SUMMARY

Serine recombinases promote specific DNA rearrangements by a "cut and paste" mechanism which involves cleavage of all four DNA strands at two sites recognized by the enzyme. Dissecting the order and timing of these cleavage events and the steps leading up to them is difficult because the cleavage reaction is readily reversible. Here, we describe assays using activated Sin mutants and a DNA substrate with a 3’-bridging phosphorothiolate modification which renders Sin-mediated DNA cleavage irreversible. We find that activating Sin mutations promote DNA cleavage rather than simply stabilize the cleavage product. Cleavage events at the scissile phosphates on complementary strands of the duplex are tightly coupled, and the overall DNA cleavage rate is strongly dependent on Sin concentration. When combined with analytical ultracentrifugation data, these results suggest that Sin catalytic activity and oligomerization state are tightly linked, and that activating mutations promote formation of a cleavage-competent oligomeric state that is normally formed only transiently within the full synaptic complex.

Keywords: site-specific recombination, DNA topology, serine recombinase, resolvase, 3’-bridging phosphorothiolate-modified DNA

INTRODUCTION

Serine recombinases catalyze DNA rearrangements in diverse biological settings. Well-studied systems are involved in transposon mobility, phage genome integration, gene switching, and dissemination of resistance elements.1; 2 All of these systems rely on assembly of a synaptic complex to guide the outcome of the recombination reaction (reviewed in1). Within the synaptic complex, the DNA is cleaved at specific bonds, and the DNA ends are exchanged to create the recombinant products with no net change in bond energy. However, the order and timing of the events along the recombination pathway, including the transition from inactive to active species, remain to be fully characterized.

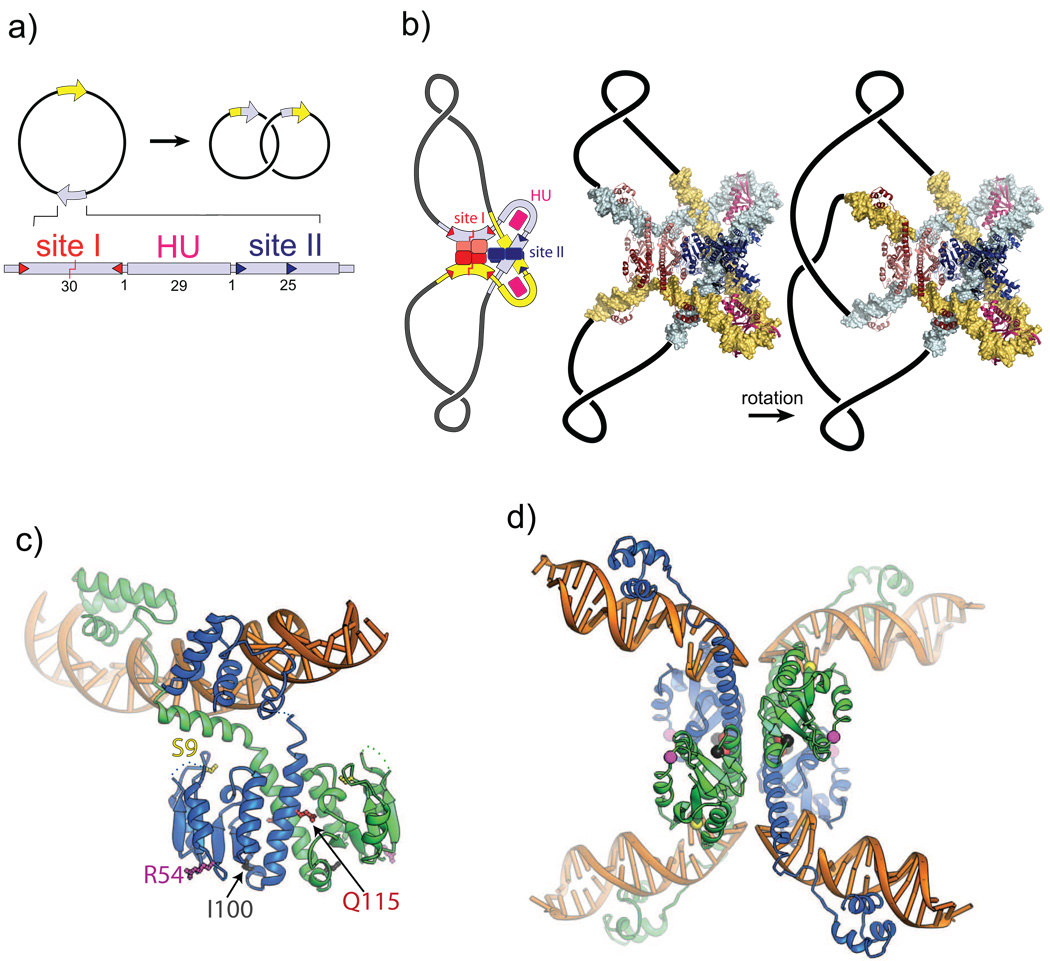

Sin is a serine recombinase encoded by the Staphylococcus aureus multi-resistance plasmid pI9789. Its presumed role in vivo is to resolve plasmid dimers to monomers, and closely related proteins are encoded by many bacterial plasmids.2–5 Sin catalyzes recombination between two 86 bp res sites arranged in a head-to-tail (direct repeat) orientation within a supercoiled plasmid (Fig. 1a).6 Each res site binds two Sin dimers and an architectural protein (in vivo, thought to be the S. aureus HU).6; 7 Two res sites interact to form a synaptic complex, which traps three (−) supercoiling nodes and contains ~175 bp DNA and ~230 kDa of protein in total (Figure 1b, c).6; 8 Double-stranded DNA breaks (DSBs) are generated at the center of one of the dimer binding sites (site I) of each res when a conserved serine residue (Ser9) from each bound protomer attacks the DNA backbone to create a covalent DNA-(5’-phosphoseryl)-Sin linkage (Figure 1d).6 The strands are thought to be exchanged by 180° rotation of two DNA-linked protomers, and religated by the attack of the free 3’OH on the phosphoseryl linkage.1; 9–12

Figure 1. Sin recombinase synaptic complex architecture and site I cleavage.

A. The Sin resolution reaction. Sin catalyzes recombination between 86 bp res sites (yellow and gray arrows) that are organized in direct repeat on a plasmid. Each res site binds two Sin dimers and an architectural protein (normally HU, but IHF can substitute). One Sin dimer binds the site I inverted repeat (small red triangles) and catalyzes cleavage at its center. A second Sin dimer binds the site II direct repeat (small blue triangles). Site II and the HU/IHF site are required for recombination by WT Sin, but not activated mutants.

B. Model of the Sin synaptic complex and strand exchange. The res sites with bound proteins assemble into a synaptic complex that traps three highly-condensed (−) supercoiling nodes. A structural model for this complex was assembled by rigid-body docking of available crystal structures: the complex of an activated γδ resolvase mutant tetramer with site I11 (1ZR2, shown in red), two IHF-DNA complexes55 (1IHF, pink), two Sin dimer -site II complexes that interact via their DNA-binding domains14 (2R0Q, blue), and two 12 bp segments of canonical B-form DNA (to visualize the exit of DNA from the complex). Following site I cleavage, it is proposed that subunit rotation within the site I – bound tetramer about a flat, hydrophobic interface rearranges the cleaved ends.

C. Structure of the Sin-site II dimer complex. The catalytic domains are related by imperfect two-fold symmetry, which is broken to accommodate the DNA binding domains’ interactions with the site II direct repeat. The dimer formed by the catalytic domains is very similar to that formed by WT γδ resolvase bound to site I (1GDT).22 Side chains that were mutated in this study are highlighted: the active site serine S9 (yellow), R54 (magenta), I100 (black), and Q115 (red).

D. Structure of an activated mutant γδ resolvase tetramer – site I complex.11 The DNA has been cleaved and the resulting 2nt 3’ overhangs pulled apart in the center. The positions of residues equivalent to those shown in part C are highlighted as colored balls.

Activity in the wild-type (WT) Sin system is strictly dependent upon the presence of the accessory proteins (HU and a second Sin dimer bound to site II of each res site).13 The structure of a synapse of two Sin dimers, each bound to a copy of site II, has been solved. Sin protomers at site II are proposed to make direct contact with protomers at site I within the full synaptic complex.14; 15 This interaction, postulated to involve Sin residues F52 and R54, could serve to bring the site I-bound dimers together and/or allosterically activate the dimers to promote catalysis.

Recently, “activated” Sin mutants have been isolated that are capable of catalyzing recombination in substrates that lack the accessory sites.13–15 These mutants generate products with a greater range of topologies than the WT system, consistent with the proposed role for the accessory sites in dictating topological specificity. However, neither the mechanism of activation nor the manner in which these mutants bypass the need for accessory proteins is clear. Structural analysis of activated mutants in the related serine recombinases Tn3 and γδ resolvase revealed large conformational changes within subunits and formation of a novel tetrameric arrangement of resolvase subunits, which is proposed to bring about strand exchange by a 'subunit rotation' mechanism (Figure 1b, d).11; 12; 16–18 Activating mutations have been found at a large number of positions, generally near inter-subunit contacts rather than near the active site. They might act by shifting the equilibrium away from the inactive dimer toward the recombination-competent tetramer.

The structural studies strongly imply that tetramer assembly is necessary for the central subunit rotation step of recombination, but the state of the enzyme at the first step of the reaction, DNA cleavage, remains unclear. Do the activating mutations (and presumably the accessory proteins of the WT synaptic complex) induce a cleavage-competent conformation of the enzyme, and if so, what is it? Alternatively, do they stabilize a post-cleavage form by suppressing religation, allowing time for the strand exchange step of recombination?

Dissection of the individual steps of serine recombinase reactions is difficult. Activating mutations allow the mechanism of Sin (or other serine recombinases) to be studied using short oligonucleotide substrates, since the need for accessory sites/proteins and DNA supercoiling has been abolished. However, it is still challenging to study the DNA cleavage step because cleaved intermediates are short-lived, and undergo ligation to form the original substrate or recombinant products. This rapid reversibility precludes measuring the rates of individual strand cleavage steps using standard substrates.

