Abstract

The structure determination of complex RNA molecules such as ribozymes, riboswitches and aptamers by X-ray crystallography hinges on the preparation of well-ordered crystals. Success usually results from molecular engineering to facilitate crystallization. An approach that has resulted in ten new RNA structures in the past decade is the use of the U1A crystallization module. In this approach, the cognate site for the U1A spliceosomal protein is introduced into a functionally dispensable location in the RNA of interest, and the RNA is cocrystallized with the basic RNA binding protein. In addition to facilitating crystallization, the presence of U1A can be useful for de novo phase determination. In this paper, some general considerations for the use of this approach to RNA crystallization are presented, and specifics of the application of the U1A module to the crystallization of the hairpin ribozyme and the tetracycline aptamer are reviewed.

Keywords: X-ray crystallography, ribozyme, riboswitch, aptamer, RNA-binding protein, molecular engineering

1. Introduction

1.1 X-ray crystallography of RNA

X-ray crystallography produces detailed descriptions of the three-dimensional structures of biological RNAs and RNA-protein complexes (RNPs). Compared to the results of most other biochemical or biophysical experiments, a crystal structure at medium to high resolution is vastly more rich in information, providing the three Cartesian coordinates, the occupancy and the B-factor for most non-hydrogen atoms in a macromolecule. For instance, the 1.7 Å resolution structure of the glmS ribozyme consists of 3276 RNA, water, ion, and ligand atoms; thus, this one crystallographic structure resulted in the experimental determination of over 16,000 parameters (1). Not surprising for an experiment this powerful, X-ray crystallography is an intrinsically complex method [see, e.g. (2)]. In order to have its crystal structure solved, an RNA needs to be synthesized, purified, folded, crystallized, and the crystals cryopreserved. At this point, crystallography proper can commence, and diffraction data collection, phase determination, model building, crystallographic refinement, and structure validation and analysis may be carried out, if each successive step is successful. The preparation of well-ordered single crystals is usually the rate-limiting step in the determination of the three-dimensional structure of RNAs by X-ray crystallography. Of the many methodological advances made in RNA crystallization since the pioneering structure determinations of tRNA in the 1970s (3, 4), perhaps the most important has been the ability to prepare RNA molecules that have been engineered to increase their “crystallizability”. This paper reviews one approach to RNA engineering for crystallization that has been particularly successful in the past decade.

1.2 Engineering RNA for crystallization

Although some RNAs and RNPs, such as yeast tRNAPhe and ribosomes from certain bacteria and archaea can produce high-quality crystals without modification, most RNAs and RNPs need to be engineered to varying extents to facilitate crystallization. Conceptually, the simplest form of engineering of an RNA is the definition of its minimal 5′ and 3′ boundaries. Some RNAs such as tRNAs and self-splicing introns have natural 5′ and 3′ boundaries that result from precise biochemical processing. Other RNAs of biological interest are, instead, functional domains embedded within larger RNAs. In order to subject such functional RNAs to crystallization, it is useful to define the minimal construct length that supports their biochemical function. Minimization results in definition of the structural domain (i.e. the autonomously folding RNA unit) that gives rise to the biochemical function of interest. After 5′ and 3′ domain termini have been defined for an RNA of interest, it may be found that additional internal sequence elements are poorly ordered, functionally dispensable, or both. In such cases, it may be possible to delete these elements to produce RNA constructs that are more stable and conformationally homogeneous, while retaining the biochemical activity of interest. Alternatively, instead of deleting such functionally dispensable elements, the experimenter can replace them with independently folding RNA sequences intended to facilitate crystallization, that is, crystallization modules.

2. The U1A crystallization module

2.1 Rationale for crystallization modules

Crystallization modules were invented to overcome the difficulty in obtaining well-ordered crystals of many RNAs, even when they have been prepared in covalently and conformationally homogeneous form (5). The dominant feature of the molecular surface of a folded RNA is the regular array of negatively charged phosphates. Because of this regular and poorly differentiated molecular surface, successive RNA molecules may pack in subtly different registers as they accrete to form a crystal, leading to disorder or cessation of crystal growth through the accumulation of crystal defects. Therefore, it was hypothesized that introduction of a chemically differentiated surface, such as those provided by RNA tertiary interactions (6) or by RNA binding proteins (7), may help position molecules in a regular register, and hence facilitate the growth of well-ordered crystals. This strategy was successfully employed by engineering the cognate binding site for the U1A protein into a functionally dispensable stem-loop of the hepatitits delta virus (HDV) ribozyme, binding the engineered RNA to the RNA-binding domain (RBD) of the U1A protein, and subjecting the resulting RNP to cocrystallization. A number of constructs were screened, and eventually high quality crystals were obtained for one of them. The resulting 2.3 Å resolution structure provided the first detailed view of a solvent-occluded ribozyme active site, and immediately suggested a catalytic function for a conserved nucleobase with a perturbed pKa (8).

2.2 Advantages of the U1A protein

The U1A protein was chosen for use as part of a crystallization module for several reasons. First, it had previously been extensively characterized structurally. U1A is one of the protein components of the spliceosomal U1 small nuclear RNP (snRNP). It is the prototypical member of the RNA recognition motif (RRM) family of RNA-binding proteins, and contains two RRM domains, the first of which is necessary and sufficient for binding to the protein’s cognate site in the stem-loop II (SLII) of U1 snRNA. This RNA-binding domain (henceforth, U1A-RBD) was the first RRM whose structure was solved (9). Second, it binds to its cognate RNA with very high affinity. Filter-binding studies demonstrated an apparent Kd of 2 × 10−11 M for the association of U1A-RBD with the isolated SLII RNA (10). Third, the 1.92 Å resolution structure of U1A-RBD bound to its cognate SLII RNA demonstrated that RNA-protein interactions are confined to the 5′ seven nucleotides of the 10 nt loop of the RNA and the closing base pair of the stem (11). Thus, inserting as few as twelve nucleotides (nt) into a crystallization target RNA may be sufficient to produce a high-affinity U1A binding site. Fourth, the cocrystal structure revealed an RNA-protein interface comprised of both polar and non-polar interactions (e.g., salt bridges and aromatic-aromatic stacking, respectively) (11). Thus, the RNA-protein complex would be expected to be stable in both low and high ionic-strength, enabling it to be used as a crystallization module under a variety of conditions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of crystal properties of RNA structures determined in complex with U1A-RBD

