Abstract

It has been suggested that the enzymatic pathway of 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) influences brain functioning and pathobiology. The mRNAs for both the enzyme 5-LOX and its activating protein FLAP have been found in the cerebellum. In this work, we investigated the cellular expression of 5-LOX in the adult mouse cerebellar cortex. We used the in situ mRNA hybridization assay, immunocytochemistry, laser capture microdissection, and our previously developed method for assaying the DNA methylation status of a putative mouse 5-LOX promoter. Since both 5-LOX mRNA in situ hybridization signal and FLAP immunoreactivity co-localize with calbindin 28kD immunoreactivity (a Purkinje cell marker) but not with S-100β immunoreactivity (a Bergmann glia marker), the suggestion is that the 5-LOX pathway is expressed in cerebellar Purkinje cells. We found that methylation in the sites targeted by methylation-sensitive restriction endonucleases AciI and HinP1I but not BstUI and HpaII was greater in DNA samples obtained from a high-5-LOX-expressing cerebellar region (Purkinje cells) vs. a low-5-LOX-expressing region (the molecular cell layer), suggesting a possible epigenetic contribution to the cell-specific 5-LOX expression in the cerebellum. We propose that Purkinje cell-localized 5-LOX and FLAP expression may be involved in the cerebellar synthesis of leukotrienes and/or could influence the Dicer-mediated microRNA formation and processes of neuroplasticity.

Keywords: 5-Lipoxygenase, cerebellum, Purkinje cell, Dicer, DNA methylation, FLAP

Several lines of research have established the presence of the 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX; EC 1.13.11.34) pathway in the central nervous system (CNS) (Chinnici et al., 2007; Chu and Praticò, 2009; Lindgren et al., 1984; Miyamoto et al., 1987; Ohtsuki et al., 1995). Information about the site and the cell types responsible for the synthesis of 5-LOX products, the inflammatory leukotrienes and the anti-inflammatory lipoxins (Radmark et al., 2007, Serhan et al., 2008) in the CNS points to brain region differences in leukotriene formation (Chinnici et al., 2007; Miyamoto et al., 1987) and indicates the possibility of transcellular biosynthesis of cysteinyl leukotrienes in neuronal and glial cells (Farias et al., 2007).

5-LOX expression is relatively high in neuronal precursor cells (Wada et al., 2006), including immature cerebellar granule neurons grown in-vitro (Uz et al., 2001). In these in-vitro models, 5-LOX appears to be involved in mechanisms of cell proliferation and differentiation and in neuroplasticity, such as hedgehog-dependent neurite projection (Bijlsma et al., 2008). In the adult brain, in addition to their strong hippocampal expression, the mRNAs for both 5-LOX and its activating protein FLAP (5-lipoxygenase activating protein) were found in the cerebellum (Lammers et al., 1996) but their cellular distribution has not been studied. Recently, the expression of cerebellar 5-LOX was confirmed in samples of mouse cerebellum (Chinnici et al., 2007) and in post-mortem human cerebellum (Zhang et al., 2006). In a human cerebellar cortex, 5-LOX immunoreactivity was predominantly found in the cytosol of the Purkinje cells (Zhang et al., 2006).

The expression of the ALOX5 gene, which encodes 5-LOX is influenced by epigenetic mechanisms such as DNA methylation (Katryniok et al., 2010; Uhl et al., 2002, 2003, Vikman et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2004). Most current knowledge about the role of DNA methylation in regulating 5-LOX expression has been obtained from studies of the human 5-LOX gene (on chromosome 10) and its promoter which possesses a unique GC-rich region and is a target of methylation modifications (Katryniok et al., 2010). In contrast to the human gene, the mouse 5-LOX gene (on chromosome 6) lacks the typical CpG islands found in the human sequence. Nevertheless, the methylation status of the non-island CpG loci appears to be equally relevant for gene regulation (Oakes et al., 2007). With respect to the mouse 5-LOX gene, this type of DNA methylation in cerebellar cells in vitro (Imbesi et al., 2009) and in vivo (Dzitoyeva et al., 2009) is influenced by developmental and aging-related mechanisms. The available data on cerebellar 5-LOX DNA methylation only report results from studies in brain homogenates and lack information regarding region or cell specificity.

In this work, we investigated the cellular expression of 5-LOX in mouse cerebellar cortex. Furthermore, using a method of laser capture microdissection and our previously developed method for assaying the DNA methylation status of mouse 5-LOX (Dzitoyeva et al., 2009), we characterized DNA methylation of 5-LOX-high- vs. 5-LOX-low-expressing cerebellar samples.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

Male C57BL/6J mice (2 months old, weighing 25–30 g) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and were housed in a temperature controlled room on a 12 hr light/dark cycle. They had free access to laboratory chow and water. The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee.

