Abstract

Helices are the most extensively studied secondary structures formed by β-peptide foldamers. Among the five known β-peptide helices, the 12-helix is particularly interesting because the internal hydrogen bond orientation and macrodipole are analogous to those of α-peptide helices (α-helix and 310-helix). The β-peptide 12-helix is defined by i, i+3 C=O…H-N backbone hydrogen bonds and promoted by β-residues with a five-membered ring constraint. The 12-helical scaffold has been used to generate β-peptides with specific biological functions, for which diverse side chains must be properly placed along the backbone and, upon folding, properly arranged in space. Only two crystal structures of 12-helical β-peptides have previously been reported, both for homooligomers of trans-2-aminocyclopentanecarboxylic acid (ACPC). Here we report five additional crystal structures of 12-helical β-peptides, all containing residues that bear side chains. Four of the crystallized β-peptides include trans-4,4-dimethyl-2-aminocyclopentanecarboxylic acid (dm-ACPC) residues, and the fifth contains a β3-hPhe residue. These five β-peptides adopt fully folded 12-helical conformations in the solid state. The new crystal structures, along with previously reported data, allow a detailed characterization of the 12-helical conformation; average backbone torsion angles of β-residues and helical parameters are derived. These structural parameters are found to be similar to those for i, i+3 C=O…H-N hydrogen-bonded helices formed by other peptide backbones generated from α- and/or βamino acids. The similarity between the conformational behavior of dm-ACPC and ACPC is consistent with previous NMR-based conclusions that 4,4-disubstituted ACPC derivatives are compatible with 12-helical folding. In addition, our data show how a β3-residue is accommodated in the 12-helix, thus enhancing understanding of the diverse conformational behavior of this flexible class of β-amino acids.

Introduction

β-Peptides are oligomers of β-amino acids and constitute perhaps the most extensively studied class of unnatural foldamers.1,2 Many examples of β-peptides that display folded conformations analogous to secondary structures of α-peptides and proteins have been identified, including examples that form helices, turns or extended conformations. β-Peptide helices have drawn considerable attention because they may be used to mimic helical sub-structures within proteins.1 Five β-peptide helices (14-, 12-, 10/12-, 10- and 8-helix) have been reported to date.1,2 The nomenclature of these helices is based on the number of atoms in the characteristic hydrogen bonds. For example, a β-peptide 12-helix is defined by i,i+3 C=O…H-N hydrogen bonds that contain 12 atoms. This particular helix is interesting from the perspective of mimicking α-helices among conventional peptides and proteins. The internal hydrogen bond orientation and macrodipole of the β-peptide 12-helix are analogous to those for the helices most commonly observed in proteins: 310-helix (i,i+3 C=O…H-N hydrogen bonds) and α-helix (i,i+4 C=O…H-N hydrogen bonds).3 In contrast, the hydrogen bond orientations of other β-peptide helices (e.g., i,i-2 C=O…H-N hydrogen bonds for the 14-helix and alternating i,i-1 C=O…H-N and i,i+3 C=O…H-N hydrogen bonds for the 10/12-helix) are not observed among α-peptide helices.2a

Experimental and computational studies suggest that the 12-helix is not intrinsically favorable for acyclic β-residues, such as the commonly used β3-homoamino acids (side chain adjacent to nitrogen), but that this secondary structure is promoted by cyclic β-residues with a five-membered ring constraint.4 We have shown that β-peptide oligomers that contain residues derived from trans-2-aminocyclopentanecarboxylic acid (ACPC) and/or trans-4-aminopyrrolidine-3-carboxylic acid (APC) adopt 12-helical conformations.5,6a In complementary work, Martinek, Fülöp et al. have recently shown that 12-helical folding is promoted by β-amino acid residues with a bicyclo[3.3.1]heptane skeleton.6b Even more recently, Aitken et al. have shown that trans-2-aminocyclobutanecarboxylic acid residues favor 12-helical folding.6c The 12-helical scaffold has served as a basis for developing β-peptides that display antimicrobial activity,7 inhibit protein-protein interactions,8 and project carbohydrates in specific three-dimensional patterns.9 For these biological applications, functional groups must be introduced at precise locations along the 12-helical backbone, which can be achieved by incorporation of acyclic βamino acid residues5g,i or cyclic β-amino acid residues that bear side chains.5e,f,h,j Data obtained in solution suggest that a few β2- or β3-residues can be incorporated into a 12-helix, if most other residues have the five-membered ring constraint.5g,i Use of β-residues with functionalized five-membered rings, however, provides functional diversity in 12-helical scaffolds without loss of conformational stability. Several approaches to five-membered ring functionalization have been reported: sulfonylation of the pyrrolidine nitrogen atom of APC,5e,f 3-substitution,5h 4,4-disubstitution5j or 3,4-disubstitution of ACPC,10a N-functionalization of a pyrrolidinone-based β-amino acid10b and generation of β-amino acid building blocks from AZT.10c,11

