Abstract

A hallmark of airways in patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) is highly refractory, chronic infections by several opportunistic bacterial pathogens. A recent study demonstrated that acidified sodium nitrite (A-NO2−) killed the highly refractory mucoid form of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a pathogen that significantly compromises lung function in CF patients (S. S. Yoon et al., J. Clin. Invest. 116:436-446, 2006). Therefore, the microbicidal activity of A-NO2− (pH 6.5) against the following three major CF pathogens was assessed: P. aeruginosa (a mucoid, mucA22 mutant and a sequenced nonmucoid strain, PAO1), Staphylococcus aureus USA300 (methicillin resistant), and Burkholderia cepacia, a notoriously antibiotic-resistant organism. Under planktonic, anaerobic conditions, growth of all strains except for P. aeruginosa PAO1 was inhibited by 7.24 mM (512 μg ml−1 NO2−). B. cepacia was particularly sensitive to low concentrations of A-NO2− (1.81 mM) under planktonic conditions. In antibiotic-resistant communities known as biofilms, which are reminiscent of end-stage CF airway disease, A-NO2− killed mucoid P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, and B. cepacia; 1 to 2 logs of cells were killed after a 2-day incubation with a single dose of ∼15 mM A-NO2−. Animal toxicology and phase I human trials indicate that these bactericidal levels of A-NO2− can be easily attained by aerosolization. Thus, in summary, we demonstrate that A-NO2− is very effective at killing these important CF pathogens and could be effective in other infectious settings, particularly under anaerobic conditions where bacterial defenses against the reduction product of A-NO2−, nitric oxide (NO), are dramatically reduced.

Cystic fibrosis (CF) patients suffer from chronic debilitating pulmonary infections caused by a multitude of problem- atic, often antibiotic-resistant bacterial pathogens, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and Burkholderia cepacia (24). The most insidious form of P. aeruginosa is called mucoid P. aeruginosa, where 84 to 92% of mucoid isolates harbor mutations within the mucA gene, which encodes a cytoplasmic membrane-spanning anti-σ factor (16). With reduced or no MucA present in these bacteria, the σ factor AlgT(U) [or σE(22)] transcribes genes involved in the overproduction of alginate, an exopolysaccharide that inhibits the diffusion of oxygen and antibiotics (4, 17). Alginate production in the airways of CF patients significantly compromises the overall clinical course for CF patients (1, 2). The most problematic strains of S. aureus are commonly referred to as methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). The numbers of both MRSA and methicillin-susceptible strains in CF patients have increased in the United States during the last 10 years (34). Still, the most feared infectious agent from the standpoint of the CF patient and physicians is B. cepacia. Although comprising only ∼5% of CF infections, B. cepacia infection is often regarded as fatal for CF patients, as only a select few antibiotics are effective against it. In fact, it is recommended that B. cepacia-positive CF patients be isolated from other CF patients because of the significantly high likelihood of patient-to-patient transmission (26).

The presence of these pathogens in the airways of CF patients elicits a robust neutrophilic response that results in overproduction of proinflammatory mediators, such as elastase and reactive oxygen (O2−, H2O2, HOCl, HȮ, 1O2) and reactive nitrogen (nitric oxide [NO], peroxynitrite [ONOO−]) intermediates. This neutrophilic response causes progressive deterioration of the airway and ultimately leads to premature death of CF patients at a median age of ∼38 years (www.cff.org).

In nature, bacteria possess the capacity to shift between a planktonic (free-living) life style to surface-attached communities known as biofilms (i.e., during chronic infection). However, under conditions of either significant nutrient glut or environmental stress, surface-attached bacteria participate in an active process known as biofilm dispersion, by which organisms detach from surfaces or cells and colonize new microniches (3, 5). During human disease, biofilm-related infections are directly correlated with dramatic increases in antibiotic resistance, in many cases by 2 to 3 orders of magnitude (11, 21, 23). Furthermore, oxygen levels in the lung are depleted by what are now referred as chronic type II (unattached to surfaces) biofilm bacteria (9) enmeshed within the thick, stagnant mucus lining the CF airway and by neutrophils. In 2002, two seminal papers published by Worlitsch et al. (37) and Yoon et al. (39) showed that P. aeruginosa develops and thrives in hypoxic or anaerobic plugs within the thick mucus lining the CF airways. Of note, most antibiotics used to treat CF infections have significantly reduced efficacy under anaerobic conditions and, as such, are not clinically effective.

Recently, NaNO2 was shown to act as a potent biocide against mucoid P. aeruginosa, especially at the slightly acidic pH (∼6.5) of the CF airway surface liquid (38). Under anaerobic conditions, 15 mM NaNO2 (approximately 1,024 μg ml−1) was shown to kill mucA mutant P. aeruginosa at a rate of ∼1 log per day. The well-known, DNA-sequenced P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 was not killed by acidified sodium nitrite (A-NO2−) yet was bacteriostatic in an NO-dependent fashion. Similarly, Yoon et al. (39) showed that anaerobic P. aeruginosa cells that lack the ability to undergo the process of intercellular communication known as quorum sensing, a process that is fully operative during chronic CF lung infection (32), commit a metabolic suicide by overproduction of endogenous NO, a by-product of normal anaerobic respiration (8, 10, 11).

