Abstract

Stress exacerbates several physical and psychological disorders. Voluntary exercise can reduce susceptibility to many of these stress-associated disorders. In rodents, voluntary exercise can reduce hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) axis activity in response to various stressors as well as upregulate several brain neurotrophins. An important issue regarding voluntary exercise is whether its effect on the reduction of HPA axis activation in response to stress is due to the physical activity itself or simply the enhanced environmental complexity provided by the running wheels. The present study compared the effects of physical activity and environmental complexity (that did not increase physical activity) on HPA axis habituation to repeated stress and modulation of brain neurotrophin mRNA expression. For six weeks, male rats were given free access to running wheels (exercise group), given 4 objects that were repeatedly exchanged (increased environmental complexity group), or housed in standard cages. On week 7, animals were exposed to 11 consecutive daily 30-min sessions of 98-dBA noise. Plasma corticosterone and adrenocorticotropic hormone were measured from blood collected directly after noise exposures, and brains, thymi, and adrenal glands were collected on day 11. Although rats in both the exercise and enhanced environmental complexity groups expressed higher levels of BDNF and NGF mRNA in several brain regions, only exercise animals showed quicker glucocorticoid habituation to repeated audiogenic stress. These results suggest that voluntary exercise, independently from other environmental manipulations, accounts for the reduction in susceptibility to stress.

Keywords: voluntary physical activity, HPA- axis, stress habituation, BDNF, in situ hybridization

1. Introduction

It is well established that stress precipitates or exacerbates several physical and psychological disorders (Brown & Harris, 1987; Pasternac & Talajic, 1991; Hammen et al., 1992; Stratakis & Chrousos, 1995; Sapolsky, 1996; Arborelius et al., 1999, 2004; Vanitallie, 2002). Among other effects, stress activates the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) axis, which leads to the release of glucocorticoids into the general vasculature. Repeated exposure to the same stressor often diminishes HPA axis activation to that stressor, a phenomenon termed stress habituation (Marti & Armario, 1998; Grissom & Bhatnagar, 2009). Although glucocorticoids regulate many vital physiologic functions under normal and acute stress conditions, it is their sustained release by repeated stress that is strongly associated with disorders (Chrousos & Gold, 1992; Tsigos & Chrousos, 1994; McEwen, 2000; Charmandari et al., 2005; Jokinen & Nordstrom, 2008). Thus, stress habituation is likely an important mechanism to keep physiological and psychological functions optimal in the face of repeated stress.

Interestingly, voluntary physical activity has been reported to reduce susceptibility to many stress-associated disorders (Manson et al., 1992; Chodzko-Zajko & Moore, 1994; Wannamethee et al., 1998; Fox, 1999; Dunn et al., 2001; Oguma & Shinoda-Tagawa, 2004; Kruk & Aboul-Enein, 2006). Importantly, voluntary exercise regimens moderate several stress-related responses in rodents (Greenwood et al., 2007; Greenwood & Fleshner, 2008; Day et al., 2008; Sasse et al., 2008), including HPA axis activation under some acute and repeated stress conditions (Dishman et al., 1998; Droste et al., 2007; Sasse et al., 2008; Campeau et al., 2010b). Various exercise regimens have also been associated with upregulation of neurotrophins in several brain regions, particularly in the hippocampal formation (Oliff et al., 1998; Russo-Neustadt et al., 2001; Adlard & Cotman, 2004). This is in contrast to the effects of stress, which regularly reduce neurotrophin expression (Foreman et al., 1993; Smith et al., 1995; Ueyama et al., 1997; Cirulli & Alleva, 2009; Campeau et al., 2010a).

An important issue with regard to the finding that voluntary physical activity can reduce acute HPA axis activation to some stressors (Droste et al., 2007; Campeau et al., 2010b), and enhance the rate or final extent of habituation to repeated stress (Sasse et al., 2008), is the exact contribution of the physical activity component to these observed effects. In these studies, isolated rats kept in an otherwise empty plastic cage were compared with rats similarly housed, but with a freely accessible running wheel. One possibility is that the impoverished condition of the isolated control rats (Rosenzweig & Bennett, 1977) is improved by the addition of the running wheels, independent of the increase in physical activity for the rats housed with the running wheels. The consistent lack of correlation between the amount of physical activity achieved by physically active animals and their observed HPA axis responses to acute or repeated stress may support this possibility (Sasse et al., 2008; Campeau et al., 2010b). The present study therefore sought to determine if simply adding complexity to isolated rats' cages, without noticeably increasing their physical activity, would also reduce acute or repeated HPA axis responses to audiogenic stress, compared to isolated rats with or without freely accessible running wheels. In addition, the effects of these manipulations on expression of neurotrophins and their receptor mRNAs were compared following repeated stress, to obtain an independent index of the effectiveness of these different manipulations in isolated rats.

2. Results

Running Data

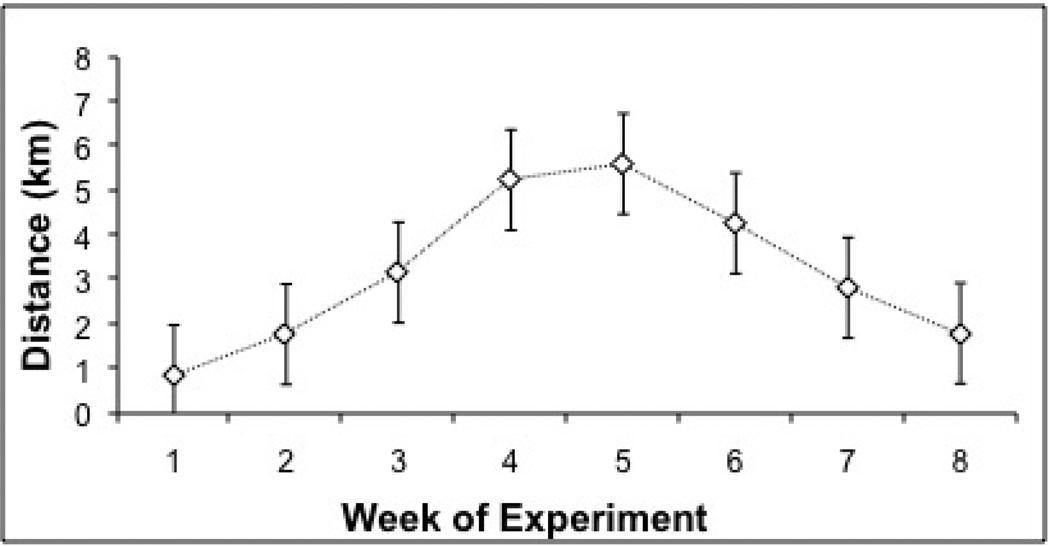

The average daily distances (in km) run by exercise (X) animals were calculated for each week of the experiment, as shown in Figure 1. The average daily running distances for each week are consistent with our previous observations (Sasse et al.,2008), and those of other studies employing Sprague-Dawley rats (Noble et al., 1999; Moraska et al., 2001). Running distance was not significantly correlated with gland weight, plasma glucocorticoid levels, or BDNF or NGF mRNA expression in any region.