Only two crystal structures of 12-helical β-peptides have been reported to date, and both have been obtained with ACPC homooligomers.5c Here we provide five additional crystal structures that display 12-helical conformations. Four of the new structures contain trans-4,4-dimethyl-2-aminocyclopentanecarboxylic acid (dm-ACPC) residues, and the fifth structure contains a β3-homophenylalanine (β3-hPhe) residue embedded in an ACPC-rich sequence. This structural information enables us to identify characteristic structural parameters for the 12-helical secondary structure, and to make comparisons with other well-characterized helices.

Results and discussion

Design and Synthesis

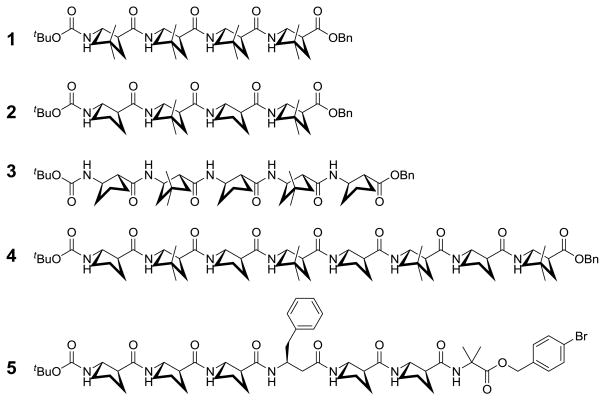

Chart 1 shows the five β-peptides for which crystal structures are reported. These molecules include a homooligomer of dm-ACPC (1) and three oligomers that contain both ACPC and dm-ACPC residues (2–4). Heptamer 5 contains a β3-hPhe residue along with five ACPC residues; the crystal structure of 5 represents the first high-resolution data for a 12-helical β-peptide containing an acyclic residue. Oligomer 5 contains an α-residue, α-aminobutyric acid (Aib), at the C-terminus, which was included to enhance solubility and crystallization.12 This α-residue does not participate in the helical hydrogen bonding pattern because there is no hydrogen bond donor at the C-terminus.

Chart 1.

β-peptides for which crystal structures are reported.

β-Peptides 1–5 were synthesized via conventional solution-phase methods involving carbodiimide-mediated coupling.12b–d ACPC13 and dm-ACPC5j building blocks were prepared by reported procedures. Each of the three shortest β-peptides (1–3) was crystallized by solvent diffusion of n-pentane into a diethyl ether/chloroform solution of the oligomer. Crystals of octamer 4 were grown by solvent diffusion of n-heptane into a 1,2-dichloroethane solution of the oligomer. Heptamer 5 was crystallized in two ways, by slow evaporation of either a methanol-water mixture or an isopropanol solution.

