Abstract

The current study examined the efficacy of cognitive therapy (CT) in reducing symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Twenty-nine individuals with OCD were assigned according to therapist availability to a 12-week wait period or the immediate start of 22 sessions (over 24 weeks) of flexible, modular CT. After 12 weeks of treatment, the CT group, but not the wait-list group, exhibited significant improvement in OCD symptoms. The combined sample of patients who underwent 24 weeks of CT improved significantly from pre- to post-treatment and symptoms remained significantly improved at 3-month follow-up. OCD symptoms rose slightly between posttreatment and 12-month follow-up, but, remained significantly lower than at pretreatment. Overall, modular CT appears to be an effective and acceptable treatment for OCD.

Keywords: obsessive-compulsive disorder, cognitive therapy, wait-list controlled trial, modular treatment, behavior therapy

The most commonly delivered, empirically supported treatments for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) are psychopharmacological treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or clomipramine and behavior therapy (BT) with exposure and response prevention techniques during which patients are repeatedly exposed to anxiety provoking stimuli and prevented from engaging in rituals. Exposure and response prevention is based on an empirically supported model that rituals decrease discomfort in the short-term but reinforce obsessive anxiety in the long-term. These treatments are unquestionably beneficial for many OCD patients (e.g., Abramowitz, 1997; Foa et al., 2005). However, not all patients respond. Additionally many OCD patients refuse or discontinue psychopharmacological treatments because they are unable or unwilling to tolerate medication side effects, and many refuse or withdraw from BT, unwilling to tolerate the time intensive and anxiety provoking exposure exercises (Franklin & Foa, 1998). Hence there is a clear need for effective and acceptable treatment alternatives for OCD. Cognitive approaches offer some promise as they may be less stressful for patients and may therefore have lower refusal rates than intensive forms of BT or pharmacotherapy. Furthermore, as they can be conducted in the therapist's office and in 50–60 minute sessions, they may be more acceptable to therapists as well as managed health care providers.

According to cognitive models of OCD (e.g., Freeston, Rhéaume, & Ladouceur, 1996; Rachman, 1997; Salkovskis, 1989), intrusive thoughts are normal phenomena experienced universally by people with and without OCD (e.g., Rachman & de Silva, 1978). What distinguishes people with OCD from those without is not the experience of intrusive thoughts per se, but rather, OCD patients' beliefs about the presence or significance of intrusive thoughts. Whereas most people simply dismiss intrusive thoughts as transient and unimportant, individuals with OCD ascribe inordinate importance to them. The belief that intrusive thoughts are dangerous generates great anxiety and provokes compensatory rituals to reduce the likelihood of perceived danger or avoidance of situations that might trigger intrusive thoughts.

As described in standard texts on cognitive therapy (e.g., Beck, 1995; Wells, 1997), cognitive therapists help patients identify and modify distorted beliefs. Using techniques such as Socratic questioning, therapists assist patients in evaluating the validity and the utility of abiding by their beliefs that engender anxiety, compulsions, and avoidance behaviors. Within the context of belief-focused work, therapists occasionally ask patients to conduct behavioral experiments, designed to test their distorted hypotheses about what might happen were they to refrain from ritualizing. Such experiments are brief and only done to illustrate a particular point, such as testing whether a negative prediction comes true and are one of many CT strategies. Cognitive therapy does not require prolonged exposure and response prevention exercises to induce habituation to anxiety response and therefore is different from the widely used exposure and response prevention treatments for OCD.

Belief domains identified by the Obsessive Compulsive Cognition Working Group (OCCWG, 1997) include perfectionism, tolerance for uncertainty, responsibility, estimation of threat, control of thoughts, and importance of thoughts. Early CT studies suggested the effectiveness of CT that targeted belief domains of responsibility, threat estimation, and overimportance of thoughts in reducing OCD symptoms (e.g., Cottraux et al., 2001; van Oppen et al., 1995). Van Oppen and colleagues (1995) conducted a controlled trial randomly assigning 28 OCD patients to CT and 29 to BT using self-exposures. Patients were not included if they had only obsessions without overt rituals, or if they had received cognitive or behavioral treatment in the past 6 months. Patients in the CT group received no prolonged exposure but did engage in some behavioral experiments to test dysfunctional assumptions. The primary cognitive technique used was Socratic dialogue (e.g., Beck, Emery, & Greenberg, 1985). The results suggested that CT was at least as effective for OCD as ERR Cottraux and colleagues (2001) conducted a similar clinical trial directly comparing CT (n = 32) to BT (n = 33) for OCD. Their results suggested that both treatments were equally effective in reducing OCD symptoms, although CT decreased depressive symptoms more quickly than did BT. More recently, Whittal, Thordarson, and McLean (2005) compared cognitive therapy that targeted all six belief domains underscored by the OCCWG and included behavioral experiments (n = 30) to traditional exposure and response prevention therapy (n = 29). Results at posttreatment and 3 months following suggested that CT was at least as efficacious as exposure and response prevention therapy.

