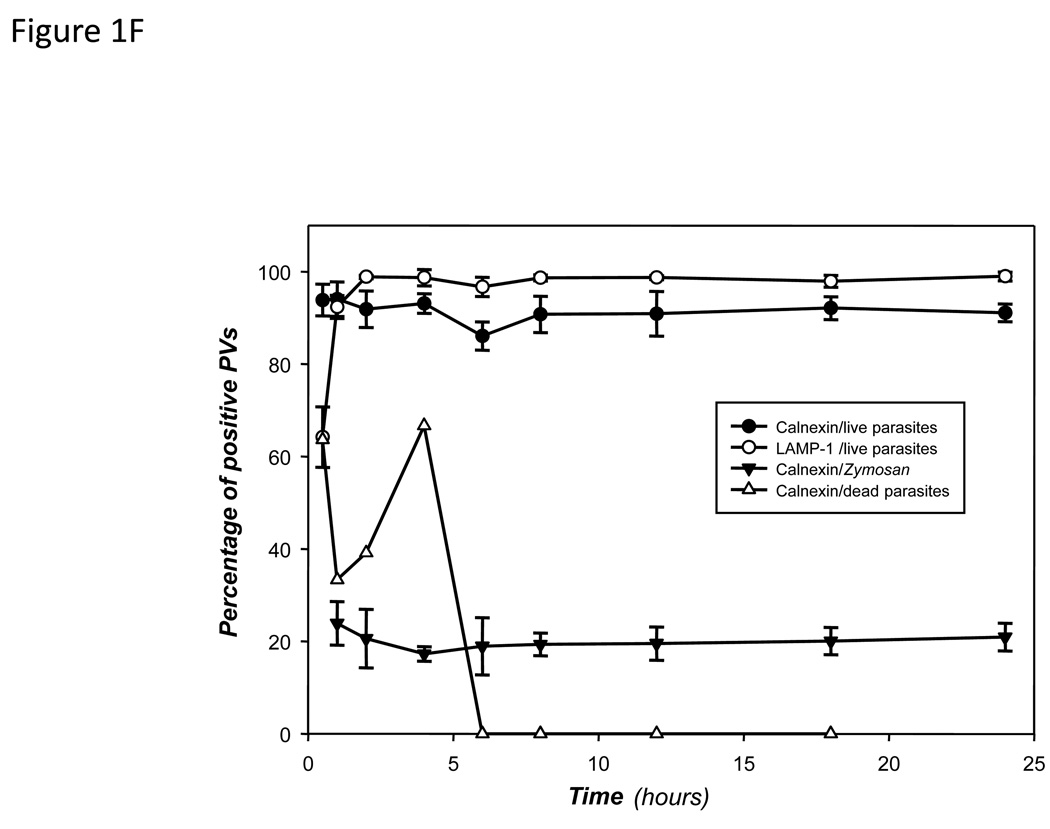

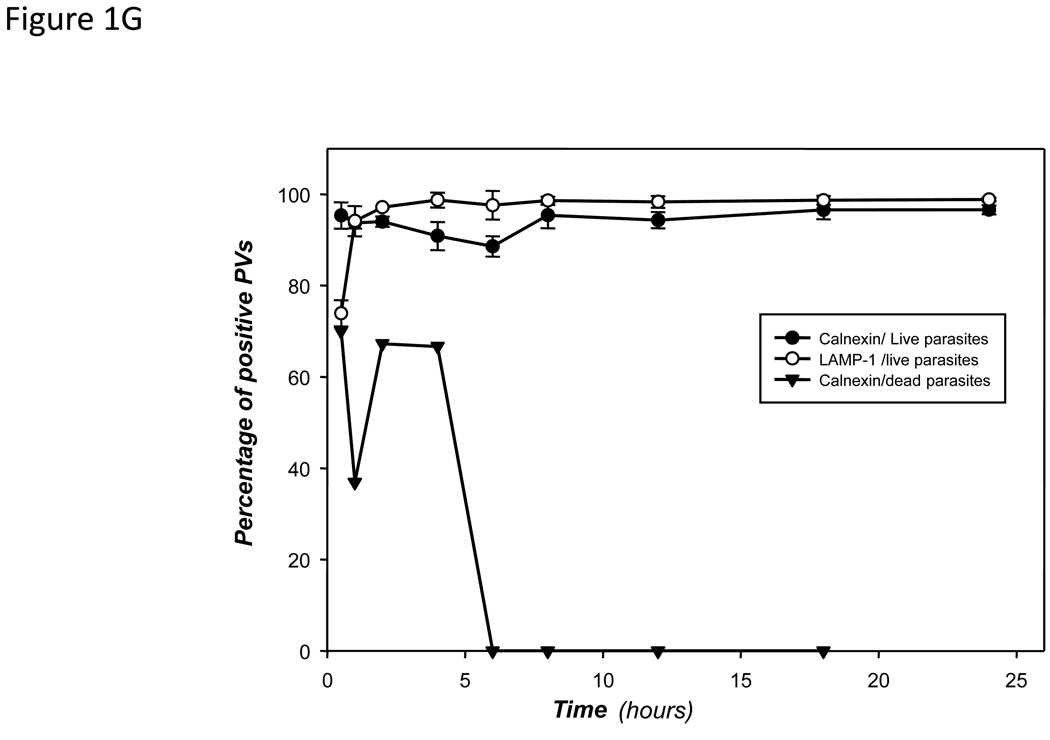

The proportion of PVs harboring L. pifanoi (F) or L. donovani (G) parasites that are positively displaying calnexin/GFP or LAMP-1 during a 24 h course of infection were enumerated and plotted. Also included is the proportion of Zymosan phagosomes displaying calnexin/GFP (F), the proportion of dead L. pifanoi parasites (F) or dead L. donovani parasites (G). Each data point is the mean value from at least three experiments in which at least 150 vacuoles were counted per experiment. Graphs were made using the Sigma plot software. The difference between the proportions of PVs that recruited calnexin as compared to Zymosan phagosomes was tested in a paired t-test at all time points. The p-value in each case was <0.001. .

After validating that calnexin/GFP localized in the ER of transfected macrophages, these cells were infected with L. pifanoi parasites obtained from axenic amastigote cultures. Infected cells were monitored beginning at 15 minutes after incubation of macrophages with parasites and then periodically over a period of 24 h. PVs that harbor L. pifanoi parasites become progressively distended over this time course. Images in Figure 1B & C show representative examples of Raw 264.7 transfected cells at 2 and 12 h post infection. Both calnexin/GFP and LAMP-1 were displayed on the membrane of PVs. Enumeration of Leishmania PVs that displayed calnexin/GFP on their PV membrane showed that except for the first hour post infection, the display of calnexin/GFP on PVs parallels the recruitment of LAMP-1 (Figure 1F). Unlike the recruitment of Lamp1, which is gradual in the first hour post-infection, more than 85% of L. pifanoi PVs were positive for GFP-calnexin from the earliest time of sampling (Figure 1F). The recruitment of LAMP-1 is as previously described (Lang et al., 1994). Similar observations were made with the promastigote forms of L. pifanoi and L. amazonensis parasites (not shown).

The pattern of calnexin recruitment to Leishmania PVs was compared to its recruitment to phagosomes that harbor Zymosan particles or dead parasites. Transfected cells were incubated with Zymosan particles and the phagosomes harboring these particles were sampled through the same time course as Leishmania-infected cells. Approximately 95% of Zymosan-containing phagosomes became LAMP-1 positive after 1 h (not shown). Even though some of these Zymosan-containing phagosomes recruited impressive levels of calnexin, no more than 20% of these phagosomes were calnexin/GFP positive over the 24 h period (Figure 1F). Greater variability in the recruitment profile of calnexin/GFP was observed with phagosomes that harbored dead Leishmania parasites (Figure 1F). Up to 60% of these phagosomes initially recruited calnexin/GFP, however, dead parasites were completely destroyed in PVs at about 12 h after phagocytosis.

