Abstract

Genome replication is inefficient without processivity factors, which tether DNA polymerases to their templates. The vaccinia virus DNA polymerase E9 requires two viral proteins, A20 and D4, for processive DNA synthesis, yet the mechanism of how this tricomplex functions is unknown. This study confirms that these three proteins are necessary and sufficient for processivity, and it focuses on the role of D4, which also functions as a uracil DNA glycosylase (UDG) repair enzyme. A series of D4 mutants was generated to discover which sites are important for processivity. Three point mutants (K126V, K160V, and R187V) which did not function in processive DNA synthesis, though they retained UDG catalytic activity, were identified. The mutants were able to compete with wild-type D4 in processivity assays and retained binding to both A20 and DNA. The crystal structure of R187V was resolved and revealed that the local charge distribution around the substituted residue is altered. However, the mutant protein was shown to have no major structural distortions. This suggests that the positive charges of residues 126, 160, and 187 are required for D4 to function in processive DNA synthesis. Consistent with this is the ability of the conserved mutant K126R to function in processivity. These mutants may help unlock the mechanism by which D4 contributes to processive DNA synthesis.

Poxviruses are large, double-stranded DNA viruses that replicate exclusively in the cell cytoplasm in granular structures known as virosomes (31). Separated from the host nucleus, they rely on their own encoded gene products for DNA synthesis and replication (43). To efficiently synthesize its ∼200,000-base genome, the poxvirus DNA polymerase must be tethered to the DNA template by its processivity factor. DNA processivity factors are proteins that stabilize polymerases onto their templates for effective genome replication (1, 22). Processivity factors are synthesized by nearly all replicating systems, ranging from bacteriophages to eukaryotes, yet each one is specific to its cognate polymerase. In the presence of these factors, polymerases are able to incorporate a great number of nucleotides per template binding event; in their absence, polymerases detach from their templates too frequently to successfully replicate the genome (14, 20). E9, the DNA polymerase of the prototypical poxvirus, vaccinia virus, synthesizes approximately 10 nucleotides before dissociating from the viral DNA template (28). However, it can incorporate thousands of nucleotides when it is associated with its processivity factor (29). This extended strand synthesis, known as processivity, is necessary for vaccinia virus to effectively replicate its 192-kb genome.

The protein A20 was first reported to be a component of the vaccinia virus processive DNA polymerase (19, 37), yet we were unable to establish processivity in vitro using only A20 and E9. To identify which other proteins were required for processivity, we assessed six in vitro-synthesized proteins known to be involved in vaccinia virus replication (E9, A20, B1, D4, D5, and H5). We found that the protein D4, a uracil DNA glycosylase (UDG), was required in addition to A20 and E9 and that these three proteins are both necessary and sufficient for vaccinia virus processivity. Indeed, A20 and D4 have been shown to interact with each other (15, 26), and our finding supports a report identifying A20 and D4 as forming a heterodimeric processivity factor for E9 (41). Here, we use mutational analysis to examine the role of D4 in processive DNA synthesis. We report the finding of three D4 mutants which are unable to function in processivity yet retain their UDG enzymatic activity and their ability to bind both A20 and DNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning replication genes from vaccinia virus.

The A20R, B1R, D4R, D5R, E9L, and H5R genes were individually cloned by PCR from the WR strain of the vaccinia virus DNA genome by using the following primer pairs (Integrated DNA Technologies): A20R forward (5′-CACCATGACTTCTAGCGCTGATTTAAC-3′) and A20R reverse (5′-TCACTCGAATAATCTTTTTTTGAC-3′), B1R forward (5′-CACCATGAACTTTCAAGGACTTGTGTTAACTG-3′) and B1R reverse (5′-TTAATAATATACACCCTGCATTAATATGTG-3′), D4R forward (5′-CACCATGAATTCAGTGACTGTATCACACGCGCC-3′) and D4R reverse (5′-TTAATAAATAAACCCTTGAGCCC-3′), D5R forward (5′-CACCATGGATGCGGCTATTAGAGGTAATG-3′) and D5R reverse (5′-TTACGGAGATGAAATATCCTCTATG-3′), E9L forward (5′-CACCATGGACGTTCGATGCATTAATTGG-3′) and E9L reverse (5′-TTATGCTTCGTAAAATGTAGG-3′), and H5R forward (5′-CACCATGGCGTGGTCAATTACAAATAAAGCGG-3′) and H5R reverse (5′-TTACTTCTTACAAGTTTTAACTTTTTTACG-3′).

The products derived from these reactions were gel purified (Qiagen) and then cloned into pcDNA3.2/V5-DEST Gateway expression vectors (Invitrogen). All resulting plasmids were sequenced to ensure correct insertion.

In vitro transcription/translation.

[35S]Methionine-cysteine-labeled and nonlabeled vaccinia virus proteins were expressed in vitro using a TNT T7 coupled reticulocyte lysate system (Promega) from pcDNA3.2/V5-DEST expression vectors. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 1.5 h. The labeled proteins were fractionated on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-10% Bis-Tris polyacrylamide gel using MES buffer (Invitrogen), and the translation products were visualized by PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

D4 point mutants were generated utilizing a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and then expressed in vitro as described above. The primer pairs used are listed in Table 1 (Integrated DNA Technologies).

TABLE 1.

