Abstract

Recently, we isolated a new thiopeptide antibiotic, TP-1161, from the fermentation broth of a marine actinomycete typed as a member of the genus Nocardiopsis. Here we report the identification, isolation, and analysis of the TP-1161 biosynthetic gene cluster from this species. The gene cluster was identified by mining a draft genome sequence using the predicted structural peptide sequence of TP-1161. Functional assignment of a ∼16-kb genomic region revealed 13 open reading frames proposed to constitute the TP-1161 biosynthetic locus. While the typical core set of thiopeptide modification enzymes contains one cyclodehydratase/dehydrogenase pair, paralogous genes predicted to encode additional cyclodehydratases and dehydrogenases were identified. Although attempts at heterologous expression of the TP-1161 gene cluster in Streptomyces coelicolor failed, its identity was confirmed through the targeted gene inactivation in the original host.

Thiazolyl peptides (commonly called thiopeptides) are a group of macrocyclic peptide antibiotics that are produced by various bacteria, including members of the Actinomycetales order (mainly soil-derived Streptomyces spp.) and Bacillus spp. (2). Thiopeptide antibiotics are potent inhibitors of protein synthesis in Gram-positive bacteria, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium (VRE) (2). Molecular targets include the L11 binding region of the 23S rRNA and bacterial elongation factor Tu (EF-Tu) (2). Apart from translation inhibition, interference with transcription via targeting DNA-dependent RNA polymerase has also been reported for one thiopeptide antibiotic (12). Self-resistance to thiopepides can be conferred through the specific methylation of the 23S rRNA or mutations in genes encoding the target molecules, including the 23S rRNA, ribosomal protein L11, or EF-Tu (2).

Despite excellent in vitro properties, structure-inherent low solubility causing low bioavailability (4) has hampered the development of thiopeptide antibiotics for clinical use. In addition to the potent antibacterial activity, thiopeptides have been shown to possess antimalarial activity (18, 24) and anticancer activity (3). Increasing knowledge about thiopeptide biosynthesis (16) and their biological activities might provide the basis for pharmacological exploitation of this interesting class of antibiotics.

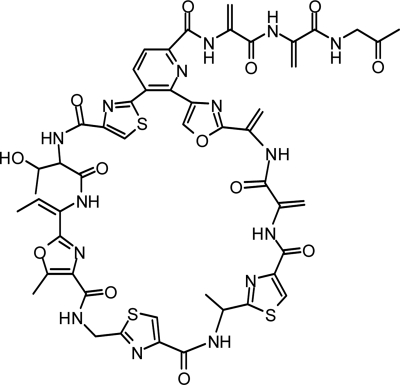

Recently, we isolated a new thiopeptide antibiotic, TP-1161, from the fermentation broth of a marine Nocardiopsis species (9). Structure elucidation of TP-1161 (Fig. 1) classified the compound as a series d thiopeptide, which comprise the majority of known thiopeptides, with members such as the thiocillins, thiomuracins, and GE2270A (2). A 2,3,6-trisubstituted pyridine domain central to a single peptide macrocycle, which typically carries multiple thiazole and oxazole heterocycles, is characteristic of the series d thiopeptides. The TP-1161 molecule shares a distinctive oxazole-thiazole-pyridine domain with a number of closely related thiopeptides of the d series, including the A10255 factors, berninamycin, and sulfomycin (2, 9).

FIG. 1.

Molecular structure of the thiopeptide antibiotic TP-1161.

Elucidation of the biosynthetic origin of several thiopeptides in the beginning of 2009 (14, 17, 29) revealed that these antibiotics are synthesized from chromosomally encoded precursor peptides that contain the amino acids constituting the backbone of the final thiopeptide framework at their C terminus. The ribosomally synthesized precursor peptide is transformed in a series of posttranslational enzymatic modifications into the final macrocyclic structure featuring multiple heterocycles and dehydrated amino acids. The core modifications, including heterocyclization, dehydrogenation, and dehydration of amino acid residues, seem to be catalyzed by a set of five enzymes most of which have distant homologs in biosynthetic pathways of other tailored ribosomal peptides, such as lantibiotics and cyanobactins (16). Here, we report identification, cloning, and analysis of the gene cluster governing biosynthesis of thiopeptide TP-1161 and propose the biosynthetic pathway for this antibiotic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General methods.

DNA isolation and manipulations were carried out according to standard methods for Escherichia coli (26) and Streptomyces (15). Restriction enzymes, DNA ligase, and other materials for recombinant DNA procedures were purchased from standard commercial sources and used as provided. Isolation of DNA fragments from agarose gels and purification of PCR products were performed using QIAquick Gel extraction and PCR purification kits (Qiagen). Promega's Wizard Plus SV minipreps DNA purification system or the NucleoBond Xtra plasmid DNA purification kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) were used for isolation of plasmids and cosmids. The Qiagen DNeasy blood and tissue kit was used for isolation of genomic DNA from Nocardiopsis and Streptomyces strains. Large-scale genomic DNA isolation for library construction and genome sequencing of Nocardiopsis sp. strain TFS65-07 was performed using the Kirby mix procedure (15). PCRs were performed using the Expand high-fidelity PCR system (Roche Applied Science). Southern blot analyses were carried out using positively charged nylon membranes and digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled probes prepared using the PCR DIG probe synthesis kit or DIG High Prime DNA labeling and detection starter kit II (Roche Applied Science). DNA sequencing from cosmids and plasmids was performed by Eurofins MWG Operon (Ebersberg, Germany).

Bacterial strains, plasmids, cosmids, and culture conditions.

All bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material). Nocardiopsis sp. strain TFS65-07 was newly isolated from fjord sediments (9), and Streptomyces coelicolor M512 was kindly provided by Mervyn Bibb, John Innes Centre (Norwich, United Kingdom). The ReDirect Escherichia coli strains for λ-Red-mediated recombination experiments were obtained from the John Innes Genome Laboratory (Norwich, United Kingdom). E. coli DH5α was used as a general host for all cloning experiments. E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani liquid medium or on agar medium supplemented with the appropriate antibiotic(s). Kanamycin (50 μg/ml), ampicillin (100 μg/ml), nalidixic acid (30 μg/ml), and tetracycline (5 μg/ml) were used for selective growth of recombinant E. coli and actinomycete strains. MS agar (15) was used for intergeneric conjugation from E. coli S17.1 to Nocardiopsis sp. strain TFS65.07 as described previously (15). ISP2 agar medium (Difco) (0.75×), prepared with 0.5× artificial seawater (1× artificial seawater consists of 0.425 M NaCl, 0.009 M KCl, 0.0093 M CaCl2, 0.0255 M MgSO4, 0.023 M MgCl2, and 0.002 M NaHCO3) was used for growth and sporulation of Nocardiopsis sp. strain TFS65-07, while recombinant TFS65-07 strains were selected for and maintained on 0.75× ISP2 agar supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin. Liquid ISP2 medium was used as seed medium and fermentation of Nocardiopsis sp. strain TFS65-07 and recombinant strains thereof, while TP-1161 production was performed in PM4 medium (15 g/liter glucose, 15 g/liter soy meal, 5 g/liter corn steep liquor, 2 g/liter CaCO3, 1× artificial seawater to 1 liter, pH 7.8). S. coelicolor M512 and recombinant strains thereof were maintained on MS or ISP2 agar.

Genome sequencing and de novo genome sequence assembly for Nocardiopsis sp. strain TFS65-07.

Genomic shotgun sequencing of Nocardiopsis sp. strain TFS65-07 was performed by Fasteris SA (Switzerland) using the Illumina sequencing technology. Sequence data were obtained from an Illumina GA-II instrument from two rounds of sequencing cycles with 36 cycles in each round using the Chrysalis 36-cycle v2.0 sequencing kit. De novo assembly of sequence data was performed using the Velvet software version 0.7.18, and the software was run with the PE (paired-end) option for hash values of 19, 21, 23, 25, 27, 29, and 31. A minimum length of 100 bases was required to retain a contig, and quality control sequences were used to estimate the average insert size for each sample. The standard deviation for the insert length was set at 20 bases, and the assembly process was repeated three times to refine the data set input values. The first assembly was carried without “k-mer” (hashed sequences of k bases from each reads) expected coverage and the estimated average insert size from quality control sequences. This assembly was used to calculate the average k-mer coverage. A second assembly was carried with the calculated average k-mer coverage and the estimated average insert size. These contigs were used to carry a MAQ mapping (Mapping and Assembly with Qualities, version 0.7.1, as described below) to obtain a more precise estimation of the whole data insert size, and the k-mer expected average coverage was also recalculated. The final assembly was built from the recalculated k-mer average coverage and the MAQ average insert size. The MAQ program was used to map reads with a maximum set at 2 mismatches in the first 24 bases. It was then extended to the remaining bases. Reads mapping to several positions on the references with the same mapping quality (i.e., number of mismatches and quality of the bases generating the mismatches) were attributed at random to one of them. The MAQ software then validated the mapping obtained by comparing the paired end of each read orientation and position. An average insert size of 227 bp was calculated from all reads fulfilling both criteria. Most of the reads could be assembled, and a large fraction (10,144,032 out of 10,903,436 mapped reads) in pairs was obtained, further validating the assemblies. The final assembly had a total length of 6,029,016 bp spanning 373 contigs with an average size of 16 kb. The genome size of Nocardiopsis sp. strain TFS65-07 is comparable to that of the only Nocardiopsis genome sequenced to date, Nocardiopsis dassonvillei subsp. dassonvillei DSM 43111 (http://genome.jgi-psf.org/nocda/nocda.info.html). Nocardiopsis dassonvillei features a 5,767,958-bp chromosome and a 775,354-bp plasmid.

Identification and bioinformatics analysis of the thiopeptide antibiotic TP-1161 biosynthetic gene cluster.

The predicted amino acid sequence of the unmodified structural peptide constituting the backbone of thiopeptide antibiotic TP-1161 was deduced from the final, posttranslationally modified molecule (Fig. 1) and used for mining the Nocardiopsis sp. strain TFS65-07 draft genome. Manual annotation of genes surrounding the TP-1161 precursor peptide gene was done by identifying protein-coding DNA sequences using the FramePlot 4.0 Beta program (http://nocardia.nih.go.jp/fp4/) and analyzing predicted protein sequences using the protein BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Proposed functions of open reading frames in the TP1161 biosynthetic gene cluster and surrounding regions

| Gene | Size of protein (no. of amino acids)a | Protein homologa | Source of protein homolog | % identity/% similarityb | Proposed function | Homolog(s) in another cluster(s)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tpa1 | 142 | LSU ribosomal protein L11P [ZP_04331932] | Nocardiopsis dassonvillei subsp. dassonvillei DSM 43111 | 92/97 | 50S ribosomal protein L11 | |

| tpa2 | 225 | LSU ribosomal protein L1P [ZP_04331931] | Nocardiopsis dassonvillei subsp. dassonvillei DSM 43111 | 89/95 | 50S ribosomal protein L1 | |

| tpa3 | 175 | LSU ribosomal protein L10P [ZP_04331927] | Nocardiopsis dassonvillei subsp. dassonvillei DSM 43111 | 91/96 | 50S ribosomal protein L10 | |

| tpa4 | 129 | 50S ribosomal protein L7/L12 [YP_290711] | Thermobifida fusca YX | 83/89 | 50S ribosomal protein L7/L12 | |

| tpa5 | 1,155 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit β [ZP_04331925] | Nocardiopsis dassonvillei subsp. dassonvillei DSM 43111 | 96/98 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit β | |

| tpa6 | 1,292 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit β′ [YP_290709] | Thermobifida fusca YX | 87/94 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit β′ | |

| tpa9 | 1,060 | Hypothetical protein NdasDRAFT_0999 [ZP_04331921] | Nocardiopsis dassonvillei subsp. dassonvillei DSM 43111 | 51/58 | Unknown | |

| tpaA | 48 | TP-1161 precursor peptide | ||||

| tpaB | 355 | Hypothetical protein PPA0861 [YP_055574] | Propionibacterium acnes KPA171202 | 27/44 | Unknown | NocC [ADH93701]; NosO [ACR48344]; SioL [ACN80649]; TsrE/TsrL [ACN52295]/[ACN80674] |