Crystal structures of β-peptides containing dm-ACPC residues

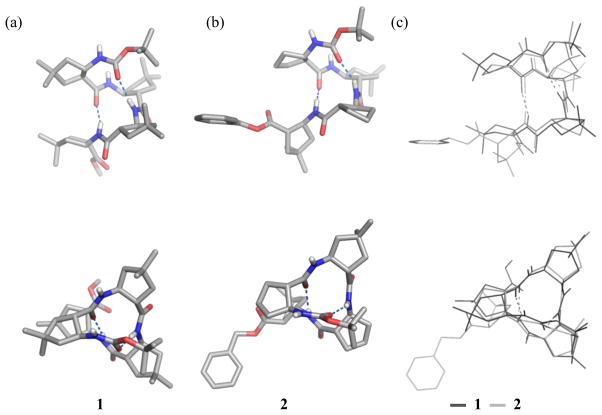

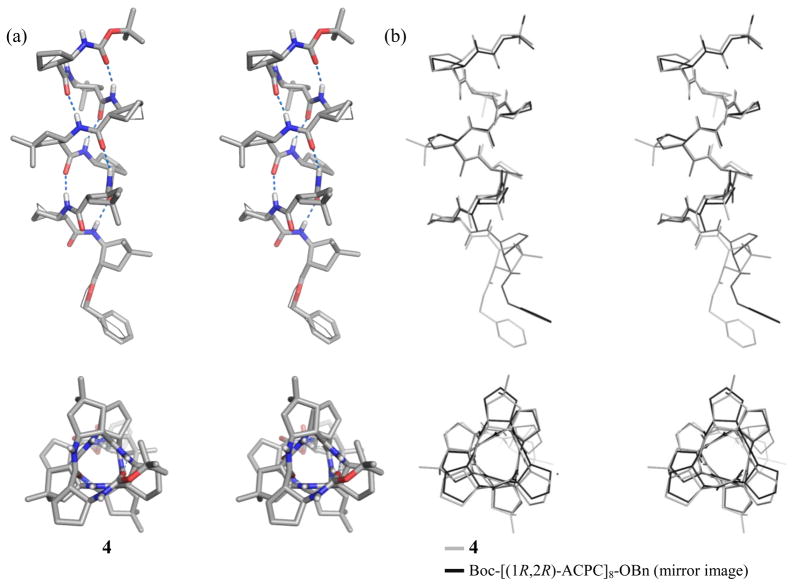

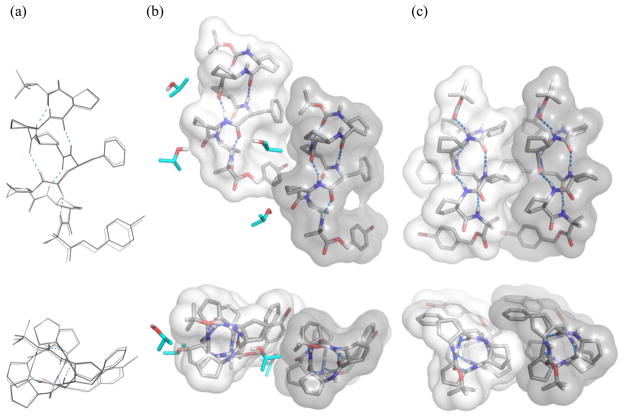

All of the four dm-ACPC-containing β-peptides display fully-folded 12-helical conformations with the maximum number of i, i+3 C=O…H-N hydrogen bonds in the crystalline state (Figures 1–3). Pentamer 3 displays a left-handed 12-helical conformation in the solid state because 3 contains (1R,2R)-forms of ACPC and dm-ACPC residues (Figure 2). The other β-peptides discussed here contain (1S,2S)-forms of ACPC and dm-ACPC residues and therefore display right-handed helical conformations. In the crystal structure of octamer 4 (Figure 3) the C-terminal benzyl group and some cyclopentane ring puckers are disordered over two positions (9:1 to 6:4 ratio). Interestingly, ring pucker disorder is limited to ACPC residues; no disordered carbons are found among the four dm-ACPC residues. The sequence of 4 is analogous to that of a previously reported homooligomer, Boc-[(1R,2R)-ACPC]8-OBn.5c The principal differences between 4 and Boc-[(1R,2R)-ACPC]8-OBn are the gem-dimethyl substituents of the dm-ACPC residues in 4 and the opposite handedness of the two helices. In Figure 3b the right-handed 12-helical conformation observed for 4 in the solid state is superimposed on the mirror image of the left-handed 12-helical conformation observed for Boc-[(1R,2R)-ACPC]8-OBn. The backbones of these two 12-helices are virtually identical except for the C-terminal residue in each β-peptide, the ester of which cannot serve as a hydrogen bond donor. These results suggest that the gem-dimethyl substituents of the dm-ACPC residues do not cause any distortion of the 12-helical conformation, a conclusion that is consistent with the results of two-dimensional NMR studies of analogous β-peptides in solution.5j

Figure 1.

Crystal structures of tetramers: (a) 1, (b) 2, (c) overlay of the two structures. The upper views are perpendicular to the helical axis, and the lower views are along the helical axis. Dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonds. A co-crystallized chloroform molecule for 2 and most hydrogen atoms for both 1 and 2 are omitted for clarity.

