Abstract

Purpose

To delineate the vitreal pharmacokinetics of dipeptide monoester prodrugs of ganciclovir (GCV) with conscious rabbit model using ocular microdialysis and to compare with published results from anesthetized model.

Methods

New Zealand albino male rabbit was selected as the animal model. Conscious animal ocular microdialysis technique with permanently implanted probes was employed to delineate the pharmacokinetics of GCV, l-valine-GCV (Val-GCV), and dipeptide monoester GCV prodrugs [Val-Val and l-glycine-Val (Gly-Val)] after intravitreal administration.

Results

This work employs conscious model to evaluate vitreal pharmacokinetic parameters and compares the results with previously published data from anesthetized animal, thereby demonstrating the effect of anesthesia on the vitreal disposition of dipeptide prodrugs of GCV. Results have revealed that area under curve (AUC), clearance, and last measured plasma concentration (Clast) for all 4 compounds were significantly altered in a conscious animal relative to the anesthetized model, while mean residence time (MRT) was significantly reduced. However, the AUCs of regenerated Val-GCV and GCV from Gly-Val-GCV and Val-Val-GCV were found to be unchanged, suggesting higher ocular metabolism in conscious animals.

Conclusion

This study for the first time delineates the vitreal pharmacokinetics of a GCV prodrug in conscious animals and compares the data with anesthetized animals. Lower vitreal exposure levels were obtained in case of conscious animal model; however, the elimination rates were not influenced by anesthesia.

Introduction

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) retinitis is characterized by retinal necrosis, granular lesions, and retinal edema.1,2 If left untreated CMV retinitis also leads to blurring of central vision, photopsias, floaters, blind spots, and visual field loss.3 CMV retinitis patients are at major risk of inflammation of retina, hemorrhage, and retinal detachment, which eventually may lead to permanent blindness. Although highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has significantly lowered the number of AIDS patients with CMV retinitis, it is still the leading cause of blindness in patients who are not on HAART.4–8

In HCMV retinitis, the inner layer of the retinal blood vessels are initially infected, which eventually spread outward to the other retinal layers, including retinal pigment epithelium (RPE).9 The exact mechanism of viral spread in the retina is not well understood; however, CMV first penetrates the retinal blood vessels, after which it spreads into the cells of various layers of neural retina.10,11 The key factor in the progression of CMV retinitis is the replication of virus in the retinal cells, which occurs in the endothelial cells of retinal blood vessels, leading into the breakdown of inner blood retinal barrier (BRB). Breakdown can eventually lead to the migration of virus particles toward the RPE, nonpigmented epithelium, and retinal glial cells.1,12 RPE may become disorganized in some cases, which could result in the breakdown of outer BRB. Such processes could be followed by accumulation of fluid in the subretinal space, leading to retinal hemorrhage and detachment.1,12–14

Ganciclovir (GCV: 9-[[2-hydroxyl-1-(hydroxyl-methyl) ethoxy] methyl] guanine), a 2′-deoxyguanosine analog, was the first Food and Drug Administration–approved drug for the treatment of HCMV retinitis. GCV has significant activity against cytomegalovirus; however, virustatic properties require continuous maintenance therapy in addition to the induction regimen to prevent disease relapse. Owing to poor oral bioavailability, daily infusion of GCV is necessary. However, systemic toxicity and poor ocular drug penetration with such infusions have prompted the development of local GCV therapy, mostly through direct intravitreal administration of solutions and nonbiodegradable implants. Nevertheless, intravitreally administered GCV indicated for cytomegalovirus retinitis has poor retinal permeability, the sanctuary site of HCMV. Earlier studies from our laboratory have utilized lipophilic and transporter-targeted prodrug approach to deliver higher GCV concentrations to the retinal tissues.15,16 In one study several dipeptide ester prodrugs were synthesized and evaluated for their vitreal pharmacokinetics parameters in anesthetized animal model using an ocular microdialysis technique. These prodrugs appear to permeate deeper into the retina after intravitreal administration relative to GCV.16

Ocular microdialysis technique to estimate drug and metabolite concentrations in the aqueous and vitreous fluid is a significant technique.17 Earlier studies both from our own as well as other laboratories have extensively applied this technique to study ocular pharmacokinetics of several drugs and prodrugs.18–22 Moreover, conscious animal model for ocular microdialysis has already been developed and validated.17,23–27 Studies from our laboratory have demonstrated the effect of probe implantation in the rabbit eye on vitreal protein levels and pharmacokinetics.17,23 The studies have also validated the method of such probe implantation and recommended that the appropriate recovery time must be allowed before commencing any pharmacokinetic study in conscious animal model.