Our group conducted an open trial with 15 patients who underwent 14 CT sessions (Wilhelm et al., 2005). The CT, like Whittal and colleague's treatment, targeted the six OCCWG belief domains, as well as two additional belief domains related to fears of positive experiences and fears about the consequences of experiencing anxiety, both common in, although not exclusive to, OCD (Wilhelm & Steketee, 2006). Additionally, the CT was administered in a flexible, modular format, which enabled us to target the belief domains most relevant for each patient, depending on the patient's specific symptoms. This unique aspect of the CT treatment not only allowed the therapists to use a standardized, therapeutic manual (Wilhelm & Steketee, 2006), but also allowed them to use a case-formulation-driven approach recommended by Persons (2006) for its flexibility and applicability with complex cases. Thus treatment was tailored to individual patients' symptoms and beliefs based on their idiographic data (i.e., particular belief domains that caused them difficulty). Therapists were prohibited from using any prolonged exposure or response prevention exercises but could and did use behavioral experiments to test patients' hypotheses. Results suggested that CT was effective in reducing OCD and depressive symptoms in OCD patients with and without overt compulsions (Wilhelm et al., 2005).

The current study of CT for OCD replicates and expands upon our previous open trial of flexible, modular CT and is the second test of our widely used published treatment manual (Wilhelm & Steketee, 2006). It included a wait-list control condition to determine whether active treatment is superior to treatment gains afforded by the passage of time or other extraneous variables (e.g., history, maturation, testing). Like Whittal and colleagues, we examined effects at posttreatment and 3-month follow-up. Additionally, we included a 12-month follow-up assessment to further evaluate the stability of treatment effects. Lastly, the current study also examined treatment feasibility via measures of therapist adherence and competence and also acceptability, via a measure of patient satisfaction.

Methods

Participants

Participants were primarily recruited at the Massachusetts General Hospital OCD Clinic, through posted flyers in the Boston communities. However, two of the enrolled patients were recruited through the University of Virginia because the fifth author relocated there, from MGH, during the course of the study. All participants were age 18 or older, met American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.) criteria for a primary diagnosis of OCD, and had Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive scale scores of >16. Individuals with primary hoarding were not admitted into the study. Individuals were ineligible if they reported current suicidal or psychotic symptoms or other features necessitating psychiatric hospitalization, Tourette's Disorder, or showed evidence of mental retardation, dementia, brain damage, or other severe cognitive dysfunction. We also excluded those who were currently engaged in psychotherapy, had previously received CT for OCD, or had been unsuccessfully treated with an adequate trial (10 or more sessions) of BT. The latter two exclusion criteria were required by The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) reviewers to avoid initial testing of the efficacy of this new treatment in a treatment resistant sample. Individuals receiving psychopharmacological treatment could participate if they had been stably on or off medication for at least 2 months preceding study enrollment and remained stable throughout the trial.

Of 31 participants who enrolled, two were found ineligible after starting treatment and were removed from the trial. The 29 eligible participants (15 women) had a mean age of 33.4 (SD = 11.2; range = 18 to 68), and a mean Y-BOCS score of 25.6 (SD = 4.8). Twelve patients had concurrent DSM-IV comorbid conditions including major depression (n = 7), generalized anxiety disorder (n = 4), social phobia (n = 3), specific phobia (n = 2), body dysmorphic disorder (n = 1), and dysthymia (n = 1). Fourteen patients were taking psychotropic medication: clonazepam (n = 4), fluvoxamine (n = 3), citalopram (n = 2), escitalopram (n = 2), paroxetine (n = 2), sertraline (n = 2), alprazolam (n = 1), buproprion (n = 1), clomipramine (n = 1), fluoxetine (n = 1), and venlafaxine (n = 1).

