Abstract

The Haemophilus ducreyi 35000HP genome encodes a homolog of the CpxRA two-component cell envelope stress response system originally characterized in Escherichia coli. CpxR, the cytoplasmic response regulator, was shown previously to be involved in repression of the expression of the lspB-lspA2 operon (M. Labandeira-Rey, J. R. Mock, and E. J. Hansen, Infect. Immun. 77:3402-3411, 2009). In the present study, the H. ducreyi CpxR and CpxA proteins were shown to closely resemble those of other well-studied bacterial species. A cpxA deletion mutant and a CpxR-overexpressing strain were used to explore the extent of the CpxRA regulon. DNA microarray and real-time reverse transcriptase (RT) PCR analyses indicated several potential regulatory targets for the H. ducreyi CpxRA two-component regulatory system. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were used to prove that H. ducreyi CpxR interacted with the promoter regions of genes encoding both known and putative virulence factors of H. ducreyi, including the lspB-lspA2 operon, the flp operon, and dsrA. Interestingly, the use of EMSAs also indicated that H. ducreyi CpxR did not bind to the promoter regions of several genes predicted to encode factors involved in the cell envelope stress response. Taken together, these data suggest that the CpxRA system in H. ducreyi, in contrast to that in E. coli, may be involved primarily in controlling expression of genes not involved in the cell envelope stress response.

Haemophilus ducreyi is the etiologic agent of chancroid, a sexually transmitted genital ulcer disease (54, 59). In some resource-poor developing countries of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, chancroid is a very common sexually transmitted infection (reviewed in reference 54). In the United States, chancroid is very rarely seen but outbreaks in urban areas have been documented (23, 40) and this disease may be underreported (52). The public health consequences of chancroid are not insignificant, because the presence of genital ulcers caused by H. ducreyi increases the likelihood of heterosexual transmission of HIV-1 infection (20, 51).

Despite sustained efforts to study the pathogen, chancroid remains one of the least understood infectious diseases (reviewed in references 7, 30, 36, and 54). How the bacterium causes tissue necrosis and retards lesion healing (54) has not been elucidated, and experimental investigation of its virulence mechanisms in vitro has been complicated by the fastidious nature of H. ducreyi. Nonetheless, over the past 15 years, a large number of putative virulence factors of this organism have been identified, including numerous proteins and the lipooligosaccharide (LOS). However, subsequent testing in the human challenge model for experimental chancroid (for a review, see reference 31) revealed that only a few of these gene products are truly essential for full virulence of H. ducreyi. Mutations in pal (21), hgbA (1), dsrA (8), the flp gene cluster (55), ncaA (22), and lspA1 and lspA2 (29) attenuated the virulence of H. ducreyi in human volunteers, whereas mutations in four other genes caused partial attenuation (4, 6, 28, 34).

There is even less information available about the regulatory mechanisms that control expression of virulence-related genes in H. ducreyi. Although H. ducreyi is an obligate human pathogen, this biological fact does not prevent it from having to regulate gene expression. The earliest documented example of gene regulation in H. ducreyi involved a heme acquisition system (18), and in a later study, mutant analysis indicated that inactivation of the lspA1 gene would cause increased expression of the LspA2 protein (61). The use of DNA microarray analysis and real-time reverse transcriptase (RT) PCR showed that several hundred H. ducreyi genes are differentially regulated in the presence of fetal calf serum (FCS), and subsequent experiments revealed that the H. ducreyi CpxR response regulator is involved in negatively controlling expression of the lspB-lspA2 operon (35).

Two-component signal transduction systems (TCSs) typically comprise a membrane-bound sensor (histidine protein) kinase and a cytoplasmic response regulator (for reviews, see references 38, 65, and 69). Upon sensing the appropriate signal, the sensor kinase autophosphorylates a specific histidine residue. The phosphoryl group is then transferred to a specific aspartate residue in the response regulator, which thereupon becomes a transcriptional activator or repressor. TCSs have been shown to control numerous different genes involved in virulence expression, nutrient uptake, motility, and the response of the bacterial cell to stress (49). In Escherichia coli, there are three TCS-based cell envelope stress response systems, including the regulons of BaeSR, regulator of capsule synthesis (RCS), and CpxRA (for a review, see reference 38). Among these TCSs, CpxRA has been the most studied to date (47).

There are now several examples of TCSs that function in other pathogens that naturally infect only humans, including Bordetella pertussis (53), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (42), and N. meningitidis (27). The demonstration of a functional CpxR ortholog in H. ducreyi (35), together with the presence of a closely linked open reading frame (ORF) encoding a predicted CpxA ortholog, led us to construct additional H. ducreyi mutants and recombinant H. ducreyi strains to determine the extent of the CpxRA regulon in H. ducreyi. Our results indicate that, although the H. ducreyi CpxR and CpxA proteins are highly similar to the two E. coli proteins with the same designations, their functions may have evolved to control a set of genes in H. ducreyi that are not involved in the cell envelope stress response. Some of these CpxRA-regulated genes encode proven virulence factors of this pathogen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria and culture conditions.

Strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. H. ducreyi strains were grown on chocolate agar (CA) plates that were incubated at 33°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 95% air and 5% CO2. For broth culture, H. ducreyi strains were grown in a Columbia broth-based medium (62) containing 2.5% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (CB) at 33°C in a gyratory water bath at 100 rpm. Antibiotic selection used with H. ducreyi strains involved chloramphenicol (1 μg/ml) and/or kanamycin (30 μg/ml). E. coli strains including DH5α, TOP10, and HB101 were used for general cloning procedures and were grown in Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with the appropriate antibiotic (ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; kanamycin, 50 μg/ml; or chloramphenicol, 30 μg/ml). E. coli HB101 was transformed with recombinant plasmids derived from pLS88 (66), and the plasmids were then isolated from this strain and introduced by electroporation into H. ducreyi for complementation studies.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| H. ducreyi strains | ||

| 35000HP | Human-passaged H. ducreyi strain | 57 |

| 35000HPΔcpxA | 35000HP ΔcpxA::Cmr | This study |

| 35000HPΔcpxR | 35000HP ΔcpxR::Cmr | 35 |

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH5α | F− φ80lacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169recA1endA1hsdR17(rK− mK+) phoAsupE44 λ−thi-1gyrA96relA1 | Invitrogen |

| TOP10 | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74recA1araD139Δ(ara-leu)7697galUgalKrpsLendA1nupG | Invitrogen |

| HB101 | F−thi-1hsdS20(rB− mB−) supE44recA13ara-14leuB6proA2lacY1galK2rpsL20 (Strr) xyl-5mtl-1 | Promega |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR2.1 | E. coli cloning vector; Ampr | Invitrogen |

| pML117 | pCR2.1 containing a 35000HP cpxA gene with a 1.15-kb deletion | This study |

| pML118C | pML117 with a cat cartridge in the deletion site in cpxA | This study |

| pLS88 | H. ducreyi shuttle vector; Kmr | 66 |

| pML141 | pLS88 containing the wild-type 35000HP cpxA gene | This study |

| pML153 | pL141 with the H253Q substitution in CpxA | This study |

| pML125 | pLS88 containing the wild-type 35000HP cpxR gene | 35 |

| pML154 | pML125 with the D52A substitution in CpxR | This study |

Development of a polyclonal CpxA antiserum.

The peptide DGEGVPESEYKQIFRPFYRVGEAR, corresponding to amino acids 395 to 418 of the H. ducreyi 35000HP CpxA protein, was synthesized by the Protein Technology Center at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. This peptide was covalently coupled to maleimide-activated keyhole limpet hemocyanin (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Immunizations were carried out by Rockland Immunochemicals (Boyertown, PA). SulfoLink coupling resin (Pierce/Thermo Scientific) was used to immobilize the CpxA peptide in order to affinity purify CpxA-specific antibodies from the antiserum. The resulting purified polyclonal CpxA antibody was used at a concentration of 70 ng/ml as a primary antibody in Western blot analysis.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis.

Proteins present in whole-cell lysates (derived from 5 × 107 to 1 × 108 CFU) of the appropriate H. ducreyi strains were resolved by SDS-PAGE in 4 to 20% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide separating gels and electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes as described previously (41). Membranes were then incubated in StartingBlock (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) blocking buffer (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) containing 5% (vol/vol) normal goat serum for 1 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C, after which they were incubated in primary antibody for 3 to 4 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. Membranes were then incubated for 1 h at room temperature in a 1:20,000 dilution of either goat anti-mouse IgG-horseradish peroxidase (IgG-HRP) or goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The LspA1-specific monoclonal antibody (MAb) 40A4 (62), the LspA2-specific MAb 1H9 (62), the PAL-specific MAb 3B9 (56), LspB-reactive polyclonal mouse serum (63), DsrA-reactive polyclonal mouse serum (19), Flp1-reactive polyclonal rabbit serum (41), and CpxR-reactive polyclonal rabbit serum (35) have been described previously. Western blots were developed using the Western Lightning Plus chemiluminescence reagent (New England Nuclear, Boston, MA).

Construction and complementation of an H. ducreyi cpxA mutant.

