Abstract

Background

Many smokers in Western countries perceive “light” or “low tar” cigarettes as less harmful and less addictive than “regular” or “full flavoured” cigarettes. However, there is little research on whether similar perceptions exist among smokers in low and middle incomes, including China.

Objective

To characterise beliefs about “light” and “low tar” cigarettes among adult urban smokers in China.

Methods

We analysed data from Wave 1 of the ITC China Survey, a face-to-face household survey of 4732 adult Chinese smokers randomly selected from six cities in China in 2006. Households were sampled using a stratified multistage design.

Findings

Half (50.0%) of smokers in our sample reported having ever tried a cigarette described as “light,” “mild” or “low tar”. The majority of smokers in our sample (71%) believed that “light” and/or “low tar” cigarettes are less harmful compared to “full flavoured” cigarettes. By far the strongest predictor of the belief that “light” and/or “low tar” cigarettes are less harmful was the belief that “light” and/or “low tar” cigarettes feel smoother on the respiratory system (p<0.001, OR=53.87, 95% CI 41.28 to 70.31).

Conclusion

Misperceptions about “light” and/or “low tar” cigarettes were strongly related to the belief that these cigarettes are smoother on the respiratory system. Future tobacco control policies should go beyond eliminating labelling and marketing that promotes “light” and “low tar” cigarettes by regulation of product characteristics (for example, additives, filter vents) that reinforce perceptions that “light” and “low tar” cigarettes are smoother on the respiratory system and therefore less harmful.

It is estimated that there are 320 million smokers in China.1 Approximately 57% of adult males and 3% of adult females in China are current smokers.2 Currently, about one million smokers in China will die from tobacco-related illnesses per year1 but it is expected to rise to 2.2 million deaths by 2020.3

We can examine the experiences of Western countries to predict what might happen in China. In Western countries, “light” and “low tar” cigarettes were initially introduced in the 1960s and 1970s as smokers became aware of the health risks of smoking. These cigarettes have been marketed using advertising and packaging which suggests that these brands are less harmful alternatives to “full flavour” or “regular” brands4 5 and therefore appeal to health concerned smokers.6–9 Consequently, the availability of “low tar” cigarettes is likely to have discouraged some smokers from quitting,10 11 although this evidence is not conclusive.12 Brands that are described as “low tar” typically generate lower levels of tar and nicotine emissions under machine testing owing to higher levels of filter ventilation and filtration. However, smokers have been shown to compensate for the reduced deliveries of nicotine in order to achieve target nicotine doses, therefore increasing tar delivery and suggesting that the originally anticipated benefits of “low tar” cigarettes would not eventuate.13–16 This is in accordance with the epidemiological evidence, which has shown that these brands are no less harmful to consumers.17 18

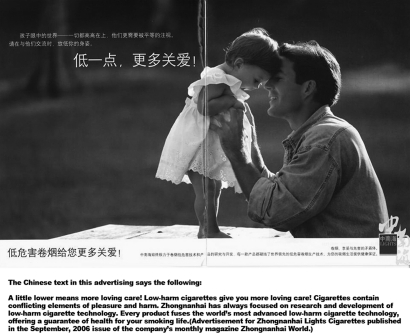

It is unclear to what extent similar marketing practices have been employed in China. Tobacco industry documents have demonstrated that Philip Morris launched Marlboro Lights in 1994 in major urban centres in the People's Republic of China. Philip Morris predicted that young adult smokers would follow the established trend in Hong Kong towards lower tar and nicotine products.19 There is also evidence that “low tar” cigarettes were associated with “lower risk”—see figure 1 for an example. Tar yield numbers are also printed on the side of many Chinese cigarette packages, reinforcing the belief that they are less harmful. Anecdotal evidence, however, suggests that the use of terms such as “light” or “mild” to market “low tar” cigarettes has been less common in mainland China than in Western countries. These terms do appear on some cigarette packages (for example, Zhongnanhai Light), but typically appear only in English.

Figure 1.

An advertisement for Zhongnanhai Lights Cigarettes.

Brands with higher levels of filter ventilation and other design features that generate low tar under machine tests are less prevalent in China than in Western countries primarily because of a lack of domestic production technology and a limited presence of foreign brands in the Chinese market to stimulate interest in alternatives to the traditional higher tar cigarette.20

Although smokers in China are less aware and health concerned about the health risks of smoking compared to other countries,21 22 this may soon be changing. As China implements more stringent tobacco control policies in accordance with the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), it is anticipated that there will be an increase in public education about the health risks of smoking. Chinese smokers are therefore more likely to become concerned about health, and it is anticipated that the market share of lower tar brands will increase in response to these rising concerns. Regulations that prohibit the sale of cigarettes above 15 mg tar/stick in 2004 are also expected to reduce the machine tar numbers, as is the increasing presence of multinational companies.20

Use of “light” and “low tar” cigarettes is likely to increase; however, to our knowledge no research has examined beliefs about the relative health risks of “light” and “low tar” cigarettes compared to full flavoured cigarettes among smokers in China. It will be important to know whether these cigarettes are also seen as “less harmful” and therefore could be appealing to health-concerned smokers in China. The International Tobacco Control (ITC) China Survey, conducted in six Chinese cities among representative samples of adult smokers included a number of survey questions designed to assess beliefs about “light” and/or “low tar” cigarettes (which we will refer to as “LLT”). We also examined which factors are independently associated with a belief that LLT cigarettes are less harmful relative to full flavoured cigarettes.