Measures

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV-Patient Version (SCID-P; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1995) is a widely used, semistructured interview that assesses DSM–IV Axis I psychiatric diagnoses.

The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive scale (Y-BOCS; Goodman et al., 1989) is a 10-item scale that assess the severity of obsessions as reflected by the degree to which symptoms consume time, cause distress, and interfere with functioning, and are experienced as out of the patient's control. The Y-BOCS demonstrates sensitivity to treatment effects (deVeaugh-Geiss, Landau, & Katz, 1989) and excellent interrater reliability (Goodman et al, 1989).

The Clinical Global Improvement scale (CGI; Guy, 1976) is a global rating scale commonly used in clinical trials. Clinicians rate patient improvement, using a scale that ranges from 1 (very much improved) to 7 (very much worse).

The Obsessive Beliefs Questionnaire (OBQ; OCCWG, 1997) is an 87-item self-report instrument that assesses general beliefs and attitudes in the six belief domains underscored by the Obsessive Compulsive Cognitions Working Group as highly influential in the development and maintenance of OCD. The OBQ yields a total score and subscores for each of six belief domains (beliefs about the importance of thoughts, beliefs about the ability–necessity to control one's thoughts, beliefs about inflated personal responsibility, beliefs concerning overestimation of danger, beliefs about the ability and need to be perfect, and beliefs about the need for absolute certainty). For this study we added two additional subscales to the OBQ to measure fears of positive experiences and concerns about the consequences of anxiety (available from the authors upon request).

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck & Steer, 1987) is a well-known, 21-item, self-report measure of the severity of depressive symptoms.

The Client Satisfaction Inventory (CSI; McMurtry & Hudson, 2000) is a 9-item, self-report measure that assesses patient perception of treatment quality and effectiveness.

Procedures

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by institutional review committees at participating institutions. All participants provided written informed consent. The study was conducted between January 2002 and May 2005.

Potential participants were screened by telephone and, if appropriate, invited for an in-person assessment to determine study eligibility. Invited participants completed the SCID-P and Y-BOCS interviews with independent raters who were doctoral level clinicians or advanced doctoral psychology students. All assessments were audiotaped. Interrater reliability, based on a rating of 20% of the taped assessments by an independent doctoral level clinician, was high for both SCID-P (kappa = 1.00) and Y-BOCS (Pearson's r = 0.97). Following the initial baseline interview assessment, participants completed self-report questionnaires.

