Abstract

Objective

To describe the normative course of maternal sleep during the first four months postpartum.

Study Design

Sleep was objectively measured using continuous wrist actigraphy. This was a longitudinal, field-based assessment of nocturnal sleep during postpartum weeks two through 16. Fifty mothers participated during postpartum weeks two through 13; 24 participated during postpartum weeks nine through 16.

Results

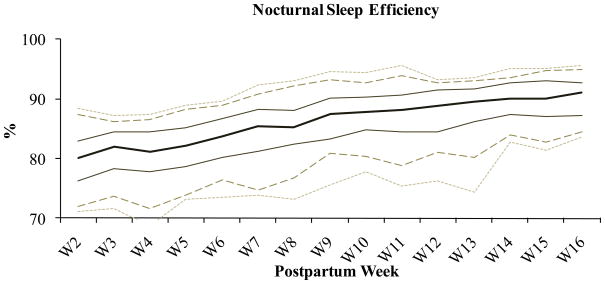

Maternal nocturnal sleep time was 7.2 (SD±.95) hours and did not change significantly across postpartum weeks two through 16. Maternal sleep efficiency did improve across weeks two (79.7% [SD±5.5]) through 16 (90.2% [SD±3.5]) as a function of decreased sleep fragmentation across weeks two (21.7 [SD±5.2]) through 16 (12.8 [SD±3.3]).

Conclusion

Though postpartum mothers’ total sleep time was higher than expected during the initial postpartum months, this sleep was highly fragmented (similar to fragmenting sleep disorders) and inefficient. This profile of disturbed sleep should be considered in intervention designs and family leave policies.

Keywords: Sleep, Postpartum, Maternal, Normative, Actigraphy

Introduction

A major barrier to understanding the relations between sleep and postpartum functioning is the lack of normative longitudinal postpartum sleep data on non-depressed postpartum women. A thorough description of normative postpartum sleep is necessary to better understand the relations between sleep and postpartum depression. Specifically, postpartum sleep disturbance has received increasing attention among women’s health researchers, because it has been identified as a precipitating factor for depressive symptoms.1,2

In addition, preventative and intervention efforts to reduce sleep disturbance focus on increasing maternal sleep time3,4, based on a presumption that partial sleep deprivation (an overall attenuation in the total amount of sleep) is to blame for adverse mood effects.2 This presumption makes conceptual sense because partial sleep deprivation is known to erode mood, cognitive processes, and psychomotor skills.5 However, sleep fragmentation is an aspect of sleep disturbance that is generally under addressed within postpartum sleep studies. Furthermore, sleep fragmentation may be equally, or possibly more important to consider than partial sleep deprivation during the early postpartum period. In contrast to sleep deprivation, sleep fragmentation causes frequent interruptions to sleep architecture throughout the night while generally preserving total sleep time.6

Sleep fragmentation is increasingly studied because it is a distinct feature of highly prevalent sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea7 and periodic limb movement disorder.8 Consistent with sleep deprivation, sleep fragmentation - whether experimentally induced or the result of a sleep disorder - also leads to excessive daytime sleepiness and decrements in cognitive performance9, executive function10, and quality of life.11

Thus, the cumulative data on partial sleep deprivation and sleep fragmentation support the notion that certain profiles of sleep may not be sufficient to maintain normal functioning. Rather, a minimum duration of uninterrupted sleep may be necessary to maximize sleep’s neurocognitive benefits.6,12,13

It is reasonable to expect that sleep fragmentation is a primary component of postpartum sleep disturbance. Subjective sleep disturbance is positively associated and sleep effectiveness is negatively associated with maternal fatigue through 6 weeks postpartum.14 New mothers report being surprised by their level of sleep disturbance and daytime exhaustion; mothers describe their sleep as a negotiated behavior in which they strategically adjust their sleep schedules to match their newborns’ polyphasic sleep pattern.15 Compared to pregnancy, the postpartum period is characterized by a self-report of three times the number of nighttime awakenings, a decrease in sleep efficiency, and twice the level of daytime sleepiness.16 The majority of postpartum mothers’ sleep disturbances are caused by the newborns’ sleep and feeding schedules.17

It is appropriate that maternal sleep disturbance should be carefully considered since it is likely a precursor of postpartum depression, which is a significant health concern. However, it is necessary to first understand normative postpartum sleep profiles, especially sleep efficiency and sleep fragmentation, so that we may better describe the etiology of postpartum depression. Our purpose was to provide normative, objectively measured, field-based reference values for nocturnal time in bed, nocturnal sleep time, nocturnal sleep efficiency, nocturnal sleep fragmentation, and diurnal nap frequencies and their durations from the second through 16th week following delivery among non-depressed postpartum mothers with healthy infants.