An ∼1.2-kb fragment corresponding to the 5′ upstream region of the H. ducreyi 35000HP cpxA ORF was PCR amplified from chromosomal DNA with Ex Taq DNA polymerase (Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan) by using primers P1 (35) and P183 (Table 2). A second 1.2-kb fragment corresponding to the 3′ downstream region of the H. ducreyi cpxA ORF was PCR amplified with primers P184 (Table 2) and P2 (35). Primers P183 and P184 carried 24-nucleotide (nt) complementary sequences (Table 2), and a SmaI site (underlined) was included in primer P183. The two PCR fragments were gel purified, and equal amounts were used as the templates in overlapping extension PCR (25) with primers P1 and P2. The resultant 2.4-kb PCR product had a 1,149-bp deletion within the cpxA ORF, with a SmaI site in the center. This fragment was cloned into pCR2.1 (Invitrogen) to obtain pML117. A cat cartridge from pSL1 (37), modified to contain the native cat promoter (35), was digested with SmaI and ligated to SmaI-digested pML117 to obtain pML118C. Primers P1 and P2 were used to amplify an ∼3.2-kb fragment from pML118C containing the cpxA deletion construct described above. The amplicon was DpnI digested to cut any residual plasmid DNA and then subjected to gel purification. Different amounts of the purified PCR fragment (5 to 100 μg) were used for electroporation of H. ducreyi 35000HP as described previously (35). PCR followed by nucleotide sequence analysis was used to confirm that the desired deletion was in frame in the resultant chloramphenicol-resistant H. ducreyi 35000HPΔcpxA mutant. Complementation of the H. ducreyi 35000HPΔcpxA mutant was performed as follows: a 100-ng quantity of pML141 (described below) was used for electroporation of 35000HPΔcpxA to obtain the kanamycin- and chloramphenicol-resistant strain 35000HPΔcpxA(pML141).

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Primer name | Sequence (5′-3′)a |

|---|---|

| Primers for construction of mutants | |

| P183 | ACCACCACTTTGAGGGTCACGTG CCCCGGGAATAGCTAACATA ATAGCAAATGT |

| P184 | GCACGTGACCGTCAAAGTGGTGGT |

| P298 | ACGCCCGCGGAAGCTTAATGT ATTAAATTAT |

| P299 | ACGCCCGCGGAGATGTTAATG CATAACCCTG |

| P464 | CGCGCGGTTGAGCTCCCTA TCAT |

| P465 | CATTAACAGGAGCTCGTTCG TGCC |

| Primers for real-time RT-PCR | |

| HD0281F | TCGTTGAGGCTGCTTGTAGT |

| HD0281R | AAAGGTGGAACATCTCGTCC |

| HD1629F | CAAGCAGGATCGGTATGTTC |

| HD1629R | TAACGCCATAGCCATCAGAG |

| HD1160F | TAGCCACGTGTTAGGCATTC |

| HD1160R | CTTTACGATTACGGGTTGCA |

| HD0472F | ATGCGCGTAGGCAACATA |

| HD0472R | TGAGCCACTTCTTATTGTGGA |

| HD0312F | CCTTTGGTGCTGCAGTTAGA |

| HD0312R | TCGTATTGTTGTGGTGCATG |

| HD0564F | GGATTTACTCGGCGAAAGAG |

| HD0564R | CCATACCACGGACAAATTCA |

| HD0850F | ATTGACGTGGCATACCAGAA |

| HD0850R | CTGCTGTGCTGTTCTCACAA |

| HD0405F | AAAGATCCGCTACTGGCATT |

| HD0405R | TGTGCGCTACAATTTGTTCA |

| HD0903F | TGCAGTAGGTATCCGCATTG |

| HD0903R | GCACGATTGAAATCACCAAC |

| HD0998F | TAGCCGCTTCTTTGGGTAAT |

| HD0998R | TGAGTGAAGCCCGTAATCTG |

| HD0349F | GTTGTACGGCGTGTATGGAG |

| HD0349R | CACCTTGTGTTGCGGTATGT |

| HD1326F | CGGGTTAATGGGTTTATTGG |

| HD1326R | CCCAAATGGAGCATATCAGA |

| HD2013F | AGGTTCAGCGGGTAAATC |

| HD2013R | ATATCTTTGCCTTGCGCTTT |

| HD0765F | GCTAATTTGCCACACGCTTA |

| HD0765R | CCGGAATATCAACCCATTTC |

| HD0266F | GGTACCATCGTTTCAATTCGT |

| HD0266R | TAAGGCACGTCCAGTACCAC |

| HD0189F | TTGCACACGCTACACGTAAA |

| HD0189R | TAGCTTGAGCAGCTTGCATT |

| HD0815F | CGGAACAAGTTACCAAGCAA |

| HD0815R | TTCACCACCAGATGCAATTT |

| HD0812F | CGAAATTGTTGGGTTTGATG |

| HD0812R | CTTGCTTCATTCGTGCATCT |

| HD1076F | AGCGTTAGTGCGTTGGTATG |

| HD1076R | TGCAAACCCTTAGCTTTGTG |

| HD1186F | GGCGAACAAGCTATTTGTGA |

| HD1186R | TTGTTTGCCTGCCTTAACTG |

| HD1456F | GACACGTTCGGGTGATATTG |

| HD1456R | GACGAGCAGCATCATCAGTT |

| HD0436F | CCACTTTAATTGGCGGAGAT |

| HD0436R | TCCTATGGTGCCAGAAACAA |

| HD1468F | TGGATCTTCACCTGATTCCA |

| HD1468R | CCTCTGCCGTCATTATCAAA |

| Primers for EMSAs | |

| HD1433P(F) | TTAAGCATTTTTATTTACTTT |

| HD1433P(R) | GCAAGCAAACGTAGTGAGCCA |

| HD1312P(F) | AAACCGATCTGGTCTAACCAG |

| HD1312P(R) | AAATATAAAATAAATTATGTT |

| HD0281P(F) | AATACTCTAATCAAGTTGACGT |

| HD0281P(R) | GCTGATATACTTATTGTTCCC |

| HD0046P(F) | TTTTTATTTTGCAAATTATAC |

| HD0046P(R) | TTCCATTTTAATTTTCCTCTA |

| HD0769P(F) | TGAATTGGAGTGGACCAGGAC |

| HD0769P(R) | ATAGTAGAACAAGCTAATCCC |

| HD0260P(F) | ATGGTGAAAAATTCACCGCTT |

| HD0260P(R) | ACACTTAAACCTAAGACTAAT |

| HD0638P(F) | TACATCTGATTGATATT |

| HD0638P(R) | TTCATTAGTGTTCCTTAA |

| HD1788P(F) | TTCATTAGCCCGTAATACGAT |

| HD1788P(R) | ATGTTTAAATAAACTCATTAA |

| HD2025P(F) | ATTAAAAACAATAGTACTTA |

| HD2025P(R) | GTTTGCATATTGCTTTCGGCA |

| HD1737P(F) | CAGGGTTGATAATACATCAAT |

| HD1737P(R) | ACTAACGCAAAAAATAAC TTTA |

| HD0649P(F) | ATTCAGTATGCCTAATCCTAT |

| HD0649P(R) | CTTTTTCAGTATGTTCATAAT |

Bold text indicates complementary sequences for use in overlapping extension PCR. Underlining indicates restriction sites as described in Materials and Methods.

Recombinant plasmids and site-directed mutagenesis.

Plasmid pML125, carrying the wild-type cpxR gene from H. ducreyi 35000HP, has been described previously (35). To construct a plasmid containing the cpxA gene, the wild-type cpxA gene from H. ducreyi 35000HP together with 268 nt upstream of the translational initiation codon was PCR amplified from chromosomal DNA by using primers P299 and P298 (Table 2). The 1,677-bp amplicon was digested with SacII and ligated to SacII-digested pLS88 (16) to obtain pML141.

Based on sequence homology to well-characterized CpxR and CpxA proteins from enteric bacteria, site-directed mutagenesis with the QuikChange kit (Stratagene) was used to make the following changes in the putative residues involved in phosphotransfer: D52A in CpxR and H253Q in CpxA. For PCR amplification, 50 ng of template pML125 or pML141 DNA was used. The resultant plasmids carrying the mutated cpxR (i.e., pML154) or cpxA (i.e., pML153) gene were verified by nucleotide sequencing. Plasmids carrying the desired mutations were used for electroporation of 35000HPΔcpxR or 35000HPΔcpxA as described previously (35).

Autoagglutination assay.

The abilities of H. ducreyi strains to autoagglutinate were evaluated as described previously (61) with some modifications. Briefly, bacterial cells grown on CA plates were used to inoculate 10 ml of CB, and the cells were grown overnight (∼16 h). These cells were diluted in fresh Columbia broth to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of ∼0.7 in Klett colorimeter tubes, which were then allowed to remain static at room temperature. The absorbance of the suspensions was measured every 30 min for 3 h.

RNA purification and DNA microarray analysis.

The RiboPure bacterial kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) was used to isolate total RNA from broth-grown cultures after 8 h of growth as described previously (35). After RNA isolation, the purity of samples was determined by PCR using oligonucleotide primers specific for gyrB (35) to detect possible DNA contamination. Quality assessment was performed using the Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies), which reported RNA integrity numbers (RINs) between 7.8 and 10 for all the samples used. The H. ducreyi custom-spotted DNA microarrays used in this study have been described previously (35). For each experiment, 5- to 20-μg quantities of total RNA extracted from cells grown to mid-exponential phase were used for first-strand cDNA synthesis as described previously (35). To avoid gene-specific dye bias, each sample was subjected to reverse labeling (i.e., a dye swap). Differential expression was defined as a minimum of a 2-fold change in expression in the H. ducreyi 35000HP ΔcpxA mutant relative to that in the wild-type H. ducreyi 35000HP or in H. ducreyi 35000HP ΔcpxR(pML125) relative to that in H. ducreyi 35000HP ΔcpxR(pLS88). The data were further analyzed so as to include only expression profiles that had a P value of ≤0.05 after a one-sample t test analysis.

Real-time RT-PCR.

Oligonucleotide primers used to amplify ORFs HD2025, HD1643, HD1312, HD0045, HD0046, HD1433, HD0769, and HD0902 were described previously (35); all others are listed in Table 2. Eighteen genes from each of the DNA microarray experiments were randomly selected for further confirmation of their relative transcription levels by two-step real-time RT-PCR. The reverse transcriptase reaction was performed as described previously (35). Assays were performed on three independent biological replicates, using HD1643 (gyrB) to normalize the amount of cDNA per sample. The fold change for each gene was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

The ability of purified recombinant CpxR to bind H. ducreyi promoters was examined by using the digoxigenin (DIG) gel shift kit from Roche as described previously (35), with the lspA1 and gyrB promoter regions being used as negative controls and the lspB promoter region being used as a positive control in each experiment. DNA promoter regions containing the putative consensus CpxR binding sequence in the center of the fragments (∼200 bp) were generated by PCR (relevant primer sequences are shown in Table 2).

