Abstract

In malignancies where no universally expressed dominant Ag exists, the use of tumor cell-based vaccines has been proposed. We have modified a mouse neuroblastoma cell line to express either CD80 (B7.1), CD137L (4-1BBL), or both receptors on the tumor cell surface. Vaccines expressing both induce a strong T cell response that is unique in that among responding CD8 T cells, a T effector memory cell (TEM) response arises in which a large number of the TEM express the α-chain of VLA-2, CD49b. We demonstrate using both in vitro and in vivo assays that the CD49b+CD8 T cell population is a far more potent antitumor effector cell population than nonfractionated CD8 or CD49b−CD8 T cells and that CD49b on vaccine-induced CD8 T cells mediates invasion of a collagen matrix. In in vivo rechallenge studies, CD49b+ T cells no longer expanded, indicating that CD49b TEM expansion is restricted to the initial response to vaccine. To demonstrate a mechanistic link between the expression of costimulatory molecules on the vaccine and CD49b on responding T cells, we stimulated naive T cells in vitro with artificial APC expressing different combinations of anti-CD3, anti-CD28, and CD137L. Although some mRNA encoding CD49b was induced by combining anti-CD3 with anti-CD28 or CD137L, the highest level was induced when all three signals were present. This indicates that CD49b expression results from additive costimulation and that the level of CD49b message serves as an indicator of the effectiveness of T cell activation by a cell-based vaccine.

Neuroblastoma is the most common extracranial solid cancer in childhood and accounts for 15% of childhood cancer deaths (1). Survival for children with advanced disease is <40% despite aggressive therapy (2). Clinical research has provided clues that the immune system can be marshaled against this disease. For example, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation has been demonstrated to be superior to other treatment regimens that do not overtly manipulate the immune system and may induce a graft-versus- tumor effect (3, 4). Based on clinical approaches that manipulate the immune system, as well as experimental animal models, a number of immune-based strategies have been tested in clinical trials for neuroblastoma. These have included using allogeneic or autologous patient-derived cancer cells as a vaccine, or a modification of these cell-based vaccines by the introduction of IL-2 and/or lymphotactin gene expression vectors (5, 6). However, no clear clinical benefit was seen resulting in the need to reevaluate how best to modify these cells for an increased immunostimulatory effect (7). The evaluation of the effectiveness of these vaccines, as well as of other cancer vaccines, is complicated by the lack of well-defined readouts of efficacy, beyond that of relapse of disease.

Neuroblastoma is weakly immunogenic and for a time it was thought to not be a suitable clinical target for immune attack due to a lack of class I MHC expression in pathological studies. However, careful analysis revealed that class I MHC is expressed on neuroblastoma upon incubation with IFN-γ (8). Moreover, neuroblastoma can readily be lysed by T cells in in vitro assays (9). Using the AGN2a cell line, generated by in vivo passage of a strain A-derived spontaneously arising neuroblastoma (Neuro-2a), we have generated a series of cell-based vaccines. Using either constitutively expressing or transiently transfected AGN2a, we have demonstrated that the expression of CD80 and CD86 or CD80, CD86, CD54, and CD137L transforms the tumor cell line into a potent protective vaccine in challenge studies (10). Our work has also demonstrated that for cell-based vaccines to be effective in a tumor-bearing model, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in combination with vaccination and adoptive T cell therapy is required (W. Jing, R. J. Orentas, B. D. Johnson, manuscript in preparation). It was the addition of CD137 signaling to CD28 (via CD80) and TCR (via tumor MHC) signals that led to the ability to detect antitumor lytic T cell activity directly in the spleens of immunized mice. This strong lytic activity was not seen in splenocytes derived from mice vaccinated with modified neuroblastoma expressing only CD80 and CD86 unless they received in vitro stimulation as well (11). In this report, we sought to further explore the mechanism accounting for this effect.

CD137L (4-1BBL, TNFSF9), the counterreceptor for CD137 (4-1BB), is a member of the TNF (ligand) superfamily and serves as a secondary signal to activated T cells. CD137 is an inducible member of the TNFR superfamily that can induce cytokine production, expansion, and functional maturation of T cells, NK cells, monocytes, and dendritic cells (12–14). After prolonged TCR/CD28 activation in vitro, T cells increase CD137 expression and upon binding become strongly adherent to fibronectin (15). With regard to tumor biology, binding of CD137 has been demonstrated to prevent and even rescue anergic CD8 T cells in a number of tolerance-inducing models (16). CD137 agonist Ab has also been shown to overcome immunological ignorance (where CTL were not deleted or anergized, but simply not activated), allowing immunization with tumor-derived peptide to induce a protective CTL response (17).

VLA-2 (as detected by the DX5 Ab) was originally considered to be a NK cell marker. However, in addition to our studies, others analyzing antiviral CD8 responses have also described the expression of what were once considered “NK cell markers” on activated T cells (18–20). VLA-2 can also be found on megakaryocytes, activated NK cells, neutrophils, and long-term activated T cells (21–23). VLA-2 is composed of an α2 (CD49b) and a β1 (CD29) heterodimer and is known to mediate cell adhesion to extracellular matrix components such as collagen type I and IV and homotypic adhesion (24). In the current study, we link the reported increased adhesion of CD137-activated CD8 T cells to extracellular matrix components with the expression of VLA-2. We show that VLA-2 serves as a marker for activation by CD137L-expressing cell-based vaccines, and we demonstrate that the CD49b+ population is far more active than CD49b−CD8 T cells. We propose that the expression of CD49b (VLA-2) may serve as a surrogate marker for successful tumor vaccination.

Materials and Methods

Animals, cell lines, Abs, and microbeads

A/J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and used at 5–8 wk of age. All experiments were performed under approved protocols in a pathogen-free environment at the Medical College of Wisconsin, which contains an American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-certified facility. Anti-CD8-conjugated immunomagnetic beads used for automated cell separation (AutoMACS) were purchased from Miltenyi Biotec. A Dynal mouse CD8-negative isolation kit was purchased from Invitrogen Dynal. Anti-CD80 (16-10A1), anti-CD4 (OX-35), anti-CD49b (HMα2, DX5), anti-CD3 (2C11), anti-CD28 (37.51), anti-CD44 (IM7), anti-CD62L (MEL-14), and anti-CD137L (TKS-1) were purchased from BD Biosciences Pharmingen. Anti-CD8 (53–6.7) was purchased from eBioscience. Generation of the AGN2a (aggressive) sublcone of Neuro-2a (obtained from American Type Culture Collection) was described previously (9).

Lymphocyte activation and analysis by quantitative real-time PCR

CD8+ T cells were purified from A/J splenocytes by immunomagnetic sorting using AutoMACS (purity > 95%). Production of the mouse CD32- and/or CD137L-expressing K562 artificial APC lines (aAPC)3 was described previously (11). CD3 or CD3 and CD28 signals were provided by coating the CD32 or CD32- and CD137L-expressing K562 aAPC with anti-CD3 or anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 Abs as previously described (11). Ab- coated aAPC were irradiated with 4000 rad from a cesium source and cocultured with purified CD8 T cells at a ratio of 1:2 (2.5 × 105 aAPC plus 5 × 105 T cells in 24-well plates containing complete DMEM and 20 U/ml human rIL-2 (Proleukin; Chiron)). 5 × 106 viable cells (as assessed by trypan blue exclusion) were harvested after 72 h of culture, total RNA was isolated with TRIzol (Invitrogen), and cDNA was generated using SSII reverse transcriptase and oligo(dT) (12–18) primer (Invitrogen). CD49b copy number was determined by real-time PCR in the presence of Brilliant SYBR Green (diluted 1/2000; Stratagene). Briefly, Taq polymerase, standard buffers (50 mM MgCl2, 8% glycerol, 3% DMSO, and 25 mM dNTPs) and primers CD49b forward, 5′-CCGGGTGCTACAAAAGTCAT; reverse, 5′-GTCGGCCACATTGAAAAAGT and hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT) forward, 5′-TGAAGAGCTACTGTAATGATCAGTCAA; reverse, 5′-AGCAAGCTTGCAACCTTAACCA were mixed, and the cDNA was amplified at 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, and then cycled 40 times between 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min using a DNA Engine Opticon2 (Bio-Rad). A single peak was seen on melting curves conducted at the end of each run to ensure single product amplification. The amount of CD49b increase was normalized to HPRT as an internal standard and calculated as fold increase seen over stimulation of T cells with anti-CD3 alone using the comparative cycle threshold method (Applied Biosystems User Bulletin 2; Applied Biosystems).

Vaccination protocol

AGN2a cells expressing CD80 (AGN2a/CD80), CD137L (AGN2a/CD137L), or both (AGN2a-CD80/137L) were derived and established as permanently transfected cell lines, and expression of costimulatory molecules was verified before each experimental procedure. For vaccination, 2 × 106 vaccine cells, either viable or irradiated with 4000 rad, were injected s.c. twice weekly (days 0 and 7). For recall response analysis, previously vaccinated mice were revaccinated at day 60. On days 12, 19, 26, 33, 60, 67, 74, and 81 after the first vaccination, peripheral blood, spleen, bone marrow, and draining lymph node (dLN) single-cell suspensions were prepared and stained with the indicated markers, and total splenic cell number was determined as well. CD8+ T cells from the spleen were purified by AutoMACS sorting and cryopreserved for ELISPOT analysis.