Parasites of the L. donovani complex set up morphologically distinct vacuoles; these parasites live for the most part in individual PVs, which segregate into secondary PVs that harbor individual parasites after parasite replication. The recruitment of calnexin/GFP to PVs harboring L. donovani parasites was assessed in parallel experiments. Representative images of PVs harboring L. donovani parasites that displayed positive recruitment of calnexin/GFP are shown (Figure 1D & E). Both primary and secondary PVs (Figure 1E) that are formed after parasite replication, displayed calnexin/GFP and LAMP-1 on their PV membrane. Enumeration of these PVs too revealed that greater than 95% recruited calnexin/GFP and LAMP-1 (Figure 1G). Some dead L. donovani parasites were initially directed to calnexin/GFP positive phagosomes. Taken together, even though Leishmania parasites like Zymosan particles and dead parasites are internalized by phagocytosis, the majority of Leishmania parasites appear to be directed to compartments that are delimited by a membrane composed of both LAMP-1 and the ER membrane resident calnexin. This is in contrast to the majority of inert particles that are directed into compartments that do not recruit calnexin.

1.2. Recruitment of Sec22b to the PV membrane

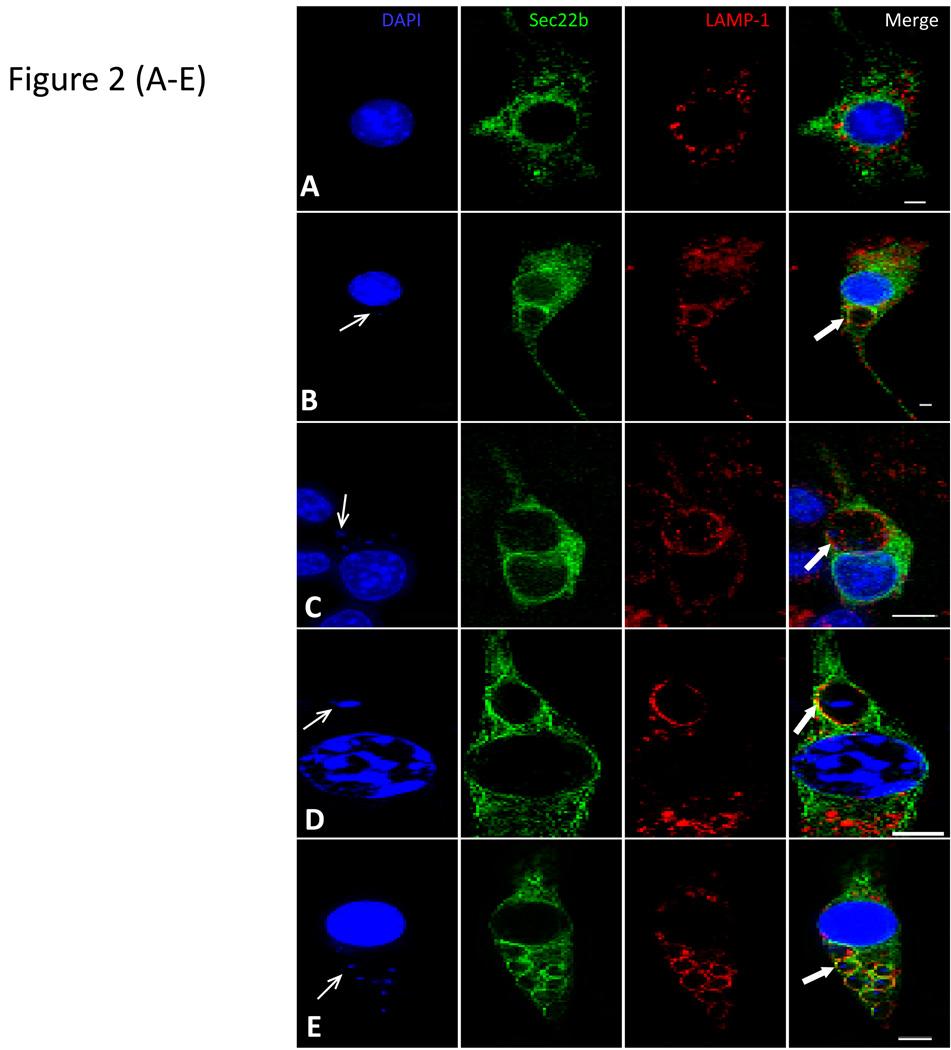

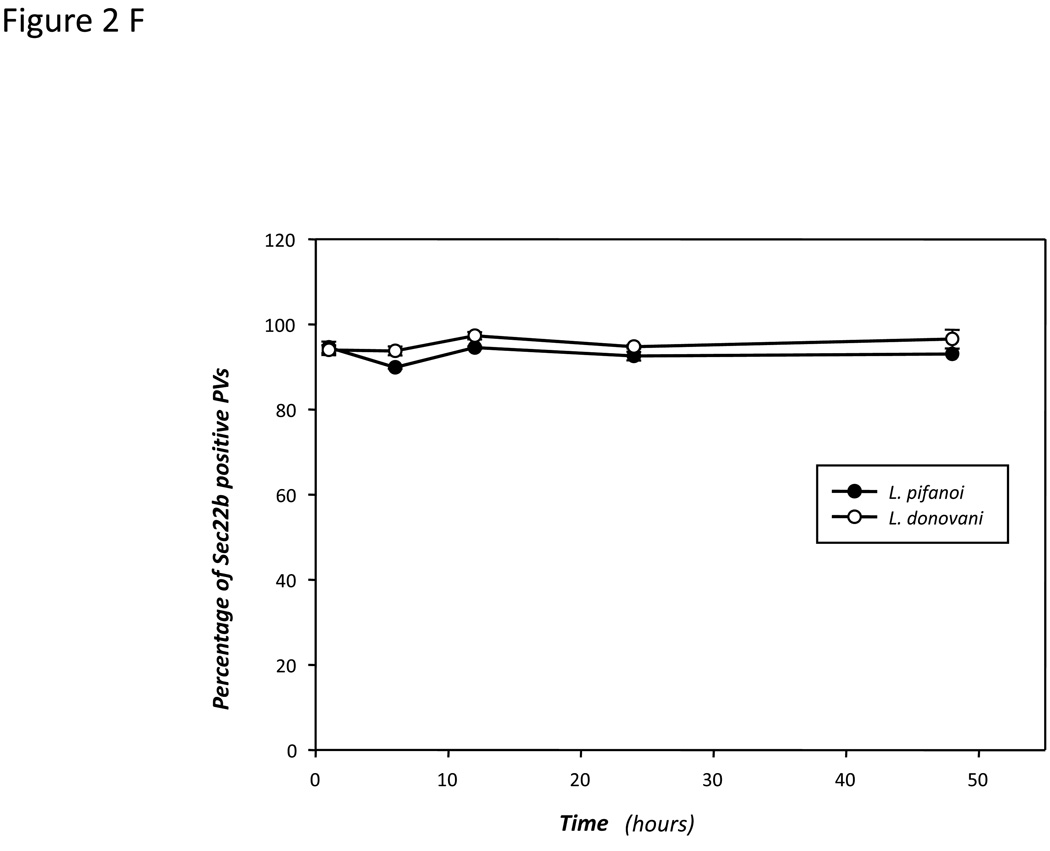

To obtain additional evidence on the interactions between PVs and the host cell’s ER we assessed the recruitment of the ER membrane associated SNARE, Sec22b to Leishmania PVs. Sec22b is one of at least four SNARE proteins that have been implicated in the mediation of ER vesicle transport (Aoki et al., 2008). Given its role in vesicle fusion, its recruitment to PVs would provide some insight into the mechanism by which ER molecules are recruited to PVs. The construction of the pmVenus vector that encodes YFP fused to the N-terminus of Sec22b was described previously (Hatsuzawa et al., 2006). Stable lines of J774 cells expressing this molecule and transiently transfected Raw 264.7 were infected with Leishmania parasites. Cells transfected with the pmVenus/YFP vector exhibited diffuse YFP distribution (Supplemental Figure 1B). Moreover, there was no preferential recruitment of YFP to PVs in those cells that were transfected with the pmVenus/YFP vector (Supplemental Figure 1C). In contrast in cells transfected with pmVenus/Sec22b/YFP the pattern of Sec22b/YFP distribution in transfected cells was consistent with the ER distribution in mammalian cells; Sec22b/YFP distribution overlaps with the distribution pattern of endogenous BiP and calnexin stained with primary antibodies (Supplemental Figure 2C & D). Moreover, Sec22b/YFP molecules were localized to compartments that were devoid of LAMP-1 (Figure 2A). Raw 264.7 macrophages transfected with pmVenus/Sec22b/YFP were then infected with L. pifanoi parasites and sampled over a 24-hour infection period as described above. Representative images of cells infected for 2 and 12 h are shown in Figure 2B&C; LAMP-1 and Sec22b/YFP are both displayed on the membrane of PVs. Infections of transfected cells were also performed with L. donovani parasites. Representative images of PVs that displayed positive recruitment of Sec22b/YFP to both primary and secondary PVs are shown (Figure 2D & E). Enumeration of PVs that displayed Sec22b/YFP revealed that over 90% of PVs that harbored L. pifanoi or L. donovani parasites were Sec22b/YFP positive during a 48h infection course (Figure 2F). These experiments were also performed with J774 cell lines stably expressing the Sec22b/YFP chimera, and similar results were obtained (data not shown).

Figure 2. Distribution of Sec22b/YFP in transfected macrophages and recruitment of Sec22b to Leishmania PVs.

Sec22b was cloned into the pmVenus based plasmids and used to transfect Raw 264.7 macrophages (Hatsuzawa et al, 2006). Transfected cells were processed in immuno-fluorescence assays with DAPI (blue) to reveal nuclei; and anti-LAMP-1 (red) to reveal late endosomes and lysosomes. A) A representative transfected Raw 264.7 cell expressing Sec22/YFP is shown.

