Abstract

We have previously reported that the prominent industrial enzyme producer Trichoderma reesei (teleomorph Hypocrea jecorina; Hypocreales, Ascomycota, Dikarya) has a genetically isolated, sympatric sister species devoid of sexual reproduction and which is constituted by the majority of anamorphic strains previously attributed to H. jecorina/T. reesei. In this paper we present the formal taxonomic description of this new species, T. parareesei, complemented by multivariate phenotype profiling and molecular evolutionary examination. A phylogenetic analysis of relatively conserved loci, such as coding fragments of the RNA polymerase B subunit II (rpb2) and GH18 chitinase (chi18-5), showed that T. parareesei is genetically invariable and likely resembles the ancestor which gave raise to H. jecorina. This and the fact that at least one mating type gene of T. parareesei has previously been found to be essentially altered compared to the sequence of H. jecorina/T. reesei indicate that divergence probably occurred due to the impaired functionality of the mating system in the hypothetical ancestor of both species. In contrast, we show that the sexually reproducing and correspondingly more polymorphic H. jecorina/T. reesei is essentially evolutionarily derived. Phenotype microarray analyses performed at seven temperature regimens support our previous speculations that T. parareesei possesses a relatively high opportunistic potential, which probably ensured the survival of this species in ancient and sustainable environment such as tropical forests.

Trichoderma reesei, the anamorph of the pantropical saprotrophic ascomycete Hypocrea jecorina, is used in the biotechnological industry for the production of cellulolytic and hemicellulolytic enzymes and recombinant proteins (13, 21). Accordingly, strong interest in this fungus has also recently reemerged in attempts to produce second-generation biofuels to reduce carbon dioxide emissions and the dependence on fossil fuels (oil) (15, 17).

Trichoderma reesei was originally collected on the Solomon Islands during World War II, where it destroyed canvas and other cellulose-containing materials of the U.S. army (18). It is unique among industrial fungi, as T. reesei was known only from the single isolate QM 6a for 50 years, and all genetically improved mutant strains used in biotechnology today have been derived from it. Kuhls et al. (14) found that T. reesei was indistinguishable from mycelial cultures of the pantropical ascomycete Hypocrea jecorina, on the basis of sequences of the internal transcribed spacer of the rRNA gene cluster and randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) fingerprinting analysis. Thus, they established the anamorph-teleomorph connection, which is still valid. Other putative anamorphs of H. jecorina have more recently been identified as frequent inhabitants of soils in tropical forests of Southeast Asia, South America, and the South Pacific region (1, 7, 12). Druzhinina et al. (4), however, have recently shown that the majority of anamorphic strains are genetically isolated from H. jecorina/T. reesei and form at least two new phylogenetic species. The more frequent one (T. parareesei nom. prov. [4]) was shown to be closely related to and also sympatric with H. jecorina but exclusively asexual (clonal or agamospecies). In that work we also provided some details on the ecophysiological characteristics of H. jecorina and its sister species. We showed that the extremely efficient cellulase-producing strains are present in all these phylogenetic species and that in general their carbon metabolisms are very similar, although the clonal species are more versatile and efficient in the utilization of their preferred substrata. No details on carbon utilization profiles or temperature-dependent growth rates have been presented. Striking differences between H. jecorina/T. reesei and T. parareesei in conidiation intensity, photosensitivity, and mycoparasitism have been found, all suggesting that the latter species occupies a separate ecological niche and has much stronger opportunistic potential than H. jecorina (4).

Here we provide the formal taxonomic description of Trichoderma parareesei on the basis of macro- and micromorphologies, carbon utilization profiles at different temperatures, and phylogenetic analysis. We show that this species likely resembles the ancestor of H. jecorina/T. reesei.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Material studied.

The strains used in this work, their origin, and the NCBI GenBank sequence accession numbers are listed in Table 1. The isolates are stored at −80°C in 50% glycerol in the Collection of Industrial Microorganisms of Vienna University of Technology (TUCIM). For convenience, TUCIM numbers (CPK) are used for the strains throughout the article; in addition, numbers of the original isolators' collections are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Strains of T. parareesei and H. jecorina/T. reesei as well as other species from Trichoderma section Longibrachiatum used in this studya

| Taxon | C.P.K. strain no. | Other strain no. | Origin | GenBank accession no. |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| chi18-5 | rpb2 | ||||

| Reesei subclade | |||||

| Trichoderma parareesei sp. nov. | 717 type | CBS 125925, TUB F-1066 | Mexico | HM182987 | HM182963 |

| 3426 | G.J.S. 07-26 | Ghana | HM182991 | HM182966 | |

| 661 | CBS 125862, TUB F-728 | Argentina | HM182990 | HM182965 | |

| 665 | TUB F-733 | Argentina | HM182992 | HM182967 | |

| 3420 | G.J.S. 04-41 | Brazil | HM182989 | HM182964 | |

| 634 | TUB F-730 | Sri Lanka | HM182993 | HM182968 | |

| 3692 | Ethiopia | HM182987 | HM182962 | ||

| Hypocrea jecorina | 160 | G.J.S. 85-236 | Celebes, Indonesia | HM183002 | HM182977 |

