Abstract

Throughout adulthood and old age, levels of well-being appear to remain relatively stable. However, evidence is emerging that late in life well-being declines considerably. Using long-term longitudinal data of deceased participants in national samples from Germany, the UK, and the US, we examine how long this period lasts. In all three nations and across the adult age range, well-being was relatively stable over age, but declined rapidly with impending death. Articulating notions of terminal decline associated with impending death, we identified prototypical transition points in each study between three and five years prior to death, after which normative rates of decline steepened by a factor of three or more. The findings suggest that mortality-related mechanisms drive late-life changes in well-being and highlight the need for further refinement of psychological concepts about how and when late-life declines in psychosocial functioning prototypically begin.

Keywords: Selective mortality, successful aging, differential aging, psychosocial factors, well-being, multiphase growth model

Empirical evidence indicates that individuals throughout adulthood and old age typically report being satisfied with their lives (see Diener et al., 2006). The objective of this study is to corroborate and extend recent studies that challenge this prevailing view (Gerstorf, Ram et al., 2008a,b; Mroczek & Spiro, 2005). Drawing from notions of terminal decline, we argue that individuals usually have enough resources to maintain a sense of well-being, even in the face of age-related risks for social losses and declining health (Guralnik, 1991; Suzman et al., 1992). At some point before death, however, additional mortality-related burdens and systemic dysfunction may become too difficult to cope with and functionality declines straight into death (Kleemeier, 1962; Riegel & Riegel, 1972). Despite these notions having been around for several decades, specific conceptual predictions and empirical descriptions regarding if and how terminal decline involves well-being have not yet been developed. Our purpose here is to use longitudinal data from three nationally representative samples to ask two questions about terminal decline in well-being: Do normative late-life changes in well-being across the adult life span conform to a pattern expected by terminal decline? If so, when does terminal decline prototypically begin?

Theories of self-regulation and lifespan development both propose that well-being remains largely stable across adulthood and old age. For example, models of hedonic adaptation suggest that changing life circumstances have only short-term effects on well-being, after which people quickly adapt and return to their characteristic levels or ‘set-points’ (Brickman & Campbell, 1971). Similarly, socioemotional selectivity theory, highlighting positive aspects of aging, contends that a limited future time perspective prompts a motivational shift towards regulating emotional states so as to optimize well-being (Carstensen, 2006). Because older adults typically perceive time as more finite than younger adults, they are often more motivated to achieve emotional meaning and satisfaction, which in turn results in them being as happy as (if not happier than) younger adults. These and other theories (e.g., action theory: Brandstädter, 1999) conjointly suggest that the self-regulation system is highly efficient in helping people adapt to a variety of (changes in) life circumstances.

A large body of literature across most of the world attests to the above proposals that well-being remains stable throughout adulthood (see Argyle, 1999; Carstensen et al., 2000; Diener et al., 1999, 2006; Kunzman et al., 2000; Larsen, 1978; Mroczek & Kolarz, 1998; Myers, 1992). Diener and Suh (1998), in reviewing cross-sectional results obtained in age-heterogeneous adult samples from multiple nations, concluded that life satisfaction is relatively stable across age cohorts in most societies. Longitudinal studies also provide evidence of relative stability in various facets of well-being across adulthood. For example, Charles, Reynolds, and Gatz (2001) used 23-year longitudinal data from the US and found stability in positive affect across most of adulthood, with only slight declines being noted after age 65. Similar results have been found in longitudinal samples from the US (Costa et al., 1987; Griffin et al., 2006) and Europe (Haynie et al., 2001; Kunzmann, 2008; Schilling, 2006). In sum, the general pattern of age-related stability of well-being, or small decreases over time, is well documented by both large-scale surveys and longitudinal studies of change and has been found consistently for different facets of well-being.

Recently, theory and evidence of stability in well-being across adulthood has been complemented by evidence suggesting that individuals who experience steep declines or report low levels of well-being are at higher risk of dying (Danner, Snowdon, & Friesen, 2001; Levy et al., 2002; Maier & Smith, 1999; Mroczek & Spiro, 2005). The conundrum of stability versus decline may be indicative of a terminal decline process (see Birren & Cunningham, 1985). Conceptual notions of terminal decline implicate mortality as a major force underlying developmental change in the last years of life (Kleemeier, 1962). The basic idea is that the mortal event serves as an “absorbing state” that drags individual function, including well-being, down. Empirical support has primarily accumulated in the cognitive aging domains (see Bäckman & MacDonald, 2006; Small & Bäckman, 1999), but initial evidence has recently also been documented for well-being among now deceased, 70 to 100 year old Germans (Gerstorf, Ram et al., 2008a,b). Our intent here is to examine further whether the terminal decline phenomena replicates and generalizes to mortal events that occur across the entire adult life span, rather than just in old age. To do so, we make use of well-being measures that were included in three national panel studies.

