Abstract

The biological threat imposed by orthopoxviruses warrants the development of safe and effective vaccines. We developed a candidate orthopoxvirus DNA-based vaccine, termed 4pox, which targets four viral structural components, A33, B5, A27, and L1. While this vaccine protects mice and nonhuman primates from lethal infections, we are interested in further enhancing its potency. One approach to enhance potency is to include additional orthopoxvirus immunogens. Here, we investigated whether vaccination with the vaccinia virus (VACV) interferon (IFN)-binding molecule (IBM) could protect BALB/c mice against lethal VACV challenge. We found that vaccination with this molecule failed to significantly protect mice from VACV when delivered alone. IBM modestly augmented protection when delivered together with the 4pox vaccine. All animals receiving the 4pox vaccine plus IBM lived, whereas only 70% of those receiving a single dose of 4pox vaccine survived. Mapping studies using truncated mutants revealed that vaccine-generated antibodies spanned the immunoglobulin superfamily domains 1 and 2 and, to a lesser extent, 3 of the IBM. These antibodies inhibited IBM cell binding and IFN neutralization activity, indicating that they were functionally active. This study shows that DNA vaccination with the VACV IBM results in a robust immune response but that this response does not significantly enhance protection in a high-dose challenge model.

The potential for variola virus (VARV, causing smallpox), or a genetically modified orthopoxvirus pathogenic to humans, to be accidentally or maliciously released into the environment has prompted a renewed interest in the development of orthopoxvirus countermeasures. A live-virus vaccine against orthopoxviruses is available and indeed was used to eradicate smallpox in the 20th century. However, this vaccine is associated with moderate to severe side effects, including myocarditis, eczema vaccinatum, and death (4, 21). As such, this vaccine is contraindicated for large portions of the population. Because the vaccine is also capable of spreading virus to nonvaccinated persons, those living with persons who are contraindicated for the vaccine are advised not to get vaccinated. Accordingly, safer alternative vaccines are being sought. These include highly attenuated live-virus vaccines, such as MVA and Lc16m8 (13, 23), and molecular vaccines. Molecular approaches include protein- and DNA-based subunit vaccines targeting various protective immunogens (9, 10, 14, 16, 17, 29, 34). Ideally, these vaccines will provide cross-protective immunity against all members of the orthopoxvirus family, including genetically modified strains. Subunit vaccines targeting structural molecules (A33, B5, L1, A27, H3, and D8) located on the two infectious forms of orthopoxvirus particles, the mature virion (MV) and the enveloped virion (EV), have shown protective efficacy in independent laboratories (6, 8-10, 14, 16, 17, 29, 34). Combinations of the MV and EV immunogens have been shown to elicit more complete protection than that elicited by vaccination with EV or MV targets alone (9, 15, 16). We have focused on a gene-based molecular vaccine, termed 4pox, targeting the EV immunogens A33 and B5 plus the MV targets L1 and A27 (11, 12, 15-17). This vaccine protects mice and nonhuman primates from lethal vaccinia virus (VACV) or monkeypox virus (MPXV) challenges, respectively (16, 17, 19). Recent studies have revealed that complete protection from lethality can be established after a single boost (12, 17).

Orthopoxviruses express a multitude of immune evasion strategies, including soluble decoy receptors, complement-inactivating molecules, and intracellular inhibitors of interferon (IFN) (for reviews, see references 26 and 31). The VACV interferon-binding molecule (IBM) (B19R/B18R) is a type I interferon-binding decoy receptor expressed by VACV (5, 32). The molecule is secreted from infected cells, whereupon it aids in virus replication within the infected host by inhibiting the antiviral activity of type I IFNs by direct binding (2, 32). There are three immunoglobulin superfamily (IgSF) domains within the protein; however, the function of these domains and their role in either cell binding or type I IFN neutralization are unclear. Deletion of IBM results in ∼100-fold attenuation of VACV in vivo (32). Xu et al. recently reported that the ectromelia virus (ECTV) molecule EVM166, the IBM ortholog, is critical for virus replication in vivo (35). Deletion of EVM166 results in a 107-fold decrease in infectivity in vivo. Furthermore, protein vaccination with the EVM166 molecule plus adjuvant afforded complete protection against ECTV (35). This finding demonstrates that a viral nonstructural molecule can function as an efficacious vaccine target. Thus, targeting viral immune response modifiers (IRMs) that alter the immune response in favor of viral replication may represent a hitherto-untapped group of vaccine targets (35). Whereas EVM166 is capable of protecting mice from ECTV, the ability of IBM, the VACV EVM166 ortholog, to function as a vaccine target has not been established.

Vaccination with live virus confers significant protection after a single dose. However, vaccination with subunit vaccines targeting orthopoxvirus structural molecules consistently requires two or more vaccinations. Live-virus vaccines contain many vaccine targets, both structural targets and IRMs. Accordingly, it is possible that targeting IRMs, in addition to the structural proteins, confers superior protection compared to solely targeting structural molecules. The study by Xu et al. clearly demonstrates that viral IRMs are potent targets in at least some orthopoxvirus models (35). Therefore, we hypothesized that it might be possible to increase the efficacy of our structural-gene-based vaccine by including a nonstructural target previously shown to play a role in pathogenesis. Here, we investigated the protective efficacy of a DNA vaccine targeting the VACV IBM molecule alone and combined with the 4pox structural immunogens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

The VACV Connaught vaccine strain (derived from the New York City Board of Health strain) and VACV strain IHD-J (obtained from Alan Schmaljohn) were both maintained in Vero cell (ATCC CRL-1587) monolayers grown in Eagle minimal essential medium (EMEM), containing 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone, Logan, UT), 1% antibiotics (100 U/ml of penicillin, 100 μg/ml of streptomycin, and 50 μg/ml of gentamicin), and 10 mM HEPES (cEMEM). COS-7 (COS) cells (ATCC CRL-1651) were used for transient expression experiments and were also maintained in EMEM. The IFN signaling reporter cell line 293:IFN contains a red fluorescent protein (RFP) under the control of a human type I IFN-inducible promoter (27) and was kindly provided by Bret Beitzel. 293:IFN cells were maintained as monolayers in cEMEM.

DNA vaccination with gene gun.

The DNA vaccination procedure was described previously (15, 30). Briefly, plasmid DNA 4pox vaccine targets (pWRG/tPA-L1Ropt, pWRG/A33Rkopt, pWRG/A27kopt, and pWRG/B5Rkopt), IBM molecule (pWRG/IBM), or pWRG/HTN-M(x) (negative-control DNA) was precipitated onto ∼2-μm-diameter gold beads at a concentration of 1 μg of DNA/mg of gold. DNA-gold mixtures were applied as a coating to the inner surface of irradiated Tefzel tubing, and the tubing was cut into 0.5-in. cartridges. Each cartridge contained ∼0.25 to 0.5 μg of DNA applied as a coating to 0.5 mg of gold. All cartridges were quality controlled to ensure the presence of DNA. The 4pox plasmids were present on the same gold particles at a ratio of 1:1:1:1. For vaccinations, the abdominal fur of BALB/c mice was shaved and DNA-coated gold was administered using a gene gun (Powdermed delivery device; Powdermed, Inc., Oxford, England) and compressed helium gas at 400 lb/in2. Mice were vaccinated either once or twice at 3-week intervals as indicated. All mice were at least 7 to 9 weeks old at the start of vaccination.