In situ hybridization and immunofluorescence

Mice were killed by a lethal anesthesia followed by transcardial perfusion with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and fixation (4% formaldehyde). Cerebella were removed and postfixed overnight at 4°C. After cryoprotection with 30% sucrose in PBS at 4°C, the cerebella were cut into 30 μm coronal sections for subsequent in situ hybridization and immunofluorescence analyses. Briefly, free-floating sections were incubated for 30 min in 0.25% Triton X-100, digested with 5 μg/ml proteinase K (15 min at 37°C) and the enzymatic reaction was terminated by addition of 0.75% glycine. After a brief fixation with 4% formaldehyde, sections were acetylated in freshly prepared 0.25% acetic anhydride in 0.1 M triethanolamine for 15 min, pre-hybridized for 1 hr at 55°C in hybridization buffer [4x saline sodium citrate (SSC), 5mM EDTA pH 8, 250 μg/ml yeast tRNA, 250 μg/ml salmon sperm DNA, 1x Denhardt’s solution, 10% dextran sulfate, and 50% formamide], then incubated overnight at 55°C with 1 μg/ml sense or antisense digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled RNA probes in hybridization buffer. After two washes at 55°C in 4x SSC, 2x SSC, 0.2x SSC for 30 min, hybridized sections were blocked in blocking reagent (5% donkey serum with 0.25% Triton X-100) for 1 hr. Subsequently the hybridized sections were incubated with sheep anti-DIG antibody (1:1000, Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) overnight at 4°C, then with fluorescein-conjugated donkey anti-sheep secondary antibody (1:100, Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) for 1 hr. Sections were re-blocked again, incubated with mouse anti-calbindin 28-kDa protein (CaBP-28; 1:2000, Sigma), or mouse anti-S-100β (1:100, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) antibodies for 1 hr at room temperature. Samples were probed with the appropriate rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody for another 1 hr. For FLAP immunostaining, we used rabbit primary antibody (1:100, Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA) to allow for double-labeling with CaBP-28 or S-100β antibodies. Images of labeled sections were obtained with a computer-linked fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) equipped with a X20 objective lens (Plan-Neofluar, NA = 0.5, Carl Zeiss).

Laser capture microdissection

Coronal sections (30 μm thick) were cut at −20° C and mounted on PET-Membrane Slides (Leica, Bannockburn, IL). Sections were thawed at room temperature for 30 sec, washed briefly in diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water and stained with hematoxylin for 1 min, 0.1% NH4OH eosin solution for 30 sec, and dehydrated in a series of ethanol baths (30 sec in 75%, 95% and 100% ethanol). Immediately after dehydration, laser capture microdissection (LCM) was performed using a laser capture microscope (Leica). The Purkinje cell layers and molecular layers (approximately 2 mm2 tissue per animal; around 2500 Purkinje cells total) were selectively captured into caps of 0.5ml PCR tubes containing 30 μl RNA extraction buffer (for RNA, 1% triton-X100, 0.8% 2-mercaptoethanol in guanidine isothiocyanate solution) or 30 μl sample loading buffer (for protein Western blot assay, 50 mM tris pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 2% 2-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol, 0.2%0 bromophenol blue). Genomic DNA for the methylation assay was extracted using Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Quantitative 5-LOX mRNA assay

Total RNA was extracted using the TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. To eliminate possible DNA contamination, RNA samples were treated with a DNase reagent, DNA-free™ (Ambion, Inc., Austin, TX). Total RNA was reverse-transcribed with 200U of cloned Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus (M-MLV) reverse transcriptase (Gibco BRL, Carlsbad, CA). The quantitative PCR was performed in a Stratagene Mx3005P QPCR System (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) using Maxima™ SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Fermentas, Glen Burnie, MD) in a three-step cycling protocol as described by the manufacturer. The PCR results were normalized against the corresponding cyclophilin contents. Data are presented in units calculated as a coefficient of variation 2−[ΔCt (target) − ΔCt (input)] (Imbesi et al., 2009). Primers employed were 5-LOX: forward 5′-ATT GCC ATC CAG CTC AAC CAA ACC-3′, reverse 3′-TGG CGA TAC CAA ACA CCT CAG ACA-3′; cyclophilin: forward 5′-AGC ATA CAG GTC CTG GCA TCT TGT-3′, reverse 5′-AAA CGC TCC ATG GCT TCC ACA ATG-3′.

