Abstract

This study examines motives for intimate partner violence (IPV) among a community sample of 412 women who used IPV against male partners. A “Motives and Reasons for IPV scale” is proposed, and exploratory factor analyses identified five factors: expression of negative emotions, self-defense, control, jealousy, and tough guise. To our knowledge, the study is the first to investigate the relationship between women’s motives for IPV and their perpetration of physical, psychological, and sexual aggression, as well as coercive control, toward partners. Hierarchical regression analyses revealed participants’ aggression was driven by complex, multiple motives. All five motives were related to a greater frequency of perpetrating IPV. Treatment programs focusing on women’s IPV perpetration should address both defensive and proactive motives.

Keywords: Intimate partner violence, motives, female perpetrators, Motives and Reasons for Intimate Partner Violence scale

Increased rates of arrests of women for domestic violence offenses (Kernsmith, 2005; Swan & Snow, 2002) highlight the importance of understanding the reasons that women, as well as men, use intimate partner violence (IPV) (Stuart, Moore, et al., 2006). To develop effective interventions, researchers and service providers working with individuals who use IPV need to understand what the individuals themselves see as their reasons for committing aggressive behaviors. However, knowledge of these reasons for IPV, particularly for women, is hampered by a lack of empirical data (Hettrich & O’Leary, 2007; Stuart, Moore et al., 2006). The purpose of this study is to examine reasons and motives for IPV among a community sample of women who used IPV against male intimate partners. A “Motives and Reasons for IPV scale” is proposed, and exploratory factor analyses are conducted to identify the factor structure of the scale. The relationships between scale factors and women’s IPV is examined, controlling for victimization the women received from their partners. The study is the first, to our knowledge, to investigate the relationship between a comprehensive measure of women’s reasons and motives for IPV and their perpetration of physical, psychological, and sexual aggression, as well as coercive control, toward their partners.

Women’s Motives for Intimate Partner Violence

Motives are defined as “underlying psychological processes that impel people’s thinking, feeling, and behaving” (Fiske, 2004, p. 14). Motives for aggressive behavior in general have been conceptualized as reactive (responding to a perceived threat, such as defending oneself when attacked) versus proactive (aggression that is initiated with the goal of dominating, controlling, threatening, or bullying someone else) (Dodge & Coie, 1987). Similarly, women’s motivations for aggression against intimate partners have been organized into two types: defensive or reactive motives (i.e., self-protective violence) and active motives, or those that go beyond simply defending oneself and are goal-oriented, such as anger, retaliation, and attempts to control the partner (Swan & Snow, 2006).

The following section provides an overview of research on women’s defensive and active motives and reasons for IPV. While reviewing these research findings, it is helpful to keep in mind that aggressors typically have multiple motives for their behavior (Fiske, 2004). Some motives, such as self-defense and control, may be proximally related to the psychological processes impelling the person’s aggressive behavior at that moment. Other reasons for aggression, such as previous abusive relationships, likely are more distally related. Henceforth, the term “motives” refers to proximal psychological processes that impel behavior, while “reasons” is used as a more general term that refers to motives or to more distal contributors to aggression.

Expression of negative emotions

One of the primary functions of aggression in general, and IPV in particular, is to express strongly felt negative emotions, such as anger and frustration (Fiske, 2004; Kimmel, 2002). Women who were arrested for IPV indicated that showing anger was a motive for their violence 39% of the time (Stuart, Moore et al., 2006); Babcock, Miller, and Siard (2003) found similar results. A study of college women’s IPV found that 24% of participants attributed their violence to ‘uncontrollable anger’ (Makepeace, 1986). In several studies of college women who completed a motives measure and then identified which motive was the “main cause” of their aggression towards partners, “to show anger” was the most frequently identified primary motive (Harned, 2001; Hettrich & O’Leary, 2007;Walley-Jean & Swan, in press).

Self-defense

Women who engage in IPV commonly report using violence to defend themselves from their partners (Babcock et al., 2003). That self-defense is a frequent motive is not surprising given that the majority of women who use IPV also experience violence from their partners (Hamberger & Guse, 2002; Orcutt, Garcia, & Pickett, 2005; Straus & Gelles, 1990; Stuart, Moore et al., 2006; Swan & Snow, 2002; Temple, Weston, & Marshall, 2005). Among a sample of women who used IPV, 75% of participants indicated that self-defense was a motive for their violence; it was the most frequently endorsed motive (Swan & Snow, 2003). Similarly, in Stuart, Moore et al.’s (2006) sample of women who were arrested for IPV, women’s violence was motivated by self-defense 39% of the time.

We expect that women in our sample who report that self-defense is never a motive for their violence may be primary aggressors who commit more violence against partners than they receive. These women likely have other, non-defensive motives for their violence, such as expressing negative emotions or control. They may commit higher levels of aggression, relative to women who do have self-defensive motives for their violence. In contrast, women who score high on the self-defense motive – that is, most of the time when they are aggressive, they are defending themselves - may be primarily victims. In response to their high levels of victimization, these women may commit more aggression than other groups for whom self-defense is not as prominent of a motive.

Thus, we anticipate that the relationship between self-defense motives and women’s perpetration of physical aggression might be curvilinear, with higher aggression being committed by women whose aggression is never motivated by self-defense, and by women whose aggression is very often motivated by self-defense. Women in between these two extremes may use aggression less than the other two groups. These women may be in more mutually aggressive relationships, in which both partners may become aggressive but neither has dominance or control over the other. These relationships may be similar to Johnson’s (2006) ‘situational couple violence,’ in which IPV is usually mutual, infrequent, not severe, and not part of a general pattern of control and domination. Mutually aggressive relationships tend to be less violent, on average, than relationships in which one partner is much more violent than the other (Swan & Snow, 2003).

Control

Some women use IPV in an attempt to control their partners. Swan and Snow (2003) found that 38% of women who used IPV stated that they had threatened to use violence to make their partners do the things they wanted him to do. Stuart, Moore et al.’s (2006) sample of women arrested for IPV indicated that ‘to feel more powerful’ was a motive 26% of the time; other control-related motives included ‘to get control over your partner,’ 22%; ‘to get your partner to do something or stop doing something,’ 22%; and ‘to make your partner agree with you,’ 17%. Similarly, Follingstad Wright, Lloyd, and Sebastian (1991) found that 22% of college women said they used violence to get control over their partner, while 12% agreed that ‘I feel personally empowered when I behave aggressively against my partner’ (Fiebert & Gonzalez, 1997).

While some individuals use aggression to increase their feelings of control or power, others attribute their aggression to a lack of control over their emotions and themselves (Thomas, 2005). For example, women who were arrested for IPV in Stuart, Moore et al.’s (2006) study endorsed reasons for aggression related to losing self-control, including ‘because your partner provoked you or pushed you over the edge’ and ‘because you didn’t know what to do with your feelings’ (reported 39% and 35% of the time, respectively).

Jealousy

Jealousy is another common motive for women’s IPV. Follingstad et al.’s (1991) college population indicated that 9% of women attributed their aggression toward their partners to jealousy, and Bookwala, Frieze, Smith, and Ryan’s (1992) study of college women found that jealousy was a significant predictor of women’s IPV. Women who were arrested for IPV indicated that ‘because you were jealous,’ ‘because your partner cheated on you,’ and ‘to prove you love your partner’ motivated their violence 25%, 25%, and 27% of the time, respectively (Stuart, Moore et al., 2006).