Figure 1. Average Daily Running Distance over Course of Experiment.

Average daily running distance (km) of exercised animals for weeks 1–8 of Experiment. Repeated stress exposures took place over weeks 7 and 8.

Body Weight

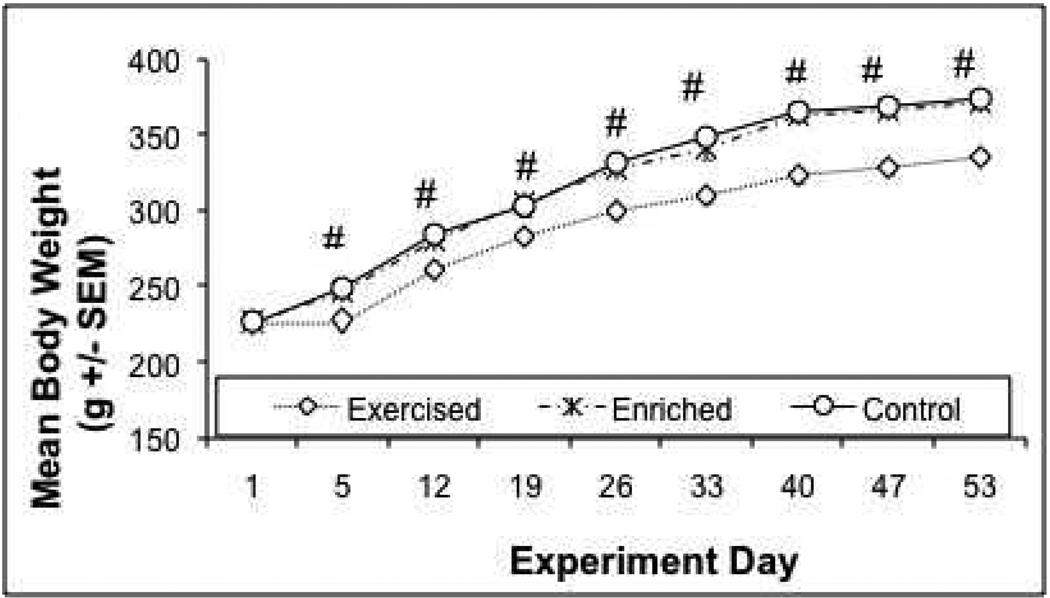

Animals were weighed on days 1, 5, 12, 19, 26, 33, 40, 47, and 53. There was a significant day X treatment interaction over the course of the study (F 16, 360 = 9.528, p=0 .0001), indicating a differential weight regulation across the different treatments over time. This interaction is explained by a lack of difference between groups on Day 1 (F 2, 45 = 0.0666, p = 0 .9357), but reliable and increasing body weight differences thereafter (p < 0.05). Daily post-hoc analyses found that the exercised animals gained significantly less weight compared to both the home cage control (HC) and increased environmental complexity (IC) animals (which never differed significantly from each other) beginning on day 5 of the experiment (Tukey HSD p’s = 0 .0001), as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Mean Body Weight (g)+/− SEM Over Course of Experiment.

Animals were weighed on days 1, 5, 12, 19, 26, 33, 40, 47, and 53 of experiment (noise began on day 43). Body weights were equivalent between groups on day 1, but were significantly lower in exercised animals on day 5 and thereafter compared to the other two groups, which did not differ from one another. #: Exercise group significantly different from home cage control and increased cage complexity groups, Tukey's HSD (p's < 0.05).

Adrenals/Thymi Weights

Adrenals (left and right glands together) and thymus glands were weighed following sacrifice. Gland weights were analyzed in two ways. First, a corrected weight was calculated by dividing gland weight in milligrams by individual body weight in grams. Analyses on uncorrected gland weights were also performed. There were significant differences between groups for corrected thymi and adrenals (F 2, 45 = 3.978, p = 0.026, and F 2, 45 = 5.846, p = 0.006, respectively). Post-hoc analyses found that the exercised animals had smaller corrected thymi weights than controls (Tukey HSD p=0.019). Corrected adrenal gland weights were higher in exercised animals compared to HC and IC animals (Tukey’s HSD p’s < 0.05). One way ANOVA on uncorrected values revealed significant differences between groups for thymi only (F 2, 45 = 8.861, p = 0.001). Post-hoc analyses found that the exercised animals had smaller uncorrected thymi weights than control and complex cage animals (Tukey HSD p’s < 0.05), as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Corrected and uncorrected adrenal and thymus gland weights on day 11 of 98-dBA noise stress.

| Experimental Group |

Mean Adrenal Weight (mg (SEM)) |

Mean Corrected Adrenal Weight (mg/100g body weight (SEM)) |

Mean Thymus Weight (mg (SEM)) |

Mean Corrected Thymus Weight (mg/100g body weight (SEM)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (HC) | 57 (3) | 15 (1) | 416 (17) | 111 (4) |

|

Increased complexity (IC) |

61(2) | 16 (1) | 377 (16) | 101 (4) |

| Exercise (X) | 64 (3) | 19 (1)# | 314 (19)# | 93 (5)* |

Corrected (gland weight (mg)/ body weight (g)) and uncorrected adrenal and thymus gland weights on day 11 of 98-dBA noise stress.

significantly different from both HC and IC groups, Tukey's HSD (p's < 0.05).

significantly different from HC, Tukey's HSD (p's < 0.05).

