Abstract

The pathogen of Lyme disease, Borrelia burgdorferi, produces a putative surface protein termed “surface-located membrane protein 1” (Lmp1). Lmp1 has been shown previously to assist the microbe in evasion of host-acquired immune defenses and in the establishment of persistent infection of mammals. Here, we show that Lmp1 is an integral membrane protein with surface-exposed N-terminal, middle, and C-terminal regions. During murine infection, antibodies recognizing these three protein regions were produced. Separate immunization of mice with each of the discrete regions exerted differential effects on spirochete survival during infection. Notably, antibodies against the C-terminal region primarily interfered with B. burgdorferi persistence in the joints, while antibodies specific to the N-terminal region predominantly affected pathogen levels in the heart, including the development of carditis. Genetic reconstitution of lmp1 deletion mutants with the lmp1 N-terminal region significantly enhanced its ability to resist the bactericidal effects of immune sera and also was observed to increase pathogen survival in vivo. Taken together, the combined data suggest that the N-terminal region of Lmp1 plays a distinct role in spirochete survival and other parts of the protein are related to specific functions corresponding to pathogen persistence and tropism during infection that is displayed in an organ-specific manner. The findings reported here underscore the fact that surface-exposed regions of Lmp1 could potentially serve as vaccine targets or antigenic regions that could alter the course of natural Lyme disease.

Lyme disease is caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi, which is transmitted by ticks belonging to the Ixodes scapularis complex (2, 31). Upon introduction to the host dermis, spirochetes disseminate from the site of infection to distal cutaneous areas and navigate to a variety of internal host organs (6). The colonization of the pathogen in a select set of infected host organs eventually leads to robust inflammatory responses resulting in multiple clinical complications, such as arthritis, carditis, and neurological disorders (31, 48). In mammalian hosts, B. burgdorferi infection may persist in diverse tissues despite the development of a vigorous immune response (5, 8, 13, 16, 24, 44). Understanding the mechanism by which spirochetes selectively persist in certain tissues and induce a severe inflammatory response is important for the development of preventive and therapeutic strategies against Lyme borreliosis.

B. burgdorferi survives in a complex enzootic life cycle. The varied metabolic and immune host environments have been shown to dramatically influence spirochete gene expression (11, 14, 26, 29, 32-34, 41, 43, 49, 51). Microbial antigens that are produced in a time- or tissue-specific manner might assist B. burgdorferi to overcome host defenses and to persist in local environments. Differentially expressed gene products, particularly surface antigens, could directly participate in host-pathogen interaction or host immune evasion, contributing to microbial survival and organ-specific pathogenesis (36, 51). In recent years, a few spirochete gene products have been identified that are either indispensable or contribute significantly to host or vector infectivity and transmission through the tick-mouse infection cycle (9, 23, 25, 26, 28, 37, 39, 40, 45, 47, 52, 53). However, in most cases, the genes identified encoded proteins that lack orthologs in other bacteria; therefore, their molecular functions in spirochete biology or infectivity remain unclear.

Recently, a protein termed Lmp1, a chromosomally encoded antigen with an approximate molecular mass of 128 kDa, was shown to be induced in infected murine tissues, especially at early phases of infection in the heart (51). Lmp1 has been suggested to be integral to pathogen persistence and to be involved in evading the host adaptive immune response during infection (51). The antigen is localized to the microbial surface, is immunogenic during animal or human infection (3, 51), and is conserved across orthologs in other B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates. Computer algorithms suggest that Lmp1 contains a typical type I leader peptide, although whether the signal sequence is cleaved remains unknown. Lmp1 contains three possible separate functional regions located at the N-terminal, middle, and C-terminal portions of the protein. Although the overall structure of Lmp1 is unrelated to known proteins, the middle region of the protein contains several peptide repeats which may be related to adhesins (3). The C-terminal region contains several tetratricopeptide repeats (TPRs), which are motifs that are well documented to play important roles in protein-protein interactions (17, 22, 42). Despite earlier studies, the molecular function of Lmp1 and the possible unique role(s) of its individual protein regions with regard to B. burgdorferi virulence and Lyme disease pathogenesis remain unclear. Characterization of functional protein regions of novel spirochete virulence determinants, such as Lmp1, will likely shed further light into how Lmp1 could potentially serve as a vaccine target or how antibodies against antigenic regions of Lmp1 could alter the course of a natural Lyme disease infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and mice.

A low-passage and infectious isolate of B. burgdorferi strain B31-A3 (18), B31-A3-LK (21), and the flacp-795-LK strain (27) were used in the study and cultivated at 34°C in Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly liquid medium containing 6% heat-inactivated rabbit serum (BSK-H). For genetic manipulation of lmp1 mutants, the medium was supplemented with kanamycin (200 to 350 μg/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). Medium containing gentamicin (40 μg/ml), erythromycin (80 ng/ml), or isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; 0.05 mM or 1.0 mM) was used to grow the LK isolates. Four- to 6-week-old female C3H/HeN and BALB/c mice were purchased from the National Institutes of Health. All animal procedures were performed in compliance with the guidelines and approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Maryland, College Park.

PCR.

The primers used in PCR amplification are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) and quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analyses were performed as described before (51). Briefly, total RNA was isolated and reverse transcribed into first-strand cDNA, and the quantitative PCR was performed in an iQ5 real-time thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using SYBR green supermix (Bio-Rad) and a program consisting of an initial denaturing step of 3 min at 95°C followed by 40 amplification cycles consisting of 10 s at 95°C, 60°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 30 s. Standard curves were prepared from known quantities of flaB and murine β-actin gene to calculate the target gene transcripts as described previously (15). For the quantification of spirochete levels in mouse tissues, flaB was used as a surrogate marker and normalized to the level of the β-actin gene.

Preparation of truncated Lmp1 proteins representing specific regions of the antigen and generation of antisera.

To produce recombinant proteins representing the three unique regions of Lmp1, the coding region of the lmp1 without its leader peptide was amplified as separate DNA inserts representing either the N-terminal (1,026-bp), middle (1,161-bp), or C-terminal (1,107-bp) regions of the gene using the primers listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. DNA inserts were directionally cloned into the BamHI and XhoI sites of the expression vector pGEX-6P-1 (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). Expression, purification, and enzymatic cleavage of the resulting glutathione-S-transferase fusion proteins were carried out as described previously (51, 53). For generation of murine antisera, 10 μg of recombinant protein was dissolved in 100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), emulsified with 100 μl of complete (first injection) or incomplete (remaining two injections) Freund's adjuvant, and subcutaneously administered into groups of five BALB/c mice at 10-day intervals. Mice were bled 7 days after the final boost, and serum was collected. Antibody titers were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and immunoblotting, as described previously (51, 53).

ELISA.

Ninety-six-well plates were coated with Lmp1 proteins (100 ng/well) or B. burgdorferi lysates (500 ng/well) and incubated overnight at 4°C. The plates were blocked with PBS-T (0.05% Tween 20, 5% normal goat serum in PBS, pH 7.4) for 2 h at 37°C and washed with PBS. The diluted (1:5,000) mouse sera were added to each well and incubated 37°C for 1 h. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (100 μl of a 1:5,000 dilution) was added, and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 1 h. After being washed three times with PBS, 100 μl of TMB (3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine) substrate was added to each well and optical densities at 450 nm (OD450) were measured.