A crucial component of the terminal decline hypothesis is that there are two phases of change, a pre-terminal phase of relative stability or gradual age-related decline, and a terminal phase of steep, proximate-to-death decline (see Bäckman & MacDonald, 2006). The concept, however, lacks specificity regarding the timing of when such a transition to the terminal phase happens (e.g., “months to years” before death: Birren & Cunningham, 1985, p. 21). Applying recent developments in multi-phase growth modeling, researchers have started to empirically articulate and test the concept and to localize the onset of terminal decline. In the cognitive aging domain, empirical reports place the transition to the terminal phase between four years (Wilson et al., 2003) and eight years (Sliwinski et al., 2006) prior to death. Initial studies of terminal decline in well-being in old age located the prototypical transition four years before death (Gerstorf, Ram et al., 2008a), after which well-being dropped, on average, nearly a full standard deviation. Our study adds to those initial explorations by empirically estimating the onset of terminal decline in well-being using a much broader age spectrum of decedents from three large national samples, and may, we hope, prompt further precision and refinement of concepts about when, why, in which domains, and how the terminal phase of life begins and proceeds.

In sum, we use long-term longitudinal data of decedents from three nationally representative studies to evaluate if the terminal decline phenomena extend to aspects of well-being, and to determine when such terminal declines may be expected to begin. Specifically, we evaluate if two-phase models of change that articulate pre-terminal and terminal phases of decline provide a better description of long-term changes in well-being across the adult life span than do typical examinations of age-related change. Three national samples from Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States are used to obtain a normative description of if and how well-being changes across adulthood, from middle age until death.

Method

To examine within-person change in well-being, we fitted separate growth curve models to yearly longitudinal data from now deceased participants in the German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP; 22 annual waves from 1984 to 2005), the British Household Panel Study (BHPS; 15 annual waves from 1991 to 2005), and the US Health and Retirement Study (HRS; 6 biannual waves from 1994 to 2004). In-depth descriptions of these longitudinal panel studies can be found in prior publications (SOEP: Wagner et al., 2007; BHPS: Taylor et al., 2008; HRS: Burkhauser & Gertler, 1995). Details relevant to this investigation are given below.

Participants and Procedure

All three studies are national panels with data primarily collected via face-to-face (SOEP, BHPS) or telephone interviews (HRS). Here, we made use of data obtained from all study participants (decedents) who had died by the year 2006. Descriptive information is presented in Table 1. A few aspects are highlighted. First, included in each study were 2,000+ men and women who had died during adulthood, with the average age at death falling between age 70 and 80 years. Second, between-wave attrition has been relatively low, and individuals participated in an average of 3+ waves, with more than half of each sample contributing three or more data points. Third, on average, deaths occurred between six years and nine years after participants’ initial assessment and around two years after their last assessment. Finally, in each study, participants contributed more than 10,000 observations that simultaneously span the 25–100 year age range and the last 13+ years prior to death. Importantly, the large majority of these observations were provided between 50 and 90 years of age (85+% across studies) and in the last 10 years of life (75+% across studies).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Deceased Participants in the three National Samples.

| Variable | German SocioEconomic Panel (SOEP) | British Household Panel (BHPS) | US Health and Retirement Study (HRS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Npersons | 2,764 | 2,030 | 6,195 |

| Last years of death recorded | 2006 | 2006 | 2006 |

| % women | 48 | 52 | 54 |

| Birth cohorts | 1888 – 1982 | 1894 – 1989 | 1890 – 1969 |

| Age at death | |||

| M (SD) | 72.24 (14.48) | 75.09 (13.93) | 79.81 (10.62) |

| Range | 20 – 101 | 16 – 107 | 35 – 111 |

| Number of waves | |||

| M (SD) | 8.35 (5.54) | 5.41 (3.98) | 3.05 (1.64) |

| Range | 1 – 22 | 1 – 15 | 1 – 6 |

| % 3+ waves | 88 | 68 | 57 |

| % between-wave attrition1 | 4 – 14 | 1 – 12 | 6 – 8 |

| Distance first assessment to death | |||

| M (SD) | 9.32 (5.49) | 6.43 (4.24) | 6.43 (3.47) |

| Range | 1 – 22 | 0 – 15 | 0 – 13 |

| Distance last assessment to death | |||

| M (SD) | 1.95 (2.58) | 1.77 (2.02) | 2.14 (2.12) |

| Range | 0 – 16 | 0 – 15 | 0 – 13 |

| Nobservations | 22,672 | 10,981 | 18,520 |

| Chronological age | |||

| M (SD) | 65.84 (14.34) | 70.17 (13.74) | 75.31 (10.42) |

| Range | 19 – 100 | 15 – 99 | 25 – 110 |

| % 50–90 years | 86 | 89 | 94 |

| Distance-to-death | |||

| M (SD) | 7.04 (4.86) | 5.30 (3.60) | 4.93 (3.15) |

| Range | 22 – 0 | 15 – 0 | 13 – 0 |

| % last 10 years | 77 | 89 | 95 |

Note.

calculated across various subsamples, between-wave attrition is annual in the SOEP and the BHPS, and biannual in the HRS. In our analyses, we included now deceased participants from national panel studies of some 40,000 persons in Germany (SOEP), some 30,000 persons from England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland (BHPS), and some 25,000 persons from states throughout the US (HRS).