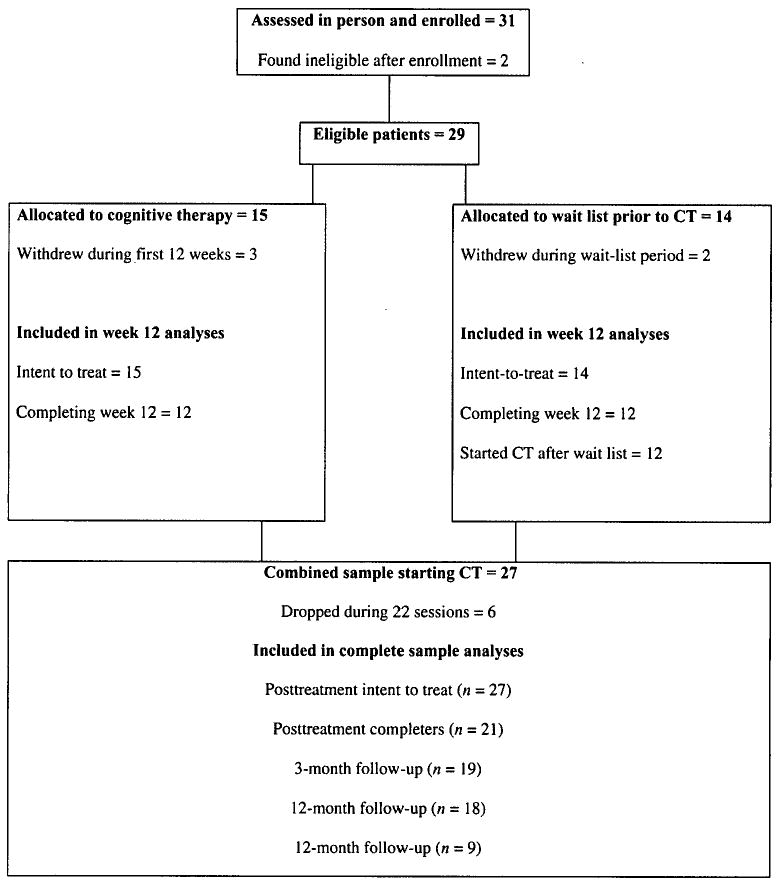

Of 29 eligible patients, 15 (9 women) were assigned to begin the treatment immediately following enrollment (CT group) and 14 (6 women) were assigned to begin the treatment after a 12-week wait-list period (WL group; see Figure 1). Patients were asked to wait for 12 rather than 24 weeks, the time frame for CT, for ethical reasons. Assignments were made based on a combination of therapist availability and the need to balance assignments to conditions. Thus, while not strictly random, the assignment to treatment was not based on patient characteristics, symptomatology, or therapist–patient matching.

Figure 1.

Participant flow through the study.

The CT participants began treatment following baseline assessment, which served as their pretreatment assessment. After 12 weeks of wait period, WL participants completed a second assessment (Y-BOCS, CGI, OBQ, BDI), which also served as their pretreatment assessment. During and after the treatment course, CT and WL patients followed the same assessment schedule, completing the Y-BOCS, CGI, OBQ, and BDI following sessions 12, 22 (posttreatment), and 3- and 12-month follow-up. The CSI was given after session 22 (posttreatment).

Treatment

The treatment, described in detail in Wilhelm and Steketee (2006), comprised 22 sessions of Beckian therapy targeting misinterpretations associated with beliefs in the six domains identified by the OCCWG (1997) and additional beliefs regarding fears of positive experiences and tolerance for anxiety. Sessions 1 through 4 were devoted to assessment and psychoeducation; 5 through 20 to the implementation of treatment modules relevant to each patients' particular beliefs; and 21 and 22 to relapse prevention strategies. The first session was 90 minutes in length and all remaining sessions were 60 minutes long. Sessions 1–20 were conducted weekly; sessions 21 and 22 were spaced 2 weeks apart.

During the first four sessions, clinicians conducted a thorough assessment of patients' OCD symptoms, psychiatric and social history, and OCD-relevant cognitive misinterpretations. Following this, clinicians provided psychoeducational material on the cognitive model of OCD and cognitive misinterpretations common in OCD, and discussed belief domains in which individual patients' misinterpretations are likely to occur. Clinicians assisted patients in completion of 5- and 7-column thought records to illustrate the model.

During weeks 5–20, therapists used general and domain-specific CT techniques from modules selected to match each patient's distressing interpretations and belief domains. The OBQ, as modified for the current study, was administered before treatment and monthly during treatment so module selection was continuously informed by the patient's most problematic belief domains. Module length and content varied according to the misinterpretations that were most problematic for each individual patient. Over 16 weeks, patients received instruction in four to eight treatment modules, each lasting from two to four sessions. On average, patients covered four to five treatment modules.

The final two sessions focused on relapse prevention. The clinician and patient reviewed CT techniques learned over the course of treatment, along with common and idiopathic triggers for OCD symptoms (e.g., stress, depressed mood). Together they generated strategies to prevent and address possible resurgences in OCD symptoms. Clinicians also helped patients plan adaptive activities to fill time previously devoted to ritualizing.

Treatment was administered by advanced doctoral students in psychology or by postdoctoral clinicians in training. All clinicians were supervised weekly by Drs. Wilhelm and Steketee who listened to audiotaped therapy sessions and provided feedback. Adherence to treatment procedures and therapist competence were rated by an independent doctoral level clinician on 6-point scales ranging from 0 “not at all competent–adherent” to 5 “completely competent–adherent.” The mean competence rating was 4.97. Mean adherence ratings for all belief domains ranged from 4.1 to 4.9, suggesting the therapists adhered well to the treatment protocol.

Analysis

We first evaluated the benefits of 12 weeks of active CT versus no treatment. Accordingly, CT patients (after receiving 12 weeks of treatment) were compared with WL patients (who were about to begin their treatment 12 weeks after enrollment). We then evaluated the benefits of 22 sessions of CT in the combined sample of participants (immediate CT + WL patients). Maintenance of treatment gains in the combined sample was analyzed by comparing symptom severity scores at posttreatment with scores obtained at 3- and 12-month follow-up.

