Abstract

Introduction

The growth factor myostatin (Mstn) is a negative regulator of skeletal muscle mass. Mstn−/− muscles are hypertrophied, stronger, and more glycolytic than Mstn+/+ muscles suggesting that they might not perform endurance exercise as well as Mstn+/+ mice. Indeed, it has previously been shown that treadmill exercise training reduces triceps weight in Mstn−/− mice.

Methods

To analyze the response of Mstn−/− muscle to endurance exercise in detail, we carried out endurance training over 4 weeks to examine muscle mass, histology, and oxidative enzyme activity.

Results

We found that muscle mass was reduced with training in several muscles from both genotypes with no evidence of muscle damage. Citrate synthase activity is increased with training in control and mutant mice. Non-trained Mstn−/− mice did, however, have lower maximal exercise capacity compared to Mstn+/+ mice.

Discussion

These results show that Mstn−/− muscle retains the metabolic plasticity necessary to adapt normally to endurance training.

Keywords: Myostatin, hypertrophy, skeletal muscle, endurance training, exercise capacity, glycolytic fiber type

INTRODUCTION

Myostatin (Mstn), a member of the transforming growth factor β superfamily of growth and differentiation factors, is a negative regulator of skeletal muscle mass that is expressed predominantly in skeletal muscle1–3. Myostatin is found in serum in an inactive latent complex that can be activated by proteolysis to allow signaling through the activin receptor type IIB and at least one other unknown receptor.1–3 Individual muscles in adult Mstn−/− mice are twice the mass of those from Mstn+/+ littermates due to both an increase in muscle fiber number (hyperplasia) and size (hypertrophy).4–8 These effects of myostatin are dose dependent: Heterozygous mutant mice have a milder increase in muscle mass than homozygous mutant mice.8 As in mice, mutations in the Mstn gene concomitant with increased muscling have also been found in cattle, sheep, dogs, and a child demonstrating conservation of function in mammals.9 In addition to increased muscle mass, Mstn−/− mice have increased insulin sensitivity, reduced adipose tissue mass, and resistance to weight gain when fed a high-fat diet.10–14

Inhibition of myostatin function in normal adult mice5,15–19 or mice with neuromuscular diseases20–26 also results in an increase in muscle mass. These results have generated tremendous interest in the development of pharmacological inhibitors of myostatin for treatment of muscle wasting diseases in patients. Recently, a clinical trial to examine safety of an anti-myostatin neutralizing monoclonal antibody was reported.27 The results demonstrated safety27 and a dose-dependent trend toward larger fibers28 in adult muscular dystrophy patients.

In addition to its potential for clinical utility, concerns have been raised that anti-myostatin therapy could be used to improve athletic performance.29 Individual skeletal muscle fibers can be classified by their contractile and metabolic properties, which have differing effects on strength and endurance.30 Glycolytic fibers are fast contracting fibers that fatigue rapidly, while oxidative fibers are slow contracting fibers that are fatigue resistant. Resistance training, exercise of short duration but high intensity to increase strength, causes hypertrophy primarily of glycolytic fibers and minimal changes in fiber type.31 Endurance or aerobic training, exercise of long duration but lower intensity, causes fibers to shift toward more oxidative metabolism without increases in muscle mass.31 Mstn−/− mice have an increase in the proportion of glycolytic muscle fibers as well as increased mass so their phenotype more closely resembles that of resistance-trained athletes.5,6,32 Indeed, two of three studies that measured force production in Mstn−/− mice showed an increase in absolute force compared to Mstn+/+ mice.8,32,33 An increase in force production has also been shown in some,18,23 but not all,26,34 normal mice when they were treated with postnatal myostatin inhibitors. To date, the description of athletic performance in competitive sports in individuals with Mstn mutations is limited. Heterozygosity of a naturally occurring Mstn mutation is correlated with improved racing grade in 200–300 m sprints relative to non-mutants in whippet racing dogs.35 In addition, the heterozygous mother of the only known human homozygous for a Mstn mutation was a professional athlete.36 These observations suggest genetic loss of the Mstn gene may be advantageous for performance in specific sports.

Although absolute force seems to be increased in Mstn−/− mice, some research has indicated that Mstn null muscle might be impaired. For instance, Mstn−/− extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscle has an increased force deficit after lengthening contractions.8 In addition, Amthor et al.32 found a greater occurrence of tubular aggregates in fast glycolytic type IIB fibers in aging Mstn−/− muscle. Muscle tubular aggregates are non-specific accumulations of the sarcoplasmic reticular and possible mitochondrial membranes. They are found in a variety of myopathies but sometimes also occur in seemingly healthy muscle.37 It has therefore been suggested that Mstn−/− mice might be more susceptible to muscle damage due to reduced connective tissue collagen composition38 or possible metabolic abnormalities.32,39

The increased muscle bulk and glycolytic phenotype of Mstn−/− mice suggest that, although they are stronger, they would not perform endurance exercise as well as wild-type mice. Mstn−/− mice that underwent treadmill exercise training had increased bone strength but lower triceps muscle weight compared to non-exercise-trained Mstn−/− mice.39 This result raised the possibility that endurance exercise induced muscle damage in Mstn−/− mice. We therefore asked whether endurance exercise results in muscle damage or reduced metabolic adaptability in Mstn−/− mice. To this end, we carried out treadmill run training to examine muscle mass, histology, and oxidative enzyme activity in multiple muscles from Mstn+/+ and Mstn−/− mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Experimental protocols of this study were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the NIH, NIDDK. The mice used were generation N6 on a C57BL/6 genetic background. Mstn−/− and Mstn+/+ mice were produced from homozygous matings. Parental genotypes were determined by PCR.40 They were housed individually with a 12-hour light/dark cycle and ad libitum access to food and water. Exercise training was performed using 12-week-old males, while exercise capacity was measured in 14-week-old males (see below).