| tpaC | 448 | NosG [ACR48336] | Streptomyces actuosus | 29/41 | Cyclodehydratase | NosG [ACR48336] |

| tpaD | 200 | Hypothetical protein PPA0864 [YP_055576.1] | Propionibacterium acnes KPA171202 | 33/50 | Cyclodehydratase | TruD [ACA04490] |

| tpaE | 546 | Cyclodehydratase domain protein [ZP_06427466] | Propionibacterium acnes SK187 | 35/51 | Thiazoline/oxazoline dehydrogenase | SioM [ACN80650]; TsrF/TsrM [ACN52296]/[ACN80675] |

| tpaF | 233 | Conserved hypothetical protein [ZP_06427458.1] | Propionibacterium acnes SK187 | 39/54 | Thiazoline/oxazoline dehydrogenase | |

| tpaG | 604 | NosH [ACR48337] | Streptomyces actuosus | 30/40 | Unknown | NosH [ACR48337]; TsrG/TsrN [ACN52297]/[ACN80676] |

| tpaH | 621 | NosG [ACR48336] | Streptomyces actuosus | 37/48 | Cyclodehydratase/peptidase | NosG [ACR48336]; SioO [ACN80652]; TsrH/TsrO [ACN522298]/[ACN80677]; TruD [ACA04490] |

| tpaI | 269 | Thiostrepton resistance methyltransferase [3GYQ_A] | Streptomyces cyaneus | 66/84 | 23S rRNA methyltransferase | |

| tpaJ | 404 | 4-Hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase [ZP_06685097] | Achromobacter piechaudii ATCC 43553 | 25/44 | Dehydrogenase | |

| tpaX | 48 | Precursor peptide for unknown thiopeptide | ||||

| tpaK | 929 | Putative lanthionine biosynthesis protein [YP_055572] | Propionibacterium acnes KPA171202 | 34/51 | Dehydratase | NosE [ACR48334]; SioJ [ACN80647]; TsrC/TsrJ [ACN52293]/[ACN80672]; SioS [ACN80656]; TsrL [ACN80681]; TsrS [ACN52302] |

| tpaL | 290 | Putative lanthionine biosynthesis protein [YP_055573] | Propionibacterium acnes KPA171202 | 34/50 | Dehydratase | NosD [ACR48333]; TsrD/TsrK [ACN52294]/[ACN80673]; SioK [ACN80648]; NisB [ACQ65769] |

| tpa8 | 123 | SSU ribosomal protein S12P [ZP_04331920] | Nocardiopsis dassonvillei subsp. dassonvillei DSM 43111 | 96/97 | 30S ribosomal protein S12P | |

| tpa9 | 156 | SSU ribosomal protein S7P [ZP_04331919] | Nocardiopsis dassonvillei subsp. dassonvillei DSM 43111 | 97/98 | 30S ribosomal protein S7P | |

| tpa10 | 703 | Translation elongation factor 2 (EF-2/EF-G) [ZP_04331918] | Nocardiopsis dassonvillei subsp. dassonvillei DSM 43111 | 92/96 | Elongation factor G (EF-G) | |

| tpa11 | 397 | Translation elongation factor 1A (EF-1A/EF-Tu) [04331917] | Nocardiopsis dassonvillei subsp. dassonvillei DSM 43111 | 95/98 | Elongation factor Tu (EF-Tu) |

NCBI accession numbers are given in square brackets. LSU, large subunit; SSU, small subunit.

Percent identity and percent similarity to the most homologous protein according to a BLAST search.

Homologs in clusters for thiopeptide and other tailored peptide clusters. NCBI accession numbers are given in square brackets.

Construction of Nocardiopsis sp. strain TFS65-07 cosmid library and screening for TP-1161 biosynthetic gene cluster.

A genomic cosmid library of Nocardiopsis sp. TFS65-07 was constructed using the Stratagene SuperCos1 cosmid vector kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. Genomic DNA of Nocardiopsis sp. TFS65-07 was prepared using the Kirby mix procedure (15), partially digested with MboI and ligated into the XbaI-, BamHI-, and calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (CIP)-treated SuperCos1 vector. E. coli XL1-Blue MR served as the host for constructing the genomic library. The library consisting of 3,072 clones was screened by colony hybridization by the method of Jørgensen et al. (13). A 385-bp fragment comprising the putative TP-1161 precursor peptide gene (146 bp) plus surrounding regions was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA from strain TFS65-07. The fragment was cloned into pDrive (Qiagen), and the target sequence was confirmed by DNA sequencing. The fragment was then labeled using the PCR DIG probe synthesis kit (Roche Applied Science) and used to screen the library for cosmids containing the putative TP-1161 biosynthetic gene cluster. Three cosmid clones were selected for further analysis, and end sequencing of the corresponding cosmids suggested the presence of the putative TP-1161 biosynthetic gene cluster in all three of the clones. Cosmid 8-B9 was used for further studies.

Gene inactivation experiments in Nocardiopsis sp. strain TFS65-07.

For genetic manipulation of strain TFS65-07, a gene transfer system in the form of intergeneric conjugation using E. coli S17.1 as the donor was established. The pK18mob-based (27) vector pKE5 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) was used for all gene inactivation experiments in strain TFS65-07. To construct plasmids for insertional mutagenesis, internal gene fragments of about 1 kb of the genes encoding putative cyclodehydratases (tpaC and tpaH) were amplified from genomic DNA using the specific primer pairs tpaCfwd/tpaCrev and tpaHfwd/tpaHrev (the forward primer is indicated by fwd at the end of the primer name, and the reverse primer is indicated by rev at the end of the primer name) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The obtained PCR products were cloned into pDrive (Qiagen) and confirmed by DNA sequencing using standard M13 primers. The constructs were then digested with SphI/HindIII and EcoRI/BamHI, and the gene fragments were ligated into the corresponding sites of pKE5, yielding pKE24 and pKE25. The constructs obtained were introduced into strain TFS65-07 by conjugation following standard procedures (15). Kanamycin-resistant exconjugants represented TSF65-07 mutants where the vector had integrated in the chromosome by a single crossover event. Chromosomal integration of the vectors at the target sites was confirmed by Southern blot analysis.

tpaJ in-frame deletion.