Quantification of normative postpartum sleep reference values, and specifically quantification of sleep duration versus fragmentation, was the primary goals of this work. So that our data would have high ecological validity, we used longitudinal field-based actigraphy among a socioeconomically diverse sample of postpartum women. The data are presented in graphic form as mean and percentiles to broaden their utility as reference values. Based on the extant postpartum sleep literature and in the context of known effects of fragmenting sleep disorders, we expected to find that postpartum mothers’ total sleep time would be low, that their sleep would be highly fragmented, and that these effects would remain constant across the first several postpartum months.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The study was approved by the West Virginia University Office of Research Compliance. Women were recruited prenatally via childbirth classes in their third trimester, community advertisements, and word-of-mouth. Phone screening was conducted prior to administration of informed consent and health information portability and accountability act authorization. Women were excluded from participation and referred for further evaluation and treatment, as appropriate, on the bases of a history of major depressive or anxiety disorder, a score ≥16 on the Center for Epidemiological Studies of Depression18, pregnancy with multiples, premature infant delivery, or infant admission to the neonatal intensive care unit. All other respondents who were pregnant or whose infant was less than 1 week old were recruited for participation.

In the first year of the study we included both primiparous and multiparous women who participated during postpartum weeks 9 through 16 (i.e. phase one). During this time the project became funded and, based on the success of the initial data collection, we changed the protocol to include only primiparous women who participated during postpartum weeks 2 through 13 (i.e. phase two).

Actigraphy and Sleep Diary

A member of the research team visited participant’ homes during each week of the study. During each home visit participants were given a new actigraph and personal digital assistant (PDA). Sleep measures were objectively recorded with continuous wrist actigraphy using Mini Mitter’s Actiwatch-64 (AW-64) actigraphs. An actigraph is a small, nonintrusive wristwatch-like device that collects motion data as the participant follows their normal daily routine. The AW-64 has been validated for recognition of adult sleep based on these movement patterns.19–21

The highest resolution was used (15-second epochs) allowing up to 11 days of continuous recording. Actiware Software Version 5.5 was used to manage, analyze, and archive actigraphy data. The Actiware software utilizes an algorithm that scores individual epochs as sleep or wake by comparison to a wake threshold value. The validated default wake threshold value parameter setting was used (40).

Periods of nocturnal sleep and daytime naps were participant-identified for analyses using PDA-based sleep diaries (Bruner Consulting, Inc.) completed in real time at every bed and rise time for nocturnal sleep and diurnal nap periods. The software also has a method for retrospective entries, which are annotated as retrospective. Using the sleep diary, we identified the daytime nap and nocturnal sleep periods reported by the participant. To reduce participant burden, we did not ask them to indicate the exact moment of lights out or use the actigraph’s event marker. Thus, we made no attempt to determine sleep-onset-latency and this measure is not possible for analysis. The following measures were analyzed using Actiware software during identified sleep periods:

Time in bed

Minutes from the first epoch identified as sleep (the first 2-minute bout of immobility following the diary-indicated bedtime) to the final 2-minute bout of immobility preceding wake closest to diary-indicated risetime.

Total sleep time

Minutes of sleep during time in bed.

Sleep efficiency

Percent of minutes of sleep during time in bed.

Fragmentation index

Sum of percent mobile (percent of epochs during time in bed scored as mobile, including sub-wake threshold) and the ratio of percent 1-minute immobile bouts to percent mobile (percent of 1-minute bouts during time in bed scored as immobile).