Corticosterone Response to Repeated Audiogenic Stress

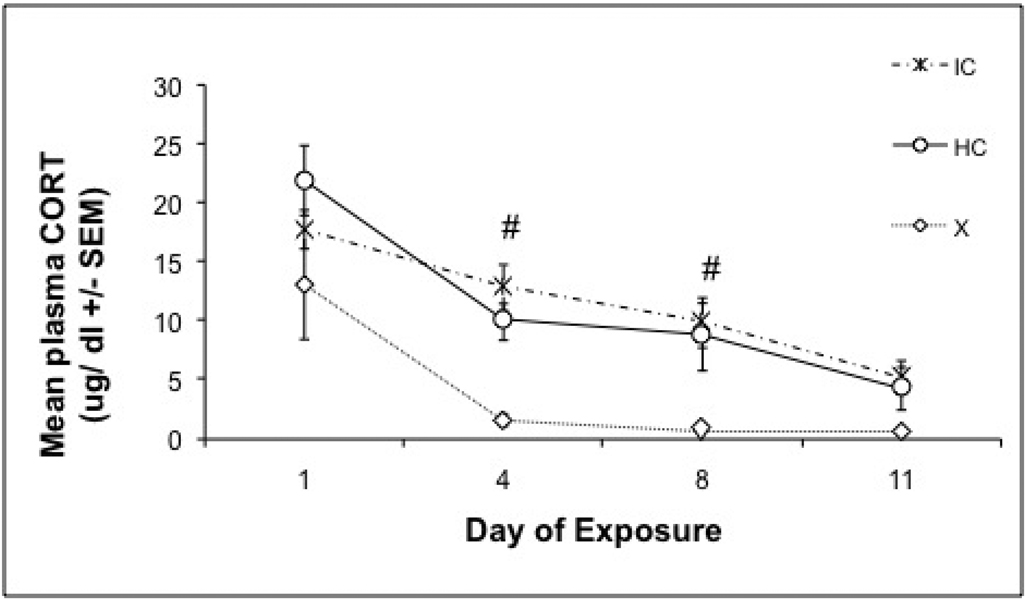

Corticosterone (CORT) was measured on noise exposure days 1, 4, 8 and 11, immediately following 30 min of noise stress. There were significant day (F 3,135 = 23.526, p =< 0.0001) and treatment (F 2, 45 = 11.344, p < 0.0001) effects without a significant interaction. One way ANOVA of CORT responses on individual days revealed significant differences between treatment groups on Days 4, 8, and 11. On Day 1, there were no significant differences between treatment groups. The exercised animals had a lower CORT response than both HC and IC animals on Days 4 and 8, (Tukey HSD p’s <0.032), with no significant difference between the exercised and HC or IC animals on Day 11 (Tukey HSD p=0.052), as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Plasma CORT Response to 98-dBA noise.

Mean corticosterone concentrations (+/− SEM) of the exercise, increased cage complexity, and control groups over the successive days (1, 4, 8, and 11) of repeated loud noise stress. Exercised animals had overall lower CORT responses than control and increased complexity animals, suggesting that habituation was enhanced in exercised animals. #: Home cage control and increased environmental complexity groups significantly different from exercise group, Tukey's HSD (p's < 0.05).

ACTH Response to Repeated Audiogenic Stress

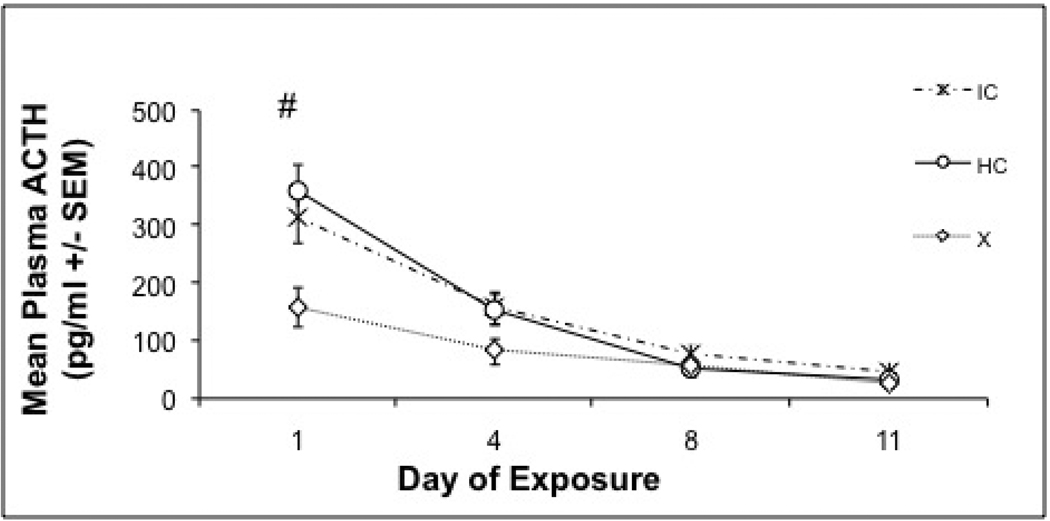

ACTH was measured on noise exposure days 1, 4, 8 and 11, immediately following 30 min of noise stress. Eight animals were excluded from this analysis due to insufficient quantities of plasma (<50 µl) collected on day 1 or 4 (4 HC, 2 IC and 2 X animals were excluded). There were significant day (F 3, 111 = 68.504, p < 0.0001) and treatment (F 2, 37 = 7.184, p = 0.002) effects, with a significant day X treatment interaction (F 6, 111 = 6.25, p =0.001. One way ANOVA on ACTH values on individual days revealed significant differences between groups on the first day only (F 2, 37 = 6.286, p = 0.004). Exercised animals had an overall lower acute ACTH response on Day 1 of noise exposure, compared to the other two groups, Tukey HSD (p’s ≤ 0.030), as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Plasma ACTH Response to 98-dBA noise.

Mean ACTH concentrations (+/− SEM) of the exercise, increased cage complexity, or control groups over the successive days (1, 4, 8, and 11) of repeated loud noise (98-dBA) stress. On day one, exercise animals had a reliably reduced ACTH response compared to increased cage complexity and control animals. Responses were statistically equivalent on each of the remaining sampling days. #: Exercise group significantly different from both control and increased cage complexity groups, Tukey's HSD (p'< 0.05).

In Situ Hybridization

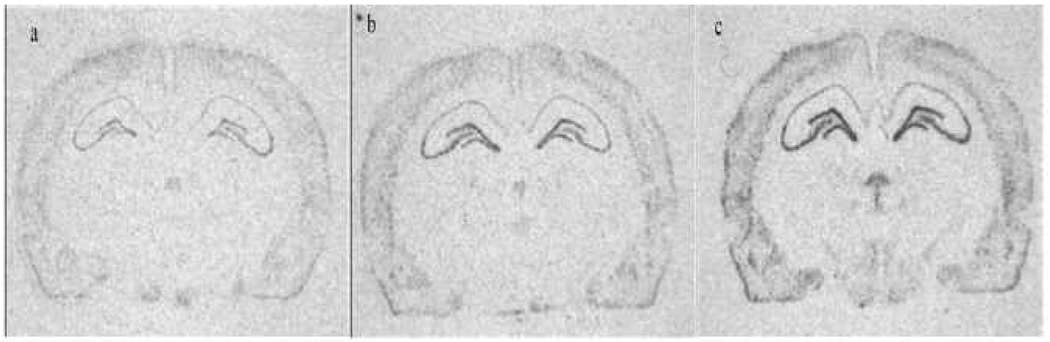

Of the various determinations of mRNA expression performed, BDNF and NGF were reliably regulated in both X and IC animals, although to a greater extent in X animals. Table 2 displays the mean relative CRH, CRH-R1, BDNF, NGF, NT3, trkB, and trkA mRNA expression levels (mean integrated optical density/100 +/− 1 SEM; presented as arbitrary units) in several brain regions collected from HC, IC, and X rats immediately following the last 30 min 98 dBA noise exposure. BDNF mRNA was significantly upregulated in the basolateral complex of the amygdala, hippocampal dentate gyrus, and CA3 regions in the X animals compared to the HC group, whereas expression levels in the IC group were often intermediate between the HC and X groups (see Figure 5). NGF mRNA was also upregulated in the hippocampal dentate gyrus mainly in the X group, but also to some extent in IC animals. No differences in CRH, CRH-R1, NT3, trkB or trkA mRNAs were detected under the current experimental conditions.