Exercise Training

Exercise training was performed as in Hamrick et al.39 Briefly, mice were designated to either a non-trained group or an exercise-trained group. Mice in the trained group performed treadmill run training on a level treadmill (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH) calibrated for angle and speed. Mice were trained at a speed of 12 m/min for 30 min 5 consecutive days/week for 4 weeks. Mice that were reluctant to run on the treadmill despite receiving two stimuli, an air stream to the hind feet and tickle on the hind feet, were not included in the study (one Mstn+/+ mouse and two Mstn−/− mice). Mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation on the last day of training or equivalent time point for non-trained controls.

Exercise Capacity

A separate non-trained group of mice was used to determine if there were differences in maximal running endurance capacity. Mice started running at 8.5 m/min on a level treadmill for 3 min. Every 3 min the treadmill speed was increased by 2.5 m/min while the treadmill angle was increased by 5% at 6, 12, and 21 min after starting. Mice were considered exhausted when they could no longer move forward from the back of the lane despite prompting stimuli described above. Total Work performed was calculated by converting angle to %grade and summing the amount of Work performed during each increment using the formula: body weight (kg) × speed (m/s) × time (s) × grade × 9.8 m/s2.

Evans Blue Dye Injections

Evans blue dye is an auto fluorescent diazo dye that is impermeable to intact muscle fibers and is routinely used to quantify damaged fibers.41 Dye (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in phosphate buffer (0.15 M sodium chloride, 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.4) at a concentration of 10 mg/ml and filter sterilized. Mice received an intraperitoneal injection of dye at 100 mg/kg body weight 1 h before the last exercise training session or comparable time point for non-trained controls.

Muscle Collection, Histology, and SDH Staining

Mice were weighed, and triceps, pectoralis, quadriceps, gastrocnemius, plantaris, tibialis anterior, and soleus muscles, and retroperitoneal and gonadal fat pads were excised bilaterally after 4 weeks training or non-training. Muscles used for histology (triceps, gastrocnemius, plantaris, soleus, tibialis anterior, and EDL) were partially embedded in 7% gum tragacanth (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), mounted to cork, frozen in liquid nitrogen-cooled isopentane, and stored at −80°C. Serial transverse sections (10 µm) were cut by cryostat at −20°C. Only sections from the widest part of the muscle were used. Frozen muscle sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H/E) to observe muscle histology including fiber morphology (central nuclei, hypercontraction, degeneration, and splitting) and fat and fibrotic infiltration. Evans blue dye staining was visualized on unstained gastrocnemius and triceps sections using a green excitation fluorescence filter that emits at wavelengths of 590–650 nanometers (TRITC HYQ, Nikon Instruments, Inc., Melville, NY). Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) staining was carried out as previously described,42 and fibers were visually categorized and counted as either oxidative (dark and medium stained) or glycolytic (low stained).

SERCA1 detection

Frozen muscle sections were placed in acetone for 1 min, air dried, and incubated with primary mouse monoclonal anti-sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 1 (SERCA1; Affinity Bioreagents, Rockford, IL) diluted 1:500. Slides were then incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-laminin to stain fiber borders (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), washed, incubated with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) diluted 1:1000, and mounted in SlowFade® Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Adjacent sections were incubated with cell culture supernatant diluted 1:1 from a hybridoma that secretes mouse monoclonal anti-myosin heavy chain type IIB (BF-F3; ATCC, Manassas, VA). Type IIB immunostaining was detected using the Mouse on Mouse peroxidase substrate kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA).

Protein Concentration and Citrate Synthase Activity

Muscles (triceps, quadriceps, gastrocnemius, and plantaris) were separately frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground to a fine powder using a mortar and pestle. Powder was further homogenized in a 1:40 dilution of CelLytic™ MT Cell Lysis Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) with protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete Mini, Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). Protein concentration was measured by the Bradford method (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Citrate synthase activity of 8 µg muscle protein was determined using an enzymatic assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed using a student’s t-test (exercise capacity) or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (SPSS v. 16.0, Chicago, IL). Non-homogeneous data as determined by a Levene’s test were log transformed to restore equal variance before ANOVA analysis. When data were still non-homogeneous (SDH and body and fat pad weights), a Kruskal-Wallis test was performed. Tukey’s honestly significant difference post hoc test was used to determine the source of differences. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Mstn+/+ and Mstn−/− mice underwent endurance training by running on a level treadmill for 30 min/day for 5 days/week. After 4 weeks, there were no significant differences in body weights among all four groups (Table 1). As expected, most individual Mstn−/− muscles weighed ~1.9–2.2 times more than those of Mstn+/+ mice for both untrained and trained groups (P < 0.01; Table 1). The soleus, a small slow contracting muscle, weighed ~1.5 times more in Mstn−/− than in Mstn+/+ mice (P < 0.01; Table 1). Under this training regimen, Hamrick et al.39 found that Mstn−/− triceps muscle weight was reduced 10% after 4 weeks of training. Similarly, we also found that muscle weights in the trained Mstn−/− mice were an average of 6% lower than those of non-trained Mstn−/− mice, and four of seven reached statistical significance (Table 1). The mass of the trained triceps muscle, for example, was 6% lower than that of the non-trained triceps muscle (P < 0.05). Unexpectedly, in Mstn+/+ mice, training also reduced muscle mass an average of 5% compared to non-trained Mstn+/+ mice, although this difference only reached statistical significance in two out of seven muscles examined (Table 1). The trained Mstn+/+ triceps muscle, unlike in the previous study, was 7% smaller by weight compared to non-trained triceps muscle (P < 0.05). Fat pad weights were not significantly altered in response to training in either genotype (Table 1).