Adoptive immunotherapy with purified CD49b+ cells

A/J mice were vaccinated with irradiated AGN2a-CD80/137L cells twice weekly. Five days after the second vaccination, splenocytes were harvested and CD8+ T cells were purified by negative selection (i.e., untouched). Purified CD8+ cells were then fractionated by AutoMACS after incubating the cells with PE-conjugated anti-CD49b Ab and anti-PE-conjugated microbeads. In brief, 2.5 × 106 CD49b+, CD49b−, or total CD8+ T cells were then infused by tail vein injection into tumor-bearing A/J mice (injected with 1 × 105 AGN2a s.c. 24 h before T cell infusion). Tumor growth and survival were monitored. Surviving mice were challenged with 1 × 105 wild-type parental tumor, AGN2a, 60 days later. Animals were sacrificed, according to institutional protocol, when tumors reached 250 mm2.

Cytokine analysis

Splenocytes from AGN2a−CD80/137L- vaccinated mice were purified by AutoMACS after incubation with anti-CD8 microbeads. CD49b+ and CD49b− populations were separated by flow cytometric sorting (FACS-Diva; BD Biosciences) and purified populations were incubated in triplicate wells with or without 1 × 104 irradiated AGN2a (unmodified, wild-type tumor) in 96-well plates. After 3 days of incubation, 50 μl of supernatant was collected and cytokines were measured using the BD Biosciences Th1/Th2 cytokine bead array kit.

Chromium release assays

Purified lymphocyte subsets were tested for the ability to lyse tumor cells in standard chromium release assays as described previously (11). Briefly, tumor cell targets (AGN2a, AGN2a-CD80/137L, or YAC-1) were incubated in 100 μCi of 51Cr (as sodium chromate; Amersham Biosciences) per million cells for 90 min at 37°C, washed extensively, and then coincubated with effector cell populations at the indicated E:T ratios in a final volume of 200 μl. At the indicated time points, 50 μl of supernatant was collected from individual wells and added to Lumaplate-96 microplates (Packard Instrument). The plates were dried and radioactivity was measured on a Packard TopCount. Percent lysis is reported as the ratio of experimental: total release, following subtraction of spontaneous release from each.

ELISPOT analysis

Enumeration of IFN-γ producing cells was conducted as described previously (11). Briefly, capture anti-mouse IFN-γ mAb (BD Biosciences) was used to coat 96-well polyvinylidene difluoride membrane plates (Millipore) overnight. On the following day, CD8 splenocytes were added in incremental 2-fold dilutions, starting at 5 × 104 or 1 × 105 cells/well, and coincubated with 104 tumor cell stimulators (AGN2a, AGN2a-CD80/137L, or YAC-1) for 30–35 h at 37°C. Plates were then washed, incubated with matched biotinylated detection Ab (BD Biosciences) for 2 h at room temperature, washed again, and then incubated with extravidin-alkaline phosphatase conjugate (Sigma-Aldrich). Spots were developed by adding 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate/NBT substrate (Sigma-Aldrich). The number of spots per well, corresponding to IFN-γ-secreting cells, was determined by automated counting (ImmunoSpot; CTL).

In vitro migration analysis

A/J mice were immunized with AGN2a-CD80/137L cells twice weekly. Five days after the second immunization, CD8+ splenocytes were purified by AutoMACS sorting, immunostained for CD49b, CD62L, and CD44, and then flow sorted into CD49b+CD62L−CD44+, CD49b−CD62L−CD44+, CD49b−CD62L+CD44+, and CD49b−CD62L+CD44− populations. Cells (1 × 105) in 100 μl of culture medium supplemented with 250 U/ml human rIL-2 then were layered on top of 100 μl of solidified collagen matrix (Matrigel, growth-factor reduced; BD Biosciences) in flat-bottom 96-well plates. After 48 h of culture, medium was removed from the Matrigel surface, the surface was rinsed, and then 100 μl of collagenase (collagenase D, 1 mg/ml in pH 7.0 10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, and 1.8 mM CaCl2; Roche) was added to each well, and the plate was incubated at 37°C for 6–8 h. The number of viable cells (by trypan blue exclusion) migrating into the collagen matrix was then counted.

Results

Expansion and activation of CD49b+CD8+ but not CD49b+CD4+ T cells upon AGN2a-CD80/137L vaccination

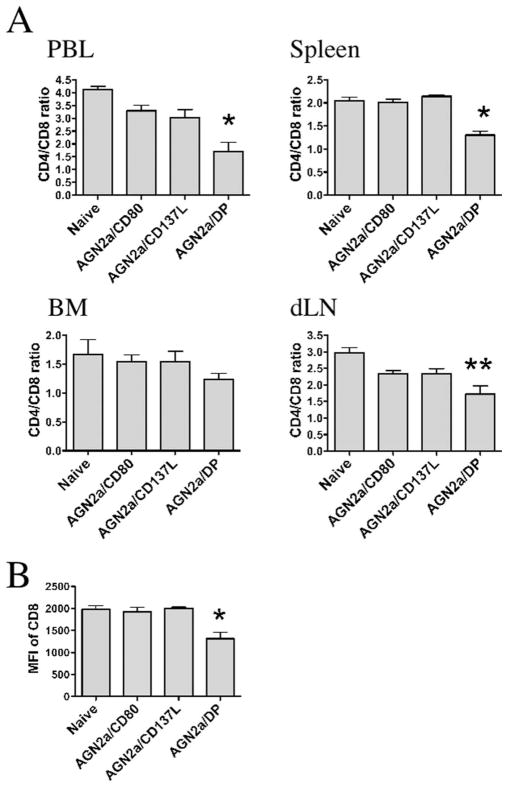

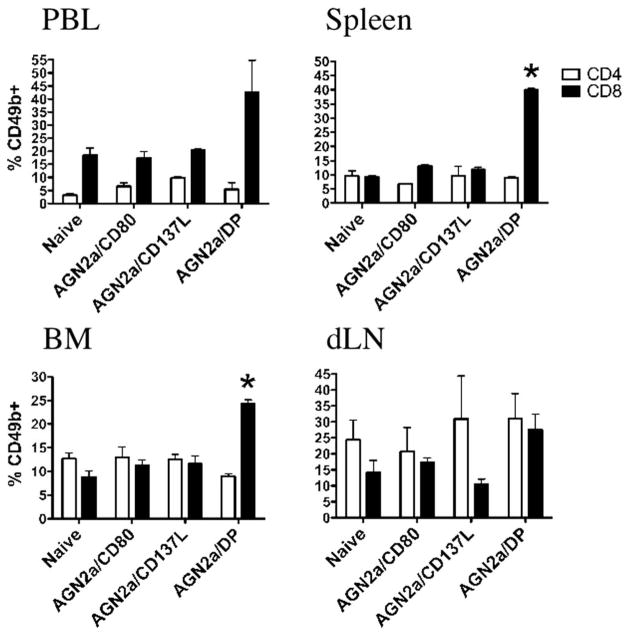

To determine the mechanism by which CD137L-expressing cell-based vaccines activate cellular immunity, we explored changes in the composition of immune cell populations in lymphoid tissues. Mice were immunized twice weekly with AGN2a/CD80, AGN2a/CD137L, or AGN2a-CD80/137L, and 5 days after the second s.c. vaccination, lymphocytes from spleen, bone marrow (BM), peripheral blood (PBL), and vaccine dLN were analyzed. When the ratio of CD4:CD8 cells was analyzed, all tissues showed an increase in the number of CD8 cells, with the most dramatic changes associated with CD137L expression on the vaccine in lymphocytes collected from the peripheral blood and spleen (Fig. 1A). The level of CD8 expression, down-regulation being associated with increased cell activation, was decreased to the greatest extent in mice immunized with AGN2a-CD80/137L (double positive, DP) in peripheral blood (Fig. 1B). In previous work, we demonstrated that cell-based vaccines induce a CD49b-expressing CD8+ T cell population. In Fig. 2, percentages of CD8 cells expressing CD49b in PBL, spleen, BM, and dLN are shown. In all lymphoid compartments, but most notably in PBL and spleen, the highest percentages of CD49b+CD8+ cells were associated with the presence of both CD80 and CD137L on the vaccine. Mice vaccinated with CD80/137L-expressing tumor cells (AGN2a/DP) also contained significantly higher numbers of splenic CD49b+CD8+ and total CD8+ T cells than nonvaccinated naive mice or mice vaccinated with tumor cells expressing CD80 or CD137L alone (Table I). These results indicate that expression of both molecules is required to see CD49b induction and that these signaling pathways activate CD8 T cells in a synergistic manner. Increased expression of CD49b was not seen on CD4 cells (Fig. 2 and Table I).