Results

CT versus WL Condition

CT patients and wait-list patients did not differ significantly on baseline measures of OCD symptom severity on the Y-BOCS (CT M = 26.5, SD = 4.7; Wait list M = 24.6, SD = 4.7); t(27) = 1.09, p = .28, d1 = .41) or BDI (CT M = 14.3, SD = 9.8; Wait list M = 10.9, SD = 7.0; t(27) = 1.05, p = .30, d = .39). Three CT patients terminated the study before completing week 12 assessments: one patient withdrew after two sessions because the 2-hour commute to the clinic became too burdensome, one withdrew after 12 sessions due to a medical illness, and another stopped after 12 sessions to pursue psychopharmacological treatment at her mother's suggestion. Two WL participants discontinued before week 12, one due to a pending move and another for unknown reasons.

Because five patients withdrew from the study within the first 12 weeks following enrollment, we conducted between group analyses twice, first for completers only (CT = 12, WL = 12) and again for the entire intent-to-treat sample, carrying forward data from the last assessment. In both analyses, 12 weeks of CT was significantly more effective than wait list in reducing OCD symptoms. Relative to WL patients, CT patients exhibited significantly greater decreases after 12 weeks in Y-BOCS total scores, t(22) = 4.7, p < .001, d = 1.91 (intent-to-treat t(27) = 3.7, p = .002, d = 1.34). Within group comparisons further indicated that CT patients exhibited significant decreases in Y-BOCS total scores: Mdecrease = 9.92, SD = 6.7, t(11) = 5.1, p < .001, d2 = 1.96 (intent to treat t(14) = 3.8, p = .002, d = 1.50). In contrast, wait-list patients exhibited no significant decline: Mdecrease = −0.46, SD = 3.8; t(11) = .4, p = .685, d = .11 (intent to treat t(13) = 0.42, p = .682, d = 0.08).

CT Outcomes for the Combined Sample

In the section below we report results for our combined CT sample consisting of 27 patients. Fifteen patients of this sample had begun CT immediately, and 12 patients started CT after having been on the wait list. Of those who began CT immediately, four terminated before completing all 22 sessions (this includes the three patients who dropped before week 12 assessments described above, and one additional patient who dropped after week 12). In the group that started CT after the wait-list period, two patients dropped from treatment. We conducted the primary analyses twice, first for completers only (n = 21), and then for the intention-to-treat sample, carrying forward data from their last assessment (n = 27). In both cases, paired t-tests revealed significant pre- to posttreatment decreases in Y-BOCS total scores, t(20) = 9.7, p < .001, d = 3.25; intent-to-treat t(26) = 6.6, p < .001, d = 2.14, and depressive symptoms from the BDI, t(20) = 2.8, p = .011, d = .40; intent-to-treat t(26) = 2.2, p = .04, d = .29. See Table 1 for means and standard deviations for completer analyses.

TABLE 1. Outcomes on Measures of OCD, Depression, and Obsessive Beliefs for the Complete Sample.

| Posttreatment | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Pretreatment | Posttreatment | Significance level and effect size | ||||

| n | M | SD | M | SD | P | d | |

| Y-BOCS | 21 | 27.1 | 4.4 | 12.2 | 9.2 | <.001 | 3.25 |

| BDI | 21 | 12.3 | 10.3 | 8.0 | 9.1 | .01 | .40 |

| OBQ-87 | 21 | 335.0 | 96.0 | 217.1 | 125.8 | >.001 | 1.18 |

| 3-month follow-up | |||||||

| Measure | Posttreatment | 3-month follow-up | Significance level and effect size | ||||

| n | M | SD | M | SD | P | d | |

| Y-BOCS | 19 | 12.8 | 9.3 | 13.6 | 9.2 | .30 | .09 |

| BDI | 17 | 9.3 | 9.6 | 10.2 | 9.6 | .61 | .09 |

| OBQ-87 | 17 | 225.6 | 129.5 | 235.2 | 132.8 | .15 | .08 |

| 12-month follow-up | |||||||

| Measure | Posttreatment | 12-month follow-up | Significance level and effect size | ||||

| n | M | SD | M | SD | P | d | |

| Y-BOCS | 18 | 12.4 | 9.5 | 14.8 | 10.1 | .04 | .24 |

| BDI | 17 | 7.4 | 8.7 | 7.2 | 7.4 | .88 | .13 |

| OBQ-87 | 16 | 202.1 | 126.4 | 210.3 | 126.1 | .17 | .06 |

Note. Y-BOCS = Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive scale, BDI = Beck Depression Inventory, OBQ = Obsessive Beliefs Questionnaire.

