Abstract

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is an important clinical problem in the chronic kidney disease (CKD) population. OSA is associated with hypoxemia and sleep fragmentation, which activates the sympathetic nervous system, the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, alters cardiovascular hemodynamics, and results in free radical generation. In turn, a variety of deleterious processes such as endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, platelet aggregation, atherosclerosis, and fibrosis are triggered, predisposing individuals to adverse cardiovascular events and likely renal damage. Independent of obesity, OSA is associated with glomerular hyperfiltration and may be an independent predictor of proteinuria, a risk factor for CKD progression. OSA is also associated with hypertension, another important risk factor for CKD progression, particularly proteinuric CKD. OSA may mediate renal damage via several mechanisms, and there is a need to better elucidate the impact of OSA on incident renal disease and CKD progression.

Keywords: Obstructive sleep apnea, Chronic kidney disease, Proteinuria, Hypertension

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a growing problem in the United States with important negative health implications. In addition to substantial morbidity, as evidenced by increased health services utilization [1], reduced functional capabilities, and lower quality of life [2], OSA has also been associated with increased mortality [3]. OSA has been independently associated with cardiovascular diseases, including hypertension [4], coronary heart disease, heart failure, and stroke [5]. Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain this excess cardiovascular risk among individuals with OSA, including hypoxemia-induced endothelial dysfunction, accelerated atherosclerosis, and altered cardiovascular hemodynamics. Each of these factors can have a deleterious impact on renal function; thus, it is not surprising that OSA is a common clinical problem for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Although data are limited, OSA appears to alter renal hemodynamics and function in a harmful manner. This review will explore the impact of OSA on renal function and the mechanisms by which OSA may lead to CKD progression.

Definition

OSA is characterized by transient, repetitive partial or complete upper airway obstruction during sleep causing sleep disturbances, intermittent hypoxemia, and daytime sleepiness. An obstructive apnea is defined as a ≥10-second pause in respiration associated with ongoing ventilatory effort [6]. Obstructive hypopneas, conversely, are marked by a partial decrement in ventilation with an associated fall in oxygen saturation or arousal despite ongoing ventilatory effort. The average number of apneas and hypopneas per hour of sleep, as measured during polysomnography, comprises the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI). OSA is present when the AHI is ≥5 events per hour. The AHI can also be used to grade the severity of OSA or to monitor response to therapy.

Symptoms

A history of excessive daytime hypersomnolence can often be elicited from patients with OSA. Characteristically, daytime hypersomnolence occurs despite seemingly appropriate sleep duration due to diminished sleep quality. Specifically, sleep architecture is disrupted such that there are reductions in rapid eye movement sleep accompanied by frequent arousals [7]. There may be snoring and/or apneic events during sleep that patients may not be aware of, but these events may be witnessed by sleep partners. Other symptoms such as fatigue, difficulty concentrating, and headaches may also be present [7]. Symptom onset is often insidious, and a careful history is necessary to identify these symptoms.

Risk Factors for OSA

Age, male gender, and obesity—particularly neck circumference and central adiposity—are important risk factors for OSA [8]. Abnormalities of the upper airway are common among individuals with OSA, including large tonsils, retrognathia, and narrow airways [7].

Prevalence

It is estimated that approximately 2% of women and 4% of men in the middle-aged work force meet the minimal diagnostic criteria for the sleep apnea syndrome (an AHI score of 5 or higher and daytime hypersomnolence). Moderately severe OSA, defined as an AHI ≥15 events per hour, occurs in 9% of middle-aged men and in 4% of women in the United States [9]. However, some studies suggest that the prevalence may be significantly higher. For instance, in one study, the estimated prevalence of OSA—defined as an AHI of 5 events per hour or higher—was 9% for women and 24% for men [9]. It is worth noting that the majority (>85%) of patients with clinically significant and treatable OSA have never been diagnosed [10].

