Abstract

Background

Despite different levels of economic development, Costa Rica and the USA have similar mortalities among adults. However, in the USA there are substantial differences in mortality by educational attainment, and in Costa Rica there are only minor differences. This contrast motivates an examination of behavioural and biological correlates underlying this difference.

Methods

The authors used data on adults aged 60 and above from the Costa Rican Longevity and Healthy Ageing Study (CRELES) (n=2827) and from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) (n=5607) to analyse the cross-sectional association between educational level and the following risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD): ever smoked, current smoker, sedentary, high saturated fat, high carbohydrates, high calorie diet, obesity, severe obesity, large waist circumference, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, hemoglobin A1c, fasting glucose, C-reactive protein, systolic blood pressure and BMI.

Results

There were significantly fewer hazardous levels of risk biomarkers at higher levels of education for more than half (10 out of 17) of the risk factors in the USA, but for less than a third of the outcomes in Costa Rica (five out of 17).

Conclusions

These results are consistent with the context-specific nature of educational differences in risk factors for CVD and with a non-uniform nature of association of CVD risk factors with education within countries. Our results also demonstrate that social equity in mortality is achieved without uniform equity in all risk factors.

Keywords: Heart disease, international collaboration, social differences, social inequalities

Introduction

While, in developed Western countries1 2 and some non-Western countries,3 there is generally an association of lower educational attainment with greater risk of mortality, others have described the historically contingent and contextually specific nature of such associations.4 A recently documented example of a different mortality pattern with respect to educational attainment is among older individuals in Costa Rica. While there are higher rates of mortality among children of mothers with less than a primary school education,5 there are relatively minor associations between mortality and education in Costa Ricans age 60 and above.6 While education differentials in mortality are generally smaller at older ages,7 recent analysis in the USA of similar aged individuals reveal substantial differentials by education, with mortalities 5–6% higher per year for each year less of education.8

Costa Rica is a case of particular interest because of its historic emphasis on progressive social and health sector programmes. The country began investing in female education in the late 19th century, abolished the army in the mid-20th century, invested heavily in public health initiatives such as clean water, has strongly promoted primary care initiatives in its medical sector and adopted national health insurance in the 1970s. Costa Rica's high overall life expectancy (higher even than the USA) has been linked to its social investments,9 but until the recent Costa Rican Longevity and Healthy Ageing Study (CRELES), few data have been available to understand why there is a lack of social class differences in older adult mortality in Costa Rica.

There have been several hypotheses for explaining the aggregated general associations of adult mortality and education. One of these is the theory of social conditions as fundamental causes of disease.10 11 This theory posits that socio-economic resources, for example, as measured by educational attainment, affect multiple risk factors for diseases. This is posited to occur through the ability of people to use resources to avoid multiple causes of risk—and implies some similarity of the association of education with multiple pathways to disease outcomes. Other theories involve the primacy of factors including technical progress in medical care,12 13 the importance of time preferences,14 15 social rank16 or income inequality.17 Within each of these proposed drivers of socio-economic heterogeneity in mortality, proponents generally do not focus on particular pathways but imply more general effects on disease processes. An alternative explanation of the mortality education association is that a more complex pattern of the association of education and biological pathways exists. The associations may not be of a uniform magnitude or even direction. These different associations between education and risk factors may instead combine to create the educational differences observed for mortality. Whether data are more consistent with either of these potential explanations has important implications for policies to decrease the link between lower levels of education and higher rates of mortality.

We focus here on risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) because (1) a substantial part of the education disparities in mortality in the USA is from CVD,18 (2) roughly 40% of deaths at ages 60 and over in Costa Rica are due to cardiovascular diseases,19 and (3) risk factors are relatively well characterised. While CVD is a heterogeneous category, and there are some differences in the risk factors for the specific causes of death within it (eg, early life exposures for haemorragic stroke),20 known risk factors explain the majority of cases of CVD.21 22

