Abstract

Fimbriae of the human uropathogen Proteus mirabilis are the only characterized surface proteins that contribute to its virulence by mediating adhesion and invasion of the uroepithelia. PMI2122 (AipA) and PMI2575 (TaaP) are annotated in the genome of strain HI4320 as trimeric autotransporters with “adhesin-like” and “agglutinating adhesin-like” properties, respectively. The C-terminal 62 amino acids (aa) in AipA and 76 aa in TaaP are homologous to the translocator domains of YadA from Yersinia enterocolitica and Hia from Haemophilus influenzae. Comparative protein modeling using the Hia three-dimensional structure as a template predicted that each of these domains would contain four antiparallel beta sheets and that they formed homotrimers. Recombinant AipA and TaaP were seen as ∼28 kDa and ∼78 kDa, respectively, in Escherichia coli, and each also formed high-molecular-weight homotrimers, thus supporting this model. E. coli synthesizing AipA or TaaP bound to extracellular matrix proteins with a 10- to 60-fold-higher level of affinity than the control strain. Inactivation of aipA in P. mirabilis strains significantly (P < 0.01) reduced the mutants' ability to adhere to or invade HEK293 cell monolayers, and the functions were restored upon complementation. A 51-aa-long invasin region in the AipA passenger domain was required for this function. E. coli expressing TaaP mediated autoagglutination, and a taaP mutant of P. mirabilis showed significantly (P < 0.05) more reduced aggregation than HI4320. Gly-247 in AipA and Gly-708 in TaaP were indispensable for trimerization and activity. AipA and TaaP individually offered advantages to P. mirabilis in a murine model. This is the first report characterizing trimeric autotransporters in P. mirabilis as afimbrial surface adhesins and autoagglutinins.

Adherence of pathogenic bacteria to host cells represents the defining step in establishing an infection. Subsequent events include colonization of tissues, and in certain cases, cellular invasion, followed by intracellular multiplication or persistence. The process of adherence is initiated when surface structures known as adhesins bind to specific ligands on host cells or to extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins. Autotransporters (ATs) are the most recently discovered surface proteins specific to Gram-negative pathogenic bacteria (17). These are modular proteins with three domains, each with a distinct function: a longer-than-usual signal sequence to facilitate transport across the inner membrane, an N-terminal (30- to 200-kDa) passenger or alpha (α) domain that governs the function of the AT, and the C-terminal (∼30-kDa) hydrophobic translocator that forms a beta barrel in the outer membrane to transport the passenger domain to the exterior. The translocator is often preceded by a short α-linker or autochaperone region (11, 17, 19). ATs often play significant roles in the pathogenesis of an infection by mediating diverse functions such as promoting bacterial adhesion to the host cell or to ECM proteins, host cell invasion, cytotoxicity, serum resistance, and autoaggregation (18, 48).

Trimeric autotransporters (AT-2s) are a subfamily of ATs that share similar protein architectures, with the exception of having a much shorter beta domain, which is not preceded by an α-helical region. Unlike a canonical C terminus (pfam03797) of a conventional AT, the C terminus of an AT-2 forms a stable trimeric structure (pfam03895) through linkage of the translocator domains from three individual proteins to form the beta barrel in the outer membrane (9). The three alpha domains on the exterior of the cell, in turn, assemble to form an adhesive pocket or cleft essential for the function of the protein. The YadA adhesin in Yersinia pestis and Hia adhesin in Haemophilus influenzae are considered prototypes for the AT-2 subfamily (5, 40, 51). Proteins with similar characteristics are now known to be part of many Gram-negative pathogens (10, 44, 58). These proteins either contribute directly to the virulence of the pathogen or offer advantage to its persistence in the host by mediating single or multiple functions as conventional ATs, but no cytotoxic AT-2s are known (10). The discovery and characterization of autotransporters in Gram-negative pathogens continue to provide new insight not only on the diverse functions of these proteins but also on the various modes of the pathogen's interaction with the host that would otherwise remain unknown.

Proteus mirabilis, a member of the Enterobacteriaceae, is a motile, urea-hydrolyzing, opportunistic pathogen of the human urinary tract that infects patients with indwelling urinary catheters or with postoperative wound infections (50). The hallmarks of P. mirabilis infection include the formation of calcium- and magnesium-rich stones in the bladder and kidney mediated by urease-catalyzed urea hydrolysis (23) and stable and persistent biofilms formed by various fimbriae (39, 43). Extensive research in the last two decades has identified a significant role for fimbriae in the pathogenesis of P. mirabilis. They aid in the process of infection by mediating adhesion, aggregation, hemagglutination, or motility in vivo (39). Their use in developing subunit vaccines against P. mirabilis has also been explored (45, 46); however, phase variation of certain fimbriae requires that they be used only in conjunction with other proteins as part of a multivalent vaccine (26, 59). Thus, identifying nonfimbrial surface proteins that contribute to the pathogen's persistence in vivo is critical. The genome sequence of the clinical isolate P. mirabilis HI4320 predicts six potential ATs, three of which are conventional ATs with protease-like domains and three of which belong to the AT-2 subfamily (36). ATs are often associated with virulence; hence, characterization of the trimeric form of autotransporters in P. mirabilis may provide useful insights on this bacterium's ability to persist in the host.

In this report, we characterized two of the putative ATs, PMI2122 and PMI2575, in P. mirabilis strain HI4320. We demonstrated that these proteins belong to the AT-2 subfamily of autotransporters and form stable trimeric structures in the outer membrane of the bacterium. Based on the functions they mediated, PMI2122 was designated AipA for adhesion and invasion mediated by the Proteus autotransporter, and PMI2575 was called TaaP for trimeric autoagglutinin autotransporter of Proteus. In vivo coinfection studies in a mouse model of a Proteus infection indicated that AipA and TaaP independently offer advantage to the pathogen in the host. This is the first report establishing the roles for P. mirabilis ATs in host cell adhesion and invasion by P. mirabilis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and reagents.

All DNA manipulations were performed with E. coli strain Top10. Expression and “gain-of-function” studies were performed using E. coli strain BL21plysS. P. mirabilis strain HI4320, a human urinary tract isolate that is urease positive, motile, hemolytic, and fimbriated, or the P. mirabilis isogenic hpmA (nonhemolytic) strain ALM2012B was used in various assays (Table 1). Expression vector pET21A(+) was obtained from Novagen (San Diego, CA). All oligonucleotides used for PCRs were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). All restriction endonucleases and polymerases were purchased from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). Luria-Bertani broth (LB broth) or agar contained 5 g/liter and 0.5 g/liter of NaCl for E. coli and P. mirabilis, respectively. Media were supplemented with ampicillin ([Amp] 100 μg/ml), kanamycin ([Kan] 25 μg/ml), chloramphenicol ([Cam] 20 μg/ml), or tetracycline ([Tet] 15 μg/ml) as appropriate. Table 1 lists all the plasmids and strains used in this study.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids and strains used in this study

| Plasmid or strain | Features and application | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pSAP2022 | 842-bp coding region of the PMI2122 gene (aipA) cloned between the NdeI-XhoI sites of pET21A | This study |

| pSAP2025 | 2,225-bp coding region of the PMI2575 gene (taaP) cloned between the NdeI-XhoI sites of pET21A | This study |

| pSAP2035 | 842-bp coding region of the PMI2122 gene (aipA) cloned between the NcoI-BglII sites of pBAD/Myc-His A | This study |

| pSAP2045 | pET21A carrying aipA with the nucleotides encoding Gly-247 altered to His to encode AipA* [AipA(G247H)] | This study |

| pSAP2046 | pET21A carrying taaP with the nucleotides encoding Gly-708 altered to His to encode TaaPA* [AipA(G708H)] | This study |

| pSAP2047 | pET21A carrying aipA with in-frame deletion of 158 nt (120-273) corresponding to the invasin motif to encode AipAΔInv | This study |

| pSAP2048 | pACD4K (Sigma) carrying retargeted intron with taaP homologous sequencesa | This study |

| pSAP2050 | pACD4K (Sigma) carrying retargeted intron with aipA homologous sequencesb | This study |

| pSAP2057 | ∼2,330-bp fusion encoding Ptaα-AipAβ, cloned between NdeI-XhoI sites in pET21A | This study |

| pSAP2058 | ∼2,375-bp fusion encoding Ptaα-TaaPβ, cloned between NdeI-XhoI sites in pET21A | This study |

| Strains | ||

| E. coli BL21plysS | F−ompT gal dcm lon hsdSB(rB− mB−) λ(DE3) pLysS(Cmr) | Novagen |

| E. coli Top10 | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) ϕ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 nupG recA1 araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galE15 galK16 rpsL(Strr) endA1 λ− | Invitrogen |

| P. mirabilis HI4320 | P. mirabilis catheter-associated wild-type strain; tetracycline resistant | Clinical isolate |

| P. mirabilis ALM2012B | Insertionally inactivated hpmA with reprogrammed intron | 1 |

| P. mirabilis ALM2021 | taaP inactivated in HI4320 using pSAP2050 (taaP::kan) | This study |

| P. mirabilis ALM2022 | aipA inactivated in HI4320 using pSAP2048 (aipA::kan) | This study |

| P. mirabilis ALM2023 | aipA inactivated in ALM2012B using pSAP2050 (hpmAaipA::kan) | This study |

| P. mirabilis ALM2025 | ASLM2023 (hpmAaipA::kan) complemented with pSAP2035 (p-aipA) | This study |

The plasmid was used for insertional inactivation of taaP in P. mirabilis HI4320.

The plasmid was used for insertional inactivation of aipA in P. mirabilis HI4320 or HI4320 hpmA.

