Abstract

We performed analyses of the phenotypic and genotypic relationships focusing on biosyntheses of amino acids, purine/pyrimidines, and cofactors in three Lactobacillus strains. We found that Lactobacillus fermentum IFO 3956 perhaps synthesized para-aminobenzoate (PABA), an intermediate of folic acid biosynthesis, by an alternative pathway.

The biosynthetic pathways of primary metabolites have been established with model microorganisms such as Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. For a long time, the biosynthetic routes established were believed to be common to all microorganisms. However, we now realize that some microorganisms possess alternative biosynthetic pathways since the genome database has enabled us to determine the presence or absence of orthologs of the genes responsible for known biosynthetic pathways. These surveys were one of the triggers to find the 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 4-phosphate pathway (6) for isopentenyl diphosphate biosynthesis and the futalosine pathway (4) for menaquinone biosynthesis. As exemplified by the discovery of these pathways, microorganisms are expected to have additional alternative pathways for the biosynthesis of primary metabolites.

Lactobacilli are Gram-positive lactic acid-producing bacteria with low G+C contents and are utilized in the food industry (7, 15). These bacteria are known to have mutations in many primary metabolic pathways and require rich media containing various amino acids and nucleobases for their growth. After the whole-genome sequence of Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1 was determined in 2003 (5), phenotypic and genotypic analysis of the primary metabolic pathway in Lactobacillus strains commenced (1, 2, 8, 11, 12, 14). All of these analyses, however, were performed with a database of the known biosynthetic pathways. We are interested in an alternative pathway for biosynthesis of primary metabolites in microorganisms. Considering that some Lactobacillus strains do not possess some of the orthologs of the known biosynthetic pathways and that the genome sizes of Lactobacillus strains are relatively large (1.8 to 3.4 Mb) compared to those of the symbiotic bacteria, such as Mycoplasma strains (0.6 to 1.4 Mb) (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/catalog/org_list.html), we suspected the presence of an alternative primary metabolic pathway in Lactobacillus strains. In this paper, we examined the phenotypic and genotypic relationships in Lactobacillus fermentum IFO 3956 (genome size, 2.1 Mb) (10), Lactobacillus reuteri JCM 1112 (2.0 Mb) (10), and Lactobacillus brevis ATCC 367 (2.3 Mb) (9), all of which showed relatively good growth in LSP medium (3a) (20 g/liter glucose, 3.1 g/liter KH2PO4, 1.5 g/liter K2HPO4, 2 g/liter diammonium hydrogen citrate, 10 g/liter potassium acetate, 1 g/liter calcium lactate, 0.02 g/liter NaCl, 1 g/liter Tween 80, 0.5 g/liter MgSO4·7H2O, 0.05 g/liter MnSO4·5H2O, 0.5 g/liter CoSO4).

As for the amino acid, purine/pyrimidine, and vitamin (thiamine, nicotinate, pantothenate, riboflavin, and vitamin B6) biosynthetic pathways, the phenotypes of the three strains were essentially in agreement with the genotype (see Tables S1, S2, and S3 in the supplemental material) by the single-omission growth test, although we found several discrepancies, such as a prototrophic phenotype despite the absence of ortholog genes and an auxotrophic phenotype despite the presence of ortholog genes. However, these discrepancies were limited to one of the steps of the established biosynthetic pathway. In contrast, we observed a discrepancy between the phenotype and genotype for the biosynthesis of folic acid. Neither L. fermentum IFO 3956 nor L. reuteri JCM 1112 required folic acid for their growth, in contrast to L. brevis ATCC 367, which was auxotrophic for folic acid. The former two strains did not possess orthologs of pabA, -B, and -C (13), which were involved in the conversion of chorismate into para-aminobenzoate (PABA), an intermediate of folic acid biosynthesis. Therefore, we investigated the biosynthesis of PABA in L. fermentum IFO 3956 in more detail. Although pabA, -B, and -C were absent in strain IFO 3956, we found an ortholog of FolP (LAF_1336; EC 2.5.1.15), which catalyzes the formation of 7,8-dihydropteroate from PABA and 6-hydroxymethyl-dihydropterin diphosphate. Therefore, we examined if LAF_1336 showed the expected enzyme activity. We constructed a ΔfolP E. coli mutant by homologous recombination with the Lambda Red system (3) (see Table S4 and Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The constructed ΔfolP E. coli mutant required folic acid for its growth (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material) and was used in complementation experiments. The ΔfolP E. coli mutant transformed with a plasmid carrying a folP gene cloned from E. coli was able to grow reasonably in the absence of folic acid. Moreover, the ΔfolP E. coli mutant harboring a plasmid carrying LAF_1336 was also able to grow without folic acid (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), demonstrating that LAF_1336 complemented the folP defect.

