Abstract

Background

The California Department of Public Health (CDPH), California Tobacco Control Program (CTCP) is one of the longest-running comprehensive tobacco control programmes in the USA, resulting from a 1988 ballot initiative that added a 25-cent tax on each pack of cigarettes and a proportional tax increase on other tobacco products. This programme used a social norm change approach to reduce tobacco use.

Methods

The operation, structure, evolution, programme dissemination and results are reviewed.

Results

The sustained programme implementation has reduced adult per capita cigarette consumption by over 60% and adult smoking prevalence by 35%, from 22.7% in 1988 to 13.8% in 2007. From 1988 to 2004, lung and bronchus cancer rates in California declined at nearly four times the rate of decline seen in the rest of the USA and the programme is associated with an $86 billion savings in healthcare costs. Youth smoking rates among 12–17 years olds are the second lowest in the nation.

Conclusions

The social norm change approach is effective at reducing tobacco consumption, adult smoking and youth uptake. This approach resulted in declines in tobacco-related diseases and is associated with savings in healthcare expenditures. In considering CTCP's effectiveness, the takeaway message is that it should be viewed as a unified programme rather than a collection of independent interventions. The programme was designed and implemented as one where the parts complement and reinforce each other. Its effectiveness is dependent on its comprehensive strategy rather than any one part of the intervention.

Keywords: Tobacco control, comprehensive tobacco control programme, California, advocacy, public policy

Background

The California Tobacco Control Program (CTCP) is one of the longest-running comprehensive tobacco control programmes in the USA, resulting from a November 1988 ballot initiative known as Proposition 99, which added a 25-cent tax per cigarette pack and a proportional tax increase to other tobacco products beginning 1 January 1989.1 2 The tax was earmarked for public health programmes to prevent and reduce tobacco use, provide healthcare services, fund tobacco-related research and protect environmental resources.

Programme-enabling legislation for the health education component was both visionary and prescriptive.2 It set an ambitious goal of achieving a 75% reduction in tobacco consumption within 10 years, mandated the application of the most current research findings and required programmes to demonstrate an understanding of the role that community norms have in influencing individual tobacco use.3 It prescribed aggressive timelines and detailed requirements for local health departments, community input, evaluation and state oversight. Collectively, these mandates provided accountability for timely implementation and measurable results, justification for population-based strategies, flexibility for the programme to evolve and a foundation from which to defend the programme against political interference.

Two state health department leaders were instrumental in CTCP's early success. These were Doctors Kenneth Kizer, Director, and Dileep G Bal, Chief, Cancer Control Branch. Both men exhibited risk-taking leadership styles that galvanised internal and external resources. Dr Kizer established an executive-level workgroup which re-engineered basic state business processes to rapidly launch Proposition 99-funded programmes. Dr Bal capitalised on his network of federal government and university relationships to craft key programme components and quickly assembled a team adept at working with stakeholders who were able to meet deadlines.

The risk-taking nature of Dr Kizer was epitomised by the 10 April 1990 media campaign launch which was bold and immediately controversial. It challenged the tobacco industry directly and defined the campaign to be as much about non-smokers as about smokers. Later that month, Dr Kizer provided Congressional testimony that articulated a vision for an ‘untraditional anti-smoking campaign’ that would use ‘hard hitting commercials.’ In his testimony he demonstrated a commitment to ‘blaze a new trail’ and tolerance for making mistakes as the campaign was perfected.4

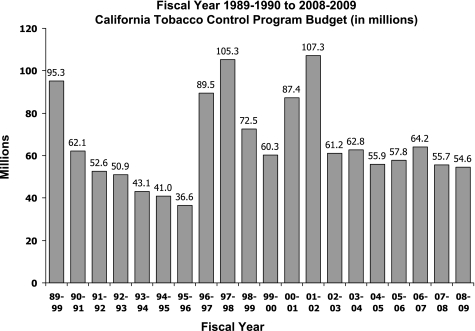

In fiscal year (FY) 1989–1990, CTCP was appropriated $95.3 million. Through the Budget act and later legislatively codified, multi-year spending authority was provided which allowed three years to expend funds appropriated in any given year. Achieved with voluntary health organisation assistance, this provision is a key factor in CTCP's resilience allowing preservation of core infrastructure and veteran staff during periods of budgetary fluctuation. The CTCP budget fluctuated markedly over the past two decades. These fluctuations are presented in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Fiscal years 1989–1990 to 2008–2009 California Tobacco Control Program budget ($millions).

In 1992, the $16 million media campaign was eliminated from the budget, but it was restored when the American Lung Association of California sued the State of California.5 However, by FY 1995–1996, CTCP's appropriation was reduced to $36.6 million with funding redirected to pay for immunisations and children's insurance programmes. Local health departments had their annual base allocation of $150 000 reduced to $110 000 and were required to spend one-third of it on perinatal outreach.6

These diversions resulted in divisive relations between public health programmes within the state health department. More importantly, the relationship between the State of California and voluntary health agencies became strained, culminating in a series of lawsuits filed against the State of California in 1994 and 1995. The courts ruled that the budget diversions and other legislative manoeuvrings to reduce the percentage of Proposition 99 funding appropriated to tobacco use prevention and cessation were illegal. In FY 1996–1997 restoration of the diverted funds began.5 The legal action taken by the voluntary health agencies ultimately prevented weakening the CTCP's effectiveness. In FY 2001–2002, funding appropriated as a result of the Master Settlement Agreement with the tobacco companies was eliminated when these funds were securitised to address a state budget deficit. The willingness of the voluntary health agencies to file lawsuits, their presence on the state oversight committee and local coalitions, and securing of multi-year spending authority represent investments in the programme that remain key to the programme's sustainability.

Programme infrastructure

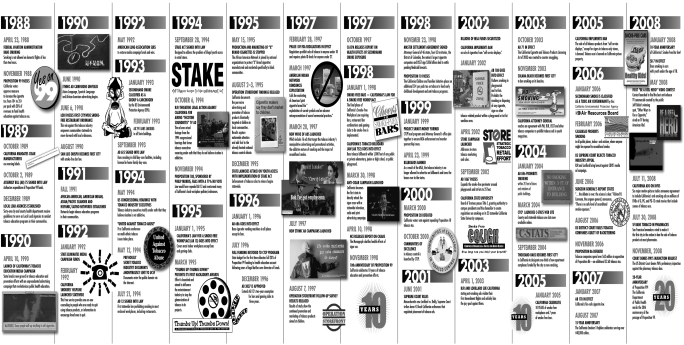

The programme infrastructure consists of a media campaign and state and community interventions which comprise the intervention. The media campaign frames the message, while community interventions implement advocacy campaigns and state interventions build the capacity of community projects. Evaluation/surveillance activities measure implementation and effectiveness of the intervention with state administration providing the human capital that manages the programme. A legislative mandated oversight committee advises CTCP.7 It publishes a master plan every three years that guides overall programme implementation and summarises progress towards accomplishing Master Plan objectives.8 Figure 2 depicts major events and programme accomplishments from 1988 to 2008.

Figure 2.

California Tobacco Control Program timeline of major events and accomplishments: 1988–2008.

Media campaign

Through use of paid advertising and public relations activities, the media campaign produces thought-provoking advertisements and press events that communicate the dangers of tobacco use, the health impact of secondhand smoke, the tobacco industry's marketing ploys and cessation assistance availability. Both general market-specific and priority population-specific campaigns are conducted.