Our approach to understanding the different associations of education and mortality in Costa Rica and the USA is to examine the relative strength of education gradients in risk factors for CVD, both biological and behavioural. Our choice of risk factors was guided by the published guidelines of the American Heart Association,23 the American College of Cardiology24 25 and the WHO.26 We examined risk factors that together explain the majority of CVD risk,23 27 and there are no substantial variations between countries in the risk factors predicting CVD.28 While many of these risk factors are correlated, we include each of these risks separately because of potentially different associations with education. Exposures over the life course may affect levels of certain biological risk markers,29–32 in addition to current behaviours.33 Thus, while our analysis of behavioural risk factors focuses on current assessment of exposures, the biomarkers and anthropometric measures should be interpreted as the cumulative result of exposures over the lifespan.34

Methods

Samples

Data from Costa Rica are from the Costa Rican Longevity and Healthy Ageing Study (CRELES), a nationally representative, probabilistic sample of adults aged 60 and over (from a population of approximately 350 000) selected from the 2000 census database.35 A selected subsample of this population (n=1329 men, n=1498 women) with oversampling of the oldest old completed a survey in their household between November 2004 and September 2006 which is the basis of the analytical sample. This subsample had the following non-response rates: 19% of individuals were deceased by the contact date, 18% could not be found, 2% had moved, and 4% rejected the interview. Among those interviewed, 95% provided a fasting blood sample.

Data from the USA are from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2004, restricted to adults aged 60 and over (n=2411 men, n=3196 women). These cross-sectional data are representative of the non-institutionalised population of the USA. NHANES follows a four-stage sampling procedure where the primary sampling units are counties, within which city blocks are selected. Within these blocks, households are then randomly selected, and then individuals are drawn at random from designated age–race/ethnicity–sex subdomains.36

This research was approved by Human Subject committees at Universidad de Costa Rica and University of California, Berkeley.

Demographic, health-related behaviours and dietary measures

Our primary exposure of interest is attained level of formal education. Since the absolute level of educational attainment has different social and economic meaning in each country, it does not make sense to use the same categories of education. For Costa Rica, educational attainment was categorised into three groups: less than 3 years of education, 3–6 years of education (elementary school comprises six grades), and at least 1 year of high school. For the USA, we use the educational categories of less than high school, high school or greater than high school. We performed sensitivity analyses with Costa Rican educational categories of none, 1–5 years of education (some primary) and 6 years or more (completed primary), and findings were generally similar (results shown in supplemental data tables S1 and S2).

In both NHANES and CRELES, ever smoked was assessed by the question ‘Have you smoked more than 100 cigarettes or cigars in your life?’ and current smoking was assessed by the question ‘Do you smoke now?’ In CRELES, sedentary behaviour was defined as participants responding ‘no’ to the question ‘In the last 12 months, did you exercise regularly or do other physical rigorous activities like sports, jogging, dancing or heavy work, three times a week?’ In NHANES, sedentary behaviour was assessed by whether individuals reported physical activity fewer than 13 times in the last 30 days, and answered ‘No’ to the question of ‘you do heavy work or carry heavy loads’ as an average level of physical activity each day.

CRELES collected dietary data using a modified version of a food-frequency questionnaire (FFQ) that was developed and validated specifically to assess nutrient intake among the Costa Rican adult population.37 38 Dietary averages in NHANES were based on calculations from two 24 h dietary recalls.39 Standard cut points associated with differential risk of cardiovascular disease were used to create dichotomous variables as follows: high-saturated-fat diet (>40 g per day), high-carbohydrate diet (>400 g per day) and high-calorie diet (>3000 kcal/day).

Anthropometric and biomarker outcomes

For anthropometric measures, we examine BMI (as continuous), obese (BMI >30), severely obese (BMI >40) and large waist (>102 cm among men, >88 cm among women). In both studies, height and weight were measured, and waist circumference was measured at the midaxillary line.

The seven biomarkers examined were high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL cholesterol), low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL cholesterol), triglycerides, glycosylated hemoglobin (hemoglobin A1c), fasting glucose, systolic blood pressure and C-reactive protein (CRP). All biomarkers were measured using similar methods in both countries. Sitting systolic blood pressure was measured twice in CRELES40 and up to four times n NHANES.41 When multiple blood pressure readings were taken, the first reading was excluded from the average (if only two measures were taken, the second reading was used).41

Statistical analysis

All analyses accounted for oversampling and clustered sampling using the survey package in STATA 10 (StataCorp, Texas, USA). Sampling weights and clustering were at the PSU level (n=49) in NHANES and at the health area level in CRELES (n=60). Continuous outcomes were analysed using linear regression, and dichotomous outcomes were analysed using logistic regression, controlling for age and age squared. Because there were statistically significant interactions between education and gender for a number of outcomes in both countries (data not shown, available upon request), all analyses are presented stratified by gender. In NHANES, analyses of blood glucose, LDL cholesterol and triglycerides were examined only in the randomly assigned fasting subsample (n=1016 men, n=1065 women).