The mean percentage decrease on the Y-BOCS was 57% in completers and 43% in the intent-to-treat sample. Classification of patients as responders or nonresponders, according to posttreatment CGI scores of “much improved” or “very much improved” indicated that 81% of completers and 63% in the entire intent-to-treat sample responded to CT.

To examine whether patients who completed treatment would exhibit decreases in the severity of maladaptive beliefs targeted by our treatment, we first examined pre- and posttreatment differences in total OBQ scores as derived from the original OBQ-87. Means appear in Table 1. We then examined differences in the additional subscales regarding fears of positive experiences and consequences of anxiety used in this study. Paired t-tests revealed significant decreases in OBQ-87 total scores, t(20) = 4.2, p < .001, d = 1.18, fear of positive experiences, t(20) = 3.0, p = .008, d= 0.61, and fear of consequences of anxiety, t(20) = 4.0, p = .001, d = 1.04.

Posttreatment CSI scores revealed that patients were 94.6 % (SD = 10.5%) satisfied with treatment received, suggesting that the treatment was highly acceptable.

Follow-Up

Follow-up data are provided in Table 1. We were unable to obtain 3-month follow-up assessments from 2 of the 21 treatment completers (both responders). Among the 19 patients who completed the 3-month assessment, neither Y-BOCS total score [t(18) = 1.1, p = .30, d = .09], BDI [t(16) = .51, p = .61, d = .09], nor OBQ scores [t(16) = 1.53, p = .15, d = .08, fear of positive experiences scores, t(16) = 1.38, p = .19, d = 0.16, and fear of consequences of anxiety scores t(16) = 0.11, p = .91, d = 0.02]3 changed significantly between posttreatment and 3-month follow-up. We were unable to obtain 12-month follow-up assessment from 3 of the 21 treatment completers. (All were responders at posttreatment). Among the 18 who completed 12-month assessments, Y-BOCS symptom severity scores increased slightly compared to posttreatment [t(17) = 2.2, p = .04, d = .24], but still fell below the clinical range of OCD symptom severity (M = 14.8; SD = 10.1). However, Y-BOCS total follow-up scores remained significantly lower than at pretreatment [t(17) = 6.7, p < .001, d = 2.47]. BDI scores did not change significantly during this time period [t(16) = .16, p = .88, d = .13], but they no longer differed significantly from pretreatment BDI scores [t(16) = 1.9, p = .072, d = .40]. The OBQ total scores did not changed significantly from posttreatment [t(15) = 1.5, p = .17, d = .06, fear of positive experiences scores, t(15) = 1.34, p = .20, d = 0.18, and fear of consequences of anxiety scores t(15) = 1.13, p = .28, d = 0.12].

Discussion

These data suggest that our modular CT targeting multiple belief domains is effective in reducing OCD symptoms. This was evident in the wait-list comparison after only 12 weeks and also in the combined sample after 24 weeks (22 treatment sessions). Treatment gains were maintained after 3 months, and OCD symptoms were still in the mild range at the 12-month follow-up; specifically, mean Y-BOCS scores at this time still remained significantly improved over baseline, providing preliminary evidence for CT's long-term impact on reducing OCD symptoms. Depressive symptoms were still in the mild range at the 12-month follow-up, but BDI scores no longer significantly differed from pretreatment BDI scores.