We focused on beliefs about the sensory experience of LLT cigarettes as a potentially important factor that could lead smokers to believe that LLT cigarettes as less harmful. Previous research has demonstrated an association between the belief that LLT cigarettes are smoother and the belief that LLT cigarettes are less harmful.7 8 23 This study will examine whether smokers in China who believe that LLT cigarettes are smoother on the respiratory system compared to regular cigarettes are more likely to believe that LLT cigarettes are less harmful. In countries where “light” and “low tar” descriptors were removed, smokers continued to believe that LLT cigarettes are less harmful particularly if they believed that these cigarettes are smoother on the throat and chest.24 We therefore tested whether this association also existed in China.

This was a critical time to evaluate beliefs about the relative harm of “light” and “low tar” cigarettes because China introduced a ban on these descriptors in January 2006 (however, the tobacco industry was given a grace period until April 2006). Because our survey started in April 2006, we are not able to compare changes in smokers’ perceptions about “light” and “low tar” cigarette labelling before and after the regulation took effect even though it is likely that some cigarettes with “light” and “low tar” labels were still on store shelves after the official policy took effect. However, future research waves can address the impact of this ban.

Method

Sample

Participants were from Wave 1 of the ITC China Survey conducted in April to August 2006. The ITC China Survey is a prospective, face-to-face, cohort survey of adult smokers and non-smokers 18 years of age or older. The current study examined smokers only (respondents who had smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their life and smoked at least weekly, n=4732). Respondents were from six cities: Beijing (n=785), Guangzhou (n=791), Shenyang (n=781), Shanghai (n=784), Changsha (n=800) and Yinchuan (n=791). A seventh city, Zhengzhou, was initially included in the study. Wave 1 and 2 data were examined across both waves. A random sample of the survey data and MP3 recordings of survey interviews were examined in each city to ensure consistency in responses between waves. In Zhengzhou there was a significant level of inconsistencies between Wave 1 and Wave 2 (for example, different genders for the supposedly same respondents), the city was therefore removed from the study (there were virtually no such cases in the other six cities). Cooperation rates were 80.0% in Beijing (estimated), 80.0% in Guangzhou (estimated), 81.2% in Shenyang (exact), 84.2% in Shanghai (exact), 80.0% in Changsha (estimated) and 90.3% in Yinchuan (exact). Response rates were 50.0% in Beijing (estimated), 50.0% in Guangzhou (estimated), 50.0% in Shenyang (exact), 61.3% in Shanghai (exact), 50.0% in Changsha (estimated), and 39.4% in Yinchuan (exact). The cooperation rates were comparable to (and the response rates were generally higher than) those obtained in the ITC Four Country Survey (a telephone survey of smokers in Canada, United States, United Kingdom and Australia). Table 1 presents the sample characteristics of respondents included in these analyses.

Table 1.

Unweighted sample characteristics for the six Chinese cities in the ITC China Survey

| Factor | Beijing (n=785) | Shenyang (n=781) | Shanghai (n=784) | Changsha (n=800) | Yinchuan (n=791) | Guangzhou (n=791) | Overall (n=4732) | ||

| No (%) | No (%) | No (%) | No (%) | No (%) | No (%) | No (%) | |||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 743 (94.6) | 741 (94.9) | 765 (97.6) | 732 (91.5) | 772 (97.6) | 746 (94.3) | 4499 (95.1) | ||

| Female | 42 (5.4) | 40 (5.1) | 19 (2.4) | 68 (8.5) | 19 (2.4) | 45 (5.7) | 233 (4.9) | ||

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| 18–39 | 120 (15.3) | 111 (14.2) | 89 (11.3) | 201 (25.1) | 258 (32.6) | 118 (14.9) | 897 (19.0) | ||

| 40–54 | 373 (47.5) | 456 (58.4) | 456 (58.2) | 362 (45.3) | 343 (43.4) | 348 (44.0) | 2338 (49.4) | ||

| 55+ | 292 (37.2) | 214 (27.4) | 239 (30.5) | 237 (29.6) | 190 (24.0) | 325 (41.1) | 1497 (31.6) | ||

| Ethnicity | |||||||||

| Other | 42 (5.4) | 40 (5.1) | 11 (1.4) | 11 (1.4) | 125 (15.8) | 6 (0.8) | 235 (5.0) | ||

| Han* | 743 (94.6) | 741 (94.9) | 773 (98.6) | 789 (98.6) | 666 (84.2) | 785 (99.2) | 4497 (95.0) | ||

| Income | |||||||||

| Low | 74 (9.4) | 244 (31.2) | 113 (14.4) | 226 (28.3) | 174 (22.0) | 94 (11.9) | 925 (19.6) | ||

| Medium | 323 (41.2) | 435 (55.7) | 348 (44.4) | 335 (41.9) | 396 (50.1) | 295 (37.3) | 2132 (45.1) | ||

| High | 322 (41.1) | 79 (10.1) | 291 (37.2) | 198 (24.8) | 156 (19.7) | 286 (36.2) | 1332 (28.2) | ||

| Don’t know | 65 (8.3) | 23 (2.9) | 31 (4.0) | 41 (5.1) | 64 (8.1) | 116 (14.7) | 340 (7.2) | ||

| Education | |||||||||

| Low | 76 (9.7) | 60 (7.7) | 47 (6.0) | 142 (17.8) | 107 (13.5) | 188 (23.9) | 620 (13.1) | ||

