Abstract

Despite high rates of grandmother involvement with young grandchildren, very little research has examined the associations between non-residential grandmother involvement and grandchild social adjustment. The present study draws 127 families enrolled in the Family Transitions Project to consider the degree to which mother-reported maternal grandmother involvement buffers 3- and 4-year old grandchildren from economic, parenting, and child temperamental risks for reduced social competence and elevated externalizing behaviors. Findings indicate that higher levels of mother-reported grandmother involvement reduced the negative association between observed grandchild negative emotional reactivity and social competence. Further, high levels of mother-reported grandmother involvement protected grandchildren from the positive association between observed harsh mother parenting and grandchild externalizing behaviors. These findings underscore the relevance of moving beyond the nuclear family to understand factors linked to social adjustment during early childhood.

Keywords: grandparents, intergenerational relationships, early childhood, social competence, externalizing behaviors

Early childhood social adjustment is marked by the emergence of patterns of social competence and externalizing behaviors that remain relatively stable across childhood (e.g., Angold & Egger, 2007; Shaw et al., 2003). Research has consistently outlined economic, parenting and child temperamental risks for the development of low-levels of social competence and elevated levels of externalizing behaviors. Identifying factors that protect young children’s social adjustment in the presence of these risks is a priority for researchers and practitioners. Grandmother involvement may be protective for some grandchildren. Although many grandmothers are involved in the lives of their grandchildren, we know little about how this involvement impacts the social adjustment of grandchildren. The effects of grandmother involvement likely vary according to particular family, parent and child characteristics. The present study examines whether grandmother involvement protects grandchildren from three specific risks associated with low social competence and elevated externalizing behaviors.

Risks associated with maladaptive early childhood adjustment

Early childhood is noted for increases in social competence (e.g., Hay, Payne & Chadwick, 2004) and elevated levels of externalizing behaviors (e.g., Campbell et al., 2000). During early childhood, children develop the capacity to regulate negative emotions in the face of frustration and to comply with parental requests (e.g., Kochanska, 1997). At the same time, early childhood is a period of increased bouts of unregulated negative affect and willful defiance (e.g., Campbell et al., 2000). These behaviors, typically categorized as externalizing behaviors, are normative and limited to early childhood. However, they become indicators of maladjustment when they persist, increase or intensify (e.g., Campbell et al., 2000).

The present study considers three risk factors associated with low social competence and increased externalizing behaviors. First, family economic disadvantage is consistently linked to poor child social competence and elevated externalizing behaviors (e.g., Conger & Donellan, 2007; Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). Second, exposure to high levels of harsh parenting increases children’s risk for poor adjustment during early childhood (e.g., Campbell et al., 2000; Shaw et al., 2003). Finally, children’s own temperamental characteristics, especially high levels of negative emotional reactivity, can increase risks for poor adjustment as these behaviors impede the development of self-regulation and reduce opportunities for prosocial interactions (e.g., Guerin, et al., 1997; Lemery et al., 2002). Greater grandmother involvement may protect children from those risk factors, thereby decreasing risks for maladjustment.

Grandmother involvement and grandchild early childhood adjustment

Grandparents, particularly grandmothers, often play important roles in the lives of their grandchildren, especially during early childhood. For example, nearly 9% of all grandparents with grandchildren under age 5 reported providing extensive childcare, defined as at least 30 hours a week, or at least 90 nights per year (Fuller-Thomson & Minkler, 2001). Grandmothers also often provide considerable emotional, financial, and informational support to parents and grandchildren (e.g., Smith & Drew, 2002). Maternal grandmothers in particular are highly involved with young grandchildren (e.g., Barnett et al., 2010; Chan & Elder, 2000), and thus they may influence grandchildren’s adjustment. The effects of grandmother involvement on grandchild adjustment may be direct, through interactions with grandchildren, or indirect, through relationships with mothers. Theoretically, under normative or low-risk conditions grandmother involvement may not affect grandchildren’s adjustment because under these optimal childrearing conditions, grandmothers’ involvement may provide a nice addition to family life, but their roles are redundant to parental roles (Lavers & Sonuga-Burke, 1997). However, under high-risk conditions (e.g., economic disadvantage or challenging child characteristics) grandmothers may provide safety nets, such that greater grandmother involvement has a positive effect on grandchildren’s adjustment (Smith & Drew, 2002; Silverstein & Ruiz, 2006). Little empirical research exists on the relationship between varying risks and grandmother effects.

Most research examining grandmother influences on grandchildren focuses on high-risk, multigenerational adolescent-mother and maternal grandmother families (e.g., Chase-Lansdale et al., 1994). This work rarely considers direct associations between grandmother involvement and child development, and grandmother involvement is often defined as co-residence (Pittman & Boswell, 2007; Dunifon & Kowaleski-Jones, 2007). When grandmother involvement and co-residence are examined separately, only involvement is linked to positive mother parenting and grandchild adjustment (e.g., Chase-Lansdale et al., 1994; East & Felice, 1996). Therefore, one goal of the present study is to explore maternal grandmother involvement in less risky, non-residential contexts.