Another study demonstrated that NO2− (not acidified) repressed biofilm formation in S. aureus cultures (27). Thus, A-NO2− may be an unrecognized, inexpensive “silver bullet” for the treatment of problematic antibiotic-resistant CF pathogens by either inhibiting bacterial growth or killing such organisms in both planktonic and biofilm cultures. The enthusiasm for its use is supported by the fact that it is not an antibiotic. Rather, A-NO2− is a biocide against organisms that do not have the capacity to enzymatically remove it (e.g., via assimilatory [NO2− to NH3] or dissimilatory [NO2− to NO] nitrite reductases) or its reduction products (organisms that have a reduced capacity to remove NO). Thus, it is less likely that an organism will have the rapid adaptation that is often seen in antibiotic resistance.

In this study, the overall efficacy of A-NO2− was assessed for its ability to kill the three major CF pathogens, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, and B. cepacia, under anaerobic conditions. The CF airways have recently been found to harbor obligately anaerobic bacteria (36). Thus, the efficacy of anaerobic A-NO2− was first determined by using classical MIC measurements and standard NaNO2 killing assays. The effect of A-NO2− was also assessed on mature anaerobic biofilms and was found to be efficacious at killing each of the aforementioned pathogens. Given the urgent need for novel treatments against a variety of human infections caused by these important pathogens, this study presents a simple yet promising finding for effective therapies against CF airway pathogens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The following bacteria were used in this study: mucoid P. aeruginosa FRD1 muc22 (4), nonmucoid P. aeruginosa PAO1 (13), S. aureus USA300 (a renowned MRSA strain), and seven CF clinical isolates of B. cepacia. Mueller-Hinton broth medium (MH) containing 0.1 M sodium phosphate at pH 6.5 was used for studies involving MIC estimates and for A-NO2−-mediated killing. Anaerobic broth cultures used to determine MIC values contained 15 mM KNO3. For biofilm experiments, MH (pH, ∼7.4) was used for the aerobic growth incubation step and MH at pH 6.5 buffered with 0.1 M potassium phosphate was used for the anaerobic incubations in the presence of NaNO2. All experiments requiring anaerobic conditions were performed in a Coy chamber (Coy Laboratory Products, Ann Arbor, MI) containing ∼4% H2, 10% CO2, and 86% N2.

MIC determinations.

Sodium nitrite (NaNO2; Fisher, Fair Lawn, NJ) was prepared fresh daily in deionized distilled water. MIC values were determined by using standard techniques except that MH contained 0.1 M sodium phosphate (final pH, 6.5). Bacteria were inoculated to a final concentration of ∼5 × 105 CFU ml−1. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of antibiotic inhibiting visible growth after incubation for 24 h at 37°C.

NaNO2 killing studies.

To determine the effects of A-NO2− on bacterial viability under anaerobic conditions, organisms were enumerated at several time points in the presence and in the absence of various concentrations of NaNO2. Initial NaNO2 concentrations were 0.5×, 1×, and 2× MIC as defined during the MIC testing. Log-phase organisms were inoculated at 5 × 105 CFU ml−1 into test tubes containing MH (without KNO3). In some experiments with multiple B. cepacia strains, bacteria were enumerated at 0 and 24 h when cultured in the presence and in the absence of 512 μg ml−1 A-NO2−. Bacteria were then serially diluted with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) in 96-well microtiter dishes, and suspensions were plated on Luria-Bertani agar (10 g tryptone, 5 g yeast extract, and 5 g NaCl per liter). Cultures were incubated in an anaerobic chamber after the initial sample was removed. Bacteria were enumerated by serial dilution plating at ∼6-h intervals. Three independent samples were utilized per experiment.

Biofilm growth and confocal laser scanning microscopy.

Biofilms were grown in eight-well chambered coverglasses (Lab-Tek, Rochester, NY) as described by Yoon et al. (39) with the following exceptions. Overnight cultures (18 h) were grown in MH broth and were inoculated into the chambers (in duplicate) in a volume of 400 μl at a cell density of ∼5 × 105 CFU per ml. Samples were incubated aerobically at 37°C for 24 h. Spent medium was gently aspirated and replaced with MH (0.1 M potassium phosphate, pH 6.5) containing various amounts of NaNO2. Cultures were incubated in an anaerobic chamber for 2 days at 37°C. After incubation, one sample was used for enumeration of CFU (described above) and another was treated with a cell viability stain (BacLight; Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) composed of SYTO 9 (green fluorescence) and propidium iodine (red fluorescence). Biofilm images were obtained using an LSM 510 confocal laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss, Inc., Germany). The excitation and emission wavelengths for green fluorescence were 488 nm and 500 nm, while those for red fluorescence were 490 nm and 635 nm. All biofilm experiments were repeated at least three times. The live/dead ratios of the biofilms were calculated using the 3D for LSM (v.1.4.2) software (Carl Zeiss, Inc., Germany).

RESULTS

MIC testing of A-NO2− against P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, and B. cepacia.