Primers for construction of mutants

| Mutant | Primera |

|---|---|

| D68N | F, 5′- GAGTATGTGTGTGCGGTATAAATCCGTATCCGAAAGATGG-3′ |

| R, 5′- CCATCTTTCGGATACGGATTTATACCGCACACACATACTC-3′ | |

| P71H | F, 5′- GGTATAGATCCGTATCACAAAGATGGAACTGGTG-3′ |

| R, 5′- CACCAGTTCCATCTTTGTGATACGGATCTATACC-3′ | |

| T85A | F, 5′- CCGTTCGAATCACCAAATTTTGCAAAAAAATCAATTAAGGAG-3′ |

| R, 5′- CTCCTTAATTGATTTTTTTGCAAAATTTGGTGATTCGAACGG-3′ | |

| S88A | F, 5′- CACCAAATTTTACAAAAAAAGCAATTAAGGAGATAGCTTC-3′ |

| R, 5′- GAAGCTATCTCCTTAATTGCTTTTTTTGTAAAATTTGGTG-3′ | |

| E91V | F, 5′- CCAAATTTTACAAAAAAATCAATTAAGGTGATAGCTTCATCTATATCTAG-3′ |

| R, 5′- CTAGATATAGATGAAGCTATCACCTTAATTGATTTTTTTGTAAAATTTGG-3′ | |

| SSIS94-97AAIA | F, 5′- CAATTAAGGAGATAGCTGCAGCTATAGCTAGATTAACCGGAGTAATTG-3′ |

| R, 5′- CAATTACTCCGGTTAATCTAGCTATAGCTGCAGCTATCTCCTTAATTG-3′ | |

| K126R | F, 5′- CCCTGGAATTATTACTTAAGTTGTAGATTAGGAGAAACAAAAAGTCACG-3′ |

| R, 5′- CGTGACTTTTTGTTTCTCCTAATCTACAACTTAAGTAATAATTCCAGGG-3′ | |

| K126V | F, 5′- CCCTGGAATTATTACTTAAGTTGTGTATTAGGAGAAACAAAAAGTCACG-3′ |

| R, 5′- CGTGACTTTTTGTTTCTCCTAATACACAACTTAAGTAATAATTCCAGGG-3′ | |

| L127A | F, 5′- GGAATTATTACTTAAGTTGTAAAGCAGGAGAAACAAAAAGTCACG-3′ |

| R, 5′- CGTGACTTTTTGTTTCTCCTGCTTTACAACTTAAGTAATAATTCC-3′ | |

| T130A | F, 5′- CTTAAGTTGTAAATTAGGAGAAGCAAAAAGTCACGCGATC-3′ |

| R, 5′- GATCGCGTGACTTTTTGCTTCTCCTAATTTACAACTTAAG-3′ | |

| K131V | F, 5′- GTTGTAAATTAGGAGAAACAGTAAGTCACGCGATCTAC-3′ |

| R, 5′- GTAGATCGCGTGACTTACTGTTTCTCCTAATTTACAAC-3′ | |

| S132A | F, 5′- GTTGTAAATTAGGAGAAACAAAAGCTCACGCGATCTACTGG-3′ |

| R, 5′- CCAGTAGATCGCGTGAGCTTTTGTTTCTCCTAATTTACAAC-3′ | |

| L158A | F, 5′- CACGTTAGTGTTCTTTATTGTGCGGGTAAAACAGATTTCTCG-3′ |

| R, 5′- CGAGAAATCTGTTTTACCCGCACAATAAAGAACACTAACGTG-3′ | |

| K160V | F, 5′- GTGTTCTTTATTGTTTGGGTGTAACAGATTTCTCGAATATACG-3′ |

| R, 5′- CGTATATTCGAGAAATCTGTTACACCCAAACAATAAAGAACAC-3′ | |

| T161A | F, 5′- GTGTTCTTTATTGTTTGGGTAAAGCAGATTTCTCGAATATACG-3′ |

| R, 5′- CGTATATTCGAGAAATCTGCTTTACCCAAACAATAAAGAACAC-3′ | |

| S164A | F, 5′- GTTTGGGTAAAACAGATTTCGCGAATATACGGGCCAAG-3′ |

| R, 5′- CTTGGCCCGTATATTCGCGAAATCTGTTTTACCCAAAC-3′ | |

| S172A | F, 5′- CGGGCCAAGTTAGAAGCCCCGGTAACTACC-3′ |

| R, 5′- GGTAGTTACCGGGGCTTCTAACTTGGCCCG-3′ | |

| T175A | F, 5′- GTTAGAATCCCCGGTAGCTACCATAGTCGGAT-3′ |

| R, 5′- ATCCGACTATGGTAGCTACCGGGGATTCTAAC-3′ | |

| T176A | F, 5′- AGAATCCCCGGTAACTGCCATAGTCGGATATC-3′ |

| R, 5′- GATATCCGACTATGGCAGTTACCGGGGATTCT-3′ | |

| R187V | F, 5′- CCAGCGGCTAGAGACGTCCAATTCGAGAAAG-3′ |

| R, 5′- CTTTCTCGAATTGGACGTCTCTAGCCGCTGG-3′ | |

| S194A | F, 5′- CGAGAAAGATAGAGCATTTGAAATTATCAACG-3′ |

| R, 5′- CGTTGATAATTTCAAATGCTCTATCTTTCTCG-3′ |

F, forward; R, reverse.

DNA synthesis assay.

The plate assay described previously (23, 40) was used to determine which proteins were required for DNA synthesis. A biotinylated template with uniformly distributed adenines (5′-biotin-GCACTTATTGCATTCGCTAGTCCACCTTGGATCTCAGGCTATTCGTAGCGAGCTACGCGTACGTTAGCTTCGGTCATCCCGTCAGCGGTCATTCATTGGC-3′) was annealed to a 20-mer primer (5′-GCCAATGAATGACCGCTGAC-3′) and then bound to streptavidin-coated wells (Streptawell; Roche Applied Science) by incubation at 37°C for 1.5 h. After the wells were washed extensively, DNA synthesis reaction mixtures were added. The 60-μl reaction mixture contained 100 mM (NH4)2SO4, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 4% glycerol, 40 μg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA), 5 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), 1 μM digoxigenin-11-2′-deoxyuridine-5′-triphosphate (DIG-dUTP; Roche Applied Science), and in vitro-expressed proteins. All reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 30 min and then washed extensively with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The wells were incubated with anti-digoxigenin-peroxidase (anti-DIG-POD) antibody (Roche Applied Sciences) for 1 h at 37°C and then washed again with PBS. The substrate 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline)-sulfonate (ABTS; Roche) was added, and plates were gently rocked to allow color development. DNA synthesis was quantified by measuring the absorbance of each reaction at 405 nm, which is proportional to the amount of DIG-dUTP incorporated in the DNA. Samples were read with a microplate reader (Tecan GENios Pro).

Processive DNA synthesis assay.

To assess processive DNA synthesis, the primer described above was annealed to a second template (40) containing adenines only at its distal end (5′-biotin-AGCACTATTGACATTACAGAGTCGCCTTGGCTCTCTGGCTGTTCGTTGCGGGCTCCGCGTGCGTTGGCTTCGGTCGTCCCGTCAGCGGTCATTCATTGGC-3′). The primed template was bound to streptavidin-coated wells, and the 50-μl reaction mixtures contained 100 mM (NH)2S04, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 3 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 2% glycerol, 40 μg/ml BSA, 5 μM dATP, 5 μM dCTP, 5 μM dGTP, 1 μM DIG-dUTP, and in vitro-expressed proteins. The assay was conducted and results were obtained as described above.

Processivity interference assay.

The conditions of the processive DNA synthesis assay described above were followed in this assay that included both wild-type (wt) and mutant D4 in a single reaction. In each reaction, the amounts of A20 and E9 were kept constant. wt D4 was kept constant while increasing volumes of mutants were added (wt/mutant ratios of 1:1, 1:2, 1:4, and 1:8). wt and mutant D4 proteins were similarly expressed, as determined by incorporation of radiolabeled [32P]methionine-cysteine; as such, equivalent volumes reflect comparable protein levels. Total reticulocyte lysate was held constant in each reaction. When excess A20 was present as indicated in Fig. 6, the ratio of wt D4/mutant D4 was 1:4.

M13 DNA synthesis assay.

The in vitro M13 DNA synthesis assay was performed using a primed M13 template as described previously (41) with modifications. Reaction mixtures (25 μl) containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 8 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 40 mg/ml BSA, 8% glycerol, 0.1 mM EDTA, 20 fmol of primed M13mp18 single-stranded DNA, and 750 ng of Escherichia coli single-stranded binding protein were preincubated with in vitro-expressed enzymes and 60 μM of dATP, dGTP, and dTTP at 30°C for 3 min. Radiolabeled [32P]dCTP (20 μM) was added, reaction mixtures were incubated for 1 h, and then reactions were stopped with an equivalent volume of 1% SDS and 40 mM EDTA. Products were fractionated on a 1.2% agarose gel and visualized by PhosphorImager (Amersham).

DNA glycosylase assay.

The DNA glycosylase assay was performed as described previously (25). A single-stranded 45-base oligonucleotide (5′-AGCTACCATGCCTGCACGAAUTAAGCAATTCGTAATCATGGTCAT-3′) was 5′-end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP and purified. Labeled DNA was incubated with in vitro-expressed wt or mutant D4, E. coli UDG enzyme (New England BioLabs [NEB]), or Bacillus subtilis UDG inhibitor (UGI; NEB) in buffer containing 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) for 10 min at 37°C. UDG activity was stopped at 95°C for 5 min. NaOH (0.1 mM) was added following glycosylase cleavage to incise the abasic sites, and reaction mixtures were boiled at 95° for 5 min. Reaction products were analyzed by electrophoresis through a denaturing 10% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gel (7 M urea, 1× Tris-borate-EDTA) and visualized by autoradiography.

Transfection and coimmunoprecipitation.

A20 and D4 were cloned into pCMV-3Tag mammalian protein expression vectors with either a three-myc (pCMV-3Tag-2) or a three-flag (pCMV-3Tag-1) (Stratagene) tag using the following primer pairs: D4 forward (5′-CGCGGATCCATGAATTCAGTGACTGTATCACACG-3′) and D4 reverse (5′-CCCAAGCTTTTAATAAATAAACCCTTGAGC-3′) and A20 forward (5′-CGCGGATCCATGACTTCTAGCGCTGATTTAAC-3′) and A20 reverse (5′-CCCAAGCTTTCACTCGAATAATCTTTTTTTGACATCG-3′).

Human embryonic kidney 293T cells grown in 100 mM dishes were cultured and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (high glucose) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. Cells were transfected with 10 μg of each plasmid using the calcium phosphate transfection method. At 40 to 48 h posttransfection, cells were washed with cold PBS and lysed with cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, protease inhibitor [Roche]). Cell lysates were first incubated with protein G (immunoglobulin G [IgG]) beads (Invitrogen) to eliminate nonspecific binding and then incubated with 2 μl of anti-myc (Cell Signaling) or anti-flag (Stratagene) antibody for 1 h at 4°C. The lysate/antibody mixture was then incubated with IgG beads for 2 h at 4°C. Beads were washed extensively and then resuspended in LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen) and boiled for 10 min. Samples were fractionated on 12% Bis-Tris gels using MES buffer (Invitrogen) and visualized by Western blotting.