FIGURE 1.

Impact of vaccination on CD4 and CD8 cells. Mice were vaccinated s.c. with 2 × 106 AGN2a/CD80, AGN2a/CD137L, or AGN2a-CD80/137L (AGN2a/DP) cells twice weekly and sacrificed 5 days after the second vaccination. A group of nonvaccinated (naive) controls were included in the experiments. A, Lymphocytes from peripheral blood (PBL), spleen, BM, and tumor vaccine dLN were analyzed for CD4 and CD8 expression. Ratio of CD4:CD8 cells in naive control, AGN2a/CD80-, AGN2a-CD137L-, and AGN2a-CD80/137L (DP)-vaccinated mice in each tissue is shown. B, Geometric mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD8 on lymphocytes from the peripheral blood of each treatment group listed (*, p < 0.05 when compared with naive control, AGN2a/CD80, or AGN2a/CD137L vaccinated groups;**, p < 0.05 when compared with naive controls; p values were determined by the Student t test). Data are the means ± SDs from one of three independent experiments (n = 3 mice/group).

FIGURE 2.

CD49b expression on CD4 and CD8 cells after vaccination. Mice were vaccinated s.c. with 2 × 106 AGN2a/CD80, AGN2a/CD137L, or AGN2a-CD80/137L (AGN2a/DP) cells twice weekly and sacrificed 5 days after the second vaccination. A group of nonvaccinated (naive) controls were included in the experiments. Percentages of CD49b+ cells in gated CD4 and CD8 cell subsets from naive control, AGN2a/CD80-, AGN2a-CD137L-, or AGN2a-CD80/137L (DP)-immunized mice were determined by flow cytometry. Tissues analyzed were peripheral blood (PBL), spleen, BM, and vaccine dLN (*, p < 0.05 when compared with naive control, AGN2a/CD80-, or AGN2a/CD137L-vaccinated groups;**, p values were determined by the Student t test). Data are the means ± SDs from one of three independent experiments (n = 3 mice/group).

Table I.

Absolute numbers of total splenocytes and splenic T cell subsets

| Treatmenta Absolute Numbersb (×106 ± SD) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | CD4+ | CD49b+CD4+ | CD49b−CD4+ | CD8+ | CD49b+CD8+ | CD49b−CD8+ | |

| Naïve | 40.0 ± 1.72 | 7.57 ± 0.72 | 0.71 ± 0.18 | 6.86 ± 0.89 | 3.71 ± 0.28 | 0.35 ± 0.01 | 3.36 ± 0.28 |

| AGN2a/CD80 | 42.6 ± 2.55 | 7.78 ± 0.69 | 0.53 ± 0.02 | 7.25 ± 0.67 | 3.86 ± 0.29 | 0.50 ± 0.08 | 3.35 ± 0.21 |

| AGN2a/CD137L | 42.9 ± 3.44 | 8.31 ± 1.23 | 0.75 ± 0.34 | 7.56 ± 1.58 | 3.87 ± 0.51 | 0.46 ± 0.06 | 3.42 ± 0.49 |

| AGN2a/DP | 44.7 ± 1.97 | 7.67 ± 0.11 | 0.69 ± 0.08 | 6.98 ± 0.08 | 5.92 ± 0.53* | 2.37 ± 0.23** | 3.55 ± 0.32 |

Groups of mice were vaccinated s.c. with the indicated tumor cells as indicated in Fig. 1 and spleens were harvested 5 days after the second vaccination. A group of nonvaccinated controls (naive) was also included. Splenocytes were stained with the indicated markers and absolute numbers of different cell subsets were calculated.

The data were determined from one of two replicate experiments (n = 3 mice/group).

p <0.05 vs the other three groups.

p < 0.005 vs the other three groups.

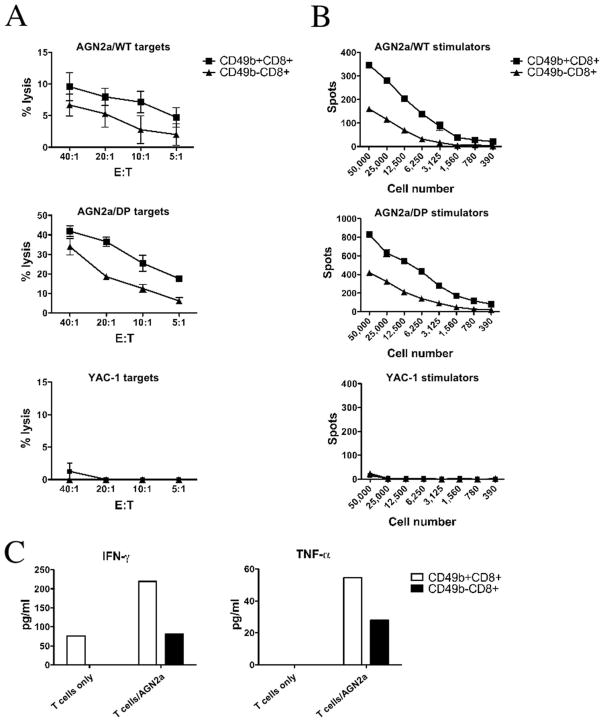

In vitro antitumor activity

To determine whether there were differences in the in vitro anti-tumor activity of CD8+CD49b+ and CD8+CD49b− populations, A/J mice were immunized with AGN2a-CD80/137L as described above and CD49b+ and CD49b−CD8+ T cells were isolated by flow cytometric sorting of splenocytes harvested 5 days after the second weekly s.c. vaccination. Using either unmodified AGN2a, the vaccine line (AGN2a-CD80/137L), or the NK-sensitive YAC-1 cell line as targets in chromium release assays, CD49b+ cells consistently showed higher levels of lytic activity (Fig. 3A). In IFN-γ ELISPOT assays, the CD49b+ population again showed greater levels of antitumor reactivity as judged by the number of cells producing IFN-γ in response to coculture with tumor (Fig. 3B). The CD49b+ cells did not lyse YAC-1 target cells or secrete IFN-γ in response to YAC-1 stimulators (Fig. 3, A and B), indicating that the CD49b+CD8+ were tumor specific and did not exhibit NK cell activity. Cocultures of CD49b+ cells and tumor also showed higher levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α production (Fig. 3C). Notably, the CD49b+ T cell population showed spontaneous IFN-γ production when cultured without stimulation. This may indicate that these cells were already engaged in an active immune response upon isolation. No increase in IL-2, IL-5, or IL-10 production was seen in either population (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Antitumor effector function of CD49b+ cells. Mice were vaccinated with AGN2a-CD80/137L as in Fig. 1, and CD49b+ and CD49b−CD8 T cells were purified by flow cytometric sorting and used as effectors in chromium release assays (A), IFN-γ ELISPOT assays (B), and soluble cytokine production assays (C) with either unmodified wild-type AGN2a (AGN2a/WT), vaccine (AGN2a-CD80/137L or AGN2a/DP), or NK-sensitive YAC-1 tumor cells as the cellular targets. A, Percent lysis at the indicated E:T ratios is shown (the data are representative of three separate experiments, average percent lysis ± SD for a representative experiment is shown). B, The numbers of spots per well at the indicated T cell numbers added per well are shown (data representative of four separate experiments, average spot number ± SD from a representative experiment is shown). C, The release of IFN-γ and TNF-α after 72 h of coculture with tumor cell targets is shown, and the results are from one of two independent experiments, values calculated using provided BD Biosciences software for fluorescent microbead analysis.