State and community interventions

The state and community interventions component consists of: (1) statewide competitive grant projects that provide direct services and/or training and technical assistance (eg, cessation quitline, community organising help); (2) local health departments which operate comprehensive programmes; and (3) community-based competitive grant projects which may conduct single-issue focused advocacy campaigns or concentrate on a specific population (eg, Hispanic/Latinos).

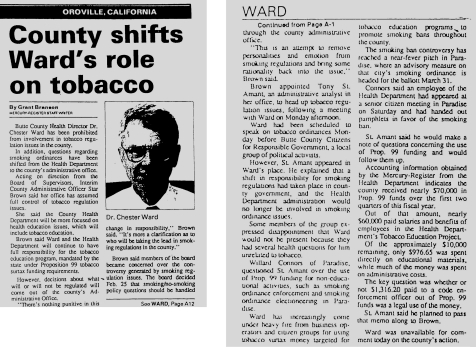

This blend of local health departments and competitively funded community and statewide grant projects provides diversity and balance. As the foundation of the state's public health infrastructure, local heath departments provide continuity, whereas competitive grant projects are cyclical. One benefit of providing funding to each health department is generation of the staff needed to create critical mass around a few key policy issues statewide. Local health departments often operate in a risk-adverse climate because they report to an elected board as illustrated by figure 3. Conversely, community-based agencies have more freedom to innovate without political interference. Statewide projects reduce duplication, promote quality through standardisation, increase accessibility to service and create cost efficiencies through enhanced purchasing power and reduced administrative costs.

Figure 3.

Oroville Mercury Register, 24 March 1992: Butte County Health Officer, Chester Ward prohibited from involvement in tobacco regulation.

In 2001, CTCP incorporated the use of Communities of Excellence tobacco control indicators and assets into procurements. Indicators reflect environmental measures (eg, extent of tobacco-industry sponsored events). Assets are measures that that promote and sustain tobacco control efforts (eg, the extent of community activism among adults to support tobacco control). They are used to identify priorities, create objectives and activities.9 10

Evaluation/surveillance

CTCP conducts an array of surveillance and evaluation activities. They include evaluating the media campaign (Cowling et al, see pages 38–43), community programmes (Modayil et al, see pages 31–37), school-based tobacco use prevention programmes (Park et al, see pages 44–51), and monitoring tobacco industry marketing (Roeseler et al, see pages 21–30).

The approach to statewide evaluation evolved from reliance upon external experts towards building internal and local capacity. This change increased CTCP's ability to adapt evaluation and surveillance efforts in response to environmental changes and to take advantage of emerging technology. Locally, evaluation uses an empowerment approach.11 Projects allocate at least 10% of their budget to evaluation. A university-based evaluation centre provides assistance to local projects and rates the quality of local evaluation reports which are disseminated through an electronic library system.12

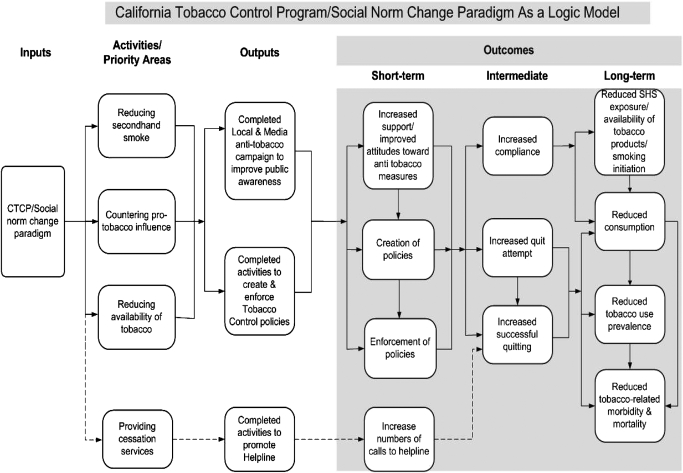

Programme logic model

CTCP's logic model (figure 4) identifies four programme priority areas that frame the media and community interventions and illustrate the presumed causal pathways that link programme efforts with outcomes. These areas are (1) reducing exposure to secondhand smoke, which focuses on smoking restrictions in public and private places; (2) countering pro-tobacco influences, which seeks to raise the price of tobacco and to curb the influence of tobacco marketing, campaign contributions, smoking in the movies; (3) reduction in the availability of tobacco through efforts that prohibit tobacco sales to minors, eliminate the free distribution of tobacco products and restrict where tobacco products can be sold; and (4) provision of cessation services through the California Smokers' Helpline (Helpline) and outreach to increase cessation support.

Figure 4.

California Tobacco Control Program/Social Norm Change Paradigm as a logic model.

Programme ideology

In 1989, the National Cancer Institute's (NCI) draft Standards for Comprehensive Smoking Prevention and Control was initially used as the underpinning for CTCP's work, but the ideology and framework for the programme evolved, based on the experience of implementing these standards on a statewide basis.13–16 Cutting across the programme's infrastructure and logic model is commitment to five core beliefs: (1) a comprehensive social norm change approach is more effective at reducing tobacco use than focusing on individuals who smoke; (2) the tobacco industry's predatory marketing and promotional practices must be countered; (3) programmes must focus at the community level because local leaders are most accountable and responsive to their communities; (4) programme efforts must reflect the multicultural nature of California and address health inequities; and (5) evaluation should be used to drive continual change.17

While infrastructure, policy priorities, media messages and evaluation measures have been fluid, adapting to external conditions over time (eg, budget, political administrations and evaluation results), commitment to the core beliefs is deeply embedded into the organisation's operation. Rooted in the authorising legislation, these beliefs enabled the programme to repeatedly deflect pressure that sought to remove anti-industry advertisements and to shift the focus of the programme to youth campaigns and policies that penalise youths for possessing tobacco, to transfer funding to support cessation classes, one-shot nicotine patch giveaway promotions and to diminish local programme evaluation requirements.

Social norm change

At the heart of CTCP's programmatic ideology is the concept of social norm change. The goal is to change the broad social norms around the use of tobacco, and to indirectly influence current and potential future tobacco users on a population level by creating a social environment and legal climate in which tobacco use becomes less desirable, less acceptable and less accessible.17 The approach focuses on changing community norms rather than changing individual behaviour. As new people, businesses and organisations move into the community, they inherit, adopt and conform to the established tobacco use norms.13 14 17 18 While a social norm change approach is emphasised, cessation services are also supported.

Countering the tobacco industry

Exposing and countering the tobacco industry's practices is a prominent element of the programme's ideology. The media campaign exposes the tobacco industry's marketing practices while community interventions (see Roeseler et al and Francis et al in this supplement) pursue policies to regulate the sale, distribution and marketing of tobacco. The media campaign's first advertisement boldly announced the programme's intention to take on the tobacco industry with the statement, ‘This is going to be a media campaign about a media campaign—as much about hype as hygiene. It's going to talk about a shared community opportunity and a shared community menace. There's never been anything quite like it’.19

Anti-industry messages are a major tool to counter pro-tobacco influences. They cause smokers to become angry and rebel against the tobacco industry's use of slick advertising and nicotine addiction to manipulate them.20 21 They hold the tobacco industry accountable while motivating individual interest in quitting. California smokers with highly negative attitudes about the tobacco industry were about 70% more likely to have made a quit attempt in the last 12 months and 1.6 times more likely to have a quit intention in the next 6 months in comparison to those scoring low in their negative attitudes about the tobacco industry (Zhang et al in this supplement).

