Summary

The structural and kinetic effects of amprenavir (APV), a clinical HIV protease (PR) inhibitor, were analyzed with wild type enzyme and mutants with single substitutions of V32I, I50V, I54V, I54M, I84V and L90M that are common in drug resistance. Crystal structures of the APV complexes at resolutions of 1.02 to 1.85 Å reveal the structural changes due to the mutations. Substitution of the larger side chains in PRV32I, PRI54M and PRL90M resulted in formation of new hydrophobic contacts with flap residues, residues 79 and 80, and Asp25, respectively. Mutation to smaller side chains eliminated hydrophobic interactions in the PRI50V and PRI54V structures. The PRI84V-APV complex had lost hydrophobic contacts with APV, the PRV32I-APV complex showed increased hydrophobic contacts within the hydrophobic cluster, and the PRI50V complex had weaker polar and hydrophobic interactions with APV. The observed structural changes in PRI84V-APV, PRV32I-APV and PRI50V-APV were related to their reduced inhibition by APV of 6-, 10- and 30-fold, respectively, relative to wild type PR. The APV complexes were compared with the corresponding saquinavir (SQV) complexes. The PR dimers had distinct rearrangements of the flaps and 80’s loops that adapt to the different P1′ groups of the inhibitors while maintaining contacts within the hydrophobic cluster. These small changes in the loops and weak internal interactions produce the different patterns of resistant mutations for the two drugs.

Keywords: X-ray crystallography, enzyme inhibition, aspartic protease, HIV/AIDS, conformational change

INTRODUCTION

Currently, about 33 million people worldwide are estimated to be infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in the AIDS pandemic [1]. The virus cannot be fully eradicated despite the effectiveness of highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) [2]. Furthermore, development of vaccines has been extremely challenging [3]. HAART uses more than 20 different drugs, including inhibitors of the HIV-1 enzymes, reverse transcriptase (RT), protease (PR) and integrase, as well as inhibitors of cell entry and fusion. The major challenge limiting current therapy is the rapid evolution of drug resistance due to the high mutation rate caused by the absence of a proof-reading function in HIV RT [4].

HIV-1 PR is the enzyme responsible for the cleavage of the viral Gag and Gag-Pol polyproteins into mature, functional proteins. PR is a valuable drug target since inhibition of PR activity results in immature noninfectious virions [5–6]. PR is a dimeric aspartic protease composed of residues 1-99 and 1′-99′. The conserved catalytic triplets, Asp25-Thr26-Gly27, from both subunits provide the key elements for formation of the enzyme active site. Inhibitors and substrates bind in the active site cavity between the catalytic residues and the flexible flaps comprising residues 45-55 and 45′-55′ [7].

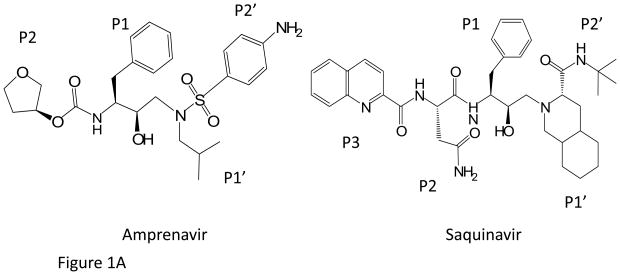

Amprenavir (APV) was the first HIV-1 PR inhibitor (PI) to include a sulfonamide group (Fig 1A). Similar to other PIs, APV contains a hydroxyethylamine core that mimics the transition state of the enzyme. Unlike the first generation PIs, such as saquinavir (SQV), APV was designed to maximize hydrophilic interactions with PR [8]. The sulfonamide group increases the water solubility of APV (60 μg/mL) compared to SQV (36 μg/mL) [9]. The crystal structures of PR complexes with APV [8, 10] and SQV [11–12] demonstrated the critical PR-PI interactions.

Figure 1.

(a) The chemical structures of amprenavir (APV) and saquinavir (SQV).

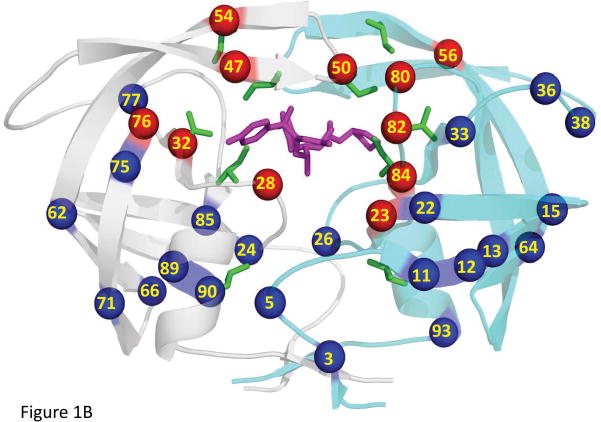

(b) Structure of HIV-1 PR dimer with the sites of mutation Val32, Ile50, Ile54, Ile84 and Leu90 indicated by green sticks for side chain atoms in both subunits. Amino acids are labeled in one subunit only. APV is shown in magenta sticks. The amino acids in the inner hydrophobic cluster are indicated by numbered red spheres, and the amino acids in the outer hydrophobic cluster are shown as blue spheres.

HIV-1 resistance to PIs arises mainly from accumulation of PR mutations. Conservative mutations of hydrophobic residues are common in PI resistance, including V32I, I50V, I54V/M, I84V and L90M that are the focus of this study [13]. The location of these mutations in the PR dimer structure is shown in Figure 1B. Multi-drug-resistant mutation V32I, which alters a residue in the active site cavity, appears in about 20% of patients treated with APV[14] and is associated with high levels of drug resistance to lopinavir (LPV)/ritonavir [13]. Ile50 and Ile54 are located in the flap region, which is important for catalysis and binding of substrates or inhibitors [8, 15]. Mutations of flap residues can alter the protein stability or binding of inhibitors [15–18]. PR with mutation I50V shows 9-fold worse inhibition by DRV relative to wild type enzyme [19], and 50- and 20- fold decreased inhibition by indinavir (IDV) and SQV [17–18]. Unlike Ile50, Ile54 does not directly interact with APV, but mutations of Ile54 are frequent in APV resistance and the I54M mutation causes 6-fold increased IC50 [20]. Mutation I54V appears in resistance to IDV, LPV, nelfinavir (NFV) and SQV [13]. I54V in combination with other mutations, especially V82A [21–22], decreases the susceptibility to PI therapy [18]. I84V, which is located in the active site cavity, significantly reduces drug susceptibility to APV [23]. L90M is commonly found during PI treatment [14] and is resistant to all currently used PIs, with major effects on NFV and SQV [13].

Mutations of hydrophobic residues are found in more than half of drug resistant mutants [13, 24] and several of these mutations show altered PR stability [17, 25]. Hydrophobic interactions play an important role in protein stability. Aliphatic groups reportedly contribute about 70% of the hydrophobic interactions in proteins [26]. Removing a methyl group in the protein hydrophobic core affects protein folding and decreases the protein stability in mutant proteins [27]. In HIV PR, two clusters of methyl groups have been identified; one inner cluster surrounding the active site cavity and the second cluster in an outer hydrophobic core, as shown in Figure 1B [24]. Drug resistant mutations V32I, I50V, I54V/M, and I84V belong to the inner cluster around the active site, while L90M is in the outer cluster.

In order to establish a better understanding of the mechanism of resistance to APV, atomic and high resolution crystal structures have been determined of APV complexes with wild type PR and its mutants containing single substitutions of Val32, Ile50, Ile54, Ile84 and Leu90. HIV-1 PR mutations can have distinct effects on the binding of different inhibitors. Therefore, the structural effects of APV and SQV were compared for wild type PR and mutants PRI50V, PRI54M, and PRI54V complexes, using previously reported SQV complexes [12, 18]. Exploring the changes in PR due to binding of two different inhibitors will give insight into the mechanisms of resistance and help in the design of new inhibitors.