Measures

Well-Being

In the SOEP, well-being was measured using the item “How satisfied are you currently with your life, all things considered?”, answered on a scale from 0 (“completely unsatisfied”) to 10 (“completely satisfied”). Responses are taken as an indication of cognitive-evaluative aspects of well-being (Fujita & Diener, 2005). BHPS participants completed the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ; Goldberg, 1978), a measure indicative of emotional-affective aspects of well-being (Hu et al., 2007). The scale was a sum of 12 items (e.g., “Have you recently been feeling reasonably happy, all things considered?”) that were answered using a 1 (“more so than usual”) to 4 (“much less than usual”) scale. HRS participants responded to eight items from the CES-D scale (Radloff, 1977), asking if they had experienced feelings of being depressed, happy, or sad either 1 (“much of the time during the past week”) or 0 (“not much of the time during the past week”).

Although the measures assessed varying degrees of cognitive-evaluative (SOEP) or emotional-affective aspects of well-being (BHPS, HRS), all were taken as the available indicator of a general well-being construct. Across studies, item responses and summary scores were coded so that higher scores indicate higher levels of well-being, and were standardized, within each study, to a T metric (mean = 50; SD = 10), with the population of observations within a given study serving as the reference frame for the rescaling (SOEP: mean = 6.65, SD = 2.26 on a 0–10 scale; BHPS: mean = 23.91, SD = 5.74 on a 0–36 scale; HRS: mean = 6.03, SD = 2.11 on a 0–8 scale).

Time metrics of age and distance-to-death

Age at each wave was calculated as the number of years since an individual’s birth (centered at 75 years). Distance-to-death at each occasion was calculated as the difference between the year of assessment and the year of an individual’s death, obtained either directly from the participants’ household or neighbors during the yearly interview (SOEP and BHPS) or from city or national registries or offices (e.g., US National Death Index for HRS). Both time metrics were coded using integer number of years.1

Growth Models

The main analytic task was to determine if models articulating the terminal decline hypothesis, two phases of change over distance-to-death, provided a better representation of observed changes in well-being than the more typical age-based, single-phase models of change. Separately for each study, we assessed and compared relative fits of two sets of growth models.

The age-related change models were specified as

| (1) |

where person i’s reported well-being at time t, WBti, is a function of an individual-specific intercept parameter, β0i, individual-specific linear and quadratic slope parameters, β1i and β2i, that capture the rate and acceleration of change per year and residual error, eti. Following standard multilevel/latent growth modeling procedures, individual-specific intercepts,β0i, and slopes, β1i and β2i, (from the Level 1 model given in Equation 1) were modeled as

| (2) |

(i.e., Level-2 model) where γ00, γ01, and γ02 are sample means, and u0i, and u1i are individual deviations from those means that are assumed to be normally distributed, correlated with each other, and uncorrelated with the residual errors, eit. Deviations for the quadratic slope, u2i were examined, but were not significant and thus not included in the final models.

Notions of terminal decline were invoked using extensions (Cudeck & Harring, 2007; Cudeck & Klebe, 2002) of multiphase or “spline” growth models (Ram & Grimm, 2007; Singer & Willett, 2003) with a distance-to-death, DtD, time variable. Specifically, models were specified as

| (3) |

where individual-specific rates of change in the pre-terminal phase are captured by β1i, and individual-specific rates of change after the transition point (i.e., terminal-phase) are captured by β2i. The point of transition from one phase to the other, k, is a free (fixed effect) parameter estimated from the data, with β0i capturing individuals’ estimated level of well-being at this transition point. As in the age-related change model, interindividual differences were modeled using the Level-2 model (e.g., Equation 2), where u0i, u1i, and u2i are assumed to be normally distributed, correlated with each other, and uncorrelated with the residual errors, eit. Models were fit to the data using SAS Proc Mixed or Proc NLMixed. Using the accelerated longitudinal design and associated missing at random assumptions, individual data segments were treated as a single sample within each sample (Little & Rubin, 1987; McArdle & Bell, 2000). Model inferences are most relevant for the 50 to 90 years age span and/or the decade prior to death. The correlation between age and distance-to-death was of moderate size (r < .28 across studies, p’s < .001) suggesting that older individuals were somewhat closer to death, and only partial overlap between the two time dimensions. Fit statistics and results were interpreted in relation to our two questions: Do changes in well-being across the adult life span conform to the multi-phase pattern expected by terminal decline? If so, when does terminal decline prototypically begin?