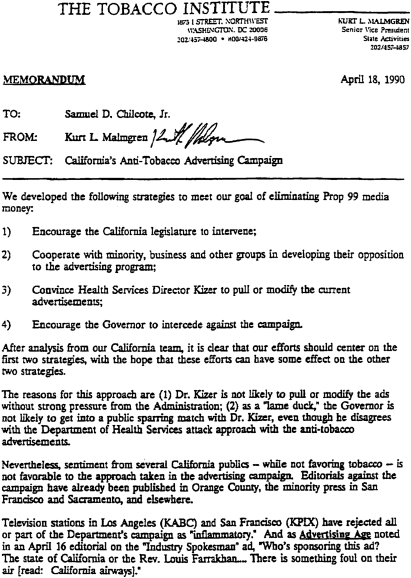

The tobacco industry repeatedly sought to suppress the media campaign's anti-industry advertising. Figure 5 presents an 18 April 1990, Tobacco Institute memorandum outlining their strategy to interfere with the media campaign.22 In 1994 RJ Reynolds' Chairman, James Johnston, demanded that the state health department stop airing its Nicotine Sound Bytes advertisement. This advertisement featured cigarette company executives testifying before the US Congress about the addictive nature of cigarettes, while text below their testimony repeated the phrase, ‘under oath’.23 In April 2003, a lawsuit filed against the State of California by RJ Reynolds and Lorillard attempted to halt the anti-industry advertisements on the basis these advertisements biased jurors and prevented access to a fair jury trial in class action lawsuits.24 25 Neither of these efforts were successful.

Figure 5.

A Tobacco Institute memorandum dated 18 April 1990.

Focus policy efforts locally

The third ideological belief is that policy efforts must focus locally. Strategically, this was crucial because the state capitol was a hostile environment for tobacco control efforts because of tobacco industry campaign contributions to state-elected officials.26–28 Additionally, CTCP's authorising legislation identified an organisational structure that favoured work at the local level through its mandates for local health departments and funding for community-based organisations.29

Parochial thinking promotes the concept that communities should have total autonomy as each community understands its own needs best. However, CTCP recognised that social norm change strategies are controversial. Left to their own devices, many communities would have preferred to fund smoking cessation classes rather than tackle exposure to secondhand smoke in the workplace or the tobacco industry-sponsored rodeo at the county fairgrounds. CTCP sought to balance the need for local autonomy with the state's need for an evidenced-based approach that would create critical mass around a few key policies and that could be supported by the statewide media campaign.

Factors important to the success of blending this broad statewide agenda setting approach with a local policy focus were: (1) engaging stakeholders and experts to design local policy campaigns; (2) providing training and technical assistance; (3) building local coalitions; (4) statewide media campaign support; and (5) educating elected officials to facilitate informed decision-making. The Communities of Excellence needs assessment and planning framework also helped shape a broad statewide agenda while allowing local communities to determine their priorities, objectives and the best path to achieve objectives.30

A consequence of building local policy momentum is that it indirectly influenced and shaped state policy (Francis et al in this supplement). In 1990, progressive tobacco control policy work was minimal; however, the media campaign's secondhand smoke messaging and policy-focused training set local policy change in motion. The wave of local policies propelled passage of the 1994 state clean indoor air legislation, smoke-free bars in 1998 and a comprehensive self-service display ban on tobacco products in 2004.31 32

As the programme matured, an unanticipated benefit of this approach was the election of former city council members to the state legislature who had exhibited tobacco control leadership locally. For example, as a San Diego City Councilman, former Assemblyman Juan Vargas successfully championed the restriction of tobacco advertising aimed at children. As a state legislator, he authored a law that banned smoking in playgrounds in 2002.33 The investment in building local coalitions, local capacity and working with local elected officials has paid dividends that would not have been realised if the emphasis had been at the state level.

Reflect the multicultural nature of the population

The fourth belief that makes up CTCP's core ideology is an acknowledgement that the programme must reflect the multicultural nature of California and address pre-existing tobacco-related health inequities. Historically, tobacco companies have exploited the unique social and cultural circumstances of various populations through targeted marketing strategies and many of these targeted populations had not been reached by tobacco control efforts.34 CTCP recognises that California's diverse communities do not live in silos and are affected by overall trends in California living, but at the same time appreciates that linguistically and culturally nuanced approaches are needed to motivate and engage specific populations. As a result, a dual multicultural perspective operates in tandem with fostering tailored interventions.

The media campaign supplements general market efforts with in-language and culturally relevant advertising and outreach campaigns. Within the state and community interventions programme component, the dual multicultural and targeted approach continues to evolve. Since 1992, English and Spanish quitline numbers have operated with four Asian language lines added in 1994. Each line is promoted by language specific mass media.35

In 1990, four statewide ethnic networks were established for the purpose of exchanging best practices and lessons learned in response to the large number of community projects funded to address these groups. By 2004, a similar effort was made for populations grouped by characteristics other than race/ethnicity but who also experienced tobacco-related health inequities and targeting. Seven statewide priority population partnerships were established to provide training and technical assistance to local projects and to conduct statewide advocacy campaigns addressing the major racial/ethnic groups, labour, low socioeconomic groups and the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community. Beginning in 2007, a declining budget could no longer sustain these seven partnership projects and a robust complement of community-based priority population projects; from 1990 to 2009 the number of competitive grant projects declined from 148 to 50.

An analysis of the partnership projects found that combining statewide advocacy campaigns with training and technical assistance was not optimal. In their advocacy role, some of the partnership projects criticised local projects and others for inadequately serving their community. While the criticism may have had merit, it had a chilling effect on projects seeking training and technical assistance.36 This finding led to separating funding for advocacy campaigns from the delivery of training and technical assistance services.

In 2008, priority population training and technical assistance services were consolidated into a single statewide project with a flexible organisational structure intended to be responsive to cross-cutting (eg, the culture of poverty, low literacy) and emerging population-specific needs (eg, mental illness). This consolidated service also draws on diverse individuals and organisations nationally, incorporating expert and peer-to-peer training and technical assistance approaches. In contrast, the previous models relied on California-based organisations to serve as the repository of expertise for each specific population.

Surveillance efforts also incorporate multicultural and targeted population measures. The California Tobacco Survey, an adult telephone survey conducted every three years, provides a sufficiently large sample to conduct analyses by race/ethnicity, sexual orientation and economic status. Population-specific surveillance studies augment the California Tobacco Survey and have been conducted among Chinese, Koreans, Asian Indians, LGBT and California-based military populations.37–41 Surveys among Vietnamese and rural American Indian/Alaskan Native populations are under way.

Use evaluation findings to drive continual change

The last belief that comprises CTCP's core ideology is the value it places on evaluation. It is viewed as essential to programme accountability and is deeply imbedded into organisational practices. Data are continuously used to improve interventions, surveillance methods and business operations as demonstrated in several of the articles contained in this supplement.