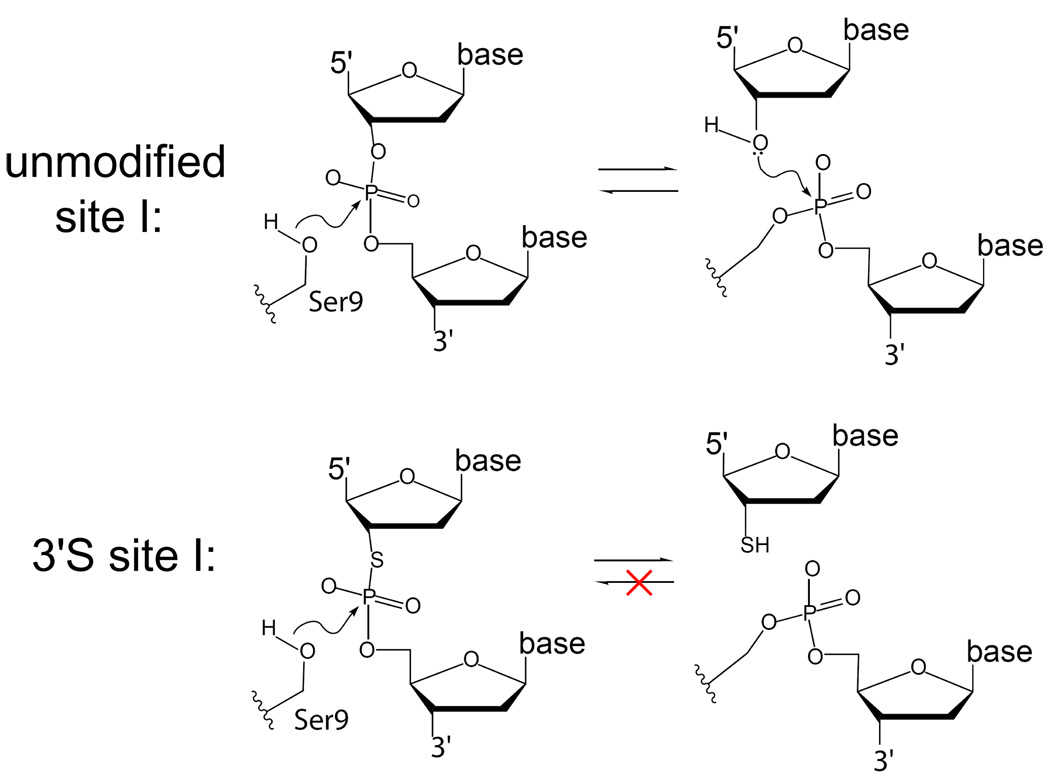

In this study, we introduce the use of 3’-bridging phosphorothiolate modifications of the DNA at the scissile positions to assay cleavage by Sin under single-turnover conditions. Cleavage by attack of the Sin Ser9 hydroxyl group at this modified phosphodiester liberates a 3’-thiol which does not support the reverse (ligation) reaction, so cleavage is rendered irreversible (Figures 2, 3).19; 20 Our results show that activating mutations in Sin favor a cleavage-competent form of the enzyme, and strongly imply that this form is a tetramer. We also find that the chemical events occurring on the complementary strands of each duplex are strongly coordinated.

Figure 2. Comparison of unmodified and 3’S site I substrates.

With unmodified substrate, reversible nucleophilic attack by Ser9 on the scissile phosphodiester produces a covalent DNA-5’-phosphoseryl-Sin intermediate and a free 3’-hydroxyl. Following rearrangement of the cleaved DNA ends within the synaptic complex, the 3’-hydroxyl of a new partner strand attacks the phosphoserine linkage to reseal the phosphodiester backbone and release the serine hydroxyl. In the 3’S-modified site I substrate, the phosphorothiolate linkage is cleaved by Ser9 to release a 3’-thiol. The thiol moiety is a very poor nucleophile in the reverse (ligation) reaction, rendering the cleavage irreversible.

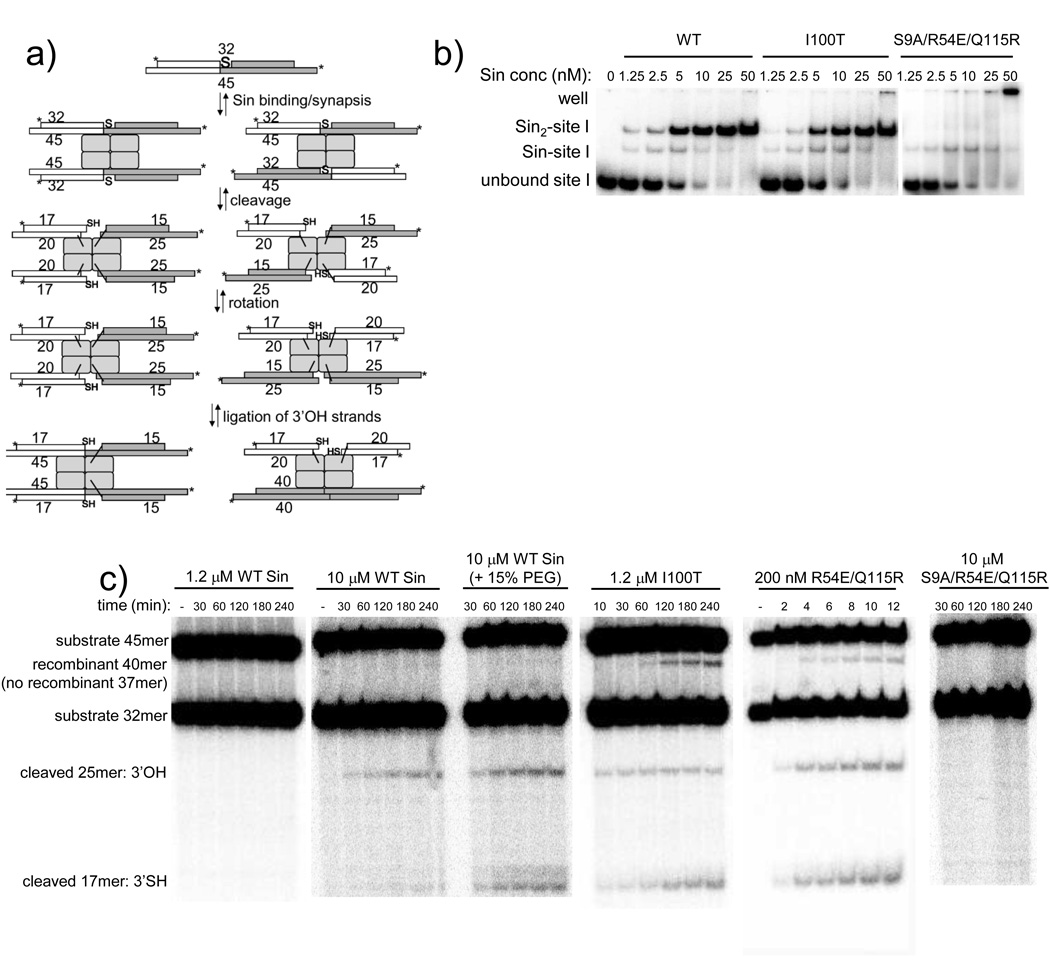

Figure 3. DNA binding and cleavage assays using a 3’S-modified duplex.

A. Overview of the expected products from a 3’S site I cleavage/recombination assay. The substrate contains a 3’S-modified 32nt strand annealed to an unmodified 45nt bottom strand, with both 5’ 32P-labelled. Sin can synapse two such duplexes in 'parallel' and 'antiparallel' alignments (left and right pathways). Cleavage generates 5’-phosphoserine intermediates and free 3’OH or 3’SH moieties, after which the cleaved ends can be realigned within the complex. Cleaved ends possessing a free 3’OH can attack the 5’-phosphoserine linkage from the adjacent protomer to re-seal the DNA backbone, whereas ends possessing a free 3’SH are unable to ligate (no 37-mer can be made). Depending upon the synapsis alignment, ligation of the unmodified strand generates a new 40mer recombinant product or a 45mer product that is identical to the substrate.

B. Sin proteins bind site I containing the 3’S modification. Binding assays were carried out in the same buffer used for cleavage assays, with ~50pM 32P-labeled site I DNA.

C. Activating mutations and mass action stimulate site I cleavage. All assays shown contained 600 nM site I, except the R54E/Q115R reaction, which contained 100 nM site I. Products were separated on denaturing 20% polyacrylamide gels. Note the differences in Sin concentrations and time points: R54E/Q115R is much more active than I100T, and WT is inactive (in this assay) except at extremely high concentration. Mutating the active site serine to alanine (S9A) completely abrogates cleavage, even in an activated background (R54E/Q115R).

RESULTS

Binding of Sin to 3’S site I

We used electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) to estimate the affinities of Sin for various site I substrates under conditions similar to those used for the cleavage/recombination assays described below. The 3'S-containing strand of site I has a central AU dinucleotide, rather than the natural AC or mutant AT as in sites that have been used before,6 because efficient synthesis required that the nucleotide adjacent to the 3'S be a dU. Binding of WT Sin to site I with AC, AT and AU top strand dinucleotides was indistinguishable, with apparent dissociation constants (Kd) of ~2.5–5 nM (data not shown), and a similar apparent Kd was observed for the modified site I containing a central AU and a 3’-bridging phosphorothiolate at the cleavage position (Fig 3a, b). Similar insensitivity to the sequence of the central dinucleotide was found for γδ resolvase,21 in agreement with the crystal structures which show no direct contacts between γδ resolvase and the DNA bases at the center of site I.22

Because EMSAs were conducted at 4°C and at relatively low protein concentrations, little or no cleavage occurs during the Sin binding assays in Fig. 3b (see cleavage results below). Both monomer- and dimer-bound species are detectable at low WT Sin concentrations, but the dimer-bound species predominates at Sin concentrations above 10 nM (Figure 3b). The extent of apparent binding cooperativity depended upon the gel buffer: less of the monomer-bound species was seen when the buffer was changed from TRIS/glycine (pH~9.4) to MOPS/NaOH (pH~7.0) (data not shown). This change in binding behavior did not appreciably affect the measured apparent dissociation constant (<5 nM). The mildly activated Sin mutant I100T bound similarly to WT Sin (Figure 3b).

To study the very activated Q115R mutant, two additional mutations were introduced; S9A and R54E. The S9A mutation simplifies the assays by removing the active site nucleophile, thus preventing DNA cleavage (Figure 3c). The single mutant S9A does not affect binding (data not shown). The R54E mutation was introduced to improve protein solubility, because purified Q115R Sin was poorly soluble at the salt concentrations required for in vitro binding and DNA cleavage assays. Arg54 is remote from the active site and DNA-binding domains, but has been implicated in contacts between site I- and site II-bound Sin protomers, which are not relevant in our assays (Figure 1c).14; 15 The R54E change probably improves solubility by decreasing aggregation of Sin protomers mediated by these interactions. S9A/R54E/Q115R binds tightly to the 3’S site I duplex, but its binding properties are different than WT and I100T Sin (Figure 3b). Very little DNA accumulates in the presumed dimer complex; instead, a shift from the monomer complex to electrophoretically unstable species (evident as non-specific smearing) and high molecular weight aggregates occurs as the S9A/R54E/Q115R Sin concentration increases. These results suggest that the Q115R mutation destabilizes the dimer, compared to WT and I100T Sin. Later experiments (Figures 7 and 8) imply that the mutant Sin tetramer is a minor species at the concentrations used here; thus the observed low-mobility complexes formed by S9A/Q115R/R54E Sin might contain loosely aggregated monomers, as well as higher-order species. Fortunately, these protein-DNA complexes, at much higher but stoichiometric concentrations, did not form large aggregates in the analytical ultracentrifuge (Figure 8; see below).