No population-based estimates of OSA prevalence exist; however, there is evidence that it may disproportionately impact patients with CKD [11•, 12–14]. In a cross-sectional study of 35 patients with CKD, Markou et al. [15] found that the majority of patients studied (54%) had sleep apnea. In a cross-sectional study of participants in a private health care plan, Sim et al. [11•] found an increased risk of sleep apnea in patients with mild glomerular filtration rate (GFR) loss. Compared to those with normal kidney function, defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2, the odds ratios for sleep apnea for eGFR strata 75 to 89, 60 to 74, 45 to 59, 30 to 44, and 15 to 29 mL/min/1.73 m2 were 1.25 (95% CI, 1.21–1.28), 1.32 (95% CI, 1.28–1.37), 1.29 (95% CI, 1.23–1.36), 1.07 (95% CI, 0.98–1.18), and 0.92 (95% CI, 0.78–1.07), respectively, after adjusting for age, sex, diabetes, coronary heart disease, and number of visits. However, it is worth noting that the eGFR—as determined by the abbreviated Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Equation—is less reliable at eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2, introducing potential misclassification bias.

OSA in CKD

OSA is exceedingly common among individuals with end-stage renal disease, affecting an estimated 50% of patients [16]. Treatment with intensive dialysis therapies, such as nocturnal dialysis, appears to decrease the frequency of apneic events [16]. Markers of renal function, including serum urea concentration and creatinine clearance, also have been associated with OSA in CKD cohorts not receiving renal replacement therapy. Markou et al. [15] conducted a cross-sectional cohort study of 35 individuals with stable CKD, defined by a creatinine clearance less than 40 mL/min. AHI correlated with urea concentration (r=0.35, P=0.037), but interestingly, not creatinine clearance (r=−0.12, P=0.506). After excluding diabetic patients, Markou et al. found [15] that urea became an even stronger predictor of AHI (r=0.608, P=0.001), and a statistically significant relationship between creatinine clearance and AHI emerged (r=−0.5, P=0.012). An important limitation of this study is the small sample size and absence of a control group.

In a study of obese adults, increasing severity of OSA was associated with higher serum creatinine [17]. In a cross-sectional study of 158 individuals with suspected OSA, Fleischmann et al. [18•] found that stage 3 CKD (defined as an eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2) was a statistically significant predictor of central sleep apnea events but not OSA events. Thus, there may be an association between renal function and sleep apnea. However, data are limited by small sample size and selection bias because study participants were drawn from individuals with suspected OSA.

OSA and Renal Hemodynamics

Although it is known that obesity, a risk factor for OSA, is associated with glomerular hyperfiltration, the impact of OSA on renal hemodynamics has been less studied. Kinebuchi et al. [19] assessed renal hemodynamics before and after institution of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy in a series of patients with OSA. There was no significant change in GFR, but renal plasma flow increased significantly from 476 mL/min prior to treatment to 563 mL/min after CPAP treatment (P<0.05). Filtration fraction decreased significantly from 0.26 to 0.23 after CPAP treatment (P<0.001), suggesting that CPAP results in decreased hyperfiltration. Interestingly, this effect was not seen in individuals on angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers. One of the limitations of this study was the control group selected for this study was comprised of individuals with a significantly lower body mass index (BMI) than those with OSA, making it difficult to make any inferences about the differential contribution of obesity and OSA, if any, on renal hemodynamics. Nonetheless, participants functioned as their own controls in the CPAP arm of the study. The chronic effects of CPAP on renal hemodynamics and renal function were not explored in this study [19].

OSA and Proteinuria

OSA has been linked to proteinuria, a manifestation of renal disease and a risk factor for CKD progression to end-stage renal disease. A few studies have attempted to tease apart the obesity-independent contribution of OSA as a predictor of proteinuria [20]. Obesity is known to cause hyperfiltration, glomerulomegaly, and subsequent proteinuria. The predominant pathologic correlate of obesity-associated proteinuria is focal glomerulosclerosis [21]. Chaudhary et al. [22] described nephrotic range proteinuria in 6 of 34 cases of OSA but not in controls matched for sex, age, and weight. There was no statistically significant difference in low-grade proteinuria, with rates of 47% and 29% among cases and controls, respectively. The authors went on to report improvements in proteinuria after surgical treatment for OSA in the four patients for whom follow-up data was available, with complete resolution of nephrotic-range proteinuria in three patients and marked reduction in proteinuria in the fourth patient [22]. Sklar et al. [23] also reported improvement in proteinuria in a small case series of patients with OSA, improving from 1.7 to 2.7 grams of proteinuria per day prior to OSA therapy to 0.2 to 0.6 grams per day of proteinuria after instituting OSA therapy.

