Abstract

Background

To purpose of this study was to evaluate the activity and toxicity of dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, and carboplatin (DAC) combination therapy in children with newly diagnosed large-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and to estimate the event-free and overall survival rates achieved when DAC is incorporated into a conventional regimen.

Patients and Methods

From 1991 to 1997, 20 boys and 5 girls aged 4.2 to 17.7 years who had stage III (n=21) or stage IV (n=4) large-cell NHL were treated on this study. DAC therapy was administered at the beginning of the induction phase in 2 sequential cycles and incorporated throughout a continuation phase (modified from the ACOP+ regimen) with doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine and dexamethasone. The total duration of treatment was approximately 10 months.

Results

DAC therapy yielded a response in 22 of 25 patients (88%, 95% CI 68%-97%): complete remission in 13 cases (52%) and partial response in 9 (36%). After additional treatment with doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and dexamethasone, complete remission was attained in 18 patients (72%) and partial remission in 3 (12%). The event-free survival rate (±SE) was 64% ± 9% and the overall survival rate was 80% ± 8% at 5 years.

Conclusion

The DAC regimen is well tolerated and effective for pediatric large-cell NHL.

Keywords: Dexamethasone, Cytarabine, Carboplatin, Childhood, Large cell, Lymphoma

INTRODUCTION

The non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) of childhood are primarily high-grade lesions, as defined by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Working Formulation.(1) When classified according to the more recent WHO classification system, the pediatric NHLs comprise the Burkitt, lymphoblastic, and large-cell subtypes.(2) Significant progress has been made in improving treatment outcomes for children with these tumors. The most effective treatments for the Burkitt lymphomas are intensive, cyclophosphamide-based regimens given over a relatively short period (4-8 months),(3-13) whereas those for lymphoblastic disease are often derived from regimens used to treat high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), which feature intensive chemotherapy given over a prolonged period (18-30 months).(14-20) Determining the optimal therapy for large-cell NHL has proved problematic, partly because of the biologic heterogeneity of these tumors and because of the wide spectrum of treatment strategies reported.(14, 21-33) For example, in Europe, treatment has been based on immunophenotype, whereas in the United States, patients have historically been treated according to histologic findings and disease stage, regardless of immunophenotype.(10, 12, 33, 34) The histology-directed treatment approach has resulted in a 50%-70% long-term event-free survival rate for children with advanced-stage large-cell NHL.(14, 19, 21, 28-32) (see Table 1) The histology-based treatment approaches rely heavily on anthracyclines and alkylating agents and are frequently CHOP-based regimens; however, some regimens include other agents such as methotrexate, mercaptopurine, bleomycin, and cytarabine.

Table 1.

Reported Treatment Outcomes After Histology-Directed Therapy for Advanced-Stage Large-Cell NHL

| Regimen | No. of Patients | Disease Stage | Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COMP | 30 | III and IV | 3 yr FFS = 46% | (14) |

| LSA2L2 | 16 | III and IV | 3 yr FFS = 44% | (14) |

| Modified LSA2L2 | 13 | III | 3 yr DFS = 70% | (19) |

| ACOP+ | 22 | III and IV | 4 yr DFS = 67% | (30) |

| APO vs. ACOP+ | 62 | III and IV | 5 yr EFS = 72% ± 6% | (31) |

| 58 | III and IV | 5 yr EFS = 62% ± 7% | (31) | |

| COMP vs.aD-COMP | 106 | I – III | 10 yr EFS = 48% ± 4.9% | (28) |

| 14 | IV | 10 yr EFS = 44% | ||

| CHOP | 21 | III and IV | 3 yr EFS = 62% ± 11% | (21) |

| MACOP-B | 11 | III and IV | 3 yr EFS = 55% ± 16% | (32) |

| DAC+ | 25 | III and IV | 3 yr EFS = 64% ± 10% | Present study |

Randomized trial: no significant difference in EFS between COMP and D-COMP.(28)

COMP: cyclophosphamide, vincristine, methotrexate, and prednisone; LSA2L2: cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, daunorubicin, cytarabine, L-asparaginase, BCNU, hydroxyurea, methotrexate, thioguanine; ACOP+: doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, methotrexate (low dose), 6-mercaptopurine, and L-asparaginase; D-COMP: daunorubicin-COMP; CHOP: vincristine, prednisone, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin; MACOP-B: methotrexate, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, and bleomycin; DAC: dexamethasone, cytarabine (high dose), and carboplatin. DFS, disease-free survival; EFS, event-free survival; FFS, failure-free survival; POG, Pediatric Oncology Group.