Statistical analyses.

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 5.03 for Windows; GraphPad Software, San Diego, California).

In silico analyses and protein homology modeling.

Amino acid sequences for AipA (PMI2122) and TaaP (PMI2575) were obtained from the genome sequence of P. mirabilis strain HI4320 as provided by the Sanger Institute (ftp.sanger.ac.uk/pub/pathogens/pm) and were analyzed by BLAST (www.ncbi.nih.gov./blast) to determine their identity with other known proteins. Signal peptide prediction was done using the SignalP 3.0 server (www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP). Amino acid residues that form the putative alpha and beta domains of the autotransporters were determined by a MOTIF search (http://motif.genome.jp). A preliminary prediction of the topology of beta domains (hydrophobic residues and the connecting hydrophilic loops) in the C terminus of the protein was made using PredictProtein (http://www.predictprotein.org). For homology modeling, the template structure was a model of a trimeric autotransporter of H. influenzae ([HIA] Protein Data Bank [PDB] code 2GR7) (31), which was derived by X-ray diffraction at 2.3 Å resolution and contains amino acid residues 992 to 1098. Multiple sequence alignments were produced with ClustalW (using the Gonnet 250 substitution matrix; gap open penalty = 10; gap extension penalty = 0.2; gap separation penalty = 4) (25). The secondary structure of the models was predicted by Jpred (8). Molecular Operating Environment [MOE] version 2008.2 software (Chemical Computing Group, Inc., Montreal, Quebec, Canada) was used to calculate quaternary structural models. In brief, MOE takes a sequence alignment and a template structure as input for comparative protein modeling. The coordinates of potentially homologous regions were copied to the model structure, while inserted areas and nonhomologous side chains were modeled by selecting reasonable structure fragments from a database. Stochastic energy minimization was applied to the models several times, and the best model was selected. Computation of surfaces and quality assessment was done with MOE and WHAT_CHECK (20).

Cloning of aipA, taaP, and their variants into overexpression vector pET21A.

DNA techniques were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (42). Coding sequences of aipA and taaP were independently amplified by primers AipAF-AipAR and TaaPF-TaaPR, respectively (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Each of the resulting PCR products was digested with the appropriate endonucleases and individually cloned downstream of the IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside)-inducible T7 promoter into the linearized expression vector pET21A to yield pSAP2022 (pET-aipA) and pSAP2025 (pET-taaP), respectively (Table 1). For overexpression studies with P. mirabilis HI4320, the aipA gene was cloned into the pBAD/Myc-His vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to generate plasmid pSAP2035.

Strategene's QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit was used to change nucleotides in the gene to affect a single amino acid in the resulting protein. Site-directed mutants that encode AipA (G247H) and TaaP (G708H) were generated using primer pairs 2122G247H-F/2122G247H-R (with pSAP2022 as the substrate) and 2575G708F/2575G708H-R (with pSAP2025 as the substrate), respectively. Each primer pair carries compatible endonuclease sites for convenient cloning into pET21A. The resulting plasmids were designated pSAP2045 and pSAP2046, respectively.

In-frame deletion of the 153-bp internal region in aipA (nucleotides [nt] 120 to 273) that encodes the putative invasin/Hep_Hag domain was performed by overlapping PCR. Briefly, nt 1 to 120 were amplified using primers 2122-F and 2122Inv-R in the first PCR (PCR-1), and primers 2122Inv-F and 2122-R were designed to amplify nt 273 to 862 in PCR-2. The internal primers 2122Inv-F and 2122Inv-R have a 15-bp overlapping region toward their 5′ ends. Products obtained from reactions 1 and 2 were used as templates for PCR-3, in which primers 2122-F and 2122-R amplified an ∼690-bp PCR product, resulting in an in-frame deletion of the 153-bp internal region of aipA (encoding AipAΔInv), which was then cloned into pET21A to yield plasmid pYA2047. Wild-type aipA or its mutant derivatives were cloned into pET21A to synthesize a C-terminal 6×His-tagged fusion protein. All clones were confirmed by sequencing at the University of Michigan DNA core facility.

Construction of ptaα-aipAβ and ptaα-taaPβ translational fusions.

Translational fusions were generated using PCR. Primers PtaF and PtaαR were used to amplify the 5′ ∼2,140 bp encoding the 710-amino-acid-long passenger domain of Pta (Ptaα) (the native 731 amino acids minus the α-helical region). Simultaneously, primers AipAβF and AipAβR were used to amplify ∼183 bp toward the 3′ end of aipA, which encodes the putative translocator domain of AipA. Primers PtaαR and AipAβF carry a 25-bp complementary region. The two PCR products were individually extracted from the gel, and equal quantities were mixed to serve as substrates in the third reaction. The ∼2,330-bp fusion DNA fragment (encoding Ptaα-AipAβ) was amplified using primers PtaF and AipAβR (both carrying endonuclease sites) and was cloned into pET21A to yield pYA2057 (Table 1).

A similar strategy was applied for creating a DNA fusion product to encode a Ptaα-TaaPβ fusion protein using taaP-specific primers TaaPβF-TaaPβR in conjunction with PtaαF-PtaαR. The resulting fusion PCR product (∼2,375 bp) was cloned into pET21A to yield plasmid pYA2058. Three nucleotides corresponding to Ala were inserted in the junction of ptaα with aipaAβ or taaPβ to ensure the correct reading frame. All clones were confirmed by sequencing at the University of Michigan DNA core facility.

Overexpression of the genes in E. coli strain BL21plysS, localization of the protein, and protein purification.

To overexpress the target genes, each plasmid was transformed into the overexpression strain E. coli BL21plysS. For convenience, the strain will be referred to as Ec-TaaP, Ec-Pta, Ec-Ptaα, Ec-AipA, or Ec-CTL, for example, in the remainder of this paper. All expression studies were performed as described in our earlier studies, except that induction with IPTG was performed at 26 to 28°C. All experiments involving P. mirabilis were performed at 37°C. Synthesis of target proteins was confirmed by separating cell-free lysates on 10% or 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-PAGE followed by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue. To determine the cellular localization of the recombinant proteins, outer membrane protein (OMP) fractions of E. coli BL21plysS were enriched, using the procedure described in our earlier report (2), and each was analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Gene induction and protein localization studies were repeated several times. Trimer or monomer forms of AipA or its variants in OMPs were detected by immunoblotting with anti-6×His (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

AipA or its mutant version, AipAΔInv, was purified as a recombinant protein from enriched outer membrane fractions of E. coli BL21plysS expressing the respective genes, using the method described in our earlier studies (2). The protein concentration was estimated using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay. Identity of all the recombinant proteins and their derivatives was confirmed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight/mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF/MS). Protein samples were separated on 12% SDS-PAGE, and bands were excised from the gel and identified by MALDI-TOF/MS at the University of Michigan Protein Consortium.

Generation of P. mirabilis mutants.

Insertional inactivation of genes in P. mirabilis was performed using a TargeTron mutagenesis kit (catalog no. TA0010; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) as described in our previous studies (1, 2). Briefly, primers EB1d, IBS, and EB2, specific for either gene (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), along with the universal primer provided in the kit were used to construct plasmids pSAP2048 and pSAP2050, which contain reprogrammed group II introns for taaP and aipA, respectively. The isogenic taaPΩkan mutant (ALM2021) and aipAΩkan mutant (ALM2022) (Table 1) of P. mirabilis were obtained by transforming the wild-type strain with the corresponding plasmid and following the procedures outlined in the instruction manual. For cell culture studies alone, we generated the hpmA aipA::kan double mutant (ALM2023) by transforming pSAP2050 into strain ALM2012B (an unmarked hpmA mutant strain of HI4320 generated in our earlier study) (2). The hpmA mutant lacks the secreted toxin, hemolysin, and thus prevents lysis of the epithelial monolayer during adhesion and invasion by P. mirabilis. This mutation, however, does not affect the ability of P. mirabilis to bind or invade epithelial cells (2). All mutations were confirmed by both PCR (to detect insertion of the intron into the gene) and reverse transcription (RT)-PCR (to confirm the absence of gene-specific mRNA). Single and double mutants of P. mirabilis showed a growth rate and motility on agar similar to those of the wild type. For complementation studies, the double mutant hpmA aipA was transformed with plasmid pSAP2035, and synthesis of the protein was confirmed by subjecting the OMP fraction to SDS-PAGE followed by staining with anti-6×His serum.

Binding to the extracellular matrix protein.

BD BioCoat 24-well plates precoated with the ECM protein of interest (collagen I, collagen IV, laminin, or fibronectin) (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) were used for the following assay. Plates coated with bovine serum albumin (BSA) were used as negative controls. Bacterial cells (E. coli BL21plysS or P. mirabilis HI4320) were treated and collected as described above. A cell culture (200 μl) was introduced into each well and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Plates were washed gently with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) twice to remove unbound bacteria. Bound cells were extracted using trypsin solution, and 10-fold dilutions of the extract were plated on LB agar. E. coli BL21plysS carrying an empty vector was used as a control. Binding in each case was calculated as described above. For competition assays, wells were preincubated with different concentrations of BSA, AipA, or AipAΔInv for 2 h prior to being incubated with P. mirabilis HI4320.

Adhesion and gentamicin resistance (invasion) assay.