RESULTS

APV Inhibition of HIV-1 PR and Mutants

The kinetic parameters and inhibition constants of APV for wild-type PR and the drug-resistant mutants PRV32I, PRI50V, PRI54M, PRI54V, PRI84V and PRL90M are shown in Table I. The lowest catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) values were seen for PRV32I and PRI50V with 30% and 10% of the wild-type PR value, respectively. The PRL90M showed a surprisingly high 11-fold increase in the catalytic efficiency, while the other mutants were similar to the wild type. The kcat/Km values for PRL90M appear to depend on the substrate, however, since only a modest 3-fold increase relative to wild type PR was observed using a different substrate with sequence derived from the MA/CA rather than the p2/NC cleavage site [19]. The six mutants and wild-type PR were assayed for inhibition by APV (Table I). APV showed sub-nanomolar inhibition with Ki of 0.16 nM for wild-type PR and PRL90M. PRI54M and PRI54V showed modestly increased (3-fold) relative Ki values. The largest increases in Ki of 6-, 10- and 30-fold were observed for PRI84V, PRV32I and PRI50V, respectively, relative to wild-type PR. The substantially decreased inhibition of PRV32I and PRI50V suggested the loss of interactions with APV.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters for substrate hydrolysis and inhibition of amprenavir.

| Km(μM) | kcat(/min) | kcat/Km(μM/min) | Relative kcat/Km | Ki (nM) | Relative Ki | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT* | 30±5 | 190±20 | 6.5±1.3 | 1.0 | 0.15±0.04 | 1 |

| V32I | 65±6 | 120±10 | 1.8±0.2 | 0.3 | 1.5±0.2 | 10 |

| I50V* | 109±8 | 68±5 | 0.6±0.03 | 0.1 | 4.5±0.6 | 30 |

| I54M* | 41±5 | 300±40 | 7.3±0.8 | 1.1 | 0.50±0.06 | 3 |

| I54V* | 43±6 | 130±20 | 3.1±0.9 | 0.5 | 0.41±0.05 | 3 |

| I84V | 73±6 | 320±30 | 4.4±0.5 | 0.7 | 0.9±0.2 | 6 |

| L90M | 13±2 | 950±120 | 73±13 | 11.2 | 0.16±0.01 | 1 |

Km and kcat values from [18]

Error in kcat/Km is calculated as (A/B) +/− (1/B2)(square root(B2a2 +A2b2)), where A is kcat, a is kcat error, B is Km, and b is error in Km.

Crystal Structures of APV Complexes

The crystal structures of PR and drug resistant mutants PRV32I, PRI50V, PRI54M, PRI54V, PRI84V and PRL90M were determined in their complexes with APV at resolutions of 1.02 to 1.85 Å to investigate the structural changes. The crystallographic data are summarized in Table II. All structures were determined in space group P21212. The asymmetric unit contains one PR dimer of residues 1-99 and 1′-99′ as well as APV. The lowest resolution structure of PRI84V was refined to an R-factor of 0.20 with isotropic B-factors and solvent molecules. The other structures were refined at 1.50–1.02 Å resolution to R-factors of 0.12–0.16, including anisotropic B-factors, hydrogen atoms and solvent molecules. Wild-type PR had the highest resolution and lowest R-factor, concomitant with the lowest average B-factors for the protein and inhibitor atoms.

Table 2.

Crystallographic Data Collection and Refinement Statistics

| APV complex | PR | PRV32I | PRI50V | PRI54M | PRI54V | PRI84V* | PRL90M |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Space group | P21212 | P21212 | P21212 | P21212 | P21212 | P21212 | P21212 |

| Unit cell dimensions: (Å) | |||||||

| a | 58.11 | 57.77 | 57.95 | 58.12 | 57.50 | 59.51 | 57.94 |

| b | 85.97 | 86.13 | 86.01 | 85.91 | 86.00 | 86.88 | 85.91 |

| c | 46.42 | 46.28 | 46.21 | 46.10 | 45.95 | 45.44 | 46.10 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50–1.02 | 50–1.20 | 50–1.29 | 50–1.16 | 50–1.50 | 50–1.85 | 50–1.35 |

| Unique reflections | 113,227 | 66,626 | 55,569 | 73,638 | 37,010 | 18,138 | 50,443 |

| b Rmerge (%) overalla | 5.7 (38.2) | 8.1 (44.2) | 7.0 (40.2) | 7.2 (35.7) | 6.0 (46.2) | 9.7 (34.5) | 5.5 (46.2) |

| I/σ(I) overalla | 15.3 (2.6) | 11.3 (2.5) | 15.2 (2.3) | 20.1 (2.1) | 16.8 (2.4) | 15.8 (5.8) | 17.9 (2.5) |

| Completeness (%) overalla | 95.8 (65.0) | 91.6 (62.7) | 93.9 (70.4) | 91.8 (58.9) | 99.7 (99.2) | 93.2 (76.6) | 97.8 (97.3) |

| Data range for refinement (Å) | 10–1.02 | 10–1.20 | 10–1.29 | 10–1.16 | 10–1.50 | 10–1.85 | 10–1.35 |

| c R (%) | 12.4 | 16.4 | 15.5 | 15.4 | 14.9 | 19.9 | 14.3 |

| d Rfree (%) | 14.2 | 20.1 | 19.3 | 18.8 | 19.7 | 23.6 | 19.9 |

| No. of solvent atoms (total occupancies) | 292 (207.3) | 151 (129.8) | 177 (143.6) | 242 (221.5) | 152 (128.5) | 84 (84) | 211 (202.5) |

| RMS deviation from ideality | |||||||

| Bonds (Å) | 0.017 | 0.013 | 0.012 | 0.016 | 0.010 | 0.014 | 0.012 |

| Angle distance (Å) | 0.036 | 0.031 | 0.030 | 0.033 | 0.029 | 1.546 (Degree) | 0.030 |

| Average B-factors (Å2) | |||||||

| Main-chain atoms | 10.8 | 16.0 | 14.4 | 14.2 | 23.2 | 25.6 | 20.3 |

| Side-chain atoms | 14.8 | 21.4 | 20.7 | 20.8 | 28.8 | 28.3 | 23.6 |

| Inhibitor | 10.5 | 16.9 | 17.1 | 17.8 | 28.5 | 23.7 | 16.1 |

| Solvent | 20.8 | 25.6 | 24.3 | 36.1 | 47.0 | 49.5 | 39.9 |

| DPI | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.05 |

| Relative occupancy of APV | 0.7/0.3 | - | 0.6/0.4 | - | - | - | - |

| RMS deviation from PR (Å) | - | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.33 | 0.26 | 0.38 | 0.19 |

| RMS deviation from PR-SQV (Å) | 0.87 | - | 0.29 | 0.36 | 0.32 | 0.36 | - |

Refined using REFMAC 5.0, others were refined with SHELX-97

Values in parentheses are given for the highest resolution shell.

Rmerge = Σhkl|Ihkl−〈Ihkl〉|/ΣhklIhkl.

R = Σ|Fobs−Fcal|/ΣFobs.

Rfree = Σtest(|Fobs|−|Fcal|)2/Σtest|Fobs|2.

Because of the high resolution of the diffraction data, all structures except for PRI84V-APV, were modeled with more than 150 water molecules, ions, and other small molecules from the crystallization solutions, including many with partial occupancy (Table II). The solvent molecules were identified by the shape and intensity of the electron density and the potential for interactions with other molecules. The non-water solvent molecules were: a single sodium ion, three chloride ions, two partial glycerol molecules in PRWT-APV; one sodium ion, three chloride ions in PRV32I-APV; three sodium ions, seven chloride ions, two partial acetate ions in PRI50V-APV; one sodium ions, three chloride, two partial acetate ions in PRI54M-APV; 19 iodide ions in PRI54V-APV; 33 iodide ions in PRI84V-APV; and 19 iodide ions in PRL90M-APV. Many iodide ions have partial occupancy, however, they were identified by the high peaks in electron density maps, abnormal B factors, and contact distances of 3.4 to 3.8 Ǻ to nitrogen atoms.

Alternative conformations were modeled for residues in all crystal structures. Alternate conformations were modeled for a total of 48, 13, 28, 11, 1, 8 residues in the PRWT-APV, PRV32I-APV, PRI50V-APV, PRI54M-APV, PRI54V-APV, PRI84V-APV, and PRL90M-APV structures, respectively. APV was observed in two alternate orientations related by a rotation of 180° in the complexes with PRWT and PRI50V with relative occupancies of 0.7/0.3 and 0.6/0.4, respectively. The highest resolution structure, PRWT-APV, showed the most alternate conformations for main chain and side chain residues. Several residues in the active site cavity showed two alternate conformations and were refined with the same relative occupancies as for APV. Surface residues with longer flexible side chains, such as Trp6, Arg8, Glu21, Glu34, Ser37, Lys45, Met46, Lys55, Arg57, Gln61, and Glu65 were refined with alternate conformations. Also, some internal hydrophobic residues, such as Ile64, Leu97, showed a second conformation for the side chain. At the other extreme, the lowest resolution structure of PRI84V-APV showed only one residue, Leu97, with an alternate side chain conformation. In all the structures, the two catalytic Asp25 residues showed negative difference density around the carboxylate oxygens. This phenomenon might be caused by radiation damage in the carboxylate side chains, especially due to their location at the active site, as described in [28].

The accuracy in the atomic positions was evaluated by the diffraction-data precision indicator (DPI), which is calculated in SFCHECK from the resolution, R-factor, completeness and observed data [29]. The highest resolution structure of PRWT-APV had the lowest DPI value of 0.02 Å, while the lowest resolution structure of PRI84V-APV had the highest DPI value of 0.13 Å (Table II). We estimate that significant differences in interatomic distances should be at least 3-fold larger than the DPI value [7]. Hence, structural changes of >0.06 Å are significant for PRWT-APV and >0.4 Ǻ for PRI84V-APV at the two extremes of resolution. The quality of the crystal structures is illustrated by the 2Fo-Fc electron density maps for the mutated residues (Fig. S1). The mutated residues had single conformations, except for the side chains of Met54, Val54 and Met90 in one subunit that were refined with relative occupancies of 0.6/0.4, 0.7/0.3 and 0.5/0.5, respectively. Overall, the mutants and wild type enzyme had very similar structures, probably because they shared the same crystallographic unit cell. The PRI54M, PRI54V, and PRI84V complexes had RMS deviations for the Cα atoms ranging from 0.26 Å to 0.38 Å compared to the wild type structure. The structures of PRV32I, PRI50V, and PRL90M were more similar to the wild-type PR with RMS deviations of 0.15–0.19 Å for the main chain atoms.

