Abstract

The majority of mammalian genes produce multiple transcripts resulting from alternative splicing (AS) and/or alternative transcription initiation (ATI) and alternative transcription termination (ATT). Comparative analysis of the number of alternative nucleotides, isoforms, and introns per locus in genes with different types of alternative events suggests that ATI and ATT contribute to the diversity of human and mouse transcriptome even more than AS. There is a strong negative correlation between AS and ATI in 5′ untranslated regions (UTRs) and AS in coding sequences (CDSs) but an even stronger positive correlation between AS in CDSs and ATT in 3′ UTRs. These observations could reflect preferential regulation of distinct, large groups of genes by different mechanisms: 1) regulation at the level of transcription initiation and initiation of translation resulting from ATI and AS in 5′ UTRs and 2) posttranslational regulation by different protein isoforms. The tight linkage between AS in CDSs and ATT in 3′ UTRs suggests that variability of 3′ UTRs mediates differential translational regulation of alternative protein forms. Together, the results imply coordinate evolution of AS and alternative transcription, processes that occur concomitantly within gene expression factories.

Keywords: alternative splicing, alternative transcription initiation, alternative transcription termination, gene expression factories

Introduction

The extraordinary complexity of transcriptomes that underpins the structural and functional diversity of mammalian proteomes is created by alternative splicing (AS) and alternative transcription (Sultan et al. 2008; Wilhelm et al. 2008). Transcriptome analysis shows that the majority of protein-coding genes in mammals undergo AS whereby the same sequence belongs to an exon in one subset of transcripts of the given gene locus and to an intron in another subset of transcripts (Blencowe 2006; Kim et al. 2008). Indeed, the latest estimates using high-throughput sequencing methods indicate that up to 95% of multiexon human genes are subject to AS and reveal approximately 100,000 major AS events (Pan et al. 2008). In addition, recent studies of mammalian gene expression point to the wide spread of alternative initiation and alternative termination of transcription (ATI and ATT, respectively) and importance of these events in the generation of the transcriptome diversity (Landry et al. 2003; Shabalina and Spiridonov 2004; Baek et al. 2007; Ma et al. 2009; Yamashita et al. 2010).

The prevalence and functional significance of different types of alternative events (AEs) differs between parts (functional domains) of transcripts. Thus, AS is common in the 5′ untranslated regions (5′ UTRs) and coding sequences (CDSs), with a significantly greater fraction of nucleotides involved in AS in the 5′ UTRs compared with the CDS (Resch et al. 2004, 2009; Cenik et al. 2010). In contrast, AS is rare in 3′ UTRs given the overall low intron density in this region (Hong et al. 2006; Grillo et al. 2010). In contrast, ATI and ATT are confined, respectively, to the 5′ UTRs and 3′ UTR and the corresponding “grey areas,” the sequences that alternate between the CDS and UTRs in alternative transcripts.

Numerous biochemical and cytological experiments indicate that in eukaryotes transcription and mRNA processing including capping, splicing, and polyadenylation/cleavage form a network of elaborately regulated and coupled processes that occur together within nuclear “gene expression factories” (Bentley 2002, 2005; Maniatis and Reed 2002; Kornblihtt et al. 2004). These findings suggest intriguing possibility that AEs occurring at different levels of gene expression and transcript processing might not be independent.

Given the wide spread of AEs in mammalian genes and the increasingly apparent transcription-splicing coupling, we undertook a genome-wide survey of the relative contributions of different types of AEs to the diversity of the transcriptomes and the connections between alternative transcription and AS. The results reveal complex relationships that range from tight coupling to mutual exclusion and substantially differ within and between functional domains of mammalian transcripts.

Materials and Methods

Alternative Transcript Data Sets and Their Classification

We analyzed alternative transcripts from the human and mouse protein-coding genes deposited in two major databases: RefSeq and UCSC. Coordinates of the human (hg18) and mouse (mm9) transcripts, their structural domains, and transcript description were downloaded from the UCSC server (http://genome.ucsc.edu/). To be included in the analysis, transcripts had to meet the following criteria: 1) full-length isoforms should have supporting mRNA or cDNA evidence and 2) coding regions (CDS) should be annotated, and start and stop codon positions for CDS must be known.

Grouping Transcripts into Gene Loci

To assign alternative transcripts to the corresponding gene loci, we used two clustering methods: 1) by locus ID annotation (for the RefSeq database) and 2) by overlapping estimation of alternative isoforms using parameters for minimum overlap between 25% and 75% for coding regions (CDSs) and exons (Shabalina et al. 2010). We found that the requirement for a minimal 75% overlap between coding regions yielded conservative values closest to those obtained from the classification based on the locus ID annotation from the RefSeq database (supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online). The 75% threshold allowed us to exclude from consideration many overlapping genes and chimeric transcripts. The use of a 25% threshold instead of 75% did not significantly change the observed distribution of alternative nucleotides (supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online) and the correlations between AEs in different functional domains of transcripts. Therefore, we accepted a 75% threshold for both parameters: CDS overlap and exon overlap. Although some differences were observed in the proportion of AS and alternatively transcribed (AT) genes in RefSeq and UCSC databases, these criteria for CDS and exon overlapping yielded stable and reliable results for both databases.