Western blot analysis.

Immunoprecipitated materials resolved by SDS-PAGE were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked in 5% dried milk in Tris-buffered saline plus 0.1% Tween 20 (TBS-T) and then incubated with primary antibody (anti-flag or anti-myc) overnight at 4°C. After being washed again in TBS-T, the membranes were incubated with anti-mouse (Pierce) or anti-rabbit (Bio-Rad) IgG antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. After subsequent washing steps, an enhanced chemiluminescence-based signal (SuperSignal West Femto maximum sensitivity substrate; Pierce) was used for protein detection.

Competitive DNA glycosylase assay.

The DNA glycosylase assay described above was performed in the presence of competitor DNA to look indirectly at DNA binding. The unlabeled competitor DNA shared the same sequence as the labeled strand, but contained a cytosine instead of a uracil (5′-AGCTACCATGCCTGCACGAACTAAGCAATTCGTAATCATGGTCAT-3′). Labeled DNA was kept constant in each reaction, while competitor DNA was included in increasing concentrations (1:1, 1:5, 1:10, 1:50, 1:100). Labeled and unlabeled DNAs were incubated together at room temperature before the protein and the reaction buffer were added. Both single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) and double-stranded DNA (dsDNA; annealed to its complement, 5′-ATGACCATGATTACGAATTGCTTAGTTCGTGCAGGCATGGTAGCT-3′) were assessed.

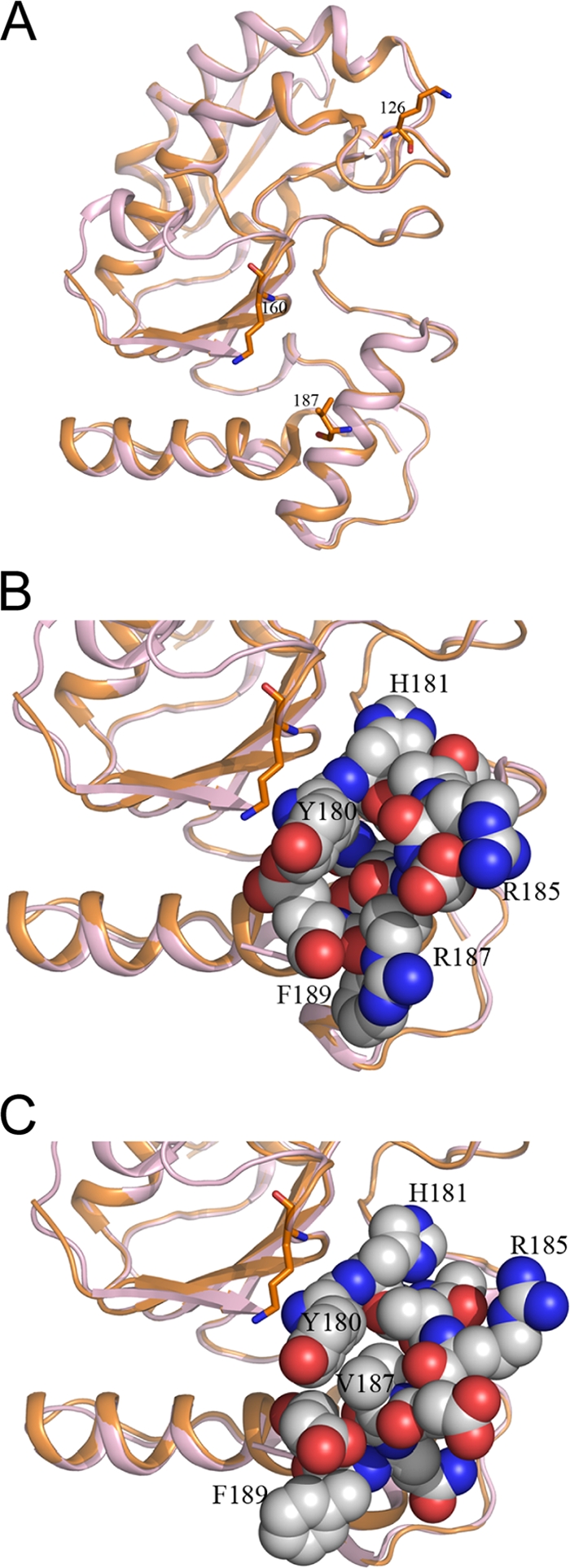

Crystal structure analysis of the R187V mutant.

Recombinant R187V mutant D4 with an N-terminal His6 tag was purified as described for wt D4 (39). Purified protein was crystallized by the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method using 1.5 M ammonium sulfate, 14% glycerol, and 0.1 M HEPES buffer (pH 7.5) in the reservoir. Intensity data extending to a resolution of 2.4 Å were collected in-house. The crystal structure was resolved by molecular replacement using the polyalanine model built from the coordinates for wt D4 (Protein Data Bank [PDB] accession no. 2OWQ) and refined to final R and free R (Rfree) (see Table 3) values of 22.1% and 27.3%, respectively. Programs MOLREP (46), REFMAC5 (33), and COOT (11) were used, respectively, in molecular replacement, structure refinement, and model building. The program PyMol was used to depict the cartoon and sphere diagrams (6).

Protein structure accession number.

Final atomic coordinates and the structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB accession no. 3NT7).

RESULTS

D4 is required in addition to A20 for vaccinia virus processive DNA synthesis.

The protein A20 has been shown to be required for vaccinia virus replication. Temperature-sensitive viruses with mutations in A20 are blocked in DNA replication (16) and are defective in processive DNA synthesis (37). Additionally, A20 chromatographically purified from vaccinia virus-infected cell extract was identified as a component of the processive DNA replication complex based on its ability to enable the polymerase E9 to synthesize extended DNA strands from a primed, single-stranded M13 template (19). Moreover, extracts from vaccinia virus-infected cells overexpressing A20 and E9 had increased processive polymerase activity (19). However, when A20 and E9 were expressed in vitro, we did not observe extended DNA synthesis. Significantly, we and others were not able to demonstrate any physical interaction between the two proteins (19, 41; data not shown). It is possible that when A20 and E9 were obtained from infected cell lysate, one or more additional components required for processivity copurified with the two replication proteins. To address whether further viral products are required for processive DNA synthesis, we cloned and expressed singular vaccinia virus replication proteins.

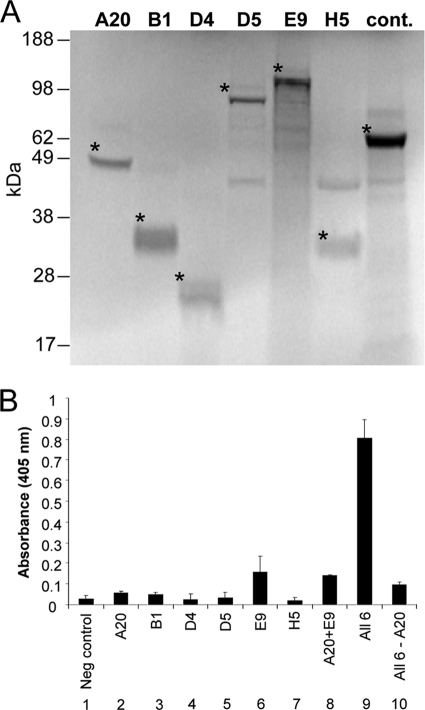

Six genes known to be important for viral replication (8, 32) were cloned directly from the vaccinia virus genome. They encode the following proteins: E9, the replicative DNA polymerase (18, 44); A20, which has a role in processive DNA synthesis, as described above (19); B1, a serine/threonine protein kinase (2, 24); D4, a uracil DNA glycosylase (30, 42, 45); D5, a DNA-independent dNTPase (12); and H5, a substrate of B1 associated with the virosomes (3-5, 7, 32). These proteins were synthesized individually in an in vitro transcription/translation system. The translated A20, B1, D4, D5, E9, and H5 products corresponded in size to their known molecular masses (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

Increased E9 DNA synthesis activity requires a component in addition to A20. (A) In vitro-transcribed/translated [35S]methionine-cysteine labeled proteins were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by PhosphorImager. Asterisks denote the position of each translated product. Molecular masses of the full-length proteins are as follows: A20, 49 kDa; B1, 34 kDa; D4, 25 kDa; D5, 90 kDa; E9, 116 kDa; and H5, 36 kDa. Luciferase (61.5 kDa) is included as a control (cont.). The 42-kDa band present in some lanes is due to background labeling of the reticulocyte lysate used for transcription (17). (B) In vitro-expressed proteins A20, B1, D4, D5, E9, and H5 were evaluated for nucleotide incorporation using the DNA synthesis assay. The proteins were assessed either individually or in combinations, as indicated. All 6, all six proteins (A20, B1, D4, D5, E9, and H5); All 6 − A20, all of the translated proteins except A20. Luciferase was included as a negative control (Neg control). DNA synthesis was measured by DIG-dUTP incorporation on a template with uniformly incorporated adenines. This is a representative experiment in which reactions were performed in triplicate.