Results

In all three studies, the repeated measures of well-being exhibited substantial within-person variation over time (SOEP: 55%; BHPS: 47%; HRS: 49%). We used two sets of growth models, age-related change and terminal decline, to describe and evaluate how this within-person variation was structured. Table 2 reports parameter estimates and fit statistics.

Table 2.

Growth Models over Chronological Age and Distance-to-Death for Well-Being in the three National Samples.

| Parameter | German SocioEconomic Panel (SOEP) |

British Household Panel (BHPS) |

US Health and Retirement Study (HRS) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age |

Distance-to-Death |

Age |

Distance-to-Death |

Age |

Distance-to-Death |

|||||||

| Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | |

| Fixed effects | ||||||||||||

| Intercept, a00 | 48.81 * | (0.19) | 50.36 * | (0.19) | 49.43 * | (0.20) | 50.45 * | (0.25) | 50.32 * | (0.13) | 49.57 * | (0.17) |

| Linear slope 1, a01 | − 0.26 * | (0.02) | − 0.22 * | (0.02) | − 0.08 * | (0.02) | − 0.18 * | (0.05) | − 0.10 * | (0.01) | − 0.29 * | (0.03) |

| Quadratic slope, a02 | − 0.005* | (0.000) | – | – | − 0.001 | (0.001) | – | – | − 0.005* | (0.001) | – | – |

| Transition point, k | – | – | − 4.27 * | (0.10) | – | – | − 4.85 * | (0.18) | – | – | − 2.92 * | (0.20) |

| Linear slope 2, a02 | – | – | − 1.31 * | (0.08) | – | – | − 0.66 * | (0.08) | – | – | − 0.88 * | (0.10) |

| Random effects | ||||||||||||

| Variance intercept | 61.69 * | (2.70) | 62.06 * | (2.52) | 51.39 * | (2.50) | 66.82 * | (3.33) | 47.08 * | (1.53) | 62.92 * | (2.22) |

| Variance linear slope 1 | 0.10 * | (0.01) | 0.37 * | (0.03) | 0.06 * | (0.01) | 0.65 * | (0.09) | 0.06 * | (0.01) | 0.55 * | (0.07) |

| Variance linear slope 2 | – | – | 4.90 * | (0.41) | – | – | 4.02 * | (0.48) | – | – | 4.30 * | (0.92) |

| Cov. intercept, slope 1 | 1.22 * | (0.12) | 2.70 * | (0.25) | 0.23 | (0.12) | 3.81 * | (0.46) | − 0.19 * | (0.07) | 2.71 * | (0.35) |

| Cov. intercept, slope 2 | – | – | − 4.81 * | (0.72) | – | – | − 5.72 * | (0.88) | – | – | 3.51 * | (1.04) |

| Cov. slope 1, slope 2 | – | – | − 0.16 | (0.09) | – | – | − 0.30 * | (0.15) | – | – | 0.31 | (0.20) |

| Residual variance | 51.76 * | (0.54) | 44.57 * | (0.49) | 46.77 * | (0.74) | 37.92 * | (0.64) | 48.67 * | (0.64) | 42.43 * | (0.71) |

| Pseudo-R2 reduction | .091 | .216 | .033 | .215 | .031 | .156 | ||||||

| −2LL | 160,341 | 158,632 | 77,217 | 76,444 | 133,067 | 132,593 | ||||||

| AIC | 160,355 | 158,654 | 77,231 | 76,466 | 133,081 | 132,615 | ||||||

Note. Unstandardized estimates and standard errors are presented. Scores standardized to a T metric using all decedent observations available in each study as the reference frame; intercepts centered at age 75 for the age-related models and at the transition point for the distance-to-death models;slope or rate of change scaled in T-units per year. AIC = Akaike Information Criterion; −2LL = −2 Log Likelihood, relative model fit statistics. Cov. = Covariance.

p < .05 or below.