Tough guise

Most women who use IPV are also victims of aggression from their partners (Swan, Gambone, Caldwell, Sullivan, & Snow, 2008), and this is true for participants in the current study. In the current sample, ninety percent of participants experienced physical aggression from partners, 95% experienced coercive control, and 53% were sexually victimized. In a relationship characterized by IPV, a woman may use aggression to convey the message to her partner that she is not to be trifled with and that he had better take her seriously - there will be violent consequences if he tries to hurt her (Thomas, 2005). Hettrich and O’Leary’s (2007) study of college women’s reasons for their physical aggression in dating relationships illustrates this point with participants’ open-ended explanations of what led up to their aggression, including the response, “to show seriousness” (p. 1138). Similarly, studies have found that a relatively small number of women used IPV for purposes of intimidation. Stuart, Moore et al. (2006) found that women used IPV ‘to make your partner scared or afraid’ 11% of the time. Another study of college women found that 8% of women who used IPV did so to physically harm or injure their partners, while 7% used IPV ‘to intimidate’ their partners (Makepeace, 1986).

Other contributors to IPV

Alcohol and drug use have been found to contribute to IPV, for women as well as men (Caetano, Nelson, & Cunradi, 2001). In a study of women and men arrested for IPV, participants’ substance use and the substance use of their partners predicted participants’ IPV perpetration (Stuart, Meehan, et al., 2006). Stuart, Moore et al.’s (2006) sample of women stated they used violence 18% of the time because they were under the influence of alcohol and 8% of the time because they were under the influence of drugs.

Experiencing abuse during childhood or as an adult in a prior relationship has been found to be related to women’s IPV (Babcock et al., 2003; Ehrensaft et al., 2003; Swan & Snow, 2006). Stuart, Moore et al. (2006) suggested that some women’s IPV is in response to severe victimization in previous relationships and that these women use violence in an attempt to protect themselves from further victimization.

Hypotheses

An exploratory factor analysis (described in the results section) indicated that the Motives and Reasons for IPV scale has five factors: expression of negative emotions, self-defense, control, jealousy, and tough guise. We developed the following hypotheses: (a) All motive factors, except self-defense, will be positively related to the perpetration of physical aggression; (b) the self-defense motive factor will display a curvilinear relationship to the perpetration of physical aggression; (c) all five motive factors will be positively related to the perpetration of psychological aggression; and (d) the motive factors of control and jealousy will be positively related to the perpetration of coercive control.

Sexual aggression is likely a qualitatively different form of aggression than physical or psychological aggression (Frieze, 2005). Because so little is known about women’s perpetration of sexual aggression, no predictions are made regarding the motives and reasons that may be related to this form of aggression.

Method

Participants

A community sample of 150 African-American, 112 White, and 150 Latina women participated in the study (N = 412). Participants were recruited from a Northeastern city by placing English and Spanish-language brochures and posters in various locations, including medical clinics, stores, churches, libraries, restaurants, and laundromats throughout the city. Many (43%) of the participants had family incomes below $10,000 per year, 28% earned $10,000 to $20,000 annually, 17% earned $20,000 to $30,000 annually, and 12% earned over $30,000 per year. Most (64%) of the participants were unemployed, 20% worked part-time, and 14% worked full-time. Twenty-eight percent of participants had not completed high school, 41% graduated from high school or obtained a GED, 23% had some education beyond high school, and 8% earned a college or advanced degree. The average age of participants was 36.6 years (SD = 8.9), with a range of 18 to 65 years. Somewhat less than half (43%) of the sample was unmarried and cohabitating with their partners, 24% were married, 26% were in a dating relationship but lived apart, and 7% had ended their relationships (although they still saw their former partners at least once a week). The length of time that the participants had been with their partners ranged from four months to over twenty years; 9.3% of the participants had been with their partner for one year or less, 41.6% had been with their partner for more than a year up to five years, 36.1% had been with their partner over five years up to fifteen years, and 13.2% had been with their partner for more than fifteen years. The majority (77%) of the women were mothers with an average of 2 children.

Procedure

A short telephone screening was conducted with participants to assess if they met criteria for inclusion in the study. Participants had to self-identify as African-American, White, or Latina, have a yearly family income of no more than $50,000 (to reduce income disparities between racial/ethnic groups), and have committed at least one act of physical violence against a male significant other in the last six months. Participants who met study criteria were invited to participate in face-to-face interviews. A female interviewer of the same race/ethnicity as the participant conducted the two-hour semi-structured interview. Latina participants were interviewed by a bilingual/bicultural interviewer and had the option of being interviewed in Spanish. A bilingual/bicultural research associate translated the survey instruments and recruiting materials as necessary. Seventy-four of the 150 Latina participants completed the interview in Spanish. The measures were administered on notebook computers using Questionnaire Development System software (NOVA Research Company, 2003). Participants were compensated $50 for their time.

Measures

Perpetration and victimization

Perpetration and victimization were assessed with three measures: the revised Conflict Tactics Scale-2 (CTS-2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996), the short Psychological Maltreatment of Women Inventory (PMWI; Tolman, 1999), and the Sexual Experiences Survey (SES; Koss, Gidycz, & Wisniewski, 1987). All CTS-2, PMWI, and SES items were worded to assess the participants’ own aggressive behavior (perpetration) and the aggressive behavior of their partners toward them (victimization) during the past six months. The response scale for all items was: never (0), once in the past six months (1), twice in the past six months (2), three to five times in the past six months (3), six to ten times in the past six months (4), more than ten times in the past six months (5), or not in the past six months but it happened before (6). The sixth option was recoded to zero, since this study specifically examined aggression committed in the past six months.

Physical aggression was assessed using the CTS-2, the most frequently used survey of aggression in the IPV field (Straus et al., 1996). The CTS-2 has demonstrated adequate reliability and validity for female samples (Straus, Hamby, & Warren, 2003). The physical aggression perpetration and victimization scales each included 12 items. The reliability alphas for physical aggression perpetration and victimization in this study were .87 and .91, respectively. A sample item representing physical aggression is: Did you throw something at your partner that could hurt (perpetration); Did your partner throw something at you that could hurt (victimization).

Psychological aggression was assessed by using both the psychological aggression subscale of the CTS-2 (Straus et al., 2003) and the emotional/verbal abuse subscale of the PMWI (Tolman, 1999) for a total of 13 perpetration and 13 victimization items. The PMWI has demonstrated adequate reliability and validity, and has discriminated between abused and non-abused women (Tolman, 1999). The combined psychological aggression measure using items from both scales was more reliable than either the CTS-2 or the PMWI psychological aggression subscales. Psychological perpetration and victimization in this study had reliability alphas of .76 and .83, respectively. An example of an item representing psychological aggression is: Did you insult or swear at your partner (perpetration); Did your partner insult or swear at you (victimization).

Coercive control was measured using the dominance/isolation subscale of the PMWI (Tolman, 1999). The coercive control perpetration and victimization scales each included seven items. In this study, coercive control perpetration and victimization had reliability alphas of .61 and .75, respectively. An example of an item representing coercive control is: Did you monitor your partner’s time and make him account for where he was (perpetration); Did your partner monitor your time and make you account for where you were (victimization).

Sexual aggression was examined with the SES (Koss et al., 1987), which assessed unwanted sexual contact, sexual coercion, attempted rape, and rape. The sexual victimization scale included 10 items. The victimization scale was developed with college populations (Koss et al., 1987) and has been found to be valid and reliable with a sample of community women (Testa, VanZile-Tamsen, Livingston, & Koss, 2004). Because high-level reading skills are necessary to understand the items (Testa et al., 2004), item wording was simplified for the present study. Ten items parallel in wording to the victimization items were added to assess women’s perpetration of sexually aggressive behaviors. The reliability alphas for sexual aggression perpetration and victimization in this study were .92 and .90, respectively. An example of an item representing sexual coercion is: Have you tried to make your partner have sex by using force, like twisting an arm or holding them down, or by threatening to use force (perpetration); Has your partner tried to make you have sex by using force, like twisting your arm or holding you down, or by threatening to use force (victimization).

