Abstract

Background

In comparison to the comprehensive analyses performed on virulence gene expression, regulation and action, the intracellular metabolism of Salmonella during infection is a relatively under-studied area. We investigated the role of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle in the intracellular replication of Salmonella Typhimurium in resting and activated macrophages, epithelial cells, and during infection of mice.

Methodology/Principal Findings

We constructed deletion mutations of 5 TCA cycle genes in S. Typhimurium including gltA, mdh, sdhCDAB, sucAB, and sucCD. We found that the mutants exhibited increased net intracellular replication in resting and activated murine macrophages compared to the wild-type. In contrast, an epithelial cell infection model showed that the S. Typhimurium ΔsucCD and ΔgltA strains had reduced net intracellular replication compared to the wild-type. The glyoxylate shunt was not responsible for the net increased replication of the TCA cycle mutants within resting macrophages. We also confirmed that, in a murine infection model, the S. Typhimurium ΔsucAB and ΔsucCD strains are attenuated for virulence.

Conclusions/Significance

Our results suggest that disruption of the TCA cycle increases the ability of S. Typhimurium to survive within resting and activated murine macrophages. In contrast, epithelial cells are non-phagocytic cells and unlike macrophages cannot mount an oxidative and nitrosative defence response against pathogens; our results show that in HeLa cells the S. Typhimurium TCA cycle mutant strains show reduced or no change in intracellular levels compared to the wild-type [1]. The attenuation of the S. Typhimurium ΔsucAB and ΔsucCD mutants in mice, compared to their increased net intracellular replication in resting and activated macrophages suggest that Salmonella may encounter environments within the host where a complete TCA cycle is advantageous.

Introduction

Salmonella enterica is one of the most common food-borne bacterial pathogens and the disease outcomes range from a self-limited gastroenteritis to typhoid fever in mammals. Typhoidal Salmonella serovars, such as Salmonella enterica serovars Typhi and Paratyphi, cause an estimated 20 million cases of typhoid and 200,000 human deaths wordwide per annum [2]. Typhoid infection involves transmission of Salmonella via the ingestion of contaminated food and water followed by bacterial penetration of the small intestinal barrier by invading gut epithelial cells causing bloody diarrhoea. Subsequently, Salmonella can enter the mesenteric lymph nodes and invade phagocytic cells such as macrophages [3], [4]. Within macrophages, the Salmonella bacteria are compartmentalised into a modified intracellular phagosome termed the “Salmonella containing vacuole” (SCV). The SCV protects the Salmonella by preventing lysosomal fusion [5], [6]. The antimicrobial defences deployed by macrophages include reactive oxygen and reactive nitrosative intermediates (ROI and RNI respectively), as well as antimicrobial peptides [7], [8]. The ROI response is bactericidal and occurs approximately 1 h post-infection of macrophages whereas the RNI response is bacteriostatic and occurs approximately 8 h post-infection [9], [10], [11].

Recently, research is being directed towards establishing the role of central metabolic pathways in the virulence of pathogenic bacteria [12]. For example, it has been shown that fitness of Escherichia coli during urinary tract infection is reliant upon gluconeogenesis and the TCA cycle [13]. In Salmonella, we and others have demonstrated that glycolysis and glucose are required for the intracellular replication of S. Typhimurium in macrophages and mice [14], [15], [16]. Other work has shown that full virulence of S. Typhimurium strain SR11 in a murine infection model requires a complete TCA cycle [17].

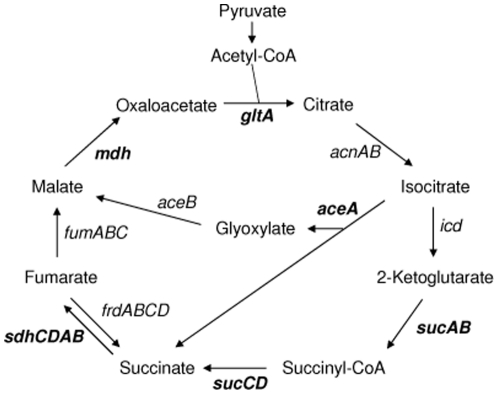

In the current study, we investigated the effect of disrupting the TCA cycle on the ability of S. Typhimurium to replicate within murine RAW macrophages and HeLa epithelial cells by deleting genes encoding specific TCA cycle enzymes. The HeLa epithelial cell line is a well-defined model for infection of mammalian cells with S. Typhimurium, and has been used to characterize the biogenesis and evolution of the SCV [18], [19], [20]. We deleted the sucAB, sucCD, sdhCDAB, mdh and gltA genes which encode 2-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, succinyl-CoA synthetase, succinate dehydrogenase, malate dehdrogenase and citrate synthase respectively (Figure 1) [21]. Interestingly, we found that disruption of the TCA cycle can result in an increase in the levels of the S. Typhimurium mutant strains within resting and activated macrophages compared to the wild-type. Mutants that showed increased net replication in macrophages did not exhibit the same phenotype in epithelial cells and, in agreement with previously published results, were severely attenuated in mouse infection assays compared to the wild-type [17].