Table 1.

Body, muscle, and fat pad weights of non-trained and trained Mstn+/+ and Mstn−/− mice.

| Mstn+/+ | Mstn−/− | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body/Tissue Weight | Non-trained | Trained | Non-trained | Trained |

| N | 15 | 14 | 14 | 14 |

| Body mass (g) | 31.2 ± 0.7 | 30.1 ± 1.0 | 34.6 ± 0.5 | 33.5 ± 0.4 |

| Triceps (mg) | 144.9 ± 3.6 | *135.1 ± 2.3 | 312.6 ± 4.8 | *294.3 ± 6.7 |

| Pectoralis (mg) | 156.9 ± 3.7 | *144.2 ± 2.8 | 340.5 ± 11.4 | 320.1 ± 8.5 |

| Quadriceps (mg) | 220.4 ± 4.8 | 208.4 ± 4.2 | 421.1 ± 6.8 | †396.0 ± 8.5 |

| Gastrocnemius (mg) | 137.8 ± 2.5 | 130.5 ± 3.6 | 265.0 ± 4.4 | †247.5 ± 4.8 |

| Plantaris (mg) | 18.3 ± 0.6 | 16.8 ± 0.5 | 35.5 ± 0.5 | *32.0 ± 1.5 |

| Tibialis anterior (mg) | 49.8 ± 1.1 | 46.5 ± 1.0 | 92.9 ± 1.5 | 89.5 ± 1.7 |

| Soleus (mg) | 9.3 ± 0.5 | 9.8 ± 0.5 | 14.9 ± 0.5 | 14.4 ± 0.7 |

| Retroperitoneal fat (mg) | 145.8 ± 23.8 | 192.9 ± 22.9 | 60.5 ± 9.7 | 70.6 ± 6.2 |

| Gonadal fat (mg) | 423.1 ± 52.5 | 520.3 ± 52.9 | 222.6 ± 17.0 | 230.5 ± 19.7 |

For all muscle and fat pad weights, Mstn+/+ tissues are significantly different from Mstn−/− tissues (P < 0.01).

Values are mean ± SEM.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01, non-trained versus trained mice within a genotype