| Medium | 496 (63.2) | 570 (73.1) | 588 (75.0) | 486 (60.8) | 486 (61.5) | 472 (59.9) | 3098 (65.5) | ||

| High | 213 (27.1) | 150 (19.2) | 149 (19.0) | 172 (21.5) | 197 (24.9) | 128 (16.2) | 1009 (21.3) | ||

| Daily/weekly smoking | |||||||||

| Daily smoker | 730 (93.0) | 733 (93.9) | 742 (94.6) | 749 (93.6) | 721 (91.2) | 747 (94.4) | 4422 (93.4) | ||

| Weekly smoker | 55 (7.0) | 48 (6.1) | 42 (5.4) | 51 (6.4) | 70 (8.8) | 44 (5.6) | 310 (6.6) | ||

| Cigarettes per day | |||||||||

| 1–10 | 299 (38.4) | 292 (37.5) | 266 (34.0) | 194 (24.4) | 336 (42.7) | 253 (32.2) | 1640 (34.8) | ||

| 11–20 | 374 (48.0) | 372 (47.8) | 389 (49.7) | 407 (51.3) | 356 (45.3) | 409 (52.0) | 2307 (49.0) | ||

| 21–30 | 58 (7.4) | 68 (8.7) | 71 (9.1) | 87 (11.0) | 48 (6.1) | 73 (9.3) | 405 (8.6) | ||

| 31+ | 48 (6.2) | 46 (5.9) | 57 (7.3) | 106 (13.4) | 46 (5.9) | 51 (6.5) | 354 (7.5) | ||

| Ever tried light, low tar | |||||||||

| Yes | 443 (56.4) | 329 (42.1) | 467 (59.6) | 303 (37.9) | 407 (51.5) | 417 (52.7) | 2366 (50.0) | ||

| No | 316 (40.3) | 410 (52.5) | 295 (37.6) | 447 (55.9) | 321 (40.6) | 334 (42.2) | 2123 (44.9) | ||

| Don’t know | 26 (3.3) | 42 (5.4) | 22 (2.8) | 50 (6.3) | 63 (8.0) | 40 (5.1) | 243 (5.1) | ||

| Tar level | |||||||||

| Don’t know | 282 (36.6) | 284 (38.1) | 246 (31.5) | 400 (50.1) | 230 (29.3) | 321 (40.9) | 1763 (37.8) | ||

| Invalid tar level | 4 (0.5) | 2 (0.3) | 11 (1.4) | 6 (0.8) | 8 (1.0) | 4 (0.5) | 35 (0.8) | ||

| 15 mg | 202 (26.2) | 204 (27.3) | 310 (39.6) | 38 (4.8) | 208 (26.5) | 335 (42.7) | 1297 (27.8) | ||

| 11–14 mg | 169 (21.9) | 235 (31.5) | 103 (13.2) | 349 (43.7) | 326 (41.5) | 107 (13.6) | 1289 (27.6) | ||

| 10 mg or less | 113 (14.7) | 21 (2.8) | 112 (14.3) | 5 (0.6) | 14 (1.8) | 17 (2.2) | 282 (6.0) | ||

Han is the majority ethnicity in China; approximately 91.6% of the national population is Han.27

Procedure

In each of the six cities, the survey team led by investigators at the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention selected 10 Jie Dao (street districts), with the probability of selection proportional to size. Within each Jie Dao, two Ju Wei Hui (residential blocks) were selected, again with the probability of selection proportional to size. Within each Ju Wei Hui, the addresses of all households were listed and a sample of 300 addresses was randomly selected without replacement.

Among these 300 households, basic information was collected on every person over the age of 18 to determine eligibility for the survey. From these 300 households, 50 people were randomly selected to participate in the survey (40 adult smokers and 10 adult non-smokers). The “next birthday method” was used to select the respondent in households with more than one eligible respondent.25

The smoker survey was a 40-minute face-to-face survey conducted in Mandarin by experienced survey interviewers specially trained to conduct the ITC China survey. Further details about the team structure are available in the ITC China Wave 1 technical report.26 Respondents were given a small gift (soap) worth 10–20 Yuan in appreciation for their participation. This compensation is typical for survey participation in China.

The ITC China Survey was constructed with reference to ITC surveys being conducted in 14 other countries. The survey and training manual were translated from English into Chinese and standardised across all cities. The survey fieldwork was supervised by members of the local Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in each of the six cities and was coordinated by the China National CDC and the ITC Project Data Management Centre at the University of Waterloo. Research ethics approval was obtained from the University of Waterloo, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, the Cancer Council Victoria, and the Chinese National CDC.

Sampling weights were constructed separately for male smokers, female smokers, and non-smokers. Wave 1 weight construction accounted for four levels of sample selection: Jie Dao, Ju Wei Hui, household, and individual. The final Wave 1 weight for a sampled individual was the number of people in the city population and the sampling category represented by that individual.

For additional information about the methods of the ITC China Survey see Wu et al28 and the ITC China Survey Technical Report.26

Measures

Beliefs about “light” and/or “low tar” cigarettes

Respondents were asked whether they strongly agree, agree, neither agree or disagree, disagree, strongly disagree or don’t know with each of two statements: “low tar cigarettes are less harmful than regular cigarettes” and “light cigarettes are less harmful than regular cigarettes.” Although the terms “light” and “low tar” are often used synonymously, separate questions were asked in order to ensure that we captured all possible awareness of these types of cigarettes. The term “low tar” is used in China both in marketing the product as “low tar” and also because of the tar levels on cigarette packaging. “Light” descriptors are typically written in English only on cigarette packages. Thus only those who read English would understand the meaning. The terms were similar enough, however, that we collapsed responses across beliefs about “light” and “low tar” cigarettes.