Scarification.

Scarification was performed by placing a 10-μl drop of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 8 × 106 PFU of VACV (Connaught) near the base of the tail on each mouse. The tail was then scratched ∼15 to 20 times by using a needle on a tuberculin syringe.

Mouse viral challenge studies.

Mice were anesthetized and weighed before intranasal (i.n.) administration with a plastic pipette tip containing 50 μl of PBS with 2 × 106 PFU of VACV strain IHD-J. Approximately 25 μl was instilled per nare. This dose represents at least three times the 50% lethal dose (LD50). Mice were observed and weighed daily for 21 days postinfection. Moribund mice (with >30% body weight decrease) were euthanized.

Flow cytometry.

COS cell monolayers (70 to 80% confluent) were transiently transfected in T25 flasks with indicated constructs using Fugene 6. Transfected cells were incubated at 37°C for 48 h, trypsinized, and washed once with EMEM. After the wash, ∼1 × 106 cells were transferred to 1.5-ml tubes. In some cases, cells were fixed (30 min) using fixation buffer (BD Biosciences) and then permeabilized in wash/permeabilization buffer (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's directions. Cells were incubated with serum from vaccinated animals (1:100) for 1 h at room temperature in fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer (PBS, 5% FBS, and 0.1% sodium azide) or wash/permeabilization buffer. After incubation with the primary antibody, cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 750 × g for 3 min and washed twice with FACS buffer or wash/permeabilization buffer. Cells were next incubated with anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) (1:500) for 30 min at room temperature. After incubation with the secondary antibody, cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 750 × g for 3 min. Washed cells were resuspended in 1 ml of FACS buffer. Flow cytometry was performed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Data were collected and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR). A total of 10,000 cells were analyzed for each sample.

Cloning.

The open reading frame encoding the VACV IBM was synthesized de novo (Gene Art, Burlingame, CA) using the Copenhagen amino acid sequence. This construct was cloned into the pWRG7077 DNA vaccine vector at the NotI and BglII sites. This vector includes the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter, an intron A element, and a polyadenylation signal (30).

Three N-terminal truncation mutants that removed each domain in succession were generated. N-terminal mutant 7 (N7) contained IgSF domains 1 and 2, represented nucleotides 1 to 756, and was generated using the forward primer 5′-GGGGGCGGCCGCATGACCATGAAGATGATGGTGCACATC-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-GGGGAGATCTTCAGTTGATCTTGGGGTCCAGGATCAGCTTGAACCG-3′. N-terminal mutant 4 (N4) contained IgSF domain 1, represented nucleotides 1 to 486, and was created using forward primer 5′-GGGGGCGGCCGCATGACCATGAAGATGATGGTGCACATC-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GGGGAGATCTTCAGGTGCCCAGCTCGTAGGTCTT-3′. The forward primers generated a NotI site (underlined), and the reverse primers created a BglII site and also included a stop codon. PCR products were cloned into the NotI and BglII sites of pWRG7077.

C-terminal truncation mutants that contained either IgSF domains 2 and 3 or domain 3 alone were generated. C-terminal mutant 7 (C7) represented nucleotides 1 to 157 and 448 to 1053 and was generated using the reversed forward primer 5′-GGCGGGGTTCAGCCACTTGCT-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-CCCCCCAGCTGCATCCCCAAG-3′ in the forward direction. C-terminal mutant 4 (C4) represented nucleotides 1 to 157 and 736 to 1053 and was created using the same reversed forward primer and a reverse primer in the forward direction, 5′-CCCAGCCAGGACCACCGGTTC-3′. Nucleotides 1 to 157 are the predicted secretion signal sequence and thus were retained to ensure that the molecule was secreted upon expression. PCR was performed through the pWRG/IBM plasmid. The PCR product was diluted to 1 ng/μl and incubated with 10 μl T4 ligase buffer, 0.5 μl T4 ligase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), 0.5 μl polynucleic acid kinase, and water in a total volume of 100 μl overnight at room temperature to religate. The plasmid was then used to transform bacteria.

Cell-binding assay.

The ability of the full-length IBM and deletion mutants to bind eukaryotic cells was investigated using a novel flow-based binding assay. Plasmids encoding each molecule of interest were transfected into COS-7 cells using Fugene 6. Forty-eight hours posttransfection, media from cell cultures were collected and clarified by low-speed centrifugation. Clarified medium was added to new COS-7 cell monolayers and incubated for 2 h with rocking every 15 min at room temperature. After incubation, cells were washed twice with PBS, trypsinized, and placed in FACS tubes (5 × 105 cells/tube) in FACS buffer (PBS plus 5% fetal bovine serum). Cells were then stained with anti-IBM antibodies (1:100) for 1 h, washed in FACS buffer, and incubated with an anti-mouse secondary antibody conjugated with an Alexa Fluor 488 fluorochrome (1:500) for 30 min. Samples were then washed three times in FACS buffer and analyzed on a flow cytometer. We have observed that the IBM protein is present on the cell surface for several hours postbinding but is undetectable after 24 h (data not shown).

To determine if anti-IBM serum antibodies disrupted IBM binding, media from COS cells transfected with IBM were not incubated or were incubated with anti-IBM serum antibodies (1:50) for 2 h at 37°C. Medium was then incubated with fresh COS cell monolayers for 2 h at room temperature and washed three times with PBS. Cells incubated without antibodies were then incubated with anti-IBM antibodies (1:50) for 2 h and washed three times with PBS. All cells were then incubated with an anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody (1:500) for 1 h at room temperature. Samples were then examined using flow cytometry.

IFN reporter cell line.

The ability of the IBM and N- and C-terminal mutants to neutralize type I IFNs was investigated. Plasmids encoding each molecule were transfected into COS cells by using Fugene 6. Forty-eight hours posttransfection, media from cell cultures were collected and clarified by low-speed centrifugation. Clarified media containing the IBM were incubated with the type I IFN signaling cell line 293:IFN, which contains a red fluorescent protein under the control of a type I-inducible promoter. Cell monolayers were incubated for 2 h with rocking every 15 min at room temperature. After incubation, cells were washed twice with PBS and medium containing type I alpha IFN (IFN-α) (500 U/ml) was added back to the wells. Cells were incubated overnight (24 h) at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. For the mutant experiment, N- and C-terminal mutants and the IBM construct were incubated with type I IFN for 2 h prior to being incubated with the 293:IFN cell line. After 24 h, cells were removed from plates by gentle agitation and washed in FACS buffer, followed by low-speed centrifugation. Cells were then resuspended in PBS (1 × 106 cells/ml) and analyzed on a flow cytometer for RFP expression.