Depression scores

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) was administered at home visits during postpartum weeks 9 and 12 for phase one, and during postpartum weeks 2, 4, 6, 8 10, and 12 for phase two. Each of the 10 items has four response options, with a total range = 0–30. Seven of the items are reverse-scored and the response options vary. A question and answer example are, “I have felt sad or miserable” (Yes, most of the time; Yes, quite often; Not very often; No, not at all). Instrument validation indicated that cutoff at 9/10 and at 11/12 have high sensitivity and specificity for identifying possible and probable cases, respectively, of postpartum depression.22 Participants’ data were entirely excluded from all analyses reported here (but the participant was not dropped from the study) if they had an EPDS score greater >9 at any administration.

Twenty-two women were excluded from analyses on the basis of an Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale score greater than nine during one or more weeks during the study. Analyses were based on data from 22 mothers in the first phase (postpartum weeks 9 through 16) and 50 in the second phase (postpartum weeks 2 through 13). In phase one, one participant withdrew from the study after four weeks. In phase two, five participants withdrew from the study after four (n=2), five, seven and eight weeks, respectively. No participant withdrew from the study due to postpartum depression and those who were dropped from the current analyses did not have a significantly higher depression scores; therefore, their data recorded prior to their withdraw from the study are included in the analyses. In both phases, some data were lost due to actigraph or PDA malfunction, and participant non-adherence to the protocol. Among the 72 postpartum participants (excluding weeks lost due to participant withdraw from the study), there were 31 weeks of missing data out of 745 possible recording weeks (4.2% of possible weeks missing).

Statistical Analyses

The size of the first sample phase was exploratory; the second phase sample was determined using power analysis for the larger study based on effect sizes from the PI’s previous work with the same actigraphy system.23 It was determined that (with 2-tailed alpha level=.05 and sigma=.80) 43 subjects were required. Our recruitment of 70 participants exceeded that goal, to allow us greater confidence in our ability to generalize for this normative description and protect against attrition.

Data from each participant were averaged within each postpartum week. A minimum of four days of recording time were required to calculate each participant’s week average. Data were analyzed with SPSS version 16.0. Descriptive statistics were calculated. One-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) were used to determine statistically significant differences between groups. Linear trend analyses were used to determine statistically significant linear changes across postpartum weeks. Chi square analyses were used to evaluate frequency data. Analyses were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05. Cohen’s d was used to describe effect sizes. Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation.

Results

The number of participants in each phase who contributed data at each postpartum week is shown on Table 1. Demographic data are shown on Table 2. There were insufficient single participants to examine differences based on marital status. However, income was significantly correlated with sleep efficiency and sleep fragmentation during weeks 2 through 6. During each of these weeks, lower income was associated with higher sleep efficiency (week 2 r=−.428, p<.001; week 3 r=−.398, p=.002; week 4 r=−.337, p=.007; week 5 r=−.348, p=.005; week 6 r=−.298, p=.018) and lower sleep fragmentation (week 2 r=.443, p<.001; week 3 r=.369, p=.004; week 4 r=.344, p=.006; week 5 r=.344, p=.006; week 6=.253, p=.045).

Table 1.

Numbera of Primiparous and Multiparous Participants Each Postpartum Week

| Postpartum Week | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort 1 | primip | 11 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |||||||

| multip | 10 | 11 | 11 | 8 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 10 | ||||||||

| Cohort 2 | primip | 47 | 47 | 50 | 50 | 46 | 45 | 46 | 43 | 44 | 44 | 42 | 46 | |||

| Total Contributing | 47 | 48 | 50 | 49 | 44 | 43 | 46 | 64 | 65 | 66 | 61 | 66 | 21 | 20 | 20 | |

N at each week variable due to missing data - values were averaged for each participant for each postpartum week; a minimum of 4 recording nights were required to calculate each weekly average.

Table 2.