HIV-1 Protease Interactions with APV and Influence of Alternate Conformations

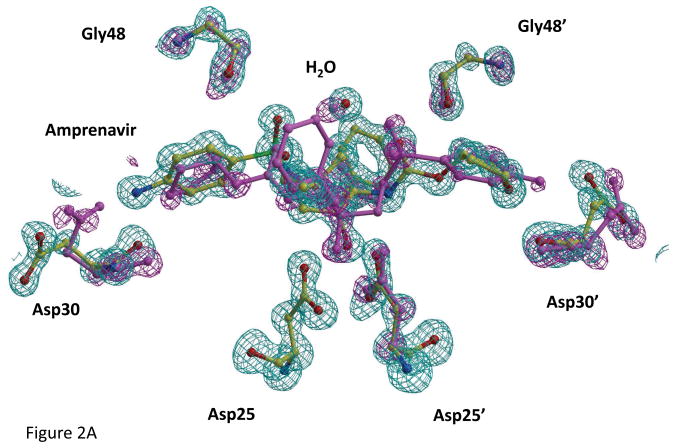

The atomic resolution crystal structure of PRWT-APV was refined with two differently populated conformations for the inhibitor and several residues forming the binding site with relative occupancies of 0.7/0.3 (Fig 2A). Residues Arg8, Asp30, Val32, Lys45, Gly48, Ile50, and Pro81 showed alternate conformations in both subunits, and Asp25′ had two alternate conformations for the side chain. Alternate conformations were also refined for the main chain of residues 24′, 29′, 30, 30′, 31, 31′, 48, 48′, 79′ and 80′ around the inhibitor binding site. Moreover, the conserved water molecule between the flaps and inhibitor showed two alternate positions. Similar, although less extensive, disorder in the inhibitor binding site has been observed in other atomic resolution crystal structures of this enzyme [12, 30]. In fact, the highest resolution structure reported to date (0.84 Å) of PRV32I with DRV comprised two distinct populations for the entire dimer with inhibitor and one conformer contained an unusual second binding site for DRV [30]. Moreover, a similar asymmetric arrangement of Asp25/25′ with a single conformation for Asp25 and two conformations for Asp25′ was observed in the crystal structure of PRWT-GRL0255A [31]. Only single conformations were apparent for APV in the mutant protease structures with the exception of PRI50V. However, the mutant structures were refined with lower resolution data where alternate conformations may be less clearly resolved than for the PRWT-APV structure.

Figure 2.

Inhibitor Binding Site in PRWT-APV.

a) APV and PR residues in the binding site with alternate conformations. Omit maps for major (green) and minor (magenta) conformations of APV, interacting PR residues Asp25, Gly48 and Asp30 from both subunits, and the conserved flap water are contoured at a level of 3.5 σ.

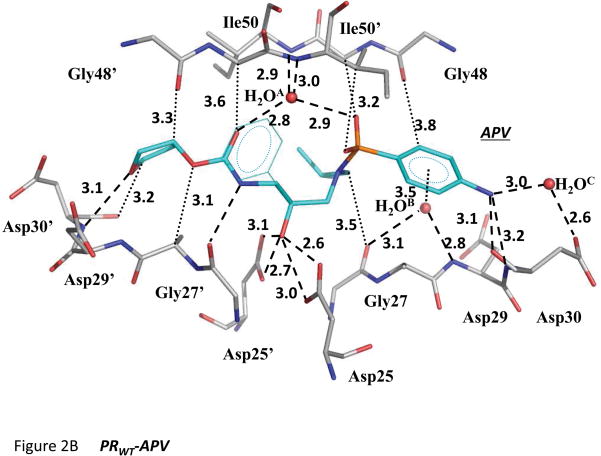

b) Hydrogen bond, C-H···O and H2O···π interactions between PR (gray) and APV (cyan). Hydrogen bond interactions are indicated by dashed lines. C-H···O and H2O···π interactions are indicated by dotted lines.

APV interactions with PRWT were analyzed in terms of the hydrogen bond, C-H···O and H2O···π interactions, as described for the PRV32I complex with DRV [30]. The polar interactions of the major conformation of APV with PRWT are illustrated in Figure 2B. The central hydroxyl group of APV forms strong hydrogen bond interactions with the carboxylate oxygens of the catalytic residues Asp25 and Asp25′. APV formed four direct hydrogen bonds with the main chain amide of Asp30′, the carbonyl oxygen of Gly27′, and the amide and carbonyl oxygen of Asp30. Water molecules make important contributions to the binding site. The flap water molecule (H2OA in Fig. 2B), which is conserved in almost all PR-inhibitor complexes, formed a tetrahedral arrangement of hydrogen bonds connecting the amide nitrogen atoms of Ile50/50′ in the flap region with the sulfonamide oxygen and the carbamate carbonyl oxygen of APV. The second conserved water (H2OB) bridged APV and the PR main chain by hydrogen bonds to the carbonyl of Gly27 and the amide of Asp29 and a H2O···π interaction with the aniline group of APV. The interactions of H2OB are conserved in PR complexes with darunavir and antiviral inhibitors based on the same chemical scaffold [31–32]. The third water, H2OC, which is conserved in these APV complexes and in DRV complexes, mediated hydrogen bond interactions between the carboxylate of Asp30 and aniline NH2 of APV. Also, several C-H···O interactions link the PR main chain to APV: the carbonyl oxygens of Gly48′ and Asp30′ interact with the tetrahydrafuran (THF) moiety, Gly27 carbonyl oxygen with isopropyl group, Gly48 carbonyl oxygen with aniline ring, the sulfonamide oxygens of APV to Gly49 and Ile50′, APV carbonyl oxygen with Gly49′ and APV oxygen to Gly27′ (Fig. 2). The C-H···O interactions formed by the PR amides and carbonyl oxygens mimic the conserved hydrogen bond interactions observed in PR complexes with peptide analogs [33–34].

The minor APV conformation refined with 0.3 relative occupancy lies in the opposite orientation to the major conformation and interacts with the opposite subunits of the PR dimer. The minor conformation of APV retained almost identical hydrogen bond, C-H···O and H2O···π interactions to major conformation, with the following exceptions (Table S1). The hydrogen bond between the aniline nitrogen of APV and the carbonyl oxygen of Asp30 was lost in the minor APV conformation (distance increased to 3.6 Ǻ). The water mediated interaction between the APV aniline nitrogen and the carboxylate group of Asp30 was replaced by a weak direct hydrogen bond (distance of 3.4 Ǻ). The hydrogen bond of the THF oxygen with the amide of Asp30′ was lost in the minor APV conformation (distance increased to 3.7 Ǻ). Instead, the THF oxygen of APV formed a new interaction with the carboxylate group in the minor conformation of Asp30. The water interaction with the amide of Ile50′ was weakened (distance of 3.5 Ǻ). The C-H···O interaction between the carbonyl oxygen of APV and the Cα of Gly49 was lost in the minor conformation of APV. Some of these differences are likely to reflect the lower occupancy and greater positional error in the minor conformation. Variability in the interactions of Asp30/30′ due to flexibility of the side chains has been observed in other PR complexes [19]. Overall, the minor conformation of APV showed one less hydrogen bond, one less C-H···O interaction, and weaker interactions than the major conformation had with PR.

Effects of Mutations on PR Structure and Interactions with APV

The structures of the mutants and wild type PR complexes with APV were compared in order to identify any significant changes. Overall, the polar interactions between APV and PR were well maintained in the mutant complexes. In these seven complexes the distances between non-hydrogen atoms were observed to be in the range of 2.3 to 3.3 Ǻ for hydrogen bonds and 3.2 to 3.8 Ǻ for C-H···O interactions (Tables S1, S2). The estimated error in atomic position is about 0.05 Ǻ in structures at 1.0–1.2 Ǻ resolution compared to the higher estimated errors of 0.10–0.15 Ǻ in structures at 1.5–1.8 Ǻ resolution [7], such as the complexes of PRI54V-APV and PRI84V-APV. Structural changes are detailed in the next sections for the mutant complexes with respect to the major conformation in PRWT-APV. Generally, the changes in the mutants involved hydrophobic C-H···H-C contacts or C-H···O polar interactions, although shifts of main chain atoms were observed in some cases. The ideal distances between non-hydrogen atoms are considered to be 3.0–3.7 Ǻ for C-H···O interactions and 3.8–4.2 Ǻ for van der Waals interactions as described in [30]. The structural differences are described separately for each mutant.