When grouping transcripts to their gene loci, we excluded transcripts from opposite strands and transcripts that do not have any coding nucleotides in common. To group transcripts by coordinates, we first grouped all overlapping transcripts. Then, we subdivided a group into gene loci by picking a seed for a locus and testing whether to add each of the remaining transcripts. We added a new transcript to the locus if it had more than 75% of the CDS in common with every other transcript in the given locus on the same strand.

Subdividing Gene Loci into Functional Regions

Boundaries of gene functional domains were determined by combining the most upstream/downstream isoform coordinates and translation start and stop codon annotations for all isoforms mapped to a gene locus (Kondrashov and Shabalina 2002; Ogurtsov et al. 2008). For the purpose of this study, we considered five regions within a gene locus that are involved in the formation of alternative isoforms, as illustrated by figure 1: (1) 5′ UTR (area between the first transcription initiation site and the first translation start codon), (2) “5′ grey area” (between the first and the last translation start codons); (3) CDS (between the last translation start codon and the first translation stop codon); (4) “3′ grey area” (between the first and the last translation stop codons); and (5) 3′ UTR (area between the last translation stop codon and the last transcription termination site). The conservative criteria for classification of the functional domain and introduction of “grey” areas ensure that UTRs and protein-CDSs are excluded from the analysis of dual status gene regions. Only isoforms with reliable hits (E value < 10−4) against genomic sequences were considered for this analysis. Exon coordinates in our data were mostly clean with the exception of occasional adjacent exons, such that the last nucleotide of one immediately preceded the first nucleotide of the other; such adjacent exons were merged into one. For every transcript, we counted the number of exons and introns that belong to each of the five gene functional regions. We counted exons and introns located entirely within a functional region by adding 1 to the appropriate tally. For those exons that are partitioned between functional regions of a gene, the tally for each region was incremented proportionally to the fraction of the nucleotides that belonged to that region.

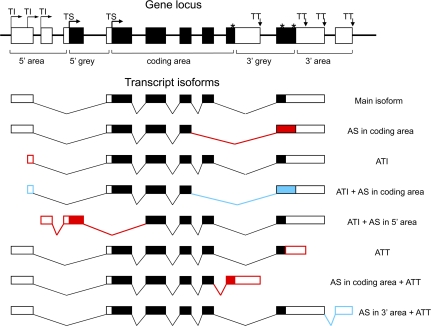

FIG. 1—

Anatomy of mammalian transcripts: functional domains, constitutive and alternative nucleotides, and AEs. TI, transcription initiation site; TS, translation initiation site; TT, transcription termination site; *, translation termination site. Protein-coding regions are filled. Frequent AEs and common combinations of AEs are shown in red. Rare AEs and avoided combinations of AEs are shown in blue.

Each nucleotide locus position was classified as constitutive (belongs to an exon in every isoform), intronic (does not belong to an exon in any of the isoforms), or alternative (all other positions that belong to an exon at least in one isoform of the given gene locus) positions.

Classification of Nucleotides Involved in Different Types of Alternative Events

Relationship of nucleotides to ATI, ATT, and AS was established by detailed analysis of all alternative isoforms transcribed from a gene locus. Alternative nucleotides in each transcript that belong to the first exon located between the most upstream and downstream transcription start sites were attributed to ATI. Similarly, alternative nucleotides in each transcript that belong to the last exon located between the most upstream and downstream transcription termination sites were attributed to ATT. The remaining alternative nucleotides were considered as resulting from AS. We evaluated relaxed (100–500,000 nt) and more stringent (300–50,000 nt) thresholds for differences between the positions of the upstream and downstream ATI (ATT) sites in gene loci and found that different thresholds yielded similar results (table 2, supplementary table S2A–B, Supplementary Material online). The results are presented for the 100 nt minimum and 500,000 nt maximum (table 2, supplementary table S2B, Supplementary Material online), as well as for the most conservative thresholds, 300 nt minimum and 50,000 nt maximum (supplementary table S2A, Supplementary Material online).

Table 2.