Participant Demographics

| Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 27.3 | 5.8 |

| Education (years) | 16.2 | 2.8 |

| Annual Household Income | $62,156 | $37,699 |

| Married/Cohabitating | 91.0% | |

| Caucasian | 92.9% | |

| Primiparous | 86.1% | |

| Vaginal Delivery | 77.5% | |

| Exclusively breastfeedinga | 75.0% |

At beginning of study

Mean (SD) EPDS scores were 4.36 (2.56) during week 2, 3.18 (2.36) during week 4, 3.00 (2.61) during week 6, 2.56 (2.48) during week 8, 3.59 (2.17) during week 9, 2.57 (2.32) during week 10, and 2.66 (2.25) during week 12.

Nocturnal Sleep Periods

There were no statistically significant differences between primiparous and multiparous postpartum women during the period when the two phases overlapped (weeks 9–13) on any nocturnal sleep measure at any week; thus, the two phases were combined for these analyses. There were no statistically significant delivery methods (vaginal or Cesarean section) differences on any sleep measure through postpartum week 6 (periods beyond this were not analyzed).

Maternal sleep reference values (mean, standard deviation, and range) for nocturnal time in bed, nocturnal sleep time, nocturnal sleep efficiency, and nocturnal sleep fragmentation are shown for postpartum weeks two through 16 on Table 3. Linear trend analyses (F and p values at the bottom of Table 3) show that across postpartum weeks two through 16 nocturnal sleep time did not change significantly. Postpartum women slept an average of 7.2 (SD±.95) hours at night during the first four months postpartum. Across this same period, linear trend analysis showed that nocturnal time in bed and nocturnal sleep fragmentation significantly decreased, and nocturnal sleep efficiency significantly, and consequently, increased. Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4 show mean and standard percentiles for maternal nocturnal time in bed, nocturnal sleep time, nocturnal sleep efficiency, and nocturnal sleep fragmentation, respectively, during each postpartum week.

Table 3.

Proportion of participants who napped (according to diary and objective actigraphy recording) at each postparum week, and the average (SD) number of naps per week

| Postpartum Week | % partipants who napped | number of naps | nap duration (min) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | SD | mean | SD | ||

| 2 | 66.0% | 2.9 | 2.1 | 161.5 | 122.9 |

| 3 | 48.9% | 2.5 | 1.3 | 153.8 | 95.8 |

| 4 | 46.0% | 2.3 | 1.7 | 130.2 | 124.2 |

| 5 | 52.0% | 2.2 | 1.3 | 141.0 | 109.2 |

| 6 | 41.3% | 2.1 | 1.4 | 155.2 | 109.9 |

| 7 | 37.8% | 1.9 | 1.1 | 204.0 | 196.5 |

| 8 | 45.7% | 1.6 | 0.6 | 144.0 | 97.5 |

| 9 | 43.8% | 1.8 | 1.2 | 45.9 | 90.5 |

| 10 | 43.1% | 1.9 | 1.4 | 48.0 | 111.3 |

| 11 | 25.8% | 2.1 | 1.0 | 43.7 | 105.4 |

| 12 | 34.4% | 2.1 | 1.6 | 52.0 | 148.8 |

| 13 | 24.2% | 1.5 | 0.6 | 28.0 | 92.6 |

| 14 | 33.3% | 1.8 | 1.2 | 15.5 | 58.3 |

| 15 | 35.0% | 1.7 | 1.1 | 17.6 | 64.5 |

| 16 | 26.3% | 1.2 | 0.4 | 9.7 | 38.5 |

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

Diurnal Nap Periods

In order to determine whether daytime napping accounted for a substantial increase in the 24-hour sleep time among participants (this is often recommended as a strategy for increasing total sleep time), descriptive information about napping behavior was calculated. The proportion of postpartum participants who took daytime naps during each postpartum week, along with the average number and length of naps is indicated on Table 4. Note that these values are the proportion of participants who napped at least once during each postpartum week and the average number of naps they took during that week (not each day during the week). After postpartum week 2, fewer than 50% of postpartum women napped at least once each week. Those who napped at least once in a week took an average of 2.1 (SD±1.4) naps each week that lasted a cumulative 2.6 (SD±2.3) hours. During postpartum weeks nine through 16 (when phase 1 participated), there was not a statistically significant difference during any postpartum week between the proportion of primiparous and multiparous women who took naps or in the number of naps they took. There were two weeks when nap duration differed based on parity: at postpartum weeks 8 [F=4.9, p=.04, d=.77] and 16 [F=13.4, p=.04, d=3.3]. Nap durations among multiparous women were significantly longer at postpartum weeks 8 (235.4 [SD±189.0] minutes) and 16 (174.7 [SD±39.8] minutes) than primiparous women’s at postpartum weeks 8 (123.5 [SD±76.4] minutes), and 16 (51.6 [SD±30.2] minutes).