Eukaryotic host cells were grown to ≥80% confluence in 24-well tissue culture-treated plates (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) in Dulbecco modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with l-glutamine (Gibco), supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 1% nonessential amino acids, and 1% sodium pyruvate. Prior to being infected with bacterial cells, the monolayer was washed twice with antibiotic-free DMEM. Desired bacterial strains were cultured to the appropriate density (induced for 3 h when required), harvested, washed in PBS, and resuspended in serum-free DMEM at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1. Aliquots (300 μl) were overlaid on the eukaryotic cell monolayer at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of approximately 80 to 100 bacteria per cell and spun at 500 × g for 5 min. The number of input bacteria was determined by enumeration of CFUs. Plates were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 2 h. Wells were then washed twice with PBS and incubated with trypsin at 37°C for 3 min to detach eukaryotic cells. The trypsin extract was diluted 10-fold and plated on LB agar (with an appropriate antibiotic) to determine surface-adherent bacteria. Triplicate wells were used to determine the total number of bacteria per well [the percentage of bacterial adhesion = (bacteria recovered/input bacteria) × 100]. Data are expressed as fold increases in adhesion over that of E. coli carrying an empty vector as a control (Ec-CTL) and represent the means and standard errors of the means (SEMs) of the results of four independent studies, each conducted in triplicate.

For microscopic analysis, host cells were cultured on circular poly-d-lysine-coated coverslips, and bacterial cells were overlaid as described above. After being incubated, washed coverslips were fixed with 50% methanol and Giemsa stained (catalog no., GS500; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Slides were examined using an Olympus BX60 microscope, and the images were recorded with an Olympus DP70 camera. Representative images are shown. For determining internalized bacteria, a procedure similar to that described above was followed, except that wells were incubated in DMEM containing 30 μg/ml gentamicin for 2 h and washed with PBS three times before cells were extracted with 0.5 ml of double-distilled water (ddH2O). Eukaryotic host cell lysis was estimated on a monolayer of HeLa cells by measuring the release of intracellular lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) as described in our previous studies (1, 2). Data are expressed as fold increases in invasion over that for E. coli carrying an empty vector used as a control and represent means and SEMs of the results of four independent studies, each done in triplicate. P values were determined using the Mann-Whitney test.

Autoaggregation assay.

Assays were performed as described elsewhere (47, 55) except that LB broth (at pH 8.5) supplemented with Ca2+ and glycerol was used when the aggregation ability of Ec-TaaP, HI4320, or its taaP mutant was tested under alkaline conditions. Briefly, cultures were incubated to late logarithmic phase (postinduction), harvested, washed, and resuspended in phosphate buffer (at the corresponding pH) with an initial OD600 of ∼3.0, which was considered 100% for 0 h after the end of log-phase growth (t0). Cell culture (100 μl) was collected from the upper part at several time points (tn), and the change (decrease) in OD600 due to settling of the cells was determined. The percentage of the initial density (plotted on the y axis) was determined according to the formula (OD600 at t0 − OD600 at tn)/100. Data are expressed as means and standard deviations (SDs) of the results of three independent experiments, each conducted in triplicate, and significance was calculated using Student's t test.

CBA/J model of urinary tract infection (UTI).

All animal studies were performed with 6- to 8-week-old female CBA/J mice obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) as described in our previous studies (2). Anesthetized mice were transurethrally inoculated with an equal mixture (1:1) of wild-type and mutant bacteria resuspended in 50 μl of PBS (pH 7.2). We determined the input of bacteria by CFU enumeration as follows: for HI4320, 1.9 × 108, and for the aipA::kan mutant, 3.3 × 108, for one experiment, and for HI4320, 2.38 × 108, and for the taaP::kan mutant, 3.0 × 108, for the other. One week postinoculation, mice were euthanized, and tissues of interest were harvested immediately for determining the bacterial burden. The protocols used to perform mouse model infection studies were approved by the University of Michigan's University Committee on the Use and Care of Animals. P values were calculated by Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-ranked tests.

RESULTS

Putative structure of AipA and TaaP.

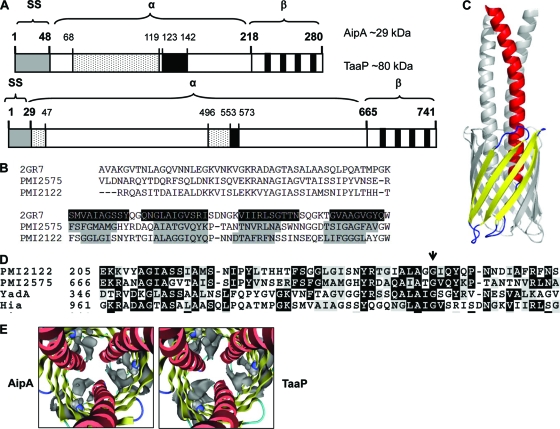

In P. mirabilis HI4320, PMI2122 (842 bp) encodes a 280-amino-acid-long hypothetical protein annotated as adhesion-like autotransporter AipA and belonging to the Hep_Hag family of proteins (54). Analysis by SignalP predicted that residues 1 to 48 toward the N terminus were the putative signal peptide. Amino acid sequences analyzed using a MOTIF search found that positions 49 to 218 constitute the putative passenger, or alpha, domain of the AT, which contains a putative Hep_Hag or invasin domain (residues 68 to 119) and a hemagglutinin motif (residues 123 to 142) (Fig. 1A). C-terminal amino acids 219 to 280 form the translocator, or beta domain, of AipA and are predicted to contain 4 antiparallel beta sheets spanning the inner and outer leaflets of the bacterial outer membrane (Fig. 1A and B).

FIG. 1.

In silico analyses of AipA and TaaP. (A) Schematic representation of 280-amino-acid-long AipA (PMI2122) and 741-amino-acid-long TaaP (PMI2575) proteins. Predicted domains in both proteins and amino acid numbers are given. The N-terminal 48 residues in AipA and 29 amino acids in TaaP form the putative signal peptide (gray box), which is followed by the passenger domain, or alpha (α) domain (aa 49 to 218 for AipA and 30 to 665 for TaaP), which for each protein contains regions homologous to invasin/Hep_Hag (spotted box) and hemagglutinin motifs (black boxes). Amino acids 219 to 280 in AipA and 666 to 741 in TaaP constitute the putative translocator, or beta (β) domain, with 4 transmembrane beta sheets in each (solid black bars). The theoretical mass of each protein is given in kDa. (B) Multiple-sequence alignment by ClustalW of trimeric autotransporter Hia of H. influenzae (2GR7) with the C-terminal regions of TaaP (PMI2575) and AipA (PMI2122) (AipA). Gray-shaded areas are predicted β-sheets, and black-shaded areas are actual β-sheets in the crystal structure. (C) Ribbon representation of the trimeric model of AipA or TaaP. Helices are shown in red, β-strands in yellow, and turns in blue. For better visibility, two monomers are shown in gray. (D) Multiple-sequence alignment of residues in the beta domains of YadA (Y. enterocolitica O:8; GI:23630568), Hia (H. influenzae; GI:21536216), PMI2122 (AipA), and PMI2575 (P. mirabilis HI4320) (TaaP). The arrow indicates the glycine homologous to the conserved Gly-389 in YadA. (E) Ribbon representation of the trimer models of AipA and TaaP, viewed from the extracellular space through the central helical barrel. Gly-247 and Gly-708 are shown in a space-filling representation (gray ribbons). The Gaussian molecular surface is shown at 7 Å around Gly-247 and Gly-708, indicating the existence of one cavity per monomer inside the proteins.

TaaP is a 741-amino-acid-long protein encoded by PMI2575 (2,225 bp) and is annotated as an agglutinating adhesin-like AT belonging to the Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) family of proteins. In silico analyses with SignalP suggested a 29-amino-acid-long signal peptide (residues 1 to 29) toward its N terminus, followed by a 635-amino-acid-long passenger domain (residues 30 to 665) with two much shorter putative Hep_Hag regions (residues 29 to 47 and 496 to 553) and one hemagglutinin region (residues 553 to 573) (Fig. 1A). Amino acids 666 to 741 toward the C terminus form the putative beta, or translocator, domain of TaaP, with four putative antiparallel beta sheets (Fig. 1A and B). According to BLAST analysis, the C-terminal amino residues of AipA and TaaP share approximately 48% and 36% identity, respectively, with Y. enterocolitica adhesin YadA (data not shown). Both the AipA and TaaP sequences terminate in hydrophobic residues, which is a signature feature of bacterial outer membrane proteins, including autotransporters (Fig. 1C).

Homology models of AipA and TaaP.

Homology models of both AipA (PMI21212) and TaaP (PMI2575) were created with MOE, using the crystal structure of Hia (PDB identification no., 2GR7) as a template. Figure 1C presents an overview of the modeled structures in which three individual alpha domains for each protein are exposed at the surface of the structure (red and gray), looping out of the beta barrel formed by the translocator domain with four antiparallel beta sheets. The beta sheets in AipA are 8, 9, 7, and 9 amino acids long and are connected by hydrophilic loops, whereas in TaaP they are comprised of 5, 9, 7, and 8 residues (Fig. 1B, gray shaded area, and Fig. 1C, yellow sheets). The models reveal potentially mechanistically important details. Two gaps in the initial alignment (Fig. 1B) had to be positioned in the loop regions connecting the alpha helix and β-sheet 1 and β-sheets 2, 3, and l, respectively (the secondary structure numbering is in accordance with the Hia template). The loops face toward the periplasm and are shortened in comparison to those of the template. Notably, the overall similarity between these loop-forming sequence stretches is low. If an interaction with other periplasmic proteins is mediated by these loops, a difference can be expected with respect to Hia.