When considering the impact of grandmother provision of childcare on early childhood adjustment, results are mixed. Higher levels of grandmother involvement have been associated with greater risks to grandchildren’s social-emotional development (Connell et al., 2009; Fergusson et al., 2007). For example, Fergusson and colleagues (2007) reported that grandmother childcare during infancy and toddlerhood was positively associated with more behavior problems among 4 year-olds; however, this association was substantially reduced when maternal characteristics, including income and education were considered. In contrast, among low-income families, Pittman and Boswell (2007) found no association between mother-reported grandmother caregiving and levels of 2 to 4 year old children’s internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. Quite possibly, factors that affect parents’ decisions to rely on grandmothers for childcare in the first place (e.g., daycare costs, child expulsions from daycare) may place children at risk for less optimal adjustment independent of grandmother involvement. That is, parents’ economic disadvantage, their parenting behaviors, and children’s temperamental characteristics may directly influence children’s social adjustment and parents’ decisions to solicit grandmother involvement. Thus, the magnitude of the effect of grandmother involvement on children’s adjustment may be tied to family risks. Research on grandmother involvement in families with lower risk is needed to determine the extent to which grandmother involvement can buffer grandchildren form specific threats to social adjustment.

Grandmother involvement as a buffer for maladaptive early childhood adjustment

High levels of grandmother involvement may attenuate the impact of economic, parenting, and child temperamental risk on grandchildren’s social adjustment. Turning first to economic risks, grandmothers may provide financial assistance to families by contributing to housing costs so that families can reside in better quality neighborhoods, by purchasing other resources for grandchildren, and by reducing parents’ need to pay for daycare by providing childcare assistance. In addition, grandmother financial assistance may reduce mothers’ felt financial strain, thus indirectly influencing children’s social adjustment.

Grandmother involvement may also reduce the negative impact of harsh parenting on children’s social adjustment. Quite possibly, children’s interactions with grandmothers who are sensitive and responsive may counteract the effects of interactions with mothers who are harsh and intrusive. Although harsh parenting in one generation is likely to demonstrate continuity in the next generation (e.g., Scaramella & Conger, 2003), grandparents may demonstrate discontinuities in parenting in that grandparents’ interactions with their grandchildren may be qualitatively different from their interactions with their own children. For example, some grandmothers may adopt a spoiling or indulgent attitude towards their grandchildren (Cherlin & Furstenberg, 1986). Although very little research has compared concurrently assessed mother and grandmother parenting, Barnett and The Family Life Project Key Investigators (2008) found that among low-income mothers and grandmothers jointly raising an infant, grandmothers had higher mean levels of observed sensitive parenting during a dyadic interaction with the infant than mothers. Perhaps grandmothers are generally less harsh during interactions with grandchildren than mothers are, or grandmothers who perceive their daughters as harsh actively attempt to minimize the impact of such parenting by increasing their levels of sensitivity during interactions with their grandchildren. Regardless of the reason, sensitive and responsive relationships with grandmothers may enhance children’s social adjustment, particularly for those children who regularly experience harsh parenting.

Finally, grandmother involvement may reduce the association between grandchildren’s temperamental reactivity and social competence and externalizing behaviors. Children with a propensity to react to frustrating situations with negative emotion are often difficult for parents to manage (e.g., Campbell et al., 2000; van Aken et al., 2007). Because grandmothers have experience raising children, they may provide critical emotional and practical support for parents. Alternatively, non-residential grandmothers may not find children’s propensity to negative emotional reactivity as challenging because they have time away from grandchildren; thus, grandmothers are less likely, as compared to mothers, to react to negative emotional reactivity with harsh parenting. In turn, participation in sensitive, non-hostile interactions may particularly benefit children with high levels of negative emotional reactivity (e.g., Belsky et al., 2007). In sum, grandmother involvement may buffer the negative influences of economic risk, harsh parenting, and children’s temperamental reactivity.

The Present Study

The present study examined the extent to which mother-reported maternal grandmother involvement protects young grandchildren from the negative impact of specific family, parenting, and temperamental risks to grandchildren’s social competence and externalizing behaviors. Three moderation hypotheses were evaluated. Specifically, greater maternal grandmother involvement was expected to attenuate the associations of: 1) low household income, 2) high levels of observed mother harsh parenting, and 3) high levels of observed grandchild negative emotional reactivity during a frustrating situation with lower levels of social competence and elevated levels of externalizing behaviors.

Method

Participants

Participants were drawn from the Family Transitions Project (FTP), an ongoing intergenerational study of 558 families. Interviews were first conducted with adolescents (G2) and their parents (G1) as part of the Iowa Youth and Families Project (IYFP) as early as 1989, when the target youth were in 7th grade (see Conger and Conger 2002). Data were collected annually thereafter with an average retention rate of 92% through 2007. Biological children of the G2 participants who were at least 18-months old and their other parent were recruited into the study beginning in 1997 (see Conger, Neppl, Kim, and Scaramella, 2003). Beginning in 1999, comprehensive assessments of all parent participants occurred on a biennial schedule. Questions about grandparent involvement in the lives of their grandchildren were added to the full parent assessment in 2001. Consequently, only families with data collected during 2001, 2003, and 2005, and when the grandchildren were 3 or 4 years-old are included in the present study. However, parent-reported social competence and externalizing behaviors at age 2 are used to statistically control for previous levels when predicting age 3 or 4 levels of adjustment.