Western blotting.

Purified recombinant proteins or whole-cell lysates of B. burgdorferi were subjected to 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was incubated with a 1:1,000 to 1:2,000 dilution of murine antisera against the various recombinant proteins. Immunoblots were developed by the addition of HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence as previously described (15, 27).

Assessment of Lmp1 as an integral outer membrane protein (OMP).

B. burgdorferi outer membranes (OMs) and protoplasmic cylinders (PCs) were isolated from strain B31-A3-LK and the flacp-795-LK strain (in 0.05 mM or 1 mM IPTG) as previously described (27). Equivalent amounts of whole-cell lysates, OMs, and PCs were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibodies specific for BamA, BB0405, Lmp1, OppA IV, or FlaB as described below.

Triton X-114 phase partitioning.

Triton X-114 phase partitioning assays were performed as previously described (12, 30). Briefly, 109 spirochetes were resuspended in 200 μl of PBS (pH 7.4), sonicated on ice, mixed with 200 μl of 10% Triton X-114, and incubated overnight. The lysates were centrifuged to remove Triton X-114-insoluble material, and the supernatant was incubated at 37°C for 15 min, followed by separation of the aqueous and detergent phases by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 15 min at room temperature. The separated phases were washed five times and mixed with 10 volumes of ice-cold acetone to precipitate the protein from corresponding phases by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Protein pellets were finally resuspended in PBS and subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis using Lmp1 antibody or antibodies against known hydrophilic (BBA74) or amphiphilic (OspA and OppAIV) proteins as detailed in references 12 and 30.

Proteinase K accessibility assay.

Proteinase K accessibility assays were performed as detailed in reference 15. Briefly, 108 spirochetes were incubated in PBS in the absence or presence of proteinase K (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, MO) at a concentration of 200 μg/ml for 20 min, treated with phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma Chemical Company), pelleted, and resuspended in PBS for subsequent immunoblot analysis using antibodies against Lmp1, FlaB, or OspA.

Immunofluorescence assay.

Antiserum binding to unfixed or fixed B. burgdorferi spirochetes was examined by immunofluorescence assay as described previously (36). Silylated glass slides (PGC Scientific, Frederick, MD) were spotted with 1 × 107 spirochetes: one group remained without fixation, while another group was fixed with methanol for 10 min at room temperature. For immunofluorescence labeling, the spirochetes were blocked with PBS-T and incubated with specific antiserum directed against the three Lmp1 regions (1:500 dilution in PBS-T), Lp6.6 (38), or OspA (35) followed by secondary antibodies and processed for microscopic examination as described previously (36).

In vitro bactericidal assay.

Mouse antisera collected from hosts immunized with the region-specific Lmp1 proteins or antisera collected following 2 weeks of B. burgdorferi infection were used for bactericidal assays. The experiments were performed using undiluted sera with or without complement inactivation, which were stored at −70°C until use. The ability of the antisera to kill live B. burgdorferi spirochetes was determined by enumeration of spirochetes after labeling with Live/Dead BacLight viability kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), as detailed in reference 51. Additionally, 24 h following the addition of antiserum, 1 μl of medium containing spirochetes was added to 1 ml of fresh BSK-H medium to assess the spirochetes' ability to regrow in the culture. Spirochetes were incubated at 33°C and were enumerated by dark-field microscopy at 24, 48, 60, 72, and 84 h, as described previously (35).

Antibody blocking studies in vivo.

Groups of five C3H/HeN mice were immunized with the region-specific Lmp1 proteins according to the immunization regimen described above. A control group of mice immunized with PBS containing an equal volume of adjuvant preparations served as a control. Seven days after the final booster injection, the titers and specificities of antibodies against the truncated proteins were tested by ELISA and immunoblotting. Mice were then infected by intradermal inoculation with B. burgdorferi (105 spirochetes/mouse) as described previously (36). At days 14 and 21 following B. burgdorferi challenge, selected organs, including heart, joints, and bladder, were harvested for RNA extraction. The spirochete levels in different tissues were measured by qRT-PCR analysis.

Generation and phenotypic analysis of N-terminal Lmp1 region-complemented B. burgdorferi isolates.

Generation of Lmp1N-complemented B. burgdorferi isolates was achieved by reinsertion of a truncated version of the lmp1 gene into a previously generated lmp1 deletion mutant (51). The upstream sequence of lmp1, which corresponds to open reading frame bb0210, lacks an obvious promoter, and it overlaps with the preceding gene encoding tetratricopeptide repeat domain protein (bb0209) by 8 nucleotides. Thus, we assumed that lmp1 and bb0209 may share a promoter, which is likely housed within the nucleotide sequence upstream of bb0209. RT-PCR analysis confirmed that bb0209 and lmp1 are indeed cotranscribed as a bicistronic message. Therefore, a 200-bp upstream DNA sequence of bb0209 was amplified, ligated to a DNA fragment encompassing the lmp1N gene fragment by using NdeI, and cloned into the BamHI and SalI sites of pKFSS1 (20), which contains a streptomycin resistance cassette (aadA). An insert containing the predicted promoter-lmp1N gene fusion and the aadA cassette was further digested with BamHI and SmaI from the recombinant plasmid pKFSS1-lmp1N and cloned into the corresponding restriction sites of plasmid pXLF14301 (28), which contains 5′ and 3′ arms required for homologous recombination into B. burgdorferi chromosomal locus bb0444-bb0446. The locus bb0444-bb0446 was chosen as insertion site of the complementing gene as genetic manipulation at this site does not impose polar effects on the transcription of surrounding genes (28, 51). The plasmid construct was sequenced to confirm its identity, and 25 μg of the plasmid DNA was electroporated into the lmp1 mutant. Four clones were identified based on their ability to grow in the presence of both kanamycin and streptomycin. PCR analysis was used to confirm the intended recombination events, and one of the lmp1N-complemented clones that contained the same plasmid profiles as the wild type was chosen for further study. For in vitro growth analysis, spirochetes were diluted to a density of 105 cells/ml, grown until stationary phase (∼108 cells/ml), and counted by dark-field microscopy using a Petroff-Hausser cell counter as detailed in reference 51. For phenotypic analysis of lmp1N-complemented isolates in vivo, groups of mice (3 animals/group) were injected intradermally with B. burgdorferi via needle inoculation (105 spirochetes/mouse). Mice were sacrificed at 14 and 28 days following inoculation. Murine tissues, including skin, heart, joints, and bladder, were collected, and B. burgdorferi levels were measured by qRT-PCR analysis as previously described (51). Joint swelling in the ankles of infected mice was measured with digital calipers as described previously (51).

Assessment of carditis.

Heart samples from B. burgdorferi-infected mice were collected, fixed in 10% formalin, and processed for hematoxylin and eosin staining. Twenty randomly chosen sections from each mouse group were assessed for histopathological comparisons, and signs of carditis were evaluated based on the inflammatory cell infiltration, as detailed in references 7 and 10.