| Name (PDB ID) | Space Group | Unit cell parameters | Resolution | RNA nt (mol)/au | U1A RBD mol/au | Crystallization conditions * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U1A-hairpin II 21-mer (1URN) (11) | P6522 | a = 97.0 Å, c = 255.3 Å | 1.92 Å | 21 (3) | 3 | 1.8 M Ammonium sulfate, 40 mM Tris pH 7.0, 5 mM spermine, 293 K |

| HDV ribozyme (1CX0) (8) | R32 | a = 109.4 Å, c = 190.7 Å | 2.3 Å | 72 (1) | 1 | 12.5 – 14% PEG 2000 MME, 200 – 250 mM LiCl, 100 mM Tris pH 7.0, 4 mM spermine, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM CoHex, 298 K |

| Hairpin ribozyme (1M5O) (12) | C2 | a = 259.4 Å, b = 44.2 Å, c = 102.5 Å, β= 106.3° | 2.2 Å | 113 (2) | 2 | 21% (v/v) MPD, 150 – 190 mM NH4Cl, 20 mM CaCl2, 2 mM NH4VO3, 295 K |

| Azoarcus Group I intron (1U6B) (71) | P4122 | a = 108.5 Å, c = 249.2 Å | 3.1 Å | 222 (1) | 1 | 26% (v/v) MPD, 50 mM cacodylate pH 6.8, 40 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM CoHex, 298 K |

| GlmS ribozyme-riboswitch (2NZ4) (72) | P21 | a = 48.1 Å, b = 234.2 Å, c = 105.0 Å, β = 90.7° | 2.5 Å | 154 (4) | 4 | 11% (w/v) PEG 8000, 9% (v/v) DMSO, 200 mM KCl, 20 mM MgCl2, 20 mM cacodylate pH 6.8, 298 K |

| Flexizyme (3CUL) (48) | C2 | a = 192.2 Å, b = 48.7 Å, c = 90.5 Å, β = 93.5° | 2.8 Å | 92 (2) | 2 | 14.5 – 15% (w/v) PEG 3000, 0.8 – 1.0 M LiCl, 100 mM Mg formate pH 7.0, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CoHex, 1 mM spermine, 295 K |

| Tetracycline aptamer (3EGZ) (43) | P4212 | a = 120.8 Å, c = 55.3 Å | 2.2 Å | 65 (1) | 1 | 12.5 – 15% (w/v) PEG 8000, 50 mM HEPES pH 7.0, 25 mM MgCl2, 0.25 mM spermine, 296 K |

| Class I RNA ligase (3HHN) (64) | P1 | a = 59.6 Å, b = 70.9 Å, c =70.4 Å, α = 100.3°, β= 103.9°, γ= 99.6° | 2.99 Å | 137 (2) | 2 | 22 – 26% (v/v) MPD, 50 mM cacodylate pH 6.0, 40 mM Mg(OAc)2, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM spermine, 293 K |

| c-di-GMP riboswitch (3IWN) (50) | P212121 | a = 31.8 Å, b = 91.0 Å, c = 280.1 Å | 3.2 Å | 93 (2) | 2 | 30% PEG 3350 (w/v), 320 mM NH4(OAc) pH 7.0, 100 mM Tris pH 8.5, 100 mM KCl, 6 mM MgCl2, 303 K |

| c-di-GMP riboswitch (3IRW) (54) | P21 | a = 49.5 Å, b = 45.1 Å, c = 76.6 Å, β= 96.8° | 2.7 Å | 92 (1) | 1 | 22% PEG 550 MME, 300 mM NaCl, 50 mM MES pH 6.0, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM MgSO4, 298 K |

| TPP riboswitch (3K0J) (51) | P21 | a = 52.4 Å, b = 72.0 Å, c =128.6 Å, β= 94.6° | 3.1 Å | 87 (2) | 4 | 20% (v/v) PEG 500 MME, 20% (v/v) MPD, 80 mM Na citrate pH 5.6, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.25 mM spermine, 298 K |

Concentrations of the componets of the macromolecule and reservoir solutions were added; small molecule ligands of riboswitches are not included in the table.

2.3 Success of the U1A module

To date, the structures of ten different RNAs crystallized employing the U1A-RBD/SLII module have been determined in four different laboratories. Table 1 shows that RNAs cocrystallized with U1A-RBD range in size from the original 21 nt SLII to the 222 nt Azoarcus group I intron. The RNAs successfully crystallized comprise naturally occurring catalytic RNAs (the Azoarcus group I intron, the glmS ribozyme-riboswitch, the hairpin ribozyme, and the HDV ribozyme), in vitro evolved ribozymes (the class I RNA ligase, and flexizyme, an aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase), the aptamer domains of two naturally occurring riboswitches (the cyclic diguanylate-responsive c-di-GMP riboswitch and the thiamine pyrophosphate-responsive TPP riboswitch), and an in vitro evolved aptamer and artificial riboswitch (the tetracycline aptamer). Several of these U1A-RNA complexes have been crystallized in multiple functional states [e.g. inhibitor, transition-state mimic, and product complexes of the hairpin ribozyme (12, 13)]; thus, 34 different RNA-U1A cocrystal structures have so far been deposited in the structural database. To illustrate how the U1A crystallization module can be used as part of an RNA structure determination strategy, the next two sections summarize how it was deployed in our laboratory to determine the structures of a natural catalytic RNA and of an in vitro selected aptamer.