Chronic CF airway disease is characterized by infections by a variety of bacteria, many of which are resistant to conventional antibiotic regimens. The very promising and potentially therapeutic results of Yoon et al. (38), who described the efficacy of A-NO2− in killing anaerobic mucoid mucA mutant planktonic and biofilm P. aeruginosa bacteria, prompted us to take the next logical step in determining whether and at what concentrations A-NO2− could kill nonmucoid P. aeruginosa PAO1 (representing early CF colonization) and potentially the two other major and clinically problematic CF pathogens, S. aureus and B. cepacia. The in vitro activities of A-NO2− at pH 6.5 for the various organisms are summarized in Table 1. A-NO2− was substantially more effective at killing these organisms under anaerobic versus aerobic conditions, in which 4-fold more A-NO2− (P. aeruginosa PAO1 and S. aureus USA300) to 8-fold more A-NO2− (P. aeruginosa FRD1) was required to inhibit aerobic growth of all strains tested. The MIC value for B. cepacia was not determined in planktonic culture because of an inability for cells grow anaerobically.

TABLE 1.

MICs of NaNO2 (pH 6.5) when tested against the three major CF pulmonary pathogens

| Organism | Reference or source | MIC (μg ml−1) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic | Anaerobic | ||

| P. aeruginosa FRD1 | 22 | 1,024 | 128 |

| P. aeruginosa PAO1 | 13 | 2,048 | 512 |

| S. aureus USA300 | 35 | 4,096 | 1,024 |

| B. cepacia | CF isolate | 512 | NDa |

ND, not determined.

A-NO2−-mediated killing of P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, and B. cepacia in planktonic culture.

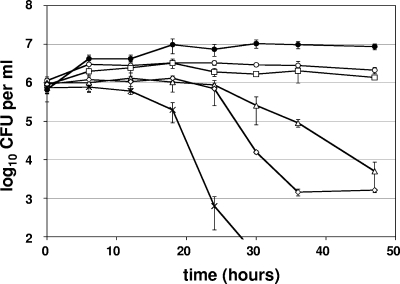

The effects of various concentrations of A-NO2− on the viability of the aforementioned bacteria were next ascertained over multiple time points. Depending on the organism and based on the results of Yoon et al. (38), the 1× MIC for A-NO2− can be bacteriostatic or bactericidal. The data in Fig. 1 indicate that both 64 μg ml−1 (0.5× MIC) and 128 μg ml−1 (1× MIC) had an inhibitory effect on P. aeruginosa FRD1 growth relative to untreated controls. In contrast, more than 2 logs of mucoid P. aeruginosa FRD1 bacteria were killed by 256 μg ml−1 A-NO2− after a 2-day incubation. Incubation with ≥1,024 μg ml−1 killed all bacteria (at the sensitivity of this assay) within 30 h.

FIG. 1.

A-NO2−-mediated killing of P. aeruginosa FRD1 under anaerobic conditions. NaNO2 concentrations tested were 0 μg ml−1 (closed circles), 64 μg ml−1 (open circles), 128 μg ml−1 (squares), 256 μg ml−1 (triangles), 512 μg ml−1 (diamonds), and 1,024 μg ml−1 (stars).The graphs display the averages and standard deviations of three independent cultures analyzed concurrently.

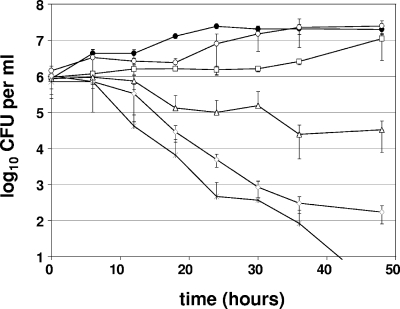

P. aeruginosa PAO1, a nonmucoid strain that does not harbor the mutations in the mucA gene that would enhance sensitivity to A-NO2− (16), also displayed sensitivity to A-NO2− (Fig. 2), albeit at much higher concentrations than required for P. aeruginosa FRD1. In fact, P. aeruginosa PAO1 required treatment with A-NO2− concentrations at or above 1,024 μg ml−1 (2× MIC). At concentrations below 1,024 μg ml−1, moderate growth inhibition was observed, but growth either resumed slightly or reached a plateau within 1 to 2 days.

FIG. 2.

A-NO2−-mediated killing of P. aeruginosa PAO1 under anaerobic conditions. NaNO2 concentrations tested were 0 μg ml−1 (closed circles), 256 μg ml−1 (open circles), 512 μg ml−1 (squares), 1,024 μg ml−1 (triangles), 2,048 μg ml−1 (diamonds), and 4,096 μg ml−1 (stars). The graphs display the averages and standard deviations of three independent cultures analyzed concurrently.

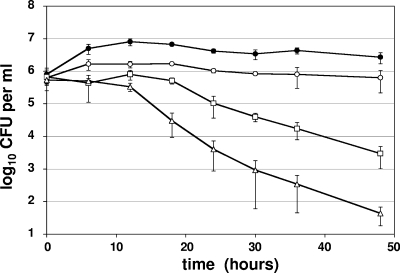

In contrast to P. aeruginosa PAO1, S. aureus USA300 was more sensitive to A-NO2− than were the aforementioned P. aeruginosa strains (Fig. 3). At a concentration of 512 μg ml−1, A-NO2− inhibited cell growth; however, ∼2 and 4 logs of bacteria were killed within 2 and 4 days of incubation in the presence of 1,024 μg ml−1 and 2,048 μg ml−1, respectively. We also tested the sensitivity of other methicillin-resistant COL (29) and glycopeptide-resistant Mu50 strains (14) as well as Staphylococcus epidermidis, and all were found to be killed by A-NO2− (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

A-NO2−-mediated killing of S aureus USA300 under anaerobic conditions. NaNO2 concentrations tested were 0 μg ml−1 (closed circles), 512 μg ml−1 (open circles), 1,024 μg ml−1 (squares), and 2,048 μg ml−1 (triangles). The graphs represent the averages of three independent cultures analyzed concurrently.