In a prospective, non-CKD cohort of individuals with OSA, Faulx et al. [24] reported that increased AHI greater than 30 compared with less than 5 was associated with microalbuminuria in multivariate modeling that adjusted for BMI and GFR. This relationship was still present when individuals with CKD (eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2) were excluded from the analysis [24]. The degree of microalbuminuria was relatively small, and may be indicative of endothelial dysfunction rather than primary renal impairment. However, the presence of microalbuminuria has not been a universal finding. Agrawal et al. [17] performed a cross-sectional study of 91 obese individuals who underwent polysomnography. They found that albuminuria was similar among those with OSA compared to those without. Casserly et al. [20] also conducted a cross-sectional study in which OSA was not an independent predictor of proteinuria after adjusting for BMI. Thus, although there seems to be an association between OSA and proteinuria, it is yet unclear if it is independent of BMI.

OSA and Hypertension

The impact of OSA on incident and/or resistant hypertension may have negative consequences for CKD progression. Evidence of a causal link between OSA and hypertension comes from results from the prospective Wisconsin Sleep Cohort, which is comprised of approximately 1,200 individuals at the baseline visit, recruited from among employees of several Wisconsin state agencies. Analysis of the 709 individuals for whom 4-year follow-up data were available revealed that OSA was associated with incident hypertension, independent of age or BMI [25]. In addition, a dose-response relationship between severity of OSA and hypertension was found. An association between pulse wave velocity (PWV) and AHI has been described cross-sectionally [26]. PWV is a measure of arterial wall stiffness, a nonatherosclerotic surrogate marker that identifies individuals at high risk for cardiovascular disease events [27, 28]. Further, severe OSA and hypertension were associated with arterial stiffness and increased left ventricular mass index of similar magnitude, with additive effects when both conditions coexist [26].

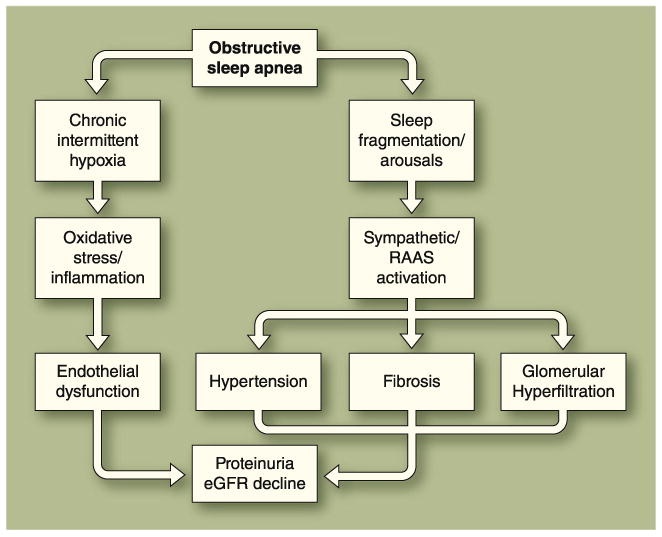

Animal models suggest that chronic hypoxemia induces sympathetic nervous system outflow and subsequently increased vascular resistance [29•]. Chemoreflex-mediated increases in sympathetic activity also trigger a neurohormonal response with activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, driving hypertension. In addition to the impact on blood pressure homeostasis, aldosterone has been linked to fibrosis and renal damage (Fig. 1). Greene et al. [30] demonstrated that aldosterone was the etiologic agent in glomerular sclerosis in the remnant kidney model in rats, with subsequent studies showing that this process could be reversed with aldosterone blockade [31]. Patients with OSA appear to have increased aldosterone, placing them at risk for glomerular sclerosis. In a study of patients referred for evaluation of resistant hypertension, individuals with a high risk of sleep apnea based on the Berlin questionnaire were noted to have a significantly higher rate of aldosterone excretion and were almost twice as likely to have primary hyperaldosteronism [32]. In a case-control study of patients with resistant hypertension, not only was OSA very common, but the authors found that AHI correlated with plasma aldosterone [33]. However, we found no studies evaluating the role of aldosterone and OSA in CKD cohorts. Further, the literature is significant limited by the lack of prospective studies.