Numbers of Human Gene Loci Producing Transcript Isoforms with Alternative Events in Different Functional Domains (UCSC Database)

| Transcripts with AEs in Functional Domains |

||||||

| Transcript Group | 5′ UTR | 5′ grey | CDS | 3′ grey | 3′ UTR | AT Gene Loci |

| Total | 7,662 | 5,796 | 7,951 | 4,529 | 4,755 | 11,589 |

| 0.661 | 0.50 | 0.686 | 0.391 | 0.41 | 1 | |

| AS | 468 | 608 | 1,669 | 191 | 32 | 2,358 |

| 0.198 | 0.258 | 0.708 | 0.081 | 0.013 | 0.203 | |

| (ATT + AS) | 10 | 18 | 156 | 136 | 190 | 226 |

| 0.044 | 0.08 | 0.69 | 0.602 | 0.841 | 0.02 | |

| ATT | 130 | 166 | 1,778 | 1,680 | 1,833 | 1,833 |

| 0.071 | 0.091 | 0.97 | 0.917 | 1 | 0.158 | |

| (ATI + AS) | 2,266 | 1,263 | 837 | 77 | 7 | 2,327 |

| 0.974 | 0.543 | 0.36 | 0.033 | 0.003 | 0.201 | |

| ATI | 2,112 | 1,905 | 1,225 | 99 | 9 | 2,112 |

| 1 | 0.902 | 0.58 | 0.047 | 0.004 | 0.182 | |

| (ATI + AS) + (ATT + AS) | 98 | 67 | 69 | 71 | 78 | 109 |

| 0.899 | 0.615 | 0.633 | 0.651 | 0.716 | 0.009 | |

| (ATI + AS) + ATT | 1,208 | 705 | 1,000 | 1,081 | 1,254 | 1,254 |

| 0.963 | 0.562 | 0.797 | 0.862 | 1 | 0.108 | |

| ATI + (ATT + AS) | 133 | 103 | 99 | 89 | 115 | 133 |

| 1 | 0.774 | 0.744 | 0.669 | 0.865 | 0.011 | |

| ATI + ATT | 1,237 | 961 | 1,118 | 1,105 | 1,237 | 1,237 |

| 1 | 0.777 | 0.904 | 0.893 | 1 | 0.107 | |

NOTE.—The table includes all possible combinations of AEs in transcripts: Total, all types of AEs; (ATI + AS), ATI and AS in 5′ UTRs; (ATT + AS), ATT and AS in 3′ UTRs; ATI + (ATT + AS), ATT and AS in 3′ UTRs accompanied by ATI; (ATI + AS) + ATT, ATI and AS in 5′ UTRs accompanied by ATT; (ATI + AS) + (ATT + AS), ATI and AS in 5′ UTRs accompanied by ATT and AS in 3′ UTRs; ATI + ATT, ATI accompanied by ATT. The table shows the number and the fraction (italic) of each type of AEs in each of the functional domains of human transcripts. The fraction of gene loci for each subset patterns of AEs is shown in “italic and bold.”

As an additional control for the reliability of the AE classification, we compared the lists of gene loci from UCSC and RefSeq databases that are classified as employing ATI against the database of experimentally verified transcription start sites, DBTSS (Wakaguri et al. 2008). Approximately, 70% of gene loci from RefSeq, identified in our analysis as involved in ATI, were on the list of genes with alternative transcription starts from DBTSS database (supplementary table S3A, Supplementary Material online). The proportion of gene loci with experimentally validated ATI was somewhat lower for UCSC (supplementary table S3B, Supplementary Material online) than it was in the case of RefSeq, as one would expect given that many transcripts included in the UCSC database are predictions.

Gene Ontology Annotation

Functional annotation for human and mouse was downloaded from the Gene Ontology (GO) database (Harris et al. 2004). Starting with a total of 16,468 annotated human genes, GO annotations were mapped to 89% of the genes in the UCSC subsets. With 17,480 annotated mouse genes, GO annotations were mapped to 94% of the genes in the UCSC subsets. The GO terms associated with each group of human genes employing different types of AEs were identified and analyzed using the GoMiner program and the UniProtKB protein data set, false discovery rate (FDR) cutoff of 0.05, and 100 GoMiner runs to estimate FDR (Zeeberg et al. 2003). Keyword frequencies were tabulated for all analyzed subsets and normalized by the total numbers of genes in each set (Resch et al. 2009). P values were calculated using the χ2 test.

Results

Alternative and Constitutive Nucleotides in Different Functional Domains of Mammalian Transcripts

We performed a genome-wide census of AE in human and mouse transcripts available from the UCSC and RefSeq databases (for details, see Materials and Methods). The boundaries of UTRs and CDS for each gene locus were determined from start and stop codon annotations for all isoforms mapped to the respective locus. We used conservative criteria for the UTR and CDS definitions to ensure that protein-coding regions are completely excluded from the analysis of UTR sequences and vice versa. To distinguish between different types of AEs, we partitioned protein-coding genes into five functional domains: 5′ UTR, 5′-grey area, CDS; 3′-grey area, and 3′ UTR (fig. 1).