We and others have demonstrated that the combination of dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin (DHAP) is active against relapsed large-cell NHL.(32) In an effort to improve treatment outcome while reducing the total anthracycline and cyclophosphamide exposure, we incorporated a modified DHAP regimen into the treatment for patients with newly diagnosed large-cell NHL; we used carboplatin instead of cisplatin to minimize ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity. The combination of dexamethasone, cytarabine, and carboplatin (DAC) was administered at the beginning of the induction phase as two sequential courses and incorporated throughout a continuation phase modified from the ACOP+ regimen, which features doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone.(30) Here we report the activity of the initial courses of DAC given during induction, as well as the treatment efficacy and toxicity of the entire treatment program.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Twenty-five children (20 boys, 5 girls; age 4.2-17.7 years) with advanced-stage large-cell NHL, as defined by the NCI Working Formulation, (1) were evaluated and treated at our institution between 1991 and 1997. More recently, classification according to the WHO system was performed in cases for which there was available tissue.(2) Staging workup included CT imaging of neck chest abdomen and pelvis, nuclear imaging (egs., gallium scan, bone scan), bilateral posterior iliac crest bone marrow aspiration and biopsy examination and lumbar puncture for examination of cerebrospinal fluid examination. Upon completion of this workup, lymphomas were staged according to the St. Jude system described by Murphy.(35) The treatment protocol was approved by our institutional review board, and informed consent permission for treatment was obtained for all research participants or their legal guardians.

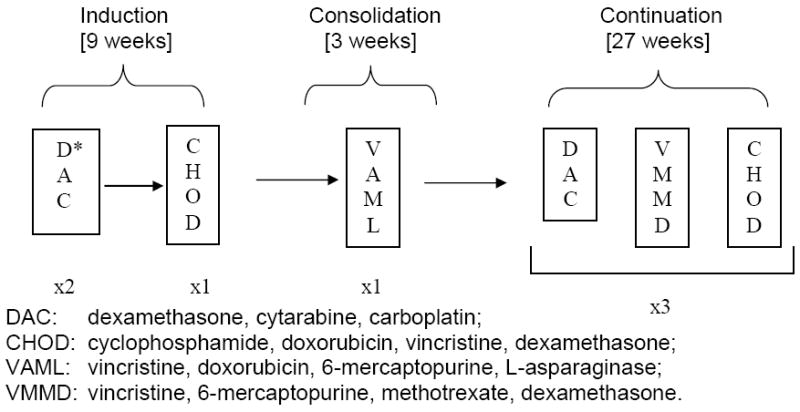

The treatment scheme including dosing and scheduling of therapy, is summarized in Figure 1 and Table 2. Of note, the carboplatin was delivered as a continuous intravenous infusion over 24 hours to achieve a systemic exposure (AUC) of 8 mg/ml min.(36) We calculated the carboplatin dose (in mg/m2) from: AUC × [(0.93 × GFR) + 15]; the GFR (glomerular filtration rate: ml/min/m2) was estimated from 99mtechnetium DTPA (Tc99)-based serum clearance studies.

Figure 1.

Treatment scheme for the DAC regimen. Treatment was given over a 10-month period. If there was no response to DAC during induction therapy, the patient was taken off the study.*

Table 2.

Outline of the DAC Regimen

| Induction: 9 weeks | ||

| Block 1 (DAC) | ||

| Dexamethasone | Days 1-4 | 40 mg*, i.v. |

| Cytarabine | Day 2 | 2 g/m2 per dose, i.v., ×2, 12 h apart |

| Carboplatin | Day 1 | To achieve a systemic exposure† of 8 mg/mL.min; CI over 24 h |

| G-CSF | Day 4 onward | 10 μg/kg per day, subcutaneously, daily |

| Block 2 (DAC) | ||

| Same as Block 1 | ||

| Block 3 (CHOD) | ||

| Cyclophosphamide | Day 1 | 800 mg/m2, i.v. |

| Doxorubicin | Day 1 | 75 mg/m2, i.v. |

| Vincristine | Day 1 | 1.5 mg/m2, i.v. (max. 2 mg) |

| Dexamethasone | Days 1-14 | 12 mg/m2, i.v. or orally, in 3 divided doses, daily |

| Consolidation (VAML): 3 weeks | ||

| Vincristine | Day 1 | 1.5 mg/m2, i.v. |

| Doxorubicin | Day 1 | 30 mg/m2, i.v. |

| Mercaptopurine | Days 1-5 | 225 mg/m2, orally, in 3 divided doses, daily |

| L-Asparaginase | 3 times per week (e.g., every MWF) | 10,000 U/m2, intramuscularly, ×6 (i.e., for 2 weeks) |

| Continuation (×3): 27 weeks | ||

| Block 1 (DAC) | ||

| Dexamethasone | Days 1-4 | 40 mg*, i.v. |

| Cytarabine | Day 2 | 2 g/m2 per dose, i.v., ×2, 12 h apart |

| Carboplatin | Day 1 | To achieve a systemic exposure† of 8 mg/mL.min; CI over 24 h |