Age-related change

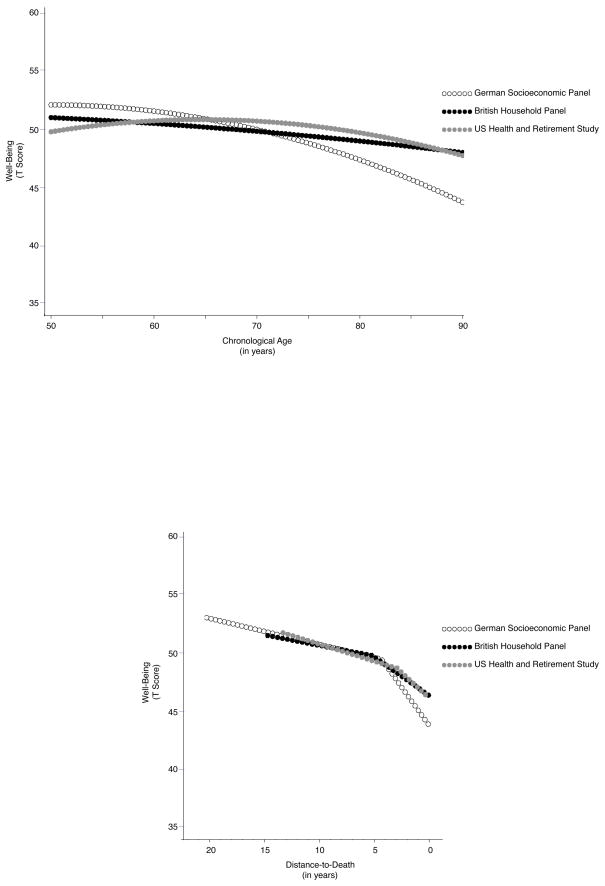

Across studies, results from the age-related change models suggest stability or relatively shallow declines in well-being during adulthood and old age. As seen in Table 2, the cognitive-evaluative measure used in the SOEP showed an average rate of linear decline of − 0.26 T-units per year, and the emotional-affective measures in the BHPS and the HRS declined linearly by − 0.08 and − 0.10 T-units per year, respectively. Additionally, as seen in Panel A of Figure 1, the normative trends in all three samples had a small amount of negative quadratic curvature – possibly indicating some slight accommodation of lower scores in old age.

Figure 1.

Prototypical rates of well-being decline observed over chronological age (Panel A) and distance-to-death (Panel B). Consistently across data from three national studies in Germany, the UK, and the US, well-being was relatively stable over age, but declined rapidly with impending death. After the onset of a terminal phase between three and five years prior to death, well-being decline steepened by a factor of three or more.

Age-related change vs. terminal decline

These single-phase, age-related models were then compared to the two-phase, distance-to-death models of terminal decline. As seen in the fit statistics reported in Table 2, the terminal decline models had better relative fit in all three data sets. Specifically, the lower AIC (e.g., SOEP: AIC = 158,654 vs. 160,355) and the proportional reduction of prediction error (i.e., a pseudo-R2 measure; Snijders & Bosker, 1999; SOEP: .216 vs. .091) both indicate that the terminal decline models fit the data better than the age-related models. In sum, the results suggest that changes in well-being across the adult life span do conform to the multi-phase pattern expected by terminal decline.

Terminal-decline

Examining Table 2, one can note correspondence between the linear slope in the age-related change models (e.g., SOEP: − 0.26 T-units per year) and the pre-terminal slopes in the terminal decline models (e.g., SOEP: − 0.22 T-units per year). As seen in Panel B of Figure 1, this relative stability in well-being contrasts sharply with the normative decline in the terminal phase in all three studies (SOEP: − 1.31 T-units per year) wherein well-being appears to drop sharply into death.2 The two-phase model allowed for empirical identification of when the terminal phase of decline begins. Across studies, the point of “transition” was estimated to be between three and five years prior to death (SOEP = 4.27; BHPS = 4.85; HRS = 2.92).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine if normative changes in well-being across adulthood conform to the pattern expected by notions of terminal decline, and if so, when the terminal phase of decline prototypically begins. Using long-term longitudinal data from decedents in three nationally representative studies in Germany, the UK, and the US, we consistently found greater proportions of explained variance for models articulating the terminal decline hypothesis, relative to typical age-based models. In line with theories of self-regulation (Brickman & Campbell, 1971) and successful aging (Carstensen, 2006) and the myriad of empirical reports (see Diener et al., 2006), our age-related results indicate mean-level stability or minor decline in well-being across adulthood and old age. Our findings, however, also consistently suggest some qualification to this prevailing picture. Well-being does not, on average, appear to be stable in the last years of a person’s life. Charting well-being in relation to the years left in life rather than over the years lived revealed, consistent with theoretical notions of terminal decline, alarmingly steep normative proximate-to-death deteriorations in well-being that span three to five years.

Our findings add to recent reports that major life events such as widowhood result in long-lasting well-being changes (e.g., lower levels persist over time; Lucas, 2007; Headey, 2008) and suggest that impending death denotes another major life event that contributes to systematic well-being changes, albeit ones that lead up to the event rather than resulting from it. In line with this view, the findings are interpreted to indicate that mortality-related mechanisms or other progressive processes leading towards death (e.g., deteriorating health) overwhelm the regulatory or motivational mechanisms that usually keep well-being stable and become the prime drivers of late-life decline in well-being. More generally, our findings highlight the need to consider when and how mortality or other selection processes contribute to observed changes (Hertzog & Nesselroade, 2003; Lindenberger et al., 2002) and the need for further refinement of concepts about when and how late-life declines in psychosocial functioning typically begin and proceed.