Figure 3.

(a) Crystal structure of octamer 4. Alternative positions of disordered atoms are indicated with thin lines (stereoview). (b) Overlay of the structure of 4 (gray lines) and the mirror image of the structure of Boc-[(1R,2R)-ACPC]8-OBn (black lines; ref. 5c) (stereoview). The upper view is perpendicular to the helical axis, and the lower view is along the helical axis. Dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonds. Most hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.

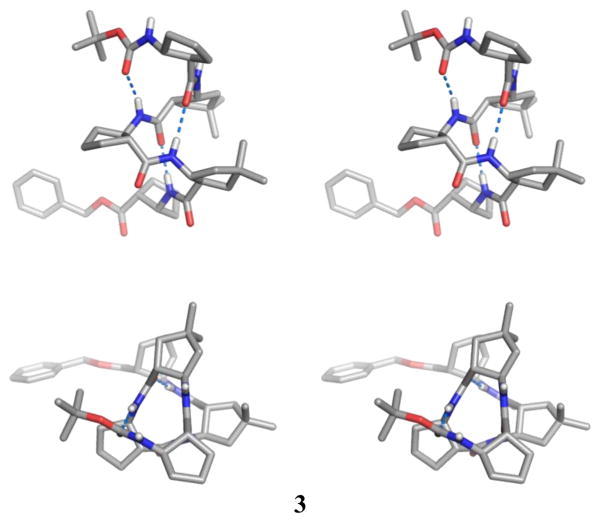

Figure 2.

Crystal structure of pentamer 3 (stereoview). The upper view is perpendicular to the helical axis, and the lower view is along the helical axis. Dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonds. A co-crystallized ether molecule, a disordered carbon atom in ACPC(1), and most hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.

Crystal structure of a β-peptide containing a β3-hPhe residue

Figure 4 shows the two symmetry-independent conformations in the crystal of heptamer 5 grown from isopropanol solution. These two independent conformations are very similar to one another (Figure 4a); they are fully 12-helical, without any significant distortion around the β3-hPhe residue. The C-terminal Aib residue curls away from the helical axis in each molecule and does not affect the 12-helical conformation. There are two types of lateral interactions between adjacent molecules: close packing between two symmetry-independent conformations (Figure 4b) and close packing between two identical molecules (Figure 4c). In both cases the interacting molecules are parallel to one another. These crystal packing interactions may provide guidance for future efforts to design 12-helical segments that participate in discrete tertiary or quaternary structures.5c There is space near the α-carbon of the β3-hPhe residue at the interface shown in Figure 4b, because no substituent projects outward from this carbon (in contrast to ACPC and dm-ACPC residues). This space is occupied by an isopropanol molecule, which minimizes lateral contact between these two β-peptide molecules. In contrast, the interface highlighted in Figure 4c involves extensive intermolecular contact between cyclopentane rings of ACPC residues. This interaction is very similar to a lateral packing interaction previously observed in the crystal of an ACPC hexamer.5c

Figure 4.

The crystal structure of heptamer 5, based on a crystal grown from isopropanol: (a) overlay of two symmetry-independent molecules in the crystal, viewed perpendicular to the helical axis (top) and along the helical axis (bottom); (b) close packing between the two symmetry-independent molecules, viewed along the crystallographic a axis (top) and b axis (bottom), (c) close packing between two identical molecules, viewed along the crystallographic c axis (top) and b axis (bottom). Solvent molecules (isopropanol) are highlighted in cyan. Dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonds. Disordered atoms and most hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. Molecular surfaces for the two helical conformations are rendered as shaded areas.

A second crystal form of heptamer 5 was obtained from methanol-water solution (see Supporting Information). These crystals did not provide diffraction data of high quality; nevertheless, it was possible to determine that this crystal form contained two symmetry-independent molecules, both of which displayed 12-helical conformations similar to those seen in the crystal form from isopropanol, though the crystal packing is different from the packing seen in Figure 4b and 4c. Overall, these crystallization results suggest that adoption of the 12-helical conformation by 5 is not determined by crystal packing forces but is instead intrinsically favorable for the β-peptide portion of this oligomer, despite the presence of a flexible β3-residue.