The present analyses include 127 families who had assessments when children were 2 years of age and 3 or 4-years of age. The research questions focus on maternal grandmother involvement, thus the grandchild’s mother reported on the involvement of her own mother. As a result, the mothers in the present study represent a combination of G2 females who were original participants in the IYFP study and the partners of original G2 male participants. Likewise, some of the grandmothers were IYFP G1 participants, while other grandmothers never participated in the study themselves. Therefore, we are unable to report grandmother characteristics beyond mother-reported grandmother involvement with grandchildren. At the preschool assessment (age 3–4), children averaged 42.03 months of age (SD = 5.64 months). Mother age ranged from 22 to 29 years, with a mean of 25.86 (SD = 2.39). Nearly 52% (n = 66) of the grandchildren were female. Approximately 88% of the grandchildren resided in two-parent homes. Parents identified approximately 97% of parents and grandchildren as White, and the other 3% as non-white (i.e., African-American, Native American, Hawaiian, or other). The average income-to-needs ratio was 3.56 (SD = 2.73), indicating that although most families were not experiencing economic hardship, there was considerable variability across participants.

Procedures

From 1997 onward, parent participants with an eligible biological child completed an in-home visit. These visits occurred annually when children were between the ages of 18 months and 7 years of age. Only data from children ages 3 and 4 are used in the present study. The same protocol was used for the 3- and 4-year old assessments. Prior to the in-home visit, mothers and fathers completed questionnaires including questions about their demographic characteristics and their children’s adjustment. During the in-home assessment, parents and children participated in a variety of structured tasks. The present study includes behavioral observations from a 5-minute mother-child puzzle task during which children were presented with a puzzle that was too hard to complete alone. Mothers were instructed to offer any help necessary, but to let children complete the puzzle alone. The present study also includes behavioral observations of a 3.5 minute frustration task for G3 children designed to elicit negative emotion.

Measures

Maternal grandmother involvement

Mothers completed three items regarding the involvement of their own mothers with their children. First, mothers rated how involved their own mothers were in raising their child on a 3-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all involved) to 3 (very involved). On average, mothers’ reported that their own mothers were involved in the lives of their children (mean = 2.39; SD = .61). Second, mothers reported how often their own mothers saw their children on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (every day). On average, mothers reported maternal grandmothers had contact with their children at least once a week (mean = 4.65; SD = .96). Finally, mothers reported how much help their own mothers provided in raising their children on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (none at all) to 4 (a lot). In general, mothers reported that their own mothers provided some childrearing help (mean = 2.83; SD = .61). A grandmother involvement score was calculated as the mean of the standardized mean of each item (alpha = .72). Higher scores indicate higher levels of grandmother involvement (mean = .07; SD = .82).

Grandchild social competence

Mothers and fathers completed the social competence scale of the short form of the Social Competence and Behavior Evaluation scale (SCBE; LaFreniere & Dumas, 1996) regarding the child’s behavior during the past two months when children were 2 and 3–4 years-old. Ten items were rated on a 3-point scale ranging from 1 (not true) to 3 (very true or often true). Sample items include: “cooperates with others,” and accepts compromise.” Means of the ten items were computed separately for mothers and fathers. Both mothers’ and fathers’ responses were internally consistent (alpha: mothers =.72; fathers = .70) and significantly correlated (r = .36; p < .05). A social competence score was computed by averaging mothers’ and fathers’ ratings. Higher scores indicate higher levels of social competence (mean = 2.60, SD = 1.54).

Grandchild externalizing behaviors

Mothers and fathers completed the Child Behavior Checklist for ages 1 ½ – 5 years (Achenbach, 1994) when children were 2 and 3–4 years-old. Parents’ rated children’s behavior during the past two months on a 3-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all true) to 2 (always or often true). The 25 externalizing items were summed to create an externalizing behaviors scale. Mothers’ and fathers’ ratings were internally consistent (alpha: mothers = .86; fathers =.84) and correlated (r =.47, p < .05). The mean of mothers’ and fathers’ scores was used (mean = 10.46, SD = 5.22).

Parent economic disadvantage

Parents reported on their annual household income and family size. Income-to-needs ratios were calculated by dividing the total household income by the federal poverty threshold for the size of the household for the year of data collection. Values of one indicate that a family is just able to make ends meet.

Mothers’ harsh parenting

Trained observers rated videotapes of mothers’ harsh behaviors towards their children during the 5-minute puzzle task. Observers rated six parenting behaviors: hostility (i.e., harsh, angry, and rejecting behaviors), escalate hostile (i.e., parents’ intensification of their own hostile behavior towards the child), reciprocate hostile (i.e., parents’ hostile responses to child’s anger), angry-coercion (i.e., attempts to control child’s behavior in an angry or threatening manner), antisocial (i.e., disruptive, age-inappropriate behavior), and physical attack (i.e., hitting, pushing, slapping) (Melby & Conger, 2001). Codes were rated on a 9-point scale ranging from no evidence of the behavior (1), to the behavior is highly characteristic of the parent (9). Harsh parenting (alpha = .83) scores represent the mean of the six scales. Higher scores indicate higher levels of harsh, intrusive and hostile parenting. Mean mother harsh parenting was 2.40 (SD = 1.25). Inter-rater reliability estimates for the observations of mother harsh parenting were computed using intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) procedures for the 25% of the interaction tasks that were coded by two independent observers. The ICC estimates for the six scales comprising the harsh parenting score ranged from .72 to .86, for a mean ICC of .81.