UCSC and RefSeq databases are populated with different sets of alternative transcripts. In our study, analysis of both databases yielded similar trends and correlations. Here, we present the data for the UCSC database, which contains more alternative isoforms and presents a better annotation of AEs, as compared with the RefSeq database. Approximately, 77% of the transcripts in the UCSC database were assigned to alternatively spliced or AT loci (table 1), in agreement with the recent findings indicating that AEs occur in most of the human genes (Xing and Lee 2006). Fractions of the genes with AEs in the 5′ UTR and in the CDS were similar, whereas the fraction of genes with AEs in the 3′ UTR was significantly lower than that in 5′ UTR or the CDS (table 1). There was no positive correlation between these values and the lengths of the respective functional domains: indeed, on average, 5′ UTRs are much shorter than 3′ UTRs, whereas the lengths of the 3′ UTRs are comparable with the CDS lengths (supplementary fig. S1, Supplementary Material online).

Table 1.

Distribution of Human Genes/Transcripts with Alternative Events in Different Functional Domains

| Number of Genes/Transcripts with AEs in |

||||

| Gene/Transcript Group | Number (and Fraction) of Genes/Transcripts | 5′ UTRs | CDSs | 3′ UTRs |

| RefSeq database | ||||

| Non-ALT genes | 13,945 (0.77) | |||

| ALT genes | 4,131 (0.23) | 2,096 (0.51) | 2,781 (0.67) | 1,097 (0.26) |

| Non-ALT transcripts | 13,945 (0.56) | |||

| ALT transcripts | 10,959 (0.44) | 5,903 (0.54) | 7,562 (0.69) | 3,068 (0.28) |

| UCSC database | ||||

| Non-ALT genes | 10,210 (0.47) | |||

| ALT genes | 11,567 (0.53) | 7,722 (0.67) | 7,953 (0.69) | 4,839 (0.42) |

| Non-ALT transcripts | 10,210 (0.22) | |||

| ALT transcripts | 35,265 (0.78) | 25,497 (0.72) | 25,348 (0.72) | 15,953 (0.45) |

NOTE.—The table shows numbers and fractions (in parentheses) of genes and transcripts with and without alternative nucleotides (ALT and non-ALT) in the RefSeq and UCSC databases and distribution of alternative nucleotides in different functional domains of mammalian transcripts.

We evaluated the fractions of constitutive and alternative nucleotides for different functional domains of transcripts taking into account lengths of domains. The fractions of constitutive and alternative nucleotides substantially differed between the functional domains. In particular, constitutive nucleotides were predominant in the CDS, alternative nucleotides were predominant in 5′ UTRs, and in 3′ UTRs, the fractions of constitutive and alternative nucleotides were similar (supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online). The grey areas by definition were enriched in alternative nucleotides (supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online). We hypothesized that the dramatically different fractions of alternative nucleotides in 5′ UTRs and CDS could be at least partially explained by the dominance of different mechanisms of transcript variability and regulation between domains, namely, ATI in 5′ UTRs and AS in CDS.

Relative Contributions of Different Types of AEs to Transcript Diversity

We analyzed the frequencies of ATI, AS, and ATT in different functional domains of human and mouse genes. As expected, AS was most common in the CDS, less common in 5′ UTRs, and strongly avoided in 3′ UTRs, whereas ATI and ATT were the dominant classes of AEs in UTRs (table 2; supplementary tables S2 and S4, Supplementary Material online).