| Block 2 (VMMD) | ||

| Vincristine | Day 1 | 1.5 mg/m2, i.v. |

| Mercaptopurine | Days 1-5 | 225 mg/m2, orally, in 3 divided doses, daily |

| Methotrexate | Day 1 | 60 mg/m2, i.v. |

| Dexamethasone | Days 1-5 | 40 mg*, i.v. |

| Block 3 (CHOD) | ||

| Vincristine | Day 1 | 1.5 mg/m2, i.v. |

| Cyclophosphamide | Day 1 | 800 mg/m2, i.v. |

| Doxorubicin | Day 1 | 30 mg/m2 |

| Dexamethasone | Days 1-5 | 40 mg*, i.v. |

| Prophylaxis and Treatment for CNS Involvement | ||

| Bone marrow is positive or there are primary tumors in the head or neck | Give methotrexate, IT, on days 1, 8, 22, and 43 of induction and on day 1 of each continuation cycle | Dose by age: < 1 yr, 6 mg 1-2 yrs, 8 mg 3-8 yrs, 10 mg ≥ 9 yrs, 12 mg |

| CNS is positive at diagnosis | Give additional doses of methotrexate, IT, on induction days 15, 29, and 36 | |

i.v.: intravenously; CI: continuous intravenous infusion; G-CSF: granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; MWF: Monday, Wednesday, Friday; IT: intrathecally.

Give therapy only when the absolute neutrophil count (ANC) is ≥ 300 × 106/L (300/mm3) and the platelet count is > 100 × 109/L (100,000/mm3) before each block.

20 mg for children < 5 years old.

Area under the concentration vs time curve (AUC).

Overall survival time was measured from the date of diagnosis to the date of death or date of last contact. Event-free survival was measured from the date of diagnosis to the date of induction failure, relapse, death or last follow-up examination. Overall survival and event-free survival were estimated with Kaplan-Meier methods;(37) the associated standard errors were calculated by the method of Peto and Pike.(38)

Toxicity was graded according to the NCI’s toxicity criteria. Complete blood counts and blood chemistry values were checked before starting each course of chemotherapy, which was delayed if the absolute neutrophil count (ANC) was < 0.3 × 109/L or the platelet count was < 100 × 109/L . We assessed renal function by measuring serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen concentration and by estimating the GFR from Tc99 clearance measurements. Echocardiography and electrocardiography were performed before each cycle of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and dexamethasone (CHOD) to evaluate for anthracycline-induced cardiac toxicity. Audiograms were performed before each dose of carboplatin to evaluate ototoxicity. After completion of therapy, we performed a physical examination, blood chemistry analyses, complete blood counts and diagnostic imaging studies (as outlined above for initial staging), to evaluate remission status and treatment-related toxicity. These evaluations were made monthly for the first 6 months, every 2 months for the next 6 months, every 3 months in the second year after therapy, and annually thereafter. Echocardiograms, electrocardiograms, and audiograms were obtained annually to screen for chemotherapy-related organ dysfunction.

RESULTS

Twenty-one patients had stage III disease and 4 had stage IV disease. The clinical features, including sites of disease at the time of diagnosis, are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Clinical Features of 25 Children Given Treatment with the DAC Regimen

| No. | Disease Stage | Sites of Disease | Pathology | Response |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAC | DAC + CHOD | Relapse | Status | ||||

| 1 | III | Bones, soft tissue | DLBCL | CR* | -- | -- | A |

| 2 | III | Lymph nodes | DLBCL | CR | -- | -- | A |

| 3 | III | Mediastinum, lung | MLBCL | PR | PR | Mediastinum | A |

| 4 | IIIa | Intestine | DLBCL | CR | -- | -- | A |

| 5 | III | Mediastinum, lymph nodes | LC-T,NOS | PRb | PRc | -- | D |

| 6 | III | Mediastinum, bone, pancreas | LC-T,NOS | CR | -- | -- | A |

| 7 | III | Skin, lymph nodes, bone | ALCL | PRc | -- | -- | A |

| 8 | III | Mediastinum, bones, lymph nodes, soft tissue | ALCL | PR | CR* | Bones, lung | D |

| 9 | III | Mediastinum, abdominal mass, lymph nodes | ALCL | PR | CR* | -- | A |

| 10 | III | Paraspinal mass, bones | ALCL | PR | PRc | -- | D |

| 11 | III | Mediastinum, soft tissue, bone | ALCL | NRc | -- | -- | D |

| 12 | III | Lymph nodes, pleural mass | ALCL | NR(mixed)c | -- | -- | A |

| 13 | III | Lung, lymph nodes, skin, bones | ALCL | CR | -- | -- | A |

| 14 | IV | Lymph nodes, bone, spleen, bone marrow | ALCL | CR* | -- | -- | A |

| 15 | III | Lymph nodes, spleen | ALCL | CR* | -- | -- | A |

| 16 | III | Lymph nodes, spleen | ALCL | CR | -- | -- | A |

| 17 | III | Lymph nodes | ALCL | CR | -- | -- | A |

| 18 | III | Bones, mediastinum, skin, lymph nodes, kidney | ALCL | CR | -- | Skin, lymph node | D |