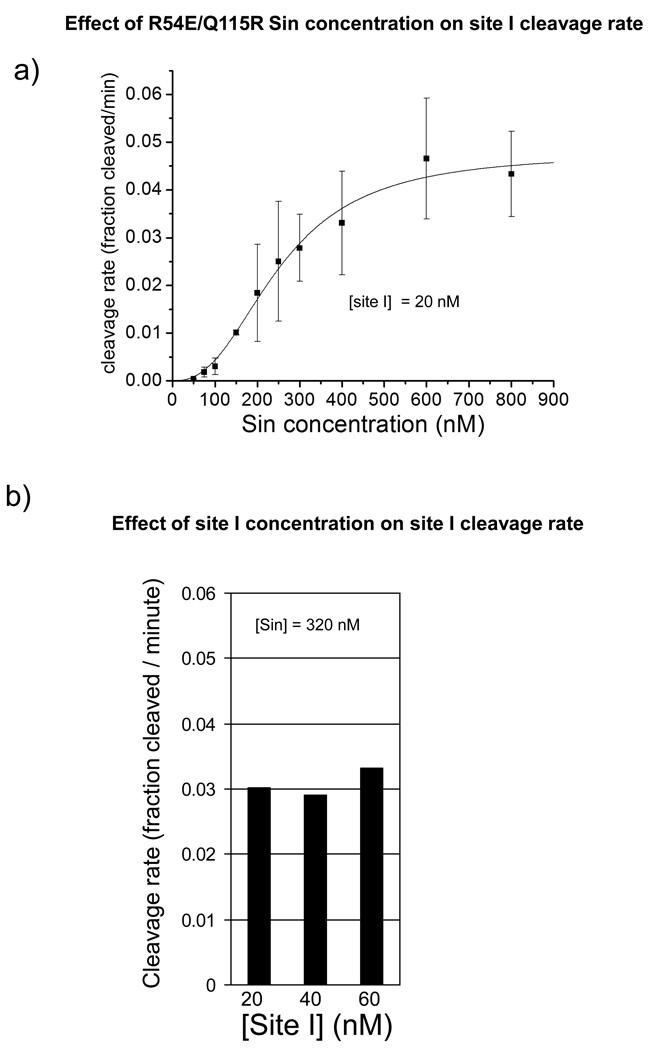

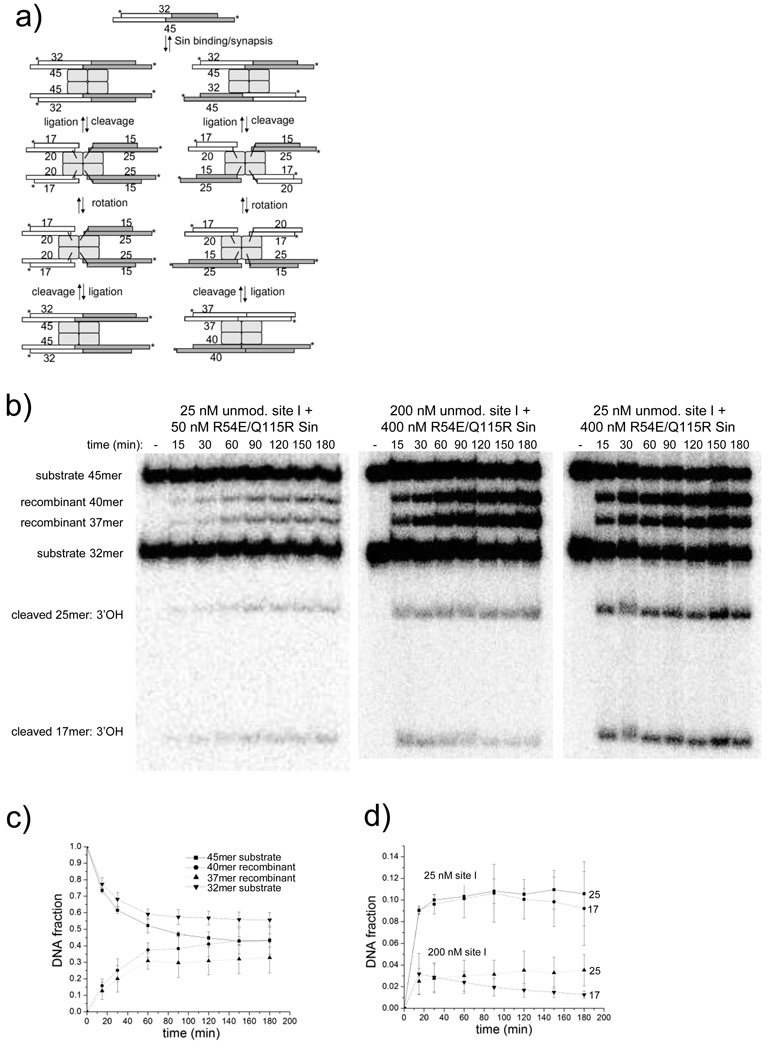

Figure 7. Effect of R54E/Q115R Sin and site I concentrations on cleavage rate.

A. Site I cleavage rate shows a sigmoidal dependence on R54E/Q115R Sin concentration. Cleavage of the 3’S modified substrate (20 nM) was measured over a wide range of Sin concentrations. For each Sin concentration, suitable early time points were used at which <10% of the substrate was converted to products and the rate was essentially linear. The mean and standard deviation of 3–5 independent measurements are shown for each calculated rate. The data points were fit with the Hill equation (see methods) to determine the maximum velocity and Hill coefficient.

B. Cleavage rate is not significantly dependent upon site I concentration. When the Sin concentration was held constant at 320 nM and the site I concentration was varied, the measured cleavage rate remained constant at a value similar to that seen in Fig 7a.

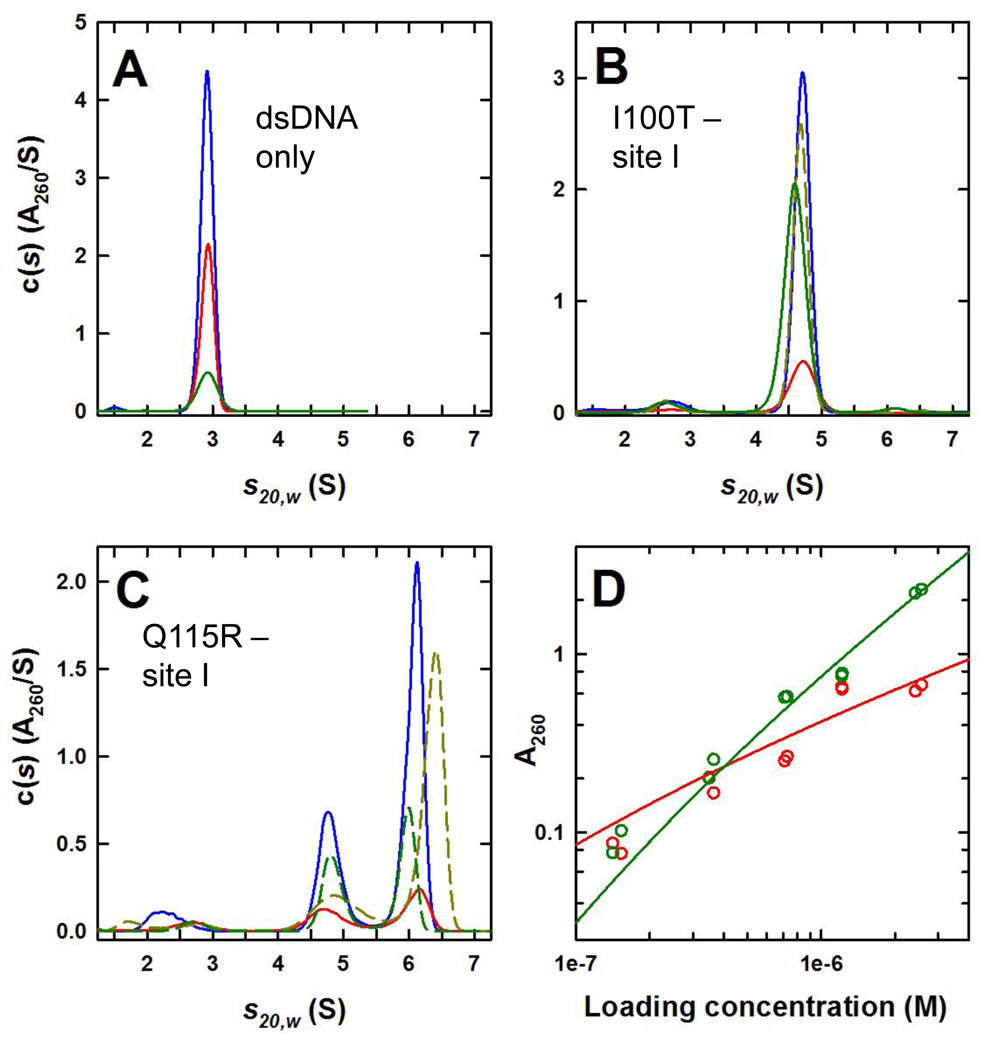

Figure 8. Sedimentation velocity analysis of I100T Sin and S9A/R54E/Q115R Sin – site I complexes.

A. The c(s) distributions obtained for site I – containing dsDNA at 0.16 (green), 0.44 (red) and 0.86 µM (blue) based on sedimentation velocity absorbance data collected at 50 krpm and 20.0°C.

B. The c(s) distributions obtained for a 2:1 I100T Sin:dsDNA mixture at 0.20 (red), 0.82 (blue), 2.9 (dashed yellow) and 5.4 µM 2:1 complex (green) based on sedimentation velocity absorbance data collected at 50 krpm and 20.0°C. At the highest concentration data were collected using 280 nm.

C. The c(s) distributions obtained for a 2:1 S9A/R54E/Q115R Sin:dsDNA mixture at 0.15 (red), 0.72 (blue), 1.2 (dashed green) and 2.4 µM 2:1 complex (dashed yellow) based on sedimentation velocity absorbance data collected at 50 krpm and 20.0°C.

D. Population isotherms based on sedimentation velocity data showing the contributions of the 2:1 (red) and 4:2 (green) S9A/R54E/Q115R:dsDNA complexes. A best fit data analysis in terms of a monomer-dimer equilibrium is depicted by the solid lines.

Activating Sin mutations and mass action both stimulate site I cleavage

The 3’S site I substrate allows us to directly measure the cleavage proficiency of WT and mutant Sin proteins. Although WT Sin is unable to recombine res sites lacking the accessory sites, it remained possible that DNA cleavage occurs, but that the equilibrium favors religation, such that detectable amounts of cleaved species or recombinants do not accumulate. In this scenario, a role of the accessory site complex might be to stabilize the site I complex in its cleaved form, allowing it to undergo strand exchange. Alternatively, WT Sin might simply be unable to cleave isolated site I DNA. Until now, distinguishing between these two possible mechanisms has not been feasible because cleavage and ligation are tightly linked. However, cleavage of the 3’S site I duplex is irreversible (see below), allowing us to directly assay the rate.

Reactions were initiated by adding Sin to samples containing site I duplex bearing 5’-(32P)-labels on both strands. Strand lengths were designed such that each potential cleavage product is a different length, and distinct recombinant products can be observed (Fig 3a). For the 3’S site I duplex, one of the strands (the 32mer) contains a 3’-phosphorothiolate at the cleavage site, while the 45mer strand contains a normal phosphodiester linkage. Sin can synapse a pair of site I substrates in two distinct orientations (Figure 3a). Strand exchange and religation from one orientation (cartooned as “parallel” in Figure 3a) will generate products that are indistinguishable from the substrate, whereas the “antiparallel” orientation will lead to different-length products.

The results of cleavage assays using the 3’S site I are shown in Figure 3c. At 1.2 µM WT Sin, no cleavage products were visible after an extended incubation, and only tiny amounts accumulated at 10 µM WT Sin (with 600 nM site I DNA in both cases). Adding a molecular crowding agent (15% PEG 5000) to the 10 µM WT Sin reaction significantly increased cleavage, suggesting that increasing the effective concentration of protein may stimulate cleavage. For WT Sin, the unmodified strand was cleaved slightly faster than the 3’S strand (Figure 3c, 10 µM WT Sin), perhaps due to steric or charge effects of the sulfur atom at the active site. This was less apparent in reactions with the activated mutants, probably due to further reaction (religation) of the unmodified strands. However, the 3’S strand is a good suicide substrate: no 37mer recombinant product was seen, confirming that Sin cannot religate the cleavage product bearing a free 3’SH (see also left panels of Figure 5a, b).

