Abstract

Clostridium perfringens type C isolates cause enteritis necroticans in humans or necrotizing enteritis and enterotoxemia in domestic animals. Type C isolates always produce alpha toxin and beta toxin but often produce additional toxins, e.g., beta2 toxin or enterotoxin. Since plasmid carriage of toxin-encoding genes has not been systematically investigated for type C isolates, the current study used Southern blot hybridization of pulsed-field gels to test whether several toxin genes are plasmid borne among a collection of type C isolates. Those analyses revealed that the surveyed type C isolates carry their beta toxin-encoding gene (cpb) on plasmids ranging in size from ∼65 to ∼110 kb. When present in these type C isolates, the beta2 toxin gene localized to plasmids distinct from the cpb plasmid. However, some enterotoxin-positive type C isolates appeared to carry their enterotoxin-encoding cpe gene on a cpb plasmid. The tpeL gene encoding the large clostridial cytotoxin was localized to the cpb plasmids of some cpe-negative type C isolates. The cpb plasmids in most surveyed isolates were found to carry both IS1151 sequences and the tcp genes, which can mediate conjugative C. perfringens plasmid transfer. A dcm gene, which is often present near C. perfringens plasmid-borne toxin genes, was identified upstream of the cpb gene in many type C isolates. Overlapping PCR analyses suggested that the toxin-encoding plasmids of the surveyed type C isolates differ from the cpe plasmids of type A isolates. These findings provide new insight into plasmids of proven or potential importance for type C virulence.

Clostridium perfringens isolates are classified into five toxinotypes (A to E) based upon the production of four (α, β, ɛ, and ι) typing toxins (29). Each toxinotype is associated with different diseases affecting humans or animals (25). In livestock species, C. perfringens type C isolates cause fatal necrotizing enteritis and enterotoxemia, where toxins produced in the intestines absorb into the circulation to damage internal organs. Type C-mediated animal diseases result in serious economic losses for agriculture (25). In humans, type C isolates cause enteritis necroticans, which is also known as pigbel or Darmbrand (15, 17), an often fatal disease that involves vomiting, diarrhea, severe abdominal pain, intestinal necrosis, and bloody stools. Acute cases of pigbel, resulting in rapid death, may also involve enterotoxemia (15).

By definition, type C isolates must produce alpha and beta toxins (24, 29). Alpha toxin, a 43-kDa protein encoded by the chromosomal plc gene, has phospholipase C, sphingomyelinase, and lethal properties (36). Beta toxin, a 35-kDa polypeptide, forms pores that lyse susceptible cells (28, 35). Recent studies demonstrated that beta toxin is necessary for both the necrotizing enteritis and lethal enterotoxemia caused by type C isolates (33, 37). Besides alpha and beta toxins, type C isolates also commonly express beta2 toxin, perfringolysin O, or enterotoxin (11).

There is growing appreciation that naturally occurring plasmids contribute to both C. perfringens virulence and antibiotic resistance. For example, all typing toxins, except alpha toxin, can be encoded by genes carried on large plasmids (9, 19, 26, 30-32). Other C. perfringens toxins, such as the enterotoxin or beta2 toxin, can also be plasmid encoded (6, 8, 12, 34). Furthermore, conjugative transfer of several C. perfringens antibiotic resistance plasmids or toxin plasmids has been demonstrated, supporting a key role for plasmids in the dissemination of virulence or antibiotic resistance traits in this bacterium (2).

Despite their pathogenic importance, the toxin-encoding plasmids of C. perfringens only recently came under intensive study (19, 26, 27, 31, 32). The first carefully analyzed C. perfringens toxin plasmids were two plasmid families carrying the enterotoxin gene (cpe) in type A isolates (6, 8, 12, 26). One of those cpe plasmid families, represented by the ∼75-kb prototype pCPF5603, has an IS1151 sequence present downstream of the cpe gene and also carries the cpb2 gene, encoding beta2 toxin. A second cpe plasmid family of type A isolates, represented by the ∼70-kb prototype pCPF4969, lacks the cpb2 gene and carries an IS1470-like sequence, rather than an IS1151 sequence, downstream of the cpe gene. The pCPF5603 and pCPF4969 plasmid families share an ∼35-kb region that includes transfer of a clostridial plasmid (tcp) locus (26). The presence of this tcp locus likely explains the demonstrated conjugative transfer of some cpe plasmids (5) since a similar tcp locus was shown to mediate conjugative transfer of the C. perfringens tetracycline resistance plasmid pCW3 (2).

The iota toxin-encoding plasmids of type E isolates are typically larger (up to ∼135 kb) than cpe plasmids of type A isolates (19). Plasmids carrying iota toxin genes often encode other potential virulence factors, such as lambda toxin and urease, as well as a tcp locus (19). Many iota toxin plasmids of type E isolates share, sometimes extensively, sequences with cpe plasmids of type A isolates (19). It has been suggested that many iota toxin plasmids evolved from the insertion of a mobile genetic element carrying the iota toxin genes near the plasmid-borne cpe gene in a type A isolate, an effect that silenced the cpe gene in many type E isolates (3, 19).

Plasmids carrying the epsilon toxin gene (etx) vary from ∼48 kb to ∼110 kb among type D isolates (32). In part, these etx plasmid size variations in type D isolates reflect differences in toxin gene carriage. For example, the small ∼48-kb etx plasmids present in some type D isolates lack both the cpe gene and the cpb2 gene. In contrast, larger etx plasmids present in other type D isolates often carry the cpe gene, the cpb2 gene, or both the cpe and cpb2 genes. Thus, the virulence plasmid diversity of type D isolates spans from carriage of a single toxin plasmid, possessing from one to three distinct toxin genes, to carriage of three different toxin plasmids.

In contrast to the variety of etx plasmids found among type D isolates, type B isolates often or always share the same ∼65-kb etx plasmid, which is related to pCPF5603 but lacks the cpe gene (27). This common etx plasmid of type B isolates, which carries a cpb2 gene and the tcp locus, is also present in a few type D isolates. Most type B isolates surveyed to date carry their cpb gene, encoding beta toxin, on an ∼90-kb plasmid, although a few of those type B isolates possess an ∼65-kb cpb plasmid distinct from their ∼65-kb etx plasmid (31).

To our knowledge, the cpb gene has been mapped to a plasmid (uncharacterized) in only a single type C strain (16). Furthermore, except for the recent localization of the cpe gene to plasmids in type C strains (20), plasmid carriage of other potential toxin genes in type C isolates has not been investigated. Considering the limited information available regarding the toxin plasmids of type C isolates, our study sought to systematically characterize the size, diversity, and toxin gene carriage of toxin plasmids in a collection of type C isolates. Also, to gain insight into possible mobilization of the cpb gene by insertion sequences or conjugative transfer, the presence of IS1151 sequences or the tcp locus on type C toxin plasmids was investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial cells, media, and reagents.

All type C isolates examined in this study are listed and described in Table 1. Carriage of cpb, plc, cpb2, and cpe genes by these isolates was determined in a previous study by multiplex PCR (11). The type C isolates were grown overnight at 37°C under anaerobic conditions on Shahidi-Ferguson perfringens (SFP) agar (Difco Laboratories) containing 0.04% d-cycloserine (Sigma-Aldrich) to maintain culture purity. For growth of broth cultures, fluid thioglycolate (FTG) medium (Difco Laboratories) and TGY medium (3% tryptic soy broth [Becton Dickinson] containing 2% glucose [Fisher Scientific], 1% yeast extract [Becton Dickinson], and 0.1% sodium thioglycolate [Sigma-Aldrich]) were used.