Transfected cells were infected with L. pifanoi amastigotes for 2 h (B) and 24 h (C) or L. donovani amastigotes for 2 h (D) and 24 h (E) and then processed in immunofluorescence assays. The figures show representative images of PVs in infected cells. Images were captured on a Zeiss Axiovert 200M microscope with a plan neofluar 100x/1.3 oil immersion objective. Images series over a defined z-focus range were acquired and processed with 3D deconvolution software supplied with AxioVision. An extended focus function was used to merge optical sections to generate images presented in the figures. Scale bar = 5 micrometers (5µm). Thin arrows point to representative parasites; thick arrows point to the PV membrane. The proportion of L. pifanoi and L. donovani PVs that positively recruited Sec22b/YFP during a 48 h course of infection was estimated and plotted (F). More than 150 PVs containing live Leishmania parasites were screened. The experiments were repeated at least three times, graphs of the mean values were made using the Sigma plot software.

1.3. Electron microscopy (EM) analysis

To confirm that ER membrane molecules are recruited and displayed on the membrane of Leishmania PVs, we performed immuno-EM analyses on cells expressing Sec22b/YFP either transiently or stably. YFP distribution in these cells as well as in cells transfected with the pmVenus/YFP was evaluated with an antibody to GFP (see Materials and Methods section), which was followed with a secondary antibody conjugated to gold particles. The GFP labeling patterns in pmVenus/Sec22b/YFP transfected cells confirmed that in these cells gold particles (18nM gold particles [arrows]) were localized to the perinuclear membrane and to ER cisterns or tubules; in contrast, in pmVenus/YFP transfected cells YFP was distributed randomly including in the nucleus (Supplemental Figure 1).

For the EM experiments it was preferable for technical reasons to evaluate PVs in the stable J774 line expressing Sec22b/YFP; since all cells expressed this chimeric molecule every infected cell on the thin sections be potentially informative. Figure 3 shows representative images of a PV with a single parasite (Figure 3A) or a cell with multiple PVs (Figures 3B) harboring L. donovani parasites; the gold particles, which represent Sec22b/YFP molecules are on the PV membrane and the peri-nuclear ER membrane (bold white arrows). This was in contrast to PVs in J774 cells stably transfected with the pmVenus/YFP plasmid. In those cells the YFP (thin arrows point to gold particles) is neither localized to the ER nor the PV membrane (Figure 3C). These results complement the evidence obtained from fluorescence assays that had shown that the host cell ER membrane associated molecules are recruited to PVs and displayed on the PV membrane.

Figure 3. Immuno-EM analysis of ER components recruitment to Leishmania PVs.

Stably transfected J774 cells were infected with L. donovani parasites and then processed for immuno-EM analysis. Sections on Nickel grids were incubated with a rabbit anti-GFP antibody followed by a secondary antibody conjugated to 15nm gold particles. The grids were post-stained with 0.5% uranyl acetate and lead citrate and were examined with a Hitachi TEM H-7000 (Pleasanton, CA) operated at 80 kV. A-&B are representative infected J774 cells expressing Sec22b/YFP. A) PV with single parasite; B) A cell with multiple PVs; and Zoomed out area. Bold white arrows point to perinuclear ER and PV membrane lined with gold particles. Cells stably transfected with the pmVenus vector were infected as well. (C) shows a pmVenus/YFP transfected cell that is infected. Thin arrows point to gold particles randomly distributed in the cell. These images are representative of images obtained from at least 2 experiments. N= macrophage nucleus; P= Leishmania parasite