Comment

The most significant contribution of these findings is that they provide much-needed normative reference values for both researchers and clinicians. We expected to find that postpartum mothers’ total sleep time would be low, that their sleep would be highly fragmented, and that these effects would remain constant across the first several postpartum months. Instead we found that on average postpartum mothers slept over seven hours at night, and this was the only measure that remained constant across the first four postpartum months. Although postpartum women obtained more total sleep time than we expected, it is important to consider this value in the context that their sleep was highly fragmented (mothers were awake nearly 2 hours during the night) throughout the early postpartum months, resulting in low sleep efficiency and necessitating a prolonged period dedicated to sleep in order to obtain this amount.

Across the first four months there was a dynamic process of improving sleep efficiency that can only be explained by decreased sleep fragmentation. In other words, as time progressed the periods of wake after sleep onset decreased, so that mothers were able to obtain the same amount of sleep in a shorter period of time. This is the only explanation because total sleep time did not change over time, whereas sleep fragmentation decreased (all wake was scored after sleep onset).

Thus, our fragmentation findings were consistent with our expectation that this is a major component of postpartum sleep disturbance and emphasize the importance of considering not only postpartum sleep duration, but also sleep fragmentation. Overall, although our data suggests that non-depressed postpartum women may not be as vulnerable to partial sleep deprivation as previously thought, they appear to be highly vulnerable to sleep fragmentation.

The generalizability of our findings is supported by their consistency with other recent reports of non-depressed postpartum women using actigraphy during overlapping postpartum weeks. Dorheim and colleagues’24 comparative sample of non-depressed mothers at two months postpartum had total sleep time of 7.8 hours, time in bed was 9.0 hours, and sleep efficiency was 87.6% and Posmontier’s25 sample of non-depressed mothers from 6–26 weeks postpartum had sleep efficiency of 89.2%. The values reported in the current study are consistent with previous reports, and cumulatively their changes across time can be considered normative. We speculate that the most reasonable explanations for the increase in sleep efficiency may be: 1) the infants may be sleeping differently (for longer periods during the night without signaling) and this is reflected by the mother’s sleep, 2) the mother’s arousal threshold may increase as her duration of sleep disturbance (and thus sleep pressure) accumulates causing her to sleep through auditory ‘cues’ (from the infant) to which she would have awakened previously, 3) the infant’s father may be taking on more childcare responsibilities as time passes, or 4) some combination of these.

The overall profile of results from our work and these others’ suggests that the significant deleterious daytime consequences frequently experienced by new mothers may be similar to the effects of fragmenting sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea and periodic limb movement disorder, which are also known to interrupt sleep architecture while preserving total sleep times and result in significant daytime dysfunction. However, although postpartum sleep may resemble profiles of sleep from fragmenting sleep disorders, postpartum sleep is not a disordered state. Rather, postpartum sleep should be considered a normative developmental period. This normative period is belied by profoundly high rates of parent-reported “infant sleep problems”26, which suggests that there is either an epidemic of sleep dysfunction among the infant population (which we think is unlikely), or that parents may have acquired unreasonable expectations about when and for how long their infant should sleep.

These reference values may be particularly useful for the development and refinement of interventions. Most randomized, controlled intervention studies have focused on changing the infant’s sleep.27–32 These interventions are generally designed for infants six months and older, by which time mothers (and perhaps fathers, who have been understudied) will have experienced significant and prolonged sleep fragmentation. Because infants’ polyphasic sleep is not likely to change, and adults who follow a polyphasic sleep schedule may experience negative consequences, the development of methods for improving maternal sleep to the point that mothers are able to function effectively should be a clinical and research focus. We echo Rychnovsky and Hunter14 in their sentiment that, “It is unclear whether the age-old advice to “nap when your baby naps” is effective in reducing postpartum fatigue”. Not only do our low rates and durations of daytime napping show that are women not taking that advice, but a brief nap during the day is unlikely to alleviate nocturnal fragmentation.