| 282 | G.J.S. 97-177 | French Guiana | HM182999 | HM182974 | |

| 1392 | G.J.S. 86-401 | Puerto Rico | HM183005 | HM182980 | |

| 1282 | G.J.S. 85-249 | Celebes, Indonesia | HM182998 | HM182973 | |

| 158 | G.J.S. 85-229 | Celebes, Indonesia | HM183003 | HM182978 | |

| 159 | G.J.S. 85-230 | Celebes, Indonesia | HM183004 | HM182979 | |

| 1127 | G.J.S. 93-23 | New Caledonia | HM183000 | HM182975 | |

| 1337 | G.J.S. 93-22 | New Caledonia | HM183001 | HM182976 | |

| 917 | CBS 383.78, QM 6a | Solomon Islands | HM182994 | HM182969 | |

| 3418 | G.J.S. 06-138 | Cameroon | HM182997 | HM182972 | |

| 3419 | G.J.S. 06-140 | Cameroon | HM182996 | HM182971 | |

| 155 | G.J.S. 86-404 | Brazil | HM182995 | HM182970 | |

| Other species from Trichoderma section Longibrachiatum | |||||

| Trichoderma sp. strain C.P.K. 524 | 523 | TUB F-1034 | Taiwan | HM183006 | HM182981 |

| 524 | TUB F-1038 | Taiwan | HM183007 | HM182982 | |

| Trichoderma sp. strain C.P.K. 1837 | 1837 | Ethiopia | HM183011 | HM182986 | |

| T. longibrachiatum | 1254 | CBS 48978 | Colombia | DQ087242b | EU401511b |

| T. saturnisporum | 1266 | CBS 33070, ATCC 18903 | Georgia, USA | HM183009 | HM182984 |

| H. schweinitzii | 2002 | CBS 121275 | Germany, Europe | HM183008 | HM182983 |

| T. pseudokoningii | 1277 | G.J.S. 81-300 | HM183010 | HM182985 | |

Strains of T. parareesei sp. nov., H. jecorina, and Trichoderma sp. strain C.P.K. 524 were published earlier (1, 4, 12). ATCC, American Type Culture Collection; CBS, Centralbureau voor Schimmelcultures; G.J.S., collection of Gary J. Samuels, USDA, Beltsville, MD; TUB, collection of George Szakacs, TU Budapest, Hungary.

Previously published by Jaklitsch et al. (8).

DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and sequencing.

Mycelia were harvested after 2 to 4 days of growth on 3% malt extract agar (MEA; Merck, Germany) at 25°C, and genomic DNA was isolated using a Qiagen (Hilden, Germany) DNeasy plant minikit following the manufacturer's protocol. Amplification of fragments of chi18-5 (GH18 chitinase CHI18-5, previously ech42) and rpb2 (RNA polymerase subunit II ß) was performed as described previously (9). PCR fragments were purified (PCR purification kit; Qiagen) and sequenced at Eurofins MWG Operon (Ebersberg, Germany).

Phylogenetic analysis.

Phylogenetic analysis was done essentially as described previously (4, 9). Briefly, DNA sequences were aligned by use of the Clustal X program (version 1.81) and visually checked in GeneDoc software (version 2.6). The possibility of intragenic recombination, which would prohibit the use of each locus for phylogenetic analysis, was tested by linkage disequilibrium-based statistics implemented in DnaSP software (version 4.50.3) (19). The neutral evolution was tested by Tajima's test, implemented in the same software. The interleaved NEXUS file was formatted using the PAUP* program (version 44.0b10) (22). As the sample size is relatively small (1,670 characters per 26 sequences for the biggest data set), the unconstrained GTR+I+G substitution model was applied to all sequence fragments (Table 2). Metropolis-coupled Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling was performed using the MrBayes program (version 3.0B4) with two simultaneous runs of four incrementally heated chains for 1 million generations. Bayesian posterior probabilities (PPs) were obtained from the 50% majority rule consensus of trees sampled every 100 generations after removal of the first trees using the “burnin” command. The number of discarded generations was determined for each run on the basis of visual analysis of the plot showing the generation versus the log probability of observing the data. PP values lower than 0.95 were not considered significant. Summaries of the model parameters and nucleotide characteristics of the loci used are given in the Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Nucleotide properties of phylogenetic markers and MCMC parametersb

| Parameter | Phylogenetic marker |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| rpb2 | chi18-5 | Concatenated data set | |

| Fragment characterization | Partial exon | Partial exon | Not applicable |

| No. of characters | 852 | 818 | 1,670 |

| No. parsimony informative | 80 | 88 | 168 |

| No. constant | 685 | 680 | 1,365 |

| Parameters of MCMC analysis | |||

| Mean nucleotide frequencya (A/C/G/T) | 0.24/0.28/0.28/0.20 | 0.23/0.33/0.24/0.20 | 0.24/0.30/026/0.20 |

| Substitution ratesa | |||

| A↔C | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| A↔G | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.25 |

| A↔T | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.06 |

| C↔G | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.09 |

| C↔T | 0.44 | 0.37 | 0.39 |

| G↔T | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.08 |

| Alphaa | 0.18 | 21.32 | 0.23 |

| No. of MCMC generations (106)/no. of runs | 1/2 | 1/2 | 2/2 |

| PSRFa | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1 |

| No. of chains/temp (λ) | 4/0.2 | 4/0.2 | 4/0.2 |

| Sampling frequency | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| No. of discarded first generations | 200 | 300 | 300 |

| Total tree length (substitutions/site) | 0.58 | 0.3 | 0.38 |

Alpha (shape parameter of the gamma distribution) and potential scale reduction factor (PSRF) values were estimated after GTR MCMC sampling and burning.