1.4. Accumulation of host ER contents in Leishmania PV lumen

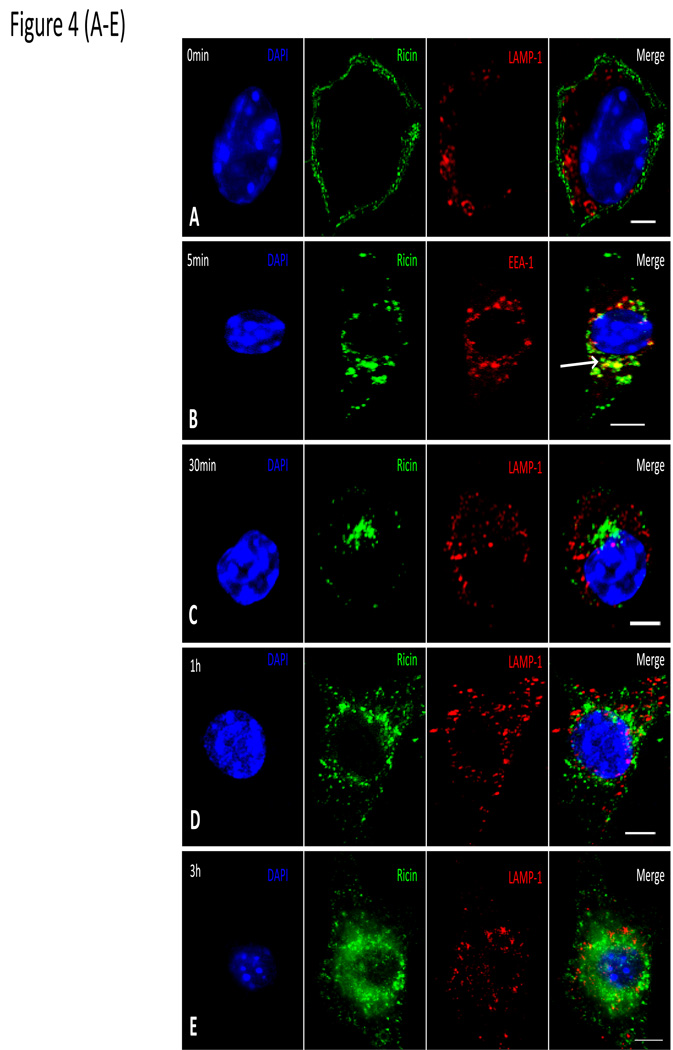

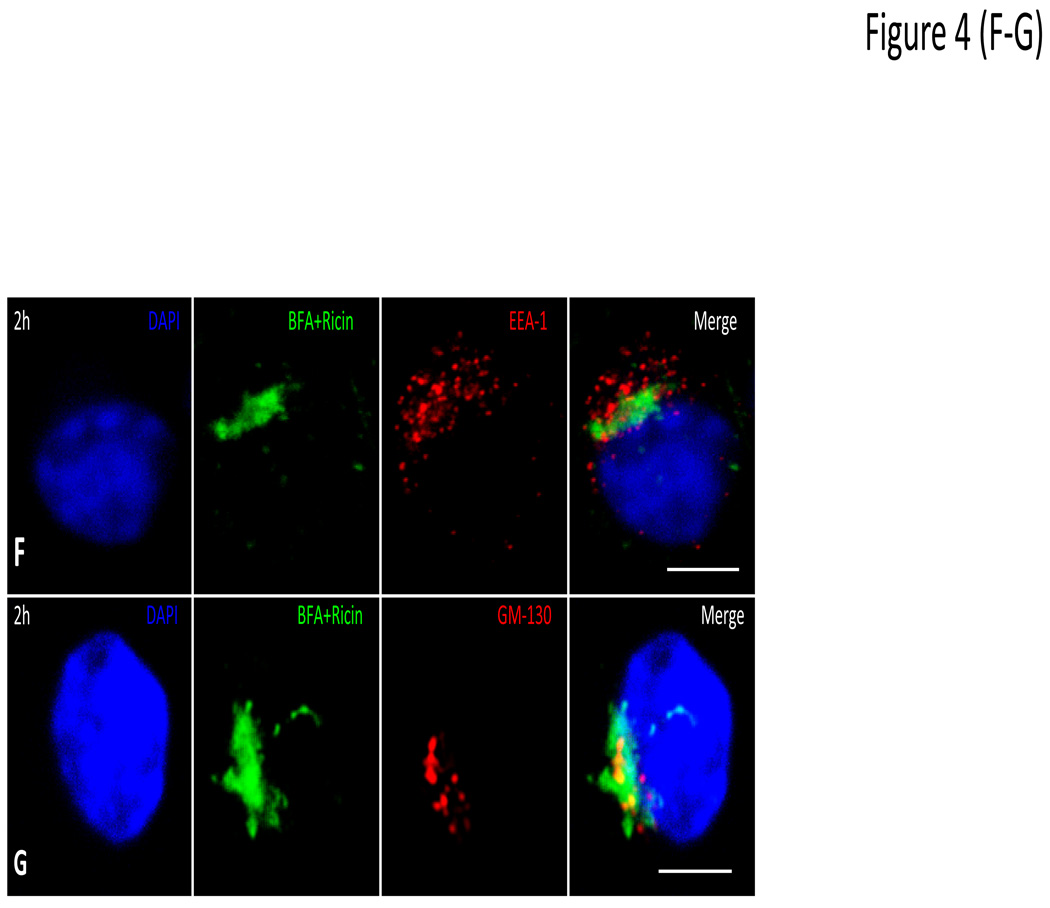

In light of the observations that an integral ER membrane protein and an ER membrane associated molecule are recruited to PVs we next determined whether molecules in the ER lumen also gain access to the lumen of Leishmania PVs. To address this question, we elected to monitor the trafficking of ricin toxin in macrophages infected with either L. donovani or L. pifanoi strains. Ricin enters cells by endocytosis then traffics by a retrograde pathway through early endosomes, the trans-Golgi network (TGN) and then the ER before reaching the cytosol (Skanland et al., 2007, Slominska-Wojewodzka et al., 2006, Audi et al., 2005). Some of the evidence in support of this pathway included the observation that ricin trafficking to the cytosol is independent of Rab7. We reasoned that if ricin is recruited to PVs, it would imply that the contents of the compartments in the pathway of ricin including the ER lumen, can be delivered to PVs. Initial experiments were performed to confirm the trafficking scheme of ricin in uninfected RAW 264.7 macrophages (Figure 4). After a brief pulse with ricin (0 min), the plasma membrane (PM) of cells became coated with fluorescent ricin molecules (green) (Figure 4A); within 5 min, ricin was internalized and enclosed in endosomes. This was verified by demonstrating that ricin is found in vesicles that display the Early endosome antigen (EEA1) (Figure 4B – [arrows point to endosomes labeling with both ricin and EEA1]). From early endosomes, ricin was transferred successively into the TGN (Figure 4C) and ER (Figure 4D) before reaching the cytosol (Figure 4E). At no point is ricin observed in LAMP-1 positive compartments. Further evidence that ricin traverses the TGN and ER was obtained in experiments with brefeldin A (BFA), which blocks retrograde transport from the TGN to the ER (Plaut et al., 2008, Mardones et al., 2006). Figure 4F & G show that in the presence of BFA, ricin accumulates in a compartment that is no longer reactive with anti-EEA1 antibodies (Fig. 4F). It however accumulates in a compartment that is partially reactive with anti-GM130, which suggests that it is most likely retained in the TGN (Figure 4G). GM130 is a matrix protein localized in the cis golgi, which explains its partial localization with ricin (Nakamura et al., 1995).

Figure 4. Trafficking of ricin in non-infected Raw 264.7 macrophages.

Raw 264.7 macrophages on coverslips were pulsed with fluoresceinated ricin at a concentration of 10ug/ml in complete RPMI medium. The cultures were rinsed and incubated with complete medium at 37°C and under 5% CO2. Coverslips were removed after the pulse (0 min) (A) then after chase for 5 min (B); some coverslips were stained with anti-EEA1 to visualize early endosomes. Bold arrow in the merged image shows vesicles that are both EEA1 and ricin positive. Representative images after 30 min (C), and 1 h (D) and 3 h (E) show labeling of cell nucleus with DAPI dye (blue) and LAMP-1 using an anti-LAMP-1 antibody (red). Some samples were pre-treated with BFA at a concentration of 5µg/ml for 2 h before ricin treatment. Coverslips obtained after 2 h chase were labeled with anti EEA1 (F) or anti-GM130 (G) to localize compartment in which ricin was arrested after BFA treatment. Samples were captured with a Zeiss Axiovert 200M fluorescence microscope controlled with Axiovision software. These images are representative of images from 3 experiments. Scale bar = 5µm.

