Abstract

This study examines if differing types of victimization and coping strategies influence the type of social reactions experienced by 173 current victims of intimate partner violence (IPV). Results of path analyses showed that psychological and sexual IPV victimization were related to positive social reactions while physical, psychological, and sexual IPV victimization were related to negative social reactions. Indirect relationships between victimization and social reactions differed by types of coping strategies (social support, problem-solving, and avoidance) examined. Implications are discussed regarding the development of interventions with women’s support networks and the augmentation of services to help victims modify their coping strategies.

Keywords: Intimate Partner Violence, Disclosure, Social reactions

Among women who experience intimate partner violence (IPV), many choose to talk about their IPV victimization with or “disclose” it to people in their support networks. How recipients of those disclosures react to victims (i.e., social reactions) has been the topic of a fair amount of research in the last decade (Ahrens, 2006; Ahrens, Campbell, Ternier-Thames, Wasco, & Sefl, 2007; Campbell, Ahrens, Sefl, Wasco, & Barnes, 2001; Coker, Smith et al., 2002; Dunham & Senn, 2000; Goodkind, Gillum, Bybee, & Sullivan, 2003; Ullman, 1996b, 1996c, 2003; Ullman & Filipas, 2001, 2005; Ullman, Filipas, Townsend, & Starzynski, 2006; Ullman, Townsend, Filipas, & Starzynski, 2007; Yoshioka, Gilbert, El-Bassel, & Baig-Amin, 2003). The vast majority of this research has been on the disclosure of adulthood or childhood sexual assault and has focused on social reactions as predictors of victims’ health outcomes. Findings show that the type of social reaction women experience in response to their disclosure, namely positive or negative, is significantly related to women’s wellbeing. In particular, positive social reactions, such as telling the woman it is not her fault, accepting her account of what happened, or acting like the disclosure recipient cares about her, are associated with fewer mental health problems. Negative social reactions, such as blaming the woman for the victimization, changing the subject, or making a joke about experiences like hers, are associated with a greater number of mental health problems (Coker, Smith et al., 2002; Goodkind et al., 2003; Mitchell & Hodson, 1983; Ullman, 1996b, 1996c; Ullman & Filipas, 2001, 2005; Ullman et al., 2007).

Despite the fact that IPV, like sexual assault, is a highly prevalent form of victimization among women, there is a dearth of research on social reactions to disclosures of IPV (e.g., Coker, Smith et al., 2002; Dunham & Senn, 2000; Goodkind et al., 2003). Current research can be extended by studying (a) social reactions to women’s disclosures of IPV victimization and, (b) those factors that are potentially associated with social reactions since types of social reactions are related to both positive and negative mental health (Coker, Smith et al., 2002; Goodkind et al., 2003; Mitchell & Hodson, 1983; Ullman, 1996b, 1996c, 2003, 2007; Ullman & Filipas, 2001, 2005; Ullman et al., 2007). This study is guided by attribution and coping theories (Harrison & Esqueda, 2000; Lazarus, Lazarus, Campos, Tennen, & Tennen, 2006; Lerner & Miller, 1978; Overholser & Moll, 1990; Ross, 1977; Witte, Schroeder, & Lohr, 2006), which suggest that social reactions to women’s disclosures of IPV will be related to (a) the severity and type of IPV victimization women experience (i.e., current 1 physical, psychological, and sexual IPV), and (b) the coping strategies they employ to deal with their relationship conflict (i.e., social support-, problem solving-, and avoidance-coping).

Attribution theories. Patterns of positive and negative social reactions upon disclosures of IPV may be consistent with attribution theory, namely, the fundamental attribution error (Ross, 1977) and the just world hypothesis (Lerner & Miller, 1978). The fundamental attribution error posits that disclosure recipients tend to over-attribute causes of victimization to the woman and under-estimate both the responsibility of the aggressor and the dynamics of the abusive relationship. The just world hypothesis posits that “individuals have a need to believe that they live in a world where people generally get what they deserve” (Lerner & Miller, 1978, p. 1030) which protects their own belief system and/or allows them to feel less personally threatened. These theoretical foundations provide the framework for hypothesizing relationships between (a) current IPV victimization and social reactions and (b) coping strategies and social reactions.

Type and severity of victimization. According to the just world hypothesis, the more severe the consequences (of IPV) are to the victim the more negatively she is evaluated (Lerner & Miller, 1978). This hypothesis is consistently supported by data among sexual assault victims. For example, Ullman and colleagues found that greater severity of sexual assault was related to a greater number of negative social reactions upon disclosure (Ullman & Filipas, 2001; Ullman et al., 2007). The little data that exists on this hypothesis among women who experience IPV is inconclusive. In a sample of IPV victims exiting a domestic violence shelter, Goodkind et al. (2003) found that women who experienced a greater number of injuries reported more negative reactions and less emotional support. In contrast, however, those authors found no significant relationships between the frequency-severity of physical IPV (which was only weakly correlated with number of injuries) or the severity of psychological IPV and negative social reactions. The non-significant relationships between severity of IPV and social reactions may, in part, be related to the homogeneity of the sample; all study participants experienced IPV severe enough to seek services at a domestic violence shelter. An association between IPV severity and type of social reaction may exist in a community sample where this is greater heterogeneity regarding IPV severity and where the IPV is current.

Application of the just world hypothesis (Lerner & Miller, 1978) suggests a different relationship between psychological IPV and social reactions than the relationships proposed above between physical and sexual IPV and social reactions; severity of psychological IPV may be associated with positive social reactions. This hypothesis suggests that disclosure recipients will respond more favorably to victims if they can empathize with victims’ experiences. Disclosure recipients may empathize with victims’ experiences of psychological IPV because it is quite common among women in both their current and past relationships (Coker, Smith, McKeown, & King, 2000; Pico-Alfonso, 2005). Conceivably, disclosure recipients are able to imagine what it might be like to experience some form of this behavior (inclusive of verbal abuse such as being called names or sworn at) or perhaps have experienced it themselves, whereas they may never have experienced physical or sexual IPV. Results of Goodkind et al. (2003) are consistent with this hypothesis. They found that greater psychological IPV was correlated with positive social reactions such as receiving emotional support and being encouraged to seek services or resources to deal with the victimization. Results of Cromer and Freyd’s research (2007) also are consistent with this hypothesis such that people who had personally experienced trauma were more likely to see victims’ reports of abuse as credible. Since many disclosure recipients may be able to empathize with experiencing psychological IPV and therefore, will find it credible, greater severity of psychological IPV may be associated with a greater number of positive social reactions.