We were intrigued by our finding relating lower income to higher sleep efficiency and lower sleep fragmentation during the first 6 weeks postpartum. We speculate that these lower income participants may have had more social support, or may have been more likely to co-sleep with their infant. It is unlikely that mothers had more time to dedicate to sleep due to unemployment since it is rare for employed women to return to work before 6 weeks postpartum. We hope that future studies will consider these factors.

Finally, we submit that these data call for us to reconsider the duration of maternal leave policies in the United States where the Department of Labor, Family and Medical Leave Act33 specifies that covered employers (with 50 or more employees) must grant eligible employees up to a total of 12 work weeks of unpaid leave during any 12-month period for the birth and care of a newborn child. This policy covers about half of private sector workers.34 These data suggest that maternal sleep is significantly impaired by sleep fragmentation through at least the third month postpartum. Considering the known impact of sleep disturbance on performance, requiring women to work outside the home and further curtailing their time for sleep may not be in the best interest of the woman, her family, or society.

Future studies should continue to consider the impact of income, as well as support on postpartum sleep. In the first five weeks postpartum, we found that lower income was correlated with improved sleep efficiency and fragmentation. There were no relations between any sleep measure and income after five weeks postpartum. These findings are non-intuitive and we speculate that they may be explained by increased social support – an important contribution that may also improve future intervention studies.

The major limitation of this work is that the sample lacked ethnic/racial diversity. Our region is predominantly Caucasian, and the sample included a wide income diversity that reflected Appalachian socioeconomic diversity. However, it will be of interest for future studies to report normative values for other ethnicities, races, and geographic centers.