Motives

The Motives and Reasons for IPV scale was developed for this study (Swan & Sullivan, 2002). Participants were asked, “How often did you use violence, such as slapping, hitting, etc. for the following reasons?” The original measure consisted of 35 motives or reasons with possible responses of never (0), sometimes (1), often (2), and almost always (3). An exploratory factor analysis (see below) was conducted and indicated that a five-factor solution was the best fit. The factors and associated reliability coefficients are expression of negative emotions (5 items, α = .82), self-defense (5 items, α = .86), control (6 items, α = .78), jealousy (2 items, α = .73), and tough guise (8 items, α = .82). The items representing each of these factors are listed in Table 1. The final Motives and Reasons for IPV scale had a total of 26 items and an overall reliability alpha of .92. As explained further below, nine items were deleted from the measure after conducting the exploratory factor analysis.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Motives, Perpetration, Victimization, and Social Desirability

| Motives How often did you use violence… |

% Endorsed |

M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression of negative emotions | 95 | 1.09 | 0.65 |

| Because your partner said something that hurt you | 77 | 1.07 | 0.81 |

| Because he made you angry | 87 | 1.28 | 0.81 |

| Because you wanted to let him know he couldn’t get away with mistreating you |

74 | 1.12 | 0.91 |

| Because you were frustrated | 72 | 1.01 | 0.83 |

| Because you were fed up with his behavior | 67 | 0.98 | 0.89 |

| Control | 89 | 0.74 | 0.55 |

| To make your partner do the things you wanted him to do |

67 | 0.85 | 0.76 |

| Because you wanted him to give you something, like money, or something for your children |

36 | 0.48 | 0.75 |

| Because you wanted him to do something | 57 | 0.70 | 0.74 |

| Because you couldn’t stop yourself | 57 | 0.78 | 0.82 |

| To feel in control | 50 | 0.66 | 0.79 |

| Because he tried to control you | 68 | 0.98 | 0.88 |

| Tough Guise | 84 | 0.45 | 0.46 |

| To harm your partner | 44 | 0.56 | 0.74 |

| To intimidate your partner | 39 | 0.53 | 0.77 |

| Because you feel better after a fight | 18 | 0.24 | 0.56 |

| To scare him | 35 | 0.45 | 0.71 |

| Because you were drinking or using drugs | 33 | 0.47 | 0.79 |

| To physically hurt him | 35 | 0.45 | 0.71 |

| To get “turned on” sexually | 5 | 0.07 | 0.33 |

| To get him to take you seriously | 63 | 0.81 | 0.77 |

| Self-defense | 83 | 0.84 | 0.74 |

| To defend yourself from your partner | 77 | 1.28 | 0.99 |

| To get your partner to stop hitting or hurting you | 65 | 1.07 | 1.03 |

| Because you knew a beating was coming and you wanted to get it over with |

28 | 0.39 | 0.71 |

| Because he became abusive when he drank | 45 | 0.75 | 1.00 |

| To get away as he was beating you | 46 | 0.68 | 0.33 |

| Jealousy | 67 | 0.71 | 0.68 |

| Because you thought your partner was unfaithful | 54 | 0.69 | 0.75 |

| Because you were jealous | 58 | 0.74 | 0.78 |

| Perpetration and Victimization | |||

| Physical aggression perpetration | 100 | 1.00 | 0.80 |

| Psychological aggression perpetration | 100 | 2.19 | 0.83 |

| Coercive control perpetration | 88 | 1.16 | 0.84 |

| Sexual aggression perpetration | 32 | 0.18 | 0.56 |

| Physical aggression victimization | 90 | 0.97 | 0.98 |

| Psychological aggression victimization | 100 | 2.26 | 1.03 |

| Coercive control victimization | 95 | 1.73 | 1.16 |

| Sexual aggression victimization | 53 | 0.50 | 0.93 |

| Social desirability | 3.55 | 0.64 | |

Note. Responses for motive items were: never (0), sometimes (1), often (2), and almost always (3). Responses for perpetration and victimization items were: never (0), once in the past six months (1), twice in the past six months (2), three to five times in the past six months (3), six to ten times in the past six months (4), and more than ten times in the past six months (5). Responses for social desirability items were: strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), undecided or unsure (3), agree (4), and strongly agree (5).

Social desirability

Participants completed a 10-item social desirability measure based on the widely used Marlowe-Crowne scale, containing items such as “No matter who I’m talking to, I’m always a good listener” and “There have been occasions when I took advantage of someone” (reverse-coded; Greenwald & Satow, 1970). The response scale ranged from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). The reliability of the measure in the present study was α = .76.

Data Analyses

Exploratory factor analysis

An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed with the 35 items from the Motives and Reasons for IPV scale. Exploratory factor analysis was chosen over confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) because CFA requires “clear predictions as to which factors exist, how they relate to the variables, and how they relate to each other” (Gorsuch, 1997, p. 534), which were not evident for the Motives and Reasons for IPV scale based on the literature. To identify the underlying factor structure, an EFA was performed in Mplus 5, (Muthén & Muthén, 2007) using the Mean-and Variance-adjusted Weighted Least Square (WLSMV) estimator (due to use of ordinal data) and Promax oblique rotation (due to assumed correlation between factors). EFA is used to identify latent constructs (i.e., factors) with the goal of understanding the structure of correlations among the observed variables. Specifically, EFA models the structure of correlations among observed variables by estimating the pattern of relations between the common factor(s) and each of the measured variables (as indexed by factor loadings) (Fabrigar, Wegener, MacCallum, & Strahan, 1999). The final solution (i.e., factor model) was selected through evaluation of the following model fit criteria. A model that is generally interpreted as providing a good fit to the data is one that has a root mean square of approximation (RMSEA) value ≤ .05, a root mean squared residual (SRMR) ≤.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999), and a Comparative Fit Index (CFI) value close to 1 (Bentler, 1990).

Regression analyses

Because only 3.4% of the data was missing, listwise deletion was used to address missing values (Schafer, 1999). Hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to examine the relationship between the factors in the Motives and Reasons for IPV measure and participants’ perpetration of physical, psychological, and sexual aggression and coercive control toward partners. The covariates of women’s physical, psychological, and sexual victimization, coercive control, and social desirability were entered in the first step of each regression analysis. Victimization was controlled for in the analyses because a strong relationship between victimization from partners and female perpetration of IPV has been found in several studies (Graves, Sechrist, White, & Paradise, 2005; Magdol, Moffitt, Caspi, Newman, Fagan, & Silva, 1997; Sullivan, Meese, Swan, Mazure, & Snow, 2005; Swan, Gambone, Fields, Sullivan, & Snow, 2005). Similarly, as social desirability concerns may impact women’s reports of motives, social desirability was entered as a covariate. The five factors (i.e., expression of negative emotions, self-defense, control, jealousy, and tough guise) were entered in the second step.

In order to test for a nonlinear relationship between self-defense and physical perpetration, we used a polynomial regression approach (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003). Polynomial equations relate X to Y by using transformed variables (X2, X3, etc.) that possess a known nonlinear relationship to the original variables. By structuring nonlinear relationships in this way, it is possible to determine whether the relationship between X and Y is nonlinear, as well as the form of the relationship.

In the current analyses, we tested for a curvilinear relationship between the self-defense motive factor and physical perpetration by centering the self-defense motive (i.e., subtracting the overall self-defense mean from each score) variable and then creating a polynomial term (X2) from the centered variable. Centering of predictors in this manner renders all regression coefficients in a polynomial regression equation meaningful by reflecting the regression function at the mean of the predictor. Centering also eliminates the extreme multicollinearity resulting from using powers of predictors in a single equation (Cohen et al., 2003). To properly test for the presence of a curvilinear relationship, the highest order term (which determines the overall shape of the regression function) is entered with all lower order terms (Aiken & West, 1991; Cohen et al., 2003). The centered linear and polynomial forms of the self-defense variable were used as predictors in the regression analysis to test for the presence of a curvilinear relationship.