Microarray data accession numbers.

The data from the DNA microarray experiments were deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession numbers GSE21788 and GSE21789.

RESULTS

Probable structural features of H. ducreyi CpxA and CpxR proteins.

A simple BLAST search (2) using the product of H. ducreyi gene HD1470 returns other CpxA proteins, with the closest homolog being CpxA of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae (78% identity; E value, 0.0). Structural motifs present in H. ducreyi CpxA mark it as the sensor/histidine kinase component of a TCS. No crystal structure for a CpxA protein is known, but a combination of secondary-structure prediction and comparison to known histidine kinase (HK) structures indicates that this CpxA has a short, cytoplasmic part (amino acids [aa] 1 to 17), followed by a transmembrane helix (aa 18 to 38). Residues 39 to 168 comprise a periplasmic domain with mixed secondary structures and probably serve as the sensor (the ligand is unknown). Residues 169 to 188 make up the final transmembrane helix. The cytoplasmic C-terminal domain of this CpxA can be characterized by its similarities to known nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and crystal structures. As examples, sequence alignments that take known structures of other proteins and the secondary-structure predictions (44) for H. ducreyi CpxA into account indicate that the C terminus of this protein is likely to have a structure similar to those of sensor proteins. In H. ducreyi CpxA, aa 189 to 242 likely comprise a so-called HAMP domain (3), which bridges the second transmembrane helix of the protein to the dimerization domain (aa 243 to 303). This conclusion is based on its alignment to the HAMP domain of Af1503 from Archaeoglobus fulgidus, the NMR structure of which is known (26). The alignment demonstrates 25% identity and strong conservation of secondary structure between the two proteins (data not shown). H253 is the first residue in the H box (aa 253 to 301) and is the essential residue that serves as an intermediate phosphoreceptor once the protein becomes activated by a stimulus. Residues 304 to 464 comprise the C-terminal ATP binding domain. To examine the likely structure of this domain of CpxA, it is most instructive to compare it to the C-terminal domain of HK853 from Thermotoga maritima, the crystal structure of which was recently determined (39). A sequence alignment demonstrates that the two domains have approximately 23% identity and that the secondary structures of the two proteins are highly correlated (data not shown). Given the significant correspondence between the two proteins, it is likely that they have similar three-dimensional structures.

The HD1469 gene encodes a 240-aa protein with homology to CpxR proteins which are the response regulators in TCSs. The protein with the highest level of homology (90% identity; E value, 4 × 10−113) is CpxR of A. pleuropneumoniae. Comparing H. ducreyi CpxR to other response regulators indicates that this CpxR has two domains: an N-terminal receiver domain (aa 1 to 116) and a C-terminal effector domain (aa 141 to 240). Between these two domains, there is a connector region (aa 117 to 140) that is predicted to have no regular secondary structure. In the receiver domain, the residue (D52) necessary for phosphoryl transfer from CpxA is conserved. An analysis of the primary sequence of and the secondary-structure prediction for H. ducreyi CpxR (data not shown) aligned to the sequence of the receiver domain of the structurally characterized YycF from Bacillus subtilis (Protein Data Bank [PDB] accession number 2ZWM) indicates that this domain is 50% identical to that of H. ducreyi CpxR, suggesting that the structures of the two proteins are likely to be very similar. The C-terminal domain of H. ducreyi CpxR very likely binds to DNA, given its sequence homology to other effector domains that have this function. By using a structure-assisted sequence alignment (44), the sequence of the E. coli PhoB effector domain was compared to that of H. ducreyi CpxR (revealing 33% identity). Nearly every amino acid residue in E. coli PhoB that makes sequence-independent contacts with DNA is identical to the corresponding residue in H. ducreyi CpxR, with a few exceptions which suggest that H. ducreyi CpxR does not bind to the same DNA sequences as PhoB (data not shown). The high level of sequence similarity between these two effector domains implies that they share a common fold.

Characterization of an H. ducreyi cpxA deletion mutant.

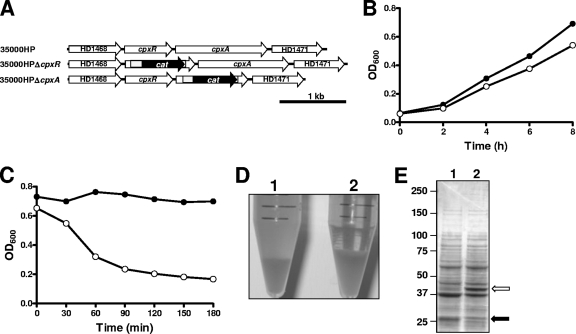

Deletion of cpxA from H. ducreyi 35000HP (see Materials and Methods) (Fig. 1 A) did not result in a significant growth defect, although the apparent density of the mutant culture was slightly lower than that of the wild-type parent strain culture after 8 h (Fig. 1B). This difference may have been the result of increased autoagglutination exhibited by the cpxA mutant (Fig. 1C and D). In addition, the overall total protein profile of this cpxA mutant was significantly different from that of the wild-type parent strain (Fig. 1E). Mass spectrometric analysis indicated that the ∼40-kDa protein that was much more highly expressed by the cpxA mutant was OmpP2B (46). This same type of analysis revealed that the ∼27-kDa protein that was present in the wild-type parent strain and apparently missing in the cpxA mutant was DsrA (19), a proven virulence factor of this pathogen (8).

FIG. 1.

Characterization of the H. ducreyi cpxA deletion mutant. (A) Schematic of the cpxRA locus in the wild-type strain 35000HP, the 35000HPΔcpxR deletion mutant (35), and the 35000HPΔcpxA deletion mutant. (B) Growth of the wild-type parent strain 35000HP (closed circles) and the cpxA deletion mutant (open circles) in broth. Results from a representative experiment are shown. (C) Autoagglutination rates for the wild-type parent strain 35000HP (closed circles) and the cpxA deletion mutant (open circles). (D) Photograph of suspensions of the wild-type parent strain 35000HP (1) and the cpxA deletion mutant (2) after 3 h (at the end of the autoagglutination assay for which results are presented in panel C). (E) Total cell protein profiles for the wild-type parent strain 35000HP (lane 1) and the cpxA deletion mutant (lane 2) as determined by resolving proteins by SDS-PAGE and staining with Coomassie blue. The white arrow indicates the OmpP2B protein, which is overexpressed in the mutant, and the black arrow indicates the DsrA protein, which is present in the wild-type strain and missing in the mutant.

Deletion of cpxA affects expression of H. ducreyi gene products involved in virulence.

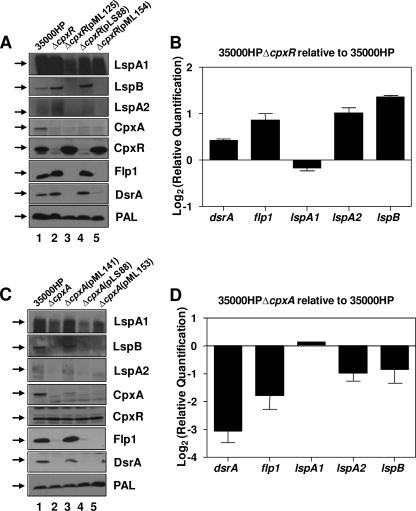

In a previous study (35), CpxR, the response regulator in the CpxRA two-component regulatory system, was shown to be a repressor of the H. ducreyi lspB-lspA2 operon and to have no apparent direct effect on the expression of lspA1 (Fig. 2 A, lane 2, and B). Many histidine kinases are known to have phosphatase activity toward their cognate response regulators. A deletion of the sensor kinase should therefore result in the inability of the response regulator to be dephosphorylated, assuming that the regulator could be phosphorylated by other small phosphodonors such as acetyl phosphate (32, 67, 68). Using both real-time RT-PCR and Western blot analyses, we showed that deletion of the cpxA ORF resulted in the reduction of expression of both lspB-lspA2 transcripts (Fig. 2D) and the respective encoded proteins (Fig. 2C, lane 2). These results would be consistent with the presence of high levels of phosphorylated CpxR in the cpxA mutant, especially because the apparent level of CpxR protein in this cpxA mutant (Fig. 2C, lane 2) was equivalent to that in the wild-type parent strain (Fig. 2C, lane 1). Based on these results, it is our working assumption that the CpxR protein of this H. ducreyi cpxA deletion mutant is constitutively phosphorylated and it will be referred to as such for the remainder of this study.

FIG. 2.

Deletion of cpxA or cpxR results in dysregulation of expression of several H. ducreyi gene products involved in virulence. H. ducreyi strains grown for 8 h in CB were used for preparation of whole-cell lysates or for RNA extraction. (A) Western blot analysis of whole-cell lysates of 35000HP (lane 1), 35000HPΔcpxR (lane 2), 35000HPΔcpxR(pML125) (lane 3), 35000HPΔcpxR(pLS88) (lane 4), and 35000HPΔcpxR(pML154) (lane 5); primary antibodies are indicated to the right of each panel. The PAL monoclonal antibody 3B9 (56) was used as a loading control for both panels A and C. It should be noted here that both LspA1 and LspA2 typically appear diffuse or exhibit a multiple banding pattern in Western blot analysis (35, 61). Black arrows on the left in panels A and C indicate the position of the relevant antigen. (B) Real-time RT-PCR showing transcript levels for dsrA, flp1, lspA1, lspA2, and lspB in 35000HPΔcpxR relative to 35000HP. (C) Western blot analysis of 35000HP (lane 1), 35000HPΔcpxA (lane 2), 35000HPΔcpxA(pML141) (lane 3), 35000HPΔcpxA(pLS88) (lane 4), and 35000HPΔcpxA(pML153) (lane 5); primary antibodies are indicated to the right of each panel. (D) Real-time RT-PCR showing transcript levels for dsrA, flp1, lspA1, lspA2, and lspB in 35000HPΔcpxA relative to 35000HP.