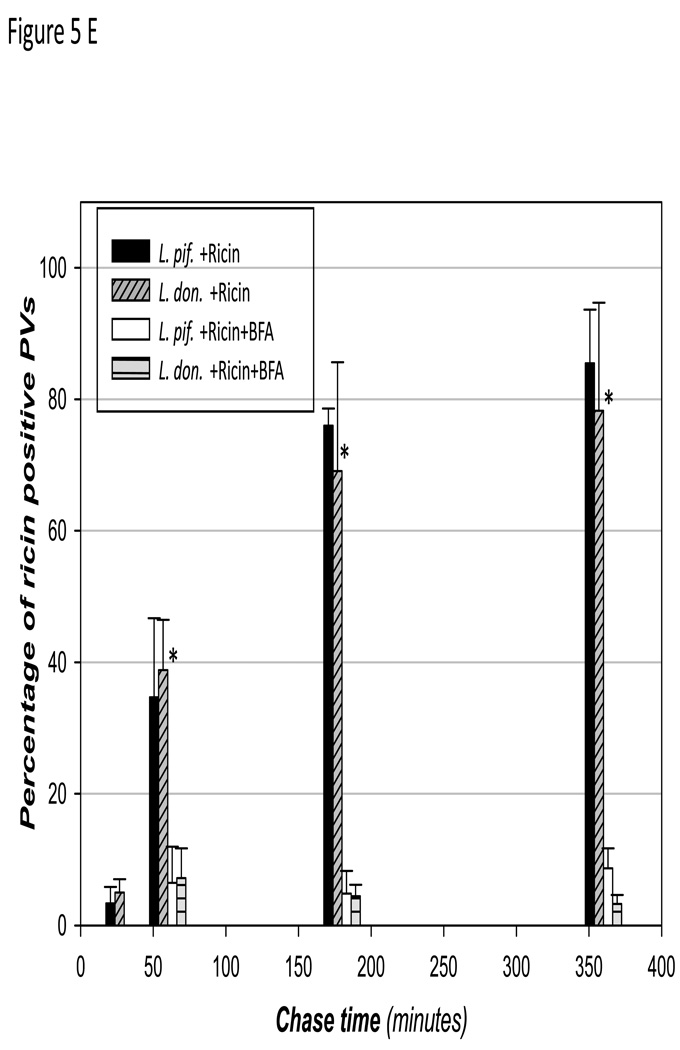

Mindful of potential interactions of ricin in early endosomes (Sandvig et al., 2002b) with nascent PVs, infections were established for 4–6 h before pulsing cells with ricin for five minutes. We had shown earlier that by 4 h post infection, PVs are LAMP-1positive and would not be expected to interact with early endosomes. After the ricin pulse, ricin was chased into infected cells, which were evaluated after an additional 5 min, 30 min, 1 h, 3 h and 6 h. Figure 5 shows representative images of ricin in infected cells at 0 min, 1 h and 3 h. By the 3 hr point ricin is within PVs that are clearly delimited by a membrane that contains LAMP-1 (Figure 5C-zoom). Enumeration of PVs with ricin showed that there is a gradual increase in the number of PVs in both L. donovani and L. pifanoi cells that accumulated ricin (Figure 5D). BFA treatment blocks the accumulation of ricin in PVs (Figure 5D). The gradual accumulation of ricin in PVs suggested that recruitment of ER contents into the PV might be the result of vesicular delivery. Taken together the studies with ricin demonstrated that molecules in the ER lumen are delivered continuously to Leishmania PVs.

Figure 5. Ricin accumulates in Leishmania PVs during infection in Raw 264.7 macrophages.

Raw 264.7 macrophages were infected for at least 4h before the cultures were incubated with ricin at a concentration of 10µg/ml, and the reaction was chased at 37°C and under 5% CO2 atmosphere. At 0 min (A), 1 h (B) and 3 h (C) the coverslips were recovered and processed to reveal nuclei (blue) and LAMP-1 (red). Thin white arrows point to parasites in the infected cells. Thick arrow points to ricin within a PV. Scale bar = 5µm. PVs harboring either L. pifanoi or L. donovani that were ricin positive were enumerated after 30 min, 1 h, 3 h and 6 h. The percentage of PVs that were ricin positive was plotted (E). Incubations were done in the presence of BFA and enumerated as well. The difference in the percentage of PVs that were positively displaying ricin was significantly different from the percentage of PV with ricin in cells incubated with BFA. * denotes a P value < 0.01. Each data point was compiled from at least 3 experiments.

Discussion

In phagocytes, Leishmania parasites are internalized by phagocytosis; most of the evidence to date has shown that these parasites are directed into PVs that follow a maturation scheme that is similar to that of phagosomes harboring inert particles. We show here that in addition to interactions with late endocytic pathway vesicles, Leishmania PVs interact continuously with the host cell’s ER and acquire both membrane associated and luminal ER molecules. The biogenesis and maturation scheme of Leishmania PVs is apparently different from the maturation of phagosomes that harbor inert particles; PVs are hybrid compartments.

Phagocytosis enables professional phagocytes to internalize large particles, while their total cell surface remains relatively constant. Numerous studies have considered the biogenesis and maturation of the new membrane-bound structures that harbor large particles; nascent phagosomes sequentially interact with early endosomes, late endosomes and lysosomes to mature into phagolysosomes (Harrison et al., 2003, Vieira et al., 2003). Both membranous and luminal contents of endocytic compartments are believed to be acquired by mechanisms including local or focal exocytosis, which involve secretion and fusion of endosomes and lysosomes to the site of phagosome formation (Tapper et al., 2002, Bajno et al., 2000). The presence of endogenous ER resident proteins such as calnexin and calreticulin on the phagosome membrane is being reported increasingly (Lee et al., 2009, Houde et al., 2003, Gagnon et al., 2002). However, the mechanisms by which these molecules access phagosomal compartments are still being debated (Huynh et al., 2007, Touret et al., 2005, Gagnon et al., 2005, Gagnon et al., 2002, Houde et al., 2003). Suppression of genes responsible for both calnexin and calreticulin expression significantly hindered the process of phagocytosis in Dictyostelium sp (Muller-Taubenberger et al., 2001). Other studies have also shown that Sec22b and syntaxin 18 (ER related SNAREs) form complexes with Sso1-Sec9C (PM associated SNAREs) to regulate the fusion between ER and PM under the phagocytic cup (Hatsuzawa et al., 2006, Becker et al., 2005). Phagosome proteomic analysis revealed the abundance of ERS-24/Sec22b molecules at the early stage of phagosomes biogenesis (Gagnon et al., 2002a). In the studies presented above we observed that at the earliest sampling time (15 min) the majority of nascent PVs displayed ER molecules, which suggested that these molecules were delivered/recruited at the earliest point of PV formation.

The focus of our studies though was to assess the evolving composition of PVs; specifically, their acquisition of ER components overtime. Our data showed that the ER markers, calnexin and Sec22b as well as LAMP-1, the latter a marker of late endosomes and lysosomes, are positively recruited onto the membrane lining Leishmania PVs, throughout a 24h infection period in macrophages. The display of calnexin and Sec22b on greater than 90% of PVs was in contrast to the situation with Zymosan particles where no more than 20% of their phagosomes displayed these molecules. As we noted, the situation with phagosomes containing dead parasites was intermediate between the observations of Zymosan particles and live Leishmania parasites. Differences between the Zymosan phagosomes that recruited ER molecules and those that were devoid of these molecules were not readily obvious. Since a higher proportion of PVs recruited ER marker molecules as compared to Zymosan phagosomes and phagosomes that harbor dead particles, this suggested that there is a unique interaction between Leishmania and host cells that promotes their PVs association with the ER. The observations of ER-PV interactions are in part in agreement with a recent report that found that a sub-population of L. donovani promastigotes in neutrophils selectively develop in ER-like compartments (Glucose 6-phosphatase and calnexin positive) that are non-lytic and devoid of lysosomal properties (Gueirard et al., 2008). Unlike the findings in that study that parasites in compartments with lysosomal properties were dead, our studies show that in macrophages, live Leishmania parasites reside in compartments that contain both ER-like and lysosomal properties. The differences in PV characteristics observed in both of these studies might suggest that PV development is determined in part by the characteristics of the host cell.

To further assess the extent of host ER association with Leishmania PVs, we exploited the pathway that ricin toxin traverses to access the cytosol of cells. Ricin has been shown to enter cells by endocytosis and to then migrate from endosomes through a retrograde pathway that traverses the trans Golgi network (TGN) and ER before reaching the cytoplasm (Sandvig et al., 2002a). Access to this pathway is sensitive to BFA treatment (Audi et al., 2005, Skanland et al., 2007). The data presented above showed that ricin can access the Leishmania PV lumen via the TGN and ER. The transport of ricin from Golgi to ER, and subsequently from ER to Leishmania PVs was effectively blocked by BFA treatment. A delay was observed between the accumulation of ricin in the ER and its accumulation in Leishmania PVs. This suggested that these two compartments are not continuous. ER contents are most likely delivered to PVs through vesicular fusion; the presence of Sec22b, which mediates ER vesicle fusion, on PVs supports this view. An alternative delivery scenario that is not supported by our data is that ER and PV membranes fuse and become continuous, which would then permit the exchange of ER contents with PVs. A recent study on the interactions of the Toxoplasma containing vacuole and the host cell’s ER suggested the existence of a pore between these compartments through which ER molecules could be delivered (Goldszmid et al., 2009).