| 19 | III | Mediastinum, lymph nodes | LC-B, NOS | NRc | -- | -- | A |

| 20 | III | Mediastinum | MLBCL | PR | CR* | -- | A |

| 21 | IV | Bone, mediastinum, lymph nodes, bone marrow | LC-B, NOS | PR | CR* | Mediastinum, bone, bone marrow | D |

| 22 | III | Lymph node, bone, soft tissue | DLBCL | CR* | -- | -- | A |

| 23 | III | Mediastinum, lymph nodes, bones | LC, NOS | CR | -- | -- | A |

| 24 | IVa | Brain | LC, NOS | CR | -- | -- | A |

| 25 | IV | Mediastinum, pericardium, bone marrow | LC, NOS | PR | CR* | -- | A |

NR, no response; PR, partial response; CR, complete response (9 patients in whom diagnostic imaging revealed minimal abnormality of questionable significance at the primary site of disease were categorized provisionally as having a CR); A, alive; D, dead; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; MLBCL, mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma; ALCL, anaplastic large cell lymphoma; LC-T NOS, T-large cell not otherwise specified; LC-B NOS, B-large cell not otherwise specified (with atypical features); LC NOS, large cell not otherwise specified.

Incomplete resection (microscopic residual).

Emergency mediastinal irradiation at diagnosis.

Treatment failure (NR or PR with progressive disease); patient taken off study

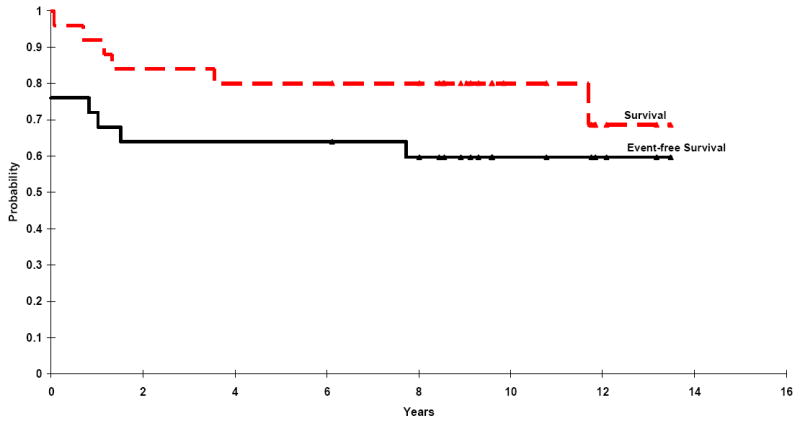

Twenty-two of the 25 patients (88%; 95% CI 68%- 97%) had a complete (n=13) or partial (n=9) response to the initial 2 sequential courses of DAC. With additional therapy (the CHOD regimen), some of the patients who had had partial responses to DAC had complete responses, resulting in a complete remission rate of 72% and partial remission of 12%. The 5-year event-free survival rate (± SE) was 64% ± 9% (median follow-up, 9.1 years; Figure 2). With retrieval therapy, including autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (6 patients), a 5-year overall survival rate of 80% ± 8% was achieved (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Event-free survival and overall survival for 25 children treated with the DAC regimen. The triangles denote patients still at risk for adverse events.

Grade 4 hematologic toxicity was observed in 73% of patients. Overall, episodes of fever with neutropenia occurred after 1 of every 3 blocks of DAC administered. There were 4 episodes of grade III mucositis and grade III transaminase elevation and 1 episode of grade III hyperbilirubinemia - none of these episodes followed treatment with DAC. There was no evidence of substantial renal toxicity as shown by stable serum creatinine concentration and Tc99 clearance rates. No patients had a significant decrease in the shortening fraction on the echocardiogram. Six patients had loss of high-frequency hearing, with decreased acuity above 2000 Hz (n=2), 6000 Hz (n=2), or 8000 Hz (n=2). None of these patients required hearing amplification.