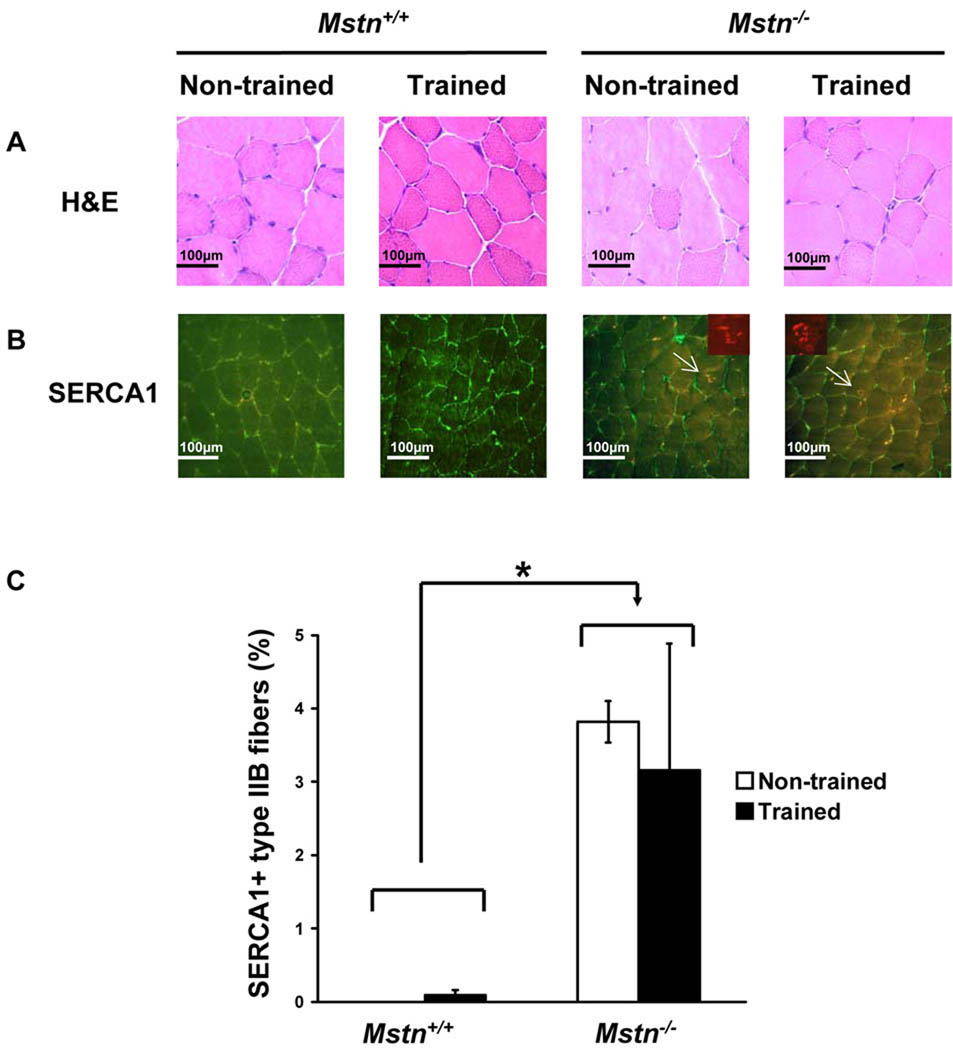

We next examined H/E stained cross sections of muscle for signs of muscle damage or regeneration. Exercise training did not alter the histology of the EDL, tibialis anterior, gastrocnemius, plantaris, soleus, or triceps muscles from either genotype (Fig. 1A and data not shown). Muscles from both Mstn+/+ and Mstn−/− mice appeared normal without signs of fatty infiltration, fibrosis, or necrosis. Centrally located nuclei, which are a characteristic of regenerated fibers, were not found in most of these muscles, whether trained or non-trained of either genotype. Only a few muscles of either genotype had an occasional fiber or two with a centrally located nucleus.

Figure 1.

Endurance exercise training does not cause muscle damage in Mstn−/− muscle. (A) H/E stained triceps muscle showing normal histology after exercise training. (B) Mstn+/+ and Mstn−/− triceps immunofluorescence detection of SERCA1 (red) and laminin (green). Arrows mark SERCA1+ fibers shown in insets. Insets show SERCA1 staining only. (C) Quantification of SERCA1+ type IIB fiber proportions from non-trained and exercise trained Mstn+/+ and Mstn−/− triceps muscle (N = 4–5 for each group). *P < 0.05, Mstn+/+ compared to Mstn−/− mice.

To assess damage, Evans blue dye was injected into mice after the last training session, and cross sections of the tibialis anterior, EDL, and triceps muscles were examined. Less than 1% of the fibers took up dye in any of the muscles regardless of training or genotype (data not shown) indicating that severe damage did not occur at least during the last few days of exercise training.

Next, we looked for evidence of tubular aggregates in the triceps muscle using SERCA1 immunostaining. In Mstn+/+ mice, there were no SERCA1+ aggregates found in type IIB fibers in non-trained muscle, and only rare SERCA1+ fibers were found in the trained muscle (Fig. 1B, C). As expected, the proportion of SERCA1+ IIB fibers, although relatively low compared to what has been described in older mutants,32 was greater in Mstn−/− triceps than in wild-type triceps (Fig. 1B, C). Exercise training, however, had no effect on the proportion of type IIB fibers that contained SERCA1+ aggregates (Fig. 1B, C). No SERCA1+ aggregates were found in any fibers other than type IIB fibers in any of the four groups.

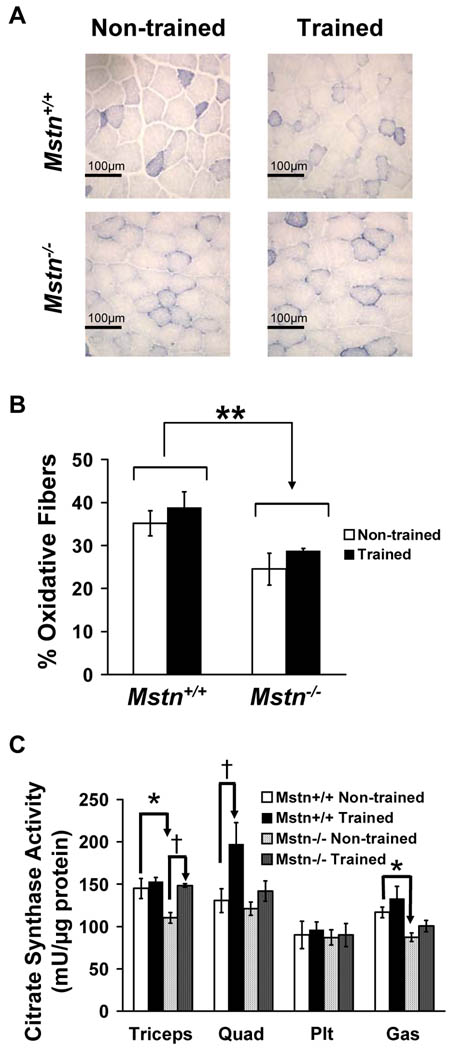

Because Mstn−/− muscle has more fast glycolytic fibers and reduced mitochondrial number compared with Mstn+/+ muscle,5,6,32 we asked whether muscle from Mstn−/− mice can respond appropriately to endurance training by increasing oxidative capacity. SDH staining on muscle sections showed that genotype had a significant effect on metabolic fiber type with fewer oxidative fibers in Mstn−/− triceps compared to Mstn+/+ triceps as expected (Fig. 2A, B). After 4 weeks of endurance training, there was a trend toward a training effect with an increased proportion of oxidative fibers in both genotypes (P = 0.08; Fig. 2A, B). For a more quantitative determination of oxidative function, we analyzed the activity of citrate synthase, the first enzymatic step in the citric acid cycle, in four muscles from each of our four groups. Citrate synthase activity in the triceps and gastrocnemius muscles was significantly lower in non-trained Mstn−/− mice than in non-trained wild-type mice most likely reflecting the increase in fast glycolytic fiber types (Fig. 2C). Training increased citrate synthase activity in one of four muscles in each genotype although not the same muscle (Fig. 2C). In Mstn+/+ mice, but not in Mstn−/− mice, exercise training significantly increased citrate synthase activity in quadriceps muscle. Citrate synthase activity of the Mstn−/− triceps, however, was significantly increased in trained compared to non-trained Mstn−/− triceps. There were no genotype or exercise training effects on the citrate synthase activity of the plantaris.