The observation that Leishmania PVs recruit both endocytic pathway and endoplasmic reticulum components suggests that PVs are atypical compartments. They obviously differ from pathogen containing vacuoles that also interact extensively with the host cell’s ER. Legionella containing vacuoles (LCV) for example, avoid interactions with the endocytic pathway by elaborating molecules that are delivered to the cell cytosol via the type IV secretion apparatus (Paumet et al., 2009, Roy et al., 1998). LCVs recruit ER components through a mechanism that is sensitive to BFA treatment and has been shown to be ARF1 dependent (Shin et al., 2008).

The observations presented here documenting continuous interactions of PVs with the ER has implications for our understanding of how Leishmania molecules might access the MHC class I pathway of antigen presentation. Although a few reports have addressed this issue, it is still not known where Leishmania molecules are processed and loaded onto MHC class I molecules for presentation to CD8+ T cells by infected macrophages. The data presented here suggest that MHC class I molecules in the ER might be accessible to parasite molecules within PVs. Future studies on that topic and on how the presence of ER components in PVs benefits the Leishmania parasite should prove to be quite informative.

Materials and methods

2.1. Parasites and cell lines

The Leishmania pifanoi promastigotes (MHOM/VE/57/LL1) line was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). It was grown in Schneiders medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 10 µg/ml gentamicin at 23°C. L. donovani strain 1S-CL2D from Sudan, World Health Organization (WHO) designation: (MHOM/SD/62/1S-CL2D) was obtained from Dr. Debrabant (USDA, MD). Promastigotes of this parasite strain were grown in Medium-199 (with Hank's salts, Gibco Invitrogen Corp.) supplemented to a final concentration of 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 µM adenosine, 23 µM folic acid, 100IU and 100 µg/ml each of penicillin G and streptomycin, respectively, 1×BME vitamin mix, 25 mM Hepes, and 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated (45 min at 56 °C) fetal bovine serum, adjusted with 1 N HCl to pH 6.8 at 26 °C. Generation of amastigotes forms was carried out as described (Debrabant et al., 2004). L. donovani axenic amastigotes parasites were maintained in RPMI-1640/MES/pH 5.5 medium at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5–7% CO2 in air. Similarly, L. pifanoi amastigotes were maintained in the amastigote medium above at 34 °C. The RAW 264.7 murine macrophage cell line (obtained from ATCC) was cultured in RPMI supplemented with 10 % fetal calf serum and 100 units Penicillin/Streptomycin at 37°C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

2.2. Vectors construction and expression

To prepare the calnexin construct, total RNA was extracted from murine Raw264.7 macrophages using the RNeasy Kit from Qiagen Inc (Valencia, CA). The calnexin gene was directly amplified from total RNA employing specific primer sequences (Forward: 5’ AAG GAA AAA A GCG GCC GC C ATG ATG GAC ATG ATG ATG ACG 3’ and Reverse: 5’ AAG GAA AAA AA GCG GCC GCT CAC TCT CTT CGT GGC TTT CTG 3’) in a one-step RT-PCR protocol (Qiagen Inc). The amplified gene was cloned in frame at the Not I site of the pShooter vector pCMV/ER/GFP/c-myc vector (Invitrogen Inc; Carlsbad, CA), such that GFP is expressed at the N-terminus of the protein. The signal peptide sequence (from the vector) and retention signal (from gene) were selected to direct and localize the expressed protein in host ER compartments. The selected clone was sent to University of Florida Genetics and Cancer Institute, Sequencing Core facility (Gainesville, FL) for sequencing and to confirm the RT-PCR product. After sequencing, endotoxin- free plasmids containing the calnexin/GFP tagged gene were obtained and used to transfect murine Raw 264.7 macrophages with a nucleofection kit from Amaxa Inc. (Gaithersburg, MD). Sec22b constructs in pmVenus plasmid as well as J774 cells expressing these Sec22b/YFP proteins were described previously (Hatsuzawa et al., 2009, Hatsuzawa et al., 2006). The pmVenus/Sec22b/YFP plasmid and the pmVenus/YFP plasmids were purified and used to transfect Raw 264.7 cells.

2.3. Nucleofection of Raw 264.7 macrophages

About 1.7×10 7 cells at the exponential growth phase were put into 50 ml centrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 90xg (RCF) for 10 min. The supernatant was carefully discarded and 100 µl of the nucleofection solution was added to the cell pellet. Approximately 15 ug of DNA was transferred into cells, and the mixture was gently transferred into a 0.4 cm cuvette (Amaxa). Specific conditions for nucleofection of Raw 264.7 supplied by the manufacturer (Amaxa Inc.) was selected to electroporate the cells. After electroporation, 500 µl of DMEM complete medium pre-warmed at 37°C was immediately added to the cuvette containing electroporated cells. They were transferred into a sterile cell culture dish holding 12 mm glass cover-slides, and incubated for 24h at 37°C under 5% CO2 atmosphere, before subsequent use.

2.4. Infections

Infections were carried out following standard protocols previously described (Kima et al., 2005). Raw 264.7 macrophages were seeded on 12mm round glass cover slips inside cell culture Petri dishes and incubated at 37°C under 5% CO2 atmosphere. The next day, Raw 264.7 macrophages on cover slips were co-incubated with Leishmania parasites in RMPI complete medium at a 1:10 cell-to-parasites ratio. The infections were performed at either 37°C (for L. donovani) or 34°C (for L. pifanoi) under 5% CO2 atmosphere. Infection of Raw 264.7 macrophages or J774 cells with either the promastigote or the amastigote stage of the parasites mentioned above, results in productive infections in which parasite replication commences at 12 to 24 H post infection. In experiments in which the time course of ER recruitment to PVs was assessed, infections were initiated with 1:20 cell-to parasites ratio and then the cultures were washed at the first sampling time to remove free parasites. To stop the infection, cover-slips of infected macrophages were washed three times in 1x phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA)/1x PBS solution for at least 20min at room temperature.

2.5. Immunofluorescence labeling and imaging

Transfected or non-transfected cells infected on coverslips were fixed with 2% para-formaldehyde (PFA) for at least 30 minutes at room temperature and processed as previously described (Pham et al., 2005). These coverslips were washed twice in 1xPBS and incubated in 50mM NH4Cl/1xPBS solution for 5 min. After two washes in 1x PBS, the preparations were blocked in 2% fat-free milk/1x PBS binding buffer (BB) supplemented with 0.05% saponin, as a cell membrane permeabilizing agent. Some coverslips were then incubated with one of the following primary antibodies to Early endosome antigen 1 (EEA1), calnexin, GM130 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, San Jose CA), BiP, (BD Biosciences, San Jos CA) and/or 1D4B reactive with late endosome and lysosomal associated membrane proteins (LAMP-1), (obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma bank, Iowa City, IA). Coverslips were then incubated with the appropriate Alexa Fluor secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes Carlsbad CA). into which the nucleic acid dye 4',6-diamidino-2 phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) had been added. Cover slips were mounted on glass slides with ProLong antifade (Molecular Probes). They were examined on a Zeiss Axiovert 200M microscope with a plan neofluar 100x/1.3 oil immersion objective. Images were captured with an AxioCam MRm camera controlled by AxioVision software. Images series over a defined z-focus range were acquired and processed with 3D deconvolution software supplied with AxioVision. An extended focus function was used to merge optical sections to generate images presented in the figures.