3. Crystallization strategy

3.1 The hairpin ribozyme

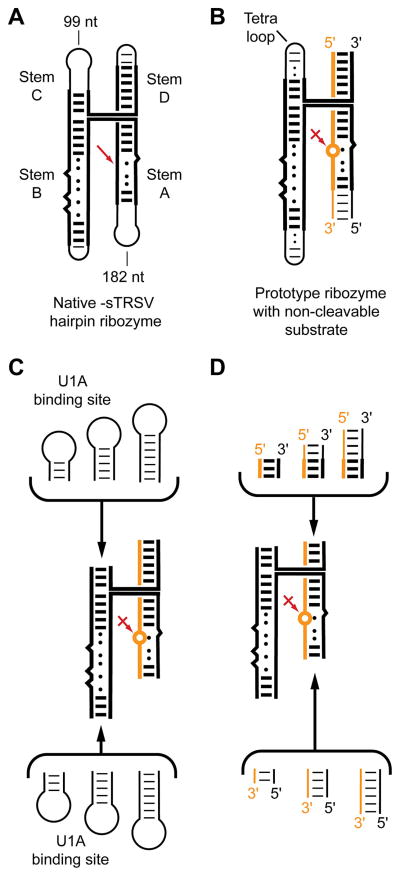

The hairpin ribozyme is one of the best characterized natural ribozymes. It catalyzes the sequence-specific cleavage of RNA through an internal transesterification reaction and functions during the replication of a satellite RNA of a plant viroid [reviewed in ref. (14)]. Its active site results from association of two irregular helices (stems A and B). One of the strands of stem A bears the scissile phosphate. In vitro, these two helices suffice for activity. In its natural form, the two helices are held together by a four-helix junction that facilitates their stable association into the reactive conformation (15) (Figure 1A). Since, in general, it is desirable that macromolecular candidates for crystallization be conformationally homogeneous (16–20), the stable 4-helix junction form of the ribozyme was chosen for crystallization. Because the hairpin ribozyme catalyzes both the cleavage reaction and the reverse ligation reaction (21), an unmodified, all-RNA ribozyme-substrate complex at equilibrium would be covalently heterogenous, being composed of a mixture of ribozymes bound to uncleaved substrate and to the products of cleavage. Therefore, it was decided to replace the substrate strand with an inhibitor at the outset. For this, the cleavage site ribose was replaced with a 2′-methoxyribose, thus blocking the nucleophile that initiates the cleavage reaction, as had been pioneered for studies of the hammerhead ribozyme (22). Introduction of one 2′-methoxyribose in an otherwise unmodified RNA is achieved by chemical synthesis. However, a minimal four-helix junction form of the hairpin ribozyme would be over 100 nt, too long for efficient and cost-effective synthesis. Therefore, the RNA was divided into a short synthetic strand bearing the 2′-methoxy modification at the cleavage site (the inhibitor RNA) and a long in vitro transcript (the ribozyme RNA) which was prepared in homogeneous form with the use of ribozyme domains (23, 24) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Summary of the strategy employed for generating candidate crystallization constructs for the hairpin ribozyme. A. Schematic of the four-helix junction form of the hairpin ribozyme embedded in the negative strand of the circular satellite RNA tobacco ringspot virus. Red arrow denotes site of self-cleavage B. Prototype minimized ribozyme split into an in vitro transcribed strand (black) and a synthetic oligonucleotide (gold) containing a single 2′-methoxy substitution (circle) that blocks the cleavage reaction. C. The U1A binding site was introduced at the distal ends of either stem B (bottom) or stem C. Varying numbers of spacer base pairs separated the U1A binding loop from the core of the RNA. D. Additional molecular diversity was generated by extending the ends of stems A and D by varying the lengths of both the transcript and the synthetic oligonucleotide.

The general strategy for RNA crystallization is derived from the approach developed for the cocrystallization of DNA-protein complexes in the 1980s (25–27). In order to obtain high-quality cocrystals of a given sequence-specific double-helical DNA-binding protein bound to its cognate site, a series of oligonucleotide duplexes is synthesized. Each duplex encompasses the cognate site, which is flanked by varying numbers of base-paired nucleotides. Typically, the duplex DNAs from adjoining crystallographic asymmetric units pack head-to-tail, forming a pseudo-infinite helix that traverses the crystal. The same approach is widely employed for crystallization of RNA duplexes [see, e.g. (28, 29)]. Screening oligonucleotide duplexes of varying length increases the likelihood of finding one that, in complex with the protein of interest, will pack into a well-ordered cocrystal. The basic principle of screening constructs, in addition to crystallization solution conditions, has remained the mainstay of DNA-protein cocrystallization. Similarly, crystallization of RNA and RNPs is, in our experience, most efficiently accomplished by preparing numerous constructs that vary subtly in the periphery of the molecule (keeping the biochemically important core intact), and subjecting each to a relatively modest standard set of crystallization conditions (i.e. a crystallization screen of typically 48 to 196 conditions), rather than employing one RNA or RNP construct and subjecting it to a very large number of candidate crystallization conditions.

We generated a diverse set of hairpin ribozyme crystallization candidates that retain the core 4-helix junction of the wild-type RNA. U1A-RBD requires that its binding site be in a stem-loop. There are four stem termini in this form of the ribozyme that can be closed with loops; choosing to make the substrate/inhibitor strand of the ribozyme as a short synthetic oligonucleotide limits the potential sites into which the U1A binding site could be introduced (as part of the longer in vitro transcribed strand of the crystallization construct) to two. In order to explore “construct space” in addition to varying the location of the U1A binding site, a series of constructs were generated in which the binding site was separated from the core of the ribozyme by varying numbers of “spacer” base pairs (Figure 1C). Each base pair removes the U1A binding site from the ribozyme core by ~2.7 Å (the rise of an A-form base pair), and rotates it by ~33°. We further increased the diversity of the crystallization constructs by systematically varying the length of the distal ends of stems A and D (Figure 1D). Finally, we complexed each RNA construct with either a U1A-RBD of the wild-type human sequence, or a double-mutant U1A-RBD (30) that had been found by Nagai and coworkers to have improved crystallization properties.

After establishing that introduction of the U1A binding site, and complex formation with the protein did not alter the catalytic activity of the ribozyme constructs, they were subjected to standard crystallization screens in complex with an inhibitor oligonucleotide (12). Typically, each construct gave “hits” under several conditions, and there was no discernible preference across constructs for one kind of crystallizing agent over another. This is also clear from the conditions under which the RNAs in Table 1 crystallized. These span from high salt conditions, to polyethylene glycol (PEG) conditions, to salt-PEG mixtures, to organic solvents such as methyl-pentanediol (MPD). Thus, the association between U1A-RBD and its cognate site is stable under a variety of conditions. In our experience, the only commonly used crystallization agents that disrupt the U1A-RNA association are organic (carboxylic) acids at high concentration. Examples of carboxylic acids that are present in widely used crystallization screens are sodium formate at ~4 M (31), and sodium malonate at ~2 M (32, 33). Indeed, in screening crystallization candidates of a different ribozyme engineered to bind to U1A-RBD, we found highly ordered crystals growing under 2.0 – 2.4 M sodium malonate. Gel elecrophoretic analysis of those crystals indicated that they were comprised exclusively of the U1A-RBD protein. Structure determination confirmed this, and also showed several well-ordered malonate molecules bound to the surface of U1A-RBD at sites that are bound by RNA nucleobases in U1A-RNA complexes (34). Thus, it is possible that carboxylic acids disrupt U1A binding to RNA by molecular mimicry.