TABLE 1.

Summary of plasmid sizes in C. perfringens type C isolates

| Isolatea | Apparent size (kb) of plasmid containing: |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cpb (beta toxin) | cpe (enterotoxin) | tpeL (large cytotoxin) | tcpH (conjugative transfer) | rep (replication) | IS1151 (insertion sequence) | cpb2 (beta 2 toxin) | |

| CN882c | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | ||

| CN885d | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | ||

| CN886d | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | ||

| CN887c | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | ||

| CN1797d | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | ||

| CN2078d | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 | ||

| CN3711e | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | ||

| CN3717c | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | ||

| CN3728e | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | ||

| CN3732e | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | ||

| CN3753d | 85 | 85 | 85 | 85/65 | 85/110 | ||

| CN3763d | 75 | 110 | 75/110 | 75/110 | 75/110 | ||

| CN5383b | 110 | 65 | 65/110 | 65/110 | 110 | ||

| CN5388b | 110 | 90 | 90/110 | 90/110 | 90/110 | 90 | |

| NCTC10719f | 95 | 95 | 95 | 65/95 | 95 | 65 | |

| Bar3b | 110 | 65 | 65/110 | 65/110 | 110 | 75 | |

Isolates with a “CN” prefix originated from the Burroughs-Wellcome collection of C. perfringens isolates collected globally during the 1930s to 1960s and were provided by Russell Wilkinson (University of Melbourne), Bar3 is from Australia and was provided by Francisco Uzal, and NCTC10719 came originally from Denmark.

Originated from human pigbel cases.

Originated from diseased sheep.

Originated from animals (species unknown).

Originated from diseased cattle.

Originated from diseased pigs.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE).

For PFGE analysis, individual C. perfringens type C isolates were grown in FTG broth overnight at 37°C. A 0.1-ml aliquot of those starter cultures was then inoculated into 10 ml of TGY medium. After overnight growth at 37°C, the TGY cultures were used to prepare C. perfringens genomic DNA agarose plugs. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and washed in TES buffer (1 M Tris, 0.5 M EDTA, 5 M sucrose [pH 8.0]). The washed cells were resuspended in 0.2 ml of Tris-EDTA buffer and embedded in an equal volume of melted 2% Certified low-melt agarose (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The mixture was dispensed into plug molds, solidified at 4°C, and then cut into 2- to 3-mm slices. The agarose-embedded cells were lysed by incubation, with gentle shaking of the plugs overnight at 37°C in lysis buffer (0.5 M EDTA [pH 8.0], 0.5% [vol/vol] Sarkosyl, 0.5% lysozyme [Sigma], 0.4% deoxycholic acid). Finally, the lysed plugs were incubated for 2 days at 55°C in 0.2% proteinase K (Gene Choice)-0.5 M EDTA (pH 8.0) buffer.

PFGE was performed with 1% agarose gels by using a CHEF-DR II system (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer at 14°C. For the undigested DNA plugs, the running parameters were as follows: initial pulse, 1 s; final pulse, 25 s; voltage, 6 V/cm; and time, 24 h. For isolates that showed Southern blot signal colocalization using probes for two different open reading frames (ORFs) (as described below), DNA plugs were digested with the restriction endonucleases ApaI, AvaI, ClaI, KpnI, NcoI, NheI, SphI, and XhoI (New England Biolabs). Briefly, a plug slice (approximately one-sixth of the plug) was incubated overnight, at the proper temperature as instructed by the enzyme manufacturer, in 30 μl of 10× commercial restriction endonuclease buffer, 4 μl of a selected enzyme, and 266 μl of distilled water. The digested plugs were then electrophoresed in the CHEF-DR II system (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer at 14°C. The running parameters were as follows: initial pulse, 1 s; final pulse, 12 s; voltage, 6 V/cm; and time, 15 h.

Pulsed-field gel Southern blot analyses.

Digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled DNA probes were prepared using a PCR DIG probe synthesis kit (Roche). Primers used for amplifying internal cpb, cpe, IS1151, tcpH, rep, tpeL, and cpb2 gene sequences (Table 1 lists what each of these genes encodes) have been described previously (19, 31, 32). The DIG-labeled probes were then used to perform Southern hybridization of pulsed-field gels using a previously described technique (32). CSPD substrate (Roche) was used for detection of hybridized probes according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Overlapping PCR analyses to determine whether type C isolates carry the conserved or variable regions of pCPF5603 and pCPF4969.

The DNA for these overlapping, short-range PCRs was obtained from C. perfringens colony lysates as described previously (26). Each PCR mixture (20 μl) contained 2 μl of template DNA, 10 μl of Taq complete 2× mastermix (New England Biolabs), and 1 μl of each primer pair (1 μM final concentration). The primers used for investigating the presence of pCPF5603/pCPF4969 conserved regions and pCPF5603 or pCPF4969 variable regions in type C isolates have been described previously (26). The PCR amplification conditions used for these overlapping PCR analyses were 1 cycle of 95°C for 2 min and 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 1 min, and 68°C for 1 min 40 s, followed by a single extension of 68°C for 10 min. The PCR products were electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide for visualization.

PCR analyses of tpeL carriage and linkage analysis of the cpb and tpeL genes in type C isolates.

A PCR survey was performed to evaluate carriage among type C isolates of the tpeL gene, encoding the C. perfringens large cytotoxin (TpeL). The primers used for these PCR analyses were described previously (28). To evaluate potential linkage between the tpeL and cpb genes in type C isolates by overlapping PCR, primers were used from a former study (31) based upon the unfinished C. perfringens type B strain ATCC 3626 genome sequence publicly released by the J. Craig Venter Institute (JCVI). The PCR amplification conditions used for this overlapping PCR assay were 1 cycle of 94°C for 3 min and 35 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 68°C for 1 min 30 s, followed by a single extension of 68°C for 10 min. The PCR products were electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide for visualization.

For long-range PCR to attempt connecting the tpeL and cpb genes, DNA was isolated from type C strains CN882, CN886, CN3711, CN3717, CN3732, and NCTC10719 by using a MasterPure Gram-positive DNA purification kit (Epicentre). Each PCR mixture contained 1 μl of template DNA, 25 μl of Taq long-range complete 2× mix (New England Biolabs), and 1 μl each of the primer pair SeqR5 and cpbF3 (1 μM final concentration) (31). The reaction mixtures, with a total volume of 50 μl, were placed in a thermocycler (Techne) and subjected to the following amplification conditions: 1 cycle of 95°C for 2 min, 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 56°C for 40 s, and 65°C for 3 min, and a single extension at 65°C for 10 min. PCR products were then electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel, which was stained with ethidium bromide for product visualization. The long-range PCR products amplified from CN886 and NCTC10719 were PCR cloned into the pCR2.1-TOPO vector (Invitrogen), and those inserts were then sequenced at the University of Pittsburgh Core sequencing facility using previously described primers (31).

PCR linkage of the cpb gene with IS1151 and the dcm gene in type C isolates.

Based upon the JCVI JGS1495 sequence, a series of primers were constructed (Table 2) to evaluate, by overlapping PCR, a potential linkage between the cpb gene and IS1151 sequences or the dcm gene in type C isolates. PCR conditions for these amplifications were 1 cycle of 94°C for 3 min and 35 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 68°C for 1 min 30 s, followed by a single extension of 68°C for 10 min. PCR products were run on a 1% gel and stained with ethidium bromide for visualization.