2.6. Immuno-electron microscopy

Infected macrophage cultures were spun down and resuspended in the growth medium supplemented with 0.15 M sucrose. The macrophages were gently spun down and the cell pellet was rapidly frozen with a HPM 100 high-pressure freezer (Leica, Bannockburn, IL). The whole process from cell harvesting to freezing was completed within several minutes. The frozen cell samples were freeze-substituted in 0.1% uranyl acetate and 0.25% glutaraldehyde in acetone at −80° C for 2 days. After freeze-substitution, the samples were warmed up to −50 °C over 30 hrs, washed 4 times with dry acetone at −50° C, then, embedded in HM20 acrylic resin (Ted Pella, Inc., Redding, CA) at −50°C. The resin was polymerized under ultraviolet light at −50°C for 36 hrs. All the freeze-substitution, temperature transition, resin embedding, and UV-polymerization were carried out in the AFS2 automatic freeze substitution system (Leica, Bannockburn, IL). The HM20 embedded samples were sliced into 100 nm thin sections that were placed on nickel grids, which were then immunogold labeled with an anti-GFP antibody (1/50 dilution v/v) as described by Kang and Staehelin (Kang et al., 2008). The immunogold labeled sections were post-stained with an aqueous uranylacetate solution (2% w/v) and a lead citrate solution (26g L−1 lead nitrate and 35g L−1 sodium citrate) and examined with a Hitachi TEM H-7000 (Pleasanton, CA) operated at 80 kV

2.7. Ricin experiments

Ice-cold fluorescein labeled Ricinus communis agglutinin II (RCA II) (called ricin here) purchased from Vector Laboratories Inc (Burlingame, CA) was added to cell cultures at a final concentration of 10ug/ml. The cultures were incubated on ice for 10 min to ensure the adherence of ricin molecules to the surface of cells. They were then incubated at 37°C under 5% C02 atmosphere to initiate the internalization of ricin infected macrophages. After a five min pulse excess ricin was removed by rinsing the culture twice with RPMI complete medium. Ricin was chased into cells at 37°C under 5% C02 atmosphere; samples were collected at 30 min, 60 min, 3 h and 6 h respectively. In some experiments, cells were treated with 5ug/mL BFA (from Invitrogen) for 2 h prior to adding ricin. BFA was maintained in those cells for the duration of the experiment. In ricin experiments of infected cells, Raw 264.7 macrophages were incubated with either L. donovani or L. pifanoi parasites for at least 4 h at 34 or 37°C with 5% C02, to generate mature PVs that would no longer interact with early endosomes containing ricin. The samples were washed three times in 1xPBS solution to remove non-internalized parasites. Growth medium was added to the infected cell culture and incubated for an additional 2hrs to ensure complete internalization of parasites attached to host cell membranes. The infected cell cultures were then placed on ice for 10 min before incubation with ricin. Following the initiation of the ricin chase, infected macrophages on coverslips were collected at the same intervals listed above. Some samples of infected macrophages were incubated with BFA as described above. Samples from different time-points were processed in immunofluorescence assays as described above and cover slips were mounted on glass slides with ProLong antifade (Molecular Probes). They were examined on a Zeiss Axiovert 200M microscope with a plan neofluar 100x/1.3 oil immersion objective. Images were captured as described above.

2.8. Statistics

Data analysis and generation of graphs was performed on sigma-plot software. Each data point is the mean ± standard deviation from at least three observations. T-test was performed to assess differences; they were considered significant at a P value of ≤0.05.

Supplementary Material

The empty pShooter (pCMV/ER/GFP) plasmid and pmVenus plasmids were purified and used to transfect Raw 264.7 macrophages. A) A representative cell that shows the pattern of GFP distribution in cells transfected with (pCMV/ER/GFP). B) Representative cells that show the pattern of YFP expression in cells transfected with the pmVenus plasmid. C) Representative cell transfected with pmVenus and infected with Leishmania. The cells were stained with DAPI (blue) and anti-LAMP-1 (green).

Transfected cells as well as non-transfected cells were labeled with primary antibodies to ER molecules. A) Calnexin/GFP transfeted cells were labeled with an anti-calnexin antibody. B) Untransfected Raw 264.7 cells were labeled with and anti-calnexin and anti LAMP-1 antibody. C) Sec22/YFP transfected and infected cells were labeled with anti-BiP antibody. D) Sec22/YFP expressing cells were labeled with an anti-calnexin antibody. All cells were stained with DAPI

Transiently transfected Raw 264.7 cells overexpressing Sec22b/YFP (A) or YFP alone (B) were processed for immuno-EM analysis. Sections on Nickel grids were incubated with a rabbit anti-GFP antibody followed by a secondary antibody conjugated to 18nm gold particles. The grids were post-stained with 0.5% uranyl acetate and lead citrate and were examined with a Zeiss EM-10CA transmission electron microscope. Bold arrows point to representative18nm gold particles.

3. Acknowledgement

We thank Johnathan Canton for assistance with performing EM experiments. These studies were supported by an NIH R01.

Contributor Information

Blaise Ndjamen, Department of Microbiology and Cell Science, University of Florida.

Byung-Ho Kang, Department of Microbiology and Cell Science, University of Florida.

Kiyotaka Hatsuzawa, Department of Cell Science, Institute of Biomedical Sciences, Fukushima Medical University School of Medicine.

Peter E. Kima, Department of Microbiology and Cell Science, University of Florida