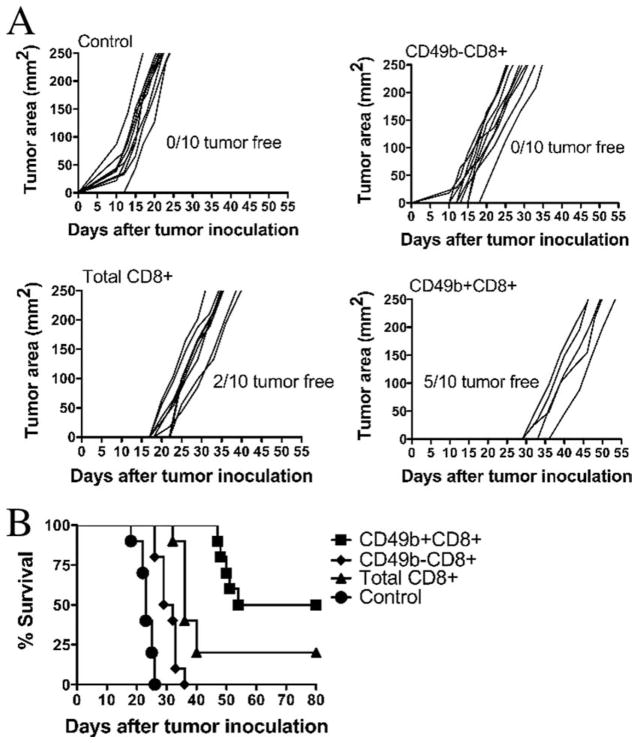

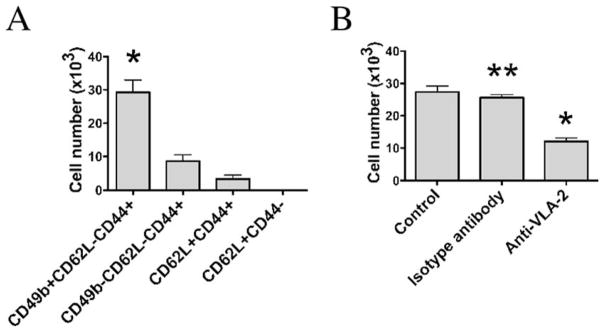

In vivo antitumor activity

To determine whether CD49b+ cells showed greater antitumor activity in vivo, we established an in vivo assay system for the control of tumor progression. Mice bearing s.c. tumors for as little as 24 h are no longer protected by cell-based vaccines (B. Johnson, R. Orentas, unpublished data). If this is due to a failure to activate and expand T cells, adoptive immunotherapy may be an effective means of facilitating an antitumor response. To test this, mice inoculated with viable AGN2a cells were infused 24 h later with 2.5 × 106 CD8+CD49b+, CD8+CD49b−, or unfractionated CD8 cells isolated from AGN2a-CD80/137L-vaccinated mice or left untreated (Fig. 4). Five of 10 mice treated by adoptive immunotherapy with CD49b+ T cells survived while 0 of 10 untreated or CD8+CD49b− treated mice survived (Fig. 4B). Two of 10 mice treated with unfractionated CD8 cells also survived. Notably, the five tumors that occurred in CD49b+ treated mice occurred much later than those in untreated of CD49− treated mice (Fig. 4A). When the five surviving mice were rechallenged with 1 × 105 AGN2a, all survived beyond 60 days (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

In vivo antitumor activity of CD49b+CD8 cells. Splenocytes from AGN2a-CD80/137L-vaccinated mice were harvested and CD49b+and CD49− cells purified from isolated CD8 cells. In brief, 2.5 × 106 T cells (total CD8+, CD49b−CD8+, or CD49b+CD8+) were injected i.v. into A/J mice that had been injected s.c. with 1 × 105 wild-type AGN2a cells 24 h earlier. A control group of mice not injected with T cells was included (control). The data shown are pooled from two independent experiments (n = 10 total mice/group). A, The growth of individual tumors is shown, and the numbers of tumor-free animals in each group are indicated. B, Survival curves are shown. Key statistical comparisons: CD49b+CD8+vs CD49b−CD8+, p < 0.01; CD49b+CD8+vs total CD8+, p < 0.01; and CD49b−CD8+ vs total CD8+, p = 0.01.

Correlation of CD49b expression with T effector-memory marker expression and lytic function

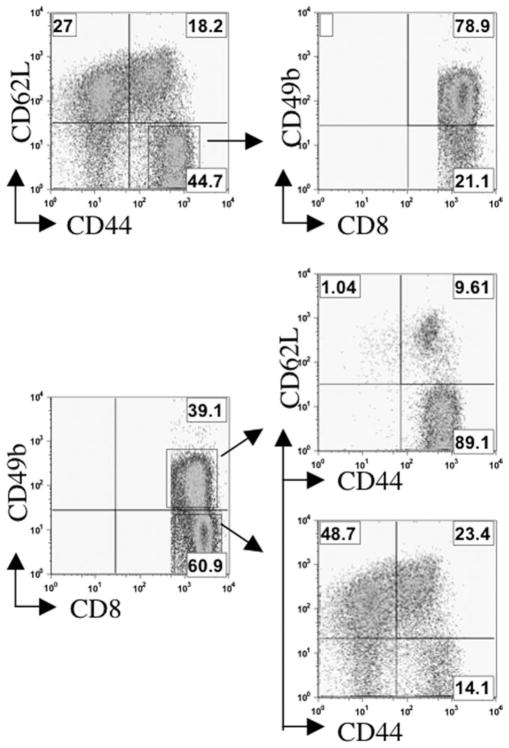

The high lytic and cytokine-producing activity of our vaccine-induced CD49b+CD8+ population led us to test whether these cells bore cell surface markers associated with T effector memory cell (TEM) populations. TEM are Ag-experienced cells (hence they express memory markers) that appear to be actively engaged in immune responses. To test for the correlation between CD49b expression and TEM phenotype, mice were immunized with AGN2a/CD80, AGN2a/CD137L, or AGN2a-CD80/137L twice weekly and, on day 5 after the second vaccination, lymphocytes from spleen, peripheral blood, BM, and vaccine dLN were analyzed by flow cytometry. Representative results from spleen are shown in Fig. 5. To analyze which CD8 cells were primarily CD49b positive, cells from AGN2a-CD80/137L-vaccinated mice were analyzed first. Gated CD8+ cells were initially analyzed for CD62L and CD44 expression or CD49b expression (Fig. 5, left histograms). The CD44+CD62L− cells were then analyzed for CD49b expression, while the CD49b+CD8+ and CD49b−CD8+ cells were analyzed for CD44 and CD62L expression (Fig. 5, right histograms). This analysis demonstrated that when cells were gated for TEM markers (CD44+CD62L−) the CD8 cells in this population were primarily CD49b+ (70, 79, 67, and 56% in PBL, spleen, BM, and dLN, respectively). Also, the majority of gated CD49b+ cells were of the TEM phenotype (87, 88, 87, and 59% in PBL, spleen, BM, and dLN, respectively). The largest population of lymphocytes in the CD49b−CD8+ gate were CD44− and CD62L+ (60, 47, 49, and 58%, in PBL, spleen, BM, and dLN, respectively). This is considered a naive T cell phenotype. Lymphocytes with a T central memory (TCM) phenotype (CD44+CD62L+) accounted for between 12% in BM and 23% in the spleen when CD49b− cells were analyzed. Interestingly, in the dLN, the TCM population was 33% of the gated CD49b+ cells. Although still not the majority of the CD49b+ cells, the dLN was the only tissue in which the majority of TCM were CD49b+. This may indicate that in the dLN these cells are being activated.

FIGURE 5.

Expression of TEM markers on splenic CD49b+CD8+ cells. A/J mice were vaccinated twice weekly as described in Fig. 1 with AGN2a/CD80, AGN2a/CD137L, or AGN2a-CD80/137L (AGN2a/DP). Spleens were harvested 5 days after the last immunization and CD8+ lymphocytes were analyzed by flow cytometry. Specifically, gated CD8+ cells were first analyzed for CD44 and CD62L expression (top) or for CD49b expression (bottom). CD62L−CD44+ cells were then analyzed for CD49b expression (top), while CD49b− and CD49b+ cells were analyzed for CD44 and CD62L expression (bottom). These data are representative of two independent experiments (three mice per experiment).

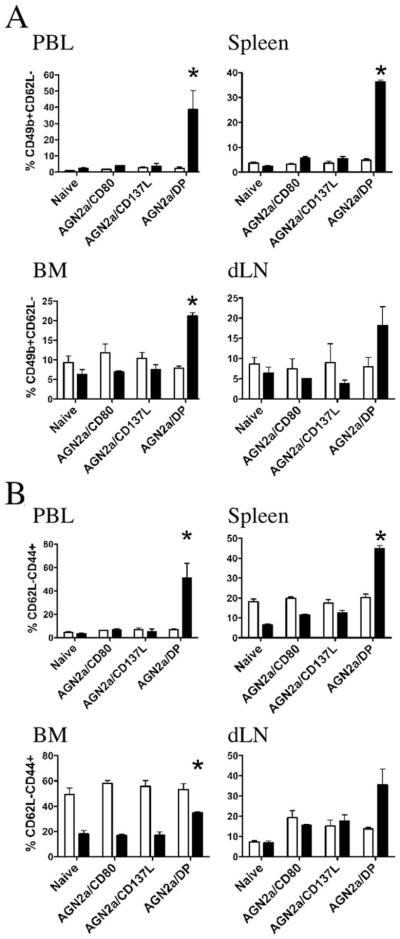

Based on the results in Fig. 5, we then analyzed the comparative ability of each of our cell-based vaccines to induce the CD49b+CD62L− population in the CD4 and CD8 lymphocyte subsets (Fig. 6A). This analysis clearly demonstrated that it was our dual-expressing vaccine, i.e., both CD80 and CD137L, which induced a CD49b+CD62L− phenotype. This was true for each of the lymphoid tissues tested. When the CD44+CD62L− TEM population was examined in CD4 and CD8 subsets, similar results were seen in all tissues tested except for BM (Fig. 6B). In the BM, CD4 cells had a uniform elevation in CD44, which held true in the unvaccinated (naive) mice as well. This analysis illustrates that CD4 TEM are elevated in BM and to some degree in the spleens of nonvaccinated mice. In PBL, the expression was low and remained low. Only in the dLN did vaccination appear to slightly expand the CD4 TEM population (Fig. 6B). Thus, alterations in CD4 TEM do not correlate to the vaccine-induced response, highlighting that early immune responses after treatment with a cell-based vaccine are better tracked by following changes in differentiated CD8 cells.