Figure 1. TCA cycle and glyoxylate shunt showing intermediate products and genes encoding enzymes within the pathway.

Deleted genes are shown in bold.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains, growth conditions and reagents

S. Typhimurium strains and plasmids used in this work are listed in Table S1. All mutants were constructed in the wild-type strain 4/74 which is the prototrophic parent of the well-characterized SL1344 strain [22]. Strains were maintained in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or on plates with appropriate antibiotics at the following concentrations; ampicillin (Ap, Sigma Aldrich), 50 µg.ml−1, chloramphenicol (Cm, Sigma Aldrich), 12.5 µg.ml−1 and kanamycin (Kn, Sigma Aldrich), 50 µg.ml−1. Oligonucleotide primers were purchased from Sigma Genosys or Illumina, (California).

Mutant construction

S. Typhimurium mutant strains were constructed according to published procedures (Datsenko and Wanner 2000) and as briefly described in [14]. Primers used to construct the S. Typhimurium deletion mutant strains were purchased from Sigma-Genosys (Table 1). P22-derived transductants were screened on green agar plates to obtain lysogen-free colonies and all deletion mutants were transduced into a clean wild-type background [24]. The complete absence of the structural genes was verified by DNA sequencing of the deleted regions of the chromosome.

Table 1. Primers used to construct S. Typhimurium gene deletion mutants.

| Primer Name | Primer DNA sequence |

| aceAredf | CTGGCTTAATTCACCACATAACAATATGGAGCATCTGCACGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| aceAredr | TATCTGTAGGCCCGGTAAGCGCAGCGCCACCGGGCATCAACATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG |

| gltAredf | TCCGGCAGTCTTAAGCAATAAGGCGCTAAGGAGACCGTAAGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| gltAredr | GTACCGGATGGCGAGGGTTGCGTCGCCATCCGGTTGTCAACATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG |

| icdAredf | TGACAGACGAGCAAACCAGAAGCGCTCGAAGGAGAGGTGAGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| icdAredr | GACGTTAAGTCCCCGTTTTTGTTTTTAACAATTATCGTTACATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG |

| mdhredf | GCAATAGACACTTAGCTAATCATATAATAAGGAGTTTAGGGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| mdhredr | AGAAGCCGGAGCAAAAGCCCCGGCATCGGGCAGGAACAGCCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG |

| sucAredf | AGAGTATTAAATAAGCAGAAAAGATGCTTAAGGGATCACGGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| sucBredr | CCTTATCCGGCCTACAGGTAGCAGGTGATGCTCTTGCTGACATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG |

| sucCredf | GGTCTAAAGATAACGATTACCTGAAGGATGGACAGAACACGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| sucDredr | GAAAACGGACATTTATCTGTTCCCGCAGGAACAGCGAGTTCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG |

| sdhCredf | GTCTTAAGGGAATAATAAGAACAGCATGTGGGCGTTATTCGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| sdhBredr | ATAAGACTGTACGTCGCCATCCGGCAACCACTACAACTACCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG |

Plasmid construction

The sucCD genes were PCR amplified from S. Typhimurium 4/74 genomic DNA using primers sucF (5′ - TTTTAAGCTTATGAACTTACATGAATATCA) and sucR (5′ - TTTTGGATCCTCCCGCAGGAACAGCGAGTT). The PCR product was digested with BamHI and HindIII, ligated into the low-copy-number vector pWKS30 [25], and transformed into E. coli strain DH5α by electroporation [26]. The resulting plasmid was designated pWKS30::sucCD and was confirmed by PCR using primers sucF and sucR. Plasmids pWKS30 and pWKS30::sucCD were then transformed into 4/74 and AT3449 by electroporation.

Macrophage infection assays

Infection assays in murine RAW 264.7 macrophages (obtained from American Type Culture Collection; Rockville, MD; ATCC# TIB-71) were performed essentially as previously described [27]. Where indicated, macrophages were activated 24 h prior to infection by seeding the macrophages in MEM culture medium supplemented with 20 units.ml−1 (2 ng.ml−1) of IFN-γ (Sigma) as previously described [28]. The multiplicity of infection (MOI) for all experiments was 10∶1. The infection assays were allowed to proceed for 2 h and 18 h post infection. To estimate the amount of intracellular bacteria at each time point, cells were lysed using 1% Triton X-100 (Sigma), and samples were taken for viable counts [10]. Statistical significance was assessed by using Student's unpaired t test, and a P value of 0.05 was considered significant.

Cytotoxicity assays

Macrophages were infected as described above with the following modifications: DMEM without Phenol Red was used to prevent interference with the assay and the FBS content of the complete tissue culture medium was reduced to 5% due to associated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity. LDH activity released from the mammalian cells was measured in the tissue culture medium using the Cytotox 96 non-radioactive cytotoxicity assay kit (Cat. G1780, Promega) and was considered to reflect cytotoxicity of S. Typhimurium. Statistical significance was assessed by using Student's unpaired t test, and a P value of 0.05 was considered significant.