Bioinformatics and statistical analysis.

The Lmp1 middle (Lmp1M) and C-terminal (Lmp1C) TPR regions (corresponding to residues 453 to 697 and residues 775 to 1087, respectively) were searched and modeled using the Swiss-Model automated platform (http://swissmodel.expasy.org) (4). All results in the article are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). The significance of the difference between the mean values of the groups was evaluated by Student's t test.

RESULTS

Putative organization of Lmp1 and generation of region-specific Lmp1 antibodies.

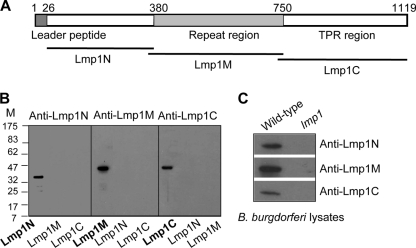

Lmp1 is a virulence determinant of B. burgdorferi, which contains three distinct protein regions representing the N-terminal (Lmp1N), middle (Lmp1M), and C-terminal (Lmp1C) regions (Fig. 1 A). Homology modeling efforts suggested that while the Lmp1N region is structurally unrelated to known proteins, Lmp1M and Lmp1C, it houses several TPR motifs aligned with certain TPR motif-containing proteins (data not shown), such as a mitochondrial surface protein, Tom70 (50), and O-linked N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (OGT) (46), respectively. To gain experimental evidence on the role of distinct Lmp1 regions in microbial persistence, truncated Lmp1 proteins representing individual regions were produced in Escherichia coli. These included generation of recombinant Lmp1N, Lmp1M and Lmp1C with predicted molecular masses of 34 kDa, 38 kDa, and 37 kDa, respectively (Fig. 1B). Murine antisera against the individual region-specific Lmp1 truncated proteins were raised that specifically recognized the target regions with undetectable cross-reactivity (Fig. 1B). As expected, the region-specific Lmp1 antisera recognized the 128-kDa native protein in B. burgdorferi (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

Region-specific Lmp1 antibodies detect the target recombinant protein and the native Lmp1. (A) Schematic drawing of region-specific Lmp1 proteins. Positions of leader peptide, N-terminal region (Lmp1N), a middle region (Lmp1M) with seven tandem peptide-repeats of 54 amino acids, and a C-terminal region (Lmp1C) containing several tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) motifs are indicated. (B) Antibody response against region-specific truncated Lmp1 proteins. The recombinant proteins were probed with region-specific antisera, revealing detection of Lmp1N (34 kDa), Lmp1M (38 kDa), and Lmp1C (37 kDa) without detectable cross-reactivity. (C) Region-specific Lmp1 antibodies recognize the native protein. B. burgdorferi lysates were immunoblotted with antisera against region-specific truncated Lmp1 proteins. lmp1, lmp1 mutant.

Lmp1 is an integral membrane protein with extracellular exposure via distinct regions.

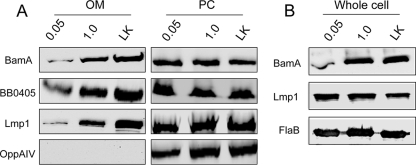

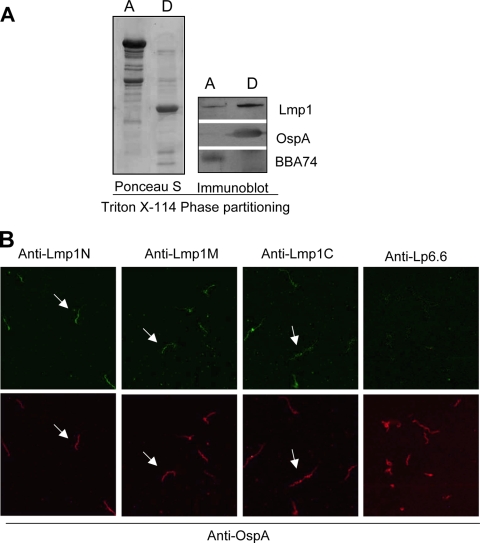

Recently the B. burgdorferi gene bb0795 has been shown to encode an ortholog of the E. coli BamA protein, which is a key protein known to be involved in the localization of integral outer membrane proteins (OMPs) into bacterial outer membranes (OMs) (27). Lmp1 is a surface-exposed membrane protein (51) that possesses a putative type I leader peptide. As Lmp1 does not contain identifiable transmembrane motifs, how the antigen is anchored to the membrane remains uncertain. To determine if integration of Lmp1 into the borrelial OM is BamA mediated, which would be expected of an integral OMP, localization experiments were performed using a regulatable bamA mutant of B. burgdorferi (27). As shown in Fig. 2 A, the amount of Lmp1 exported into the OM increased with increasing expression of the B. burgdorferi BamA protein. As a control, levels of a known integral OMP, BB0405, were also increased (Fig. 2A). In contrast, the levels of Lmp1 and BB0405 remained unchanged in the protoplasmic cylinder fractions (Fig. 2A, right panels), indicating that they are readily exported to the inner membrane but are inhibited from insertion into the OM when BamA is not expressed at normal levels. Analysis of cellular Lmp1 levels suggested that Lmp1 production is not impacted by the BamA level (Fig. 2B). Together, the results strongly suggest that Lmp1 is inserted into the OM of B. burgdorferi in a BamA-dependent manner, which would be expected of an integral OMP. In agreement, when whole-cell lysates of B. burgdorferi were fractionated using a Triton X-114 phase-partitioning assay, Lmp1 was predominantly extracted into the detergent-enriched phase that retains amphiphilic proteins (Fig. 3 A). We next analyzed the surface exposure of individual Lmp1 regions in B. burgdorferi. As assessed by an immunofluorescence assay, antiserum specific to the N-, middle, and C-terminal Lmp1 regions bound to the unfixed (Fig. 3B) or fixed (data not shown) spirochetes. Overall, the above series of experiments suggested that Lmp1 is an integral membrane protein with extracellular exposure through multiple regions of the protein.

FIG. 2.

B. burgdorferi BamA (BB0795) likely aids in localization of Lmp1 into the outer membrane. (A) BB0795 aids in membrane localization of Lmp1. Outer membrane (OM) and protoplasmic cylinder (PC) fractions were isolated from B. burgdorferi flacp-795-LK strain cultures grown in either 0.05 mM or 1.0 mM IPTG and from B31-A3-LK cultures grown in IPTG-depleted media. Equivalent amounts of OMs (left panels) and PCs (right panels) from each culture condition were subjected to immunoblot analyses with specific antiserum against Lmp1 and known integral OM proteins BB0795 and BB0405. Antibody against the inner-membrane-anchored lipoprotein OppAIV was used to ensure proper fractionation of borrelial cells. (B) BamA depletion does not affect Lmp1 production in B. burgdorferi. Whole-cell lysates of the B. burgdorferi flacp-795-LK strain grown in either 0.05 mM or 1.0 mM IPTG and of B31-A3-LK grown in IPTG-depleted medium were immunoblotted with anti-BamA and anti-Lmp1 antibodies. Lysates were also probed with FlaB antiserum to ensure equivalent loading.