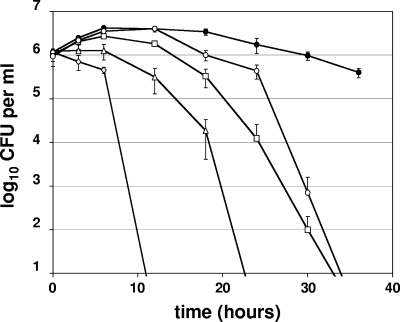

B. cepacia, one of the most notoriously antibiotic-resistant organisms of all bacteria (25), was highly susceptible to A-NO2− (Fig. 4), even more so than mucoid P. aeruginosa FRD1. Even 128 μg ml−1 killed all bacteria at the level of sensitivity of this assay within 48 h. As expected, higher concentrations of A-NO2− killed B. cepacia more effectively and rapidly. To exclude the possibility that the primary B. cepacia strain was abnormally sensitive to A-NO2−, killing experiments were also performed with six other B. cepacia strains derived from different chronically infected CF patients (Fig. 5). In the presence of A-NO2−, a significant loss in bacterial viability (18.2- to 270.3-fold decrease) was observed. In the absence of A-NO2−, less than 4-fold of the organisms died, and most increased slightly in cell density. These results suggest that B. cepacia strains are generally sensitive to anaerobic A-NO2−.

FIG. 4.

A-NO2−-mediated killing of B. cepacia under anaerobic conditions. NaNO2 concentrations tested were 0 μg ml−1 (closed circles), 128 μg ml−1 (open circles), 256 μg ml−1 (squares), 512 μg ml−1 (triangles), and 1,024 μg ml−1 (diamonds). The graphs display the averages and standard deviations of three independent cultures analyzed concurrently.

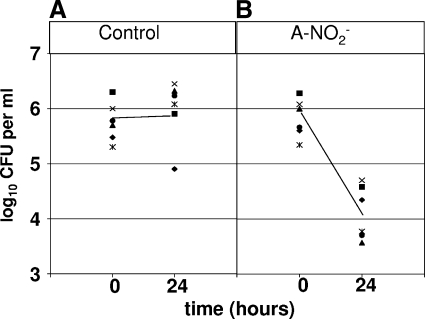

FIG. 5.

A-NO2−-mediated killing of several B. cepacia isolates. (A) Effect of 0 μg ml−1 NaNO2 on six B. cepacia isolates anaerobically maintained at 37°C for 0 and 24 h. (B) Effect of 512 μg ml−1 NaNO2 on six B. cepacia isolates anaerobically maintained at 37°C for 0 and 24 h.

A-NO2−-mediated killing in biofilms.

P. aeruginosa forms antibiotic-refractory biofilms enmeshed within the thick, inspissated mucus lining CF airways, an environment that is increasingly being found to harbor pockets that are anaerobic as well as strict anaerobes (8, 10, 36, 39). Thus, we elected to expand upon the results of the above planktonic experiments by identifying the extent to which A-NO2− could kill P. aeruginosa PAO1, S. aureus, and B. cepacia biofilms under strict anaerobic conditions.

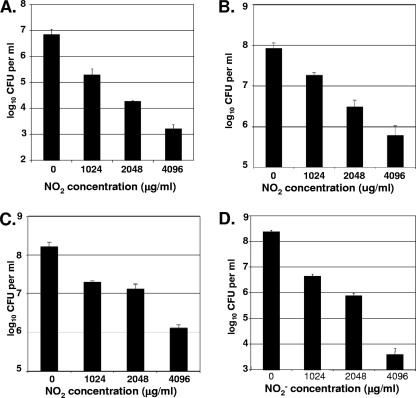

As a positive control for all biofilm experiments, we repeated the biofilm experiments of Yoon et al. (38), with the awareness that the culture medium was changed from L-broth to MH, as this alteration could influence the overall efficacy of A-NO2−. Viable cell enumerations (CFU analyses) (Fig. 6 A) revealed that ∼1.5 to 2 logs of killing were seen with 1,024 μg ml−1 (about 15 mM) A-NO2− with mucoid mucA22 mutant strain FRD1. Doubling the A-NO2− concentration yielded an additional 1-log increase in killing efficacy per sample. P. aeruginosa PAO1 did not show a substantial decrease in cell viability compared to P. aeruginosa FRD1 when incubated with A-NO2− (Fig. 6B). In contrast, bacterial counts showed that, although cell counts decreased with increasing concentrations of A-NO2−, cell death was ≤1 log as the concentration of A-NO2− was doubled. Exposure of organisms to 4,096 μg ml−1 A-NO2− killed ∼2 logs of bacteria relative to control samples.