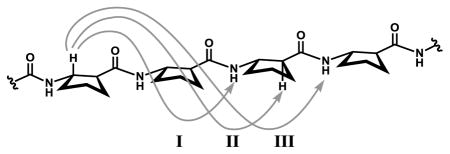

Relationship between inter-proton distances and NOE patterns

Medium-range nuclear Overhauser enhancements (NOEs) between protons on residues that are not adjacent in a peptide sequence can develop if the corresponding inter-proton distance is within 5 Å. Table 1 lists three types of medium-range NOE between backbone protons that have been associated with the β-peptide 12-helix in solution5a,j and corresponding average inter-proton distances derived from the seven available 12-helical β-peptide crystal structures (the five structures in this paper and the two previously reported ACPC homooligomer structures5c). The three average distances for each of these types of proton pairing is < 4 Å. This correlation confirms that the three NOE patterns in Table 1 are excellent indicators of 12-helical folding in solution. Inspection of the crystal structures does not reveal any other type of medium-range NOE that would be expected between backbone proton pairs from non-adjacent β-amino acid residues within a 12-helical conformation.

Table 1.

Average inter-proton distances (Ǻ) corresponding to medium-range NOE patterns observed for 12-helical β-peptides.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| NOE type | distancea | |

| I | CβH(i)—NH(i+2) | 3.5(4) [25] |

| II | CβH(i)—CαH (i+2) | 2.9(4) [21] |

| III | CβH(i)—NH(i+3) | 3.6(5) [21] |

The number in brackets indicates number of measured and averaged distances.

We have previously reported that an unexpected NOE pattern, CβH(i)—CαH (i+3), was observed for a dm-ACPC-containing β-peptide hexamer, in addition to the three NOE types in Table 1.5j This unexpected NOE pattern is not consistent with a 12-helical conformation because the corresponding inter-proton distances are > 5 Å in the available crystal structures. Interestingly, comparable NOE patterns have been observed for oligomers containing both α- and β-amino acid residues ("α/βpeptides") in either a 2:1 and a 1:2 ratio, in which all β-residues are ACPC.12d Numerous crystal structures for these types of α/β-peptides have revealed i, i+3 C=O…H-N hydrogen-bonded helical conformations, which are not consistent with the CβH(i)—CαH (i+3) NOE pattern. We have proposed that the CβH(i)—CαH (i+3) NOEs observed for the 2:1 and 1:2 α/β-peptides can be explained by alternative helical conformations involving i, i+4 C=O…H-N hydrogen bonds. Indeed, this alternative helix has been documented crystallographically for a 33-residue 2:1 α/β-peptide.14 By analogy, the CβH(i) …CαH (i+3) NOE pattern observed for the dm-ACPC-containing β-peptide hexamer could arise from an i, i+4 C=O…H-N hydrogen-bonded helical conformation, which would be designated a "16- helix".5j Although this alternative helical conformation is not observed in the crystal structures of dm-ACPC-containing oligomers 1–4, which are fully 12-helical, it is possible that both the 12- and 16-helical conformations are populated in solution. Previous 2D NMR analysis 1:1 α/β-peptides led us to conclude that the analogous pair of helical conformations (designated the 11- and 14/15-helices, respectively) is populated in solution for examples containing < 10 residues,15 and subsequent crystallographic studies have verified the occurrence of distinct helical conformations of 1:1 α/βpeptides that contain either i, i+3 C=O…H-N or i, i+4 C=O…H-N hydrogen bonds.12b,c Comparable behavior is well-known among α-peptides, involving the 310-helix (i, i+3 C=O…H-N hydrogen bonds) and the α-helix (i, i+4 C=O…H-N hydrogen bonds).16 Among α- and α/β-peptides, the available data suggest that increasing the number of amino acid residues causes a preference for i, i+4 C=O…H-N hydrogen bonded helices relative to i, i+3 C=O…H-N hydrogen bonded helices. If this trend holds for β-peptides that are rich in residues with a five-membered ring constraint, then it is possible that the 16-helical conformation will become dominant when the length of an ACPC-rich β-peptide is > 10 residues.