Results

Exploratory Factor Analysis: Determining the Number of Factors

To determine the number of factors on the Motives and Reasons for IPV scale, we first examined the eigenvalues for the correlation matrix based on all 35 items. The Kaiser (1960) criterion, which recommends that the number of factors be equivalent to the number of eigenvalues > 1, suggested 7 factors. Based on research that suggested the Kaiser criterion tends to overestimate the number of factors as the number of variables approaches 40 (Stevens, 2002), the value of 7 was regarded as the upper limit for the number of factors.

Next, we examined the scree plot as proposed by Cattel (1966) as a graphical method for determining the number of factors. Cattel (1966) recommended retaining all eigenvalues in the sharp descent before the point at which the plot begins to level off. The plot suggested that a model containing 1-6 factors was most appropriate for consideration.

Third, we conducted an EFA with the 35 items from the Motives and Reasons for IPV scale. After estimating a model with the number of factors ranging from 1 to 6, we considered interpretability of the results suggested by the EFA by examining the item pattern and structure coefficients (commonly called “factor loadings”). In EFA, the contribution of a variable to a given factor is indicated by both factor pattern and structure coefficients. Thompson and Daniel (1996) noted that structure coefficients, or correlations between observed and latent variables, “are usually essential to interpretation” (p. 199).

In factor analysis, the factor structure matrix gives the correlations between all observed variables and all extracted (latent) factors. When factors are orthogonally rotated, they remain uncorrelated, and the factor structure matrix will be an identity matrix, exactly matching the factor pattern matrix (Gorsuch, 1983). However, when an oblique rotation is used, as in the current study, the factors are allowed to correlate with each other. In such cases, the factor correlation matrix will not be an identity matrix, and the structure matrix will not equal the pattern matrix. Appropriate interpretation, then, must invoke both the factor pattern and factor structure matrices (Courville & Thompson, 2001; Thompson & Borrello, 1985). To decide which items were significant indicators of a factor (i.e., “loaded on a factor”), we used a cutoff of .40, which exceeds the .30 criteria suggested by Briggs and MacCallaum (2003). After examining the matrices, the five factor model was considered best among other alternatives with regard to interpretability and other decision criteria. The fit indices for the five factor model with 35 items indicated a good fit of the model to the data: χ2(117, N = 412) = 310.60, p ≤ .0001; RMSEA = 0.06; SRMR = .05. (In large samples, a significant chi-square is not necessarily indicative of poor model fit; see Barrett, 2007.) Pattern and structure matrices for the final model are shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Table 2.

Exploratory Factor Analysis Pattern Coefficient Matrix

| Control |

Tough Guise |

Self- Defense |

Express. Negative Emotions |

Jealousy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control Subscale (α = .78) | |||||

|

| |||||

| 1. To make your partner do the things you wanted him to do |

.79 | −.11 | −.01 | −.02 | .10 |

| 13. Because you wanted him to give you something, like money, or something for your children |

.64 | .27 | .02 | −.11 | −.07 |

| 14. Because you wanted him to do something |

.86 | −.01 | −.06 | −.05 | .01 |

| 15. Because you couldn’t stop yourself | .56 | −.01 | −.11 | .29 | −.04 |

| 25. To feel in control | .51 | .25 | −.15 | .03 | .15 |

| 29. Because he tried to control you | .47 | −.22 | .37 | .22 | .04 |

|

| |||||

| Tough G uise Subscale (α = .82) | |||||

|

| |||||

| 9. To harm your partner | −.09 | .89 | .12 | −.12 | .02 |

| 10. To intimidate your partner | .09 | .68 | −.08 | .16 | .11 |

| 19. Because you feel better after a fight | .11 | .67 | −.09 | .13 | .03 |

| 20. To scare him | .34 | .59 | −.06 | −.03 | .05 |

| 26. Because you were drinking or using drugs |

.03 | .59 | .13 | −.09 | −.10 |

| 32. To physically hurt him | −.05 | .79 | .25 | −.15 | .02 |

| 34. To get “turned on” sexually | −.01 | .74 | .02 | −.08 | .02 |

| 36. To get him to take you seriously | .21 | .40 | −.01 | .31 | −.07 |

|

| |||||

| Self-Defense Subscale (α = .86) | |||||

|

| |||||

| 3. To defend yourself from your partner |

−.05 | −.05 | .84 | .17 | .09 |

| 4. To get your partner to stop hitting or hurting you |

−.23 | .01 | .97 | .05 | .13 |

| 16. Because you knew a beating was coming and you wanted to get it over with |

.39 | .03 | .63 | −.03 | −.06 |

| 17. Because he became abusive when he drank |

.18 | .04 | .61 | .07 | −.07 |

| 33. To get away as he was beating you | −.05 | .16 | .89 | −.14 | .09 |

|

| |||||

| Exp. Neg. Emot. Subscale (α = .82) | |||||

|

| |||||

| 8. Because your partner said something that hurt you |

.28 | −.16 | .16 | .52 | .11 |

| 11. Because he made you angry | .34 | −.19 | −.04 | .66 | .09 |

| 12. Because you wanted to let him know he couldn’t get away with mistreating you |

−.16 | .27 | .25 | .55 | .02 |

| 18. Because you were frustrated | .47 | −.11 | −.03 | .54 | −.02 |

| 23. Because you were fed up with his behavior |

.11 | .22 | .26 | .49 | −.04 |

|

| |||||

| Jealousy Subscale (α = .73; r=.57 ) | |||||

|

| |||||

| 6. Because you thought your partner was unfaithful |

.10 | .01 | .21 | −.03 | .79 |

| 27. Because you we re jealous | .02 | .14 | .00 | .12 | .69 |

|

| |||||

| Dropped Items | |||||

|

| |||||

| 2. To get even with your partner for something he had done |

.16 | .33 | −.03 | .14 | .29 |

| 7. To prevent your partner from leaving or going out |

.16 | .33 | .11 | −.01 | .33 |

| 21. To stop the argument | .33 | .25 | .12 | .17 | −.13 |

| 22. As a joke or just playing around | −.26 | .49 | −.18 | .15 | .04 |

| 24. Because he was being mean to you |

.02 | .10 | .41 | .50 | −.09 |

| 28. To get your point across | .19 | .32 | −.11 | .42 | .04 |

| 30. Because you have a bad temper | .30 | .22 | −.22 | .35 | .04 |

| 31. Because of your past abusive relationships |

.25 | .30 | −.01 | .16 | −.10 |

| 35. To get him to leave you alone | .00 | .37 | .39 | .17 | −.17 |

Note: Factor loadings in bold represent items that were retained for that factor.

Table 3.

Exploratory Factor Analysis Structure Coefficient Matrix

| Control | Tough Guise |

Self- Defense |

Express. Negative Emotions |

Jealousy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control Subscale (α = .78) | |||||

|

| |||||

| 1. To make your partner do the things you wanted him to do |

.76 | .27 | .16 | .38 | .31 |

| 13. Because you wanted him to give you something, like money, or something for your children |