HeLa cell infection assays

Infection assays in human HeLa epithelial cells (obtained from American Type Culture Collection; Rockville, MD; ATCC# CCL-2) were performed according to [1]. Approximately, 1×105 HeLa cells were seeded into each well of a 6-well cell culture plates and infected with S. Typhimurium 4/74 and mutant strains at an MOI of 10∶1. Prior to infection the S. Typhimurium strains had been grown aerobically to an OD600 of ∼2.0 in LB broth at 250 rpm at 37°C to allow expression of the SPI-1 Type 3 secretion system.

To increase the uptake of Salmonella, the 6-well plates were centrifuged at 1000 g for 5 min, and this was defined as time 0 h. After 1 h of infection, extracellular bacteria were killed with 30 µg.ml−1 gentamicin. The media was replaced after 1 h with medium containing 5 µg.ml−1 gentamicin. Incubations were continued for 2 h and 6 h post-infection. To determine the levels of intracellular bacteria at each time point, cells were lysed using 0.1% SDS, and samples were taken for viable counts [10]. Statistical significance was assessed by using Student's unpaired t test, and a P value of 0.05 was considered significant.

Mouse infection assays

Mouse infection experiments were performed as described [29] with some modifications. Liquid S. Typhimurium cultures were grown statically in 50 ml of LB at 37°C overnight in 50 ml Falcon tubes (Corning) [30]. The following day bacteria were resuspended at a final cell density of 1×104 colony forming units (cfu) ml−1 in sterile PBS. Female BALB/c mice (Charles River U.K. Ltd.) were infected with 200 µl of bacterial suspension via the intraperitoneal (i.p.) cavity at a final dose of 2×103 cfu [29]. The infection was permitted to proceed for 72 h at which time point the mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation and the spleens and livers surgically removed [29]. Following homogenization of the organs in a stomacher (Seward Tekmar), serial dilutions of the suspensions in PBS were spread onto LB agar plates and bacterial cfu were enumerated after overnight incubation at 37°C [30]. All animal experiments were approved by the local ethics committee and conducted according to guidelines of the Animal Act 1986 (Scientific Procedures) of the United Kingdom.

Results and Discussion

Effect of disrupting the TCA cycle on intracellular replication of S. Typhimurium in resting macrophages

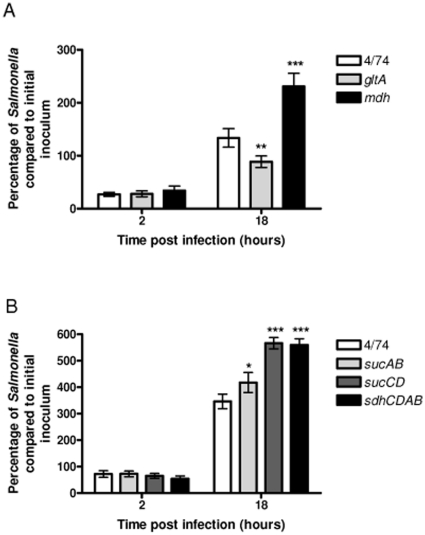

An incomplete TCA cycle has been found in a surprisingly large number of bacterial pathogens including Helicobacter pylori, Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus mutans [31], [32], [33]. The primary role of the TCA cycle is to provide NADH which is used by bacterial cells for ATP synthesis via the electron transport chain (ETC). However, the TCA cycle also plays a key role in the synthesis of intermediates for anabolic pathways; specifically 2-ketoglutarate, oxaloacetate and succinyl-CoA are starting points for the synthesis of glutamate, aspartate and porphyrin respectively (Figure 1). Bacteria that harbor an incomplete TCA cycle retain the ability to generate 2-ketoglutarate, oxaloacetate and succinyl-CoA from pyruvate. To determine the role of the complete TCA cycle for the intracellular replication of S. Typhimurium within macrophages we used a genetic approach to interrupt the TCA cycle. We tested S. Typhimurium strains carrying deletions of the gltA, mdh, sdhCDAB, sucAB and sucCD genes for their ability to replicate within resting macrophages compared to the wild-type (Figure 2AB). Surprisingly, we recovered up to 40% higher levels of the S. Typhimurium Δmdh, ΔsdhCDAB, and ΔsucCD strains from infected resting macrophages than the wild-type; the level of the S. Typhimurium ΔsucAB strain was 17% higher than the wild-type (Figure 2B). The apparent ‘over-replication’ phenotypes of the S. Typhimurium Δmdh, ΔsucAB, ΔsucCD, and ΔsdhCDAB strains relative to the wild-type suggested that a complete TCA cycle is not necessary for growth within resting macrophages. The observed reduced intracellular replication of the S. Typhimurium ΔgltA strain compared to the wild-type may suggest that 2-ketoglutarate and therefore glutamate is limiting within the SCV (Figure 2A). This result supports a previous finding that simultaneous prevention of glutamine synthesis and high-affinity transport attenuates S. Typhimurium virulence in BALB/c mice and murine macrophages, suggesting a host environment with low levels of glutamine [34].