For the IBM inhibition functional assay, 293 cells were incubated with or without IBM-containing medium (derived from transfected COS cells) as described above. Cells were then washed and incubated with or without serum antibodies (1:20) as indicated for an additional 2 h and then washed with PBS. Cells were then processed as indicated above.

RESULTS

The vaccinia virus IBM is immunogenic when delivered as a DNA vaccine antigen.

The IBM gene (derived from the Copenhagen strain) optimized both for codon usage in mammalian cells and for mRNA stability was synthesized de novo and cloned into the DNA vaccine pWRG7077 vector. This produced the vaccine construct pWRG/IBM. A primary function of the IBM is to neutralize type I IFNs (2, 32). Therefore, prior to vaccine studies the authenticity of the IBM gene product was confirmed using 293:IFN cells. When these cells are treated with IFN-α, RFP is produced. COS cells were transfected with pWRG/IBM, and 48 h posttransfection, medium containing IBM was removed and tested using the IFN reporter cell line. In samples receiving medium from untransfected cells, IFN-α induced expression of RFP, indicating that the reporter system was functional (Fig. 1A). Consistent with the ability of IBM to bind and neutralize IFNs, cells incubated with the medium from the pWRG/IBM-transfected cells did not exhibit RFP expression. In contrast, other experiments demonstrated that transfection of COS cells with truncated versions of IBM failed to neutralize RFP expression (see below). The finding that medium from pWRG/IBM-transfected cells inhibited RFP expression was reproducible (data not shown). Thus, the optimized IBM molecule produced by pWRG/IBM was functionally active and capable of interfering with IFN-α.

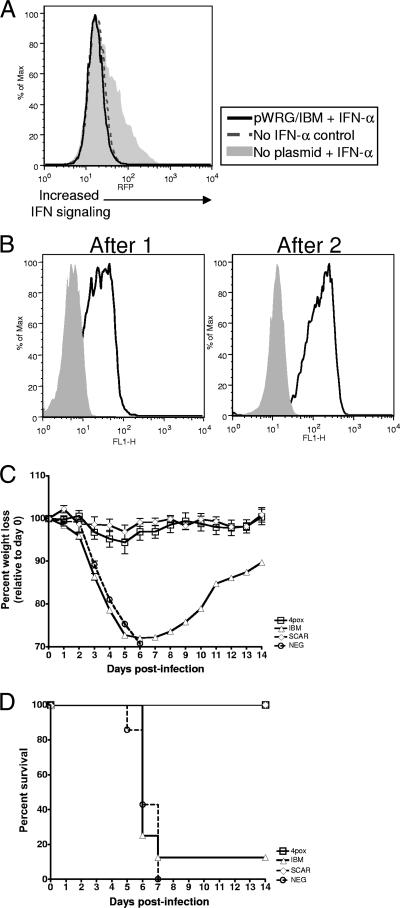

FIG. 1.

Analysis of the VACV IBM molecule as a protective immunogen. (A) IBM expressed from pWRG/IBM-transfected cells can inhibit IFN-α activity. 293:IFN cells were incubated with medium from COS cells or COS cells transfected with pWRG/IBM. After incubation, fresh medium containing 500 U/ml human IFN-α was added to each monolayer. Twenty-four hours after IFN treatment, expression of RFP was monitored by flow cytometry. As a negative control, a group of 293:IFN cells was not incubated with IFN. (B) The anti-IBM response in vaccinated mice was monitored by flow cytometry. COS cells were not transfected (solid gray area) or were transfected with pWRG/IBM (black line) and, 48 h later, fixed and permeabilized. Sera (1:100) from animals vaccinated once or twice with pWRG/IBM were incubated with COS cells. Cells were then washed and stained with an anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:500). After 1 h of incubation, cells were washed and fluorescence was analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) Mice were vaccinated twice at 3-week intervals with the indicated molecules. Three weeks following the last vaccination, mice vaccinated with pWRG/IBM or the 4pox vaccine were challenged i.n. with VACV strain IHD-J. Mice vaccinated with live virus (SCAR) or with negative-control DNA (NEG) were included in the challenge. Mean percent weight loss relative to starting group weight for survivors was plotted with standard deviations. (D) Survival curves were plotted for each challenge group in panel C.

IBM alone does not significantly protect against VACV challenge.

Our ultimate goal was to determine if the IBM would enhance the efficacy of our 4pox vaccine. Nevertheless, to more completely understand any protection gained by vaccination with this molecule, we first investigated its capacity to protect mice from lethal challenge when administered alone. Groups of eight female BALB/c mice were vaccinated by gene gun with pWRG/IBM or an optimized 4pox DNA vaccine twice. As positive and negative controls, respectively, groups of mice were vaccinated once by scarification with live VACV or twice with negative-control DNA. We previously found that vaccination with all four 4pox genes combined on the same gold beads (i.e., expression in the same cells) leads to protective antibody responses against each target. Additionally, we discovered that optimization of the genes for codon usage and mRNA stability modestly enhances protective efficacy over that of unmodified genes (J. Golden and J. W. Hooper, unpublished observations). Pooled sera from mice vaccinated once or twice contained detectable anti-IBM antibody after the first vaccination, and the levels increased after the second vaccination, as measured by flow cytometry using IBM-expressing COS cells (Fig. 1B). Sera from individual mice were also screened after the boost. All mice had similar levels of anti-IBM antibody (data not shown). Thus, DNA vaccination with IBM leads to the production of anti-IBM antibodies in mice. Mice vaccinated with the 4pox vaccine did not have an anti-IBM response but did produce antibodies against all four of the 4pox target immunogens as measured by immunogen-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (data not shown). The virus used for all murine challenges below was VACV strain IHD-J. Therefore, prior to challenge studies we verified by flow cytometry that anti-IBM serum antibodies interacted with IBM expressed in IHD-J-infected cells (data not shown).

Five weeks after the last vaccination, mice were challenged intranasally (i.n.) with VACV strain IHD-J. Figures 1C and D show the weight loss and survival data, respectively. The optimized 4pox-vaccinated mice did not lose a significant amount of weight compared to the live-virus-vaccinated animals, and all animals survived challenge. All mice vaccinated with the negative-control DNA lost weight starting on day 3 and succumbed or were euthanized (>30% weight loss) by day 7. Mice vaccinated with pWRG/IBM lost considerable weight beginning on day 3, and this weight loss continued until day 8. A single IBM-vaccinated mouse survived challenge. This animal regained weight rapidly and, by day 14, was 10% below the starting weight. These findings indicated that IBM alone is not a highly effective gene-based vaccine target in the VACV intranasal challenge model.