Table 2.

Mean relative CRH, CRH-R1, BDNF, NGF, NT3, trkB, and trkA mRNA expression levels

| Probe/Brain Region | Controls | Increased Complexity |

Exercise |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRH | |||

| PVN | 200 (15) | 277 (13) | 244 (19) |

| CRH R1 | |||

| MeA | 33 (6) | 39 (7) | 43(9) |

| BDNF | |||

| BLA* | 18 (3) | 19 (3) | 35 (7)ab |

| Dentate Gyrus* | 157 (28) | 242 (27)a | 498 (52)ab |

| CA1* | 35 (10) | 27 (9)a | 7 (2)a |

| CA3* | 95 (13) | 164 (18)a | 298 (37)ab |

| V. Hipp./ Sub. zone* | 16(2) | 18 (3) | 27 (3)a |

| NGF | |||

| Dentate Gyrus* | 47 (5) | 42 (5) | 68 (6)ab |

| CA1 # | 5 (1) | 7(1)a | 7(1)a |

| CA3 | 5 (1) | 6 (1) | 8 (1) |

| NT3 | |||

| Dentate Gyrus | 57 (6) | 49 (5) | 49 (4) |

| trkB | |||

| Dentate Gyrus | 92 (5) | 89 (7) | 98 (6) |

| CA1 | 55 (2) | 54 (3) | 59 (4) |

| CA3 | 31 (3) | 30 (3) | 32 (4) |

| trkA | |||

| CA1 | 6 (1) | 5 (1) | 5 (2) |

| CA3 | 11 (3) | 19 (5) | 17 (5) |

Mean relative CRH, CRH-R1, BDNF, NGF, NT3, trkB, and trkA mRNA expression levels (mean integrated grey values/100 +/− 1 SEM; presented as arbitrary units) measured in several brain regions from control, increased complexity, and exercise rats immediately following final (day 11) noise stress.

significant one way ANOVA, p < 0.05.

indicates a difference from controls,

indicates a significant difference from increased complexity animals, Tukey HSD, p < 0.05.

independent samples t-test in which X and IC values were grouped together, p < 0.05. (MeA- medial amygdala; BLA-basolateral amygdala; v. hipp- ventral hippocampus; sub. zone- subicular zone; PVN-paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus).

Figure 5. BDNF mRNA Photomicrographs.

Representative photomicrographs (taken from x-ray in situ films) of BDNF mRNA expression in the dorsal hippocampus of control (a), increased cage complexity (b) and exercise (c) animals. Note the increase in BDNF mRNA expression in increased cage complexity and exercise animals in different hippocampal subfields (CA3 and dentate gyrus).

In order to determine whether the differences noted above with regard to neurotrophin regulation in the X group were likely attributed to animals’ activity status, a separate group of animals were either house in the HC (n=10) or X ( n =7) condition for 6 weeks without further manipulation. After 6 weeks in these respective conditions tissue was analyzed for NGF mRNA. We found that six weeks of exercise, without stress exposure, resulted in a similar up-regulation of NGF (table 3) mRNAs compared to sedentary controls.

Table 3.

Mean NGF mRNA expression levels in hippocampi of exercise and sedentary control animals

| Probe/Brain Region | Sedentary | 6 Weeks Exercise |

|---|---|---|

| NGF | ||

| Dentate Gyrus # | 15 (3) | 37 (9)a |

| CA1 | 2 (1) | 6 (3) |

| CA3 | 1 (0.5) | 2 (1) |

Mean relative NGF mRNA expression levels (mean integrated grey values/100 +/− 1 SEM; presented as arbitrary units) measured in various hippocampal regions of animals given access to running wheels or living under sedentary conditions for 6 weeks prior to brain collection (data from separate study).

independent samples t-test, p < 0.05

indicates a difference from sedentary animals.

3. Discussion

This study compared the effects of 6 weeks of voluntary wheel running to 6 weeks of enhanced cage complexity to determine whether the enhancement of HPA axis response habituation when rats have free access to running wheels, as previously observed (Sasse et al., 2008), could be mainly attributed to an increase in physical activity, or to an increase in cage complexity provided by the presence of a running wheel. Although the magnitude of corticosterone response did not reliably differ between groups following the first loud noise exposure (Day 1), the free wheel-running rats displayed significantly lower corticosterone levels compared to both the isolated sedentary and increased environmental complexity rats on their respective fourth and eighth loud noise exposures, which is indicative of enhanced habituation, consistent with prior results from our laboratory (Sasse et al., 2008). The pattern of ACTH release in the present study, however, did not mirror the corticosterone pattern, in that the wheel-running rats displayed reliably lower levels of ACTH compared to the other two groups on the first loud noise exposure, but no group differences were observed by the fourth noise exposure. This result is in contrast to prior observations using a similar intensity of loud noise in which no differences in ACTH levels between isolated wheel runners and sedentary rats were obtained at any time during repeated loud noise exposures (Sasse et al., 2008). It is conceivable that these inconsistencies might reflect slight noise intensity or other technical differences between studies. These inconsistencies might also reflect a small effect of exercise on HPA axis responsiveness, this possibility is minimal, however, because we have consistently found voluntary physical activity to reduce either acute or repeated HPA axis responsiveness to audiogenic stress (Sasse et al. 2008; Campeau et al., 2010b). Furthermore, because we took blood samples at only one time point (immediately following 30 min noise exposure), it is possible that we might have missed group differences in HPA axis responsiveness during or after noise exposure. Importantly, the fact remains that the neuroendocrine response profile of the increased environmental complexity group is much more similar to that of the isolated sedentary group than the group given access to running wheels. Thus, the results strongly suggest that the increase in physical activity appears necessary to produce the effects on corticosterone habituation to repeated stress, as the increased cage complexity alone had no observable effects compared to the control isolated group, at least on the HPA axis responses to audiogenic stress.