Coping theory and research. A pioneer of research on coping, Richard Lazarus (2006), focused on the interpersonal context of coping and its inextricable association with relational meaning stating, “coping should never be divorced from the persons who are engaged in it and the environmental context in which it takes place (p. 19).” Research on coping in the general population indicates that a woman’s typical use of coping strategies develops through an interactive or transactional process with her environment and is impacted by the verbal and nonverbal feedback she receives (Lazarus & Folkman, 1987; Lazarus et al., 2006; Moos & Holahan, 2003). Specific to coping among women who experience IPV, two reviews of the literature emphasize that the context of the violent intimate relationship is a unique one and coping must be examined within that context (Carlson, 1997; Waldrop & Resick, 2004). Thus, it stands to reason that the types of conflict-specific strategies that women employ to cope with their relationship problems are related to the type and severity of current IPV victimization they experience. Such types of coping strategies include problem solving coping such as, doing something to actively resolve the issue or problem, social support coping such as turning to others for comfort, advice, or simply for human contact, and avoidance coping such as, physical or psychological withdrawal (Amirkhan, 1990).

Coping and attribution theory (Lazarus et al., 2006; Lerner & Miller, 1978) suggest that types of coping strategies utilized by women who experience IPV will be related to types of social reactions experienced upon disclosures of IPV. For example, women who used approach coping strategies to deal with the victimization, such as problem solving and social support coping, would be perceived as doing something to resolve their problems and therefore, reacted to positively whereas women who used avoidance coping strategies would be seen as doing little to nothing to resolve their problems and therefore, be perceived and reacted to negatively. These examples are highlighted in findings of Mitchell and Hodson’s research (1983) which show that women who are struggling to cope with IPV victimization have the greatest severity of IPV yet have the fewest contacts with and receive the least support from people in their social support network.

Few studies have examined the relationship between coping and social reactions to disclosure. Among adults who disclosed sexual assault, Ullman (1996a) found that both greater approach and avoidance coping were related to greater negative social reactions to disclosure but were unrelated to positive social reactions. Specifically among female victims of IPV, Mitchell and Hodson (1983) found that greater approach coping was related to fewer negative social reactions, but was unrelated to positive social reactions, and avoidance coping was not related to either type of social reaction. The central limitations of Mitchell and Hodson’s study are that multivariate analyses were not conducted that take into account the severity or type of IPV, that the study population was a fairly homogenous sample of women from domestic violence shelters, and it was not an exclusive sample of women who were currently experiencing IPV.

Existing research on social reactions to disclosure is important because it clearly establishes an association between type of social reactions and the health of victimized women. However, this research is limited by (a) its primary focus on victims of adulthood and childhood sexual assault (b), its lack of focus on statistical predictors of types of social reactions and (c) minimal consideration of the context of current IPV. Therefore, further research is needed (a) to understand social reactions specific to disclosures of IPV, (b) to test the extent to which type of IPV and coping may be associated with the type of social reactions reported by women who experience IPV using multivariate analyses, and (c) to understand the aforementioned relationships in a community sample of women who are currently experiencing a range of levels of victimization and employ a variety of coping strategies. An investigation such as this one is critical to modifying social reactions experienced and ultimately, the sequelae of those reactions among victims.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to determine if the type and severity of current IPV victimization experienced by women (i.e., physical, psychological, and sexual IPV) and conflict-specific coping strategies they employed (i.e., social support-, problem solving-, and avoidance-coping) are associated with positive and negative social reactions upon disclosures of IPV. Hypotheses are; (a) greater severity of physical and sexual IPV and avoidance coping will be associated with a greater number of negative social reactions, and (b) greater severity of psychological IPV, social support- and problem solving-coping, will be associated with a greater number of positive social reactions.

METHODS

Sample

The initial sample consisted of 240 women recruited from an urban community in New England. Recruitment flyers, which invited women to participate “in a 2-hour interview about the relationship with your boyfriend or husband,” were posted in community establishments such as grocery stores, libraries, pizza and sandwich shops, convenience stores, primary care clinics, agencies such as the Departments of Adult Education and Employment, and nail and hair salons. The main inclusion criterion was that a woman had to have experienced at least one act of physical victimization in the past six months by her current male partner determined via a phone screen with items from the Conflict Tactics Scale-2 (CTS-2) (Straus, Hamby, & Warren, 2003). Other inclusion criteria were (a) a current relationship of at least six months duration, (b) with contact at least twice a week, (c) without spending more than two full weeks apart, (d) being 18-years-old or older, and (e) an annual household income no greater than $50,000 (determined a priori to methodologically control for the differential resources associated with greater income). Data from 28 participants were removed because although they met study criteria at the time of the screening, they failed to do so at the time of the interview. The final sample is composed of 212 women.

Of the 212 participants, 173 reported that they disclosed their IPV victimization to at least one person. Given that the purpose of this study is to examine social reactions to women’s disclosures, the following demographic information is based on and subsequent analyses were performed on this subsample of 173 women. The average age was 36.31 years (SD = 10.48). Most women were unemployed (66%) with a mean level of education of 12.14 years (SD = 1.55) and a median annual income of $9,600. The mean number of children was 2.30 (SD = 2.13). The average duration of the relationship was 76.35 months (SD = 75.03) with more than half married or cohabitating (60%). Sixty six percent of women were African American, 20% were white, 10% were Latina, and 5% identified as bi- or multiracial.

Procedures

The recruitment flyers, which advertised the “Women’s Relationship Study,” included tear-off sheets with the study phone number. Women who were interested called to determine if they were eligible to participate. Eligible women were invited to participate in a two-hour semi-structured interview. All interviews were administered face-to-face by female research associates using computer-assisted interviewing (NOVA Research Company, 2003); all interviewers were female master’s or doctoral level research associates who underwent over 20 hours of structured training including direct observation of and feedback regarding pilot interviews by the project’s Principle Investigator. Participants were debriefed, remunerated $50, and provided with a list of community resources such as those for domestic violence, employment, food, and benefits assistance, mental health therapy, and substance abuse treatment.