In sum, postpartum mothers’ total sleep times were higher than expected during the initial postpartum months; however, this sleep was highly fragmented through the first three postpartum months. The normative postpartum woman’s sleep profile should be considered in the development of postpartum sleep intervention designs and family leave policies.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participating families, and Margaux Butler, BA, Aryn Karpinski, MS, Virginia Patel, BA, Jasal Pragani, BA, Jose Sanchez, BA, Eleanor Santy, BS, and Michael Verzino, BS, who assisted with data collection and processing. Yvonne Norrbom, BA, assisted with manuscript preparation. We also thank the anonymous journal Reviewers whose comments and suggestions substantially improved our work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dennis CL, Ross L. Relationships among infant sleep patterns, maternal fatigue, and development of depressive symptomatology. Birth. 2005;32(3):187–193. doi: 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2005.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross LE, Sellers EM, Gilbert Evans SE, Romach MK. Mood changes during pregnancy and the postpartum period: Development of a biopsychosocial model. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;109:457–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0047.2004.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meltzer LJ, Mindell JA. Nonpharmacologic treatments for pediatric sleeplessness. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2004;51(1):135–151. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(03)00178-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stremler R, Hodnett E, Lee K, MacMillan S, Mill C, Ongcangco L, Willan A. A behavioral-educational intervention to promote maternal and infant sleep: a pilot randomized, controlled trial. Sleep. 2006;29:1609–1615. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.12.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonnet MH. Performance and sleepiness as a function of frequency and placement of sleep disruption. Psychophysiology. 1986;23(3):263–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1986.tb00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonnet MH. Sleep Fragmentation. In: Lenfant C, editor. Sleep Deprivation. Marcel Dekker; NY: 2005. pp. 103–117. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shamsuzzaman AS, Gersh BJ, Somers VK. Obstructive sleep apnea: implications for cardiac and vascular disease. JAMA. 2003;290(14):1906–1914. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.14.1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durmer JS, Dinges DF. Neurocognitive consequences of sleep deprivation. Semin Neurol. 2005;25(1):117–29. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-867080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Downey R, Bonnet MH. Performance during frequent sleep disruption. Sleep. 1987;10(4):354–363. doi: 10.1093/sleep/10.4.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong KK, Grunstein RR, Bartlett DJ, Gordon E. Brain function in obstructive sleep apnea: results from the Brain Resource International Database. J Integr Neurosci. 2006;5(1):111–121. doi: 10.1142/s0219635206001033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore P, Bardwell WA, Ancoli-Israel S, Dimsdale JE. Association between polysomnographic sleep measures and health-related quality of life in obstructive sleep apnea. Journal of Sleep Research. 2001;10(4):303–308. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2001.00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franken P. Long-term vs. short-term processes regulating REM sleep. Journal of Sleep Research. 2002;11(1):17–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2002.00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stepanski EJ. The effect of sleep fragmentation on daytime function. Sleep. 2002;25(3):268–276. doi: 10.1093/sleep/25.3.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rychnovsky J, Hunter LP. The relationship between sleep characteristics and fatigue in healthy postpartum women. Womens Health Issues. 2009;19:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kennedy HP, Gardiner A, Gay C, Lee KA. Negotiating sleep: a qualitative study of new mothers. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2007;21(2):114–122. doi: 10.1097/01.JPN.0000270628.51122.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishihara K, Horiuchi S. Changes in sleep patterns of young women from late pregnancy to postpartum: relationships to their infants’ movements. Percept Mot Skills. 1998;87:1043–1056. doi: 10.2466/pms.1998.87.3.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunter LP, Rychnovsky JD, Yount SM. A selective review of maternal sleep characteristics in the postpartum period. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2009;38(1):60–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychogical Measure. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oakley NR. Validation with Polysomnography of the Sleepwatch Sleep/Wake Scoring Algorithm used by the Actiwatch Activity Monitoring System. Cambridge Neurotechnology. 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edinger JD, Means MK, Stechuchak KM, Olsen MK. A pilot study of inexpensive sleep assessment devices. Behavioral Sleep Medicine. 2004;2(1):41–49. doi: 10.1207/s15402010bsm0201_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benson K, Friedman L, Noda A, Wicks D, Wakabayashi E, Yesavage J. The measurement of sleep by actigraphy: direct comparison of 2 commercially available actigraphs in a nonclinical population. Sleep. 2004;27(5):986–989. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.5.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression scale. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;150:872–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montgomery-Downs HE, Gozal D. Toddler behavior following polysomnography: Effects of unintended sleep disturbance. Sleep. 2006;29(10):1282–1287. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.10.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dørheim SK, Bondevik GT, Eberhard-Gran M, Bjorvatn B. Subjective and objective sleep among depressed and non-depressed postnatal women. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;119(2):128–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Posmontier B. Sleep quality in women with and without postpartum depression. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2008;37(6):722–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00298.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reid GJ, Huntley ED, Lewin DS. Insomnias of childhood and adolescence. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2009;18:979–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pinilla T, Birch LL. Help me make it through the night: behavioral entrainment of breast-fed infants’ sleep patterns. Pediatrics. 1993;91(2):436–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolfson A, Lacks P, Futterman A. Effects of parent training on infant sleeping patterns, parents’ stress, and perceived parental competence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60(1):41–84. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.St James-Roberts I, Sleep J, Morris S, Owen C, Gillham P. Use of a behavioural programme in the first 3 months to prevent infant crying and sleeping problems. J Paediatr Child Health. 2001;37(3):289–297. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2001.00699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Symon BG, Marley JE, Martin AJ, Norman ER. Effect of a consultation teaching behaviour modification on sleep performance in infants: a randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust. 2005;182(5):215–218. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb06669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hiscock H, Bayer J, Gold L, Hampton A, Ukoumunne OC, Wake M. Improving infant sleep and maternal mental health: a cluster randomised trial. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92(11):952–958. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.099812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hiscock H, Wake M. Infant sleep problems and postnatal depression: a community-based study. Pediatrics. 2001;107(6):1317–22. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.United States Department of Labor. Family and Medical Leave Act. Available online at: http://www.dol.gov/whd/fmla/index.htm (accessed 8/2/2010)

- 34.Ruhm C. Policy watch: The Family and Medical Leave Act. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 1997;11(3):175–186. [Google Scholar]