Results

Table 1 shows the distribution of demographic characteristics, health behaviours, dietary averages, anthropometric measures and prevalent health conditions in CRELES and NHANES by gender.

Table 1.

Demographic and health-related characteristics of Costa Rica (Costa Rican Longevity and Healthy Ageing Study) and the USA (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) (column proportions)

| Costa Rica | USA | |||

| n=1329 | n=1498 | n=2411 | n=3196 | |

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Demographic | ||||

| Age | ||||

| 60–64 | 0.31 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.24 |

| 65–74 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.44 | 0.40 |

| 75–84 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.29 |

| >85 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.08 |

| Education (Costa Rica/USA) | ||||

| <3 years elementary/<high school | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.31 |

| >=3 years elementary/high school | 0.49 | 0.52 | 0.24 | 0.32 |

| At least 1 year high school/>high school | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.46 | 0.36 |

| Married or partner | 0.77 | 0.47 | 0.77 | 0.46 |

| Health behaviours | ||||

| Current smoker | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.10 |

| Ever smoked | 0.68 | 0.21 | 0.69 | 0.41 |

| Not physically active | 0.60 | 0.77 | 0.63 | 0.71 |

| Diet | ||||

| High saturated fat diet (>40 g/day) | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.04 |

| High carbohydrate diet (>400 g/day) | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.02 |

| High calorie diet (>3000 kcal/day) | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.02 |

| Anthropometric | ||||

| Obese (BMI ≥30) | 0.23 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.40 |

| Severely obese (BMI ≥40) | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.14 |

| Waist (>102 cm men, >88 cm women) | 0.25 | 0.67 | 0.59 | 0.75 |

| Prevalent health conditions | ||||

| Hypertension (systolic/diastolic >140/90) | 0.55 | 0.60 | 0.35 | 0.50 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia (TC:HDL>=5.92) | 0.33 | 0.26 | 0.49 | 0.45 |

| Diabetes (HbA1c>6.5%) | 0.18 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.15 |

Among health behaviours related to cardiovascular disease mortality, Costa Rica has a lower percentage of current smokers among women. The USA has a much higher percentage of women who had ever smoked. Men and women in the USA were more likely to be obese, to be severely obese and to have a larger waist circumference, with higher proportions of each among women than among men in both countries. In the USA, there were lower levels of hypertension, higher levels of hypercholesterolaemia and lower levels of diabetes (among women).

Figure 1 shows a comparison (NHANES—solid lines; CRELES—dashed lines) of the population distribution of eight biological risk markers for CVD. All median differences shown are statistically significantly different at the α=0.05 level except for LDL cholesterol. Costa Ricans show substantially higher triglycerides and systolic blood pressure and substantially lower BMI. The overall distribution of these biological risk factors are generally similar between NHANES and CRELES, with the exception of an upwardly shifted distribution of systolic blood pressure in CRELES, and a higher right-hand tail of BMI distribution in the USA.

Figure 1.

Distribution of cardiovascular disease biomarkers in Costa Rica (Costa Rican Longevity and Healthy Ageing Study, dashed lines) and the USA (NHANES, solid lines), men and women, aged >60. A vertical solid line indicates the median value in the USA; a dashed vertical line indicates the median value in Costa Rica.