TABLE 2.

PCR primers used to link the cpb gene to the dcm gene

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | PCR product (size [kb]) |

|---|---|---|

| F1 R1 | TCTAGTTACCCTAGAAAGCATTACT | A (1.0) |

| GCTCTAAAAAAGAGCTTAAAAGCA | ||

| F2 R2 | ATGATAAGTGAGGACCTTCC | B (1.2) |

| TGGTCATATTTCATGTATAACT | ||

| F3 R3 | CTGCTTTTAAGCTCTTTTTTAGAGC | C (1.1) |

| CCTCCTTTTGTATATAGATGATCTG | ||

| F4 R4 | AGTTATACATGAAATATGACCA | D (1.1) |

| CCAGTTAACACCATTCCAATTAAGA | ||

| F5 R5 | CAGATCATCTATATACAAAAGGGAGAGG | E (0.9) |

| CCCAGCCATCTTATACATTTG |

Reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) analysis of tpeL gene expression by type C isolates.

RT-PCR analyses were performed to evaluate whether the tpeL gene is expressed by tpeL-positive type C isolates. Strains were grown as described above, and cells were collected by centrifugation. Total bacterial RNA was extracted from the pelleted cells using a previously described method (38). All RNA samples were treated with DNase I at 37°C for 30 min. RT-PCRs were then performed on those DNase-treated RNA samples by using an AccessQuick RT-PCR system (Promega). Briefly, 100 ng of each RNA sample was reverse transcribed to cDNA at 45°C for 1 h and then used as a template for PCR (35 cycles, each consisting of denaturing at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 55°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 1 min) with tpeL-specific primers (31).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The tpeL to cpb sequences determined for CN886 and NCTC10719 in this study were submitted to GenBank under the accession numbers HM480840 and HM480841.

RESULTS

Characterization of cpb gene location in type C isolates.

Studies from several laboratories have established that Southern blot assays of pulsed-field gels provide useful insight into the size, diversity, and gene carriage of C. perfringens toxin plasmids (3, 7, 8, 10, 12, 16, 19, 26, 27, 31, 32). Furthermore, those studies have also shown that the PFGE conditions used in the current study do not allow C. perfringens chromosomal DNA to enter pulsed-field gels unless first digested by restriction enzymes (8, 16, 19, 26, 27, 31, 32).

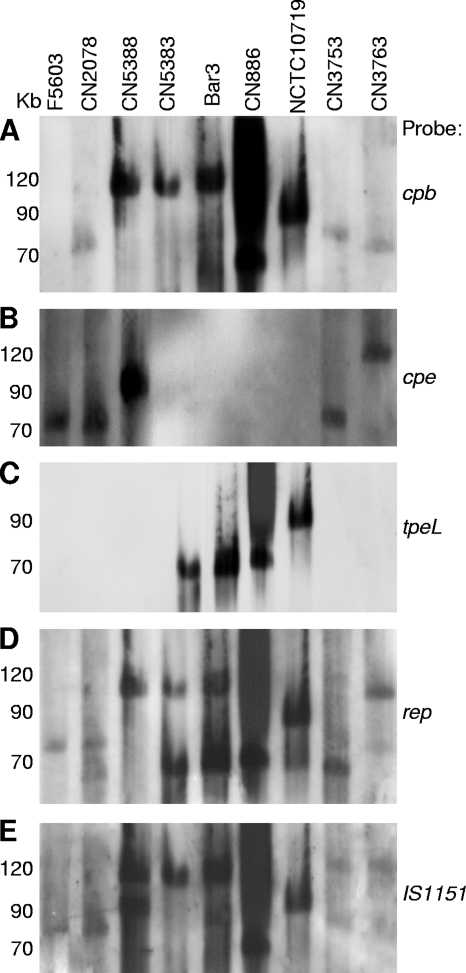

Since type C isolates must (by definition) produce beta toxin, the current study first subjected DNA from ∼30 type C isolates to PFGE, followed by Southern blot hybridization with a cpb probe (Fig. 1 A and Table 1), in order to evaluate whether the cpb gene is typically plasmid borne among type C isolates. As noted previously for some C. perfringens type A and type D isolates, DNA from certain type C isolates exhibited noticeable smearing on these Southern blots (26, 32). This smearing is indicative of high nuclease levels and prohibited further analysis of those isolates. However, cpb probe hybridization was discernible on Southern blots of 16 surveyed type C isolates. Each of these surveyed type C isolates was found to carry a plasmid-borne cpb gene. As expected for a negative control, the cpb probe did not hybridize with DNA from type A isolate F5603, which is cpb negative by PCR (Fig. 1A and data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Southern hybridization analyses of pulsed-field gels run with DNA extracted from representative type C isolates CN2078, CN5388, CN5383, Bar3, CN886, NCTC10719, CN3753, and CN3763. Type A isolate F5603 (cpe positive, cpb negative) is included as a control. (A) The blot was hybridized with a cpb-specific probe. (B) The blot from panel A was stripped and hybridized with a cpe-specific probe. (C) The blot from panel B was stripped and rehybridized with a tpeL-specific probe. (D) The blot from panel C was stripped and rehybridized with a rep-specific probe. (E) The blot from panel D was stripped and rehybridized with an IS1151-specific probe. Migration of molecular size markers (in kb) is indicated on the left of the blot.

Previous studies by several laboratories have established that probes hybridize predominantly to linearized plasmids on these pulsed-field gel Southern blots, thus providing a relatively accurate estimation of plasmid size (8, 10, 12, 16, 19, 20, 26, 27, 31). Therefore, the Southern blot results shown in Fig. 1A also revealed the existence of significant size variations among the cpb plasmids of the surveyed type C isolates. Specifically, the results in Fig. 1A and Table 1 indicate that, for the 16 type C isolates giving discernible cpb probe hybridization, cpb plasmid size ranged from ∼65 kb to ∼110 kb.

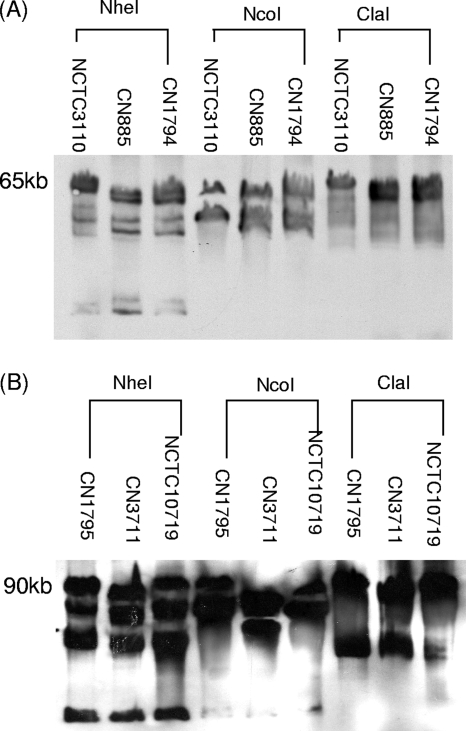

Comparison of the ∼65-kb and ∼90- to 95-kb cpb plasmids of type B isolates with those of type C isolates.