.69 | .49 | .26 | .36 | .18 |

| 14. Because you wanted him to do something |

.82 | .35 | .14 | .54 | .23 |

| 15. Because you couldn’t stop yourself | .67 | .36 | .14 | .54 | .23 |

| 25. To feel in control | .65 | .49 | .09 | .44 | .40 |

| 29. Because he tried to control you | .60 | .27 | .50 | .50 | .20 |

|

| |||||

| Tough Guise Subscale (α = .82) | |||||

|

| |||||

| 9. To harm your partner | .29 | .83 | .37 | .35 | .23 |

| 10. To intimidate your partner | .50 | .81 | .24 | .58 | .39 |

| 19. Because you feel better after a fight | .47 | .77 | .23 | .53 | .31 |

| 20. To scare him | .59 | .72 | .24 | .46 | .32 |

| 26. Because you were drinking or using drugs |

.26 | .58 | .33 | .26 | .06 |

| 32. To physically hurt him | .31 | .79 | .48 | .35 | .20 |

| 34. To get “turned on” sexually | .30 | .70 | .26 | .32 | .21 |

| 36. To get him to take you seriously | .29 | .83 | .37 | .35 | .23 |

|

| |||||

| Self-Defense Subscale (α = .86) | |||||

|

| |||||

| 3.To defend yourself from your Partner |

.27 | .34 | .86 | .42 | .12 |

| 4. To get your partner to stop hitting or hurting you |

.10 | .32 | .93 | .30 | .09 |

| 16. Because you knew a beating was coming and you wanted to get it over with |

.54 | .41 | .74 | .40 | .07 |

| 17. Because he became abusive when he drank |

.38 | .37 | .70 | .38 | .03 |

| 33. To get away as he was beating you | .22 | .41 | .89 | .25 | .09 |

|

| |||||

| Exp. Neg. Emot. Subscale (α = .82) | |||||

|

| |||||

| 8. Because your partner said something that hurt you |

.57 | .35 | .36 | .68 | .32 |

| 11. Because he made you angry | .62 | .33 | .21 | .75 | .35 |

| 12. Because you wanted to let him know he couldn’t get away with mistreating you |

.33 | .59 | .50 | .70 | .22 |

| 18. Because you were frustrated | .69 | .38 | .24 | .71 | .27 |

| 23. Because you were fed up with his Behavior |

.54 | .62 | .53 | .75 | .22 |

|

| |||||

| Jealousy Subscale (α = .73; r=.57 ) | |||||

|

| |||||

| 6. Because you thought your partner was unfaithful |

.39 | .35 | .24 | .35 | .81 |

| 27. Because you were jealous | .37 | .43 | .10 | .43 | .78 |

|

| |||||

| Dropped Items | |||||

|

| |||||

| 2. To get even with your partner for something he had done |

.48 | ..56 | .18 | ..49 | .49 |

| 7. To prevent your partner from leaving or going out |

.44 | .53 | .27 | .39 | .48 |

| 21. To stop the argument | .53 | .50 | .36 | .48 | ,10 |

| 22. As a joke or just playing around | .01 | .40 | −.02 | .22 | .15 |

| 24. Because he was being mean to you |

.41 | .50 | .62 | .67 | .11 |

| 28. To get your point across | .55 | .60 | .20 | .67 | .33 |

| 30. Because you have a bad temper | .54 | .48 | .06 | .57 | .31 |

| 31. Because of your past abusive Relationships |

.45 | .48 | .23 | .43 | .13 |

| 35. To get him to leave you alone | .32 | .55 | .58 | .45 | .00 |

Note: Factor loadings in bold represent items that were retained for that factor.

Exploratory factor analysis in a confirmatory factor analysis framework

In order to make sure that the large values of the factor loadings found in EFA were in fact all statistically significant, to see if the low value of the factor loadings was statistically non-significant, and to identify the items that were unrelated to any of the factors in a statistically significant way, we ran a confirmatory factor model equivalent to the above exploratory factor model with five factors (Jöreskog, 1969; Skrondal & Rabe-Hesketh, 2004) to obtain standard errors for item loadings. To fit the EFA model in a CFA framework, one must use the same number of restrictions as in an EFA model, where the number of restrictions is equal to the number of factors squared. For our model we imposed 25 (52) restrictions by: (a) fixing factor variances to a value of 1 for all five factors; (b) choosing an anchor item for each factor (i.e., an item with a large loading for a given factor and small loadings for the other factors) and fixing the factor loading for the “anchored” factor to 1; (c) fixing the factor loadings for anchor items on all other factors to be 0; and (d) allowing all other factor loadings to be free. For our data, items 4, 6, 9, 11, and 14 were selected as anchors for their respective factors. These restrictions resulted in the same number of restrictions as the traditional EFA model and thus, gave the same chi-square and p-values, χ2(117, N = 412) = 310.60, p ≤ .0001; RMSEA = 0.06; SRMR = .05; CFI = .93,, suggesting a very good model fit.

To decide which items were significant indicators of a factor (i.e., “loaded on a factor”), we considered both statistical and substantive significance. For the statistical significance, we used the t-value ≥ 1.96. This value was chosen so that the individual Type I error rate was approximately .01 when the family-wise Type I error rate was set to .025 for Bonferroni adjustment of about 175 (35 × 5) simultaneous tests on the factor loadings. The conservative Type I error rate protected against finding statistically significant factor loadings simply by chance. To assess substantive significance, we used the cutoff value of .40 for the factor loading. Items not meeting these statistical and substantive significance criteria or that significantly loaded on multiple factors were dropped.

Considering significance according to the cutoff values stated above, eight items (2, 7, 21, 24, 28, 30, 31, and 35) were unrelated to any factor and dropped. One item (22) reduced scale reliability and therefore was dropped. The final measure retained 26 of the original 35 items with excellent reliability (α = .92). We conducted an additional EFA using only the items that comprised the five factor structure. Refitting these remaining 26 items resulted in very good model fit, superior to the fit of the 35 items, χ2(117, N = 412) = 215.55, p ≤ .0001; RMSEA = 0.06; SRMR = .04.

Descriptive Analyses

All five of the motive factors assessed were commonly viewed by the participants as motives for their aggression toward partners (see Table 1 for descriptive statistics on the motive factors and individual items). The participants most frequently endorsed motives relating to the expression of negative emotions: almost 95% of the women indicated that negative emotions were a cause of their aggression, with “because he made you angry” being the most frequently endorsed item. Over 89% endorsed motives relating to control. Interestingly, motives relating both to women reacting against being controlled by their partners and to the women’s attempts to control their partners loaded onto this factor: 68% of women stated that they used aggression “because he tried to control you” and 67% used aggression “to make your partner do the things you wanted him to do.” Eighty-four percent indicated they used aggression to be taken seriously or to intimidate or harm their partner. This factor is primarily driven by wanting their partner to take them seriously (63%); fewer women actually wanted to harm their partner (44%). Eighty-three percent of women indicated that self-defense was a motive for their aggression, and around two-thirds stated their aggression was motivated by jealousy. It is clear that many participants indicated multiple motives for their perpetration of partner aggression. The participants endorsed an average of 14 of the 26 motive items in the final scale.

Table 1 also provides descriptive statistics for women’s perpetration of and victimization by IPV, as well as social desirability. Paired samples t tests were conducted to compare mean perpetration and victimization frequencies. Physical IPV perpetration and victimization means for the participants were not significantly different (t = 0.79, p > .05), and neither were psychological aggression perpetration and victimization means (t = −1.58, p > .05). Sexual perpetration and victimization means (t[411]= −7.24, p = .000) and coercive control perpetration and victimization means (t[411] = −9.21, p = .000) were significantly different. Women reported that they were victims of sexual aggression and coercive control significantly more than they perpetrated these types of aggression.

Regression Analyses

Hypothesis 1, that all motive factors except self-defense would be positively related to the perpetration of physical aggression, received support (see Table 4). The motive factors – expression of negative emotions, control, jealousy, and tough guise – were significantly and positively related to the perpetration of physical aggression after controlling for previous victimization from partners and social desirability, and added predictive utility to the model.

Table 4.