5-LOX DNA methylation assay

This assay was performed as previously described (Dzitoyeva et al., 2009). Briefly, multiple methylation-sensitive endonuclease recognition sites are located in the 300nt region upstream of the ATG translation start codon of the mouse ALOX5 gene (a putative promoter region). Restriction digest-quantitative PCR was utilized to characterize the CpG methylation rate of that region with the aid of four methylation-sensitive endonucleases: AciI (C↓CGC), BstUI (CG↓CG), HinP1I (G↓CGC), and HpaII (C↓CGG). In this assay the methylation-sensitive endonucleases digest only unmethylated recognition sites and are inactive on sites with methylated cytosines. Genomic DNA was extracted from LCM samples by the Genomoic DNA Purification Kit (Gentra) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration of DNA was measured with a NanoDrop Spectrophotometer (Fishersci). The extracted genomic DNA was subjected to a restriction digest with the above-noted methylation-sensitive endonucleases in a separate reaction for each endonuclease. To measure methylation levels, the following primers were used for PCR: forward 5−-AGA GAA GGA TGC GTT GGA AGG T-3−, reverse 5−-GAC TCC GGG CAA GTG AGT GCT-3−. These primers amplify a 238 nt region upstream from the first ATG translation start codon. This region contains two recognition sites for each endonuclease used in the assay. For the input control, a 394 nt region in the first intron was chosen and amplified with the following primers: forward 5−-TGA TGT GGC TGG CCT CTT ATG TGA-3−, reverse 5−-ACT GGG ACT GAG TGC AGG AAA TGT-3−. This region does not contain recognition sites for the selected methylation-sensitive endonucleases. PCR reactions with two different primer sets (target and input) were run in separate tubes and the coefficient of variation (CV) for the relative amount of target sequence was calculated and is reported in units (Dzitoyeva et al., 2009).

Quantitative Western blotting

Before boiling for 10 min, the LCM samples were quickly frozen/thawed five times. The proteins were loaded on 7.5% Tris-HCl gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Piscataway, NJ), and blocked by 5% non-fat milk in TBST buffer (Tris buffer saline Tween 20) for 1 hr, then incubated overnight at 4°C with mouse anti 5-LOX antibody (1:1000, BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA). Thereafter, the membranes were incubated with horseradish-peroxidase-linked secondary antibody (1:1000 Amersham). To normalize the signals for 5-LOX proteins, the corresponding signals obtained with an anti-β-actin antibody (1:2000, Sigma) were measured on the same membranes. An ECL plus Kit (Amersham) was used for band visualization. The intensity of the bands was quantified using the NIH ImageJ system.

Statistics

For statistical analysis, we used SPSS software (version 15.0). Data were expressed as the mean ± standard error mean (SEM), and analyzed by independent-samples t-test. The p<0.05 values were accepted as statistically significant.