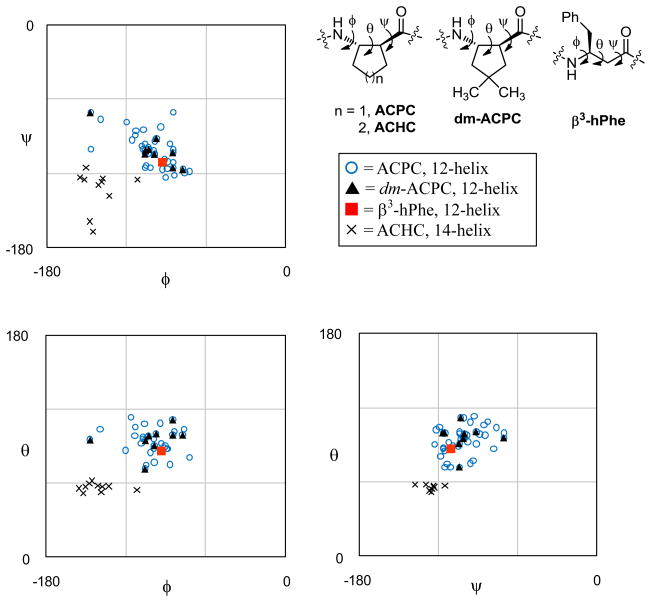

Backbone torsion angle analysis

The set of available crystal structures (five from this study and two from reference 5c) enables the identification of characteristic backbone torsion angle averages for the β-peptide 12-helix (Table 2). Figure 5 presents the crystallographically determined torsion angles for 12-helical β-peptides in Ramachandran-type plots.17 For comparison, these plots contain also backbone torsion angles derived from the two 14-helical crystal structures of hoomooligomers of 2-aminoacyclohexanecarboxylic acid (ACHC).18 Torsion angles for left-handed helical structures (pentamer 3, the two ACPC homooligomers5c and one of the 14-helical structures18) were inverted for this comparison. For heptamer 5 and the two 14-helical ACHC homooligomers, torsion angles of only one independent molecule in the crystal are included. In all three Ramachandran-type plots, the ACPC and dm-ACPC residues fall in the same region, which is distinct from the region that is characteristic of the 14-helix. The β3-hPhe residue in the structure of 5 falls into the region for the 12-helix instead of the region for the 14-helix, even though acyclic β3-amino acid residues are generally understood to prefer 14-helical secondary structure relative to 12-helical secondary structure.2 Table 2 shows that the local conformation of β3-hPhe in 5 is adjusted to the 12-helical environment; for example, the θ angle is 87°, which is substantially larger than θ angles common for β3-amino acid residues in a 14-helical environment (~ 60°)2a and close to the average θ observed for residues with a five-membered ring constraint in a 12-helical environment (94°). The ability of the lone β3-hPhe in 5 to conform to the 12-helical environment is consistent with the view that this type of β-amino acid residue is intrinsically flexible and can adapt to a variety of conformational contexts.

Table 2.

Average β-residue torsion angles (deg) for the 12- and the 14-helices

| 12-helixa,e |

14-helixa,e |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACPC | dm-ACPC | β3-hPheb | overallc | ACHCd | |

| φ | −100(15) [25] | −101(20) [9] | −93 | −100(16) [35] | −141(13) [10] |

| ψ | −102(14) [25] | −101(14) [9] | −111 | −102(14) [35] | −126(6) [9] |

| θ | 94(11) [25] | 96(11) [9] | 87 | 94(10) [35] | 57(3) [10] |

The number in brackets indicates number of measured and averaged distances.

Only one set of torsion angles was used.

Torsion angle averages identified from ACPC, dm-ACPC and β3-hPhe residues.

Reference 18; ACHC = (1S,2S)-2-aminocyclohexanecarboxylic acid.

For heptamer 5 and the two ACHC homooligomers, only one independent molecule was used.

Figure 5.

Ramachandran-type plots for right-handed helical β-peptides. Torsion angles for the 14-helix were measured from the crystal structures in reference 18. Torsion angles for left-handed helical structures have been inverted. For heptamer 5 and the two 14-helical ACHC homooligomers, torsion angles of only one independent molecule in the crystal are shown. ACHC = (1S,2S)-2-aminocyclohexanecarboxylic acid.

Helical parameter analysis

Average structural parameters for the β-peptide 12-helix were derived from five of the available crystal structures (oligomers containing five or more β-residues). Each helical parameter was calculated from sets of four consecutive α-carbons by reported methods.19 Non-helical residues at C-termini were excluded from these calculations. This approach prevented the use of structures for tetramers 1 and 2 in the analysis. For heptamer 5, only one independent conformation was used because all four independent conformations of 5 in the two crystal structures are quite similar.