FIGURE 6.

Analysis of CD4 and CD8 cells for expression of CD49b, CD44, and CD62L. A/J mice were vaccinated twice weekly as described in Fig. 1 with AGN2a/CD80, AGN2a/CD137L, or AGN2a-CD80/137L (AGN2a/DP). The indicated tissues (peripheral blood (PBL), spleen, BM, and vaccine dLN) were harvested 5 days after the last immunization, and CD8+ lymphocytes were analyzed by flow cytometry. A, The percentages of CD49b+CD62L− cells in gated CD4 (□) and CD8 (■) cells from the indicated groups of vaccinated and nonvaccinated (naive) mice are shown. B, The percentages of CD62L−CD44+ cells in gated CD4 (□) and CD8 (■) cells as in A. Each bar represents the average data of three mice in each group (representative of two separate experiments). A and B, *, p < 0.05 when compared with naive, AGN2a/CD80-, or AGN2a/CD137L-vaccinated mice. Values of p values were determined by the Student t test.

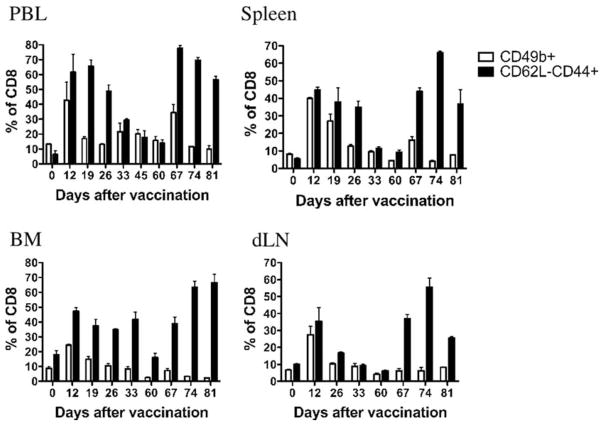

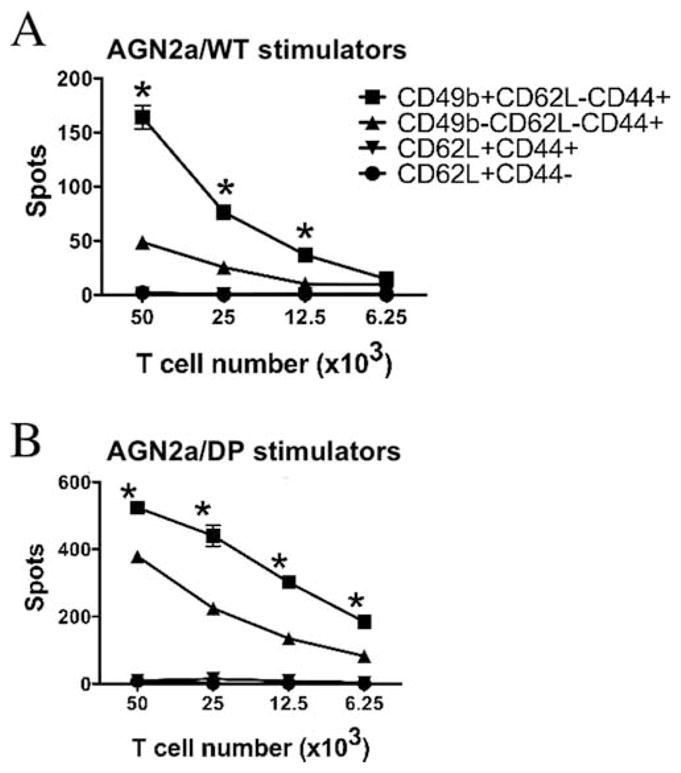

To determine whether there was a functional difference in cells ELISPOT assays were expressing CD49b and TEM markers, IFN-γ conducted on sorted populations using wild-type AGN2a stimulator cells (Fig. 7A) or AGN2a-CD80/137L (AGN2a/DP) vaccine cells as the stimulator (Fig. 7B). With either target, the CD62L+ populations failed to produce IFN-γ in response to coculture with tumor. We included both wild-type and the vaccine line as stimulators in the assays since previous work in our laboratory had demonstrated that the presence of the immune costimulatory molecules on the surface of AGN2a makes it a far more avid target. This can readily be seen by the increase in spot number seen with AGN2a-CD80/137L stimulators (Fig. 7B). The larger difference seen when wild-type AGN2a cells were used as the target may indicate that CD49b provides a direct cell-cell adhesion function, that the CD49b+ population expresses other adhesion and activation markers, or that the threshold of activation is lower when the CD80 and CD13L costimulatory molecules are expressed on the tumor.

FIGURE 7.

Functional analysis of CD49b+CD8+ cells. The following CD8+ cell subsets were purified from the spleens of AGN2a-CD80/137L-vaccinated mice by flow cytometric sorting: CD49b+CD62L−CD44+ (■), CD49b−CD62L−CD44+ (▲), CD62L+CD44+ (▼), and CD62L+CD44− (●). IFN-γ ELISPOT assays were done in the presence of either wild-type (A, WT) or vaccine (B, AGN2a/DP) tumor cell stimulators over a range of T cell numbers per well. The data (mean ± SD of triplicate wells) are representative of two separate experiments.*, p < 0.01 when compared with CD49b−CD62L−CD44+ cells. Values of p were determined by two-way ANOVA analysis.

Analyzing the persistence of CD49b on CD8 cells after vaccination

Thus far our data indicated that CD49b is a key marker for the most highly activated TEM induced by AGN2a-CD80/137L 5 days after the second of two weekly vaccinations (i.e., at the peak of response). To determine whether CD49b expression is still increased at later stages in the immune response to our cell-based vaccine, we monitored CD49b expression at various time points after the vaccine was administered in peripheral blood, spleen, BM, and vaccine dLN tissues (Fig. 8). Tissues were harvested at set time points and CD8 cells were analyzed for either the expression of CD49b or the CD44+CD62L− TEM phenotype. Consistent with our previous results, percentages of CD8 cells expressing CD49b were increased on day 12 (5 days after the second of two weekly vaccinations). This population returned to the levels seen in naive mice by day 60. However, when mice were boosted with a s.c. vaccination of AGN2a-CD80/137L on day 60, a less robust increase in CD49b expression was seen in peripheral blood and spleen, and little or no increase was seen in CD8 cells from BM or vaccine dLN. This was in contrast to the changes in percentages of CD8 cells expressing the CD44+CD62L− TEM phenotype. This phenotype was expressed to a far greater degree upon rechallenge and even exceeded the initial response to our cell-based vaccine. These results indicate that the real value in CD49b lay in its ability to identify the initial activation of antitumor effector cells as opposed to those involved in a recall response.

FIGURE 8.

Expression of CD49b on CD8 cells after primary vaccination, but not on CD8 cells after a recall immune response. Mice were vaccinated with AGN2a-CD80/137L on days 0 and 7 and boosted with the same vaccine on day 60. At each indicated time point, lymphocytes in peripheral blood (PBL), spleen, BM, and vaccine dLN were analyzed for percentages of CD8 cells expressing CD49b (□) or expressing a CD62L-CD44+ phenotype (■). These data are from one of two separate experiments.

CD8 T cell migration mediated by CD49b in vitro

One function of integrins such as VLA-2 is to bind extracellular matrix components such as laminin and collagen. To determine whether tumor vaccine-reactive CD8 cells express CD49b as part of a functional collagen receptor, we used an in vitro collagen migration assay. A/J mice were vaccinated with 5 × 106 irradiated AGN2a-CD80/137L cells as in previous experiments, and CD8+ splenocytes from immunized animals were purified into four cell populations by flow cytometry: CD44−CD62L+, CD44+CD62L+, CD44+CD62L−CD49b+, and CD44+CD62L−CD49b−. Cells (1 × 105) from each subset were cultured on top of a solid collagen matrix (Matrigel) in the presence of IL-2 (required for CD8 T cell viability). After 48 h of culture, the number of cells that had infiltrated the collagen matrix was counted. Collagen invasion by the CD49b TEM population was the most robust (Fig. 9A). The percentage invasion rates for all cells added to the wells were 30, 8, 0.4, and 0% for CD44+CD62L−CD49b+, CD44+CD62L−CD49b−, CD44+CD62L+, and CD44−CD62L+ cells, respectively. The experiment was repeated using the CD44+CD62L−CD49b+ population in the presence of anti-VLA-2 Ab to more strictly define the VLA-2 dependence of collagen invasion by vaccine-responding CD8 T cells. Blockade of VLA-2 with Ab resulted in a decrease of ~66% of the matrix invasion capability (Fig. 9B).

FIGURE 9.