Measures

Social reactions to disclosure of IPV victimization

Social reactions to women’s disclosure of their IPV victimization were assessed using The Social Reactions Questionnaire, SRQ (Ullman, 2000). The SRQ was developed to measure reactions by others (i.e., disclosure recipients) when women disclosed sexual assault victimization. The measure was modified for this study to ascertain participants’ perceived reactions by others’ to participants’ disclosures of IPV victimization during their current intimate relationships. Instructions were revised to ask women to indicate how often they experienced each of the listed responses from disclosure recipients after women told the recipients about the IPV victimization in their current relationships. Response options were maintained from the SRQ and ranged from 0 (never) to 4 (always). Additionally, participants were asked the number of people to whom they disclosed their IPV victimization in their current relationship (M = 3.40, SD = 3.14).

A principal components analysis of the 48 SRQ items was conducted specific to this sample. The components were assumed to be orthogonal and therefore, Varimax rotation was used. The analyses produced two components, positive social reactions and negative social reactions. The analysis suggested 17 items for positive social reactions to disclosure and 22 items for negative social reactions to disclosure; 9 items did not have a factor loading equal to or greater than .40 and therefore, did not load on either scale. Based on reliability analyses to improve the internal consistency of the scales, four items were removed from the positive social reactions scale and no items were removed from the negative social reactions scale. Examples of positive reaction items include; “Saw your side of things and did not make judgments; helped you get information of any kind about coping with the experience; and reassured you that you are a good person.” Examples of negative reaction items include; “Told you that you were to blame or shameful because of this experience; told you that you could have done more to prevent this experience from occurring; and made a joke or sarcastic comment about this type of experience.” To create a total score for each scale, items were summed for their respective scales. The reliability coefficient for the 13-item positive social reactions scale was α = .88 and for the 22-item negative social reactions scale was α = .89. 2

Intimate partner violence

Women’s physical, psychological, and sexual IPV victimization, as well as negotiation and injury, were measured by the 78-item CTS-2 (Straus et al., 2003). To gain more specific information about psychological and sexual IPV victimization, these constructs also were measured by the Psychological Maltreatment of Women Inventory, PMWI, (Tolman, 1989) and the Sexual Experiences Survey, SES (Koss & Oros, 1982) respectively. For the purposes of these analyses, the CTS-2 physical IPV, the PMWI psychological IPV, and the SES sexual IPV victimization scores were used. A referent time period of six months was used to assess the woman’s current IPV-victimization by her current partner via the woman’s self-report.

The response scale for the physical IPV items includes the following seven response options: never, once, twice, 3–5 times, 6–10 times, 10–20 times, to more than 20 times in the past six months. Response categories presented as ranges were recoded according to the procedures identified by Straus, Hamby and Warren (2003) (i.e., 3 – 5 = 4; 6 – 10 = 8; 10 – 20 = 15; > 20 = 25). The physical IPV victimization score was created by summing the 12 items for that scale; α = .90. Psychological IPV victimization was measured by summing the 48 items from the PMWI (Tolman, 1989) with response options ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very frequently), α = .96. Sexual IPV victimization was assessed using the same response options, recoding, and variable creation scheme as the CTS-2 with a resulting α = .89. Given that the SES (Koss & Oros, 1982) has been used largely with college populations and requires a fairly high reading level, the measure was revised to improve comprehension among study participants. One hundred percent of the women experienced physical IPV and psychological IPV and 60% experienced some form of sexual IPV. 3

Coping with relationship conflict

Strategies for coping with conflict in the current intimate relationship were assessed with the Coping Strategy Indicator, CSI (Amirkhan, 1990). The CSI is a 33-item measure that assesses problem solving coping (e.g., brainstormed all possible solutions before deciding what to do), social support coping (e.g., confided fears and worries to a friend or a relative), and avoidance coping (e.g., slept more than usual). Each subscale is composed of 11 items that are summed to create a subscale score. In order to orient participants to coping strategies they used to deal with recent conflict in their current intimate relationships, they were instructed to describe a conflict with their intimate partners in the past six months that was important to them and caused them to worry. Participants were then asked to rate the extent to which they used each of the 33 strategies with respect to that conflict: 1 (not at all), 2 (a little), 3 (a lot). Specific to the present study, the reliability coefficients were: social support coping, α = .92; problem solving coping, α = .82; and avoidance coping, α = .75.

Data Analyses

Variables were assessed for assumptions of normality. The negative social reactions to disclosure, number of people to whom women disclosed, and physical and sexual IPV victimization variables had mild to modest degrees of positive skew. As recommended by Tabachnick and Fidel (2007) a square root transformation was performed on negative social reactions, a log10 transformation was performed on physical IPV victimization, and categorical variables were created to measure the number of people to whom women disclosed (1 = one person, 2 = two people, 3 = three or four people, and 4 = five or more people) and sexual IPV victimization (0= no occurrences of sexual victimization, 1 = one or more occurrences of sexual victimization), producing a normal distribution for each. Given that computer-assisted interviews were administered face-to-face by research associates, the amount of missing data was negligible (i.e., less than 3%). AMOS 6.0 (SPSS Inc, 2005), which uses Full Information Maximum Likelihood to deal with missing data, was employed.

Two separate path models analyzed relationships among women’s physical, psychological, and sexual IPV victimization, the number of people to whom women disclosed their victimization, and conflict-specific coping strategies, to women’s reports of (1) positive and (2) negative social reactions upon disclosure of IPV. The AMOS 6.0 statistical program (SPSS Inc, 2005) was utilized to analyze the path models, obtain maximum-likelihood estimates of model parameters, and provide goodness of fit indices. Path model results were interpreted according to Byrne (2001). A model that provides a good fit to the data generally has a non-significant model chi-square, a root mean square of approximation (RMSEA) value of less than .05 (≤ .08 is adequate), with a p test for closeness of fit for RMSEA of .50 or greater, and a chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio (χ2/df) of less than 3. Individual path coefficients, which can be interpreted similarly to regression coefficients (β), are considered significant at the p < .05 level.