Five of the in vitro-translated proteins (A20, B1, D4, D5, and H5) were each evaluated for their ability to increase the DNA synthesis activity of the translated polymerase E9. It should be noted that synthesizing the vaccinia virus proteins in vitro, rather than attempting to purify them from infected cell extracts, precludes the possible inclusion of associated replication proteins that could obfuscate the results. We employed a DNA synthesis assay developed in our laboratory (23, 40) which quantifies the incorporation of DIG-dUTP on a primed 100-nucleotide template that contains uniformly distributed adenines. This provides an opportunity to observe minimal incorporation. As shown in Fig. 1B, when the six proteins were tested individually, only E9 was able to incorporate dNTPs, as expected (lane 6). Notably, when A20 and E9 were combined (lane 8), the extent of nucleotide incorporation did not differ from that of the polymerase alone, supporting our hypothesis that there is another component required for processive DNA synthesis. This premise was substantiated when the presence of all six proteins in the reaction (lane 9) resulted in a >5-fold increase in DNA synthesis activity compared to results for the polymerase alone. Importantly, only minimal nucleotide incorporation occurred in a reaction mixture containing all of the translated proteins except A20, confirming the essential role of this protein in DNA synthesis (lane 10). Together, these results suggest that A20 and at least one other viral protein enhance nucleotide incorporation by E9.

We next determined which viral proteins in addition to A20 are required by E9 for processive DNA synthesis. For these experiments, we performed the DNA synthesis assay utilizing a 100-nucleotide template that permits DIG-dUTP to be incorporated only at the distal end. As E9 alone can synthesize only approximately 10 nucleotides before dissociating from the DNA (27), this system serves as a more stringent measure of processivity, since efficient incorporation of DIG-dUTP can occur only when E9 is in the presence of its cognate processivity factors.

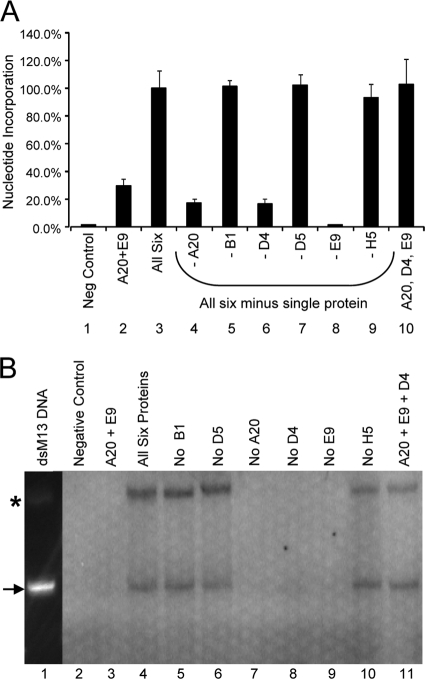

To identify replication proteins that are required for processive DNA synthesis, we individually omitted A20, B1, D4, D5, E9, and H5 from DNA synthesis reaction mixtures containing the five other replication proteins. As seen in Fig. 2A, the elimination of A20 (lane 4) or E9 (lane 8) from the DNA synthesis reactions prevented increased synthesis, as expected. Withholding B1, D5, or H5 (lane 5, 7, or 9, respectively) had no effect on DNA synthesis. However, when the protein D4 was absent (lane 6), the level of DNA synthesis observed was almost identical to the level seen when A20 was absent. This result suggested that processive DNA synthesis by the E9 polymerase requires D4 in addition to A20. Indeed, the triad of E9, A20, and D4 was as effective as all six proteins in stimulating DNA synthesis (lane 10).

FIG. 2.

D4 is required for processive DNA synthesis. (A) The processive DNA synthesis assay was used to evaluate combinations of five of the six in vitro-transcribed/translated proteins (A20, B1, D4, D5, E9, and H5), excluding the one indicated in lanes 4 to 9. DNA synthesis was measured by DIG-dUTP incorporation on a template with adenines incorporated only at the distal end. In vitro-translated luciferase was used in the DNA synthesis reaction as a negative control (Neg Control). Results are shown as a percentage of nucleotide incorporation relative to that of the reaction mixture containing all six proteins. This is a representative experiment in which reactions were performed in triplicate. (B) Different combinations of five of the six in vitro-expressed proteins, A20, B1, D4, D5, E9, and H5, were tested for their ability to synthesize full-length DNA from a primed 7,249-nucleotide M13 template. Labeled DNA products were separated by electrophoresis on a 1.2% agarose gel and visualized by PhosphorImager. The M13 lane contains full-length double-stranded M13 DNA, as detected by CyberGold. In vitro-translated luciferase was used in the DNA synthesis reaction as a negative control. The arrow indicates the full-length double-stranded M13 product; the asterisk indicates joint molecule formation (47-49).

To validate that the DNA synthesis activity observed reflects processive DNA synthesis, the six proteins were used to replicate a primed 7,249-nucleotide M13 DNA template in a rigorous assay in which the newly synthesized reaction products are visualized on a gel. Synthesis of this extended template requires processivity. As shown in Fig. 2B, when all six proteins (A20, B1, D4, D5, E9, and H5) were combined, full-length product was synthesized (lane 4). This result is in accord with the results of the processive DNA synthesis plate assay described above (Fig. 2A) and is the first demonstration that processivity can be achieved with in vitro-translated vaccinia virus proteins. In contrast, when E9 and A20 were the only proteins present, no extended DNA product was observed (Fig. 2B, lane 3). Omission of B1, D5, or H5 did not affect the production of full-length synthesis product (lane 5, 6, or 10, respectively). However, processive DNA synthesis failed to occur if A20, D4, or E9 was omitted (lane 7, 8, or 9, respectively). Furthermore, extended DNA products were visible when only D4 was added to the necessary proteins A20 and E9 (lane 11). These results confirm that A20 and D4 are both required by E9 for processive DNA synthesis and that this protein triad is sufficient for processivity to occur.

Construction of D4 point mutants.

Although it was shown previously that A20 and D4 interact (15, 26, 41), it remains to be disclosed how these proteins function in processive DNA synthesis. While processivity is the sole function assigned to A20 thus far, D4 has an additional role as a uracil DNA glycosylase (UDG), a repair enzyme that recognizes and cleaves uracils that either are misincorporated in DNA or are generated by cytosine deamination. Significantly, while D4 is critical for viral replication, its ability to excise uracil is not essential (9, 30, 41, 42, 45). Consequently, the requirement of D4 in processive DNA synthesis is separate from its ability to repair DNA.

To further examine the essential role of D4 in processivity, we sought to identify residues that are important for DNA synthesis. We generated 21 point mutants throughout the length of the D4 coding region (Table 2). Most of these mutations neutralized the charge of positive residues, while one (P71H) substituted a residue that is present in other UDGs. Additionally, a mutation was introduced in the UDG catalytic site (D68N), which is known to eliminate UDG activity (9, 10, 41). The D4 mutants were expressed in the in vitro transcription/translation system used above.

TABLE 2.