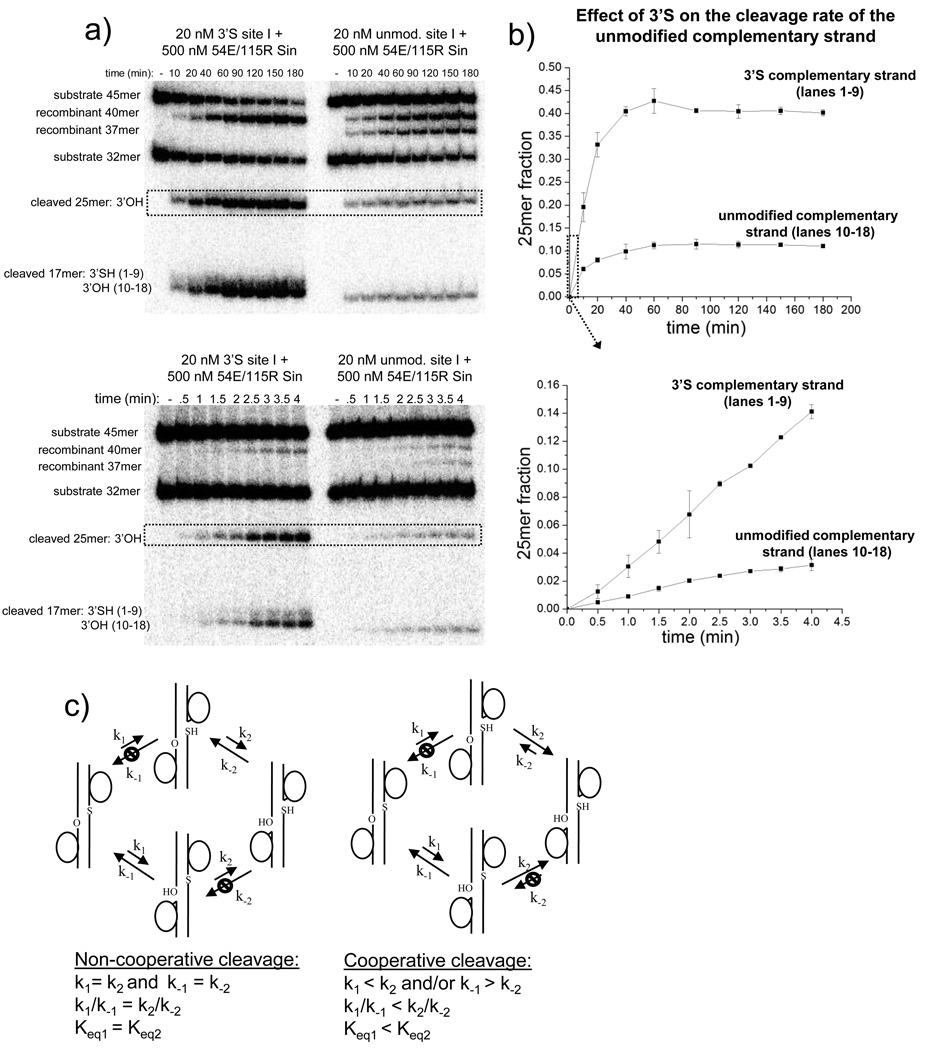

Figure 5. The presence of a 3’S on one strand of the site I duplex increases the degree of cleavage on the complementary unmodified strand.

A. Two denaturing 20% polyacrylamide gels representing the results of identical reactions are shown; only the timepoints are different. In one set of reactions (left half of gel), one substrate strand contained a 3’S, while in the other set (right half), neither substrate strand was modified. Two new recombinant products accumulate (40 and 37 nt) when both strands are unmodified, whereas only the 40-mer accumulates when one strand has a 3’S. The 25-mer resulting from cleavage of the unmodified strand is highlighted in the dotted box, and quantified to the right in part (b).

B. Plots of the fraction of the unmodified strand found in the cleaved form (dotted boxes in part a). The mean and standard deviation of 3 individual measurements are plotted; a representative gel for each plot is shown in Fig 5a. After ~40 minutes the amount of cleaved unmodified strand remains constant (upper plot). However, this apparent steady-state level is higher when the complementary strand contains a 3’S than when it is unmodified. At early timepoints (lower plot), the apparent initial rate of appearance of the 25-mer is approximately 6 times faster when the complementary strand contains a 3’S than when it is unmodified.

C. Kinetic schemes for noncooperative (left) and cooperative (right) cleavage/religation. The results in parts a and b can be explained by the right model, where cleavage of the 2nd strand is faster than that of the first, and/or its religation is slower.

The activated Sin mutants were more proficient at site I cleavage. I100T Sin accumulates a significant amount of 3’S cleavage product over several hours, whereas R54E/Q115R Sin cleaves the 3’S strand in just minutes (Figure 3c; note differences in Sin concentrations and reaction times). Treatment of the reaction products with the thiol-modifying reagent monobromobimane (Calbiochem) caused a shift in the mobility of the 17mer band, confirming the presence of a 3'SH. Mutating the nucleophilic serine residue (S9A) completely abrogates cleavage by R54E/Q115R Sin (Figure 3c).

Two additional products are visible in Figure 3c: a 25mer corresponding to cleavage of the 45nt unmodified strand, and a recombinant 40mer, formed by ligation of the 25- and 15mers (Figure 3a). The appearance of 40mer product suggests that the presence of the 3’S on one strand of a site I duplex does not prohibit the site I tetramer from undergoing strand exchange and ligating the 3’OH strand. Alternatively, the 40mer could also form if tetramers in the cleaved state were to dissociate and re-equilibrate in solution. The activated Sin mutants generate recombinant 40mers more readily than WT Sin, although the recombinant band can be seen with 10 µM WT Sin if the gels are overexposed.

Effects of stoichiometry and concentration

When I100T and R54E/Q115R Sin were tested with unmodified substrates, both recombinant products were seen (40 and 37nt), as well as the cleavage products of each strand (25 and 17nt; Figure 4a, b, and data not shown). For both I100T and R54E/Q115R, the two recombinant products appeared at similar rates, suggesting that there is no unexpected bias favoring cleavage and ligation of one strand over the other (Figure 4b and data not shown). At a relatively high concentration (400 nM) of R54E/Q115R Sin, the system appeared to approach an equilibrium. For the 45mer substrate strand, the products of recombination from each of the two possible synapsis orientations were present in approximately equal amounts ([45mer]≈[40mer]). Similarly, equal amounts of 37mer and 32mer were expected from the 32mer substrate strand, but the final concentration of the 37mer is less than that of the 32mer. This could be explained by an ~15% excess of labeled 32- over 45-mer in our annealing reactions, despite the duplexes being checked for excess single strand by native gel electrophoresis. For both strands, the amount of cleaved intermediate remained stable throughout the reaction course.

Figure 4. Cleavage of unmodified site I by R54E/Q115R Sin.

A. The reaction is the same as that shown in Figure 3a, except that neither substrate strand is modified. Depending upon the synapsis alignment, two sets of recombinant products can result: one identical to the substrates (32- and 45 nt) and one different (37- and 40 nt). Multiple rounds of cleavage and religation are possible.

B. Effects of protein concentration and protein: DNA ratio.

Reactions of R54E/Q115R were carried out at 50 and 400nM protein, with either very limiting or stoichiometric [DNA]. To better visualize differences in the distribution of species, the amount of 32P-labeled site I in each experiment was kept constant and the amount of non-32P-labeled site I was varied. Products were separated on denaturing 20% polyacrylamide gels.

C. Plot of the fraction of DNA in each substrate and product form for the 400 nM R54E/Q115R Sin + 25 nM unmodified site I reaction. The plot shows the mean and standard deviation of 3 independent experiments (the gel for one of which is shown in Fig. 4b, right panel). Results for the 400 nM protein/200nM DNA reactions were similar.

D. Comparison of the fraction of DNA in each of the cleaved forms for the reactions of R54E/Q115R Sin (400 nM) with 25 nM or 200 nM site I. The fraction of DNA in the cleaved form is significantly higher when [Sin]≫[site I] than when [Sin]:[site I] is stoichiometric. Data are represented as the mean and standard deviation of 2 independent measurements.

The fraction of site I in the cleaved form depends on the ratio of R54E/Q115R Sin to site I. Significantly more cleaved DNA was present when Sin was in large excess over site I DNA (Figure 4b, d). The rate at which the reaction approached equilibrium increased significantly as the Sin concentration increased (Figure 4b). For a given Sin to site I ratio, the percentage of each strand in the cleaved form (25-mer and 17-mer) was similar, suggesting that cleavage/ligation of complementary strands is highly concerted.

A possible explanation for the larger fraction of cleaved DNA seen at high Sin to site I ratios is that many complexes may contain a Sin tetramer bound to a single site I, rather than two site Is as expected at lower ratios. If these singly-bound tetramers undergo cleavage followed by subunit rotation, the first 180° rotation would align the broken ends with empty DNA-binding sites, and a second 180° rotation (in either direction) would be required before two broken ends could be religated. If subunit rotation is slow relative to religation, this would lead to singly-bound tetramers spending more time in the cleaved form than doubly-bound ones. Alternatively, if the cleaved Sin-site I complexes can dissociate and reassociate, the probability of one cleaved end pairing with another for religation would be lower at higher Sin to site I ratios. This effect would be compounded if Sin tetramers bound to a single site I duplex were inherently less stable than tetramers bound to two duplexes.

Cleavage cooperativity between strands of site I

Because the 3’S site I contains an unmodified linkage at the scissile position of the complementary strand, the coordination of cleavage events on complementary strands of the site I duplex can be investigated. Figure 5 shows that when the 3’S is present, there is more cleavage of the unmodified strand than when both strands are unmodified. Cleavage of the 3'S strand therefore appears to strongly bias the complementary strand towards the cleaved form, even though it is chemically competent to undergo ligation.

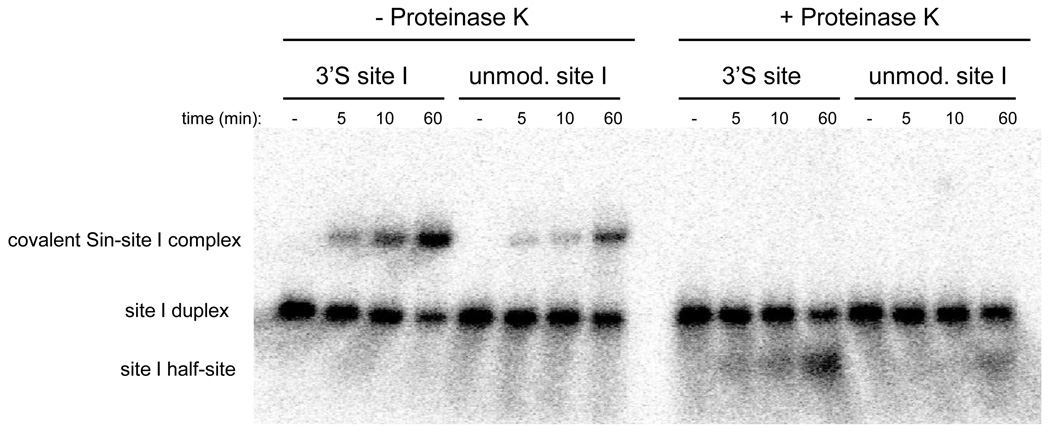

To further investigate the cooperativity of cleavage, the products of a reaction with R54E/Q115R Sin were separated by SDS-PAGE. Figure 6 shows a single species that migrates more slowly than the substrate duplex. Upon treatment with proteinase K prior to electrophoresis, the slow species is replaced by a single species that migrates faster than the site I duplex. We conclude that the slow species is a half-site covalently linked to a Sin monomer. There is no evidence on the gel for the predicted product of single-strand cleavage, a full-length site I with a covalently attached Sin subunit.

