Abstract

Rationale

Omega3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (ω3-PUFAs) are powerful modulators of angiogenesis. However, little is known about the mechanisms governing ω3-PUFA-dependent attenuation of angiogenesis.

Objective

This study aims to identify a major mechanism by which ω3-PUFAs attenuate retinal neovascularization (NV).

Methods and Results

Administering ω3-PUFAs exclusively during the neovascular stage of the mouse model of oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR) induces a direct NV reduction of more than 40% without altering vaso-obliteration (VO) or the regrowth of normal vessels. Co-treatment with an inhibitor of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)γ almost completely abrogates this effect. Inhibition of PPARγ also reverses the ω3-PUFA-induced reduction of retinal TNFα, ICAM-1, VCAM-1, E-Selectin and Ang-2 but not VEGF.

Conclusions

These results identify a direct, PPARγ-mediated effect of ω3-PUFAs on retinal NV formation and retinal angiogenic activation that is independent of VEGF.

Keywords: omega3 PUFA, PPAR, retinopathy, neovascularization, OIR

INTRODUCTION

Proliferative retinopathy is a major cause of blindness that occurs in two stages. Loss of functional vasculature in the early phase leads to retinal hypoxia that in turn drives a compensatory but destructive growth of pathological neovessels in the later phase. We previously found that dietary ω3-PUFAs given before the onset of neovascularization in the OIR mouse model stimulate the regrowth of normal retinal vasculature1, thus limiting the hypoxic stimulus for subsequent proliferative retinopathy. It is, however, not known if ω3-PUFAs also have direct effects on retinal NV formation and what mechanisms might be involved in mediating this effect.

In this study, we expose mice to ω3-PUFAs exclusively during the peak proliferative stage (phase II) of retinopathy. With this approach ω3-PUFAs selectively target retinal NV formation, without affecting vaso-obliteration or regrowth of normal vessels. Our results demonstrate that ω3-PUFAs given after the onset of active retinopathy exert a beneficial effect on the retina’s inflammatory and angiogenic activation state that leads – mediated via the endogenous ω3-PUFA-receptor PPARγ – to attenuated retinal NV.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

For a detailed description see Supplementary Methods online.

O2-induced retinopathy, ω3-PUFA intervention and PPARγ inhibition

O2-induced retinopathy has been described in detail2–4. C57BL/6 mothers with pups were fed standard chow until P14 and then switched to a defined diet with 10% (w/w) safflower oil containing either 2% ω3-PUFAs (DHA and EPA) or 2% ω6-PUFAs (arachidonic acid)1. The lipid composition of the mother’s milk reflects the mother’s diet5 and changes in the mother’s diet are efficiently transferred to the pups1. GW9662, a specific PPARγ-antagonist with a nanomolar inhibitory concentration6 that effectively blocks PPARγ in vivo7 was injected i.p. daily into mouse pups from P14 – P17 (1 mg/kg in 20 µl). Vehicle control was PBS/DMSO 1:1.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

ω3-PUFA intervention directly attenuates retinal NV

In the OIR mouse model, vascular loss develops during hyperoxic incubation from P7–P12. After return to room air, the avascular areas of the retina become hypoxic and respond with upregulation of angiogenic growth factors like VEGF (Fig. 1a). VEGF-upregulation is followed by retinal neovessel formation seen morphologically from P15 onwards and displaying maximal severity at P17 (Fig. 1b). As dietary ω3-PUFAs are transferred from nursing mothers to the pups with some delay, ω3-PUFA treatment was started at P14 to specifically target the active phase of NV formation from P15 onwards (Fig. 1c). At P17, ω3-PUFA-fed mice show significantly less retinal NV compared to ω6-controls (5.2+/−0.5 vs. 9.1+/−0.5% NV; p=10−5) (Fig. 1d). VO at P17 is not affected (ω3 vs. ω6: 22.5+/−1.2 vs. 21.5+/−1.3% VO; p=0.6) (Fig. 1e). Enlarged retinal quadrants are shown in Online Fig. Ia,b. The ω6-diet with arachidonic acid or other ω6-PUFAs did not significantly exacerbate retinal NV compared to standard rodent chow, indicating that the observed differences in NV formation are mainly attributable to a beneficial effect of ω3-PUFAs (Online Fig. Ic,d).

Figure 1.