In-frame deletion of tpaJ in cosmid 8-B9 was created by λ-Red-mediated recombination as described previously (7, 11) yielding cosmid 8-B9ΔtpaJ. The DELtpaJ_fwd and DELtpaJ_rev primers (DEL stands for deletion) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) were used to amplify the pIJ782 disruption cassette, consisting of oriT (RK2) and a tetracycline resistance gene flanked by FRT (FLP recognition target) sites, by PCR (underlined sequence in primers consists of 39-nucleotide (nt) homology regions upstream and downstream of tpaJ). The extended disruption cassette was used to replace tpaJ in cosmid 8-B9. Via FLP-mediated excision of the introduced disruption cassette, an unmarked in-frame deletion was achieved, leaving behind a 81-bp “scar” sequence devoid of stop codons in the preferred reading frame (11). A 7.3-kb NotI fragment covering tpaE′-tpaK′ and containing the tpaJ in-frame deletion was then subcloned into pDrive, digested with EcoRI, and ligated into the corresponding restriction site of pKE5. The obtained construct, pKE27, was introduced into strain TFS65-07 by intergeneric conjugation as described above. Kanamycin-resistant exconjugants where the vector had inserted via a single crossover event were confirmed by Southern blot analysis. To allow for a second crossover event and excision of the vector, confirmed single-crossover mutants were subjected to two rounds of sporulation under nonselective growth conditions. Via replica plating, the Kms colonies were identified and colony PCR using the Ver_fwd and Ver_rev primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) followed by Southern blot analysis were used to identify the tpaJ deletion mutants.

Analysis of Nocardiopsis sp. strain TFS65-07 mutants for production of TP-1161 and its congeners.

Mutant strains of Nocardiopsis sp. strain TFS65-07 obtained from insertional mutagenesis and gene deletion experiments were grown on 0.75× ISP2 agar (Difco) (supplemented when necessary with 50 μg/ml kanamycin) until sporulated. Spores were used to inoculate 25 ml of seed medium (ISP2) in 250-ml baffled flasks. Seed cultures were incubated for 2 to 5 days at 25°C and 225 rpm until dense growth was observed. Two milliliters of this seed culture was used to inoculate 100 ml of PM4 fermentation medium in 500-ml baffled flasks. Both seed and fermentation cultures contained glass beads (3-mm diameter) to avoid excessive formation of mycelial pellets. Fermentation cultures were incubated at 25°C and 225 rpm for 7 to 10 days. One to 5 ml of fermentation cultures were used for extraction with the same volume of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). After centrifugation (2,600 × g, 5 min), the pelleted mycelium was washed once with the same volume of sterile, deionized water and extracted with DMSO for 2 h at room temperature. Cell extracts were obtained by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 10 min) and stored at −20°C. For detection of production of TP-1161 and its congeners, the LC-DAD-TOF analyses (analyses where a liquid chromatograph [LC] was connected to a diode array detector [DAD] and time of flight [TOF] apparatus) were performed as described previously (9).

Attempted heterologous expression of TP-1161 biosynthetic gene cluster in S. coelicolor M512.

For heterologous expression of the TP-1161 biosynthetic gene cluster, cosmid 8-B9 was modified using λ-Red-mediated recombination introducing the integrase gene (int) and the attachment site (attP) of phage ΦC31 into the cosmid backbone by the method of Eustáquio et al. (10). The DraI-BsaI fragment with integrase cassette of pIJ787 was used to replace the bla gene in the SuperCos1 backbone of cosmid 8-B9, generating 8-B9_int. After passage through methylation-deficient E. coli C2529 cells, the obtained unmethylated construct was introduced into S. coelicolor M512 by polyethylene glycol (PEG)-mediated protoplast transformation (15). Site-specific integration of the cosmids into the S. coelicolor M512 chromosome was confirmed by Southern blot analysis of kanamycin-resistant recombinants.

Analysis of S. coelicolor M512 recombinants for TP-1161 production.

To analyze the S. coelicolor M512/8-B9 recombinants for the TP-1161 production, a range of fermentation media and cultivation conditions were used. Cultivations were performed in microwell plates as described previously (9) using 0.3× F134 (22), PM4, and seven additional media composed of components of either PM4 or 0.3× F134 medium (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The wild-type TP-1161 producer Nocardiopsis sp. strain TFS65-07, the parental S. coelicolor M512 strain, and S. coelicolor M145 were used as control strains. Seed cultures of all strains were prepared in 250-ml baffled flasks containing 50 ml of 2× YT medium (15) which was inoculated from frozen cell suspensions. Cultivations were performed at 30°C and 225 rpm until dense growth could be observed. If necessary, the mycelium of seed cultures was harvested, fragmented mechanically, and reinoculated in fresh medium several times during cultivation to obtain homogenous inoculums. The obtained seed cultures were used to inoculate the fermentation medium (3% in 800 μl fermentation medium). Fermentations were performed at 800 rpm and 85% humidity for 6 days at 30°C (S. coelicolor strains) or 14 days at 25°C (strain TSF65-07). Entire fermentation cultures were freeze-dried and extracted with DMSO (400 μl), and the extracts were analyzed for the presence of TP-1161 by LC-DAD-TOF as described previously (9).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of the gene cluster surrounding the TP-1161 precursor peptide gene was submitted to GenBank and can be retrieved under accession number HM467197.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Genome mining for the TP-1161 biosynthetic gene cluster.

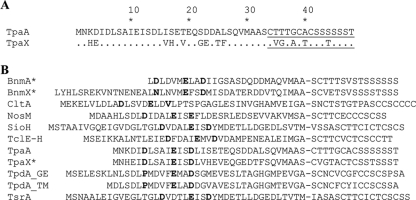

To isolate the biosynthetic gene cluster for thiopeptide antibiotic TP-1161, the predicted TP-1161 precursor peptide sequence was used to mine the draft genome sequence obtained for the producer strain, Nocardiopsis sp. strain TFS65-07. A 147-bp-long open reading frame encoding the putative 48-amino-acid (aa) TP-1161 precursor peptide (designated TpaA) was identified. The tpaA product consisted of the 33-aa N-terminal leader peptide followed by the 15-aa structural peptide (Fig. 2 A). The structural peptide sequence was found to be in agreement with the posttranslationally modified TP-1161 backbone except for the C-terminal threonine (Fig. 1), which was present in the structural peptide, but not in the mature TP-1161 molecule.