Expression of the flp1 and dsrA genes (Fig. 2D) and their respective encoded protein products (Fig. 2C, lane 2) was also reduced in this cpxA mutant. The absence of CpxA also resulted in a reduction in the levels of LspA1 protein (Fig. 2C, lane 2), but the lspA1 transcript levels remained essentially unchanged (Fig. 2D). This result is consistent with the hypothesis that the effect of the CpxRA regulatory system on LspA1 expression is not direct (35). Provision of a wild-type H. ducreyi cpxA gene in trans (Fig. 2C, lane 3) lifted the repression of expression of the LspB, LspA2, Flp1, and DsrA proteins (Fig. 2C, lane 3), even though expression of CpxA in this recombinant strain (Fig. 2C, lane 3) was substantially lower than that in the wild-type parent strain (Fig. 2C, lane 1). This complemented cpxA mutant also exhibited a wild-type autoagglutination phenotype (data not shown).

Effects of site-directed mutations in cpxR and cpxA.

As discussed previously, H253 in CpxA and D52 in CpxR are likely to be the conserved sites for phosphotransfer between this sensor kinase and its response regulator. A D52A substitution in CpxR (encoded by pML154) (Fig. 2A, lane 5) did not result in an increase in expression of LspB, LspA2, Flp1, or DsrA relative to that in the recombinant strain containing the wild-type cpxR gene in trans (Fig. 2A, lane 3), raising the possibility that the overexpression of the mutated CpxR protein observed in this recombinant strain (Fig. 2A, lane 5) might overcome the need for phosphorylation of CpxR (12). Surprisingly, the expression of LspA1 was restored to near wild-type levels (Fig. 2A, lane 5) by overexpression of this mutated CpxR protein. This observation, together with the above data indicating a possible posttranscriptional/translational effect of CpxR on expression of LspA1, suggests that a factor(s) downstream of CpxR requires the phosphorylated state of CpxR for activity.

An H253Q substitution in CpxA (encoded by pML153), which should abolish its kinase activity but maintain its ability to dephosphorylate CpxR (50), did not relieve the repression of expression of LspB, LspA2, Flp1, and DsrA (Fig. 2C, lane 5). It must be noted that the expression of the mutant (H253Q) CpxA protein in the complemented cpxA mutant (Fig. 2C, lane 5) was much lower than that of wild-type CpxA in the wild-type strain (Fig. 2C, lane 1) or in the complemented cpxA mutant carrying the wild-type cpxA gene in trans (Fig. 2C, lane 3). These observed very low levels of CpxA expression in these two recombinant strains could result in relatively high levels of CpxR phosphorylation, which would explain why LspB, LspA2, Flp1, and DsrA are still repressed in both of these strains (Fig. 2C, lanes 3 and 5). The very low level of expression of wild-type CpxA and CpxA(H253Q) in these two complemented strains may be related to potential toxicity issues involved in attempted overexpression of an integral membrane protein.

The H. ducreyi CpxRA regulon.

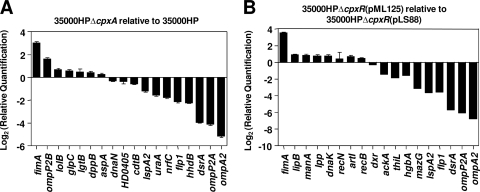

To identify members of the H. ducreyi CpxRA regulon, DNA microarray analysis was initially performed with wild-type H. ducreyi 35000HP and the isogenic cpxR mutant. As observed in similar studies performed with E. coli (47), inactivation of the response regulator (i.e., cpxR) did not have much effect on overall gene expression (data not shown). With the working assumption that a cpxA deletion mutant should have a highly phosphorylated CpxR protein (10, 32, 68), we next compared the global expression profile of the wild-type strain with that of the cpxA mutant. Regulated genes were defined as those with a minimum 2-fold transcriptional change (P < 0.05). One hundred eighty-one genes were found to be differentially regulated (108 were upregulated and 73 were downregulated) in the cpxA mutant background (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). To validate the DNA microarray results, real-time RT-PCR was performed with a set of selected genes (Fig. 3 A) which showed a correlation coefficient R2 of 0.9648.

FIG. 3.

Real-time RT-PCR analysis of selected gene expression in mutant and recombinant strains of H. ducreyi. (A) Genes in 35000HPΔcpxA exhibiting upregulation, downregulation, or no change relative to those in 35000HP in a DNA microarray analysis were analyzed by real-time RT-PCR. (B) Genes in 35000HPΔcpxR(pML125) exhibiting upregulation, downregulation, or no change relative to those in 35000HPΔcpxR(pLS88) in a DNA microarray analysis were analyzed by real-time RT-PCR. These data are the means of results from three independent experiments.

We also compared the overall gene expression in 35000HPΔcpxR carrying a wild-type cpxR gene in trans [35000HPΔcpxR(pML125)] to that in the same mutant carrying the empty plasmid vector [35000HPΔcpxR(pLS88)]. The former strain overexpressed CpxR (Fig. 2A, lane 3), a condition that may overcome the need to have CpxR phosphorylated, as described previously for E. coli (12). Under this condition of overexpression of CpxR, a total of 224 genes were differentially expressed, with 90 genes being upregulated and 134 being downregulated (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). A subset of these genes was used to validate the DNA microarray data by using real-time RT-PCR (Fig. 3B), and a correlation coefficient R2 of 0.9302 was obtained.

A comparison of the two sets of DNA microarray data revealed 116 genes in common (Table 3 lists the 30 most up- and downregulated genes). The most highly upregulated genes in both groups were those of the putative fimbrial operon fimABCD, and the most downregulated were ompA2, ompP2A, members of the flp operon, and dsrA. The high level of similarity between the expression profile results from these two comparisons [the cpxA mutant versus the wild type and 35000HPΔcpxR(pML125) versus 35000HPΔcpxR(pLS88)] supports our hypothesis that CpxR is highly active in both situations, due to constitutive phosphorylation of CpxR in the former case and to overexpression of CpxR in the latter.

TABLE 3.

Genes whose expression was most affected by the constitutive phosphorylation and overexpression of CpxR as measured by DNA microarray analysisa

| ORF | Gene | Description of gene product | Value from comparison of 35000HP ΔcpxA to 35000HP |

Value from comparison of 35000HP ΔcpxR(pML125) to 35000HP ΔcpxR(pLS88) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median log2ratio of expression levelsb | SDc | Median log2ratio of expression levelsd | SDe | |||

| HD0281 | fimA | Possible fimbrial major pilin protein | 3.47 | 1.05 | 3.62 | 0.41 |

| HD0282 | fimB | Possible fimbrial structural subunit | 3.01 | 0.32 | 3.16 | 0.41 |

| HD0283 | fimC | Probable fimbrial outer membrane usher protein | 2.55 | 0.54 | 2.80 | 0.41 |

| HD1109 | Putative oxalate/formate antiporter | 2.41 | 0.06 | 3.90 | 0.25 | |

| HD0284 | fimD | Probable periplasmic fimbrial chaperone | 2.29 | 0.08 | 2.27 | 0.31 |

| HD1512 | Acriflavine resistance protein | 2.20 | 0.14 | 2.12 | 0.41 | |

| HD1163 | ribAB | Riboflavin biosynthesis protein RibA | 2.19 | 0.52 | 1.56 | 0.30 |

| HD1165 | ribH | 6,7-Dimethyl-8-ribityllumazine synthase | 1.82 | 0.14 | 1.28 | 0.25 |

| HD1161 | ribD | Riboflavin-specific deaminase | 1.73 | 0.20 | 1.58 | 0.31 |

| HD1513 | Putative RND efflux membrane fusion protein | 1.69 | 0.15 | 1.44 | 0.34 | |

| HD0313 | dppC | Dipeptide transport system permease protein | 1.66 | 0.16 | 1.20 | 0.23 |

| HD1084 | HesB family protein | 1.66 | 0.12 | 1.59 | 0.29 | |

| HD1142 | sdaA | l-Serine dehydratase | 1.65 | 0.54 | 1.44 | 0.28 |

| HD0765 | manA | Mannose-6-phosphate isomerase | 1.62 | 0.05 | 1.39 | 0.33 |

| HD0812 | artI | Arginine ABC transporter; periplasmic binding protein | 1.61 | 0.21 | 1.60 | 0.31 |

| HD1511 | glmU | Bifunctional GlmU protein | 1.50 | 0.08 | 0.96 | 0.23 |

| HD0351 | prfC | Peptide chain release factor 3 | 1.42 | 0.16 | 1.65 | 0.23 |

| HD1007 | bioB | Biotin synthetase | 1.39 | 0.12 | 0.89 | 0.24 |

| HD0564 | aspA | Aspartate ammonia-lyase | 1.37 | 0.05 | 2.11 | 0.33 |

| HD2012 | lipA | Lipoic acid synthetase | 1.36 | 0.20 | 1.60 | 0.38 |

| HD0766 | manZ | Mannose-specific phosphotransferase system IID component | 1.32 | 0.08 | 1.40 | 0.25 |

| HD1146 | glpF | Glycerol uptake facilitator protein | 1.30 | 0.06 | 1.11 | 0.33 |

| HD2017 | Possible rare lipoprotein A | 1.29 | 0.06 | 1.72 | 0.23 | |

| HD2016 | dacA | Penicillin binding protein 5 | 1.27 | 0.08 | 2.02 | 0.28 |

| HD0767 | manY | Mannose-specific phosphotransferase system IIC component | 1.23 | 0.08 | 1.41 | 0.26 |

| HD0404 | lpxM | Lipid A acyltransferase | 1.20 | 0.13 | 1.09 | 0.22 |

| HD1085 | hscB | Chaperone protein HscB | 1.17 | 0.10 | 0.94 | 0.24 |

| HD1353 | ihfB | Integration host factor, beta subunit | 1.14 | 0.16 | 0.93 | 0.21 |