RESULTS

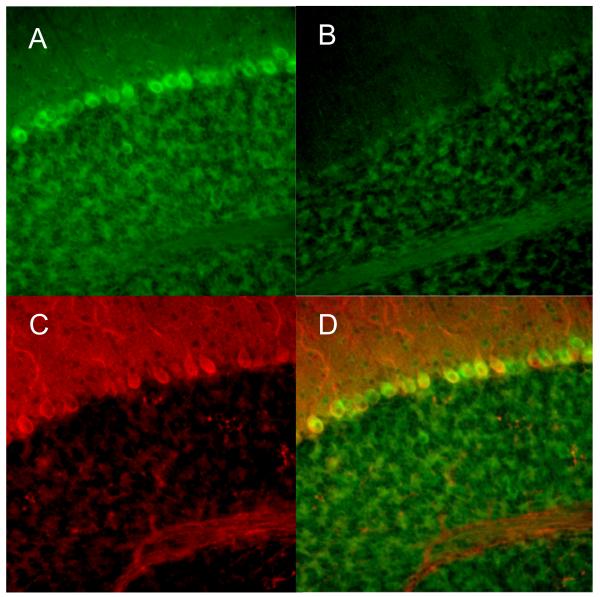

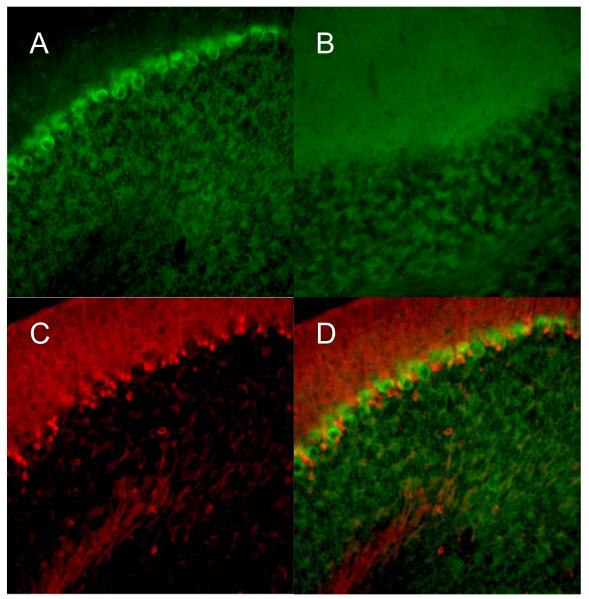

In pilot studies, while establishing the in situ hybridization conditions for assessing the localization of 5-LOX mRNA in cerebellar slices we noticed a peculiar localization of a specific signal in cell bodies suggestive of Purkinje cells. Hence, we set to characterize the localization of 5-LOX mRNA by using antibodies for two proteins, CaBP-28 and S-100β (Fig. 1). In the cerebellum, CaBP-28 is predominantly found in Purkinje cells (Celio, 1990; Fournet et al., 1986; Garcia-Segura et al., 1984), whereas S-100β is abundant in Purkinje cell-adjacent Bergmann glia (Landry et al., 1989; Lossi et al., 1995). Figure 1 shows that the cell-body-localized 5-LOX mRNA signal co-localizes with the CaBP-28 immunostaining. On the other hand, S-100β-specific immunostaining, which was found in the direct vicinity of cell bodies positive for the presence of 5-LOX mRNA, did not co-localize with the 5-LOX mRNA signal (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Double-labeling of 5-LOX mRNA and CaBP-28 (Purkinje cell marker) in mouse cerebellum. Cellular localization of 5-LOX mRNA was characterized by in situ hybridization using antisense (A, D) and sense (B, negative control) RNA probes. Note a strong green 5-LOX mRNA signal in the cell bodies in A and its absence in B. The red immunofluorescence of the Purkinje cell marker CaBP-28 is shown in C. Merging the 5-LOX/CaBP-28 immunofluorescences demonstrated the colocalization of the 5-LOX mRNA-specific signal and the Purkinje cell-specific signal (yellow, D). Images were obtained with a ×20 objective lens.

Fig. 2.

Double-labeling of 5-LOX mRNA and S-100β (marker of Bergmann glia) in mouse cerebellum. Panels A and D show the 5-LOX mRNA signal obtained with an antisense probe; panel B shows a negative control obtained with a sense probe. Panel C shows the red immunofluorescence of the Bergmann glia marker S-100β. Merging the 5-LOX/S-100β immunofluorescences demonstrated that the two signals do not overlap (D). Images were obtained with a ×20 objective lens.

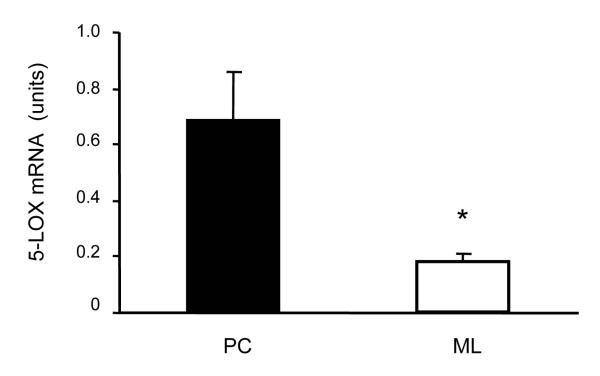

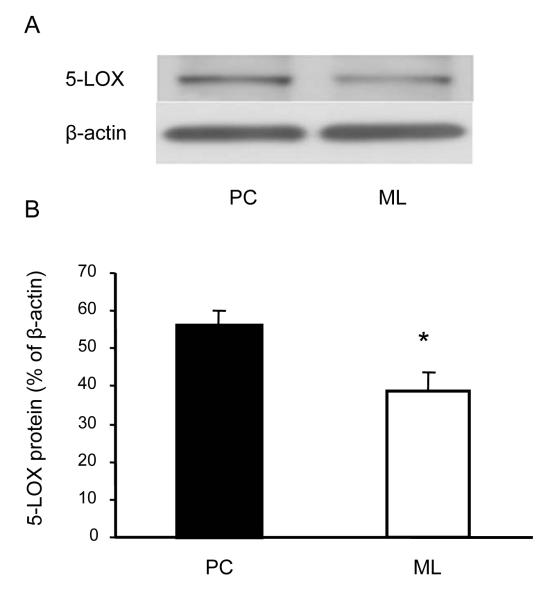

To further verify the 5-LOX-specificity of the Purkinje cell-localized 5-LOX signal, we used the LCM procedure to excise tissue from a 5-LOX-positive cerebellar area (i.e., Purkinje cells) and 5-LOX-negative area (i.e., the molecular cell layer) and we subjected these samples to quantitative 5-LOX mRNA and protein assays. Both 5-LOX mRNA content (Fig. 3) and 5-LOX protein content (Fig. 4) were significantly greater in the Purkinje cell samples compared to molecular cell layer samples.

Fig. 3.

5-LOX mRNA content of the Purkinje cell layer (PC) and the molecular layer (ML). The content of 5-LOX mRNA in the LCM cerebellar samples was measured by quantitative PCR (see text). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 5); *p<0.05 vs. PC.