Grandchildren’s negative emotional reactivity to frustration

Trained coders rated children’s temperamental reactivity during a 3.5 minute structured frustration task, the impossibly perfect circles task derived from the Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery for preschoolers (Goldsmith et al., 1999). Children were instructed to draw “the perfect green circle” at three one-minute intervals. Interviewers critiqued each circle in a neutral voice by making comments such as, “That one is too pointy, try again,” “That one is too small, try again,” or “The lines don’t meet, try again.” After the final one minute interval, interviewers critiqued children’s circles for 30 more seconds and then brought children back to a neutral state by identifying the perfect green circle. The 3.5 minute episode was divided into 21 ten-second epochs. In each epoch coders rated five child behaviors. Three of the behaviors measured children’s negative emotional reactivity and were used in the present analyses: bodily anger, intensity of protest, and intensity of opposition. Bodily anger was rated as either present (1) or absent (0) in each epoch. The two intensity scales were rated on a 3-point scale reflecting the degree to which there was no protest or opposition (0), only physical or verbal protest or opposition (1), or physical and verbal protest or opposition (2). A frustration reactivity score was created by summing the ratings of bodily anger, protest, and opposition for each epoch such that higher scores indicated greater frustration. The peak negative emotional reactivity score was used for the present analyses. The peak negative emotional reactivity score from the epoch during which the child was rated as the most frustrated was used as a predictor of social adjustment. Peak reactivity scores ranged from 0–4 with a mean of 2.10 (SD = .89), indicating that most children displayed moderate frustration reactivity and there was variability in reactivity scores. In order to measure inter-rater reliability, the ICC was calculated for the 25% of all frustration tasks coded by two independent raters (Cicchetti, 1994). The ICC estimates for the three scales used in the present analyses ranged from .78 to .96, for a mean ICC of .87.

Analytical Procedures

Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) hierarchical regression analyses were computed to test all study hypotheses with separate models estimating social competence and externalizing behaviors. In the first step of each regression equation, grandchild adjustment (social competence or externalizing behaviors) at age 2 was included to control for past behavior. This first step also included grandchild sex and age and the three risk indicators: economic disadvantage, mothers’ harsh parenting, and grandchild negative emotional reactivity. Grandmother involvement was added in the second step to estimate the unique influence of grandmother involvement. Finally, the interactions between grandmother involvement and each source of risk (i.e., income-to-needs ratio, mother harsh parenting, and negative emotional reactivity to frustration) were entered in the third step. Statistically significant interaction terms were calculated from centered variables and interpreted following standard procedures (i.e., Aiken & West, 1991; Preacher et al., 2006).

Results

The next section first describes results of the correlational analyses, and then discusses results of the regression models predicting social competence and externalizing behaviors.

Correlational Analyses

Table 1 summarizes the results of the correlational analyses. The three risk factors, income-to-needs ratio, mothers’ harsh parenting, and negative emotional reactivity to frustration, were correlated as expected with social competence and externalizing behaviors. Parents who reported higher income-to-needs ratios also reported greater age 3–4 social competence. Conversely, higher levels of observed mother harsh parenting and negative emotional reactivity to frustration were associated with lower social competence. Age 3–4 externalizing behaviors were negatively associated with income-to-needs-ratios and positively associated with harsh parenting and negative emotional reactivity to frustration. Social competence and externalizing behaviors demonstrated modest stability from age 2 to age 3–4. Grandmother involvement was not significantly correlated with other variables.

Table 1.

Bivariate Correlations and Means of Independent and Dependent Variables (N = 127).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Grandchild age 3–4 Social Competence | __ | |||||||||

| 2. Grandchild age 3–4 Externalizing | −.32*** | __ | ||||||||

| 3 Grandchild age 2 Social Competence | .57*** | −.13 | __ | |||||||

| 4. Grandchild age 2 Externalizing | −.25** | .56*** | −.22** | __ | ||||||

| 5. Grandchild sexa | .17* | −.17* | .18* | −.12 | __ | |||||

| 6. Grandchild age (months) | .03 | .07 | .05 | .04 | −.10 | __ | ||||

| 7. Income-to-Needs | .18* | −.21** | .09 | −.21* | .06 | −.17* | __ | |||

| 8. Mother harsh parenting | −.16* | .24** | −.03 | .01 | .01 | −.02 | −.13 | __ | ||

| 9. Grandchild negative reactivity (frustration) | −.16* | .16* | −.15 | .15 | −.01 | −.28** | .11 | .06 | __ | |

| 10. Grandmother Involvement | .11 | .05 | .17 | −.02 | −.09 | .06 | −.15 | −.01 | −.01 | __ |

| Mean | 1.25 | .42 | 1.08 | .49 | .49 | 40.93 | 3.56 | 2.40 | 2.10 | .07 |

| SD | .29 | .21 | .26 | .19 | .50 | 5.95 | 2.74 | 1.25 | .89 | .82 |

Note:

p < .05;

p < .01,

p < .001.

0 = male, 1= female.