That voluntary wheel running produced more physical activity than the increased cage complexity manipulation in this study is strongly suggested by the lower rate of weight gain displayed by animals given free access to running wheels. Whereas all groups had equivalent body weights at the beginning of the study, only exercise animals showed lower body weight gain within one week of beginning the experiment. There were also tendencies for the free-wheel running rats to display adrenal hyperplasia and thymic involution compared to the other groups. These physiological consequences of wheel running, as well as the pattern of wheel running, were similar to those described previously in male Sprague-Dawley rats (Afonso & Eikelboom, 2003; Droste et al., 2007; Sasse et al., 2008, Campeau et al., 2010b). Although the animals given a variety of objects in their cages might have been more active than controls (e.g. chewing on toys, shredding bedding material, or climbing on blocks and tunnels), this level of activity was not sufficient to induce any of the physiological changes observed in the rats that had free access to running wheels. All correlations between various measures of running distances and different indices of stress habituation or neurotrophic factor up-regulation were very weak, indicating that total activity level is a poor predictor of glucocorticoid response habituation, as observed previously (Sasse et al., 2008), as well as neurotrophic factor mRNA expression. These results imply that the effects of physical activity that were observed in this study do not increase linearly with physical activity, but may simply require a threshold activity level, as previously suggested (Greenwood et al., 2005; Sasse et al., et al., 2008), which was not attained by the rats in the increased environmental complexity provided in the current study.

To help determine the putative similarities of the two distinct manipulations used, the brains of isolated sedentary, increased cage complexity, and voluntary exercised rats were processed for multiple mRNA species previously shown to be regulated by some of these manipulations (see Introduction). An assessment of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) mRNA at the level of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN), one of the important signaling molecules affecting the release of ACTH at the level of the anterior pituitary, was not regulated by either physical activity or increased cage complexity in brains of habituated animals. Likewise, one of the CRH receptor subtypes mRNA (CRH-R1), often reported to increase following either acute or chronic stress (Luo et al., 1994; Makino et al., 1995; Rivest & Laflamme, 1995; Imaki et al., 1996), was not differentially regulated by these manipulations in the medial amygdaloid nucleus. The differential regulation of HPA axis response habituation observed to repeated loud noise stress is therefore unlikely to be uniquely mediated by these specific signaling molecules in the regions investigated.

On the other hand, the neurotrophins brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and nerve growth factor (NGF) were regulated in several hippocampal regions by both the increased environmental complexity and the wheel running conditions compared to the isolated sedentary group, however, nearly invariably the voluntary wheel running animals demonstrated significantly higher levels of BDNF and NGF mRNA. BDNF mRNA was additionally upregulated in the basolateral amygdaloid complex of free-wheel running animals compared to the other two groups. Neither the neurotrophin 3 (NT3) mRNA nor either of the tyrosine kinase receptor mRNAs assessed displayed reliable regulation. The finding that BDNF and NGF mRNAs were higher in both wheel running and increased cage complexity animals, but only wheel running reliably facilitated habituation to corticosterone release, and the fact that there was no correlation between mRNA levels and HPA axis response reduction additionally suggests that molecules other than these neurotrophins are responsible for the effects of wheel running on stress habituation. This is consistent with recent results dissociating the effects of wheel running and BDNF on the reduction of learned helplessness in stressed rats (Greenwood et al., al., 2007). Importantly, the reliable neurotrophin regulation observed in the increased cage complexity rats clearly indicates that this manipulation did produce significant effects on the expression of certain mRNAs in the brain, but this regulation was not sufficient to modulate HPA axis responsiveness. These results provide further support to the hypothesis that it is the physical activity component, and not simply the increased cage complexity provided by either the running wheels or the additional cage objects, that are likely responsible for the observed effects on HPA axis responses to repeated audiogenic stress.

In conclusion, increased physical activity, but not increased cage complexity alone, appears to be a sufficient condition in the enhanced hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis response habituation to repeated homotypic stress. Furthermore, increased cage complexity alone was sufficient to increase neurotrophic factor expression in several brain regions, however, physical activity increased neurotrophic factor mRNA expression to a greater extent. Although it is not clear at present whether other forms of cage enrichment, such as cage mates or larger living quarters, would produce similar effects in adult male rodents, the results of the current study imply that physical activity and other environmental manipulations should be considered separately for their putative effects on various brain functions.

4. Experimental procedure

Animal Procedures/ Environmental Manipulations

Forty-eight male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN, USA), two months of age and weighing approximately 200 g at arrival from the supplier were used in this study. Animals had ad libitum access to rat chow and water, and were kept under a 12-hr light/dark cycle, with lights on at 0700 hrs. Rats were allowed to acclimate to the animal colony for one week prior to any experimental manipulations. Seven days after arrival, the rats were single-housed in 46 × 25 × 22 cm clear polycarbonate cages with wire lids and divided into 3 groups matched for body weight (n=16/group). All animals were housed in the same colony room for the duration of the experiment (53 days). The exercise group (X) had voluntary access to running wheels in their home cages (described below); the increased cage complexity group (IC) was given 4 toys and bedding material that were exchanged every three days (described below); and the home cage control group (HC) was housed in the same standard cages without any of the previously mentioned manipulations. Each group remained under these conditions for the six weeks prior to and the eleven days of additional manipulations. All animals were weighed once per week.

Additionally, 17 animals were used to evaluate NGF expression in non- stressed neuronal tissue. Rats were allowed to acclimate to the animal colony for at least one week prior to any further manipulations. At least seven days after arrival, the rats were single-housed in 46 × 25 × 22 cm clear polycarbonate cages with wire lids and divided into 2 groups, exercise no stress (n=7) and home cage control no stress (n=10), identical to the corresponding conditions described above. All animals were housed in the same colony room for the duration of the experiment. These animals were sacrificed after 6 weeks in these conditions without receiving stress exposure.

All procedures were approved by The University of Colorado at Boulder Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, in conformation with NIH guidelines.

Voluntary Exercise

Animals in the X group had free 24-hr access to stainless steel running wheels (34.5 cm wheel diameter x 9.7 cm width, Nalge Nunc International, Rochester, NY, USA) attached to the lids of their home cage for the duration of the experiment (53 days). Running distances were monitored 24-hr/day, in ten min bins, by a computer with the VitalView Automated Data-Acquisition System (Mini-Mitter Inc., a division of Philips Respironics; Sunny River, OR, USA).

Total running distances (km) for each animal were calculated for each week of the experiment. Average daily running distances during weeks 6, 7, and 8 were calculated for individual animals. Pearson’s Correlation Coefficients were calculated using Microsoft Excel to determine correlations between individual running distances, neurotrophin mRNA levels, and glucocorticoid responses obtained to audiogenic stress (see below).

Increased environmental complexity Protocol

Much of the existing literature on environmental manipulations that show effects on neuronal function and or HPA axis activity report exchanging the environmental objects used 2–3 times weekly (Mainardi et al., 2010; Bakos et al., 2009; Morley-Fletcher et al., 2003). Therefore, animals in the IC group received 4 different objects at a time, and all objects were exchanged every three days. IC animals were subdivided into 2 groups of 8. The two subgroups received different sets of objects, and after three days the sets of objects were then switched between the two groups. To exchange toys, animals in their home cages were placed two at a time on a cart in the animal colony room. All objects were removed from both cages, thoroughly cleaned with antibacterial soap, rinsed, dried and placed back into the appropriate cages (or stored). Objects such as cloth towels and tissues were disposed of after one 3-day use, as were all objects that were chewed on extensively. The entire process took less than 4 min. Objects included plastic PVC tunnels (of three different shapes and dimensions), golf balls, wooden balls, wooden blocks of various shapes (i.e. rectangular, cylindrical, square, or triangular) sizes and colors, paper towels, plastic chew toys, cloth towels, sponge balls, sponges, tin foil, cotton balls, copper cylinders, plastic plumbing mushrooms, plastic spoons, cotton swabs, cardboard of various shapes and sizes, paper, and tissues. One of the 4 objects placed in the cage always included a tunnel (which all animals used to nest in). Animals received a different type of tunnel every 3 days, and only received the same tunnel every 9 days. Other than the tunnels, animals never received the same object within a 12 day period, nor did they ever receive the same combination of 4 objects.

