Abstract

A colorimetric sensor array has been developed for the rapid and sensitive detection of 20 toxic industrial chemicals (TICs) at their PELs (permissible exposure limits). The color changes in an array of chemically responsive nanoporous pigments provide facile identification of the TICs with an error rate below 0.7%.

Chemists have no equivalent of the physicists’ radiation badge: there is no readily available general purpose method to easily measure the low levels of personal exposure that workers may receive to the diverse range of volatile TICs used in laboratories, manufacturing facilities, or general storage areas.1,2 There are numerous conventional methods2 for the detection of gas phase hazardous chemicals, including GC/MS,3 IMS,4 electronic nose technologies,5 and of course colorimetric detectors tailored to specific single analytes.2 Most such detection technologies, however, suffer from severe limitations: GC/MS is expensive and non-portable; IMS has limited chemical specificity; and electronic nose technologies have restricted selectivity, sensitivity, and resistance to environmental interference (e.g., humidity).

In recent years, we have developed a rather different optoelectronic technique using colorimetric sensor arrays made from chemically responsive dyes. This array approach6,7 is based on strong dye–analyte interactions and differs from other electronic nose technologies that generally rely on the weaker and less specific intermolecular interactions (i.e., van der Waals and physical adsorption). The chemically responsive dyes in our colorimetric array include (1) metal ion containing dyes (e.g., metalloporphyrins) that respond to Lewis basicity, (2) pH indicators that respond to Brønsted acidity/basicity, (3) vapochromic/solvatochromic dyes that respond to local polarity, and (4) metal salt redox indicators (see ESI,† Fig. S1).

We have very recently improved our array methodology by the use of chemically responsive nanoporous pigments created from the immobilization of dyes in organically modified siloxanes (ormosils).8,9 Porous sol–gel glasses provide excellent matrices for colorants due to high surface area, relative inertness in both gases and liquids, good stability over a wide range of pH, and optical transparency. In addition, the physical and chemical properties of the matrix (e.g., hydrophobicity, porosity) can be easily modified by changing the sol–gel formulations. The use of nanoporous pigments significantly improves the stability and shelf-life of the colorimetric sensor arrays and permits direct printing onto non-permeable polymer surfaces.9,10 Additionally, we observe that the porous matrix serves as a preconcentrator thereby improving the overall sensitivity.10

We report here the application of colorimetric sensor arrays to the identification and semiquantitative analysis of toxic industrial chemicals at their PELs and demonstrate limits of recognition below 5% of the PELs. We chose 20 representative examples of high priority TICs, selected from the International Task Force ITF-25 and ITF-40 reports.11 Using an array of chemically responsive nanoporous pigments, we have observed limits of detection down to ppb levels.

For gas analysis, digital images of an array (1 cm2) were acquired before and after exposure to a diluted gas mixture (see ESI,† Fig. S2) using an ordinary flatbed scanner. For each spot in the array, the red, green, and blue values were measured before and after TIC exposure and color difference maps were generated. These difference maps provide a molecular fingerprint that effectively identifies the analyte to which the array has been exposed. The pattern of the array response permits facile detection and identification of the 20 representative TICs and a control, as shown in Fig. 1. Even at low concentrations, the TICs can be identified simply from the array color change pattern in a matter of seconds with >90% of total response in less than five minutes (see ESI,† Fig. S3).

Figure 1.

Color difference maps of representative TICs at their PEL concentration after 5 min of exposure at 50% relative humidity and 298 K. The list of pigments and a full digital database are provided in the ESI,† Tables S1 and S2. For display purposes, the color range of these difference maps are expanded from 4 to 8 bits per color (RGB range of 4–19 expanded to 0–255), except for several weaker responding TICs that are marked with asterisks (RGB range of 2–3 expanded to 0–255).