DISCUSSION

Improving the treatment outcome for children with large-cell NHL, while reducing morbidity and the risk of late adverse effects, remains a challenge. Various approaches to address this problem have been investigated. For example, the former Pediatric Oncology Group piloted a regimen that incorporates intermediate-dose methotrexate and cytarabine into the APO regimen, which features doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone.(39) The addition of intermediate-dose methotrexate and cytarabine, however, failed to significantly improve outcome.(39) High-dose methotrexate and agents such as ifosfamide have been featured in successful European trials performed by the German (BFM), and French (SFOP) cooperative groups.(40-45) In an attempt to find new, active drug combinations that have fewer acute and late adverse effects, we piloted this study in which DAC was given during both induction, and continuation therapy. The CHOP component of the ACOP+ regimen is widely accepted as being active against large-cell lymphoma in adults, but reports of the activity of low-dose methotrexate, mercaptopurine, and L-asparaginase against large-cell NHL are lacking. Nonetheless, since these drugs were components of the successful ACOP+ regimen, we maintained their use in this regimen.

In this study, the DAC combination was very active, as shown by the 88% rate of complete or partial response after 2 cycles of treatment. However, after completion of the entire treatment regimen (induction, consolidation, and continuation), the 5-year event-free survival rate was 64% ± 10%, which is similar to those obtained with more conventional histology-directed CHOP-based regimens (see Table 1). Likewise, Fisher, et al.(46) made a similar observation that the incorporation of additional agents in the treatment of large-cell NHL in adults did not improve long-term outcome over that obtained with CHOP treatment alone. To obtain a more complete evaluation of the potential benefit of adding agents to the CHOP regimen for children with large-cell NHL, further studies are clearly needed.

Although the inclusion of DAC in our study did not appear to improve the event-free survival rate, it is important to note that with this regimen, we achieved similar results to those obtained previously, but with lower cumulative doses of anthracycline and cyclophosphamide. The most severe acute toxicity associated with this DAC-based regimen was myelosuppression with associated febrile neutropenia, which occurred after one-third of the DAC courses administered. For this reason, G-CSF (filgrastin) was given after the first two courses of DAC, during induction. Rarely, grade III mucositis and grade III transaminase elevation occurred, but not after the DAC cycles. Of note, the use of carboplatin did not produce significant renal toxicity, as determined by serum creatinine and Tc99 clearance studies. A few patients developed mild ototoxicity, which resulted primarily in hearing loss involving high-frequency tones; such loss would not affect conversational speech and hearing.

Sequelae of existing CHOP-based therapy that arouse the most concern include cardiac toxicity,(47-56) infertility,(57) and second malignancies. Cyclophosphamide and other alkylating agents result in a dose-related depletion of germinal cells which is generally more severe in males than in females. Recovery of spermatogenesis after cyclophosphamide-induced azoospermia is dose-related. Sterility is likely at cumulative doses ≥ 7.5 g/m2, while fertility is usually maintained at doses < 4 g/m2.(57) Our regimen prescribed a cumulative cyclophosphamide dose of 3.2 g/m2, which should permit the preservation of fertility in most patients. The Pediatric Oncology Group published the results of a study comparing APO with ACOP+ that demonstrated that cyclophosphamide could be eliminated if the regimen maintained a relatively anthracycline-rich backbone.(31)

The desire to avoid anthracycline-related cardiac toxicity is an important factor influencing protocol development in pediatric oncology patients. Whereas cumulative doses of doxorubicin of 550 mg/m2 are generally well tolerated in adults, cumulative doses of doxorubicin of 45 mg/m2 to 300 mg/m2 may cause abnormalities of ventricular after load and contractility in children.(48) Factors predictive of cardiac dysfunction include a high cumulative anthracycline dose and higher intensity of anthracycline dosage, female gender, young age, use of mediastinal irradiation, and long time interval since completion of therapy.(47, 49, 50, 53-56) All of our patients had normal cardiac function according to routine echocardiography and electrocardiography during and after completion of therapy. Our regimen prescribed a total cumulative dose of 195 mg/m2 of doxorubicin, which we anticipate will be associated with a low risk of late-onset cardiac toxicity. However, continued monitoring of cardiac function in these children is essential to evaluate delayed effects that may emerge with time.

Other groups have examined the need for anthracyclines as well as novel ways to preserve cardiac function when anthracyclines are used. The former Children’s Cancer Group’s randomized trial of COMP versus D-COMP (see Table 1) demonstrated that the addition of doxorubicin did not improve outcome compared to that achieved with COMP alone.(28) Nevertheless, as suggested by the Pediatric Oncology Group’s Study,(31) anthracyclines remain an important class of agents in large cell NHL treatment. While cardioprotectants, such as Zinecard (dexrazoxane), may reduce cardiotoxicity in patients who receive a high cumulative dose of anthracyclines, careful monitoring of such use is recommended because of the potentially increased risk of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms.(58)

Previous exposure to alkylating agents, anthracyclines, epipodophyllotoxins, and radiation has been associated with the development of second malignancies. For patients treated with the DAC regimen, we anticipate a low risk of treatment-related secondary carcinogenesis, because this regimen comprises relatively low cumulative doses of cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin, and does not incorporate any epipodophyllotoxins or involved-field radiation therapy. Additional follow-up of this cohort is required to establish this supposition.