Figure 6.

Cleavage events on complementary strands of site I are coordinated. To test whether the cleavage products are primarily DSBs, SSBs, or a mixture of both, 20nM 5’-(32P)-labeled 3’S or unmodified site I was incubated with 500 nM R54E/Q115R Sin and the products were separated by SDS-PAGE. A single species that migrates more slowly than the site I duplex is present, which presumably represents a covalent Sin-site I complex. When the same reaction is digested with proteinase K prior to SDS-PAGE, a single species that is smaller than the site I duplex is present. A singly nicked duplex should not migrate faster than the intact one; thus this species must be a half-site resulting from a DSB.

Collectively, these experiments show that the vast majority of cleaved site I duplexes are cleaved on both strands. In the case of the suicide substrate, irreversible cleavage of the 3’S strand may cause the complementary unmodified strand to undergo cleavage more rapidly, or alternatively, be ligated more slowly (Figure 5a, b). However, even when both site I strands are unmodified, there appears to be a strong preference for DSBs over SSBs (Figure 6). Close communication between Sin protomers bound to the site I duplex may help to coordinate the cleavage events on complementary strands, thereby ensuring that unproductive single-stranded breaks are avoided.

Cleavage rate is strongly dependent upon Sin concentration

Because the 3’SH liberated upon cleavage of the 3’S site I duplex does not act as a nucleophile in the reverse (ligation) reaction (Figure 3c), accumulation of the 17-mer product is an accurate measure of the forward cleavage rate. We measured the initial cleavage rate for R54E/Q115R Sin, the most active mutant tested to date, over a large range of protein concentrations (Figure 7a). The 3’S site I concentration was kept constant at 20 nM throughout the assays. Because R54E/Q115R Sin binds site I tightly (Kd, apparent ~5 nM) (Fig 3b), nearly all of the 3’S substrate should be bound at the Sin concentrations tested in this assay.

The site I cleavage rate showed a sigmoidal dependence on Sin concentration (Fig 7a), reaching a maximum at ~5% of the 3’S site I per minute at R54E/Q115R Sin concentrations greater than 600 nM. If the cleavage reaction were a simple first-order process occurring within a complex of a single site I and Sin, regardless of oligomeric state,, one would expect the rate to remain constant as more excess protein is added. However, at Sin concentrations between ~100–500 nM, the cleavage rate depended steeply on concentration, implying that the rate is dependent upon the protein’s oligomerization state. In the case of R54E/Q115R Sin, this likely corresponds to the transition from inactive monomers and/or dimers to active tetramers, although the physical basis for the measured Hill coefficient value of 2.5 is unclear; the uncomplexed Sin added to the reactions is probably not purely monomeric and the effect of DNA on the oligomer equilibria has not yet been thoroughly investigated.

We also investigated the effect of site I concentration on cleavage rate, with constant Sin concentration of 320 nM, which is within the steep portion of the curve in Figure 7a where one might expect any effect of site I on protein oligomerization to be most noticeable (Figure 7b). The cleavage rate (measured as % of site I cleaved per minute) was essentially constant across a 3-fold range of site I concentrations. These results imply that a Sin tetramer bound to only one DNA duplex is active. If activity strictly required not only protein tetramerization but also the presence of two bound duplexes per tetramer, a 3-fold increase in the DNA concentration would lead to a >2-fold increase in the cleavage rate. Assuming for simplicity’s sake that all the input DNA is bound by protein, using Kd = [Sin2DNA]2/ [Sin4DNA2] = 450, then if [DNA] = 20 nm, [Sin2DNA] = 18.5 nM and [Sin4DNA2] = 0.76 nM, and 3.8% of DNA would be in the doubly-bound tetramer form, whereas if [DNA] = 60 nm, [Sin2DNA] = 49.2 nM and [Sin4DNA2] = 5.38 nM, and 9% of the DNA would be in the doubly-bound form. Thus increasing the [DNA] 3-fold would increase the % of the DNA that is in the doubly bound tetramer by ~2.4-fold, and if this is the only active form, the cleavage rate, expressed in % per minute, would increase similarly, which, given the error bars for similar experiments in figure 7a, we feel we would have readily detected. Thus despite the caveats that there may be small amounts of unbound DNA remaining, and that we cannot rule out smaller effects of the number of DNAs bound to a tetramer on its activity, we feel that the singly-bound tetramer must be capable of DNA cleavage, and that the increase in rate seen in figure 7a is indeed at least largely due to the increase in protein concentration driving tetramerization. This idea is further supported by the AUC work described below showing that Sin R54E/Q115R can tetramerize in the absence of DNA.

Analysis of Sin oligomerization state

We used analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC) to further characterize the oligomerization state of the Sin- site I complexes as well as the isolated proteins and DNA. The first set of AUC experiments examined the unmodified site I duplex alone, with sedimentation equilibrium and velocity experiments each carried out at three loading concentrations. Sedimentation equilibrium data were well modeled in terms of a single non-interacting discrete species returning a buoyant molecular mass of 11.25 ± 0.15 kDa (Figure 8a and Supplementary Figure 1). Based on the calculated mass of 32.001 kDa, an effective partial specific volume (ϕ’) of 0.639 ± 0.005 cm3 g−1 is obtained. Even though this value is larger than expected, effective partial specific volumes for nucleic acids are known to depend strongly on the buffer conditions.23 Sedimentation velocity data were also consistent with the presence of a single discrete species having a average s20,w of 2.915 ± 0.005 S. (Figure 8a). An analysis in terms of a continuous c(s) returns a molecular mass of 31.9 ± 0.4 kDa (n = 1.00 ± 0.01) and a frictional ratio f/fo of 1.73 consistent with the elongated shape expected for the dsDNA.

The oligomeric behavior of the mildly activated I100T Sin with site I was tested by sedimentation velocity experiments carried out at various loading concentrations (with a Sin to site I ratio of 2:1). The results of the SV experiments indicate the presence of a major species having a s20,w of 4.69 ± 0.015 S. (Figure 8B). The c(s) analysis for data collected at 0.20 through to 2.9 µM returned an average molecular mass of 79 ± 2 kDa for this species, consistent with the expected molecular weight of a Sin dimer bound to a single site I duplex (Mcalc = 80.5 kDa). This complex accounts for 93% of the loading absorbance with a minor species at 2.6 S contributing to the remainder of the signal. At these concentrations there was no evidence for higher order complexes; however, possible evidence for a larger complex is noted at 5.4 µM where a 6.0 S species representing 2% of the loading absorbance is observed (Figure 8b). This species may represent a small amount of I100T synaptic tetramer forming at higher loading concentrations. Similar experiments were carried out on mixtures of the highly activated S9A/R54E/Q115R Sin with site I and these showed the presence of essentially two species at 4.8 S and 6.0 S, likely representing 2:1 and 4:2 Sin-site I complexes, respectively (Figure 8c). As the loading concentration increases, the Sin site I dimer complex appears to undergo self-association to form the synaptic tetramer. Accordingly, the fractional populations of the 2:1 and 4:2 species obtained from the c(s) profiles were modeled in terms of a reversible “monomer-dimer” self-association to obtain a “dimerization” Kd of 0.40 ± 0.13 µM (Figure 8d). An essentially identical value, Kd = 0.45 ± 0.14 µM, was obtained by sedimentation equilibrium (Supplementary Figure 2).

For comparison with the concentration dependence of the cleavage rate in Figure 7a, the most intuitive figure is the loading concentration at which ~50% of the Sin protein is in the tetrameric form. Given that the “monomer” in the formalism used to calculate Kd corresponds to the 2:1 protein:DNA species, and that each real tetramer contains twice as much protein as each real dimer, the AUC work predicts that ~50% of the Sin protein should be tetrameric at 800–900 nM. This is somewhat higher than the steepest part of the curve in Figure 7a, but the agreement is remarkably good given that the two completely different experiments were carried out under different buffer conditions (e.g. different stoichiometries, 200mM NaCl in the kinetic experiments vs. 200mM (NH4)2SO4 in the AUC; the higher ionic strength of the (NH4)2SO4 being needed for solubility at the higher concentrations used in the AUC work). This strongly supports a model requiring formation of a site I – bound tetramer prior to DNA cleavage.

Sedimentation velocity (SV) data were also collected for the WT and mutant Sin proteins in the absence of DNA, all at 50 µM concentration. For each sample, absorbance data were collected at 280 nm and fit with a continuous size distribution model (c(s)) using SEDFIT (Supplemental Figure 3a).24 The sedimentation profiles of WT Sin and the mildly activated I100T Sin differed from that of the highly activated R54E/Q115R Sin (with the additional active site S9A mutation). The numerical solution of the Lamm equation was used to predict the molecular mass of each sample. WT and I100T Sin have predicted molecular masses of 40 and 39 kDa, respectively, which is in reasonable agreement with the expected mass of a His6-tagged Sin dimer (48 kDa). The experimental molecular mass of the S9A/R54E/Q115R mutant was 98.5 kDa, close to the expected mass of a Sin tetramer (96 kDa). The calculated frictional ratios (1.88 for WT, 1.79 for I100T, and 2.55 for S9A/R54E/Q115R) imply that all 3 proteins adopt an elongated shape in solution, as was also observed for Tn3 resolvase.25 This probably reflects the long, flexible linker between the catalytic and DNA-binding domains of these proteins (Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

Bridging phosphorothiolates as suicide substrates

DNA oligonucleotides containing phosphorothiolate modifications can be very useful in the study of catalysis by DNA-cutting enzymes and have notable advantages over suicide substrates containing backbone nicks or modified bases.19; 20 5’-bridging phosphorothiolate-modified substrates have been used extensively to study DNA cleavage by Type IB topoisomerases and tyrosine recombinases, which form a covalent 3’-phosphotyrosine intermediate and liberate the 5’-hydroxyl.26–31 More recently, 3’-bridging phosphorothiolate-modified substrates have been used to study DNA cleavage by enzymes that form a covalent 5’-phosphotyrosine intermediate and release the 3’-hydroxyl.20; 32

Here, we introduce the use of 3’-bridging phosphorothiolate-modified DNA to study catalysis by a serine recombinase. It fulfilled the requirements of a good suicide substrate in our reactions: it did not adversely affect protein binding, it was readily cleaved by Sin to form a covalent DNA-(5’-phosphoseryl)-Sin intermediate and a free 3’-thiol, and it did not undergo religation to form recombinant products. This modification may affect the absolute cleavage rate: in the slowest reactions in figure 3c, the 3’SH-containing product accumulated more slowly than the 3’OH-containing product. In faster reactions, this effect is probably masked by religation of the unmodified product. However, this suicide substrate allowed accurate comparison of relative Sin-mediated DNA cleavage rates under a variety of single-turnover conditions.

Tetramerization is required for catalytic activity

Structural and biochemical studies have shown that the catalytic domains of serine recombinases can mediate two different oligomerization states: dimeric and tetrameric. Formation of the tetramer requires not just docking of two dimers but a major remodeling of their protein – protein interfaces, and intramolecular repacking of the C-terminal portion of each catalytic domain. Unfortunately, none of the available structures provide a good model for the fully assembled active site: that of the WT γδ resolvase dimer bound to site I places the nucleophilic serines >13Å from the scissile phosphate groups, while that of an activated γδ resolvase tetramer is in a post-cleavage state, with the 3’ OH groups similarly distant from the phosphoserine linkages.11; 16; 22 Thus the question remained: is tetramerization required for the chemical steps of DNA cleavage and religation, or simply to mediate the physical exchange of broken DNA ends? The latter is true for tyrosine site-specific recombinases such as Flp that use different mechanisms to accomplish similar genetic rearrangements.33–35 However, the data reported here imply that Sin requires tetramerization even for initial DNA cleavage activity.