Reference

- Antoine JC, Prina E, Lang T, Courret N. The biogenesis and properties of the parasitophorous vacuoles that harbour Leishmania in murine macrophages. Trends in microbiology. 1998;6:392–401. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(98)01324-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki T, Kojima M, Tani K, Tagaya M. Sec22b–dependent assembly of endoplasmic reticulum Q-SNARE proteins. The Biochemical journal. 2008;410:93–100. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audi J, Belson M, Patel M, Schier J, Osterloh J. Ricin poisoning: a comprehensive review. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;294:2342–2351. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.18.2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajno L, Peng X, Schreiber A, Moore H, Trimble W, Grinstein S. Focal exocytosis of VAMP3-containing vesicles at sites of phagosome formation. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:697–706. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.3.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker T, Volchuk A, Rothman JE. Differential use of endoplasmic reticulum membrane for phagocytosis in J774 macrophages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:4022–4026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409219102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertholet S, Goldszmid R, Morrot A, Debrabant A, Afrin F, Collazo-Custodio C, et al. Leishmania antigens are presented to CD8+ T cells by a transporter associated with antigen processing-independent pathway in vitro and in vivo. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950) 2006;177:3525–3533. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.3525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courret N, Frehel C, Gouhier N, Pouchelet M, Prina E, Roux P, Antoine JC. Biogenesis of Leishmania-harbouring parasitophorous vacuoles following phagocytosis of the metacyclic promastigote or amastigote stages of the parasites. Journal of cell science. 2002;115:2303–2316. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.11.2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox D, Lee DJ, Dale BM, Calafat J, Greenberg S. A Rab11-containing rapidly recycling compartment in macrophages that promotes phagocytosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:680–685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Chastellier C, Lang T, Thilo L. Phagocytic processing of the macrophage endoparasite, Mycobacterium avium, in comparison to phagosomes which contain Bacillus subtilis or latex beads. European journal of cell biology. 1995;68:167–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debrabant A, Joshi MB, Pimenta PF, Dwyer DM. Generation of Leishmania donovani axenic amastigotes: their growth and biological characteristics. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:205–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desjardins M, Huber LA, Parton RG, Griffiths G. Biogenesis of phagolysosomes proceeds through a sequential series of interactions with the endocytic apparatus. The Journal of cell biology. 1994;124:677–688. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.5.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon E, Bergeron JJ, Desjardins M. ER-mediated phagocytosis: myth or reality? Journal of leukocyte biology. 2005;77:843–845. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0305129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon E, Duclos S, Rondeau C, Chevet E, Cameron PH, Steele-Mortimer O, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum-mediated phagocytosis is a mechanism of entry into macrophages. Cell. 2002;110:119–131. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00797-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garin J, Diez R, Kieffer S, Dermine JF, Duclos S, Gagnon E, et al. The phagosome proteome: insight into phagosome functions. The Journal of cell biology. 2001;152:165–180. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.1.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldszmid R, Coppens I, Lev A, Caspar P, Mellman I, Sher A. Host ER-parasitophorous vacuole interaction provides a route of entry for antigen cross-presentation in Toxoplasma gondii-infected dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206:399–410. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueirard P, Laplante A, Rondeau C, Milon G, Desjardins M. Trafficking of Leishmania donovani promastigotes in non-lytic compartments in neutrophils enables the subsequent transfer of parasites to macrophages. Cellular microbiology. 2008;10:100–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison R, Bucci C, Vieira O, Schroer T, Grinstein S. Phagosomes fuse with late endosomes and/or lysosomes by extension of membrane protrusions along microtubules: role of Rab7 and RILP. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:6494–6506. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.18.6494-6506.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatsuzawa K, Hashimoto H, Arai S, Tamura T, Higa-Nishiyama A, Wada I. Sec22b is a negative regulator of phagocytosis in macrophages. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:4435–4443. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-03-0241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatsuzawa K, Tamura T, Hashimoto H, Yokoya S, Miura M, Nagaya H, Wada I. Involvement of syntaxin 18, an endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-localized SNARE protein, in ER-mediated phagocytosis. Molecular biology of the cell. 2006;17:3964–3977. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-12-1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houde M, Bertholet S, Gagnon E, Brunet S, Goyette G, Laplante A, et al. Phagosomes are competent organelles for antigen cross-presentation. Nature. 2003;425:402–406. doi: 10.1038/nature01912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh K, Kay J, Stow J, Grinstein S. Fusion, fission, and secretion during phagocytosis. Physiology (Bethesda) 2007;22:366–372. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00028.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang B, Staehelin L. ER-to-Golgi transport by COPII vesicles in Arabidopsis involves a ribosome-excluding scaffold that is transferred with the vesicles to the Golgi matrix. Protoplasma. 2008;234:51–64. doi: 10.1007/s00709-008-0015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kima PE, Dunn W. Exploiting calnexin expression on phagosomes to isolate Leishmania parasitophorous vacuoles. Microbial pathogenesis. 2005;38:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang T, de Chastellier C, Frehel C, Hellio R, Metezeau P, Leao Sde S, Antoine JC. Distribution of MHC class I and of MHC class II molecules in macrophages infected with Leishmania amazonensis. Journal of cell science. 1994;107(Pt 1):69–82. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach MR, Cohen-Doyle MF, Thomas DY, Williams DB. Localization of the lectin, ERp57 binding, and polypeptide binding sites of calnexin and calreticulin. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:29686–29697. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202405200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, Jethwaney D, Schilling B, Clemens D, Gibson B, Horwitz M. The Mycobacterium bovis BCG phagosome proteome. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:32–53. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900396-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardones GA, Snyder CM, Howell KE. Cis-Golgi matrix proteins move directly to endoplasmic reticulum exit sites by association with tubules. Molecular biology of the cell. 2006;17:525–538. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-05-0447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Taubenberger A, Lupas AN, Li H, Ecke M, Simmeth E, Gerisch G. Calreticulin and calnexin in the endoplasmic reticulum are important for phagocytosis. The EMBO journal. 2001;20:6772–6782. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.23.6772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura N, Rabouille C, Watson R, Nilsson T, Hui N, Slusarewicz P, et al. Characterization of a cis-Golgi matrix protein, GM130. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1715–1726. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.6.1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paumet F, Wesolowski J, Garcia-Diaz A, Delevoye C, Aulner N, Shuman H, et al. Intracellular bacteria encode inhibitory SNARE-like proteins. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7375. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham NK, Mouriz J, Kima PE. Leishmania pifanoi amastigotes avoid macrophage production of superoxide by inducing heme degradation. Infection and immunity. 2005;73:8322–8333. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.12.8322-8333.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaut RD, Carbonetti NH. Retrograde transport of pertussis toxin in the mammalian cell. Cellular microbiology. 2008;10:1130–1139. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy C, Berger K, Isberg R. Legionella pneumophila DotA protein is required for early phagosome trafficking decisions that occur within minutes of bacterial uptake. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:663–674. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandvig K, Grimmer S, Lauvrak SU, Torgersen ML, Skretting G, van Deurs B, Iversen TG. Pathways followed by ricin and Shiga toxin into cells. Histochemistry and cell biology. 2002a;117:131–141. doi: 10.1007/s00418-001-0346-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandvig K, van Deurs B. Transport of protein toxins into cells: pathways used by ricin, cholera toxin and Shiga toxin. FEBS letters. 2002b;529:49–53. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03182-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrag JD, Bergeron JJ, Li Y, Borisova S, Hahn M, Thomas DY, Cygler M. The Structure of calnexin, an ER chaperone involved in quality control of protein folding. Molecular cell. 2001;8:633–644. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin S, Roy C. Host cell processes that influence the intracellular survival of Legionella pneumophila. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:1209–1220. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein SC. Endocytic uptake of particles by mononuclear phagocytes and the penetration of obligate intracellular parasites. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1977;26:161–169. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1977.26.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skanland SS, Walchli S, Utskarpen A, Wandinger-Ness A, Sandvig K. Phosphoinositide-regulated retrograde transport of ricin: crosstalk between hVps34 and sorting nexins. Traffic (Copenhagen, Denmark) 2007;8:297–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slominska-Wojewodzka M, Gregers TF, Walchli S, Sandvig K. EDEM is involved in retrotranslocation of ricin from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cytosol. Molecular biology of the cell. 2006;17:1664–1675. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-10-0961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapper H, Furuya W, Grinstein S. Localized exocytosis of primary (lysosomal) granules during phagocytosis: role of Ca2+-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation and microtubules. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950) 2002;168:5287–5296. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.5287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touret N, Paroutis P, Terebiznik M, Harrison RE, Trombetta S, Pypaert M, et al. Quantitative and dynamic assessment of the contribution of the ER to phagosome formation. Cell. 2005;123:157–170. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulsamer AG, Wright PL, Wetzel MG, Korn ED. Plasma and phagosome membranes of Acanthamoeba castellanii. The Journal of cell biology. 1971;51:193–215. doi: 10.1083/jcb.51.1.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira O, Bucci C, Harrison R, Trimble W, Lanzetti L, Gruenberg J, et al. Modulation of Rab5 and Rab7 recruitment to phagosomes by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:2501–2514. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.7.2501-2514.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The empty pShooter (pCMV/ER/GFP) plasmid and pmVenus plasmids were purified and used to transfect Raw 264.7 macrophages. A) A representative cell that shows the pattern of GFP distribution in cells transfected with (pCMV/ER/GFP). B) Representative cells that show the pattern of YFP expression in cells transfected with the pmVenus plasmid. C) Representative cell transfected with pmVenus and infected with Leishmania. The cells were stained with DAPI (blue) and anti-LAMP-1 (green).

Transfected cells as well as non-transfected cells were labeled with primary antibodies to ER molecules. A) Calnexin/GFP transfeted cells were labeled with an anti-calnexin antibody. B) Untransfected Raw 264.7 cells were labeled with and anti-calnexin and anti LAMP-1 antibody. C) Sec22/YFP transfected and infected cells were labeled with anti-BiP antibody. D) Sec22/YFP expressing cells were labeled with an anti-calnexin antibody. All cells were stained with DAPI

Transiently transfected Raw 264.7 cells overexpressing Sec22b/YFP (A) or YFP alone (B) were processed for immuno-EM analysis. Sections on Nickel grids were incubated with a rabbit anti-GFP antibody followed by a secondary antibody conjugated to 18nm gold particles. The grids were post-stained with 0.5% uranyl acetate and lead citrate and were examined with a Zeiss EM-10CA transmission electron microscope. Bold arrows point to representative18nm gold particles.