Figure 2.

Increased oxidative profile after endurance training. (A) SDH staining of triceps muscle from non-trained and exercise-trained Mstn+/+ and Mstn−/− mice showing medium and dark stained fibers (oxidative) and low stained fibers (glycolytic). (B) Quantification of oxidative fibers in SDH stained triceps muscle (**P < 0.01, genotype effect for combined non-trained and trained fiber proportions; N = 4 for each group). C) Citrate synthase activity of triceps, quadriceps (Quad), plantaris (Plt), and gastrocnemius (Gas) muscles from non-trained and exercise-trained Mstn+/+ and Mstn−/− mice (N = 4–5 for each group). Genotype effect for combined non-trained and trained Mstn+/+ versus Mstn−/− triceps, quadriceps, or gastrocnemius muscles: P < 0.05 (not marked). For individual groups: *P < 0.05, non-trained Mstn+/+ versus non-trained Mstn−/− mice, and †P < 0.05, non-trained versus trained mice within a genotype.

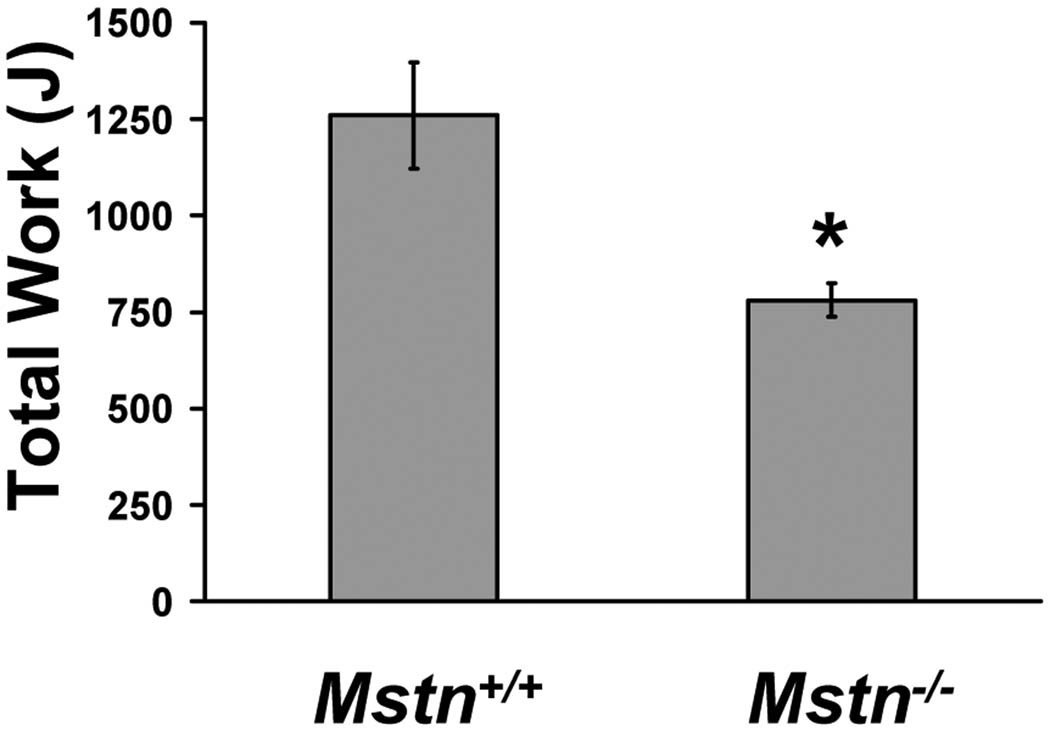

Because glycolytic muscle is more susceptible to fatigue,30 we analyzed overall running exercise capacity in Mstn+/+ and Mstn−/− mice. We performed progressive endurance capacity run testing on non-trained mice by increasing treadmill running speed and grade until exhaustion. Mstn−/− mice ran for 28% less total time and 40% shorter distance, which resulted in a 38% lower endurance run capacity compared to Mstn+/+ mice as calculated by Work performed (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Exercise capacity of 14-week-old male Mstn+/+ (N = 6) and Mstn−/− (N = 7) mice expressed as total Work performed (Joules). *P < 0.05.

DISSCUSION

Previously, Hamrick et al.39 found that endurance training reduced triceps muscle weight in Mstn−/− mice but not Mstn+/+ mice. In contrast, in our study, we found that the same exercise training protocol significantly reduced triceps muscle mass in both Mstn+/+ and Mstn−/− mice. This was the trend of response in other exercise-trained muscles compared to non-trained muscles for both Mstn+/+ and Mstn−/− mice, although the muscle weight differences reached statistical significance in more muscles in Mstn−/− mice. Reductions in mass did not seem to be due to exercise-induced damage, because we found no evidence of an increase in necrosis, degeneration, or regeneration in either genotype. In a recent report, mdx mice, a model of muscular dystrophy, and double mdx, Mstn−/− mice were subjected to a single bout of downhill running.43 Consistent with our results, deletion of Mstn did not further increase muscle damage in mdx mice caused by downhill running.