The results in Fig. 1A reveal that the cpb plasmids in some type C isolates are very similar in size to the ∼65-kb and ∼90-kb cpb plasmids found in many, if not all, type B isolates (31). To help assess whether these are the same plasmid or two different but comigrating plasmids, DNA from type B isolate NCTC3110 or type C isolates CN885 and CN1794, which each carry an ∼65-kb cpb plasmid, was digested with three different restriction enzymes (NheI, NcoI, and ClaI) and then subjected to pulsed-field Southern blot analyses with a cpb probe (Fig. 2 A). In this experiment, migration of cpb genes residing on the same plasmid in different isolates should consistently exhibit the same response (sensitivity or insensitivity) to digestion using each restriction endonuclease. However, if the plasmid-borne cpb gene from one isolate showed no change in migration after digestion with a particular restriction endonuclease but migration of the plasmid-borne cpb gene in another isolate was affected by digestion with the same enzyme, that result would indicate that the two cpb genes are present on similar-sized, but different, plasmids (8, 19, 31, 32). The results obtained (Fig. 2A) showed similar susceptibility patterns to restriction enzyme digestion for all three isolates carrying an ∼65-kb cpb plasmid, consistent with these isolates carrying similar cpb plasmids. Similar conclusions were obtained when this experiment was performed using DNA from type B isolate CN1795 and type C isolates CN3711 and NCTC10719, all of which carry cpb plasmids of ∼90 to 95 kb (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Comparison of the ∼65-kb (A) and ∼90- to 95-kb (B) cpb plasmids carried by certain type B and type C isolates using Southern hybridization analyses of pulsed-field gels run with restriction enzyme-digested DNA. The type C isolates analyzed include CN885 and CN1794 (A) and CN3711 and NCTC10719 (B). The type B isolates analyzed include NCTC3110 (A) and CN1795 (B). Both blots were hybridized with a cpb-specific probe. Migration of molecular size markers is indicated on the left.

Analysis of cpe gene location among the surveyed cpe-positive type C isolates.

Four of the 16 type C isolates that did not show extensive smearing on pulsed-field Southern blots had previously been identified as cpe positive; each of those four type C isolates had also previously been shown to carry their cpe gene on plasmids (20). Those conclusions were confirmed by stripping the Southern blots hybridized with a cpb probe and then rehybridizing those stripped blots with a cpe probe. This analysis showed that these four cpe-positive type C isolates carry their cpe gene on large (ranging from ∼75 kb to ∼110 kb) plasmids (Fig. 1B and Table 1).

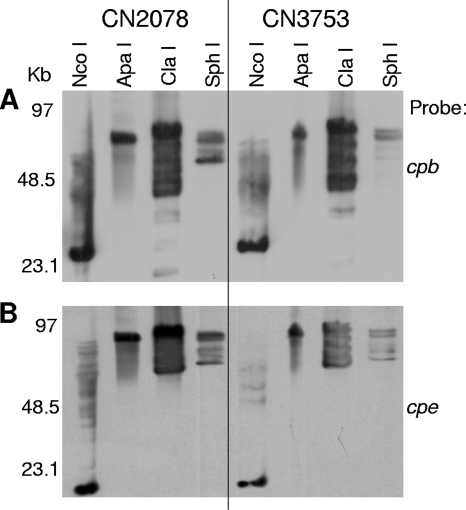

Evaluation of whether cpb and cpe are present on the same or different plasmids in type C isolates CN2078 and CN3753.

Beyond confirming previous reports that the cpe gene is plasmid borne in most, if not all, type C isolates, the major reason for performing the cpe Southern blot whose results are shown in Fig. 1B was to allow the first head-to-head comparison of the relative sizes of the cpb and cpe plasmids in these four cpe-positive type C isolates. By overlapping the blots from Fig. 1A and B, it became readily apparent that the cpb and cpe genes are present on two distinct plasmids in type C isolates CN5388 and CN3763. However, this analysis also showed that the cpb and cpe probes hybridize to the same Southern blot location using DNA from type C isolates CN2078 and CN3753. Those results in Fig. 1A and B could indicate that both the cpb and cpe genes are present on the same ∼75-kb or ∼85- to 90-kb plasmid, respectively, in type C isolates CN2078 and CN3753. Alternatively, those two isolates could carry two distinct comigrating plasmids of similar sizes.

To help discriminate between those two possibilities, the same approach described for Fig. 2 was employed. DNA from CN2078 and CN3753 was digested with several different restriction endonucleases and then subjected to pulsed-field Southern blot analyses. For CN2078 DNA, migration of cpb- and cpe-containing DNA exhibited similar susceptibility patterns in response to restriction enzyme digestion (Fig. 3). These results are consistent with CN2078 carrying its cpb gene on the same ∼75-kb plasmid that also carries the cpe gene. When this analysis was performed with CN3753 DNA (Fig. 3), the results obtained were also consistent with the cpb and cpe genes of that type C isolate being present together on the same ∼85-kb plasmid.

FIG. 3.

Southern hybridization analyses of pulsed-field gels run with restriction enzyme-digested DNA extracted from cpe-positive type C isolates CN2078 and CN3753. The blot was first hybridized with a cpb-specific probe (A) and then stripped and reprobed with a cpe-specific probe (B). Restriction enzymes used for digestion are shown at the top of the blot. Migration of molecular size markers is indicated on the left.

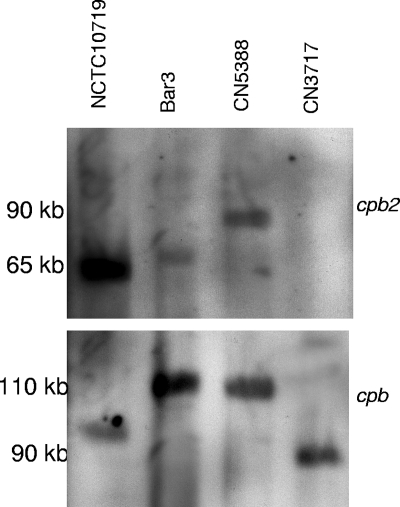

Mapping of the cpb2 gene location among cpb2-positive type C isolates.

Three of the 16 surveyed type C isolates not showing extensive smearing on pulsed-field Southern blots had been determined by a previous study to carry the cpb2 gene (11). Since it had not yet been determined whether the cpb2 gene in type C isolates is plasmid borne or chromosomal, those three cpb2-positive type C isolates were subjected to pulsed-field Southern blot analyses using a cpb2 probe (Fig. 4 and Table 1). Results from that experiment mapped the cpb2 gene to plasmids of ∼65 to 90 kb in these three type C isolates. Additionally, when that blot was stripped and then rehybridized with a cpb probe, the cpb2-carrying plasmid was clearly distinct from the cpb plasmid in each of the three cpb2-positive type C isolates.

FIG. 4.

Southern hybridization analyses of pulsed-field gels run with DNA extracted from cpb2-positive type C isolates NCTC10719, Bar3, and CN5388. cpb2-negative type C isolate CN3717 is included as a control. (Top) The blot was hybridized with a cpb2-specific probe. (Bottom) The blot was stripped and rehybridized with a cpb-specific probe. Migration of size markers is indicated on the left of the blot.

PCR evaluation of tpeL gene carriage among type C isolates.

While carriage of cpb, cpe, and cpb2 genes among the surveyed type C isolate collection has previously been evaluated by PCR assays (11), a new toxin encoded by the tpeL gene has been discovered since that earlier work (1). Therefore, a PCR assay was performed to assess the presence of the tpeL ORF among the 16 type C isolates characterized in Table 1. This analysis determined that DNA from 12 of these 16 type C isolates supported amplification of a tpeL PCR product (Table 1). Interestingly, none of those tpeL-positive type C isolates was also cpe positive.