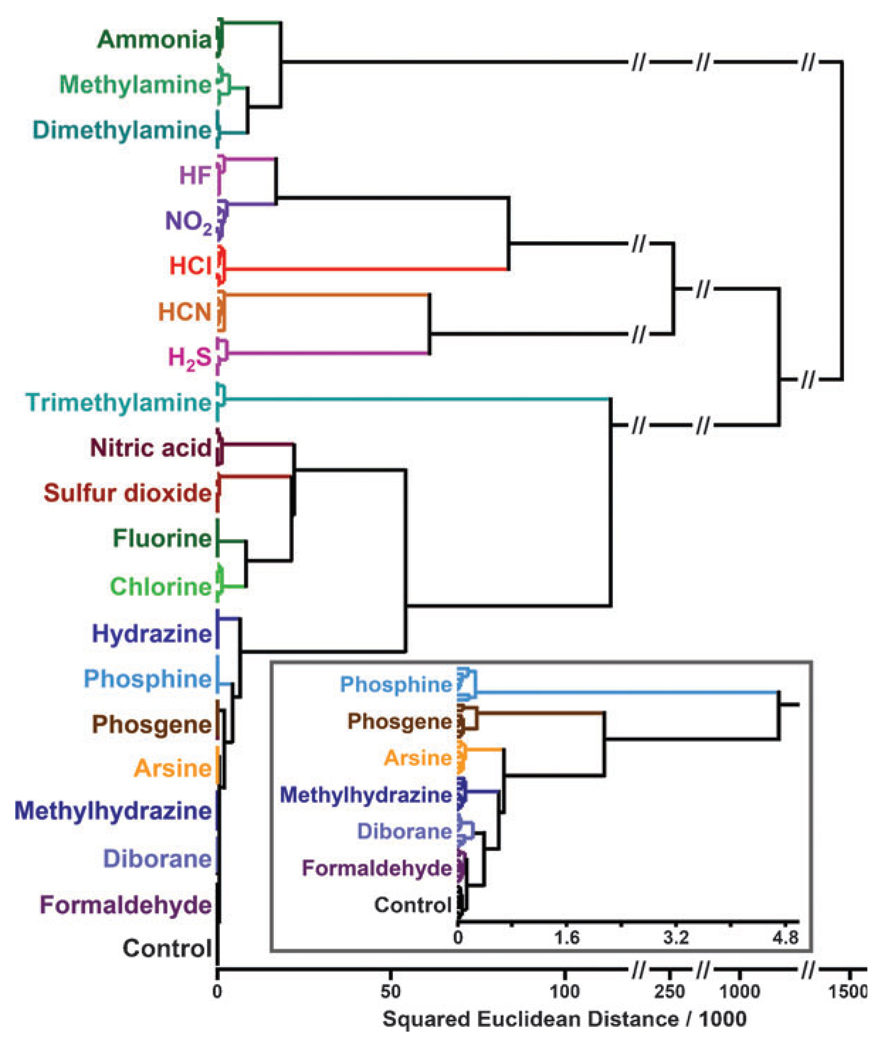

For quantitative analysis of the color changes of the array, we can define a 108-dimensional vector (i.e., 36 changes in red, green and blue values) and the vector for each trial can be compared and classified by standard chemometric techniques. We prefer the use of a quite standard chemometric approach, hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA), which is based on the grouping of the analyte vectors according to their spatial distances in their full vector space.12 HCA has the advantages of being model-free (unlike linear discriminant analysis) and of using the full dimensionality of the data. HCA has also found use for colorimetric array sensing of anions.13 As shown in Fig. 2, HCA generates dendrograms based on clustering of the array response data in the 108-dimensional ΔRGB color space. Remarkably, in septuplicate trials, all 20 TICs and a control were accurately classified with no errors out of 147 cases. Even weakly responding gases (see inset of Fig. 2) gave discrete clusters without error.

Figure 2.

Hierarchical cluster analysis for 20 TICs at permissible exposure levels and a control. Inset shows an enlarged view of the less responsive TICs. All experiments were run in septuplicate; no confusions or errors in classification were observed in 147 trials, as shown.

The ability of the colorimetric sensor array to discriminate among many analytes is due, in part, to the high dimensionality of the data. Principal component analysis (PCA) uses the variance in the array response to evaluate the relative contributions of independent dimensions and generates optimized linear combinations of the original 108 dimensions so as to maximize the amount of variance in as few dimensions as possible. Based on the 147 trials of 20 TICs and a control, the PCA of our colorimetric sensor array requires 17 dimensions for 90% of total variance and 26 dimensions for 95% (see ESI,† Fig. S4). This extremely high dispersion reflects the wide range of chemical-property space being probed by our choice of chemically responsive pigments. Consequently, chemically diverse analytes are easily recognizable, and even closely related mixtures can be distinguished. In contrast, data from most prior electronic nose technologies are dominated by only two or three independent dimensions (one of which, analyte hydrophobicity, generally accounts for >90% of total variance); this is the inherent result of relying on van der Waals and other weak interactions for molecular recognition.