Collagen matrix invasion by CD49b+ cells. A, Splenocytes from AGN2a-CD80/137L-vaccinated mice were harvested and the following CD8+ cell subsets were purified by flow cytometric sorting: CD49b+CD62L−CD44+, CD49b−CD62L−CD44+, CD62L+CD44+, and CD62L+CD44−. Cells (105) of each purified population were plated on solid Matrigel, and the numbers of cells invading the matrix were counted after 48 h.*, p < 0.01 when compared with the other three cell populations. B, CD49b+CD62L−CD44+ sorted cells were cultured on Matrigel with no Ab (control), isotype control Ab, or 5 μg/ml anti-CD49b (VLA-2) Ab. Cell migration was then determined after 48 h. * and**, p < 0.01 when compared with the control cells. The results are the averages and SDs of triplicate wells that were repeated three times. Values of p were determined by the Student t test.

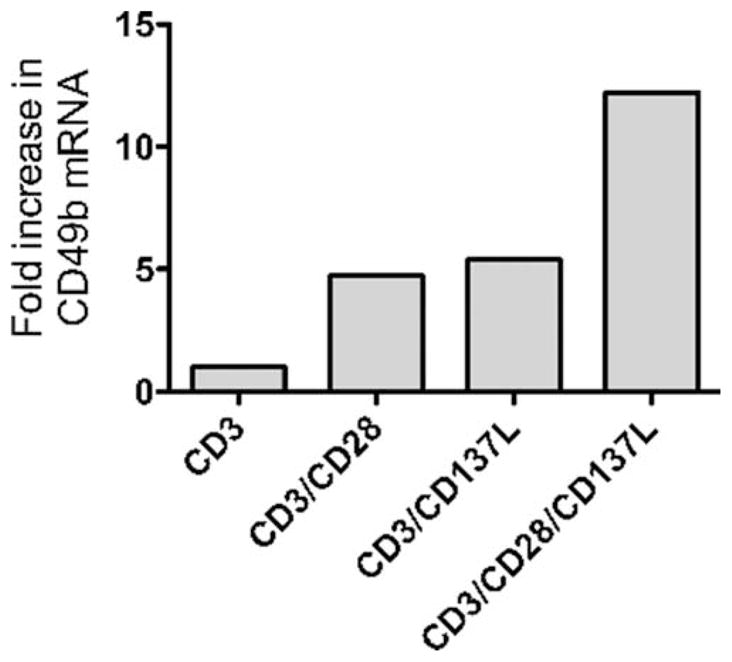

Induction of CD49b mRNA by costimulatory molecule activation

Based on our observation that AGN2a-CD80/137L vaccination induced a CD49b+ TEM population in vivo, we determined whether T cell activation with these ligands could directly induce CD49b expression in vitro. Splenic CD8+ T cells were isolated from naive mice and then coincubated with K562-based aAPC. The aAPC expressed either CD32 (Fc receptor) or CD32 and CD137L. Irradiated aAPC were loaded with anti-CD3 and/or anti-CD28 Ab and cocultured with CD8 T cells in the presence of IL-2. Viable cells were harvested and counted 72 h later and cDNA was generated for real-time quantitative PCR analysis of CD49b mRNA expression levels (see Materials and Methods). When the signal for CD49b was normalized to that induced by anti-CD3 alone, the presence of either anti-CD28 or CD137L increased the level of CD49b message induced by anti-CD3 ~5-fold (Fig. 10). When all three signals were included (anti-CD3, anti-CD28, and CD137L) CD49b expression increased 12-fold. This establishes a direct link between costimulation with CD137L and anti-CD28 and the expression of CD49b on CD8+ T cells. Our experimental results suggest that during the initiation of an immune response that CD49b functions as an adhesion molecule on the most activated TEM and may thereby increase the ability of TEM to enter tissues and mediate tumor destruction.

FIGURE 10.

Induction of CD49b mRNA in CD8 cells. Splenic CD8 T cells were purified from naive A/J mice by immunomagnetic sorting and then cocultured with irradiated CD137L+ or CD137L− aAPC coated with anti-CD3 and/or anti-CD28 Abs, as indicated on the x-axis (see Materials and Methods for details). The CD8 cells were harvested after 72 h of culture and mRNA copy number for CD49b was determined by quantitative real-time PCR. HPRT was used as an endogenous control for signal normalization, and the levels of CD49b message induced by anti-CD3-loaded aAPC were used as an internal standard. The results are shown as fold increase in the level of CD49b mRNA. These data are representative of three separate experiments.

Discussion

In an effort to discover how our cell-based vaccine, featuring the expression of both CD80 and CD137L activates highly active antitumor immunity, we found that a new population of CD49b+CD8 T cells arose. Moreover, CD49b was expressed on the most active antitumor effector cells, the CD49b+ effectors were tumor specific, and they did not exhibit NK activity. Key to CD49b expression was the presence of both CD137L and CD80 on the vaccine cell surface. The addition of CD86 to CD80 did not induce a similar highly active antitumor effector cell population (11). CD137L triggers an independent signaling pathway that cooperatively signals with CD28 in T cell activation (12). Studies have shown that CD137 signaling in T cells induces an independent TNFR-associated factor 2 signaling pathway from CD28, enhances cell cycle progression, potentiates CD8 T cell survival, and activates components of the TCR signaling pathway (25–29). In sum, CD49b expression appears to be up-regulated upon activation due to strong secondary costimulatory signals. Given the high level of antitumor activity that CD49b+ cells displayed upon immediate harvest from vaccinated mice, we saw this as an opportunity to explore the differences in lymphocyte populations induced by a cancer vaccine that could be monitored in future clinical cancer studies. To date, surrogate markers that indicate vaccine sufficiency in tumor models have been lacking. In looking at more global effects of the vaccine response after AGN2a-CD80/137L vaccination, we observed both decreased CD4:CD8 ratios and lower cell surface expression of CD8 (Fig. 1). This indicates that broad phenotypic changes as well as specific functional markers of immune activation could be monitored in our vaccinated animals.

CD49b is the α-chain of integrin VLA-2 (23). In the AGN2a-CD80/137L-vaccinated mice, a large population of CD8+CD49b+ cells was seen in the spleen (39%), BM (25%), peripheral blood (41%), and vaccine dLN cells (26%), as detected by either the DX5 or HMα 2 Ab. In an infectious disease model, Kassioatis et al. (30) found CD49b to be expressed on a CD4 T memory subset that was associated with IFN-γ production. Although in agreement with the finding that CD49b expression was associated with Th1-like responses, we did not observe increased expression of CD49b on CD4 cells upon AGN2a-CD80/137L vaccination. Our changes in populations expressing CD49b were restricted to CD8 cells.

To demonstrate that the vaccine-induced expression of CD49b is associated with the increased antitumor effectiveness seen in vivo, we tested in vitro antitumor activity by ELISPOT, the production of soluble cytokines, and direct cellular cytotoxicity assays (Fig. 3). In each assay the most active antitumor effectors were those that expressed CD49b, and the tumor-specific CD49b+ cells did not exhibit NK activity. The spontaneous production of IFN-γ by CD49b cells isolated from vaccinated animals and placed in culture, although lower than when tumor cells were present as stimulators, indicates that this population has already been activated and is in the process of responding to vaccine in vivo (Fig. 3C). When tested in vivo for antitumor activity, CD49b+ cells were again shown to be superior in mediating tumor destruction. When tumor-bearing mice were treated by direct adoptive immunotherapy with CD8 T cell populations from AGN2a-CD80/137L-treated mice, no tumor protection was seen in the CD49b− populations, while 50% of the mice treated with CD49b+ cells survived (Fig. 4). Since the T cells were administered by tail vein injection and the tumor was introduced by s.c. vaccination, this indicates that the CD49b+ cells have the ability to circulate, extravasate, and mediate strong antitumor activity in peripheral tissues. An intermediate level of protection (20% survival) was seen when unfractionated CD8 cells were tested, indicating the importance of the number of CD49b+ cells infused. One of the first roles described for VLA-2 was the finding that VLA-2 was expressed on polymorphonuclear neutrophils that had extravasated, in contrast to polymorphonuclear neutrophils found in the blood (31–33). Abs against VLA-1 and VLA-2, the major collagen-binding integrins, significantly inhibited the effector phase of the inflammatory immune response in mouse model systems, implying a requirement for these receptors (33). Thus, it appears that leukocyte attachment and extravasation through vascular endothelium cannot be separated from the immune reactions mediated by these cells.

VLA-2 mediates binding to collagen and also to laminin when expressed on certain cells types, but not when expressed on platelets or fibroblasts (34–36). In mammals, there are 19 different collagen types. To summarize a large body of work, it appears that α2β1 integrin may favor binding to fibrillar collagen (like type I), while α1β1 (VLA-1) may favor binding to basement membrane types (like type IV) (37–39). VLA-1 and VLA-2 differ directly in that VLA-1 can bind transmembrane type XIII collagen but not type II, while VLA-2 has the opposite binding characteristics with regard to these two collagen types (40, 41). The complexity of the extracellular matrix necessitates a large family of receptors to be present in multicellular organisms to mediate movement throughout the tissues and undoubtedly VLA-2 plays a role in this process. Collagen is one of the most abundant molecules in the tissue spaces through which cells must migrate, and would clearly serve to signal T cells as to their relative anatomic location (33). The possibility that VLA-2 serves as a specific addressin-like function for surveillance of the s.c. space is a compelling hypothesis and would support our finding of higher antitumor activity displayed by these cells.