Audiogenic Stress Apparatus and Procedures

Audiogenic stress was administered inside acoustic chambers, which consisted of ventilated double wooden (2.54 cm plywood board) chambers, with the outer chamber lined internally with 2.54 cm insulation (Celotex™). The internal dimensions of the inner box were 59.69 cm (w) x 38.10 cm (d) x 38.10 cm (h), which allowed placement of a polycarbonate rat home cage fitted with the running wheels. Each chamber had a single 15.24 cm x 22.86 cm Optimus speaker (#12–1769 - 120 W RMS) in the middle of the ceiling. Lighting was provided by a fluorescent lamp (15 W) located in the upper left corner of the chamber. Noise was produced by a General Radio (#1381) solid-state random-noise generator with the bandwidth set at 2 Hz-50 kHz. The output of the noise generator was amplified (Pyramid Studio Pro #PA-600X) and fed to the speakers. Noise intensity was measured daily before and after noise presentations by placing a Radio Shack Realistic Sound Level Meter (A scale; #33–2050) in the rat's home cage at several locations and taking an average of the different readings. The ambient/quiet noise level inside the chamber was approximately 60 decibels-A scale (dBA), and approximately 55 dBA in the rat colony.

Noise exposure began on week 7. All rats were pre-exposed to the acoustic chambers for 30 min/day for 3 days prior to the initial noise exposure. Animals in their individual home cages were carefully transported down a hallway on a cart, in groups of 8. In the experimental room, animals were individually placed into the acoustic chambers without the presentation of noise. Each group of 8 contained at least 2 animals from the X, HC, and IC conditions. After this acclimation period, at the beginning of the 7th week, the rats in their home cages were transported down the hallway and placed into the acoustic chambers and immediately exposed to 98 dBA white noise for 30 min, then removed from the chamber and taken back to the animal colony. This process was repeated for 11 consecutive days. All chamber pre-exposures and noise exposures occurred during the early phase of the light cycle (8:00-am- 12:30pm). Running wheels remained accessible during noise exposures, and all toys remained in animals’ home cages during noise exposures.

Blood Collection Procedure

Blood samples were collected on noise exposure days 1, 4, and 8 by a small tail nick, and from trunk blood immediately following decapitation on day 11. Immediately after the 1st, 4th, and 8th noise exposures, rats from each group were gently restrained using a clean towel. A small incision was then made in the lateral tail vein with the corner of a sterile razor blade. Approximately 400 µl of blood was collected from each animal, using non-heparinized hematocrit capillaries, and deposited into ice chilled 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes containing 15 µl EDTA (20 mg/ml). The whole procedure lasted less than 3 min from removal to return of the animal to its home cage. Blood collected via the lateral tail vein was centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 2 min, the plasma was then pipetted into 0.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes and stored at −80°C until assayed. Immediately following the final 30 min noise exposure on day 11, all animals were sacrificed by rapid decapitation and trunk blood was collected into ice chilled BD-Vacutainers coated with EDTA and were centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 10 min. Plasma was then pipetted into ice chilled 0.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes and kept at −80°C until assayed.

Tissue Collection

Upon sacrifice, brains were quickly dissected and frozen using chilled isopentane (−30°C) and stored at −80°C for later processing. Each animal’s adrenal glands and thymus were removed, kept on ice, and weighed within 4 hr of excision. Body weights were analyzed with repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Day as the repeated variable and environmental treatment (X/IC/HC) as a between-subjects variable. Gland weights were corrected according to body weight at the time of sacrifice and presented both as corrected and raw (uncorrected) weights. Gland weights were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA (environmental treatment: X/IC/HC), with treatment differences further explored using Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) multiple means post-hoc comparisons, with significance set at p = 0.05.

Corticosterone Enzyme Linked ImmunoSorbent Assays (ELISA)

The corticosterone (CORT) assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (kit #901-097 – AssayDesigns, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). All samples were measured simultaneously to reduce interassay variability. Optical density was then measured on a BioTek Elx808 microplate reader and CORT levels were calculated against a standard curve generated concurrently.

ACTH Radioimmunoassay (RIA)

The adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (kit # 27130- DiaSorin Inc., Stillwater, MN, USA). The sensitivity of the assay ranged from 0–1500 pg/ml. All samples were measured simultaneously to reduce interassay variability.

In situ hybridization histochemistry

The method for in situ hybridization histochemistry has previously been described (Masini et al., 2005; Day et al., 2008). Briefly, ten-micron sections were cut on a cryostat (Leica Model 1850, Wetzlar, Germany), thaw mounted onto polylysine subbed slides, and stored at −80°C until processed. Tissue was fixed in buffered 4% paraformaldehyde solution, acetylated in 0.1M triethanolamine with 0.25% acetic anhydride for 10 min, and dehydrated in graded alcohols. [35S]-UTP-labeled riboprobes against pan-BDNF (brain derived neurotrophic factor) mRNA (targeting exon 5; generously provided by Dr. S. Patterson, Univ. of Colorado, Boulder, CO, USA), trkB (tyrosine kinase receptor B) mRNA (generously provided by Dr. J. Herman, Univ. of Cincinnati, OH, USA), NT3 (neurotropin-3) mRNA (subcloned in our laboratory), trkA (tyrosine kinase receptor A) mRNA (subcloned in our laboratory), CRH (corticotropin releasing hormone; generously provided by Dr. R. Thompson, Univ. of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) mRNA, CRH-R1 (corticotropin releasing hormone receptor 1; generously provided by Dr. P. Sawchenko, The Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA) mRNA, and NGF (nerve growth factor) mRNA (subcloned in our laboratory) were made using standard transcription methods. All templates were fully sequenced, and control studies were performed on tissue sections pretreated with RNase (200 µg/ml at 37 °C for 1hr); this treatment prevented labeling. In addition, control tissue was hybridized with sense cRNA strands, which did not lead to significant hybridization to tissue (data not shown). Multiple in situ hybridizations were performed to analyze each of the mRNA riboprobes individually, but for a given probe and brain region, tissue from all animals was run concurrently. Tissue was hybridized overnight with one riboprobe diluted in hybridization buffer composed of 50% formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, 2x saline sodium citrate, 0.5 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 1x Denhardt’s solution, and 0.1 mg/ml yeast tRNA. The following day, tissue was treated with 200 µg/ml RNase A at 37 °C for 1 hr, washed in 0.1x saline sodium citrate at 65 °C for 1 hour, and dehydrated in graded alcohols. Tissue was then exposed to x-ray film (BioMax MR, Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA) for the appropriate amount of time (exposure time varied for each probe). X-ray films were then analyzed according to the procedure briefly described below. All animals were represented in each in situ to reduce the effects of variation between in situ’s.