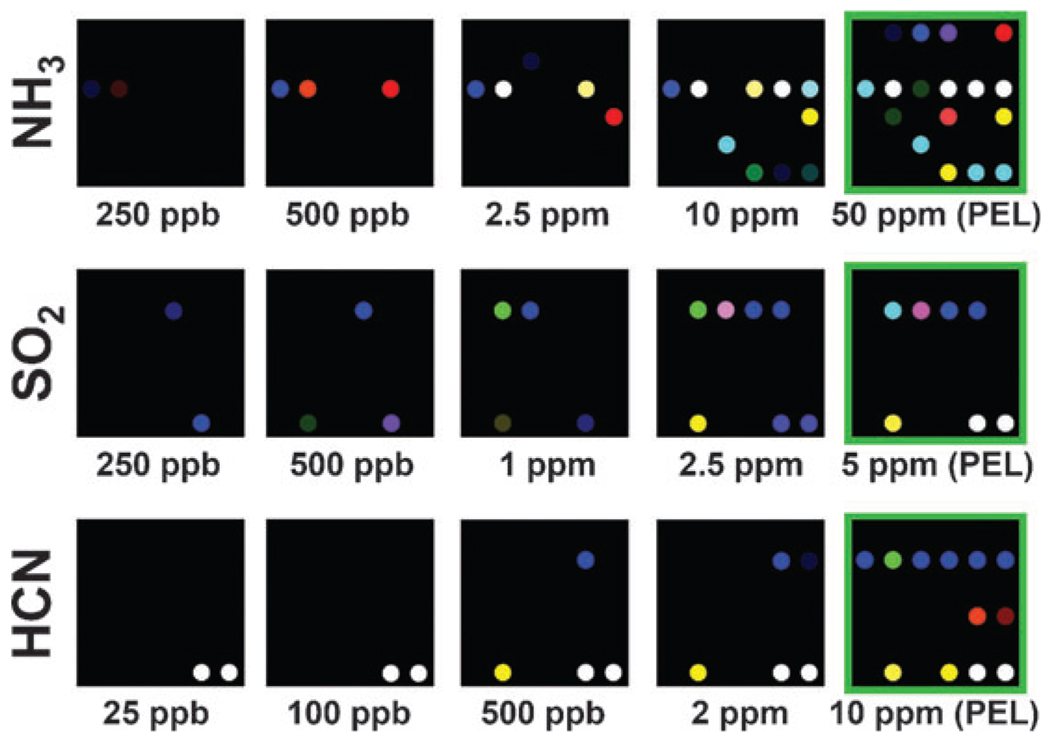

The color changes of the array are dependent upon the concentration of each gas, which provides an easy method for semi-quantitative analysis of TIC concentration and for determination of limits of detection. Variation in the TIC concentration was provided by serial dilution using mass flow controllers (see ESI,† Fig. S5). Color difference maps for three representative analytes as a function of concentrations below the PEL are shown in Fig. 3. For any given observation, semi-quantitative interpolation of the TIC concentration can be easily accomplished using the total Euclidean distance (i.e., square root of the sum of the squares of the color differences) of the observation compared to a set of known concentrations in the library.

Figure 3.

The effect of concentration on array response to NH3, SO2, and HCN. The observed limits of detection (LOD) are well below 5% of the PEL. For display purposes, the color range of these difference maps are expanded from 2 to 8 bits per color (RGB range of 4–7 expanded to 0–255). Color difference maps shown are after 5 min exposure at 298 K and 50% relative humidity.

We can estimate the limit of detection (LOD) for each TIC by extrapolating from the observed array response at their respective PELs. We have defined the LOD for our array response as the TIC concentration needed to give three times the S/N vs. background for the sum of the three largest responses among the 108 color changes. Table 1 lists our estimated LODs based on their five minute PEL response.

Table 1.

The extrapolated LODs for 20 toxic industrial chemicals

| TICs | PEL (ppm) | Extrapolated LOD (ppm) |

|---|---|---|

| Ammonia | 50 | 0.08 |

| Arsine | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| Chlorine | 1 | 0.01 |