VLA-2 also appears to have additional functional importance for T cell biology. VLA-2 induction on T cells in inflammatory lesions is proposed to prevent Fas-mediated apoptosis by preventing Fas ligand expression and the sparing of T cells from activation-induced cell death by culture on type I collagen (42). Amplification of TCR-mediated signaling has also been reported when functional assays are conducted on collagen-coated vessels (43, 44).

As Abs to NK cell surface markers are studied in greater detail, it has become clear that the expression of these markers is far more complex than initially thought. Abs to NK1.1 bind to none, one, or both proteins expressed from the Klrb1b/NKR-P1B and Klrb1c/NKR-P1C genes, depending on the mouse strain studied (45, 46). These epitopes can also be expressed on NKT cells and some cultured monocytes. A/J mice do not express either epitope and thus we began studies of NK populations in vaccinated mice with the DX5 Ab. However, we were soon struck by the fact that what we considered to be standard CD3+CD8+CTLs expressed high levels of CD49b as indicated by DX5 staining. The importance of these CD8 effector cells in the immune response to neuroblastoma is highlighted in this study by our ability to eradicate tumors in mice by the simple transfer of CD49b+CD8 cells from vaccinated mice (Fig. 4) and Ab depletion studies in our earlier work (9, 47). The in vivo biology of CD137L-induced effectors is clearly more complex as recent studies of human cells by Zhang et al. (48) have demonstrated that NKG2D is up-regulated on CTL expanded by aAPC expressing anti-CD3/4-1BBL (CD137L). This is significant because NKG2D does directly impart killing capacity. Supportive of our findings, Zhang et al. (48) demonstrate that their procedure expands memory cells that may potentially target viral or self-Ags.

In exploring the biology of the T cell response to our cell-based vaccine, we found that the CD8 cells expressing CD49b could be classified as TEM based on CD44 and CD62L expression (Fig. 6). ELISPOT data demonstrated that if CD8 TEM were fractionated according to CD49b expression, the CD49b+ had the strongest IFN-γ ELISPOT activity (Fig. 7). This also held true for cytolytic activity (Fig. 3A). Although expression of TEM memory markers and expression of CD49b were not absolutely linked, there was a large degree of overlap (Fig. 5). Given the high degree of effector function present in TEM and the ability of CD49b to mediate binding to extracellular matrix components (as demonstrated in Fig. 9), we hypothesize that CD49b+ TEM are poised to enter tissue and mediate Ag-specific antitumor immune function. This point is emphasized further by the ability of CD49b cells injected i.v. to abrogate growth of tumor cells that had been injected s.c. 24 h earlier.

The induction of CD49b on CD8 TEM upon initial vaccination with AGN2a-CD80/137L was clear and compelling (Fig. 8, day 12). Given the relationship between vaccine-induced VLA-2+ cells and TEM, we sought to determine whether CD49b expression was also a component of the recall response to our cell-based neuroblastoma vaccine. To our surprise, in all tissues tested (peripheral blood, spleen, BM, and vaccine dLN), CD49b+ cells were now a minor component of the response (Fig. 8). As expected, the total TEM response (CD62L−CD44+ cells) appeared to be as strong or stronger than the primary TEM response (Fig. 8). Thus, DX5/CD49b-expressing CD8 T cells are a hallmark of a strong initial response but do not appear to serve as a component of long-term recall memory responses. One hypothesis is that once cells express CD49b, they are terminally differentiated TEM and will not survive once effector function has been conducted. Alternatively, CD49b may confer the ability to enter peripheral tissues, and when TEM express this marker they reside in nonlymphoid tissues long-term where they can be rapidly activated upon Ag encounter.

In our final experiment, we sought to establish a mechanism linking the combined costimulation of T cells via CD28 and CD137 (4-1BB) with the expression of CD49b. The transcriptional control region of VLA-2 is composed of a core promoter, a silencer, and a tissue-specific enhancer (22). The promoter core-binding domain shows Sp1, AP1, AP2, Gata3, and Pu.1 binding sites (49). In megakaryocytes, epithelial cells, and fibroblasts expression of α2 is regulated at the transcriptional level, making the presence of mRNA a good measure of promoter activity (50, 51). Given the inducible control of VLA-2 expression, we are confident that our results with CD8 T cells establish a direct link between combined T cell stimulation via CD28 and CD137 and the surface expression of CD49b (Fig. 10). In short-term activation assays using aAPC, the combined signaling of CD28 and CD137 induced CD49b mRNA to a far greater degree than either costimulatory molecule alone when combined with CD3 signaling. From this we can conclude that strong T cell activation generated by multiple costimulatory ligands induces CD49b mRNA, which correlates to differentiation into the most highly activated antitumor effector cells. In future studies, we will determine whether the induction of this highly active cell population can occur in tumor-bearing animals and, if so, under what conditions. And although we have established a link to CD49b expression and the high level of antitumor immunity mediated by these cells, it is likely that other activation or effector molecules up-regulated in concert with CD49b are directly responsible for the enhanced tumor killing seen in our assays. The expression of CD49b on TEM in human cancer vaccine trials may serve as an effective surrogate for the successful initial induction of a Th1-like effector cell population that should have strong antitumor activity. However, the lack of CD49b on cells engaged in a recall response may imply that alternate receptors now determine the migratory pattern of activated CD8 cells throughout the organism.

Footnotes

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service Grant CA100030, American Cancer Society Internal Research Grant IRG-170, and the Midwest Athlete’s Against Childhood Cancer (MACC Fund, Inc., Milwaukee, WI).