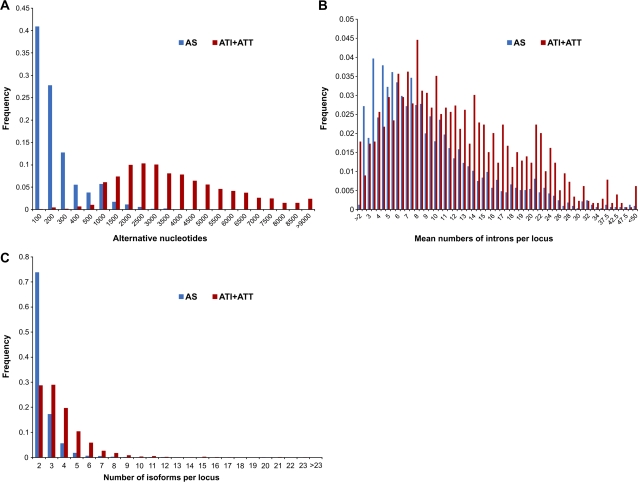

To evaluate the relative contributions of different AEs to the diversity of the mammalian transcriptome, we analyzed the number of isoforms and the number, length, and density of introns in gene loci that undergo different types of AEs (supplementary table S5, Supplementary Material online). All nucleotides that are involved in AEs in the first and last alternative exons in alternative transcripts, within the locus with different upstream and downstream transcription initiation/termination sites, were classified as involved in alternative transcription (see Materials and Methods). We compared the distributions of the number of alternative nucleotides and the mean numbers of isoforms and introns per locus in subsets of genes with different types of AEs. The results show that ATI and ATT greatly increase the diversity and complexity of transcripts in mammals (fig. 2A–D). Genes with alternative transcription events on average produce more complex (larger numbers of introns; P < 10−36) and more numerous (P < 10−32) isoforms compared with genes that undergo only AS (supplementary table S5, Supplementary Material online). Genes with multiple ATI sites have longer 5′-grey areas and produce more complex primary transcripts with larger numbers of isoforms than genes with multiple ATT sites (supplementary table S5; supplementary fig. S2, Supplementary Material online). The difference in the characteristic number of alternative nucleotides per locus in subsets of genes with AS alone and with ATI + ATT is dramatic (fig. 2A; P < 10−200). This difference stems primarily from the variability of 5′ UTRs and 3′ UTRs, whereas the difference in the CDS, although pointing in the same direction and statistically significant (P < 10−3), was far less pronounced. The positive association between the number of alternative nucleotides and the number of introns is demonstrated in supplementary figure S3A (Supplementary Material online). There is only a marginal positive connection between the number of alternative nucleotides and the number of isoforms because a few AS sites may create ultralong introns/exons and so produce a large number of alternative nucleotides (supplementary fig. S3B, Supplementary Material online). Thus, contribution of alternative transcription to the generation of transcript diversity is complex in the sense that ATI and ATT not only create alternative transcripts but also allow additional AS to occur in the longer transcript, an effect that is especially important in the case of ATI. Taking into account that the vast majority of AT and/or spliced gene loci with significant enrichment for alternative nucleotides (5% of the total distribution) employ ATI and/or ATT (fig. 2; table 2), we conclude that on the whole alternative transcription makes a greater contribution to the diversity of transcript isoforms than AS.

FIG. 2—

Distribution of number of alternative nucleotides (A), introns (B), and isoforms (C) per gene locus for sets of human genes with different types of AEs. AS, gene loci with AS alone, where all transcripts from the gene locus begin and end at the same positions; ATI + ATT, gene loci with both ATI and ATT.

Relationships between Alternative Events within Functional Domains of Mammalian Transcripts

As expected, ATI, AS, and ATT were the predominant AEs in 5′ UTRs, CDSs, and 3′ UTRs, respectively. However, we observed complex relationships between these AEs within and between functional domains of mammalian transcripts.

Coupling between ATI and AS in 5′ UTRs.

Presumably, AEs generated by distinct molecular mechanisms evolved independently. However, we detected strong coupling between ATI and AS in 5′ UTRs (fig. 3; supplementary tables S6 and S7, Supplementary Material online). Although the frequency of AS in 5′ UTRs is relatively high, it rarely occurs in the absence of ATI. Frequencies of ATI and AS in 5′ UTRs were 0.609 and 0.361, respectively (table 2), and the observed frequency of co-occurrence of ATI and AS was 0.339, substantially greater than the randomly expected frequency of 0.219 (χ2 = 1659, P (χ2) = 10−200).

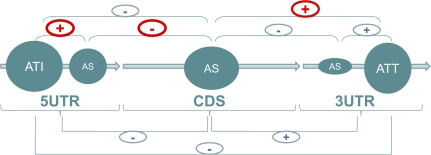

FIG. 3—

.Relationships between AEs within and between the functional domains of mammalian transcripts. The diameters of the circles are roughly proportional to the prevalence of the respective AEs in the given transcript domain; (+) denotes a significant positive correlation and (−) denotes a significant negative correlation; the strongest correlations are shown in red.

In agreement with these findings, there was a significant positive correlation between the numbers of alternative nucleotides involved in ATI and AS in 5′ UTRs (R = 0.19 for UCSC and R = 0.21 for RefSeq; P < 0.0001). The ATI-AS coupling in 5′ UTRs could be explained by the requirement of short 5′ UTRs for efficient initiation of translation (Wegrzyn et al. 2008), so that utilization of an upstream transcription start is compensated by AS.

Coupling between ATT and AS in 3′ UTRs.

We also found a strong positive correlation between ATT and AS in 3′ UTRs (fig. 3, supplementary tables S6 and S7, Supplementary Material online): AS in 3′ UTRs, although rare, was almost invariably accompanied by ATT. The expected co-occurrence frequency of ATI and AS is 0.406 × 0.037 = 0.015, whereas the observed co-occurrence frequency was 0.033, 2-fold greater than expected by chance and highly statistically significant (χ2 = 432, P (χ2) = 2.5 × 10−93).

Connections between Alternative Events in Different Functional Domains of Transcripts

In the preceding section, we described the apparent coupling between different types of AEs within the same domain of transcripts, such as the coupling between ATI and AS in 5′ UTRs. To gain further insight into the relationships between ATI, ATT, and AS, we examined the connections between AEs that co-occur in different functional domains, that is, in 5′ UTRs and CDSs, in CDSs and 3′ UTRs, and in both UTRs.

ATI in 5′ UTR Versus AS in CDS.