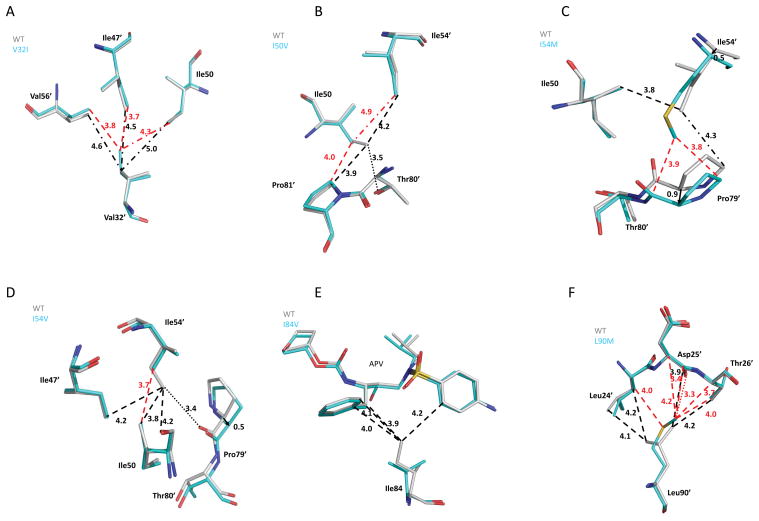

Val32 is an important part of the S2 pocket in the active site cavity and forms van der Waals interactions with inhibitors. In the PRWT-APV structure Val32 forms hydrophobic contacts with Ile47, Ile56, Thr80 and Ile84, while Val32′ interacts with Thr80′ and Ile84′. Mutation of Val to Ile, which adds one methyl group, can reduce the volume of the active site cavity and alter the hydrophobic interactions in the cluster. The mutant with Ile32 did not show significant alterations in the main chain conformation or the interactions with APV, however, the Cδ1 methyl of the Ile side chain provided new van der Waals contacts with other hydrophobic side chains. Ile32 formed new hydrophobic contacts with the side chains of Val56, Leu76, and the main chain atoms of residues 77-78, and Ile32′ showed new interactions with the side chains of Ile47′, Ile50 and Val56′ in the flaps (Fig. 3A). The flaps can exist in an open conformation in the absence of inhibitor and a closed conformation when inhibitor is bound. The interactions of residue 32 differ in the closed and open conformations; Val32 has no hydrophobic contacts with flap residues in the PR-APV structure, while Val32 forms hydrophobic contacts with Ile47 in the open conformation structure [35]. The flexibility of the flaps is likely to be altered in PRV32I by the new hydrophobic contacts of Ile32/32′, which is expected to contribute to the 3-fold reduced catalytic activity and 10-fold decreased APV inhibition of the PRV32I mutant relative to wild type enzyme (Table I).

Figure 3.

The interactions of mutated residues in (a) PRV32I-APV, (b) PRI50V-APV, (c) PRI54M-APV, (d) PRI54V-APV, (e) PRI84V-APV, and (f) PRl90M-APV. The grey color corresponds to wild type PR-APV and the cyan color indicates the mutant complex. Dashed lines indicate van der Waals interactions and dotted lines show C-H···O interactions. Interatomic distances are shown in Å with black lines indicating the PRWT and red lines indicating the mutant. Interatomic distances of > 4.3 Å are shown in dash-dot lines to indicate the absence of favorable interaction.

Ile50 is located at the tip of the flap on each PR monomer where its side chain forms hydrophobic interactions with inhibitors. In the wild type enzyme, Ile50/Ile50′ interacts with Pro81′/Pro81 and Thr80′/Thr80 in the 80’s loop as well as Ile47′/47 and Ile54′/54 in the flaps. The Cδ1 methyl of Ile50 side chain formed C-H···O interactions with the hydroxyl oxygen of Thr80′ and carbonyl oxygen of Pro79′, and the Cδ1 of Ile50′ interacts with the hydroxyl of Thr80. Mutation from Ile50 to Val shortens the side chain by a methyl group, which eliminates the C-H···O interaction with the hydroxyl oxygen of Thr80′ and van der Waals contact with Ile54′ (Fig. 3B). In the other subunit, mutation to Val50′ eliminates the C-H···O interaction with the hydroxyl of Thr80 and a hydrophobic contact with Pro81. The APV in PRI50V complex had two alternate conformations with 0.6/0.4 relative occupancy. The APV showed an elongated hydrogen bond than seen in the PRWT complex between the aniline group and the carbonyl oxygen of Asp30, with interatomic distance of 3.4 Ǻ for the major conformation and 3.5 Ǻ for the minor APV conformation. Val50′ has also lost hydrophobic interactions with the THF group of APV. The minor conformation of APV showed similar changes in interactions with Asp30/30′ as described for the minor APV conformation in the PRWT complex. Overall, the observed structural changes in PRI50V-APV are loss of two C-H···O interactions and van der Waals contacts, the elongated hydrogen bond and reduced hydrophobic contacts with APV. PRI50V shows a large decrease in sensitivity to APV shown by the 30-fold drop in the relative inhibition coupled with 10-fold decreased catalytic efficiency, which suggests the importance of Ile50. Loss of the C-H···O interaction of Val50 with Thr80′ has not been described before. Thr80 is a conserved residue in the PR sequences and its hydroxyl forms a hydrogen bond with the carbonyl oxygen of Val82, which contributes hydrophobic interactions with the inhibitors. Moreover, the hydroxyl group of Thr80 was shown to be important for PR activity using site directed mutagenesis where only mutation to Ser retaining the hydroxyl group, and not to Val or Asn, maintained enzymatic activity [36]. These lines of evidence, taken together, strengthen the suggestion that loss of the C-H···O interaction of residue 50 with the hydroxyl of Thr80, as well as loss of hydrophobic contacts with inhibitor, are important for the decreased catalytic activity and APV inhibition of PRI50V.

Ile54 is another flap residue that forms hydrophobic interactions with Ile50′ and residues 79-80, although it has no direct contact with inhibitor. Mutation I54M introduces a longer side chain, and the nearby main chain atoms have shifted relative to their positions in the wild type PR (Fig. 3C). Compared to PRWT, the Cα of Met54 moved by 0.7 Å, and the longer Met side chain pushed residues 79, 80 and 81 away by 0.7–1.4 Å. In the other subunit the Cα of Met54′ moved by 0.5 Å toward Pro79′, and there was a correlated motion of Pro79′ of 0.9 Å relative to its position in PR-APV. The longer Met54/54′ side chains formed more hydrophobic contacts with Pro79/79′ and Thr80/80′ in PRI54M relative to those of wild type PR. Overall, the Ile54 to Met mutation improved contacts within the hydrophobic cluster, although the interatomic distances to residues 79-80/79′-80′ were increased. Similar structural changes were observed in the PRI54M complexes with darunavir and saquinavir [18]. Despite these correlated changes between the main chain atoms of the flaps and 80′ loops, this mutant was similar to the wild type PR in catalytic efficiency and had only 3-fold reduced inhibition by APV.

In contrast to PRI54M, mutation I54V substitutes the shorter Val in PRI54V. In PRWT, the Cδ1 of Ile54 interacts with Ile50′, Val56, Pro79 and Thr80, while the Cδ1 of Ile54′ shows van der Waals interactions with Ile47′, Ile50′, Val56′, and Pro79 and one C-H···O interaction with the carbonyl oxygen of Pro79′. The shorter Val side chain in the mutant results in loss of several van der Waals contacts with the adjacent residues, thus decreasing the stability of the hydrophobic cluster formed by flap residues 47, 54 and 50′ (Fig. 3D). No C-H···O interaction was possible with Pro79′, which was associated with a shift of ~0.5 Å in Pro79′ increasing the separation of the flap and 80’s loop. The mutation I54V decreased the hydrophobic interactions within the flaps and with Pro79, however, PRI54V showed similar Ki value and only 3-fold reduced activity relative to the wild type enzyme.

Ile84 forms part of the S1/S1′ subsites of PR, and mutation to Val84 removes a methylene moiety, which can reduce interactions with substrates and inhibitors. In wild type PR, van der Waals contacts were found between Cδ1 of Ile84 and the benzyl and aniline moieties of APV and from Cδ1 of Ile84′ to the isopropyl group of APV. These interactions were lost in the PRI84V mutant structure since the interatomic distances increased to >4.3 Å (Fig. 3E). The loss of hydrophobic contacts with APV is consistent with the modest change of 6-fold in Ki value for PRI84V.

Leu90 is located in the short alpha helix outside of the active site cavity, although it extends close to the main chain of the catalytic Asp25. Mutation of Leu90 to Met substituted a longer side chain and introduced new van der Waals contacts with residues Asp25-Thr26. Moreover, the long Met90/90′ side chains formed close C-H···O interactions with the carbonyl oxygen of the catalytic Asp25 and Asp25′ (Fig. 3F). The alternate conformations of the Met90 side chain were arranged as described previously [25]. The new interactions of Met90/90′ with the catalytic aspartates and adjacent residues are presumed to play an important role in the observed 11-fold increase in catalytic activity, as described previously [19, 25]. The increased catalytic efficiency of the PRL90M mutant is mainly due to almost 5-fold higher kcat. On the other hand, the KM of the mutant is only about half that of the wild type enzyme. Therefore, the new interactions of Met90 with the catalytic residues that are absent in the wild type structure may minimally affect the binding of substrate, but at the same time dramatically lower the activation barrier for substrate hydrolysis leading to substantial improvement of the PRL90M catalytic activity. No change, however, was detected in the APV inhibition of PRL90M.