Responses were recoded so that “strongly agree” and “agree” were coded as 1 and other responses coded as 0. Beliefs about “light” and “low tar” cigarettes were combined so that having one or both of these beliefs was coded 1 and having neither of these beliefs was coded 0. Before collapsing across beliefs about “light” and “low tar” cigarettes we tested each model separately. The results were similar to those we obtained when combining beliefs about “light” and “low tar” cigarettes.

Demographics and smoking behaviour

Standard demographic measures included sex, ethnicity (Han vs other ethnic groups), age (18–39, 40–54, 55+; there were few respondents (1.4%) in the 18–24 category and it was therefore collapsed with the 25–39 category), household income per month (low: <1000 yuan per month, medium: ≥1000 yuan and ≤2999 yuan per month, high: ≥3000 yuan, don’t know), education (low: no education or elementary school, medium: junior high school or high school/technical high school, high: college, university or higher) and city. Daily cigarette smokers responded “every day” to the question: “Do you smoke every day, less than every day, or not at all?” and weekly smokers indicated that they smoked “less than every day”. Cigarettes smoked per day was calculated by asking daily smokers: “On average, how many cigarettes do you smoke each day, including both factory-made and hand-rolled cigarettes?” and weekly smokers: “On average, how many cigarettes do you smoke each week?” (divided by 7). Impossible per day values (greater than 100) were treated as coding errors and recoded as 100. In the logistic regression equation, cigarettes per day was centred and treated as a continuous variable.

Knowledge of health effects of smoking

Respondents were asked whether smoking causes stroke, impotence, lung cancer in smokers, emphysema in smokers, stained teeth, premature ageing, lung cancer in non-smokers and cardiovascular heart disease. Responses were coded so that no and don’t know/cannot say=0 and yes=1. The measure of health knowledge was the sum of all eight responses. The Cronbach α for this measure was 0.79, suggesting that the scale was reliable.

Self-reported use of “light” and “low tar” cigarettes

We asked respondents whether they had ever tried cigarettes described as “light,” “mild” or “low tar” (yes, no or don’t know). We also asked respondents to provide the tar level of the brand they currently smoked most often. Responses were coded as 1=≤10 mg of tar, 2=≥11 mg of tar to ≤14 mg of tar, 3=15 mg of tar, 4=invalid tar level and 5=don’t know. Because China banned cigarettes above 15 mg of tar, any respondent who reported greater than 15 mg was given an invalid code and treated as a separate category.

Health concerns about smoking

To assess health concerns, respondents were asked: “to what extent, if at all, has smoking damaged your health?” and “how worried are you, if at all, that smoking will damage your health in the future?” (not at all/don’t know, a little, very much). We also asked smokers to rate their health with response options from 1=poor to 5= excellent. Smokers were asked whether they considered themselves addicted to cigarettes (not at all, a little, somewhat, a lot).

Quitting related variables

We asked respondents whether they had ever tried to quit smoking (yes or no). Quit intentions were assessed by asking respondents: “are you planning to quit smoking?” (within the next month, within the next 6 months, sometime in the future, beyond 6 months, not planning to quit/don’t know). To assess quitting efficacy respondents were asked: “if you decided to give up smoking completely in the next 6 months, how sure are you that you would succeed?” (not at all sure, somewhat sure, very sure, extremely sure, don’t know).

Smoothness beliefs

Respondents were asked whether they strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, strongly disagree or don’t know with the statements: “low tar cigarettes are smoother on your respiratory system than regular cigarettes”, and “light cigarettes are smoother on your respiratory system than regular cigarettes”. (Surveys typically ask “Do light cigarettes feel smoother on the throat and chest?” However, in Chinese, this question was interpreted as referring to outside the throat and chest. To capture the sensation within the throat and chest, our Chinese translation team suggested the translation should be “on the respiratory system”.)

Responses were recoded so that “strongly agree” and “agree” were coded as 1 and other responses coded as 0. Again, beliefs about “light” and “low tar” cigarettes were combined so that having one or both of these beliefs was coded as 1 and having neither of these beliefs was coded as 0.

Statistical analyses

SPSS (version 17) was used for all statistical analyses. A complex samples logistic regression model was used to test which variables were independently associated with the beliefs that LLT cigarettes are less harmful. All analyses were conducted on weighted data. These predictors were related to beliefs that “light” cigarettes confer health benefits among smokers in the ITC Four Country Survey.15

Results

Half (50.0% unweighted; 48.5% weighted) of the respondents reported having ever tried a cigarette described as “light”, “mild” or “low tar” (table 1). Approximately 28% of respondents reported their current brand had 15 mg of tar, 27.6% had a brand with 11–14 mg of tar, and 6% had a brand with 10 mg of tar or less. Reported use of “light” and “low tar” cigarettes varied by city with lower tar cigarette brands being more common in more Westernised cities (Beijing, Shanghai).

Beliefs about “light” and/or “low tar” cigarettes

Table 2 presents overall beliefs about “light” and “low tar” cigarettes. The majority of smokers (71.0%) believed that LLT cigarettes are less harmful and that LLT cigarettes are smoother on the respiratory system (73.3%).