| Diborane | 0.1 | 0.01 |

| Dimethylamine | 10 | 0.01 |

| Fluorine | 0.1 | 0.01 |

| Formaldehyde | 0.75 | 0.12 |

| Hydrogen chloride | 5 | 0.02 |

| Hydrogen cyanide | 10 | 0.02 |

| Hydrogen fluoride | 3 | 0.02 |

| Hydrogen sulfide | 20 | 0.08 |

| Hydrazine | 1 | 0.01 |

| Methylamine | 10 | 0.01 |

| Methyl hydrazine | 0.2 | 0.01 |

| Nitric acid | 2 | 0.02 |

| Nitrogen dioxide | 5 | 0.03 |

| Phosgene | 0.1 | 0.01 |

| Phosphine | 0.3 | 0.01 |

| Sulfur dioxide | 5 | 0.06 |

| Trimethylamine | 10 | 0.03 |

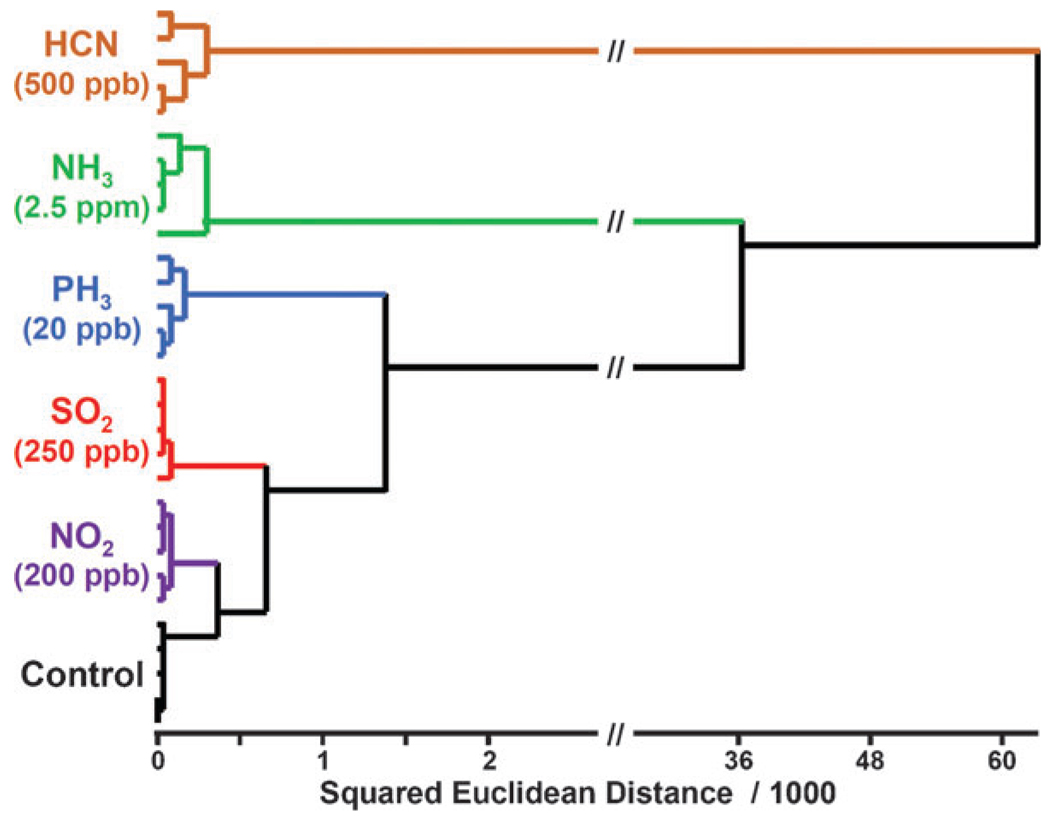

A LOD, of course, only indicates the concentration at which the sensor first detects some analyte but cannot tell what that analyte is. The limit of recognition (LOR) is a less well-defined concept that is dependent upon the group of analytes among which one wishes to discriminate. In order to generate a rough estimate of LOR of our array, we examined a subset of five TICs at concentrations far below their PELs. As shown in Fig. 4, classification of these five TICs at 5% of the PEL was without misclassification in 30 quintuplicate trials.

Figure 4.

Low concentration tests of five TICs at ~5% of their PELs after 10 min exposure. All experiments were run in quintuplicate; no confusions or errors in classification were observed in 30 trials, as shown.

In real world situations, changes in humidity are highly problematic for prior electronic nose technologies. The sol–gel formulations used in our sensing arrays are essentially impervious to changes in relative humidity. Using 50% relative humidity (RH) as a control, arrays were exposed to various humidity concentrations for 10 minutes (see ESI,† Fig. S6). No significant response to humidity was observed from 10% to 90% RH. Thus, changes in humidity do not generally affect the response of our sensor arrays to analytes, even at low concentrations.