Regression models predicting social competence

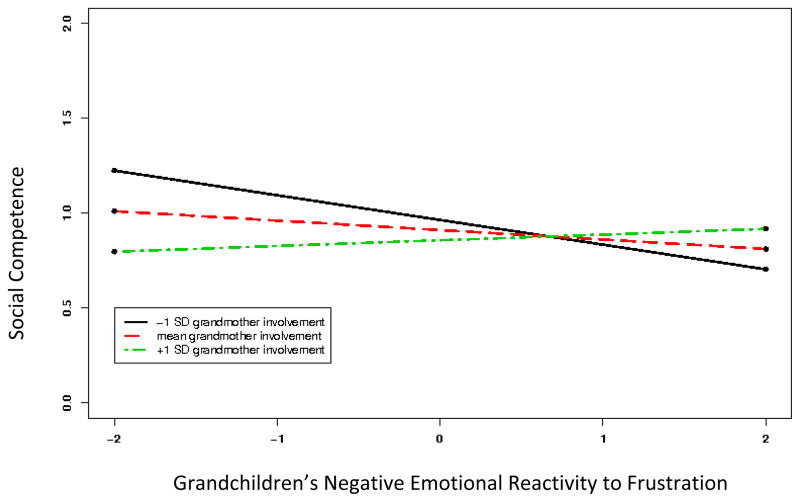

Table 2 summarizes the results of the regression analysis evaluating the main and interactive effects of grandmother involvement and risk on grandchildren’s social competence. The first model, which estimated the effects of the control variables (i.e., grandchild age, grandchild sex, and age 2 social competence) and the main effects of the hypothesized risks on social competence (i.e., income-needs-ratios, observed mother harsh parenting, and grandchild negative emotional reactivity to frustration) accounted for a statistically significant portion of the observed variance in grandmother involvement, F (6,121) = 11.38, p < .001, adjusted R2 = .34. Age 2 social competence was positively associated with age 3–4 social competence. Higher levels of observed grandchild negative emotional reactivity to frustration were associated with lower levels of social competence, while higher income-to-needs ratios predicted higher levels of social competence. Model 2 added the main effects of mother-reported grandmother involvement with grandchildren. The addition of grandmother involvement failed to explain additional variance associated with social competence, and did not change the pattern of associations between the independent variables and social competence. Model 3 tested the hypotheses regarding the buffering effects of grandmother involvement by including interaction terms between income-to-needs ratio, mother harsh parenting, and grandchild negative emotional reactivity and grandmother involvement. The addition of the interaction effects explained marginally significant portions of the variance associated with social competence (ΔR2 = 0.03, p < .10) and the beta associated with the grandchild negative emotional reactivity to frustration X grandmother involvement interaction term was statistically significant. The interaction was interpreted by plotting the simple slopes of the lines defining the relationship between social competence and negative emotional reactivity at three levels of grandmother involvement, 1 SD above the mean, at the mean, and 1 SD below the mean. As shown in Figure 1, negative emotional reactivity to frustration was negatively associated with social competence for grandchildren with low levels (b = −.13, p < .05) of grandmother involvement.

Table 2.

Hierarchical Regression Models Predicting Grandchild Social Competence

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β | |

| Grandchild sex | .01 | .05 | .02 | .01 | .04 | .04 | .02 | .05 | .04 |

| Grandchild age | −.01 | .00 | −.08 | −.01 | .00 | −.08 | −.01 | −.00 | −.11 |

| Age 2 social competence | .62 | .09 | .54*** | .63 | .09 | .55*** | .61 | .09 | .53*** |

| Income-to-needs ratio | .03 | .02 | .15* | .03 | .02 | .14† | .03 | .02 | .14† |

| Mother harsh parenting | −.04 | .04 | −.10 | −.05 | .04 | −.10 | −.06 | .03 | −.15* |

| Grandchild negative reactivity | −.06 | .03 | −.17* | −.06 | .03 | −.17* | −.05 | .03 | −.15† |

| Grandmother involvement | −.01 | .03 | −.04 | −.06 | .04 | −.19 | |||

| Income-to-needs ratio X | .01 | .02 | .07 | ||||||

| grandmother involvement | |||||||||

| Mother harsh parenting X | .04 | .03 | .18 | ||||||

| grandmother involvement | |||||||||

| Grandchild negative reactivity | .09 | .04 | .18* | ||||||

| X grandmother involvement | |||||||||

| Adjusted R2 | .34 | .34 | .37 | ||||||

| F for change in R2 | 11.38*** | .30 | 2.58† | ||||||

Note:

p < .10,

p < .05;

p < .01,

p < .001.

0 = male, 1= female.

Figure 1.

Grandmother involvement moderates the relationship between grandchildren’s negative emotional reactivity to frustration and social competence