Fig. 4.

5-LOX protein content in the Purkinje cell layer (PC) and the molecular layer (ML). The 5-LOX protein content in the LCM cerebellar samples was measured by quantitative Western blot using β-actin content as a control (an example is shown in panel A). The intensity of the 5-LOX signals was normalized by corresponding β-actin signals (B). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 5), *p<0.05 vs. PC.

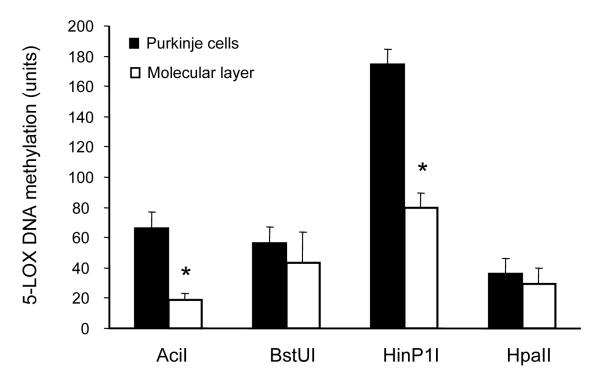

Previous studies of mouse 5-LOX DNA methylation with an assay based on the ability of methylation-sensitive endonucleases (i.e., AciI, BstUI, HinP1I, and HpaII) to digest only unmethylated recognition sites revealed a differential 5-LOX DNA methylation status in the cerebellum of young and old mice (Dzitoyeva et al., 2009). Using this methodology we found a differential 5-LOX DNA methylation status of the 5-LOX-high-expressing cerebellar area (i.e., Purkinje cells) compared to the 5-LOX-low-expressing area (i.e., the molecular cell layer) (Fig. 5). This difference was significant in the sites targeted by AciI and HinP1I but not BstUI and HpaII. In both DNA sites, the methylation levels were greater in Purkinje cell samples than in molecular cell layer samples (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

5-LOX DNA methylation levels in the Purkinje cell layer and the molecular layer. The assay of DNA methylation was performed in the LCM cerebellar samples by methylation-sensitive endonuclease assay using four endonucleases: AciI, BstUI, HinP1I, and HpaII. The results are reported in units (CV multiplied by a factor of 1000, see text for details) and are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 5), *p<0.001 vs. corresponding Purkinje cells.

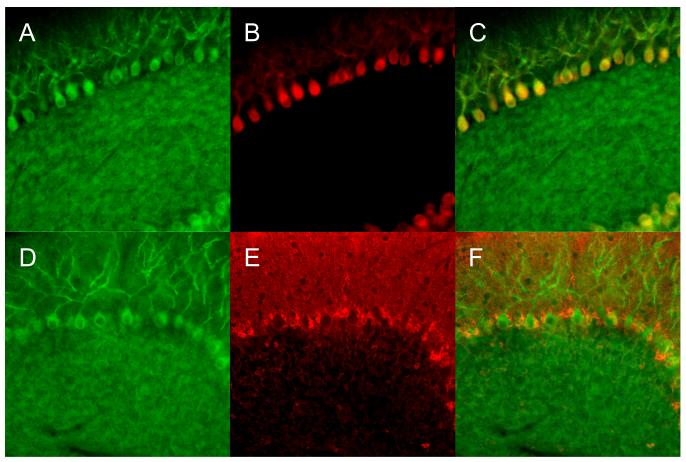

Although applicable for the Western blot assay (Fig. 4), the available anti-5-LOX antibodies that previously have been used for 5-LOX immunocytochemistry of human post-mortem brain samples (Ikonomovic et al., 2008) did not produce specific immunostaining in our mouse brain samples (data not shown). However, we found that an antibody against the FLAP protein, which is needed for a full 5-LOX enzymatic activity and is typically expressed in the cells containing 5-LOX, is present in Purkinje cells (Fig. 6). Similar to 5-LOX mRNA signal, FLAP immunoreactivity co-localized with a Purkinje cell marker (CaBP-28) (Fig. 6C) but did not co-localize with the immunoreactivity of the S-100β protein (Fig. 6F).

Fig. 6.

FLAP immunoreactivity in the cerebellum; colocalization with the immunoreactivities of CaBP-28 and S-100β. Panels A-C show double-labeling of FLAP (A, green) and the Purkinje cell marker CaBP-28 (B, red); merging of both immunofluorescences demonstrated the FLAP/CaBP-28 colocalization (C, yellow). Panels D-F show double-labeling of FLAP (D, green) and the Bergmann glia marker S-100β (E, red); merging of both immunofluorescences demonstrated that the two signals do not overlap (F). Images were obtained with a ×20 objective lens.