IBM decreases mortality but not morbidity when combined with structural vaccine targets.

Preliminary data generated by our laboratory have indicated that the optimized 4pox vaccine protects 100% of animals with little or no weight loss after two vaccinations (Fig. 1B and C) (Golden and Hooper, unpublished). After a single dose of the optimized 4pox vaccine, 60 to 70% of mice survive challenge with 15 to 25% weight loss (Fig. 2B and C) (Golden and Hooper, unpublished). We hypothesized that a vaccine including IBM combined with the 4pox structural molecules would yield superior protection after a single dose compared to the 4pox vaccine alone. Groups of eight BALB/c mice were vaccinated once with 4pox or 4pox plus IBM. In the latter case, pWRG/IBM DNA was on separate cartridges. Sera from mice were collected 3 weeks following the single vaccination and evaluated for antibody responses. Vaccinated mice developed relatively similar antibody responses against each target, as evidenced by flow cytometry using cells expressing the indicated target molecules (Fig. 2A). In addition to developing antibodies against VACV structural targets, the group vaccinated with 4pox plus IBM developed anti-IBM responses, whereas those excluding IBM did not (Fig. 2A). Together these results show that detectable antibody responses can be generated against the 4pox vaccine targets and IBM after a single DNA vaccination.

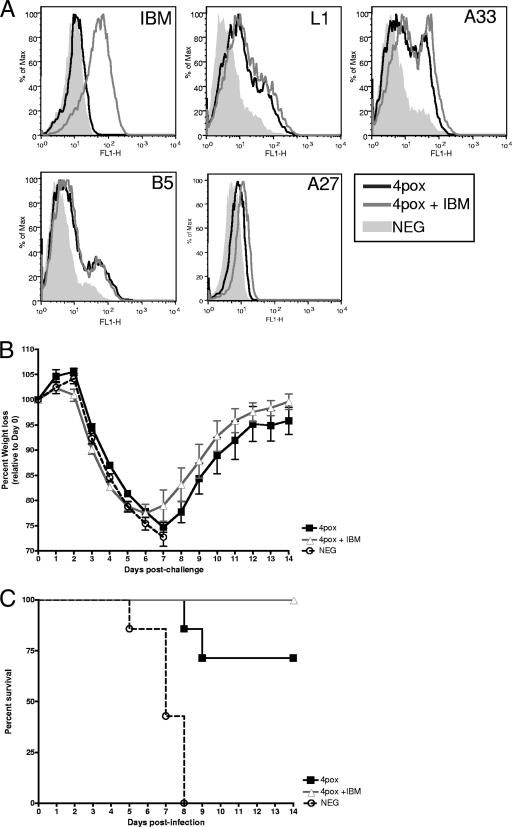

FIG. 2.

Vaccination with IBM in combination with structural vaccine targets. (A) IBM, L1, A33, B5, and A27 responses in the sera from vaccinated mice were monitored by flow cytometry (1:100 dilution). Pooled sera from mice vaccinated once with 4pox or 4pox plus IBM or negative controls were incubated with transfected cells. For IBM and A27, the cells were fixed and permeabilized as described for Fig. 1B. All other antigens (surface expressed) were examined using untreated cells. (B) Three weeks following the last vaccination, 4pox- and 4pox-plus-IBM-vaccinated mice were challenged with VACV. Negative-control DNA-vaccinated mice were also included in the challenge. Weights of each group were graphed as in Fig. 1C. (C) The percent survival was plotted for each group in panel B.

Five weeks after vaccination, animals were challenged with VACV. All mice began to lose weight on day 4, and this loss continued until day 8 (Fig. 2B). All negative-control animals succumbed or were euthanized by day 8. In contrast, while there was considerable weight loss, ∼30% of the 4pox-vaccinated mice succumbed to infection. This is consistent with previous experiments (Golden and Hooper, unpublished). Animals vaccinated with 4pox plus IBM all survived challenge (Fig. 2C). Compared to the 4pox group, weight loss was more rapid in the 4pox-plus-IBM group between days 2 and 5. This difference in weight loss between 4pox and 4pox-plus-IBM groups is statistically significant (P < 0.05, t test) on each of these days. However, 4pox-plus-IBM mice began to increase in weight on day 6 at a rate slightly higher than that of the 4pox group. This enhanced weight gain was not significantly different (P > 0.05, t test) (Fig. 2B). These data demonstrate that addition of the IBM can decrease mortality but does not decrease morbidity as measured by weight loss.

Mapping the antibody response against the IBM.