Comparison of the mutant complexes with APV and SQV

The structures of HIV-1 protease complexes with APV or SQV were analyzed in order to understand their distinct drug resistance profiles. PRWT-APV was compared with PRWT-SQV (2NMW) solved at 1.16 Ǻ resolution in a different unit cell and space group P212121 [12]. The mutant APV complexes reported here were compared with the published SQV complexes of PRI50V-SQV (3CYX), PRI54M-SQV (3D1X), PRI54V-SQV (3D1Y) and PRI84V-SQV (2NNK) refined at resolutions of 1.05 to 1.25 Å in the isomorphous unit cell and identical space group P21212 as for all the APV complexes [12, 18]. No SQV complexes have been reported for mutants PRV32I and PRL90M. A lower resolution (2.6 Ǻ) crystal structure has been reported for the SQV complex with the double mutant PRG48V/L90M[37], in which Met90 showed interactions similar to those seen in the structure of PRL90M-APV. To analyze how the PR conformation alters to fit the different inhibitors, all structures were superimposed on the PRWT-APV structure. The superposition was tested for both possible arrangements of the two subunits in the asymmetric dimer of HIV PR, i.e., superimposing residues 1-99 and 1′-99′ with 1-99 and 1′-99′, as well as with the opposite subunit arrangement of 1′-99′ and 1-99. The arrangement with the lowest RMS deviation was used in further comparison. Interestingly, the major conformation of SQV has the opposite orientation to that of APV for the superimposed dimers with the lowest RMS values. PRWT-SQV had the highest RMS deviation value of 0.87 Ǻ on Cα atoms due to the different space groups, while the RMS deviations for the mutant complexes with SQV were lower, ranging from 0.29 to 0.36 Ǻ, as usual for two structures in the same space group (Table II).

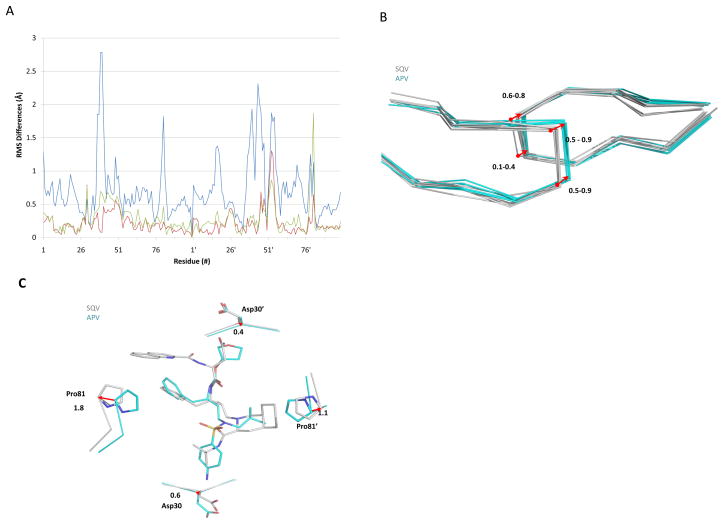

The corresponding pairs of wild type and mutant complexes with the two inhibitors were compared (Fig. 4A). The structures of PRWT-SQV and PRWT-APV showed larger RMS deviations of >1.0Å for residues in surface loops, probably arising from altered lattice contacts due to the different space groups as reported previously [25]. Moreover, the two subunits in the dimer show asymmetric deviations due to non-identical lattice contacts as well as the presence of different asymmetric inhibitors. Changes in residues 52′-56′, 79′-81′ in the active site cavity are assumed to reflect variation in the interactions with the two inhibitors, while the lower deviations of catalytic triplet residues 25-27/25′-27′ reflect their important function. The pairs of mutant complexes were determined in isomorphous unit cells with less overall variation so that changes are more likely to arise from different interactions with APV and SQV. PRI50V had the fewest RMS differences between the two inhibitor complexes with a peak of 1.3 Ǻ for Phe53′. PRI54V and PRI84V showed the largest change for Pro81′ of 1.9 and 1.6 Ǻ, respectively, while PRI54M showed the maximum RMS deviation of 1.2 Ǻ at residue 54′. Three regions were analyzed in more detail due to their flexibility and proximity to inhibitors and mutations: the flaps, the 80’s loops, and the hydrophobic clusters formed by residues Ile47, Ile54, Thr80, Ile84 and Ile50′ from the opposite subunit.

Figure 4.

Structural differences between APV and SQV complexes. (a) The root mean square (RMS) difference (Å) per residue is plotted for Cα atoms of SQV complexes compared with the corresponding APV complexes: PRWT (blue line), PRI50V (red line) and PRI54V (green line). (b) Comparison of the flap regions in the structures. The complexes with APV are in cyan, and the complexes with SQV are in grey. The arrow indicates the shifts between Cα atoms at the residues 50 and 51 in the PR complexes with the two inhibitors. (c) The width across the S1-S1′ subsites increases in PRWT-SQV relative to PRWT-APV. Similar changes were seen for the mutant complexes, except for PRI50V.

The conformation of the flaps segregated into two categories corresponding to the APV complexes and the SQV complexes (Fig. 4B). The coordinated changes in the flaps were most obvious for residues 50-51 and 50′-51′ at the tips of the flaps. The flap residues 50 and 51 showed differences in Cα position of 0.5–0.9 Å between the complexes with APV or SQV. Differences of 0.6–0.8 Å at Gly51′ and 0.1–0.4 Å at Ile/Val50′ were seen in the flap from the other subunit. The different flap conformations are probably related to the larger chemical groups at P2 and P1′ in SQV compared to those in APV (Fig. 1).

Changes in the 80’s loops, which have been described as intrinsically flexible [12, 25, 38] and function in substrate recognition [39–40], were assessed using the distance between the Cα atoms of Pro81 and Pro81′ to reflect alterations in the S1/S1′ subsites. Pro81 and Pro81′ were separated by 17.6–19.4 Å in the APV complexes, while these residues were 0.7–2.5 Å further apart in the SQV complexes (separations of 18.5–20.5 Å). The comparison of wild type complexes is shown in Figure 4C. PRI50V complexes had the smallest distance between Pro81 and Pro81′, while the greatest separation was observed for PRI54M complexes probably due to close contacts of the longer Met54/54′ side chains with the 80’s loops in both inhibitor complexes. The distance between Pro81 and Pro81′ in the other structures was about 2.5 Å longer in the SQV complexes compared to the APV complexes, which corresponds to the increment of the width across the S1/S1′ pockets caused by binding of the big decahydroisoquinoline P1′ group of SQV instead of the smaller P1′ group in APV (Fig. 4C) [12].

The more rigid region of Asp30/30′ showed smaller shifts of ~0.5 Å for the Cα atoms. The different P2 and P2′ groups, THF in APV or Asn in SQV at P2 and aniline in APV or t-butyl group in SQV at P2′, are accommodated by these shifts, as shown in Figure 4C.

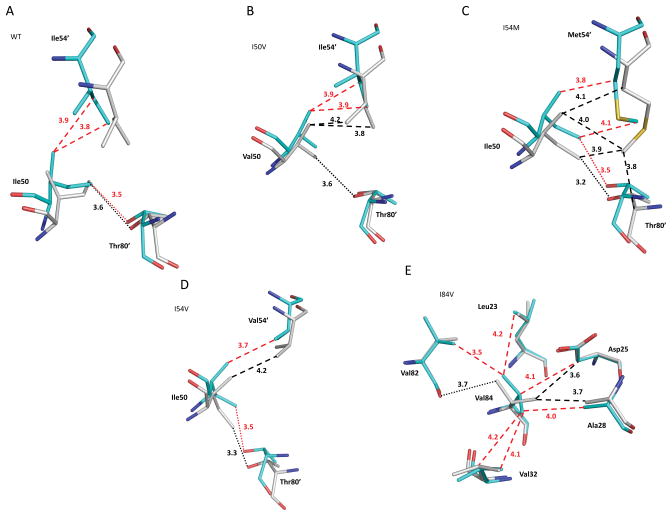

The side chain interactions within the inner hydrophobic cluster were analyzed in PRWT, PRI50V, PRI54M, and PRI54V complexes with SQV and APV. Overall, the main chains of the flaps were shifted relative to the 80′ loops in APV complexes compared to SQV complexes. The hydrophobic cluster around the active site is formed by Ile47, Ile54, Thr80, and Ile84 from one subunit and Ile50′ from the opposite subunit, as well as Val32 in a more rigid region in PRWT. Differences in the side chain interactions are described. In PRWT-APV the Cγ1 of Ile50 made good van der Waals contacts with Ile54′, but the side chains were further apart in PRWT-SQV (Fig. 5A). One C-H···O interaction between Cδ1 of Ile50/Ile50′ and the hydroxyl of Thr80′/Thr80 was conserved in PRWT-APV, PRWT-SQV, and PRI50V-SQV. The structure of PRI50V-APV, however, has lost this C-H···O interaction of residue 50 with the hydroxyl of Thr80′, which reduces the interactions between the flap and the 80’s loop (Fig. 5B). Mutation of Thr80 to Val80, which eliminates the C-H···O interaction with Ile50 Cδ1, significantly reduces the catalytic activity and binding affinity of SQV [36]. Besides the different interactions between PR and inhibitors, the loss of the C-H···O contact between residue 50 and Thr80 in PRI50V-APV and not in PRI50V-SQV, appears to correlate with the observed drug resistance. Mutation I50V is associated strongly with resistance to APV, but not to SQV.