Twenty-nine sequences in total were analyzed.

Phenotype microarrays.

Growth rates on different carbon sources were analyzed using a phenotype microarray system for filamentous fungi (Biolog Inc., Hayward, CA), as described by Druzhinina et al. (2) and Friedl et al. (5). Briefly, strains were cultivated on 3% MEA for 5 days. Conidial inocula were prepared by rolling a sterile, wetted cotton swab over sporulating areas of the plates. The conidia were then suspended in sterile Biolog FF inoculating fluid (0.25% Phytagel, 0.03% Tween 40), gently mixed, and adjusted to a transmission of 75% at 590 nm (using a Biolog standard turbidimeter calibrated to the Biolog standard for filamentous fungi). A total of 90 μl of the conidial suspension was dispensed into each of the wells of the Biolog FF microplates (Biolog Inc.), which were incubated at 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, and 45°C in darkness. The optical density (OD) at 750 nm (for detection of mycelial growth [2, 5]) was measured after 18, 24, 42, 48, 66, 72, and 96 h using a microplate reader (Biolog Inc.). Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistica software package (version 6.1; StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK).

Growth rate determination on agar plates and morphological observations.

The micromorphology of conidiation structures, growth rates, and the comparative morphology of cultures were determined and morphological terms were applied as described by Jaklitsch (10). Growth rates at 15, 25, 30, and 37°C were recorded in a single experiment using 2 strains each of T. parareesei and T. reesei. In addition, images of cultures grown on 3% MEA for 5 days at 25°C under alternating 12 h of light/12 h of dark were taken. Color was determined as described by Kornerup and Wanscher (11).

Phytotoxicity assays.

Phytotoxicity assays were carried out using seeds of garden cress (Lepidium sativum) from Austrosaat AG (Vienna, Austria) and strains CBS 125925, CBS 125862, and C.P.K. 665 of T. parareesei and strains C.P.K. 917 (QM 6a), C.P.K. 1282, and C.P.K. 3419 of H. jecorina. Samples without Trichoderma were used as controls. The assay was designed on the basis of a 24-well plate, where each well was inoculated with one seed of L. sativum. Surface sterilization of the seeds was performed in 96% ethanol for 15 min, followed by washing of the seeds with sterile double-distilled water, with this step being repeated twice. Individual seeds were introduced into 20 of the 24 wells filled with synthetic low nutrition agar (SNA) medium (for 1 liter, 1 g of KH2PO4 and KNO3, 0.5 g MgSO4·7H2O and KCl, 0.2 g glucose and sucrose, and 20 g of agar-agar; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), leaving 4 wells for the control of the fungal growth. Pregrown mycelium was introduced to 20 seedlings per strain. The plates were incubated at 25°C under a rhythmic illumination cycle (12 h of light/12 h of dark) for 8 days. Afterwards, the plants were inspected under a stereomicroscope and the lengths of their stems were measured.

MycoBank accession number.

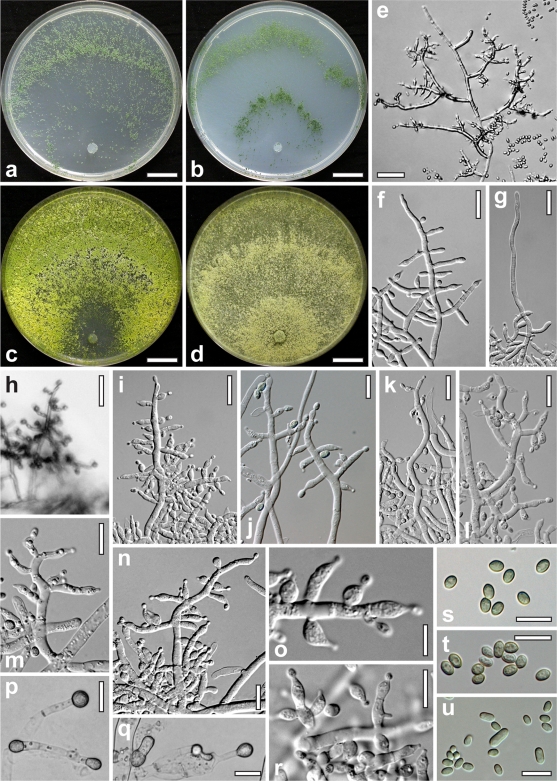

The sequence of Trichoderma parareesei Jaklitsch, Druzhinina & Atanasova, sp. nov., has been deposited in MycoBank under accession no. MB 515503 (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Trichoderma parareesei. (a to c) Cultures after 4 days on CMD (a), SNA (b) and PDA (c); (e) conidiophore without cover glass (9 days); (f) young conidiophore (3 days); (g) young conidiophore with sterile elongation (3 days); (h) conidiophore of a shrub on growth plate (2 days); (i to n) conidiophores after 3 days (i and n) and after 9 days (j to m); (o and r) phialides at 2 days (o) and 8 days (r); (p and q) chlamydospores (7 days); (s and t) conidia (8 days); (e to t) growth on CMD; (a to c, p, and q) growth at 30°C; (e and j to m) growth at 15°C; (f to i, n, o, and r to t) growth at 25°C; (a to c, f, g, i, and n to t) strain C.P.K. 717; (e, h, and j to m) strain C.P.K. 661; (d and u) Hypocrea jecorina (Trichoderma reesei); (d) culture on PDA after 4 days at 30°C (C.P.K. 917); (u) conidia (C.P.K. 1127, SNA, 25°C, 4 days). Scale bars: 15 mm (a to d), 30 μm (e and h), 15 μm (f, g, i, k, l, p, and q), 10 μm (j, m, n, and r to u), and 5 μm (o).