Regression models predicting externalizing behaviors

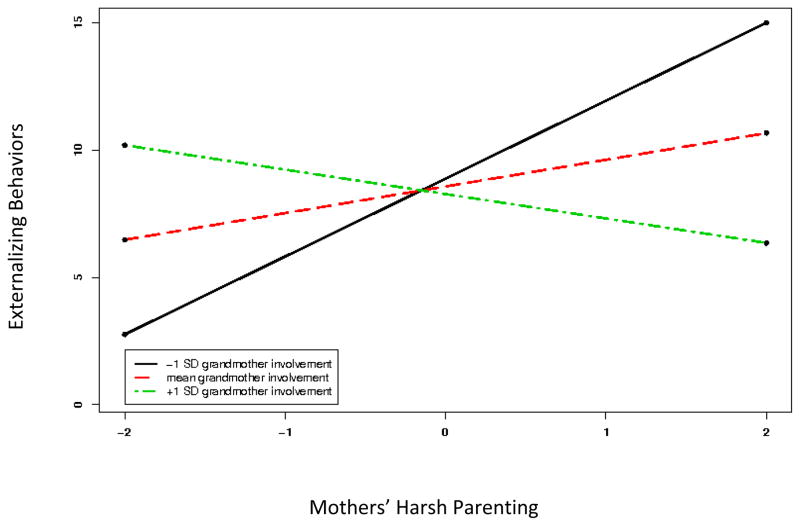

Table 3 summarizes the results from hierarchical regression models predicting externalizing behaviors. Model 1 accounted for a statistically significant portion of the observed variance in parent-reported grandchild externalizing behaviors, F (6,121) = 9.03, p < .001, adjusted R2 = .29. Age 2 ratings of externalizing behaviors positively predicted age 3–4 externalizing behaviors. Higher income-to-needs ratios and observed mother harsh parenting were associated with lower levels of externalizing behaviors. In Model 2, the main effect of grandmother involvement on externalizing behaviors was estimated. Similar to the findings for social competence, this model failed to account for additional variance in externalizing behaviors. In Model 3, the terms representing the interaction between the three hypothesized sources of risk and grandmother involvement were added. The beta coefficient associated with mother harsh parenting X grandmother involvement was statistically significant. This interaction term was interpreted by plotting the simple slopes of the lines defining the relationship between mother harsh parenting and child externalizing behaviors when grandmother involvement was 1 SD below the mean, at the mean and 1 SD above the mean. As shown in Figure 2, mother harsh parenting was positively associated with externalizing behaviors only among grandchildren with mean (b = 1.97, p < .05) or lower (b = 4.17, p < .01) mother-reported grandmother involvement.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Regression Models Predicting Grandchild Externalizing Behaviors

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β | |

| Grandchild sex | −.29 | .96 | −.03 | −.32 | .97 | −.03 | −.23 | .98 | −.02 |

| Grandchild age | −.02 | .08 | −.02 | −.02 | .08 | −.02 | −.01 | .08 | −.01 |

| Age 2 externalizing behaviors | 14.01 | 2.25 | .49*** | 14.02 | 2.26 | .49*** | 13.50 | 2.25 | .48*** |

| Income-to-needs ratio | −.61 | .32 | −.15* | −.63 | .33 | −.16* | −.57 | .33 | −.14† |

| Mother harsh parenting | 1.91 | .73 | .21** | 1.90 | .73 | .21* | 1.97 | .72 | .21** |

| Grandchild negative reactivity | −.16 | .57 | −.02 | −.16 | .57 | −.02 | .03 | .58 | .01 |

| Grandmother involvement | −.27 | .58 | −.04 | −.39 | .57 | −.05 | |||

| Income-to-needs-ratio X | .25 | .34 | .06 | ||||||

| Grandmother involvement | |||||||||

| Mother harsh parenting X | −2.47 | 1.08 | −.18* | ||||||

| grandmother involvement | |||||||||

| Grandchild negative reactivity | −.45 | .88 | −.04 | ||||||

| X grandmother involvement | |||||||||

| Adjusted R2 | .29 | .29 | .31 | ||||||

| F for change in R2 | 9.03*** | .23 | 2.31† | ||||||

Note:

p < .10,

p < .05;

p < .01,

p < .001.

= male, 1= female.

Figure 2.

Grandmother involvement moderates the relationship between mothers’ harsh parenting and grandchildren’s externalizing behaviors

Discussion

The goal of this study was to examine the degree to which maternal grandmother involvement protected grandchildren from risks associated with maladjustment during the preschool years. In general, more grandmother involvement was expected to buffer grandchildren from the negative impact of low household income, high mother harsh parenting, and high levels of negative emotional reactivity to frustration. Limited support emerged for the study hypotheses, as the findings underscore the need for future research in this area.

Maternal Grandmother Involvement and Grandchild Social Competence

Consistent with expectations, grandmother involvement offered some protection for grandchildren with high levels of observed negative emotional reactivity to frustration. Specifically, when grandmother involvement was average or above average, negative emotional reactivity to frustration was no longer a risk for low social competence. Thus, grandmother involvement buffered a child-level risk associated with poor social competence. Grandchildren with high levels of negative emotional reactivity to frustration can be especially difficult to parent (e.g., van Aken et al., 2007). Grandmothers may provide support to the mothers of these children, and thus indirectly influence grandchildren’s social competence. That is, grandmothers may be more skilled in raising young children, especially those who are highly reactive, and may be more patient when children display high levels of negative emotional reactivity. Alternatively, grandmother-grandchild interactions may be qualitatively different from parent-child interactions given different expectations shaping grandmother and mother roles (Cherlin & Furstenberg, 1986). Interactions with grandmothers may provide grandchildren opportunities to engage in positive social interactions, thus promoting social competence. Further, children who display high levels of reactivity may be more sensitive to childrearing contexts (e.g., Belsky et al., 2007), and thus they may benefit the most from grandmother involvement.

Maternal Grandmother Involvement and Externalizing Behaviors

In support of the hypothesis regarding mothers' parenting behaviors, high levels of grandmother involvement were protective for grandchildren exposed to mothers’ harsh parenting. Specifically, when mothers reported high levels of maternal grandmother involvement, their observed harsh, intrusive parenting behavior during a puzzle task was not related to their children’s externalizing behaviors. This finding is particularly striking given the robust relationship across studies between harsh parenting and externalizing behaviors (e.g., Campbell et al., 2000; Shaw et al., 2003). The association between concurrent measures of mother-reported grandmother involvement, harsh parenting and externalizing behaviors emerged net the effect of previous levels of externalizing behaviors. One explanation could be that parent-child relationships marked by high levels of harsh parenting and children’s negative behaviors, including externalizing behaviors, are likely to grow increasingly negative overtime because these parent and child behaviors are mutually reinforcing (Scaramella & Leve, 2004). Perhaps grandmother involvement weakens this cycle because more supportive interactions with grandmothers model positive behaviors and discourage negative behaviors. Longitudinal research is needed to disentangle the direction of effects and long-term implications of grandmother involvement, harsh parenting, and child behavior problems.