ω3-PUFA intervention reduces neovascularization. (a) Whole retinal VEGF expression in normoxic retinas and retinas with OIR normalized to Cyclophilin A. (b) Quantification of retinal NV from mice with OIR at P15 and P17 and representative retinal flatmounts with NV in white (n≥8 per group) (c) Schematic of the mouse OIR model and ω3-PUFA intervention. (d) P17 Quantification of retinal NV and representative lectin-stained flatmounts from mice given either ω3- or ω6-PUFAs from P14–P17. (e) Quantification and representative flatmounts of retinal VO from the same mice at P17. Scale bars=500µm. n≥23 per group. *****p≤10−5. White areas signify NV in (d) and VO in (e).

These results demonstrate, for the first time, that ω3-PUFAs can attenuate retinal NV formation directly, even when retinal hypoxia is already established and pathological neovascularization is in its active stage.

PPARγ activation is required for ω3-PUFA mediated attenuation of NV

The rapidity by which ω3-PUFA intervention attenuates NV suggests a receptor-based mechanism. We therefore investigated the involvement of the endogenous ω3-PUFA receptor PPARγ8. Pharmacological inhibition of PPARγ from P14–P17 with the specific inhibitor GW96626, 7 significantly reduces the inhibitory effects of ω3-PUFAs on retinal NV (4.7+/−0.4 vs. 7.2+/−0.4 %NV; p=0.0008) without altering retinal NV in ω6-groups (7.4+/−0.5 vs. 6.9+/−0.6 % NV; p=0.5) (Fig. 2a,c). VO at P17 was not altered in either group (21.8+/−1.5 vs. 22.1+/−1.5 %VO; p=0.9 and 20.5+/−2 vs. 20.8+/−1.5 %VO; p=0.9) (Fig. 2b). Original retinal images and enlarged quadrants are shown in Online Fig. II. Notably, pharmacological inhibition of PPARγ also reduces the expression of PPARγ in circulating leukocytes from ω3-fed mice to levels seen in the ω6-control group (Online Fig. III).

Figure 2.

PPARγ activation is required for ω3-mediated attenuation of neovascularization. (a) Quantification of retinal NV from mice with either ω3- or ω6-PUFA intervention and injection of either PPARγ-inhibitor GW9662 or vehicle from P14–P17. (b) Quantification of retinal VO from the same mice at P17. (c) Representative retinal flatmounts of P17 retinas for each experimental group (NV in white). Scale bars=500µm. n=10 per group. ****p≤0.001.

These results identify PPARγ as a major pathway through which ω3-PUFAs exert their beneficial effects on retinal neovascularization. The swiftness of the ω3-PUFA effects and the near-complete abrogation with PPARγ inhibition indicate a central role for this transcriptional regulator in conveying the ω3-PUFA effects. Importantly, pharmacological PPARγ activation with thiazolidinediones (TZDs), used to control hyperglycemia in type II diabetes, similarly attenuates proliferative retinopathy both in animal models and in diabetic patients9, 10, raising the possibility that ω3-PUFAs might have clinical effects similar to pharmacological PPARγ activators.