Fig. 1.

Pathophysiologic links between obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and chronic kidney disease (CKD). The most direct mechanism by which long-standing OSA might contribute to CKD progression is by inducing chronic elevations in blood pressure. OSA could further contribute to the CKD progression by increasing sympathetic nerve discharge directed at the kidney and other vascular beds, raising blood pressure during episodes of upper airway occlusion, and chronically accelerating the progression of renal damage, with sustained elevations in blood pressure during the awake state [47, 48]. OSA has also been linked to glomerular hyperfiltration [19]. Whether OSA is an independent predictor of proteinuria is controversial [49, 50]. eGFR—estimated glomerular filtration rate; RAAS—renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system

OSA-associated hypertension is particularly important because hypertension is an important risk factor for CKD progression, particularly in proteinuric CKD [34]. Treatment of OSA offers an opportunity to mitigate ultimately maladaptive changes in blood pressure homeostasis. CPAP is clearly associated with improvement in nighttime blood pressure [29•]. It appears that daytime blood pressure is also improved, although there are some conflicting reports in this regard. If OSA management results in improved blood pressure control, it is possible that patients with CKD stand to benefit with improved renal survival.

Atherosclerosis and Endothelial Dysfunction

OSA is associated with several cardiovascular conditions including ischemic heart disease, congestive heart failure, cardiac arrhythmias, and cerebrovascular disease [35, 36]. The Sleep Heart Health Study noted cross-sectionally that hypopneas accompanied by oxyhemoglobin desaturation of ≥4% were independently associated with prevalent cardiovascular disease [37]. OSA may also be implicated in incident atherosclerosis. Recently, an animal model was used to demonstrate de novo atherosclerotic plaques generation in mice on both high-fat diet and chronic intermittent hypoxia [29•].

A recent American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation Scientific Statement highlights the concepts and evidence important to understanding the interactions between sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease [38]. The apneas/ hypopneas and associated hypoxemia contribute to increased sympathetic activity, alter the renin-angiotensin system, impede xanthine oxidoreductase production, and cause endothelial dysfunction [39].

Hypoxemia-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) and systemic inflammation as seen in OSA contribute to atherosclerosis and may also contribute to CKD progression (Fig. 1). OSA-mediated hypoxemia is thought to produce an ischemic-reperfusion injury, which is associated with ROS. ROS are generated through both NADPH and xanthine oxidase pathways. ROS are also associated with proinflammatory mediators. For instance, nuclear factor-κB is upregulated, initiating a cascade of events that leads to leukocyte recruitment. Cytokines tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 are also increased [40]. In addition, increased platelet aggregability, insulin resistance, and metabolic dysregulation appear to be involved. These same factors are implicated in the initiation and progression of kidney disease. Interestingly, CPAP therapy improves endothelial function [41], decreases the abnormally increased levels of circulating apoptotic endothelial cells [42], attenuates free radical production from neutrophils [43], decreases inflammatory mediators [44], increases vasodilator levels [45], and mediates a decline in vasoconstrictor levels in patients with sleep apnea [46]. Presumably, CPAP treatment would mitigate renal injury [44].

Conclusions

OSA is an important health problem in the United States with critical physiologic changes. OSA is associated with proteinuria and hypertension, which in turn are associated with adverse renal outcomes. It is also plausible that OSA therapy may improve renal outcomes. OSA is a treatable condition; therefore, additional studies are necessary to better define the role of OSA in renal injury and to identify ways of improving both renal and cardiovascular outcomes in CKD cohorts.

Acknowledgments

Gbemisola A. Adeseun received salary support from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Supplement to the parent grant # 5R01D080033-02 (SER). Dr Rosas's research lab is supported by VA Merit IIR 05-247, R01 DK 80033 and R21 HL 86971.