FIG. 2.

(A) Alignment of two thiopeptide precursor peptides, TpaA and TpaX, encoded by the genomic locus for TP-1161 biosynthesis (the structural peptide of TP-1161 and suggested structural peptide for unknown thiopeptide are underlined). Residues in TpaX that are identical to those in TpaA are indicated by periods. Residues in TpaX that are different from those in TpaA are shown. (B) Conserved residues in leader peptides of 11 thiopeptide precursors. The leader peptides in thiopeptide precursors berninamycin (BnmA*), an unknown thiopeptide (BnmX*), cyclothiazomycin (CltA), nosiheptide (NosM), siomycin (SioH), thiocillin (TclE-H), TP-1161 (TpaA), an unknown thiopeptide (TpaX*), thiomuracins (TpdA_TM), GE2270A (TpdA_GE), and thiostrepton (TsrA) are shown. Putative thiopeptide precursors are indicated by an asterisk. (The C-terminal structural peptides are separated by a dash). Conserved residues are displayed in boldface type.

While no overall sequence homology could be detected between leader sequences of different thiopeptides, the leader sequences were found to be rich in acidic amino acids, and it was suggested that glutamic and aspartic acid residues might play important roles in substrate recognition by posttranslational modification enzymes (32). An alignment of 11 (putative) precursor peptide sequences (Fig. 2B), revealed a conserved motif consisting of glutamic and aspartic acid residues (DXXXXEXXD). Two out of the three conserved residues can be found in all leader peptide sequences included in the alignment, indicating the possible importance of these residues for recognition by the maturation enzymes.

Bioinformatics analysis of the TP-1161 gene cluster and functional confirmation of the TP-1161 biosynthetic locus.

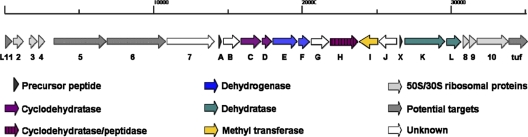

Bioinformatics analysis of the genomic region surrounding tpaA revealed 12 downstream open reading frames (ORFs) (designated tpaB to tpaL) proposed to encode enzymes for posttranslational modification of TpaA and self-resistance (Fig. 3 and Table 1). Enzymes mediating heterocyclization and dehydration of amino acid side chains in thiopeptide biosynthesis usually appear as a set of moderately conserved proteins, with relatively low similarity values (typically around 50%) between homologs (16). Many of these proteins also have homologs in biosynthetic pathways for other tailored ribosomal peptides, including the lantibiotics (30), cyanobactins (8), goadsporin (23), and microcin B17 (31).

FIG. 3.

Organization of the TP-1161 biosynthetic gene cluster in Nocardiopsis sp. strain TFS65-07. The proposed core biosynthetic genes with deduced functions and surrounding regions are displayed. The size of the genomic region in kilobases is indicated at the top of the figure.

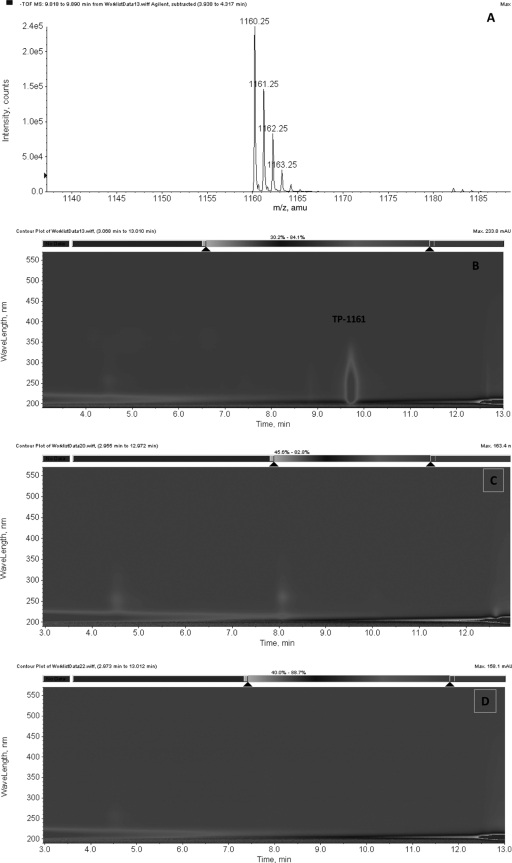

To verify that the assigned genomic region was indeed governing the biosynthesis of thiopeptide antibiotic TP-1161, two genes (tpaC and tpaH) encoding putative cyclodehydratases were chosen as targets for gene disruption experiments. Inactivation was accomplished through gene disruption by introducing suicide plasmids carrying internal fragments of the respective genes into Nocardiopsis sp. strain TFS65-07 via intergeneric conjugation. As expected, the inactivation of the two proposed cyclodehydratase-encoding genes resulted in complete loss of TP-1161 production, thus verifying the involvement of the proteins encoded by the genes in the biosynthesis of TP-1161 (Fig. 4). Complementation of tpaC and tpaH mutants were not attempted, since we did not possess replicating vectors for this species or suitable selective markers except for apramycin, which has already been used in the gene disruption constructs. From the organization of the genes, we can safely assume that at least in the case of tpaH, the observed loss of TP-1161 production was not due to a polar effect.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of the fermentation extracts of the TP-1161 wild-type producer Nocardiopsis sp. strain TFS65-07 and TP-1161 production gene disruption mutants. (A and B) TOF MS spectrum (A) and LC-DAD isoplot (B) of wild-type strain TSF65-07 extract; (C and D) LC-DAD isoplots of tpaC and tpaH disruption mutants. amu, atomic mass units; mAU, milli absorbance units.

Uncommon paralogs for conserved thiopeptide modification enzymes.