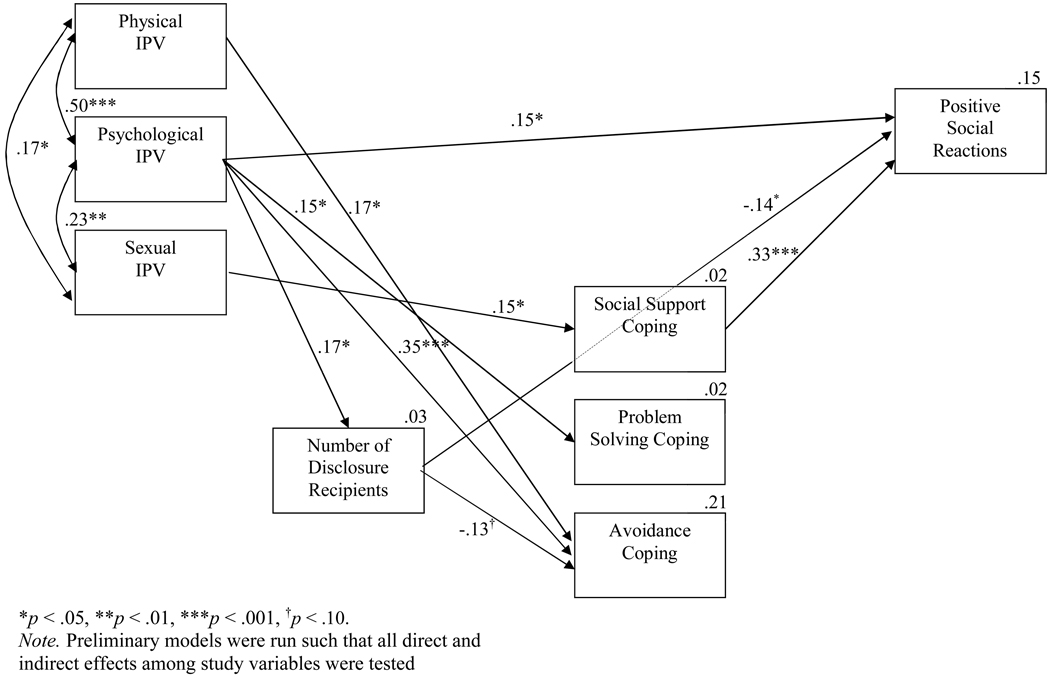

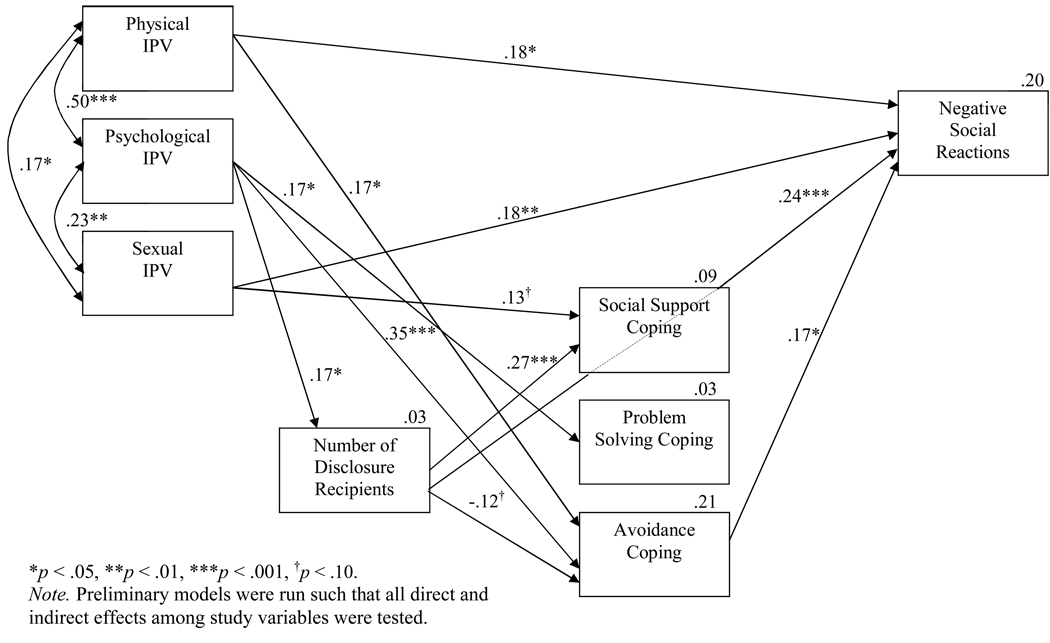

The final models are presented in Figures 1 and 2. Given the lack of consistent evidence in the literature, preliminary models were analyzed such that all direct and indirect effects among study variables were tested. The final models were obtained by maintaining parameters (i.e., β) with p < .10 while maintaining good to strong model fit, as well as achieving the minimum recommendations for sample size to parameters to be estimated of at least 5:1 (Byrne, 2001).

Figure 1.

Positive social reactions to women upon disclosure of IPV victimization.

Figure 2.

Negative social reactions to women upon disclosure of IPV victimization.

RESULTS

Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations of Study Variables

Correlations, means, and standard deviations of study variables are included in Table 1. No IPV variables were significantly correlated with positive social reactions, although the relationship of psychological IPV to positive social reactions approached significance (r = .14, p < .10). All three IPV variables were related to negative social reactions (physical IPV r = .27, p < .01; psychological IPV r = .30 p < .01; and sexual IPV r =.28, p < .01). Positive and negative social reactions were negatively correlated with each other (r = − .16, p < .05). Both social support coping and problem solving coping were associated with positive social reactions (r = .30, p < .001 and r = .23, p < .01, respectively) while only avoidance coping was associated with negative social reactions (r = .25, p < .01). The relationship of social support coping to negative social reactions approached significance (r = .13, p < .10). Also noteworthy is there was not a great deal of variability among the means for the three types of coping strategies assessed which suggests that women’s use of strategies was not limited to one domain but rather spanned across the three coping domains.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations of Study Variables (N=173)

| Variable | M (Mode) |

SD | Range | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Positive social reactions | 31.29 | 9.41 | 8 – 52 | -- | |||||||

| 2. Negative social reactions | 16.94 | 12.00 | 0 – 57 | − .16* | -- | ||||||

| 3. Physical IPV | 37.54 | 48.44 | 1 – 209 | .11 | .27** | -- | |||||

| 4. Psychological IPV | 130.34 | 34.49 | 63 – 223 | .14⊥ | .30** | .49** | -- | ||||

| 5. Sexual IPV | 10.42 | 25.89 | 0 – 173 | −.04 | .28** | .17* | .23** | -- | |||

| 6. Number of disclosure recipients |

3.61 (2) |

4.91 | 1 – 4 | − .02 | .26** | .02 | .17* | .09 | -- | ||

| 7. Social support coping | 23.05 | 5.76 | 11 – 33 | .30** | .13⊥ | .01 | .05 | .14⊥ | .30** | -- | |

| 8. Problem solving coping | 26.83 | 4.18 | 16 – 33 | .23** | .01 | − .02 | .16* | −.03 | .08 | .33** | -- |

| 9. Avoidance coping | 24.03 | 4.32 | 13 – 33 | .09 | .25** | .32** | .41** | .18* | − .05 | .09 | .20** |

Note: Means and standard deviations are for untransformed scores. Correlations are based on transformed scores.