In addition to mild muscle mass decreases, our results show that exercise training also affected the muscle oxidative profile in both genotypes. As expected for non-exercised muscles, citrate synthase activity was lower in two out of four Mstn−/− muscles compared to Mstn+/+ muscles. Exercise training tended to increase citrate synthase activity in each genotype. The results reached statistical significance in one of four muscles, but not the same muscle, underscoring the necessity for analysis of multiple muscles. One possible explanation for this difference is that the Mstn−/− mice might run with a different gait than Mstn+/+ mice which would recruit muscles differently for different types of training. In this regard, altered running mechanics have been described in some Mstn null Belgian Blue cattle which seemed to be proportional to the degree of muscle hypertrophy.44 Similarly, we observed Mstn−/− mice running more flat-footed with their tails held lower than Mstn+/+ mice when they ran at the higher speeds during maximal exercise capacity tests. Nevertheless, the increase in oxidative metabolism in a Mstn−/− muscle after endurance training demonstrates that at least some Mstn−/− muscles maintain sufficient metabolic adaptability to respond appropriately to endurance exercise despite their glycolytic profile.

We also found that Mstn−/− mice have reduced maximal exercise capacity. Fiber type composition is one of many factors that play a role in endurance capacity, and genetically altered mice with a more oxidative/less glycolytic profile are better endurance athletes. For example, muscle-specific activated peroxisome proliferator-activator receptor delta (PPARδ) transgenic mice have more oxidative muscles and have remarkably elevated treadmill running time and distance.45 In contrast, like Mstn−/− mice, transgenic mice that express constitutively active Akt specifically in skeletal muscle have hypertrophy of glycolytic fibers, an increase in muscle mass, and a reduction in exercise capacity.46 This phenotype suggests that Mstn−/− mice are less suited for endurance running and better suited for short sprint races and ballistic activities. Indeed, whippet dogs that are heterozygous for mutations in Mstn tend to be higher ranked track runners at distances that are short sprint races for dogs.35

Similar to our results, a recent study found that mdx mice treated with a myostatin inhibitor ran a shorter distance during a treadmill exercise test compared to untreated mdx mice26 although Work performed was not determined. Other reports, however, suggest postnatal myostatin inhibition in normal mice results in greater endurance and reduced fatigue. Tang et al.16 reported that mice vaccinated against myostatin postnatally have increased grip endurance as measured by the length of time they are able to hang from a tightrope. Inhibition of myostatin in aged mice by treatment with an anti-myostatin neutralizing monoclonal antibody causes a non-significant increase in run time and distance.34 In the same study, however, myostatin inhibition simultaneous with treadmill run training was found to enhance the increase in exercise capacity caused by training alone. Furthermore, the aged mice treated with a myostatin inhibitor alone have reduced muscle fatigue after repeated sciatic nerve stimulation.34 The different results in endurance tests between mice with genetic Mstn deletion and mice with postnatal myostatin inhibition might be explained by the effects of myostatin on prenatal muscle development. Postnatal inhibition of myostatin does not result in as great a muscle mass increase as complete genetic deletion and does not cause hyperplasia or a shift toward fast glycolytic fiber types.5,15,16,18,23,26,47,48 These differences suggest that much of the Mstn null phenotype is the result of altered prenatal or perinatal muscle development. Thus, increasing muscle fiber hypertrophy in sarcopenic aged mice by inhibiting myostatin as in LeBrasseur et al.34 might help to restore muscle size and function to levels similar to younger mice and/or prevent further muscle loss with aging rather than make them unusually muscular. The result would therefore be to improve overall endurance rather than to cause a resistance-trained phenotype with significantly reduced exercise capacity as in Mstn−/− mice. It will be interesting to determine the running exercise capacity in younger mice that receive postnatal myostatin inhibition.

It is unclear why in Hamrick et al. training induced lower triceps mass in Mstn−/− but not Mstn+/+ mice,39 while in our study training resulted in lower triceps mass in both genotypes. One possible explanation is differences in relative training intensity due to genetic background differences between the strains used in each study. CD-1 mice have a greater critical running speed than C57BL/6 mice49 and therefore have a higher maximum aerobic endurance capacity. Thus, running at 12 m/min would be a relatively less intense training stimulus for CD-1 mice, the strain used in the previous study, compared to C57BL/6 mice, the strain used in our study. In addition, we have shown here that Mstn−/− mice on a C57BL/6 genetic background have a lower endurance exercise capacity than wild-type controls. It is reasonable to expect that, similar to our findings, CD-1 Mstn−/− mice most likely have a lower endurance exercise capacity than CD-1 Mstn+/+ mice and that CD-1 Mstn−/− mice therefore also trained at a higher relative intensity than control mice in the previous study. Taken together, it is likely that the relative training intensity for the protocol used in both studies would be lower for the CD-1 Mstn+/+ mice compared to the CD-1 Mstn−/−, C57BL/6 Mstn+/+, and C57BL/6 Mstn−/− mice. The training regimen may therefore not have been at a high enough relative intensity to result in lower muscle weights in the CD-1 Mstn+/+ mice.