The characteristic thiazole and (methyl)oxazole heterocycles appear in thiopeptides due to the cyclodehydration of serine, cysteine, and threonine residues, where the side chains of these amino acids are cyclized against the preceding carbonyl groups, yielding dehydroheterocycles. Subsequent oxidation can convert the resulting thiazoline and oxazoline groups to their aromatic forms (25). Cyclodehydratases and dehydrogenases commonly appear as a set of two genes in thiopeptide clusters encoding relatively conserved enzymes (16). However, functional assignment of the genes constituting the proposed biosynthetic locus for thiopeptide antibiotic TP-1161 indicated the presence of three predicted cyclodehydratases (tpaC, tpaD, and tpaH) (Table 1). The two enzymes, TpaE and TpaF, showed homology to the flavin mononucleotide (FMN)-dependent McbC-like oxidoreductases, which suggests that they may be possible candidate enzymes mediating thiazoline/oxazoline oxidation and thus yielding the thiazole and (methyl)oxazole groups present in TP-1161 (Fig. 1). Paralogous genes encoding additional cyclodehydratases and dehydratases have so far only been described for the GE2270A biosynthetic locus, where the paralogs are assumed to be involved in modification of the side chain attached to the pyridine-6-position introducing the C-terminal oxazoline (21). The proposed TP-1161 biosynthetic gene cluster contains a total of five genes encoding enzymes which can be associated with polyazole formation through heterocyclization (tpaC, tpaD, and tpaH) of serine, cysteine, and threonine residues in TpaA followed by oxidation (tpaE and tpaF) (Fig. 3 and 5 A).

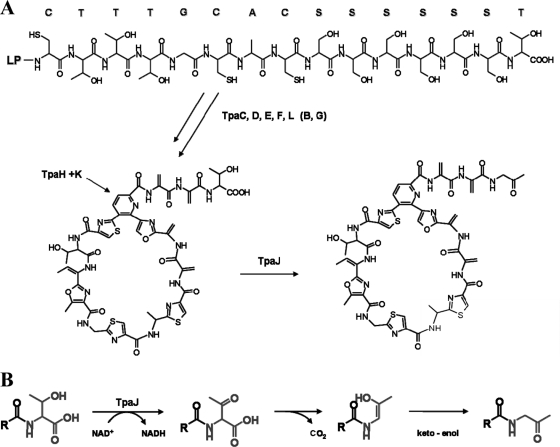

FIG. 5.

(A) Proposed pathway for TP-1161 biosynthesis. LP, leader peptide. (B) Proposed generation of TP-1161 amino acetone terminus from threonine via oxidative action of TpaJ.

Dehydrations of serine and threonine residues yielding dehydroalanine and dehydrobutyrine groups in thiopeptides are mediated by enzymes resembling LanB-type lantibiotic dehydratases, and typically there are at least two homologs present in thiopeptide clusters (16). TpaK and TpaL share 34% similarity with lanthionine biosynthesis proteins (Table 1) and are therefore predicted to be involved in amino acid dehydration and formation of the four dehydroalanine groups and single dehydrobutyrine group present in TP-1161 (Fig. 5A).

The proposed TP-1161 cluster contains a second precursor peptide gene.

Annotation of the predicted TP-1161 biosynthetic gene cluster also identified a second putative thiopeptide precursor gene (tpaX) located about 12 kb downstream of tpaA (Fig. 3). Both peptides encoded by these two genes have the same length (48 aa) and share 70% identity on amino acid level (Fig. 2A). However, attempts to detect the mature product of tpaX in Nocardiopsis sp. strain TFS65-07 TFS65-07 fermentation extracts have been unsuccessful. Multiple copies of thiopeptide precursor genes have been reported, for example, for the thiocillins, where the thiocillin biosynthetic gene cluster contains four identical copies of precursor peptides genes (4). The functions of these tandem genes are not clear, but Acker et al. demonstrated that only one plasmid-based gene copy introduced into a mutant with all four genes for precursor peptide deleted was sufficient to restore thiocillin biosynthesis (1). Also, the proposed berninamycin cluster in the genome of Propionibacterium acnes KPA171202, which was identified in a bioinformatics search for thiazolyl peptide-encoding genes by Wieland Brown et al. (29), contains two genes encoding distinct putative precursor peptides. One of these genes is predicted to encode a 47-aa precursor peptide with the 15-aa berninamycin structural peptide (SCTTTSVSTSSSSSS) at its N terminus (29), whereas the second 58-residue precursor peptide (SCVETSVSSSSTSSS) differs in four positions from the structural peptide of berninamycin (the four different amino acids are underlined). However, a mature product for the second precursor has not been reported so far.

Proposed pathway for the macrocyclization of TP-1161 precursor.

The exact mechanisms of macrocyclization and formation of the central 6-membered nitrogen-containing heterocycle in thiopeptides have not been experimentally verified yet. The currently promoted hypothesis involves cycloaddition of three precursor amino acids, identified by feeding studies as two serines and the carboxyl group of one cysteine residue (19, 20), yielding a dehydropiperidine intermediate (16). According to a mechanism proposed by Bycroft and Gowland on the constitution of the pyridine ring in micrococcins P1 and P2, cyclization of these three residues requires dehydration of the two serine residues (5). The pyridine ring of series d thiopeptides could then be obtained via dehydration of the resulting dehydropiperidine moiety (16).

On the basis of the conducted homology searches, TpaH is proposed to represent a cyclodehydratase involved in the intramolecular cyclization of TP-1161 precursor (Table 1). In addition to the characteristic YcaO family domain (residues 235 to 579), a signature of a putative serine peptidase domain (residues 235 to 579) was found at the TpaH C terminus, indicating a possible function of this protein in both macrocyclization and leader peptide cleavage. TpaH-mediated cyclodehydration of the N-terminal cysteine residue could provide the carboxyl group necessary for the formation of the dehydropyridine intermediate. Dehydration of two serine residues by a putative dehydratase TpaK and cycloaddition of the resulting dehydroalanine groups with the cysteine-derived carboxyl are presumably coupled to the elimination of the leader peptide and could yield the dehydropiperidine intermediate.

While the insertional inactivation of tpaH proved the involvement of TpaH in TP-1161 biosynthesis, the results of this experiment did not allow any evaluation of the above-mentioned hypothesis on macrocyclization and leader peptide cleavage, since the knockout mutant did not produce any metabolites that could be linked to the TP-1161 biosynthetic gene cluster.