This study compares vitreal pharmacokinetics with or without the influence of anesthesia. Ketamine and xylazine are commonly used in combination to induce anesthesia in rabbits. This combination has been proven to produce suppressive effects on the heart and respiratory rates as well the intraocular pressure (IOP). These effects may have an impact on the disposition of drugs in the posterior segment.17,28,29

We report in this article vitreal pharmacokinetics of various GCV prodrugs in a conscious animal model and compared the results with the previously published data from our laboratory in anesthetized animals.16

Methods

GCV was obtained as a generous gift from Hoffman La Roche. Previously synthesized GCV prodrugs were administered by intravitreal injection.30 Linear microdialysis probes (MD-2000, 0.32 × 10 mm, polyacrylo nitrile membrane, and 0.22 mm tubing) employed for vitreous sampling were obtained from BAS Microdialysis. Microdialysis pump (CMA/102) for perfusing the isotonic buffer saline was procured from CMA/Microdialysis. Surgical equipment was obtained from Henry Schein Surgical Equipment, and sutures were purchased from Ethicon, Inc. Ketamine HCl was supplied by Fort Dodge Animal Health, and xylazine by Bayer Animal Health. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)–grade solvents were procured from Fisher Scientific.

Animals

Adult male New Zealand albino rabbits weighing between 2 and 2.5 kg were obtained from Myrtle's Rabbitry. This research was conducted under aseptic conditions strictly according to Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology statement for the use of animals in ophthalmic and vision research. Protocol for performing all the surgical procedure was also approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Missouri–Kansas City (Kansas City, MO).

Probe recovery

In vitro probe calibration was performed by placing the probe in isotonic phosphate-buffered saline (IPBS; pH 7.4) containing the appropriate compound (drug or prodrug or both) of a known concentration. The probe was perfused at a flow rate of 2 μL/min with IPBS, and the dialysate was collected every 20 min for 1 h. Relative in vitro recovery of respective compound(s) was calculated by the following equation.

|

(1) |

where Cd is the dialysate concentration and Cs the known concentration of a compound. Concentrations in vitreous humor were calculated by dividing the dialysate concentration with the in vitro probe recovery value.

Surgery

Animals were divided into 4 groups (n = 4/group). Linear microdialysis probes were implanted into the Male New Zealand albino rabbit vitreous by a previously published procedures.17,23 Rabbits were anesthetized with ketamine hydrochloride (35 mg/kg) and xylazine (3.5 mg/kg) administered intramuscularly. To the anesthetized rabbits, a drop of tetracaine (0.5%) was administered to their right eye, which was followed by the topical instillation of 25% povidone iodine. After 5 min, the eye was proptosed, and a 25-gauge needle was inserted diametrically across the posterior chamber and about 3–4 mm below the limbus on the nasal side, so that it traverses through the center of vitreous humor. Upon exiting, the outlet end of linear probe was carefully placed into the needle at bevel edge. It was then slowly pulled back leaving the dialysis membrane of the probe (center part) within the sphere of mid vitreous. The probe was placed in such a manner that the entire membrane area lay in the vitreous chamber; it was slightly angled, before suturing, so as to avoid contact with the lens. It was finally fastened by conjunctival sutures (6′ nylon sutures). The probe shafts were then pierced under the upper eye lid and placed under the forehead skin. Probe ends exit through the forehead skin near the ears and the opening was closed by sutures. Intravitreal cephalexin (250 μg) and topical gentamicin (0.3%) were administered to prevent any onset of ocular infections, and antibiotic skin cream has been applied above the skin sutures. The probes were intermittently perfused with (pH 7.4) IPBS at a flow rate of 2 μL/min, with the help of a CMA/100 microinjection pump. Animals were then allowed to recuperate for 5 days after surgery before any experiments were initiated. Rabbits were briefly anesthetized before intravitreal administration and then were placed in steel restrainers during rest of the sampling period. Subsequent to drug administration, microdialysis samples were collected at 2 μL/min every 20 min for 10 h. All procedures were performed under aseptic conditions.