Figure 2. Increased intracellular replication of the S. Typhimurium Δmdh, ΔsucAB, ΔsucCD and ΔsdhCDAB strains during infection of resting RAW macrophages.

(A) Intracellular replication assays of S. Typhimurium 4/74, ΔgltA (AT3505) and Δmdh (AT3508) strains during infection of resting RAW macrophages. (B) Intracellular replication assays of S. Typhimurium 4/74, ΔsucAB (AT3448), ΔsucCD (AT3449), and ΔsdhCDAB (AT3475) strains during infection of resting RAW macrophages. The data show the number of viable bacteria (expressed as percentages of the initial inocula) within macrophages at 2 h and 18 h post-infection. Each bar represent the statistical mean from three independent biological replicates and the error bars represent the standard deviation (The significant differences between the parental 4/74 strain and the mutant and complemented strains are shown by asterisks p>0.05, * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, and *** p<0.001.).

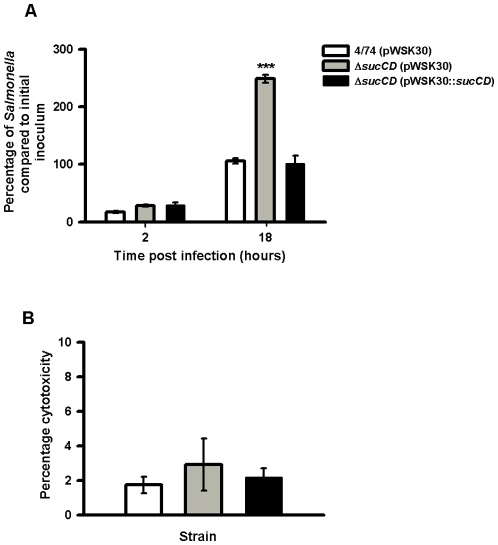

We confirmed that the apparent ‘over-replication’ phenotype of the S. Typhimurium ΔsucCD strain was due to deletion of the sucCD gene. We inserted the sucCD gene into the low-copy number vector pWKS30 [25], transformed the construct into the S. Typhimurium 4/74 and S. Typhimurium strains, and performed infection assays with macrophages. As shown in Figure 3A, the cloned copy of the sucCD gene fully complemented the sucCD deletion in during infection of macrophages and restored intracellular replication of the S. Typhimurium ΔsucCD strain containing pWKS30::sucCD to wild-type levels. Figure 3B shows that the level of cytotoxicity of the S. Typhimurium ΔsucCD strain and the complemented strain are indistinguishable from that of the wild-type strain demonstrating that the intracellular replication phenotype of the ΔsucCD strain is not a result of increased cell death.

Figure 3. Complementation of the S. Typhimurium ΔsucAB strain in resting RAW macrophages and cytotoxicity assays.

(A) Numbers of viable bacteria (expressed as percentages of the initial inoculum) inside the macrophages at 2 h and 18 h after infection. Each bar indicates the statistical mean for three biological replicates, and the error bars indicate the standard deviations. The significant differences between the parental 4/74 strain and the mutant and complemented strains are shown by asterisks p>0.05, * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, and *** p<0.001. (B) Cytotoxicity assays of S. Typhimurium wild-type, ΔsucCD (AT3449) and complemented ΔsucCD (AT???) strains in RAW macrophages after 18 h infection as a percentage of total LDH release from lysed uninfected macrophages. All cytotoxicity data were obtained from three independent biological replicates.

Increased net replication of the S. Typhimurium ΔsucCD mutant in resting macrophages is not due to increased flux through the glyoxylate shunt

The observed increased net replication of the S. Typhimurium Δmdh, ΔsdhCDAB, ΔsucAB and ΔsucCD strains could potentially be due to an increased flux through the glyoxylate shunt that conferred a replicative advantage compared to the wild-type within resting macrophages (Figure 2AB). The glyoxylate shunt bypasses reactions of the TCA cycle in which CO2 is released, and conserves 4 carbon compounds for biosynthesis (Figure 1) [21]. The pathway is active during growth on 2 carbon compounds such as acetate from fatty acids, when 4-carbon TCA cycle intermediates need to be conserved [21]. The conversion of isocitrate to glyoxylate is catalysed by isocitrate lyase, which has been shown to be required for the persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in infected macrophages [21], [35]. Isocitrate lyase is encoded by the aceA gene of S. Typhimurium [36]. To test whether the glyoxylate shunt plays a role in the increased intracellular replication phenotype of the S. Typhimurium ΔsucCD strain, we constructed S. Typhimurium ΔaceA and ΔsucCD mutants and tested them for their ability to replicate within resting macrophages. Figure 4A shows that the net intracellular replication of the S. Typhimurium ΔaceA strain is only slightly increased compared to the wild-type within resting macrophages. Furthermore, combining the ΔaceA and ΔsucCD mutations does not reduce the increased intracellular replication of the S. Typhimurium ΔsucCDΔaceA strain to wild-type levels. The data suggest that the glyoxylate shunt does not contribute to the increased net intracellular replication phenotype of the S. Typhimurium ΔsucCD strain in infected resting macrophages.