Seminal notions of terminal decline have proposed that the last months or years of life are characterized by a phase of rapid decline wherein mortality-related processes compromise integral aspects of function (Kleemeier, 1962). Consistent with this general proposal, our mortality-related models portray a normative picture of well-being change with individuals transitioning from a pre-terminal age-dominated phase of minor decline to a terminal mortality-dominated phase of steep decline. The replication and generalization across-nations provides further evidence that exacerbated rates of end-of-life declines are not specific to intellectual and sensory functioning (Bäckman & MacDonald, 2006; MacDonald, Hultsch, & Dixon, 2008), but also extend to subjective well-being. Further, late-life declines in well-being are not restricted to individuals who died in old age (Gerstorf, Ram et al., 2008a,b), but are also found when all adult decedents, no matter their age of death are examined.3 This is notable because middle-aged adults, relative to older people, may have a larger pool of resources to draw from and thereby might be better able to ward-off the detrimental effects of impending death. More in-depth work is of course necessary to thoroughly examine such age-differential questions, but our evidence illustrates the pervasive nature of mortality-related processes.

Theoretical notions have been vague about when end-of-life decrements can typically be expected to begin or how they may proceed across domains of function (Birren & Cunningham, 1985). Thus, to inform future theoretical specification regarding the timing of terminal decline, we used models that allowed for empirical localization of the normative onset of transition to the terminal phase of life. Treating the three national samples as independent replications, we found, despite only partial overlap at the measurement level, strikingly similar construct-level findings. Prototypically, terminal decline in well-being appears to span the last three to five years of life.

Despite apparent across-nation similarities, however, we also observed notable differences in the amount of average mortality-related decline, with stronger prototypical decrements in the SOEP than in the BHPS or HRS. Differences in measurement scales, reliability of those scales, whether those scales tapped cognitive-evaluative or emotional aspects of well-being, study sampling and maintenance procedures, and the timing of observations discourage comparisons beyond the general pattern of findings. As a consequence, inferences regarding differences between national trends or between specific aspects of well-being are not warranted. Given that we are only at the very beginning of understanding the etiological nature of mortality-related decline in well-being, we interpret the consistency of results across the three studies as national-level replications. A better understanding will be obtained when we are able to pinpoint within-person processes more specifically and identify the roles that endogenous factors (e.g., physical and mental health, disease and other causes of death, social relations, etc.) and exogenous factors (e.g., health and social infrastructure) play in the onset and progression of terminal decline (or stability).

Conclusions and Outlook

In our study, we have applied contemporary methods to articulate and test long-standing conceptual notions of terminal decline (Kleemeier, 1962). In line with those notions, well-being remained, on average, relatively stable with age, and declined rapidly with impending death. Conceptually, this pattern provides a rather disconcerting image of late-life psychological health that qualifies notions of successful aging (Rowe & Kahn, 1997; see Baltes, 2006) and highlights the need for identifying and targeting via intervention potential moderators (e.g., accumulating disability: Verbrugge & Jette, 1994; cognitive terminal decline: Small & Bäckman, 1999) that may account for inter-individual differences in how well-being changes in late-life. We also note that even such extended longitudinal data as were available here constrain which aspect of late-life change we could study. We prioritized to determine the “average” population-level estimates for locating the onset of terminal decline, making the strict assumption that the transition point is invariant across individuals. Relaxing this assumption requires a larger density of observations, probably measuring people several times a year until death (see second analysis in Gerstorf, Ram et al., 2008a4). Finally, we modeled developmental change as a function of a future event, death, such that death serves as a retroactive cause for the observed decline. Ideally, we would like to test in a prospective manner whether observed decline is predictive of the unknown subsequent event of death, which would require an additional shift in data-analytic perspective from our descriptive models to a more complex set of predictive models (see Ghisletta et al., 2006).

The deteriorating late-life psychological health found in this three-nation study suggests that the societal burden and personal costs of dying may span the last three to five years of life. Given the alarmingly steep end-of-life declines individuals typically face, a better understanding of when and how terminal declines begin and proceed is warranted. Further knowledge is also needed about why some persons may experience fewer decline or a later onset of decline prior to death. Such inquiries will help identify those pathways by which more and more individuals can, in the face of seemingly inevitable decline, remain happy until the end.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the support provided by the National Institute on Aging (R21 AG032379), the DIW Berlin (German Institute for Economic Research), the Max Planck Society, and the Social Science Research Institute at the Pennsylvania State University. Additional support was provided by grants from the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (Germany) to Juergen Schupp and Gert G. Wagner. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

This was a data protection regulation for Germany. To minimize methodological variations between studies, timing of death for BHBS and HRS participants was also granulated to year (rather than using the day and month precision).