Studies suggest that an immunophenotype-directed approach may be more effective in the management of large-cell NHL in children.(10, 12, 41, 42, 59) In a Pediatric Oncology Group study comparing the APO and ACOP+ regimens, children with B-cell tumors had a significantly better treatment outcome than did those with a non-B-cell immunophenotype; however, the sample size in that study was relatively small.(59) Among advanced-stage cases, the 3-year event-free survival rate was 96% ± 5% (SE) for B-cell cases, 67% ± 12% for patients with T-cell lymphomas, and 74% ± 13% for those with non-T, non-B-cell immunophenotypes. The French cooperative group (SFOP) reported an excellent result for the treatment of B-cell large-cell NHLs with their LMB89 regimen, which they use for all B-cell NHL, including Burkitt lymphoma.(10, 42) The LMB89 regimen includes courses of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone as well as courses of high-dose methotrexate (3 g/m2 per dose) and low-dose cytarabine in most cases. The German BFM cooperative group, which also uses an immunophenotype-directed approach, has reported excellent results for treatment of B-cell-large cell NHL.(12, 41) All six patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in our study (2 with mediastinal large B-cell), are currently alive and disease-free (one is in second remission after salvage therapy). Therefore, it appears that a novel or more intensive regimen may be necessary to treat the large-cell lymphomas of non-B-cell immunophenotype.

In summary, the DAC combination is active in previously untreated pediatric large cell lymphoma and the entire DAC+ regimen is effective and well tolerated. Although DAC+ did not produce a result superior to other CHOP-based regimens, the low cumulative dosages of cyclophosphamide and anthracycline should be associated with preservation of fertility and a low rate of clinically significant cardiac toxicity. Many of the patients who experienced treatment failure were successfully salvaged with autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, resulting in an excellent overall survival rate (80% ± 8% at 5 years).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Janet R. Davies for scientific editing, Annette Stone and Mary Green for data management, Gwen Anthony for nursing care coordination, and Peggy Vandiveer for typing the manuscript. We dedicate this report in memory of John H Rodman.