Expression of TpeL by C. perfringens type C isolates.

The expression of alpha toxin, beta toxin, enterotoxin, and beta2 toxin by type C isolates has been evaluated in earlier studies (11), but TpeL expression by type C isolates has not yet been systematically assessed because TpeL was identified (1) only after completion of that earlier study. Since the current PCR assays detected tpeL ORF sequences in many surveyed type C isolates (Table 1), RT-PCR analyses were performed to evaluate whether the tpeL gene is expressed by five representative tpeL-positive type C isolates (NCTC10719, CN5383, CN1797, CN886, and Bar3). For all five surveyed tpeL-positive type C isolates, tpeL transcripts were detected after either 6 h or 24 h of growth in TGY broth (data not shown), opening the possibility that TpeL might contribute to the virulence of these isolates. No product was amplified when this RT-PCR analysis was performed with CN2078 (data not shown), consistent with this isolate's testing PCR negative for the presence of tpeL sequences.

Analysis of tpeL gene location in tpeL-positive type C isolates.

As shown in Fig. 1C and Table 1, pulsed-field Southern blot analyses demonstrated that, in all surveyed tpeL-positive type C isolates, the tpeL gene resides on plasmids of ∼65 kb to ∼95 kb in size. For two tpeL-positive isolates, i.e., CN5383 and Bar3, the tpeL probe clearly hybridized to a plasmid different from the cpb-carrying plasmid. However, in the other tpeL-positive type C isolates, the cpb and tpeL probes cohybridized to the same Southern blot location, corresponding to an ∼65-kb plasmid, an ∼90-kb plasmid, or an ∼95-kb plasmid.

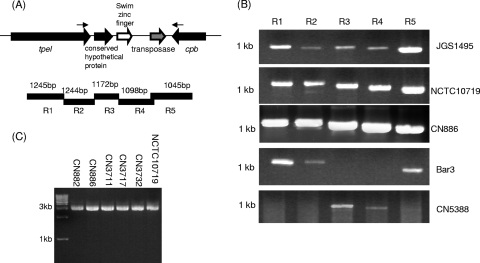

PCR linkage of the tpeL and cpb genes in some tpeL-positive type C isolates.

Bioinformatic analysis of the JCVI JGS1495 genome sequence indicated that the tpeL gene in this type C isolate is located ∼3 kb downstream of its cpb gene, similar to all characterized type B cpb plasmids (28). Based upon that observation, an overlapping PCR assay using a five-pair set of primers (encoding PCR products R1 to R5) (Fig. 5 A) (31) was designed to assess whether similar genetic linkages might exist between the cpb and tpeL genes in other tpeL-positive type C isolates. The results obtained from this overlapping PCR assay were consistent with the cpb gene being linked to the tpeL gene in NCTC10719, JGS1495, and CN886 (Fig. 5B). However, these analyses did not support the cpb gene being proximal to tpeL in Bar3 or CN5383, consistent with the PFGE Southern blot results (Table 1) showing that cpb and tpeL are located on different plasmids in those two type C isolates.

FIG. 5.

Linkage of the tpeL and cpb genes in some type C isolates by long-range PCR and overlapping PCR approaches. (A) Arrangement of the cpb and tpeL gene loci in C. perfringens type C isolate JGS1495 (based upon sequencing results released from JCVI). Solid bars underneath the locus diagram depict the 5 overlapping PCRs used in the experiment for panel B. Small arrows indicate primers used in the long-range PCR studies whose results are shown in panel C. (B) Overlapping PCR analysis of the region extending from cpb to tpeL in type C isolates NCTC10719, JGS1495, CN886, Bar3, and CN5388 using reaction primers R1 to R5 (31). (C) Long-range PCR analyses to study the linkage of the tpeL and cpb genes in 6 type C isolates.

Those overlapping PCR results were confirmed by a long-range PCR using one primer to internal tpeL ORF sequences and a second primer to internal cpb ORF sequences (Fig. 5A). This PCR amplified (Fig. 5C) a product of the expected ∼3-kb size from six different type C isolates that had cohybridized cpb and tpeL probes to the same Southern blot location in Fig. 1C. Furthermore, sequencing confirmed that this long-range PCR product matched the JCVI sequence for the JGS1495 region extending from tpeL to cpb and that this region is 99% homologous with the tpeL-to-cpb region in type B isolates. However, the same long-range PCR failed to amplify any product using DNA from Bar3 or CN5383 (Fig. 5C and data not shown), consistent with the PFGE Southern blot results (Table 1) showing that cpb and tpeL are located on different plasmids in those two type C isolates.

Carriage of the rep gene among plasmids of type C isolates.

Previous studies (2) have shown that the Rep protein is important for replication of C. perfringens tetracycline resistance plasmid pCW3. In addition, several other reports (19, 26, 31, 32) detected the presence of the Rep-encoding gene (rep) on toxin plasmids in type A, B, D, and E isolates. Therefore, a Southern blot analysis of pulsed-field gels was performed to assess whether the plasmids in type C isolates might also carry rep sequences. This experiment revealed that, for all surveyed type C isolates, the rep probe consistently hybridized to the same blot location as the cpb probe, suggesting that rep is commonly present on the cpb plasmid in type C isolates (Fig. 1D and Table 1). For cpe-positive type C isolates, there was also consistent cohybridization of the rep and cpe probes, suggesting that the cpe plasmids of type C isolates also carry rep sequences. The rep and cpb2 probes cohybridized to the same pulsed-field Southern blot location using DNA from 2 of 3 cpb2-positive type C isolates (Table 1).

Plasmid carriage of the tcp locus in type C isolates.

The tcp locus has been shown to mediate conjugative transfer of C. perfringens plasmid pCW3 and is also likely responsible for the demonstrated conjugative transfer of the cpe plasmids of type A isolates and the etx plasmids of type D isolates (2, 5, 14). Therefore, the current study surveyed whether tcp genes might be associated with plasmids in type C isolates. In this survey, a pulsed-field gel Southern blot was hybridized with probes specific for either of two tcp genes (tcpF or tcpH) required for pCW3 conjugative plasmid transfer (2). Results from this experiment showed that all surveyed type C isolates hybridized both tcp probes, with most type C isolates cohybridizing the tcpF and tcpH probes at multiple blot locations (Table 1 and data not shown), suggesting that type C isolates carry multiple plasmids with conjugative potential. Of particular note, tcp probes consistently cohybridized to the same blot location containing the cpb plasmid and, when present, the cpe plasmid for all surveyed type C isolates, suggesting the conjugative potential of these toxin plasmids.

Southern blot and PCR analyses to evaluate an association between IS1151- and cpb-carrying plasmids in type C isolates.

Previous studies have shown that IS1151 insertion sequences are closely associated with several toxin genes in C. perfringens, including the etx genes in type B and D isolates (27, 31, 32). Therefore, Southern blot analyses of pulsed-field gels using an IS1151 probe were performed with type C isolates. Those studies showed hybridization of the IS1151 probe to the same blot location containing the cpb plasmid in all surveyed type C isolates (Fig. 1E and Table 1). In addition, isolates CN3753, CN3763, and CN5388 possessed a second IS1151-carrying plasmid. For isolates CN3763 and CN5388, this second IS1151-carrying plasmid comigrated with the cpe plasmid, consistent with recent identification of IS1151 sequences located near the cpe gene of most cpe-positive type C isolates (20).