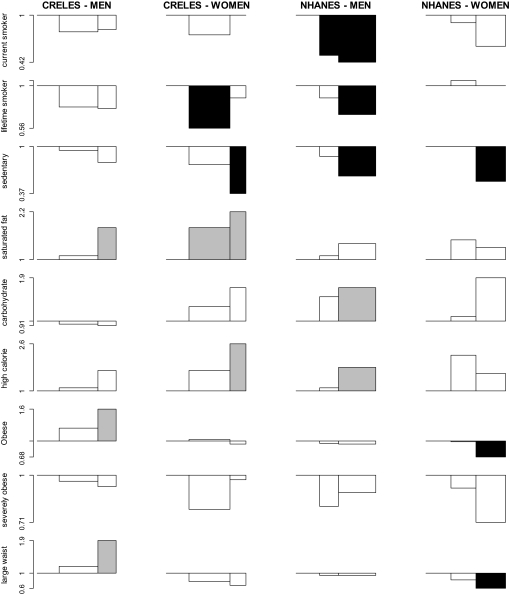

Figure 2 presents ORs of smoking, physical activity, diet and anthropometric measures by educational attainment, controlling for age, age-squared and stratified by gender. The ORs can be interpreted as the ratio of the odds of the outcome in either the middle or highest education category as compared with the lowest education category. In Costa Rica, there was a higher proportion of individuals with a high saturated-fat diet among the most educated. Among Costa Rican men, the most educated were more likely to be obese and more likely to have a large waist circumference. Among women, there was a lower probability of lifetime smoking and being sedentary among the more educated and a higher probability of having a high calorie diet. In the USA, more educated individuals were significantly less likely to be sedentary. Among men in the USA, more educated were less likely to be current smokers, less likely to be lifetime smokers but more likely to have a high-carbohydrate and high-calorie diet. Among women, more educated women were less likely to be obese and have a large waist circumference.

Figure 2.

ORs of anthropometric and health behavioural cardiovascular disease risk factors by education in Costa Rica (Costa Rican Longevity and Healthy Ageing Study (CRELES)) and the USA (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)), men and women, aged >=60. ORs are from logistic regression models comparing the middle and highest categories of education with the lowest category, controlling for age and age-squared. Bar widths are proportional to the relative size of the population in each category of education. Statistically significant ORs (p<0.05) are shaded (black if level is associated with lower risk of CVD, grey if level is associated with a higher risk of CVD).

Figure 3 shows differences in levels of eight biological risk factors for CVD by educational attainment, controlling for age, age-squared and stratified by gender. The plotted betas from linear regression models can be interpreted as absolute differences in the level of the biomarker among those in the middle or highest educational categories as compared with the lowest education category. In Costa Rica, higher educational attainment is associated with lower levels of LDL among men, and lower levels of hemoglobin A1c and systolic blood pressure in women. Among men in the USA, there are higher levels of triglycerides among men in the middle education category and lower levels of hemoglobin A1c. Among women in the USA, among the more educated there were higher (lower risk) levels of HDL cholesterol, lower levels of hemoglobin A1c, lower levels of fasting glucose, lower levels of C-reactive protein and lower levels of BMI.

Figure 3.

Differences in levels of cardiovascular disease biomarkers by education in Costa Rica (Costa Rican Longevity and Healthy Ageing Study (CRELES)) and the USA (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)), men and women, age>=60. Education differences plotted are beta estimates from regression models comparing the middle and highest categories of education with the lowest category, controlling for age and age-squared. Bar widths are proportional to the relative size of the population in each category of education. Statistically significant ORs (p<0.05) are shaded (black if level is associated with lower risk of CVD, grey if level is associated with a higher risk of CVD).

Thus, overall, there were significantly fewer hazardous levels of risk biomarkers at higher levels of education for more than half (10 out of 17) of the risk factor outcomes in the USA. This was true for less than a third of the outcomes in Costa Rica (five out of 17). In Costa Rica, higher levels of education were associated with higher risk levels for approximately one-quarter (four out of 17) of the risk factor outcomes, while this was the case for three out of 17 risk factors in the USA.