Initial crystal hits from the different hairpin ribozyme constructs were first characterized by gel electrophoresis to verify that intact RNA was present in them. Then, the crystallization conditions were optimized for each hit to obtain crystals of size sufficient for characterization of their diffraction properties. With a home laboratory X-ray source, minimum dimension of ~100 μm in each dimension would be desirable, especially if crystals are being tested by capillary mounting. With access to synchrotron radiation, smaller crystals may suffice to establish if a crystal form is well-ordered enough to warrant further optimization. Eventually, hairpin ribozyme crystals were obtained that diffract X-rays to at least 2.4 Å resolution (12). Because these crystals tended to grow as clusters, structure determination required that single crystals be grown by macroseeding (35). Ultimately, the same crystal form was employed to determine the structures of a transition state mimic and of the product complex by replacing the chemically synthesized inhibitor strand with the corresponding oligonucleotides (13).

3.2 The tetracycline aptamer

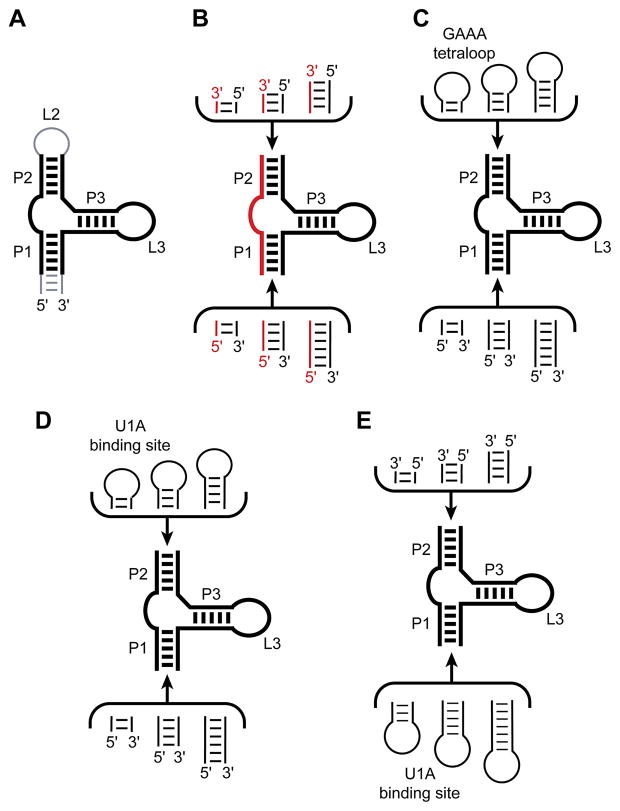

The tetracycline aptamer is an artificially evolved RNA that binds the antibiotic with high affinity and specificity (36). It is the in vitro evolved aptamer with the highest known affinity (Kd ~ 0.8 nM) for its small molecule ligand (37). This RNA has been successfully employed to regulate gene expression in vivo in response to tetracycline, that is, to function as a riboswitch (38, 39). In its originally described form, the tetracycline aptamer consists of three helices (paired regions P1, P2 and P3), with P2 and P3 closed by the corresponding loops L2 and L3 (Figure 2A) (36). Biochemical characterization had demonstrated that while L2 is functionally dispensable, L3 is critical for tetracycline binding, and probably participates directly in forming the small molecule binding site. In addition, these experiments suggested that the formally single-stranded regions joining P1 with P2 (J1/2) and P2 with P3 (J2/3) also form part of the tetracycline binding site. Deletion analysis also demonstrated that the distal end of P1 is functionally dispensable (36, 40).

Figure 2.

Summary of the strategy employed for generating candidate crystallization constructs for the tetracycline aptamer. A. The minimal tetracycline aptamer (black lines) is bracketed by a functionally dispensable loop L2 and distal portion of P1 (gray). B. A series of crystallization constructs was generated by splitting the RNA into a short synthetic oligonucleotide (red) and a longer in vitro transcript (black). Diversity was generated by varying the length of the distal ends of P1 and P2. C. Another series of constructs contained a GAAA tetraloop in place of L2. Diversity obtained from varying the number of spacer base pairs connecting the tetraloop to P2, and by varying the length of the distal end of P1. D. One set of crystallization constructs contained the U1A binding site at the distal end of P2. Diversity was generated in the same manner as in (C). E. Another set of crystallization constructs was circularly permuted relative to the parental sequence (A), by introducing the U1A binding site at the distal end of P1.

We initially attempted crystallization of the tetracycline aptamer without employing the U1A crystallization module by making two types of RNA constructs based on the results of the biochemical analyses summarized above. First, we deleted the functionally dispensable loop L2. This resulted in an RNA molecule comprised of two separate polynucleotide chains, each of which is short enough to synthesize chemically in good yield and at reasonable cost. We generated diversity by synthesizing oligonucleotides with varying numbers of nucleotides at either end, thereby extending the distal ends of P1 and P2 (Figure 2B). In addition, the various oligonucleotides could be “mixed-and-matched” to generate aptamer constructs with overhanging ends at either or both the ends of P1 and P2. Such overhanging (“sticky”) ends are routinely employed in the crystallization of DNA-protein and RNA-protein complexes to optimize the packing of duplex ends in crystals (5, 26, 41). For crystallization, the full aptamer was assembled by annealing two oligonucleotides, then the RNA was complexed with 7-chlorotetracycline (which is bound more tightly than tetracycline by the aptamer), and subjected to crystallization screens. Although some of these two-piece constructs produced crystals, none of them diffracted X-rays to high enough resolution. Second, we generated constructs in which the L2 loop was replaced with a tetraloop of sequence GAAA. This particular sequence is widely employed by natural RNAs to make intramolecular (tertiary) contacts, and has also been observed to form intermolecular contacts in some instances [e.g. ref. (42)]. We generated diversity by varying the number of spacer base pairs separating the GAAA tetraloop from the core of the aptamer, and also by varying the length of the distal portion of P1 (Figure 2C). This series of constructs also failed to produce well-ordered crystals. We therefore turned to the U1A crystallization module.