RESULTS

Taxonomy.

Differt a Trichodermate reesei absentia teleomorphosis, sporulatione multo magis abundante, conidiophoribus sinuosis et conidibus parvioribus, uniformioribus in forma et magnitudine. Phialides in agaro CMD lageniformes vel ampulliformes, 4.5 ad 11 μm longae, 2.5 ad 3.8 μm latae. Conidia viridia, ellipsoidea vel oblonga, glabra, 3.3 ad 6.2 μm longa, 2.5 ad 3.5 μm lata.

Morphology and growth rates of T. parareesei.

Table 3 presents some characteristics of T. parareesei. The morphology and growth rates of T. parareesei follow. Optimum growth at 30 to 37°C on all media. On CMD (Sigma corn meal agar plus 10% dextrose) mycelium covering the plate within 3 days at 25 to 37°C. Colony on CMD at 25 to 37°C hyaline, thin; mycelium dense, not zonate, concentrated on the agar surface, of thick, radially arranged primary hyphae and numerous delicate secondary hyphae forming a reticulum. Hyphal width decreasing with increasing temperature. Aerial hyphae scant, short, becoming fertile. Autolytic activity and coilings lacking or inconspicuous. No diffusing pigment produced or agar turning slightly yellowish, 1B3 to 3B3; no distinct odor produced. Chlamydospores at 30 to 37°C after 1 week uncommon, slightly increased in number relative to that at lower temperatures, terminal, mostly in thin, 3- to 4-μm-wide hyphae, less commonly intercalary in wider hyphae, 6 to 22 μm long by 4 to 16 μm wide, length/width ratios of 0.9 to 2.6 (n = 33), (sub)globose to pyriform, less commonly fusoid or oblong, smooth, sometimes 2 celled. Conidiation starting after 1 day on simple conidiophores of a straight, flexible main axis often sterile at the tip, and several tree-like side branches, paired, unpaired, or radially emergent from the main axis; appearing as minute white shrubs 0.3 to 0.6 mm in diameter, concentrated in proximal areas and in one to several diffuse, at higher temperatures often narrower, concentric zones. Shrubs loosely disposed and firmly attached to surface hyphae; erect, first with straight to sinuous sterile elongations, becoming green and entirely fertile; terminally 2.5 to 3.5 μm wide, downwards 4.5 to 5 μm. Consecutively, after ca. 3 days, dark green pustules to nearly 2 mm in diameter formed, more or less arranged in concentric zones. Pustules loose, transparent, first white with sterile ends or elongations, turning pale to dark green, maturing from inside, ends becoming fertile; consisting of a loose reticulum bearing several straight or sinuous main axes with highly variable, straight or distinctly sinuous side branches. Conidiophores (all branches) generally narrow, 2.0 to 4.5 μm wide, thick walled, and with thickenings to 5.5 to 6.5 μm when old, flexuous, loosely arranged, usually unpaired, in right angles or inclined upwards, holding solitary phialides in right angles along their length, directly, or terminally on a supporting cell often similar in shape (intercalary phialides) or on few-celled cylindrical branches, sometimes in whorls of 3 on intercalary phialides, but not originating at the same position. Phialides lageniform or ampulliform with often cylindrical neck, straight and symmetric or inequilateral and distinctly curved, with wide or constricted base, usually with distinct widening at or above the middle. Conidia formed in minute, mostly dry heads 10 μm in diameter. Conidia green, uniformly ellipsoidal, smooth, thick walled, eguttulate or with some minute guttules; scar indistinct or pointed; shape and size more variable, ellipsoidal to cylindrical at 37°C. On potato dextrose agar (PDA), mycelium covering the plate within 3 days at 25 to 37°C. Secondary hyphae forming a dense reticulum. Autolytic excretions conspicuous at the colony margin, positively correlated with increasing temperature. Conidiation on PDA and MEA conspicuously abundant, in numerous densely arranged and variably superposed bright yellow-green to dark green pustules (for cultures of T. parareesei and H. jecorina on 3% MEA, see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Diffusing pigment variable, yellow if present. On SNA, mycelium covering the plate within 3 days at 25 to 37°C. Colony similar to CMD; conidiation more abundant, denser, and more regularly arranged in concentric zones.

TABLE 3.