We examined LAF_1336 using PABA as the substrate by two strategies. First, we constructed a ΔfolP ΔpabABC E. coli mutant for in vivo analysis. The ΔfolP E. coli mutant was used as the starting strain, and pabA, pabB, and pabC were successively disrupted by homologous recombination. The growth of the constructed mutant, in which PABA was not supplied from chorismate, was completely dependent on the presence of folic acid. When pUC118-FolP, carrying the E. coli folP gene, was introduced into the ΔfolP ΔpabABC E. coli mutant, the transformant was able to grow in medium containing PABA as expected (Table 1). The growth of the ΔfolP ΔpabABC E. coli mutant transformed with pUC118-1336 carrying LAF_1336 was also completely dependent on the presence of PABA. These results clearly suggested that LAF_1336 used PABA as the substrate for the formation of folic acid via 7,8-dihydropteroate.

TABLE 1.

Growth of the ΔfolP ΔpabABC mutant and its transformant harboring the E. coli folP gene or L. fermentum LAF_1336 genea

| Strain genotype | OD600 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Without PABA | With PABA | |

| WT [pUC118: folP] | 0.34 | 0.33 |

| WT [pUC118: LAF_1336] | 0.35 | 0.35 |

| ΔfolP [pUC118: folP] | 0.32 | 0.29 |

| ΔfolP [pUC118: LAF_1336] | 0.33 | 0.33 |

| ΔpabA ΔpabB ΔpabC ΔfolP [pUC118: folP] | 0.00 | 0.50 |

| ΔpabA ΔpabB ΔpabC ΔfolP [pUC118: LAF_1336] | 0.00 | 0.87 |

Growth of the wild type (WT), ΔfolP mutant, and ΔpabA ΔpabB ΔpabC ΔfolP mutant harboring pUC118 carrying the E. coli folP gene or carrying the LAF_1336 gene in M9 medium containing 1% glucose and ampicillin (0.1 mg/ml) was determined by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600).

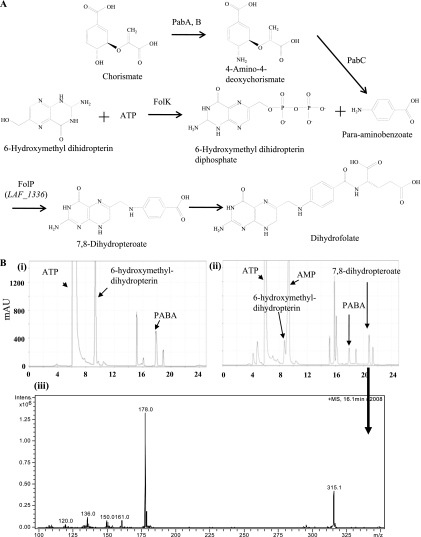

Next, we examined if LAF_1336 used PABA as a substrate in in vitro experiments. One of the substrates of LAF_1336 (FolP), 6-hydroxymethyl-dihydropterin diphosphate, was not commercially available; therefore, we employed a sequential enzymatic assay with 2-amino-4-hydroxy-6-hydroxymethyldihydropteridine pyrophosphokinase (FolK) (EC 2.7.6.3) and LAF_1336 (FolP) as the catalysts and commercially available 6-hydroxymethyl-dihydropterin as the substrate. E. coli FolK and LAF_1336 (FolP) were expressed as His-tagged proteins and maltose-binding protein (MBP)-fused proteins, respectively (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). The purified enzymes were incubated with 6-hydroxymethyl-dihydropterin in the presence of ATP and PABA, and the formation of 7,8-dihydropteroate was examined. As shown in Fig. 1, several specific products were detected by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis, and one of them was confirmed to be 7,8-dihydropteroate by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis. These in vivo and in vitro experiments clearly showed that LAF_1336 (FolP) used PABA as the substrate. This result strongly suggested that the strain would possess an alternative pathway for PABA biosynthesis. We are now attempting to clarify the details of this new pathway.

FIG. 1.