In a first series of crystallization constructs, we replaced the functionally dispensable loop L2 with the U1A binding site, and generated diversity by varying the number of spacer nucleotides separating it from the core of the aptamer. We also increased diversity by varying the length of the distal end of P1 (Figure 2D). Cocrystallization of these constructs with 7-chlorotetracycline and U1A produced numerous crystalline hits, but none that diffracted X-rays well. The next series of crystallization constructs were generated by circularly permuting the RNA. This was achieved by placing the U1A binding site on the distal end of P1, and removing L2. In these circularly permuted constructs, the RNA is transcribed starting and ending on the distal end of P2. As before, diversity was generated by varying the number of spacer nucleotides separating the U1A binding site from the core of the aptamer, and by varying the number of nucleotides on the distal end of P2 (Figure 2E). After establishing that circular permutation did not affect the affinity of the aptamer for its ligand, the RNAs were subjected to crystallization trials. One of the circularly permuted constructs in complex with U1A-RBD generated crystals suitable for structure determination that diffracted X-rays beyond 2.2 Å resolution (43).

4. The U1A module in phase determination

In addition to facilitating crystallization, the U1A module has also been useful in obtaining phase information with which to solve crystal structures. U1A-RBD lacks cysteines, but Nagai and coworkers introduced single-cysteine mutations in a number of locations, and derivatized the resulting crystals with mercury compounds to determine the original structure of the free U1A-RBD by multiple isomorphous replacement (MIR) (9). If recombinant U1A-RBD is expressed in Escherichia coli, it is straightforward to replace its methionine residues with selenomethionines (44). In addition to the initiation methionine (which is efficiently cleaved in vivo), U1A RBD contains four methionine residues, one of which is near the C-terminus of the protein and is often poorly ordered. The remaining three methionine residues are well-ordered (if the protein itself is), and are suitable for phase determination by the multiwavelength anomalous dispersion (MAD) method if substituted with selenomethionine (7, 8).

In the case of the hairpin ribozyme discussed above, cocrystals containing selenomethionyl U1A-RBD were readily grown under crystallization conditions very similar to those under which cocrystals with methionine-containing U1A-RBD were prepared. Iterative seeding (45) produced crystals that were suitable for structure determination by selenium MAD. In addition, we grew crystals using synthetic inhibitor strands in which different uridine residues were replaced with 5-iodouridine or 5-bromouridine. While these halogen atoms were not used for phase determination, they were useful in establishing unambiguously the sequence register of the RNA during crystallographic model building (12).

Cocrystalization of the tetracycline aptamer with selenomethionyl, rather than unsubstituted (i.e. methionyl), U1A-RBD had the effect of improving the diffraction limit of the crystals. Methionyl U1A-RBD cocrystals diffracted synchrotron radiation to ~3.0 Å resolution. Cocrystals with selenomethionyl U1A-RBD grew under identical conditions, and had comparable symmetry, unit cell dimensions and growth habit (crystal morphology), but diffracted X-rays to better than 2.1 Å resolution. Although radiation damage ultimately limited the resolution of the data to 2.2 Å (43), the selenomethionine crystals were clearly better ordered, and were employed for structure determination by selenium MAD.

Selenomethionine substitution often increases the stability of proteins because selenium is larger than sulfur. Thus, if methionine residues are buried in the interior of a protein, the hydrophobic drive of protein folding will be larger if its methionines are substituted with selenomethionine (44). In the case of U1A-RBD, one methionine, Met51, is partially solvent exposed, and contacts one of the riboses of its cognate binding site. Thus, substitution with selenomethionine is likely not only to stabilize the protein, but also to subtly alter the protein-RNA interaction. A more dramatic example of the effect of selenomethionyl substitution in U1A was encountered during crystallization of the HDV ribozyme. In that case, cocrystallization with normal methionine produced tetragonal crystals that diffracted synchrotron X-rays to ~2.9 Å resolution. When the same RNA construct was complexed with selenomethionyl U1A-RBD, crystals were no longer forthcoming under the same crystallization conditions. Further screening of crystallization conditions resulted in crystals of the selenomethionyl U1A-RBD bound to the HDV ribozyme, under different conditions. These crystals were rhombohedral and diffracted X-rays to ~2.3 Å resolution (7).

Recently, the U1A crystallization module has found use in structure determination through the molecular replacement (MR) method. Robertson and Scott pioneered the application of MR for the determination of new RNA structures (46–50) (see article by Robertson and Scott in this issue of Methods). In this approach, small RNA fragments (typically duplexes of arbitrary sequence) are employed to find partial MR solutions. This method has been successfully employed for the structure determination of two different RNAs crystallized with the help of the U1A module. In the case of flexizyme, MAD phasing with selenomethionine U1A-RBD produced only poor phases, due to radiation damage. A MR solution was obtained by using the U1A-RBD bound to its cognate site, as well as two other RNA fragments known to be present in the structure (a tRNA minihelix and a short stem capped by a GAAA tetraloop) as search models. Combination of the MR-derived phases with the MAD phases resulted in readily interpretable electron density maps (48). In the case of the c-di-GMP riboswitch, a MR solution was obtained by using the U1A-RBD bound to its cognate site and short A-form duplexes of arbitrary sequence as initial search models. After these elements were placed, the crystallographic model was built step-wise by iterating model building, simulated annealing refinement, and inspection of new electron density maps (50).

In carrying out molecular replacement, it is reasonable to assume that the U1A-RBD and the engineered RNA will be present in 1:1 stoichiometry. The only exception in Table 1 is the structure of the TPP riboswitch. In this case, two molecules of U1A-RBD were present per RNA. One of the protein molecules engages in conventional binding to its cognate site. The other does not make any specific RNA contacts; nonetheless it is well ordered, and needed to be correctly modeled for successful refinement of the structure (51). Throughout this review, the only U1A binding site discussed has been the SLII site from U1 snRNA. U1A is also known to form a 2:1 complex with an element in its mRNA. While a structure of this complex has been determined (52), it has not been employed as a crystallization module thus far.