Colony phenotype and anamorph characteristic of the species discussed

| Parameter | T. parareesei sp. nov. | H. jecorina/T. reesei |

|---|---|---|

| Colony type on CMD | Conidia formed abundantly in shrubs and well-defined pustules | Only shrubs; no well-defined pustules formed |

| Colony radius (mm) at 48 h | ||

| CMD | ||

| 15°C | 19-21 | 8-19 |

| 25°C | 44-47 | 34-44 |

| 30°C | 50-56 | 44-55 |

| 37°C | 50-53 | 37-58 |

| PDA | ||

| 15°C | 15-16 | 9-16 |

| 25°C | 44-48 | 36-49 |

| 30°C | 53-56 | 45-59 |

| 37°C | 57-61 | 42-59 |

| SNA | ||

| 15°C | 17-18 | 9-15 |

| 25°C | 40-43 | 32-40 |

| 30°C | 50-55 | 40-60 |

| 37°C | 53-58 | 32-64 |

| Conidia | Uniformly ellipsoidal; more variable, ellipsoidal to cylindrical at 37°C | Variable, ellipsoidal or oblong with parallel sides |

| Conidium | ||

| Length (μm) | 3.3-6.2 (3.8-4.5)a | 3.5-9.0 (3.5-6.0) |

| Width at widest point (μm) | 2.5-3.5 (2.8-3.2) | 2.2-4.0 (2.5-3.3) |

| Length/width | 1.2-2.0b (1.3-1.5) | 1.2-2.7c (1.3-1.9) |

| Phialides | Lageniform or ampulliform, often with a cylindrical neck, usually with distinct widening at or above the middle | Lageniform |

| Phialide | ||

| Length (μm) | 4.5-11 (5-8) | 5.0-14.5 (6-10) |

| Width at widest point (μm) | 2.5-3.8 (2.7-3.5) | 2.2-4.0 (2.5-3.5) |

| Width at base (μm) | 1.4-3.2 (1.7-2.4) | 1.3-3.0 (1.7-2.5) |

| Length/width | 1.3-3.6 (1.6-2.7) | 1.5-4.6 (2-3.4) |

Data in parentheses represent the narrower ranges determined by the mean plus minus standard deviation.

n = 70.

n = 75.

Holotype.

The holotype was isolated from soil of a subtropical rain forest near Iguazu Falls, Argentina, on 4 September 1997, and is deposited as a dry culture (WU 30015; living cultures CBS 125925, C.P.K. 717, TUB F-1066).

Additional isolates examined were CBS 125862 (C.P.K. 661, TUB F-728) from subtropical rain forest, near Iguazu Falls, Argentina, 4 September 1997.

Habitat and distribution.

T. parareesei has been isolated from soils of subtropical and tropical areas in South America (Brazil, Argentina, Colombia), Central America (Mexico), Africa (Ghana and Ethiopia), and India (4). Hojos-Carvajal et al. (7) noted that the fungus occurs in soil of the African oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) in South America.

Anamorph morphology of Hypocrea jecorina/Trichoderma reesei.

To highlight differences in culture and anamorph morphologies, a short description of H. jecorina/T. reesei cultured in the same experiments is given here (Table 3). On CMD, mycelium covering the plate within 3 to 4 days at 25 to 37°C. Conidiation after 4 to 8 days at 25°C on CMD and SNA concentrated in a distal concentric zone, farinose, green; only shrubs, no well-defined pustules formed. Conidiophores straight, 2.5 to 5 μm wide, similar to those of T. parareesei in shrubs. Larger branches becoming coarsely warted with age. Phialides solitary, lageniform, straight, only rarely slightly curved, sometimes with long cylindrical necks. Conidia variable, ellipsoidal, or oblong with parallel sides, scar indistinct.

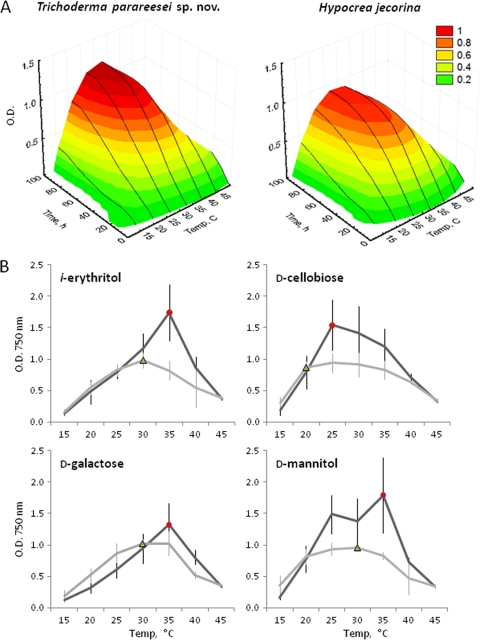

Temperature-dependent growth of T. parareesei and H. jecorina on multiple carbon sources.