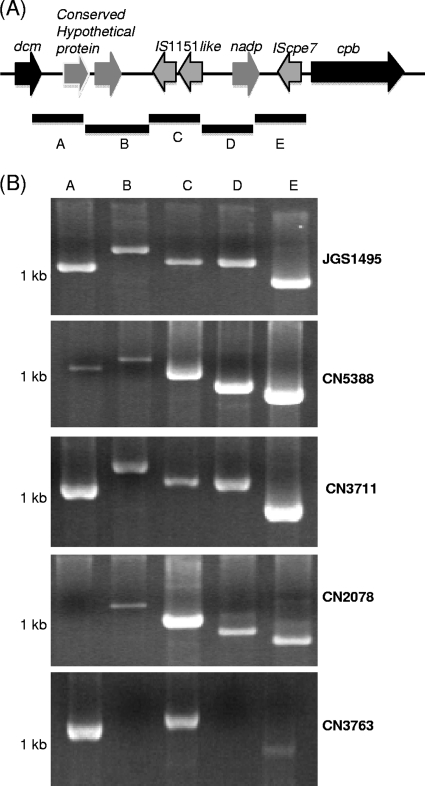

PCR linkage of the cpb gene with IS1151 or the dcm gene in type C isolates.

Analysis of the JCVI-released JGS1495 genome sequence identified dcm and two IS1151-like sequences present near the cpb gene (Fig. 6 A). Therefore, overlapping PCR studies, using a five-pair set of primers (encoding PCR products F1 to F5) (Table 2 and Fig. 6A) designed from JGS1495 cpb locus sequences, were performed to evaluate whether dcm and IS1151-like sequences might also be located near the cpb gene in other C. perfringens type C isolates. Results from this overlapping PCR assay supported the proximity of IS1151-like sequences near the cpb gene in at least 4 of the 5 (JGS1495, CN5388, CN3711, and CN2078) surveyed type C isolates (Fig. 6B). Among those 4 isolates, their IS1151-cpb locus was clearly adjacent to dcm sequences. For another surveyed type C isolate, IS1151-like sequences appeared to be present near a dcm gene, although overlapping PCR was unable to link IS1151 with the cpb gene in that isolate.

FIG. 6.

Overlapping PCR linkage of the cpb gene with IS1151 and the dcm gene in some type C isolates. (A) Arrangement of the cpb locus in C. perfringens type C isolate JGS1495 (based upon sequencing results released from JCVI). Boxes A to E in panel A depict the overlapping PCRs used to link dcm and cpb in panel B. (B) Overlapping PCR analyses of the JGS1495 region extending from the dcm to cpb gene using DNA from type C isolates JGS1495, CN5388, CN3711, CN2078, and CN3763 and reaction primers A to E (Table 2). Migration of 1-kb size markers is shown at the left of the gel.

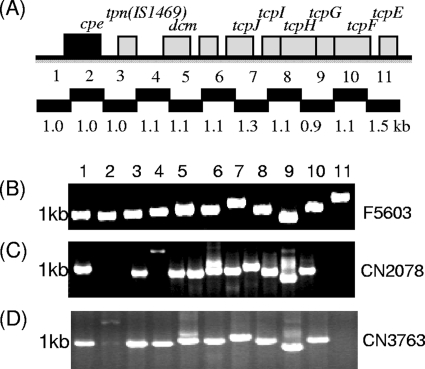

PCR studies to evaluate whether the variable and conserved regions of pCPF5603 or pCPF4969 are present in type C isolates.

As mentioned in the introduction, two major families of cpe plasmids have been identified in type A isolates, as represented by prototype plasmids pCPF5603 and pCPF4969 (26). Complete sequencing of pCPF5603 and pCPF4969 showed that both cpe plasmid families carry tcp genes (26). Since we detected the presence of tcp genes in the surveyed type C isolates (Table 1), overlapping PCR analyses were performed to evaluate whether type C isolates might carry plasmids related to pCPF5603 or pCPF4969. However, primers to adjacent ORFs in the variable regions of pCPF5603 or pCPF4969 failed to amplify products from any type C isolates (not shown). In contrast, PCR products of the expected size were amplified for the entire tcp locus, using DNA from type C isolates CN2078 and CN3763 and primers specific for adjacent ORFs present in the conserved region of pCPF5603 and pCPF4969 (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Overlapping PCR analysis to evaluate the presence of the pCPF5603 conserved region in type C isolates. (A) Diagram depicting the organization of the pCPF5603 conserved region (26) and showing the overlapping PCRs included in this previously developed assay (26). (B) Overlapping PCR analysis of the conserved region, using DNA from type A isolate F5603 (the host for pCPF5603) as a control. Similar overlapping PCR analyses of type C isolates CN2078 (C) and CN3763 (D) are shown. Migration of 1-kb molecular size markers is indicated on the left.

DISCUSSION

Among all C. perfringens isolates, only type B and C isolates carry the cpb gene. A recent study established that the cpb gene in type B isolates is plasmid borne (31). Furthermore, that study detected only limited diversity of cpb plasmids among 17 type B isolates, i.e., each of those surveyed type B isolates was found to carry a cpb plasmid of either ∼65 kb or ∼90 kb. Those cpb plasmids of type B isolates consistently possessed tcp genes, suggesting their conjugative potential, as well as a rep gene and IS1151 sequences. In addition, those ∼65-kb and ∼90-kb cpb plasmids of type B isolates were all found to carry a tpeL gene ∼3 kb upstream from their cpb gene.

The current study has now determined that the cpb gene is also plasmid borne in most, if not all, type C isolates. Since expression of the cpb gene was previously shown to be necessary for the pathogenicity of type C isolates (33), this mapping of the cpb gene to plasmids indicates that plasmids are important for the virulence of type C isolates. Furthermore, this study identified some similarities between the cpb plasmids of type B and C isolates. For example, the cpb plasmids in all surveyed type C isolates also appear to carry tcp, rep, and IS1151, as reported for type B cpb plasmids. In addition, no cpb plasmids of type B isolates, or cpb plasmids of type C isolates, that carry the cpb2 gene have yet been identified. While the cpb2 gene is present in most, if not all, type B isolates (27), it is located on their etx plasmid rather than on their cpb plasmid.

However, the current study also determined that the cpb plasmids of the surveyed type C isolates are considerably more diverse than the cpb plasmids characterized to date among type B isolates (31). For example, the cpb plasmids in the 17 studied type C isolates exhibited greater size diversity than the ∼65-kb or ∼90-kb cpb plasmids present in characterized type B cpb plasmids; i.e., the current results suggest that some type C isolates apparently carry the same ∼65-kb and ∼90- to 95-kb cpb plasmids found in all surveyed type B isolates, but other type C isolates possess cpb plasmids of ∼75 kb, ∼85 kb, or ∼110 kb. Furthermore, more variation in carriage of other toxin genes apparently exists among type C cpb plasmids than among type B cpb plasmids. For example, only the ∼65- and ∼90- to 95-kb cpb plasmids of type C isolates carry the tpeL gene found on all type B cpb plasmids characterized to date. Similarly, while no cpe-positive type B isolates have yet been identified, the ∼75- and ∼85-kb cpb plasmids present in some type C isolates apparently also carry the cpe gene.