In addition, role expectations for grandmothers, especially for those who do not have considerable childcare responsibilities, may include spoiling and coddling grandchildren (Cherlin & Furstenberg, 1986; Smith & Drew, 2002). However, no empirical work has linked grandparent role expectations to behaviors or to child development among non-custodial grandmothers (Smith & Drew, 2002). Interactions with a grandmother who is responsive or indulgent may buffer grandchildren from the impact of harsh, intrusive interactions with the mother. The grandmother’s behavior may be a conscious compensation for grandchildren’s experiences with the mother, or it may be an actualization of grandparent role expectations. Future research should consider the qualitative components of grandmother involvement, including the motivations for and nature of the grandmother-grandchild relationship.

Taken together, these findings suggest that different mechanisms may underlie the links between grandmother involvement and social competence and externalizing behaviors. Maternal grandmother involvement may offer a respite from harsh parenting, thus reducing the association between observed mothers’ harsh parenting and grandchild externalizing behaviors. On the other hand, grandmothers may provide advice to facilitate mothers’ positive engagement with highly reactive children that in turn fosters the development of social competence. The present study cannot identify if the positive influence of grandmother involvement on grandchildren’s social competence for grandchildren with high levels of negative emotional reactivity to frustration is direct through interactions with those grandchildren, or indirect through the facilitation of more positive or supportive parenting (distinct from harsh parenting) that encourages development of social competence. Above all, these findings underscore the need for future research that includes comprehensive measurement of grandmother-grandchild relationships and parenting in order to identify the specific pathways linking grandmother involvement to various indices of grandchild social adjustment.

Grandmother Involvement Does Not Buffer Economic Risks to Social Adjustment

Contrary to expectations, grandmother involvement did not protect children from the impact of low household income on social adjustment. There are possible explanations for the lack of findings. First, given intergenerational transmission of economic disadvantage, grandmothers may have had few financial resources to spare for their daughters’ families. Second, although this was not a highly disadvantaged sample, it may be unrealistic for grandmother involvement to protect children from the multiple risks stemming from economic disadvantage (e.g., Conger & Donellan, 2007). Future research that considers multiple dimensions of economic disadvantage is necessary.

Study Strengths and Limitations

The present study has a number of strengths. First, this is one of a handful of studies to consider the effects of non-residential grandmother involvement on grandchild adjustment. Investigations of grandmother involvement in samples in which socioeconomic risk and grandmother involvement are not confounded are especially rare. Second, consistent with research on parenting and children’s adjustment (e.g., Belsky et al., 2007), our findings indicate that the children’s own temperamental characteristics interact with the caregiving environment. Importantly, grandmother involvement may benefit grandchildren often considered more temperamentally difficult or challenging to raise (e.g., van Aken et al., 2007). Third, our findings show that grandmother involvement can disrupt the relationship between mothers’ harsh parenting and preschool children’s externalizing behaviors (e.g., Shaw et al., 2003). Children’s negative emotional reactivity to frustration and mother harsh parenting were measured using observational ratings. In fact, another strength of this study is the use of multiple reporters, including mothers and fathers and observational measures of parenting and child reactivity.

Despite these strengths, the study is not without limitations. First, although all models include prior levels of children’s adjustment, measures of grandmother involvement and risks to development are concurrent, and thus the direction of effects is unclear. Second, the results may not generalize to more disadvantaged and ethnically diverse samples. Third, the measure of grandmother involvement consists of mothers’ reports on three items. Therefore, mother perceptions of grandmother involvement may not reflect the quality of grandmother-grandchild interactions. Importantly, grandmother involvement was not correlated with any study variables, and thus this measure may be tapping a distinct construct related to grandmother involvement, not more general family or maternal functioning. Future studies should use comprehensive measures of grandmother involvement, including grandmother reports and observations of grandmother-grandchild interactions. Fourth, future investigations could include grandmother characteristics. Finally, although maternal grandmothers are typically the most involved with young grandchildren (e.g., Chan & Elder, 2000), future research should include grandfathers and paternal grandparents. Moreover, this study focused on maternal parenting in part, because examination of correlations between mothers’ and fathers’ parenting and children’s social competence and externalizing behaviors in the present sample suggested that mothers’ parenting only was correlated with children’s adjustment. Therefore, examining the extent to which grandmother involvement moderates the association between mother parenting and children’s social adjustment is a stronger test for the role of grandmother involvement. However, multigenerational research including fathers’ parenting is warranted.

Implications for Research and Practice

The present study includes several implications for research and practice. The findings highlight the need for further investigation of associations between grandmother involvement and grandchild social adjustment. The detection of moderated rather than main effects of grandmother involvement may in part explain the inconsistent findings regarding main effects of grandmother involvement on grandchildren (e.g., Fergusson et al, 2007; Pittman & Boswell, 2007). That is, within this non-economically disadvantaged and non-adolescent mother sample, non-residential grandmother involvement was related to social competence and externalizing behaviors for grandchildren experiencing specific risks. Understanding when grandmother involvement benefits grandchildren provides key information for development of family support programs and interventions. For example, programs that identify high levels of negative emotional reactivity to frustration or harsh maternal parenting as risk factors may improve child adjustment by including grandmothers, or encouraging grandmother involvement. Further, this study adds to research linking grandparent involvement to grandparent well-being (e.g., Reitzes & Mutran, 2004) by suggesting that grandmother involvement may also improve the social adjustment of some grandchildren. Thus, grandparent involvement may carry benefits for at least two generations. Broadly, the results underscore the need to move beyond the nuclear family to consider how other adults, including grandmothers, influence child development.