| HD0449 | fis | DNA binding protein | 1.12 | 0.16 | −1.02 | 0.19 |

| HD0300 | grxA | Glutaredoxin | 1.11 | 0.14 | 0.79 | 0.24 |

| HD1156 | lspA2 | Large supernatant protein 2 | −1.19 | 0.12 | −2.95 | 0.20 |

| HD1304 | tadA | Tight adherence protein A | −1.20 | 0.12 | −1.80 | 0.19 |

| HD1327 | hhdA | Hemolysin | −1.25 | 0.06 | −1.20 | 0.11 |

| HD1480 | bioD1 | Probable dethiobiotin synthetase | −1.28 | 0.07 | −1.66 | 0.30 |

| HD1857 | sgaH | Probable hexulose-6-phosphate synthase | −1.29 | 0.05 | −1.21 | 0.21 |

| HD1503 | guaB | Inosine-5-monophosphate dehydrogenase | −1.31 | 0.05 | −2.43 | 0.17 |

| HD1305 | flpD | flp operon protein D | −1.39 | 0.09 | −1.88 | 0.17 |

| HD1291 | gapA | Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase | −1.41 | 0.13 | −1.10 | 0.26 |

| HD1986 | fumC | Fumarate hydratase class II | −1.46 | 0.05 | −1.68 | 0.22 |

| HD1290 | msrB | Peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase MsrB | −1.50 | 0.11 | −1.57 | 0.31 |

| HD1389 | moaE | Molybdopterin converting factor subunit 2 | −1.50 | 0.56 | −2.03 | 0.15 |

| HD1306 | rcpB | Rough colony protein B | −1.53 | 0.13 | −2.16 | 0.20 |

| HD1280 | Possible serine protease homolog | −1.63 | 0.11 | −1.94 | 0.29 | |

| HD1390 | moaD | Molybdopterin converting factor subunit 1 | −1.66 | 0.62 | −2.41 | 0.17 |

| HD1307 | rcpA | Rough colony protein A | −1.83 | 0.20 | −2.26 | 0.16 |

| HD0347 | nrfB | Nitrate reductase; cytochrome c-type protein | −1.92 | 0.25 | −1.94 | 0.32 |

| HD1308 | flpC | flp operon protein C | −2.06 | 0.09 | −2.37 | 0.17 |

| HD0344 | nrfA | Nitrate reductase; cytochrome c552 | −2.12 | 0.19 | −2.11 | 0.33 |

| HD1309 | flpB | flp operon protein B | −2.43 | 0.45 | −2.95 | 0.22 |

| HD1278 | Possible serine protease | −2.51 | 0.87 | −2.92 | 0.26 | |

| HD0896 | cysK | Cysteine synthase | −2.56 | 0.12 | −3.92 | 0.23 |

| HD1312 | flp1 | flp operon protein Flp1 | −2.85 | 0.94 | −2.51 | 0.28 |

| HD0998 | uraA | Uracil permease | −2.92 | 0.26 | −2.27 | 0.42 |

| HD1310 | flp3 | flp operon protein Flp3 | −3.10 | 0.66 | −3.37 | 0.39 |

| HD1311 | flp2 | flp operon protein Flp2 | −3.11 | 0.71 | −3.66 | 0.35 |

| HD1985 | Possible DNA transformation protein | −3.16 | 0.61 | −2.31 | 0.44 | |

| HD0233 | carB | Carbamoyl-phosphate synthase, large subunit | −3.34 | 0.21 | −2.72 | 0.50 |

| HD0235 | carA | Carbamoyl-phosphate synthase, small subunit | −3.63 | 0.26 | −3.21 | 0.52 |

| HD0769 | dsrA | Serum resistance protein DrsA | −3.68 | 0.15 | −4.38 | 0.32 |

| HD0046 | ompA2 | Major outer membrane protein homolog | −4.61 | 0.10 | −5.72 | 0.21 |

| HD1433 | ompP2A | Outer membrane protein P2 homolog | −4.68 | 0.35 | −3.49 | 0.43 |

The table includes the top 30 most up- or downregulated ORFs and does not include ORFs described as encoding hypothetical or conserved hypothetical proteins.

Median log2 ratio of expression levels from comparisons of 35000HPΔcpxA to 35000HP in three independent experiments (P < 0.05).

SD for the 35000HPΔcpxA data set versus the 35000HP data set.

Median log2 ratio of expression levels from comparisons of 35000HPΔcpxR(pML125) to 35000HPΔcpxR(pLS88) in three independent experiments (P < 0.05).

SD for the 35000HPΔcpxR(pML125) data set versus the 35000HPΔcpxR(pLS88) data set.

In addition to the large number of genes whose expression was affected by both constitutive phosphorylation and overexpression of CpxR (Table 3, columns giving median log2 ratios of expression levels), there were several genes whose expression was affected only by the constitutive phosphorylation of CpxR in the cpxA mutant (Table 4) or only by the overexpression of CpxR (Table 5). The gene whose expression was the most highly upregulated under conditions in which CpxR is constitutively phosphorylated was ompP2B (Table 4). It should be noted that protein analysis also showed that the OmpP2B protein was overexpressed by this H. ducreyi cpxA deletion mutant (Fig. 1E).

TABLE 4.

Genes whose expression was most affected by constitutively phosphorylated CpxR as measured by DNA microarray analysisa

| ORF | Gene | Description of gene product | Median log2ratio of expression levelsb | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HD1435 | ompP2B | Outer membrane protein P2 homolog | 2.30 | 0.15 |

| HD1590 | deaD | Cold shock DEAD box protein A | 2.13 | 0.15 |

| HD0386 | apbE | Thiamine biosynthesis lipoprotein | 1.88 | 0.05 |

| HD1162 | ribE | Riboflavin synthase, alpha chain | 1.78 | 0.13 |

| HD0312 | dppB | Dipeptide transport system permease protein | 1.74 | 0.17 |

| HD1629 | lolB | Outer membrane lipoprotein LolB | 1.67 | 0.15 |

| HD0792 | ccmF | Cytochrome c-type biogenesis protein | 1.57 | 0.17 |

| HD1179 | ksgA | Dimethyladenosine transferase | 1.56 | 0.57 |

| HD0634 | accB | Biotin carboxyl carrier protein of acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) carboxylase | 1.48 | 0.17 |

| HD0635 | accC | Biotin carboxylase | 1.46 | 0.11 |

| HD0068 | ftpA | Fine tangled pilus major subunit | −1.19 | 0.08 |

| HD1077 | ogt | Methylated-DNA-protein-cysteine S methyltransferase | −1.25 | 0.07 |

| HD1326 | hhdB | Hemolysin activation/secretion protein | −1.37 | 0.44 |

| HD1525 | gam | Putative mu phage host nuclease inhibitor protein | −1.38 | 0.10 |

| HD0740 | hflX | GTP binding protein HflX | −1.46 | 0.12 |

| HD1391 | moaC | Molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis protein C | −1.57 | 0.55 |

| HD1392 | moaA | Molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis protein A | −1.80 | 0.52 |

| HD0232 | arcB1 | Ornithine carbamoyltransferase | −3.10 | 0.13 |

The table does not include ORFs described as encoding hypothetical or conserved hypothetical proteins.

Median log2 ratio of expression levels from comparisons of 35000HPΔcpxA to 35000HP in three independent experiments (P < 0.05).

TABLE 5.

Genes whose expression was most affected by overexpression of CpxR as measured by DNA microarray analysisa

| ORF | Gene | Description of gene product | Median log2ratio of expression levelsb | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HD0262 | argR | Arginine repressor | 2.46 | 0.32 |

| HD0025 | dcuB1 | Anaerobic C4-dicarboxylate transporter | 2.24 | 0.30 |

| HD0811 | artP | Arginine ABC transporter; ATP binding protein | 2.16 | 0.67 |

| HD1814 | Probable transport protein | 1.89 | 0.17 | |

| HD0285 | Possible minor fimbrial subunit | 1.86 | 0.17 | |

| HD0266 | lpp | 15-kDa outer membrane lipoprotein | 1.55 | 0.24 |

| HD0565 | clpB | ATP-dependant Clp protease chain B | 1.51 | 0.18 |

| HD0337 | rluB | Probable pseudouridylate synthase | 1.49 | 0.22 |

| HD0988 | prlC | Oligopeptidase A | 1.39 | 0.19 |

| HD1076 | recB | Exodeoxyribonuclease V, beta subunit | 1.31 | 0.17 |

| HD1301 | tadD | Tight adherence protein D | −1.75 | 0.12 |

| HD1300 | tadE | Tight adherence protein E | −1.78 | 0.22 |

| HD1303 | tadB | Tight adherence protein B | −1.80 | 0.21 |

| HD1504 | guaA | GMP synthase (glutamine hydrolyzing) | −1.92 | 0.25 |

| HD0577 | selD | Selenide; water dikinase | −1.99 | 0.16 |

| HD1407 | efp | Elongation factor P | −2.03 | 0.15 |

| HD1150 | glpT | Glycerol 3-phosphate transporter | −2.18 | 0.20 |

| HD1394 | torZ | Trimethylamine-N-oxide reductase 2 | −2.20 | 0.16 |

| HD0202 | slyD | FK506 binding protein (FKBP)-type peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase | −2.31 | 0.14 |

| HD1900 | fkpA | FKBP-type peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase FkpA | −2.61 | 0.15 |

The table does not include ORFs described as encoding hypothetical or conserved hypothetical proteins.

Median log2 ratio of expression levels from comparisons of 35000HPΔcpxR(pML125) to 35000HPΔcpxR(pLS88) in three independent experiments (P < 0.05).

H. ducreyi CpxR directly interacts with the promoter regions of genes encoding proven and putative H. ducreyi virulence factors.