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01

Path Analyses

Positive Social Reactions to Disclosure of IPV

The final path model depicted in Figure 1 tested the direct and indirect relationships of the following variables to positive social reactions to disclosures of IPV: physical, psychological, and sexual IPV victimization; number of people to whom women disclosed their IPV victimization; social support coping, problem solving coping, and avoidance coping. The model provided adequate fit to the data, with a Chi-square, χ2 (13, n=173) = 27.51, p = .01, a χ2/df = 2.12, and an RMSEA = .08, a confidence interval of .038 to .123, and a p for test of close fit of .107.

Psychological and sexual IPV, but not physical IPV, were related to positive social reactions to disclosures. As hypothesized, a greater level of psychological IPV was directly associated with more reports of positive social reactions (β = .15, p < .05). Psychological IPV also was indirectly related to positive social reactions via the number of people to whom women disclosed. Greater levels of psychological IPV were positively related to the number of people to whom women disclosed (β = .17, p < .05) which in turn was significantly related to fewer positive social reactions (β = −.14, p < .05). Sexual IPV was indirectly related to positive social reactions such that being a victim of sexual IPV was related to greater use of social support coping strategies (β = .15, p < .05) which, in turn, was significantly and strongly related to a greater number of positive social reactions (β = .33, p < .001).

Negative Social Reactions to Disclosure of IPV

The final path model depicted in Figure 2 tested the direct and indirect relationships of the following variables to negative social reactions to disclosures of IPV: physical, psychological, and sexual IPV victimization; number of people to whom women disclosed their IPV victimization; social support coping, problem solving coping, and avoidance coping. The model provided an excellent fit to the data, with a non-significant Chi-square, χ2 (df 11, n=173) = 10.12, p = .52, a χ2/df = .92, and an RMSEA = .00, a confidence interval of .00 to .08, and a p for test of close fit of .81.

Physical, psychological, and sexual IPV were related to negative social reactions. Consistent with hypotheses, physical IPV was both directly and indirectly related to negative social reactions. The more physical IPV a woman experienced the greater the number of negative social reactions she reported (β = .18, p < .05). Additionally, an indirect relationship emerged via avoidance coping; greater levels of physical IPV were related to greater use of avoidance coping strategies (β = .17, p < .05) which in turn were related to a greater number of negative social reactions (β = .17, p < .05). Also consistent with hypotheses, being a victim of sexual IPV was related to a greater number of negative social reactions, (β = .18, p < .01). Psychological IPV was indirectly related to negative social reactions via avoidance coping; the greater a woman’s experiences of psychological IPV the more she used avoidance coping strategies (β = .35, p < .001), which in turn were related to a greater number of negative social reactions (β = .17, p < .05). No mediating effects were observed. Also noteworthy was that the more people to whom women disclosed their IPV victimization the more negative social reactions women reported (β = .27, p < .001).

DISCUSSION

Findings are consistent with attribution and coping theories such that, among a community sample of women who experienced current IPV, the type and severity of IPV victimization they experienced, as well as the conflict-specific coping strategies they employed were differentially related to positive and negative social reactions upon disclosures of IPV. This study extends previous work and contributes uniquely to the literature on IPV victimization in a number of ways. First, this examination focused on the severity of specific types of IPV, namely, physical, psychological, and sexual. Second, coping was assessed specifically regarding relationship conflict – a methodology strongly encouraged by researchers of coping among IPV victims but rarely employed in the conduct of research (Carlson, 1997; Waldrop & Resick, 2004). Third, this investigation was conducted with women from the community who were currently experiencing IPV victimization. This sampling methodology permits the generalizability of findings to women with similar demographic characteristics who experience a range of victimization. If replicated, findings have the potential to inform the development of interventions to provide support to victims.

Interesting findings emerged regarding positive social reactions. The finding that psychological IPV was positively associated with positive social reactions aligns with past research on IPV victims (Goodkind et al., 2003). As is suggested by the just world hypothesis (Lerner & Miller, 1978), disclosure recipients may respond more positively to women who experience high levels of psychological IPV because recipients may be more empathetic regarding how emotionally painful psychological IPV can be. Or, perhaps disclosure recipients believe that psychological IPV is more amenable to intervention than other types of IPV. Finally, the strong association between social support coping and positive social reactions is promising given that coping has been shown to be modifiable with intervention (Carlson, 1997).

Findings regarding the relationship between women’s disclosures of IPV victimization and negative social reactions suggest that better understanding may be gained with the application of attribution theories (Lerner & Miller, 1978; Ross, 1977). Results regarding the direct and positive relationships of IPV victimization to negative social reactions to disclosures are similar to those found in studies of sexual assault victims (Ullman & Filipas, 2001; Ullman et al., 2007) and may exist for several reasons. As hypothesized, there may be some element of personal attribution for the victimization such that the more severe a woman’s victimization, the more likely disclosure recipients are to attribute some of the cause to the victim and therefore, react negatively. Or perhaps like the findings of Goodkind et al.’s (2003) study, the greater the frequency and severity of physical and sexual IPV to the victim the more likely disclosure recipients are to fear for their own safety and therefore, react negatively. Additional speculation is that recipients may believe that physical and sexual IPV victimization, unlike psychological IPV victimization, are less amenable to change and therefore, react negatively to women who remain involved in relationships where they are perceived as doing little to protect themselves; all women in this study were currently experiencing IPV.