Supported in part by a Grant from the National Cancer Institute (CA 21765), by a Center of Excellence Grant from the State of Tennessee, and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC). C-H Pui is the American Cancer Society Professor.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute sponsored study of classifications of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas: summary and description of a working formulation for clinical usage. The Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Pathologic Classification Project. Cancer. 1982;49:2112–2135. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820515)49:10<2112::aid-cncr2820491024>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, Vardiman JW. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon: IARC Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patte C, Philip T, Rodary C, et al. High survival rate in advanced-stage B-cell lymphomas and leukemias without CNS involvement with a short intensive polychemotherapy: results from the French Pediatric Oncology Society of a randomized trial of 216 children. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:123–132. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwenn MR, Blattner SR, Lynch E, Weinstein HJ. HiC-COM: a 2-month intensive chemotherapy regimen for children with stage III and IV Burkitt’s lymphoma and B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:133–138. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy SB, Bowman WP, Abromowitch M, et al. Results of treatment of advanced-stage Burkitt’s lymphoma and B cell (SIg+) acute lymphoblastic leukemia with high-dose fractionated cyclophosphamide and coordinated high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine. J Clin Oncol. 1986;4:1732–1739. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1986.4.12.1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brecher ML, Schwenn MR, Coppes MJ, et al. Fractionated cylophosphamide and back to back high dose methotrexate and cytosine arabinoside improves outcome in patients with stage III high grade small non-cleaved cell lymphomas (SNCCL): a randomized trial of the Pediatric Oncology Group. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;29:526–533. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-911x(199712)29:6<526::aid-mpo2>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowman WP, Shuster JJ, Cook B, et al. Improved survival for children with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and stage IV small noncleaved-cell lymphoma: a pediatric oncology group study. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1252–1261. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.4.1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reiter A, Schrappe M, Ludwig WD, et al. Favorable outcome of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood: a report of three consecutive studies of the BFM group. Blood. 1992;80:2471–2478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magrath IT, Janus C, Edwards BK, et al. An effective therapy for both undifferentiated (including Burkitt’s) lymphomas and lymphoblastic lymphomas in children and young adults. Blood. 1984;63:1102–1111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patte C, Auperin A, Michon J, et al. The Societe Francaise d’Oncologie Pediatrique LMB89 protocol: highly effective multiagent chemotherapy tailored to the tumor burden and initial response in 561 unselected children with B-cell lymphomas and L3 leukemia. Blood. 2001;97:3370–3379. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.11.3370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cairo MS, Sposto R, Perkins SL, et al. Burkitt’s and Burkitt-like lymphoma in children and adolescents: a review of the Children’s Cancer Group experience. Br J Haematol. 2003;120:660–670. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reiter A, Schrappe M, Parwaresch R, et al. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas of childhood and adolescence: results of a treatment stratified for biologic subtypes and stage--a report of the Berlin-Frankfurt-Munster Group. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:359–372. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.2.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magrath I, Adde M, Shad A, et al. Adults and children with small non-cleaved-cell lymphoma have a similar excellent outcome when treated with the same chemotherapy regimen. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:925–934. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.3.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson JR, Jenkin RD, Wilson JF, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients treated with COMP or LSA2L2 therapy for childhood non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a report of CCG-551 from the Childrens Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:1024–1032. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.6.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dahl GV, Rivera G, Pui CH, et al. A novel treatment of childhood lymphoblastic non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: early and intermittent use of teniposide plus cytarabine. Blood. 1985;66:1110–1114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patte C, Kalifa C, Flamant F, et al. Results of the LMT81 protocol, a modified LSA2L2 protocol with high dose methotrexate, on 84 children with non-B-cell (lymphoblastic) lymphoma. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1992;20:105–113. doi: 10.1002/mpo.2950200204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wollner N, Burchenal JH, Lieberman PH, Exelby P, D’Angio G, Murphy ML. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in children. A comparative study of two modalities of therapy. Cancer. 1976;37:123–134. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197601)37:1<123::aid-cncr2820370119>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tubergen DG, Krailo MD, Meadows AT, et al. Comparison of treatment regimens for pediatric lymphoblastic non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a Childrens Cancer Group study. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1368–1376. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.6.1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sullivan MP, Boyett J, Pullen J, et al. Pediatric Oncology Group experience with modified LSA2-L2 therapy in 107 children with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (Burkitt’s lymphoma excluded) Cancer. 1985;55:323–336. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850115)55:2<323::aid-cncr2820550204>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hvizdala EV, Berard C, Callihan T, et al. Lymphoblastic lymphoma in children--a randomized trial comparing LSA2- L2 with the A-COP+ therapeutic regimen: a Pediatric Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 1988;6:26–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1988.6.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sandlund JT, Santana V, Abromowitch M, et al. Large cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma of childhood: clinical characteristics and outcome. Leukemia. 1994;8:30–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandlund JT, Pui CH, Santana VM, et al. Clinical features and treatment outcome for children with CD30+ large- cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:895–898. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.5.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandlund JT, Pui CH, Roberts WM, et al. Clinicopathologic features and treatment outcome of children with large-cell lymphoma and the t(2;5)(p23;q35) Blood. 1994;84:2467–2471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kadin ME. Ki-1/CD30+ (anaplastic) large-cell lymphoma: maturation of a clinicopathologic entity with prospects of effective therapy [editorial] J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:884–887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.5.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stansfeld AG, Diebold J, Noel H, et al. Updated Kiel classification for lymphomas. Lancet. 1988;1:292–293. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90367-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kadin ME. Ki-1-positive anaplastic large-cell lymphoma: a clinicopathologic entity? J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:533–536. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stein H, Mason DY, Gerdes J, et al. The expression of the Hodgkin’s disease associated antigen Ki-1 in reactive and neoplastic lymphoid tissue: evidence that Reed-Sternberg cells and histiocytic malignancies are derived from activated lymphoid cells. Blood. 1985;66:848–858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sposto R, Meadows AT, Chilcote RR, et al. Comparison of long-term outcome of children and adolescents with disseminated non-lymphoblastic non-Hodgkin lymphoma treated with COMP or daunomycin-COMP: A report from the Children’s Cancer Group. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2001;37:432–441. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weinstein HJ, Lack EE, Cassady JR. APO therapy for malignant lymphoma of large cell “histiocytic” type of childhood: analysis of treatment results for 29 patients. Blood. 1984;64:422–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hvizdala EV, Berard C, Callihan T, et al. Nonlymphoblastic lymphoma in children--histology and stage-related response to therapy: a Pediatric Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:1189–1195. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.7.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laver JH, Mahmoud H, Pick TE, et al. Results of a randomized phase III trial in children and adolescents with advanced stage diffuse large cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: A Pediatric Oncology Group study. Leukemia and Lymphoma. 2001;42:399–405. doi: 10.3109/10428190109064597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Santana VM, Abromowitch M, Sandlund JT, et al. MACOP-B treatment in children and adolescents with advanced diffuse large-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Leukemia. 1993;7:187–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reiter A, Schrappe M, Tiemann M, et al. Successful treatment strategy for Ki-1 anaplastic large-cell lymphoma of childhood: a prospective analysis of 62 patients enrolled in three consecutive Berlin-Frankfurt-Munster group studies. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:899–908. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.5.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sandlund JT, Downing JR, Crist WM. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in childhood. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1238–1248. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605093341906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murphy SB. Classification, staging and end results of treatment of childhood non- Hodgkin’s lymphomas: dissimilarities from lymphomas in adults. Semin Oncol. 1980;7:332–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murry DJ, Sandlund JT, Stricklin LM, Rodman JH. Pharmacokinetics and acute renal effects of continuously infused carboplatin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1993;54:374–380. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1993.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaplan EaM P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peto R, Pike MC, Armitage P, et al. Design and analysis of randomized clinical trials requiring prolonged observation of each patient. II. analysis and examples. Br J Cancer. 1977;35:1–39. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1977.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laver JH, Kraveka JM, Hutchison RE, et al. Advanced-stage large-cell lymphoma in children and adolescents: results of a randomized trial incorporating intermediate-dose methotrexate and high-dose cytarabine in the maintenance phase of the APO regimen: a Pediatric Oncology Group phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:541–547. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.11.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reiter A, Schrappe M, Tiemann M, et al. Improved treatment results in childhood B-cell neoplasms with tailored intensification of therapy: A report of the Berlin-Frankfurt-Munster Group Trial NHL-BFM 90. Blood. 1999;94:3294–3306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mann G, Y E, Schrappe M. Diffuse large B-cell lymphomas in childhood and adolescence: favorable outcome with a Burkitt’s lymphoma directed therapy in trial NHL-BFM-90 - a report of the BFM group. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;315 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patte C, M J, Behrendt H. B-cell large cell lymphoma in children, description and outcome when treated with the same regimen as Burkitt. Ann Oncol. 1996;92 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Michon J, P C. Mediastinal large B cell lymphoma. Results of the French Society of Pediatric Oncology (SFOP) LMB89 Protocol. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;315 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patte C, Auperin A, Gerrard M, et al. Results of the randomized international FAB/LMB96 trial for intermediate risk B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma in children and adolescents: it is possible to reduce treatment for the early responding patients. Blood. 2007;109:2773–2780. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-036673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Woessmann W, Seidemann K, Mann G, et al. The impact of the methotrexate administration schedule and dose in the treatment of children and adolescents with B-cell neoplasms: a report of the BFM Group Study NHL-BFM95. Blood. 2005;105:948–958. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fisher RI, Gaynor ER, Dahlberg S, et al. Comparison of a standard regimen (CHOP) with three intensive chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1002–1006. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304083281404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kremer LC, van Dalen EC, Offringa M, Voute PA. Frequency and risk factors of anthracycline-induced clinical heart failure in children: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:503–512. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lipshultz SE, Colan SD, Gelber RD, Perez-Atayde AR, Sallan SE, Sanders SP. Late cardiac effects of doxorubicin therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:808–815. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199103213241205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sorensen K, Levitt G, Bull C, Chessells J, Sullivan I. Anthracycline dose in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: issues of early survival versus late cardiotoxicity. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:61–68. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nysom K, Holm K, Lipsitz SR, et al. Relationship between cumulative anthracycline dose and late cardiotoxicity in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:545–550. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krischer JP, Epstein S, Cuthbertson DD, Goorin AM, Epstein ML, Lipshultz SE. Clinical cardiotoxicity following anthracycline treatment for childhood cancer: the Pediatric Oncology Group experience. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1544–1552. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.4.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lipshultz SE, Lipsitz SR, Mone SM, et al. Female sex and drug dose as risk factors for late cardiotoxic effects of doxorubicin therapy for childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1738–1743. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506293322602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hudson MM, Rai SN, Nunez C, et al. Noninvasive evaluation of late anthracycline cardiac toxicity in childhood cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3635–3643. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.7451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kremer LC, van der Pal HJ, Offringa M, van Dalen EC, Voute PA. Frequency and risk factors of subclinical cardiotoxicity after anthracycline therapy in children: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:819–829. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Dalen EC, van der Pal HJ, Kok WE, Caron HN, Kremer LC. Clinical heart failure in a cohort of children treated with anthracyclines: a long-term follow-up study. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:3191–3198. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lipshultz SE, Lipsitz SR, Sallan SE, et al. Chronic progressive cardiac dysfunction years after doxorubicin therapy for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2629–2636. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meistrich ML, Wilson G, Brown BW, da Cunha MF, Lipshultz LI. Impact of cyclophosphamide on long-term reduction in sperm count in men treated with combination chemotherapy for Ewing and soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer. 1992;70:2703–2712. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19921201)70:11<2703::aid-cncr2820701123>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tebbi CK, London WB, Friedman D, et al. Dexrazoxane-associated risk for acute myeloid leukemia/myelodysplastic syndrome and other secondary malignancies in pediatric Hodgkin’s disease. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:493–500. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.3879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hutchison RE, Berard CW, Shuster JJ, Link MP, Pick TE, Murphy SB. B-cell lineage confers a favorable outcome among children and adolescents with large-cell lymphoma: a Pediatric Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2023–2032. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.8.2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]