Discussion

We found that there was not a uniform lack of education differentials of risk factors in Costa Rica nor a universal presence of education differentials in risk factors in the USA. Instead, we found education differentials in the USA driven by lower levels of current smoking, lifetime smoking, sedentary behaviour and hemoglobin A1c among more educated men and lower levels of sedentary behaviour, obesity, large waist circumference, hemoglobin A1c, fasting glucose, C-reactive protein, BMI and higher HDL cholesterol among more educated women. In Costa Rica, some important risk factors (eg, smoking, higher systolic blood pressure and sedentary) are more prevalent among the less educated, but other important risk factors such as obesity (among men) or overall high calorie and saturated fat diets (among women) are more prevalent among those with less education. This combination of risk factors may on balance act to create the observed education–mortality differences between these two countries. The differential importance of education depended on country context. Among the 17 gender-stratified outcomes examined, the only similarly statistically significant education differentials we observed were for sedentary behaviour and hemoglobin A1c among women. These observations are not consistent with universal effects associated with educational attainment. In addition, at least in each of these two countries, there is little evidence for universal associations between education and risk factors for CVD.

There are several limitations to this descriptive study. Multiple risk factors may interact,24 and the clustering of risk factors may be different in each country. While there may be other biological pathways with different education associations that we do not examine, known risk factors explain the majority of absolute levels of CVD as well as socio-economic differences.21 22 42 43 It is unlikely that racial/ethnic minorities in the USA are the reason for the differences in the association of education with risk factors, as we repeated our analysis using only the non-Hispanic white population of the USA, and results did not change substantively (data not shown). We also repeated our analysis with alternative educational categories in Costa Rica, which did not meaningfully change our overall findings (shown in supplemental data, tables S1 and S2). The time periods of these data differ slightly (1999–2004 in the USA and 2004–2006 in Costa Rica), but evidence suggests that socio-economic differences are not changing rapidly enough for this to influence our comparison.44 Data from Costa Rica were available only for individuals age 60 and above, so inference should not be made outside this age range. Results depend on our measure of socio-economic position, with education more likely to capture early life exposures.45 46 Finally, measures of sedentary behaviour and dietary intake differed between surveys, so these comparisons should be interpreted with some caution.

Some prior work has also sought to understand international differences in risk factors underlying CVD.2 47 In contrast with our results, education differences in CVD risk factors in a younger population (age 40–70) in the USA and England qualitatively reveal similar education differences for dichotomised measures of HbA1c, blood pressure, C-reactive protein, fibrinogen and HDL cholesterol, current smoking, ever smoking and obesity.47 More similar to our findings, a study of 11 European Union countries found substantial educational differences in overweight among men (ORs ranging from 0.87 to 2.00 for low education vs all other categories) and current smoking among women (ORs ranging from 0.32 to 1.94 for low education vs all other categories).48

Prior examinations of socio-economic differences in CVD risk factors have also found similar gender differences49 50 that may be due to gender (a social construct relating to culturally influenced differences between men and women) or sex-linked biology.51 These gender differences are consistent with a context-specific importance of education by gender. For example, we found different associations between education and obesity by gender (a significant positive association among men in Costa Rica, and a significant negative association among women in the USA) that are unlikely to be explained solely by sex-linked biology.

The motivating question was to determine whether risk factor and education associations were absent in Costa Rica and present and consistent across examined factors in the USA, or whether there was a balance of different types of risk factor associations with education that lead to the observed mortality–education associations. Our findings are consistent with the latter. This is less consistent with any one factor having a majority influence on educational differences in mortality. Nevertheless, a number of theories may still be relevant, but based on our findings, the effects may be specific to particular pathways. While this complexity may be daunting for efforts to reduce education disparities in mortality, a lack of universal associations with education also implies potentially more tractable approaches of focussing prevention and treatment on the specific risk factors most responsible for differences in disparities.

What is already known on this subject.

In most developed countries (eg, the USA), there are currently higher rates of cardiovascular disease among individuals with lower levels of education. Costa Rica is a remarkable exception to this, with no differences in cardiovascular disease by level of education among individuals over the age of 60. It is unknown whether this socio-economic equity in cardiovascular mortality results from universal equity in the distribution of risk factors for cardiovascular disease, or from a balance of different education associations with risk factors.

What this study adds.

This study shows that there is not a uniform lack of education associations with cardiovascular risk factors in Costa Rica, nor a uniform presence of education associations with cardiovascular risk factors in the USA. Instead, a balance of different education–risk factor associations are found that are consistent with the observed differences in the cardiovascular mortality and education associations found in each country. This demonstrates that social equity in cardiovascular mortality is achieved without uniform equity of risk factors.