There are strong, highly significant and consistent negative correlations between AEs in 5′ UTR and CDS (fig. 3 and supplementary tables S6 and S7, Supplementary Material online). Genes with AS in the CDS are substantially less likely to harbor ATI or AS in the 5′ UTR (P < 10−6, table 2 and supplementary table S7, Supplementary Material online). The strongest negative correlation between AS in 5′ UTRs and CDS was observed for the group of genes that do not employ ATI or ATT (“AS” in table 2 and supplementary table S7, Supplementary Material online), suggestive of mutually exclusive AS in these transcript domains. This mutual avoidance of AS in CDSs and 5′ UTRs was highly significant for the complete set of transcripts from UCSC database (χ2 = 1,205, P (χ2) = 5.7 × 10−201, supplementary table S6, Supplementary Material online). This effect was even more striking for genes with a single transcription initiation site (without ATI). The frequency of co-occurrence of AS in 5′ UTR and CDS in this gene group was 5-fold lower than expected. The correlation between ATI in 5′ UTRs and AS in CDS was also negative and highly significant (χ2 = 553, P (χ2) = 1.2 × 10−119) but substantially weaker than the negative correlation between AS in these domains.

Coupling between ATT in 3′ UTRs and AS in CDS.

We observed a consistent positive correlation between AEs in CDS, the 3′-grey areas and 3′ UTRs (fig. 3 and supplementary tables S6 and S7, Supplementary Material online). AS in the CDS is frequently accompanied with AEs in the 3′ grey area and in the 3′ UTR as well (P < 10−5, supplementary table S7, Supplementary Material online). Moreover, ATT occurs at 3′ regions almost exclusively when there is AS in the CDS (χ2 = 1390, P (χ2) = 5.5 × 10−301; supplementary table S6, Supplementary Material online). This tight connection suggests that the variability of 3′ UTRs is functionally related to the variability of protein-CDSs.

Thus, our results reveal differential connections of AEs in 5′ UTRs and 3′ UTRs with AEs in the protein-coding regions.

AEs in Different GO Categories

A comparison of the GO categories associated with genes undergoing ATI, on the one hand, and genes undergoing AS but not ATI in the CDS, on the other hand, revealed notable, statistically significant differences. Specifically, the ATI group was enriched for genes involved in developmental processes, signal transduction, and apoptosis, whereas the AS group was enriched for genes involved in cellular processes and organization, protein modification, and regulation of metabolism (supplementary table S8, Supplementary Material online). These findings seem to support the conclusion that ATI in 5′ UTRs and AS in the CDS are differentially employed to regulate different functional classes of genes. Furthermore, it appears plausible that transcription from alternative promoters is predominantly used by tissue and/or developmental stage-specific genes, whereas AS increases diversity of protein isoforms that perform more general cellular and metabolic functions.

Discussion

It is often assumed that AS is the primary source of transcript diversity in mammals. The present analysis shows that this view is valid only for the CDS, whereas in the 5′ UTRs and the 3′ UTRs, the dominant AEs are, respectively, ATI and ATT. Our comparative analysis of alternative nucleotides, mean numbers of isoforms, and introns per locus in gene subsets with different types of AEs demonstrates that ATI and ATT contribute to the diversity of mammalian transcriptome even more than AS. We detected two types of coupling between different classes of AEs: within functional domains of transcript and between domains. In the 5′ UTRs, ATI and AS are positively correlated, revealing an unexpected dependence between two classes of a priori independent AEs. As for between domain connections, there is a tight coupling between AS in CDS and ATT in 3′ UTRs but, in contrast, a strong anticorrelation between ATI and especially AS in 5′ UTRs and AS in the CDS (fig. 3). Recent studies on connections between AS and AT in mammals reported a positive correlation between the two types of AEs (Xin et al. 2008; Ma et al. 2009). The present work reveals a much more complex, differentiated relationship thanks to the separate analysis of different functional domains of transcripts.

The structure of the correlations between different types of AEs revealed here suggests two opposite trends: 1) tight coupling between alternative transcription and AS and 2) preferential use of different AEs by two classes of genes with different dominant types of regulation. The genes in the first of these classes appear to be regulated, primarily, at the level of translation initiation, via variability of the 5′ UTR generated by ATI and, to a lesser extent, AS. By contrast, the genes in the second class appear to be regulated primarily at the posttranslational level, via the formation of alternative protein forms resulting from AS in the CDS. Furthermore, our results suggest distinct roles for different types of AEs in the regulation of cellular processes and the possibility of common regulatory mechanisms for large groups of functionally related genes as demonstrated by the analysis of the distribution of different types of AE across the GO categories.