ω3-PUFA intervention reduces retinal inflammatory activity via PPARγ

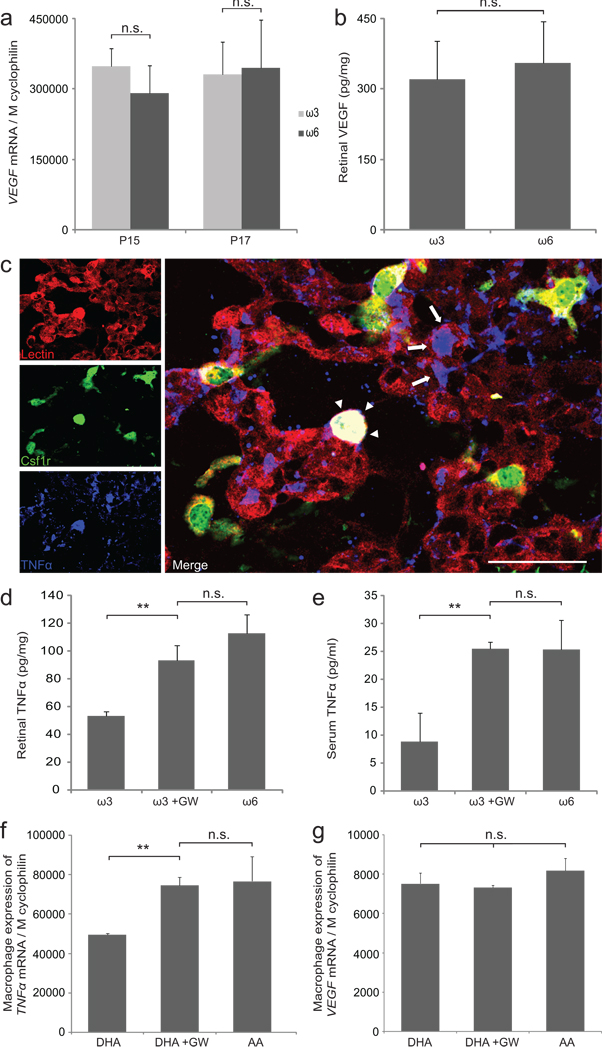

Given that retinal VEGF levels were not altered by ω3-PUFA intervention (Fig. 3a,b) and given the known involvement of PPARγ in inflammatory modulation11, we hypothesized that ω3-PUFAs might limit NV by modulating retinal inflammatory pathways. TNFα is a major inflammatory mediator whose expression is upregulated during the proliferative stage of OIR12. In P17 OIR retinas, TNFα localizes to retinal neovessels (arrows in Fig. 3c) as well as to macrophages associated with these neovessels (arrowheads in Fig. 3c). ω3-PUFA treatment reduces TNFα protein both in retina and serum in a PPARγ-dependent fashion (Fig. 3d,e). Similarly, murine macrophages incubated with ω3-PUFAs (docosahexaenoic acid; DHA) in vitro express significantly less TNFα than those incubated with ω6-PUFAs (arachidonic acid; AA); a difference that is also dependent on PPARγ (Fig. 3f). Analogous to the retina, macrophage expression of VEGF is not modulated by ω3- or ω6-treatment in vitro (Fig. 3g).

Figure 3.

ω3-PUFA intervention reduces TNFα but not VEGF via PPARγ. (a) Retinal VEGF expression at P15 and P17 in mice with ω3- or ω6-PUFA intervention. n=6 per group (b) Retinal VEGF protein levels at P17 in mice with ω3- or ω6-PUFA intervention. n≥3 per group (c) Retinal flatmount from mice expressing GFP under the macrophage-specific Csf1r promoter (green) stained for endothelial cells with lectin (red) and TNFα (blue) at OIR P17. Scale bar=50µm. (d,e) Retinal and serum TNFα protein in mice with ω3-PUFA intervention and injection of either PPARγ-inhibitor GW9662 or vehicle from P14–P17. Vehicle-injected mice on ω6-PUFA served as controls. (f,g) TNFα and VEGF expression in RAW 264.7 macrophages in vitro with either docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), DHA+GW9662, or arachidonic acid (AA). n=3 independent wells per group **p≤0.03

These results indicate that ω3-PUFAs attenuate NV formation without altering the hypoxia-driven VEGF axis but by modulating the retina’s inflammatory state via PPARγ. These findings are in line with data obtained with pharmacologic PPARγ-activators that reduce retinal TNFα and NV formation in the OIR model without changing VEGF overexpression9, 13 and reduce TNFα levels in diabetic patients14.

ω3-PUFA intervention reduces endothelial cell activation via PPARγ

Besides modulating inflammatory mediators, ω3-PUFAs can directly attenuate activation of endothelial cells (ECs)15. EC activation is in part characterized by upregulation of adhesion molecules16 and angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2)17 and renders ECs more responsive to angiogenic stimulation. Ang-2 in particular has been found to be expressed only weakly in resting endothelium but robustly following endothelial activation18. At P17, both Ang-2 and the adhesion molecule ICAM-1 are expressed in activated ECs from retinal neovessels but not in quiescent vessels nearby (Fig. 4a,b,). When neovessels are isolated using laser-capture microdissection (Fig. 4c), NV from ω3-animals show a PPARγ-dependent reduction of ICAM-1, VCAM-1, E-Selectin and Ang-2 compared to ω6-mice (Fig. 4d–g). In line with the mRNA data, ω3-PUFAs reduce retinal Ang-2 protein, mediated in part via PPARγ (Fig. 4h). Ang-1 and ICAM-2 are not significantly regulated between ω3- and ω6-groups (Online Fig. IVa,b). Importantly, other non-endothelial cells closely associated with neovessels may also contribute to the inflammatory profile presented. Particularly neovessel-associated macrophages (Fig. 3c) may influence the local inflammatory milieu. This is illustrated by higher levels of local TNFα expression in laser-captured neovessels from ω6-mice compared to ω3-mice (Online Fig. IVc).