FIG. 6.

A-NO2−-mediated killing of biofilm bacteria. Biofilms were grown for 1 day under aerobic conditions in MH medium. Following A-NO2− addition, biofilms were maintained under anaerobic conditions for an additional 2 days. The results represent CFU per ml of biofilms at different NaNO2 concentrations (means ± standard errors of means are shown; n = 3). (A) P. aeruginosa FRD1; (B) P. aeruginosa PAO1; (C) S. aureus USA300; (D) B. cepacia.

Figure 6C illustrates the effect of A-NO2− on S. aureus USA300 biofilms. The killing profile was similar to that of P. aeruginosa PAO1, in that a <1-log decrease of viable cells was observed at 1,024 μg ml−1 A-NO2− and about 2 logs of killing was observed when 4,096 μg ml−1 A-NO2− was added to the medium.

In biofilm experiments with B. cepacia (Fig. 6D), approximately 2 logs of bacteria were killed by 1,024 μg ml−1 A-NO2− compared to control samples. Biofilm cultures treated with 2,048 μg ml−1 A-NO2− caused a 3-log decrease in viability relative to the untreated control cultures; the cultures that contained 4,096 μg ml−1 killed ∼5 logs.

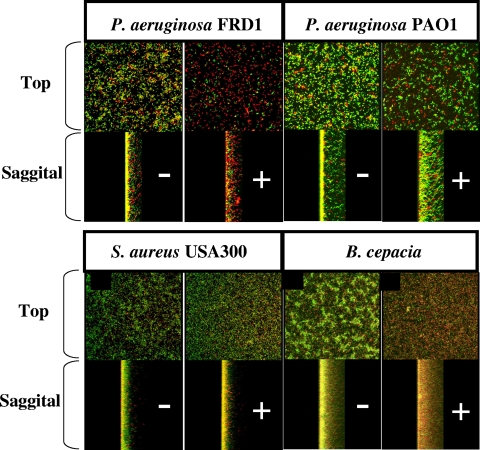

Finally, Fig. 7 A to D shows the A-NO2−-mediated killing of P. aeruginosa FRD1, P. aeruginosa PAO1, S. aureus USA 300, and B. cepacia enmeshed in biofilms, respectively. In general, the overall killing patterns (red indicates dead and green indicates viable cells) paralleled those determined in the CFU analyses.

FIG. 7.

A-NO2−-mediated killing of P. aeruginosa PAO1 biofilms. Biofilms were grown as described for Fig. 6, except for the NaNO2 concentrations in each sample. The − sign represents control biofilms, and those with a + sign were treated with 4,096 μg ml−1 NaNO2.

DISCUSSION

This study was initiated because of the continuously growing problem of antibiotic resistance in the three major pathogens of CF airway disease, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, and B. cepacia. Aerosolized tobramycin is a front-line aminoglycoside used routinely for the treatment of P. aeruginosa infections. In contrast, treatment of S. aureus infections is typically with aerosolized linezolid, rifampin, and fusidic acid. Finally, treatment of CF patients who have B. cepacia infection can involve a combination of antibiotics, including nebulized tobramycin, amiloride, meropenem, ceftazidime, piperacillin, cefepime, minocycline, tigecycline, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. The data provided in this study strongly suggest that A-NO2− could be used as a clinically prescribed anti-infective agent in the treatment of the major CF pathogens, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, and B. cepacia. Infections in CF patients appear to follow a pattern in which S. aureus is often involved early in infection and subsequent P. aeruginosa infection in up to 80% of patients (33). Other pathogens, such as B. cepacia, Stenotrophomonas maltophila, and Achromobacter xylosoxidans, may also be involved (33). Thus, it is important to identify antibiotics that can be utilized against the various infectious agents which cause infections in CF patients, at what concentrations those antibiotics are effective, and the timing of administration of these agents. The quality of medical care given to CF patients could be dramatically improved if inexpensive, readily available human-grade NaNO2 could be used to kill pathogens in CF patients, or to serve as a prophylactic.

The potential use of A-NO2− as an antimicrobial against CF pathogens was first described by Yoon et al. (38), who showed that A-NO2− at concentrations of ∼15 mM (∼1,024 μg ml−1) was bactericidal for anaerobic mucoid P. aeruginosa FRD1 and FRD1 palgT(U) but not for nonmucoid, mucA-proficient P. aeruginosa PAO1. In this study, 1,024 μg ml−1 A-NO2− inhibited planktonic P. aeruginosa PAO1 and killed S. aureus, B. cepacia, and P. aeruginosa FRD1 (Fig. 2 to 4). The biofilm experiments performed in this study demonstrated that 1,024 μg ml−1 nitrite killed 2 logs of P. aeruginosa FRD1 and less than 1 log of P. aeruginosa PAO1, results which are comparable to the data reported by Yoon et al. (38). The present study showed that a 4-fold increase in A-NO2− concentration (4,096 μg ml−1) killed 4 logs of FRD1 and 2 logs of PAO1.