Intravitreal dose of GCV was 0.4 μmol (100 μg GCV) in a volume of 50 μL of sterile IPBS (pH 7.4) and doses of valine-GCV (Val-GCV), Val-Val-GCV, and glycine-Val-GCV (Gly-Val-GCV) were 0.4 μmol each.16

HPLC analysis

Microdialysis samples were analyzed with a HPLC system comprising of a HP 1050 series quaternary gradient pump (Agilent Technologies), Alcott 718AL refrigerated autosampler (Alcott Chromatography, Inc.), HP 1100 series fluorescence detector (Agilent Technologies; λex 265 nm and λem 380 nm), HP 3395 integrator (Agilent Technologies), and the Phenomenex. Separation of the compounds was achieved with C8 (4.6 × 250) column, C8 guard column, and mobile phase comprised of 15 mM phosphate buffer (pH 2.5) and acetonitrile. Depending upon the prodrug being analyzed, the proportion of acetonitrile was varied (2%–5%v/v).

Data analysis

All experiments were conducted in quadruplicate and the results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Student's t-test was applied to detect statistical significance and P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Vitreal concentration–time data were analyzed with a pharmacokinetic software package WinNonlin, version 5.0. Pharmacokinetic parameters were determined employing noncompartmental analysis. Area under the vitreous and plasma concentration–time curves were estimated by the linear trapezoidal method with extrapolation to infinite time. Slopes of the terminal phase of vitreous and plasma profiles were estimated by log-linear regression, and the terminal rate constant (λz) was derived from the slope. Terminal vitreous and plasma half-lives were calculated by Equation 2.

|

(2) |

Results

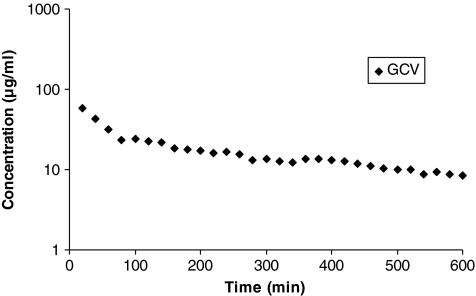

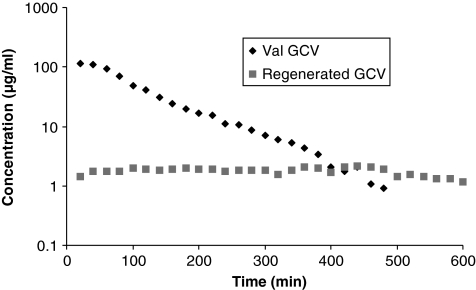

Vitreal pharmacokinetics of GCV and dipeptide prodrugs were studied in conscious rabbit ocular microdialysis model. Vitreal concentration–time profile of GCV in a conscious animal is depicted in Fig. 1. Results generated from the noncompartmental analysis of concentration–time profile are tabulated in the Table 1. Results from unconscious or anesthetized animal model published earlier from our laboratory have also been included in this table.16 GCV was administered intravitreally in same manner consistent with our earlier study with unconscious animal microdialysis. From the results it is clear that for GCV, only the area under curve (AUC), volume of distribution at steady state (Vss), and last measured plasma concentration (Clast) are significantly altered in a conscious animal relative to the anesthetized model. Other pharmacokinetic parameters were not altered at a statistical significance of P ≤ 0.05. AUC, Vss, and Clast for the present study were found to be 11.8 ± 0.8 mg · min · mL−1, 2.6 ± 0.2 mL, and 8.1 ± 0.4 μg/mL, respectively. Vitreal concentration–time profiles of other peptide prodrugs of GCV, that is, Val-GCV, Val-Val-GCV, and Gly-Val-GCV, along with their regenerated parent molecule and/or intermediates after intravitreal injection are depicted in the Figs. 2–4. Corresponding data by noncompartmental analysis using Win NonLin are tabulated in Tables 2–4.