Contributor Information

Gbemisola A. Adeseun, Renal, Electrolyte and Hypertension Division, Department of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Sylvia E. Rosas, Email: Sylvia.rosas@uphs.upenn.edu, Renal, Electrolyte and Hypertension Division, Department of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA; Philadelphia Veterans Administration Medical Center, First floor Founders Building, 3400 Spruce Street, Philadelphia, PA, USA

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

- 1.Kapur VK, Redline S, Nieto FJ, et al. The relationship between chronically disrupted sleep and healthcare use. Sleep. 2002;25:289–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foley DJ, Monjan A, Simonsick EM, et al. Incidence and remission of insomnia among elderly adults: an epidemiologic study of 6,800 persons over three years. Sleep. 1999;22(Suppl 2):S366–S372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.He J, Kryger MH, Zorick FJ, et al. Mortality and apnea index in obstructive sleep apnea. Experience in 385 male patients. Chest. 1988;94:9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nieto FJ, Young TB, Lind BK, et al. Association of sleep-disordered breathing, sleep apnea, and hypertension in a large community-based study. Sleep Heart Health Study. JAMA. 2000;283:1829–1836. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.14.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shahar E, Whitney CW, Redline S, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular disease: cross-sectional results of the Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:19–25. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.1.2001008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults: recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research. The Report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force. Sleep. 1999;22:667–689. no authors listed. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuhlmann U, Bormann FG, Becker HF. Obstructive sleep apnoea: clinical signs, diagnosis and treatment. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:8–14. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young T, Skatrud J, Peppard PE. Risk factors for obstructive sleep apnea in adults. JAMA. 2004;291:2013–2016. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.16.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, et al. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230–1235. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Young T, Evans L, Finn L, Palta M. Estimation of the clinically diagnosed proportion of sleep apnea syndrome in middle-aged men and women. Sleep. 1997;20:705–706. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.9.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11•.Sim JJ, Rasgon SA, Kujubu DA, et al. Sleep apnea in early and advanced chronic kidney disease: Kaiser Permanente Southern California cohort. Chest. 2009;135:710–716. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is an important article that explores that relationship between OSA and early CKD.

- 12.Hanly P. Sleep apnea and daytime sleepiness in end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2004;17:109–114. doi: 10.1111/j.0894-0959.2004.17206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shayamsunder AK, Patel SS, Jain V, et al. Sleepiness, sleeplessness, and pain in end-stage renal disease: distressing symptoms for patients. Semin Dial. 2005;18:109–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2005.18218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Unruh ML, Sanders MH, Redline S, et al. Sleep apnea in patients on conventional thrice-weekly hemodialysis: comparison with matched controls from the Sleep Heart Health Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:3503–3509. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006060659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Markou N, Kanakaki M, Myrianthefs P, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing in nondialyzed patients with chronic renal failure. Lung. 2006;184:43–49. doi: 10.1007/s00408-005-2563-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Unruh ML. Sleep apnea and dialysis therapies: things that go bump in the night? Hemodial Int. 2007;11:369–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2007.00203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agrawal V, Vanhecke TE, Rai B, et al. Albuminuria and renal function in obese adults evaluated for obstructive sleep apnea. Nephron Clin Pract. 2009;113:c140–c147. doi: 10.1159/000232594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18•.Fleischmann G, Fillafer G, Matterer H, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in patients with suspected sleep apnoea. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:181–186. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is a recent study that examines the epidemiology of CKD among individuals with OSA.

- 19.Kinebuchi S, Kazama JJ, Satoh M, et al. Short-term use of continuous positive airway pressure ameliorates glomerular hyperfiltration in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Clin Sci (Lond) 2004;107:317–322. doi: 10.1042/CS20040074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Casserly LF, Chow N, Ali S, et al. Proteinuria in obstructive sleep apnea. Kidney Int. 2001;60:1484–1489. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serra A, Romero R, Lopez D, et al. Renal injury in the extremely obese patients with normal renal function. Kidney Int. 2008;73:947–955. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chaudhary BA, Sklar AH, Chaudhary TK, et al. Sleep apnea, proteinuria, and nephrotic syndrome. Sleep. 1988;11:69–74. doi: 10.1093/sleep/11.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sklar AH, Chaudhary BA. Reversible proteinuria in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:87–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faulx MD, Storfer-Isser A, Kirchner HL, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea is associated with increased urinary albumin excretion. Sleep. 2007;30:923–929. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.7.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Skatrud J. Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1378–1384. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005113421901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drager LF, Bortolotto LA, Figueiredo AC, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, and their interaction on arterial stiffness and heart remodeling. Chest. 2007;131:1379–1386. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blacher J, Asmar R, Djane S, et al. Aortic pulse wave velocity as a marker of cardiovascular risk in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 1999;33:1111–1117. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.5.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meaume S, Benetos A, Henry OF, et al. Aortic pulse wave velocity predicts cardiovascular mortality in subjects >70 years of age. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:2046–2050. doi: 10.1161/hq1201.100226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29•.Dempsey JA, Veasey SC, Morgan BJ, O'Donnell CP. Pathophysiology of sleep apnea. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:47–112. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is an excellent review of the pathophysiology of OSA, with an emphasis on the cardiovascular consequences of OSA.