Regression Analysis for Female Perpetration of Physical Aggression (N = 412)

| Variable | B | SEB | β | R2 | ΔR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | .310*** | .310*** | |||

| Social desirability | −.04 | .05 | −.03 | ||

| Physical victimization | .45 | .04 | .55*** | ||

| Psychological victimization | .02 | .04 | .03 | ||

| Coercive control victimization | −.08 | .05 | −.07 | ||

| Sexual victimization | −.06 | .04 | −.06 | ||

| Step 2 | .555*** | .245*** | |||

| Expression of negative emotions | .72 | .16 | .24*** | ||

| Self-defense (centered) | −.75 | .15 | −.29*** | ||

| Control | .34 | .14 | .12* | ||

| Jealousy | .68 | .28 | .10* | ||

| Tough guise | .66 | .12 | .25*** | ||

| Self-defense (quadratic) | .04 | .02 | .08A |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

p < .07

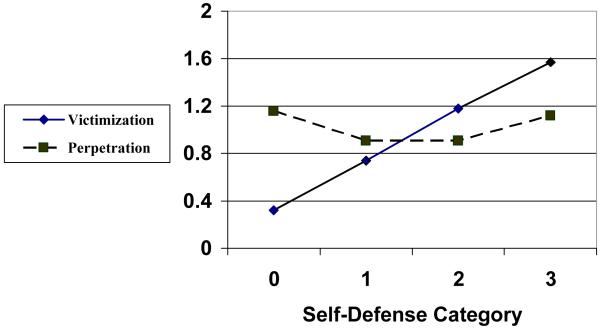

Hypothesis 2, that the self-defense motive factor would display a curvilinear relationship to the perpetration of physical aggression, received partial support (see Table 4 & Figure 1). The quadratic self-defense term, which tested for a curvilinear relationship, did approach significance (p = .069), after controlling for previous victimization from partners and social desirability.

Figure 1. Mean Physical Victimization and Perpetration for Participants by Level of Self-Defense Category.

Note: For the self-defense categories, 0 = participants who never endorsed self-defense as a motive; 1 = participants who had low scores on the self-defense scale; 2 = participants who had moderate scores on the self-defense scale; and 3 = participants who had high scores on the self-defense motive scale.

To further assess the relationship between the self-defense motive and physical aggression perpetration as well as physical victimization, ANCOVAs were conducted. Participants were divided into four categories, based on their scores on the self-defense scale: participants who never endorsed self-defense as a motive (0); those who had low scores on the self-defense scale (1); those who had moderate scores on the self-defense scale (2); and those who had the highest scores on the self-defense scale (3). First, this variable was used to predict physical aggression, with physical victimization as a covariate. Physical aggression perpetration did differ significantly by self-defense category, F(3, 407) = 3.91, p < .01 (see Figure 1). Post-hoc tests revealed the predicted curvilinear pattern: Participants who never endorsed self-defense as a motive, and those with the high scores on the self-defense scale, had significantly higher frequencies of physical aggression perpetration than participants in the low and moderate categories. Second, the four-category self-defense motive was used to examine the relationship between self-defense motives and physical victimization, while controlling for physical perpetration. Physical victimization also differed significantly by self-defense category, F(3, 407) = 45.50, p < .001 (see Figure 1). Taken together, these results indicate that participants who never use aggression in self-defense are highly aggressive, and experience low levels of victimization. Participants with the highest scores on self-defense are highly aggressive but also are very highly victimized; their aggression appears to be in self-defense. Individuals in the middle two groups use aggression and are victimized at similar rates, and are less aggressive than those with the highest or lowest scores on self-defense.

Hypothesis 3, that all five motive factors would be positively related to the perpetration of psychological aggression, also received partial support (see Table 5). Expression of negative emotions, control, and tough guise were significantly and positively related to the perpetration of psychological aggression after controlling for previous victimization from partners and social desirability, and added predictive utility to the model. Contrary to our prediction, the jealousy motive was unrelated, and the self-defense motive was significantly and negatively related to perpetrating psychological aggression toward partners.

Table 5.

Regression Analysis for Female Perpetration of Psychological Aggres sion (N = 412)

| Variable | B | SEB | β | R2 | ΔR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | .332*** | .332*** | |||

| Social desirability | −.11 | .06 | −.07 | ||

| Physical victimization | .003 | .05 | .003 | ||

| Psychological victimization | .46 | .04 | .56*** | ||

| Coercive control victimization | −.001 | .06 | −.001 | ||

| Sexual victimization | −.05 | .05 | −.04 | ||

| Step 2 | .482*** | .150 *** | |||

| Expression of negative emotions | .72 | .19 | .22*** | ||

| Self-defense | −.72 | .15 | −.25*** | ||

| Control | .53 | .17 | .16** | ||

| Jealousy | .12 | .33 | .01 | ||

| Tough guise | .44 | .14 | .15** |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Hypothesis 4 was supported by the data (see Table 6). The motive factors of control and jealousy were significantly and positively related to the perpetration of coercive control after controlling for previous victimization from partners and social desirability, and added predictive utility to the model.

Table 6.

Regression Analysis for Female Perpetration of Coercive Control (N = 412)

| Variable | B | SEB | β | R2 | ΔR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | .088*** | .088*** | |||

| Social desirability | −.05 | .04 | −.05 | ||

| Physical victimization | .00 | .03 | .00 | ||

| Psychological victimization | .08 | .03 | .19* | ||

| Coercive control victimization | .14 | .04 | .19** | ||

| Sexual victimization | −.06 | .03 | −.10* | ||

| Step 2 | .304*** | .216 *** | |||

| Expression of negative emotions | −.21 | .12 | −.12 | ||

| Self-defense | −.07 | .09 | −.05 | ||

| Control | .24 | .11 | .13* | ||

| Jealousy | 2.11 | .21 | .49*** | ||

| Tough guise | −.08 | .09 | −.05 |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Table 7 provides a summary of the regression findings for sexual aggression perpetration. The tough guise motive factor was significantly and positively related to the perpetration of sexual aggression after controlling for previous victimization from partners and social desirability, and added predictive utility to the model.

Table 7.

Regression Analysis for Female Perpetration of Sexual Aggression (N = 412)

| Variable | B | SEB | β | R2 | ΔR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | .180*** | .180*** | |||

| Social desirability | −.05 | .04 | −.06 | ||

| Physical victimization | −.03 | .03 | −.06 | ||

| Psychological victimization | .004 | .03 | .01 | ||

| Coercive control victimization | −.06 | .04 | −.09 | ||

| Sexual victimization | .25 | .03 | .41*** | ||

| Step 2 | .248*** | .068 *** | |||

| Expression of negative emotions | −.15 | .12 | −.09 | ||

| Self-defense | −.07 | .09 | −.05 | ||

| Control | .05 | .11 | .03 | ||

| Jealousy | .39 | .21 | .09 | ||

| Tough guise | .41 | .09 | .27*** |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Discussion

Participants in the present study perceived their aggressive behavior toward their partners as driven by complex, multiple motives. On average, women indicated that 14 of the motives and reasons for using aggression against their male intimate partners applied to them at least some of the time. Both proactive and defensive motives were very commonly endorsed. The exploratory factor analysis resulted in a Motives and Reasons for IPV scale with excellent model fit and five theoretically meaningful factors: expression of negative emotions, self-defense, control, jealousy, and tough guise.

Expressing negative emotions is clearly an important motive for women’s perpetration of IPV, consistent with other studies (Babcock et al., 2003; Hamberger, Lohr, & Bonge, 1994; Stuart, Moore et al., 2006). The top four most frequently endorsed items (“he made you angry,” “he said something that hurt you,” “you wanted to let him know he couldn’t get away with mistreating you,” and “you were frustrated”) were components of this factor. Furthermore, participants who scored highly on the expressing negative emotions factor committed more frequent physical and psychological aggression, even when controlling for victimization and social desirability.

Self-defense is also an important motive for women’s aggression. The second most frequently endorsed item (“to defend yourself from your partner”) was in the self-defense factor. As predicted, evidence was found for a curvilinear relationship between the self-defense motive and women’s physical aggression. Although the quadratic term in the regression analysis only approached significance, the relationship between the self-defense motive and aggression was statistically significant in the ANCOVA and did show the curvilinear pattern. Women who never endorsed the self-defense motive appeared to be primary aggressors. These women reported high levels of aggression and experienced low victimization. In contrast, women who endorsed high levels of self-defense also used high levels of aggression, but their victimization was even greater. These findings suggest that these women’s aggression is often in self-defense. The two middle groups endorsed moderate levels of self-defense motives, and the frequency of aggression they used was more similar to the frequency of victimization they experienced, relative to the high and no self-defense groups. Their relationships may resemble situational couple violence, in which IPV is usually mutual, less frequent, not severe, and not part of a general pattern of control and domination (Johnson, 2006).