Mutation experiments in YadA demonstrated that the conserved glycine (G389), and therefore also the cavity, is important for its translocation efficiency (16). Figure 1D shows a partial alignment of the translocator domains of Hia and YadA with the putative domains of AipA and TaaP. We found that Gly-247 in AipA and Gly-708 in TaaP are homologous to the conserved Gly-389 and Gly-1006 in YadA and Hia, respectively (arrowhead). We further analyzed our model to identify the conserved Gly in the two Proteus proteins. It is noteworthy that the models possess features that can be observed in other structures of trimeric autotransporters. In the resolved Hia structure (16), for example, an inner cavity exists in the vicinity of the conserved glycine residue. This is also true for our models, as the cavities can be seen when a Gaussian surface (15) is calculated, which approximates the solvent-excluded protein volume. Finding similar cavities in our models near Gly-247 and Gly-708 (Fig. 1E; gray space-filling representation) suggests that AipA and TaaP use a translocation mechanism similar to those of YadA and Hia.

Cellular localization of recombinant proteins in E. coli.

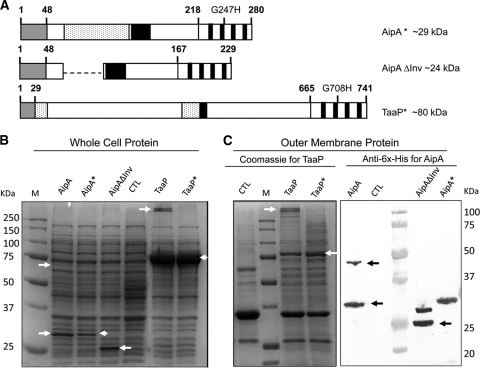

To determine if the predicted glycine in the translocator domains of AipA and TaaP is critical for trimerization, we generated mutant forms of the two proteins by altering their respective conserved Gly to His to generate AipA* [AipA(G247H)] and TaaP* [TaaP(G708H)] (Fig. 2A). We also deleted the putative invasin domain in AipA to generate AipAΔInv to identify its role in the function of the putative AT represented in Fig. 2A.

FIG. 2.

Synthesis and cellular localization of the recombinant proteins AipA and TaaP. (A) AipA Gly-247 and TaaP Gly-708, each homologous to the conserved Gly-389 in YadA, were changed to His to yield AipA* (AipAG247H) and TaaP* (TaaPG708H), respectively. In-frame deletion of the 51-amino-acid-long Hep_Hag/invasin region in the passenger domain of AipA was predicted to yield a shorter protein, AipAΔInv. The theoretical mass of each protein is given in kDa. (B) Whole-cell proteins (6 μg) of E. coli BL21plysS carrying the empty pET21A vector (CTL) or synthesizing either AipA or TaaP or their mutant forms were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. Molecular mass markers (lane M) are shown, and their measurements in kilodaltons are indicated on the left. (C, left panel) Enriched outer membrane protein fractions (8 μg) from E. coli BL21plyS carrying only the pET21A vector (CTL) or the indicated form of TaaP subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie blue staining. (Right panel) Immunoblot of enriched outer membrane protein fractions (8 μg) of E. coli carrying the control plasmid (CTL) or the indicated form of AipA stained with monoclonal anti-6×His followed by a goat anti-rabbit IgG-AP conjugate. Arrows indicate bands corresponding to monomeric or multimeric forms of each protein.

Either the wild-type or the mutant form of each gene was individually expressed in a laboratory strain of E. coli, and the cellular localization of the recombinant protein was analyzed by subjecting either the whole-cell lysate (Fig. 2B) or the enriched outer membrane protein fraction (Fig. 2C) to SDS-PAGE. Synthesis of AipA and TaaP was evident by the presence of bands corresponding to ∼30 kDa and ∼80 kDa, respectively, both in the whole-cell lysates and in the OMP fraction but not in the control strain of E. coli carrying the empty vector (CTL) (Fig. 2B and C). These molecular masses were in agreement with the theoretical estimates. The presence of the two proteins in the outer membrane also indirectly validated the activity of the signal peptide in each case.

As predicted by protein structure modeling, higher-molecular-mass bands specific to the two proteins were also found in both cell fractions analyzed. Lanes containing fractions from Ec-TaaP contained ∼300-kDa multimers specific to TaaP (Fig. 2B and C, left panel). Similarly, the ability of AipA to trimerize in the outer membrane was also evidenced by the presence of an ∼60-kDa band in the OMP fractions of E. coli synthesizing the full-length native form of AipA (Fig. 2C, right panel). Trimerization of the wild-type proteins was resistant to treatment with nonionic detergent (during OMP enrichment) or when they were subjected to heat and denaturing conditions (during SDS-PAGE). The identity of these proteins was confirmed by MALDI-TOF/MS (data not shown).

Consistent with observations made with YadA(G389H) (16), alteration of the homologous Gly residue in AipA (AipA*) or TaaP (TaaP*) prevented the formation of a stable trimer. Although the complete ∼30 kDa of AipA* or ∼80 kDa of TaaP* was synthesized, no high-molecular-mass bands corresponding to the respective trimeric forms were seen (Fig. 2B and C). We did not find multimeric forms of the mutant proteins even under nondenaturing conditions (data not shown), indicating that the Gly-to-His mutation prevents trimerization.

In-frame deletion of the putative invasin domain in AipA (AipAΔInv) resulted in the synthesis of a shorter protein (∼25 kDa) (Fig. 2B and C, right panel). Deletion of this internal region did not prevent its ability to oligomerize, as a higher-molecular-weight band was evident in the OM fraction (Fig. 2C, right panel), although it migrated faster than expected for the multimeric size. We did not find any shorter truncated forms of protein either in the cell free lysates or in the OMP fractions (Fig. 2B and C), confirming that the passenger domains of AipA, TaaP, or their mutant forms remain intact with their beta domains. There was no evidence of shorter proteins that might be a result of protein degradation. In addition, we did not see any indication of the release of either autotransporter into the culture supernatant either by using anti-6×His-tagged serum or by separating the secretome on SDS-PAGE (data not shown).

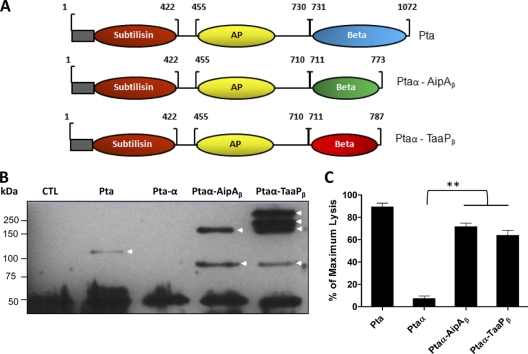

Translocation of heterologous passenger domains.

Translocator, or beta, domains of autotransporters are capable of transporting any heterologous passenger domain to the outer membrane (21, 24). To determine if the C-terminal regions of AipA and TaaP function as true translocators, we translationally fused the regions corresponding to the beta domains of AipA (AipAβ) and TaaP (TaaPβ) individually to the passenger domain of Pta (Ptaα) (Fig. 3A) and determined the presence of fusion proteins (Ptaα-AipAβ and Ptaα-TaaPβ) in the OM of E. coli. As expected, Pta (the positive control), but not Ptaα (the negative control), was seen as an ∼120-kDa monomer in the outer membrane (Fig. 3B). An approximately ∼85-kDa band corresponding to the expected size of Ptaα-AipAβ or Ptaα-TaaPβ was identified by anti-Pta sera in the respective lanes, indicating translocation of the fusion proteins to the OM. In addition, Pta-specific higher-molecular-mass bands (∼175 kDa and above) were seen only in these lanes, due to the oligomerization of AipAβ and TaaPβ in the OM (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Translocation of heterologous passenger domain. (A) Schematic representation of fusion proteins. DNA encoding the 710-amino-acid-long passenger domain of Proteus toxic agglutinin (Ptaα) (without its helical region) was fused to the region encoding AipAβ or TaaPβ to synthesize fusion proteins Ptaα-AipAβ (773 aa) and Ptaα-TaaPβ (787 aa). Native Pta (1,072 amino acids) with its various domains is shown: Subtilisin, the subtilisin domain; AP, the alkaline phosphatase domain; and Beta, the translocator domain. The gray boxes represent the signal sequences of Pta. (B) The enriched outer membrane protein fraction (6 μg) of E. coli synthesizing native Pta, Ptaα alone, either of the fusion proteins, or the protein carrying only the empty vector (CTL) was analyzed by immunoblotting using polyclonal rabbit anti-Pta serum followed by a goat anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate. The Pta in each lane is indicated by arrowheads. The molecular mass of the markers is given in kilodaltons. The ∼50-kDa nonspecific band served as the loading control. (C) E. coli cells synthesizing native Pta, the passenger domain alone (Ptaα), or the fusion forms (Ptaα-AipA or Ptaα-TaaPβ) were individually overlaid on a monolayer of HeLa cells at an MOI of 80:1. Lysis of HeLa cells in each case was determined by measuring the intracellular lactate dehydrogenase released and is presented as a percentage of cell lysis obtained with Triton X-100 (considered 100%). Data presented are means ± SEMs of the results of three independent studies, each performed in triplicate. **, P < 0.01.

We took advantage of the cytotoxicity of Pta (2) to determine if Ptaα was efficiently transported to the exterior of E. coli and hypothesized that interaction of surface-exposed Ptaα with the eukaryotic cell would result in its lysis. Incubation with Ec-Pta resulted in the lysis of ∼90% of HeLa cells, whereas only ∼10% lysis was observed when HeLa cells were incubated with Ec-Ptaα, which was used as a control (Fig. 3C). During the same incubation period, Ec-Ptaα-AipAβ or Ec-Ptaα-TaaPβ lysed only 65 to 75% of HeLa cells (Fig. 3C). The marginal decrease in cytotoxicity of fusion proteins can perhaps be attributed to the trimerization of Ptaα at the OM, which is not its native state. Together these data suggest that AipA and TaaP belong to the trimeric family of autotransporters (AT-2) and can efficiently transport a heterologous protein to the exterior of the cell.