Enzymatic activity of D4 mutants

| Mutant | Processive activity | UDG activity |

|---|---|---|

| D68N | Yes | No |

| P71H | Yes | Yes |

| T85A | Yes | Yes |

| S88A | Yes | Yes |

| E91V | Yes | Yes |

| SSIS94-97AAIA | Yes | Yes |

| K126R | Yes | Yes |

| K126V | No | Yes |

| L127A | Yes | Yes |

| T130A | Yes | Yes |

| K131V | No | No |

| S132A | Yes | Yes |

| L158A | Yes | Yes |

| K160V | No | Yes |

| T161A | Yes | Yes |

| S164A | Yes | Yes |

| S172A | Yes | Yes |

| T175A | Yes | Yes |

| T176A | Yes | Yes |

| R187V | No | Yes |

| S194A | Yes | Yes |

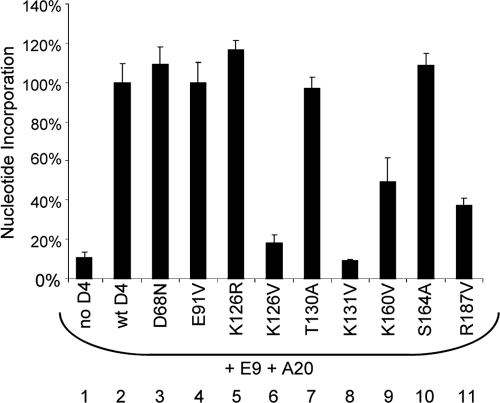

Identification of D4 point mutants defective in processivity.

The D4 mutants were first evaluated using the processive DNA synthesis assay. A subset of these results that includes key mutants is shown in Fig. 3, and all of the findings are summarized in Table 2. Four mutants (K126V, K131V, K160V, and R187V) were substantially impaired in their ability to enable extended DNA synthesis in the presence of E9 and A20 (lanes 6, 8, 9, and 11, respectively). In each of these nonfunctional mutated proteins, neutral amino acids were substituted for positively charged ones. However, when a conserved amino acid was substituted for K126 (lane 5), processive DNA synthesis was not diminished. This indicates that it is the positive charge on residue 126 that is essential for processivity. Also of note is D68N, which retains complete processive activity despite the mutation in its UDG catalytic site (lane 3). This result is in keeping with previous findings that the UDG repair activity of D4 is not required for viral replication (9, 41).

FIG. 3.

Identification of D4 mutants that are defective in processive DNA synthesis. The processive DNA synthesis assay was used to evaluate the ability of D4 mutants to function in processivity. All lanes contain A20 and E9 in addition to the protein of interest. The results shown are from a subset of mutants, and results were normalized to that for wt D4. This is a representative experiment in which reactions were performed in triplicate.

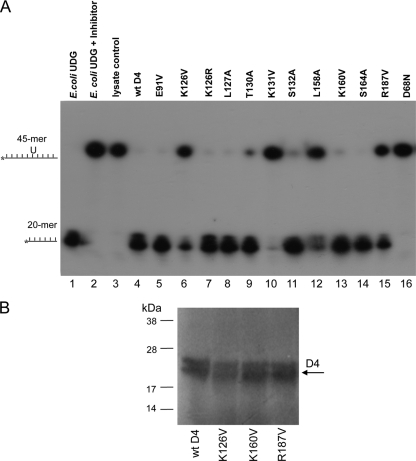

D4 processivity mutants maintain glycosylase function.

All of the D4 mutants were next examined for UDG catalytic activity. The proteins were incubated with uracil-containing, end-labeled single-stranded DNA, as single-stranded DNA is the preferential substrate for D4 (38). When D4 recognizes and excises a uracil, the resulting abasic site in the DNA is susceptible to cleavage with NaOH. The cleaved product is visualized as the faster-migrating product on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel.

The key findings are presented in Fig. 4A. Of particular interest are the four mutants (K126V, K131V, K160V, R187V) that were unable to function in the processive DNA synthesis assay. Three of these mutants, K126V, K160V, and R187V, retained the ability to excise uracil (lanes 6, 13, and 15, respectively), though the cleavage efficiencies of K126V and R187V were partially diminished compared to that of wild-type (wt) D4. This result demonstrates a separation of function between the processive and repair activities of D4. While it has previously been shown that the UDG activity of D4 is not required for viral replication and processivity (9, 41), this is the first report that shows, in contrast, that the processivity function of D4 is not required for glycosylase repair activity. The fourth mutant, K131V, had no UDG activity (lane 10) and was not pursued further, as it was uncertain whether the substitution caused a major conformational change that rendered the protein wholly nonfunctional. As expected, D68N, which is altered in the UDG catalytic site, was incapable of cleaving uracil (lane 16).

FIG. 4.

Three D4 processivity mutants retain UDG activity. (A) In vitro-expressed wt and mutant D4 proteins were incubated with end-labeled ssDNA containing uracil. Following treatment with NaOH, which cleaves abasic sites, reactions were run on a denaturing gel. Shown are the results from a subset of mutants. E. coli UDG used either alone or with Bacillus subtilis UDG inhibitor served as a positive or negative control, respectively. Unprogrammed reticulocyte lysate used for in vitro expression was included as a control. (B) In vitro-expressed [35S]methionine-cysteine-labeled wt and mutant D4 proteins were analyzed by electrophoresis and visualized by PhosphorImager. The position of D4 is indicated by the arrow. It is not known why D4 consistently appears as a doublet.

In summary, we have generated three D4 mutants (K126V, K160V, and R187V) that lack processive activity but retain UDG catalytic activity. It is important to note that the expression levels of the three mutant proteins are similar to that of the wt, ruling out differential expression as the cause of their inability to function in processive DNA synthesis (Fig. 4B). These are the first D4 mutants reported that fail in processivity but retain UDG activity.

D4 processivity mutants interfere with wt D4 in processive DNA synthesis.

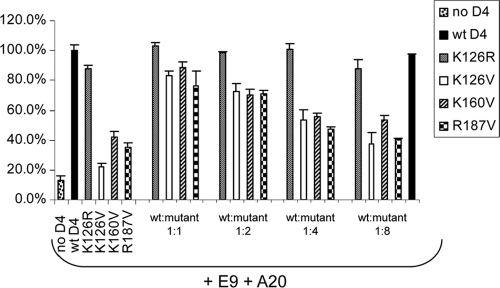

We next inquired if the D4 mutants K126V, K160V, and R187V preserved any aspect of the processivity mechanism. We designed a processivity interference assay in which we examined whether the mutant proteins could interfere with wt D4 in the processive DNA synthesis assay. As shown in Fig. 5, when a constant amount of wt D4 was incubated with increasing amounts of each of the processivity mutant D4 proteins (at ratios of 1:1, 1:2, 1:4, and 1:8), nucleotide incorporation decreased relative to incorporation achieved by wt D4 alone. In contrast, the inclusion of conserved-charge mutant K126R, which is functional in processive DNA synthesis (Fig. 3, lane 5), did not diminish nucleotide incorporation. Additionally, when wt D4 was incubated with itself in a 1:8 ratio (Fig. 5, last lane), nucleotide incorporation remained the same, confirming that interference is not due to mass effect. The abilities of the mutant proteins K126V, K160V, and R187V to interfere with wt D4 in the processive DNA synthesis assay clearly demonstrate that the mutants retain partial function required for processivity.

FIG. 5.

D4 mutants interfere with wt D4 in processivity. Increasing amounts of mutant D4 proteins (K126R, K126V, K160V, R187V) were introduced into processive DNA synthesis reactions that contain fixed amounts of E9, A20, and wt D4. The relative amounts of wt D4 to mutant D4 used were 1:1, 1:2, 1:4, and 1:8. The last lane represents a reaction mixture containing wt D4/wt D4 at a 1:8 ratio, treated in the same manner as wt D4/mutant D4. Nucleotide incorporation was normalized to reaction mixtures containing only wt D4. Shown is a representative experiment, and all reactions were performed in triplicate.

D4 processivity mutants retain the ability to bind A20.