The coupling between ATI and AS in 5′ UTRs seems to receive a simple explanation from the requirement for optimal length (approximately 100 nucleotides, on average) of 5′ UTRs for efficient initiation of translation (Kozak 1978; Mignone et al. 2002): utilization of upstream transcription start sites necessitates AS to remove portions of the resulting long 5′ UTR (Lynch et al. 2005). The interdomain coupling between AS in the CDS and ATT in the 3′ UTR is more unexpected and suggests that the genes whose function is regulated through the formation of alternative protein forms are also regulated by the 3 ′UTRs, possibly, at the level of mRNA stability (Gallie 1991; Shyu et al. 2008). In addition, in eukaryotes, 3′ UTRs appear to contribute to the regulation of translation initiation via circularization of translated mRNAs (Hsu and Coca-Prados 1979; Komarova et al. 2006).

Low incidence of splicing in 3′ UTRs could be due to the high abundance of transcription termination signals in 3′ noncoding gene regions and also to the absence of strong constraint on the lengths of 3′ UTRs (Shabalina and Spiridonov 2004; Hong et al. 2006). For these reasons, termination of alternative transcripts with variable last coding exons may not require additional splicing, as it can be easily achieved at the next downstream transcription termination site. Splicing in 3′ UTRs might be also functionally unwarranted and avoided due to metabolic expenses associated with transcription of additional introns. Intron avoidance in 3′ UTRs together with the interdomain coupling between AS in the CDS and ATT in the 3′ UTR suggests coordinated regulation of these processes. Our results are in good agreement with the recently described connection between AS and alternative cleavage and polyadenylation across different tissues (Wang et al. 2008).

The present observations are compatible with the emerging understanding of the importance of cotranscriptional processing of mRNAs and functional connections between transcription initiation and splicing (Kornblihtt et al. 2004; Kornblihtt 2007). Numerous experimental results indicate that RNA polymerase II and transcription elongation factors recruit splicing factors to chromatin-associated “factories” in which transcription occurs concomitantly with various mRNA processing steps, including capping, splicing, cleavage/polyadenylation, and eventually, nucleocytosolic export (McCracken et al. 1997; Bentley 2002, 2005; Maniatis and Reed 2002; Hagiwara and Nojima 2007). The recruitment of splicing factors to the factories is specifically mediated by the phosphorylated, repetitive carboxy-terminal domain (CTD) of the RNA polymerase II largest subunit (Misteli and Spector 1999; Zeng and Berget 2000). Moreover, it has been shown that ultraviolet damage causes hyperphosphorylation of CTD with subsequent inhibition of transcription elongation and gene-specific modulation of the AS pattern that ultimately prevents apoptosis in irradiated cells (Munoz et al. 2009). The CTD has been shown to interact with splicing factors of the SR family and to directly regulate AS via exon skipping (de la Mata and Kornblihtt 2006). These results indicate that AS is not only coupled to transcription but is specifically regulated by the transcription machinery within the expression factories. Regulation of AS of specific genes in the factory critically depends on the structure of RNAP II promoter, providing direct evidence of coupling between transcription initiation and AS (Cramer et al. 1999).

In summary, the results of a genome-wide survey of AEs in mammalian transcripts suggest that alternative transcription is an even bigger source of mammalian transcriptome diversity than AS and that complex relationships between the two types of AEs, both synergistic and antagonistic, govern regulation of gene expression in mammals.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures S1–S3 and tables S1–S8 are available at Genome Biology and Evolution online (http://www.gbe.oxfordjournals.org/).

Acknowledgments

The research of S.A.S. and E.V.K. is supported by the intramural funds of the US Department of Health and Human Services (National Library of Medicine).