For all three Sin variants tested, cleavage activity depended strongly on protein concentration, implying an oligomerization-dependent activation (figures 1 and 7, and additional data not shown for I100T). Combining the 3’S suicide substrate and the highly activating Q115R mutation allowed us to directly measure the initial cleavage rate as a function of protein concentration. The sigmoidal shape of the resulting curve in figure 7 implies that a critical oligomerization occurs between ~200–500nM Sin protein. Analytical ultracentrifugation experiments on Sin – site I complexes containing the Q115R mutation showed the presence of both DNA-bound dimers and tetramers, with ~50% of the sample in the tetrameric form at 800 – 900 nM Sin protein. Even though the AUC experiments were carried out under different conditions, including 200mM (NH4)2SO4 rather than 200 mM NaCl and stoichiometries such that all of the Sin was bound to DNA, the value of 800 – 900 nM Sin agrees fairly well with the inflection point seen in the kinetic experiments. The combined data sets provide strong evidence that only the tetrameric species is catalytically active.

Our more qualitative data for WT Sin and mildly activated I100T further support this idea. WT Sin was capable of cleaving isolated site I substrates, but only after prolonged incubation at the highest protein concentration tested. That activity probably reflects transient tetramerization of a small percentage of the protein, which appeared to be entirely dimeric in the ultracentrifuge. I100T was active at somewhat lower concentrations, corresponding to a trace of tetramer detected by sedimentation velocity.

Oligomerization state as a regulatory mechanism

The conformational equilibrium between dimers and tetramers is used to regulate activity. The inactive dimeric species is so strongly favored by the WT serine resolvases that WT tetramers have never been directly observed. This corresponds with the fact that these proteins are normally active only within the context of the full synaptosome. The synaptosome must therefore activate two site I – bound dimers by triggering at least transient tetramerization. In part, it may simply apply mass action: In our model of the Sin synaptosome, the subcomplex formed by the accessory proteins brings the two site I-bound dimers so close together that the local concentration is tens of millimolar. It also aligns the two sites for optimal interaction. Finally, there is evidence for functionally important protein-protein contacts between the site I- and accessory site-bound proteins in the Sin and γδ resolvase synaptosomes.15; 36; 37 These may simply help to position the site I-bound protomers, but by closing a small DNA loop, they may also exert a strain that destabilizes the dimer conformation.

The activating mutations, like the synaptosome, appear to act by tipping the balance between dimers and tetramers. Such mutations generally map to the region that must repack during the dimer – tetramer transition, suggesting that they could destabilize the inactive dimer or stabilize the tetramer1; 11; 15; 38. Q115R, the most activating mutation studied here, appears to do both: in the WT Sin dimer, this residue interacts with the opposite protomer, whereas in a preliminary structure of the Q115R Sin tetramer, those contacts are broken and it forms new, potentially stabilizing interactions with a different protomer (P.A.R. and Ross Keenholtz, unpublished data).14 In gel mobility shift experiments Q115R also forms less dimer than WT but more tetramer (Figure 3 and Figure 6 of Rowland et al. (2009), where different experimental conditions were used to detect synaptic tetramers).15

Although tetramerization is required for cleavage, our data and others’ underscore that cleavage doesn’t occur immediately upon synapsis. Even at high R54E/Q115R concentrations where the vast majority of site I duplexes are presumed to be bound to Sin tetramers, only ~5% of substrate is cleaved per minute. Activated mutants of other serine recombinases rapidly undergo synapsis to form stable tetramers but accumulate cleavage products more slowly, suggesting that a significant portion of tetramers are bound to a pair of uncleaved sites.15; 39; 40 One Sin mutant, T77I, forms a stable tetramer with a conformation that appears to be distinct from the tetrameric conformation of mutants that promote cleavage more efficiently.15 These results imply that an additional conformational change might be required to promote site I cleavage within recombinase tetramers. The activating mutations may act by promoting this transition as well as by altering the overall monomer-dimer-tetramer equilibrium. In the WT case, promoting this transition may represent another role for the full synaptic complex.

Coordination of Cleavage Events

Previous work with γδ and Tn3 resolvases has shown that cleavage events on complementary strands are tightly, but not completely, coupled 41; 42. In our Sin experiments, trapping one strand in the cleaved form with the 3’S strongly biased the unmodified paired strand toward the cleaved form as well. Both the apparent initial cleavage rate and the steady-state level of cleaved DNA for the unmodified strand were higher when the complementary strand had a 3’S (Figure 5). The more direct experiment in figure 6, and those of Rowland et al. showed that even in the absence of the non-ligatable 3’S, the vast majority of cleavage products harbored double-rather than single-strand breaks.15 Such coordination would bias the system away from unproductive single-strand breaks toward either intact DNA or recombination-competent double strand breaks.

The amount of cleaved intermediate seen varied with the experimental conditions, even in the absence of the 3’S modification. One variable was the activating mutation used: more cleaved DNA was seen with Q115R than with I100T (Figure 3c and data not shown). However, their different propensities to tetramerize made unambiguous comparisons difficult. The second important variable was the protein : DNA ratio. A higher percentage of the DNA was found as cleaved intermediate when the protein was in excess over DNA than when the two were present in a stoichiometric ratio, regardless of the absolute concentration (Figure 4). This result, and also the concentration-dependence of suicide substrate cleavage shown in Figure 7a and b, strongly suggests that a Sin tetramer may be catalytically active when bound to only a single site I.

A lack of coordination between the two halves of the tetramer could be dangerous, leading to a double-strand break in the absence of a recombination partner. However, for the isolated WT protein, tetramers were undetectable even at 50 µM. Thus at more physiologically relevant concentrations, even transient tetramerization of WT Sin must depend on two site I – bound dimers being brought together by the accessory sites.

Implications for other serine recombinases

The overall scheme supported by our data, in which inactive dimers must somehow be provoked into undergoing conformational changes to form active tetramers, is probably used by many other family members. Maintaining the WT enzyme as an inactive dimer until it is incorporated into the proper complex can prevent the formation of dangerous, unproductive double strand breaks as well as inappropriate recombination reactions that would produce unwanted products. This scheme is well-supported by studies of Hin invertase and Tn3 and γδ resolvases, although the details of their interactions with accessory sites are not well understood.11; 18; 38; 40; 43; 44 Large serine recombinases such as the ϕC31 and Bxb1 integrases that bind only one recombinase dimer per recombination site necessarily use different and less clear mechanisms to dictate synapsis orientation and promote cleavage activation, but similar processes might nevertheless be involved.35; 45; 46 The dimer-binding sites for the large serine recombinases are larger and less symmetric than Sin res site I. Only certain pairs can be synapsed by the recombinase, and it may be that binding to these sites selectively destabilizes the dimer, favoring active tetramer formation. Although the mechanisms may vary, in all systems maintenance of genomic integrity depends upon closely regulating DNA strand cleavage and exchange.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthesis of 3’S site I substrate

Oligodeoxynucleotides were synthesized (one-micromole scale) on a Millipore Expedite Nucleic Acid Synthesis system. 5´-O-Monomethoxytrityl-2´-deoxy-3´-thiouridine 3´-S-phosphoramidite was prepared as described47 and used to synthesize the 32mer substrate containing 3´-S-dU: 5´-TTGTGAAATTTGGGTA(dU)sACCCTAATCATACAA via solid phase synthesis and manual coupling at the modified position essentially as described.48–50

Site I duplexes

Site I oligonucleotides not containing the 3’S dU were purchased from IDT (Coralville, IA). The sequence of the 32mer and 45mer annealed to create the site I duplexes used in binding and cleavage assays are: 5’-TTGTGAAATTTGGGTAXACCCTAATCATAC AA-3’ where X is 3’S dU or unmodified dU/dT/dC and 5’-TTGTTGCATTGTATGATTAGGGTYTACCCAAATTTCACAACGCGT-3’ where Y is dA when basepaired with dU/dT and dG when basepaired with dC. Annealing was performed in 100 mM NaCl by slow-cooling from 85°C. Because site I contains a near-perfect inverted repeat, proper annealing was confirmed by native gel electrophoresis.

Sin proteins

WT Sin and activated mutants were purified as described previously.14 Briefly, Rosetta (DE3) pLysS cells were grown to OD600~0.5, induced with 0.5 mM IPTG, then grown for an additional 3 hours before being harvested by centrifugation. Cell pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (25 mM TRIS (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM EDTA, 10 mM β-ME, and protease inhibitor cocktail (1 tablet/50 ml, Boehringer-Ingelheim)), treated with lysozyme (20 µg/ml), sonicated, and then centrifuged. The pellet was resuspended in buffer B (lysis buffer except 400 mM NaCl), centrifuged, resuspended in buffer C (lysis buffer plus 1% Triton X-100), and centrifuged again. This pellet was resuspended in 25 mM TRIS (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 6 M urea and centrifuged. The supernatant was filtered (0.22 µm), loaded on an SP column (all columns from Amersham), and eluted with NaCl. Pooled fractions were dialyzed and loaded on a Hi-Trap chelating column and eluted with imidazole. Pooled fractions from the chelating column were dialyzed and loaded on a MonoS column and eluted with NaCl. Pooled fractions containing pure, full-length Sin were dialyzed into 25 mM TRIS (pH 7.5), 400 mM (NH4)2SO4, 20% glycerol and stored at −80°C. For binding and cleavage assays, proteins were diluted in 10 mM TRIS (pH 8.0), 1 M NaCl, 5% glycerol, and 100 µg/ml BSA (Fischer).

Cleavage assays

Gel-purified oligonuclotides were purchased from IDT. 5’-32P-labelled site I duplexes for cleavage reactions were prepared by annealing known amounts of unlabelled 32mer and 45mer strands in the presence of trace amounts of labeled 32mer and 45mer. Cleavage assays were conducted at room temperature in buffer containing 50 mM TRIS (pH 8.0), 200 mM NaCl (from added protein), 7% glycerol, 10 mM DTT, 0.01% Triton X100, 2 mM EDTA, and 10 µg/ml poly(dI-dC). To stop the reaction, aliquots were removed to tubes containing SDS (1% final concentration) and heated at 95°C for 1 minute. Proteinase K was then added to ~1 mg/ml and the samples were incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C. An equal volume of formamide was added and the samples were heated at 95°C for 1 minute and then loaded on 20% denaturing polyacrylamide (19:1 acrylamide:bis-acrylamide) gels and run for 2 hours at 2000 V. Gels were visualized using Fuji phosphoimager screens scanned with a Molecular Dynamics phosphoimager. Band intensities were quantified using the Quantity One software package (Bio-Rad). The fraction cleaved was calculated by dividing the amount of each strand in the cleaved form by the total amount of cleaved, uncleaved, and recombined DNA (recombined DNA is only present for strands lacking the 3’S). Cleavage rates were determined by plotting the fraction of cleaved DNA as a function of time and fitting the plot with a straight line. To ensure that initial rates were being calculated, timepoints were limited to the first ~10% of product formation. To quantify the relationship between Sin concentration and cleavage rate in Figure 7, the data was fit with the following equation:

where Vmax is the maximum velocity of the reaction, c is the Sin concentration, Km is formally the Michaelis constant, and n is the Hill coefficient.