Table 2.

Weighted beliefs about the relative harm and sensory characteristics of “light” and “low tar” cigarettes and inter-item correlations

| Belief | “Light” less harmful | “Low tar” less harmful | LLT less harmful | “Light” smoother | “Low tar” smoother | LLT smoother | % Agree or strongly agree with belief item | 95% CI for belief item |

| “Light” cigarettes are less harmful than regular cigarettes | 1 | 55.7 | 52.8% to 58.6% | |||||

| “Low tar” cigarettes are less harmful than regular cigarettes | 0.51 | 1 | 62.0 | 59.4% to 64.4% | ||||

| LLT cigarettes are less harmful | 0.72 | 0.83 | 1 | 71.0 | 68.4% to 73.5% | |||

| “Light” cigarettes are smoother on your respiratory system than regular cigarettes | 0.76 | 0.49 | 0.63 | 1 | 60.4 | 57.5% to 63.2% | ||

| “Low tar” cigarettes are smoother on your respiratory system than regular cigarettes | 0.46 | 0.68 | 0.60 | 0.48 | 1 | 61.4 | 58.9% to 63.9% | |

| LLT cigarettes are smoother on your respiratory system than regular cigarettes | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.73 | 0.75 | 0.76 | 1 | 73.3 | 70.7% to 75.8% |

Factors associated with the belief that “light” and/or “low tar” cigarettes are less harmful

Table 3 presents the results of a logistic regression analysis to determine what factors were independently associated with the belief that LLT cigarettes are less harmful. Smokers in the oldest age category were more likely than smokers in the youngest category to believe that LLT cigarettes are less harmful (p<0.001, OR=1.97 CI 1.36 to 2.87). Compared to people with a high education, people who were low educated were significantly less likely to believe that LLT cigarettes are less harmful (p=0.007, OR=0.55 CI 0.34 to 0.89).

Table 3.

Weighted logistic regression of belief “light”/“low tar” cigarettes are less harmful

| Factor | No | % of smokers believing LLT cigarettes are less harmful* | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | p Value |

| Demographic variables | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 4499 | 71.1 | 0.84 (0.60 to 1.18) | 0.31 |

| Female | 233 | 70.5 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–39 | 897 | 67.4 | 1.00 (reference) | <0.001 |

| 40–54 | 2338 | 70.3 | 1.17 (0.87 to 1.57) | |

| 55+ | 1497 | 74.4 | 1.97 (1.36 to 2.87) | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Other | 235 | 62.2 | 0.93 (0.55 to 1.56) | 0.77 |

| Han | 4497 | 71.5 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Income | ||||

| Don’t know | 340 | 61.5 | 1.05 (0.69 to 1.59) | 0.20 |

| Low | 925 | 69.1 | 1.27 (0.90 to 1.80) | |

| Medium | 2132 | 73.6 | 1.50 (1.01 to 2.23) | |

| High | 1332 | 70.6 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Education | ||||

| Low | 620 | 64.2 | 0.55 (0.34 to 0.89) | 0.007 |

| Medium | 3098 | 72.6 | 0.85 (0.55 to 1.31) | |

| High | 1009 | 70.9 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| City | ||||

| Beijing | 785 | 74.7 | 1.36 (0.85 to 2.18) | 0.46 |

| Shenyang | 781 | 74.6 | 1.47 (1.00 to 2.17) | |

| Shanghai | 784 | 66.5 | 1.19 (0.75 to 1.89) | |

| Changsha | 800 | 72.3 | 1.33 (0.88 to 1.99) | |

| Yinchuan | 791 | 67.3 | 1.27 (0.89 to 1.83) | |

| Guangzhou | 791 | 70.9 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Smoking behaviour | ||||

| Daily/weekly smoking | ||||

| Daily smoker | 4422 | 70.7 | 0.81 (0.53 to 1.22) | 0.30 |

| Weekly smoker | 310 | 75.3 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Cigarettes per day | ||||

| 0–10 | 1640 | 72.2 | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.03)† | 0.53 |

| 11–20 | 2307 | 71.0 | ||

| 21–30 | 405 | 65.5 | ||

| 31+ | 354 | 73.6 | ||

| Health knowledge | ||||

| 0 | 360 | 56.8 | 1.01 (0.94 to 1.08)† | 0.84 |

| 1 | 570 | 59.4 | ||

| 2 | 502 | 69.9 | ||

| 3 | 610 | 74.5 | ||

| 4 | 665 | 76.7 | ||

| 5 | 760 | 76.8 | ||

| 6 | 602 | 75.4 | ||

| 7 | 375 | 71.4 | ||

| 8 | 261 | 70.2 | ||

| Ever tried light, low tar | ||||

| No | 2123 | 68.6 | 0.91 (0.68 to 1.22) | 0.63 |

| Don’t know | 243 | 68.6 | 1.11 (0.66 to 1.85) | |

| Yes | 2366 | 73.6 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Tar level | ||||

| Don’t know | 1763 | 71.4 | 0.72 (0.42 to 1.21) | 0.19 |

| Invalid tar level | 35 | 61.4 | 0.38 (0.15 to 0.96) | |

| 15 mg | 1297 | 69.5 | 0.61 (0.37 to 1.01) | |

| 11–14 mg | 1289 | 72.0 | 0.71 (0.44 to 1.14) | |

| 10 mg or less | 282 | 76.5 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Health concern | ||||