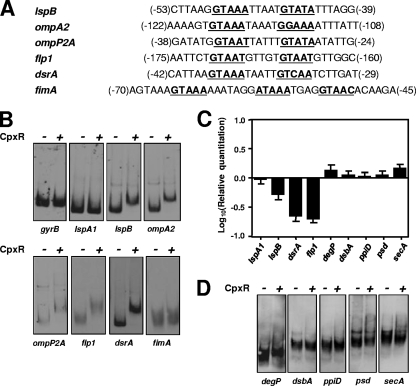

DNA microarray data only allowed us to infer that these particular genes can be controlled, directly or indirectly, by CpxR. In order to establish a more direct relationship, a subset of genes common to both sets of DNA microarray data described above were selected and their promoter regions were analyzed for the presence or absence of a putative consensus CpxR binding sequence. Based on studies performed with E. coli, this sequence consists of two conserved pentamers (i.e., GTAAA) usually separated by 5 nt (14). A recent study indicated that strong CpxR regulation in E. coli can be correlated with the presence of this motif within 100 nt in the 5′ direction from the transcriptional start site (47). Figure 4 A shows the putative consensus CpxR binding sequences in the promoter regions of lspB, ompA2, ompP2A, flp1, dsrA, and fimA. Four of these six consensus binding sequences were located within 100 nt of the translational start sites of their respective genes. The promoter region of fimA contained three GTAAA or similar sequences, while the other five promoter regions contained only two.

FIG. 4.

CpxR interacts with the promoter regions of genes encoding known and putative H. ducreyi virulence factors but not with the promoter regions of homologs of E. coli cell envelope stress response genes. (A) Nucleotide sequences of the promoter regions for the H. ducreyi lspB, ompA2, ompP2A, flp1, dsrA, and fimA genes. Putative consensus CpxR binding sequences are shown in bold and underlined. Numbers in parentheses indicate the position of the first base of the first repeat (left) and the last base of the last repeat (right) relative to the predicted translation initiation codon. (B and D) Results from EMSAs using 50 pmol of purified rCpxR-His together with the DIG-labeled promoter region DNA. Nucleotide sequences of the primers used to PCR amplify the promoter regions are listed in Table 2. (B) Results from EMSAs using the promoter regions of gyrB, lspA1, lspB, ompA2, ompP2A, flp1, dsrA, and fimA. The lspB, lspA1, and gyrB promoter regions were used as positive (i.e., lspB) or negative (i.e., lspA1 and gyrB) controls in every assay. The minus sign indicates that no CpxR protein was present, whereas the plus sign indicates the presence of CpxR protein. (C) Real-time RT-PCR analysis of gene expression from lspA1, lspB, dsrA, flp1, degP, dsbA, ppiD, psd, and secA in H. ducreyi ΔcpxA relative to wild-type H. ducreyi. (D) Results from EMSAs using the promoter regions of the following H. ducreyi genes: degP, dsbA, ppiD, psd, and secA.

EMSAs were performed using purified H. ducreyi recombinant CpxR (rCpxR)-His, with the promoter regions of lspA1 and gyrB being used as negative controls and the lspB promoter region being used as a positive control (35). The former promoter regions did not detectably bind CpxR in the EMSA, whereas the latter promoter region exhibited a readily apparent shift in the EMSA when CpxR was present (Fig. 4B). The lspB, ompA2, ompP2A, flp, and dsrA promoter regions all exhibited readily apparent decreases in the rate of migration in the EMSA when CpxR was present (Fig. 4B), indicating that CpxR directly interacts with these promoter regions and that the genes are likely to be part of the CpxRA regulon in H. ducreyi. In contrast, numerous attempts to demonstrate binding of CpxR to the promoter region of fimA by EMSA were unsuccessful. In view of the latter result, although the expression of the fimABCD operon changes dramatically when CpxR is in an active state (Table 3 and Fig. 3), the effect exerted by CpxR on expression of the fimABCD operon is apparently not direct.

H. ducreyi CpxR interaction with the promoter regions of genes likely to be involved in the cell envelope stress response.

The CpxRA system in enteric organisms, including E. coli, has been extensively studied (for a review, see reference 47). Although the extent of the CpxRA regulon in E. coli remains to be fully defined (47), there are at least seven genes (degP, dsbA, ppiA, ppiD, psd, secA, and spy) that have been shown to be involved in the response to cell envelope stress and that are regulated by the CpxRA system in E. coli. The H. ducreyi 35000HP genome (GenBank accession no. NC_002940) was investigated to find homologs of the aforementioned enteric genes. HD0260 was found to have 53% identity (BLAST probability score, 6 × 10−127) to E. coli degP, HD0638 had 43% identity (BLAST probability score, 1 × 10−47) to E. coli dsbA, HD1737 had 30% identity (BLAST probability score, 8 × 10−76) to E. coli ppiD, HD0649 had 54% identity (BLAST probability score, 5 × 10−93) to E. coli psd, and HD1788 had 67% identity (BLAST probability score, 0.0) to E. coli secA. H. ducreyi apparently lacks homologs of the E. coli ppiA and spy genes.

Analysis of the expression profiles of the aforementioned genes (exclusive of ppiA and spy) in the DNA microarray-based experiments in which CpxR was either overexpressed [i.e., in the comparison of 35000HPΔcpxR(pML125) and 35000HPΔcpxR(pLS88)] or constitutively phosphorylated (i.e., in the comparison of 35000HPΔcpxA and 35000HP) revealed that the expression of these five genes did not change significantly in either of the data sets (data not shown). Subsequent real-time RT-PCR analysis of gene expression under conditions in which CpxR is constitutively phosphorylated (i.e., in 35000HPΔcpxA versus 35000HP) was used to validate the DNA microarray results. In comparison to the changes in expression of lspB, dsrA, and flp1 in the cpxA mutant, the changes in expression of degP, dsbA, ppiD, psd, and secA were very modest and did not meet the 2-fold minimum difference cutoff (Fig. 4C). Analysis of the promoter regions of degP and ppiD revealed the presence of poor consensus CpxR binding motifs, because they lack highly conserved residues and the linker regions between the two GTAAA repeats are either too long or too short (data not shown). The promoter regions of dsbA, psd, and secA did not have any recognizable CpxR binding motifs.

The interaction of the promoter regions of degP, dsbA, ppiD, psd, and secA with H. ducreyi rCpxR-His was next tested in the EMSA. Only the degP promoter region showed an apparent interaction with the H. ducreyi protein, whereas the other four promoter regions did not (Fig. 4D). Repeated attempts to demonstrate an interaction of CpxR with the promoter regions of the rest of these well-known cell envelope stress response genes were unsuccessful. These results suggest either that H. ducreyi has a different and presently unidentified set of genes to deal with envelope stress response or that the CpxRA regulon is functionally different from the CpxRA two-component regulatory systems in other bacteria and controls primarily gene products not involved in the cell envelope stress response.

DISCUSSION

Bacteria have multiple different mechanisms for sensing their environment and responding with changes in gene expression. Given the importance of the integrity of the cell envelope to bacterial survival, it is not surprising that five different systems which respond to stresses in the envelope have been identified (for a review, see reference 38). Among these, the CpxRA TCS is perhaps the best studied. At least two important functions have been ascribed to the Cpx system in enteric bacteria; these include regulating factors that deal with misfolded proteins in the periplasmic space and affecting expression of surface components that mediate attachment to some surfaces. It has also been suggested that the Cpx signaling pathway may play a role in signaling E. coli cells present in biofilms to stop making biofilm-related adhesins (17). The signals that activate the Cpx system in E. coli are diverse and include alkaline pH, overexpression of certain proteins, interaction with abiotic surfaces, and others (for a review, see reference 38). The Cpx regulon in E. coli has been described as involving 34 operons and at least 50 genes, some of which are still uncharacterized (47).

In contrast to the numerous different TCSs present in E. coli, the CpxRA system is the only complete TCS in H. ducreyi (Robert S. Munson, Jr., personal communication). A previous study showed that growth of H. ducreyi in the presence of fetal calf serum results in downregulation of the CpxRA system and that a cpxR deletion mutant expresses significantly increased levels of both LspB and LspA2 (35). Additional experiments indicated that a purified recombinant H. ducreyi CpxR protein bound to the promoter region of the lspB-lspA2 operon and that overexpression of CpxR causes decreased expression of LspB and LspA2 (35). These data indicated that CpxR was likely to be a negative regulator of this small operon. In the present study, we constructed additional H. ducreyi mutants and complemented mutant strains and used EMSAs to begin to identify the components of the CpxRA regulon in this sexually transmitted pathogen.

Analysis of the predicted structural features of both the H. ducreyi CpxA and CpxR proteins revealed that both of these macromolecules closely resemble their respective homologs in other bacteria. The H. ducreyi CpxA and CpxR proteins had 78% and 90% identity to the respective Cpx proteins expressed by A. pleuropneumoniae, and the H. ducreyi CpxR protein was impressively conserved across different genera. The H. ducreyi CpxA protein likely assumes a topology that is frequently observed for the membrane-bound HKs of TCSs (58). There are two membrane-spanning α-helices; a periplasmic domain is located between these helices, and a large cytoplasmic domain dominates the C-terminal portion of the second helix. HKs having this topology are complex, dynamic dimers that likely undergo significant conformational changes during the course of a signaling cycle (11, 26). In other HKs, these changes are induced by the binding of ligands to the periplasmic sensor domain (58). In the case of H. ducreyi CpxA, however, the signal is unknown.

The H. ducreyi CpxR protein very likely comprises two domains: a receiver domain that accepts a phosphoryl moiety from the activated H. ducreyi CpxA and a DNA binding domain whose activity (i.e., relative ability to bind DNA) is modulated by the phosphorylation status of the receiver domain. The H. ducreyi CpxR protein appears to be different from other response regulators in that the connector region between the aforementioned two domains is longer than those described previously. The significance of this difference, if any, remains to be determined.