DISCUSSION

Our characterization of the cells positive for the 5-LOX mRNA in situ hybridization signal and FLAP immunoreactivity revealed that both these signals co-localize with CaBP-28 immunoreactivity but not with S-100β immunoreactivity. Considering the known specificity of the CaBP-28 marker for Purkinje cells in the cerebellum (Celio, 1990; Fournet et al., 1986; Garcia-Segura et al., 1984) and the selectivty of the S-100β marker for cerebellar Bergmann glia (Landry et al., 1989; Lossi et al., 1995) the results suggest that the 5-LOX pathway is expressed in the Purkinje cells. These findings complement and extend previous reports on the cerebellar expression of 5-LOX and/or FLAP (Chinnici et al., 2007; Dzitoyeva et al., 2009; Lammers et al., 1996; Zhang et al., 2006). Hence, we demonstrated that in the adult mouse cerebellum the two key enzymes of the 5-LOX pathway, 5-LOX and FLAP, are selectively expressed in Purkinje cells. At the protein level, we were able to confirm the Purkinje cell abundance of 5-LOX expression using the Western blot assay; the source of the 5-LOX protein signal observed in the molecular layer may be in the Purkinje cell dendrites. Due to species differences in the applicability of antibodies for the immunocytochemistry, we were not able to use the commercially available anti-5-LOX antibodies for immunocytochemistry of mouse cerebellar sections. However, in studies with human cerebellar sections, it was demonstrated that 5-LOX immunoreactivity was only moderately expressed in molecular layer neurons and in granular cells but that it was highly expressed in the cytosol of Purkinje cells (Zhang et al., 2006).

Among the factors that determine the tissue and/or cell specificity of gene expression are the epigenetic modifications of DNA via DNA-methylation mechanisms (Futscher et al., 2002). Although the mouse 5-LOX DNA sequence lacks the typical CpG islands found in the human DNA sequence (Kartyniok et al., 2010), its methylation status is susceptible to modifications, for example during aging. Thus, 5-LOX DNA methylation in the mouse cerebellum increases with aging in the sites targeted by AciI and BstUI but not HinP1I and HpaII (Dzitoyeva et al., 2009). In this study, we found that methylation in the sites targeted by AciI and HinP1I but not by BstUI and HpaII was greater in high-5-LOX-expressing cerebellar samples (Purkinje cells) vs. the low-5-LOX-expressing samples (the molecular cell layer). Collectively, these and previously published data point to a relatively high susceptibility of the AciI-targeted sites and relatively high resistance of the HpaII-targeted sites of a putative mouse 5-LOX promoter to methylation modifications. Furthermore, the increased methylation of AciI-targeted sites in the cerebellum was associated with increased levels of 5-LOX mRNA; e.g., during aging (Dzitoyeva et al., 2009) and in Purkinje cells (this study). The functional relevance of methylation changes in these non-island CpGs requires further study. Nevertheless, it has been reported that tissue-dependent methylated regions can be disproportionately distributed in non-island CpG loci, which were located not only in the 5′ regions of genes but also in intronic and non-genic regions (Sakamoto et al., 2007).

In this work, we did not measure the capability of the cerebellar 5-LOX pathway to generate 5-LOX metabolites, leukotrienes. However, recent studies with mouse cerebellar tissue samples demonstrate that the cerebellum produces measurable amounts of leukotriene LTB4 (Chinnici et al., 2007). In light of our present findings, it is likely that Purkinje cells are a major contributor to this leukotriene synthesis. Their contribution could be such that the entire metabolic process takes place in Purkinje cells or alternatively, they could provide the intermediate metabolites for a transcellular biosynthesis of cerebellar leukotrienes (Farias et al., 2007).

Previous work has demonstrated that mouse cerebellar Purkinje cells express a number of enzymes involved in the synthesis and degradation of endovanilloids (Cristino et al., 2008). Based on these findings, the authors proposed that Purkinje cells are “endovanillergic” brain neurons, in which endogenously-generated lipid molecules act as intracellular mediators at the transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1). Also 5-LOX metabolites, e.g., 5-(S)-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (5-HPETEs) and leukotriene LTB4 act as endovanilloids (De Petrocellis and Di Marzo, 2005). Furthermore, both LTB4 receptors and TRPV1 receptors are known to be capable of interacting with the same type of molecules (McHugh et al., 2006). Hence, our findings of the Purkinje cell-predominant expression of 5-LOX and FLAP provide additional support to the hypothesis of the “endovanillergic” nature of cerebellar Purkinje cells. Alternatively, the Purkinje cell-selective localization of 5-LOX and FLAP in the cerebellum may be related to the previously reported effects of the 5-LOX metabolite, leukotriene C1, on the excitability of Purkinje cells; this leukotriene elicits a prolonged excitation of Purkinje neurons (Palmer et al., 1980).