The regions of interest analyzed included the hippocampal dorsal and ventral anterior dentate gyrus, CA1, CA3, and the anteroventral dentate gyrus/subicular zone, the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN), the basolateral complex of the amygdala (BLA), and the medial amygdala (MeA). The anterior dentate gyrus, CA1 and CA3 were analyzed for BDNF, trkB, and NGF from 2.76 to 3.96 mm posterior to bregma. The anterior dentate gyrus was analyzed for NT3 and trkA from 2.76 to 3.96 mm posterior to bregma. The anteroventral dentate gyrus/subicular zone was analyzed for BDNF from 5.28 to 5.64 mm posterior to bregma. The PVN was analyzed for CRH from 1.72 to 1.92 mm posterior to bregma. The BLA was analyzed for BDNF from 1.92 to 3.24 mm posterior to bregma. The MeA was analyzed for CRH-R1 from 1.92–2.52 mm posterior to bregma.

The method for semi-quantitative analysis of digitized images from x-ray films has been previously described (Day et al., 2008). Briefly, analyses were performed on digitized images from x-ray films in the linear range of grey values obtained with our acquisition system (Northern Light lightbox Model B 95, a SONY TV camera model XC-ST70 fitted with a Navitar 7000 zoom lens, connected to an LG3-01 frame grabber (Scion Corp., Frederick, MD, USA) inside a Dell Dimension 500, captured with Scion Image beta rel. version 4.02 for PC). Signal pixels in a region of interest were defined as being 3.5 standard deviations above the mean grey value of a cell poor area close to the region of interest. The number of pixels and the average pixel values above the set background were then computed for each region of interest and multiplied, giving an integrated mean grey value measure. An average of 3 to 10 measurements were made on different sections in each region of interest, and bilateral counts were made in all cases. Templates were used to measure each region of interest. These values were then averaged for each animal to obtain a mean integrated grey value for the region of interest in each animal.

Statistical Methods

Animals weights as well as values for plasma CORT and ACTH were statistically analyzed with repeated measures ANOVA with weekly weight or blood collection day as a repeated measure and group as a between-subjects variable (sampling days = within-subjects; environmental treatment= between-subjects). Group differences were evaluated using Tukey’s HSD multiple means comparisons, with significance set at p = 0.05 (environmental treatment: X-IC-HC). The average integrated mean grey values obtained via in situ hybridization for regions of interest were statistically analyzed using one-way ANOVA with group (X, IC, and HC) as a factor. Group differences were evaluated using Tukey’s HSD multiple means post-hoc comparisons, with significance set at p = 0.05 (environmental treatment: X-IC-HC). Due to their similar means, X and IC animals were grouped together for analysis of NGF in the CA1 region of the hippocampus, and an independent samples t-test was used to evaluate a possible difference from controls. Furthermore, unequal variances were observed in both the BDNF and NGF mRNA results. In order to abide by the assumptions of ANOVA, the individual data were transformed by taking the natural logarithm and re-computing the above ANOVA with the normalized data. Adrenal and thymus weights were analyzed using one way ANOVA with group (X, IC, and HC) as a factor. Group differences were evaluated using Tukey’s HSD multiple means post-hoc comparisons, with significance set at p = 0.05 (environmental treatment: X-IC-HC). Pearson correlation coefficients were computed to assess whether there were correlations between distances run in individual wheel running animals and various measures including plasma ACTH and CORT values, BDNF and NGF mRNA expression in the hippocampus, and thymus and adrenal gland weight. Meaningful correlations were taken to exceed r values of 0.70, which accounts for approximately 50 percent of the variance. SPSS version 13.0 for windows was used to perform statistical analyses (Chicago, Il, USA).

Research Highlights

Voluntary exercise and environmental complexity regulate BDNF in response to stress

Voluntary exercise and environmental complexity regulate NGF in response to stress