In E. coli and other enteric bacteria, the cytoplasmic membrane-bound CpxA histidine kinase is the sensor for the CpxRA TCS, functions as an autokinase, and has both phosphotransferase and phosphatase activities with respect to its cognate response regulator CpxR. In E. coli, deletion of cpxA removes the CpxA-based phosphatase activity but does not prevent CpxR from being phosphorylated, likely by the small phosphodonor acetyl phosphate (13, 50, 68). In the absence of CpxA phosphatase activity, phosphorylated CpxR should accumulate and exert a maximal effect, in the positive or negative sense, on genes regulated by CpxR (15, 32). We used this as a working assumption when we constructed a cpxA deletion mutation in H. ducreyi 35000HP. The findings depicted in Fig. 2 and 3 support our working assumption that the cpxA mutation in H. ducreyi resulted in what appears to be a constitutively active (i.e., phosphorylated) CpxR protein. We reported previously that CpxR acts as a repressor of expression of the lspB-lspA2 operon in H. ducreyi (35). Inactivation of the cpxA gene (Fig. 2C, lane 2) resulted in an almost complete elimination of LspB and LspA2 protein expression detectable by Western blot analysis. Real-time RT-PCR analysis (Fig. 2D) confirmed that this inhibitory effect in the cpxA mutant was exerted at the level of transcription. It should be noted that CpxR levels in the cpxA mutant (Fig. 2C, lane 2) appeared to be equivalent to those in the wild-type strain (Fig. 2C, lane 1), so the increased repression of lspB and lspA2 is consistent with CpxR's being highly phosphorylated in this mutant. Interestingly, overexpression of CpxR [in the recombinant strain 35000HPΔcpxR(pML125)] (Fig. 2A, lane 3) resulted in a similarly enhanced level of repression of LspB and LspA2 expression. Taken together, these results indicated that the increased CpxR activity in these two strains might be useful in studies using DNA microarray analysis to identify the components of the CpxRA regulon in H. ducreyi.

DNA microarray analyses comparing the cpxA deletion mutant with the wild-type strain and the recombinant H. ducreyi strain overexpressing CpxR [35000HPΔcpxR(pML125)] with a recombinant strain that cannot express CpxR [35000HPΔcpxR(pLS88)] showed that numerous genes were up- or downregulated by both constitutively phosphorylated CpxR and extremely abundant CpxR (Table 3, first and second expression ratio columns, respectively). In addition, there were some genes whose expression was affected under the former condition but not under the latter condition and vice versa. The most upregulated gene when CpxR was constitutively phosphorylated (i.e., in 35000HPΔcpxA) was ompP2B. Analysis of whole-cell lysates comparing the wild type to 35000HPΔcpxA (Fig. 1E) also showed the corresponding protein to be highly expressed. The two sets of DNA microarray results are derived from significant alterations of the CpxRA regulatory system and likely include some genes whose expression is not directly affected by CpxR. Inspection of the promoter regions of the 10 most up- or downregulated genes (not including multiple genes apparently linked in an operon) affected by CpxR (Table 3) revealed that only 20% of these genes contained a putative consensus CpxR binding motif (data not shown). This finding makes it likely that the other 80% of these genes are regulated only indirectly by CpxR.

Three interesting findings are contained within these data sets and the accompanying EMSA results. The first is that the putative fimABCD operon was highly upregulated when CpxR was either constitutively phosphorylated or very abundant in H. ducreyi (Table 3). Whereas the genes encoding the fine tangled pili (9) and other surface proteins of H. ducreyi have been described previously, there have not been any previous descriptions of this four-gene cluster. The predicted FimA major structural protein has 30 to 40% identity (at the amino acid sequence level) with fimbrial proteins of other Gram-negative species, including Providencia rettgeri (GenBank accession number EFE54293.1), Yersinia pseudotuberculosis (GenBank accession number ACC90454.1), and Serratia marcescens (GenBank accession number AAA26576.1). It must also be noted that the fimA promoter region did not exhibit a change in its migration characteristics when incubated with CpxR in the EMSA, a result which indicates that CpxR likely does not directly regulate expression of fimA. This finding raises the possibility that CpxR may be part of a regulatory cascade controlling the expression of the fimABCD operon or that it may be part of a protein complex needed for binding. Similarly, whether the predicted fimbrial proteins are expressed by H. ducreyi either in vivo or in vitro remains to be determined, and it would be of interest to determine whether inactivation of this operon would reduce the virulence potential of H. ducreyi. It should be noted here that phosphorylated CpxR has been shown previously to be involved in the control of the expression of other surface appendages, including the curli fimbriae (48) and the uropathogenic E. coli P pilus (24).

The second result of significance is the observation that CpxR affects the expression of at least three proven virulence factors expressed by H. ducreyi. In addition to the LspA2 protein, which can inhibit the phagocytic activity of macrophage-like cell lines in vitro (60), the flp operon genes and the dsrA gene both exhibited significant downregulation of expression when CpxR was either constitutively phosphorylated or very abundant (Table 3; Fig. 2C and D and 3). An intact flp gene cluster has been shown to be required for full virulence of H. ducreyi in the human challenge model for experimental chancroid (55), and inactivation of the dsrA gene markedly attenuates the virulence of this pathogen in the same model system (8). In addition to these proven virulence factors, the expression of the genes encoding the presumably surface-exposed outer membrane proteins OmpA2 (33) and OmpP2A (46) was negatively affected by CpxR (Fig. 3), as was expression of the gene encoding the HhdA hemolysin (43). In contrast, the expression of the outer membrane protein OmpP2B (46) was upregulated in the absence of CpxA (Fig. 3A). A detailed analysis of the ompP2B promoter region showed the lack of a defined consensus CpxR binding motif, and EMSA studies showed no interaction with purified rCpxR (data not shown). Therefore, it is likely that the effect of CpxR on the regulation of expression of OmpP2B is indirect. The opposing responses of the ompP2A and ompP2B genes to phosphorylated CpxR (Fig. 3A) is reminiscent of those observed in an E. coli cpxA mutant in which there was increased transcription of ompC and decreased transcription of ompF (5).

The third interesting result was the apparent lack of effect of the H. ducreyi CpxR protein on expression of H. ducreyi homologs of genes that have been established as being regulated by CpxR in E. coli (47). The promoter regions of a number of these genes, including degP, dsbA, ppiD, psd, and secA, were tested for their abilities to bind H. ducreyi CpxR in an EMSA. Only degP showed apparent binding of CpxR in the EMSA (Fig. 4D). These EMSA-derived data were reinforced by real-time RT-PCR analyses in which these five genes showed relatively little change in expression in a cpxA mutant (Fig. 4C). Taken together with the observed effect of CpxR on expression of several H. ducreyi virulence factors (discussed above), these data raise the possibility that, in H. ducreyi, perhaps another gene product is involved in controlling the cell envelope stress response. However, the apparent absence of other complete TCSs in this pathogen (Robert S. Munson, Jr., personal communication) makes this scenario somewhat unlikely.

The full extent of the CpxRA regulon in H. ducreyi remains to be elucidated. However, based on the results presented above, its composition may be quite different from that currently defined in E. coli. In silico analysis of the H. ducreyi genome detected between 100 and 300 loci with homology to the E. coli consensus CpxR binding motif, dependent on the stringency of the search parameters (data not shown). How many of these are actually controlled by CpxR is not known, nor is there any information currently available about what environmental signals might activate the CpxA sensor kinase, with the exception that transcription of both cpxR and cpxA appears to be downregulated in H. ducreyi in the presence of fetal calf serum (35). It should also be noted that all of the experiments in the present study utilized H. ducreyi 35000HP, a prototypic class I strain of the pathogen (64). Two clonal H. ducreyi populations (i.e., class I and class II) have been described as differing in the expression of certain surface-exposed proteins and lipooligosaccharide (45). Whether gene expression in class II strains of H. ducreyi may differ with regard to regulation by CpxR was not investigated in this study and would need to be addressed in the future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Public Health Service grant no. AI32011 to E.J.H.

We thank Stanley Spinola for providing the PAL-specific MAb 3B9 and Christopher Elkins for supplying polyclonal antibody to DsrA.