SDS-PAGE analysis of cleavage products

Cleavage reactions were conducted identically to those described above, except that only the 32mer strand of the site I duplex was 5’-(32P)-labeled. The DNA duplexes were 20nM and the protein 500nM. Reactions were stopped by adding 1% SDS and treating one half of the reaction mixture with 1 mg/ml proteinase K for 30 minutes at 37°C. Samples were then loaded on 7.5% polyacrylamide (29:1 acrylamide:bis-acrylamide) gels and run at 125 V for 2 hours at 4°C in a 0.5X TBE/1X SDS buffer. Gels were visualized using Fuji phosphoimager screens scanned with a Molecular Dynamics phosphoimager.

Binding assays

Binding assays were conducted in the same buffer as was used for the cleavage assays. 32P-labelled site I duplexes (~50 pM) and 10 ug/ml poly-dI/dC (as carrier DNA) were incubated with increasing amounts of Sin at room temperature for 15 minutes, then at 4°C for 15 minutes. The samples were loaded on 8% polyacrylamide gels (29:1 acrylamide:bis-acrylamide) containing 50 mM TRIS/10 mM glycine (pH ~9.4) and electrophoresed at ~6 V/cm for 2 hours at 4°C. Gel visualization and band intensity calculations were carried out as described above. Because the DNA concentration was well below Kd, [protein]free≈[protein]total and the Kd,app could be calculated from the following relationship:

where θ is the fraction of bound DNA and [P]t is the total protein concentration.

Analytical Ultracentrifugation

dsDNA sample preparation

A 52-mer dsDNA having the following sequence GCCTAGTTCTTTGTGAAATTTGGGTATACCCTAATCATACAAGCTTGATCTG was prepared by annealing the corresponding complementary ssDNA oligomers. The product was purified on a 10% 29:1 acrylamide:bis-acrylamide TBE gel, extracted and ethanol precipitated using standard protocols. The purified product was resuspended in a buffer containing 0.2M (NH4)2SO4 and 0.025M Tris.HCl (pH 7.4) such that the final concentration was 303 µM. Molecular masses and extinction coefficients of the ssDNA oligomers were determined based on the DNA sequence (http://www.idtdna.com/analyzer/Applications/OligoAnalyzer/Default.aspx). A diluted sample of dsDNA having an A260 of 0.978 absorbance units was heated to 95°C and found to have an A260 of 1.031. This corresponds to the absorbance of an equimolar mixture of the ssDNA oligomers, from which an extinction coefficient of 967,090 M−1 cm−1 is determined for the dsDNA.

dsDNA and Sin-1 complex preparation

2.23 µL of a 303 µM dsDNA stock solution (676 pmol) was made up to 50 µL with 0.2M (NH4)2SO4 and 0.025M Tris.HCl (pH 7.4). Two molar equivalents of I100T Sin (5.5 µL of a 245 µM stock, A280 = 2.56) or S9A/R54E/Q115R Sin (2.0 µL of a 675 µM stock, A280 = 7.04) were then added and the solution diluted as required with 0.2M (NH4)2SO4 and 0.025M Tris.HCl (pH 7.4).

Sedimentation velocity

Sedimentation velocity experiments were conducted at 20.0°C on a Beckman Coulter ProteomeLab XL-I analytical ultracentrifuge. Samples of dsDNA (loading volume of 400 µL) were analyzed at loading concentrations of 0.16, 0.44 and 0.86 µM and a rotor speed of 50 krpm. 80 scans were collected at 5.3 minute intervals with absorbance data collected as single measurements at 260 nm using a radial spacing of 0.003 cm. Data were analyzed in SEDFIT 11.71 in terms of a continuous c(s) distribution covering an s range of 0.05 – 5.05 S with a resolution of 100 and a confidence level (F-ratio) of 0.68.51 Excellent fits were obtained with r.m.s.d. values of 0.0038 – 0.0056 absorbance units. Equally good fits were obtained when data were analyzed in terms of a single non-interacting discrete species. Solution densities (ρ) and viscosities (η) were calculated based on the solvent composition using SEDNTERP 1.09; the partial specific volume (ν) was obtained from sedimentation equilibrium experiments (software downloaded from Philo, J. http://www.jphilo.mailway.com/).52 Samples of a 2:1 mixture of I100T Sin and dsDNA were studied at loading concentrations of 0.20, 0.40 and 0.82 µM 2:1 complex in 12 mm path length 2 channel centerpiece cells (loading volume of 400 µL) and 0.65, 1.4, 2.9 and 5.4 µM 2:1 complex in 3 mm path length 2 channel centerpiece cells (loading volume of 105 µL). Data, namely 60 scans at 5.3 minute intervals, were collected at 50 krpm and 260 nm, except for the highest loading concentration where 280 nm was used. Data were analyzed in SEDFIT 11.71 in terms of a continuous c(s) distribution covering an s range of 1.0 – 7.0 S with a resolution of 100 and a confidence level (F-ratio) of 0.6851. A partial specific volume of 0.7001 cm3 g−1 was used, this being the value calculated for the 2:1 Sin:dsDNA complex. Excellent fits were obtained with r.m.s.d. values of 0.0044 – 0.0062 absorbance units. Samples of a 2:1 mixture of S9A/R54E/Q115R Sin and dsDNA were studied at loading concentrations of 0.15, 0.36 and 0.72 µM complex in 12 mm path length 2 channel centerpiece cells (loading volume of 400 µL) and 1.2 and 2.5 µM complex in 3 mm path length 2 channel centerpiece cells (loading volume of 105 µL). Data were collected and analyzed as above with excellent fits (r.m.s.d. values of 0.0044 – 0.0099 absorbance units). The c(s) distributions obtained were used to estimate the populations of the 2:1 and 4:2 Sin:dsDNA complexes; the equilibrium constant describing the dimerization of the 2:1 complex was then obtained by using the population isotherm model of SEDPHAT.53 An extinction coefficient of 977,100 M−1 cm−1 for the 2:1 complex was used (cf. ε260 dsDNA = 967,090 M−1 cm−1, ε280 Sin = 10,430 M−1 cm−1 with A260/A280 = 0.48).

Sedimentation equilibrium

Sedimentation equilibrium experiments were conducted at 20.0°C on a Beckman Optima XL-A analytical ultracentrifuge. Samples of dsDNA (loading volume of 135 µL) were studied at loading concentrations of 0.31, 0.53 and 1.03 µM. Data were acquired at various rotor speeds ranging from 14,000 to 26,000 rpm, as an average of 4 absorbance measurements at a wavelength of 260 nm and a radial spacing of 0.001 cm. Equilibrium was achieved within 36 hours. Data were analyzed globally in terms of a single ideal solute using SEDPHAT 6.21.53 Samples of a 2:1 mixture of S9A/R54E/Q115R Sin and dsDNA were studied at loading concentrations of 0.17, 0.36 and 0.74 µM complex in 12 mm path length 6 channel centerpiece cells (loading volume of 135 µL) and 0.62, 1.28 and 2.59 µM complex in 3 mm path length 2 channel centerpiece cells (loading volume of 35 µL). Data were acquired at various rotor speeds ranging from 10,000 to 22,000 rpm, as an average of 4 absorbance measurements at a wavelength of 260 nm and a radial spacing of 0.001 cm. Equilibrium was achieved within 40 hours. Data were analyzed globally with mass conservation, in terms of a reversible “monomer-dimer” self-association using SEDPHAT 6.21 with the “monomer” representing the 2:1 Sin:dsDNA complex.53

Sedimentation velocity analysis of Sin variants in the absence of DNA

Sedimentation velocity experiments shown in Figure S3 were carried out using an XL-A analytical ultracentrifuge (Beckman-Coulter) equipped with absorbance optics and an An-60 Ti rotor. Sample cells with 2-channel centerpieces and quartz windows were used. The experiments were carried out at 40000 rpm and 20°C using 50 µM Sin in 25 mM TRIS (pH 7.5) and 200 mM (NH4)2SO4. A series of 200 scans was collected from each sample at 280 nm. Scans were taken every 5 minutes with a radial step size of 0.003 cm. Multiple scans at different timepoints were fit to a continuous size distribution model c(s) using SEDFIT.24; 54 For each protein, a numerical solution of the Lamm equation was used to estimate the molecular mass and frictional ratio (f/fo). A partial specific volume of 0.73 cm3/g was used for Sin.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1: 52-mer site I – containing dsDNA is a monodisperse monomer. Sedimentation equilibrium profiles for the 52-mer dsDNA at 20.0°C plotted as a distribution of the absorbance at 260 nm vs. radius at equilibrium. Data were collected at 14 (orange), 17 (yellow), 20 (green), 23 (cyan) and 26 (brown) krpm and loading A260 of 0.37 (left panel), 0.61 (center panel) and 1.20 (right panel). The solid lines show the best-fit analysis in terms of a single ideal solute; the corresponding residuals are shown in the plots above.

Figure S2: S9A/R54E/Q115R Sin and dsDNA form self-associating 2:1 and 4:2 complexes. Sedimentation equilibrium profiles for 2:1 mixtures of S9A/R54E/Q115R Sin:dsDNA at 20.0°C plotted as a distribution of the absorbance at 260 nm vs. radius at equilibrium. Data were collected at 10 (orange), 14 (yellow), 18 (green) and 22 (brown) krpm and various loading A260: (A) 0.20 (left panel), 0.42 (center panel) and 0.86 (right panel) in 12 mm path length cells and (B) 0.18 (left panel), 0.37 (center panel) and 0.75 (right panel) in 3 mm path length cells. The solid lines show the global best-fit analysis in terms of a monomer-dimer reversible equilibrium with the monomer representing the 2:1 Sin:dsDNA; the corresponding residuals are shown in the plots above.