We have recently reported that T. parareesei and H. jecorina exhibit qualitatively similar carbon source utilization profiles under standard temperature conditions (25°C) but respond differently to light (4). Moreover, it was noticed that T. parareesei showed a more variable utilization profile compared to that of H. jecorina. Here we performed phenotype microarrays (PMs) of both species at seven temperatures in darkness in order to get an advanced profile of carbon source utilization by T. parareesei in comparison to that of H. jecorina. Results show that in general both species have their growth optimum at temperatures between 28 and 35°C. However, T. parareesei is able to produce statistically higher biomass in this temperature range compared to that for H. jecorina (analysis of variance [ANOVA], P < 0.05). Figure 2 A shows the temperature-dependent growth rates of both species calculated for the 16 best carbon sources (cluster I) for H. jecorina, as estimated by Druzhinina et al. (2). The detailed PM profiles are given in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The most distinct difference between PM profiles of the two species was detected at 35°C. Figure 2B shows examples of faster growth of T. parareesei at 35°C on i-erythritol, d-mannitol, d-cellobiose, and d-galactose than the rate for H. jecorina. An inspection of the growth pattern on i-erythritol and d-mannitol can be used in the laboratory to distinguish the two species. In addition to the carbon sources listed above, similar patterns were also observed on gentobiose, d-mannose, d-xylose, d-arabitol, d-trehalose, α-d-glucose, and d-fructose, yet without statistical significance (ANOVA, P > 0.05).

FIG. 2.

Temperature-dependent growth of T. parareesei and H. jecorina on different carbon sources. (A) Temperature-dependent growth rates of both species calculated for the 16 best carbon sources (cluster I, l-arabinose, d-arabitol, d-cellobiose, dextrin, i-erythritol, d-fructose, gentobiose, α-d-glucose, maltotriose, d-mannitol, d-mannose, d-melezitose, d-trehalose, d-xylose, γ-aminobutyric acid), as estimated by Druzhinina et al. (2) for H. jecorina. The complete carbon source utilization profiles are given in Table S1 in the supplemental material. (B) Temperature-dependent growth of T. parareesei and H. jecorina on individual carbon sources. Vertical bars correspond to standard deviations, calculated on the basis of the profiles of six and five strains for T. parareesei and H. jecorina, respectively. Colored labels highlight the differences.

Phytotoxicity assays.

We have previously reported that T. parareesei is considerably different from H. jecorina with respect to its ecophysiological adaptation (4). Thus, we found that, contrary to H. jecorina, T. parareesei is better adapted to growth in light and is more competitive with epigeal fungi than H. jecorina. However, all strains of T. parareesei have been isolated from soil, suggesting that soil may be its natural habitat. In order to extend our knowledge on the ecology of T. parareesei, we have performed a pilot phytotoxicity assay, which tests the influences of T. parareesei and H. jecorina on the germination of seeds and on the growth of a model plant, Lepidium sativum. This plant was chosen for its rapid growth in soil-free cultivations. The results show that both T. parareesei and H. jecorina are, in fact, able to inhibit growth of L. sativum up to 40%, yet the plants were normally developed. Statistically supported differentiation was detected only between each of the investigated fungal species and the control samples (for T. parareesei, P = 0.0009 [ANOVA] and n = 59; for H. jecorina, P = 0.0002 and n = 67), but no statistically significant differences were found between the species. Furthermore, the variation of inhibition among the T. parareesei strains was minimal. In contrast, growth of the plants with H. jecorina was strain dependent; in particular, strain C.P.K. 3419 inhibited L. sativum plants the most conspicuously. Development of the rootlets in the presence of Trichoderma was observed to be strain specific, as some strains (C.P.K. 717 and C.P.K. 667 of T. parareesei and C.P.K. 3419 of H. jecorina) clearly inhibited maturation of Lepidium roots.

Evolution of T. parareesei.

The genealogical concordance phylogenetic species recognition criterion, based on three of the most polymorphic phylogenetic markers applied previously (4), showed that T. parareesei constitutes a cryptic phylogenetic species genetically isolated from H. jecorina. In order to learn about the evolution of these two species with respect to other related taxa, we used Bayesian phylogenetic analysis of nucleotide sequences of two relatively conserved phylogenetic markers, rpb2 and chi18-5, which allow alignments with other species of Trichoderma section Longibrachiatum (Fig. 3). The nucleotide properties of these loci and parameters of phylogenetic analyses are given in Table 2. The topology of the phylogram based on the combined data set (Fig. 3A) confirms the result of Samuels et al. (20) and shows that, indeed, T. longibrachiatum and species related to it (H. orientalis and Trichoderma sp. strain C.P.K. 1837 [3]) are the next genetic neighbors to the species studied in this work. Furthermore, it also revealed a monophyletic Reesei subclade combining T. parareesei, Trichoderma sp. strain C.P.K. 524, and H. jecorina (Fig. 3B). The Reesei subclade is characterized by relatively short intercladal genetic distances compared to those present between other species in the section. A detailed inspection of this subclade (Fig. 3B) revealed that T. parareesei does not occupy any separate clade but is most closely related to the hypothetical common ancestor of the whole Reesei subclade. This was also confirmed on both individual phylograms for rpb2 and chi18-5 (data not shown). Three strains of T. parareesei (C.P.K. 3692 [Ethiopia], C.P.K. 634 [Ghana], C.P.K. 3426 [Sri Lanka]) are closest to the ancestral node, while four other strains form a statistically supported subclade derived from it. The phylogram shows that both H. jecorina and Trichoderma sp. strain C.P.K. 524 derived from the ancestral state, which is contemporarily represented by T. parareesei. In contrast to T. parareesei, strains of H. jecorina show considerable infraspecific polymorphism and occupy the longest branches of the Reesei subclade. These data indicate that T. parareesei is evolutionarily older than H. jecorina and likely resembles the ancestor of the latter species.

FIG. 3.