FIG. 3.

Integral membrane protein Lmp1 is exposed on the spirochete surface via the Lmp1N, Lmp1M, and Lmp1C regions. (A) Triton X-114 phase partitioning of B. burgdorferi proteins. Spirochete lysates were subjected to Triton X-114 phase partitioning of aqueous (lane A) and detergent (lane D) phases and immunoblotted using Lmp1 antibody or antibodies against known hydrophilic (BBA74) or amphiphilic (OspA) proteins. (B) Immunofluorescence analysis of surface exposure of Lmp1 regions. Unfixed B. burgdorferi spirochetes were probed with antisera against region-specific Lmp1 or subsurface membrane protein Lp6.6 followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies. Spirochetes are also simultaneously labeled with anti-OspA sera followed by Alexa 568-labeled goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies. The images were acquired with the 40× objective of a laser confocal microscope.

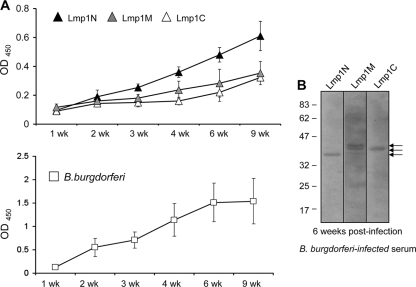

Lmp1-specific antibody responses during murine infection are directed against distinct regions.

We next assessed the kinetics of Lmp1-specific antibody development against each of the distinct regions during the first 9 weeks of B. burgdorferi infection of mice. To achieve this, mice (5 animals/group) were infected with B. burgdorferi (105 cells/mice), and serum samples were collected at weeks 1 through 9 on a weekly basis following infection. Equal amounts of recombinant region-specific Lmp1 proteins (Lmp1N, Lmp1M, or Lmp1C) (100 ng/well) or B. burgdorferi lysates (500 ng/well) were used to detect the Lmp1-specific host antibodies that developed during infection, using ELISA. The results showed that the antibody response was readily detected for all three distinct regions, with the highest response against the N-terminal portion between weeks 3 and 9, compared to that against the middle or the C-terminal regions (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4 A). Immunoblot analysis showed that the murine sera collected after 6 weeks of infection specifically recognized all three region-specific Lmp1 proteins (Fig. 4B). Collectively, these results suggested that, during infection, the Lmp1-specific antibody response was directed against all three Lmp1 regions, with a pronounced response being observed against Lmp1N.

FIG. 4.

Host antibody response against specific regions of Lmp1. (A) Region-specific Lmp1 proteins (upper panel) and B. burgdorferi lysates (bottom panel) were incubated with sera collected from mice following 1 to 9 weeks of B. burgdorferi infection. Antibody response was obvious against all regions; however, a higher response was recorded against Lmp1N (black triangle) than that against Lmp1M (gray triangle) or Lmp1C (white triangle) between 3 and 9 weeks of infection (P < 0.05). (B) Recognition of specific Lmp1 regions by infected murine serum. Recombinant proteins were immunoblotted with sera collected from mice following 6 weeks of B. burgdorferi infection. The additional band recognized in the case of the Lmp1M immunoblot likely represents nonspecific reactivity of the antisera.

Immunization with recombinant unique Lmp1 regions significantly interferes with B. burgdorferi persistence in organ-specific manners.

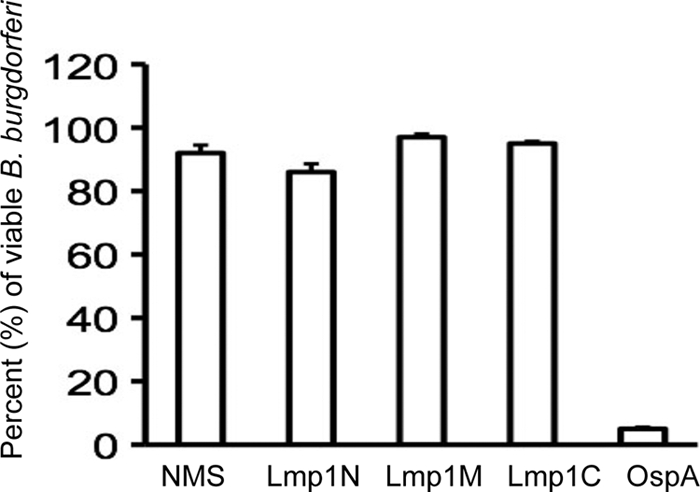

As distinct Lmp1 regions are exposed to the microbial surface (Fig. 3B) and are variably immunogenic during infection (Fig. 4), we next assessed whether immunization of mice with a specific Lmp1 region could influence B. burgdorferi persistence in vivo and severity of disease. Groups of five C3H/HeN mice were separately immunized with recombinant proteins specific to distinct Lmp1 regions. As a control, parallel groups of mice were also immunized with PBS emulsified with an equal amount of adjuvant. ELISA demonstrated the generation of high-titer (>1:50,000) antibodies against each of the target regions. Seven days after the final immunization, mice were challenged with B. burgdorferi (1 × 105 spirochetes/mouse), and the pathogen levels in the heart, joints, and bladder were measured at days 14 and 21 postinfection. B. burgdorferi persistence in the bladder of the immunized mice remained unaltered compared to that in the control immunized mice (P > 0.05) (Fig. 5). However, immunization with Lmp1N significantly reduced pathogen levels in the heart (P < 0.004) (Fig. 5) and in the joints at day 14 of infection (P < 0.001). In contrast, immunization with Lmp1M failed to influence pathogen persistence (P > 0.05) (Fig. 5), while that with Lmp1C reduced B. burgdorferi burden selectively in the joints (P < 0.001) (Fig. 5). Although the levels of development of ankle swelling in all groups of mice remained similar (data not shown), inflammation was less pronounced in the hearts of the mice immunized with Lmp1N than in those of mice immunized with Lmp1M or Lmp1C (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Despite the effects on B. burgdorferi survival in vivo, none of the antisera against the Lmp1 regions had significant borreliacidal activities against the cultured spirochetes in vitro (Fig. 6).

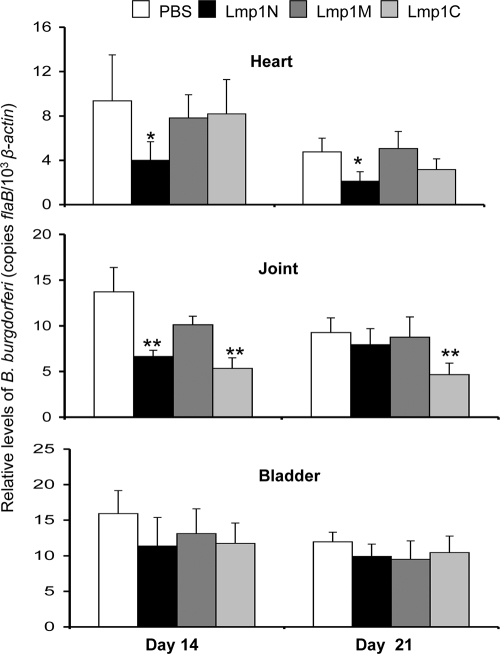

FIG. 5.