References

- Baek D, Davis C, Ewing B, Gordon D, Green P. Characterization and predictive discovery of evolutionarily conserved mammalian alternative promoters. Genome Res. 2007;17:145–155. doi: 10.1101/gr.5872707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley D. The mRNA assembly line: transcription and processing machines in the same factory. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:336–342. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00333-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley DL. Rules of engagement: co-transcriptional recruitment of pre-mRNA processing factors. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:251–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blencowe BJ. Alternative splicing: new insights from global analyses. Cell. 2006;126:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenik C, Derti A, Mellor JC, Berriz GF, Roth FP. Genome-wide functional analysis of human 5′ untranslated region introns. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R29. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-3-r29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer P, et al. Coupling of transcription with alternative splicing: RNA pol II promoters modulate SF2/ASF and 9G8 effects on an exonic splicing enhancer. Mol Cell. 1999;4:251–258. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80372-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Mata M, Kornblihtt AR. RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain mediates regulation of alternative splicing by SRp20. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:973–980. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallie DR. The cap and poly(A) tail function synergistically to regulate mRNA translational efficiency. Genes Dev. 1991;5:2108–2116. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.11.2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillo G, et al. UTRdb and UTRsite (RELEASE 2010): a collection of sequences and regulatory motifs of the untranslated regions of eukaryotic mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D75–D80. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara M, Nojima T. Cross-talks between transcription and post-transcriptional events within a “mRNA factory”. J Biochem. 2007;142:11–15. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvm123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris MA, et al. The Gene Ontology (GO) database and informatics resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D258–D261. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong X, Scofield DG, Lynch M. Intron size, abundance, and distribution within untranslated regions of genes. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:2392–2404. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu MT, Coca-Prados M. Electron microscopic evidence for the circular form of RNA in the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells. Nature. 1979;280:339–340. doi: 10.1038/280339a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Goren A, Ast G. Alternative splicing: current perspectives. Bioessays. 2008;30:38–47. doi: 10.1002/bies.20692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarova AV, Brocard M, Kean KM. The case for mRNA 5' and 3' end cross talk during translation in a eukaryotic cell. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2006;81:331–367. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(06)81009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondrashov AS, Shabalina SA. Classification of common conserved sequences in mammalian intergenic regions. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:669–674. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.6.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornblihtt AR. Coupling transcription and alternative splicing. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;623:175–189. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-77374-2_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornblihtt AR, de la Mata M, Fededa JP, Munoz MJ, Nogues G. Multiple links between transcription and splicing. RNA. 2004;10:1489–1498. doi: 10.1261/rna.7100104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak M. How do eukaryotic ribosomes select initiation regions in messenger RNA? Cell. 1978;15:1109–1123. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry JR, Mager DL, Wilhelm BT. Complex controls: the role of alternative promoters in mammalian genomes. Trends Genet. 2003;19:640–648. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2003.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, Scofield DG, Hong X. The evolution of transcription-initiation sites. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:1137–1146. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, et al. Systematic analysis of alternative promoters correlated with alternative splicing in human genes. Genomics. 2009;93:420–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis T, Reed R. An extensive network of coupling among gene expression machines. Nature. 2002;416:499–506. doi: 10.1038/416499a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken S, et al. The C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II couples mRNA processing to transcription. Nature. 1997;385:357–361. doi: 10.1038/385357a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mignone F, Gissi C, Liuni S, Pesole G. Untranslated regions of mRNAs. Genome Biol. 2002;3:REVIEWS0004. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-3-reviews0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misteli T, Spector DL. RNA polymerase II targets pre-mRNA splicing factors to transcription sites in vivo. Mol Cell. 1999;3:697–705. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)80002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz MJ, et al. DNA damage regulates alternative splicing through inhibition of RNA polymerase II elongation. Cell. 2009;137:708–720. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogurtsov AY, et al. Expression patterns of protein kinases correlate with gene architecture and evolutionary rates. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3599. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Q, Shai O, Lee LJ, Frey BJ, Blencowe BJ. Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1413–1415. doi: 10.1038/ng.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resch A, et al. Assessing the impact of alternative splicing on domain interactions in the human proteome. J Proteome Res. 2004;3:76–83. doi: 10.1021/pr034064v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resch AM, Ogurtsov AY, Rogozin IB, Shabalina SA, Koonin EV. Evolution of alternative and constitutive regions of mammalian 5' UTRs. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:162. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabalina SA, et al. Distinct patterns of expression and evolution of intronless and intron-containing mammalian genes. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27:1745–1749. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabalina SA, Spiridonov NA. The mammalian transcriptome and the function of non-coding DNA sequences. Genome Biol. 2004;5:105. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-4-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyu AB, Wilkinson MF, van Hoof A. Messenger RNA regulation: to translate or to degrade. Embo J. 2008;27:471–481. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultan M, et al. A global view of gene activity and alternative splicing by deep sequencing of the human transcriptome. Science. 2008;321:956–960. doi: 10.1126/science.1160342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakaguri H, Yamashita R, Suzuki Y, Sugano S, Nakai K. DBTSS: database of transcription start sites, progress report 2008. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D97–D101. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ET, et al. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature. 2008;456:470–476. doi: 10.1038/nature07509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegrzyn JL, Drudge TM, Valafar F, Hook V. Bioinformatic analyses of mammalian 5'-UTR sequence properties of mRNAs predicts alternative translation initiation sites. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:232. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm BT, et al. Dynamic repertoire of a eukaryotic transcriptome surveyed at single-nucleotide resolution. Nature. 2008;453:1239–1243. doi: 10.1038/nature07002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin D, Hu L, Kong X. Alternative promoters influence alternative splicing at the genomic level. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing Y, Lee C. Alternative splicing and RNA selection pressure–evolutionary consequences for eukaryotic genomes. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:499–509. doi: 10.1038/nrg1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita R, Wakaguri H, Sugano S, Suzuki Y, Nakai K. DBTSS provides a tissue specific dynamic view of transcription start sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D98–D104. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeeberg BR, et al. GoMiner: a resource for biological interpretation of genomic and proteomic data. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R28. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-4-r28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng C, Berget SM. Participation of the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II in exon definition during pre-mRNA splicing. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:8290–8301. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.21.8290-8301.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]