Acknowledgments

This research is currently supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute of Mental Health (HD047573, HD051746, and MH051361). Support for earlier years of the study also came from multiple sources, including the National Institute of Mental Health (MH00567, MH19734, MH43270, MH59355, MH62989, and MH48165), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA05347), the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD027724), the Bureau of Maternal and Child Health (MCJ-109572), and the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Adolescent Development Among Youth in High-Risk Settings.

Footnotes

This article is based in part on a presentation made at the Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development in April 2009 in Denver, CO.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/fam

Contributor Information

Melissa A. Barnett, University of Arizona

Laura V. Scaramella, University of New Orleans

Tricia K. Neppl, Iowa State University

Lenna L. Ontai, University of California - Davis

Rand D. Conger, University of California - Davis

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach T. Child Behavior Checklist. VT: University of Vermont; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Egger HL. Preschool psychopathology: Lessons for the lifespan. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48:961–966. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett MA, Scaramella LV, Neppl TK, Ontai L, Conger R. Intergenerational relationships, gender, and grandparent involvement. Family Relations. 2010;59:28–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2009.00584.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett & The Family Life Project Key Investigators. Mother and grandmother parenting in low-income three-generation rural households. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70:1241–1257. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00563.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van Ijzendoorn MH. For better and for worse: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;16(6):300–304. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Shaw DS, Gilliom M. Early externalizing behavior problems: Toddlers and preschoolers at risk for later maladjustment. Developmental Psychopathology. 2000;12(3):467–488. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CG, Elder GH. Matrilineal advantage in grandchild–grandparent relations. Gerontologist. 2000;40:179–190. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase-Lansdale PL, Brooks-Gunn J, Zamsky ES. Young African-American multigenerational families in poverty: Quality of mothering and grandmothering. Child Development. 1994;65:373–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ, Furstenberg FF. The new American grandparent: A place in the family, a life apart. New York: Basic Books; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger K. Resilience in midwestern families: Selected findings from the first decade of a prospective, longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:361–373. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Donellan MB. An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:175–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Neppl K, Kim KJ, Scaramella L. Angry and aggressive behavior across three generations: A prospective, longitudinal study of parents and children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:143–160. doi: 10.1023/a:1022570107457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell A, Mitchell C, Dishion T, Shaw D, Wilson M, Gardner F. Patterns of grandparental caregiving and relations with youth functioning in a low-income sample. Paper presented at the Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; Denver. April 2009.2009. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J. Economic deprivation and early childhood development. Child Development. 2000;65(2):296–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunifon RE, Kowaleski-Jones L. The influence of grandparents in single-mother families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007:465–481. [Google Scholar]

- East PL, Felice ME. Adolescent pregnancy and parenting: Findings from a racially diverse sample. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson E, Maghan B, Golding J. Which children receive grandparental care and what effect does it have? The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;49:161–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Thomson E, Minkler M. American grandparents providing extensive child care to their grandchildren: Prevalence and profile. The Gerontologist. 2001;41:201–209. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH, Reilly J, Lemery KS, Longley S, Prescott A. The laboratory temperament assessment battery: Preschool version. Unpublished manuscript 1999 [Google Scholar]

- Guerin DW, Gottfried AW, Thomas CW. Difficult temperament and behaviour problems: A longitudinal study from 1.5 to 12 years. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1997;21:71–90. [Google Scholar]

- Hay DF, Payne A, Chadwick A. Peer relations in childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:84–108. doi: 10.1046/j.0021-9630.2003.00308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G. Multiple pathways to conscience for children with different temperaments: From toddlerhood to age 5. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:228–240. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.2.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFreniere PJ, Dumas JE. Social competence and behavior evaluation in children ages 3 to 6 years: The short form (SCBE-30) Psychological Assessment. 1996;8(4):369–377. [Google Scholar]

- Lavers CA, Sonuga-Burke EJ. Annotation: On the grandmothers’ role in the adjustment and maladjustment of grandchildren. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38(7):757–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemery KS, Essex MJ, Smider NA. Revealing the relation between temperament and behavior problem symptoms by eliminating measurement confounding: Expert ratings and factor analyses. Child Development. 2002;73(3):867–882. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, Conger RD. The Iowa family interaction rating scales: Instrument summary. In: Kerig PK, Lindahl KM, editors. Family observational coding systems: Resources for systematic research. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2001. pp. 33–57. [Google Scholar]

- Pittman LD, Boswell MK. The role of grandmothers in the lives of preschoolers growing up in urban poverty. Applied Developmental Science. 2007;11(1):20–42. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Reitzes D, Mutran EJ. Grandparenthood: Factors influencing frequency of grandparent–grandchildren contact and grandparent role satisfaction. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2004;59:S9–S16. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.1.s9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella LV, Conger RD. Intergenerational continuity of hostile parenting and its consequences: The moderating influence of children's negative emotional reactivity. Social Development. 2003;12:420–439. [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella LV, Leve LD. Clarifying parent-child reciprocities during early childhood: The early childhood coercion model. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2004;7:89–107. doi: 10.1023/b:ccfp.0000030287.13160.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Gilliom M, Ingoldsby EM, Nagin DS. Trajectories leading to school-age conduct problems. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39(2):189–200. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PK, Drew LM. Grandparenthood. In: Borenstein MH, editor. Handbook of Parenting. Vol. 3. Mahwah, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 141–169. [Google Scholar]

- van Aken C, Junger M, Verhoeven M, van Aken MAG, Deković M. The interactive effects of temperament and maternal parenting on toddlers' externalizing behaviours. Infant and Child Development. 2007;16:553–572. [Google Scholar]