Finally, it is possible that 5-LOX protein exerts biological effects in the cerebellum via its non-enzymatic actions. For example, it has been shown that 5-LOX binds the C-terminus of the human Dicer and that this protein-protein interaction occurs in a specific 5-LOX binding domain of Dicer (Dincbas-Renqvist et al., 2009). Dicer is an endoribonuclease critical for the production of small interfering RNAs (siRNA) and involved in microRNA regulation of synaptic plasticity (Smalheiser and Lugli, 2009). As a result of 5-LOX binding, the microRNA precursor processing activity of Dicer is significantly altered (Dincbas-Renqvist et al., 2009). In the cerebellum, a key physiological role for Dicer and microRNAs has been demonstrated in Purkinje cells; a conditional Purkinje cell-specific ablation of Dicer leads to a progressive loss of microRNAs and ultimately to Purkinje cell death (Schaefer et al., 2007). The relevance of this putative mechanism of 5-LOX action for neurodegenerative disorders, e.g., cerebellar ataxia, needs further elucidation.

CONCLUSION

The main finding in this work is that in the mouse cerebellum, the key proteins of the 5-LOX pathway, 5-LOX and FLAP, are predominantly expressed in Purkinje cells. Purkinje cell-selective 5-LOX expression is accompanied by a differential pattern of DNA methylation in the region of the putative mouse 5-LOX promoter. This Purkinje cell-localized 5-LOX expression may be involved in cerebellar synthesis of leukotrienes and/or could influence the Dicer-mediated processes of neuroplasticity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging R01AG015347-05A2 (H.M.).