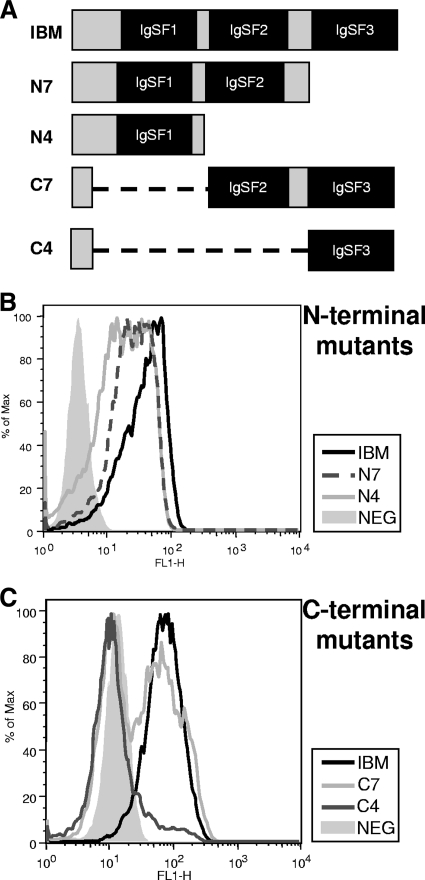

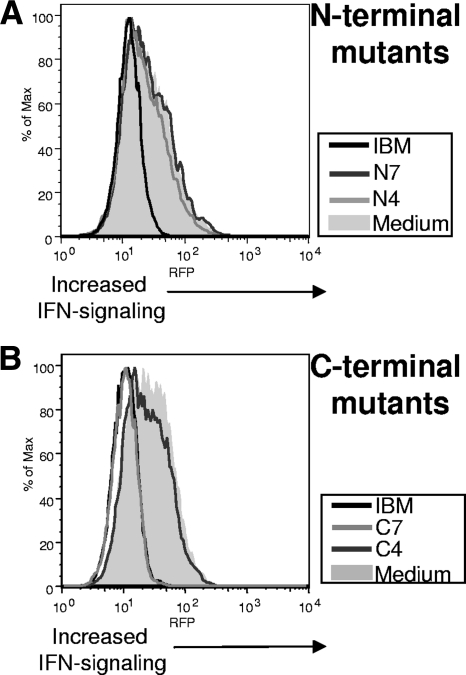

To gain a better understanding of where vaccine-generated anti-IBM antibodies were interacting with the IBM, we generated N- and C-terminal truncation mutants by PCR. COS cells were transfected with the N-terminal mutants (N7 and N4) and C-terminal mutants (C7 and C4) along with the full-length IBM (Fig. 3A). After 48 h, cells were fixed and permeabilized and the capacity of anti-IBM serum antibodies to interact with these mutants was then examined by flow cytometry. Pooled sera from IBM-vaccinated mice were incubated with each mutant and full-length molecule. As shown in Fig. 3B, antibodies in vaccinated animals interacted with N-terminal mutants N7 and N4. Anti-IBM antibodies also interacted well with C7 (Fig. 3C). Some interaction was observed with C4, as indicated by the forward scatter, but this was not nearly to the extent observed for C7, N7, or N4. These results indicate that vaccination with IBM leads to the generation of antibodies that interact with the majority of the molecule, with the exception being the extreme N-terminal region. We cannot rule out the possibility that we are missing antibody binding to discontinuous epitopes disrupted by the truncations.

FIG. 3.

(A) Mapping the regions of IBM bound by anti-IBM serum antibodies. (B and C) COS cells were transfected with N-terminal (B) or C-terminal (C) truncation mutants. Forty-eight hours posttranfection, cells were fixed and then permeabilized with BD Biosciences wash/permeabilization buffer. Fixed cells were then incubated with pooled mouse sera (1:100) for 1 h and then with a secondary anti-mouse antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (1:500). Samples were then examined by flow cytometry.

Characterizing the cell-binding and type I IFN-neutralizing regions of the IBM.

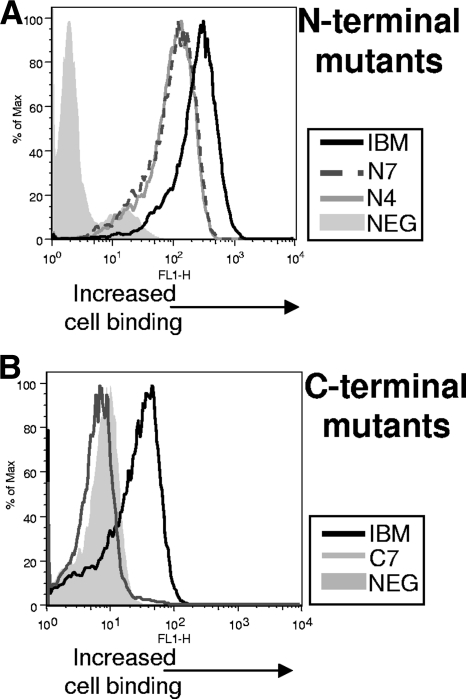

The involvement of each of the three IgSF domains in cell binding and/or type I IFN neutralization is unknown. While the mapping data showed that serum antibodies bound IgSF domains 1 and 2 and, to a lesser extent, domain 3, it was not clear what function each area possessed or how this may have impacted the lack of protection observed. It was possible that antibodies did not negate the IFN-neutralizing effects of IBM because they failed to bind to this region to a substantial level. Furthermore, it was not clear if our truncated mutants generated conformation-correct and stable molecules. Therefore, we next characterized the N- and C-terminal truncation mutants for their ability to bind cells and neutralize type I IFN. Mutants N7 and N4 contained IgSF domains 1 and 2 and domain 1, respectively. Mutants C7 and C4 contained the domains 2 and 3 and domain 3, respectively. We first examined the capacity of these mutants to bind to cells by using a novel flow-based binding assay. Plasmids encoding each molecule were transfected into COS cells, and 48 h posttransfection cell-free medium was adsorbed to new COS cell monolayers. Surface retention of the exogenous molecules was then examined by flow cytometry using anti-IBM antibodies. As seen in Fig. 4A, both N4 and N7 mutants bound to cells to a degree slightly less than that of the full-length molecule. In contrast, C7 did not bind cells (Fig. 4B). Similar results were obtained using a 293T cell line (data not shown). C4 also did not bind cells (data not shown). By deduction, these findings implicated the IgSF domain 1 as the region of the IBM containing the cell-binding activity.

FIG. 4.

Isolation of the cell-binding region of the orthopoxvirus type I IFN-binding molecule. Plasmids encoding N-terminal mutants N7 and N4 (A) or the C-terminal mutant C7 (B) were transfected into COS cells, and 48 h posttransfection, medium from cell cultures was collected and added to new cell monolayers. Cells were incubated for 2 h and then washed twice with PBS, trypsinized, and stained with anti-IBM antibodies (1:100) for 1 h, followed by incubation with an anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:500) for 30 min. Samples were then washed three times in FACS buffer and analyzed on a flow cytometer.

The ability of these mutants to neutralize IFN was examined using the 293:IFN cell line. COS cells were transfected with the full-length IBM or the N4, N7, C7, or C4 mutant. Forty-eight hours posttransfection, type I IFN-α was added to the cell-free medium containing either the IBM or mutants. After 2 h of incubation, medium was added to 293:IFN cell monolayers and incubated overnight. Expression of RFP was monitored by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 5, only C7 neutralized IFN to levels equivalent to those of the full-length IBM. This decrease in RFP expression was identical to that for medium without IFN (data not shown), indicating, as in Fig. 1, that there was nearly complete neutralization of IFN signaling. These results suggested that the IFN-neutralizing region of the IBM involved both IgSF domain 2 and domain 3. Together these data also indicate that the truncated mutants formed conformation-correct molecules, as they retained the two known functions of the IBM, cell binding and IFN neutralization.

FIG. 5.

Isolation of the type I IFN-neutralizing region of the poxvirus IBM. The ability of the IBM mutants to neutralize type I IFNs was investigated. Plasmids encoding truncated versions of the IBM were transfected into COS cells, and 48 h posttransfection cell cultures were collected. Media from COS cells transfected with the indicated N-terminal (A) or C-terminal (B) mutants were incubated with type I IFN-α (500 U/ml) for 2 h. After incubation, medium was added to 293:IFN cell monolayers. After 24 h, cells were analyzed on a flow cytometer for RFP expression.

Identifying the cell-binding and type I IFN-neutralizing regions of the IBM.