Editor: A. J. Bäumler

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 August 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://iai.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Tawfiq, J. A., K. R. Fortney, B. P. Katz, A. F. Hood, C. Elkins, and S. M. Spinola. 2000. An isogenic hemoglobin receptor-deficient mutant of Haemophilus ducreyi is attenuated in the human model of experimental infection. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1049-1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aravind, L., and C. P. Ponting. 1999. The cytoplasmic helical linker domain of receptor histidine kinase and methyl-accepting proteins is common to many prokaryotic signalling proteins. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 176:111-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banks, K. E., K. R. Fortney, B. Baker, S. D. Billings, B. P. Katz, R. S. J. Munson, and S. M. Spinola. 2008. The enterobacterial common antigen-like gene cluster of Haemophilus ducreyi contributes to virulence in humans. J. Infect. Dis. 197:1531-1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batchelor, E., D. Walthers, L. J. Kenney, and M. Goulian. 2005. The Escherichia coli CpxA-CpxR envelope stress response system regulates expression of the porins OmpF and OmpC. J. Bacteriol. 187:5723-5731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauer, M. E., C. A. Townsend, R. S. Doster, K. R. Fortney, B. W. Zwickl, B. P. Katz, S. M. Spinola, and D. M. Janowicz. 2009. A fibrinogen-binding lipoprotein contributes to the virulence of Haemophilus ducreyi in humans. J. Infect. Dis. 199:684-692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bong, C. T., M. E. Bauer, and S. M. Spinola. 2002. Haemophilus ducreyi: clinical features, epidemiology, and prospects for disease control. Microbes Infect. 4:1141-1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bong, C. T., R. E. Throm, K. R. Fortney, B. P. Katz, A. F. Hood, C. Elkins, and S. M. Spinola. 2001. DsrA-deficient mutant of Haemophilus ducreyi is impaired in its ability to infect human volunteers. Infect. Immun. 69:1488-1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brentjens, R. J., M. Ketterer, M. A. Apicella, and S. M. Spinola. 1996. Fine tangled pili expressed by Haemophilus ducreyi are a novel class of pili. J. Bacteriol. 178:808-816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlsson, K. E., J. Liu, P. J. Edqvist, and M. S. Francis. 2007. Influence of the Cpx extracytoplasmic-stress-responsive pathway on Yersinia sp.-eukaryotic cell contact. Infect. Immun. 75:4386-4399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casino, P., V. Rubio, and A. Marina. 2009. Structural insight into partner specificity and phosphoryl transfer in two-component signal transduction. Cell 139:325-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dahl, J. L., B. Y. Wei, and R. J. Kadner. 1997. Protein phosphorylation affects binding of the Escherichia coli transcription activator UhpA to the uhpT promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 272:1910-1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Danese, P. N., W. B. Snyder, C. L. Cosma, L. J. B. Davis, and T. J. Silhavy. 1995. The Cpx two-component signal transduction pathway of Escherichia coli regulates transcription of the gene specifying the stress-inducible periplasmic protease, DegP. Genes Dev. 9:387-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Wulf, P., A. M. McGuire, X. Liu, and E. C. Lin. 2002. Genome-wide profiling of promoter recognition by the two-component response regulator CpxR-P in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 277:26652-26661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Wulf, P., and E. C. C. Lin. 2000. Cpx two-component signal transduction in Escherichia coli: excessive CpxR-P levels underlie CpxA* phenotypes. J. Bacteriol. 182:1423-1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dixon, L. G., W. L. Albritton, and P. J. Willson. 1994. An analysis of the complete nucleotide sequence of the Haemophilus ducreyi broad-host-range plasmid pLS88. Plasmid 32:228-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dorel, C., P. Lejeune, and A. Rodrigue. 2006. The Cpx system of Escherichia coli, a strategic signaling pathway for confronting adverse conditions and for settling biofilm communities? Res. Microbiol. 157:306-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elkins, C. 1995. Identification and purification of a conserved heme-regulated hemoglobin-binding outer membrane protein from Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect. Immun. 63:1241-1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elkins, C., K. J. Morrow, Jr., and B. Olsen. 2000. Serum resistance in Haemophilus ducreyi requires outer membrane protein DsrA. Infect. Immun. 68:1608-1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fleming, D. T., and J. N. Wasserheit. 1999. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sex. Transm. Infect. 75:3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fortney, K. R., R. S. Young, M. E. Bauer, B. P. Katz, A. F. Hood, R. S. Munson, Jr., and S. M. Spinola. 2000. Expression of peptidoglycan-associated lipoprotein is required for virulence in the human model of Haemophilus ducreyi infection. Infect. Immun. 68:6441-6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fulcher, R. A., L. E. Cole, D. M. Janowicz, K. L. Toffer, K. R. Fortney, B. P. Katz, P. E. Orndorff, S. M. Spinola, and T. H. Kawula. 2006. Expression of Haemophilus ducreyi collagen binding outer membrane protein NcaA is required for virulence in swine and human challenge models of chancroid. Infect. Immun. 74:2651-2658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haydock, A. K., D. H. Martin, S. A. Morse, C. Cammarata, K. J. Mertz, and P. A. Totten. 1999. Molecular characterization of Haemophilus ducreyi strains from Jackson, Mississippi and New Orleans, Louisiana. J. Infect. Dis. 179:1423-1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hernday, A. D., B. A. Braaten, G. Broitman-Maduro, P. Engelberts, and D. A. Low. 2004. Regulation of the Pap epigenetic switch by CpxAR: Phosphorylated CpxR inhibits transition to the phase ON state by competition with Lrp. Mol. Cell 16:537-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horton, R. M., H. D. Hunt, S. N. Ho, J. K. Pullen, and L. R. Pease. 1989. Engineering hybrid genes without the use of restriction enzymes: gene splicing by overlap extension. Gene 77:61-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hulko, M., F. Berndt, M. Gruber, J. U. Linder, V. Truffault, A. Schultz, J. Martin, J. E. Schultz, A. N. Lupas, and M. Coles. 2006. The HAMP domain structure implies helix rotation in transmembrane signaling. Cell 126:929-940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jamet, A., C. Rousseau, J. B. Monfort, E. Frapy, X. Nassif, and P. Martin. 2009. A two-component system is required for colonization of host cells by meningococcus. Microbiology 155:2288-2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janowicz, D., I. Leduc, K. R. Fortney, B. P. Katz, C. Elkins, and S. M. Spinola. 2006. A DltA mutant of Haemophilus ducreyi Is partially attenuated in its ability to cause pustules in human volunteers. Infect. Immun. 74:1394-1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janowicz, D. M., K. R. Fortney, B. P. Katz, J. L. Latimer, K. Deng, E. J. Hansen, and S. M. Spinola. 2004. Expression of the LspA1 and LspA2 proteins by Haemophilus ducreyi is required for virulence in human volunteers. Infect. Immun. 72:4528-4533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Janowicz, D. M., W. Li, and M. E. Bauer. 2010. Host-pathogen interplay of Haemophilus ducreyi. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 23:64-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janowicz, D. M., S. Ofner, B. P. Katz, and S. M. Spinola. 2009. Experimental infection of human volunteers with Haemophilus ducreyi: fifteen years of clinical data and experience. J. Infect. Dis. 199:1671-1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klein, A. H., A. Shulla, S. A. Reimann, D. H. Keating, and A. J. Wolfe. 2007. The intracellular concentration of acetyl phosphate in Escherichia coli is sufficient for direct phosphorylation of two-component response regulators. J. Bacteriol. 189:5574-5581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klesney-Tait, J., T. J. Hiltke, I. Maciver, S. M. Spinola, J. D. Radolf, and E. J. Hansen. 1997. The major outer membrane protein of Haemophilus ducreyi consists of two OmpA homologs. J. Bacteriol. 179:1764-1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Labandeira-Rey, M., D. M. Janowicz, R. J. Blick, K. R. Fortney, B. Zwickl, B. P. Katz, S. M. Spinola, and E. J. Hansen. 2009. Inactivation of the Haemophilus ducreyi luxS gene affects the virulence of this pathogen in human subjects. J. Infect. Dis. 200:409-416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Labandeira-Rey, M., J. R. Mock, and E. J. Hansen. 2009. Regulation of expression of the Haemophilus ducreyi LspB and LspA2 proteins by CpxR. Infect. Immun. 77:3402-3411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lewis, D. A. 2003. Chancroid: clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and management. Sex. Transm. Infect. 79:68-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lukomski, S., R. A. Hull, and S. I. Hull. 1996. Identification of the O antigen polymerase (rfc) gene in Escherichia coli O4 by insertional mutagenesis using a nonpolar chloramphenicol resistance cassette. J. Bacteriol. 178:240-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.MacRitchie, D. M., D. R. Buelow, N. L. Price, and T. L. Raivio. 2008. Two-component signaling and gram negative envelope stress response systems. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 631:80-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marina, A., C. D. Waldburger, and W. A. Hendrickson. 2005. Structure of the entire cytoplasmic portion of a sensor histidine-kinase protein. EMBO J. 24:4247-4259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mertz, K. J., D. L. Trees, W. C. Levine, J. S. Lewis, B. Litchfield, K. S. Pettus, S. A. Morse, M. E. St. Louis, J. B. Weiss, J. Schwebke, J. Dickes, R. Kee, J. Reynolds, D. Hutcheson, D. Green, I. Dyer, G. A. Richwald, J. Novotny, M. Goldberg, J. A. O'Donnell, and R. Knaup for the Genital Ulcer Disease Surveillance Group. 1998. Etiology of genital ulcers and prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus coinfection in 10 US cities. J. Infect. Dis. 178:1795-1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nika, J. R., J. L. Latimer, C. K. Ward, R. J. Blick, N. J. Wagner, L. D. Cope, G. G. Mahairas, R. S. Munson, Jr., and E. J. Hansen. 2002. Haemophilus ducreyi requires the flp gene cluster for microcolony formation in vitro. Infect. Immun. 70:2965-2975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Overton, T. W., R. Whitehead, Y. Li, L. A. Snyder, N. J. Saunders, H. Smith, and J. A. Cole. 2006. Coordinated regulation of the Neisseria gonorrhoeae-truncated denitrification pathway by the nitric oxide-sensitive repressor, NsrR, and nitrite-insensitive NarQ-NarP. J. Biol. Chem. 281:33115-33126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palmer, K. L., and R. S. Munson, Jr. 1995. Cloning and characterization of the genes encoding the haemolysin of Haemophilus ducreyi. Mol. Microbiol. 18:821-830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pei, J., B. H. Kim, and N. V. Grishin. 2008. PROMALS3D: a tool for multiple protein sequence and structure alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:2295-2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Post, D. M., and B. W. Gibson. 2007. Proposed second class of Haemophilus ducreyi strains show altered protein and lipooligosaccharide profiles. Proteomics 7:3131-3142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prather, D. T., M. Bains, R. E. Hancock, M. J. Filiatrault, and A. A. Campagnari. 2004. Differential expression of porins OmpP2A and OmpP2B of Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect. Immun. 72:6271-6278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Price, N. L., and T. L. Raivio. 2009. Characterization of the Cpx regulon in Escherichia coli strain MC4100. J. Bacteriol. 191:1798-1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Prigent-Combaret, C., E. Brombacher, O. Vidal, A. Ambert, P. Lejeune, P. Landini, and C. Dorel. 2001. Complex regulatory network controls initial adhesion and biofilm formation in Escherichia coli via regulation of the csgD gene. J. Bacteriol. 183:7213-7223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raivio, T. L. 2005. Envelope stress responses and Gram-negative bacterial pathogenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 56:1119-1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raivio, T. L., and T. J. Silhavy. 1997. Transduction of envelope stress in Escherichia coli by the Cpx two-component system. J. Bacteriol. 179:7724-7733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]