List of abbreviations

- CaBP-28

calbindin 28-kDa protein

- CNS

central nervous system

- DEPC

diethylpyrocarbonate

- DIG

digoxigenin

- FLAP

5-lipoxygenase activating protein

- 5-HPETEs

5-(S)-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids

- LCM

laser capture microdissection

- 5-LOX

5-lipoxygenase

- LTB4

leukotriene B4

- M-MLV

Moloney murine leukemia virus

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- SEM

standard error mean

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- SSC

saline sodium citrate

- TRPV1

transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Bijlsma MF, Peppelenbosch MP, Spek CA, Roelink H. Leukotriene synthesis is required for hedgehog-dependent neurite projection in neuralized embryoid bodies but not for motor neuron differentiation. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1138–1145. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celio MR. Calbindin D-28k and parvalbumin in the rat nervous system. Neuroscience. 1990;35:375–475. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90091-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnici CM, Yao Y, Praticò D. The 5-lipoxygenase enzymatic pathway in the mouse brain: young versus old. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:1457–1462. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu J, Praticò D. The 5-lipoxygenase as a common pathway for pathological brain and vascular aging. Cardiovasc Psychiatry Neurol. 2009;2009:174657. doi: 10.1155/2009/174657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristino L, Starowicz K, De Petrocellis L, Morishita J, Ueda N, Guglielmotti V, Di Marzo V. Immunohistochemical localization of anabolic and catabolic enzymes for anandamide and other putative endovanilloids in the hippocampus and cerebellar cortex of the mouse brain. Neuroscience. 2008;151:955–968. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Petrocellis L, Di Marzo V. Lipids as regulators of the activity of transient receptor potential type V1 (TRPV1) channels. Life Sci. 2005;77:1651–1666. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dincbas-Renqvist V, Pépin G, Rakonjac M, Plante I, Ouellet DL, Hermansson A, Goulet I, Doucet J, Samuelsson B, Rådmark O, Provost P. Human Dicer C-terminus functions as a 5-lipoxygenase binding domain. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1789:99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzitoyeva S, Imbesi M, Ng LW, Manev H. 5-Lipoxygenase DNA methylation and mRNA content in the brain and heart of young and old mice. Neural Plast. 2009;2009:209596. doi: 10.1155/2009/209596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournet N, Garcia-Segura LM, Norman AW, Orci L. Selective localization of calcium-binding protein in human brainstem, cerebellum and spinal cord. Brain Res. 1986;399:310–316. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91521-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futscher BW, Oshiro MM, Wozniak RJ, Holtan N, Hanigan CL, Duan H, Domann FE. Role for DNA methylation in the control of cell type specific maspin expression. Nat Genet. 2002;31:175–179. doi: 10.1038/ng886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Segura LM, Baetens D, Roth J, Norman AW, Orci L. Immunohistochemical mapping of calcium-binding protein immunoreactivity in the rat central nervous system. Brain Res. 1984;296:75–86. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90512-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikonomovic MD, Abrahamson EE, Uz T, Manev H, Dekosky ST. Increased 5-lipoxygenase immunoreactivity in the hippocampus of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Histochem Cytochem. 2008;56:1065–1073. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2008.951855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imbesi M, Dzitoyeva S, Ng LW, Manev H. 5-Lipoxygenase and epigenetic DNA methylation in aging cultures of cerebellar granule cells. Neuroscience. 2009;164:1531–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katryniok C, Schnur N, Gillis A, von Knethen A, Sorg BL, Looijenga L, Rådmark O, Steinhilber D. Role of DNA methylation and methyl-DNA binding proteins in the repression of 5-lipoxygenase promoter activity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammers CH, Schweitzer P, Facchinetti P, Arrang JM, Madamba SG, Siggins GR, Piomelli D. Arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase and its activating protein: prominent hippocampal expression and role in somatostatin signaling. J Neurochem. 1996;66:147–152. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66010147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry CF, Ivy GO, Dunn RJ, Marks A, Brown IR. Expression of the gene encoding the beta-subunit of S-100 protein in the developing rat brain analyzed by in situ hybridization. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1989;6:251–262. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(89)90071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren JA, Hökfelt T, Dahlén SE, Patrono C, Samuelsson B. Leukotrienes in the rat central nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:6212–6216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.19.6212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lossi L, Ghidella S, Marroni P, Merighi A. The neurochemical maturation of the rabbit cerebellum. J Anat. 1995;187:709–722. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh D, McMaster RS, Pertwee RG, Roy S, Mahadevan A, Razdan RK, Ross RA. Novel compounds that interact with both leukotriene B4 receptors and vanilloid TRPV1 receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:955–965. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.095992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto T, Lindgren JA, Hökfelt T, Samuelsson B. Regional distribution of leukotriene and mono-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid production in the rat brain. Highest leukotriene C4 formation in the hypothalamus. FEBS Lett. 1987;216:123–127. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80769-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakes CC, La Salle S, Smiraglia DJ, Robaire B, Trasler JM. A unique configuration of genome-wide DNA methylation patterns in the testis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:228–233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607521104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuki T, Matsumoto M, Hayashi Y, Yamamoto K, Kitagawa K, Ogawa S, Yamamoto S, Kamada T. Reperfusion induces 5-lipoxygenase translocation and leukotriene C4 production in ischemic brain. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:H1249–H1257. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.3.H1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer MR, Mathews R, Murphy RC, Hoffer BJ. Leukotriene C elicits a prolonged excitation of cerebellar Purkinje neurons. Neurosci Lett. 1980;18:173–180. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(80)90322-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rådmark O, Werz O, Steinhilber D, Samuelsson B. 5-Lipoxygenase: regulation of expression and enzyme activity. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:332–341. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto H, Suzuki M, Abe T, Hosoyama T, Himeno E, Tanaka S, Greally JM, Hattori N, Yagi S, Shiota K. Cell type-specific methylation profiles occurring disproportionately in CpG-less regions that delineate developmental similarity. Genes Cells. 2007;12:1123–1132. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer A, O’Carroll D, Tan CL, Hillman D, Sugimori M, Llinas R, Greengard P. Cerebellar neurodegeneration in the absence of microRNAs. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1553–1558. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serhan CN, Yacoubian Y, Yang R. Anti-inflammatory and proresolving lipid mediators. Annu Rev Pathology. 2008;3:279–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.151409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smalheiser NR, Lugli G. microRNA regulation of synaptic plasticity. Neuromolecular Med. 2009;11:133–140. doi: 10.1007/s12017-009-8065-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhl J, Klan N, Rose M, Entian KD, Werz O, Steinhilber D. The 5-lipoxygenase promoter is regulated by DNA methylation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:4374–4379. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107665200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhl J, Klan N, Rose M, Entian KD, Werz O, Steinhilber D. DNA methylation regulates 5-lipoxygenase promoter activity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;525:169–172. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-9194-2_35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uz T, Manev R, Manev H. 5-Lipoxygenase is required for proliferation of immature cerebellar granule neurons in vitro. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;418:15–22. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)00924-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vikman S, Brena RM, Armstrong P, Hartiala J, Stephensen CB, Allayee H. Functional analysis of 5-lipoxygenase promoter repeat variants. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:4521–4529. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada K, Arita M, Nakajima A, Katayama K, Kudo C, Kamisaki Y, Serhan CN. Leukotriene B4 and lipoxin A4 are regulatory signals for neural stem cell proliferation and differentiation. FASEB J. 2006;20:1785–1792. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-5809com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Zhang WP, Hu H, Wang ML, Sheng WW, Yao HT, Ding W, Chen Z, Wei EQ. Expression patterns of 5-lipoxygenase in human brain with traumatic injury and astrocytoma. Neuropathology. 2006;26:99–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2006.00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Chen CQ, Manev H. DNA methylation as an epigenetic regulator of neural 5-lipoxygenase expression: evidence in human NT2 and NT2-N cells. J Neurochem. 2004;88:1424–1430. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]