In addition to direct relationships of victimization to positive and negative social reactions, indirect relationships emerged via coping. Again, these findings are promising given that coping strategies can be targeted and modified through intervention (Carlson, 1997). In the positive social reactions model, women who experienced sexual IPV in their current relationship tended to use more social support coping strategies to deal with relationship conflict, which was associated with a greater number of positive social reactions. In other words, it was not the sexual IPV victimization itself, but rather the sexual IPV in relation to how women cope with conflict with their partners by relying on friends, family, and professionals that was associated with positive social reactions. In the negative social reactions model, the more physical and psychological IPV a woman experienced the more avoidance coping strategies she employed to deal with the problems in her relationship, which in turn, were related to more negative social reactions. Women who experience IPV that is more dangerous or potentially injurious may use avoidance coping strategies because it provides them with an additional level of safety (e.g., increased physical safety and/or a reduced level of anxiety) not to talk with about it other people or not to think about it themselves. Consequently, the people to whom the IPV ultimately is disclosed evaluate these coping strategies negatively because they perceive women as avoiding the problems in their relationships or “not doing anything about it,” which is related to negative social reactions. As previously stated, this is in line with extant literature that shows that female victims of IPV often exhaust their social networks in the context of trying to cope with the victimization (Mitchell & Hodson, 1983). Findings of indirect effects via coping strategies contribute to the growing literature regarding IPV and the benefits of social support coping. It is important to note that significant bivariate correlations were observed between problem solving coping and positive social reactions, however, this relationship was not maintained as hypothesized in the multivariate model. Perhaps with other forms of coping analyzed simultaneously in the path models, problem solving coping does not contribute uniquely enough to the type of reactions experienced. Or, the lack of significant model relationships to either type of social reactions may indicate that disclosure recipients do not value problem solving coping when it is employed to deal with IPV.

Additional interesting findings emerged regarding the relationship of the number of people to whom women disclosed and both positive and negative social reactions. Women who disclosed their IPV victimization to a greater number of people experienced fewer positive social reactions and more negative social reactions than women who disclosed to fewer people. This relationship is suggested by findings of Carlson, McNutt, Choi, and Rose (2002). Possibly, when disclosure recipients are supportive and react to women positively, women no longer need to seek support from others. An alternative explanation is that some women may not use discretion when disclosing their IPV victimization and thus, tell a large number of people, many of whom are less focused on the women’s wellbeing and therefore, respond negatively. Of note is that only psychological IPV, and not physical or sexual IPV, was related to the number of people to whom women disclosed. This finding suggests that psychological IPV (a) may be more distressing than the literature to date has acknowledged, (b) that women who experience greater levels of psychological IPV disclose the victimization in their relationship to more people in anticipation of receiving positive reactions, or (c) that since psychological IPV is more common and possibly perceived as less severe, it may be easier to disclose to a greater number of people. Also, although not a focus of the current study, these findings may suggest that women’s motivations for disclosing, or their expectations of reactions upon disclosure, may influence to whom they disclose and the content of their disclosures. Future research should explore this possibility especially as it has implications for the development of interventions with this population.

Limitations

Study limitations worthy of note include the cross sectional nature of the study, the exclusion of demographic and other variables from the analyses, the measure of social reactions to disclosure as based on participant (i.e., victim) self-report, lack of information regarding the exact content of the disclosures, and the relative homogeneity of the sample regarding socioeconomic status and racial/ethnic diversity. Because the data is cross sectional, directionality cannot be determined and therefore, equivalent path models based on different theoretical foundations might be supported by this data (Kline, 2005). For example, (a) it is plausible that there is a reciprocal or transactional relationship between coping and social reactions such that negative social reactions contribute to a greater level of avoidance coping strategies (Ullman et al., 2007) or (b) that negative social reactions could contribute to the number of people to whom women disclosed whereby when women disclose their IPV victimization and experience negative social reactions they tell more people in search of a positive reactions. Longitudinal studies are needed to disentangle the relationships between IPV victimization, coping, disclosure, and social reactions to disclosure. The sample size did not allow for the inclusion of demographic or other variables that may provide additional explanatory power. Larger samples would allow for the inclusion of variables such as race/ethnicity, marital status, and level of education which have been found to relate to type of social reaction (Cash, 2005; Coker, Davis et al., 2002; Dunham & Senn, 2000; Swanberg & Logan, 2005; Yoshioka et al., 2003), or variables such as symptoms of depression or posttraumatic stress (Ullman & Filipas, 2001; Ullman et al., 2006). Notably, the positive social reactions model did not provide as strong of a fit to the data as the negative social reactions model. Further research should examine additional factors that may contribute to positive social reactions such as disclosure recipients’ knowledge about IPV or the victims’ subjective experience and presentation of her IPV victimization.

A final limitation worthy of note is that social reactions to disclosure were measured as those perceived and reported by the victim. It is possible that findings might differ if additional measures of social reactions were obtained. For example, women who experienced severe physical IPV received more negative reactions when they disclosed their IPV victimization to others or, perhaps as a function of women’s extreme victimization, they perceived that disclosure recipients reacted negatively when the actually did not. Nonetheless, women’s perceptions are extremely important since it is likely that their perceptions, and not necessarily the actual responses, are associated with positive and negative health outcomes – parallel to the field of social support research which differentiates a focus on perceived and actual social support (Yap & Devilly, 2004) which also has been documented among female victims of crime (Andrews, Brewin, & Rose, 2003).

Future directions for research and implications

The findings of this study inform directions for future research and if replicated, the development of intervention programs targeted at female victims of IPV and the communities in which they live. Benefits could be gained by conducting investigations in which recipients of disclosures of IPV victimization are directly interviewed to learn more about factors that contribute to the type of reactions the recipients exhibit (e.g., positive and negative attributions, assignment of blame to victim or abuser, perception of the abuser as amenable to change, recipients own personal histories of IPV and disclosure, understanding of dynamics of IPV). Equally valuable research to pursue is the examination of positive and negative social reactions according to the relationships of the disclosure recipients to the victims (e.g., professional vs. personal relationship, medical vs. mental health professional, male or female etc.), the quality of the social support networks of women, women’s motivations or expectations for disclosing IPV, and the content of women’s disclosures. Results of these studies would provide a better understanding of which groups of recipients could benefit from targeted outreach efforts about effective ways to respond to disclosures of IPV victimization. Finally, longitudinal research is needed in order to disentangle the complex inter-relationships among coping and victimization, as well as coping and social reactions to disclosures to establish the temporal relationships or the transactional nature of the relationships.