Programme innovation

The long-term focus of the enabling legislation provided the freedom that allowed for experimentation. This entrepreneurial environment led to innovations such as telephone-based cessation counselling and smoke-free bar policies in the 1990s. More recently it stimulated a growing body of outdoor smoke-free beach and multi-unit housing ordinances, as well as the first ordinance in the USA to prohibit the sale of tobacco products by pharmacies enacted by the City of San Francisco in 2008.42–46 Operationally, it facilitated the application of technology to improve the management of local programme data, the media campaign evaluation and advertisement concept testing and used social media to develop advertising creative.

In 2001, the Online Tobacco Information System was launched to improve contract management. This custom web-based system facilitated uniform data collection, the production of real-time reports, improved accountability, work quality and enhanced transparency. System search functions increased accessibility to project workplans and facilitated collaboration.47

In 2005, a population-based web-panel was adopted to conduct the media evaluation. This methodology was less costly and more flexible than previously used telephone surveys. Deployment of the survey was easily synchronised with the media campaign's placement rotation, and data collection was completed more expeditiously, which enhanced the ability to tie specific ads to population attitudinal changes. This allowed the programme to compare the strength of various advertisements before the next placement rotation, increasing the media intervention's efficacy.

In 2008, use of this methodology was expanded to include advertisement concept testing. The web-panel provides access to larger numbers of rural and Hispanic/Latino adults for advertisement concept testing at a reduced cost compared to face-to-face focus groups. It has been used to test the appropriateness of Spanish language advertising concepts to the general market and to test healthcare provider advertisements created in New York.

In 2007, CTCP launched the contest, Be a Reel Hero—Create. Direct. Save Lives. Anti-tobacco advertisements were solicited from California-based film schools, video contest websites and professional organisations. From nearly 50 entries, 19 finalists were selected and voted upon through a contest website, which generated more than one million visits. The winning advertisement was aired on the television programme American Idol in 2008.48

Programme dissemination

An important consideration in the CTCP's durability is the dissemination of the programme through its use of a shaping strategy to share it intellectual capital and influence public health practice. Shaping strategies have a transformational impact beyond their own organisation, redefining and reshaping industries and practice.49 CTCP's 1998, A Model for Change: the California Experience in Tobacco Control defined a vision for comprehensive tobacco control programmes that informed the CDC Best Practices for comprehensive tobacco control programmes and the subsequent implementation of programmes across the nation.1 17 Partnerships with national and international organisations lowered the cost and effort of others to opt into the social norm change strategy through access to training, advertisements and data collection instruments while evaluation findings inspired confidence in its viability. Consequently, California's social norm change model was disseminated on a massive scale that impacted public health practice beyond smoking, garnering credibility which made it more difficult for critics to dismantle the programme.

Dissemination efforts benefited immensely from national and international partnerships with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), NCI, the American Cancer Society-Home Office (ACS-NHO) and the WHO. Clean indoor air workplace legislation, telephone quitlines and media campaigns reflect three major interventions broadly disseminated.

California's early experiences with clean indoor air legislation provided tools to jurisdictions eager to enact similar legislation. A CDC-funded smoke-free bar case study, NCI-monograph, peer-reviewed literature and advertisements facilitated adoption of clean indoor air legislation by others.50 51

CTCP also played a major part in the establishment of telephone quitlines nationally. A 1998 training sponsored with ACS-NHO disseminated lessons learned from quitline administrators from the USA, Australia and Europe.52 Between 2000 and 2004, collaborations with CDC and NCI led to the dissemination of resources describing the theoretical basis for telephone-based cessation, operational considerations and their role in the context of a population-based cessation strategy.18 35 53 As of 2007, all 50 states, the District of Columbia and five US territories provide telephone-based tobacco cessation services.1

California's media campaign represents a third major contribution. A media campaign involves a large resource investment for advertisement concept development, testing, production and placement. Sharing advertising creative makes fiscal sense, saving scarce dollars for placement. CTCP has contributed more than 300 multilingual advertisements to the CDC Media Campaign Resource Center for dissemination. These advertisements have been used in over 20 states and internationally by WHO, Australia, Belgium, Canada and Germany (C Douglas, personal communications, 2009).

Programme success

CTCP's success can be assessed from a variety of perspectives, not the least of which is its survival with substantial, albeit markedly fluctuating, funding for nearly 20 years. Documentation of CTCP's effectiveness is extensive and covers a range of measures, many of which are described elsewhere in this supplement. For the purpose of this paper, results are presented on long-term and short-term outcomes identified in the logic model related to: (1) population-based measures of smoking behaviour; (2) protection from secondhand smoke; and (3) changes in the environment around the smoker.

Population-based measures of smoking behaviour

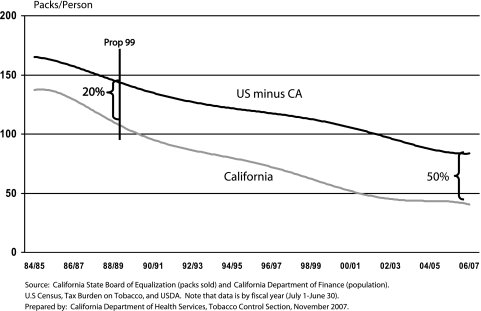

Arguably the most objective measure of changes in smoking behaviour at the population level is the number of cigarettes sold in the state. Per capita cigarette consumption for California, in contrast to the USA minus California, is presented in figure 6. California's per capita consumption at the time Proposition 99 was enacted in FY 1988–1989 was 123 packs, 20% lower than the average of the remaining states. By FY 2006–2007, it had fallen by more than two-thirds and was less than one-half of that for the remaining states.54

Figure 6.

California and US adult per capita cigarette pack consumption, 1984–1985 to 2006–2007.

This fall in cigarette consumption resulted from a decline in smoking prevalence (from 22.7% in 1988 to 13.8% in 2007) and a shift away from daily smoking, particularly heavy daily smoking. Among current smokers in 2005, 28.3% were occasional (non-daily smokers) and only 7.2% smoked more than 25 cigarettes per day compared to 16.4% in 1990.54

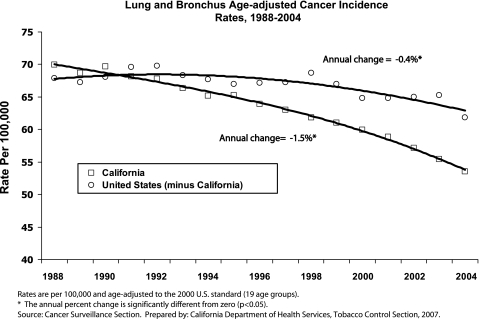

These trends in smoking behaviour translated into reductions in tobacco-related disease. From 1988 to 2004, lung cancer rates declined almost four times faster than the rate of decline in the rest of the USA55 56 (figure 7). While some of this reduction can be attributed to changes in smoking behaviour that preceded CTCP, a substantial fraction has been associated with CTCP's efforts.57 A similar accelerated decline was identified for heart disease.58 These changes in smoking behaviour resulted in an estimated $86 billion reduction in healthcare costs between 1989 and 2004.57

Figure 7.

Lung and bronchus age-adjusted cancer incidence rates, 1988–2004.