Figure S3: Sedimentation velocity analysis of Sin proteins in the absence of DNA. The c(S) distribution profiles for WT, I100T, and S9A/R54E/Q115R Sin proteins were determined using SEDFIT. The predicted molecular masses of WT and I100T Sin (40 and 39kDa, respectively) are consistent with the mass of a dimer, whereas the predicted mass of S9A/R54E/Q115R Sin (96 kDa) is consistent with the mass of a tetramer.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Katrine Whiteson for comments on the manuscript, Selene Koo for help with figures, and Elena Solomaha at the University of Chicago biophysical core facility for help with collection and analysis of preliminary analytical ultracentrifugation data. We are very grateful to Rick Cosstick (Liverpool) for providing 3’S-modified site I substrates which will be used in future studies. This work was funded in part by NIH grant GM086826 (P.A.R.), Wellcome Trust Project Grant 072552 (W.M.S., S.-J.R. and M.R.B), Medical Scientist National Research Service Award 5 T32 G07281 (K.W.M.), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (J.A.P.), and by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R.G.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grindley NDF, Whiteson KL, Rice PA. Mechanisms of site-specific recombination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2006;75:567–605. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith MCM, Thorpe HM. Diversity in the serine recombinases. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;44:299–307. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Highlander SK, Hulten KG, Qin X, Jiang H, Yerrapragada S, Mason EO, Jr, Shang Y, Williams TM, Fortunov RM, Liu Y, Igboeli O, Petrosino J, Tirumalai M, Uzman A, Fox GE, Cardenas AM, Muzny DM, Hemphill L, Ding Y, Dugan S, Blyth PR, Buhay CJ, Dinh HH, Hawes AC, Holder M, Kovar CL, Lee SL, Liu W, Nazareth LV, Wang Q, Zhou J, Kaplan SL, Weinstock GM. Subtle genetic changes enhance virulence of methicillin resistant and sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Microbiol. 2007;7:99. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-7-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paulsen IT, Gillespie MT, Littlejohn TG, Hanvivatvong O, Rowland SJ, Dyke KG, Skurray RA. Characterisation of sin, a potential recombinase-encoding gene from Staphylococcus aureus. Gene. 1994;141:109–114. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rowland S-J, Dyke KGH. Characterization of the staphylococcal β-lactamase transposon Tn552. EMBO J. 1989;8:2761–2773. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08418.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rowland S-J, Stark WM, Boocock MR. Sin recombinase from Staphylococcus aureus: synaptic complex architecture and transposon targeting. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;44:607–619. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rowland S-J, Boocock MR, Stark WM. DNA bending in the Sin recombination synapse: functional replacement of HU by IHF. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;59:1730–1743. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stark WM, Boocock MR. Topological selectivity in site-specific recombination. In: Sherratt DJ, editor. Mobile Genetic Elements. Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ. Press; 1995. pp. 101–129. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stark WM, Sherratt DJ, Boocock MR. Site-specific recombination by Tn3 resolvase: topological changes in the forward and reverse reactions. Cell. 1989;58:779–790. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stark WM, Boocock MR. The linkage change of a knotting reaction catalysed by Tn3 resolvase. J. Mol. Biol. 1994;239:25–36. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li W, Kamtekar S, Xiong Y, Sarkis GJ, Grindley NDF, Steitz TA. Structure of a synaptic γδ resolvase tetramer covalently linked to two cleaved DNAs. Science. 2005;309:1210–1215. doi: 10.1126/science.1112064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dhar G, Sanders ER, Johnson RC. Architecture of the Hin synaptic complex during recombination: the recombinase subunits translocate with the DNA strands. Cell. 2004;119:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rowland S-J, Boocock MR, Stark WM. Regulation of Sin recombinase by accessory proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;56:371–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mouw KW, Rowland S-J, Gajjar MM, Boocock MR, Stark WM, Rice PA. Architecture of a serine recombinase - DNA regulatory complex. Mol. Cell. 2008;30:145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rowland SJ, Boocock MR, McPherson AL, Mouw KW, Rice PA, Stark WM. Regulatory mutations in Sin recombinase support a structure-based model of the synaptosome. Mol Microbiol. 2009;74:282–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06756.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamtekar S, Ho RS, Cocco MJ, Li W, Wenwieser SVCT, Boocock MR, Grindley NDF, Steitz TA. Implications of structures of synaptic tetramers of γδ resolvase for the mechanism of recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:10642–10647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604062103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dhar G, McLean MM, Heiss JK, Johnson RC. The Hin recombinase assembles a tetrameric protein swivel that exchanges DNA strands. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:4743–4756. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nollman M, He J, Byron O, Stark WM. Solution structure of the Tn3 resolvase-crossover site synaptic complex. Mol. Cell. 2004;16:127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burgin AB, Huizenga BN, Nash HA. A novel suicide substrate for DNA topoisomerases and site-specific recombinases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:2973–2979. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.15.2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deweese JE, Burgin AB, Osheroff N. Using 3'-bridging phosphorothiolates to isolate the forward DNA cleavage reaction of human topoisomerase IIa. Biochemistry. 2008;47:4129–4140. doi: 10.1021/bi702194x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hatfull GF, Salvo JJ, Falvey EE, Rimphanitchayakit V, Grindey NDF. Site-specific recombination by the γδ resolvase. Symp. Soc. Gen. Microbiol. 1988;43:149–181. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang W, Steitz TA. Crystal structure of the site-specific recombinase γδ resolvase complexed with a 34 bp cleavage site. Cell. 1995;82:193–207. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen G, Eisenberg H. Deoxyribonucleate solutions: sedimentation in a density gradient, partial specific volumes, density and refractive index increments, and preferential interactions. Biopolymers. 1968;6:1077–1100. doi: 10.1002/bip.1968.360060805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schuck P. Size-distribution analysis of macromolecules by sedimentation velocity ultracentrifugation and Lamm equation modeling. Biophys. J. 2000;78:1606–1619. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76713-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nollman M, Byron O, Stark WM. Behavior of Tn3 resolvase in solution and its interaction with res. Biophys. J. 2005;89:1920–1931. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.058164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burgin AB. Synthesis and use of DNA containing a 5'-bridging phosphorothioate as a suicide substrate for type I DNA topoisomerases. Methods Mol. Biol. 2001;95:119–128. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-057-8:119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krogh BO, Cheng C, Burgin AB, Shuman S. Melanoplus sanguinipes entomopoxvirus DNA topoisomerase: site-specfic DNA transesterification and effects of 5'-bridging phosphorothiolates. Virology. 1999;264:441–451. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krogh BO, Shuman S. Catalytic mechanism of DNA topoisomerase IB. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:1035–1041. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burgin AB, Nash HA. Symmetry in the mechanism of bacteriophage λ integrative recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:9642–9646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burgin AB, Nash HA. Suicide substrates reveal properties of the homology-dependent steps during integrative recombination of bacteriophage λ. Curr. Biol. 1995;5:1312–1321. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00258-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stivers JT, Shuman S, Mildvan AS. Vaccinia DNA topoisomerase I: kinetic evidence for general acid-base catalysis and a conformational step. Biochemistry. 1994;33:15449–15458. doi: 10.1021/bi00255a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gonzalez-Perez B, Lucas M, Cooke LA, Vyle JS, de la Cruz F, Moncalian G. Analysis of DNA processing reactions in bacterial conjugation by using suicide oligonucleotides. EMBO J. 2007;26:3847–3857. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Voziyanov Y, Lee J, Whang I, Jayaram M. Analyses of the first chemical step in Flp site-specific recombination: Synapsis may not be a pre-requisite for strand cleavage. J Mol Biol. 1996;256:720–735. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whiteson KL, Chen Y, Chopra N, Raymond AC, Rice PA. Identification of a potential general acid/base in the reversible phosphoryl transfer reactions catalyzed by tyrosine recombinases: Flp H305. Chem Biol. 2007;14:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghosh K, Lau C-K, Gupta K, van Duyne GD. Preferential synapsis of loxP sites drives ordered strand exchange in Cre-loxP site-specific recombination. Nature Chem. Biol. 2005;1:275–282. doi: 10.1038/nchembio733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hughes RE, Hatfull GF, Rice P, Steitz TA, Grindley ND. Cooperativity mutants of the gamma delta resolvase identify an essential interdimer interaction. Cell. 1990;63:1331–1338. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90428-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sarkis GJ, Murley LL, Leschziner AE, Boocock MR, Stark WM, Grindley ND. A model for the γδ resolvase synaptic complex. Mol. Cell. 2001;8:623–631. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00334-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burke ME, Arnold PH, He J, Wenwieser S, Rowland S-J, Boocock MR, Stark WM. Activating mutations of Tn3 resolvase marking interfaces important in recombination catalysis and its regulation. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;51:937–948. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olorunniji FJ, He J, Wenwieser SV, Boocock MR, Stark WM. Synapsis and catalysis by activated Tn3 resolvase mutants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:7181–7191. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanders ER, Johnson RC. Stepwise dissection of the Hin-catalyzed recombination reaction from synapsis to resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;340:753–766. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boocock MR, Zhu X, Grindley ND. Catalytic residues of γδ resolvase act in cis. EMBO J. 1995;14:5129–5140. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McIlwraith MJ, Boocock MR, Stark WM. Tn3 resolvase catalyzes multiple recombination events without intermediate rejoining of DNA ends. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;266:108–121. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arnold PH, Blake DG, Grindley ND, Boocock MR, Stark WM. Mutants of Tn3 resolvase which do not require accessory binding sites for recombination activity. EMBO J. 1999;18:1407–1414. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dhar G, Heiss JK, Johnson RC. Mechanical constraints on Hin subunit rotation imposed by the Fis/enhancer system and DNA supercoiling during site-specific recombination. Mol Cell. 2009;34:746–759. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gupta M, Till R, Smith MC. Sequences in attB that affect the ability of phiC31 integrase to synapse and to activate DNA cleavage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3407–3419. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McEwan AR, Rowley PA, Smith MC. DNA binding and synapsis by the large C-terminal domain of phiC31 integrase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:4764–4773. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cosstick R, Vyle JS. Synthesis and properties of dithymidine phosphate analogues containing 3'-thiothymidine. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:829–835. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.4.829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vyle JS, Connolly BA, Kemp D, Cosstick R. Sequence- and strand-specific cleavage in oligodeoxyribonucleotides and DNA containing 3'-thiothymidine. Biochemistry. 1992;31:3012–3018. doi: 10.1021/bi00126a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun S, Yoshida A, Piccirilli JA. Synthesis of 3'-thioribonucleosides and their incorporation into oligoribonucleotides via phosphoramidite chemistry. RNA. 1997;3:1352–1363. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sabbagh G, Fettes KJ, Gosain R, O'Neil IA, Cosstick R. Synthesis of phosphorothioamidites derived from 3'-thio-3'-deoxythymidine and 3'-thio-2',3'-dideoxycytidine and the automated synthesis of oligodeoxynucleotides containing a 3'-S-phosphorothiolate linkage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:495–501. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schuck P. On the analysis of protein self-association by sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation. Anal. Biochem. 2003;320:104–124. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(03)00289-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cole JL, Lary JW, T PM, Laue TM. Analytical ultracentrifugation: sedimentation velocity and sedimentation equilibrium. Methods Cell Biol. 2008;84:143–179. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(07)84006-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lebowitz J, Lewis MS, Schuck P. Modern analytical ultracentrifugation in protein science: a tutorial review. Protein Sci. 2002;11:2067–2079. doi: 10.1110/ps.0207702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brown PH, Schuck P. Macromolecular size-and-shape distributions by sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation. Biophys. J. 2006;90:4651–4661. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.081372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rice PA, Yang S, Mizuuchi K, Nash HA. Crystal structure of an IHF-DNA complex: a protein-induced DNA U-turn. Cell. 1996;87:1295–1306. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81824-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: 52-mer site I – containing dsDNA is a monodisperse monomer. Sedimentation equilibrium profiles for the 52-mer dsDNA at 20.0°C plotted as a distribution of the absorbance at 260 nm vs. radius at equilibrium. Data were collected at 14 (orange), 17 (yellow), 20 (green), 23 (cyan) and 26 (brown) krpm and loading A260 of 0.37 (left panel), 0.61 (center panel) and 1.20 (right panel). The solid lines show the best-fit analysis in terms of a single ideal solute; the corresponding residuals are shown in the plots above.

Figure S2: S9A/R54E/Q115R Sin and dsDNA form self-associating 2:1 and 4:2 complexes. Sedimentation equilibrium profiles for 2:1 mixtures of S9A/R54E/Q115R Sin:dsDNA at 20.0°C plotted as a distribution of the absorbance at 260 nm vs. radius at equilibrium. Data were collected at 10 (orange), 14 (yellow), 18 (green) and 22 (brown) krpm and various loading A260: (A) 0.20 (left panel), 0.42 (center panel) and 0.86 (right panel) in 12 mm path length cells and (B) 0.18 (left panel), 0.37 (center panel) and 0.75 (right panel) in 3 mm path length cells. The solid lines show the global best-fit analysis in terms of a monomer-dimer reversible equilibrium with the monomer representing the 2:1 Sin:dsDNA; the corresponding residuals are shown in the plots above.