Immunization with region-specific Lmp1 proteins reduces B. burgdorferi persistence in murine tissues. Groups of five mice were immunized with recombinant Lmp1 and then challenged with B. burgdorferi (105 cells/mouse). Parallel groups of mice were similarly immunized with PBS containing adjuvant and served as controls. The tissues, including heart, joints, and bladder, were collected at day 14 and day 21 following initial inoculum. Pathogen levels were detected using quantitative RT-PCR analysis with flaB and normalized to the level of the mouse β-actin gene. Mice immunized with Lmp1N had significantly less B. burgdorferi burden in the heart (*, P < 0.004) and in joint tissue at day 14 (P < 0.001). Reduction of spirochete levels in Lmp1C-immunized mice was restricted only to joint tissue (**, P < 0.001). Bars represent the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments.

FIG. 6.

In vitro borreliacidal activities of region-specific Lmp1 antisera. B. burgdorferi was incubated with normal mouse serum (NMS), or region-specific Lmp1 or OspA antisera. The number of viable spirochetes was determined in a dark-field microscope. Data represent the mean number of viable spirochetes per field ± SEM from three independent experiments. Region-specific antisera did not show a significant difference in borreliacidal activities compared to that of normal serum (P > 0.05).

Selective restoration of the N-terminal Lmp1 region in an isolate of Lmp1-deficient B. burgdorferi.

The previous studies suggested that the N-terminal Lmp1 region (Lmp1N) is likely involved in B. burgdorferi infectivity. As Lmp1 protects spirochetes against the bactericidal effect of host antibodies (51), we next wished to assess the involvement of the N-terminal Lmp1 region in this process. Therefore, we engineered an lmp1 deletion mutant (51) to produce a truncated version of Lmp1 encompassing Lmp1N. As the native promoter of lmp1 is unidentified, we first characterized the native promoter and then used it to drive the expression of lmp1N containing amino acids 1 to 380 of the protein. An analysis of the lmp1 (bb0210 locus) upstream and subsequent RT-PCR analysis (Fig. 7 A) suggested that lmp1 is transcribed as a bicistronic transcript along with its upstream gene (bb0209) and that a 200-bp intergenic region upstream of bb0209 likely contains the promoter. The putative promoter region was therefore amplified and fused to the truncated lmp1 open reading frame encoding the N-terminal region (lmp1N), including the leader peptide (Fig. 1A). For stable integration of the complemented construct, the promoter-lmp1N fusion along with an antibiotic resistance cassette, aadA (Fig. 7B), was inserted into the B. burgdorferi chromosome via allelic exchange. PCR analysis confirmed that one of the identified lmp1N-complemented isolates retained all of the known B. burgdorferi plasmids present in the parental isolate (data not shown). RT-PCR and immunoblotting further showed that the lmp1N-complemented isolates expressed truncated lmp1 mRNA (Fig. 7C) and protein (Fig. 7D). The lmp1N-complemented isolates displayed growth kinetics similar to those of lmp1 deletion mutants and the wild-type B. burgdorferi (data not shown). Triton X-114 phase-partitioning assays further demonstrated that the Lmp1N region was primarily extracted into the detergent-enriched phase in complemented isolates (Fig. 7E), similar to full-length Lmp1 in wild type bacteria (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, like full-length Lmp1, Lmp1N was exposed on the borrelial surface, as demonstrated by immunofluorescence analysis using unfixed (Fig. 7F) or fixed (data not shown) cells as well as by a proteinase K accessibility assay (Fig. 7G).

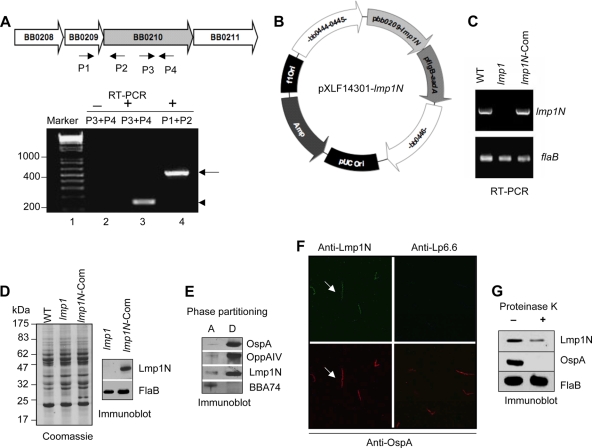

FIG. 7.

Genetic restoration of the lmp1N gene in the lmp1 deletion mutant. (A) lmp1 (bb0210) is cotranscribed with bb0209. The upper panel indicates schematic representation of the bb0209-bb0210 locus in the B. burgdorferi genome. The arrows indicate the positions of primer pairs used in RT-PCR analysis. The lower panel indicates RT-PCR analysis of cotranscription of bb0210 (lmp1) and bb0209. The DNA ladder in base pairs is noted to the left (lane 1). RT-PCR analysis in the absence (−; lane 2) or presence (+, lanes 3 and 4) of reverse transcriptase is shown. A 150-bp portion of bb0210 (lmp1) transcript (arrowhead) was amplified using primers P3 and P4 (lane 3), while a 520-bp portion of bicistronic transcript (arrow) spanning bb0209-bb0210 was amplified using primers P1 and P2 (lane 4). (B) Construction of pXLF14301-lmp1N. The putative promoter and open reading frame of lmp1 encoding Lmp1N and the streptomycin resistance cassette (flgBp-aadA) were cloned into pXLF14301 for recombination into B. burgdorferi chromosome. (C) Detection of the lmp1 gene expressing the lmp1N. Total RNA was isolated from the wild type (WT), lmp1 mutant (lmp1), or lmp1N-complemented (lmp1N-Com) B. burgdorferi strain, converted to cDNA, subjected to PCR analysis with flaB and lmp1 primers, and analyzed on a 1.5% agarose gel. (D) Detection of the Lmp1N protein. Lysates of B. burgdorferi were separated on an SDS-PAGE gel and were either stained with Coomassie blue (left) or transferred to nitrocellulose membrane and blotted with antiserum against Lmp1N or FlaB (right). (E) Triton X-114 phase partitioning of lmp1N-complemented B. burgdorferi proteins. Separated aqueous (lane A)- and detergent (lane D)-phase proteins were immunoblotted using Lmp1N antibody or antibodies against control hydrophilic (BBA74) or amphiphilic (OspA and OppA IV) proteins. (F) Immunofluorescence analysis. Unfixed lmp1N-complemented B. burgdorferi spirochetes were probed with antisera against Lmp1N or Lp6.6 and OspA followed by secondary antibodies, as detailed in Fig. 3B. The images were acquired with the 40× objective of a laser confocal microscope. (G) Lmp1N is surface exposed in the lmp1N-complemented isolate. The lmp1N-complemented B. burgdorferi strain was incubated in the presence (+) or absence (−) of proteinase K and subjected to immunoblotting with antisera against Lmp1N, FlaB, and OspA.

N-terminal Lmp1 region is sufficient to confer B. burgdorferi protection against host immune serum in vitro and contributes to spirochete survival in vivo.