Acknowledgments

Principal investigator: L Rosero-Bixby. Coprincipal investigators: X Fernández and WH Dow. Collaborating investigators: E Méndez, G Pinto, H Campos, K Barrantes, F Fallas, G Brenes and F Morales. Informatics and support staff: D Antich, A Ramírez, J Hidalgo, J Araya and Y Hernández. Field workers: J Solano, J Palma, J Méndez, M Aráuz, M Gómez, M Rodríguez, G Salas, J Vindas and R Patiño.

Footnotes

Funding: The CRELES project (Costa Rican Longevity and Healthy Ageing Study) is a longitudinal study of the Universidad de Costa Rica, carried out by the Centro Centroamericano de Población in collaboration with the Instituto de Investigaciones en Salud, with the support of the Wellcome Trust Foundation (grant no 072406).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was provided by the Universidad de Costa Rica and University of California, Berkeley.

Contributors: DHR and WHD conceived of the study; DHR performed the analysis and led the writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data and revision of the article text. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Backlund E, Sorlie PD, Johnson NJ. A comparison of the relationships of education and income with mortality: the national longitudinal mortality study. Soc Sci Med 1999;49:1373–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mackenbach JP, Kunst AE, Cavelaars AE, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in morbidity and mortality in western Europe. The EU Working Group on Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health. Lancet 1997;349:1655–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Son M, Armstrong B, Choi JM, et al. Relation of occupational class and education with mortality in Korea. J Epidemiol Community Health 2002;56:798–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kunitz S. Sex, race and social role—history and the social determinants of health. Int J Epidemiol 2007;36:3–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dow WH, Gonzalez K, Rosero-Bixby L. Aggregation and insurance-mortality estimation. NBER Working Paper 2003;9827 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosero-Bixby L, Dow WH, Lacle A. Insurance and other socioeconomic determinants of elderly longevity in a Costa Rican panel. J Biosoc Sci 2005;37:705–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elo IT, Preston SH. Educational differentials in mortality: United States, 1979–85. Soc Sci Med 1996;42:47–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steenland K, Henley J, Thun M. All-cause and cause-specific death rates by educational status for two million people in two American Cancer Society cohorts, 1959–1996. Am J Epidemiol 2002;156:11–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosero-Bixby L. Evaluacion del impacto de la reforma del sector salud en Costa Rica. Revista Panamericana de salud Publica 2004;15:94–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Link BG, Northridge ME, Phelan JC, et al. Social epidemiology and the fundamental cause concept: on the structuring of effective cancer screens by socioeconomic status. Milbank Q 1998;76:375–402, 304–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav 1995;35:80–94 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cutler DM, Deaton A, Lleras-Muney A. The determinants of mortality. NBER Working Paper 2006;11963 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cutler DM, McClellan M. Is technological change in medicine worth it? Health affairs. 2001;20:11–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuchs VR. Time preference and health: an exploratory study. NBER Working Paper 1982;539 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuchs VR. Reflections on the socio-economic correlates of health. J Health Econ 2004;23:653–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marmot M. The status syndrome: how social standing affects our health and longevity. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilkinson RG. The impact of inequality: how to make sick societies healthier. New York: The New Press; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong MD, Shapiro MF, Boscardin J, et al. Contributions of major diseases to disparities in mortality. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1585–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ministerio de Salud. La salud de las personas adultas mayores de Costa Rica. San Jose, Costa Rica: OPS, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawlor DA, Smith GD, Leon DA, et al. Secular trends in mortality by stroke subtype in the 20th century: a retrospective analysis. Lancet 2002;360:1818–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beaglehole R, Magnus P. The search for new risk factors for coronary heart disease: occupational therapy for epidemiologists? Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:1117–22; author reply 34–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Magnus P, Beaglehole R. The real contribution of the major risk factors to the coronary epidemics: time to end the ‘only-50%’ myth. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:2657–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Heart Association Statement AHA dietary guidelines: revision 2000: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Nutrition Committee of the American Heart Association. Circulation 2000;102:2284–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grundy SM, Pasternak R, Greenland P, et al. AHA/ACC scientific statement: Assessment of cardiovascular risk by use of multiple-risk-factor assessment equations: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;34:1348–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grundy SM, Pasternak R, Greenland P, et al. Assessment of cardiovascular risk by use of multiple-risk-factor assessment equations: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology. Circulation. 