Regardless, the reasons for lower muscle mass in trained mice compared to non-trained mice of either genotype are unclear. Consistent with our results, two studies in humans have found that marathon or cross-country training decreases fiber diameter although these effects may be temporary.50,51 Interestingly, certain types of concurrent endurance and resistance training reduce hypertrophy and gains in strength compared to resistance training alone.31,52 A similar effect is seen with simultaneous endurance training and myostatin inhibition (as the hypertrophic stimulus) in aged mice: Four weeks of treadmill running largely prevents the increase in quadriceps mass induced by treatment with a myostatin inhibitor alone.34 The mice in our study did not receive any hypertrophic stimulus, but mice are still growing at the age our study began. This raises the possibility that endurance training carried out in this study may have slowed or stopped postnatal muscle hypertrophy that would normally occur between 12 and 16 weeks of age. Furthermore, some studies have shown a reduction in protein synthesis after endurance training suggesting a possible mechanism for reduced fiber sizes.52

In summary, short-term endurance training results in modestly reduced muscle mass in some muscles without muscle damage in both Mstn+/+ and Mstn−/− mice. Additionally, Mstn−/− mice have lower endurance run capacity, suggesting they are better suited for more anaerobic activities but are still able to adapt to aerobic training by increasing oxidative metabolism. Further work is needed to determine if, with long-term endurance training, Mstn−/− mice would be able to increase their endurance capacity without further loss of muscle mass.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIDDK. We thank Jennifer Portas for assistance with treadmill running and genotyping.