The current discovery of more cpb plasmid diversity among the surveyed type C isolates than among type B isolates (31) is reminiscent of the greater etx plasmid diversity observed among type D isolates than among type B isolates. Specifically, while all 17 surveyed type B isolates were found to carry the same ∼65-kb etx plasmid (27, 31), a similar survey of type D isolates revealed a diversity of etx plasmids (32). For example, only a few type D isolates were identified that carry the etx plasmid present in most, if not all, type B isolates (27). Since the current results revealed that only some type C isolates carry the same cpb plasmids present among type B isolates, these findings about cpb and etx plasmid carriage may collectively indicate that only certain toxin plasmid combinations can be stably maintained within a single C. perfringens cell. An inability to stably maintain and inherit different plasmids within a single C. perfringens cell would indicate that these plasmids are incompatible, possibly due to either replication or partitioning interference (4).

Since the current study localized both cpe and tpeL to plasmids among the surveyed type C isolates, plasmid incompatibility issues could similarly help to explain why none of these type C isolates carry both cpe and tpeL genes. Specifically, the cpe gene was detected in type C isolates carrying tpeL-negative, cpb-positive plasmids of ∼75 kb, 85 kb, or 110 kb but not in those type C isolates carrying the tpeL-positive, cpb-positive plasmids of ∼65 kb or ∼90 to 95 kb. Since the current study found that those same ∼65-kb or ∼90- to 95-kb cpb plasmids also appear to be present in most, if not all, type B isolates, incompatibility between the ∼65-kb or ∼90- to 95-kb cpb plasmids and some or all cpe plasmids could possibly explain why cpe-positive type B isolates have not yet been identified.

Extrapolating further, incompatibility issues possibly offer an explanation for why other toxin plasmid combinations have never been observed in a single C. perfringens cell. For example, no C. perfringens isolate that carries both an iota toxin-encoding plasmid and a cpb plasmid has yet been found. However, it is clear that some toxin plasmid combinations can be stably maintained since type B isolates carry their cpb and etx genes on separate plasmids (31). Similarly, the current study found that some type C isolates carry cpb and tpeL on separate plasmids. These observations suggest that C. perfringens toxin plasmid incompatibility issues represent a research topic worthy of future study. Similar plasmid incompatibility issues may also affect the virulence of other pathogenic clostridia. For example, although plasmids exist that encode only botulinum neurotoxin serotype A or B (13, 23), all surveyed Clostridium botulinum stains producing both neurotoxin serotypes B and A carry these two neurotoxin genes on the same plasmid (13, 22). This observation might open the possibility that plasmids encoding only serotype B or serotype A cannot be stably maintained together in the same C. botulinum cell.

Combining the current and previous results may also permit speculation regarding the origin of type B isolates. Both type C and type D isolates are present in soil (21), where they might occasionally come in physical contact. As mentioned above, the current study found that nearly all cpb plasmids of type C isolates carry tcp sequences, which are known to mediate conjugative transfer of other C. perfringens plasmids (2). Similar tcp sequences are also present on nearly all etx plasmids found in type D isolates (32). Therefore, close contact in soil (or possibly other locations) could allow conjugative toxin plasmid exchange between a type C isolate and a type D isolate. This transfer of a cpb or etx plasmid between type C and D isolates may often be rapidly followed by loss of one of these two toxin plasmids due to plasmid incompatibility issues, as discussed above. However, stable maintenance of both etx and cpb plasmids in a single C. perfringens isolate, creating a type B isolate, may occur when this transfer involves introduction of the ∼65-kb or ∼90- to 95-kb tpeL-positive cpb plasmid carried by many type C isolates into a type D isolate carrying an ∼65-kb etx plasmid, or vice versa. This hypothesis, which must be experimentally tested, offers an explanation for why type B isolates are the least common of all C. perfringens isolates, i.e., they would stably arise only from matings between specific subpopulations of type C and type D isolates.

Besides shedding light on the possible evolution and diversity of C. perfringens toxin plasmids, the current results suggest a few additional insights. First, the current study found that the cpb gene of many type C isolates is located near several putative transposase ORFs (including two IS1151-like sequences) and the dcm gene. This finding supports previous suggestions that the dcm region of toxin plasmids may represent a hot spot for insertion of toxin gene-carrying mobile genetic elements, particularly those associated with IS1151 sequences. Previous observations have established the presence of IS1151 sequences and several other plasmid-borne toxin genes of C. perfringens, including iota toxin-encoding genes, cpe genes, and etx genes, near dcm genes (19, 26, 27, 32). Second, it has become clear that many C. perfringens toxin plasmids are related. For example, the pCPF5603 cpe plasmid family, the pCPF4969 cpe plasmid family, the ∼65-kb etx plasmid family, and many plasmids encoding NetB toxin (18) show extensive homology (26, 27). However, our overlapping PCR results suggest that the cpb plasmid found in type C isolates may substantially differ from those other toxin plasmids.

Finally, the current results offer another intriguing observation of potential virulence significance. Specifically, no associations were readily apparent between the origin of the surveyed type C isolates and their plasmid size variations, with one possible exception. All three human enteritis necroticans (pigbel) isolates surveyed in this study were found to carry a 110-kb, tpeL-negative cpb plasmid. Furthermore, these pigbel isolates were the only surveyed type C isolates found to carry this cpb plasmid. Therefore, although pigbel isolates are difficult to obtain, future studies should further examine whether a specific relationship exists between the 110-kb cpb plasmid and pigbel disease. If so, this cpb plasmid might encode other accessory virulence factors that contribute to this important human enteric disease. Sequencing of this 110-kb cpb plasmid, along with other cpb plasmids, may provide further insight into potential plasmid-borne virulence genes and should be pursued in the future.

Acknowledgments

This research was generously supported by grant AI056177-07 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Editor: B. A. McCormick