The findings of this investigation document that community women who are currently experiencing IPV report both positive and negative social reactions when they disclose their IPV victimization and that the type and severity of IPV victimization they have experienced as well as the coping strategies they employed play a role in the types of social reactions experienced. Women have little if any control over the type and severity of IPV victimization they experience. They do have somewhat more control over the coping strategies they employ. The development of more adaptive coping strategies is modifiable with intervention (Carlson, 1997). Therefore, the enhancement of social support coping strategies (the strongest relationships demonstrated in the analyses) and the reduction of avoidance coping strategies show promise to increase positive social reactions and decrease negative ones. With the aforementioned stated, it is important to be clear that the onus for change should not lie solely with the victim.

Results of this and similar studies could have direct applicability to service delivery by clarifying the associations between certain types of IPV victimization and social reactions to disclosures of IPV victimization. Armed with the necessary empirical evidence, providers can anticipate and plan for the reactions women might experience based on the severity and types of IPV victimization in their relationships[0] and the coping strategies they employ. Providers can work with victims to modify coping strategies which would provide benefits to the women that may extend beyond issues related to reactions to disclosure. For example, reducing avoidance coping and/or improving/promoting social support coping can also prove useful to reducing mental health and substance use problems (Constantino, Kim, & Crane, 2005; Koopman, Wanat, Whitsell, Westrup, & Matano, 2003; Snow, Swan, Raghavan, Connell, & Klein, 2003). Furthermore, findings suggest that public awareness campaigns and interventions with members of women’s social support networks could benefit from directly targeting negative social reactions and victim-blaming attitudes by teaching people the most effective ways to react to women when they disclose the IPV victimization they have experienced. Better understanding of and more positive reactions to victims’ disclosures of IPV can eventually create an increased sense of safety among victims in bringing to light their IPV victimization to help reduce its negative sequelae as well as its incidence and prevalence in society.

Acknowledgments

The research described here was supported, in part, by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R03 DA17668, K23 DA019561, T32 DA019426).

Biographies

Tami P. Sullivan, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor in the Division of Prevention and Community Research and Director, Family Violence Research and Programs, Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine. Dr. Sullivan’s program of research focuses on understanding (a) precursors, correlates, and outcomes of women’s victimization and their use of aggression in intimate relationships, and (b) the co-occurrence of IPV, posttraumatic stress, and substance use with specific attention to daily processes and intensive longitudinal data. She is particularly interested in risk and protective factor research that informs the development of interventions to be implemented in community settings.

Jennifer A. Schroeder, Ph.D., is an Associate Director for the Connecticut Center for Effective Practice at the Child Health and Development Institute of Connecticut. She provides research, evaluation, quality assurance, and consultation to local and state organizations to help improve behavioral health services and systems of care to children and youth. Currently she coordinates the SAMHSA-funded Connecticut Wraparound Initiative working to improve the system of care in two communities to support comprehensive implementation of Wraparound for youth and families. Other projects include the comprehensive statewide Multisystemic (MST) evaluation project and evaluation of the Emergency Mobile Psychiatric Services (EMPS) program in Connecticut.

Desreen N. Dudley, Psy.D. is a clinical psychologist in the Department of Psychiatry at The Consultation Center, Yale University School of Medicine. Dr. Dudley’s research and clinical interests include intimate partner violence, women’s sexual and physical abuse, risk behavior intervention and prevention of victimization and perpetration of violence. Dr. Dudley has also contributed to the development of a treatment manual for individuals with a history of childhood sexual abuse and HIV/AIDS.

Julia M. Dixon, M.P.H, is a Senior Research Associate at New England Research Institutes in Watertown, MA. She holds a Master’s degree in Public Health from Yale University and a Bachelor of Science in Neuroscience from the College of William and Mary. Her current research interests include racial and ethnic disparities in bone health and the relationship between endothelial function and cardiovascular risk.

Footnotes

A discussion of the very important issues relevant to current victimization and the process of staying or leaving an abusive relationship is beyond the scope of this manuscript; interested readers are referred to Bell, Goodman, and Dutton, (2007) Anderson and Saunders (2003), Tolman and Rosen, (2001) and Rhodes and McKenzie (1998) for information on this topic.

Readers interested in the final positive and negative social reaction scale items may contact the corresponding author for further information.

Women’s reports of social reactions to their disclosures were assessed over the duration of the relationship while IPV victimization was assessed over both the duration of the relationship and the past six months. The physical, psychological, and sexual IPV scores that assess experiences over the duration of the relationship provide less information than the corresponding six-month scores since the relationship-duration scores can only be created by summing the different types of IPV tactics experienced by the woman rather than the frequency of the IPV victimization she experienced. The six-month scores provide more useful information since they are a sum of the frequency of victimization. Given that the six-month victimization scores are more meaningful to inform service delivery and the development of intervention efforts, analyses were undertaken to determine if six-month scores were reflective of relationship-duration scores; if this was the case, use of the six-month scores in the analyses would be justified. Strong bivariate correlations show that physical, psychological, and sexual IPV six-month scores are reflective of the respective relationship-duration scores (r = .60**, .42**, and .52** for physical, psychological and sexual abuse, respectively). Therefore, the six-month scores, as previously described in the methods section, were used as proxy indicators in the descriptive analysis, correlations, and path models.

REFERENCES

- Ahrens CE. Being silenced: The impact of negative social reactions on the disclosure of rape. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;38(3–4):263–274. doi: 10.1007/s10464-006-9069-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens CE, Campbell R, Ternier-Thames N, Wasco SM, Sefl T. Deciding whom to tell: Expectations and outcomes of rape survivors' first disclosures. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2007;31(1):38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Amirkhan JH. A factor analytically derived measure of coping: The Coping Strategy Indicator. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1990;59(5):1066–1074. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DK, Saunders DG. Leaving An Abusive Partner: An Empirical Review of Predictors, the Process of Leaving, and Psychological Well-Being. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2003;4(2):163–191. doi: 10.1177/1524838002250769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews B, Brewin CR, Rose S. Gender, social support, and PTSD in victims of violent crime. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16(4):421–427. doi: 10.1023/A:1024478305142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell M, Goodman L, Dutton M. The Dynamics of Staying and Leaving: Implications for Battered Women's Emotional Well-Being and Experiences of Violence at the End of a Year. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22(6):413–428. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R, Ahrens CE, Sefl T, Wasco SM, Barnes HE. Social reactions to rape victims: Healing and hurtful effects on psychological and physical health outcomes. Violence and Victims. 2001;16(3):287–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson BE. A stress and coping approach to intervention with abused women. Family Relations: Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies. 1997;46(3):291–298. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson BE, McNutt L-A, Choi DY, Rose IM. Intimate partner abuse and mental health: The role of social support and other protective factors. Violence Against Women. 2002;8(6):720–745. [Google Scholar]