ABBREVIATIONS

- EDL

extensor digitorum longus

- H/E

hematoxylin and eosin

- Mstn

myostatin

- SERCA1

Sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 1

- SDH

succinate dehydrogenase

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee SJ. Regulation of muscle mass by myostatin. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:61–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.012103.135836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel K, Amthor H. The function of Myostatin and strategies of Myostatin blockade-new hope for therapies aimed at promoting growth of skeletal muscle. Neuromuscul Disord. 2005;15:117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2004.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh FS, Celeste AJ. Myostatin: a modulator of skeletal-muscle stem cells. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:1513–1517. doi: 10.1042/BST0331513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amthor H, Otto A, Vulin A, Rochat A, Dumonceaux J, Garcia L, et al. Muscle hypertrophy driven by myostatin blockade does not require stem/precursor-cell activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7479–7484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811129106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Girgenrath S, Song K, Whittemore LA. Loss of myostatin expression alters fiber-type distribution and expression of myosin heavy chain isoforms in slow- and fast-type skeletal muscle. Muscle Nerve. 2005;31:34–40. doi: 10.1002/mus.20175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McPherron AC, Huynh TV, Lee SJ. Redundancy of myostatin and growth/differentiation factor 11 function. BMC Dev Biol. 2009;9:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-9-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McPherron AC, Lawler AM, Lee SJ. Regulation of skeletal muscle mass in mice by a new TGF-b superfamily member. Nature. 1997;387:83–90. doi: 10.1038/387083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendias CL, Marcin JE, Calerdon DR, Faulkner JA. Contractile properties of EDL and soleus muscles of myostatin-deficient mice. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101:898–905. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00126.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee SJ. Sprinting without myostatin: a genetic determinant of athletic prowess. Trends Genet. 2007;23:475–477. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo T, Jou W, Chanturiya T, Portas J, Gavrilova O, McPherron AC. Myostatin inhibition in muscle, but not adipose tissue, decreases fat mass and improves insulin sensitivity. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamrick MW, Pennington C, Webb CN, Isales CM. Resistance to body fat gain in 'double-muscled' mice fed a high-fat diet. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30:868–870. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin J, Arnold HB, Della-Fera MA, Azain MJ, Hartzell DL, Baile CA. Myostatin knockout in mice increases myogenesis and decreases adipogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;291:701–706. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McPherron AC, Lee SJ. Suppression of body fat accumulation in myostatin-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:595–601. doi: 10.1172/JCI13562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilkes JJ, Lloyd DJ, Gekakis N. Loss-of-function mutation in myostatin reduces tumor necrosis factor alpha production and protects liver against obesity-induced insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2009;58:1133–1143. doi: 10.2337/db08-0245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee SJ, Reed LA, Davies MV, Girgenrath S, Goad ME, Tomkinson KN, et al. Regulation of muscle growth by multiple ligands signaling through activin type II receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18117–18122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505996102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang L, Yan Z, Wan Y, Han W, Zhang Y. Myostatin DNA vaccine increases skeletal muscle mass and endurance in mice. Muscle Nerve. 2007;36:342–348. doi: 10.1002/mus.20791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Welle S, Burgess K, Mehta S. Stimulation of skeletal muscle myofibrillar protein synthesis, p70 S6 kinase phosphorylation, and ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation by inhibition of myostatin in mature mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296:E567–E572. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90862.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whittemore LA, Song K, Li X, Aghajanian J, Davies M, Girgenrath S, et al. Inhibition of myostatin in adult mice increases skeletal muscle mass and strength. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;300:965–971. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02953-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolfman NM, McPherron AC, Pappano WN, Davies MV, Song K, Tomkinson KN, et al. Activation of latent myostatin by the BMP-1/tolloid family of metalloproteinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15842–15846. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2534946100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bogdanovich S, Krag TO, Barton ER, Morris LD, Whittemore LA, Ahima RS, et al. Functional improvement of dystrophic muscle by myostatin blockade. Nature. 2002;420:418–421. doi: 10.1038/nature01154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bogdanovich S, McNally EM, Khurana TS. Myostatin blockade improves function but not histopathology in a murine model of limb-girdle muscular dystrophy 2C. Muscle Nerve. 2008;37:308–316. doi: 10.1002/mus.20920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bogdanovich S, Perkins KJ, Krag TO, Whittemore LA, Khurana TS. Myostatin propeptide-mediated amelioration of dystrophic pathophysiology. FASEB J. 2005;19:543–549. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2796com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haidet AM, Rizo L, Handy C, Umapathi P, Eagle A, Shilling C, et al. Long-term enhancement of skeletal muscle mass and strength by single gene administration of myostatin inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4318–4322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709144105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morrison BM, Lachey JL, Warsing LC, Ting BL, Pullen AE, Underwood KW, et al. A soluble activin type IIB receptor improves function in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Exp Neurol. 2009;217:258–268. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parsons SA, Millay DP, Sargent MA, McNally EM, Molkentin JD. Age-dependent effect of myostatin blockade on disease severity in a murine model of limb-girdle muscular dystrophy. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:1975–1985. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qiao C, Li J, Jiang J, Zhu X, Wang B, Xiao X. Myostatin propeptide gene delivery by adeno-associated virus serotype 8 vectors enhances muscle growth and ameliorates dystrophic phenotypes in mdx mice. Hum Gene Ther. 2008;19:241–254. doi: 10.1089/hum.2007.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wagner KR, Fleckenstein JL, Amato AA, Barohn RJ, Bushby K, Escolar DM, et al. A phase I/II trial of MYO-029 in adult subjects with muscular dystrophy. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:561–571. doi: 10.1002/ana.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krivickas LS, Walsh R, Amato AA. Single muscle fiber contractile properties in adults with muscular dystrophy treated with MYO-029. Muscle Nerve. 2009;39:3–9. doi: 10.1002/mus.21200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fedoruk MN, Rupert JL. Myostatin inhibition: a potential performance enhancement strategy? Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2008;18:123–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2007.00759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schiaffino S, Reggiani C. Molecular diversity of myofibrillar proteins: gene regulation and functional significance. Physiol Rev. 1996;76:371–423. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.2.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baar K. Training for endurance and strength: lessons from cell signaling. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38:1939–1944. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000233799.62153.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amthor H, Macharia R, Navarrete R, Schuelke M, Brown SC, Otto A, et al. Lack of myostatin results in excessive muscle growth but impaired force generation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1835–1840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604893104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagner KR, McPherron AC, Winik N, Lee SJ. Loss of myostatin attenuates severity of muscular dystrophy in mdx mice. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:832–836. doi: 10.1002/ana.10385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.LeBrasseur NK, Schelhorn TM, Bernardo BL, Cosgrove PG, Loria PM, Brown TA. Myostatin inhibition enhances the effects of exercise on performance and metabolic outcomes in aged mice. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:940–948. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mosher DS, Quignon P, Bustamante CD, Sutter NB, Mellersh CS, Parker HG, et al. A mutation in the myostatin gene increases muscle mass and enhances racing performance in heterozygote dogs. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e79. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schuelke M, Wagner KR, Stolz LE, Hübner C, Riebel T, Komen W, et al. Myostatin mutation associated with gross muscle hypertrophy in a child. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2682–2688. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pavlovičová M, Novotová M, Zahradník I. Structure and composition of tubular aggregates of skeletal muscle fibres. Gen Physiol Biophys. 2003;22:425–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mendias CL, Bakhurin KI, Faulkner JA. Tendons of myostatin-deficient mice are small, brittle, and hypocellular. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:388–393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707069105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hamrick MW, Samaddar T, Pennington C, McCormick J. Increased muscle mass with myostatin deficiency improves gains in bone strength with exercise. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:477–483. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.051203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manceau M, Gros J, Savage K, Thome V, McPherron A, Paterson B, et al. Myostatin promotes the terminal differentiation of embryonic muscle progenitors. Genes Dev. 2008;22:668–681. doi: 10.1101/gad.454408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamer PW, McGeachie JM, Davies MJ, Grounds MD. Evans Blue Dye as an in vivo marker of myofibre damage: optimising parameters for detecting initial myofibre membrane permeability. J Anat. 2002;200:69–79. doi: 10.1046/j.0021-8782.2001.00008.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kiernan JA. Histological and histochemical methods: theory and practice. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann; 1999. pp. 319–320. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wagner KR, Liu X, Chang X, Allen RE. Muscle regeneration in the prolonged absence of myostatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2519–2524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408729102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holmes JH, Ashmore CR, Robinson DW. Effects of stress on cattle with hereditary muscular hypertrophy. J Anim Sci. 1973;36:684–694. doi: 10.2527/jas1973.364684x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang YX, Zhang CL, Yu RT, Cho HK, Nelson MC, Bayuga-Ocampo CR, et al. Regulation of muscle fiber type and running endurance by PPARdelta. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Izumiya Y, Hopkins T, Morris C, Sato K, Zeng L, Viereck J, et al. Fast/Glycolytic muscle fiber growth reduces fat mass and improves metabolic parameters in obese mice. Cell Metab. 2008;7:159–172. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grobet L, Pirottin D, Farnir F, Poncelet D, Royo LJ, Brouwers B, et al. Modulating skeletal muscle mass by postnatal, muscle-specific inactivation of the myostatin gene. Genesis. 2003;35:227–238. doi: 10.1002/gene.10188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Welle S, Bhatt K, Pinkert CA, Tawil R, Thornton CA. Muscle growth after postdevelopmental myostatin gene knockout. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E985–E991. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00531.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Billat VL, Mouisel E, Roblot N, Melki J. Inter- and intrastrain variation in mouse critical running speed. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:1258–1263. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00991.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harber MP, Gallagher PM, Creer AR, Minchev KM, Trappe SW. Single muscle fiber contractile properties during a competitive season in male runners. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287:R1124–R1131. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00686.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Trappe S, Harber M, Creer A, Gallagher P, Slivka D, Minchev K, et al. Single muscle fiber adaptations with marathon training. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101:721–727. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01595.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nader GA. Concurrent strength and endurance training: from molecules to man. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38:1965–1970. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000233795.39282.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.