HPLC and LC-MS analyses of the products formed from 6-hydroxymethyl-dihydropterin with recombinant FolK and LAF_1336 (FolP). (A) Schematic of the dihydrofolate biosynthetic pathway from chorismate. (B) HPLC analysis of the reaction product without enzymes (i) and with both enzymes (ii). The peak of 7,8-dihydropteroate was subjected to LC-MS analysis (iii).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 3 September 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boekhorst, J., R. J. Siezen, M. C. Zwahlen, D. Vilanova, R. D. Pridmore, A. Mercenier, M. Kleerebezem, W. M. de Vos, H. Brüssow, and F. Desiere. 2004. The complete genomes of Lactobacillus plantarum and Lactobacillus johnsonii reveal extensive differences in chromosome organization and gene content. Microbiology 150:3601-3611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christiansen, J. K., J. E. Hughes, D. L. Welker, B. T. Rodríguez, J. L. Steele, and J. R. Broadbent. 2008. Phenotypic and genotypic analysis of amino acid auxotrophy in Lactobacillus helveticus CNRZ 32. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:416-423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3a.Elli, M., R. Zink, B. Marchesini-Huber, and R. Reniero. January 2002. Synthetic medium for cultivating Lactobacillus and Bifidobacteria. U.S. patent 6,340,585 B1.

- 4.Hiratsuka, T., K. Furihata, J. Ishikawa, H. Yamashita, N. Itoh, H. Seto, and T. Dairi. 2008. An alternative menaquinone biosynthetic pathway operating in microorganisms. Science 321:1670-1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kleerebezem, M., J. Boekhorst, R. van Kranenburg, D. Molenaar, O. P. Kuipers, R. Leer, R. Tarchini, S. A. Peters, H. M. Sandbrink, M. W. E. J. Fiers, W. Stiekema, R. M. K. Lankhorst, P. A. Bron, S. M. Hoffer, M. N. N. Groot, R. Kerkhoven, M. de Vries, B. Ursing, W. M. de Vos, and R. J. Siezen. 2003. Complete genome sequence of Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:1990-1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuzuyama, T., and H. Seto. 2003. Diversity of the biosynthesis of the isoprene units. Nat. Prod. Rep. 20:171-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.London, J. 1976. The ecology and taxonomic status of the lactobacilli. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 30:279-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makarova, K. S., and E. V. Koonin. 2007. Evolutionary genomics of lactic acid bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 189:1199-1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Makarova, K., A. Slesarev, Y. Wolf, A. Sorokin, B. Mirkin, E. Koonin, A. Pavlov, N. Pavlova, V. Karamychev, N. Polouchine, V. Shakhova, I. Grigoriev, Y. Lou, D. Rohksar, S. Lucas, K. Huang, D. M. Goodstein, T. Hawkins, V. Plengvidhya, D. Welker, J. Hughes, Y. Goh, A. Benson, K. Baldwin, J.-H. Lee, I. Díaz-Muñiz, B. Dosti, V. Smeianov, W. Wechter, R. Barabote, G. Lorca, E. Altermann, R. Barrangou, B. Ganesan, Y. Xie, H. Rawsthorne, D. Tamir, C. Parker, F. Breidt, J. Broadbent, R. Hutkins, D. O'Sullivan, J. Steele, G. Unlu, M. Saier, T. Klaenhammer, P. Richardson, S. Kozyavkin, B. Weimer, and D. Mills. 2006. Comparative genomics of the lactic acid bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:15611-15616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morita, H., H. Toh, S. Fukuda, H. Horikawa, K. Oshima, T. Suzuki, M. Murakami, S. Hisamatsu, Y. Kato, T. Takizawa, H. Fukuoka, T. Yoshimura, K. Itoh, D. J. O'Sullivan, L. L. McKay, H. Ohno, J. Kikuchi, T. Masaoka, and M. Hattori. 2008. Comparative genome analysis of Lactobacillus reuteri and Lactobacillus fermentum reveal a genomic island for reuterin and cobalamin production. DNA Res. 15:151-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Sullivan, O., J. O'Callaghan, A. Sangrador-Vegas, O. McAuliffe, L. Slattery, P. Kaleta, M. Callanan, G. F. Fitzgerald, R. P. Ross, and T. Beresford. 2009. Comparative genomics of lactic acid bacteria reveals a niche-specific gene set. BMC Microbiol. 9:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pastink, M. I., B. Teusink, P. Hols, S. Visser, W. M. de Vos, and J. Hugenholtz. 2009. Genome-scale model of Streptococcus thermophilus LMG18311 for metabolic comparison of lactic acid bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:3627-3633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pearson, W. R., and D. J. Lipman. 1988. Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 85:2444-2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teusink, B., F. H. van Enckevort, C. Francke, A. Wiersma, A. Wegkamp, E. J. Smid, and R. J. Siezen. 2005. In silico reconstruction of the metabolic pathways of Lactobacillus plantarum: comparing predictions of nutrient requirements with those from growth experiments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:7253-7262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wood, B. J., and W. H. Holzapfel. 1995. The genera of lactic acid bacteria, 1st ed. Blackie Academic and Professional, Glasgow, United Kingdom.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.