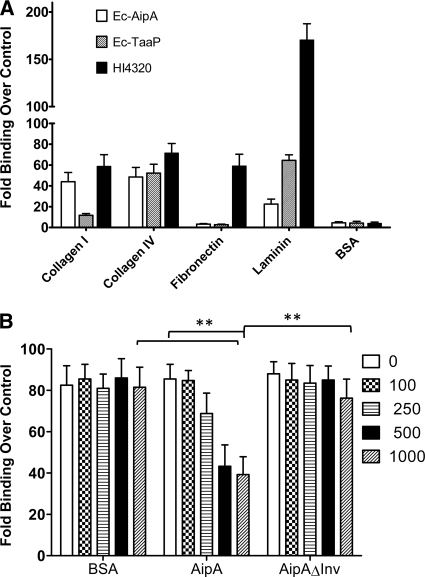

AipA and TaaP bind to extracellular matrix proteins.

Binding to ECM proteins is a common feature found in several AT-2s (10, 52, 53); hence, we determined the relative ECM binding abilities of Ec-AipA and Ec-TaaP using an in vitro assay. Ec-AipA bound to collagens I and IV and laminin, with a higher affinity for collagen IV (Fig. 4A, white bars). Ec-TaaP also bound to the same ECM proteins, with laminin being the most preferred receptor (Fig. 4A, striped bars). Neither protein mediated binding to fibronectin. P. mirabilis HI4320, used as a positive control, bound to all the ECM proteins tested, having the highest affinity for laminin, followed by collagen IV, collagen I, and fibronectin (Fig. 4A, black bars), although the difference was not significant. The level of binding of P. mirabilis to ECM proteins was consistently higher than that mediated by either AT. No binding to bovine serum albumin (BSA) (control) was observed.

FIG. 4.

Binding to ECM proteins. (A) Binding of E. coli carrying AipA (Ec-AipA) or TaaP (Ec-TaaP) and P. mirabilis HI4320 (HI4320) to individual ECM proteins presented as the fold increase over the level of binding by Ec-CTL (y axis). (B) Relative abilities of bovine serum albumin (BSA) or purified wild-type AipA (AipA) or AipA lacking the invasin domain (AipAΔInv) to reduce the binding ability of HI4320 to collagen I. Binding in each case is expressed as the fold increase over that determined for Ec-CTL. Concentrations (nM) of competing proteins are given. Means ± SEMs from experiments conducted in triplicate are shown. **, P < 0.01, as determined using Student's t test.

AipA appeared to contribute to the majority of collagen I binding by HI4320; to further confirm this observation, collagen I plates were preincubated with various concentrations of BSA (as a control), AipA, or AipΔInv, and their individual effects on HI4320 binding to collagen I were measured. HI4320 bound to collagen I at an approximately 85-fold (considered 100%)-higher level than the E. coli vector control (Fig. 4A, black bars, and 4B). BSA did not inhibit binding even at the highest concentration (1,000 nM) tested (Fig. 4B). Preincubation with purified AipA decreased binding of HI4320 to collagen I in a concentration-dependent manner, where 250 nM AipA decreased binding by about 20-fold (∼25%), and 500 or 1,000 nM AipA reduced HI4320 binding by approximately 50% (Fig. 4B), which was a significantly (P < 0.01) lower level than that by either 1,000 nM BSA or binding determined without any competitor (0 nM AipA). Interestingly, prior to the blocking, 1,000 nM purified AipAΔInv did not affect the interaction of HI4320 with collagen I, suggesting a critical role for the 51-amino-acid-long putative internal invasin (Hep_Hag) domain in mediating this function.

AipA, but not TaaP, mediates adhesion to a eukaryotic host.

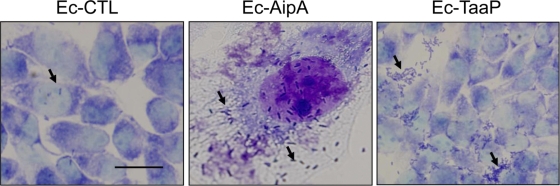

A monolayer of HEK293 cells was overlaid with Ec-CTL, Ec-AipA, or Ec-TaaP to qualitatively determine the nature of the interactions of the two trimeric ATs with the host. There was no evidence of cytotoxicity associated with either protein. Ec-CTL did not mediate adherence to host cells (Fig. 5), whereas approximately 20 bacterial cells bound to a single HEK293 cell in the case of Ec-AipA. There was no host cell adhesion seen with Ec-TaaP; however, aggregation was exhibited on the surfaces of the poly-l-lysine-coated coverslips (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Autotransporter-mediated interaction of E. coli with eukaryotic cells. E. coli cells carrying pET21A as a control (Ec-CTL), Ec-AipA, or Ec-TaaP were overlaid on confluent monolayers of human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293) (MOI, 80 to 100:1) and incubated for 1 h. Giemsa-stained cells are shown at a magnification of ×100. Bar, 100 μm. Arrows point to bacterial cells.

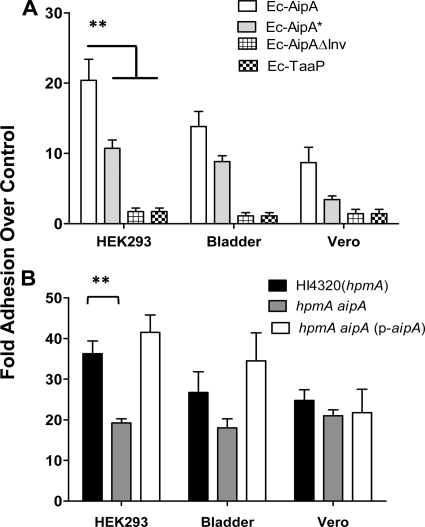

We quantitatively estimated the interaction mediated by these two proteins with different epithelial cell monolayers. Ec-AipA adhered to the three cell lines tested, with the highest affinity to HEK293 (Fig. 6A). The host cell adhesion of Ec-AipA* was reduced by about 50% (P < 0.01), suggesting that trimerization of AipA in the OM was required for its maximal activity. Similarly, adhesion of Ec-AipAΔInv was also significantly (P < 0.01) reduced (Fig. 6A), confirming the significance of the putative invasin region (residues 68 to 119) in mediating adhesion. A similar trend was observed with all the eukaryotic cells tested. Ec-TaaP showed negligible adhesion (Fig. 6A).

FIG. 6.

Adhesion of bacterial cells to a eukaryotic cell monolayer. (A) Quantitative estimation of host cell adhesion by E. coli synthesizing wild-type or mutant forms of the autotransporter protein. Ec-AipA, E. coli synthesizing AipA; Ec-AipA*, E. coli synthesizing AipA (G247H); Ec-AipAΔInv, E. coli synthesizing AipA lacking the invasion domain; and Ec-TaaP, E. coli synthesizing TaaP. (B) Estimation of host cell adhesion by P. mirabilis HI4320(hpmA), the hpmA aipA double mutant, or the double mutant complemented with wild-type aipA in trans [hpmA aipA (p-aipA)]. Adhesion is given as the fold increase over that determined for Ec-CTL (y axis). The eukaryotic cells used were human embryonic kidney epithelial cells (HEK293), UMUC-3 human bladder epithelial cells, and Vero monkey kidney epithelial cells. Means ± SEMs from experiments conducted in triplicate are shown. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, calculated using Student's t test.

To confirm the relevance of AipA in overall adhesion by P. mirabilis, we compared levels of adhesion by HI4320(hpmA) (parent strain) and the hpmA aipA double mutant. These mutations did not affect either the growth rate or the motility of P. mirabilis (data not shown). Inactivation of aipA, however, significantly (P < 0.05) reduced the pathogen's ability to bind to HEK293 and bladder epithelial cells compared to that of the hpmA parent strain [Fig. 6B, HI4320(hpmA) versus hpmA aipA]. Complementing the double mutant with the wild-type aipA gene reversed the phenotype, confirming that the decrease was dependent on the aipA mutation. We attribute increased adhesion of the complemented strain [Fig. 6B, hpmA versus hpmA aipA (p-aipA)] to increased levels of AipA available on the cell surface, which are due to higher levels of expression of aipA on a medium-copy-number plasmid. Binding of HI4320(hpmA) to Vero cells was generally at a lower level (Fig. 6B).

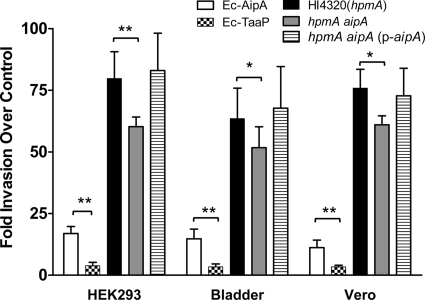

AipA-mediated invasion of epithelial cells.