In S. aureus, the effects of reactive nitrogen species have been primarily studied through the use of NO-releasing nanoparticles (12, 18). NO-releasing nanoparticles are highly effective (≥99%) in killing P. aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, S. aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Candida albicans biofilms (12). NO-emitting nanoparticles have also been shown to have antimicrobial activity on MRSA in a murine wound model (18). This nanoparticle NO delivery system has not been tested by the aspiration route. In another study, A-NO2− was shown to be an effective inhibitor of S. aureus biofilms (27). In theory, NaNO2 is simple to hydrate and nebulize; therefore, this compound might be a better choice as a novel therapeutic agent. In addition, the kinetics of classical NO donors, commonly referred to as NONOates, are radically different from those of A-NO2−, with NO2− being far more long-lived relative to the classical airway NONOate, S-nitroso-glutathione (30). To have a clearer idea of the efficacy of A-NO2− on a clinical strain of S. aureus, efficacy studies were initiated on the well-known MRSA S. aureus strain USA300 (35). A-NO2− inhibited planktonic S. aureus growth at 512 μg ml−1, and in biofilms it killed 1 log of cells at 1,024 μg ml−1 and 2 logs of cells at 4,096 μg ml−1.

Although concentrations of A-NO2− necessary for growth inhibition appear high relative to standard antibiotic concentrations (up to 1,024 μg ml−1 for anaerobic S. aureus), concentrations of 10 to 40 mg kg−1 are typically used in the curing of meat products (28). This fact suggests that humans have a high tolerance for NO2−. Furthermore, these concentrations of nitrite were delivered as a single dose. In a clinical setting, it might be possible to use smaller, more frequent doses of nitrite in order to maintain a level of nitrite sufficient to kill infectious bacteria.

The efficacy of NaNO2 against both planktonic and biofilm communities of B. cepacia was not expected, because this organism is resistant to numerous antibiotics routinely used to treat CF patients with infections. A previous study of Burkholderia cenocepacia gene expression demonstrated that under nitrogen stress, B. cenocepacia displayed a 20-fold increase in expression of a NO2−/sulfite reductase (6). Loprasert et al. (15) demonstrated through the construction of isogenic mutants that KatG and AhpC protect against reactive nitrogen species in Burkholderia pseudomallei. Taken together, the results of this study also suggest that the closely related Burkholderia species have developed a modest pathway for some protection against reactive nitrogen intermediates. Our work presented here suggests otherwise; planktonic B. cepacia was rapidly killed with relatively low concentrations of sodium nitrite (≥128 μg ml−1), and 2 logs of B. cepacia killing were observed with 1,024 μg ml−1 A-NO2− under biofilm conditions. In addition, intracellular B. pseudomallei has previously been examined for reactive oxygen and nitrogen bactericidal activities (20). Gamma interferon inhibited intracellular growth, and where bactericidal activity correlated with production of NO by macrophages. Taken together, the results of this study strongly suggest that NaNO2 would be an effective antimicrobial for the treatment of multiple Burkholderia infections.