In summary, we have created a simple, disposable colorimetric sensor array of nanoporous pigments that is capable of rapid and sensitive detection of a wide range of toxic gases. Classification analysis reveals that the colorimetric sensor array has an extremely high dimensionality with the consequent ability to discriminate among a large number of TICs over a wide range of concentrations. The sensor array is able to discriminate without error among 20 toxic industrial chemicals at their permissible exposure levels, with estimated limits of detection in the few ppb range. While we are not yet at the point of a truly wearable personal monitor for multiple toxic gases, we do have a handheld array reader at the protype stage of development (see ESI,† Fig. S7 and S8), and further miniaturization is under development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported through the NIH Genes, Environment and Health Initiative through award U01ES016011.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Difference maps, experimental set-up, database. See DOI: 10.1039/b926848k

Notes and references

- 1.(a) Byrnes ME, King DA, Tierno PM., Jr . Nuclear, Chemical, and Biological Terrorism-Emergency Response and Public Protection. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lauwerys RR, Hoet P. Industrial Chemical Exposure: Guidelines for Biological Monitoring. 3rd edn. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Chou J. Hazardous Gas Monitors: A Practical Guide to Selection, Operation and Applications. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2000. [Google Scholar]; (b) McDermott HJ. Air Monitoring for Toxic Exposure. New Jersey: Wiley & Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hübschmann H-J. Handbook of GC/MS: Fundamentals and Applications. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eiceman GA, Karpas Z. Ion Mobility Spectrometry. FL: CRC Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Gardner JW, Bartlett PN. Electronic Noses: Principles and Applications. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lewis NS. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004;37:663. doi: 10.1021/ar030120m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Röck F, Barsan N, Weimar U. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:705. doi: 10.1021/cr068121q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Hierlemann A, Gutierrez-Osuna R. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:563. doi: 10.1021/cr068116m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Anslyn EV. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:687. doi: 10.1021/jo0617971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Walt DR. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:5281. doi: 10.1021/ac900505p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Wolfbeis OS. J. Mater. Chem. 2005;15:2657. [Google Scholar]; (h) Hsieh MD, Zellers ET. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:1885. doi: 10.1021/ac035294w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Janata J, Josowicz M. Nat. Mater. 2003;2:19. doi: 10.1038/nmat768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Grate JW. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:2627. doi: 10.1021/cr980094j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Suslick KS, Bailey DP, Ingison CK, Janzen M, Kosal MA, McNamara WB, III, Rakow NA, Sen A, Weaver JJ, Wilson JB, Zhang C, Nakagaki S. Quim. Nova. 2007;30:677. [Google Scholar]; (b) Suslick KS. MRS Bull. 2004;29:720. doi: 10.1557/mrs2004.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Rakow NA, Suslick KS. Nature. 2000;406:710. doi: 10.1038/35021028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rakow NA, Sen A, Janzen MC, Ponder JB, Suslick KS. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:4528. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Janzen MC, Ponder JB, Bailey DP, Ingison CK, Suslick KS. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:3591. doi: 10.1021/ac052111s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Baldini F, Chester AN, Homola J, Martellucci S. Optical Chemical Sensors. Erice, Italy: Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]; (b) Rottman C, Grader G, De Hazan Y, Melchior S, Avnir D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:8533. [Google Scholar]; (c) Jeronimo PCA, Araujo AN, Montenegro M.Talanta 2007721319071577 [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Lim SH, Musto CJ, Park E, Zhong W, Suslick KS. Org. Lett. 2008;10:4405. doi: 10.1021/ol801459k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Musto CJ, Lim SH, Suslick KS. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:6526. doi: 10.1021/ac901019g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim SH, Feng L, Kemling JW, Musto CJ, Suslick KS. Nat. Chem. 2009;1:562. doi: 10.1038/nchem.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Steumpfle AK, Howells DJ, Armour SJ, Boulet CA. Final Report of International Task Force-25: Hazard From Toxic Industrial Chemicals. Washington, DC: US GPO; 1996. [Google Scholar]; (b) Armour SJ. International Task Force 40: Toxic Industrial Chemicals (TICs)-Operational and Medical Concerns. Washington, DC: US GPO; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Scott SM, James D, Ali Z. Microchim. Acta. 2007;156:183. [Google Scholar]; (b) Johnson RA, Wichern DW. Applied Multivariate Statistical Analysis. 6th edn. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2007. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hair JF, Black B, Babin B, Anderson RE, Tatham RL. Multivariate Data Analysis. 6th edn. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palacios MA, Nishiyabu R, Marquez M, Anzenbacher P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007:129–7538. doi: 10.1021/ja0704784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.