Trimeric autotransporters such as YadA, Hia, UpaG and others are bi- or multifunctional proteins (10, 55). A gentamicin resistance assay was used as a measure to determine host invasion mediated by AipA. As in the case of adherence, Ec-AipA was able to invade HEK293 cells, human bladder epithelial cells, and Vero cells at an approximately 20-fold-higher level than the vector control (Fig. 7). Invasion was marginally lower in the case of Vero cells. Invasion by Ec-AipA* or Ec-AipAΔInv (data not shown) or Ec-TaaP was negligible and was at a significantly lower level (P < 0.01) than that by Ec-AipA (Fig. 7). To determine the significance of AipA in P. mirabilis invasion, we compared the intracellular parent strain HI4320 (hpmA), the hpmA aipA strain, and the complement strain [hpmA aipA (p-aipA)] recovered from each eukaryotic monolayer. The parent strain showed between a 60- and 75-fold-higher level of invasion (over that of the Ec-vector control), with HEK293 cells being the most favorable host (Fig. 7). Invasion by the hpmA aipA strain was at a significantly lower level than that by the parent strain for both HEK293 cells (P < 0.001) and bladder or Vero cells (P < 0.05). This phenotype was reversed upon complementation with wild-type aipA in trans, confirming that the decrease was indeed due to the loss of AipA in the double mutant (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Bacterial invasion of the host cell. An HEK293, UMUC-3, or Vero cell monolayer was individually incubated with E. coli or P. mirabilis cells (80 to 100:1) for 1 h, followed by 2 h of incubation with gentamicin (30 μg/ml). Internalized bacterial cells were enumerated by plating ddH2O extracts of washed eukaryotic cells. The y axis represents the fold increase in invasion over that for Ec-CTL. Means ± SEMs of the results from experiments conducted in triplicate are shown. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. Significance was calculated using Student's t test.

TaaP mediates autoagglutination.

TaaP was annotated as an agglutinating adhesin belonging to the STEC family of proteins. Although we did not observe any adhesion mediated by TaaP, we did find preliminary evidence of TaaP-mediated autoagglutination of E. coli (Fig. 3). To quantitatively measure autoaggregation mediated by the two proteins, Ec-AipA, Ec-TaaP, or Ec-TaaP* was each individually resuspended in PBS (OD600 ∼ 3.0), and the decrease in the OD600 in the upper layer of the culture over time was measured. After 8 h, Ec-TaaP, cultured and processed under neutral pH, showed maximal autoaggregation, with approximately 80% reduction in cell density (Fig. 8A, Ec-TaaP). Since colonization of the urinary tract by P. mirabilis and subsequent urease activity turns the microenvironment alkaline (∼pH 8.5 to 9.0), we asked whether the change in pH affects the ability of TaaP to mediate autoaggregation of E. coli. The rate of decrease in cell density was marginally lower, yet not significantly different, under alkaline pH (Fig. 7A, Ec-TaaP [pH 8.5]). Autoaggregation was severely impaired (with only an ∼25% reduction in OD600) in Ec-TaaP*, indicating that optimal agglutination requires protein trimerization. Ec-CTL (control strain) and Ec-AipA each showed only 15 to 20% reduction in cell density, suggesting that there is no role for AipA in autoagglutination (Fig. 7A).

FIG. 8.

Autoaggregation of bacterial cells. Autoaggregation of E. coli (A) or P. mirabilis HI4320 (B) was determined by measuring the decrease in optical density of the uppermost layer of suspended cells over time. The OD600 at t0 was considered to be 100%. The percent decrease in the optical density of suspended bacterial cells (y axis) was plotted against time in hours (x axis). Cells were cultured and incubated at pH 7.2 or pH 8.5 (as indicated). Means ± SDs of the results of three independent experiments are given. The inset in panel A shows tubes containing Ec-AipA, Ec-TaaP*, and Ec-TaaP, respectively (from left to right), after 8 h.

Similarly, the effect of taaP inactivation on the autoagglutination of P. mirabilis HI4320 was determined. There was an ∼45 to 50% decrease in cell density of HI4320 (Fig. 8A) after 8 h of incubation, which was consistent with our earlier studies (2). This was significantly (P < 0.05) different from that of the taaP strain, where only a 25 to 30% decrease in cell density was observed (Fig. 8B). We also determined the effect of the mutation on aggregation by cells cultured and processed at pH 8.2 to 8.5. Both HI4320 and the taaP strain displayed similar rates and degrees of autoaggregation (Fig. 8B), which suggests a possible compensatory role for other surface structures.

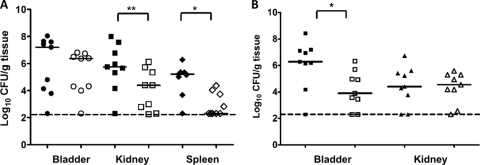

Roles for AipA and TaaP in vivo.

AipA and TaaP demonstrated host cell adhesion/invasion and autoagglutination phenotypes, respectively, so we tested whether the loss of either AT affects the ability of the pathogen to colonize the host. Mice were cochallenged with equal numbers of parental strain HI4320 and its isogenic aipA or taaP mutant. The aipA mutant was significantly outcompeted by the wild type, in both the kidney (P < 0.001) and the spleen (P < 0.05) of mice on day 7. The median log10 CFU/g values for the wild-type and aipA::kan strains were 5.8 and 4.3, respectively, in kidney and 5.5 (wild type) and 2.0 (aipA::kan) in spleen (Fig. 9A, open versus closed symbols). For the taaP strain versus the wild type, significant attenuation of the mutant was seen only in the bladder (P < 0.05), with the median CFU/g around 3.9 compared to log10 6.2 CFU/g of wild-type cells recovered (Fig. 9B). The overall bacterial burden in the spleens was lower than that observed in our other studies (data not shown). No difference in colonization by the wild type or either mutant was observed in an independent challenge (data not shown). We did not determine the virulence of each mutant strain complemented with its respective mutant G-to-H variants, as we predicted attenuation based on their compromised activity in vitro.

FIG. 9.

Cochallenges of CBA/J mice with P. mirabilis HI4320 and the isogenic aipA or taaP mutant. Assessment of virulence of the aipA::kn (A) or taaP::kn (B) strain in a CBA/J mouse model of ascending UTI 7 days after cochallenge with the parent strain. Each symbol represents log10 CFU per ml of urine or g of tissue from an individual mouse. Solid symbols represent counts for the wild-type HI4320, and open symbols represent counts for the mutants. The dotted lines indicate the limit of detection. Solid black bars represent median values. Two-tailed P values were determined by the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

P. mirabilis proteins that either cause damage to the host or are critical for virulence include the urea-hydrolyzing urease (23); several types of fimbriae that mediate hemagglutination, agglutination, motility, and adhesion to uroepithelia (39); ZapA metalloprotease (37); siderophores for binding extracellular iron; flagella for motility, lipopolysaccharide, and hemolysin; and a few outer membrane proteins (3, 7, 33, 35, 41, 56, 60). The latest addition to this group is the novel bifunctional autotransporter Proteus toxic agglutinin (Pta). This surface cytotoxin is induced under alkaline conditions, promotes the agglutination of P. mirabilis, and is required for colonization of the upper urinary tract of mice (1, 2). In this study, we characterized two additional autotransporters, annotated as the AT-2 family of proteins, and independently characterized their structure-function relationship in vitro and their significance in vivo in a mouse model of ascending urinary tract infections (UTIs).

We predicted the structure of AipA and TaaP using the available three-dimensional structure of the Hia protein from H. influenzae as a template (PDB identification no., 2GR7) and identified four putative antiparallel beta sheets in the translocator domain of each protein. These models also suggested that they both form homotrimers. The interface region between the model monomers is formed by antiparallel β-sheets, with the backbone atoms being in the correct orientation to form the required hydrogen bond network, and the three alpha-helices, which form a hydrophobic core (residues F655, L656, I662, V665, A669, I673, and V676 for PMI2575, and I194, L197, V201, L204, V208, and I212 for PMI2122) (data not shown). This supports the reliability of the structure prediction. Our model also identified that Gly-247 in AipA and Gly-708 in TaaP are homologous to the conserved glycine in the prototypic AT-2 YadA (Gly-389), which is critical for trimerization. We wish to point out that according to the WHAT_CHECK (20) tests, both homology models contain several unusual side chain conformations, especially short interatom distances, unusual torsion angles, and deviations at some planar side chains. Therefore, any details at the atomic level of these models must be treated with caution.

The structure-function relationship of AipA and TaaP as predicted by in silico analyses was further verified using multiple experimental approaches. First, both AipA and TaaP, expressed as individual recombinant proteins in E. coli, formed stable multimeric forms in the outer membrane. The approximate sizes of the recombinant proteins, as seen on SDS-PAGE, agree with the expected values. We found no evidence of secondary processing to release the passenger domain from the translocator for either protein, as was the case for Hap (13), AIDA, or other larger trimeric autotransporters (14), nor was there any evidence of either protein being secreted to the extracellular milieu. Second, altering the predicted conserved Gly-247 in AipA or Gly-708 in TaaP to histidine abolished stable trimerization, as seen with YadA(G389H). However, the levels of mutant proteins synthesized here did not differ from their respective wild-type levels, a phenomenon different from what was observed with YadA (16); whether this is due to the lack of specific proteases in E. coli that might be responsible for the processing of these proteins in P. mirabilis remains to be investigated. Finally, the ability of AipAβ or TaaPβ (the C-terminal 62 and 76 amino acids, respectively) to transport the heterologous Ptaα to the exterior of the cell confirms that these are functional autotransporter sequences. Based on these data, we conclude that AipA and TaaP belong to the AT-2 family of autotransporters.