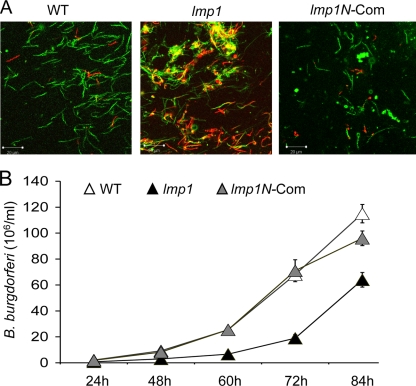

Lmp1 is involved in spirochete resistance to borreliacidal immune sera and pathogen persistence in vivo (51). As the N-terminal Lmp1 region is exposed on the microbial surface, we next assessed its contribution to microbial resistance against the bactericidal activity of immune sera and its persistence in the murine host. To test this, spirochetes were exposed to immune sera collected from mice 2 weeks after initial infection. The results showed that while the lmp1 deletion mutants remained highly susceptible to the borreliacidal effects of immune sera, the lmp1N-complemented isolates displayed viability comparable to that of the wild-type spirochetes (Fig. 8). As previously reported (51), similar viability was also observed in the cases of spirochete exposure to immune serum with or without complement inactivation (data not shown). Together, these data suggested that the N-terminal region is likely involved in Lmp1-mediated B. burgdorferi resistance to bactericidal antibodies developed during infection.

FIG. 8.

Lmp1N protects B. burgdorferi from killing by immune serum in vitro. (A) The wild-type (WT), lmp1 mutant (lmp1), and lmp1N-complemented (lmp1N-Com) B. burgdorferi isolates were incubated with mouse sera collected 2 weeks after B. burgdorferi infection, and spirochete viability was assessed. A representative fluorescence labeling of live and dead spirochetes after 24 h of antiserum treatment, as assessed under a laser confocal microscope, is presented. Live B. burgdorferi spirochetes were stained with Syto 9 (green), and the dead spirochetes were stained with propidium iodide (red). (B) Growth of spirochetes following antiserum treatment. B. burgdorferi spirochetes were treated with antisera as shown in Fig. 8A, and following 24 h, 1 μl of medium was inoculated into 1 ml of fresh medium and the growth of the spirochetes was assessed by dark-field microscopy at the indicated time periods.

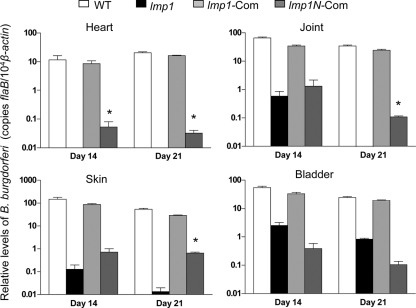

Finally, we also assessed the role of N-terminal Lmp1 region in spirochete persistence in mice. Groups of mice (3 animals/group) were infected with equal numbers (105 cells/mouse) of wild-type spirochetes, the lmp1 mutant isolate, or the lmp1 mutant isolates complemented with either full-length lmp1 (51) or the lmp1N construct. Spirochete levels in murine skin, heart, joint, and bladder tissues were assessed at day 14 and day 21 following infection. The mice were also monitored for joint swelling on a weekly basis from the day of spirochete inoculation until sacrifice. The results are in agreement with a previous study (51) demonstrating that the effects of lmp1 deletion in spirochete persistence were most prominent in the heart and least prominent in the bladder (Fig. 9). However, in comparison with the lmp1 deletion mutant, lmp1N-complemented isolates persisted at significantly higher levels in mice, especially in the heart at day 14 (P < 0.01) (Fig. 9) and in the heart, joints, and skin samples at day 21 (P < 0.05) (Fig. 9). Compared to the wild-type or full-length lmp1-complemented B. burgdorferi spirochetes, however, the level of the lmp1N-complemented spirochetes remained dramatically lower (Fig. 9) and was unable to induce inflammation in the heart and joints (data not shown).

FIG. 9.

Genetic restoration of Lmp1N partially rescues phenotypic defects of lmp1 mutants to persist in mice. Groups of mice (3 animals/group, 105 spirochetes/mouse) were injected with wild-type B. burgdorferi (WT; white bars), the lmp1 mutant (lmp1; black bars), or lmp1-complemented (lmp1-Com; light gray bars) and lmp1N-complemented (lmp1N-Com; dark gray bars) B. burgdorferi strains. The spirochete burden was analyzed at day 14 and day 21 in heart, joint, skin, and bladder tissues following spirochete infection by measuring copies of the B. burgdorferi flaB gene, which were normalized to the mouse β-actin gene. Bars represent the mean ± SEM of four quantitative RT-PCR analyses of B. burgdorferi levels derived from two independent animal experiments. A significant increase in the B. burgdorferi levels in the heart at day 14 and heart, joint, and skin tissues at day 21 were recorded in cases of infection with lmp1N-complemented isolates, compared to that of lmp1 mutant isolates (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

B. burgdorferi Lmp1 plays an important role in pathogen persistence in the murine host (51). However, the occurrence of unique N-terminal, middle, or C-terminal regions of the protein suggests that Lmp1 could be a multifunctional protein. Here we show that Lmp1 is an integral membrane protein that is exposed to the microbial surface via multiple immunogenic regions. Antibody-mediated targeting of recombinant Lmp1 representing specific regions differentially influenced B. burgdorferi persistence in specific organs. This raises the possibility that the function of diverse Lmp1 regions could be more pronounced for pathogen persistence in a specific host tissue environment. Additionally, the data suggest that the N-terminal Lmp1 region contributes to the spirochete's ability to resist borreliacidal activities of host immune sera and enhance pathogen survival during infection.

Our data strongly suggest that Lmp1 is an integral membrane protein likely harboring three unique surface-exposed regions. While the N-terminal region lacks homology to known proteins, the middle and C-terminal regions house several potential TPR motifs, which are known to mediate diverse protein-protein interactions and the assembly of multiprotein complexes in other organisms (1, 17, 22, 42). Thus, the predicted structure of Lmp1 contains multiple TPR motifs that result in a likely multidomain, multifunctional protein that is involved in diverse cellular functions, which is similar to the transmembrane mitochondrial translocase Tom70 (50) and the O-linked GlcNAc transferase (46). Alternatively, diverse Lmp1 regions could be associated with the same function that is reflected at different levels in various tissue environments. Nevertheless, as an integral membrane protein, Lmp1 could be involved in the interaction with unidentified borrelial proteins and/or could possibly be involved in host-pathogen interaction (3). Additionally, while the N-terminal region lacks TPR or other known protein motifs, it maintains its surface topology even when produced as a truncated Lmp1 protein (Fig. 7E to G), suggesting its independent association with the borrelial membrane, which also contributes to B. burgdorferi survival, most likely in environments involving pathogen interaction with host-generated bactericidal antibodies.