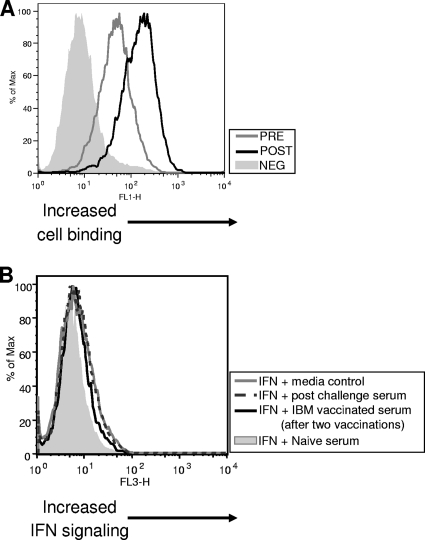

Based on the characterization data, we predicted that anti-IBM antibodies in vaccinated mice could impact both functions of IBM. We investigated this directly using two functional tests, an IBM cell-binding inhibition assay and an IFN signaling restoration test. The ability of anti-IBM serum antibodies to prevent cell binding was examined first. Anti-IBM serum antibodies from vaccinated mice were incubated with medium containing IBM generated by transfecting COS cells. As a control, some IBM-containing medium was not preincubated with antibody. IBM-containing medium was adsorbed onto fresh COS cells. Samples not preincubated with anti-IBM antibody were incubated at the postadsorption step, and then all samples were incubated with fluorescently labeled anti-mouse secondary antibody. The level of IBM bound to cells was analyzed using flow cytometry. Figure 6A shows that preincubation of IBM with sera from vaccinated mice reduced the amount of IBM capable of binding to target cells. These results indicated that anti-IBM serum antibodies generated in vaccinated animals were capable of preventing IBM cell binding.

FIG. 6.

Characterization of the function activity of serum antibodies against the IBM. (A) IBM cell-binding inhibition assay. Cell-free medium from COS cells transfected with IBM was not incubated (POST) or was incubated (PRE) with anti-IBM serum antibodies (1:50) for 2 h at 37°C. Media were then incubated with fresh COS cell monolayers for 2 h at room temperature and washed with PBS. Cells not preincubated (POST) with antibodies were incubated with anti-IBM antibodies (1:50) for 2 h and washed with PBS. All samples were next incubated with an anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody (1:500) for 1 h at room temperature. The negative control (NEG) consists of cells treated with medium not containing IBM, incubated with anti-IBM antibodies, and processed as described above. Samples were examined using flow cytometry. (B) IFN neutralization assay. 293 cells were incubated with or without (medium control) IBM-containing medium (derived from transfected COS cells) for 2 h. Cells were washed and incubated for an additional 2 h with serum antibodies (1:20) from mice vaccinated twice with IBM or mice vaccinated with IBM and challenged with VACV. Two controls were used for IFN signaling: mouse serum from a naïve mouse incubated with IBM-containing medium served as a negative control and medium not containing IBM served as a positive control. Medium containing 500 U/ml of IFN was added to all samples, and RFP expression (IFN signaling) was monitored by flow cytometry.

The extent to which anti-IBM serum antibodies inhibited the ability of IBM to neutralize type I IFNs was examined next. 293:IFN cells were incubated with or without IBM-containing medium for 2 h. Serum from vaccinated animals was then mixed with the cells, and subsequently cells were incubated in fresh medium containing 500 U/ml of IFN-α. IFN signaling was monitored by flow cytometry. Figure 6 shows an example of these results. Mice vaccinated twice with IBM developed antibodies that partially restored IFN signaling in IBM-treated 293 cells, compared to negative-control mouse serum (Fig. 6B). Nearly identical levels of signal restoration were detected using serum from other IBM-vaccinated mice (data not shown). These data were also replicated in another experiment (data not shown). Serum from a mouse surviving challenge restored signaling to levels identical to those of untreated 293:IFN cells. The enhanced IBM-neutralizing capability of serum from the challenged animal is consistent with an anticipated increase in antibody titer following challenge. These findings demonstrate that vaccination with pWRG/IBM leads to production of functionally relevant anti-IBM antibody.

DISCUSSION

Characterization of the IBM functional regions.

The individual functions of each of the three IgSF domains of the IBM are unclear. Based on the reduced affinity of VACV Wyeth for IFN-α2 and the fact that this strain had a truncated IBM, it was suggested that the IFN-binding activity may be on the C-terminal end of the molecule and the authors speculated that this meant that the cell-binding region was nearer the N-terminal end (2). To the best of our knowledge, this report is the first to dissociate the cell-binding and type I IFN-neutralizing functions of the IBM. Our findings are consistent with a model whereby the IgSF domain 1 possesses cell-binding activity and domains 2 and 3 are each involved in type I IFN neutralization (Fig. 4 and 5). We cannot rule out the possibility that IgSF domain 3 can bind type I IFN. These findings support the hypothesis generated by Alcami et al. (2) in which the N-terminal end was involved in cell binding and the C-terminal end was involved in IFN neutralization. Perhaps most interesting is the ability to generate two stable molecules which retain cell binding and type I IFN-neutralizing activity independently of each other. It was equally likely that complex folding of the molecule would have prohibited such dissociation and that the molecules would be unstable. We are currently investigating the biological utility, if any, of the separated cell-binding and type I IFN-neutralizing molecules. More critical to this report, these findings provided us with details of how the immune system responds to the IBM upon vaccination. Indeed, antibodies are generated against IgSF domains 1 and 2 and, to a much lesser extent, IgSF domain 3. These antibodies were able to functionally disrupt both the cell-binding and IFN-neutralizing capabilities of the IBM (Fig. 6). Our future vaccine studies will focus on using the IFN-neutralizing domain alone as a vaccine target, in an attempt to focus the immune response on this region of the IBM and to obtain more significant protection from viral challenge.

Protective efficacy of the VACV IBM.

Despite the fact that VARV has been eradicated from naturally infecting the population, this virus still poses a threat as a potential biological weapon and pretreatment strategies are still needed. The threat that an orthopoxvirus could be used as a bioterror agent has been amplified by several factors, including a deeper understanding of genes involved in orthopoxvirus tropism (for example, see reference 33), the advancement of synthetic biology, and the extreme malleability of the orthopoxvirus genome. While the live-virus vaccine (formerly Dryvax, now ACAM2000) is highly effective at establishing protective immunity, the serious adverse events associated with this prophylaxis, which include myocarditis and death (4, 21), warrant the development of alternative, safer vaccines. Some groups have developed attenuated versions of VACV as safer alternatives. These include MVA and Lc16m8 (13, 20, 23-25). Other groups have developed subunit protein and DNA-based vaccines. Indeed, our 4pox vaccine has been shown to protect mice and nonhuman primates against lethal orthopoxvirus challenges (16-19). Recently, we further enhanced the protective efficacy of the 4pox vaccine by optimizing the genes for codon usage and for mRNA stability (Fig. 1 and 2 and data not shown) and enhancing the immunogenicity of the L1 target by targeting the protein through the endoplasmic reticulum and to the cell surface (12). Additionally, we found that all four target gene plasmids could be mixed and delivered to the same cell without evidence of interference (data not shown), thus alleviating complications in the manufacturing process of the vaccine (i.e., separate gene delivery). With these modifications, the optimized 4pox vaccine protected ∼70% of challenged animals after a single dose. Following a single boost, the 4pox vaccine is statistically indistinguishable from the live-virus vaccine in the intranasal VACV murine challenge model (Fig. 1 and unpublished observations).