In the host, ECM proteins are exposed due to disruption of the epithelial barrier and serve as receptors to which pathogens such as H. influenzae, Helicobacter pylori, Neisseria meningitidis (12), Yersinia spp., uropathogenic E. coli (55), and others bind (29). Autotransporters such as YadA (53), UspA2, UpaG (30), NhhA (44), etc., often serve as possible ligands on the surfaces of bacteria and mediate this binding. The interaction of P. mirabilis surface structures with ECM proteins was earlier described in two different studies. First, ZapA, a secreted metalloprotease, cleaves collagen, laminin, and fibronectin (6). Second, the galectin-3 in the plasma membrane of Madin-Darby canine kidney cells serves as the ligand for nonagglutinating fimbriae (NAF) (4). In this study, we showed that AipA and TaaP each mediate binding to various ECM proteins, albeit with different affinities. The preferred higher levels of binding of AipA to collagen and TaaP to laminin may signify tissue-specific activities of these autotransporters in the host. However, we do not eliminate the possibility of other host receptors interacting with AipA or TaaP. In addition, lack of binding to fibronectin by either AT, as well as a higher level of binding by P. mirabilis, signifies possible functions of other P. mirabilis surface proteins.

AipA also mediates adhesion and invasion of the human uroepithelial monolayer with higher affinity toward HEK293 cells, and both activities require trimerization in the OM. These consequences were different from the effects seen with YadA of Y. enterocolitica, where trimerization is required for transport, surface display, serum resistance, and hence virulence, but not for adhesion and invasion (16). Cell adherence and invasion demonstrated by AipA were predominantly governed by the invasin (Hep_Hag) motif in the passenger domain, since internal deletion of the corresponding 51 amino acids abolished both activities. Interestingly, loss of this domain also dramatically affects its ability to bind ECM components. There are several conserved seven-residue repeats of the Hep_Hag family of proteins seen in this region; further analysis will be needed to identify residues that are critical for the two different functions, ECM binding and adhesion/invasion. No hemagglutination was seen with either mouse or sheep red blood cells (data not shown), and AipA did not confer resistance to serum killing (data not shown). Based on the data obtained, we concluded that AipA is a multifunctional trimeric protein that mediates adhesion and invasion of uroepithelia and is a surface ligand that interacts with matrix proteins.

TaaP was annotated as a member of the STEC family of agglutinating adhesins. The protein mediated binding to ECM proteins, especially to laminin and collagen IV, and promoted autoagglutination of bacterial cells. It did not exhibit hemagglutination or confer resistance to serum (data not shown). The trimerization of TaaP and its agglutinating activity were severely impaired when Gly-708, the putative homolog of conserved Gly-389 in YadA, was changed to His (TaaP*). This was similar to what was seen in the case of YadA(G389H), where the mutant protein failed to form a stable trimer and showed significantly reduced agglutination activity (16). We thus concluded that Gly-708 in TaaP is the invariant glycine present in the translocator domains of AT-2s. Comparing the autoagglutination activities of the wild-type and the taaP strain under two different pH environments suggested that TaaP might be significant in the process of autoaggregation only under neutral pH and that other surface proteins with redundant functions may be dominant at alkaline pH. One candidate surface protein that might compensate the loss of TaaP-mediated aggregation under these conditions is Proteus toxic agglutinin (Pta). Pta is an alkaline phosphatase-like agglutinin whose expression and activity were maximal between pH 8.2 and 9.0. We could perhaps attribute the lack of a phenotype for the taaP strain under alkaline pH to the increased synthesis (and activity) of Pta and/or to repression of taaP at alkaline pH. If the former scenario were to be considered, then TaaP may promote agglutination of Proteus at the early phase of infection, perhaps along with the fimbrial proteins (MrpA, for example) (38), and Pta activity may dominate as the microenvironment turns alkaline due to urease activity. We could not obtain the pta taaP double mutant of P. mirabilis to test these hypotheses. Interestingly, the taaP strain is attenuated in the bladder, whereas the pta strain is more severely attenuated in the kidney (and spleen) of mice (2). This may signify the spatial significance of the two autotransporters in the host, and further studies will be needed to validate these possibilities.

P. mirabilis is an opportunistic uropathogen that causes complicated urinary tract infections (22). Prevention of Proteus infections requires a multivalent vaccine (27), which is feasible only upon gaining comprehensive understanding of the surface and/or cellular components of the pathogen that are critical for its virulence. Here we demonstrate that the two trimeric autotransporters AipA and TaaP offer advantage to P. mirabilis in the upper and lower urinary tracts, respectively. Inclusion of autotransporters (trimeric or conventional) (49) in a multicomponent vaccine is effective in the case of pertactin (Bordetella pertussis) or the immunogenic Hap (H. influenzae), among others (28, 57). Neither AipA nor TaaP appears to be immunogenic (32, 34), but their incorporation in a multivalent vaccine to protect against P. mirabilis infections could prove beneficial.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Rebecca Tarrien and Shilpa Gadwal for assistance in conducting in vitro assays, Sara N. Smith for help with mouse colonization experiments, and the laboratories of Roy Curtiss III and Josephine Clarke-Curtiss. Thanks are also due to Vandana Malhotra for reviewing the manuscript and Smitha M. Thatha for assistance with the preparation of figures.

The project was funded by Public Health Service grants AI059722 and AI43363 from the National Institutes of Health to H.L.T.M. MALDI-TOF/MS analysis was provided by the Michigan Proteome Consortium (www.proteomeconsortium.org), which is supported in part by funds from the Michigan Life Sciences Corridor.