Consistent with the general pattern of results, a single-phase model over distance-to-death revealed more efficient descriptions than a single-phase model over age (SOEP: Pseudo R2 reduction = .150; BHPS: Pseudo R2 reduction = .138; HRS: Pseudo R2 reduction = .110). However, the two-phase models over distance-to-death still provided better relative model fit than the single-phase models over distance-to-death (SOEP:ΔAIC = 466; BHPS:ΔAIC = 236; HRS:ΔAIC = 44). We note that observations outside the 50-to-90 years of age or 20+ years prior to death were not graphed in Figure 1 because of scarce data across these ages.

Including all participants (independent of their mortality status) when estimating age-related models resulted in somewhat shallower age gradients (e.g., N = 20,263 SOEP participants: Linear slope = − 0.16; quadratic slope = − 0.001, both p’s < .05 or below). The general pattern of results was also found in all three studies when we restricted the samples to those who died before age 70 (e.g., SOEP: N = 1,024, Pseudo R2 reduction in age model = .081 vs. distance-to-death model = .203).

Using data from a subsample of 400 SOEP participants who provided between 12 and 25 annual reports and models that allow for interindividual differences in the timing of the transition to terminal decline we found considerable between-person differences in the location of the transition point. While 12 measurement occasions might serve as a rough minimum number of occasions needed for estimating such models, many more occasions are preferable.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/PAG

Contributor Information

Denis Gerstorf, Email: gerstorf@psu.edu.

Nilam Ram, Email: nilam.ram@psu.edu.

Guy Mayraz, Email: G.Mayraz@lse.ac.uk.

Mira Hidajat, Email: mhidajat@pop.psu.edu.

Ulman Lindenberger, Email: seklindenberger@mpib-berlin.mpg.de.

Gert G. Wagner, Email: g.wagner@ww.tu-berlin.de.

Jürgen Schupp, Email: jschupp@diw.de.

References

- Argyle M. Correlates and consequences of happiness. In: Kahneman D, Diener E, Schwarz N, editors. Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology. New York, NY: Sage; 1999. pp. 353–373. [Google Scholar]

- Bäckman L, MacDonald SWS. Death and cognition: Synthesis and outlook. European Psychologist. 2006;11:224–235. [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB. Facing our limits: Human dignity in the very old. Daedalus. 2006;135:33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Birren JE, Cunningham WR. Research on the psychology of aging: Principles, concepts and theory. In: Birren JE, Schaie KW, editors. Handbook of the psychology of aging. 2. New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold; 1985. pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Brickman P, Campbell DT. Hedonic relativism and planning the good society. In: Appley M, editor. Adaptation-level theory. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1971. pp. 287–305. [Google Scholar]

- Brandstädter J. Sources of resilience in the aging self: Toward integrating perspectives. In: Hess TM, Blanchard-Fields F, editors. Social cognition and aging. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1999. pp. 123–141. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhauser RV, Gertler PJ. Introduction: Special Issue on the Health and Retirement Survey: Data quality and early results. Journal of Human Resources. 1995;30:S1–S6. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL. The influence of a sense of time on human development. Science. 2006;312:1913–1915. doi: 10.1126/science.1127488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Pasupathi M, Mayr U, Nesselroade J. Emotion experience in everyday life across the adult life span. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:644–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Reynolds CA, Gatz M. Age-related differences and change in positive and negative affect over 23 years. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80:136–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Zonderman AB, McCrae RR, Cornoni-Huntley J, Locke BZ, Barbano HE. Longitudinal analyses of psychological wellbeing in a national sample: Stability of means levels. Journal of Gerontology. 1987;42:50–55. doi: 10.1093/geronj/42.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cudeck R, Harring JR. Analysis of nonlinear patterns of change with random coefficient models. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:615–637. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cudeck R, Klebe KJ. Multiphase mixed-effects model for repeated measure data. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:41–63. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danner DD, Snowdon DA, Friesen WV. Positive emotions in early life and longevity: Findings from the Nun Study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80:804–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Lucas RE, Scollon CN. Beyond the hedonic treadmill: Revising the adaptation theory of well-being. American Psychologist. 2006;61:305–314. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.4.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Suh ME. Subjective well-being and age: An international analysis. In: Schaie KW, Lawton MP, editors. Annual review of gerontology and geriatrics. New York, NY: Springer; 1998. pp. 304–324. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas RE, Smith HL. Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125:276–302. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita F, Diener E. Life satisfaction set point: Stability and change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:158–164. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstorf D, Ram N, Estabrook R, Schupp J, Wagner GG, Lindenberger U. Life satisfaction shows terminal decline in old age: Longitudinal evidence from the German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP) Developmental Psychology. 2008a;44:1148–1159. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstorf D, Ram N, Röcke C, Lindenberger U, Smith J. Decline in life satisfaction in old age: Longitudinal evidence for links to distance-to-death. Psychology and Aging. 2008b;23:154–168. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.23.1.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghisletta P, McArdle JJ, Lindenberger U. Longitudinal cognition-survival relations in old and very old age: 13-year data from the Berlin Aging Study. European Psychologist. 2006;11:204–223. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg DP. Manual of the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor, UK: NFER Nelson; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin PW, Mroczek DK, Spiro A. Variability in affective change among aging men: Longitudinal findings from the VA Normative Aging Study. Journal of Research in Personality. 2006;40:942–965. [Google Scholar]