A recent study revealed that vaccination with the ECTV EVM166 protein, the VACV IBM ortholog, plus adjuvant conferred 100% protection on mice without much weight loss (35). This study demonstrated that the orthopoxvirus IBM is a viable vaccine target. We hypothesized that combining IBM with the optimized 4pox targets would augment the protective immunity of the vaccine and possibly confer complete protection after a single dose. We also predicted that IBM would be a poor immunogen when used alone in the VACV/murine i.n. challenge model because it has been shown that deletion of the IBM reduces virulence only ∼100-fold in mice compared to the 107-fold decrease with ECTV (32). We found that vaccination with IBM alone led to the generation of functional antibodies (Fig. 6) but did not afford significant protection against VACV challenge (Fig. 1). By combining IBM with the 4pox vaccine targets, we were able to increase protection as judged by the decrease in mortality. However, at later time points (after day 6) there was no difference in weight loss, indicating that the IBM provided only a slight augmentation of the 4pox vaccine efficacy and did not ameliorate morbidity. Curiously, at early time points animals receiving IBM and the 4pox targets had significantly more weight loss, until day 6, when the animals began adding weight. Similar results were obtained with the IBM that was used to replace the A27 component of the 4pox vaccine (data not shown). This could be explained by two possibilities. Since we used a DNA vaccine, it is theoretically possible that IBM expression persisted at the time of challenge. Its presence during infection, especially at the early stage, could have aided viral dissemination by depleting anti-IBM serum antibodies and/or perhaps enhancing type I IFN neutralization. Studies of DNA vaccines have found expression weeks after vaccination (22). However, we waited 5 weeks postvaccination to challenge, making continued expression less likely. It is also possible that anti-IBM antibodies targeting the cell-binding region helped increase in vivo distribution of the IBM by blocking the cell-binding function, thereby allowing the molecule to more efficiently disseminate throughout the host and advance viral spread (see below). We found that anti-IBM antibodies are capable of blocking IBM cellular attachment (Fig. 6).

Recently, it was reported that IBMs of MPXV and VARV may be a key player in strains that are more virulent (7), arguing that IBMs represent viable vaccine targets for these human-pathogenic orthopoxviruses. Accordingly, it would be of interest to determine if the IBM orthologs of VARV and/or MPXV are effective vaccine targets. If they indeed were, then it would argue that this molecule should be included in a pan-orthopoxvirus subunit vaccine. Additionally, targeting the IFN-neutralizing region exclusive of the cell-binding domain may yield greater protection when combined with the 4pox vaccine targets or alone by focusing the immune response on the most critical function of the IBM, that is, IFN neutralization. This approach would also eliminate the possibility that antibodies to the cell-binding region might enhance in vivo dissemination of this molecule. Our future studies will examine these possibilities. Because we have reported that the highly homologous orthopoxvirus A33 orthologs can be poorly cross protective due to subtle variations in antibody epitopes (11), we will also examine the cross-reactive potential of IBM orthologs.

Plotkin warned in a recent review about how large challenge doses may overwhelm vaccine-induced immunity and confuse the data (28). Indeed, the high-dose intranasal challenge model that we used in this study may be unsuitable for identifying subtle protective effects of certain poxvirus immunogens. Low-dose challenge models for poxviruses that cause disease in humans are needed. Accordingly, the newly described low-dose MPXV infection model in CAST/EiJ mice may provide a convenient platform to assess the protective efficacy of the IBM orthologs (3). In the CAST/EiJ model, the LD50 was calculated to be ∼680 PFU. A recent study found that the orthopoxvirus complement control protein failed to protect mice from lethal VACV challenge despite the development of functionally neutralizing antibodies (1). We also examined the protective effects of this molecule and found that despite its being immunogenic, no protection was observed (data not shown). Perhaps this study should also be revisited in a low-dose model to determine if indeed this molecule may have protective efficacy that was missed in the high-dose model. The 4pox vaccine protects nonhuman primates in high-dose MPXV challenge models and mice in high-dose VACV challenge models after two doses (16-19). However, to date, no subunit vaccine has achieved the protection, in terms of morbidity, conferred by the live-virus vaccination. Thus, the continued exploration of vaccine targets should allow the development of a vaccine that is not only safer than live-virus vaccination but also equally as protective.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by NIH Y1-AI-9426-01-IBM awarded to J.W.H. J.W.G. was a National Research Council postdoctoral fellow.

Housing and care of animals were carried out in accordance with the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animals animal care standards. Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author and not necessarily endorsed by the U.S. Army or the Department of Defense.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 September 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adamo, J. E., C. A. Meseda, J. P. Weir, and M. J. Merchlinsky. 2009. Smallpox vaccines induce antibodies to the immunomodulatory, secreted vaccinia virus complement control protein. J. Gen. Virol. 90:2604-2608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alcami, A., J. A. Symons, and G. L. Smith. 2000. The vaccinia virus soluble alpha/beta interferon (IFN) receptor binds to the cell surface and protects cells from the antiviral effects of IFN. J. Virol. 74:11230-11239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Americo, J. L., B. Moss, and P. L. Earl. 2010. Identification of wild-derived inbred mouse strains highly susceptible to monkeypox virus infection for use as small animal models. J. Virol. 84:8172-8180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bray, M. 2003. Pathogenesis and potential antiviral therapy of complications of smallpox vaccination. Antiviral Res. 58:101-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colamonici, O. R., P. Domanski, S. M. Sweitzer, A. Larner, and R. M. Buller. 1995. Vaccinia virus B18R gene encodes a type I interferon-binding protein that blocks interferon alpha transmembrane signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 270:15974-15978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies, D. H., M. M. McCausland, C. Valdez, D. Huynh, J. E. Hernandez, Y. Mu, S. Hirst, L. Villarreal, P. L. Felgner, and S. Crotty. 2005. Vaccinia virus H3L envelope protein is a major target of neutralizing antibodies in humans and elicits protection against lethal challenge in mice. J. Virol. 79:11724-11733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Del Mar Fernandez de Marco, M., A. Alejo, P. Hudson, I. K. Damon, and A. Alcami. 2010. The highly virulent variola and monkeypox viruses express secreted inhibitors of type I interferon. FASEB J. 24:1479-1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fang, M., H. Cheng, Z. Dai, Z. Bu, and L. J. Sigal. 2006. Immunization with a single extracellular enveloped virus protein produced in bacteria provides partial protection from a lethal orthopoxvirus infection in a natural host. Virology 345:231-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fogg, C., S. Lustig, J. C. Whitbeck, R. J. Eisenberg, G. H. Cohen, and B. Moss. 2004. Protective immunity to vaccinia virus induced by vaccination with multiple recombinant outer membrane proteins of intracellular and extracellular virions. J. Virol. 78:10230-10237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galmiche, M. C., J. Goenaga, R. Wittek, and L. Rindisbacher. 1999. Neutralizing and protective antibodies directed against vaccinia virus envelope antigens. Virology 254:71-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golden, J. W., and J. W. Hooper. 2008. Heterogeneity in the A33 protein impacts the cross-protective efficacy of a candidate smallpox DNA vaccine. Virology 377:19-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golden, J. W., M. D. Josleyn, and J. W. Hooper. 2008. Targeting the vaccinia virus L1 protein to the cell surface enhances production of neutralizing antibodies. Vaccine 26:3507-3515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hashizume, S., H. Yoshizawa, M. Morita, and K. Suzuki. 1985. Properties of attenuated mutant of vaccinia virus, LC16m8, derived from Lister strain, p. 421-428. In G. V. Quainnan (ed.), Vaccinia viruses as vectors for vaccine antigens. Elsevier Science Publishing Co, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