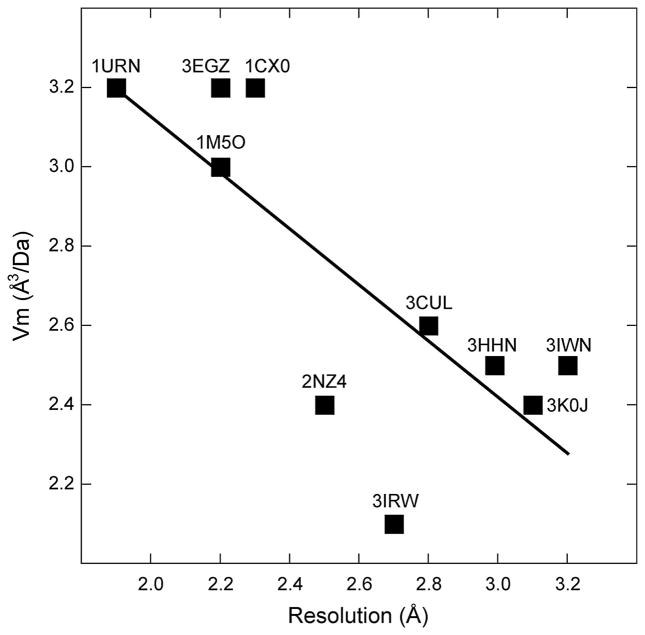

5. Crystal packing

Does the U1A crystallization module function by participating in a specific type of crystal-packing interaction? Each of the ten engineered RNAs in Table 1 crystallized with a unique combination of crystallographic symmetry and unit cell dimensions, so that there are no obvious trends in these properties, except that the representation of space groups roughly mirrors what is seen in the structural database (53). Analysis of crystal density and diffraction limits (Figure 3) does not reveal any clear relationship. The apparent increase in order with increasing solvent content seen in this graph could be indicative of some general property of RNA-U1A cocrystals, although this might be a coincidence given the small number of data points. Detailed molecular analysis shows that the crystal contacts in which the U1A module engages are different in each crystal form. There is no apparent preference in the manner in which the solvent-accessible surface of U1A-RBD contacts symmetry-related protein or RNA moieties. This diversity might be expected, given that the RNAs onto which the module was grafted are all different. Nonetheless, it is clear that even subtle differences between crystallization constructs can result in drastic changes in the arrangement of the RNA-U1A complex in its crystal. This is illustrated by comparison of the two published structures of the c-di-GMP riboswitch.

Figure 3.

Plot of the density of RNA crystals grown employing the U1A crystallization module vs. resolution limit. The Matthews number [Vm, (73)] is plotted as a function of the maximum resolution for all structures in Table 1, except the Azoarcus group I intron, which appears to be an outlier (Vm ~ 4.4). Although the linear regression is based on a small number of data points, it suggests counterintuitively that higher resolution correlates with higher solvent content (R = 0.77).

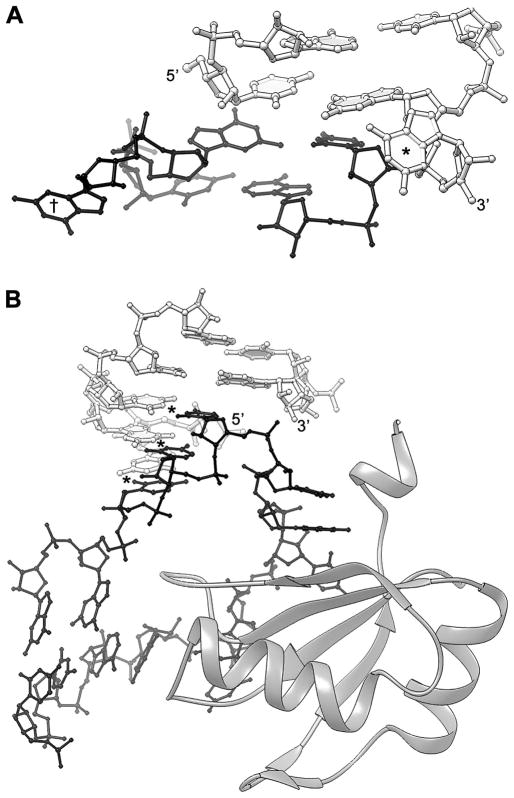

The crystallization constructs employed by Kulshina et al. (50) and Smith et al. (54) have identical core sequences, but differ in two locations. First, the number of spacer base pairs separating the U1A crystallization module from the conserved core of the riboswitch is two for the Kulshina et al. construct and zero for the Smith et al. construct. Second, the number of unpaired nucleotides in the distal end of P1 differs between the two constructs. The RNA employed by Kulsina et al. has no unpaired 5′ nucleotide, and a single unpaired 3′ guanosine, while the RNA of Smith et al. has a trinucleotide of sequence GGU overhanging on the 5′ end of P1 and a 3′ guanosine overhang. This difference in overhanging nucleotides gives rise to dramatically different modes of crystal packing for helix P1. In the crystals of Kulshina et al., the helical ends of adjacent molecules in the crystal stack on each other. The overhanging 3′ guanosine residues of the two molecules are extruded from the helical interface, and project into solvent channel on either side of the pseudo-continuous helix formed by the two adjacent c-di-GMP riboswitch molecules (Figure 4A). In contrast, in the crystals of Smith et al., the 5′ GGU overhang base pairs with the sequence UCC on the 3′ side of the U1A binding site of a symmetry-related molecule (Figure 4B). These nucleotides of the U1A binding site are not contacted by the cognate U1A-RBD, and adopt varying conformations in different structures. For instance, they are disordered in the original U1A-SLII structure (11). One of these nucleotides forms a single base pair with an internal loop of a symmetry-related molecule in the HDV ribozyme structure (8). These nucleotides base pair with a T-loop of a symmetry-related molecule in the flexizyme structure (Figure 5) (48).

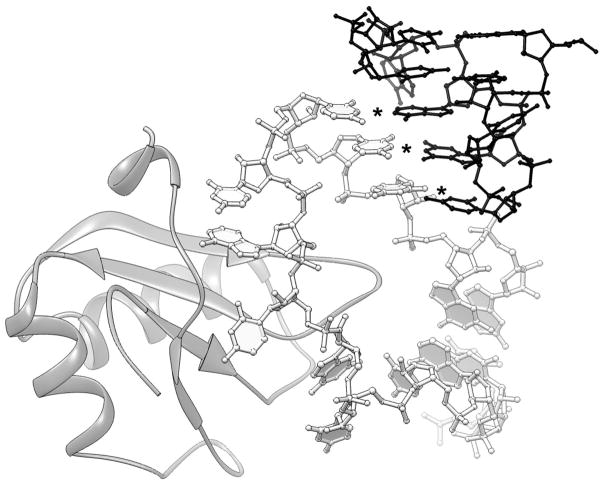

Figure 4.