Only voluntary exercise facilitates quicker CORT habituation to repeated stress

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NINDS R03 NS054358 (S.C.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adlard PA, Cotman CW. Voluntary exercise protects against stress-induced decreases in brain-derived neurotrophic factor protein expression. Neuroscience. 2004;124:985–992. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afonso VM, Eikelboom R. Relationship between wheel running, feeding, drinking, and body weight in male rats. Physiol Behav. 2003;80:19–26. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00216-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arborelius L, Owens MJ, Plotsky PM, Nemeroff CB. The role of corticotropin-releasing factor in depression and anxiety disorders. J Endocrinol. 1999;160:1–12. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1600001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakos J, Hlavacova N, Rajman M, Ondicova K, Koros C, Kitraki E, Steinbusch HW, Jezova D. Enriched environment influences hormonal status and hippocampal brain derived neurotrophic factor in a sex dependent manner. Neuroscience. 2009;164:788–797. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Harris T. Stressors and aetiology of depression: a comment on Hallstrom, March 11 1987. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1987;76:221–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1987.tb02889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campeau S, Nyhuis TJ, Kryskow EM, Masini CV, Babb JA, Sasse SK, Greenwood BN, Fleshner M, Day HE. Stress rapidly increases alpha 1d adrenergic receptor mRNA in the rat dentate gyrus. Brain Res. 2010a;1323:109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.01.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campeau S, Nyhuis TJ, Sasse SK, Kryskow EM, Herlihy L, Masini CV, Babb JA, Greenwood BN, Fleshner M, Day HE. Hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis responses to low intensity stressors are reduced following voluntary wheel running in rats. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2010b doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2010.02007.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmandari E, Tsigos C, Chrousos G. Endocrinology of the stress response. Annu Rev Physiol. 2005;67:259–284. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.040403.120816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chodzko-Zajko WJ, Moore KA. Physical fitness and cognitive functioning in aging. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1994;22:195–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrousos GP, Gold PW. The concepts of stress and stress system disorders. Overview of physical and behavioral homeostasis. JAMA. 1992;267:1244–1252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirulli F, Alleva E. The NGF saga: from animal models of psychosocial stress to stress-related psychopathology. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2009;30:379–395. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day HE, Kryskow EM, Nyhuis TJ, Herlihy L, Campeau S. Conditioned fear inhibits c-fos mRNA expression in the central extended amygdala. Brain Res. 2008;1229:137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.06.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishman RK, Bunnell BN, Youngstedt SD, Yoo HS, Mougey EH, Meyerhoff JL. Activity wheel running blunts increased plasma adrenocorticotrophin (ACTH) after footshock and cage-switch stress. Physiol Behav. 1998;63:911–917. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(98)00017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Droste SK, Chandramohan Y, Hill LE, Linthorst AC, Reul JM. Voluntary exercise impacts on the rat hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis mainly at the adrenal level. Neuroendocrinology. 2007;86:26–37. doi: 10.1159/000104770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn AL, Trivedi MH, O’Neal HA. Physical activity dose-response effects on outcomes of depression and anxiety. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:S587–S597. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200106001-00027. discussion 609–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foreman PJ, Taglialatela G, Angelucci L, Turner CP, Perez-Polo JR. Nerve growth factor and p75NGFR factor receptor mRNA change in rodent CNS following stress activation of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. J Neurosci Res. 1993;36:10–18. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490360103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood BN, Foley TE, Burhans D, Maier SF, Fleshner M. The consequences of uncontrollable stress are sensitive to duration of prior wheel running. Brain Res. 2005;1033:164–178. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood BN, Fleshner M. Exercise, learned helplessness, and the stress-resistant brain. Neuromolecular Med. 2008;10:81–98. doi: 10.1007/s12017-008-8029-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood BN, Strong PV, Foley TE, Thompson RS, Fleshner M. Learned helplessness is independent of levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2007;144:1193–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grissom N, Bhatnagar S. Habituation to repeated stress: get used to it. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2009;92:215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Davila J, Brown G, Ellicott A, Gitlin M. Psychiatric history and stress: predictors of severity of unipolar depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 1992;101:45–52. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaki T, Naruse M, Harada S, Chikada N, Imaki J, Onodera H, Demura H, Vale W. Corticotropin-releasing factor up-regulates its own receptor mRNA in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1996;38:166–170. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(96)00011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jokinen J, Nordstrom P. HPA axis hyperactivity as suicide predictor in elderly mood disorder inpatients. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:1387–1393. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruk J, Aboul-Enein HY. Physical activity in the prevention of cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2006;7:11–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Kiss A, Makara G, Lolait SJ, Aguilera G. Stress-specific regulation of corticotropin releasing hormone receptor expression in the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei of the hypothalamus in the rat. J Neuroendocrinol. 1994;6:689–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1994.tb00636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainardi M, Landi S, Gianfranceschi L, Baldini S, De Pasquale R, Berardi N, Maffei L, Caleo M. Environmental enrichment potentiates thalamocortical transmission and plasticity in the adult rat visual cortex. Epub. 2010 Aug; doi: 10.1002/jnr.22461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino S, Schulkin J, Smith MA, Pacak K, Palkovits M, Gold PW. Regulation of corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor messenger ribonucleic acid in the rat brain and pituitary by glucocorticoids and stress. Endocrinology. 1995;136:4517–4525. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.10.7664672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manson JE, Nathan DM, Krolewski AS, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Hennekens CH. A prospective study of exercise and incidence of diabetes among US male physicians. JAMA. 1992;268:63–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marti O, Armario A. Anterior pituitary response to stress: time-related changes and adaptation. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1998;16:241–260. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(98)00030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masini CV, Sauer S, Campeau S. Ferret odor as a processive stress model in rats: neurochemical, behavioral, and endocrine evidence. Behav Neurosci. 2005;119:280–292. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.1.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Allostasis and allostatic load: implications for neuropsychopharmacology. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22:108–124. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00129-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraska A, Fleshner M. Voluntary physical activity prevents stress-induced behavioral depression and anti-KLH antibody suppression. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2001;281:R484–R489. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.2.R484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley-Fletcher S, Rea M, Maccari S, Laviola G. Environmental enrichment during adolescence reverses the effects of prenatal stress on play behaviour and HPA axis reactivity in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:3367–3374. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2003.03070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble EG, Moraska A, Mazzeo RS, Roth DA, Olsson MC, Moore RL, Fleshner M. Differential expression of stress proteins in rat myocardium after free wheel or treadmill run training. J. Appl. Physiol. 1999;86:1696–1701. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.5.1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oguma Y, Shinoda-Tagawa T. Physical activity decreases cardiovascular disease risk in women: review and meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26:407–418. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliff HS, Berchtold NC, Isackson P, Cotman CW. Exercise-induced regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) transcripts in the rat hippocampus. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1998;61:147–153. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00222-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternac A, Talajic M. The effects of stress, emotion, and behavior on the heart. Methods Achiev Exp Pathol. 1991;15:47–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietropaolo S, Feldon J, Alleva E, Cirulli F, Yee BK. The role of voluntary exercise in enriched rearing: a behavioral analysis. Behav Neurosci. 2006;120:787–803. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.4.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivest S, Laflamme N. Neuronal activity and neuropeptide gene transcription in the brains of immune-challenged rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 1995;7:501–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1995.tb00788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig MR, Bennett EL. Effects of environmental enrichment or impoverishment on learning and on brain bvalues in rodents. In: Oliverio A, editor. Genetics, Environment and Intelligence. Amsterdam: Elsevier, North Holland; 1977. pp. 163–196. [Google Scholar]

- Russo-Neustadt A, Ha T, Ramirez R, Kesslak JP. Physical activity-antidepressant treatment comibnation: impact on brain-derived neurotrophic factor and behavior in an animal model. Behav. Brain Res. 2001;120:87–95. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00364-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky RM. Why stress is bad for your brain. Science. 1996;273:749–750. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5276.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasse SK, Greenwood BN, Masini CV, Nyhuis TJ, Fleshner M, Day HE, Campeau S. Chronic voluntary wheel running facilitates corticosterone response habituation to repeated audiogenic stress exposure in male rats. Stress. 2008;11:425–437. doi: 10.1080/10253890801887453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, Makino S, Kvetnansky R, Post RM. Effects of stress on neurotrophic factor expression in the rat brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;771:234–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb44684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratakis CA, Chrousos GP. Neuroendocrinology and pathophysiology of the stress system. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;771:1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb44666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsigos C, Chrousos GP. Physiology of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in health and dysregulation in psychiatric and autoimmune disorders. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1994;23:451–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueyama T, Kawai Y, Nemoto K, Sekimoto M, Tone S, Senba E. Immobilization stress reduced the expression of neurotrophins and their receptors in the rat brain. Neurosci Res. 1997;28:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(97)00030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanitallie TB. Stress: a risk factor for serious illness. Metabolism. 2002;51:40–45. doi: 10.1053/meta.2002.33191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkmar FR, Greenough WT. Rearing complexity affects branching of dendrites in the visual cortex of the rat. Science. 1972;176:1445–1447. doi: 10.1126/science.176.4042.1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Walker M. Changes in physical activity, mortality, and incidence of coronary heart disease in older men. Lancet. 1998;351:1603–1608. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)12355-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]