Borreliacidal antibodies generated during infection can contribute to microbial clearance, thereby affecting pathogenesis (16). Antibodies could also influence microbial virulence without apparent effects on pathogen levels. For example, antiserum against decorin binding protein A or arthritis-related protein (Arp) reduces murine disease without an effect on spirochete levels (7). Moreover, Arp induces arthritis-resolving immunity but does not influence the resolution of carditis, suggesting that the protective immunity and disease-resolving immunity involving different host organs are independent events that may be correlated with distinct B. burgdorferi target antigens or immune responses (19). Antibodies raised against truncated Lmp1 proteins were unable to exert borreliacidal effects in vitro. Notably, in our study, immunization with the middle region also failed to influence B. burgdorferi virulence or Lyme disease pathogenesis. These results could be the consequence of poor accessibility of the antibodies to the antigenic epitopes of Lmp1 during the infectious process. Overall, they suggest that the target epitopes may be inaccessible when the protein is in its native conformation. This could either due to their structural localization within the protein, which results in a lack of epitope exposure, or alternatively because of the topological constraints when the protein is inserted in the membrane, possibly resulting in greater subsurface localization. Importantly, antibodies against Lmp1N and Lmp1C, both of which are exposed on the microbial surface, exerted a markedly different influence on spirochete persistence and inflammation. Although a precise reason for such disparate effects of region-specific antibodies remains unclear, it is tempting to speculate that the role of a specific Lmp1 region could be relevant to spirochete persistence in specific host tissue environments or unique niches in the mammalian host. Further elucidation of the molecular function of Lmp1, an important B. burgdorferi virulence determinant, will likely shed light on a complex mechanism of pathogen persistence in the host and also will likely help contribute to the development of novel ways to interfere with the spirochete during infection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the American Heart Association and NIH/NIAID (award no. AI080615) to U.P. and grants HR09-002 and AI059373 from the Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science and Technology and NIH/NIAID, respectively, to D.R.A.

We sincerely thank Melissa J. Caimano and Justin D. Radolf for providing BBA74 antibodies. We are also thankful to Adam S. Coleman, Manish Kumar, and Bridgett Duarte for excellent assistance with this study.

Editor: A. Camilli

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 August 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://iai.asm.org/.