The calculated parameters reveal the characteristic features of the β-peptide 12-helix. The rise-per-turn of the β-peptide 12-helix is 5.4 Å, which is same as the pitch of the α-helix and a bit smaller than that of the 310-helix (5.8 Å). The radius of β-peptide 12-helix is 2.1 Å, which is slightly smaller than that of the α-helix (2.3 Å) and comparable to that of the 310-helix (2.0 Å).20 Table 3 lists the parameters for five i, i+3 C=O—H-N hydrogen-bonded helices adopted by β-peptides (the 12-helix), α-peptides (the 310-helix)20 or α/β-peptides.12c,d The radii and the rise-per-residue values for these five helices are quite similar to one another. The rise-per-turn (p) becomes slightly smaller as the proportion of β-residues increases, suggesting that fine-tuning of the helical pitch can be achieved by changing the proportion of β-residues. This correlation should be useful in design efforts that require specific arrangements of side chain groups along the helical surface.

Table 3.

Average parameters for i, i+3 C=O—H-N hydrogen-bonded helices for α-, β-, and α/β-peptides.

| peptide backbone (helix type) | res/turn n | rise/turn p (Å) | rise/res d (Å) | radius r (Å) | β-residue % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-peptide (12-helix) | 2.7(1) | 5.4(1) | 2.0(1) | 2.1(1) | 100 % |

| 1:2 α/β-peptidea | 2.9 | 5.5 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 67 % |

| 1:1 α/β-peptide (11-helix)b | 2.8 | 5.6 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 50 % |

| 2:1 α/β-peptidea | 2.9 | 5.8 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 33 % |

| α-peptide (310-helix)c | 3.2 | 5.8 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 0 % |

Conclusions

The five crystal structures disclosed here, along with two previously reported structures of ACPC homooligomers, have allowed us to identify canonical structural characteristics of the β-peptide 12-helix. The conformational behavior of dm-ACPC is seen to be very similar to that of ACPC, implying that functional groups could be placed at C4 of the five-membered ring without interferring with 12-helical propensity. Analysis of torsion angles and helical parameters suggests that the β-peptide 12-helix is comparable to the i, i+3 C=O—H-N hydrogen-bonded helices formed by αpeptides and by 1:1, 1:2 and 2:1 α/β-peptides. The structural insight that emerges from this study should facilitate the design of 12-helical β-peptides intended to perform specific functions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. T. Peelen for providing synthetic materials. This work was supported in part by NSF grant CHE-0848847 and NIH grant GM-56414. S.H.C. was supported in part by a fellowship from the Samsung Scholarship Foundation. X-ray equipment purchase was supported in part by grants from the NSF.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental details, characterization data, crystallographic information, full table of helical parameters and alternative crystal structure of heptamer 5. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Gellman SH. Acc Chem Res. 1998;31:173. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Cheng RP, Gellman SH, DeGrado WF. Chem Rev. 2001;101:3219. doi: 10.1021/cr000045i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Seebach D, Hook DF, Glattli A. Biopolymers. 2006;84:23. doi: 10.1002/bip.20391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crisma M, Formaggio F, Moretto A, Toniolo C. Biopolymers. 2006;84:3. doi: 10.1002/bip.20357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Wu YD, Wang DP. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:9352. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gunther R, Hofmann HJ, Kuczera K. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:5559. [Google Scholar]; (c) Beke T, Somlai C, Perczel A. J Comput Chem. 2006;27:20. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Appella DH, Christianson LA, Klein DA, Powell DR, Huang XL, Barchi JJ, Gellman SH. Nature. 1997;387:381. doi: 10.1038/387381a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Applequist J, Bode KA, Appella DH, Christianson LA, Gellman SH. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:4891. [Google Scholar]; (c) Appella DH, Christianson LA, Klein DA, Richards MR, Powell DR, Gellman SH. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:7574. [Google Scholar]; (d) Barchi JJ, Huang XL, Appella DH, Christianson LA, Durell SR, Gellman SH. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:2711. [Google Scholar]; (e) Wang XF, Espinosa JF, Gellman SH. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:4821. [Google Scholar]; (f) Lee HS, Syud FA, Wang XF, Gellman SH. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:7721. doi: 10.1021/ja010734r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) LePlae PR, Fisk JD, Porter EA, Weisblum B, Gellman SH. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:6820. doi: 10.1021/ja017869h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Woll MG, Fisk JD, LePlae PR, Gellman SH. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:12447. doi: 10.1021/ja0258778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Park JS, Lee HS, Lai JR, Kim BM, Gellman SH. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:8539. doi: 10.1021/ja034180z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Peelen TJ, Chi YG, English EP, Gellman SH. Org Lett. 2004;6:4411. doi: 10.1021/ol0483293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hetényi A, Tóth GK, Somlai C, Vass E, Martinek TA, Fülöp F. Chem Eur J. 2009;15:10736. doi: 10.1002/chem.200900724.Hetényi A, Szakonyi Z, Mándity IM, Szolnoki É, Tóth GK, Martinek TA, Fülöp F. Chem Commun. 2009:177. doi: 10.1039/b812114a.While this paper was under review, a very thorough characterization of 12-helix formation by oligomers of trans-2-aminocyclobutanecarboxylic acid appeared: Fernandes C, Faure SPereira E, Théry V, Declerck V, Guillot R, Aitken DJ. Org Lett Articles ASAP. doi: 10.1021/ol101267u.The crystal structure reported by Aitken et al. is not included in our structural analysis.