Comparison of crystal packing of two different constructs of the tfoX c-di-GMP riboswitch from Vibrio cholereae crystallized with the aid of the U1A module. A. Detail of crystal packing of the crystals of Kulshina et al. (50). Here, the distal end of P1a of one RNA molecule (white) stacks on the equivalent helical end of another molecule (black). The 3′ overhanging G of each molecule (* and †) is extruded from the intermolecular helical stack. B. Detail of crystal packing of the crystals of Smith et al. (54). This RNA construct differs from that of (A), inter alia, in having a 3 nt 5′ extension. These nucleotides form three Watson-Crick base pairs (*) with three nucleotides of the U1A binding site (black) of another molecule in the crystal. U1A-RBD is shown as a ribbon figure (74).

Figure 5.

Packing of a T-loop tetraloop against the U1A crystallization module in crystals of the flexizyme (48). The same three nucleotides highlighted in Figure 4B form Watson-Crick base pairs (*) with three nucleotides from the T-loop of a symmetry related molecule (black) in this crystal form.

Although the foregoing discussion emphasizes the manner in which the U1A module packs into crystals, crystallization is a process that involves kinetically controlled nucleation events and thermodynamically controlled crystal growth (55, 56). Thus, the effect of introducing a crystallizaiton module into an RNA is likely complex, and may not necessarily be apparent from examination of the crystal structure. This appears to be the case for the the Azoarcus group I intron, where the crystallization module was required to obtain crystals, but U1A-RBD is poorly ordered.

6. The U1A module vs. naked RNA crystallization

Well-ordered crystals of several RNAs have been obtained both employing the U1A module and with “naked” RNA that has not been engineered to bind to U1A. The latter include the hairpin ribozyme, crystallized as a minimized two-helix construct (57–59); two group I introns from different sources (60, 61); the glmS ribozyme (1, 62, 63); the class I ligase, crystallized with the aid of FABs (64, 65); and the TPP riboswitch (66–68). In all cases, the structures solved with and without the U1A module are very similar in the functional cores of the molecules, confirming that RNA molecules can be engineered for crystallization by modifying peripheral elements without perturbing their core structure and function. Recently, the structure of the U1 snRNP was determined at 5.5 Å resolution (69). Ironically, crystallization of the U1 snRNP required that the U1A-binding site on SLII be replaced with a kissing loop motif, and the U1A protein omitted from in vitro reconstitution of the particle.

An unintended benefit of the U1A module in the crystallization of the glmS ribozyme resulted from a serendipitous experimental mishap. The RNA was engineered to contain the U1A binding site in the conventional manner, and cocrystallized with U1A-RBD. For one specific RNA construct, crystals appeared rapidly, but proved to be poorly ordered. However, examination of the same crystallization experiment approximately a month later revealed new crystals of a different morphology. These were found to diffract X-rays to better than 3 Å resolution. Analysis of dissolved crystals showed that the U1A binding loop had suffered scission (presumably as a result of a contaminating nuclease). Since U1A-RBD would not be expected to bind to an RNA with such a split binding site, further crystallization experiments were carried out in the absence of U1A-RBD with a new RNA construct made to contain the cleaved U1A binding site. These were successful. Ultimately, these crystals were subjected to controlled dehydration and diffracted X-rays to 1.7 Å resolution (1, 70).

7. Concluding remarks

In the decade since its invention, the U1A crystallization module has established itself as a versatile strategy for RNA crystallization. There are usually no shortcuts to high-quality RNA crystals, and there is no single approach that guarantees success. Nonetheless, given its track record, the U1A-RBD should be considered as one of the principal strategies to be employed in attempting to crystallize a complex RNA. The concept of the RNP as a crystallization module will no doubt be extended to other RNA-binding proteins in coming years, increasing the versatility of the toolkit available to the RNA structural biologist.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks K. Nagai (Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge, UK) whose gift of U1A-RBD expression vectors gave impetus to the initial development of the U1A crystallization module, and past and current members of the Ferré-D’Amaré laboratory for their many contributions. Work in the author’s laboratory has been funded by the American Cancer Society, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI), the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the National Institutes of Health (GM63576 and RR15943), the Rita Allen Foundation, and the W.M. Keck Foundation. The author is an Investigator of the HHMI.