FIG. 1.

Vitreous concentration–time profile of ganciclovir (GCV). Mean values are represented (n = 4).

Table 1.

Conscious Animal Vitreous Pharmacokinetic Parameters of Ganciclovir After Intravitreal Administration

| |

Ganciclovir |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Conscious animal | Anesthetized animal | P Value (<0.05) |

| AUC (mg · min · mL−1) | 11.8 ± 0.8 | 33.7 ± 3.5 | a |

| λz (×10−3/min) | 2.3 ± 0.08 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | NS |

| t1/2 (min) | 294.8 ± 10.1 | 364.7 ± 68.4 | NS |

| Vss (mL) | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | a |

| Cl (μL/min) | 6.7 ± 0.4 | 3.1 ± 0.7 | a |

| MRTlast (min) | 204.9 ± 12.1 | 244.1 ± 32 | NS |

| Clast (μg/mL) | 8.1 ± 0.4 | 20.1 ± 2.5 | a |

| Tlast (min) | 600 | 600 | NS |

Represents significant difference at P < 0.05.

Abbreviations: AUC, area under curve; Clast, last measured plasma concentration; MRT, mean residence time; NS, not significant; Vss, volume of distribution at steady state.

FIG. 2.

Vitreous concentration–time profiles of valine-ganciclovir (Val-GCV) and regenerated GCV. Mean values are represented (n = 4).

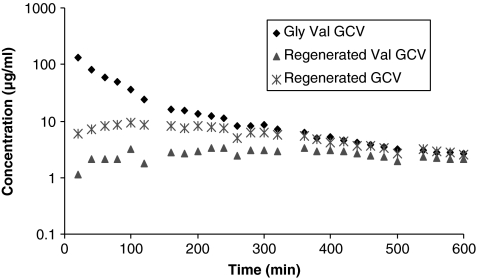

FIG. 4.

Vitreous concentration–time profiles of glycine valine-ganciclovir (Gly-Val-GCV), regenerated GCV, and Val-GCV. Mean values are represented (n = 4).

Table 2.

Conscious Animal Vitreous Pharmacokinetic Parameters of Valine-Ganciclovir and Regenerated Ganciclovir After Intravitreal Administration of Valine-Ganciclovir

| |

Val-GCV |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Conscious animal | Anesthetized animal | P Value (<0.05) |

| AUC (mg · min · mL−1) | 14.1 ± 3.8 | 22.3 ± 4.5 | a |

| λz (×10−3/min) | 10.5 ± 2.0 | 7.6 ± 1.4 | NS |

| t1/2 (min) | 67.5 ± 13.2 | 91.2 ± 14.1 | NS |

| Vss (mL) | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | NS |

| Cl (μL/min) | 13.7 ± 3.2 | 8.3 ± 1.4 | a |

| MRTlast (min) | 91.9 ± 6.2 | 177.3 ± 22.8 | a |

| Clast (μg/mL) | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 4.3 ± 1.8 | a |

| Tlast (min) | 453.3 ± 30.5 | 600 | a |

| Regenerated GCV from Val-GCV | |||

| AUC (mg · min · mL−1) | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 3.1 ± 0.8 | a |

| Cmax (μg/mL) | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 5.2 ± 1.3 | a |

| Tmax (min) | 240 ± 190.8 | 340.3 ± 68.2 | NS |

| MRTlast (min) | 298.1 ± 7.7 | 331 ± 45 | NS |

Represents significant difference at P < 0.05.

Abbreviations: AUC, area under curve; Clast, last measured plasma concentration; GCV, ganciclovir; MRT, mean residence time; NS, not significant; Val, valine; Vss, volume of distribution at steady state.

Table 4.