TP-1161 putative mode of action and host resistance.

In addition to the genes encoding enzymes for posttranslational modification, the TP-1161 cluster also contained a predicted 23S rRNA methyltransferase (TpaI) with high sequence homology (66% identity) to the methyltransferase of Streptomyces azureus conferring resistance to the thiopeptide antibiotic thiostrepton (28). Thus, TpaI most likely provides for the self-resistance to TP-1161 in the producer Nocardiopsis sp. strain TFS65-07.

The core biosynthetic genes (tpaA to tpaL) are flanked by various genes encoding 50S and 30S ribosomal proteins (Fig. 3 and Table 1). Notable here is the presence of the 50S ribosomal protein L11 (tpa1) in close proximity to the biosynthetic genes, which suggests that L11 may be a molecular target for TP-1161 action. Sequence analysis of the tpa1-encoded L11 protein revealed mutations in both conserved residues located within the putative thiopeptide (thiostrepton) binding site (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), further strengthening this hypothesis, since mutations of these key amino acids in the N-terminal domain of L11 have previously been shown to confer thiostrepton resistance (6). Other genes encoding potential thiopeptide targets were also found in the immediate surroundings of the cluster, including the bacterial elongation factor Tu (EF-Tu, encoded by tpa11). Producers of the EF-Tu-targeting thiopeptides, such as the thiomuracins and GE2270A, avoid self-intoxication through nucleotide exchanges in their EF-Tu-encoding tuf genes causing replacement of glycine 275 (E. coli numbering) (21). However, no such mutations could be identified in the tpa11 gene, thus leaving open the question of whether EF-Tu is a target for TP-1161.

Modification of the TP-1161 C-terminal tail.

The termini of most thiopeptide tails are represented by carboxyamide or carboxyl groups. TP-1161, however, possesses an unusual terminal aminoacetone moiety which, according to the structural peptide sequence, is derived from threonine. TpaJ exhibits sequence similarity with iron-containing alcohol dehydrogenases, in particular with 4-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenases, and could be a possible candidate for tailoring the TP-1161 terminus. 4-Hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenases catalyze oxidation of the 4-hydroxybutanoic acid to succinate semialdehyde. Structural similarity between 4-hydroxybutanoic acid and threonine indicates a possible involvement of TpaJ in oxidation of the terminal threonine residue. Oxidation of threonine followed by spontaneous decarboxylation and tautomerization of the resulting keto-to-enol form could then yield aminoacetone (Fig. 5B). To investigate this hypothesis, an in-frame deletion mutant of tpaJ was constructed and analyzed for the production of the presumed TP-1161 derivative with C-terminal threonine. However, fermentation extract analyses proved a complete loss of TP-1161 production, and no derivatives related to TP-1161 could be detected by a thorough mass spectrometry (MS) scan (data not shown).

Cloning and heterologous expression of the TP-1161 gene cluster.

To establish a versatile platform for genetic manipulation and functional analysis of the TP-1161 maturation machinery, the TP-1161 cluster was isolated from a genomic cosmid library of Nocardiopsis sp. strain TFS65-07, and heterologous expression of the cluster in S. coelicolor M512 was attempted. The cosmid library of strain TFS65-07 was probed with a PCR-amplified genomic fragment comprising the TP-1161 precursor peptide gene and surrounding regions. End sequencing of cosmid 8-B9 identified in such screen confirmed the presence of the entire proposed TP-1161 biosynthetic gene cluster plus surrounding regions (Fig. 3) on this cosmid, which was used for further work.

For site-specific integration of the TP-1161 gene cluster into the chromosome of S. coelicolor M512, the SuperCos1 backbone of cosmid 8-B9 was modified by λ-Red-mediated recombination introducing the integrase gene (int) and the attachment site (attP) of phage ΦC31. Site-specific integration of 8-B9_int was verified by Southern blot analysis of the kanamycin-resistant M512 clones. However, none of the confirmed integration mutants produced TP-1161 under conditions tested (data not shown). To analyze whether this result was due to a general lack of expression of genes in the TP-1161 cluster, both the parental and recombinant strains of M512 were tested for growth on agar medium supplemented with thiostrepton. While the parental M512 strain was found to be sensitive to thiostrepton, the recombinant strains were resistant to thiostrepton, indicating that expression of the tpaI-encoded 23S rRNA methyltransferase conferred this phenotype. The reasons for the lack of TP-1161 production in the recombinants are not known, and gene expression studies in both original and heterologous hosts designed to address this question are under way.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Michael Kemmler for suggestions on the mechanism of aminoacetone group formation, to Mervyn Bibb for kindly providing S. coelicolor M512, and to Håvard Sletta for help with design of the fermentation experiments.