- Cash P. Commentary. Clinical Nursing Research. 2005 Aug;Vol 14(3):234–237. [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I, Desai S, Sanderson M, Brandt HM, et al. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;23(4):260–268. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Smith PH, McKeown RE, King MJ. Frequency and correlates of intimate partner violence by type: physical, sexual, and psychological battering.[see comment] American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90(4):553–559. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.4.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Smith PH, Thompson MP, McKeown RE, Bethea L, Davis KE. Social support protects against the negative effects of partner violence on mental health. Journal of Women's Health & Gender-Based Medicine. 2002;11(5):465–476. doi: 10.1089/15246090260137644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino R, Kim Y, Crane PA. Effects of a social support intervention on health outcomes in residents of a domestic violence shelter: A pilot study. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2005;26(6):575–590. doi: 10.1080/01612840590959416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cromer LD, Freyd JJ. What influences believing child sexual abuse disclosures? The roles of depicted memory persistence, participant gender, trauma history, and sexism. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2007;31(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Dunham K, Senn CY. Minimizing negative experiences: Women's disclosure of partner abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2000;15(3):251–261. [Google Scholar]

- Goodkind JR, Gillum TL, Bybee DI, Sullivan CM. The impact of family and friends' reactions on the well-being of women with abusive partners. Violence Against Women. 2003;9(3):347–373. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison LA, Esqueda CW. Effects of race and victim drinking on domestic violence attributions. Sex Roles. 2000;42(11/12):1043–1057. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and Practices of Structural Equation Modeling. Second ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Koopman C, Wanat SF, Whitsell S, Westrup D, Matano RA. Relationships of Alcohol Use, Stress, Avoidance Coping, and Other Factors With Mental Health in a Highly Educated Workforce. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2003;17(4):259–268. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-17.4.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Oros CJ. Sexual Experiences Survey: A research instrument investigating sexual aggression and victimization. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1982;50(3):455–457. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping. European Journal of Personality. 1987;1(3, Spec Issue):141–169. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Lazarus B, Campos JJ, Tennen R, Tennen H. Emotions and Interpersonal Relationships: Toward a Person-Centered Conceptualization of Emotions and Coping. Journal of Personality. 2006;74(1):9–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner MJ, Miller DT. Just world research and the attribution process: Looking back and ahead. Psychological Bulletin. 1978;85(5):1030–1051. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell RE, Hodson CA. Coping with domestic violence: Social support and psychological health among battered women. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1983;11(6):629–654. doi: 10.1007/BF00896600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Holahan CJ. Dispositional and Contextual Perspectives on Coping: Toward an Integrative Framework. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2003;59(12):1387–1403. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOVA Research Company. Questionnaire Development System TM User's Manual. Bethesda, MD: NOVA Research Company; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Overholser JC, Moll SH. Who's to blame: Attributions regarding causality in spouse abuse. Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 1990;8(2):107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Pico-Alfonso MA. Psychological intimate partner violence: the major predictor of posttraumatic stress disorder in abused women. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2005;29(1):181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes NR, McKenzie EB. Why do battered women stay?: Three decades of research. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 1998;3(4):391–406. [Google Scholar]

- Ross L. The intuitive psychologist and his shortcomings: Distortions in the attribution process. In: Berkowitz L, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 10. New York: Academic Press; 1977. pp. 173–220. [Google Scholar]

- Snow DL, Swan SC, Raghavan C, Connell CM, Klein I. The relationship of work stressors, coping and social support to psychological symptoms among female secretarial employees. Work & Stress. 2003;17(3):241–263. [Google Scholar]

- SPSS Inc. AMOS 6.0 (Version 6.0) Spring House, PA: AMOS Development Corporation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Warren WL. The Conflict Tactics Scales Handbook. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Swanberg JE, Logan T. Domestic Violence and Employment: A Qualitative Study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2005;10(1):3–17. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.10.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 5th ed. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tolman RM. The development of a measure of psychological maltreatment of women by their male partners. Violence and Victims. 1989;4(3):159–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman RM, Rosen D. Domestic violence in the lives of women receiving welfare. Violence Against Women. 2001;7(2):141–158. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE. Correlates and consequences of adult sexual assault disclosure. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1996a;11(4):554–571. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE. Do social reactions to sexual assault victims vary by support provider? Violence and Victims. 1996b;11(2):143–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE. Social reactions, coping strategies, and self-blame attributions in adjustment to sexual assault. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1996c;20(4):505–526. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE. Psychometric characteristics of the Social Reactions Questionnaire: A measure of reactions to sexual assault victims. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2000;24(3):257–271. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE. Social reactions to child sexual abuse disclosures: a critical review. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2003;12(1):89–121. doi: 10.1300/J070v12n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE. Relationship to Perpetrator, Disclosure, Social Reactions, and PTSD Symptoms in Child Sexual Abuse Survivors. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2007;16(1):19–36. doi: 10.1300/J070v16n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Filipas HH. Predictors of PTSD symptom severity and social reactions in sexual assault victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2001;14(2):369–389. doi: 10.1023/A:1011125220522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Filipas HH. Gender differences in social reactions to abuse disclosures, post-abuse coping, and PTSD of child sexual abuse survivors. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29(7):767–782. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Filipas HH, Townsend SM, Starzynski LL. Correlates of comorbid PTSD and drinking problems among sexual assault survivors. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31(1):128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Townsend SM, Filipas HH, Starzynski LL. Structural models of the relations of assault severity, social support, avoidance coping, self-blame, and PTSD among sexual assault survivors. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2007;31(1):23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop AE, Resick PA. Coping among adult female victims of domestic violence. Journal of Family Violence. 2004;19(5):291–302. [Google Scholar]

- Witte TH, Schroeder DA, Lohr JM. Blame for intimate partner violence: An attributional analysis. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology. 2006;25(6):647–667. [Google Scholar]

- Yap MBH, Devilly GJ. The role of perceived social support in crime victimization. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka MR, Gilbert L, El-Bassel N, Baig-Amin M. Social Support and Disclosure of Abuse: Comparing South Asian, African American, and Hispanic Battered Women. Journal of Family Violence. 2003;18(3):171–180. [Google Scholar]