Bayesian circular phylogram inferred from the concatenated data set of partial exons of rpb2 and chi18-5 phylogenetic markers. Symbols at the nodes correspond to PPs of >94%. Arrows point to clades/nodes of phylogenetic species. (A) Phylogenetic position of the Reesei subclade with respect to other species from Trichoderma section Longibrachiatum; (B) phylogenetic relations between species of the Reesei subclade (enlarged from panel A). The ex type strain of T. reesei QM 6a (C.P.K. 917) is underlined.

DISCUSSION

In this study we extend our earlier finding (4) of T. parareesei as a new phylogenetic species of Trichoderma section Longibrachiatum to a full taxonomic description. The use of an integrated approach consisting of morphological observation and description, temperature-dependent carbon source utilization profiling, and phylogenetic analysis resulted in a clear differentiation between T. parareesei and T. reesei, the anamorph of H. jecorina, where T. parareesei was erroneously ascribed to earlier (1, 7, 12).

Macro- and micromorphological characters.

Conidiation in T. parareesei is distinctly more abundant than in H. jecorina on all media at all temperatures. On richer media such as PDA and MEA, conidiation in T. parareesei is conspicuously abundant and is positively correlated with temperatures up to 37°C. Under such conditions, several generations of bright yellow-green pustules form consecutive superposed layers, resulting in a thick, coarsely tubercular colony surface. In H. jecorina, conidiation on PDA is usually yellow and turns green only slowly, while on CMD and SNA, only shrubs and no well-defined pustules are formed. Conidiophores of H. jecorina are comparable to those of T. parareesei and are formed in shrubs, but they are generally straighter, with slightly longer phialides and conidia that vary in shape and size more conspicuously than those of T. parareesei. Phialide length only rarely exceeds 10 μm in T. parareesei, while this is common in H. jecorina. The formation of a yellow pigment is variable among isolates of both species.

Reasons for genetic isolation and speciation.

Our data show that T. parareesei, a species that has lost its ability to reproduce sexually, likely closely resembles the anamorphic stage of a common ancestor of all three species detected in the Reesei subclade. We have recently demonstrated that although T. parareesei possesses both the MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 loci, the latter is essentially altered compared to that of H. jecorina, where both mating-type loci are functional even in vitro. Therefore, we speculate that the inability of sexual reproduction likely originated from mutations in the MAT1-2 gene (4). Here we used conservative phylogenetic markers (coding fragments of the chi18-5 and rpb2 genes) to infer the evolution of the group of species rather than to differentiate T. parareesei from the rest. The analyses show that, in fact, T. parareesei is the oldest taxon which apparently nearly stopped its evolutionary development and that H. jecorina and Trichoderma sp. strain C.P.K. 524 arose from it. This is in perfect agreement with our previous results, which showed abundant molecular footprints of sexual recombination for H. jecorina and none for T. parareesei (4). Thus, we conclude that T. parareesei is a relict agamospecies which resembles the ancestor of H. jecorina and Trichoderma sp. strain C.P.K. 524. In this case, it is interesting to speculate on reasons which led to the survival of T. parareesei. The reduction of sexual recombination is reflected in the low level of infraspecific polymorphism of T. parareesei, which theoretically makes the species vulnerable to changing environments. We think that the survival of T. parareesei was to a large extent possible due to the long-term stability of its habitat, the tropical forest, which is one of the most sustainable and ancient ecosystems on the planet. However, we have also observed that T. parareesei has a versatile phenotype in a broad range of temperatures, extensive conidiation, and fast growth rates, which altogether are characteristics in line with strongly opportunistic members of the genus, e.g., T. asperellum, T. longibrachiatum, and T. hamatum. As it is hard to imagine which mechanisms could be exploited by the agamospecies to gain new genetic/phenetic properties (6), we would rather suggest that in H. jecorina extensive production of propagules and growth on certain carbon sources was reduced during evolution. This hypothesis is well supported by the observations that H. jecorina has an unusual small genome compared to the sizes of the genomes of other ascomycetes and Trichoderma species (16; cf. also http://genome.jgi-psf.org/Trive1/Trive1.home.html and http://genome.jgi-psf.org/Triat1/Triat1.home.html), suggesting that its overall phenotype likely reflects some losses in the genome. Druzhinina et al. (4) also showed that H. jecorina is photoinhibited to a certain extent, while T. parareesei is well adapted to various lighting conditions. Moreover the two species also have differences in their antagonistic potential in dual confrontations with fungi pathogenic for plants, showing that T. parareesei is generally more competitive. These considerations call for a comparison of the genomes of T. parareesei and H. jecorina, because this may provide insights into the original genetic potential of this important industrial species, where speciation occurred by restriction to a narrow habitat and lifestyle.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported partly by Austrian Science Fund grant FWF P-19340-MOB to C.P.K. and FWF P22081-B17 to W.M.J.