Figure 4. Increased intracellular replication of the S. Typhimurium ΔsucCD, ΔsdhCDAB, ΔgltA and Δmdh strains during infection of activated RAW macrophages.

(A) Intracellular replication assays of S. Typhimurium 4/74, ΔsucCD (AT3449), ΔaceA (AT3385) and ΔaceAΔsucCD (AT3496) strains during infection of resting RAW macrophages (B) Intracellular replication assay of S. Typhimurium 4/74, ΔsucAB (AT3448), ΔsucCD, (AT3449), ΔsdhCDAB (AT3475), ΔgltA (AT3505) and Δmdh (AT3508) strains during infection of activated RAW macrophages The data show the number of viable bacteria (expressed as percentages of the initial inocula) within activated macrophages at 2 h and 18 h post-infection. Each bar represent the statistical mean from three independent biological replicates and the error bars represent the standard deviation (The significant differences between the parental 4/74 strain and the mutant strains are shown by asterisks p>0.05, * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, and *** p<0.001).

Effect of disrupting the TCA cycle on intracellular replication of S. Typhimurium in activated macrophages

In the light of the above results, one possibility is that the net increase in intracellular replication of the S. Typhimurium Δmdh, ΔsucAB, ΔsucCD, and ΔsdhCDAB strains may be due to their enhanced ability to survive the antimicrobial defense mechanisms of macrophages, which include the ROI and RNI response [37], [38]. Production of ROI and RNI species are stimulated during activation of macrophages by lipopolysaccharide and IFN-γ [39]. We therefore tested the ability of S. Typhimurium ΔsucAB, ΔsdhCDAB, Δmdh, ΔsucCD and ΔgltA mutants to replicate within activated macrophages compared to the wild-type (Figure 4B). In this experiment, the wild-type 4/74 strain showed no net replication within activated macrophages; however the ΔsdhCDAB, Δmdh, ΔsucCD and ΔgltA strains all showed increased net replication (Figure 4B). The observation that the S. Typhimurium ΔsucAB shows no net replication within activated macrophages may reflect limited availability of succinyl-CoA within the SCV of activated macrophages. Succinyl-CoA is required for the biosynthesis of lysine, methionine and diaminopimelate. Diaminopimelate is essential for the synthesis of peptidoglycan and hence the bacterial cell wall [40], [41]. S. Typhimurium SR11 ΔsucAB strains have been shown to be avirulent in BALB/c mice [17].

The increased levels of the S. Typhimurium ΔgltA strain within activated macrophages, compared to decreased intracellular replication in resting macrophages may reflect increased survival rather than growth of the S. Typhimurium ΔgltA strain within activated macrophages. The proposed ability of the S. Typhimurium ΔsdhCDAB, Δmdh, ΔsucCD and ΔgltA mutants to better survive the antimicrobial ROI and RNI response in macrophages compared to the wild-type strain prompted us to test an alternate cell line (HeLa epithelial cells) in which S. Typhimurium is still within a vacuole, but not subject to the ROI and RNI responses [1].

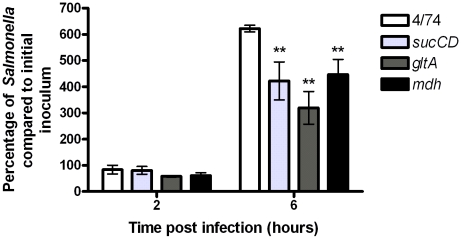

Effect of disrupting the TCA cycle on intracellular replication of S. Typhimurium in epithelial cells

Figure 5 shows that the S. Typhimurium ΔsucCD and ΔgltA strains show 30% less intracellular replication than the wild-type strain between 2 h and 6 h post infection. The S. Typhimurium Δmdh strain showed the same level as the wild-type.

Figure 5. Decreased intracellular replication of S. Typhimurium ΔsucCD and ΔgltA strains during infection of HeLa epithelial cells.

Intracellular replication assays of S. Typhimurium 4/74, ΔsucCD (AT3449), ΔgltA (AT3505) and Δmdh (AT3508) strains during infection of HeLa cells. The data show the number of viable bacteria (expressed as percentages of the initial inocula) within macrophages at 2 h and 6 h post-infection. Since S. Typhimurium initiates intracellular replication much earlier in HeLa cells (3–4 h) compared to macrophages (∼8 h post-infection) replication was assessed at 6 h post-infection (Hautefort et al., 2008). Each bar represent the statistical mean from three independent biological replicates and the error bars represent the standard deviation (The significant differences between the parental 4/74 strain and the mutant strains are shown by asterisks p>0.05, * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, and *** p<0.001).