- Guralnik JM. Prospects for the compression of morbidity: The challenge posed by increasing disability in the years prior to death. Journal of Aging and Health. 1991;3:138–154. [Google Scholar]

- Haynie DA, Berg S, Johannson B, Gatz M, Zarit SH. Symptoms of depression in the oldest old: A longitudinal study. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences. 2001;56B:P111–P118. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.2.p111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headey B. Life goals matter to happiness: a revision of set-point theory. Social Indicators Research. 2008;86:213–231. [Google Scholar]

- Hertzog C, Nesselroade JR. Assessing psychological change in adulthood: An overview of methodological issues. Psychology and Aging. 2003;18:639–657. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.4.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Stewart-Brown S, Twigg L, Weich S. Can the 12-item General Health Questionnaire be used to measure positive mental health. Psychological Medicine. 2007;37:1005–1013. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707009993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleemeier RW. Intellectual changes in the senium. Proceedings of the Social Statistics Section of the American Statistical Association. 1962;1:290–295. [Google Scholar]

- Kunzmann U. Differential age trajectories of positive and negative affect: Further evidence from the Berlin Aging Study. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences. 2008;63B:P261–P270. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.5.p261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzmann U, Little TD, Smith J. Is age-related stability of subjective well-being a paradox? Cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence from the Berlin Aging Study. Psychology and Aging. 2000;15:511–526. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.15.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson R. Thirty years of research on the subjective well-being of older Americans. Journal of Gerontology. 1978;33:109–125. doi: 10.1093/geronj/33.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy BR, Slade MD, Kunkel SR, Kasl SV. Longevity increased by positive self-perceptions of aging. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83:261–270. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenberger U, Singer T, Baltes PB. Longitudinal selectivity in aging populations: Separating mortality-associated versus experimental components in the Berlin Aging Study (BASE) Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences. 2002;57B:P474–P482. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.6.p474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. New York, NY: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas RE. Adaptation and the set-point model of subjective well-being: Does happiness change after major life events? Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;16:75–79. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald SWS, Hultsch DF, Dixon RA. Predicting impending death: Inconsistency in speed is a selective and early marker. Psychology and Aging. 2008;23:595–607. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.23.3.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier H, Smith J. Psychological predictors of mortality in old age. Journals of Gerontology: Series B Psychological Sciences. 1999;54B:P44–P54. doi: 10.1093/geronb/54b.1.p44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Bell RQ. An introduction to latent growth models for developmental data analysis. In: Little TD, Schnabel KU, Baumert J, editors. Modeling longitudinal and multiple-group data: Practical issues, applied approaches, and scientific examples. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2000. pp. 69–107. [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek DK, Kolarz CM. The effect of age on positive and negative affect: A developmental perspective on happiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:1333–1349. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.5.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek DK, Spiro A., III Change in life satisfaction during adulthood: Findings from the Veterans Affairs Normative Aging Study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:189–202. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LW. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Ram N, Grimm KJ. Using simple and complex growth models to articulate developmental change: Matching theory to method. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2007;31:303–316. [Google Scholar]

- Riegel KF, Riegel RM. Development, drop, and death. Developmental Psychology. 1972;6:306–419. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Successful aging. Gerontologist. 1997;37:433–440. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling O. Development of life satisfaction in old age: Another view on the paradox. Social Indicator Research. 2006;75:241–271. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sliwinski MJ, Stawski RS, Hall RB, Katz M, Verghese J, Lipton RB. On the importance of distinguishing pre-terminal and terminal cognitive decline. European Psychologist. 2006;11:172–181. [Google Scholar]

- Small BJ, Bäckman L. Time to death and cognitive performance. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1999;8:168–172. [Google Scholar]

- Snijders TAB, Bosker RJ. Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. London, UK: Sage; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Suzman RM, Willis DP, Manton KG, editors. The oldest old. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MF, Brice J, Buck N, Prantice-Lane E, editors. British Household Panel Survey User Manual Volume A: Introduction, Technical Report and Appendices. Colchester, UK: University of Essex; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge LM, Jette AM. The disablement process. Social Science and Medicine. 1994;38:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90294-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner GG, Frick JR, Schupp J. Enhancing the power of household panel studies: The case of the German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP) Schmollers Jahrbuch. 2007;127:139–169. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Beckett LA, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Terminal decline in cognitive function. Neurology. 2003;60:1782–1787. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000068019.60901.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]