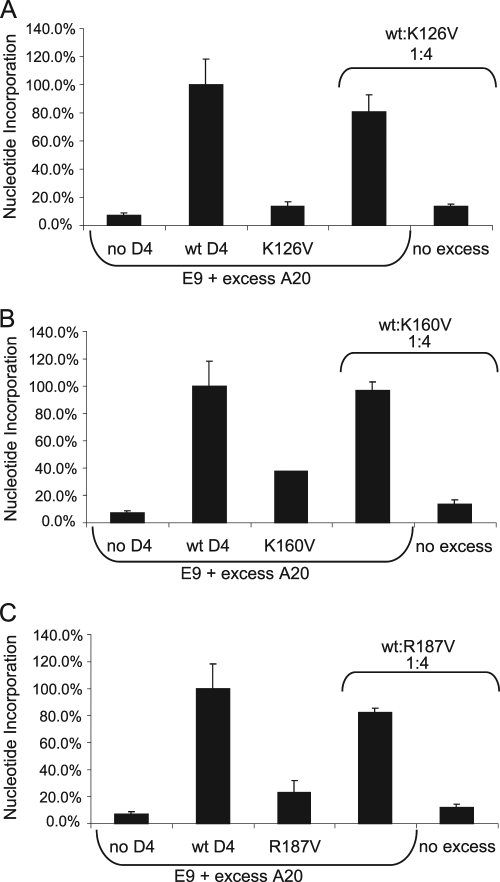

While there are several possibilities to account for how K126V, K160V, and R187V interfere with wt D4 in processive DNA synthesis, one strong likelihood is that the mutant proteins sequester A20. It is known that D4 interacts with A20 (15, 26, 41) and that both are required for processive DNA synthesis (see above; 41). To test this hypothesis, we performed the processivity interference assay using a 1:4 ratio of wt/mutant D4. This time, an excess amount of A20 was included in the reactions at a saturating concentration. As shown in Fig. 6A to C, the addition of excess A20 restored nucleotide incorporation in reaction mixtures containing wt and mutant D4 to levels similar to that seen with the wt alone. These results suggest that the processivity mutants K126V, K160V, and R187V are able to bind A20.

FIG. 6.

Excess A20 restores processivity when both wt and mutant D4 are present. The processivity interference assay was performed in the presence of E9 and excess A20 with wt D4, mutant D4 (K126V [A], K160V [B], R187V [C]), or a 1:4 ratio of wt D4/mutant D4. Reactions labeled “no excess” contain a 1:4 ratio of wt D4/mutant D4, E9, and no excess A20. Results were normalized to reaction mixtures containing wt D4 and excess A20. Shown is a representative experiment in which reactions were performed in triplicate.

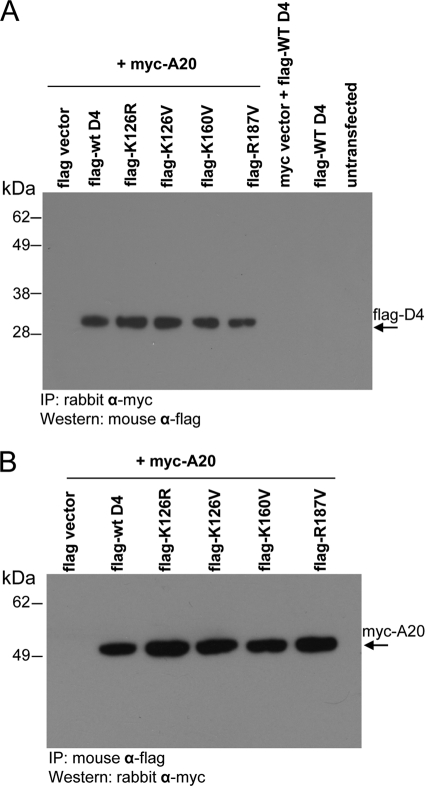

To directly examine the interaction between A20 and the D4 mutants, we constructed the tagged expression plasmids myc-A20 and flag-D4 and evaluated their binding following cotransfection into 293T cells. When the transfected cell lysates were coimmunoprecipitated with anti-myc antibody and probed with anti-flag antibody, similar amounts of wt and mutant D4 proteins were observed (Fig. 7A). Conversely, when the lysates were coimmunoprecipitated with anti-flag antibody and probed with anti-myc antibody, similar amounts of A20 protein were observed (Fig. 7B). The expression levels of wt and mutant flag-D4 proteins in the transfected cell lysates were comparable to each other, as were the expression levels of myc-A20 in the cotransfected cells (data not shown). These results conclusively show that the D4 processivity mutants retain the ability to bind to A20. Significantly, these findings rule out a failure to interact with A20 as an explanation for why the D4 mutants are incapable of functioning in processive DNA synthesis.

FIG. 7.

D4 processivity mutants retain A20 binding ability. (A and B) 293T cells were transfected with flag-D4 (wt or mutants) and myc-A20 or control vectors. Cell extracts were coimmunoprecipitated with anti-myc (A) or anti-flag (B) antibody and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-flag (A) or anti-myc (B) antibody. α, anti-.

D4 processivity mutants retain the ability to bind DNA.

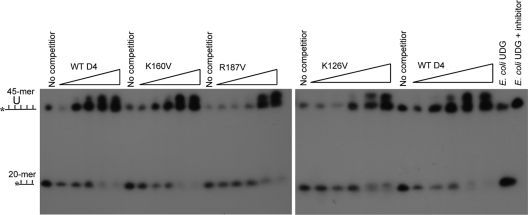

Since processivity factors associate with the DNA template to facilitate nucleotide incorporation, we inquired whether the K126V, K160V, and R187V mutations affect the capability of D4 to bind DNA. In its capacity as a UDG repair enzyme, D4 searches the template for uracils that are present due to misincorporation or cytosine deamination. UDGs are thought to scan DNA with rapid kinetics by sliding or hopping mechanisms that are challenging to capture (13, 36). Indeed, attempts to observe direct UDG-DNA binding have been unsuccessful or require catalytically inactive mutants (21, 34, 35). Consistent with this have been our own unsuccessful attempts to measure direct D4-DNA binding. We thus employed an indirect approach to compare the capacities of wt D4 and the three D4 processivity mutants (K126V, K160V, and R187V) to bind DNA. We assessed the uracil excision activities of wt D4 and each of the mutants in the presence of excess competitor DNA. Specifically, we first incubated the labeled, substrate-containing DNA with unlabeled double-stranded DNA before adding D4 to the reaction. This allowed us to determine whether the presence of competitor DNA resulted in a decrease of cleaved product. As shown in Fig. 8, wt D4 and each of the three mutants acted similarly, excising less uracil in the presence of increasing concentrations of competitor DNA. Similar activity was observed when single-stranded DNA was used as a competitor (data not shown). These results indicate that the D4 mutants bind DNA in the same manner as wt D4 and that their inability to function in processivity is not caused by a deficiency in DNA interaction.

FIG. 8.

D4 processivity mutants retain DNA binding ability. D4 (wt and mutant) was incubated with a fixed amount of labeled uracil-containing ssDNA and increasing amounts of unlabeled dsDNA competitor DNA (1:1, 1:5, 1:10, 1:50, 1:100). Following treatment with NaOH, which cleaves abasic sites, reactions were run on a denaturing gel. E. coli UDG alone and in the presence of B. subtilis UDG inhibitor was used as a positive and negative control, respectively.

R187V crystal structure indicates only local charge alteration.

Given the ability of the processivity mutants to bind A20 and DNA, we sought to understand the influence of the mutations on the three-dimensional structure of D4. Toward this end, we determined the crystal structure of the R187V mutant at a 2.4-Å resolution (PDB accession no. 3NT7). Details of data collection and refinement statistics are provided in Table 3. The overall structure of the mutant form proved to be very similar to that of wt D4 (PDB accession no. 2OWR) (Fig. 9A). Residue 187 lies on a loop which connects the β9 strand to helix 9. The side chain of the mutated valine residue points to the hydrophobic side chains of Y180. The region around the mutation is flexible; most molecules in both the trigonal (PDB accession no. 2OWQ) and orthorhombic (PDB accession no. 2OWR) forms of the wt protein structure have partial or complete disorder in that area (39). For comparison with R187V, we selected one molecule (D) of the orthorhombic crystal form of wt D4 in which residues 180 to 190 were included in the final refined model. There are notable differences in the distribution of the surface charge around the mutated residue (compare Fig. 9B and C). Interestingly, both K126 and K160 are also located in surface-exposed loop regions of D4 (Fig. 9A). As with R187, replacement of these residues with valine is expected to alter the distribution of the local surface charge but to have little effect on the overall structure of the mutant forms.