These observations suggest that, in contrast to resting and activated macrophages, an intact TCA cycle is required for optimal intracellular replication within epithelial cells. Since HeLa cells lack the antimicrobial ROI and RNI responses deployed by macrophages, the reduced intracellular replication of the S. Typhimurium ΔsucCD and ΔgltA strains in epithelial cells supports the possibility that a disrupted TCA cycle favors the ability of S. Typhimurium to survive macrophage defense mechanisms [1]. Disruption of the TCA cycle may result in decreased flux through the ETC which could enhance the ability of the ΔsdhCDAB, Δmdh, ΔsucCD and ΔgltA mutants to survive the antimicrobial response mounted by activated macrophages by reducing Fenton reaction-based oxidative damage [38]; this hypothesis is the subject of further investigation, although we cannot rule out the possibility that other differences between the mutant and wild-type strains contribute to their infection phenotypes at this stage. For example, disruption of the TCA cycle may alter the redox balance in Salmonella to reduce endogenous NADH levels and therefore ETC activity. This would reduce endogenous Fenton-based oxidative damage and may enhance intracellular survival. Interestingly it has been postulated that bactericidal antibiotics may act by stimulating the TCA cycle which would increase NADH flux through the ETC thus increasing hydroxyl radical formation via the Fenton reaction and causing cell death [42], [43].

Effect of disrupting the TCA cycle on infection of mice by S. Typhimurium

The increased net replication of the S. Typhimurium ΔsdhCDAB, Δmdh, ΔsucCD and ΔgltA strains in macrophages was surprising in the light of previous findings which showed that S. Typhimurium ΔsucAB, ΔsdhCDAB and ΔsucCD mutants were attenuated in orally infected mice [17]. We therefore tested our S. Typhimurium ΔsucAB and ΔsucCD strains for their ability to infect mice.

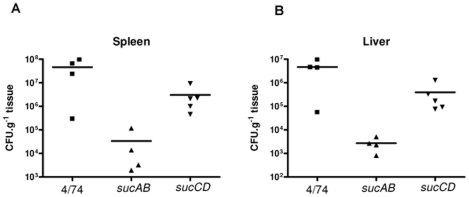

Following infection of mice, S. Typhimurium disseminates systemically from the Peyer's patches to the liver and spleen where it continues to grow within macrophages [44], [45], [46]. We inoculated mice with the S. Typhimurium ΔsucAB, ΔsucCD and wild-type strains via the intraperitoneal route. Salmonella bacteria were recovered and enumerated after 72 h of infection. The results demonstrate that the S. Typhimurium ΔsucAB mutant is severely attenuated (by ∼103 –fold) compared to the wild-type in the spleens and livers of infected mice (Figure 6A). The S. Typhimurium ΔsucCD strain is less attenuated than the S. Typhimurium ΔsucAB strain in livers and spleens of infected mice, but is still reduced by ∼10 –fold compared to the wild-type (Figure 6B). These results are consistent with the finding of Tchawa Yimga et al., [17], who found that S. Typhimurium SR11 ΔsucAB was avirulent and the ΔsucCD mutant was attenuated in orally infected BALB/c mice. The contrast between the attenuation of the S. Typhimurium ΔsucAB and ΔsucCD mutants in mice, and their increased intracellular replication in resting and activated macrophages suggest that Salmonella may encounter environments within the host where a complete TCA cycle is advantageous.

Figure 6. Succinyl-CoA synthetase and α-ketoglutarate synthetase are required for successful infection of mice.

Colony forming units per gram of tissue recovered from the spleens and livers of BALB/c mice following i.p. infection for 72 h with S. Typhimurium 4/74, ΔsucAB (AT3448) and ΔsucCD (AT3449).

Summary

We investigated the ability of S. Typhimurium TCA cycle mutants to replicate within macrophages, HeLa epithelial cells, and to infect BALB/c mice. The S. Typhimurium Δmdh, ΔsucCD, ΔsdhCDAB strains replicated to higher levels than the wild-type within resting and activated macrophages, suggesting an enhanced ability to survive antimicrobial mechanisms. This is supported by the observed decreased levels of the S. Typhimurium ΔsucCD and ΔgltA strains within infected epithelial cells, which lack an ROI and RNI response, although we cannot rule out other mechanisms at this stage. The increased level of the S. Typhimurium ΔsucCD in resting macrophages was not due to increased flux through the glyoxylate shunt. In agreement with previous work, we found that the S. Typhimurium ΔsucAB and ΔsucCD strains are attenuated in mice, suggesting an intact TCA cycle is required for successful infection within specific host environments.

Supporting Information

Strains and plasmids used in this study.