An unexpected negative relationship emerged between the self-defense motive and psychological aggression. This may be because at high levels of self-defense, women seldom use psychological aggression because they do not want to further escalate their partner’s violence. In contrast, at low levels of self-defense, women may not be concerned about violent retaliation from partners and so use psychological aggression freely.

The control motive factor was an interesting combination of items relating to women’s efforts to control their partners’ behavior (e.g., “to make him do the things you wanted him to do”), and items relating to women’s lack of control (e.g., “because he tried to control you”). The positive relationship between control motives and physical, psychological, and coercive control aggression suggests that at times women used aggression in a calculated attempt to get their partners to behave in a particular way, but some women also appeared to have used aggression to respond to their partners’ attempts to control them. Still, other women indicated their aggression was due to an inability to control themselves (e.g., “because you couldn’t stop yourself”).

The jealousy motive factor only had two items; however, the subscale was reliable and showed a strong positive relationship with coercive control perpetration, as well as a significant but small relationship with physical aggression. These findings are consistent with other literature, including a previous study that found jealousy was a significant predictor of women’s IPV (Bookwala et al., 1992).

The tough guise motive factor contains motives to appear tough, intimidating, and willing to harm one’s partner if necessary. By far, the most frequently endorsed item in this factor was “to get him to take you seriously.” This tough guise may, in part, be in response to the high levels of victimization experienced by most of the women in the sample; women endorsing these motives may adopt a tough guise as a strategy to protect them from further harm by their partners. Furthermore, many of the women in the sample were very poor and lived in inner-city neighborhoods with frequent community violence. Appearing tough may be a way to cope with these difficult living conditions. The item “because you were drinking or using drugs” indicates that substance use plays a role as well, perhaps by reducing inhibitions toward aggressive behavior. The tough guise factor was related to greater physical and psychological aggression.

Sexual aggression appears to be a distinct form of IPV. It is relatively unusual for women to perpetrate sexual aggression. Women were significantly more likely to be victims of sexual aggression than to perpetrate this behavior. Nevertheless, 32% of women did use some form of sexual aggression against their partners in the past six months. The only motives factor that was related to women’s perpetration of sexual aggression was tough guise. This is likely driven in part by the “to get ‘turned on’ sexually” item that loaded on this factor. These results suggest that some women may use sexual aggression to frighten and intimidate their partners. Given the unique, negative effects of sexual victimization (Frieze, 2005) and the paucity of information on women’s sexually aggressive behavior, the sexual component of IPV is a critical area for future study.

Limitations

We were surprised that a retaliation factor did not emerge from the factor analysis, as several previous studies have found that retaliation is a motive for women’s IPV (see Swan et al., 2008). However, the Motives and Reasons for IPV scale had only one item assessing retaliation (“to get even with your partner for something he had done”), and this item failed to load on any factor. Thus, we acknowledge that there is room for revising the instrument, including adding retaliation items to determine whether such a factor might emerge in future analyses. Another avenue for future research would be to add additional jealousy items to improve the reliability of this factor.

A further limitation of the study is its reliance on self-report measures. Although self-report data is common within the IPV field, it does not take into account the other partner’s viewpoint and also could be influenced by the reporter’s memory or goal to appear socially desirable to the interviewer. For this reason, social desirability was controlled for in the regression analyses, and findings revealed that it was unrelated to women’s reports of their aggression. A second limitation is that the participants were questioned regarding their motives or reasons for engaging in IPV weeks or months after the incidents occurred. Again, this is the typical method used in studies of IPV motives, but one cannot be sure how closely the retrospective report relates to the psychological processes motivating people’s behavior when they are actually in the moment, and how conscious they are of their motives (Hamberger et al., 1994; Stuart, Moore et al., 2006). Participants may have difficulty remembering or identifying their reasons for committing IPV, especially given the highly distressing nature of these incidents.

The dual perpetrator and victim status of most participants meant that it was essential to control for victimization when examining the relationships between motives and aggression. Therefore, building these controls into the regression models is viewed as a strength of the study. Without controlling for victimization, what appears to be a relationship between motives and aggression could actually be a function of the relationship between victimization and aggression.

Implications

This study has a number of implications for intervention programs for domestically violent women. We concur with Stuart, Moore et al. (2006) and Hettrich and O’Leary (2007) that addressing the motives that women themselves see as underlying their use of violence is a promising approach. Obviously, for most women who use IPV, victimization issues need to be addressed through safety planning and access to community resources that can help provide protection from their partner’s violence. It is very unlikely that women’s aggression will end unless their partners’ violence against them is stopped. Victimization is an especially important topic to address given the large number of women who used violence in self-defense. Violence motivated by self-defense may ultimately increase women’s vulnerability to further victimization (Dasgupta, 2002; Stuart, Moore et al., 2006).

While victimization and defensive motives are essential components of women’s IPV, they are clearly not the whole story. Proactive motives also were frequently endorsed, and importantly, were predictive of women’s perpetration of IPV. Expressing anger or frustration – characteristic of poor emotion regulation (Stuart, Moore et al., 2006) – was related to physical aggression and represents an important area of intervention. Building positive coping skills to assist domestically violent women in regulating and expressing their emotions in healthier ways may lead to less perpetration of aggression. Trying to control the partner, jealousy, and attempting to harm or scare the partner to appear tough also were related to women’s aggression. Findings from this study suggest that interventions for domestically violent women should not minimize the impact of women’s own tendencies to act aggressively, for several reasons. First, although women are less likely to injure male partners than vice-versa, men’s injuries should not be underestimated. Archer’s (2000) meta-analysis of IPV studies found that 38% of individuals injured by IPV were male. Second, violence for any reason may establish norms in the relationship that violence is acceptable, resulting in an increase in violence over time (Frieze, 2005). Third, women’s violence may ultimately increase women’s vulnerability to further victimization (Dasgupta, 2002; Stuart, Moore et al., 2006). Interventions that help participants understand what a healthy relationship is, with a focus on building coping strategies that include participants’ use of assertive and effective communication, problem-solving skills, and social support, rather than aggression, will lead to more healthy relationships, and are essential approaches to both the prevention and treatment of IPV perpetration.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by funding from the National Institute of Justice (2001-WT-BX-0502) and the University of South Carolina Research Foundation.

Biography

Jennifer E. Caldwell, M.A., is pursuing her Ph.D. in Clinical-Community Psychology at the University of South Carolina. Her research interests include motives, outcomes, female perpetration, and prevention/intervention of intimate partner violence.

Suzanne C. Swan, Ph.D., is an assistant professor in the Department of Psychology and the Women’s & Gender Studies Program at the University of South Carolina. She received her Ph.D. in social and personality psychology from the University of Illinois.

Christopher T. Allen, M.A., is a Ph.D. candidate in Clinical-Community Psychology at the University of South Carolina. His research interests include exploring relationships between gender, violence, prevention.

Tami P. Sullivan, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor in the Division of Prevention and Community Research and Director, Family Violence Research and Programs, Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine. Dr. Sullivan’s program of research focuses on understanding (a) precursors, correlates, and outcomes of women’s victimization and their use of aggression in intimate relationships, and (b) the co-occurrence of IPV, posttraumatic stress, and substance use with specific attention to daily processes and intensive longitudinal data. She is particularly interested in risk and protective factor research that informs the development of interventions to be implemented in community settings.