The authors have paid a fee to allow immediate free access to this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alag, R., N. Bharatham, A. Dong, T. Hills, A. Harikishore, A. A. Widjaja, S. G. Shochat, R. Hui, and H. S. Yoon. 2009. Crystallographic structure of the tetratricopeptide repeat domain of Plasmodium falciparum FKBP35 and its molecular interaction with Hsp90 C-terminal pentapeptide. Protein Sci. 18:2115-2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, J. F. 1989. Epizootiology of Borrelia in Ixodes tick vectors and reservoir hosts. Rev. Infect. Dis. 11(Suppl. 6):S1451-S1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antonara, S., R. M. Chafel, M. LaFrance, and J. Coburn. 2007. Borrelia burgdorferi adhesins identified using in vivo phage display. Mol. Microbiol. 66:262-276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnold, K., L. Bordoli, J. Kopp, and T. Schwede. 2006. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics 22:195-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barthold, S. W., M. S. deSouza, J. L. Janotka, A. L. Smith, and D. H. Persing. 1993. Chronic Lyme borreliosis in the laboratory mouse. Am. J. Pathol. 143:959-971. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barthold, S. W., M. DeSouza, E. Fikrig, and D. H. Persing. 1992. Lyme borreliosis in the laboratory mouse, p. 223-242. In S. E. Schuster (ed.), Lyme disease. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 7.Barthold, S. W., E. Hodzic, S. Tunev, and S. Feng. 2006. Antibody-mediated disease remission in the mouse model of Lyme borreliosis. Infect. Immun. 74:4817-4825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barthold, S. W., D. H. Persing, A. L. Armstrong, and R. A. Peeples. 1991. Kinetics of Borrelia burgdorferi: dissemination and evolution of disease following intradermal inoculation of mice. Am. J. Pathol. 163:263-273. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blevins, J. S., K. E. Hagman, and M. V. Norgard. 2008. Assessment of decorin-binding protein A to the infectivity of Borrelia burgdorferi in the murine models of needle and tick infection. BMC Microbiol. 8:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bockenstedt, L. K., I. Kang, C. Chang, D. Persing, A. Hayday, and S. W. Barthold. 2001. CD4+ T helper 1 cells facilitate regression of murine Lyme carditis. Infect. Immun. 69:5264-5269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brooks, C. S., P. S. Hefty, S. E. Jolliff, and D. R. Akins. 2003. Global analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi genes regulated by mammalian host-specific signals. Infect. Immun. 71:3371-3383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brooks, C. S., S. R. Vuppala, A. M. Jett, and D. R. Akins. 2006. Identification of Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface proteins. Infect. Immun. 74:296-304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bubeck-Martinez, S. 2005. Immune evasion of the Lyme disease spirochetes. Front. Biosci. 10:873-878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carroll, J. A., C. F. Garon, and T. G. Schwan. 1999. Effects of environmental pH on membrane proteins in Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 67:3181-3187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coleman, A. S., X. Yang, M. Kumar, X. Zhang, K. Promnares, D. Shroder, M. R. Kenedy, J. F. Anderson, D. R. Akins, and U. Pal. 2008. Borrelia burgdorferi complement regulator-acquiring surface protein 2 does not contribute to complement resistance or host infectivity. PLoS One 3:3010e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Connolly, S. E., and J. L. Benach. 2005. The versatile roles of antibodies in Borrelia infections. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:411-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cortajarena, A. L., J. Wang, and L. Regan. 2010. Crystal structure of a designed tetratricopeptide repeat module in complex with its peptide ligand. FEBS J. 277:1058-1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elias, A. F., P. E. Stewart, D. Grimm, M. J. Caimano, C. H. Eggers, K. Tilly, J. L. Bono, D. R. Akins, J. D. Radolf, T. G. Schwan, and P. Rosa. 2002. Clonal polymorphism of Borrelia burgdorferi strain B31 MI: implications for mutagenesis in an infectious strain background. Infect. Immun. 70:2139-2150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng, S., E. Hodzic, and S. W. Barthold. 2000. Lyme arthritis resolution with antiserum to a 37-kilodalton Borrelia burgdorferi protein. Infect. Immun. 68:4169-4173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frank, K. L., S. F. Bundle, M. E. Kresge, C. E. Eggers, and D. S. Samuels. 2003. aadA confers streptomycin resistance in Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 185:6723-6727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilbert, M. A., E. A. Morton, S. F. Bundle, and D. S. Samuels. 2007. Artificial regulation of ospC expression in Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 63:1259-1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goebl, M., and M. Yanagida. 1991. The TPR snap helix: a novel protein repeat motif from mitosis to transcription. Trends Biochem. Sci. 16:173-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grimm, D., K. Tilly, R. Byram, P. E. Stewart, J. G. Krum, D. M. Bueschel, T. G. Schwan, P. F. Policastro, A. F. Elias, and P. A. Rosa. 2004. Outer-surface protein C of the Lyme disease spirochete: a protein induced in ticks for infection of mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:3142-3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu, L. T., and M. S. Klempner. 1997. Host-pathogen interactions in the immunopathogenesis of Lyme disease. J. Clin. Immunol. 17:354-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jewett, M. W., K. Lawrence, A. C. Bestor, K. Tilly, D. Grimm, P. Shaw, M. VanRaden, F. Gherardini, and P. A. Rosa. 2007. The critical role of the linear plasmid lp36 in the infectious cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 64:1358-1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar, M., X. Yang, A. S. Coleman, and U. Pal. 2010. BBA52 facilitates Borrelia burgdorferi transmission from feeding ticks to murine hosts. J. Infect. Dis. 201:1084-1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lenhart, T. R., and D. R. Akins. 2010. Borrelia burgdorferi locus BB0795 encodes a BamA orthologue required for growth and efficient localization of outer membrane proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 75:692-709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li, X., U. Pal, N. Ramamoorthi, X. Liu, D. C. Desrosiers, C. H. Eggers, J. F. Anderson, J. D. Radolf, and E. Fikrig. 2007. The Lyme disease agent Borrelia burgdorferi requires BB0690, a Dps homologue, to persist within ticks. Mol. Microbiol. 63:694-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liang, F. T., F. K. Nelson, and E. Fikrig. 2002. Molecular adaptation of Borrelia burgdorferi in the murine host. J. Exp. Med. 196:275-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mulay, V., M. J. Caimano, D. Liveris, D. C. Desrosiers, J. D. Radolf, and I. Schwartz. 2007. Borrelia burgdorferi BBA74, a periplasmic protein associated with the outer membrane, lacks porin-like properties. J. Bacteriol. 189:2063-2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nadelman, R. B., and G. P. Wormser. 1998. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet 352:557-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Narasimhan, S., M. J. Caimano, F. T. Liang, F. Santiago, M. Laskowski, M. T. Philipp, A. R. Pachner, J. D. Radolf, and E. Fikrig. 2003. Borrelia burgdorferi transcriptome in the central nervous system of non-human primates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:15953-15958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Narasimhan, S., F. Santiago, R. A. Koski, B. Brei, J. F. Anderson, D. Fish, and E. Fikrig. 2002. Examination of the Borrelia burgdorferi transcriptome in Ixodes scapularis during feeding. J. Bacteriol. 184:3122-3125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ojaimi, C., C. Brooks, S. Casjens, P. Rosa, A. Elias, A. Barbour, A. Jasinskas, J. Benach, L. Katona, J. Radolf, M. Caimano, J. Skare, K. Swingle, D. Akins, and I. Schwartz. 2003. Profiling of temperature-induced changes in Borrelia burgdorferi gene expression by using whole genome arrays. Infect. Immun. 71:1689-1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pal, U., R. R. Montgomery, D. Lusitani, P. Voet, V. Weynants, S. E. Malawista, Y. Lobet, and E. Fikrig. 2001. Inhibition of Borrelia burgdorferi-tick interactions in vivo by outer surface protein A antibody. J. Immunol. 166:7398-7403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pal, U., P. Wang, F. Bao, X. Yang, S. Samanta, R. Schoen, G. P. Wormser, I. Schwartz, and E. Fikrig. 2008. Borrelia burgdorferi basic membrane proteins A and B participate in the genesis of Lyme arthritis. J. Exp. Med. 205:133-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pal, U., X. Yang, M. Chen, L. K. Bockenstedt, J. F. Anderson, R. A. Flavell, M. V. Norgard, and E. Fikrig. 2004. OspC facilitates Borrelia burgdorferi invasion of Ixodes scapularis salivary glands. J. Clin. Invest. 113:220-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Promnares, K., M. Kumar, D. Y. Shroder, X. Zhang, J. F. Anderson, and U. Pal. 2009. Borrelia burgdorferi small lipoprotein Lp6.6 is a member of multiple protein complexes in the outer membrane and facilitates pathogen transmission from ticks to mice. Mol. Microbiol. 74:112-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Purser, J. E., M. B. Lawrenz, M. J. Caimano, J. K. Howell, J. D. Radolf, and S. J. Norris. 2003. A plasmid-encoded nicotinamidase (PncA) is essential for infectivity of Borrelia burgdorferi in a mammalian host. Mol. Microbiol. 48:753-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Revel, A. T., J. S. Blevins, C. Almazan, L. Neil, K. M. Kocan, J. de la Fuente, K. E. Hagman, and M. V. Norgard. 2005. bptA (bbe16) is essential for the persistence of the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi, in its natural tick vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:6972-6977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Revel, A. T., A. M. Talaat, and M. V. Norgard. 2002. DNA microarray analysis of differential gene expression in Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease spirochete. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:1562-1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scheufler, C., A. Brinker, G. Bourenkov, S. Pegoraro, L. Moroder, H. Bartunik, F. U. Hartl, and I. Moarefi. 2000. Structure of TPR domain-peptide complexes: critical elements in the assembly of the Hsp70-Hsp90 multichaperone machine. Cell 101:199-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schwan, T. G., J. Piesman, W. T. Golde, M. C. Dolan, and P. A. Rosa. 1995. Induction of an outer surface protein on Borrelia burgdorferi during tick feeding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92:2909-2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seiler, K. P., and J. J. Weis. 1996. Immunity to Lyme disease: protection, pathology and persistence. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 8:503-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seshu, J., M. D. Esteve-Gassent, M. Labandeira-Rey, J. H. Kim, J. P. Trzeciakowski, M. Hook, and J. T. Skare. 2006. Inactivation of the fibronectin-binding adhesin gene bbk32 significantly attenuates the infectivity potential of Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 59:1591-1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shen, A., H. D. Kamp, A. Grundling, and D. E. Higgins. 2006. A bifunctional O-GlcNAc transferase governs flagellar motility through anti-repression. Genes Dev. 20:3283-3295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shi, Y., Q. Xu, K. McShan, and F. T. Liang. 2008. Both decorin-binding proteins A and B are critical for the overall virulence of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 76:1239-1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Steere, A. C., J. Coburn, and L. Glickstein. 2004. The emergence of Lyme disease. J. Clin. Invest. 113:1093-1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tokarz, R., J. M. Anderton, L. I. Katona, and J. L. Benach. 2004. Combined effects of blood and temperature shift on Borrelia burgdorferi gene expression as determined by whole genome DNA array. Infect. Immun. 72:5419-5432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamamoto, H., K. Fukui, H. Takahashi, S. Kitamura, T. Shiota, K. Terao, M. Uchida, M. Esaki, S. Nishikawa, T. Yoshihisa, K. Yamano, and T. Endo. 2009. Roles of Tom70 in import of presequence-containing mitochondrial proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 284:31635-31646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang, X., A. S. Coleman, J. Anguita, and U. Pal. 2009. A chromosomally encoded virulence factor protects the Lyme disease pathogen against host-adaptive immunity. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang, X. F., U. Pal, S. M. Alani, E. Fikrig, and M. V. Norgard. 2004. Essential role for OspA/B in the life cycle of the Lyme disease spirochete. J. Exp. Med. 199:641-648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang, X., X. Yang, M. Kumar, and U. Pal. 2009. BB0323 function is essential for Borrelia burgdorferi virulence and persistence through tick-rodent transmission cycle. J. Infect. Dis. 200:1318-1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.