TABLE 3.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Parametera | Value(s)b |

|---|---|

| Crystal and intensity data | |

| Space group | P3221 |

| Unit cell (Å) | a = b = 85.195, c = 139.439 |

| α = β = 90.0, γ = 120.0° | |

| Vm (Å3/Da) | 2.98 |

| Solvent content (%) | 58.41 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 20-2.40 (2.44-2.40) |

| Completeness (%) | 89.9 (93.9) |

| Rsym | 0.052 (0.312) |

| Overall I/σ(I) | 19.6 |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 20-2.40 (2.46-2.40) |

| No. of reflections | 19,959 |

| R value | 0.221 (0.290) |

| Free R value | 0.273 (0.381) |

| No. of atoms | 3,574 |

| No. of water molecules | 73 |

| No. of ligands (glycerol) | 2 |

| Estimated coordinate errors (Luzzati plot) | 0.391 |

| Deviations from ideality | |

| Bond distances (Å) | 0.009 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.2 |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Core + allowed + generously allowed (%) | 91.0 + 7.9 + 0.5 |

| Outliers (%) | 0.5 |

Vm (Å3/Da), volume of the unit cell (Å3)/molecular mass (Da). Rsym, Σhkl||Ihkl − (Ihkl)||Σhkl(Ihkl), where (Ihkl) is the mean intensity of symmetry-related observations of a unique reflection. I/σ(I), <I>/<σ(I)> where <I> and <σ(I)> are the average intensity and average errors in intensity, respectively. R value, Σ|Fobs − Fcal|/∑|Fobs|. The free R value is calculated similarly but uses a subset of 5.2% (1,103) of the reflections, which are set aside as a “test set” for the calculation of the free R value and are not included in refinement.

Values for the highest-resolution shell are in parentheses.

FIG. 9.

Crystal structure of R187V reveals alteration only in local surface charge. (A) Cartoon diagram showing the overall similarity of the superimposed crystal structures of wt D4 (light pink; PDB accession no. 2OWR) and the R187V mutant (orange; PDB accession no. 3NT7). The conservation of the overall structures is reflected in the root mean square (r.m.s.) deviation for all C-alpha atoms, being approximately 0.5 Å. Residues 126, 160, and 187 are shown in stick model. (B and C) Amino acid residues 180 to 190 are shown as spheres in the structures of wt D4 (B) and the R187V mutant (C). Selected residues in the vicinity are labeled to show orientation. Carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen atoms are colored white, red, and blue, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have shown that two vaccinia virus proteins, A20 and D4, are necessary and sufficient to enable the vaccinia virus DNA polymerase E9 to processively synthesize DNA. This finding is in agreement with that of others (41). However, the mechanism of how these three essential proteins function in replication has yet to be resolved. To gain greater insight into vaccinia virus processivity, we sought to disclose the role of D4, which also functions as a uracil DNA glycosylase (UDG). We generated three D4 point mutants, K126V, K160V, and R187V, which fail to function in processive DNA synthesis. All of these mutants retain UDG catalytic activity. This specifically demonstrates that UDG catalytic activity and processivity are independent functions of D4, which is in accord with the finding that UDG activity is unnecessary for vaccinia virus replication and processive DNA synthesis (9, 41). Notably, K126V, K160V, and R187V are the first mutants shown to be functional in UDG activity but deficient in processivity. Most importantly, these D4 processivity mutants retain the ability to bind A20 and DNA. While the precise reasons for their inability to function in processivity remain unclear, these mutants may provide unique insights into the mechanistic role of D4 in processive DNA synthesis.

Though the structure of D4 is known, whether D4 has a classical processivity clamp configuration and how the processivity complex is assembled remain to be determined (39). D4 cannot bind directly to the polymerase E9 (41). Instead, the two enzymes interact through the protein A20. One model for the vaccinia virus processivity complex is that A20 serves as a bridge, joining D4 to E9. As both D4 and E9 bind to DNA in their respective roles as a repair enzyme and a polymerase, it is possible that A20 also stabilizes the two proteins to the DNA to diminish their dissociation from the template. Additionally, it has been suggested that A20 acts as a scaffold for other replication proteins (41). Whatever the mechanism, it is apparent that the interaction between A20 and D4 is critical for processivity, as we have demonstrated that E9 is not processive in the presence of only A20. This is substantiated by the D4 mutant G179R, which has a reduced capacity to interact with A20 and is not functional in processivity (41). In contrast, the three processivity mutants reported in this paper, K126V, K160V, and R187V, all retain intact binding to A20. This was demonstrated indirectly, as each mutant was able to compete with wt D4 for A20 in the processive DNA synthesis assay, and directly, as each was able to pull down A20.

While the D4 binding site on A20 has been mapped to the 25 N-terminal residues (15), the A20 binding site on D4 remains unknown. Information about the D4 residues required for binding to A20 is scant, and the discovery of these three processivity mutants may offer new insight into this interaction. The results from this study indicate that D4 residues K126, K160, and R187 are not singly critical for A20 binding, though they, along with other residues, might contribute to the interaction. It has been suggested that proper folding of A20 is dependent upon its association with D4 (41). In this sense, it is possible that, though binding can occur, these D4 mutants cannot facilitate the correct conformation of A20 that is necessary for a productive interaction with E9 to enable extended strand synthesis.

In addition to their ability to bind A20, these mutants display a DNA binding capability that is similar to that of wt D4, which adds to the complexity of the failure of the mutants in processive DNA synthesis. A comparison of the experimentally determined crystal structure of the R187V mutant with the reported structure of wt D4 reveals no significant change in the overall structure of the protein. The molecular models of K126V and K160V (data not shown) similarly reveal a preservation of structural integrity. This indicates that structural disintegration is not responsible for lack of processive function and may account for the retained ability of the mutants to bind A20 and DNA. This observation is in contrast to that for mutant G179R, discussed above, which possesses a reduced capacity to bind to A20 (41). Its structural model predicts that the mutation causes significant structural rearrangement to accommodate the large, basic arginine residue into a hydrophobic pocket (39). However, while the global structure of the three processivity mutants reported here remains intact, their residue substitutions alter the charge of the local environment. This finding suggests that the effects of these mutations are exerted through changes in the vicinity of the mutated residue. As such, it is possible that a positive charge is required at positions 126, 160, and 187 for D4 to function in processive DNA synthesis. Indeed, this idea is supported by the conserved mutant K126R, which maintains a positive charge and is fully functional in processivity.

In summary, we have demonstrated that three proteins, A20, D4, and E9, are necessary and sufficient for vaccinia virus processive DNA synthesis. We have generated three D4 point mutants (K126V, K160V, and R187V) that do not function in processivity yet retain all other known functions of D4—A20 binding, DNA binding, and UDG catalytic activity, which is not required for processivity. Crystal structure analysis and molecular modeling reveal that each mutation alters only local charge distribution, suggesting that the positive charges at these residues are significant. These D4 mutants may help clarify the mechanistic role of D4 in the process of vaccinia virus processive DNA synthesis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant 5UO1-AI 082211 to R.P.R., Middle Atlantic Regional Center of Excellence grant U54-AI 057168 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to R.P.R., and NIH grant T32 AI055400 to A.M.D.S.

We thank Stuart Isaacs, Gary Cohen, and Roselyn Eisenberg for providing us with the WR strain of vaccinia virus and Mihai Ciustea for partially cloning A20 and E9. We thank Yan Yuan for providing the pCMV-3Tag expression plasmids and Lorenzo Gonzalez, Yan Wang, and Norbert Schormann for technical assistance. We thank Christa Heyward for critical readings of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 September 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baker, T. A., and S. P. Bell. 1998. Polymerases and the replisome: machines within machines. Cell 92:295-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banham, A. H., and G. L. Smith. 1992. Vaccinia Virus gene B1R encodes a 34-kDa serine/threonine protein kinase that localizes in cytoplasmic factories and is packaged into virions. Virology 191:803-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beaud, G., and R. Beaud. 1997. Preferential virosomal location of underphosphorylated H5R protein synthesized in vaccinia virus-infected cells. J. Gen. Virol. 78:3297-3302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beaud, G., R. Beaud, and D. Leader. 1995. Vaccinia virus gene H5R encodes a protein that is phosphorylated by the multisubstrate vaccinia virus B1R protein kinase. J. Virol. 69:1819-1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D'Costa, S. M., T. W. Bainbridge, S. E. Kato, C. Prins, K. Kelley, and R. C. Condit. 2010. Vaccinia H5 is a multifunctional protein involved in viral DNA replication, postreplicative gene transcription, and virion morphogenesis. Virology 401:49-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delano, W. L. 2002. The PyMOL molecular graphics system. DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, CA.