Figure 4.

ω3-PUFA intervention reduces endothelial cell activation via PPARγ. (a,b) Retinal P17 flatmount stained with isolectin (red) and (a) ICAM-1 (green) or (b) Ang-2 (green). Scale bar=50µm. (c) Schematic of retinal neovessels isolated using laser-capture microdissection. (d–g) Gene expression of ICAM-1, VCAM-1, E-Selectin and Ang-2 in P17 laser-captured retinal neovessels from mice with ω3-PUFA intervention and injection of either PPARγ-inhibitor GW9662 or vehicle from P14–P17. Vehicle-injected mice on ω6-PUFA served as controls. All data normalized to Cyclophilin A. (h) Western blot and quantification for retinal Ang-2 protein on mice from the same groups as in d–g. **p≤0.03, ***p≤0.01, ****p≤0.001

In summary, this study demonstrates that ω3-PUFA intervention during the proliferative phase of retinopathy decreases the retina’s neovascular activity via PPARγ-dependent reduction of inflammatory mediators and attenuation of EC activation. The PPARγ-dependent effect of ω3-PUFAs on NV formation is large and comparable to anti-VEGF treatment in the OIR model4. This is the first study to identify a direct inhibitory effect of ω3-PUFAs on retinal neovascularization and the first to identify PPARγ as one of the major pathways mediating this effect. Since retinal VEGF levels are unaffected, ω3-PUFA-dependent activation of PPARγ might be considered as an additive treatment to the current anti-VEGF approaches for pathological retinal angiogenesis.

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE

“What is known?”

-

-

Omega3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (ω3-PUFAs) are angiogenic modulators that can attenuate the severity of retinal neovascularization (NV).

-

-

Whether ω3-PUFAs exert a direct effect on retinal neovessel formation and what mechanisms might be involved, remained unknown.

-

-

This study investigates whether the known endogenous ω3-PUFA receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ is involved in mediating a potential direct effect of ω3-PUFAs on retinal neovessel formation.

“What new information does this article contribute?”

-

-

By specifically targeting the neovascular phase of proliferative retinopathy (phase II), this study identifies, for the first time, a direct beneficial effect of ω3-PUFAs on retinal NV formation during the active proliferative phase.

-

-

This study identifies PPAR-g as a major pathway through which ω3-PUFAs exert their beneficial effects on NV formation.

-

-

Activation of PPAR-g - by ω3-PUFAs affected the inflammatory state of the retina and attenuated angiogenic activation of retinal endothelial cells.

Summary

We have shown previously that ω3-PUFAs given before the onset of retinopathy can attenuate disease severity. In many patients, however, retinopathy is diagnosed when the disease has already progressed to active neovascularization. Our study demonstrates that ω3-PUFAs given selectively during the neovascular phase of retinopathy directly reduce retinal neovessel formation without altering vaso-obliteration or regrowth of normal vessels. Mechanistically, we identify PPARγ as a major mediator for the ω3-PUFA effect that acts independent of VEGF through modulation of inflammatory mediators and reduced angiogenic activation of retinal endothelial cells. ω3-PUFAs might thus be considered as an additive treatment to anti-VEGF therapies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (AS). Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Charles A. King Trust Award (PS). William Randolph Hearst Award, March of Dimes Foundation, Simeon Burt Wolbach Research Fellowship (KMC). Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International, Knights Templar Eye Foundation, CHB Manton Center for Orphan Disease (JC). NIH (EY017017, EY017017-S1) V.Kann Rasmussen Foundation, RoFAR, CHB Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Center, RPB Senior Investigator Award, Alcon Research Institute Award, MacTel Foundation (LEHS).