Figure 5.

Interactions of Ile50, Ile54′ and Thr80′. (a) PRWT-APV compared to PRWT-SQV. (b) PRI50V-APV compared to PRI50V-SQV. (c) PRI54M-APV compared to PRI54M-SQV. (d) PRI54V-APV compared to PRI54V-SQV. (e) PRI84V-APV compared to PRI84V-SQV. Dashed lines indicate van der Waals contacts with interatomic distances in Å. Dotted lines indicate C-H···O interactions. Black lines indicate interactions in SQV complexes. Red lines indicate interactions in APV complexes.

In the PRI54M and PRI54V complexes with both inhibitors, however, similar interactions were observed among the side chains of residues 50, 54′ and 80′ (Fig. 5C-5D). Val84 in PRI84V-SQV had fewer hydrophobic contacts than in PRI84V-APV, but it had one C-H···O interaction between Cγ2 of Val84 and the carbonyl oxygen of Val82 (Fig. 5E). In contrast to the significant conformational shifts in main chain atoms, the side chains in this hydrophobic cluster generally have rearranged to maintain internal hydrophobic contacts in the complexes with both inhibitors.

DISCUSSION

We have described an atomic resolution crystal structure of PRWT with APV, and analyzed structural changes in the APV complexes with mutants PRV32I, PRI50V, PRI54V, PRV82A, PRI84V, and PRL90M. The mutated residues contribute to an inner hydrophobic cluster around the substrate binding cavity, with the exception of Leu90 that is located near the backbone of the catalytic Asp25 in the outer hydrophobic cluster (Fig. 1B). Studies of the patterns of resistance mutations and molecular dynamics simulations have suggested the importance of these hydrophobic mutations in drug resistance [14, 41]. Our analysis showed that interactions within the inner hydrophobic cluster containing residues 32, 47, 54 and 50 were frequently altered relative to those in the wild type enzyme. Mutations to larger side chains in PRV32I, PRI54M and PRL90M resulted in formation of new hydrophobic contacts with flap residues, residues 79 and 80, and Asp25, respectively. Mutation to smaller side chains caused loss of internal hydrophobic interactions in the PRI50V and PRI54V structures. PRI84V, PRV32I, and PRI50V showed reduced APV inhibition by 6-, 10- and 30-fold, respectively, relative to wild type PR, which is consistent with the observed structural changes. The PRI84V-APV complex had lost hydrophobic contacts with APV, the PRV32I-APV complex showed increased hydrophobic contacts with the flaps that are likely to restrict the flexibility needed for catalysis, and the PRI50V complex had weaker interactions with APV. Ile54 has no direct contacts with APV, which is consistent with the relatively small changes in inhibition, catalytic properties, protease stability, and structure shown by the I54 mutants. No compensating changes were identified elsewhere in the hydrophobic core. In PRL90M, the longer side chain of Met90/90′ lies close to the main chain of the catalytic aspartates forming new van der Waals contacts and a C-H···O interaction. These new contacts with Asp25/25′ near the dimer interface correlate with the reduced stability and altered catalytic parameters of this mutant, as described in studies with IDV and DRV [19, 25]. No evidence was found, however, that PRL90M-APV had substantially altered the volume of the S1/S1′ substrate binding pockets, unlike the PRG48V/L90M-SQV structure, which showed reduced volume for the S1/S1′ subsites relative to the wild type complex [37]. Also, the structure of PRG48V-DRV showed reduced volume of the active site cavity relative to the wild type complex, consistent with a major effect of the G48V rather than the L90M mutation in reducing the S1/S1′ volume in PRG48V/L90M-SQV [18]. Reduced interactions with inhibitors and conformational adjustments of the flaps and 80’s loops were observed in our previous studies of these mutants with other inhibitors [17–19, 25, 30, 42]. These structural changes are expected to contribute to drug resistance. However, crystal structures show only a static picture of the effect of mutations, while changes in protein dynamic and thermodynamic properties likely also contribute to resistance. Future studies using molecular dynamics simulations and calorimetric analysis will help to address the changes in these other properties.

Individual mutations have distinct effects on the protease structure and activity, however, drug resistant clinical isolates generally accumulate multiple mutations. Previous studies of double and single mutants suggested that the structural changes due to a single mutation were retained in the double mutant, although other properties did not combine in predictable ways [43]. A variety of structural and biochemical mechanisms have been reported for different combinations of mutations including: compensating structural changes, altered interactions with inhibitor, and substantial opening of the active site cavity [44–46]. Clearly, further studies are needed to assess the effects of the multiple protease mutations that are observed clinically.

Comparison of the APV complexes with the corresponding SQV complexes for PRWT, PRI50V, PRI54V, and PRI84V showed changes in the conformation of the flexible flaps and 80’s loops. Despite the conformational changes in main chain atoms, the internal side chains generally have rearranged to preserve the internal hydrophobic contacts in the complexes with both inhibitors. The structural changes can be correlated with the type of inhibitor. In particular, the separation of Pro81 and Pro81′ was significantly smaller in the complexes with APV compared to the equivalent SQV complexes, which reflects the smaller size of the P1′ group in APV relative to that of SQV. Also, the flexible side chains of Asp30 and Asp30′ accommodate diverse functional groups at P2 and P2′ of SQV and APV at the surface of the PR active site cavity. The functional group can be critical for a tight binding inhibitor. For example, DRV was derived from APV by changing THF to bis-THF, which introduces more hydrogen bonds with PR main chain atoms and dramatically increases the potency on drug resistant HIV [47].

APV was designed to include several hydrophilic interactions with PR, and SQV optimizes hydrophobic interactions with PR [12]. Both of the inhibitors have been classified as peptidomimetic inhibitors, which mimic PR-substrate interactions and block enzyme activity, although, APV has only a single CO-NH peptide bond compared to three in SQV [48]. Resistant mutations within the hydrophobic clusters frequently involve small changes such as addition or deletion of a methylene group [13]. Mutations within the hydrophobic cluster have the potential to alter the flap dynamics or stability of PR as well as the binding of inhibitors, as shown in our structural analysis. The current drugs target the active site cavity and demonstrate strong binding to the catalytic Asps [49]. The hydrophobic pockets around the substrate binding site have been proposed as an alternate drug target [50–51]. However, our structural analysis shows that side chains in the hydrophobic cluster can rearrange readily to maintain the PR structure and activity, suggesting this region is a poor target for drugs.

The accuracy of high and atomic resolution crystal structures is critical for deciphering how mutations and inhibitors alter the HIV-1 PR structure. Here, we describe how HIV-1 PR recognizes the inhibitors APV and SQV by structural rearrangements of the two beta-hairpin flaps and two 80’s loops, and how the same mutation results in different structural changes with the two drugs. Comparison of the structures provides insight into why I50V is a major drug resistant mutation observed on exposure to APV but appears less critical in resistance to SQV therapy. Besides the different interactions between PR and inhibitors, the absence of the C-H···O contact between flap residue 50 and Thr80 in PRI50V-APV, and its presence in PRI50V-SQV and PRWT complexes, contributes to the drug resistance of this mutation. The conclusion is that small rearrangements of the PR loops enclosing the inhibitor combined with changes in weak internal interactions produce the distinct patterns of resistant mutations for the two drugs.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Expression and Purification

The HIV-1 PR and mutants were constructed with five mutations Q7K, L33I, L63I, C67A, and C95A to prevent cysteine-thiol oxidation and diminish autoproteolysis [52]. The expression, purification and refolding methods are described in [52–53].

Kinetic Assays

The fluorogenic substrate Abz-Thr-Ile-Nle-p-nitro-Phe-Gln-Arg-NH2, where Abz is anthranilic acid and Nle is norleucine, (Bachem) with sequence derived from the p2/NC cleavage site of the Gag polyprotein was used in kinetic assays. Proteases were diluted in reaction buffer (100 mM MES, pH 5.6, 400mM sodium chloride, 1 mM EDTA, and 5% glycerol). 10 μL diluted enzyme was mixed with 98 μL reaction buffer and 2μL Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) or APV (dissolved in DMSO) and incubated at 37 oC for 5 min. Then, the reaction was initialized with addition of 90μL substrate. The reaction was monitored over 5 min in the POLARstar OPTIMA microplate reader at wavelengths of 340 nm and 420 nm for excitation and emission. Data analysis used the program SigmaPlot 9.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Km and kcat values were obtained by standard data-fitting with the Michaelis-Menten equation. The Ki value was obtained from the IC50 values estimated from an inhibitor dose-response curve using the equation Ki = (IC50−[E]/2)/(1+[S]/Km), where [E] and [S] are the PR and substrate concentrations.