(0.03 MB PDF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Gary Rowley of the University of East Anglia for helpful discussions. We thank Dr. Isabelle Hautefort and Dr. Neil Shearer for a critical reading of the manuscript and comments. We also thank Dr. Isabelle Hautefort for help with the mouse infection work.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: The authors are grateful to the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) for funding this work (Grant BB/D004810/1 to AT, and the Core Strategic Grant to JCDH). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hautefort I, Thompson A, Eriksson-Ygberg S, Parker ML, Lucchini S, et al. During infection of epithelial cells Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium undergoes a time-dependent transcriptional adaptation that results in simultaneous expression of three type 3 secretion systems. Cellular microbiology. 2008;10:958–984. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01099.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crump JA, Luby SP, Mintz ED. The global burden of typhoid fever. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2004;82:346–353. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galan JE. Salmonella interactions with host cells: type III secretion at work. Annual review of cell and developmental biology. 2001;17:53–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia-del Portillo F. Salmonella intracellular proliferation: where, when and how? Microbes and infection/Institut Pasteur. 2001;3:1305–1311. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(01)01491-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abrahams GL, Hensel M. Manipulating cellular transport and immune responses: dynamic interactions between intracellular Salmonella enterica and its host cells. Cellular microbiology. 2006;8:728–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haraga A, Ohlson MB, Miller SI. Salmonellae interplay with host cells. Nature reviews. 2008;6:53–66. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nathan C, Shiloh MU. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates in the relationship between mammalian hosts and microbial pathogens. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:8841–8848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.8841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shiloh MU, Nathan CF. Reactive nitrogen intermediates and the pathogenesis of Salmonella and mycobacteria. Current opinion in microbiology. 2000;3:35–42. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)00048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mastroeni P, Harrison JA, Robinson JH, Clare S, Khan S, et al. Interleukin-12 is required for control of the growth of attenuated aromatic-compound-dependent Salmonellae in BALB/c mice: role of gamma interferon and macrophage activation. Infection and immunity. 1998;66:4767–4776. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4767-4776.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eriksson S, Bjorkman J, Borg S, Syk A, Pettersson S, et al. Salmonella typhimurium mutants that downregulate phagocyte nitric oxide production. Cellular microbiology. 2000;2:239–250. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2000.00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vazquez-Torres A, Fantuzzi G, Edwards CK, 3rd, Dinarello CA, Fang FC. Defective localization of the NADPH phagocyte oxidase to Salmonella-containing phagosomes in tumor necrosis factor p55 receptor-deficient macrophages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:2561–2565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041618998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bumann D. System-level analysis of Salmonella metabolism during infection. Current opinion in microbiology. 2009;12:559–567. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alteri CJ, Smith SN, Mobley HL. Fitness of Escherichia coli during urinary tract infection requires gluconeogenesis and the TCA cycle. PLoS pathogens. 2009;5:e1000448. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bowden SD, Rowley G, Hinton JC, Thompson A. Glucose and glycolysis are required for the successful infection of macrophages and mice by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Infection and immunity. 2009;77:3117–3126. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00093-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paterson GK, Cone DB, Peters SE, Maskell DJ. Redundancy in the requirement for the glycolytic enzymes phosphofructokinase (Pfk) 1 and 2 in the in vivo fitness of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Microbial pathogenesis. 2009a;46:261–265. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paterson GK, Cone DB, Northen H, Peters SE, Maskell DJ. Deletion of the gene encoding the glycolytic enzyme triosephosphate isomerase (tpi) alters morphology of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and decreases fitness in mice. FEMS microbiology letters. 2009b;294:45–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tchawa Yimga M, Leatham MP, Allen JH, Laux DC, Conway T, et al. Role of gluconeogenesis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle in the virulence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium in BALB/c mice. Infection and immunity. 2006;74:1130–1140. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.2.1130-1140.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steele-Mortimer O, Meresse S, Gorvel JP, Toh BH, Finlay BB. Biogenesis of Salmonella typhimurium-containing vacuoles in epithelial cells involves interactions with the early endocytic pathway. Cellular microbiology. 1999;1:33–49. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.1999.00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beuzon CR, Meresse S, Unsworth KE, Ruiz-Albert J, Garvis S, et al. Salmonella maintains the integrity of its intracellular vacuole through the action of SifA. The EMBO journal. 2000;19:3235–3249. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.13.3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mota LJ, Ramsden AE, Liu M, Castle JD, Holden DW. SCAMP3 is a component of the Salmonella-induced tubular network and reveals an interaction between bacterial effectors and post-Golgi trafficking. Cellular microbiology. 2009;11:1236–1253. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cronan JEj, LaPorte D. Washington DC: ASM Press; 1996. Tricarboxylic acid cycle and glyoxylate bypass; (eds) Nea, editor. pp. 206–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wray C, Sojka WJ. Experimental Salmonella typhimurium infection in calves. Research in veterinary science. 1978;25:139–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith HO, Levine M. A phage P22 gene controlling integration of prophage. Virology. 