Changes in smoking behaviour over the last half century have left behind a residual smoking population that is disproportionately composed of less advantaged groups, raising the questions of whether tobacco control efforts are reaching or are effective for these populations. Table 1 presents the change in smoking prevalence over the nearly two decades of CTCP and the percentage change in smoking prevalence for each of the major race/ethnicity groups by gender. These changes are compared to those for the nation.

Table 1.

Change in smoking prevalence among California adults by race/ethnicity and gender, 1990–2005

| California | All states | |||||

| 1990 | 2005 | % Decline | 1990–91 | 2005 | % Decline | |

| Male | ||||||

| African American | 28.9 | 21 | 27.3% | 34.1 | 26.7 | 21.7% |

| Non-Hispanic white | 21.4 | 16 | 25.2% | 27.9 | 24 | 14.0% |

| Hispanic | 23.3 | 16.7 | 28.3% | 27.8 | 21.1 | 24.1% |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 21.8 | 16.1 | 26.1% | 24.5 | 20.6 | 15.9% |

| Female | ||||||

| African American | 24.2 | 17.1 | 29.3% | 22.9 | 17.3 | 24.5% |

| Non-Hispanic white | 18.5 | 13.1 | 29.2% | 24.1 | 20 | 17.0% |

| Hispanic | 11.7 | 6.8 | 41.9% | 15.9 | 11.1 | 30.2% |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 7.3 | 6.5 | 11.0% | 6.6 | 6.1 | 7.6% |

Sources: California Tobacco Survey, 1990–2005, weighted to 1990 California population.

Adapted from Al-Delaimy et al. University of California, San Diego, 2008.59

Tobacco use among US racial/ethnic minority groups: African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian American and Pacific Islanders, Hispanics: A Report of the Surgeon General. USDHHS, Center for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 1998.34

In California, smoking prevalence declined by approximately one-quarter for each of the race/ethnicity groups of males and, with the exception of Asian/Pacific Islander females, the percentage declines for females are slightly larger than those for males.59 While smoking prevalence disparities across these race/ethnicity groups remain, CTCP has had a remarkably uniform effect on smoking prevalence suggesting that it is both reaching and affecting disadvantaged populations. In contrast, data for the US as a whole demonstrate smaller changes in prevalence for each group.34 60

Changes in smoking prevalence over the 15-year interval are larger in California than for the nation as a whole, both as absolute and as percentage changes among African American and non-Hispanic white populations. The difference in smoking prevalence between African American and non-Hispanic white populations is smaller in the US data for 2005, reflecting a reduced disparity in smoking behaviour across racial groups in the USA, but this reduced disparity is the result of a markedly lower decline in smoking prevalence in the white population across the 15-year interval rather than an increased decline among African Americans.

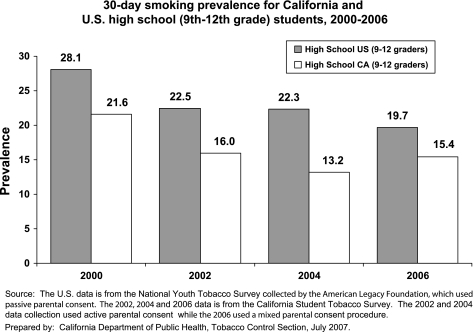

Preventing smoking initiation during adolescence and young adulthood is a significant success of CTCP, but continued effort is critical.59 Each year a new crop of children emerges into adolescence and is targeted by the tobacco industry. Even short-term lapses in the delivery of effective prevention efforts or the failure to counter new tobacco industry initiatives to promote initiation can result in dramatic changes in adolescent smoking initiation such as those that occurred nationally during the mid-1990s.61 Figure 8 compares adolescent smoking prevalence in California and nationally for the years between 2000 and 2006. While differences in study design exist among the data sources, rates of adolescent smoking are consistently lower in California compared to the nation.62 In addition, smoking prevalence among young adults (ages 18–24) also declined from 22.4% in the year 2000 to 17.2% in 2007.54 The increase in adolescent smoking prevalence observed between 2004 and 2006 in figure 8 is of concern and requires continued attention to programme intensity and reach.

Figure 8.

30-day smoking prevalence for California and US high school (9th–12th grade) students, 2000–2006.

Protections from secondhand smoke exposure

California has both led and benefited from the wave of normative, regulatory and legislative changes about where smoking is unacceptable. Programme elements and an aggressive agenda-setting media campaign during the early programme years accelerated the existing groundswell for smoking restrictions culminating in the first statewide bans on smoking in restaurants, bars and workplaces.

In 2007, 75.8% of Californians agree that smoking should be banned in outdoor restaurant dining areas and 85.3% agree that smoking should be restricted in outdoor common areas within apartment and condominium complexes.54 By 2005, almost all indoor workers in California reported that they had a smoke-free workplace and 78.4% of all Californians reported having a smoke-free home.54 In 2006, 55.1% of youths reported that they had not been in a room with someone smoking in the previous seven days and 73.9% reported not having been in a car with someone smoking in the previous seven days.54

Changes in the environment around the smoker

Denormalising tobacco use, a core component of CTCP, influences all aspects of smoking behaviour and is broadly responsible for much of the programme's success. One aspect of that success is the progressively more stringent local regulation of tobacco sales. By 2009, there were 80 local ordinances licensing tobacco sales, an increase from only one in 1998 and there were 144 local ordinances banning self-service tobacco sales, an increase from 27 in 1994.63 64

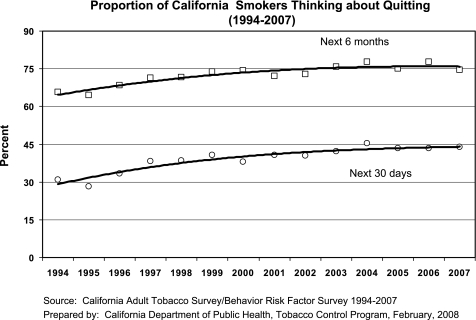

Denormalisation also has a profound effect on smokers and may be responsible for a paradox in the California experience. Logic would dictate that as those who can most easily quit smoking achieve abstinence, the remaining smokers would be more addicted and more resistant to tobacco control efforts. In contrast, figure 9 presents the fraction of California smokers who are thinking about quitting in the next 30 days and in the next 6 months. Over the same years where smoking prevalence fell dramatically, interest in future cessation increased rather than decreased. This contrast suggests that CTCP was successful in increasing interest in cessation even as the smokers most susceptible to tobacco control messages quit. This also suggests that the existing population-based interventions are continuing to work and that a shift towards more individual-based and intensive cessation strategies is not yet necessary to continue the decline in smoking prevalence.

Figure 9.

Proportion of California smokers thinking about quitting (1994–2007).

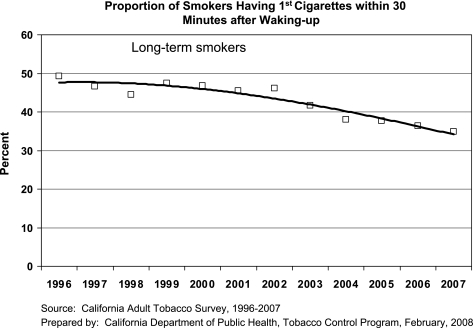

CTCP's ability to alter the environment to decrease the hold smoking has on smokers is also demonstrated by figure 10, which presents the change in the percentage of California smokers who reported smoking their first cigarette within 30 minutes of waking. The decline in this measure over time may reflect a decline in the intensity of addiction among California smokers or it may reflect the increasing number of smokers who live in smoke-free homes and therefore have more difficulty smoking soon after waking. Either explanation reflects a measure of programme success, but the more important lesson is that individual components of the programme are likely to produce a total benefit much greater than the sum of their independent effects.