| Worried smoking has damaged health | ||||

| Very | 770 | 76.1 | 1.08 (0.75 to 1.55) | 0.48 |

| A little | 1973 | 75.9 | 1.17 (0.91 to 1.52) | |

| Not at all/don’t know | 1983 | 64.3 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Worried smoking will damage health | ||||

| Very | 855 | 77.0 | 1.22 (0.80 to 1.87) | 0.30 |

| A little | 1984 | 75.7 | 1.23 (0.95 to 1.59) | |

| Not at all/don’t know | 1890 | 63.3 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Describe your health | ||||

| 1 Poor | 131 | 72.7 | 1.04 (0.86 to 1.26)† | 0.68 |

| 2 | 273 | 66.5 | ||

| 3 | 2218 | 72.0 | ||

| 4 | 1445 | 70.6 | ||

| 5 Excellent | 653 | 70.4 | ||

| Perceived addiction | ||||

| A little | 2132 | 72.3 | 1.09 (0.69 to 1.72) | 0.81 |

| Somewhat | 1359 | 71.9 | 1.22 (0.70 to 2.14) | |

| A lot | 515 | 67.0 | 1.18 (0.49 to 2.82) | |

| Not at all | 666 | 70.4 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Quitting | ||||

| Past quit attempt | ||||

| No | 2219 | 69.6 | 1.12 (0.78 to 1.61) | 0.52 |

| Yes | 2512 | 72.3 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Quit intention | ||||

| In the next month | 377 | 73.8 | 0.74 (0.48 to 1.13) | 0.53 |

| In the next 6 months | 297 | 77.0 | 0.80 (0.45 to 1.42) | |

| In the future beyond 6 months | 437 | 77.3 | 0.92 (0.59 to 1.43) | |

| No intention/don’t know | 3602 | 69.6 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Quit efficacy | ||||

| Don’t know | 334 | 61.3 | 1.20 (0.70 to 2.06) | 0.68 |

| Extremely sure | 612 | 71.1 | 0.94 (0.61 to 1.44) | |

| Very sure | 622 | 73.4 | 1.13 (0.71 to 1.80) | |

| Somewhat sure | 1158 | 76.8 | 1.21 (0.91 to 1.61) | |

| Not at all sure | 2004 | 68.5 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Light/low tar smoother | ||||

| Agree/strongly Agree | 3451 | 90.9 | 53.87 (41.28 to 70.31) | <0.001 |

| Disagree/strongly disagree/neutral/DK | 1280 | 16.4 | 1.00 (reference) |

The belief prevalences presented for each response category of each factor are not adjusted for the other predictor variables in the model.

Continuous variable.

By far the strongest predictor of the misconception that LLT cigarettes are less harmful was the belief about the sensory perception of LLT cigarettes. Smokers who thought that LLT cigarettes are smoother on the respiratory system were significantly more likely to believe that LLT cigarettes are less harmful (p<0.001, OR=53.87, CI 41.28 to 70.31). Of the smokers who believed that LLT cigarettes are smoother on the respiratory system, 90.9% said that these cigarettes are less harmful than regular cigarettes. In sharp contrast, among those who did not believe that LLT cigarettes are smoother on the respiratory system, only 16.4% believed that these cigarettes are less harmful.

Interactions with the belief that “light” and/or “low tar” cigarettes are smoother

We tested interactions between the smoother belief and each variable. It should be noted that the main effect for smoother belief was enormous, and so even if there exist statistically significant interactions, the effect of those interactions would be differences around a main effect corresponding to an odds ratio of 53.

Among smokers who ever used “light” or “low tar” cigarettes, those who believed that these types of cigarettes are smoother have significantly greater odds of believing that LLT cigarettes are less harmful than those who did not believe that these cigarettes are smoother (p<0.001, OR=40.03, CI=28.59 to 56.03). Those who never used “light” or “low tar” cigarettes and who believed that these types of cigarettes are smoother were more likely to believe that LLT cigarettes are less harmful than those who did not believe that these cigarettes are smoother (p<0.001, OR=71.52, CI=50.86 to 100.57). The relation between smoothness and less harm was therefore stronger for those who had never tried “light” or “low tar” cigarettes compared to those who had tried “light” or “low tar” cigarettes (p=0.004, OR=1.79, CI 1.22 to 2.62).

There was no significant interaction between the tar level of the respondent's current brand and the belief that LLT cigarettes are smoother predicting the belief that these cigarettes are less harmful. Few other predictors interacted with the perception that LLT cigarettes are smoother to predict the belief that they are less harmful. There was a significant overall interaction by city (p=0.02) and education (p=0.006). In every case, those who believed that LLT cigarettes are smoother were more likely to believe that LLT cigarettes are less harmful (the lowest odds ratio was 25.6 and the highest odds ratio was 85.5).

Discussion

Over two-thirds of Chinese smokers surveyed held the false belief that LLT cigarettes are less harmful. This is a much higher level of belief than smokers in Canada (16%), the US (28%), the UK (43%) and Australia (27%).15 This may be a reflection of marketing campaigns in China that continue to use explicit health claims. For example, a two-page spread magazine advertisement for one Chinese brand, “Zhongnanhai Light” cigarettes, claims “Every product fuses the world's most advanced low-harm cigarette technology, offering a guarantee of health for your smoking life.” Another print ad claims: “A little lower is healthier! Low-harm tobacco, more technological components, greater loving care for your body!” (see fig 1). Since the Chinese government has allowed these companies to make explicit health claims, even after the ban, it is not surprising that a relatively high number of smokers in China believe that these cigarettes are less harmful compared to conventional high tar yield brands.