Conscious Animal Vitreous Pharmacokinetic Parameters of Glycine-Valine-Ganciclovir and Regenerated Valine-GCV and Ganciclovir After Intravitreal Administration of Glycine-Valine-Ganciclovir

| |

Gly-Val-GCV |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Conscious animal | Anesthetized animal | P Value (<0.05) |

| AUC (mg · min · mL−1) | 13.7 ± 3.5 | 50.1 ± 8.6 | a |

| λz (×10−3/min) | 4.6 ± 1.0 | 4.1 ± 0.7 | NS |

| t1/2 (min) | 155.9 ± 37.0 | 169.1 ± 24.7 | NS |

| Vss (mL) | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | NS |

| Cl (μL/min) | 15.3 ± 3.7 | 5.1 ± 1.5 | a |

| MRTlast (min) | 103.3 ± 11.9 | 208.5 ± 32.6 | a |

| Clast (μg/mL) | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 20.1 ± 5.2 | a |

| Tlast (min) | 600 | 600 | NS |

| Regenerated Val-GCV from Gly-Val-GCV | |||

| AUC (mg · min · mL−1) | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | NS |

| Cmax (μg/mL) | 4.0 ± 1.8 | 2.8 ± 0.9 | NS |

| Tmax (min) | 186.7 ± 150.1 | 180 ± 58 | NS |

| MRTlast (min) | 300.4 ± 26.4 | 307 ± 26 | NS |

| Regenerated GCV from Gly-Val-GCV | |||

| AUC (mg · min · mL−1) | 3.4 ± 0.7 | 2.6 ± 0.8 | NS |

| Cmax (μg/mL) | 9.7 ± 2.7 | 3.1 ± 1.2 | a |

| Tmax (min) | 93.3 ± 30.5 | 260 ± 86 | a |

| MRTlast (min) | 248.1 ± 25.7 | 343.8 ± 53 | a |

Represents significant differences at P < 0.05.

Abbreviations: AUC, area under curve; Clast, last measured plasma concentration; GCV, ganciclovir; Gly, glycine; MRT, mean residence time; NS, not significant; Val, valine; Vss, volume of distribution at steady state.

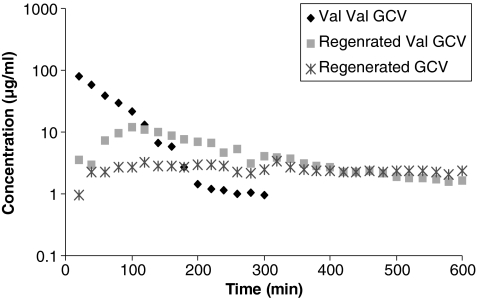

FIG. 3.

Vitreous concentration–time profiles of valine-valine-ganciclovir (Val-Val-GCV), regenerated GCV, and Val-GCV. Mean values are represented (n = 4).

Table 3.

Conscious Animal Vitreous Pharmacokinetic Parameters of Valine-Valine-Ganciclovir and Regenerated Valine-Ganciclovir and Ganciclovir After Intravitreal Administration of Valine-Valine-Ganciclovir

| |

Val-Val-GCV |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Conscious animal | Anesthetized animal | P Value (<0.05) |

| AUC (mg · min · mL−1) | 6.3 ± 0.3 | 29.4 ± 3.2 | a |

| λz (×10−3/min) | 17.4 ± 6.9 | 10.1 ± 2.2 | NS |

| t1/2 (min) | 44.8 ± 19.2 | 68.6 ± 12.3 | NS |

| Vss (mL) | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | a |

| Cl (μL/min) | 35.3 ± 1.8 | 8.9 ± 1.8 | a |

| MRTlast (min) | 50.5 ± 6.4 | 138.4 ± 25.6 | a |

| Clast (μg/mL) | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 7.2 ± 1.1 | a |

| Tlast (min) | 293.3 ± 11.5 | 600 | a |

| Regenerated Val-GCV from Val-Val-GCV | |||

| AUC (mg · min · mL−1) | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | NS |

| Cmax (μg/mL) | 3.6 ± 1.9 | 3.9 ± 1.6 | NS |

| Tmax (min) | 120 ± 105.8 | 460 ± 105 | a |

| MRTlast (min) | 304.5 ± 15.3 | 333 ± 28 | NS |

| Regenerated GCV from Val-Val-GCV | |||

| AUC (mg · min · mL−1) | 2.7 ± 1.0 | 3.5 ± 1.2 | NS |

| Cmax (μg/mL) | 12.5 ± 7.2 | 6.3 ± 1.6 | NS |

| Tmax (min) | 140 ± 69.3 | 420 ± 96 | a |

| MRTlast (min) | 231.8 ± 64.6 | 349 ± 48 | a |

Represents significant difference at P < 0.05.