Figure 10.

Proportion of smokers having first cigarettes within 30 minutes after waking up.

Discussion

CTCP's sustainability goes beyond being a well-funded tobacco control programme with demonstrated results. California shares a history with other state programmes that were well-funded, used evidence-based approaches, demonstrated results and operated in an atmosphere that included economic downturns, lawsuits and tobacco industry interference. But unlike other successful state programmes that were dismantled,65–69 CTCP continues to be vibrant and its communities remain at the centre of policy innovation nationally.42–46 63

In considering CTCP's effectiveness, the takeaway message is that it should be viewed as a unified programme rather than a collection of independent interventions. The programme was designed and implemented as one where the parts complement and reinforce each other and its effectiveness is dependent on its comprehensive strategy rather than any one part of the intervention. Before CTCP, tobacco control efforts focused largely on individual behaviour change. However, in order to create a substantive public health benefit, interventions must sum to create a significant change at the population level. Powerful interventions that have a small reach will have little impact on disease rates, whereas weaker interventions that impact large numbers of smokers will have a cumulative effect on disease rates.18 The social norm change strategy employed by CTCP capitalised on this concept. It assisted smokers in California to quit or decrease their consumption, protected non-smokers from secondhand smoke and prevented tobacco use uptake with a reach and impact that would not have been feasible using individual-focused strategies given the programme budget.

CTCP did not reach the goal of reducing tobacco consumption by 75% in 10 years. However, meaningful outcomes were achieved: (1) a 56% decrease in the proportion of adult smokers smoking more than 25 cigarettes per day; (2) a 61% decline in adult per capita consumption; (3) a 35% decline in adult smoking prevalence; (4) large declines (>25%) in smoking prevalence among all major race/ethnic groups, with the exception of Asian/Pacific Islander women; (5) the second lowest smoking prevalence rates in the nation among youths aged 12–17; (6) a decline in lung and bronchus cancer rates nearly four times faster than the rest of the nation; and (7) healthcare cost savings of $86 billion.8 55–57 59 62

Despite these successes, 22 states have stronger state clean indoor air laws, California's $0.87 tobacco tax ranks 31st in the nation and tobacco use remains higher among several population subgroups.8 59 In 2007, legislation to strengthen the state clean indoor air law was vetoed.70 Between 2005–2007, several attempts to increase the tobacco tax failed. These include a 2006 ballot measure and 2007 healthcare reform legislation sponsored by Governor Schwarzenegger.71 72 These failures are attributed to the requirement that legislative tax increases must be approved by a two-thirds majority in both houses, tobacco industry lobbying and a partnership with hospitals on the ballot measure that provided negative campaign fodder concerning the use of the tax.71 73 In 2009, several tobacco tax increases are pending, including a bill authored by Senator Padilla, a former champion of tobacco control issues as a member of the Los Angeles City Council.74 75 Lack of success at the state level to strengthen the state's clean indoor air legislation and to increase the tobacco tax reinforces the value of the programme's strong local community focus. Local ordinances in five California communities mandating that multi-unit housing complexes designate 25% to 100% of its units as smoke-free and the City of Chico's 2007 total ban on the non-sale distribution of all tobacco products, on public and private property are examples of progressive local tobacco control efforts.45 76

As CTCP considers the future, decreasing smoking rates and narrowing disparities across population subgroups is a priority. Expanding partnerships with those that serve the socially and economically disadvantaged is essential for these efforts to succeed. Using the social norm change strategy to increase the price of tobacco products, decrease exposure to secondhand smoke, increase the availability and use of cessation services and capitalising on the opportunities provided by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act 77 are part of the future agenda. This will be done by considering and exploring the strategies described in box 1.8 78

Box 1. Future considerations for tobacco control in California.

Establish a tobacco tax indexed to inflation and establish a minimum retail price for tobacco products set at the manufacturer's level to prevent price manipulation by geography, store type and season in order to reduce tobacco industry targeting of populations and markets.8 78

Restrict time, place and manner of tobacco advertising or marketing consistent with the First Amendment and Food and Drug Administration tobacco control legislation.77

Develop a population-based quit plan for California that expands coverage of and utilisation of tobacco cessation benefits especially among the socially and economically disadvantaged.8

Strengthen and conduct a health and human services partnership campaign among organisations and agencies serving the most socially and economically disadvantaged populations such as mental health system, alcohol and drug treatment providers, licensed child and adult housing, food assistance programmes, housing assistance programme and employment assistance. Seek to establish uniform policies regarding secondhand smoke, acceptance of tobacco industry philanthropy and tobacco cessation support.8

Establish policies that prohibit the distribution of free or low-cost tobacco products, coupons, coupon offers, rebate offers, gift certificates, gift cards or other similar offers for tobacco products consistent with the First Amendment and Food and Drug Administration tobacco control legislation.8

Establish a 100% smoke-free indoor workplace standard for all workplaces under the jurisdiction of state, county, city and tribal governments.8

Use local tobacco retail licensing and permits to eliminate retail tobacco sales wherever direct healthcare services are provided and decrease the density of tobacco retailers.8

Establish policies to restrict smoking in individual units of multi-unit housing including balconies and patios.8

Establish an anti-tobacco advertising fairness doctrine standard for tobacco product buydowns, promotions and other retail marketing which would establish a 1:1 or 3:1 placement of anti-tobacco advertising for each pro-tobacco advertisement.78

Establish sunshine or disclosure requirements (similar to political campaign disclosure requirements) to require disclosure of tobacco manufacturer/wholesalers/distributor payments to retailers (eg, incentives, buydowns and promotions).78

What this paper adds.

The California Tobacco Control Program is one of the longest running comprehensive tobacco control programmes in the USA.

Factors adding to the programme's sustainability were a clear vision that focused on the long view, risk taking, external public support, a well integrated programme ideology, an evidenced-based approach tempered with innovation, a balance of a top-down with a bottom-up approach, use of shaping strategy to disseminate the programme and accountability in both its business operation and measuring programme effectiveness.

The programme demonstrated the effectiveness of a social norm change approach to decrease cigarette consumption, adult and youth smoking prevalence, to protect non-smokers from secondhand smoke, reduce lung cancer and result in healthcare expenditure savings.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tonia Hagaman, MPH, Chief of Local Programs and Advocacy Campaigns, California Tobacco Control Program, California Department of Public Health for her invaluable comments.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Contributors: Both authors contributed to the conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version published.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Best practices for comprehensive tobacco control programs—2007. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bal DG. Designing an effective statewide tobacco control program-California. Cancer 1998;83:217–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.California Health and Safety Code Sections 104370 (d-f), 104385 (c) (5), 104420 (4) (F), and 104425 (c) (3).

- 4.Kizer KW. Testimony regarding California's anti-smoking media campaign presented to subcommittee on transportation on hazardous materials, committee on energy and commerce, US house of representatives, 1990April30 http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ton92d00 (accessed 2 Jun 2009).