The mean percentage pre- to posttreatment decrease in Y-BOCS scores (57%) and related effect size estimate (d = 3.25) in the current study accord with those of three previous investigations of CT in which decreases in Y-BOCS symptoms ranged from 44% to 55% and d values ranged from 1.91 to 2.90 (see Whittal et al., 2005). The posttreatment response rates in the current study (81% in the completer group and 63% in the intent-to-treat group) are also comparable to those reported by Foa et al. (2005) in their large scale, multisite, randomized, placebo-controlled study examining BT, clomipramine, and combined BT and clomipramine treatment for OCD. In that trial, Foa and colleagues reported CGI response rates of 86% for completers and 62% for intent-to-treat patients receiving BT, 48% and 42%, respectively, for patients receiving clomipramine, and 79% and 70%, respectively, for those in combined BT and medication treatment. Thus, the results of our trial add to a growing body of research suggesting that CT may be as effective as other commonly accepted gold standard treatments for OCD.

Cognitive therapy was also effective in reducing obsessive beliefs, and these decreases remained stable 12 months after the completion of the treatment, suggesting that CT for OCD reduces maladaptive beliefs in both the short- and long-term. Further, unlike Foa and colleagues' study (2005), we included patients with comorbid major depression (7 of our sample had this concurrent diagnosis). Given that 41.4% of our sample suffered from common comorbid disorders, the positive outcomes suggest that CT may be an effective treatment option even for patients with significant comorbidity.

The generalizability of CT is also suggested by the convenient in-office delivery of our protocol. Research suggests that effective BT protocols often require extended, off-site sessions. For example, the BT delivered by Foa and colleagues (2005) consisted of two information gathering sessions and about 40 hours of treatment, including home visits. Our CT protocol also included two information gathering sessions, but was administered entirely in therapists' offices and consisted of 22.5 hours of treatment. Thus, CT may be a feasible option for therapists working with a limited number of treatment sessions under managed care and other pragmatic constraints (Fama & Wilhelm, 2005).

Results also indicate that CT is an acceptable treatment. No eligible patient who was offered CT refused it. Two wait-list patients terminated before starting treatment, but one of these was due to an unexpected pending move and we therefore do not consider him a treatment refuser. The other terminated for unknown reasons. If we consider him a treatment refuser, the refusal rate for the current study would be 3.5%, a rate slightly lower than in Foa and colleagues' (2005) combined treatment condition (6.1%), and considerably lower than their BT (21.6%) and clomipramine (23.4%) conditions. A larger trial will be necessary to determine the refusal rate for CT more accurately. Our patient withdrawal rate (22.2%) is comparable to those reported by Foa and colleagues (2005) for patients in their BT (27.6%) and clomipramine (25%) conditions and lower than that of patients in their combined treatment arm (38.7%).

Several potential limitations deserve mention. First, our relatively small sample size may have limited our ability to detect significant differences in some of our analyses. Although we provide effect size estimates to partially address this concern, future research with larger samples would be useful. Additionally, because of our small sample size, we chose not to correct for our use of multiple t-tests, leaving open the possibility that some analyses may have yielded spurious results. Second, because of ethical concerns about leaving wait-list patients untreated for 24 weeks, the wait-list condition lasted for just 12 weeks. So, although the length of our full treatment was 24 weeks, based on our CT versus wait-list analyses, we are only able to conclude that 12 weeks of active treatment is more effective than 12 weeks of no treatment. (However, it seems unlikely that the group of patients who remained highly symptomatic for 12 weeks would spontaneously improve over the next 12 had we extended the wait-list period for a full 24 weeks.) Third, although our wait-list design enabled us to compare the effects of active treatment with the course of those with the illness who had gone untreated, it precludes conclusions about whether improvement was the result of nonspecific therapeutic factors, like therapist attention. Future research exploring the benefits of modular CT compared with BT and medication is needed. Dismantling studies comparing CT without behavioral experiments to “purer” forms of CT and BT could also provide information about the mechanisms of these treatments.

The modular approach used in the current study allowed the flexible use of a standardized protocol that proved effective overall. Unfortunately, the current design did not permit us to directly investigate the effects of the individual modules that were used. Future research to test the effects of specific modules could inform us about the elements of cognitive therapy for OCD that are most and least effective and whether certain modules are more effective for patients with specific symptom subtypes.

In general, the current results, in combination with those from a growing body of research on CT for OCD, suggest that CT is an effective treatment for OCD. Our results also suggest that CT is an acceptable treatment for patients, who reported high satisfaction with the treatment we administered. Cognitive therapy may be especially promising for patients who refuse or cannot access behavioral treatment or tolerate medication. Future research should investigate its efficacy in patients who are unresponsive to these treatment options.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by an NIMH grant (MH58804) awarded to the first author. We thank Drs. Anne Chosak and Kimberly Wilson for their help with this project. The authors have no conflict of interest directly relevant to this work other than royalties received from their CT treatment manual published by New Harbinger Publications.