- 7.DeMasi, J., and P. Traktman. 2000. Clustered charge-to-alanine mutagenesis of the vaccinia virus H5 gene: isolation of a dominant, temperature-sensitive mutant with a profound defect in morphogenesis. J. Virol. 74:2393-2405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Silva, F., and B. Moss. 2005. Origin-independent plasmid replication occurs in vaccinia virus cytoplasmic factories and requires all five known poxvirus replication factors. Virol. J. 2:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Silva, F. S., and B. Moss. 2003. Vaccinia virus uracil DNA glycosylase has an essential role in DNA synthesis that is independent of its glycosylase activity: catalytic site mutations reduce virulence but not virus replication in cultured cells. J. Virol. 77:159-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellison, K., W. Peng, and G. McFadden. 1996. Mutations in active-site residues of the uracil-DNA glycosylase encoded by vaccinia virus are incompatible with virus viability. J. Virol. 70:7965-7973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emsley, P., and K. Cowtan. 2004. COOT: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60:2126-2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans, E., N. Klemperer, R. Ghosh, and P. Traktman. 1995. The vaccinia virus D5 protein, which is required for DNA replication, is a nucleic acid-independent nucleoside triphosphatase. J. Virol. 69:5353-5361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedman, J. I., and J. T. Stivers. 2010. Detection of damaged DNA bases by DNA glycosylase enzymes. Biochemistry 49:4957-4967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hingorani, M. M., and M. O'Donnell. 2000. DNA polymerase structure and mechanisms of action. Curr. Org. Chem. 4:887-913. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishii, K., and B. Moss. 2002. Mapping interaction sites of the A20R protein component of the vaccinia virus DNA replication complex. Virology 303:232-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishii, K., and B. Moss. 2001. Role of vaccinia virus A20R protein in DNA replication: construction and characterization of temperature-sensitive mutants. J. Virol. 75:1656-1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson, R. J., and T. Hunt. 1983. Preparation and use of nuclease-treated rabbit reticulocyte lysates for the translation of eukaryotic messenger RNA. Methods Enzymol. 96:50-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones, E. V., and B. Moss. 1984. Mapping of the vaccinia virus DNA polymerase gene by marker rescue and cell-free translation of selected RNA. J. Virol. 49:72-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klemperer, N., W. McDonald, K. Boyle, B. Unger, and P. Traktman. 2001. The A20R protein is a stoichiometric component of the processive form of vaccinia virus DNA polymerase. J. Virol. 75:12298-12307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kornberg, A. 1988. DNA replication. J. Biol. Chem. 263:1-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krusong, K., E. P. Carpenter, S. R. W. Bellamy, R. Savva, and G. S. Baldwin. 2006. A comparative study of uracil-DNA glycosylases from human and herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Biol. Chem. 281:4983-4992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuriyan, J., and M. O'Donnell. 1993. Sliding clamps of DNA polymerases. J. Mol. Biol. 234:915-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin, K., and R. P. Ricciardi. 2000. A rapid plate assay for the screening of inhibitors against herpesvirus DNA polymerases and processivity factors. J. Virol. Methods 88:219-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin, S., W. Chen, and S. S. Broyles. 1992. The vaccinia virus B1R gene product is a serine/threonine protein kinase. J. Virol. 66:2717-2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu, C.-C., H.-T. Huang, J.-T. Wang, G. Slupphaug, T.-K. Li, M.-C. Wu, Y.-C. Chen, C.-P. Lee, and M.-R. Chen. 2007. Characterization of the uracil-DNA glycosylase activity of Epstein-Barr virus BKRF3 and its role in lytic viral DNA replication. J. Virol. 81:1195-1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCraith, S., T. Holtzman, B. Moss, and S. Fields. 2000. Genome-wide analysis of vaccinia virus protein-protein interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:4879-4884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDonald, W., and P. Traktman. 1994. Vaccinia virus DNA polymerase: in vitro analysis of parameters affecting processivity. J. Biol. Chem. 269:31190-31197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDonald, W. F., and Traktman, P. 1994. Overexpression and purification of the vaccinia virus DNA polymerase. Protein Expr. Purif. 5:409-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDonald, W. F., N. Klemperer, and P. Traktman. 1997. Characterization of a processive form of the vaccinia virus DNA polymerase. Virology 234:168-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Millns, A. K., M. S. Carpenter, and A. M. DeLange. 1994. The vaccinia virus-encoded uracil DNA glycosylase has an essential role in viral DNA replication. Virology 198:504-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moss, B. 2001. Poxviridae: the viruses and their replication, p. 2849-2883. In D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, D. E. Griffin, R. A. Lamb, M. A. Martin, B. Roizman, and S. E. Straus (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA.

- 32.Murcia-Nicolas, A., G. Bolbach, J.-C. Blais, and G. Beaud. 1999. Identification by mass spectroscopy of three major early proteins associated with virosomes in vaccinia virus-infected cells. Virus Res. 59:1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murshudov, G. N., A. A. Vagin, and E. J. Dodson. 1997. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53:240-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Panayotou, G., T. Brown, T. Barlow, L. H. Pearl, and R. Savva. 1998. Direct measurement of the substrate preference of uracil-DNA glycosylase. J. Biol. Chem. 273:45-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Panayotou, G., and L. H. Pearl. 2001. Substrate specificity of DNA repair enzymes: accurate quantification using BIAcore SPR analysis. BIAjournal 2001:1.11-1.13. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Porecha, R. H., and J. T. Stivers. 2008. Uracil DNA glycosylase uses DNA hopping and short-range sliding to trap extrahelical uracils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:10791-10796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Punjabi, A., K. Boyle, J. DeMasi, O. Grubisha, B. Unger, M. Khanna, and P. Traktman. 2001. Clustered charge-to-alanine mutagenesis of the vaccinia virus A20 gene: temperature-sensitive mutants have a DNA-minus phenotype and are defective in the production of processive DNA polymerase activity. J. Virol. 75:12308-12318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scaramozzino, N., G. Sanz, J. M. Crance, M. Saparbaev, R. Drillien, J. Laval, B. Kavli, and D. Garin. 2003. Characterisation of the substrate specificity of homogeneous vaccinia virus uracil-DNA glycosylase. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:4950-4957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schormann, N., A. Grigorian, A. Samal, R. Krishnan, L. DeLucas, and D. Chattopadhyay. 2007. Crystal structure of vaccinia virus uracil-DNA glycosylase reveals dimeric assembly. BMC Struct. Biol. 7:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silverman, J. E. Y., M. Ciustea, A. M. Druck Shudofsky, F. Bender, R. H. Shoemaker, and R. P. Ricciardi. 2008. Identification of polymerase and processivity inhibitors of vaccinia DNA synthesis using a stepwise screening approach. Antiviral Res. 80:114-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stanitsa, E. S., L. Arps, and P. Traktman. 2006. Vaccinia virus uracil DNA glycosylase interacts with the A20 protein to form a heterodimeric processivity factor for the viral DNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 281:3439-3451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stuart, D. T., C. Upton, M. A. Higman, E. G. Niles, and G. McFadden. 1993. A poxvirus-encoded uracil DNA glycosylase is essential for virus viability. J. Virol. 67:2503-2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Traktman, P. 1996. Poxvirus DNA replication, p. 775-798. In M. L. DePamphilis (ed.), DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 44.Traktman, P., P. Sridhar, R. C. Condit, and B. E. Roberts. 1984. Transcriptional mapping of the DNA polymerase gene of vaccinia virus. J. Virol. 49:125-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Upton, C., D. Stuart, and G. McFadden. 1993. Identification of a poxvirus gene encoding a uracil DNA glycosylase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90:4518-4522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vagin, A., and A. Teplyakov. 1997. MOLREP: an automated program for molecular replacement. J. Appl. Cryst. 30:1022-1025. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Willer, D. O., M. J. Mann, W. Zhang, and D. H. Evans. 1999. Vaccinia virus DNA polymerase promotes DNA pairing and strand-transfer reactions. Virology 257:511-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Willer, D. O., X.-D. Yao, M. J. Mann, and D. H. Evans. 2000. In vitro concatemer formation catalyzed by vaccinia virus DNA polymerase. Virology 278:562-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang, W., and D. H. Evans. 1993. DNA strand exchange catalyzed by proteins from vaccinia virus-infected cells. J. Virol. 67:204-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]