- 30.Greene EL, Kren S, Hostetter TH. Role of aldosterone in the remnant kidney model in the rat. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1063–1068. doi: 10.1172/JCI118867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aldigier JC, Kanjanbuch T, Ma LJ, et al. Regression of existing glomerulosclerosis by inhibition of aldosterone. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3306–3314. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004090804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Calhoun DA, Nishizaka MK, Zaman MA, Harding SM. Aldosterone excretion among subjects with resistant hypertension and symptoms of sleep apnea. Chest. 2004;125:112–117. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pratt-Ubunama MN, Nishizaka MK, Boedefeld RL, et al. Plasma aldosterone is related to severity of obstructive sleep apnea in subjects with resistant hypertension. Chest. 2007;131:453–459. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agodoa LY, Appel L, Bakris GL, et al. Effect of ramipril vs amlodipine on renal outcomes in hypertensive nephrosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:2719–2728. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.21.2719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peker Y, Kraiczi H, Hedner J, et al. An independent association between obstructive sleep apnoea and coronary artery disease. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:179–184. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14a30.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yaggi HK, Concato J, Kernan WN, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for stroke and death. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2034–2041. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Punjabi NM, Newman AB, Young TB, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular disease: an outcome-based definition of hypopneas. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:1150–1155. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200712-1884OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Somers VK, White DP, Amin R, et al. Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: an American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research Professional Education Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke Council, and Council on Cardiovascular Nursing. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:686–717. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Budhiraja R, Parthasarathy S, Quan SF. Endothelial dysfunction in obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3:409–415. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quercioli A, Mach F, Montecucco F. Inflammation accelerates atherosclerotic processes in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) Sleep Breath. 2010 Mar 3; doi: 10.1007/s11325-010-0338-3. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lattimore JL, Wilcox I, Skilton M, et al. Treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea leads to improved microvascular endothelial function in the systemic circulation. Thorax. 2006;61:491–495. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.039164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.El Solh AA, Akinnusi ME, Baddoura FH, Mankowski CR. Endothelial cell apoptosis in obstructive sleep apnea: a link to endothelial dysfunction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:1186–1191. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200611-1598OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schulz R, Mahmoudi S, Hattar K, et al. Enhanced release of superoxide from polymorphonuclear neutrophils in obstructive sleep apnea Impact of continuous positive airway pressure therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:566–570. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.2.9908091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yokoe T, Minoguchi K, Matsuo H, et al. Elevated levels of C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome are decreased by nasal continuous positive airway pressure. Circulation. 2003;107:1129–1134. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000052627.99976.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schulz R, Schmidt D, Blum A, et al. Decreased plasma levels of nitric oxide derivatives in obstructive sleep apnoea: response to CPAP therapy. Thorax. 2000;55:1046–1051. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.12.1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Phillips BG, Narkiewicz K, Pesek CA, et al. Effects of obstructive sleep apnea on endothelin-1 and blood pressure. J Hypertens. 1999;17:61–66. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199917010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Sarnak MJ. Clinical epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32(5 Suppl 3):S112–S119. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v32.pm9820470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schohn D, Weidmann P, Jahn H, Beretta-Piccoli C. Norepinephrine-related mechanism in hypertension accompanying renal failure. Kidney Int. 1985;28:814–822. doi: 10.1038/ki.1985.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sklar AH, Chaudhary BA, Harp R. Nocturnal urinary protein excretion rates in patients with sleep apnea. Nephron. 1989;51:35–38. doi: 10.1159/000185239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mello P, Franger M, Boujaoude Z, et al. Night and day proteinuria in patients with sleep apnea. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44:636–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]