1999100:1481–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mackay J, Mensah G. Atlas of heart disease and stroke. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2004. Contract No: Document Number. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Expert Panel on Detection Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adults Treatment Panel III) Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP). JAMA 2001;285:2486–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case–control study. Lancet 2004;364:937–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davey Smith G, Hart C, Blane D, et al. Adverse socioeconomic conditions in childhood and cause specific adult mortality: prospective observational study. BMJ 1998;316:1631–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lawlor DA, Davey Smith G. Early life determinants of adult blood pressure. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2005;14:259–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawlor DA, Taylor M, Davey Smith G, et al. Associations of components of adult height with coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women: the British women's heart and health study. Heart 2004;90:745–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lynch J, Davey Smith G. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology. Annu Rev Public Health 2005;26:1–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brunner E, Shipley MJ, Blane D, et al. When does cardiovascular risk start? Past and present socioeconomic circumstances and risk factors in adulthood. J Epidemiol Community Health 1999;53:757–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kromhout D, Menotti A, Kesteloot H, et al. Prevention of coronary heart disease by diet and lifestyle: evidence from prospective cross-cultural, cohort, and intervention studies. Circulation 2002;105:893–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosero-Bixby L, Dow WH. Surprising SES Gradients in mortality, health, and biomarkers in a Latin American population of adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2009;64:105–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.CDC Analytic and Reporting Guidelines, The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. Hyattsville: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2005. [updated 2005; cited 2007 October 28]; http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_03_04/nhanes_analytic_guidelines_dec_2005.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kabagambe EK, Baylin A, Allan DA, et al. Application of the method of triads to evaluate the performance of food frequency questionnaires and biomarkers as indicators of long-term dietary intake. Am J Epidemiol 2001;154:1126–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.El-Sohemy A, Baylin A, Ascherio A, et al. Population-based study of alpha- and gamma-tocopherol in plasma and adipose tissue as biomarkers of intake in Costa Rican adults. Am J Clin Nutr 2001;74:356–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.NCHS The NHANES 1999-2001 dietary interviews procedure manual. Hyattsville: National Center for Health Statistics, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mendez-Chacon E, Santamaria-Ulloa C, Rosero-Bixby L. Factors associated with hypertension prevalence, unawareness and treatment among Costa Rican elderly. BMC Public Health 2008;8:1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.CDC National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2004. Documentation, codebook and frequencies, MEC Exam Component: blood pressure examination data. Hyattsville: Department of Health and Human Services, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lynch J, Davey Smith G, Harper S, et al. Explaining the social gradient in coronary heart disease: comparing relative and absolute risk approaches. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:436–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khang YH, Lynch JW, Jung-Choi K, et al. Explaining age-specific inequalities in mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease and ischaemic heart disease among South Korean male public servants: relative and absolute perspectives. Heart 2008;94:75–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krieger N, Rehkopf DH, Chen JT, et al. The fall and rise of US inequities in premature mortality: 1960–2002. PLoS Med 2008;5:e46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Galobardes B, Morabia A, Bernstein MS. Diet and socioeconomic position: does the use of different indicators matter? Int J Epidemiol 2001;30:334–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Galobardes B, Lynch JW, Davey Smith G. Childhood socioeconomic circumstances and cause-specific mortality in adulthood: systematic review and interpretation. Epidemiol Rev 2004;26:7–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Banks J, Marmot M, Oldfield Z, et al. Disease and disadvantage in the United States and in England. JAMA 2006;295:2037–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cavelaars AE, Kunst AE, Mackenbach JP. Socio-economic differences in risk factors for morbidity and mortality in the European community. J Health Psychol 1997;2:353–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Loucks EB, Rehkopf DH, Thurston RC, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in metabolic syndrome differ by gender: evidence from NHANES III. Ann Epidemiol 2007;17:19–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schooling CM, Jiang CQ, Lam TH, et al. Life-course origins of social inequalities in metabolic risk in the population of a developing country. Am J Epidemiol 2008;167:419–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krieger N. Genders, sexes, and health: what are the connections—and why does it matter? Int J Epidemiol 2003;32:652–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]