This work was supported by the Norwegian University of Science and Technology and the Research Council of Norway.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 September 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acker, M. G., A. A. Bowers, and C. T. Walsh. 2009. Generation of thiocillin variants by prepeptide gene replacement and in vivo processing by Bacillus cereus. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131:17563-17565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagley, M. C., J. W. Dale, E. A. Merritt, and X. Xiong. 2005. Thiopeptide antibiotics. Chem. Rev. 105:685-714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhat, U. G., M. Halasi, and A. L. Gartel. 2009. Thiazole antibiotics target FoxM1 and induce apoptosis in human cancer cells. PLoS One 4:e5592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bower, J., M. Drysdale, R. Hebdon, A. Jordan, G. Lentzen, N. Matassova, A. Murchie, J. Powles, and S. Roughley. 2003. Structure-based design of agents targeting the bacterial ribosome. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 13:2455-2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bycroft, B. W., and M. S. Gowland. 1978. Structures of the highly modified peptide antibiotics micrococcin P1 and P2. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1978:256-258. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cameron, D. M., J. Thompson, S. T. Gregory, P. E. March, and A. E. Dahlberg. 2004. Thiostrepton-resistant mutants of Thermus thermophilus. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:3220-3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donia, M. S., J. Ravel, and E. W. Schmidt. 2008. A global assembly line for cyanobactins. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4:341-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engelhardt, K., K. F. Degnes, M. Kemmler, H. Bredholt, E. Fjaervik, G. Klinkenberg, H. Sletta, T. E. Ellingsen, and S. B. Zotchev. 2010. Production of a new thiopeptide antibiotic, TP-1161, by a marine Nocardiopsis species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:4969-4976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eustáquio, A. S., B. Gust, U. Galm, S. M. Li, K. F. Chater, and L. Heide. 2005. Heterologous expression of novobiocin and clorobiocin biosynthetic gene clusters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:2452-2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gust, B., G. L. Challis, K. Fowler, T. Kieser, and K. F. Chater. 2003. PCR-targeted Streptomyces gene replacement identifies a protein domain needed for biosynthesis of the sesquiterpene soil odor geosmin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:1541-1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hashimoto, M., T. Murakami, K. Funahashi, T. Tokunaga, K.-I. Nihei, T. Okuno, T. Kimura, H. Naoki, and H. Himeno. 2006. An RNA polymerase inhibitor, cyclothiazomycin B1, and its isomer. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 14:8259-8270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jørgensen, H., K. F. Degnes, H. Sletta, E. Fjærvik, A. Dikiy, L. Herfindal, P. Bruheim, G. Klinkenberg, H. Bredholt, G. Nygård, S. O. Døskeland, T. E. Ellingsen, and S. B. Zotchev. 2009. Biosynthesis of macrolactam BE-14106 involves two distinct PKS systems and amino acid processing enzymes for generation of the aminoacyl starter unit. Chem. Biol. 16:1109-1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelly, W. L., L. Pan, and C. Li. 2009. Thiostrepton biosynthesis: prototype for a new family of bacteriocins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131:4327-4334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kieser, T., M. J. Bibb, M. J. Buttner, K. F. Chater, and D. A. Hopwood. 2000. Practical Streptomyces genetics. John Innes Foundation, Norwich, United Kingdom.

- 16.Li, C., and W. L. Kelly. 2010. Recent advances in thiopeptide antibiotic biosynthesis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 27:153-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liao, R., L. Duan, C. Lei, H. Pan, Y. Ding, Q. Zhang, D. Chen, B. Shen, Y. Yu, and W. Liu. 2009. Thiopeptide biosynthesis featuring ribosomally synthesized precursor peptides and conserved posttranslational modifications. Chem. Biol. 16:141-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McConkey, G. A., M. J. Rogers, and T. F. McCutchan. 1997. Inhibition of Plasmodium falciparum protein synthesis. Targeting the plastid-like organelle with thiostrepton. J. Biol. Chem. 272:2046-2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mocek, U., A. R. Knaggs, R. Tsuchiya, T. Nguyen, J. M. Beale, and H. G. Floss. 1993. Biosynthesis of the modified peptide antibiotic nosiheptide in Streptomyces actuosus. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115:7557-7568. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mocek, U., Z. Zeng, D. O'Hagan, P. Zhou, L. D. G. Fan, J. M. Beale, and H. G. Floss. 1993. Biosynthesis of the modified peptide antibiotic thiostrepton in Streptomyces azureus and Streptomyces laurentii. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115:7992-8001. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morris, R. P., J. A. Leeds, H. U. Naegeli, L. Oberer, K. Memmert, E. Weber, M. J. LaMarche, C. N. Parker, N. Burrer, S. Esterow, A. E. Hein, E. K. Schmitt, and P. Krastel. 2009. Ribosomally synthesized thiopeptide antibiotics targeting elongation factor Tu. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131:5946-5955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nieselt, K., F. Battke, A. Herbig, P. Bruheim, A. Wentzel, O. Jakobsen, H. Sletta, M. Alam, M. Merlo, J. Moore, W. Omara, E. Morrissey, M. Juarez-Hermosillo, A. Rodriguez-Garcia, M. Nentwich, L. Thomas, M. Iqbal, R. Legaie, W. Gaze, G. Challis, R. Jansen, L. Dijkhuizen, D. Rand, D. Wild, M. Bonin, J. Reuther, W. Wohlleben, M. Smith, N. Burroughs, J. Martin, D. Hodgson, E. Takano, R. Breitling, T. Ellingsen, and E. Wellington. 2010. The dynamic architecture of the metabolic switch in Streptomyces coelicolor. BMC Genomics 11:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Onaka, H., M. Nakaho, K. Hayashi, Y. Igarashi, and T. Furumai. 2005. Cloning and characterization of the goadsporin biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptomyces sp. TP-A0584. Microbiology 151:3923-3933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogers, M. J., E. Cundliffe, and T. F. McCutchan. 1998. The antibiotic micrococcin is a potent inhibitor of growth and protein synthesis in the malaria parasite. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:715-716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roy, R. S., A. M. Gehring, J. C. Milne, P. J. Belshaw, and C. T. Walsh. 1999. Thiazole and oxazole peptides: biosynthesis and molecular machinery. Nat. Prod. Rep. 16:249-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 27.Schäfer, A., A. Tauch, W. Jäger, J. Kalinowski, G. Thierbach, and A. Pühler. 1994. Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145:69-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thompson, J., F. Schmidt, and E. Cundliffe. 1982. Site of action of a ribosomal RNA methylase conferring resistance to thiostrepton. J. Biol. Chem. 257:7915-7917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wieland Brown, L. C., M. G. Acker, J. Clardy, C. T. Walsh, and M. A. Fischbach. 2009. Thirteen posttranslational modifications convert a 14-residue peptide into the antibiotic thiocillin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:2549-2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xie, L., and W. A. van der Donk. 2004. Post-translational modifications during lantibiotic biosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 8:498-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yorgey, P., J. Lee, J. Kördel, E. Vivas, P. Warner, D. Jebaratnam, and R. Kolter. 1994. Posttranslational modifications in microcin B17 define an additional class of DNA gyrase inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91:4519-4523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu, Y., L. Duan, Q. Zhang, R. Liao, Y. Ding, H. Pan, E. Wendt-Pienkowski, G. Tang, B. Shen, and W. Liu. 2009. Nosiheptide biosynthesis featuring a unique indole side ring formation on the characteristic thiopeptide framework. ACS Chem. Biol. 4:855-864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.