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 7 September 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Animoto, K., T. Noro, E. Oishi, and M. Shimizu. 2007. A novel toxin homologous to large clostridial cytotoxins found in culture supernatant of Clostridium perfringens type C. Microbiology 153:1198-1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bannam, T. L., W. L. Teng, D. Bulach, D. Lyras, and J. I. Rood. 2006. Functional identification of conjugation and replication regions of the tetracycline resistance plasmid pCW3 from Clostridium perfringens. J. Bacteriol. 188:4942-4951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Billington, S. J., E. U. Wieckowski, M. R. Sarker, D. Bueschel, J. G. Songer, and B. A. McClane. 1998. Clostridium perfringens type E animal enteritis isolates with highly conserved, silent enterotoxin sequences. Infect. Immun. 66:4531-4536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 4.Bouet, J.-Y., K. Nordstrom, and D. Lane. 2007. Plasmid partition and incompatibility—the focus shifts. Mol. Microbiol. 65:1405-1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brynestad, S., M. R. Sarker, B. A. McClane, P. E. Granum, and J. I. Rood. 2001. The enterotoxin (CPE) plasmid from Clostridium perfringens is conjugative. Infect. Immun. 69:3483-3487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collie, R. E., J. F. Kokai-Kun, and B. A. McClane. 1998. Phenotypic characterization of enterotoxigenic Clostridium perfringens isolates from non-foodborne human gastrointestinal diseases. Anaerobe 4:69-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collie, R. E., and B. A. McClane. 1998. Evidence that the enterotoxin gene can be episomal in Clostridium perfringens isolates associated with non-food-borne human gastrointestinal diseases. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:30-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cornillot, E., B. Saint-Joanis, G. Daube, S. Katayama, P. E. Granum, B. Carnard, and S. T. Cole. 1995. The enterotoxin gene (cpe) of Clostridium perfringens can be chromosomal or plasmid-borne. Mol. Microbiol. 15:639-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duncan, C. L., E. A. Rokos, C. M. Christenson, and J. I. Rood. 1978. Multiple plasmids in different toxigenic types of Clostridium perfringens: possible control of beta toxin production, p. 246-248. In D. Schlessinger (ed.), Microbiology—1978. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 10.Dupuy, B., G. Daube, M. R. Popoff, and S. T. Cole. 1997. Clostridium perfringens urease genes are plasmid-borne. Infect. Immun. 65:2313-2320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher, D. J., M. E. Fernandez-Miyakawa, S. Sayeed, R. Poon, V. Adams, J. I. Rood, F. A. Uzal, and B. A. McClane. 2006. Dissecting the contributions of Clostridium perfringens type C toxins to lethality in the mouse intravenous injection model. Infect. Immun. 74:5200-5210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fisher, D. J., K. Miyamoto, B. Harrison, S. Akimoto, M. R. Sarker, and B. A. McClane. 2005. Association of beta2 toxin production with Clostridium perfringens type A human gastrointestinal disease isolates carrying a plasmid enterotoxin gene. Mol. Microbiol. 56:747-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franciosa, G., A. Maugliani, C. Scalfaro, and P. Aureli. 2009. Evidence that plasmid-borne botulinum neurotoxin type B genes are widespread among Clostridium botulinum serotype B strains. PLoS One 4:e4829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hughes, M. L., R. Poon, V. Adams, S. Sayeed, J. Saputo, F. A. Uzal, B. A. McClane, and J. I. Rood. 2007. Epsilon-toxin plasmids of Clostridium perfringens type D are conjugative. J. Bacteriol. 189:7531-7538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson, S., and D. N. Gerding. 1997. Enterotoxemic infections, p. 117-140. In J. I. Rood, B. A. McClane, J. G. Songer, and R. W. Titball (ed.), The clostridia: molecular biology and pathogenesis. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom.

- 16.Katayama, S. I., B. Dupuy, G. Daube, B. China, and S. T. Cole. 1996. Genome mapping of Clostridium perfringens strains with I-Ceu I shows many virulence genes to be plasmid-borne. Mol. Gen. Genet. 251:720-726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawrence, G. W. 1997. The pathogenesis of enteritis necroticans, p. 198-207. In J. I. Rood, B. A. McClane, J. G. Songer, and R. W. Titball (ed.), The clostridia: molecular genetics and pathogenesis. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom.

- 18.Lepp, D., B. Roxas, V. Parreira, P. Marri, E. Rosey, J. Gong, J. Songer, G. Vedantam, and J. Prescott. 2010. Identification of novel pathogenicity loci in Clostridium perfringens strains that cause avian necrotic enteritis. PLoS One 5:e10795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li, J., K. Miyamoto, and B. A. McClane. 2007. Comparison of virulence plasmids among Clostridium perfringens type E isolates. Infect. Immun. 75:1811-1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li, J., K. Miyamoto, S. Sayeed, and B. A. McClane. 2010. Organization of the cpe locus in CPE-positive Clostridium perfringens type C and D isolates. PLoS One 5:e10932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li, J., S. Sayeed, and B. A. McClane. 2007. Prevalence of enterotoxigenic Clostridium perfringens isolates in Pittsburgh (Pennsylvania) area soils and home kitchens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:7218-7224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marshall, K. M., M. Bradshaw, and E. A. Johnson. 2010. Conjugative botulinum neurotoxin-encoding plasmids in Clostridium botulinum. PLoS One 5:e11087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marshall, K. M., M. Bradshaw, S. Pellett, and E. A. Johnson. 2007. Plasmid encoded neurotoxin genes in Clostridium botulinum serotype A subtypes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 361:49-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McClane, B. A. 2007. Clostridium perfringens, p. 423-444. In M. P. Doyle and L. R. Beuchat (ed.), Food microbiology, 3rd ed. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 25.McClane, B. A., F. A. Uzal, M. F. Miyakawa, D. Lyerly, and T. Wilkins. 2006. The enterotoxic clostridia, p. 688-752. In M. Dworkin, S. Falkow, E. Rosenburg, H. Schleifer, and E. Stackebrandt (ed.), The prokaryotes, 3rd ed. Springer, New York, NY.

- 26.Miyamoto, K., D. J. Fisher, J. Li, S. Sayeed, S. Akimoto, and B. A. McClane. 2006. Complete sequencing and diversity analysis of the enterotoxin-encoding plasmids in Clostridium perfringens type A non-food-borne human gastrointestinal disease isolates. J. Bacteriol. 188:1585-1598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyamoto, K., J. Li, S. Sayeed, S. Akimoto, and B. A. McClane. 2008. Sequencing and diversity analyses reveal extensive similarities between some epsilon-toxin-encoding plasmids and the pCPF5603 Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin plasmid. J. Bacteriol. 190:7178-7188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagahama, M., S. Hayashi, S. Morimitsu, and J. Sakurai. 2003. Biological activities and pore formation of Clostridium perfringens beta toxin in HL 60 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278:36934-36941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petit, L., M. Gilbert, and M. R. Popoff. 1999. Clostridium perfringens: toxinotype and genotype. Trends Microbiol. 7:104-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rokos, E. A., J. I. Rood, and C. L. Duncan. 1978. Multiple plasmids in different toxigenic types of Clostridium perfringens. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 4:323-326. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sayeed, S., J. Li, and B. A. McClane. 2010. Characterization of virulence plasmid diversity among Clostridium perfringens type B isolates. Infect. Immun. 78:495-504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sayeed, S., J. Li, and B. A. McClane. 2007. Virulence plasmid diversity in Clostridium perfringens type D isolates. Infect. Immun. 75:2391-2398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sayeed, S., F. A. Uzal, D. J. Fisher, J. Saputo, J. E. Vidal, Y. Chen, P. Gupta, J. I. Rood, and B. A. McClane. 2008. Beta toxin is essential for the intestinal virulence of Clostridium perfringens type C disease isolate CN3685 in a rabbit ileal loop model. Mol. Microbiol. 67:15-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shimizu, T., K. Ohtani, H. Hirakawa, K. Ohshima, A. Yamashita, T. Shiba, N. Ogasawara, M. Hattori, S. Kuhara, and H. Hayashi. 2002. Complete genome sequence of Clostridium perfringens, an anaerobic flesh-eater. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:996-1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steinthorsdottir, V., H. Halldorsson, and O. S. Andresson. 2000. Clostridium perfringens beta-toxin forms multimeric transmembrane pores in human endothelial cells. Microb. Pathog. 28:45-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Titball, R. W., C. E. Naylor, and A. K. Basak. 1999. The Clostridium perfringens alpha-toxin. Anaerobe 5:51-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uzal, F. A., J. Saputo, S. Sayeed, J. E. Vidal, D. J. Fisher, R. Poon, V. Adams, M. E. Fernandez-Miyakawa, J. I. Rood, and B. A. McClane. 2009. Development and application of new mouse models to study the pathogenesis of Clostridium perfringens type C enterotoxemias. Infect. Immun. 77:5291-5299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vidal, J. E., K. Ohtani, T. Shimizu, and B. A. McClane. 2009. Contact with enterocyte-like Caco2 cells induces rapid upregulation of toxin production by Clostridium perfringens type C isolates. Cell. Microbiol. 11:1306-1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]