We express special thanks to Aquino Benigno for his help with the DNA sequences.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 3 September 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Druzhinina, I. S., A. G. Kopchinskiy, M. Komon, J. Bissett, G. Szakacs, and C. P. Kubicek. 2005. An oligonucleotide barcode for species identification in Trichoderma and Hypocrea. Fungal Genet. Biol. 42:813-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Druzhinina, I. S., M. Schmoll, B. Seiboth, and C. P. Kubicek. 2006. Global carbon utilization profiles of wild-type, mutant, and transformant strains of Hypocrea jecorina. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:2126-2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Druzhinina, I. S., M. Komoń-Zelazowska, L. Kredics, L. Hatvani, Z. Antal, T. Belayneh, and C. P. Kubicek. 2008. Alternative reproductive strategies of Hypocrea orientalis and genetically close but clonal Trichoderma longibrachiatum, both capable to cause invasive mycoses of humans. Microbiology 154:3447-3459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Druzhinina, I. S., M. Komoń-Zelazowska, L. Atanasova, V. Seidl, and C. P. Kubicek. 2010. Evolution and ecophysiology of the industrial producer Hypocrea jecorina (Anamorph Trichoderma reesei) and a new sympatric agamospecies related to it. PLoS One 5:e9191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedl, M. A., M. Schmoll, C. P. Kubicek, and I. S. Druzhinina. 2008. Photostimulation of Hypocrea atroviridis growth occurs due to a cross-talk of carbon metabolism, blue light receptors and response to oxidative stress. Microbiology 154:1229-1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giraud, T., G. Refrégier, M. Le Gac, D. M. de Vienne, and M. E. Hood. 2008. Speciation in fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 45:791-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoyos-Carvajal, L., S. Orduz, and J. Bissett. 2009. Genetic and metabolic biodiversity of Trichoderma from Colombia and adjacent neotropic regions. Fungal Genet. Biol. 46:615-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaklitsch, W. M., M. Komon, C. P. Kubicek, and I. S. Druzhinina. 2005. Hypocrea voglmayrii sp. nov. from the Austrian Alps represents a new phylogenetic clade in Hypocrea/Trichoderma. Mycologia 97:1365-1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaklitsch, W. M., C. P. Kubicek, and I. S. Druzhinina. 2008. Three European species of Hypocrea with reddish brown stromata and green ascospores. Mycologia 100:796-815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaklitsch, W. M. 2009. European species of Hypocrea Part I. The green-spored species. Stud. Mycol. 63:1-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kornerup, A., and J. H. Wanscher. 1981. Taschenlexikon der Farben—1440 Farbnuancen und 600 Farbnamen. Muster-Schmidt Verlag, Zürich, Switzerland.

- 12.Kubicek, C. P., J. Bissett, C. M. Kullnig-Gradinger, I. S. Druzhinina, and G. Szakacs. 2003. Genetic and metabolic diversity of Trichoderma: a case study on South-East Asian isolates. Fungal Genet. Biol. 38:310-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kubicek, C. P., M. Mikus, A. Schuster, M. Schmoll, and B. Seiboth. 2009. Metabolic engineering strategies for the improvement of cellulase production by Hypocrea jecorina. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuhls, K., E. Lieckfeldt, G. J. Samuels, W. Kovacs, W. Meyer, O. Petrini, W. Gams, T. Börner, and C. P. Kubicek. 1996. Molecular evidence that the asexual industrial fungus Trichoderma reesei is a clonal derivative of the ascomycete Hypocrea jecorina. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:7755-7760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar, R., S. Singh, and O. V. Singh. 2008. Bioconversion of lignocellulosic biomass: biochemical and molecular perspectives. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 35:377-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinez, D., R. M. Berka, B. Henrissat, M. Saloheimo, M. Arvas, S. E. Baker, J. Chapman, O. Chertkov, P. M. Coutinho, D. Cullen, E. G. Danchin, I. V. Grigoriev, P. Harris, M. Jackson, C. P. Kubicek, C. S. Han, I. Ho, L. F. Larrondo, A. L. de Leon, J. K. Magnuson, S. Merino, M. Misra, B. Nelson, N. Putnam, B. Robbertse, A. A. Salamov, M. Schmol, A. Terry, N. Thayer, A. Westerholm-Parvinen, C. L. Schoch, J. Yao, R. Barabote, M. A. Nelson, C. Detter, D. Bruce, C. R. Kuske, G. Xie, P. Richardson, D. S. Rokhsar, S. M. Lucas, E. M. Rubin, N. Dunn-Coleman, M. Ward, and T. S. Brettin. 2008. Genome sequencing and analysis of the biomass-degrading fungus Trichoderma reesei (syn. Hypocrea jecorina). Nat. Biotechnol. 26:553-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Percival Zhang, Y. H., M. E. Himmel, and J. R. Mielenz. 2006. Outlook for cellulase improvement: screening and selection strategies. Biotechnol. Adv. 24:452-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reese, E. T., H. S. Levinsons, and M. Downing. 1950. Quartermaster culture collection. Farlowia 4:45-86. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rozas, J., J. C. Sanchez-DelBarrio, X. Messeguer, and R. Rozas. 2003. DnaSP, DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other methods. Bioinformatics 19:2496-2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samuels, G. J., O. Petrini, K. Kuhls, E. Lieckfeldt, and C. P. Kubicek. 1998. The Hypocrea schweinitzii complex and Trichoderma sect. Longibrachiatum. Stud. Mycol. 41:1-54. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seidl, V., and B. Seiboth. 2010. Trichoderma reesei: genetic strategies to improving strain efficiency. Biofuels 1:343-354. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swofford, D. L. 2002. PAUP*: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods), version 4.0b10. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.