Editor: A. J. Bäumler

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 August 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://iai.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alamuri, P., K. A. Eaton, S. D. Himpsl, S. N. Smith, and H. L. Mobley. 2009. Vaccination with proteus toxic agglutinin, a hemolysin-independent cytotoxin in vivo, protects against Proteus mirabilis urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 77:632-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alamuri, P., and H. L. Mobley. 2008. A novel autotransporter of uropathogenic Proteus mirabilis is both a cytotoxin and an agglutinin. Mol. Microbiol. 68:997-1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allison, C., N. Coleman, P. L. Jones, and C. Hughes. 1992. Ability of Proteus mirabilis to invade human urothelial cells is coupled to motility and swarming differentiation. Infect. Immun. 60:4740-4746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altman, E., B. A. Harrison, R. K. Latta, K. K. Lee, J. F. Kelly, and P. Thibault. 2001. Galectin-3-mediated adherence of Proteus mirabilis to Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. Biochem. Cell Biol. 79:783-788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barenkamp, S. J., and J. W. St. Geme III. 1996. Identification of a second family of high-molecular-weight adhesion proteins expressed by non-typable Haemophilus influenzae. Mol. Microbiol. 19:1215-1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belas, R., J. Manos, and R. Suvanasuthi. 2004. Proteus mirabilis ZapA metalloprotease degrades a broad spectrum of substrates, including antimicrobial peptides. Infect. Immun. 72:5159-5167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coker, C., C. A. Poore, X. Li, and H. L. Mobley. 2000. Pathogenesis of Proteus mirabilis urinary tract infection. Microbes Infect. 2:1497-1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cole, C., J. D. Barber, and G. J. Barton. 2008. The Jpred 3 secondary structure prediction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:W197-W201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cotter, S. E., N. K. Surana, S. Grass, and J. W. St. Geme III. 2006. Trimeric autotransporters require trimerization of the passenger domain for stability and adhesive activity. J. Bacteriol. 188:5400-5407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cotter, S. E., N. K. Surana, and J. W. St. Geme III. 2005. Trimeric autotransporters: a distinct subfamily of autotransporter proteins. Trends Microbiol. 13:199-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desvaux, M., N. J. Parham, and I. R. Henderson. 2004. The autotransporter secretion system. Res. Microbiol. 155:53-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eberhard, T., R. Virkola, T. Korhonen, G. Kronvall, and M. Ullberg. 1998. Binding to human extracellular matrix by Neisseria meningitidis. Infect. Immun. 66:1791-1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fink, D. L., L. D. Cope, E. J. Hansen, and J. W. St. Geme III. 2001. The Hemophilus influenzae Hap autotransporter is a chymotrypsin clan serine protease and undergoes autoproteolysis via an intermolecular mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 276:39492-39500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Girard, V., and M. Mourez. 2006. Adhesion mediated by autotransporters of Gram-negative bacteria: structural and functional features. Res. Microbiol. 157:407-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grant, J. A., B. T. Pickup, and A. Nicholls. 2001. A smooth permittivity function for Poisson-Boltzmann solvation methods. J. Comput. Chem. 22:608-640. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grosskinsky, U., M. Schutz, M. Fritz, Y. Schmid, M. C. Lamparter, P. Szczesny, A. N. Lupas, I. B. Autenrieth, and D. Linke. 2007. A conserved glycine residue of trimeric autotransporter domains plays a key role in Yersinia adhesin A autotransport. J. Bacteriol. 189:9011-9019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henderson, I. R., R. Cappello, and J. P. Nataro. 2000. Autotransporter proteins, evolution and redefining protein secretion. Trends Microbiol. 8:529-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henderson, I. R., and J. P. Nataro. 2001. Virulence functions of autotransporter proteins. Infect. Immun. 69:1231-1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henderson, I. R., F. Navarro-Garcia, M. Desvaux, R. C. Fernandez, and D. Ala'Aldeen. 2004. Type V protein secretion pathway: the autotransporter story. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68:692-744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hooft, R. W., G. Vriend, C. Sander, and E. E. Abola. 1996. Errors in protein structures. Nature 381:272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoopman, T. C., W. Wang, C. A. Brautigam, J. L. Sedillo, T. J. Reilly, and E. J. Hansen. 2008. Moraxella catarrhalis synthesizes an autotransporter that is an acid phosphatase. J. Bacteriol. 190:1459-1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobsen, S. M., D. J. Stickler, H. L. Mobley, and M. E. Shirtliff. 2008. Complicated catheter-associated urinary tract infections due to Escherichia coli and Proteus mirabilis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 21:26-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson, D. E., R. G. Russell, C. V. Lockatell, J. C. Zulty, J. W. Warren, and H. L. Mobley. 1993. Contribution of Proteus mirabilis urease to persistence, urolithiasis, and acute pyelonephritis in a mouse model of ascending urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 61:2748-2754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jose, J. 2006. Autodisplay: efficient bacterial surface display of recombinant proteins. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 69:607-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larkin, M. A., G. Blackshields, N. P. Brown, R. Chenna, P. A. McGettigan, H. McWilliam, F. Valentin, I. M. Wallace, A. Wilm, R. Lopez, J. D. Thompson, T. J. Gibson, and D. G. Higgins. 2007. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23:2947-2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li, X., C. V. Lockatell, D. E. Johnson, M. C. Lane, J. W. Warren, and H. L. Mobley. 2004. Development of an intranasal vaccine to prevent urinary tract infection by Proteus mirabilis. Infect. Immun. 72:66-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, X., and H. L. Mobley. 2002. Vaccines for Proteus mirabilis in urinary tract infection. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 19:461-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu, D. F., K. W. Mason, M. Mastri, M. Pazirandeh, D. Cutter, D. L. Fink, J. W. St. Geme III, D. Zhu, and B. A. Green. 2004. The C-terminal fragment of the internal 110-kilodalton passenger domain of the Hap protein of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae is a potential vaccine candidate. Infect. Immun. 72:6961-6968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez, J. J., M. A. Mulvey, J. D. Schilling, J. S. Pinkner, and S. J. Hultgren. 2000. Type 1 pilus-mediated bacterial invasion of bladder epithelial cells. EMBO J. 19:2803-2812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McMichael, J. C., M. J. Fiske, R. A. Fredenburg, D. N. Chakravarti, K. R. VanDerMeid, V. Barniak, J. Caplan, E. Bortell, S. Baker, R. Arumugham, and D. Chen. 1998. Isolation and characterization of two proteins from Moraxella catarrhalis that bear a common epitope. Infect. Immun. 66:4374-4381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meng, G., N. K. Surana, J. W. St. Geme III, and G. Waksman. 2006. Structure of the outer membrane translocator domain of the Haemophilus influenzae Hia trimeric autotransporter. EMBO J. 25:2297-2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moayeri, N., C. M. Collins, and P. O'Hanley. 1991. Efficacy of a Proteus mirabilis outer membrane protein vaccine in preventing experimental Proteus pyelonephritis in a BALB/c mouse model. Infect. Immun. 59:3778-3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mobley, H. L., M. D. Island, and G. Massad. 1994. Virulence determinants of uropathogenic Escherichia coli and Proteus mirabilis. Kidney Int. Suppl. 47:S129-S136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nielubowicz, G. R., S. N. Smith, and H. L. Mobley. 2008. Outer membrane antigens of the uropathogen Proteus mirabilis recognized by the humoral response during experimental murine urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 76:4222-4321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nielubowicz, G. R., S. N. Smith, and H. L. Mobley. 2010. Zinc uptake contributes to motility and provides a competitive advantage to Proteus mirabilis during experimental urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 78:2823-2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pearson, M. M., M. Sebaihia, C. Churcher, M. A. Quail, A. S. Seshasayee, N. M. Luscombe, Z. Abdellah, C. Arrosmith, B. Atkin, T. Chillingworth, H. Hauser, K. Jagels, S. Moule, K. Mungall, H. Norbertczak, E. Rabbinowitsch, D. Walker, S. Whithead, N. R. Thomson, P. N. Rather, J. Parkhill, and H. L. Mobley. 2008. Complete genome sequence of uropathogenic Proteus mirabilis, a master of both adherence and motility. J. Bacteriol. 190:4027-4037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phan, V., R. Belas, B. F. Gilmore, and H. Ceri. 2008. ZapA, a virulence factor in a rat model of Proteus mirabilis-induced acute and chronic prostatitis. Infect. Immun. 76:4859-4864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rocha, S. P., W. P. Elias, A. M. Cianciarullo, M. A. Menezes, J. M. Nara, R. M. Piazza, M. R. Silva, C. G. Moreira, and J. S. Pelayo. 2007. Aggregative adherence of uropathogenic Proteus mirabilis to cultured epithelial cells. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 51:319-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rocha, S. P., J. S. Pelayo, and W. P. Elias. 2007. Fimbriae of uropathogenic Proteus mirabilis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 51:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roggenkamp, A., N. Ackermann, C. A. Jacobi, K. Truelzsch, H. Hoffmann, and J. Heesemann. 2003. Molecular analysis of transport and oligomerization of the Yersinia enterocolitica adhesin YadA. J. Bacteriol. 185:3735-3744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rózalski, A., Z. Sidorczyk, and K. Kotelko. 1997. Potential virulence factors of Proteus bacilli. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61:65-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 43.Sareneva, T., H. Holthofer, and T. K. Korhonen. 1990. Tissue-binding affinity of Proteus mirabilis fimbriae in the human urinary tract. Infect. Immun. 58:3330-3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scarselli, M., D. Serruto, P. Montanari, B. Capecchi, J. Adu-Bobie, D. Veggi, R. Rappuoli, M. Pizza, and B. Arico. 2006. Neisseria meningitidis NhhA is a multifunctional trimeric autotransporter adhesin. Mol. Microbiol. 61:631-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scavone, P., A. Miyoshi, A. Rial, A. Chabalgoity, P. Langella, V. Azevedo, and P. Zunino. 2007. Intranasal immunisation with recombinant Lactococcus lactis displaying either anchored or secreted forms of Proteus mirabilis MrpA fimbrial protein confers specific immune response and induces a significant reduction of kidney bacterial colonisation in mice. Microbes Infect. 9:821-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scavone, P., V. Sosa, R. Pellegrino, U. Galvalisi, and P. Zunino. 2004. Mucosal vaccination of mice with recombinant Proteus mirabilis structural fimbrial proteins. Microbes Infect. 6:853-860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schütz, M., E. M. Weiss, M. Schindler, T. Hallstrom, P. F. Zipfel, D. Linke, and I. B. Autenrieth. 2010. Trimer stability of YadA is critical for virulence of Yersinia enterocolitica. Infect. Immun. 78:2677-2690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stathopoulos, C., D. R. Hendrixson, D. G. Thanassi, S. J. Hultgren, J. W. St. Geme III, and R. Curtiss III. 2000. Secretion of virulence determinants by the general secretory pathway in gram-negative pathogens: an evolving story. Microbes Infect. 2:1061-1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stenger, R. M., M. C. Poelen, E. E. Moret, B. Kuipers, S. C. Bruijns, P. Hoogerhout, M. Hijnen, A. J. King, F. R. Mooi, C. J. Boog, and C. A. van Els. 2009. Immunodominance in mouse and human CD4+ T-cell responses specific for the Bordetella pertussis virulence factor P.69 pertactin. Infect. Immun. 77:896-903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stickler, D., L. Ganderton, J. King, J. Nettleton, and C. Winters. 1993. Proteus mirabilis biofilms and the encrustation of urethral catheters. Urol. Res. 21:407-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Surana, N. K., D. Cutter, S. J. Barenkamp, and J. W. St. Geme III. 2004. The Haemophilus influenzae Hia autotransporter contains an unusually short trimeric translocator domain. J. Biol. Chem. 279:14679-14685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tahir, Y. E., P. Kuusela, and M. Skurnik. 2000. Functional mapping of the Yersinia enterocolitica adhesin YadA. Identification of eight NSVAIG-S motifs in the amino-terminal half of the protein involved in collagen binding. Mol. Microbiol. 37:192-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tamm, A., A. M. Tarkkanen, T. K. Korhonen, P. Kuusela, P. Toivanen, and M. Skurnik. 1993. Hydrophobic domains affect the collagen-binding specificity and surface polymerization as well as the virulence potential of the YadA protein of Yersinia enterocolitica. Mol. Microbiol. 10:995-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tiyawisutsri, R., M. T. Holden, S. Tumapa, S. Rengpipat, S. R. Clarke, S. J. Foster, W. C. Nierman, N. P. Day, and S. J. Peacock. 2007. Burkholderia Hep_Hag autotransporter (BuHA) proteins elicit a strong antibody response during experimental glanders but not human melioidosis. BMC Microbiol. 7:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Valle, J., A. N. Mabbett, G. C. Ulett, A. Toledo-Arana, K. Wecker, M. Totsika, M. A. Schembri, J. M. Ghigo, and C. Beloin. 2008. UpaG, a new member of the trimeric autotransporter family of adhesins in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 190:4147-4161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Walker, K. E., S. Moghaddame-Jafari, C. V. Lockatell, D. Johnson, and R. Belas. 1999. ZapA, the IgA-degrading metalloprotease of Proteus mirabilis, is a virulence factor expressed specifically in swarmer cells. Mol. Microbiol. 32:825-836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wells, T., J. J. Tree, G. L. Ulett, and M. A. Schembi. 2007. Autotransporter proteins: novel targets at the bacterial cell surface. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 274:163-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yen, Y. T., A. Karkal, M. Bhattacharya, R. C. Fernandez, and C. Stathopoulos. 2007. Identification and characterization of autotransporter proteins of Yersinia pestis KIM. Mol. Membr. Biol. 24:28-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhao, H., X. Li, D. E. Johnson, I. Blomfield, and H. L. Mobley. 1997. In vivo phase variation of MR/P fimbrial gene expression in Proteus mirabilis infecting the urinary tract. Mol. Microbiol. 23:1009-1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zunino, P., C. Piccini, and C. Legnani-Fajardo. 1999. Growth, cellular differentiation and virulence factor expression by Proteus mirabilis in vitro and in vivo. J. Med. Microbiol. 48:527-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.