- 7.(a) Porter EA, Wang XF, Lee HS, Weisblum B, Gellman SH. Nature. 2000;404:565. doi: 10.1038/35007145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Porter EA, Weisblum B, Gellman SH. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:7324. doi: 10.1021/ja0260871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) English EP, Chumanov RS, Gellman SH, Compton T. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508485200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Imamura Y, Watanabe N, Umezawa N, Iwatsubo T, Kato N, Tomita T, Higuchi T. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:7353. doi: 10.1021/ja9001458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simpson GL, Gordon AH, Lindsay DM, Promsawan N, Crump MP, Mulholland K, Hayter BR, Gallagher T. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:10638. doi: 10.1021/ja0614565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Kiss L, Kazi B, Forró E, Fülöp F. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:339. [Google Scholar]; (b) Menegazzo I, Fries A, Mammi S, Galeazzi R, Martelli G, Orena M, Rinaldi S. Chem Commun. 2006:4915. doi: 10.1039/b612071g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Chandrasekhar S, Reddy GPK, Kiran MU, Nagesh C, Jagadeesh B. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:2969. [Google Scholar]

- 11.An alternative secondary structure has been observed for an AZT-derived subunits in a different solvent: Threlfall R, Davies A, Howarth NM, Fisher J, Cosstick R. Chem Commun. 2008:585. doi: 10.1039/b714350h.

- 12.(a) Moretto V, Crisma M, Bonora GM, Toniolo C, Balaram H, Balaram P. Macromolecules. 1989;22:2939. [Google Scholar]; (b) Choi SH, Guzei IA, Gellman SH. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:13780. doi: 10.1021/ja0753344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Choi SH, Guzei IA, Spencer LC, Gellman SH. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6544. doi: 10.1021/ja800355p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Choi SH, Guzei IA, Spencer LC, Gellman SH. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:2917. doi: 10.1021/ja808168y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Lee HS, LePlae PR, Porter EA, Gellman SH. J Org Chem. 2001;66:3597. doi: 10.1021/jo001534l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) LePlae PR, Umezawa N, Lee HS, Gellman SH. J Org Chem. 2001;66:5629. doi: 10.1021/jo010279h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horne WS, Price JL, Gellman SH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801135105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayen A, Schmitt MA, Ngassa FN, Thomasson KA, Gellman SH. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;43:505. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Karle IL, Balaram P. Biochemistry. 1990;29:6747. doi: 10.1021/bi00481a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Toniolo C, Benedetti E. Trends Biochem Sci. 1991;16:350. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90142-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramachandran GN, Sasisekharan V. Adv Protein Chem. 1968;23:283. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60402-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Appella DH, Christianson LA, Karle IL, Powell DR, Gellman SH. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:6206. [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Sugeta H, Miyazawa T. Biopolymers. 1967;5:673. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kahn PC. Comput Chem. 1989;13:185. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barlow DJ, Thornton JM. J Mol Biol. 1988;201:601. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90641-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.