Consistent with previous research that has found that the sensory experience of smoking “low tar” cigarettes with higher levels of filter ventilation reinforces the belief in reduced harm,14 we found that the factor most strongly associated with the belief that LLT cigarettes are less harmful was the belief that LLT cigarettes are smoother on the respiratory system. We also found a stronger association between the belief that LLT cigarettes are smoother on the airway and the belief that they are less harmful than regular cigarettes, among those who had never tried “light” or “low tar” cigarettes compared to those who had ever tried these cigarettes.

One might suspect that the experience of smoking LLT cigarettes would strengthen the belief that they are smoother because in most cases they would be smoother. However, the belief that LLT cigarettes are smoother is also communicated through package designs (that is, lighter colours), as well as descriptors that say “smooth”, “mellow”, etc. Perhaps the smoothness implied in marketing for these cigarettes differs from the actual smoking experience. Also, the fact that “light” and “low tar” cigarettes are only recently being introduced into the market is another factor that may account for the finding. In addition, there was no interaction between the tar level of the respondent's current brand and the belief that LLT cigarettes are less harmful. It should be pointed out that whatever the nature of the interaction, it was still the case for both groups that the relation between the smoother belief and the lower harm belief was very substantial.

Limitations

The findings reported in this article are from six cities in China. However, we can see no reason why they would not generalise to other urban Chinese cities as the cities in our study cover a broad range of economic and social conditions. There are plausible reasons why the findings might be somewhat different in rural China, where “light” cigarettes may be less likely to be promoted and there may be a smaller range of cigarette brands available. Still, with a starting point of an odds ratio of 53, we believe that it is extremely unlikely that the very strong relation would not hold across a very broad range of locations across all of China.

As with any survey research, there are always concerns about survey non-response and under-representation of certain groups. We addressed this issue by conducting weighted analyses for each city. Although we did have a low number of respondents in the youngest age category (18–24), this is consistent with samples from China's 1996 National Prevalence Study.22

Implications

In January 2006, China banned descriptors such as: “light”, “ultra-light”, “mild”, “medium/low tar”, “low tar”, “low tar content” on cigarette packaging and inserts. However, the tobacco industry was given a period of grace until April 2006. In addition, sources in China have indicated that although the Chinese terms for “light”, etc, have been removed, the English descriptors are not covered under this ban and remain on cigarette packages. Because our survey started in April 2006, we were unable to evaluate the initial impact of the ban, although we did not expect any immediate impact of the ban, rather we expected any changes in beliefs to take time. In follow-up surveys with this cohort of smokers we will be able to measure whether perceptions about these brands will change as time from the ban elapses. What is known is that the majority of adult smokers in China hold the erroneous belief that LLT cigarettes are less harmful than conventional high yield cigarettes. Smokers in China, like those throughout the world, need to be educated that all combustion tobacco products are harmful and that there is no compelling evidence to support a meaningful difference in health risk between products no matter what the marketing claims might suggest.

These findings demonstrate the need for China to also consider banning advertising that supports the idea that certain cigarettes are less harmful than others, as well as the need to remove tar numbers from cigarette packages. China has joined other countries (for example, Thailand, Australia and the United Kingdom) to ban “light” and “mild” descriptors on cigarette packages. However, research suggests banning these terms may not be sufficient to change beliefs about the relative harm of “light” cigarettes at least in the short term.25 Our findings highlight the importance of the association between the belief that these cigarettes are smoother on the respiratory system and the relative harmfulness of “light” and “low tar” cigarettes. Banning “light” or “low tar” descriptors does nothing to break the link between the lighter and smoother physical sensations associated with “light” and “low tar” cigarettes and their presumed harmfulness. The association between the physical aspects of these cigarettes and their relative harm can certainly be created from package designs, advertising, descriptors, but our findings point to the powerful association created by the product itself that may provide illusory messages directly to the smoker that some brands are less harmful than others.

In addition, Articles 9 and 10 of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC)29 relate to the regulation of tobacco products and these results point to the need to regulate the product to ban design features that would make a product smoother and lighter in sensation. Doing so could reduce perceptions of lower harm, which may be a key factor in increasing motivation to quit smoking.

What this paper adds.