Abbreviations

- RNA

ribonucleic acid

- RNP

ribonucleoprotein

- nt

nucleotide

- bp

base pair

- MPD

methylpentanediol

- PEG

polyethyleneglycol

- MIR

multiple isomorphous replacement

- MAD

multiwavelength anomalous dispersion

- MR

molecular replacement

- HDV

hepatitis delta virus

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Klein DJ, Wilkinson SR, Been MD, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. J Mol Biol. 2007;373:178–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drenth J. Principles of protein X-ray crystallography. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim SH, Suddath FL, Quigley GJ, McPherson A, Sussman JL, Wang AHJ, Seeman NC, Rich A. Science. 1974;185:435–40. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4149.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robertus JD, Ladner JE, Finch JT, Rhodes D, Brown RS, Clark BF, Klug A. Nature. 1974;250:546–51. doi: 10.1038/250546a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferré-D’Amaré AR, Doudna JA. In: Current protocols in nucleic acid chemistry. Beaucage SL, Bergstrom DE, Glick GD, Jones RA, editors. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 2000. pp. 7.6.1–7.6.10. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferré-D’Amaré AR, Zhou K, Doudna JA. J Mol Biol. 1998;279:621–31. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferré-D’Amaré AR, Doudna JA. J Mol Biol. 2000;295:541–56. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferré-D’Amaré AR, Zhou K, Doudna JA. Nature. 1998;395:567–74. doi: 10.1038/26912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagai K, Oubridge C, Jessen TH, Li J, Evans PR. Nature. 1990;348:515–20. doi: 10.1038/348515a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall KB, Stump WT. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:4283–90. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.16.4283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oubridge C, Ito N, Evans PR, Teo CH, Nagai K. Nature. 1994;372:432–38. doi: 10.1038/372432a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rupert PB, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Nature. 2001;410:780–86. doi: 10.1038/35071009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rupert PB, Massey AP, Sigurdsson ST, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Science. 2002;298:1421–24. doi: 10.1126/science.1076093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Biopolymers. 2004;73:71–78. doi: 10.1002/bip.10516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murchie AIH, Thomson JB, Walter F, Lilley DMJ. Mol Cell. 1998;1:873–81. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferré-D’Amaré AR, Burley SK. Structure. 1994;2:357–59. 567. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen SL, Ferré-D’Amaré AR, Burley SK, Chait BT. Protein Sci. 1995;4:1088–99. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen SL. Structure. 1996;4:1013–16. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferré-D’Amaré AR, Doudna JA. Methods Mol Biol. 1997;74:371–78. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-389-9:371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferré-D’Amaré AR, Burley SK. Meth Enzymol. 1997;276:157–66. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fedor MJ. Biochemistry. 1999;38:11040–50. doi: 10.1021/bi991069q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scott WG, Finch JT, Klug A. Cell. 1995;81:991–1002. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Price SR, Ito N, Oubridge C, Avis JM, Nagai K. J Mol Biol. 1995;249:398–408. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferré-D’Amaré AR, Doudna JA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:977–78. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.5.977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jordan SR, Whitcombe TV, Berg JM, Pabo CO. Science. 1985;230:1383–85. doi: 10.1126/science.3906896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aggarwal AK. Methods. 1990;1:83–90. doi: 10.1016/S1046-2023(05)80150-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schultz SC, Shields GC, Steitz TA. J Mol Biol. 1990;213:159–66. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Correll CC, Freeborn B, Moore PB, Steitz TA. Cell. 1997;91:705–12. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pitt J, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:3532–40. doi: 10.1021/ja8067325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oubridge C, Ito N, Teo CH, Fearnley I, Nagai K. J Mol Biol. 1995;249:409–23. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jancarik J, Kim SH. J Appl Cryst. 1991;24:409–11. [Google Scholar]

- 32.McPherson A. Protein Sci. 2001;10:418–22. doi: 10.1110/ps.32001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holyoak T, Fenn TD, Wilson MA, Moulin AG, Ringe D, Petsko GA. Acta Crystallogr D. 2003;59:2356–58. doi: 10.1107/s0907444903021784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rupert PB, Xiao H, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Acta Crystallogr D. 2003;59:1521–24. doi: 10.1107/s0907444903011338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rupert PB, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;252:303–11. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-746-7:303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berens C, Thain A, Schroeder R. Bioorg Med Chem. 2001;9:2549–56. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Müller M, Weigand JE, Weichenrieder O, Suess B. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:2607–17. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hanson S, Berthelot K, Fink B, McCarthy JE, Suess B. Mol Microbiol. 2003;49:1627–37. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kotter P, Weigand JE, Meyer B, Entian KD, Suess B. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e120–e20. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hanson S, Bauer G, Fink B, Suess B. RNA. 2005;11:503–11. doi: 10.1261/rna.7251305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Curr Op Struct Biol. 2003;13:49–55. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pley HW, Flaherty KM, McKay DB. Nature. 1994;372:111–13. doi: 10.1038/372111a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xiao H, Edwards TE, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Chem Biol. 2008;15:1125–37. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Doublié S. Meth Enzymol. 1997;276:523–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rupert PB, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;252:303–11. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-746-7:303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robertson MP, Scott WG. Science. 2007;315:1549–53. doi: 10.1126/science.1136231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Robertson MP, Scott WG. Acta Crystallogr D. 2008;64:738–44. doi: 10.1107/S0907444908011578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xiao H, Murakami H, Suga H, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Nature. 2008;454:358–61. doi: 10.1038/nature07033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klein D, Edwards T, Ferré-D’Amaré A. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:343–44. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kulshina N, Baird NJ, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:1212–17. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kulshina N, Edwards TE, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. RNA. 2010;16:186–96. doi: 10.1261/rna.1847310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Varani L, Gunderson SI, Mattaj IW, Kay LE, Neuhaus D, Varani G. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:329–35. doi: 10.1038/74101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chruszcz M, Potrzebowski W, Zimmerman MD, Grabowski M, Zheng H, Lasota P, Minor W. Protein Sci. 2008;17:623–32. doi: 10.1110/ps.073360508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith KD, Lipchock SV, Ames TD, Wang J, Breaker RR, Strobel SA. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:1218–23. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stura EA, Wilson IA. Methods. 1990;1:38–49. [Google Scholar]

- 56.McPherson A. Preparation and analysis of protein crystals. Wiley; New York: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alam S, Grum-Tokars V, Krucinska J, Kundracik ML, Wedekind JE. Biochemistry. 2005;44:14396–408. doi: 10.1021/bi051550i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Salter J, Krucinska J, Alam S, Grum-Tokars V, Wedekind JE. Biochemistry. 2006;45:686–700. doi: 10.1021/bi051887k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Torelli AT, Krucinska J, Wedekind JE. RNA. 2007 doi: 10.1261/rna.510807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Golden BL, Kim H, Chase E. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:82–9. doi: 10.1038/nsmb868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guo F, Gooding AR, Cech TR. Mol Cell. 2004;16:351–62. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Klein DJ, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Science. 2006;313:1752–56. doi: 10.1126/science.1129666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Klein DJ, Been MD, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:14858–59. doi: 10.1021/ja0768441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shechner DM, Grant RA, Bagby SC, Koldobskaya Y, Piccirilli JA, Bartel DP. Science. 2009;326:1271–75. doi: 10.1126/science.1174676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ye JD, Tereshko V, Frederiksen JK, Koide A, Fellouse FA, Sidhu SS, Koide S, Kossiakoff AA, Piccirilli JA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:82–87. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709082105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Edwards TE, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Structure. 2006;14:1459–68. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Serganov A, Polonskaia A, Phan AT, Breaker RR, Patel DJ. Nature. 2006;441:1167–71. doi: 10.1038/nature04740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thore S. Science. 2006;312:1208–11. doi: 10.1126/science.1128451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pomeranz Krummel DA, Oubridge C, Leung AKW, Li J, Nagai K. Nature. 2009;458:475–80. doi: 10.1038/nature07851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Klein DJ, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;540:129–39. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-558-9_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Adams PL, Stahley MR, Kosek AB, Wang J, Strobel SA. Nature. 2004;430:45–50. doi: 10.1038/nature02642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cochrane JC, Lipchock SV, Strobel SA. Chem Biol. 2007;14:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Matthews BW. J Mol Biol. 1968;33:491–97. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Carson M. Meth Enzymol. 1997;277:493–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]