Relatedly, NO gas has been shown to be an effective antimicrobial agent against S. aureus, Escherichia coli, P. aeruginosa, and Candida albicans as both a topical agent (7) and as an inhalant in pulmonary infections (19). Unfortunately at this time, there are no clinically approved delivery devices available for patient use, and the system used in those experimental studies is not practical for routine clinical use. A-NO2− is a better alternative, despite concerns presented by Miller et al. (19). Those concerns included the necessity of acidified conditions for nitrite effectiveness, nitrite toxicity, and aerosolization issues. However, the average pH (6.4 to 6.5) of CF lung mucus makes the issue of treatment involving prior acidification moot. Furthermore, the toxicology of sodium nitrite after oral or systemic administration in humans and animals is well established, with dose-dependent increases in methemoglobinemia/cyanosis as the primary problems (31). In separate studies, inhalation of nebulized NaNO2 daily for 28 days was safe and well tolerated in rats and dogs at doses up to 19 and 20 mg/kg of body weight, respectively. Modest and brief, transient increases in methemoglobin were the only changes noted at these doses (N. Hoglun [Aires Pharma], personal communication). Effective aerosolization is necessary for all aspirated antibiotics and will be well tested and optimized prior to clinical use. Future studies must determine what levels of NO2− can be maintained at different concentrations in the lung. If 512 μg ml−1 NO2− is sustainable in a CF lung by using an aspirator, the data presented here suggest that this level is sufficient to kill planktonic P. aeruginosa FRD1 and B. cepacia and inhibit growth of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa PAO1. NaNO2 appears to be a particularly effective inhibitor of mucoid P. aeruginosa and B. cepacia in CF patients with chronic CF lung infections and are very difficult to eradicate using the currently available antibiotics. In the absence of chronic infection, it might be possible to use lower levels of NaNO2 as a prophylactic. Therefore, the use of A-NO2− could prove clinically useful for treating CF patients with lung infections. These hypotheses remained to be tested, although frustratingly considerable financial support is required to move this potentially promising technology forward.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Aires Pharmaceuticals (San Diego, CA) and the nonprofit organizations Cystic Fibrosis Research, Inc. (Mountain View, CA) and Cure Finders, Inc. (Sevierville, TN).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 August 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ballmann, M., P. Rabsch, and H. von der Hardt. 1998. Long-term follow up of changes in FEV1 and treatment intensity during Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonisation in patients with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 53:732-737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bjarnsholt, T., P. O. Jensen, M. J. Fiandaca, J. Pedersen, C. R. Hansen, C. B. Andersen, T. Pressler, M. Givskov, and N. Hoiby. 2009. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms in the respiratory tract of cystic fibrosis patients. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 44:547-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davies, D. G., and C. N. Marques. 2009. A fatty acid messenger is responsible for inducing dispersion in microbial biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 191:1393-1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeVries, C. A., and D. E. Ohman. 1994. Mucoid-to-nonmucoid conversion in alginate-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa often results from spontaneous mutations in algT, encoding a putative alternate sigma factor, and shows evidence for autoregulation. J. Bacteriol. 176:6677-6687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donaldson, S. H., W. D. Bennett, K. L. Zeman, M. R. Knowles, R. Tarran, and R. C. Boucher. 2006. Mucus clearance and lung function in cystic fibrosis with hypertonic saline. N. Engl. J. Med. 354:241-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drevinek, P., M. T. Holden, Z. Ge, A. M. Jones, I. Ketchell, R. T. Gill, and E. Mahenthiralingam. 2008. Gene expression changes linked to antimicrobial resistance, oxidative stress, iron depletion and retained motility are observed when Burkholderia cenocepacia grows in cystic fibrosis sputum. BMC Infect. Dis. 8:121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghaffari, A., C. C. Miller, B. McMullin, and A. Ghahary. 2006. Potential application of gaseous nitric oxide as a topical antimicrobial agent. Nitric Oxide 14:21-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hassett, D. J., J. Cuppoletti, B. Trapnell, S. V. Lymar, J. J. Rowe, S. Sun Yoon, G. M. Hilliard, K. Parvatiyar, M. C. Kamani, D. J. Wozniak, S. H. Hwang, T. R. McDermott, and U. A. Ochsner. 2002. Anaerobic metabolism and quorum sensing by Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms in chronically infected cystic fibrosis airways: rethinking antibiotic treatment strategies and drug targets. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 54:1425-1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hassett, D. J., T. R. Korfhagen, R. T. Irvin, M. J. Schurr, K. Sauer, G. W. Lau, M. D. Sutton, H. Yu, and N. Hoiby. 2010. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm infections in cystic fibrosis: insights into pathogenic processes and treatment strategies. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 14:117-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hassett, D. J., S. V. Lymar, J. J. Rowe, M. J. Schurr, L. Passador, A. B. Herr, G. L. Winsor, F. S. L. Brinkman, G. W. Lau, S. S. Yoon, and S. H. Hwang. 2004. Anaerobic metabolism by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis airway biofilms: role of nitric oxide, quorum sensing and alginate production, p. 87-108. In M. M. Nakano and P. Zuber (ed.), Strict and facultative anaerobes: medical and environmental aspects. Horizon Bioscience, Wymondham, Norfolk, England.