This is the first study to examine beliefs about “light” and “low tar” cigarettes among smokers in China, the world's largest consumer of tobacco. There was a very strong relation between the belief that “light” and/or “low tar” cigarettes are smoother on the respiratory system and the belief that “light” and/or “low tar” cigarettes are less harmful. The findings suggest that future tobacco control policies should go beyond eliminating labelling and marketing that promotes “light” and “low tar” cigarettes (the focus of Article 11 of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC)), and address the tobacco product characteristics (for example, additives, filter vents) that reinforce the belief that “light” and “low tar” cigarettes are less harmful (Articles 9 and 10 of the FCTC).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Chinese National Centers for Disease Control and the local CDC representatives in each city for their role in data collection. The authors would also like to thank the three reviewers and the editor for their revisions to the manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding: Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Canada (No 79551), National Cancer Institute (NCI)/National Institute of Health (NIH R01 CA125116-01A1), Roswell Park Transdisciplinary Tobacco Use Research Center (TTURC- P50 CA111236), funded by the US National Cancer Institute, with additional support from a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Canada Graduate Scholarship Master's Award, a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Doctoral Research Award, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Strategic Training Program in Tobacco Research. The Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention was responsible for data collection. Sponsors did not determine the data analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was obtained from the Office of Research at the University of Waterloo (Waterloo Canada), and the internal review boards at Roswell Park Cancer Institute (Buffalo, USA), the Cancer Council Victoria (Victoria, Australia) and the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention (Beijing, China).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Towards a tobacco-free China. Geneva: WHO, 2007: available at: http://www.wpro.who.int/china/sites/tfi/ (accessed 15 August 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization Report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2008: the MPOWER package. Geneva: WHO, 2008: available at: http://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/mpower_report_full_2008.pdf (accessed 20 June 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray CJL, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: global burden of disease study. Lancet 1997;349:1498–1504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson SJ, Pollay RW, Ling PM. Taking advantage of lax advertising regulation in the USA and Canada: reassuring and distracting health-concerned smokers. Soc Sci Med 2006;63:1973–1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pollay RW, Dewhirst T. The dark side of marketing seemingly “light” cigarettes: successful images and failed fact. Tob Control 2002;11(suppl 1):i18–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pollay RW. Targeting youth and concerned smokers: evidence from Canadian tobacco industry documents. Tob Control 2000;9:136–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shiffman S, Pillitteri JL, Burton SL, et al. Smokers’ beliefs about “light” and “ultra light” cigarettes. Tob Control 2001;10(suppl 1):i17–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borland R, Yong HH, King B, et al. Use of and beliefs about light cigarettes in four countries: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Survey. Nicotine Tob Res 2004;6(suppl 3):S311–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kropp RY, Halpern-Felsher BL. Adolescents’ beliefs about the risks involved in smoking “light” cigarettes. Pediatrics 2004;114:e445–e451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kozlowski LT, Goldberg ME, Yost BA, et al. Smokers’ misperceptions of light and ultra-light cigarettes may keep them smoking. Am J Prev Med 1998;15:9–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilpin EA, Emery S, White MM, et al. Does tobacco industry marketing of “light” cigarettes give smokers a rationale for postponing quitting? Nicotine Tob Res 2002;4(suppl 2):S147–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hyland A, Hughes JR, Farrelly M, et al. Switching to lower tar cigarettes does not increase or decrease the likelihood of future quit attempts or cessation. Nicotine Tob Res 2003;5:665–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammond D, Fong GT, Cummings KM, et al. Smoking topography, brand switching, and nicotine delivery: results from an in vivo study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005;14:1370–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kozlowski LT, O'Connor RJ, Sweeney CT. Cigarette design. In: Risks associated with smoking cigarettes with low machine-measured tar and nicotine yields. NCI Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No 13. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 2001:13–38 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benowitz NL. Compensatory smoking of low-yield cigarettes. In: Risks associated with smoking cigarettes with low machine-measured tar and nicotine yields. NCI Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No 13. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 2001:39–63 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hammond D, Collishaw NE, Callard C. Secret science: tobacco industry research on smoking behaviour and cigarette toxicity. Lancet 2006;367:781–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hecht SS, Murphy SE, Carmella SG, et al. Similar uptake of lung carcinogens by smokers of regular, light, and ultralight cigarettes. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005;14:639–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thun MJ, Burns DM. Health impact of “reduced yield” cigarettes: a critical assessment of the epidemiological evidence. Tob Control 2001;10(suppl 1):i4–i11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Philip Morris [People's Republic of China 920000-940000 plan]. 1992. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2504007962 http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rcq19e00 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Euromonitor International The world market for tobacco. March 2006; available at: http://www.euromonitor.com/The_World_Market_for_Tobacco (purchase required) (accessed 9 August 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang G, Fan L, Tan J, et al. Smoking in China: findings of the 1996 National Prevalence Survey. JAMA 1999;282:1247–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang G, Ma J, Chen A, et al. Smoking cessation in China: findings from the 1996 national prevalence survey. Tob Control 2001;10:170–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shiffman S, Pillitteri JL, Burton SL, et al. Effect of health messages about “light” and “ultra light” cigarettes on beliefs and quitting intent. Tob Control 2001;10(suppl 1):i24–i32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borland R, Fong GT, Yong HH, et al. What happened to smokers’ beliefs about light cigarettes when “light/mild” brand descriptors were banned in the UK? Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control 2008;17:256–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Binson D, Canchola JA, Catania JA. Random selection in a national telephone survey: a comparison of the Kish, next-birthday, and last-birthday methods. J Off Stat 2000;16:53–60 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wave 1 ITC China Technical Report Waterloo, Canada: International Tobacco Control China Survey Team, June 2008. Available at: http://www.itcproject.org/library/countries/itcchina/reports/finalitcch (accessed 17 June 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Bureau of Statistics of China China Statistical Yearbook 2008. Available at: http://www.itcproject.org/library/countries/itcchina/reports/cn1techrptrevjul72010.pdf (accessed 22 Sep 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu C, Thompson ME, Fong GT, et al. Methods of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) China Survey. Tob Control 2010;19(Suppl 2):i1–i5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2005; Available at: http://www.who.int/tobacco/framework/WHO_FCTC_english.pdf (accessed 6 February 2008). [Google Scholar]