Abbreviations used in this paper: aAPC, artificial APC; HPRT, hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase; BM, bone marrow; dLN, draining lymph node; DP, double positive; TEM, effector memory T cell; TCM, central memory T cell.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Klaasen RJ, Trebo MM, Koplewitz BZ, Wietzman SS, Calderwood S. High-risk neuroblastoma in Ontario: a report of experience from 1989 to 1995. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;25:8–13. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200301000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maris JM, Hogarty MD, Bagatell R, Cohn SL. Neuroblastoma. Lancet. 2007;369:2106–2020. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60983-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matthay KK, Villablanca JG, Seeger RC, Stram DO, Harris RE, Ramsay NK, Swift P, Shimada H, Black CT, Brodeur GM, et al. Treatment of high-risk neuroblastoma with intensive chemotherapy, radiotherapy, autologous bone marrow transplantation, and 13-cis-retinoic acid. New Engl J Med. 1999;341:1165–1173. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910143411601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inoue M, Nakano T, Yondea A, Nishikawa M, Yumura-Yagi K, Sakata N, Yasui M, Okamura T, Kawa K. Graft-versus-tumor effect in a patient with advanced neuroblastoma who received HLA haplo-identical bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;32:103–106. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowman L, Grossmann M, Rill D, Brown M, Zhong WY, Alexander B, Leimig T, Coustan-Smith E, Campana D, Jenkins J, et al. IL-2 adenovector-transduced autologous tumor cells induce anti-tumor immune responses in patients with neuroblastoma. Blood. 1998;92:1941–1949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rousseau RF, Haight AE, Hirschmann-Jax C, Yvon ES, Rill DR, Mei Z, Smith SC, Inman S, Cooper K, Alcoser P, et al. Local and systemic effects of an allogeneic tumor cell vaccine combining human lymphotactin with interleukin-2 in patients with advanced or refractory neuroblastoma. Blood. 2003;101:1718–1726. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russell HV, Strother D, Mei Z, Rill D, Popek E, Biagi E, Yvon E, Brenner M, Rousseau R. Phase I trial of vaccination with autologous neuroblastoma tumor cells genetically modified to secrete IL-2 and lymphotactin. J Immunother. 2007;30:227–233. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000211335.14385.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prigione I, Corrias MV, Airoldi I, Raffaghello L, Morandi F, Bocca P, Cocco C, Ferrone S, Pistoia V. Immunogenicity of human neuroblastoma. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1028:69–80. doi: 10.1196/annals.1322.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson BD, Yan X, Schauer DW, Orentas RJ. Dual expression of CD80 and CD86 produces a tumor vaccine superior to single expression of either molecule. Cell Immunol. 2003;222:15–26. doi: 10.1016/s0008-8749(03)00079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson BD, Gershan JA, Natalia N, Zujewski H, Weber JJ, Yan X, Orentas RJ. Neuroblastoma cells transiently transfected to simultaneously express the co-stimulatory molecules CD54, CD80, CD86, and CD137L generate antitumor immunity in mice. J Immunother. 2005;28:449–460. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000171313.93299.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan X, Johnson BD, Orentas RJ. Murine CD8 lymphocyte expansion in vitro by artificial antigen-presenting cells expressing CD137L (4-1BBL) is superior to CD28, and CD137L expressed on neuroblastoma expands CD8 tumor-reactive effector cells in vivo. Immunology. 2004;112:105–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01853.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melero I, Bach N, Hellstrom KE, Aruffo A, Mittler RS, Chen L. Amplification of tumor immunity by gene transfer of the co-stimulatory 4-1BB ligand: synergy with the CD28 co-stimulatory pathway. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:1116–1121. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199803)28:03<1116::AID-IMMU1116>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilcox RA, Tamada K, Strome S, Chen L. Signaling through NK cell-associated CD137 promotes both helper function for CD8+ cytolytic T cells and responsiveness to IL-2 but not cytolytic activity. J Immunol. 2002;169:4230–4236. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cannons JL, Lau P, Ghumman B, DeBenedette MA, Yagita H, Okumura K, Watts TH. 4-1BB ligand induces cell division, sustains survival, and enhances effector function of CD4 and CD8 T cells with similar efficacy. J Immunol. 2002;167:1313–1324. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim YJ, Mantel PM, June CH, Kim SH, Kwon BS. 4-1BB costimulation promotes human T cell adhesion to fibronectin. Cell Immunol. 1999;192:13–23. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1998.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilcox RA, Tamada K, Flies DB, Zhu G, Chapoval AI, Blazar BR, Kast WM, Chen L. Ligation of CD137 receptor prevents and reverses established anergy of CD8+ cytolytic T lymphocytes in vivo. Blood. 2004;103:177–184. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilcox RA, Flies DB, Zhu G, Johnson AJ, Tamada K, Chapoval AI, Strome SE, Pease LR, Chen L. Provision of antigen and CD137 signaling breaks immunological ignorance, promoting regression of poorly immunogenic tumors. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:651–659. doi: 10.1172/JCI14184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andreasen SO, Thomsen AR, Koteliansky VE, Novobrantseva TI, Sprague AG, de Fougerolloes AR, Christensen JP. Expression and functional importance of collagen-binding integrins, α1/β1 and α2/β1, on virus-activated T cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:2804–2811. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kambayashi T, Assarsson E, Chambers BJ, Ljunggren HG. Expression of the DX5 antigen on CD8+ T cells is associated with activation and subsequent cell death or memory during influenza infection. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1523–1530. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200105)31:5<1523::AID-IMMU1523>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slifka MK, Pagarigan RR, Whitton JL. NK Markers are expressed on a high percentage of virus-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2000;164:2009–2015. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edelson BT, Li Z, Pappan LK, Zutter MM. Mast-cell-mediated inflammatory responses require the α2β1 integrin. Blood. 2004;103:2214–2220. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zutter MM, Painter AD, Staatz WD, Tsung YL. Regulation of α2 integrin gene expression in cells with megakaryocytic features: a common theme of three necessary elements. Blood. 1995;86:3006–3014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hemler ME, Jacobson JG, Strominger JL. Biochemical characterization of VLA-1 and VLA-2. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:15246–45252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campanero MR, Arroyo AG, Pulido R, Ursa A, de Matias MS, Sanchez-Mateos P, Kassner PD, Chan BMC, Hemler ME, Corbi AL, et al. Functional role of α2/β1 and α4/β1 integrins in leukocyte intercellular adhesion induced through the common β1 subunit. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:3111–3119. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830221213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saoulli K, Lee SY, Cannons JL, Yeh WC, Santana A, Goldstein MD, Bangia N, DeBenedette MA, Mak TW, Choi Y, Watts TH. CD28-independent, TRAF2-dependent costimulation of resting T cells by 4-1BB ligand. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1849–1862. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.11.1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee HW, Nam KO, Park SJ, Kwon BS. 4-1BB enhances CD8+ T cell expansion by regulating cell cycle progression through changes in expression of cyclins D and E and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27kip1. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:2133–2141. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takahashi C, Mittler RS, Vella AT. Cutting edge: 4-1BB is a bona fide CD8 T cell survival signal. J Immunol. 1999;162:5037–5040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nam KO, Kang H, Shin SM, Cho KH, Kwon B, Kwon BS, Kim SJ, Lee HW. Cross-linking of 4-1BB activates TCR-signaling pathways in CD8+ T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2005;174:1898–1905. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guinn BA, Bertram EM, DeBenedatte MA, Berinstein NL, Watts TH. 4-1BBL enhances anti-tumor responses in the presence or absence of CD28 but CD28 is required for protective immunity against parental tumors. Cell Immunol. 2001;210:56–65. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2001.1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kassiotis G, Gray D, Kiafard Z, Zwirner J, Stockinger B. Functional specialization of memory Th cells revealed by expression of integrin CD49b. J Immunol. 2006;177:968–975. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Werr J, Johansson J, Eriksson EE, Hedqvist P, Ruoslahti E, Lindbom L. Integrin α2β1 (VLA-2) is a principal receptor use by neutrophils for loco-motion in extravascular tissue. Blood. 2000;95:1804–1809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ridger VC, Wagner BE, Wallace WA, Hellewell PG. Differential effects of CD18, CD29, and CD49 integrin subunit inhibition on neutrophil migration in pulmonary inflammation. J Immunol. 2001;166:3484–3490. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.5.3484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Fougerolles AR, Sprague AG, Nickerson-Nutter CL, Chi-Rosso G, Rennert PD, Gardner H, Gotwals PJ, Lobb RR, Koteliansky VE. Regulation of inflammation by collagen-binding inegrins α1β1 and α2β1 in models of hypersensitivity and arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:721–729. doi: 10.1172/JCI7911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elices MJ, Hemler ME. The human integrin VLA-2 is a collagen receptor on some cells and a collagen/laminin receptor on others. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:9906–9910. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.24.9906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Languino LR, Gehlsen KR, Wayner E, Carter WG, Engvall E, Ruoslahti E. Endothelial cells use α2β1 integrin as a laminin receptor. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:2455–2462. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.5.2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chan BMC, Matsuura N, Takada Y, Zetter BR, Hemler ME. In vitro and in vivo consequences of VLA-2 expression on rhabdomyosarcoma cells. Science. 1991;251:1600–1602. doi: 10.1126/science.2011740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prockop JD. Collagens: molecular biology, diseases, and potential for therapy. Ann Rev Biochem. 1995;64:403–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.002155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kern A, Eble J, Golbik R, Kühn K. Interaction of type IC collagen with the isolated integrins α1β1 and α1β2. Eur J Biochem. 1993;215:151–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kern A, Marcantonio EE. Role of the I-domain in collagen binding and activation of the integrins α1β1 and α1β2. J Cell Physiol. 1998;176:634–641. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199809)176:3<634::AID-JCP20>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nykvist P, Tu H, Ivaska J, Käpylä J, Pihlajanemi T, Heino J. Distinct recognition of collagen subtypes by α1β1 and α2β1 integrins. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8255–8261. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.8255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lundberg S, Lindholm J, Lindbom L, Hellstrom PM, Werr J. Integrin α2β1 regulates neutrophil recruitment and inflammatory activity in experimental colitis in mice. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:172–177. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000217765.96604.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gendron S, Couture J, Aoudjit F. Collagen type I signaling reduces the expression and the function of human receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL) in T lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:3673–3682. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miyake S, Sakurai T, Okumura K, Yagita H. Identification of collagen and laminin receptor integrins on murine T lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:2000–2005. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rao WH, Hales JM, Camp RD. Potent costimulation of effector T lymphocytes by human collagen type I. J Immunol. 2000;165:4935–4940. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.4935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carlyle JR, Mesci A, Ljutic B, Belanger S, Tai LH, Rouselle E, Trioke AD, Proteau MF, Makrigiannis AP. Molecular and genetic basis for strain-dependent NK1.1 alloreactivity of mouse NK cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:7511–7524. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carlyle JR, Martin A, Mehra A, Attisano L, Tsui FW, Zuniga-Pflucker JC. Mouse NKR-P1B, a novel NK1.1 antigen with inhibitory function. J Immunol. 1999;162:5917–5923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson BD, Jing W, Orentas RJ. CD25+ regulatory T cell inhibition enhances vaccine-induced immunity to neuroblastoma. J Immunother. 2007;30:203–214. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000211336.91513.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang H, Snyder KM, Suhoski MM, Maus MV, Kapoor V, June CH, Mackall CL. 4-1BB is superior to CD28 costimulation for generating CD8+ cytotoxic lymphocytes for adoptive immunotherapy. J Immunol. 2007;179:4910–4918. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zutter MM, Santoro SA, Painter AS, Tsung YL, Gafford A. The human α2 integrin gene promoter. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:463–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jacquelin B, Rozenshteyn D, Kanaji S, Koziol JA, Nueden AT, Kunicki TJ. Characterization of inherited differences in transcription of the human integrin α2 gene. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:23518–23524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102019200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li TT, Larrucea S, Suza S, Leal SM, López JA, Rubin EM, Nieswandt B, Bray PF. Genetic variation responsible for mouse strain differences in integrin α2 expression is associated with altered platelet responses to collagen. Blood. 2004;103:3396–3402. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]