Abbreviations: AUC, area under curve; Clast, last measured plasma concentration; GCV, ganciclovir; MRT, mean residence time; NS, not significant; Val, valine; Vss, volume of distribution at steady state.

Vitreal elimination half-lives of the GCV prodrugs, that is, Val-GCV, Val-Val-GCV, and Gly-Val-GCV, were 67.5 ± 13.2, 44.8 ± 19.2, and 155.9 ± 37.0 min, respectively. AUC of Val-Val-GCV (6.3 ± 0.3 mg · min · mL−1) after intravitreal administration was observed to be lower than the AUC values obtained from GCV, Val-GCV, and Gly-Val-GCV. Vss for GCV, Val-GCV, Val-Val-GCV, and Gly-Val-GCV were 2.3 ± 0.08, 1.3 ± 0.3, 1.9 ± 0.2, and 2.1 ± 0.6 mL, respectively. Figures 2–4 also show concentration–time profiles of regenerated GCV, which illustrate that sustained vitreal GCV levels are maintained after intravitreal administration of all 3 prodrugs. Similarly sustained regenerated levels of Val-GCV were also observed after administration of the dipeptide monoester GCV prodrugs.

Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to compare vitreal pharmacokinetics in rabbits with or without the influence of anesthesia. The anesthetized animal data for GCV and dipeptide prodrugs of GCV have been previously published from our laboratory.16 Effect of anesthesia and a comparison between conscious versus unconscious animal microdialysis model has been studied earlier with model drug compounds that were stable in vitreous humor.17,23 No study has been performed so far to compare the effect of anesthesia on a prodrug that can potentially be enzymatically hydrolyzed in vitreous humor. This study is highly significant as it can delineate the effect of anesthesia on vitreal pharmacokinetics of prodrugs along with their metabolites in the vitreous humor.

Ocular microdialysis is a valuable technique to study ocular pharmacokinetics. It significantly reduces the number of animals to generate a complete pharmacokinetic profile. Moreover, conscious animal model enables design cross over where the same animal can serve as a control. However, probe implantation may lead to trauma and tissue injury, which could ultimately lead to alteration in drug disposition. The eye is a specialized organ that provides a very small physiological sampling compartment for pharmacokinetic studies. Thus, it is imperative to allow the animal to recover from trauma, which otherwise can result in erroneous findings. Previous studies have also shown that vitreal protein concentrations are elevated by almost 2.5-fold for about 8 h after the probe implantation.17

No studies were conducted previously to evaluate the change in pharmacokinetic profiles of prodrugs that can be absorbed and eliminated by carrier-mediated uptake processes on the retina and other ocular tissues. Such prodrugs can also revert back to parent drug upon various enzymatic and chemical hydrolytic processes.

Earlier studies suggested that various physiological processes, including respiratory and heart rates, are influenced under anesthesia. In fact, it may cause a suppressive effect on such processes, which may lead to slower blood flow and fluid exchange. Although diffusion mainly governs the distribution of a compound in the vitreous, convective forces may also play an important role in this process. Such forces are developed due to the pressure differences between the anterior part of the eye and the retinal surface.31 Thus, any change in the pressure gradient that alters convective forces in turn could affect the distribution of a compound. Previous studies have also postulated that combination of ketamine and xylazine employed as anesthetic in unconscious model has been shown to alter the IOP, which thus might alter the distribution of the drugs and prodrugs. In addition, anesthesia can also slow down any tissue uptake processes involved in the distribution of drugs and prodrugs, thereby leading to higher concentrations in the vitreous chamber. These physiologic changes are probably the reasons why anesthesia might have lead to higher steady state levels in contrast to the conscious animal experiment. In the current study the IOP in the probe-implanted eye would have been normal, assuming complete recovery of animals. In such normotensive eyes 50 μL intravitreal injection may have transiently increased the IOP resulting in drug loss through the needle hole in the sclera. This process may have contributed in part to the lower AUCs obtained in the conscious animals in relative to anesthetized ones.