Crystallographic Analysis

Inhibitor APV (from AIDS reagent program) was dissolved in DMSO by vortex-mixing. The mixture was incubated on ice prior to centrifugation to remove any insoluble material. The inhibitor was mixed with 2.2 mg/ml protein in molar ratio of 5:1 in most cases. The two exceptions were: 3.5 mg/ml of PRI50V was used with inhibitor-protein ratio of 10:1, and 3.7 mg/ml of PRL90M. The crystallization trials employed the hanging drop method using equal volumes of enzyme-inhibitor and reservoir solution. PRWT-APV was crystallized from 0.1M MES, pH 5.6, and 0.6–0.8 M sodium chloride. Crystals of PRV32I-APV and PRI50V-APV were grown from 0.1M sodium acetate, pH 5.4, 0.4 M and 1.2 M sodium chloride, respectively. PRI54M-APV crystals were grown from 0.1M sodium acetate, pH 4.6, and 0.67 M sodium chloride. PRI54V-APV and PRI84V-APV crystals were grown from 0.1 M sodium acetate, pH 5.4 and 4.0, respectively, and 0.13 M sodium iodide, and PRL90M-APV crystals from 0.1 M sodium acetate, pH 4.8 and 0.2 M sodium iodide. Single crystals were mounted on fiber loops with 20 to 30 % (v/v) glycerol as cryoprotectant in the reservoir solution. X-ray diffraction data were collected at the SER-CAT beamline of the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratories. Diffraction data were integrated, scaled, and merged using the HKL2000 package [54]. PRWT-APV, PRV32I-APV and PRI50V-APV were solved by molecular replacement program Phaser [55] with the protein atoms of structure 2QCI[32] as the starting model. The other complexes were solved by MOLREP [56], using the protein atoms of 2F8G as the starting model [19]. The crystal structures were refined using SHELX-97 [57], except that the lower resolution structure of PRI84V-APV was refined with REFMAC 5.2 [58]. The diffraction-data precision indicator (DPI) was used for determining the accuracy in the atomic positions [59]. The molecular graphics program COOT was used for map display and model building [60]. Structural figures were made by PyMol [61]. The structures were compared by superimposing their Cα atoms and using HIVAGENT [62] to calculate the distance between two atoms. The cut-off distances for different interactions were as described in [30].

Supplementary Material

Figure S1: 2Fo-Fc electron density maps for the mutated residue in PRV32I, PRI50V, PRI54M, PRI54V, PRI84V, and PRL90M complexes with APV.

Table S1: Hydrogen bond interactions between HIV-1 protease and APV

Table S2: C-H···O interactions between HIV-1 protease and APV.

Acknowledgments

C.S. was supported in part by the Georgia State University Research Program Enhancement award. The research was supported in part by the National Institute of Health grant GM062920. We thank the staff at SER-CAT beamline at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory, for assistance during X-ray data collection. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U. S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. W-31-109-Eng-38.

Abbreviations

- HIV-1

human immunodeficiency virus type 1

- PR

HIV-1 protease (EC 3.4.23.16)