1967;31:207–216. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(67)90164-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang RF, Kushner SR. Construction of versatile low-copy-number vectors for cloning, sequencing and gene expression in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1991;100:195–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woodcock DM, Crowther PJ, Doherty J, Jefferson S, DeCruz E, et al. Quantitative evaluation of Escherichia coli host strains for tolerance to cytosine methylation in plasmid and phage recombinants. Nucleic acids research. 1989;17:3469–3478. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.9.3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Humphreys S, Stevenson A, Bacon A, Weinhardt AB, Roberts M. The alternative sigma factor, sigmaE, is critically important for the virulence of Salmonella typhimurium. Infection and immunity. 1999;67:1560–1568. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.1560-1568.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenberger CM, Finlay BB. Macrophages inhibit Salmonella typhimurium replication through MEK/ERK kinase and phagocyte NADPH oxidase activities. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:18753–18762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110649200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oswald IP, Lantier F, Moutier R, Bertrand MF, Skamene E. Intraperitoneal infection with Salmonella abortusovis is partially controlled by a gene closely linked with the Ity gene. Clinical and experimental immunology. 1992;87:373–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb03005.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baumler AJ, Tsolis RM, Valentine PJ, Ficht TA, Heffron F. Synergistic effect of mutations in invA and lpfC on the ability of Salmonella typhimurium to cause murine typhoid. Infection and immunity. 1997;65:2254–2259. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2254-2259.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cvitkovitch DG, Gutierrez JA, Bleiweis AS. Role of the citrate pathway in glutamate biosynthesis by Streptococcus mutans. Journal of bacteriology. 1997;179:650–655. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.650-655.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schilling CH, Palsson BO. Assessment of the metabolic capabilities of Haemophilus influenzae Rd through a genome-scale pathway analysis. Journal of theoretical biology. 2000;203:249–283. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2000.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schilling CH, Covert MW, Famili I, Church GM, Edwards JS, et al. Genome-scale metabolic model of Helicobacter pylori 26695. Journal of bacteriology. 2002;184:4582–4593. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.16.4582-4593.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klose KE, Mekalanos JJ. Simultaneous prevention of glutamine synthesis and high-affinity transport attenuates Salmonella typhimurium virulence. Infection and Immunity. 1997;65:587–596. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.587-596.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKinney JD, Honer zu Bentrup K, Munoz-Elias EJ, Miczak A, Chen B, et al. Persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in macrophages and mice requires the glyoxylate shunt enzyme isocitrate lyase. Nature. 2000;406:735–738. doi: 10.1038/35021074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson RB, Maloy SR. Isolation and characterization of Salmonella typhimurium glyoxylate shunt mutants. Journal of bacteriology. 1987;169:3029–3034. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.7.3029-3034.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chakravortty D, Hansen-Wester I, Hensel M. Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 mediates protection of intracellular Salmonella from reactive nitrogen intermediates. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2002;195:1155–1166. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Husain M, Bourret TJ, McCollister BD, Jones-Carson J, Laughlin J, et al. Nitric oxide evokes an adaptive response to oxidative stress by arresting respiration. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283:7682–7689. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708845200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ehrt S, Schnappinger D, Bekiranov S, Drenkow J, Shi S, et al. Reprogramming of the macrophage transcriptome in response to interferon-gamma and Mycobacterium tuberculosis: signaling roles of nitric oxide synthase-2 and phagocyte oxidase. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2001;194:1123–1140. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.8.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carrillo-Castaneda G, Ortega MV. Mutants of Salmonella typhimurium lacking phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase and alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase activities. Journal of bacteriology. 1970;102:524–530. doi: 10.1128/jb.102.2.524-530.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Greene RC. Biosynthesis of methionine. In: Neihardt FC, Ingraham JL, Lin ECC, Low KB, Magasanik B, et al., editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 542–560. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kohanski MA, Dwyer DJ, Hayete B, Lawrence CA, Collins JJ. A common mechanism of cellular death induced by bactericidal antibiotics. Cell. 2007;130:797–810. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kohanski MA, Dwyer DJ, Collins JJ. How antibiotics kill bacteria: from targets to networks. Nature Reviewss Microbiol. 2010;8:423–435. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Richter-Dahlfors A, Buchan AM, Finlay BB. Murine salmonellosis studied by confocal microscopy: Salmonella typhimurium resides intracellularly inside macrophages and exerts a cytotoxic effect on phagocytes in vivo. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1997;186:569–580. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.4.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Santos RL, Zhang S, Tsolis RM, Kingsley RA, Adams LG, et al. Animal models of Salmonella infections: enteritis versus typhoid fever. Microbes and infection/Institut Pasteur. 2001;3:1335–1344. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(01)01495-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grant AJ, Restif O, McKinley TJ, Sheppard M, Maskell DJ, et al. Modelling within-host spatiotemporal dynamics of invasive bacterial disease. PLoS biology. 2008;6:e74. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Strains and plasmids used in this study.

(0.03 MB PDF)