- 5.Glantz SA, Balbach ED. Tobacco war: inside the California battles. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Novotny T, Siegel M. California's tobacco control saga. Health Affairs 1996;15:58–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.California Health and Safety Code Sections 104365–14370.

- 8.Tobacco Education and Research Oversight Committee Endangered investment: toward a tobacco-free California 2009–2011-master plan. Sacramento, CA: Tobacco Education and Research Oversight Committee, 2009. http://www.cdph.ca.gov/services/boards/teroc/Documents/TEROCMasterPlan09-11.pdf (accessed 26 Jun 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 9.California Department of Health Services, Tobacco Control Section Communities of excellence in tobacco control. Module 1: introduction to communities of excellence. Sacramento, CA: CDHS/TCS, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 10.California Department of Health Services, Tobacco Control Section Communities of excellence in tobacco control. Module 2: conducting a communities of excellence needs assessment. Sacramento, CA: CDHS/TCS, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fetterman DM. Empowerment evaluation: an introduction to theory and practice. In: Fetterman DM, Kaftarian SJ, Wandersman A, eds. Empowerment evaluation knowledge and tools for self-assessment and accountability. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1996:3–48 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang H, Cowling D, Koumjian K, et al. Building local program evaluation capacity toward a comprehensive evaluation. New Directions for Evaluation 2002;95:39–56 [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Cancer Institute Smoking and tobacco control monograph no. 1. strategies to control tobacco use in the United States: a blueprint for public health action in the 1990's. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Health, National Cancer Institute, 1991. NIH Publication No. 92-3316. [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Cancer Institute Tobacco control monograph no. 16. assist, shaping the future of tobacco prevention and control. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Health, National Cancer Institute, 2005. NIH Pub No. 05-5645. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bal DG, Lloyd JC, Roeseler A, et al. California as a model. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:69–73 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rohrbach LA, Howard-Pitney B, Unger JB, et al. Independent evaluation of the California tobacco control program: relationships between program exposure and outcomes, 1996–1998. AJPH 2002;975–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.California Department of Health Services, Tobacco control section. a model for change: the California experience in tobacco control. Sacramento, CA: California Department of Health Services, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Cancer Institute National Cancer Institute. Population based smoking cessation: proceedings of a conference on what works to influence cessation in the general population. Smoking and tobacco control monograph No 12. Bethesda MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, 2000. NIH Pub. No. 00-4892. [Google Scholar]

- 19.California Department of Health Services Tobacco control section. First, the smoke, now, the mirrors. Sacramento, California, USA: California Department of Health Services, 11April1990 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poza Consulting Service. Anti-tobacco advertisement concept test focus groups. Prepared by Ground Zero Advertising on behalf of Tobacco Control Section, State of California. November2007

- 21.Hershey JC, Niederdeppe J, Evans W, et al. The theory of “truth”: how counter industry campaigns affect smoking behavior among teens. Health Psychol 2004;24:22–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malmgren KL. California's anti-tobacco advertising campaign. Philip Morris: Tobacco Institute; 18April1990. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/pdg52f00/pdf?search=%22malmgren%20kl%20california%201990%22 (accessed 26 Jun 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balbach ED, Glantz SA. Tobacco control advocates must demand high quality media campaigns; the California experience. Tob Control 1998;7:397–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, R.J. Reynolds Smoke Shop, Inc. and Lorillard Tobacco Company v Diana M. Bontá, Director of the California Department of Health Services and Dileep G. Bal, Acting Chief of the Tobacco Control Section of the California Department of Health Services. Complaint for injunctive and declaratory relief, 2003April1 http://fl1.findlaw.com/news.findlaw.com/hdocs/docs/tobacco/rjrlorca40103cmp.pdf (accessed Feb 2009).

- 25.Ibrahim JK, Glantz SA. Tobacco industry strategies to oppose tobacco control media campaigns. Tob Control 2006;15:50–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glantz SA, Begay ME. Tobacco industry campaign contributions are affecting policy making in California. JAMA 1994;272:1176–82 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Monardi F, Glantz SA. Are tobacco industry campaign contributions influencing state legislative behavior? AJPH 1998;88:918–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sherman R. Shaming big tobacco's friends in California. Tob Control 1996;5:189–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.California Health and Safety Code Sections 104375 (h) – (p); 104380, 104385, and 104390.

- 30.California Department of Health Services, Tobacco Control Section Communities of excellence in tobacco control. Module 4: developing a tobacco control intervention and evaluation plan. Sacramento, CA: CDHS/TCS, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adams CF. Smoke-free California: democracy meets public health. Natl Civ Rev 1998;87:311–16 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adams FA. Healthy communities and public policy: four success stories. Public Health Rep 2000;115:212–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.TotalCapitol.com http://www.totalcapitol.com?people_id=79 (accessed 11 Oct 2008).

- 34.US Department of Health and Human Services Tobacco use among US racial/ethnic minority groups-African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders and Hispanics: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, Georgia: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 35.California Department of Health Services, Tobacco control section. The California smokers' helpline: a case study. Sacramento, CA: California Department of Health Services, 2000May [Google Scholar]

- 36.California Department of Health Services, Tobacco Control Section Changes to the model for the delivery of advocacy campaigns and training/technical assistance service related to priority populations-briefing document: formative research and key findings. Sacramento, California, USA: California Department of Health Services, 2007January23 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carr K, Beers M, Kassebaum T, et al. California Chinese American tobacco use survey-2004. Sacramento, CA: California Department of Health Services, 2005. http://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/tobacco/Documents/CTCPChineseTobaccoStudy.pdf (accessed 26 Jun 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carr K, Beers M, Kassebaum T, et al. California Korean American tobacco use survey-2004. Sacramento, CA: California Department of Health Services, 2005. http://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/tobacco/Documents/CTCPKoreanTobaccoStudy.pdf (accessed 26 Jun 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCarthy WJ, Divan H, Shan D, et al. California Asian Indian tobacco use survey-2004. Sacramento, CA: California Department of Health Services, 2005. http://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/tobacco/Documents/CTCPAsianIndianTobaccoStudy.pdf (accessed 26 Jun 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bye L, Gruskin E, Greenwood G, et al. California Lesbians, gays, bisexuals, transgender tobacco use survey-2004. Sacramento, CA: California Department of Health Services, 2005. http://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/tobacco/Documents/CTCP-LGBTTobaccoStudy.pdf (accessed 26 Jun 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crawford R, Olsen C, Thompson B, et al. California active duty tobacco use survey-2004. Sacramento, CA: California Department of Health Services, 2005. http://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/tobacco/Documents/CTCPActiveDutyTobaccoStudy.pdf (accessed 26 Jun 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Center for Tobacco Policy and Organizing Comprehensive outdoor secondhand smoke ordinances, 2009November http://www.center4tobaccopolicy.org/_files/_files/Comprehensive%20Outdoor%20Secondhand%20Smoke%20Ordinances%20November%202008.pdf (accessed 1 Jul 2009).

- 43.California Clean Air Project Southern California communities with smoke-free beaches, 2007February http://www.lapublichealth.org/tob/pdf/Beach_Feb_22_07revised.pdf (accessed 1 Jul 2009).

- 44.Center for Tobacco Policy and Organizing Policy and organizing matrix of local smoke-free housing policies, 2008October http://www.center4tobaccopolicy.org/_files/_files/Matrix%20of%20Local%20Smokefree%20Housing%20Policies%20October%202008.pdf (accessed 1 Jul 2009).