- PRV32I

PR with V32I mutation

- PRI50V

PR with I50V mutation

- PRI54V

PR with I54V mutation

- PRI54M

PR with I54M mutation

- PRI84V

PR with I84V mutation

- PRL90M

PR with L90M mutation

- APV

amprenavir

- SQV

saquinavir

- RMS

root mean square

Footnotes

Database Accession Codes: The atomic coordinates and structure factors are available in the Protein Data Bank with accession code 3NU3 for wild-type HIV-1 PR-APV, 3NU4 for PRV32I-APV, 3NU5 for PRI50V-APV, 3NU6 for PRI54M-APV, 3NUJ for PRI54V-APV, 3NU9 for PRI84V–APV, and 3NUO for PRL90M-APV.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. 2008 Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic UNAIDS Publication Series. World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tozser J. HIV inhibitors: problems and reality. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;946:145–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker BD, Burton DR. Toward an AIDS vaccine. Science. 2008;320:760–764. doi: 10.1126/science.1152622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Condra JH, Schleif WA, Blahy OM, Gabryelski LJ, Graham DJ, Quintero JC, Rhodes A, Robbins HL, Roth E, Shivaprakash M, et al. In vivo emergence of HIV-1 variants resistant to multiple protease inhibitors. Nature. 1995;374:569–571. doi: 10.1038/374569a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gottlinger HG, Sodroski JG, Haseltine WA. Role of capsid precursor processing and myristoylation in morphogenesis and infectivity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:5781–5785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Louis JM, Ishima R, Torchia DA, Weber IT. HIV-1 Protease: Structure, Dynamics, and Inhibition. Adv Pharmacol. 2007;55:261–298. doi: 10.1016/S1054-3589(07)55008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weber IT, Kovalevsky AY, Harrison RW. Frontiers in Drug Design & Discovery. Vol. 3. Bentham Science Publishers; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim EE, Baker CT, Dwyer MD, Murcko MA, Rao BG, Tung RD, Navia MA. Crystal structure of HIV-1 protease in complex with VX-478, a potent and orally bioavailable inhibitor of the enzyme. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:1181–1182. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams GC, Sinko PJ. Oral absorption of the HIV protease inhibitors: a current update. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1999;39:211–238. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(99)00027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Surleraux DL, Tahri A, Verschueren WG, Pille GM, de Kock HA, Jonckers TH, Peeters A, De Meyer S, Azijn H, Pauwels R, et al. Discovery and selection of TMC114, a next generation HIV-1 protease inhibitor. J Med Chem. 2005;48:1813–1822. doi: 10.1021/jm049560p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krohn A, Redshaw S, Ritchie JC, Graves BJ, Hatada MH. Novel binding mode of highly potent HIV-proteinase inhibitors incorporating the (R)-hydroxyethylamine isostere. J Med Chem. 1991;34:3340–3342. doi: 10.1021/jm00115a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tie Y, Kovalevsky AY, Boross P, Wang YF, Ghosh AK, Tozser J, Harrison RW, Weber IT. Atomic resolution crystal structures of HIV-1 protease and mutants V82A and I84V with saquinavir. Proteins. 2007;67:232–242. doi: 10.1002/prot.21304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson VA, Brun-Vezinet F, Clotet B, Gunthard HF, Kuritzkes DR, Pillay D, Schapiro JM, Richman DD. Update of the Drug Resistance Mutations in HIV-1. Top HIV Med. 2008;16:138–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu TD, Schiffer CA, Gonzales MJ, Taylor J, Kantor R, Chou S, Israelski D, Zolopa AR, Fessel WJ, Shafer RW. Mutation patterns and structural correlates in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease following different protease inhibitor treatments. J Virol. 2003;77:4836–4847. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.4836-4847.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu F, Kovalevsky AY, Louis JM, Boross PI, Wang YF, Harrison RW, Weber IT. Mechanism of drug resistance revealed by the crystal structure of the unliganded HIV-1 protease with F53L mutation. J Mol Biol. 2006;358:1191–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.02.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pazhanisamy S, Stuver CM, Cullinan AB, Margolin N, Rao BG, Livingston DJ. Kinetic characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 protease-resistant variants. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17979–17985. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu F, Boross PI, Wang YF, Tozser J, Louis JM, Harrison RW, Weber IT. Kinetic, stability, and structural changes in high-resolution crystal structures of HIV-1 protease with drug-resistant mutations L24I, I50V, and G73S. J Mol Biol. 2005;354:789–800. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu F, Kovalevsky AY, Tie Y, Ghosh AK, Harrison RW, Weber IT. Effect of flap mutations on structure of HIV-1 protease and inhibition by saquinavir and darunavir. J Mol Biol. 2008;381:102–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.05.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kovalevsky AY, Tie Y, Liu F, Boross PI, Wang YF, Leshchenko S, Ghosh AK, Harrison RW, Weber IT. Effectiveness of nonpeptide clinical inhibitor TMC-114 on HIV-1 protease with highly drug resistant mutations D30N, I50V, and L90M. J Med Chem. 2006;49:1379–1387. doi: 10.1021/jm050943c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy MD, Marousek GI, Chou S. HIV protease mutations associated with amprenavir resistance during salvage therapy: importance of I54M. J Clin Virol. 2004;30:62–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2003.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roberts NA, Craig JC, Sheldon J. Resistance and cross-resistance with saquinavir and other HIV protease inhibitors: theory and practice. AIDS. 1998;12:453–460. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199805000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoffman NG, Schiffer CA, Swanstrom R. Covariation of amino acid positions in HIV-1 protease. Virology. 2003;314:536–548. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00484-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maguire M, Shortino D, Klein A, Harris W, Manohitharajah V, Tisdale M, Elston R, Yeo J, Randall S, Xu F, et al. Emergence of resistance to protease inhibitor amprenavir in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected patients: selection of four alternative viral protease genotypes and influence of viral susceptibility to coadministered reverse transcriptase nucleoside inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:731–738. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.3.731-738.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishima R, Louis JM, Torchia DA. Characterization of two hydrophobic methyl clusters in HIV-1 protease by NMR spin relaxation in solution. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:515–521. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahalingam B, Wang YF, Boross PI, Tozser J, Louis JM, Harrison RW, Weber IT. Crystal structures of HIV protease V82A and L90M mutants reveal changes in the indinavir-binding site. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:1516–1524. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christian B, Anfinsen JTE, Richards Frederic M. Advances in Protein Chemistry. Vol. 47. Academic Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kellis JT, Jr, Nyberg K, Sali D, Fersht AR. Contribution of hydrophobic interactions to protein stability. Nature. 1988;333:784–786. doi: 10.1038/333784a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fioravanti E, Vellieux FM, Amara P, Madern D, Weik M. Specific radiation damage to acidic residues and its relation to their chemical and structural environment. J Synchrotron Radiat. 2007;14:84–91. doi: 10.1107/S0909049506038623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vaguine AA, Richelle J, Wodak SJ. SFCHECK: a unified set of procedures for evaluating the quality of macromolecular structure-factor data and their agreement with the atomic model. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1999;55:191–205. doi: 10.1107/S0907444998006684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kovalevsky AY, Liu F, Leshchenko S, Ghosh AK, Louis JM, Harrison RW, Weber IT. Ultra-high resolution crystal structure of HIV-1 protease mutant reveals two binding sites for clinical inhibitor TMC114. J Mol Biol. 2006;363:161–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghosh AK, Gemma S, Baldridge A, Wang YF, Kovalevsky AY, Koh Y, Weber IT, Mitsuya H. Flexible cyclic ethers/polyethers as novel P2-ligands for HIV-1 protease inhibitors: design, synthesis, biological evaluation, and protein-ligand X-ray studies. J Med Chem. 2008;51:6021–6033. doi: 10.1021/jm8004543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang YF, Tie Y, Boross PI, Tozser J, Ghosh AK, Harrison RW, Weber IT. Potent new antiviral compound shows similar inhibition and structural interactions with drug resistant mutants and wild type HIV-1 protease. J Med Chem. 2007;50:4509–4515. doi: 10.1021/jm070482q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tie Y, Boross PI, Wang YF, Gaddis L, Liu F, Chen X, Tozser J, Harrison RW, Weber IT. Molecular basis for substrate recognition and drug resistance from 1.1 to 1.6 angstroms resolution crystal structures of HIV-1 protease mutants with substrate analogs. FEBS J. 2005;272:5265–5277. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gustchina A, Sansom C, Prevost M, Richelle J, Wodak SY, Wlodawer A, Weber IT. Energy calculations and analysis of HIV-1 protease-inhibitor crystal structures. Protein Eng. 1994;7:309–317. doi: 10.1093/protein/7.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spinelli S, Liu QZ, Alzari PM, Hirel PH, Poljak RJ. The three-dimensional structure of the aspartyl protease from the HIV-1 isolate BRU. Biochimie. 1991;73:1391–1396. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(91)90169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Foulkes JE, Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Cooper D, Henderson GJ, Harris J, Swanstrom R, Schiffer CA. Role of invariant Thr80 in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease structure, function, and viral infectivity. J Virol. 2006;80:6906–6916. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01900-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hong L, Zhang XC, Hartsuck JA, Tang J. Crystal structure of an in vivo HIV-1 protease mutant in complex with saquinavir: insights into the mechanisms of drug resistance. Protein Sci. 2000;9:1898–1904. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.10.1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Nalivaika E, Schiffer CA. How does a symmetric dimer recognize an asymmetric substrate? A substrate complex of HIV-1 protease. J Mol Biol. 2000;301:1207–1220. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Short GF, 3rd, Laikhter AL, Lodder M, Shayo Y, Arslan T, Hecht SM. Probing the S1/S1′ substrate binding pocket geometry of HIV-1 protease with modified aspartic acid analogues. Biochemistry. 2000;39:8768–8781. doi: 10.1021/bi000214t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stebbins J, Towler EM, Tennant MG, Deckman IC, Debouck C. The 80’s loop (residues 78 to 85) is important for the differential activity of retroviral proteases. J Mol Biol. 1997;267:467–475. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Foulkes-Murzycki JE, Scott WR, Schiffer CA. Hydrophobic sliding: a possible mechanism for drug resistance in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease. Structure. 2007;15:225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tie Y, Boross PI, Wang YF, Gaddis L, Hussain AK, Leshchenko S, Ghosh AK, Louis JM, Harrison RW, Weber IT. High resolution crystal structures of HIV-1 protease with a potent non-peptide inhibitor (UIC-94017) active against multi-drug-resistant clinical strains. J Mol Biol. 2004;338:341–352. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mahalingam B, Boross P, Wang YF, Louis JM, Fischer CC, Tozser J, Harrison RW, Weber IT. Combining mutations in HIV-1 protease to understand mechanisms of resistance. Proteins. 2002;48:107–116. doi: 10.1002/prot.10140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heaslet H, Kutilek V, Morris GM, Lin YC, Elder JH, Torbett BE, Stout CD. Structural insights into the mechanisms of drug resistance in HIV-1 protease NL4-3. J Mol Biol. 2006;356:967–981. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martin P, Vickrey JF, Proteasa G, Jimenez YL, Wawrzak Z, Winters MA, Merigan TC, Kovari LC. “Wide-open” 1.3 A structure of a multidrug-resistant HIV-1 protease as a drug target. Structure. 2005;13:1887–1895. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saskova KG, Kozisek M, Rezacova P, Brynda J, Yashina T, Kagan RM, Konvalinka J. Molecular characterization of clinical isolates of human immunodeficiency virus resistant to the protease inhibitor darunavir. J Virol. 2009;83:8810–8818. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00451-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koh Y, Nakata H, Maeda K, Ogata H, Bilcer G, Devasamudram T, Kincaid JF, Boross P, Wang YF, Tie Y, et al. Novel bis-tetrahydrofuranylurethane-containing nonpeptidic protease inhibitor (PI) UIC-94017 (TMC114) with potent activity against multi-PI-resistant human immunodeficiency virus in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:3123–3129. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.10.3123-3129.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Randolph JT, DeGoey DA. Peptidomimetic inhibitors of HIV protease. Curr Top Med Chem. 2004;4:1079–1095. doi: 10.2174/1568026043388330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sayer JM, Liu F, Ishima R, Weber IT, Louis JM. Effect of the active site D25N mutation on the structure, stability, and ligand binding of the mature HIV-1 protease. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:13459–13470. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708506200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cigler P, Kozisek M, Rezacova P, Brynda J, Otwinowski Z, Pokorna J, Plesek J, Gruner B, Doleckova-Maresova L, Masa M, et al. From nonpeptide toward noncarbon protease inhibitors: metallacarboranes as specific and potent inhibitors of HIV protease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15394–15399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507577102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Damm KL, Ung PM, Quintero JJ, Gestwicki JE, Carlson HA. A poke in the eye: inhibiting HIV-1 protease through its flap-recognition pocket. Biopolymers. 2008;89:643–652. doi: 10.1002/bip.20993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wondrak EM, Louis JM. Influence of flanking sequences on the dimer stability of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease. Biochemistry. 1996;35:12957–12962. doi: 10.1021/bi960984y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mahalingam B, Louis JM, Hung J, Harrison RW, Weber IT. Structural implications of drug-resistant mutants of HIV-1 protease: high-resolution crystal structures of the mutant protease/substrate analogue complexes. Proteins. 2001;43:455–464. doi: 10.1002/prot.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;267:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Likelihood-enhanced fast translation functions. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2005;61:458–464. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905001617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vagin A, Teplyakov A. MOLREP: an Automated Program for Molecular Replacement. J Appl Crystallogr. 1997;30:1022–1025. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sheldrick GM, Schneider TR. SHELXL: high-resolution refinement. Methods Enzymol. 1997;277:319–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dodson E. Macromolecular refinement: proceedings of the CCP4 Study weekend. CCLRC Daresbury Laboratory; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: Model-Building Tools for Molecular Graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. DeLano Scientific; San Carlos, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tie Y. PhD. Georgia State University; Atlanta: 2006. Crystallographic Analysis and Kinetic Studies of HIV-1 Protease and Drug-Resistant Mutants. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: 2Fo-Fc electron density maps for the mutated residue in PRV32I, PRI50V, PRI54M, PRI54V, PRI84V, and PRL90M complexes with APV.

Table S1: Hydrogen bond interactions between HIV-1 protease and APV

Table S2: C-H···O interactions between HIV-1 protease and APV.