- 14.Heraud, J. M., Y. Edghill-Smith, V. Ayala, I. Kalisz, J. Parrino, V. S. Kalyanaraman, J. Manischewitz, L. R. King, A. Hryniewicz, C. J. Trindade, M. Hassett, W. P. Tsai, D. Venzon, A. Nalca, M. Vaccari, P. Silvera, M. Bray, B. S. Graham, H. Golding, J. W. Hooper, and G. Franchini. 2006. Subunit recombinant vaccine protects against monkeypox. J. Immunol. 177:2552-2564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hooper, J. W., D. M. Custer, C. S. Schmaljohn, and A. L. Schmaljohn. 2000. DNA vaccination with vaccinia virus L1R and A33R genes protects mice against a lethal poxvirus challenge. Virology 266:329-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hooper, J. W., D. M. Custer, and E. Thompson. 2003. Four-gene-combination DNA vaccine protects mice against a lethal vaccinia virus challenge and elicits appropriate antibody responses in nonhuman primates. Virology 306:181-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hooper, J. W., A. M. Ferro, J. W. Golden, P. Silvera, J. Dudek, K. Alterson, M. Custer, B. Rivers, J. Morris, G. Owens, J. F. Smith, and K. I. Kamrud. 2009. Molecular smallpox vaccine delivered by alphavirus replicons elicits protective immunity in mice and non-human primates. Vaccine 28:494-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hooper, J. W., J. W. Golden, A. M. Ferro, and A. D. King. 2007. Smallpox DNA vaccine delivered by novel skin electroporation device protects mice against intranasal poxvirus challenge. Vaccine 25:1814-1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hooper, J. W., E. Thompson, C. Wilhelmsen, M. Zimmerman, M. A. Ichou, S. E. Steffen, C. S. Schmaljohn, A. L. Schmaljohn, and P. B. Jahrling. 2004. Smallpox DNA vaccine protects nonhuman primates against lethal monkeypox. J. Virol. 78:4433-4443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kenner, J., F. Cameron, C. Empig, D. V. Jobes, and M. Gurwith. 2006. LC16m8: an attenuated smallpox vaccine. Vaccine 24:7009-7022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lane, J. M., and J. Goldstein. 2003. Adverse events occurring after smallpox vaccination. Semin. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. 14:189-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lauritzen, H. P., C. Reynet, P. Schjerling, E. Ralston, S. Thomas, H. Galbo, and T. Ploug. 2002. Gene gun bombardment-mediated expression and translocation of EGFP-tagged GLUT4 in skeletal muscle fibres in vivo. Pflugers Arch. 444:710-721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCurdy, L. H., B. D. Larkin, J. E. Martin, and B. S. Graham. 2004. Modified vaccinia Ankara: potential as an alternative smallpox vaccine. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38:1749-1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCurdy, L. H., J. A. Rutigliano, T. R. Johnson, M. Chen, and B. S. Graham. 2004. Modified vaccinia virus Ankara immunization protects against lethal challenge with recombinant vaccinia virus expressing murine interleukin-4. J. Virol. 78:12471-12479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morikawa, S., T. Sakiyama, H. Hasegawa, M. Saijo, A. Maeda, I. Kurane, G. Maeno, J. Kimura, C. Hirama, T. Yoshida, Y. Asahi-Ozaki, T. Sata, T. Kurata, and A. Kojima. 2005. An attenuated LC16m8 smallpox vaccine: analysis of full-genome sequence and induction of immune protection. J. Virol. 79:11873-11891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moss, B., J. L. Shisler, Y. Xiang, and T. G. Senkevich. 2000. Immune-defense molecules of molluscum contagiosum virus, a human poxvirus. Trends Microbiol. 8:473-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen, D. N., P. Kim, L. Martinez-Sobrido, B. Beitzel, A. Garcia-Sastre, R. Langer, and D. G. Anderson. 2009. A novel high-throughput cell-based method for integrated quantification of type I interferons and in vitro screening of immunostimulatory RNA drug delivery. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 103:664-675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plotkin, S. A. 2010. Correlates of protection induced by vaccination. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 17:1055-1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sakhatskyy, P., S. Wang, T. H. Chou, and S. Lu. 2006. Immunogenicity and protection efficacy of monovalent and polyvalent poxvirus vaccines that include the D8 antigen. Virology 355:164-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmaljohn, C., L. Vanderzanden, M. Bray, D. Custer, B. Meyer, D. Li, C. Rossi, D. Fuller, J. Fuller, J. Haynes, and J. Huggins. 1997. Naked DNA vaccines expressing the prM and E genes of Russian spring summer encephalitis virus and Central European encephalitis virus protect mice from homologous and heterologous challenge. J. Virol. 71:9563-9569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seet, B. T., J. B. Johnston, C. R. Brunetti, J. W. Barrett, H. Everett, C. Cameron, J. Sypula, S. H. Nazarian, A. Lucas, and G. McFadden. 2003. Poxviruses and immune evasion. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21:377-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Symons, J. A., A. Alcami, and G. L. Smith. 1995. Vaccinia virus encodes a soluble type I interferon receptor of novel structure and broad species specificity. Cell 81:551-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Werden, S. J., and G. McFadden. 2008. The role of cell signaling in poxvirus tropism: the case of the M-T5 host range protein of myxoma virus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1784:228-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiao, Y., L. Aldaz-Carroll, A. M. Ortiz, J. C. Whitbeck, E. Alexander, H. Lou, H. L. Davis, T. J. Braciale, R. J. Eisenberg, G. H. Cohen, and S. N. Isaacs. 2007. A protein-based smallpox vaccine protects mice from vaccinia and ectromelia virus challenges when given as a prime and single boost. Vaccine 25:1214-1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu, R. H., M. Cohen, Y. Tang, E. Lazear, J. C. Whitbeck, R. J. Eisenberg, G. H. Cohen, and L. J. Sigal. 2008. The orthopoxvirus type I IFN binding protein is essential for virulence and an effective target for vaccination. J. Exp. Med. 205:981-992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]