Conscious animal data presented in this article suggest a decrease in the exposure levels of prodrugs; however, no effects were observed on the elimination rate from the vitreous. It was also noted that vitreal half-lives resulted from this study are comparable to the unconscious animal study published earlier.16 Other pharmacokinetic parameters that were found to be significantly altered in case of conscious animals include Clast and MRTlast. Regenerated AUCs of GCV and Val-GCV in the vitreous humor were found to be unaltered relative to anesthetized model. Even though the AUCs of prodrug administered intravitreally are found to be significantly less, the AUCs of regenerated parent drug (GCV) and intermediate (Val-GCV) are similar to unconscious model, which suggests that more prodrug is probably enzymatically cleaved in conscious animal, thereby maintaining steady concentrations in the vitreous.

Conclusions

Conscious animal microdialysis was performed to delineate any effect of anesthesia on the vitreal pharmacokinetics of various peptide prodrugs of GCV. Results revealed a lowering in exposure levels of drug and prodrug in conscious animals, although vitreal half-lives remained almost the same. The technique is suitable when a new drug molecule is to be tested or when the results from preclinical studies are designed to guide clinical studies. Also, drugs having long vitreal half-lives should be studied in a conscious animal model.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R01 EY 09171-16 and R01 EY 10659-12.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Pepose J.S. Holland G.N. Nestor M.S. Cochran A.J. Foos R.Y. Acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Pathogenic mechanisms of ocular disease. Ophthalmology. 1985;4:472–484. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(85)34008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloom J.N. Palestine A.G. The diagnosis of cytomegalovirus retinitis. Ann. Intern. Med. 1988;12:963–969. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-109-12-963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cunningham E.T., Jr. Margolis T.P. Ocular manifestations of HIV infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998;4:236–244. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807233390406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arruda R.F. Muccioli C. Belfort R., Jr. [Ophthalmological findings in HIV infected patients in the post-HAART (Highly Active Anti-retroviral Therapy) era, compared to the pre-HAART era] Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2004;2:148–152. doi: 10.1590/s0104-42302004000200029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kempen J.H. Jabs D.A. Wilson L.A. Dunn J.P. West S.K. Tonascia J.A. Risk of vision loss in patients with cytomegalovirus retinitis and the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2003;4:466–476. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.4.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jabs D.A. Holbrook J.T. Van Natta M.L. Clark R. Jacobson M.A. Kempen J.H. Murphy R.L. Risk factors for mortality in patients with AIDS in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Ophthalmology. 2005;5:771–779. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crum N.F. Blade K.A. Cytomegalovirus retinitis after immune reconstitution. AIDS Read. 2005;4:186–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freeman W.R. Lerner C.W. Mines J.A. Lash R.S. Nadel A.J. Starr M.B. Tapper M.L. A prospective study of the ophthalmologic findings in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1984;2:133–142. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bodaghi B. Slobbe-van Drunen M.E. Topilko A. Perret E. Vossen R.C. van Dam-Mieras M.C. Zipeto D. Virelizier J.L. LeHoang P. Bruggeman C.A. Michelson S. Entry of human cytomegalovirus into retinal pigment epithelial and endothelial cells by endocytosis. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1999;11:2598–2607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bodaghi B. Michelson S. Cytomegalovirus: virological facts for clinicians. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 1999;7:133–137. doi: 10.1076/ocii.7.3.133.3998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burd E.M. Pulido J.S. Puro D.G. O'Brien W.J. Replication of human cytomegalovirus in human retinal glial cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1996;10:1957–1966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rao N.A. Zhang J. Ishimoto S. Role of retinal vascular endothelial cells in development of CMV retinitis. Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc. 1998;23:124–126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magone M.T. Nussenblatt R.B. Whitcup S.M. Elevation of laser flare photometry in patients with cytomegalovirus retinitis and AIDS. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1997;2:190–198. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70783-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nussenblatt R.B. Lane H.C. Human immunodeficiency virus disease: changing patterns of intraocular inflammation. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1998;3:374–382. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)80149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macha S. Duvvuri S. Mitra A.K. Ocular disposition of novel lipophilic diester prodrugs of ganciclovir following intravitreal administration using microdialysis. Curr. Eye Res. 2004;2:77–84. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.28.2.77.26233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Majumdar S. Kansara V. Mitra A.K. Vitreal pharmacokinetics of dipeptide monoester prodrugs of ganciclovir. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006;4:231–241. doi: 10.1089/jop.2006.22.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dias C.S. Mitra A.K. Posterior segment ocular pharmacokinetics using microdialysis in a conscious rabbit model. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003;1:300–305. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stempels N. Tassignon M.J. Sarre S. A removable ocular microdialysis system for measuring vitreous biogenic amines. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 1993;11:651–655. doi: 10.1007/BF00921960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes P.M. Krishnamoorthy R. Mitra A.K. Vitreous disposition of two acycloguanosine antivirals in the albino and pigmented rabbit models: a novel ocular microdialysis technique. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 1996;2:209–224. doi: 10.1089/jop.1996.12.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macha S. Mitra A.K. Ocular pharmacokinetics in rabbits using a novel dual probe microdialysis technique. Exp. Eye Res. 2001;3:289–299. doi: 10.1006/exer.2000.0953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waga J. Ehinger B. Intravitreal concentrations of some drugs administered with microdialysis. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 1997;1:36–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.1997.tb00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gunnarson G. Jakobsson A.K. Hamberger A. Sjostrand J. Free amino acids in the pre-retinal vitreous space. Effect of high potassium and nipecotic acid. Exp. Eye Res. 1987;2:235–244. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(87)80008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anand B.S. Atluri H. Mitra A.K. Validation of an ocular microdialysis technique in rabbits with permanently implanted vitreous probes: systemic and intravitreal pharmacokinetics of fluorescein. Int. J. Pharm. 2004;281:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waga J. Nilsson-Ehle I. Ljungberg B. Skarin A. Stahle L. Ehinger B. Microdialysis for pharmacokinetic studies of ceftazidime in rabbit vitreous. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 1999;5:455–463. doi: 10.1089/jop.1999.15.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waga J. Ohta A. Ehinger B. Intraocular microdialysis with permanently implanted probes in rabbit. Acta Ophthalmol. (Copenh). 1991;69:618–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1991.tb04849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rittenhouse K.D. Peiffer R.L., Jr. Pollack G.M. Microdialysis evaluation of the ocular pharmacokinetics of propranolol in the conscious rabbit. Pharm. Res. 1999;5:736–742. doi: 10.1023/a:1018884826943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rittenhouse K.D. Peiffer R.L., Jr. Pollack G.M. Evaluation of microdialysis sampling of aqueous humor for in vivo models of ocular absorption and disposition. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 1998;6:951–959. doi: 10.1016/s0731-7085(97)00060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lipman N.S. Phillips P.A. Newcomer C.E. Reversal of ketamine/xylazine anesthesia in the rabbit with yohimbine. Lab. Anim. Sci. 1987;4:474–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jia L. Cepurna W.O. Johnson E.C. Morrison J.C. Effect of general anesthetics on IOP in rats with experimental aqueous outflow obstruction. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000;41:3415–3419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Majumdar S. Nashed Y.E. Patel K. Jain R. Itahashi M. Neumann D.M. Hill J.M. Mitra A.K. Dipeptide monoester ganciclovir prodrugs for treating HSV-1-induced corneal epithelial and stromal keratitis: in vitro and in vivo evaluations. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005;6:463–474. doi: 10.1089/jop.2005.21.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu J. Heys J.J. Barocas V.H. Randolph T.W. Permeability and diffusion in vitreous humor: implications for drug delivery. Pharm. Res. 2000;6:664–669. doi: 10.1023/a:1007517912927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]