NON-STANDARD ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- AA

arachidonic acid

- Ang-2

angiopoietin 2

- DHA

docosahexaenoic acid

- EC

endothelial cell

- EPA

eicosapentaenoic acid

- E-Selectin

endothelial selectin

- ICAM-1

intercellular adhesion molecule 1

- NV

neovascularization

- ω3-PUFAs

omega3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids

- OIR

oxygen-induced retinopathy

- P

postnatal day

- PPARγ

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ

- TZDs

thiazolidinediones

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor α

- VCAM-1

vascular cell adhesion molecule 1

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VO

vaso-obliteration

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DISCLOSURES

none

REFERENCES

- 1.Connor KM, SanGiovanni JP, Lofqvist C, Aderman CM, Chen J, Higuchi A, Hong S, Pravda EA, Majchrzak S, Carper D, Hellstrom A, Kang JX, Chew EY, Salem N, Jr, Serhan CN, Smith LE. Increased dietary intake of omega-3-polyunsaturated fatty acids reduces pathological retinal angiogenesis. Nat Med. 2007;13:868–873. doi: 10.1038/nm1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Connor KM, Krah NM, Dennison RJ, Aderman CM, Chen J, Guerin KI, Sapieha P, Stahl A, Willett KL, Smith LE. Quantification of oxygen-induced retinopathy in the mouse: a model of vessel loss, vessel regrowth and pathological angiogenesis. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1565–1573. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stahl A, Connor KM, Sapieha P, Willett KL, Krah NM, Dennison RJ, Chen J, Guerin KI, Smith LE. Computer-aided quantification of retinal neovascularization. Angiogenesis. 2009;12:297–301. doi: 10.1007/s10456-009-9155-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith LE, Wesolowski E, McLellan A, Kostyk SK, D'Amato R, Sullivan R, D'Amore PA. Oxygen-induced retinopathy in the mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:101–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serhan CN, Savill J. Resolution of inflammation: the beginning programs the end. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1191–1197. doi: 10.1038/ni1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leesnitzer LM, Parks DJ, Bledsoe RK, Cobb JE, Collins JL, Consler TG, Davis RG, Hull-Ryde EA, Lenhard JM, Patel L, Plunket KD, Shenk JL, Stimmel JB, Therapontos C, Willson TM, Blanchard SG. Functional consequences of cysteine modification in the ligand binding sites of peroxisome proliferator activated receptors by GW9662. Biochemistry. 2002;41:6640–6650. doi: 10.1021/bi0159581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu D, Zeng BX, Zhang SH, Yao SL. Rosiglitazone, an agonist of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, reduces pulmonary inflammatory response in a rat model of endotoxemia. Inflamm Res. 2005;54:464–470. doi: 10.1007/s00011-005-1379-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards IJ, O'Flaherty JT. Omega-3 Fatty Acids and PPARgamma in Cancer. PPAR Res. 2008;2008:358052. doi: 10.1155/2008/358052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murata T, Hata Y, Ishibashi T, Kim S, Hsueh WA, Law RE, Hinton DR. Response of experimental retinal neovascularization to thiazolidinediones. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:709–717. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.5.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shen LQ, Child A, Weber GM, Folkman J, Aiello LP. Rosiglitazone and delayed onset of proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:793–799. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.6.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kliewer SA, Sundseth SS, Jones SA, Brown PJ, Wisely GB, Koble CS, Devchand P, Wahli W, Willson TM, Lenhard JM, Lehmann JM. Fatty acids and eicosanoids regulate gene expression through direct interactions with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors alpha and gamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:4318–4323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Majka S, McGuire PG, Das A. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase expression by tumor necrosis factor in a murine model of retinal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:260–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higuchi A, Ohashi K, Shibata R, Sono-Romanelli S, Walsh K, Ouchi N. Thiazolidinediones reduce pathological neovascularization in ischemic retina via an adiponectin-dependent mechanism. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:46–53. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.198465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quinn CE, Hamilton PK, Lockhart CJ, McVeigh GE. Thiazolidinediones: effects on insulin resistance and the cardiovascular system. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:636–645. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Caterina R, Cybulsky MI, Clinton SK, Gimbrone MA, Jr, Libby P. The omega-3 fatty acid docosahexaenoate reduces cytokine-induced expression of proatherogenic and proinflammatory proteins in human endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14:1829–1836. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.11.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Caterina R, Cybulsky MA, Clinton SK, Gimbrone MA, Jr, Libby P. Omega-3 fatty acids and endothelial leukocyte adhesion molecules. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1995;52:191–195. doi: 10.1016/0952-3278(95)90021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stratmann A, Risau W, Plate KH. Cell type-specific expression of angiopoietin-1 and angiopoietin-2 suggests a role in glioblastoma angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:1459–1466. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65733-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fiedler U, Augustin HG. Angiopoietins: a link between angiogenesis and inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:552–558. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.