- 45.Center for Tobacco Policy and Organizing Comparison of nonsmoking house units ordinances, 2008October http://www.center4tobaccopolicy.org/_files/_files/Comparison%20of%20Nonsmoking%20Housing%20Units%20Ordinances.pdf (accessed 1 Jul 2009).

- 46.City and County of San Francisco Municipal Code, Article 19J: Prohibiting pharmacies from selling tobacco products, 2008August7 http://www.municode.com/Resources/gateway.asp?pid=14136&sid=5 (accessed 26 Jun 2009).

- 47.Augustyniak B, Finely A, Aguero D, et al. The information professional's role in creating business management systems. Information Outlook 2005;9:12–7 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Be a reel hero—create. direct. save lives. http://www.beareelhero.com/ (accessed 25 Jun 2009).

- 49.Hagel J, Brown JS, Davison L. Shaping strategy in a world of constant disruption. Harv Bus Rev. http://www.hbsp.harvard.edu/hbsp/hbr/articles/article.jsp?articleID=R0810E&ml_action=g (accessed 9 Sep 2008).

- 50.Wingo C, Kiser D, Boschert T, et al. Eliminating smoking in bars, taverns and gaming clubs: the California smoke-free workplace act. A case study. Sacramento, California, USA: California Department of Health Services, Tobacco Control Section, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 51.National Cancer Institute Smoking and tobacco control monograph no. 10. health effects of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke: the report of the california environmental protection agency. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, NIH Pub. No. 99-4645. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 52.California Department of Health Services, Tobacco Control Section and American Cancer Society, National Home Office Tobacco cessation quitline training. 1998August28-29

- 53.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Telephone quitlines: A resource for development, implementation, and evaluation. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, Final edn, 2004September [Google Scholar]

- 54.California Department of Public Health, Tobacco Control Program (2009). California Tobacco Control Update 2009.

- 55.Cowling DW, Kwong SL, Schlag R, et al. Declines in lung cancer rates-California, 1988–1997. MMWR 2000;49:1066–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barnoya J, Glantz Association of the California tobacco control program with declines in lung cancer incidence. Cancer Causes Control 2004;15:689–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lightwood JM, Dinno A, Glantz SA. Effect of the California tobacco control Program on personal health care expenditures. PLoS Med 2008;5:e178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fichetenberg CM, Glantz SM. Association of the California tobacco control program with declines in cigarette consumption and mortality from heart disease. N Engl J Med 2000;343:1772–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Al-Delaimy WK, White MM, Trinidad DR, et al. The California tobacco control program: can we maintain the progress? Results from the California tobacco survey, 1990–2005 Vl. 2. La Jolla, CA: University of California, San Diego; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Tobacco use among adults—United States. MMWR 2005;55:1145–8 [Google Scholar]

- 61.National Cancer Institute Smoking and tobacco control monograph, No. 14: changing adolescent smoking prevalence. Where it is and why. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, NIH Publication No. 02-5082. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 62.United States Department of Health and Human Services Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA); Office of Applied Studies. (June, 2008). State estimates of substance abuse from the 2005–2006 national surveys on drug use and health. Appendix C, Table C.14 Cigarette Use in Past Month, by Age Group and State: 2004–2005 and 2005–2006 NSDUHs. (DHHS publication No. SMA 08-4311, NSDUH Series H-33). http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/2k6state/AppC.htm#C-14 (accessed 24 Feb 2009).

- 63.Center for Tobacco Policy and Organizing Matrix of strong tobacco retailer licensing ordinances, 2009. http://www.center4tobaccopolicy.org/_files/_files/Licensing%20Matrix%20May%202009.pdf (accessed 9 Jul 2009).

- 64.Americans for Nonsmokers' Rights' Foundation Local tobacco control ordinance data base. Youth access provisions-December 2007 report. Berkeley, CA: Americans for Nonsmokers' Rights Foundation [Google Scholar]

- 65.Givel MS, Glantz SA. Failure to defend a successful state tobacco control program: policy lessons from Florida. Am J Public Health 2000;90:762–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Koh HK, Judge CM, Robbins H, et al. The first decade of the Massachusetts tobacco control program. Public Health Rep 2005;120:482–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lum K, Glantz S. The cost of caution: tobacco industry political influence and tobacco policy making in Oregon 1997–2007. USA: Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education. Tobacco Control Policy Making, Paper Oregon 2007, 2007September http://repositories.cdlib.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1072&context=ctcre (accessed 10 Nov 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tsoukalas TH, Ibrahim JK, Glantz SA. Shifting tides: Minnesota tobacco politics. United States: Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education. Tobacco Control Policy Making: (March1, 2003). Paper MN2003. http://repositories.cdlib.org/ctcre/tcpmus/MN2003 (accessed 10 Nov 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tung G, Glantz S. Clean air now, but a hazy future: tobacco industry political influence and tobacco policy making in Ohio 1997–2007. United States: Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education. Tobacco Control Policy Making, 2007May22 Paper Ohio 2007. http://repositories.cdlib.org/ctcre/tcpmus/Ohio2007 (accessed 10 Nov 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schwazengger A. Assembly Bill 1467 (DeSaulnier) veto message, 14October2007. http://gov.ca.gov/index.php?/press-release/7713/ (Accessed 3 July 2009).

- 71.Hong M, Barnes RL, Glantz G. Tobacco control in California 2003–2007: missed opportunities. Center for tobacco control research and education. San Francisco. San Francisco, CA: School of Medicine. University of California, 2007October [Google Scholar]

- 72.California State Senate staff analysis of Assembly Bill 1x 1. 2008January8 http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/pub/07-08/bill/asm/ab_0001-0050/abx1_1_cfa_20080125_153139_sen_comm.html (accessed 3 July 2009).

- 73.The Center for Tobacco Policy and Organizing Tobacco money in California politics: campaign contributions and lobbying expenditures of tobacco interests; 2009June, Report for 2008-2008 election cycle. http://www.center4tobaccopolicy.org/_files/_files/Tobacco%20Money%20in%20California%20Politics.pdf (accessed 3 Jul 2009).

- 74.Padilla A, Steinberg D, De Saulnier M, et al. Assembly Bill 600, 2009June9 http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/pub/09-10/bill/sen/sb_0551-0600/sb_600_bill_20090609_amended_sen_v97.pdf (accessed Jul 2009).

- 75.Tobacco fee may hit merchants: Blocking sales to minors would be program goal. Los Angeles Business Journal, 26July2004. http://goliath.ecnext.com/coms2/gi_0199-38402/Tobacco-fee-may-hit-merchants.html (accessed 3 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chico Municipal Code Chapter 9.18 Nonsale distribution of smokeless tobacco or cigarettes. http://www.chico.ca.us/municipal_code/title_9.pdf (accessed 2009 Apr 8).

- 77.H.R. 1256 Family smoking prevention and control act, 6June2009. http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=111_cong_bills&docid=f:h1256enr.txt.pdf (accessed 3, Jul 2009).

- 78.Feighery E, Rogers T, Ribisl K. Tobacco retail price manipulation policy strategy summit proceedings. Sacramento, CA: California Department of Public health, California Tobacco Control Program, 2009 [Google Scholar]