- 11.Hassett, D. J., M. D. Sutton, M. J. Schurr, A. B. Herr, C. C. Caldwell, and J. O. Matu. 2009. Pseudomonas aeruginosa hypoxic or anaerobic biofilm infections within cystic fibrosis airways. Trends Microbiol. 17:130-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hetrick, E. M., J. H. Shin, H. S. Paul, and M. H. Schoenfisch. 2009. Anti-biofilm efficacy of nitric oxide-releasing silica nanoparticles. Biomaterials 30:2782-2789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holloway, B. W. 1969. Genetics of Pseudomonas. Bacteriol. Rev. 33:419-443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuroda, M., T. Ohta, I. Uchiyama, T. Baba, H. Yuzawa, I. Kobayashi, L. Cui, A. Oguchi, K. Aoki, Y. Nagai, J. Lian, T. Ito, M. Kanamori, H. Matsumaru, A. Maruyama, H. Murakami, A. Hosoyama, Y. Mizutani-Ui, N. K. Takahashi, T. Sawano, R. Inoue, C. Kaito, K. Sekimizu, H. Hirakawa, S. Kuhara, S. Goto, J. Yabuzaki, M. Kanehisa, A. Yamashita, K. Oshima, K. Furuya, C. Yoshino, T. Shiba, M. Hattori, N. Ogasawara, H. Hayashi, and K. Hiramatsu. 2001. Whole genome sequencing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 357:1225-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loprasert, S., R. Sallabhan, W. Whangsuk, and S. Mongkolsuk. 2003. Compensatory increase in ahpC gene expression and its role in protecting Burkholderia pseudomallei against reactive nitrogen intermediates. Arch. Microbiol. 180:498-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin, D. W., M. J. Schurr, M. H. Mudd, J. R. Govan, B. W. Holloway, and V. Deretic. 1993. Mechanism of conversion to mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa infecting cystic fibrosis patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90:8377-8381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin, D. W., M. J. Schurr, H. Yu, and V. Deretic. 1994. Analysis of promoters controlled by the putative sigma factor AlgU regulating conversion to mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: relationship to σE and stress response. J. Bacteriol. 176:6688-6696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinez, L. R., G. Han, M. Chacko, M. R. Mihu, M. Jacobson, P. Gialanella, A. J. Friedman, J. D. Nosanchuk, and J. M. Friedman. 2009. Antimicrobial and healing efficacy of sustained release nitric oxide nanoparticles against Staphylococcus aureus skin infection. J. Invest. Dermatol. 129:2463-2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller, S. S., and W. D. Rhine. 2008. Inhaled nitric oxide in the treatment of preterm infants. Early Hum. Dev. 84:703-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyagi, K., K. Kawakami, and A. Saito. 1997. Role of reactive nitrogen and oxygen intermediates in gamma interferon-stimulated murine macrophage bactericidal activity against Burkholderia pseudomallei. Infect. Immun. 65:4108-4113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moskowitz, S. M., J. M. Foster, J. Emerson, and J. L. Burns. 2004. Clinically feasible biofilm susceptibility assay for isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1915-1922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohman, D. E., and A. M. Chakrabarty. 1981. Genetic mapping of chromosomal determinants for the production of the exopolysaccharide alginate in a Pseudomonas aeruginosa cystic fibrosis isolate. Infect. Immun. 33:142-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Toole, G. A. 2003. To build a biofilm. J. Bacteriol. 185:2687-2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Razvi, S., L. Quittell, A. Sewall, H. Quinton, B. Marshall, and L. Saiman. 2009. Respiratory microbiology of patients with cystic fibrosis in the United States, 1995 to 2005. Chest 136:1554-1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saiman, L., and E. Garber. 30 July 2009. Infection control in cystic fibrosis: barriers to implementation and ideas for improvement. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Saiman, L., and J. Siegel. 2003. Infection control recommendations for patients with cystic fibrosis: microbiology, important pathogens, and infection control practices to prevent patient-to-patient transmission. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 24:S6-S52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schlag, S., C. Nerz, T. A. Birkenstock, F. Altenberend, and F. Gotz. 2007. Inhibition of staphylococcal biofilm formation by nitrite. J. Bacteriol. 189:7911-7919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sen, N. P., P. A. Baddoo, and S. W. Seaman. 1994. Rapid and sensitive determination of nitrite in foods and biological materials by flow injection or high-performance liquid chromatography with chemiluminescence detection. J. Chromatogr. A 673:77-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shafer, W. M., and J. J. Iandolo. 1979. Genetics of staphylococcal enterotoxin B in methicillin-resistant isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 25:902-911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shin, H. Y., and S. C. George. 2001. Microscopic modeling of NO and S-nitrosoglutathione kinetics and transport in human airways. J. Appl. Physiol. 90:777-788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shuval, H. I., and N. Gruener. 1972. Epidemiological and toxicological aspects of nitrates and nitrites in the environment. Am. J. Public Health 62:1045-1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh, P. K., A. L. Schaefer, M. R. Parsek, T. O. Moninger, M. J. Welsh, and E. P. Greenberg. 2000. Quorum-sensing signals indicate that cystic fibrosis lungs are infected with bacterial biofilms. Nature 407:762-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spicuzza, L., C. Sciuto, G. Vitaliti, G. Di Dio, S. Leonardi, and M. La Rosa. 2009. Emerging pathogens in cystic fibrosis: ten years of follow-up in a cohort of patients. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 28:191-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stone, A., and L. Saiman. 2007. Update on the epidemiology and management of Staphylococcus aureus, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, in patients with cystic fibrosis. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 13:515-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tenover, F. C., and R. V. Goering. 2009. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain USA300: origin and epidemiology. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64:441-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tunney, M. M., T. R. Field, T. F. Moriarty, S. Patrick, G. Doering, M. S. Muhlebach, M. C. Wolfgang, R. Boucher, D. F. Gilpin, A. McDowell, and J. S. Elborn. 2008. Detection of anaerobic bacteria in high numbers in sputum from patients with cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 177:995-1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Worlitzsch, D., R. Tarran, M. Ulrich, U. Schwab, A. Cekici, K. C. Meyer, P. Birrer, G. Bellon, J. Berger, T. Wei, K. Botzenhart, J. R. Yankaskas, S. Randell, R. C. Boucher, and G. Doring. 2002. Reduced oxygen concentrations in airway mucus contribute to the early and late pathogenesis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa cystic fibrosis airway infection. J. Clin. Invest. 109:317-325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoon, S. S., R. Coakley, G. W. Lau, S. V. Lymar, B. Gaston, A. C. Karabulut, R. F. Hennigan, S. H. Hwang, G. Buettner, M. J. Schurr, J. E. Mortensen, J. L. Burns, D. Speert, R. C. Boucher, and D. J. Hassett. 2006. Anaerobic killing of mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa by acidified nitrite derivatives under cystic fibrosis airway conditions. J. Clin. Invest. 116:436-446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoon, S. S., R. F. Hennigan, G. M. Hilliard, U. A. Ochsner, K. Parvatiyar, M. C. Kamani, H. L. Allen, T. R. DeKievit, P. R. Gardner, U. Schwab, J. J. Rowe, B. H. Iglewski, T. R. McDermott, R. P. Mason, D. J. Wozniak, R. E. Hancock, M. R. Parsek, T. L. Noah, R. C. Boucher, and D. J. Hassett. 2002. Pseudomonas aeruginosa anaerobic respiration in biofilms: relationships to cystic fibrosis pathogenesis. Dev. Cell 3:593-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]