David L. Snow, Ph.D., is a Professor of Psychology in Psychiatry, Child Study Center, and Epidemiology & Public Health at Yale University School of Medicine, and is Director of The Consultation Center and Division of Prevention and Community Research in the Department of Psychiatry. His work has focused extensively on the design and evaluation of preventive interventions and on research aimed at identifying key risk and protective factors predictive of psychological symptoms, substance use, and family violence. He also has special interests in the protective and stress-mediating effects of coping and social support and in methodological and ethical issues in prevention research.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Beverly Hills, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Archer J. Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:651–680. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock JC, Miller SA, Siard C. Toward a typology of abusive women: Differences between partner-only and generally violent women in the use of violence. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2003;27:153–161. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett P. Structural equation modeling: Adjusting model fit. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;42:815–824. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookwala J, Frieze IH, Smith C, Ryan K. Predictors of dating violence: A multivariate analysis. Violence and Victims. 1992;7:297–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs NE, MacCallum RC. Recovery of weak common factors by maximum likelihood and ordinary least squares estimation. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2003;38:25–56. doi: 10.1207/S15327906MBR3801_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Nelson S, Cunradi C. Intimate partner violence, dependence symptoms and social consequences from drinking among White, Black and Hispanic couples in the United States. American Journal on Addictions. 2001;10:60–69. doi: 10.1080/10550490150504146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattel RB. The meaning and strategic use of factor analysis. In: Cattel RB, editor. Handbook of multivariate experimental psychology. Rand McNally; Chicago: 1966. pp. 174–243. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Courville T, Thompson B. Use of structure coefficients in published multiple regression articles: β is not enough. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2001;61:229–248. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta SD. A framework for understanding women’s use of nonlethal violence in intimate heterosexual relationships. Violence Against Women. 2002;8:1364–1389. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Coie JD. Social-information-processing factors in reactive and proactive aggression in children’s peer groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;53:1146–1158. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.53.6.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft MK, Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes E, Chen H, Johnson J. Intergenerational transmission of partner violence: A 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:741–753. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrigar L, Wegener D, MacCallum R, Strahan E. Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychological Methods. 1999;4:272–299. [Google Scholar]

- Fiebert MS, Gonzalez DM. College women who initiate assaults on their male partners and the reasons offered for such behavior. Psychological Reports. 1997;80:583–590. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1997.80.2.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske ST. Social beings: A core motives approach to social psychology. 1st ed. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Follingstad DR, Wright S, Lloyd S, Sebastian JA. Sex differences in motivations and effects in dating violence. Family Relations. 1991;40:51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Frieze IH. Hurting the one you love: Violence in relationships. Thompson Wadsworth; Belmont, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gorsuch RL. Factor analysis. 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Gorsuch RL. Exploratory factor analysis: Its role in item analysis. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1997;68:532–560. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6803_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves KN, Sechrist SM, White JW, Paradise MJ. Intimate partner violence perpetrated by college women within the context of a history of victimization. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2005;29:278–289. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald HJ, Satow Y. A short social desirability scale. Psychological Reports. 1970;27:131–135. [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger LK, Guse CE. Men’s and women’s use of intimate partner violence in clinical samples. Violence Against Women. 2002;8:1301–1331. [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger LK, Lohr JM, Bonge D. The intended function of domestic violence is different for arrested male and female perpetrators. Research and Treatment Issues. 1994;10:40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Harned MS. Abused women or abused men? An examination of the context and outcomes of dating violence. Violence and Victims. 2001;16:269–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettrich EL, O’Leary KD. Females’ reasons for their physical aggression in dating relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2007;22:1131–1143. doi: 10.1177/0886260507303729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP. Conflict and control: Gender symmetry and asymmetry in domestic violence. Violence Against Women. 2006;12:1003–1018. doi: 10.1177/1077801206293328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog KG. A general approach to confirmatory maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1969;34:183–202. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser HF. The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- Kernsmith P. Exerting power or striking back: A gendered comparison of motivations for domestic violence perpetration. Violence & Victims. 2005;20:173–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel MS. “Gender symmetry” in domestic violence. Violence Against Women. 2002;8:1332–1363. [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Gidycz CA, Wisniewski N. The scope of rape: Incidence and prevalence of sexual aggression and victimization in a national sample of higher education students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55:162–170. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magdol L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Newman DL, Fagan J, Silva PA. Gender differences in partner violence in a birth cohort of 21-year-olds: Bridging the gap between clinical and epidemiological approaches. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:68–78. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makepeace JM. Gender differences in courtship violence victimization. Family Relations. 1986;35:383–388. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 5th ed. Authors; Los Angeles, CA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- NOVA Research Company . Questionnaire Development System [Computer software] Author; Bethesda, MD: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Orcutt HK, Garcia M, Pickett SM. Female-perpetrated intimate partner violence and romantic attachment style in a college student sample. Violence & Victims. 2005;20:287–302. doi: 10.1891/vivi.20.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL. Multiple imputation: A primer. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 1999;8:3–15. doi: 10.1177/096228029900800102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrondal A, Rabe-Hesketh S. Generalized latent variable modeling: Multilevel, longitudinal, and structural equation models. Chapman & Hall/CRC; Boca Raton, FL: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens J. Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences. 4th ed. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Gelles RJ. Physical violence in American families: Risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8,145 families. Transaction Publisher; New Brunswick, NJ: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2) Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Warren WL. The Conflict Tactics Scales handbook. Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GL, Meehan JC, Moore TM, Morean M, Hellmuth J, Follansbee K. Examining a conceptual framework of intimate partner violence in men and women arrested for domestic violence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:102–112. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GL, Moore TM, Gordon KC, Hellmuth JC, Ramsey SE, Kahler CW. Reasons for intimate partner violence perpetration among arrested women. Violence Against Women. 2006;12:609–621. doi: 10.1177/1077801206290173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TP, Meese KJ, Swan SC, Mazure CM, Snow DL. Precursors and correlates of women’s violence: Child abuse traumatization, victimization of women, avoidance coping, and psychological symptoms. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2005;29:290–301. [Google Scholar]

- Swan SC, Gambone LJ, Caldwell JE, Sullivan TP, Snow DL. A review of research on women’s use of violence with male intimate partners. Violence and Victims. 2008;23:301–314. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.3.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan SC, Gambone LJ, Fields AM, Sullivan TP, Snow DL. Women who use violence in intimate relationships: The role of anger, victimization, and symptoms of posttraumatic stress and depression. Violence and Victims. 2005;20:267–285. doi: 10.1891/vivi.20.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan SC, Snow DL. A typology of women’s use of violence in intimate relationships. Violence Against Women. 2002;8:286–319. doi: 10.1177/1077801206293330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan SC, Snow DL. Behavioral and psychological differences among abused women who use violence in intimate relationships. Violence Against Women. 2003;9:75–109. [Google Scholar]

- Swan SC, Snow DL. The development of a theory of women’s use of violence in intimate relationships. Violence Against Women. 2006;12:1026–1045. doi: 10.1177/1077801206293330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan SC, Sullivan TP. The Motivations for Violence Scale. Yale University; New Haven, Connecticut: 2002. Unpublished measure. [Google Scholar]

- Temple JR, Weston R, Marshall LL. Physical and mental health outcomes of women in nonviolent, unilaterally violent, and mutually violent relationships. Violence & Victims. 2005;20:335–359. doi: 10.1891/vivi.20.3.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, VanZile-Tamsen C, Livingston JA, Koss MP. Assessing women’s experiences of sexual aggression using the Sexual Experiences Survey: Evidence for validity and implications for research. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2004;28:256–265. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SP. Women’s anger, aggression, and violence. Health care for women international. 2005;26:504–522. doi: 10.1080/07399330590962636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson B, Borrello GM. The importance of structure coefficients in regression research. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1985;45:203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson B, Daniel LG. Factor analytic evidence for the construct validity of scores: A historical overview and some guidelines. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1996;56:197–208. [Google Scholar]

- Tolman RM. The validation of the psychological maltreatment of women inventory. Violence and Victims. 1999;14:25–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walley-Jean JC, Swan SC. Motivations and justifications for partner aggression in a sample of African-American college women. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, & Trauma. in press. [Google Scholar]