Footnotes

Effect size d for between group comparisons calculated as: d = M1 − M2/SD pooled, where SD pooled = SD1 + SD2/2 (Cohen, 1988).

Effect size d for paired comparisons, calculated with correction for small sample bias as: d = g[1 − (3/(4(n − 1) − 1)], where g = Mpre − Mpost/SDpre (Becker, 1988).

Slight differences in sample sizes in some analyses reported in text and in tables are due to missing questionnaire data.

Contributor Information

Sabine Wilhelm, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

Gail Steketee, Boston University.

Jeanne M. Fama, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

Ulrike Buhlmann, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

Bethany A. Teachman, University of Virginia.

Elana Golan, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

References

- Abramowitz JS. Effectiveness of psychological and pharmacological treatments for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A quantitative review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:44–52. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Emery G, Greenberg RL. Anxiety disorders and phobias: A cognitive perspective. New York: Basic Books; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck depression inventory manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Beck JS. Cognitive therapy: Basics and beyond. New York: Guilford; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Becker BJ. Synthesizing standardized mean-change measures. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology. 1988;41:257–278. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cottraux J, Note I, Yao SN, Lafont S, Note B, Mollard E, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive therapy versus intensive behavior therapy in obsessive compulsive disorder. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2001;70:288–297. doi: 10.1159/000056269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVeaugh-Geiss J, Landau P, Katz R. Treatment of OCD with clomipramine. Psychiatric Annals. 1989;19:97–101. [Google Scholar]

- Fama JM, Wilhelm S. Formal cognitive therapy: A useful ingredient in the treatment of OCD. In: Abramowitz JS, Houts AC, editors. Handbook of OCD: Concepts and controversies in obsessive-compulsive disorder. New York: Springer Publishing; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM–IV Axis I Disorders—Patient Version. 2nd. New York: Biometrics Research Department; New York Psychiatric Institute: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Liebowitz MR, Kozak MJ, Davies S, Campeas R, Franklin ME, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of exposure and ritual prevention, clomipramine, and their combination in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162(Suppl 1):151–161. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin ME, Foa EB. Cognitive-behavioral treatments for obsessive-compulsive disorder. In: Nathan PE, Gorman JM, editors. A guide to treatments that work. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Freeston MH, Rhéaume J, Ladouceur R. Correcting faulty appraisals of obsessional thoughts. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34:433–446. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Fleischman RL, Hill CL, et al. The Yale-Brown obsessive-compulsive scale: Development, use, and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1989;46:1006–1011. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110048007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W. ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology (rev ed) Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health; 1976. cited in DHEW; Pub. No. [ADM] 76-338. [Google Scholar]

- McMurtry SL, Hudson WW. The client satisfaction inventory: Results of an initial validation study. Research on Social Work Practice. 2000;10:644–663. [Google Scholar]

- Obsessive Compulsive Cognition Working Group. Cognitive assessment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35:667–681. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persons JB. Case formulation-driven psychotherapy. Clinical Psychology Science and Practice. 2006;13:167–170. [Google Scholar]

- Rachman SA. A cognitive theory of obsessions. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35:793–802. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachman S, de Silva P. Abnormal and normal obsessions. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1978;16:233–238. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(78)90022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salkovskis PM. Cognitive-behavioural factors and the persistence of intrusive thoughts in obsessional problems. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1989;27:677–682. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(89)90152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Oppen P, de Hann E, van Balkom AJLM, Spinhoven P, Hoogduin K, van Dyck R. Cognitive therapy and exposure in vivo in the treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1995;33:379–390. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00052-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells A. Cognitive therapy of anxiety disorders: A practice manual and conceptual guide. New York: Wiley; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Whittal ML, Thordarson DS, McLean PD. Treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: Cognitive behavior therapy vs. exposure and response prevention. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43:1559–1576. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm S, Steketee G. Cognitive therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A guide for professionals. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm S, Steketee G, Reilly-Harrington NA, Deckersbach T, Buhlmann U, Baer L. Effectiveness of cognitive therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: An open trial. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2005;19:173–179. [Google Scholar]